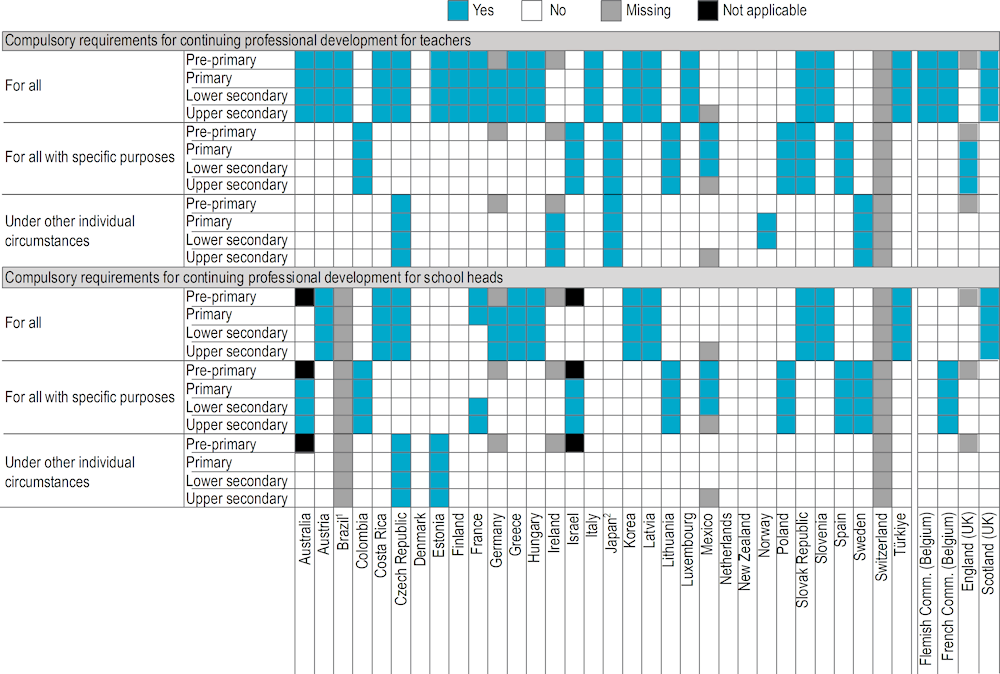

Continuing professional development is compulsory to some extent for teachers of general subjects at least at one level of education in most countries with data, except Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands and New Zealand. It can be either generally compulsory for all teachers as a regular part of their work, or for some teachers for specific purposes such as promotion or salary increases, or in some cases, both.

Continuing professional development is compulsory to some extent for heads of schools covering general programmes at various level of education, but in fewer countries than for teachers of general subjects.

Decisions about which compulsory continuing professional development activities teachers will undertake usually involves them and their school management, while the central/state education authorities are more commonly involved in decisions about the compulsory continuing professional development of school heads.

Education at a Glance 2022

Indicator D7. How extensive are professional development activities for teachers and school heads?

Highlights

Context

While initial teacher education provides the foundations for prospective teachers (see Indicator D6), continuing professional development supports teachers at all stages of their careers. For early-career teachers, it helps to ease the transition into the teaching profession as they face various challenges on the job. For teachers with experience, it gives them an opportunity to refresh, develop and broaden their knowledge and understanding of teaching. For teachers becoming school heads, it equips them with the management and leadership skills necessary for their role as school leaders. Above all, continuing professional development of teachers and school heads benefits students. Several studies find that sustained continuing professional development for teachers is correlated with significant learning gains for students (Yoon et al., 2007[1]). Opportunities for continuing professional development activities also help to retain high-quality teachers in the teaching profession, particularly in marginalised schools (Geiger and Pivovarova, 2018[2]).

Continuing professional development of teachers and school heads helps to continuously update and upgrade their skills and practices to adapt to an evolving learning environment: the growing diversity of students, the greater integration of students with special needs and the increasing use of information and communication technologies (ICT). In vocational education and training, it is essential for teachers to be up-to-date with the changing requirements of the modern workplace (OECD, 2005[3]). During the COVID-19 pandemic, professional development activities in digital technology played a key role in helping teachers to adapt to virtual teaching environment (OECD, 2021[4]).

Due to the high importance of continuing professional development, there is a great deal of policy interest around assessing continuing professional development in terms of its availability, cost-effectiveness and impact on teaching practices and student achievement (Hattie, 2008[5]; Yoon et al., 2007[1]).

Figure D7.1. Requirements for continuing professional development for teachers and school heads (2021)

For teachers teaching general subjects and school heads of general programmes in public institutions

1. Year of reference differs from 2021. Refer to the source table for more information.

2. Compulsory requirement for all teachers with specific purposes will be abolished as of 1 July 2022.

Source: OECD (2022), Tables D7.1 and D7.2. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-D.pdf).

Other findings

The majority of countries and other participants with available data require both compulsory and non-compulsory professional development activities of teachers and school heads to be planned (but not exclusively) in the context of their school’s development priorities.

In nearly all countries, professional development activities are provided to teachers and school heads by more than one type of provider, including public education authorities and related bodies, private entities, and higher education institutions.

Teachers and school heads receive more often support (through financial subsidies, paid leave and/or to cover for their lessons via substitute staff) for compulsory professional development, than for non-compulsory professional development. For lower secondary teachers of general subjects, 17 countries and other participants fully subsidise the cost of compulsory professional development activities but only 6 do so for non-compulsory professional development.

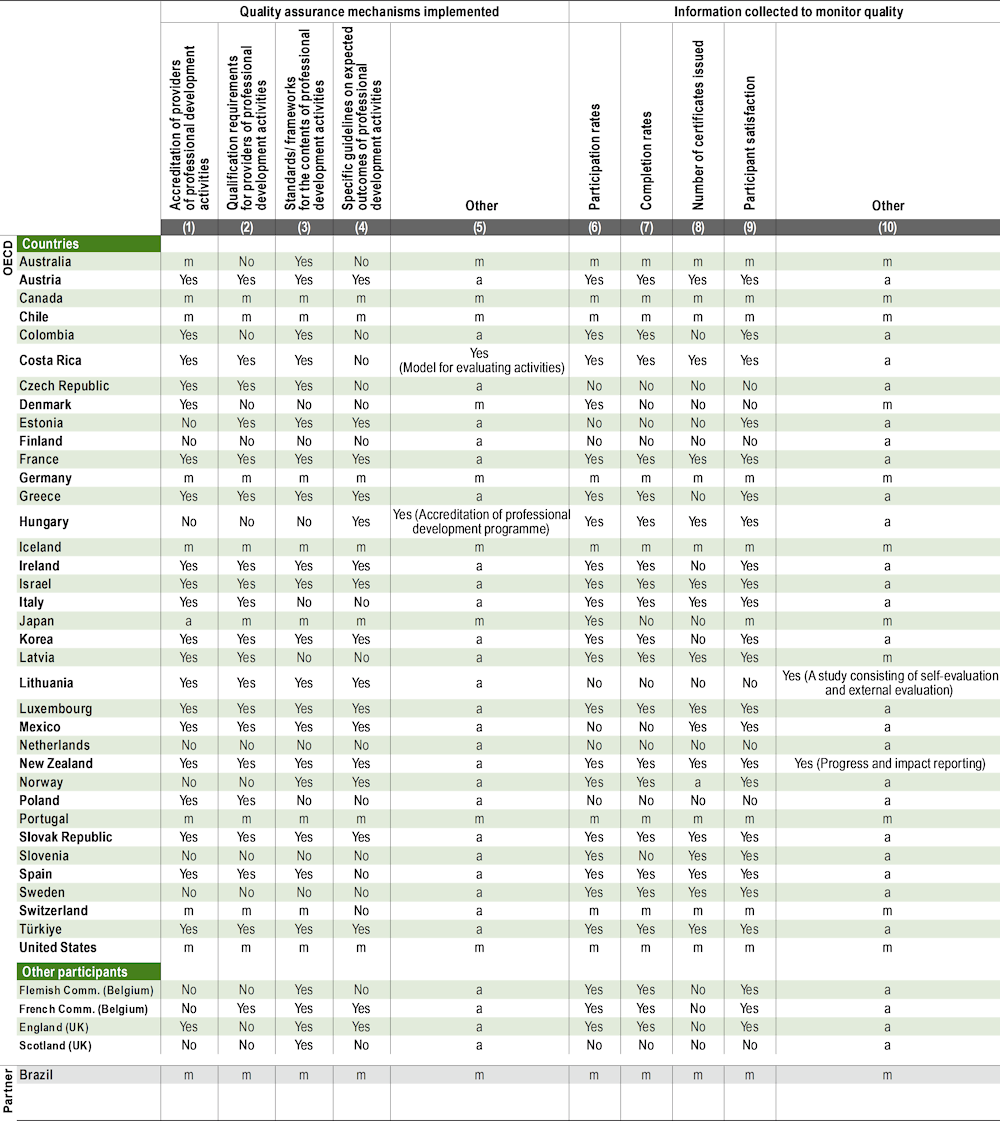

Monitoring of professional development activities is widely implemented across countries with available data, but evaluation is less often required by national regulations. Popular monitoring mechanisms include establishing standards and frameworks for the content of professional development activities, accrediting professional development providers, and setting qualification requirements for professional development providers.

Analysis

Continuing professional development for teachers

Continuing professional development provides teachers with opportunities for learning throughout their careers in education. It can encompass a whole range of activities: formal courses, seminars, conferences and workshops, online training, and formalised mentoring and supervision.

The requirement for professional development covers all levels of teaching. Professional development is compulsory for teachers of general subjects at all levels of education in 30 out of 35 countries and other participants with available data. Only in Norway do teachers of general subjects face different requirements depending on the level of education they teach: only primary and lower secondary teachers are required to update their skills and knowledge in certain subject areas (Figure D7.1).

The requirements are also similar for general and vocational secondary teachers in most countries and other participants with data, except England (United Kingdom), Finland and Mexico. In England (United Kingdom), this could be related to differences in the type of educational institutions in which they teach. Vocational subjects are only taught in government-dependent private institutions (no teacher in public institutions teaches vocational subjects), while the requirements for teachers of general subjects refer only to teachers in public institutions. In Finland, professional development is compulsory for all upper secondary teachers in general programmes, but not for those in vocational programmes (general and vocational subjects). In Mexico, lower secondary teachers of general subjects are required to take compulsory professional development in order to be promoted, but there is no such requirement for lower secondary teachers of vocational subjects (Table D7.1).

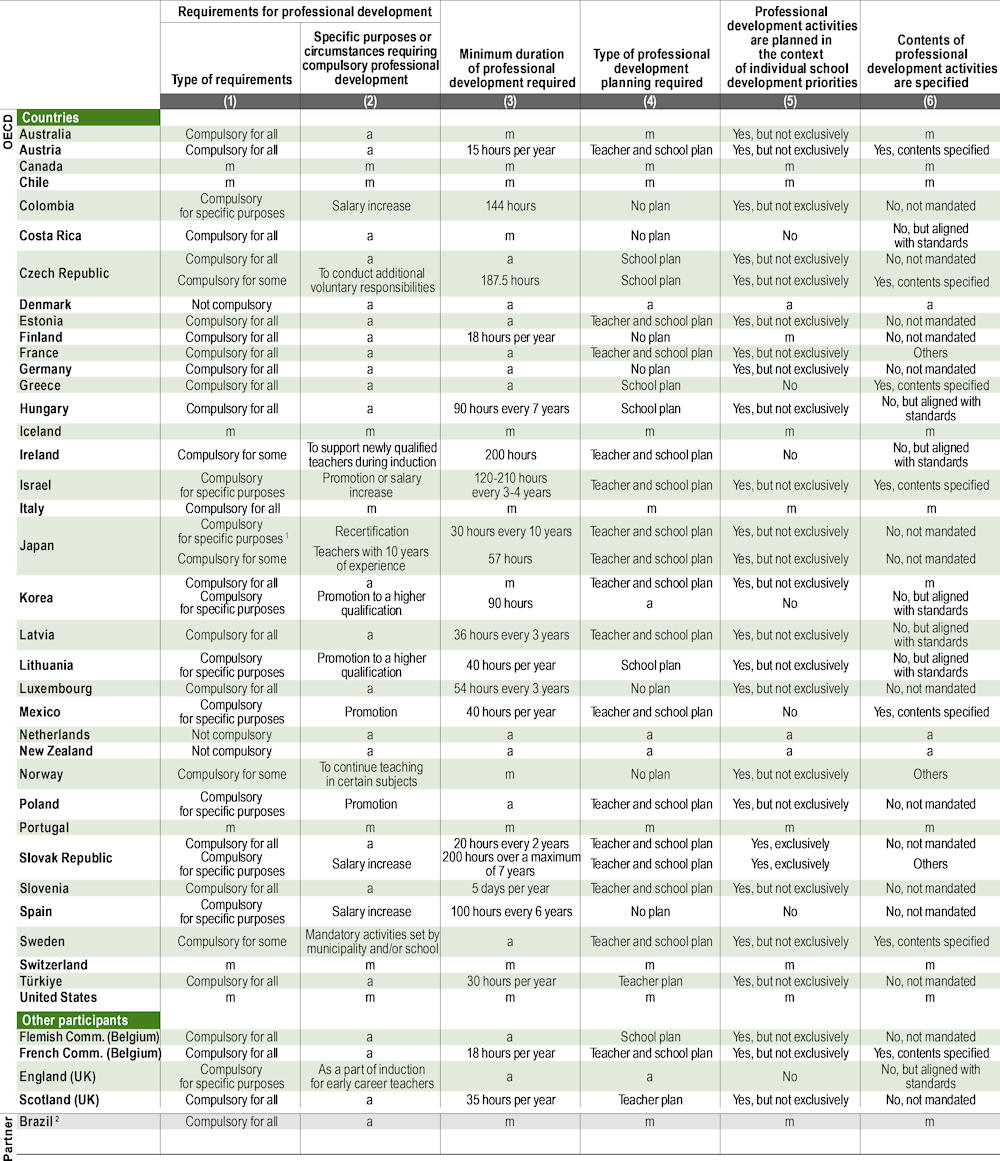

Participation in professional development is compulsory for lower secondary teachers of general subjects to some extent in most countries, except in Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands and New Zealand. Among the 35 countries and other participants with available information, more than half require all teachers to participate in professional development as a regular part of their work. In less than one-third of the countries and other participants, professional development is only compulsory for specific purposes, such as promotion (in Israel, Lithuania, Mexico and Poland), salary increases (in Colombia, Israel and Spain) and/or the completion of induction for early-career teachers (in England [United Kingdom]). In five countries, the requirements depend on teachers’ individual circumstances: professional development is compulsory for individual teachers taking on specific responsibilities (in the Czech Republic and Ireland), for retraining or upskilling experienced teachers (in Japan and Norway), or for specific professional development activities set by municipalities and/or schools (in Sweden) (Table D7.1).

Four countries combine different types of compulsory professional development requirements at all levels of education. In the Czech Republic, requirements that apply to all teachers are combined with those for teachers in specific circumstances (professional development for specific responsibilities that they voluntarily carry out). In Japan, professional development is compulsory for all teachers to be recertified every ten years (but set to be abolished as of July 2022) and also for teachers who have completed the first ten years of their teaching career. Professional development is compulsory for teachers to get a promotion in Korea or salary increase in the Slovak Republic, in addition to the compulsory requirements for all teachers (Table D7.1).

Organisation of compulsory continuing professional development

The organisation of compulsory professional development does not vary by level of education or type of subject (general or vocational) in the majority of countries where the requirements for compulsory professional development are similar across levels and subjects. Then, the analysis that follows focuses on professional development for lower secondary teachers of general subjects, but it is also relevant to other levels of education in many countries (Table D7.1).

Minimum duration requirements

For lower secondary teachers of general subjects, the minimum duration of compulsory professional development is defined at the national level in three-fifths of 31 countries and other participants with some compulsory professional development. In the remainder, the minimum duration requirement varies either across subnational entities (e.g. Australia, Spain, Sweden), across months of the school year (Costa Rica), depending on teachers’ individual circumstances (Norway) or is not clearly defined in national regulations (e.g. Estonia, Germany, Greece and Poland) (Table D7.1).

Depending on the requirements on teachers, conditions about how long they must spend on compulsory professional development activities can be defined in different ways. Of the 20 countries and other participants requiring all lower secondary teachers of general subjects to undertake professional development, one-half set a minimum duration, although this is not defined for a similar period of reference in different countries. Six define a minimum annual duration, while the other four define the minimum duration over a longer time period. The minimum annual duration (or annual average for countries using a longer reference period) ranges from 10 hours in the Slovak Republic (20 hours every 2 years) to 5 days in Slovenia (Table D7.1).

Among the 14 countries and other participants where professional development is compulsory for a specific purpose or depends on individual circumstances (including 3 countries where there is also compulsory professional development for all teachers), more than two-thirds define a minimum duration. The minimum duration for compulsory professional development for specific purposes is generally defined in a recurring fashion (e.g. 100 hours every 6 years in Spain). In contrast, professional development which is compulsory under individual circumstances is usually required only once during a teacher’s career – for example, in Ireland teachers are required to take 200 hours of professional development before taking on responsibility for the induction of new teachers (Table D7.1).

Planning of activities

Planning of professional development activities, whether at the school level or the individual teacher level or both, is often required in countries where professional development is compulsory for some or all teachers. Among the 31 countries and other participants where some compulsory professional development is required for lower secondary teachers of general subjects, about two-thirds have central regulations requiring teacher-level and/or school-level planning. The most common requirement is a plan for both individual teachers and schools. Five countries and other participants only require a school-level plan, while in Scotland (United Kingdom) and Türkiye, only individual teachers’ plans are required (Table D7.1).

Most countries require compulsory professional development activities to be planned in the context of individual school development priorities. These activities must be planned (but not exclusively) in the context of individual school development priorities in about three-quarters of the countries and other participants for lower secondary teachers of general subjects. In the Slovak Republic, plans must be developed exclusively in this context. In seven countries, professional development activities can be planned independently from school development priorities and in Finland it can be decided locally. Four countries require professional development activities to be planned in the context of individual school development priorities even though they do not formally require these activities to be planned in the first place (Table D7.1).

The planning of compulsory professional development activities could take into account the requirements related to the contents of compulsory professional development activities by the relevant education authorities (Box D7.1).

Box D7.1. Content of compulsory professional development activities for teachers and school heads

The contents of school heads’ and teachers’ compulsory professional development activities are very similar across different levels of education with the same participation requirements. The analysis that follows focuses on lower secondary teachers of general subjects and school heads of schools covering lower secondary general programmes only.

For teachers, less than half of the countries with some compulsory professional development requirements mandate the content of these activities or align them with established standards at the national/central level. The contents are mandated in 7 out of 31 countries and other participants while in 7 others, the contents are not mandated, but they still have to be aligned with established national or central standards (Table D7.1).

In all of these 14 countries except Sweden, central/state education authorities are responsible for decisions about the contents of teachers’ professional development activities. Moreover, the central/state education authority is often the only level of authority involved. However, in Sweden, these decisions are taken at a more local level, with the local/municipal education authority and schools responsible for deciding the contents (Table D7.5, available on line).

Where the content of compulsory professional development activities is mandated or specified in a way, it usually includes some form of formalised teacher collaboration activities. Collaboration can occur at individual school level (in all countries and other participants with some form of formalised teacher collaboration), as well as outside school, such as at a municipal/local level (in six countries and other participants) or at a central level (in Costa Rica, Hungary and Israel) (Table D7.1).

The mandated contents of compulsory professional development cover teaching-related tasks more often than non-teaching ones. In particular, all the countries and other participants which mandate content include teaching/pedagogical methods (including teaching pupils with special needs) and the ICT skills required for teaching tasks (Figure D7.2).

Note: The French Community of Belgium and England (United Kingdom) are included in the number of countries and other participants.

Tasks and responsibilities are ranked in the descending order of occurrence for teachers, by type of tasks (teaching and non-teaching tasks).

Source: OECD (2022), Tables D7.1 and D7.2. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-D.pdf).

Regardless of the mandated contents of compulsory professional development activities of teachers, the COVID-19 crisis has increased teachers’ need for training in ICT tools to support their increased use in teaching in many OECD countries (OECD, 2021[4]).

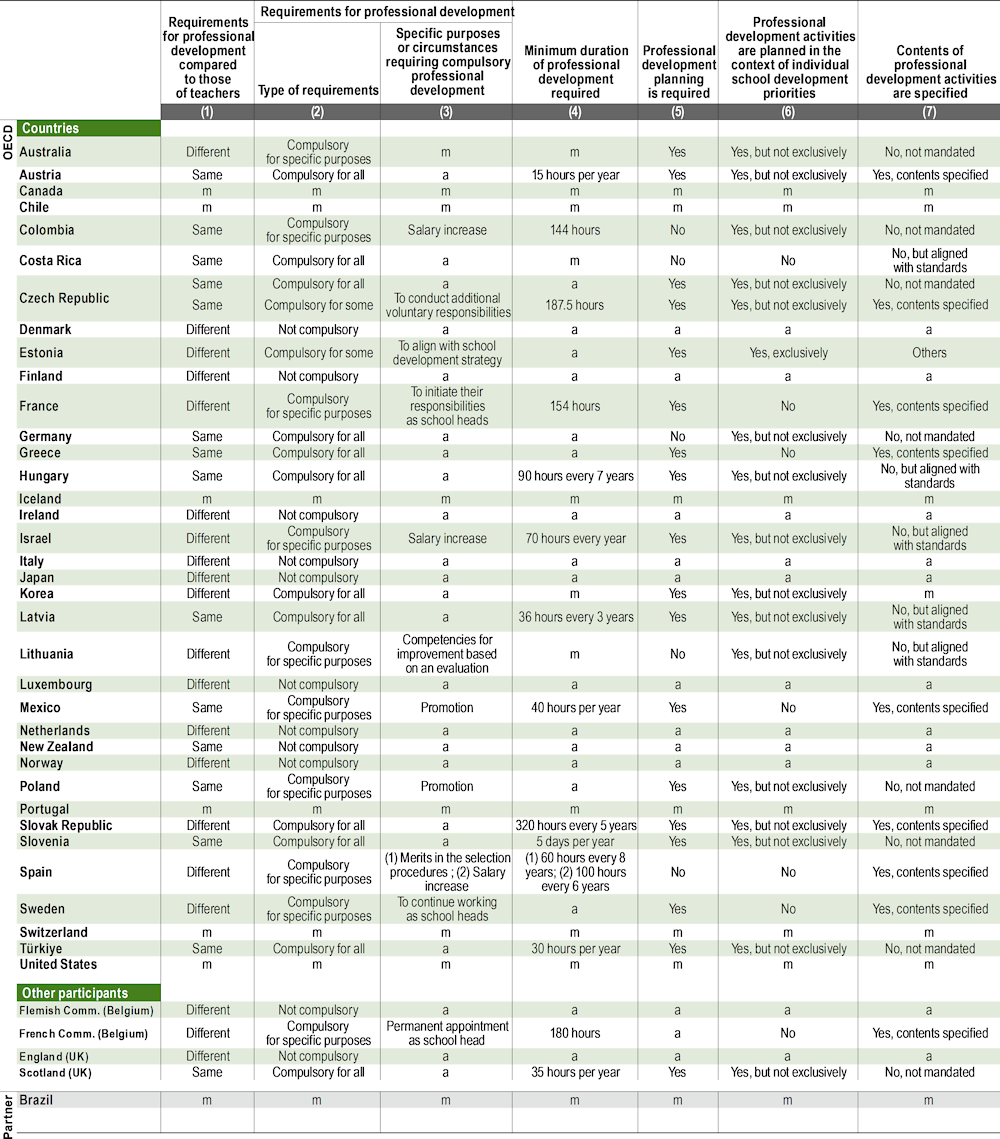

For school heads, the contents of their compulsory professional development activities are mandated in nine countries and other participants. In five other countries, contents are not mandated but they still have to be aligned with established standards (Table D7.2).

As with teachers, the central/state education authority takes responsibility for setting standards or content areas of compulsory professional development activities for school heads where the contents are either mandated or must be aligned with established standards, and it is the only responsible authority in nine countries and other participants. Other bodies such as subnational education authorities or school heads’ professional organisations are not usually involved (Table D7.6, available on line).

Where the contents of their compulsory professional development activities are mandated, they often cover management skills and leadership. In a few countries, the contents also include teaching/pedagogical methods (including teaching students with special needs) and ICT skills for teaching, which help school heads with their teaching responsibilities (Figure D7.2).

Deciding which activities are undertaken

Teachers and school management are usually involved in decisions about the compulsory professional development activities undertaken by individual teachers. In about two-fifths of the countries and other participants with some compulsory professional development for lower secondary teachers of general subjects, teachers propose the activities they want to do, and the school management (together with an education authority in some cases) validates these choices (i.e. accept or reject the proposal) or makes an autonomous decision. This process can help to ensure that teachers’ professional development activities are at least partially consistent with the school’s development priorities. In five other countries, teachers decide or validate the choice of activity, but the school management also validates these choices. In these countries, the content of these activities needs to be aligned (at least to some extent) with schools’ development priorities. In Greece, Mexico and Spain, the education authorities at the national or regional levels rather than the school management have responsibility for validating or deciding, possibly because in these countries, activities do not have to be planned within the context of individual school development priorities (Figure D7.3, Table D7.1 and Table D7.5, available on line).

Note: The Flemish and French Communities of Belgium, England (United Kingdom) and Scotland (United Kingdom) are included in the number of countries and other participants. Countries and other participants are counted multiple times if more than one role is undertaken. Therefore, the total number of countries and other participants may be higher than the number of countries and other participants with data.

Source: OECD (2022), Tables D7.5 and D7.9 (web only). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-D.pdf).

Decision making about individual teachers' compulsory professional development activities is similar across different levels of education and between teachers of general and vocational subjects in nearly all countries. However, in Austria, the decision making depends on the level of education. The school management and the inspectorate propose compulsory professional development activities for pre-primary teachers, and teachers decide whether to undertake them. In contrast, at primary and secondary levels, teachers propose professional development activities, while the school management decide whether the teachers should undertake them. In Ireland, teachers propose professional development activities and the school management and central education authorities decide on which activities primary teachers have to take, but only central education authorities decide for secondary teachers (Table D7.5, available on line).

Organisation of non-compulsory continuing professional development activities

The organisation of non-compulsory professional development activities for lower secondary teachers of general subjects is similar to those of teachers at other levels of education, except in Austria, Brazil, France, Israel, the Netherlands and Sweden. At secondary level, it also differs little between teachers of general and vocational subjects. In Japan, the requirements vary between upper secondary teachers in general and vocational programmes (Table D7.9, available on line).

Planning of activities

In most countries, teachers’ non-compulsory professional development activities should be planned (but not exclusively) in the context of individual school development priorities. For lower secondary teachers of general subjects, this is the case in 22 out of 35 countries and other participants. In the remaining countries, there is no requirement on the planning of these activities (in nine countries and other participants) or the requirements may differ across subnational entities and/or schools (e.g. Australia and Finland) (Table D7.9, available on line).

Requirements on planning of non-compulsory professional development activities do not differ from planning of compulsory activities for all teachers, except in a few countries. In Greece, compulsory professional development activities for all teachers do not need to be planned in the context of individual school development priorities, but non-compulsory activities do. The opposite is the case in the Czech Republic, Estonia and the Slovak Republic. In Denmark, Italy and New Zealand, where there is no requirement for compulsory professional development, non-compulsory professional development activities do have to be planned at least partially in the context of individual school development priorities (Table D7.1 and Table D7.9, available on line).

Deciding which activities are undertaken

Similarly to decisions about compulsory professional development activities, teachers and school managements are the main stakeholders involved in the decisions on non-compulsory professional development activities undertaken by individual teachers (Figure D7.3).

However, the roles of teachers and school management differ between compulsory and non-compulsory activities. For example, lower secondary teachers of general subjects have full autonomy to decide which activities to undertake in 21 out of 35 countries when it comes to non-compulsory activities, but in only 8 out of 31 countries when it comes to compulsory activities. Similarly, proposals about teachers’ non-compulsory professional development activities are usually made by school management and/or education authorities (generally at central/state level), whereas proposals for compulsory activities are also made by teachers (Tables D7.5 and D7.9, available on line).

School management often validate the choice of non-compulsory professional development activities, as is the case with compulsory activities, but in a smaller number of countries. The choice of non-compulsory activities undertaken by teachers needs to be validated by school management in a little less than one-third of countries (Figure D7.3).

Continuing professional development for school heads

Professional development is compulsory, at least to some extent, for the heads of schools with only general programmes in about two-thirds of the 34 countries and other participants with data. This share is lower than for teachers of general subjects. Eleven countries and other participants do not require any school heads to participate in professional development activities. Professional development requirements for school heads do not generally vary by level of education, which may simplify the implementation of these requirements considering that school heads may lead schools covering different levels of education. In Mexico, there is no difference between levels of education (for which data are available), but heads of lower secondary schools with general programmes are required to undertake professional development for promotion, whereas there is no such requirement for heads of schools with only vocational programmes (Figure D7.1 and Table D7.2).

Requirements for school heads vary across countries. Taking schools covering only general programmes at lower secondary level as an example, professional development activities are compulsory for all school heads in 12 countries and other participants, and only compulsory for specific purposes in 10. In two countries they are compulsory for some school heads depending on their individual circumstances: when they have additional voluntary responsibilities such as counselling students (in the Czech Republic) or to align with the school development strategy (in Estonia). The Czech Republic is the only country with two types of compulsory professional development requirements for school heads (for all school heads and for specific individual circumstances), and it is also one of the countries with two types of professional development requirements for teachers (Table D7.1 and Table D7.2).

Organisation of compulsory continuing professional development activities

Only a few countries have different requirements for the organisation of compulsory professional development activities for school heads depending on the level of education or type of programme. In Austria, pre-primary school heads have different professional development requirements from their peers at other levels of education, in Hungary the requirements for the heads of schools covering upper secondary vocational programmes are different from those covering general programmes or other levels of education, and in Türkiye, pre-primary and primary school heads have different requirements from their counterparts in secondary schools. Then, the analysis that follows focuses on professional development for heads of schools covering lower secondary general programmes only, but it is also relevant to other levels of education and programmes in most countries (Table D7.2).

Minimum duration requirements

The minimum duration of compulsory professional development for school heads is defined in the regulations of 14 countries and other participants. The annual minimum duration of professional development required for all school heads (or an average per year if defined over a period of years) ranges from 12 hours in Latvia (36 hours every 3 years) to 64 hours in the Slovak Republic (320 hours every 5 years). For professional development required for specific purposes, the minimum duration reaches 180 hours in the French Community of Belgium (to obtain the certification to be permanently appointed as a school head) (Table D7.2).

Planning of activities

School heads are required to undertake professional development planning in about three-quarters of the countries and other participants where they have some compulsory professional development requirements. In a majority of them, professional development activities are planned (but not exclusively) in the context of individual school development priorities. In a few countries, school heads are not required to plan their professional development activities but these are planned (but not exclusively) in the context of individual school development priorities. Only in Estonia must compulsory professional development be planned exclusively in the context of individual school development priorities because individual professional development has to be based on each school’s development strategy (Table D7.2).

Deciding which activities are undertaken

Central/state education authorities have full autonomy to decide which compulsory professional development activities are undertaken by individual school heads in 10 of the 23 countries and other participants with some compulsory professional development requirement. In most of these countries, the school management does not play any role in the decision making. In four other countries, the school management has autonomy to decide on compulsory activities, although the local/municipal education authority validates these decisions in two of them (in Hungary and Lithuania). In the remaining nine countries and other participants, neither central/state education authorities nor school management make decision in full autonomy, but one or more stakeholders can propose, validate choices, or take other roles in these decisions (Table D7.6, available on line).

Organisation of non-compulsory continuing professional development activities

Requirements on the organisation of non-compulsory professional development activities for school heads are the same across levels of education and types of academic programmes in most countries and other participants with available data. These requirements only differ from the arrangements in lower secondary general education in Austria (pre-primary), Denmark (pre-primary and upper secondary general programmes) and Hungary (upper secondary vocational programmes) (Table D7.10, available on line).

Planning of activities

It is quite common to align plans for non-compulsory professional development activities with individual school development priorities. For example, heads of schools covering lower secondary general programmes are required to plan these activities (but not exclusively) in the context of individual school development priorities in about three-fifths of the 34 countries and other participants with data, and exclusively in the context of individual school development priorities in France. Non-compulsory activities can be planned independently of school development priorities in eight countries and other participants (Table D7.10, available on line).

Deciding which activities are undertaken

Stakeholders play slightly different decision-making roles when comparing the compulsory and non-compulsory professional development activities undertaken by individual school heads. For heads of schools covering lower secondary general programmes only, decisions on which non-compulsory professional development activities they will undertake are taken autonomously by school management in 11 countries and other participants, and by the school heads themselves in Estonia and Italy. In 8 of these 13 countries, school heads are not required to undertake compulsory professional development activities, and even when required to do so, neither school management nor school heads have autonomy to decide about compulsory activities. In Finland, where school heads have no compulsory professional development requirements, decisions about which non-compulsory activities they undertake are made in agreement between school heads and their employers (Tables D7.6 and D7.10, available on line).

Education authorities at various levels (i.e. central/state, regional/sub-regional and/or local/municipal) can be involved in decision making, either deciding which activities school heads will undertake, proposing activities or validating choices about activities. Their most common role is proposing activities, seen in about half of the countries and other participants with data (Table D7.10, available on line).

Factors supporting continuing professional development for teachers and school heads

A number of factors can affect the participation of teachers and school heads in professional development: the range of providers, access to information about the existence and contents of professional development opportunities, and the financial support available to participants and their schools. As financial support for professional development can be limited and high-quality training is not guaranteed in all professional development activities, quality assurance mechanisms, such as monitoring and evaluation, can help with decisions about the best way to manage limited resources for professional development activities.

Providers of continuing professional development activities

All countries and other participants have more than one type of body or institution providing professional development activities for teachers. However, for school heads, a few countries have only one type of provider of professional development activities at some levels of education: in Austria at primary and lower secondary levels, in France at secondary level and in Hungary at vocational upper secondary level (Tables D7.7 and D7.8, available on line).

Providers of professional development activities can be either public or private entities, although no information was collected on the prevalence of either. In most countries, there is at least one type of provider in the public education system (outside of schools), such as education authorities at different levels of government, public agencies for teachers’ professional development, inspectorates, professional organisations, and teachers’ or school heads’ unions. In more than three-quarters of the countries with data, private companies provide professional development activities to teachers and to school heads (Tables D7.7 and D7.8, available on line).

Higher education institutions are among the most common type of provider of professional development activities to teachers and school heads. They play this role in nearly all countries except Australia (for teachers at all levels of education) and Hungary (for upper secondary teachers of vocational subjects and heads of schools at vocational upper secondary level). They are even the only providers of professional development for school heads covering primary and lower secondary levels in Austria and for school heads covering lower and upper secondary levels in France. Box D7.2 gives some examples of the roles that higher education institutions play in providing professional development to teachers and school heads (Tables D7.7 and D7.8, available on line).

Box D7.2. Role of higher education institutions in continuing professional development of teachers and school heads

Higher education institutions are not only the main providers of initial teacher education programmes in most countries (see Indicator D6), but they also provide continuing professional development activities for teachers and school heads in many OECD countries.

Higher education institutions provide activities that are formal and academic in nature. In Norway, for example, teachers of specific subjects (particularly those with an older teaching qualification) are required to take courses provided by higher education institutions in order to meet new competence requirements. During the academic year 2017/18, about 8% of teachers of pre-primary, primary and secondary general programmes in Norway were enrolled in such courses. In Slovenia, higher education institutions offer study programmes to teachers who wish to teach additional subjects.

Higher education institutions may also be involved in the development of professional development activities. For example, the central education authority collaborated with higher education institutions to develop an online skill development course for new school heads in Denmark and a system of in-service training courses for teachers and school heads in Estonia.

Source: 2021 OECD-INES-NESLI survey on professional development of teachers and school heads.

Individual schools and initial teacher education institutions (which could include higher education institutions) also provide professional development activities to teachers in most countries with available information. Other providers for teachers and school heads include privately run continuing education institutions (Estonia), professional development organisations run by the school organising authorities (the Flemish Community of Belgium), different institutions cooperating such as Rectorats and the Regional Directorate of Cultural Affairs (France), Education Centres and Education and Training Boards (Ireland), and non-governmental organisations (Slovenia) (Tables D7.7 and D7.8, available on line).

The types of providers available are similar across levels of education for teachers (of general subjects), except in Austria, Israel, Latvia and Mexico, and for school heads (of schools covering general programmes only), except in Austria, Denmark and France. At secondary level, the types of providers are also similar between teachers of general and vocational subjects, except at lower secondary level in England (United Kingdom) and Mexico, and at upper secondary level in Brazil, England (United Kingdom), Estonia and Hungary. In Japan, the types of providers vary between upper secondary teachers in general and vocational programmes. Providers for school heads are similar for schools with general programmes, vocational programmes and both, except in England (United Kingdom) and Hungary (Tables D7.7 and D7.8, available on line).

Bodies disseminating information on continuing professional development activities

In most countries and other participants with available information, several bodies usually disseminate information about professional development activities for teachers and for school heads at any level of education. However, only one type disseminates this information for teachers in Finland and the Slovak Republic, and for school heads in Finland, the French Community of Belgium and the Netherlands. This is also the case at specific levels of education (for teachers or school heads) in Denmark and Hungary (Tables D7.7 and D7.8, available on line).

Information on professional development activities is often disseminated by education authorities and school managements. Central/state education authorities disseminate this information in most countries and other participants with data and regional/sub-regional and/or local/municipal education authorities do so in about two-thirds of them. School managements disseminate the information to teachers in about nine out of ten countries and other participants with data, and to school heads in about two-thirds of them (Tables D7.7 and D7.8, available on line).

Other types of bodies also collect and circulate information on professional development activities, but they vary across countries: for example, inspectorates have this role in less than one-third of countries and other participants with data, teachers’ unions collect and circulate information for teachers in France and New Zealand, and tertiary or other educational institutions collect and circulate information for teachers and school heads in Latvia and Slovenia (Tables D7.7 and D7.8, available on line).

The types of bodies in charge of disseminating information to teachers of general subjects and to school heads of schools covering general programmes are similar across all levels of education in most countries, except Austria, Denmark and Mexico. At secondary level, they are also similar between teachers of general and vocational subjects, except at lower secondary level in England (United Kingdom) and Mexico, and at upper secondary level in England (United Kingdom), Estonia and Hungary. In Japan, they vary between upper secondary teachers in general and vocational programmes. Similar bodies also disseminate information for school heads, whatever the type of programmes covered in schools (general or vocational), except at lower secondary level in England (United Kingdom) and Mexico, and at upper secondary level in England (United Kingdom) and Hungary (Tables D7.7 and D7.8, available on line).

Funding and support strategies

Participation in professional development activities depends on teachers and school heads being able to fit these activities into their regular work schedule, and on the financial costs incurred by teachers, school heads or schools. In 2018, more than 40% of teachers and more than one-third of school heads reported that time conflicts with their work schedule and/or the high cost of professional development activities were barriers to participating in professional development, on average across the OECD countries in the Teaching and Learning International Survey 2018 (OECD, 2019[6]). Therefore, public funding and support strategies to share or subsidise the costs of professional development activities could encourage staff to engage in professional development.

Across the OECD countries and other participants with available data, funding and support strategies for professional development activities for teachers of general subjects are very similar for all levels of education. There are differences in support strategies for compulsory professional development depending on the level of education in Austria, Estonia, the Flemish Community of Belgium and France. For non-compulsory activities, the strategies differ across levels in Israel and the Netherlands (Tables D7.5 and D7.9, available on line).

Note: The Flemish and French Communities of Belgium, England (United Kingdom) and Scotland (United Kingdom) are included in the number of countries and other participants. For two countries with more than one response, the most representative response has been selected.

Source: OECD (2022), Tables D7.5 and D7.9 (web only). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-D.pdf).

Funding and support strategies for teachers differ substantially between compulsory and non-compulsory professional development, with much more widespread support for compulsory activities than for non-compulsory ones (Figure D7.4).

The government fully covers the costs of compulsory professional development activities (including the cost of participation, paid leave of absence and the cost of substitute teachers) for lower secondary teachers of general subjects in about half of the 31 countries and other participants with compulsory professional development activities, and partly covers these costs in two-fifths of them. In comparison, the government fully covers the costs of non-compulsory professional development activities in less than one-fifth of the 35 countries and other participants with available information, and partly covers them in about half of them. Seven countries and other participants do not subsidise the costs incurred by non-compulsory activities at all, but at least partly cover the costs of compulsory activities (Figure D7.4).

All the countries and other participants with available information at least partially cover the cost of participation (the fees for participating in professional development activities) for both compulsory and non-compulsory professional development activities of lower secondary teachers of general subjects. Nearly three-quarters fully cover this cost for compulsory activities while only about one-quarter do for non-compulsory activities. Where these activities are compulsory for all teachers, they are fully covered by slightly more countries than where they are only compulsory for specific purposes or for teachers in particular circumstances (Figure D7.4 and Tables D7.5 and D7.9, available on line).

Schools are not usually allocated a separate budget for professional development. At lower secondary level, schools have a separate budget for both compulsory and non-compulsory professional development in only three countries (the budget may not necessarily distinguish between the two). In five countries and other participants, schools receive a separate budget just for compulsory professional development and in six they receive one just for non-compulsory professional development. However, it may not be necessary to allocate specific school budgets in systems where the budget for professional development is organised at the central level (e.g. for compulsory professional development for all teachers in the French Community of Belgium, Greece and Israel). In a few countries, the allocation of budget for non-compulsory professional development is a local/municipal level decision, so there is no top-level regulation on this matter (Tables D7.5 and D7.9, available on line).

Teachers who participate in professional development activities receive paid leave of absence in most countries with data, although the number of occasions is limited in the majority of these countries. The availability of paid leave differs between compulsory and non-compulsory activities: fewer countries always or often provide paid leave of absence to lower secondary teachers of general subjects attending non-compulsory activities (6 countries and other participants) than for compulsory activities (11 countries and other participants) (Figure D7.4).

The cost of substitute teachers is also covered in most countries and other participants with data, although the majority only sometimes offer this support. Three countries and other participants do not need to provide substitute teachers because professional development activities do not affect students’ timetables, either because they are held outside school hours (e.g. Greece and Mexico) or because there are days when schools are closed for teachers’ professional development activities (e.g. the French Community of Belgium) (Figure D7.4).

The funding and support strategies for school heads’ professional development are similar to those for teachers. Nevertheless, in less than half of the 35 countries and other participants with data, the level or availability of funding and support differ between teachers and school heads in at least one aspect. For example, in Israel, both teachers and school heads are required to undertake professional development to get a salary increase, but teachers are fully subsidised for this compulsory professional development, and school heads only partially so (Tables D7.5, D7.6, D7.9 and D7.10, available on line).

Quality assurance mechanisms for continuing professional development activities for teachers

Monitoring of professional development activities for teachers

Quality assurance mechanisms are available to monitor professional development activities for teachers at all levels of education in more than three-quarters of the 34 countries and other participants with data. Among them, the most common mechanism is standards/frameworks for the contents of professional development activities, used in more than four out of five cases. Accrediting providers of professional development activities and qualification requirements for providers are implemented in about three-quarters of cases and guidelines on the expected outcomes of professional development activities are implemented in less than two-thirds of cases. Some countries with decentralised education systems monitor professional development activities at subnational level, so practices could vary within the country. In Brazil for example, there is no national policy for monitoring the quality of teachers’ professional development activities, but some municipalities and states have education systems which do have a policy (Table D7.3).

A majority of countries and other participants with data on the monitoring of professional development activities collect some quantitative data that could be used to monitor the quality of these activities. The two commonest type of data are participation rates in professional development activities and participants’ satisfaction levels. These are collected in more than three-quarters of them. Completion rates of professional development activities are also widely collected, followed by the number of certificates issued after professional development activities (in more than half of countries and other participants where some type of data is collected). More than two-fifths of the countries and other participants collect all four of these types of data, while Denmark (at primary and lower secondary levels), Estonia and Lithuania collect just one type (Table D7.3).

The collected data are used for various purposes, but about three-quarters of the 28 countries and other participants (where some data is collected) report that they are used to evaluate the effectiveness of formats and resources for professional development activities. Two-thirds use them for identifying and scaling up successful opportunities for professional development and monitoring levels of teachers’ participation in compulsory and non-compulsory professional development activities. More than half collect data to forecast or assess teachers’ skills needs at the system level. Other less widely used purposes included improving future professional development activities (Estonia), identifying outcomes and impacts of national education strategies and priorities (New Zealand), and co-financing professional development programmes (Slovenia) (Table D7.3).

Evaluation of professional development activities for teachers

While most countries monitor professional development activities, central level regulations require evaluations of these activities in nearly half of the 33 countries and other participants with data available. In Australia, Brazil and Switzerland, regulations requiring the evaluation of professional development activities may vary at subnational level. In the remaining countries, there is either no requirement or no explicit requirement (in official documents) for the evaluation of teachers’ professional development activities (Table D7.4, available on line).

Evaluation of professional development activities is the responsibility of the central/state education authorities in two-thirds of the countries and other participants which require it (5-10 countries, depending on the level of education and type of educational programmes). Lower-level education authorities (regional/sub-regional and/or local/municipal education authorities), inspectorates and/or individual schools are responsible in about two-fifths of the countries and other participants. Providers of professional development activities also have responsibility to self-evaluate in more than half of the countries and other participants. Evaluation of professional development activities is a shared responsibility among multiple parties, except in Hungary (where it is only the responsibility of providers of professional development activities for teachers of general subjects) and the Slovak Republic (where it is solely up to individual schools) (Table D7.4, available on line).

Where evaluation of professional development activities is required, the data used are collected through questionnaires or surveys of teachers in more than three-quarters of the countries and other participants. Other methods include impact evaluation studies of professional development activities and a mandatory part of school self-evaluations (both in less than half of the countries and other participants where evaluation is required) and external school evaluations such as inspections (in less than one-third of the countries and other participants where evaluation is required). More than half of the countries collect data through more than one method, while six use only one data collection method for at least one level of education (Table D7.4, available on line).

Nearly all countries and other participants require regular collection of the data used to evaluate professional development activities where such evaluation is required. In Spain and Türkiye, the data are also collected on an ad-hoc basis when needed (Table D7.4, available on line).

Definitions

Compulsory continuing professional development activities refer to continuing professional development activities that are required for a fully qualified teacher or a qualified school head during a school year, as specified in relevant official documents. They can be compulsory for all teachers/school heads as a part of their statutory role, compulsory for all teachers/school heads to satisfy specific purposes (e.g. recertification, salary increases or promotion), and compulsory in the individual circumstances of teachers/school heads (e.g. prerequisite for a specific role in school, retraining targeted for a specific group of teachers).

(Continuing) professional development activities are activities designed to develop an individual’s skills, knowledge and expertise as a teacher or a school head (or more generally, a professional). These activities are formal and can encompass a whole range of activities: formal courses, seminars, conferences and workshops, online training, and mentoring and supervision. It can also refer to formalised collaboration and participation in professional networks. Professional development does not refer to usual teaching and working practices which also are developing them professionally.

Evaluation of professional development activities refer to the formal evaluation of the activities that serve teachers. It does not refer to the evaluation or appraisal of individual teachers.

Coverage

Thirty-six OECD and partner countries and other participants contributed to the 2021 OECD-INES-NESLI survey on professional development of teachers and school heads used to develop this indicator: Australia, Austria, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Czech Republic, Denmark, England (United Kingdom), Estonia, Finland, France, the Flemish and French Communities of Belgium, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Scotland (United Kingdom), the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and Türkiye.

Methodology

See Annex 3 for country-specific notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-D.pdf).

Source

Data are from the 2021 OECD-INES-NESLI survey on professional development of teachers and school heads and refer to the school year 2020/21.

References

[2] Geiger, T. and M. Pivovarova (2018), “The effects of working conditions on teacher retention”, Teachers and Teaching, Vol. 24/6, pp. 604-625, https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2018.1457524.

[5] Hattie, J. (2008), Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203887332.

[4] OECD (2021), The State of Global Education: 18 Months into the Pandemic, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1a23bb23-en.

[6] OECD (2019), TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners, TALIS, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en.

[3] OECD (2005), Teachers Matter: Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers, Education and Training Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264018044-en.

[1] Yoon, K. et al. (2007), Reviewing the Evidence on How Teacher Professional Development Affects Student Achievement.

Indicator D7 Tables

Tables Indicator D7. How extensive are professional development activities for teachers and school heads?

|

Table D7.1 |

Requirements for teachers' professional development (2021) |

|

Table D7.2 |

Requirements for school heads' professional development (2021) |

|

Table D7.3 |

Quality assurance mechanisms implemented for teachers’ professional development activities (2021) |

|

WEB Table D7.4 |

Evaluation of teachers’ professional development activities (2021) |

|

WEB Table D7.5 |

Decision making, support, and standards and content setting for teachers' required professional development activities (2021) |

|

WEB Table D7.6 |

Decision making, support, and standards and content setting for school heads' required professional development activities (2021) |

|

WEB Table D7.7 |

Providers of and information dissemination about teachers' professional development activities (2021) |

|

WEB Table D7.8 |

Providers of and information dissemination about school heads' professional development activities (2021) |

|

WEB Table D7.9 |

Support for teachers' non-compulsory professional development activities (2021) |

|

WEB Table D7.10 |

Support for school heads' non-compulsory professional development activities (2021) |

Cut-off date for the data: 17 June 2022. Any updates on data can be found on line at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-data-en.

Table D7.1. Requirements for teachers' professional development (2021)

For lower secondary teachers (general subjects) in public institutions

Note: Data on pre-primary, primary, lower secondary (vocational subjects) and upper secondary (general or vocational subjects) levels, as well as the tasks and responsibilities covered by the mandated contents and the type of formalised teacher collaboration for compulsory continuing professional development activities (Columns 7 to 25) are available on line (see StatLink below). See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information.

1. Recertification system is set to be abolished as of 1 July 2022.

2. Year of reference 2020.

Source: OECD (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-D.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table D7.2. Requirements for school heads' professional development (2021)

For lower secondary schools heads (general programmes) in public institutions

Note: Data on pre-primary, primary, lower secondary (vocational programmes) and upper secondary (general and/or vocational programmes) levels, as well as the tasks and responsibilities covered in the mandated contents for compulsory continuing professional development (CPD) activities (Columns 8 to 19) are available on line (see StatLink below). See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information.

Source: OECD (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-D.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table D7.3. Quality assurance mechanisms implemented for teachers’ professional development activities (2021)

For lower secondary teachers (general programmes) in public institutions

Note: Data on pre-primary, primary, lower secondary (vocational programmes) and upper secondary (general or vocational programmes) levels are available on line (see StatLink below). See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information.

Source: OECD (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-D.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.