On average across OECD countries, public funds account for 83% of total spending on educational institutions. Private sources are more important at the tertiary level, where they make up 31% of all expenditure compared to just 10% at the non-tertiary levels (primary, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary).

The share of private spending on tertiary educational institutions depends largely on the tuition fees charged to students. More than half of total expenditure comes from private sources in Australia, Chile, Colombia, Japan, Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States, which are mostly countries with comparatively high tuition fees.

Between 2011 and 2019, the average share of private spending on educational institutions remained stable on average across OECD countries. However, the variation over time differs widely across countries, especially at the tertiary level. The largest increases in the share of private expenditure in this period were observed in Poland and Spain at the non-tertiary levels (4 percentage points) and in Colombia at the tertiary levels (14 percentage points).

Education at a Glance 2022

Indicator C3. How much public and private investment in educational institutions is there?

Highlights

Note: International expenditure is aggregated with public expenditure for display purposes.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the share of expenditure on tertiary educational institutions from public sources.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022), Table C3.2. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

Context

Today, more people than ever before are participating in a wide range of educational programmes offered by an increasing number of providers. In the current economic environment, many governments are finding it difficult to provide the necessary resources to support this increased demand for education through public funds alone. In addition, some policy makers argue that those who benefit the most from education – the individuals who receive it – should bear at least some of the costs. While public funding still represents a large part of countries’ investment in education, private sources play an increasingly prominent role at some levels of education.

Public sources dominate much of the funding of primary and secondary education, which is compulsory in most countries. Across OECD countries, the balance between public and private financing varies the most at the pre-primary (see Indicator C2) and tertiary levels of education, where full or nearly full public funding is less common. At these levels, private funding comes mainly from households, raising concerns about equity in access to education. The debate is particularly intense over funding for tertiary education. Some stakeholders are concerned that the balance between public and private funding might discourage potential students from entering tertiary education. Others believe that countries should significantly increase public support such as student loans or grants to students, while others support efforts to increase the funding provided by private enterprises. By shifting the cost of education to a time when students typically start earning more, student loans help alleviate the burden of private spending and reduce the cost to taxpayers of direct government spending.

This indicator examines the proportion of public, private and international funding allocated to educational institutions at different levels of education. It also breaks down private funding into funding from households and other private entities. It sheds some light on the widely debated issue of how the financing of educational institutions should be shared between public and private entities, particularly at the tertiary level. Finally, it looks at the relative share of public transfers provided to private institutions and individual students and their families to meet the costs of tertiary education.

Other findings

While the share of private spending on primary to post-secondary non-tertiary educational institutions is low across the OECD, it can reach high levels in countries such as Colombia and Türkiye (20%), with comparatively low per-capita income levels.

Household spending makes up more than two-thirds of private expenditure on tertiary educational institutions on average across the OECD. However, in Denmark, Finland and Sweden, other sources of private expenditure make up 90% or more of all private spending.

Public-to-private transfers account for 3% or less of education expenditure at the primary, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary levels in all OECD countries. They are considered to be more important at the tertiary level, where they constitute 5% of all expenditure on average across the OECD and make up more than 15% of all expenditure in Australia, Ireland, Korea, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

Analysis

Share of public and private expenditure on educational institutions

The largest share of funding on primary to tertiary educational institutions in OECD countries comes from public sources, although private funding at the tertiary level is substantial. Within this overall OECD average, however, the share of public, private and international funding varies widely across countries. In 2019, on average across OECD countries, 83% of the funding for primary to tertiary educational institutions came directly from public sources and 16% from private sources (Table C3.1). However, in Finland, Iceland, Luxembourg, Norway and Sweden, private sources contribute to less than 5% of expenditure on educational institutions. In contrast, they make up around one-third of educational expenditure in Australia, Chile, Colombia, the United Kingdom and the United States. International sources provide a very small share of total expenditure on educational institutions. On average across OECD countries, they account for 1% of total expenditure, reaching 5% in Estonia (Table C3.1).

Tertiary educational institutions

The high private returns to tertiary education have led a number of countries to ask individuals to make a greater financial contribution to their education at the tertiary level, primarily through tuition fees. Some countries have implemented public financial support mechanisms to ease the burden of these contributions on individuals, although this is not always the case (see Indicator C5). In all OECD countries, the proportion of private expenditure on education after public-to-private transfers is far higher at tertiary level than at lower levels of education. In 2019, on average across OECD countries, 31% of total expenditure on tertiary institutions was sourced from the private sector after transfers (Table C3.1 and Figure C3.2).

1. Figures are for net student loans rather than gross, thereby underestimating public transfers.

2. Year of reference differ from 2019. Refer to the source table for more details.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the proportion of private expenditure on tertiary educational institutions.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022), Table C3.1. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

The share of private funding is strongly related to the level of tuition fees charged by tertiary institutions (see also Indicator C5). In countries where tuition fees tend to be low or negligible, such as Finland, Iceland, Luxembourg and Norway, the share of expenditure on tertiary institutions sourced through the private sector (including subsidised private payments such as tuition fee loans) is less than 10%. In contrast, over 60% of funding on tertiary institutions comes from private sources in Australia, Chile, Colombia, Japan, Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States, which also tend to charge higher tuition fees (Table C3.1).

On average across OECD countries, households account for 72% of private expenditure on tertiary institutions. While household expenditure is the biggest source of private funds in the majority of OECD countries, almost all private funding comes from other private entities in Denmark, Finland and Sweden (Figure C3.2). This private funding mainly consists of spending by businesses for research and development.

Non-tertiary educational institutions

Public funding dominates non-tertiary education in all countries. In 2019, private funding accounted for only 10% of expenditure at primary, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary levels on average across OECD countries, although it exceeded 20% in Colombia and Türkiye. In most countries, the largest share of private expenditure at these levels comes from households and goes mainly towards tuition fees (Table C3.1 and Figure C3.3).

The share of private expenditure on educational institutions varies across countries and according to the level of education. At the primary level, 7% of expenditure on educational institutions comes from private sources on average across OECD countries. However, primary institutions are entirely publicly funded in Norway and Sweden, while 15% or more of funds come from private sources in Chile, Colombia Hungary, Mexico, Spain and Türkiye (OECD, 2022[1]).The share of private funding at lower secondary level is similar to the share at primary level, with around 9% of educational expenditure privately sourced on average across OECD countries. In around two-thirds of OECD countries for which data are available, private expenditure accounts for less than 10% of total expenditure at this level compared to more than 20% in Australia and Türkiye (OECD, 2022[1]).

Upper secondary education relies more on private funding compared to primary and lower secondary levels, reaching an average of 13% across OECD countries. Private sources contribute a similar share to the spending on vocational and general programmes. However, in Germany and the Netherlands, the share of private funding in vocational upper secondary education is at least 30 percentage points higher than in general education. In Germany, private companies have a long tradition of being involved in the provision of dual training (combined work- and school-based programmes), helping to improve the availability of skilled individuals needed in the labour market. On the other hand, in Chile and Türkiye, the share of private funding of general programmes exceeds that of vocational programmes by at least 20 percentage points. In several countries, the share of public funds currently devoted to vocational programmes is the result of various national policy developments on vocational education designed to improve the transition from school to work. For example, in the 1990s, France, the Netherlands, Norway and Spain introduced financial incentives to employers offering apprenticeships to secondary students. As a result, programmes combining work and learning were introduced more widely in a number of OECD countries (OECD, 1999[2]).

Most private expenditure on primary to post-secondary non-tertiary levels of education comes from households. Other private entities, such as businesses, provide only 2% of all education expenditure at these levels of education (corresponding to about 20% of all private education expenditure). The only notable exception in this respect is the Netherlands, where private spending by other private entities is 9% of all educational expenditure, which is more than twice as high as private spending by households. In Türkiye, other private entities also spend 9% of all educational expenditure, but the share of private household spending is even higher, at 16% (Figure C3.3).

Note: International expenditure is aggregated with public expenditure for display purposes.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the proportion of public expenditure.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022), Tables C3.1 and C3.2. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

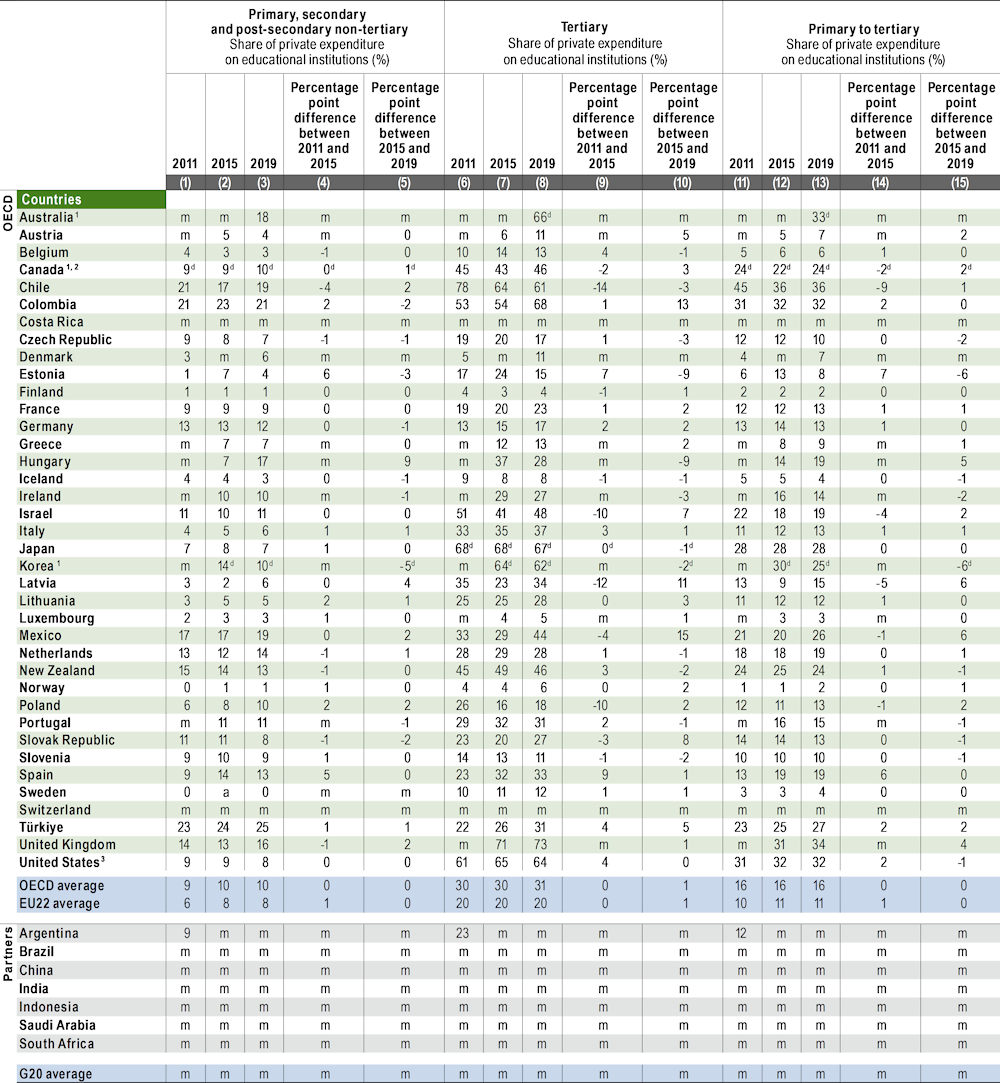

Trends in the share of public and private expenditure on educational institutions

The average shares of public and private expenditure on educational institutions have tended to be relatively stable over time across the OECD. While the importance of private funding is growing, it is at a slow pace (Table C3.3). Increases in the share of private funding were observed in almost half of OECD countries, with Spain showing the largest rise (6 percentage points, mostly between 2011 and 2015 and remaining stable between 2015 and 2019). In contrast, Chile experienced the largest decline in the share of private spending (9 percentage points) between 2011 and 2019, balanced by an equivalent increase from public sources (Table C3.3).

At the non-tertiary levels, Poland and Spain experienced the largest increases in the share of private expenditure, with a gain of 4 percentage points between 2011 and 2019. Data for 2011 are missing for Hungary, but between 2015 and 2019, the share of private spending increased by 9 percentage points. In other countries, there was a moderate decline in the share of private funds during the same period, notably in the Slovak Republic, where the share of private spending fell by 3 percentage points (Table C3.3). At the tertiary level, the increase was greatest in Colombia, where private funding rose from an already high 53% in 2011 to 68% in 2019. In contrast, Chile saw the largest fall in the share of private spending between 2015 and 2019, by 17 percentage points (Table C3.3). However, this might also be due to the statistical effect of the reclassification of some institutions from private to public.

1. Figures are for net student loans rather than gross, thereby underestimating public transfers.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022), Table C3.3. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

While the average share of private spending on tertiary educational institutions grew slightly over the whole period since 2011, individual countries experienced greater fluctuations within that time frame. Figure C3.4 shows the percentage point change in the share of private expenditure from 2011 to 2015 and from 2015 to 2019. Only in seven countries (those in the upper-right quadrant of the figure), did the share increase in both periods. For example, in Spain, the share of private expenditure increased by 9 percentage points between 2011 and 2015, while the increase was only 1 percentage point between 2015 and 2019. In contrast, in 16 countries (in the top-left and bottom-right quadrants), the share of private expenditure increased in one of the two periods and decreased in the other. In Latvia, for example, the share of private expenditure dropped sharply between 2011 and 2015, but increased by nearly the same amount between 2015 and 2019. Finally, in four countries (in the bottom-left quadrant), the share fell in both periods, although at a low rate (Figure C3.4).

Public transfers to the private sector

A large share of government spending goes directly to educational institutions, but governments also transfer funds to educational institutions through various other allocation mechanisms (tuition subsidies or direct public funding of institutions based on student enrolments or credit hours) or by subsidising students, households and other private entities through scholarships, grants or loans. Transfers are classified as transfers to the private sector if the direct recipients are students, households or other private entities. Channelling funding for institutions through students increases competition among institutions for students, which may improve their effectiveness.

At the non-tertiary levels of education, the share of public-to-private transfers is very small, which is partly due to the overall low share of private expenditure at these levels. In 2019, on average across OECD countries, public-to-private transfers represented 1% of the total funds devoted to primary to post-secondary non-tertiary educational levels. The highest share was in the Slovak Republic, where it reached 3% of total educational expenditure (Table C3.2, available on line).

At the tertiary level, however, public transfers to the private sector play an important role in financing tertiary education in some countries (Figure C3.1). In countries where tertiary education is expanding, and particularly in those with high tuition fees, public-to-private transfers are often seen as a means of expanding access for lower income students. However, there is no single allocation model across OECD countries (OECD, 2017[3]). While private spending is largely covered by public transfers in some countries, such as Ireland, government and international support cover a relatively small share of private costs in others. Where public support to students is low, higher needs for private spending may deter some students from participating in tertiary education, even though higher future earnings would make it financially worthwhile to obtain a degree.

In 2019, on average across OECD countries, public-to-private transfers represented 5% of the total funds devoted to tertiary institutions. Countries with the highest transfers are also those that tend to have the highest tuition fees (see Indicator C5). Transfers exceeded 18% of total expenditure on tertiary institutions in Australia, Ireland and the United Kingdom, where annual tuition fees for a bachelor’s programme exceed USD 5 000. In contrast, the share of public transfers was below 1% in countries with no or low fees, such as Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland and Sweden. However, in some countries, such as France, Lithuania, Mexico, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Spain and Türkiye, public transfers to the private sector are low (4% or less) despite high levels of private spending (at least 20%) (Figure C3.1 and Table C3.2).

Provisional data on education expenditure in 2020 are available for a small number of countries. These figures are useful for taking a first comparative look at the overall trends in public and private education funding during the first year of the COVID‑19 health crisis (Box C3.1).

Box C3.1. Provisional data on changes in private funding for education in 2020

Policy responses to the pandemic are posing challenges to government education budgets (OECD, 2021[4]) (OECD, 2021[5]). Public education funding has not substantially changed in the last decade, but the crisis has brought increasing pressure to mobilise additional resources for education. Public funds will be needed to protect students and minimise the learning losses associated with COVID-19 (Al-Samarrai, Gangwar and Gala, 2020[6]). These funds may also need to compensate for potential drops in private education funding. However, lower government revenues are limiting the amount of additional public resources for education that can be mobilised (UNESCO and World Bank, 2021[7]).

Between 2019 and 2020, the share of private funding for primary to post-secondary non-tertiary educational institutions decreased in all countries with available data, declining by 2 percentage points or more in New Zealand and Slovenia. At the tertiary level, the picture was more mixed. Most countries recorded only small changes (whether increases or decreases) of 1 percentage point, but the share of private funding increased by 3 percentage points in Slovenia and decreased by 2 percentage points or more in New Zealand and Norway (Figure C3.5).

Countries are ranked in descending order of the 2019-20 variation at the tertiary level.

Source: OECD/Eurostat (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

In some cases, the fall in the share of private funding for educational institutions in 2020 was associated with reduced government transfers to households and other private entities (Figure C3.5). This was the case in the Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia and Türkiye at primary to post-secondary non-tertiary levels and in New Zealand at both tertiary and non-tertiary levels. In contrast, in Denmark and France the share of private funding for tertiary educational institutions and of public-to-private transfers at this level both increased slightly between 2019 and 2020, while in Norway increased public transfers to the private sector at tertiary level did not lead to an increase in the share of private funding for tertiary educational institutions (Figure C3.5).

In 2020, public funding has helped make up for the drop in the relative share of private funding in all countries with available provisional data, except for Denmark, France and Slovenia, where the opposite was observed at the tertiary level. Increased public funding for education at both tertiary and non-tertiary levels for 2021 was reported by a large majority of countries, nine of which reported a significant increase. Increased public funding during the COVID-19 pandemic has mostly financed investment in infrastructure to improve sanitary conditions (e.g. installation of air filters in classrooms) and additional support for teachers and staff (masks, COVID-19 tests, health care, etc.) (see COVID-19 Chapter and Indicator C4).

Definitions

Initial public, private and international shares of educational expenditure are the percentages of total education spending originating in, or generated by, the public, private and international sectors before transfers have been taken into account. Initial public spending includes both direct public expenditure on educational institutions and transfers to the private sector, and excludes transfers from the international sector. Initial private spending includes tuition fees and other student or household payments to educational institutions, minus the portion of such payments offset by public subsidies. Initial international spending includes both direct international expenditure for educational institutions (for example, a research grant from a foreign corporation to a public university) and international transfers to governments.

Final public, private and international shares are the percentages of educational funds expended directly by public, private and international purchasers of educational services after the flow of transfers. Final public spending includes direct public purchases of educational resources and payments to educational institutions. Final private spending includes all direct expenditure on educational institutions (tuition fees and other private payments to educational institutions), whether partially covered by public subsidies or not. Private spending also includes expenditure by private companies on the work-based element of school- and work-based training of apprentices and students. Final international spending includes direct international payments to educational institutions such as research grants or other funds from international sources paid directly to educational institutions.

Households refer to students and their families.

Other private entities include private businesses and non-profit organisations (e.g. religious organisations, charitable organisations, business and labour associations, and other non-profit organisations).

Public subsidies include public and international transfers such as scholarships and other financial aid to students plus certain subsidies to other private entities.

Methodology

All entities that provide funds for education, either initially or as final payers, are classified as either government (public) sources, non-government (private) sources, or international sources such as international agencies and other foreign sources. The figures presented here group together public and international expenditures for display purposes. As the share of international expenditure is relatively small compared to other sources, its integration into public sources does not affect the analysis of the share of public spending.

Not all spending on instructional goods and services occurs within educational institutions. For example, families may purchase commercial textbooks and materials or seek private tutoring for their children outside educational institutions. At the tertiary level, students’ living expenses and foregone earnings can also account for a significant proportion of the costs of education. All expenditure outside educational institutions, even if publicly subsidised, are excluded from this indicator. Public subsidies for educational expenditure outside institutions are discussed in Indicators C4 and C5.

A portion of educational institutions’ budgets is related to ancillary services offered to students, including student welfare services (student meals, housing and transport). Part of the cost of these services is covered by fees collected from students and is included in the indicator.

Expenditure on educational institutions is calculated on a cash-accounting basis and, as such, represents a snapshot of expenditure in the reference year. Many countries operate a loan payment/repayment system at the tertiary level. While public loan payments are taken into account, loan repayments from private individuals are not, and so the private contribution to education costs may be under-represented.

Student loans provided by private financial institutions (rather than directly by a government) are counted as private expenditure, although any interest rate subsidies or government payments on account of loan defaults are captured as public funding.

For more information, please see the OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018 (OECD, 2018[8]) and Annex 3 for country-specific notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

Source

Data refer to the financial year 2019 (unless otherwise specified) and are based on the UNESCO, OECD and Eurostat (UOE) data collection on education statistics administered by the OECD in 2021 (for details see Annex 3 at https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf). Data from Argentina, the People’s Republic of China, India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and South Africa are from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS).

The data on expenditure for 2011 to 2019 were updated based on a survey in 2021-22, and expenditure figures for 2011 to 2019 were adjusted to the methods and definitions used in the current UOE data collection. Provisional data on educational expenditure in 2020 are based on an ad-hoc data collection administered by the OECD and Eurostat in 2022.

References

[6] Al-Samarrai, S., M. Gangwar and P. Gala (2020), The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Education Financing, https://doi.org/10.1596/33739.

[1] OECD (2022), Education at a Glance Database, OECD.Stat website, https://stats.oecd.org/.

[5] OECD (2021), The State of Higher Education – One Year into the COVID Pandemic, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[4] OECD (2021), The State of School Education: One Year into the COVID Pandemic, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/201dde84-en.

[8] OECD (2018), OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264304444-en.

[3] OECD (2017), “Who really bears the cost of education?: How the burden of education expenditure shifts from the public to the private sector”, Education Indicators in Focus, No. 56, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4c4f545b-en.

[2] OECD (1999), Implementing the OECD Jobs Strategy: Assessing Performance and Policy, The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264173682-en.

[7] UNESCO and World Bank (2021), Education Finance Watch 2021, https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/226481614027788096/education-finance-watch-2021 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

Indicator C3 tables

Tables Indicator C3. How much public and private investment in educational institutions is there?

|

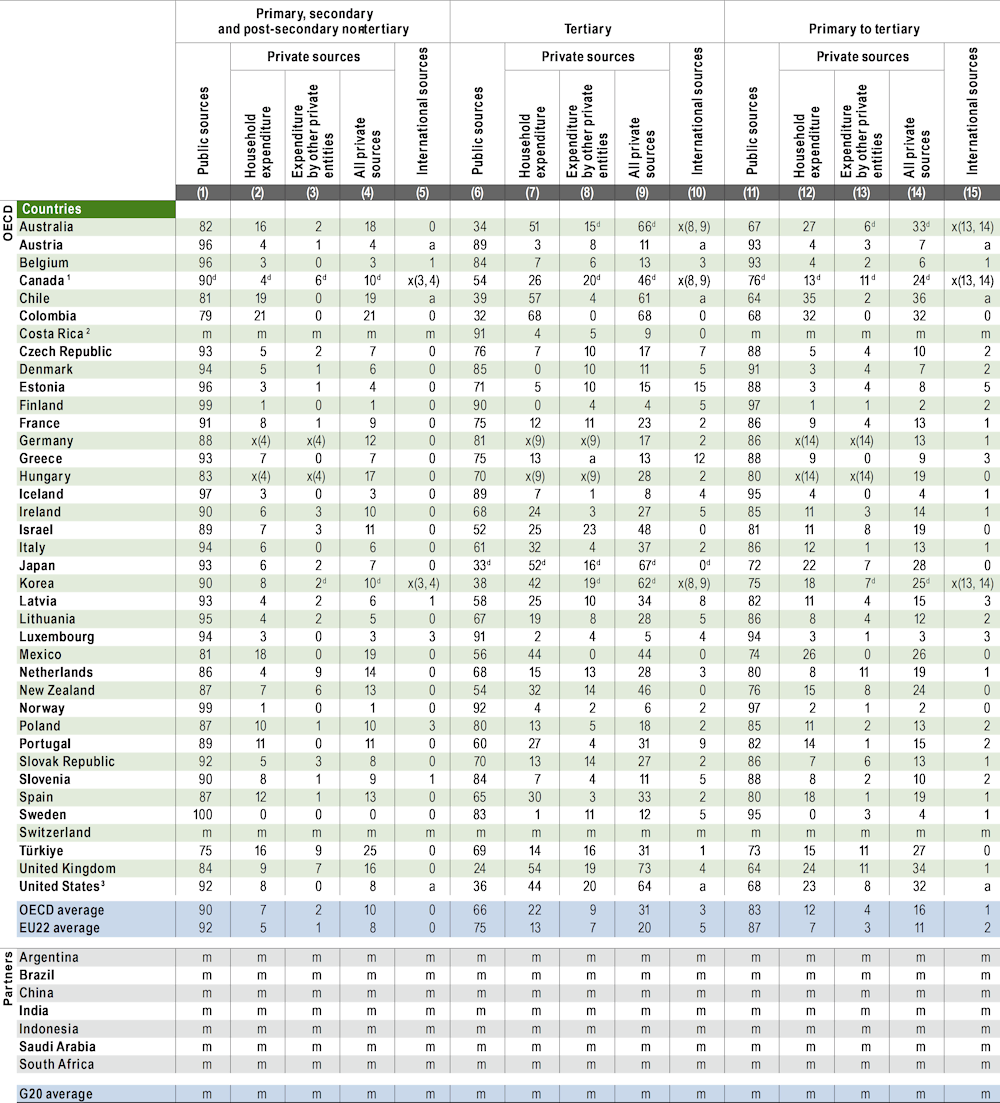

Table C3.1 |

Relative share of public, private and international expenditure on educational institutions, by final source of funds (2019) |

|

Table C3.2 |

Relative share of public, private and international expenditure on educational institutions, by source of funds and public-to-private transfers (2019) |

|

Table C3.3 |

Trends in the share of public, private and international expenditure on educational institutions (2011, 2015 and 2019) |

Cut-off date for the data: 17 June 2022. Any updates on data can be found on line at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-data-en. More breakdowns can also be found at http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

Table C3.1. Relative share of public, private and international expenditure on educational institutions, by final source of funds (2019)

After transfers between public and private sectors, by level of education

Note: Some levels of education are included with others. Refer to "x" code in Table C1.1 for details. Private expenditure figures include tuition fee loans and scholarships (subsidies attributable to payments to educational institutions received from public sources). Loan repayments from private individuals are not taken into account, and so the private contribution to education costs may be under-represented. Public expenditure figures presented here exclude undistributed programmes. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data and more breakdowns available at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Primary education includes pre-primary programmes.

2. Year of reference 2020.

3. Figures are for net student loans rather than gross, thereby underestimating public transfers.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

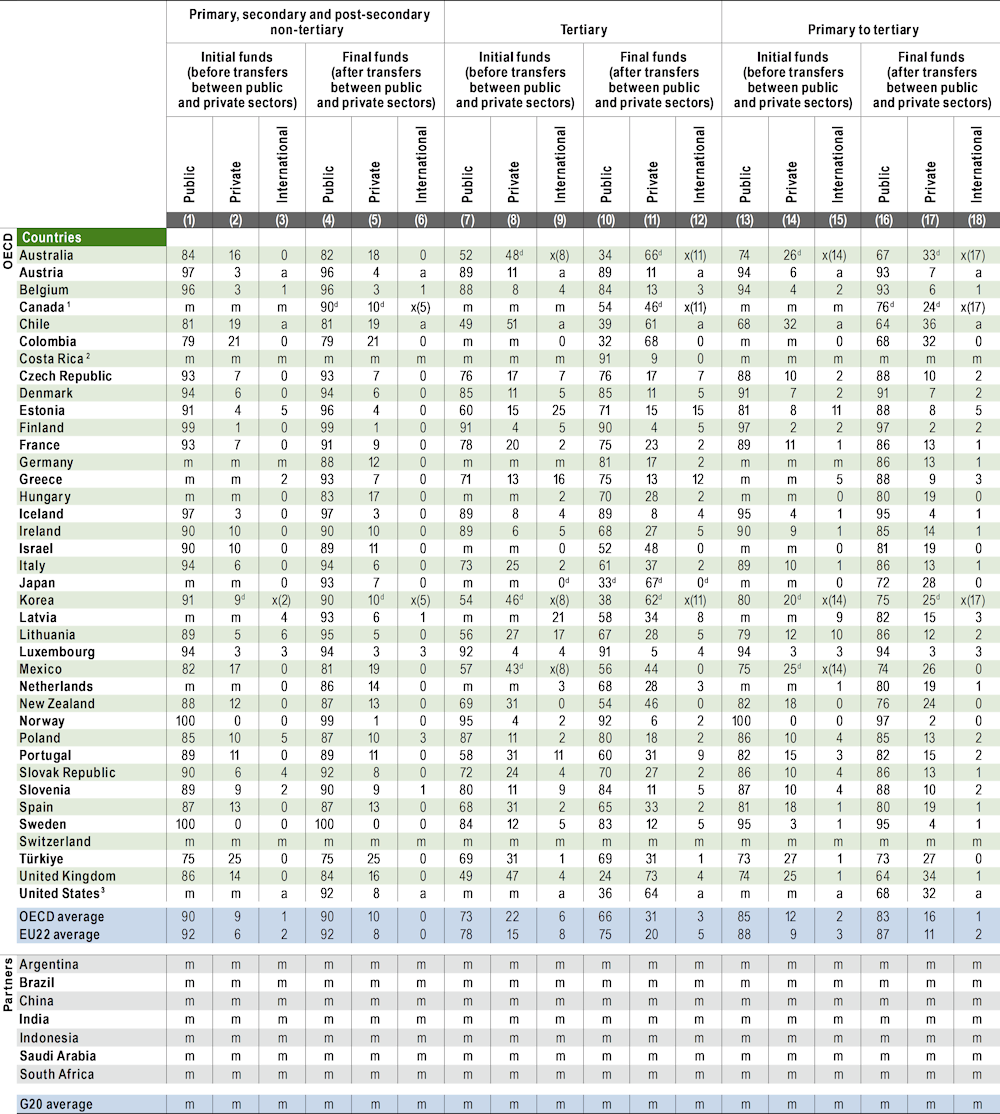

Table C3.2. Relative share of public, private and international expenditure on educational institutions, by source of funds and public-to-private transfers (2019)

By level of education and source of funding

Note: See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Public-to-private transfers at primary to post-secondary non-tertiary levels as well as at tertiary levels are available for consultation on line (see StatLink below). Data and more breakdowns available at http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Primary education includes pre-primary programmes.

2. Year of reference 2020.

3. Figures are for net student loans rather than gross, thereby underestimating public transfers.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table C3.3. Trends in the share of public, private and international expenditure on educational institutions (2011, 2015 and 2019)

Final source of funds

Note: Private expenditure figures include tuition fee loans and scholarships (subsidies attributable to payments to educational institutions received from public sources). Loan repayments from private individuals are not taken into account, and so the private contribution to education costs may be under-represented. Data on the share of public and international expenditure are available for consultation on line (see StatLink below). Public expenditure figures presented here exclude undistributed programmes. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data and more breakdowns available at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Private expenditure includes international expenditure.

2. Primary education includes pre-primary programmes.

3. Figures are for net student loans rather than gross, thereby underestimating public transfers.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.