In almost all countries with available data, the majority of upper secondary graduates from general programmes are women. Men dominate graduation from vocational programmes in almost three-quarters of the countries.

While the average age of first-time graduates from general upper secondary education does not differ much across countries, the difference widens in vocational education, ranging from 16 to 34 years.

76% of upper secondary vocational graduates across OECD countries completed a programme that allows direct access to tertiary education.

Education at a Glance 2022

Indicator B3. Who is expected to graduate from upper secondary education?

Highlights

1. Average age is based on all graduates instead of first-time graduates.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the average age of first-time upper secondary graduates in general programmes.

Source: OECD//Eurostat/UIS (2022), Tables B3.1 and B3.2. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-B.pdf).

Context

Upper secondary education, which in many countries includes separate general and vocational pathways, aims to prepare students to enter further levels of education or the labour market. In many countries, this level of education is not compulsory and programmes typically take two to five years to complete.

Post-secondary non-tertiary education can prepare students for entry into the labour market or, less commonly, for tertiary education. The knowledge, skills and competencies offered tend to be less complex than is characteristic of tertiary education, and not significantly more complex than upper secondary programmes. These programmes have a full-time equivalent duration of between six months and two years.

In most OECD countries, almost all lower secondary students go on to enrol in upper secondary education. In general, demand for upper secondary education is increasing worldwide, with the development of a variety of educational pathways. In fact, graduating from upper secondary education has become increasingly important in all countries, as the skills needed in the labour market are becoming more knowledge-based, and workers are increasingly required to adapt to the uncertainties of a rapidly changing global economy.

COVID-19 led to critical disruptions to education across OECD and partner countries. In particular, education systems have had to significantly redesign graduation criteria and examinations to adjust to the unprecedented situation. At the upper secondary level, where examinations are the most common means for certifying that students have met the requirements for completing the level, some flexibility in assessments has been necessary. Some countries have used only school marks as the graduation criteria, some have postponed or rescheduled examinations, and others have awarded students automatic validation of their studies for the academic year (OECD, 2021[1]).

Other findings

On average across the OECD, one-third of upper secondary vocational students graduated from engineering, manufacturing and construction programmes in 2020.

Post-secondary non-tertiary programmes are less prominent in the educational landscape than other levels of education. On average across OECD countries, almost one-quarter of graduates in vocational programmes at this level specialised in health and welfare in 2020.

On average, students who started with a general upper secondary qualification have a higher completion rate at bachelor’s level than those who started with a vocational upper secondary qualification.

Analysis

Profile of upper secondary graduates

An upper secondary qualification (ISCED level 3) is often considered to be the minimum credential for successful entry into the labour market and necessary for continuing to higher levels of education. Young people who leave school before completing upper secondary education tend to have worse employment prospects (see Indicators A3 and A4). For many young people, the transition from lower to upper secondary education involves deciding whether to enrol in general education or pursue vocational education and training (VET). The selection process and the factors influencing which programme orientation students enter (e.g. test results, records of academic performance or teacher advice) also vary between countries (OECD, 2016[2]). How much choice young people have in practice therefore differs across countries. An important challenge is to ensure that the decision to pursue a general or a vocational programme is driven by students’ interests and abilities, not their personal circumstances, which they cannot influence.

Upper secondary systems in OECD countries take a variety of approaches to occupational preparation. Many countries in Europe, Latin America and South-East Asia have a distinct vocational track or even a multi-track system. The latter often distinguishes between vocational programmes oriented towards traditional occupations (e.g. plumber, hairdresser) and those focused on technical and technological areas (e.g. IT technician, media designer), often designed to prepare for tertiary studies in that area. For example, in addition to general education, Belgium and Slovenia have a vocational and a technical track, while France offers a technological baccalauréat. In other countries, occupational preparation at upper secondary level does not take place in a separate vocational track at all. In Canada, upper secondary education remains predominantly general, but students may choose modules offering technical and occupational training. In the United States, students can undertake vocational coursework, but this does not result in a specialised diploma. In other countries where initial upper secondary education includes no or limited vocational content, those who graduate with an upper secondary vocational qualification tend to be adults (OECD, 2022[3]).

In 2020, on average across OECD countries, 37% of those graduating from upper secondary education for the first-time obtained a vocational qualification, ranging from 5% in Canada to 74% in Austria, rising to 44% on average among European countries. Seven other OECD and partner countries besides Canada have 20% or less of their upper secondary graduates obtaining a vocational qualification: Brazil (8%), Costa Rica (20%), Hungary (19%), Iceland (19%), Korea (17%), Lithuania (15%) and New Zealand (14%) (Table B3.2). It is not always the case that vocational tracks are viewed as less attractive options in countries with lower levels of participation (CEDEFOP, 2014[4]). However, in Hungary and Lithuania, evidence suggests that vocational programmes are viewed less positively within society, and are less likely to be considered as providing high-quality learning, than in other European countries (OECD, 2017[5]).

By gender

Effective upper secondary education systems need to offer high-quality learning options to both men and women. Gender imbalances in general or vocational programmes, or in particular fields of study, can raise equity issues. For example, if vocational programmes serve mostly men, women who are less attracted to academic forms of learning might struggle to find a suitable option. Alternatively, if VET offers limited pathways for progression, it may then be more difficult for men to pursue higher levels of education. Indicators in this area are best interpreted together with information on labour-market outcomes from vocational programmes, the progression pathways into higher levels of education, and data on the take up of those pathways.

The gender balance in general and vocational programmes also varies considerably across countries. On average across OECD countries, women made up 55% of upper secondary graduates in general programmes in 2020, compared to 45% in vocational programmes (Figure B3.2). In almost all countries with available data, women make up at least half of upper secondary graduates from general programmes, ranging from 49% in Korea to more than 60% in Italy and Slovenia (Table B3.1). Men dominate graduation from vocational programmes in almost three-quarters of the countries. There is, however, much cross‑country variation: the share of women graduating from vocational programmes ranged from 34% or less in Estonia, Hungary, Iceland and Lithuania to more than 60% in Ireland in 2020 (Table B3.2). Ireland was one of just five OECD and partner countries where women made up a larger share of graduates in vocational programmes than in general programmes (13 percentage points). In the other four countries – Brazil, Colombia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom – the difference between the share of women in vocational and general programmes was less than 7 percentage points. In many cases, gender enrolment patterns in vocational programmes are related to the fields of study typically targeted by these programmes.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the share of women among upper secondary graduates in general programmes.

Source: OECD//Eurostat/UIS (2022), Tables B3.1 and B3.2. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-B.pdf).

By age

While the average ages of first-time graduates from upper secondary general education do not differ much across countries, the difference widens in vocational education. This reflects the fact that a general upper secondary qualification is typically the final stage of initial schooling. In contrast, a vocational upper secondary qualification may also provide a second-chance opportunity to those who left school without an upper secondary qualification, allowing them to obtain a qualification to improve their employment prospects.

Among OECD countries with available data, the average age for graduation from upper secondary general education is 19 years old, and ranges from 17 to 21 years. Apart from Costa Rica and Portugal, all OECD countries have an average upper secondary graduation age of 20 or younger (Table B3.1). For vocational upper secondary programmes, the average age of first-time graduates varies more widely, ranging from 16 (Colombia) to 34 years (Canada). In countries, where there is little to no vocational education and training in the initial upper secondary education system, upper secondary VET programmes are mostly directed at adults. Canada has the highest average age of first-time vocational upper secondary graduates, as its upper secondary vocational programmes serve adults. Similarly in New Zealand, where the average upper secondary graduation age is 32, programmes at this level include post-schooling study for adults and includes bridging type programmes, “second-chance” or life/employment skills, or basic pre-employment programmes (Table B3.2) (OECD/INES, 2022[6]).

By fields of study

Since vocational programmes are designed to help learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed for particular occupations and trades, the choice of field of study is crucial. Specialising in a particular field in vocational education shapes further learning opportunities and subsequent labour-market outcomes. On average across the OECD, the largest share (33%) of students in upper secondary vocational education graduated from programmes in engineering, manufacturing and construction in 2020. This was followed by business, administration and law (17%), services (17%) and health and welfare (12%). However, this pattern does not hold for every country. In Brazil, Costa Rica, Luxembourg and Switzerland, the most popular upper secondary vocational qualification, among these four fields, was in business, administration and law. In Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain and the United Kingdom, the most popular field was health and welfare, and in Portugal, it was services (Table B3.2).

As with higher levels of education, there are marked gender patterns in choices of fields of study. Women are far more likely than men to study subjects relating to business, administration and law, as well as health and welfare. Men are more likely to choose engineering, manufacturing and construction or information and communication technologies (ICT), which are in great demand in labour markets in OECD countries (Table B3.2) (OECD, 2020[7]). These differences can be attributed to traditional perceptions of gender roles and identities as well as the cultural values sometimes associated with particular fields of education. Some studies have found that these gender differences in the choice of field of study are mirrored in the career expectations of 15-year-olds: on average across OECD countries, only 14% of the girls who were top performers in science or mathematics reported that they expect to work in science or engineering, compared with 26% of the top-performing boys (OECD, 2018[8]).

Few women in upper secondary vocational education pursue programmes in engineering, manufacturing and construction: on average across OECD countries, only 15% of graduates in this field were women in 2020. Colombia was the only country where women represented more than 40% of graduates for the field. In contrast, across OECD countries, female graduates were over-represented in health and welfare (83%); business, administration and law (62%); and services (58%). In health and welfare, women represented 90% or more of graduates in France, Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania (Table B3.2).

By level of completion

Upper secondary vocational programmes can be classified into three different groups according to the level of completion possible: partial completion without direct access to tertiary education; level completion without direct access to tertiary education; and level completion with direct access to tertiary education. The first category, partial completion, includes programmes that are part of a sequence of programmes at ISCED level 3 but are not the final programmes at this level, and do not provide direct access to higher ISCED levels. Such programmes are uncommon in OECD countries, with graduates reported only in Lithuania, the Slovak Republic, Sweden and the United Kingdom (Figure B3.3). Examples include intermediate upper secondary programmes in the United Kingdom, where most graduates progress on to further programmes that do provide full completion of upper secondary education with direct access to tertiary education. Even students who do not progress to programmes offering full level completion can use their intermediate qualification as part of an application to higher education (UCAS, 2021[9]). Similarly, in Sweden this category includes introductory programmes in upper secondary schools, which serve as a bridge between lower secondary and upper secondary education.

Programmes in the second category, level completion without direct access to tertiary education, tend to have a strong focus on preparation for labour-market entry. This category includes programmes leading to a certificate d’aptitude professionnelle (CAP) or a brevet professionnel in France, Leaving Certificate Applied Programmes in Ireland or one-year National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA 1) qualifications in New Zealand. The lack of direct access to tertiary education does not make these programmes a dead end. Programmes within this category may provide direct access to post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED level 4). In addition, graduates often have other access routes to tertiary education. For example, in Sweden, 69% of upper secondary vocational graduates completed a programme without direct access to tertiary education. However, students have the option to take additional general subjects while pursuing their vocational programme, in order to gain eligibility for tertiary education. In New Zealand those who complete NCEA 1 programmes commonly progress to NCEA 2 or 3 qualifications, which in turn provide access to tertiary education. More broadly, in several OECD countries there are bridging programmes (at ISCED level 3 or 4) that allow vocational graduates to obtain a qualification that provides direct access to tertiary education.

1. Most of the students who complete intermediate upper secondary programmes that do not give direct access to tertiary education will move to programmes that provide full completion of upper secondary with direct access to tertiary education.

2. Vocational programmes with direct access to tertiary education at upper secondary level are included with the same type of programmes at post-secondary tertiary level.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the share of graduates of programmes with direct access to tertiary education.

Source: OECD/Eurostat/UIS (2022), Table B3.2. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-B.pdf).

Across OECD countries, 76% of vocational graduates across OECD countries completed a programme that allows direct access to tertiary education. In 11 countries, all vocational graduates completed such programmes, and in almost all remaining OECD countries the majority of upper secondary vocational graduates have direct access to tertiary education (Figure B3.3). However, this does not necessarily mean that VET graduates have the same options available to them as general upper secondary graduates. While in many countries the qualification required for tertiary education yields access to all types of education, in some countries, there is a more nuanced set of arrangements. For example, in Germany, graduates from vocational ISCED level 3 programmes have direct access to professional tertiary programmes after relevant professional experience but in order to access academic tertiary programmes, they need either technically compatible professional practices and the completion of an aptitude test or obtain a professional tertiary qualification first. In Denmark, upper secondary vocational graduates have direct access to business academy programmes (ISCED level 5) and some professional bachelor’s programmes. They do not have direct access to academic bachelor’s programmes, but professional programmes may serve as a bridge to master programmes (OECD, 2022[10]).

Profile of post-secondary non-tertiary graduates

Post-secondary non-tertiary programmes (ISCED level 4) are relatively less prominent in the educational landscape than other levels of education. Eight OECD countries do not have these programmes at all (Chile, Costa Rica, Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, Slovenia, the Republic of Türkiye and the United Kingdom) and three others (Colombia, Israel and Switzerland) do not offer vocational programmes at this level of education (Table B3.3). In the countries that do, various kinds of post-secondary non-tertiary programmes are available. These programmes straddle upper secondary and post-secondary education and may be considered either as upper secondary or as post‑secondary programmes, depending on the country. Although the content of these programmes may not be significantly more advanced than upper secondary programmes, they broaden the knowledge of individuals who have already attained an upper secondary qualification.

Post-secondary non-tertiary programmes may be designed to increase participants' labour-market options or to increase their eligibility for further studies at the tertiary level, or both. Examples of such programmes include technicians’ diplomas, primary professional education or préparation aux carrières administratives (OECD/Eurostat/UNESCO, 2015[11]).

By programme orientation and level of completion

On average across OECD countries, 88% of post-secondary non-tertiary first-time graduates attended vocational programmes (Table B3.3). This level of education is particularly vocationally focused, as most post-secondary non‑tertiary programmes are designed for direct entry into the labour market. There are some national initiatives to provide general programmes at post-secondary non-tertiary level aimed at students who have completed vocational upper secondary education and want to increase their chances of entering tertiary education. For instance, in Switzerland, a one-year general programme, the university aptitude test, prepares graduates from vocational upper secondary education (after successful completion of the federal vocational baccalaureate) to enter general programmes at the tertiary level (OECD/Eurostat/UNESCO, 2015[11]).

Although post-secondary non-tertiary vocational education is designed to prepare students for entry into the labour market, it should not lock participants out of further learning options. In half of the 25 OECD and partner countries with data on this level, all or most students graduated from post-secondary non-tertiary vocational programmes that yield direct access tertiary education (or they might already be eligible thanks to their upper secondary qualification). In eight other countries, a majority of students graduated from post-secondary non-tertiary programmes with a focus on occupational skills, which are designed for direct entry into the labour market. The remaining countries offer a more mixed profile of programmes, some of which are designed to lead to further study and some of which are not (Table B3.3).

By field of study

On average across OECD countries, 23% of post-secondary non-tertiary graduates in vocational programmes specialised in health and welfare; 21% in engineering, manufacturing and construction; 18% in business, administration and law; and 17% in services in 2020. However, there were considerable variations across countries. In Luxembourg, for instance, 67% of post‑secondary non-tertiary graduates obtained a qualification in engineering, manufacturing and construction whereas in Austria, France and Poland this field accounted for 1% of graduates or less (Table B3.3).

On average across OECD countries, women made up 53% of post-secondary non-tertiary vocational graduates in 2020, but there were significant variations across countries, ranging from 24% in Luxembourg to 75% in Poland. This contrasts with the under-representation of women in upper secondary vocational education. There are two main reasons for the difference in gender balance. First, women in upper secondary vocational education have a higher completion rate than men and are therefore more likely to continue their studies in post-secondary non-tertiary education. Second, women are over-represented in certain broad fields of study, such as health and welfare, and business, administration and law, which are among the fields more commonly studied by post-secondary non-tertiary graduates (Table B3.3).

The share of female graduates from post-secondary non-tertiary vocational programmes is the largest in the field of health and welfare (80% in 2020); followed by business, administration and law (65%); services (55%); and engineering, manufacturing and construction (18%). In the field of health and welfare, women make up at least 70% of graduates in all countries with available data. In services, the share of female graduates varies more widely compared to other fields, ranging from 12% in Denmark to 74% in Latvia and Spain. Even so, women make up more than half of post-secondary non-tertiary vocational graduates in all but six countries in the field of services (Table B3.3).

By age

The average age of first-time graduates from post-secondary non-tertiary education is quite high compared to upper secondary graduates. On average, students graduated from post-secondary non-tertiary programmes at the age of 31 years across the OECD, with the average age ranging from 22 years in Belgium to 42 years in Finland. The average age of graduation was over 30 in all but eight countries (Table B3.3).

The comparatively high age of graduation may be due to the particular programmes offered at post-secondary non-tertiary level. They may tend to attract older individuals with some years of experience in the labour market already, either because work experience is typical for entry to the profession or because these programmes can facilitate a career change into a specific profession. For instance, in Finland, post-secondary non-tertiary programmes with direct access to tertiary education are taken usually after several years of work experience. In Norway, post-secondary non-tertiary education is provided through 6-18-month programmes designed to meet a number of specialised vocational needs and for direct entry into the labour market, and the average age of graduates was 34 years in 2020. In Portugal, special accommodation is made for older adults with related professional experience in the certification of post-secondary non-tertiary education. Adults over the age of 25 who have worked for at least five years in relevant fields can request the assessment of their professional skills by training institutions in order to obtain a technological specialisation diploma (Eurydice, 2021[12]), which can partly explain why the average age of first-time graduates is 30 years old (Table B3.3).

Box B3.1. Bachelor’s completion rate by upper secondary programme orientation

Creating strong pathways from upper secondary into tertiary education requires building suitable access routes and ensuring that students are well prepared for further studies. While general upper secondary programmes, by definition, are designed to equip students with the skills needed for post-secondary and tertiary education, vocational programmes tend to vary in their emphasis on preparation for further studies. This means that some vocational graduates may be poorly prepared to complete their tertiary programme. On the other hand, VET graduates may have an advantage over their peers from general education: when pursuing studies within the same field as their vocational qualification and, in some cases, where they have relevant work experience, they might be particularly well prepared and motivated to succeed in their studies.

On average, 41% of bachelor’s students who started with a general upper secondary qualification graduate within the theoretical duration of the programme. For those with a vocational upper secondary qualification the figure is 36%. This five percentage-point gap increases to 14 percentage points when comparing completion rates after three additional years following the end of the programme’s theoretical duration (Figure B3.4).

The pattern of completion rates within the theoretical duration varies widely across countries: students from general programmes have a higher completion rate than those with a vocational background in half of the countries with available data. However, the pattern becomes clearer when looking at completion rates after three additional years. Within this longer timeframe, completion rates of students with general upper secondary qualifications are either higher or very similar to those of students with vocational qualifications in nearly all countries. In fact, only in two countries – Austria and Sweden – are bachelor’s students from vocational upper secondary programmes more likely to graduate than their peers who attended general programmes (Figure B3.4).

An important part of the context is the share of bachelor’s students who have a vocational background. For example, in Lithuania, 45% of students from vocational upper secondary programmes graduate within the theoretical duration of the programme in which they entered. However, these students represent only around 2% of entrants into bachelor’s programmes. A number of factors may explain the low share of VET graduates among bachelor’s students. In some countries, such as Norway, only general upper secondary programmes grant direct access to ISCED level 6 or equivalent, with few exceptions. Similarly, in Estonia some upper secondary vocational programmes do not grant access to bachelor’s programmes. The data also refer to full-time students, so do not fully capture participation patterns in countries where VET graduates commonly pursue ISCED 6 programmes part-time.

In Austria, in contrast, a large share of bachelor level students have a vocational background and their completion rates are higher than for those with general upper secondary education. This reflects Austria’s large upper secondary VET system, in which there is a strong progression pathway from upper secondary education (year 1-3 of Berufsbildende Höhere Schulen, BHS) into short-cycle tertiary programmes (year 4-5 of BHS) and universities of applied sciences, as well as to universities though to a lesser extent.

Note: The share of students who graduated from vocational upper secondary programmes are shown in parentheses next to each country name. The year of reference for the data (2020) corresponds to the graduation year three years after the theoretical duration of the programme (2017). The reference year for students’ entry may differ depending on the duration of programmes.

1. Data are provided for the theoretical duration of the programme plus one semester (not the theoretical duration) in Sweden.

2. Data refer only to the hautes écoles (HE) and the écoles des arts (ESA), representing about 60% of entrants to bachelor's or equivalent programmes.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the completion rate by the theoritical duration of students with general upper secondary education.

Source: OECD (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-B.pdf).

Definition

Typical age is the age at the beginning of the last school/academic year of the corresponding educational level and programme when the degree is obtained.

Methodology

The average age of students is calculated from 1 January for countries where the academic year starts in the second semester of the calendar year and 1 July for countries where the academic year starts in the first semester of the calendar year. As a consequence, the average age of new entrants may be overestimated by up to six months, while that of first-time graduates may be underestimated by the same.

For more information, please see the OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics (OECD, 2018[13]).

Source

Data refer to the academic year 2019/20 and are based on the OECD/UIS/Eurostat data collection on education statistics administered by the OECD in 2021 (for details, see Annex 3 at https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-B.pdf).

References

[4] CEDEFOP (2014), “Attractiveness of initial vocational education and training: Identifying what matters”, Research Paper, No. 39, European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, Luxembourg, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/5539_en.pdf.

[12] Eurydice (2021), Assessment in post-secondary non-tertiary education, Eurydice, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/assessment-post-secondary-non-tertiary-education-34_en.

[3] OECD (2022), Diagrams of education systems, Education GPS website, https://gpseducation.oecd.org/CountryProfile.

[10] OECD (2022), Pathways to Professions: Understanding Higher Vocational and Professional Tertiary Education Systems, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a81152f4-en.

[1] OECD (2021), The State of School Education: One Year into the COVID Pandemic, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/201dde84-en.

[7] OECD (2020), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris,, https://doi.org/10.1787/bb167041-en.

[13] OECD (2018), OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018: Concepts, Standards, Definitions and Classifications, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264304444-en.

[8] OECD (2018), PISA 2018 Results (Volume II): Where All Students Can Succeed, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b5fd1b8f-en.

[5] OECD (2017), Education in Lithuania, Reviews of National Policies for Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264281486-en.

[2] OECD (2016), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en.

[11] OECD/Eurostat/UNESCO (2015), “ISCED 2011 Level 4: Post-secondary non-tertiary education”, in ISCED 2011 Operational Manual: Guidelines for Classifying National Education Programmes and Related Qualifications, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264228368-8-en.

[6] OECD/INES (2022), Isced mapping questionnaires data collection.

[9] UCAS (2021), UCAS Tariff Tables: Tariff points for entry to higher education for the 2022-23 academic year, UCAS, https://www.ucas.com/file/446256/.

Indicator B3 tables

Tables Indicator B3. Who is expected to graduate from upper secondary education?

|

Table B3.1 |

Profile of upper secondary graduates from general programmes (2020) |

|

Table B3.2 |

Profile of upper secondary graduates from vocational programmes (2020) |

|

Table B3.3 |

Profile of post-secondary non-tertiary graduates from vocational programmes (2020) |

Cut-off date for the data: 17 June 2022. Any updates on data can be found on line at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-data-en. More breakdowns can also be found at http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

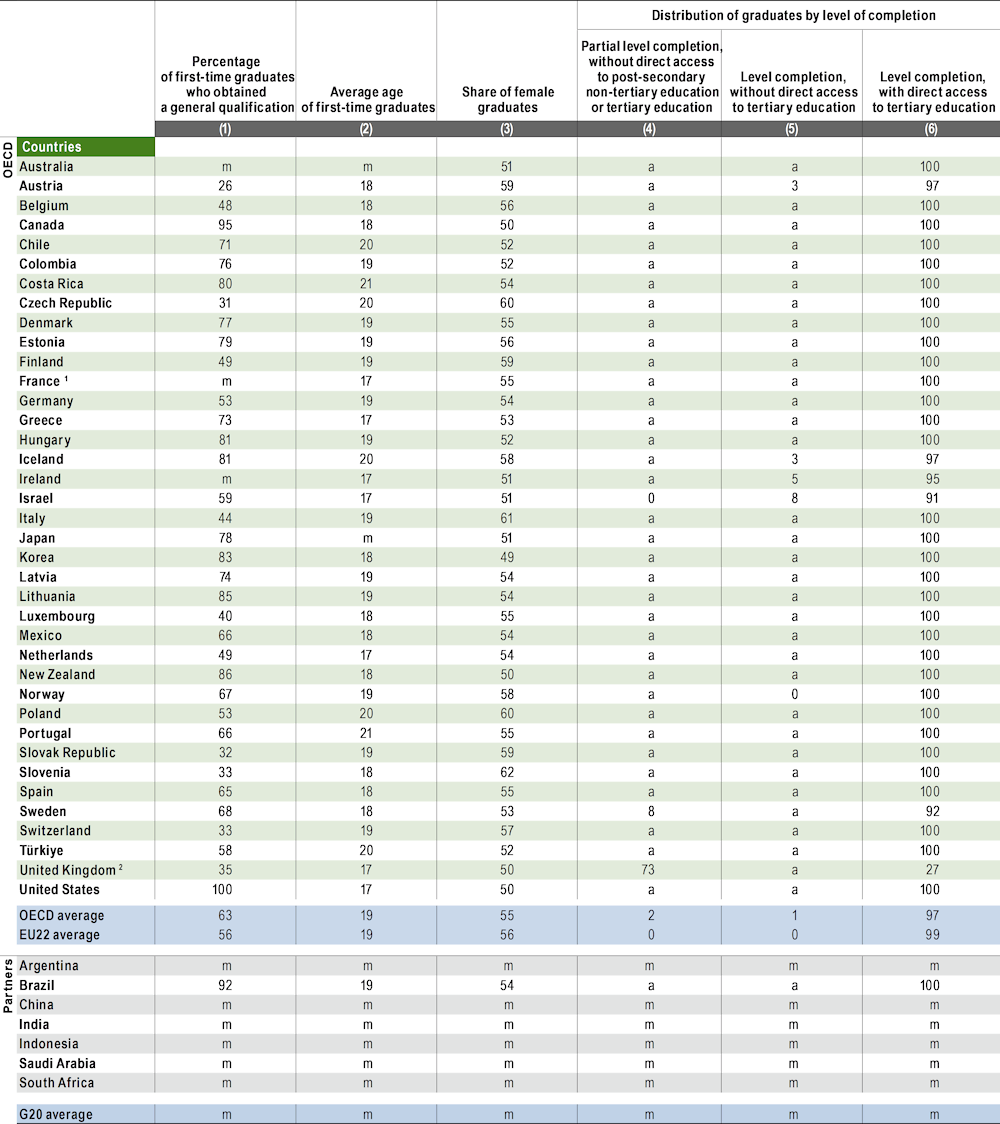

Table B3.1. Profile of upper secondary graduates from general programmes (2020)

Note: See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data and more breakdowns available at http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Average age is based on all graduates instead of first-time graduates.

2. Most of the students who complete intermediate upper secondary programmes that do not give direct access to tertiary education will move to programmes that provide full completion of upper secondary with direct access to tertiary education.

Source: OECD (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-B.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

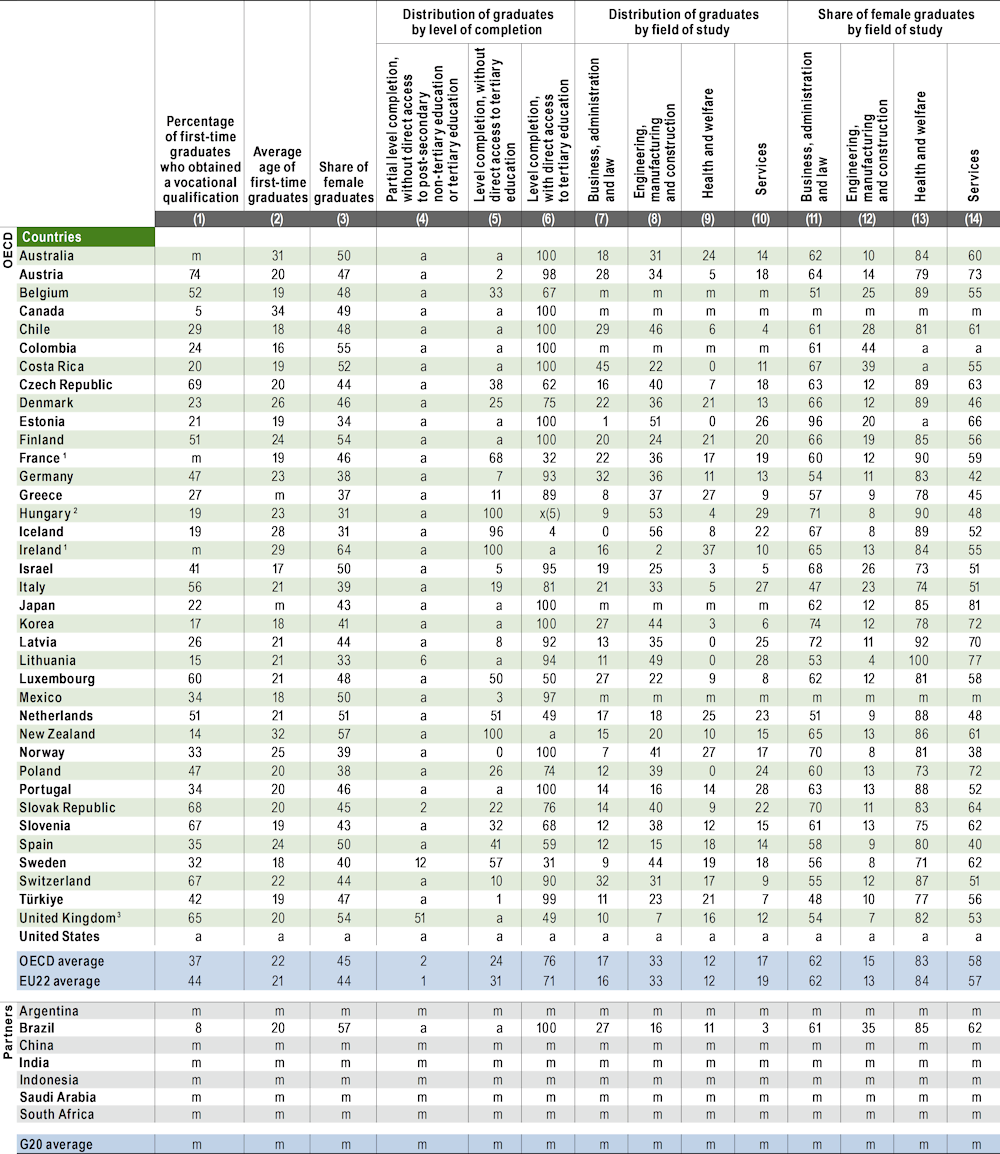

Table B3.2. Profile of upper secondary graduates from vocational programmes (2020)

Note: See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data and more breakdowns available at http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Average age is based on all graduates instead of first-time graduates.

2. Vocational programmes with direct access to tertiary education at upper secondary level are included with the same type of programmes at post-secondary tertiary level.

3. Most of the students who complete intermediate upper secondary programmes that do not give direct access to tertiary education will move to programmes that provide full completion of upper secondary with direct access to tertiary education.

Source: OECD (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-B.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

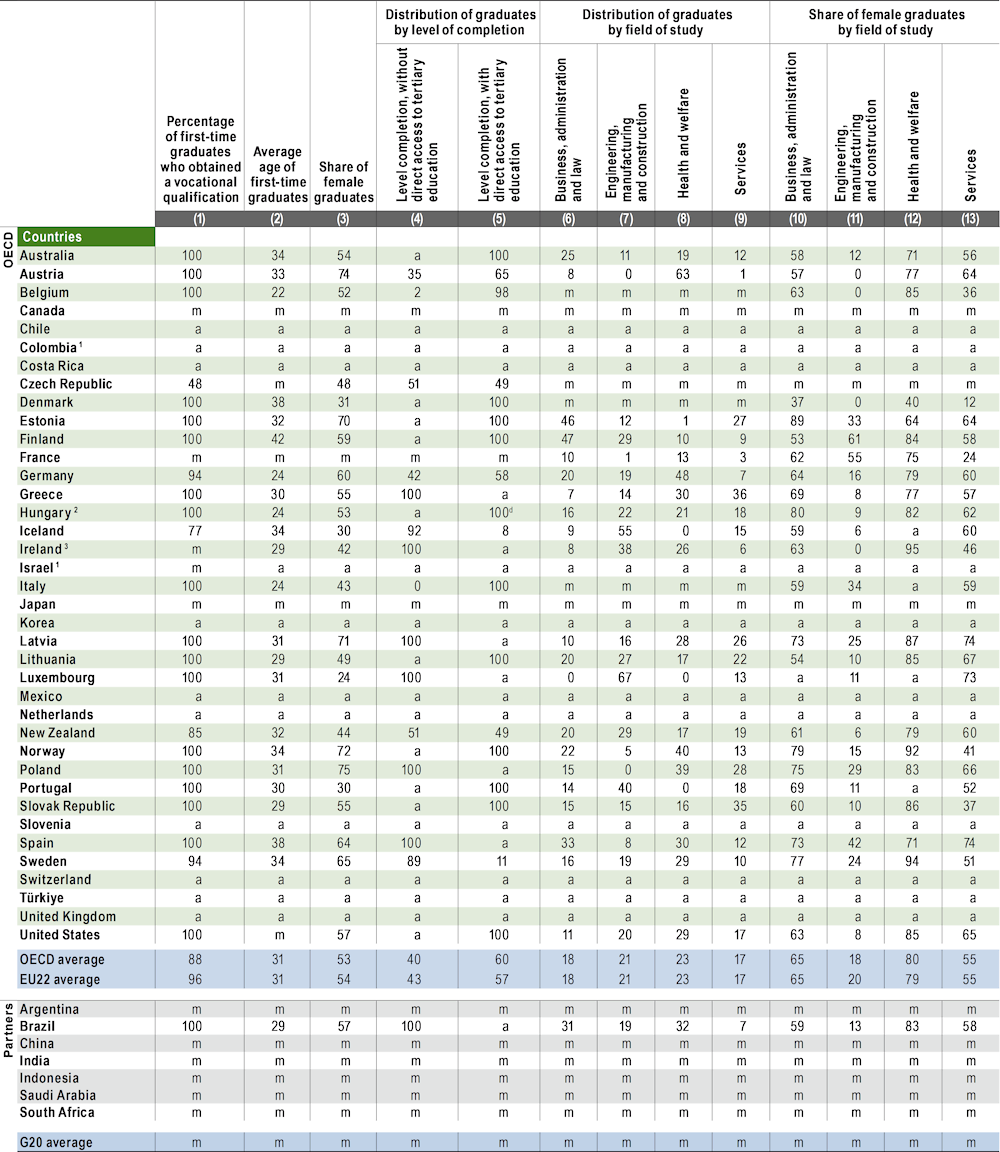

Table B3.3. Profile of post-secondary non-tertiary graduates from vocational programmes (2020)

Note: See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data and more breakdowns available at http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Programmes with direct access to tertiary education at post-secondary non-tertiary level include the same type of programmes at upper secondary level.

2. Average age is based on all graduates instead of first-time graduates.

3. Post-secondary non-tertiary programmes exist in the country.

Source: OECD (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-B.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.