This chapter describes the background under which this review was undertaken and the methodology employed. It sets out the economic, social, and demographic factors currently influencing education in Greece: an ageing and increasingly diverse population (including unprecedented numbers of refugees); the impact of the economic crisis; and the often political nature of education policymaking in the country. The overview of the education system of Greece that follows describes the current state of schools and tertiary institutions, teacher policy, governance, student performance, regional issues affecting the delivery of education, and the ongoing influence of shadow education.

Education for a Bright Future in Greece

Chapter 1. The Greek education system in context

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

1.1. Introduction and background to the report

1.1.1. Investing in education for a brighter future in Greece

Over the past decade, Greece has faced a sustained recession that has greatly affected its economy and society. Between 2009 and 2015, GDP fell annually by an average of nearly 4% – a fall of around 26% in real terms over the period (OECD, 2017[1]) (OECD, 2016[2]). National debt was 183% of GDP in 2016, second only to Japan among OECD countries, and well above the OECD average of 114%. The level of debt has caused very significant pressure on government spending, leading to severe cuts affecting most aspects of government activity, including education (OECD, 2016[2]).

This challenging context is affecting many dimensions of Greek lives and the education system. The decline in GDP has meant that material conditions for Greek households have also declined significantly: both disposable income and average earnings are now far below the OECD average. The long-term unemployment rate, currently at 19.5%, rose 15.6 percentage points between 2009 and 2014, the highest in the OECD, and the level of labour market insecurity is among the highest in the OECD. Youth unemployment and the proportion of young people neither employed nor in education or training (NEETS) have increased, with challenging labour market opportunities for young people (OECD, 2016[3]). Poverty levels have risen, especially for the unemployed and the self-employed.

This context has taken a toll on the education system. Over the past decade, public spending in education declined by 36% (in nominal terms), with cuts affecting teachers, especially wages and hiring (OECD, 2017[4]). A recruitment freeze of public civil servants has resulted in the hiring of new teachers through short-term contracts, a situation that is having a negative impact on the quality of schools and the education system as a whole.

At the same time, a refugee crisis during 2015-17 resulted in at least 12 000 school-age children joining the education system, adding challenges to a system already struggling with resource limits. While many refugees intended to transit to other European countries, a number of them have begun to leave their refugee camps for more permanent accommodation in Greece, and their children are being integrated into local schools.

In this challenging environment, average student performance in Greece has declined in science and reading, as measured in OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), to below OECD average levels. In this comparative assessment, in 2015, nearly one in three students in Greece did not reach the baseline level of performance in science, with similar proportions in mathematics and reading. At the same time, fewer than seven in ten 15-year-old students report high levels of life satisfaction and well-being, which is lower than the OECD average (OECD, 2016[5]; OECD, 2017[6]).

Other comparative indicators show more positive trends and demonstrate the capacity of the education system to perform:

The Greek education system stands around the OECD average in equity, measured as the impact of students’ socio-economic background on their educational performance, as measured by PISA (OECD, 2016[7]).

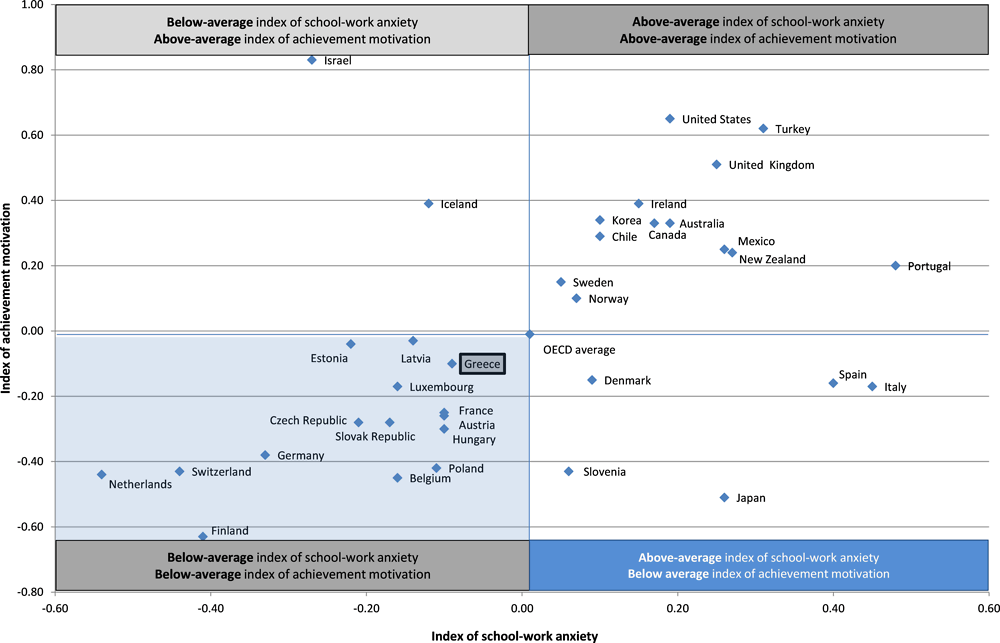

Greek 15-year-old students are motivated and have a strong sense of school belonging, higher than the OECD average (OECD, 2017[6]).

Greece has among the lowest dropout rates across European Union countries. At 6.2%, the early school leaving rate was below the EU-28 average of 10.7% in 2015 (Eurostat, 2017[8]).

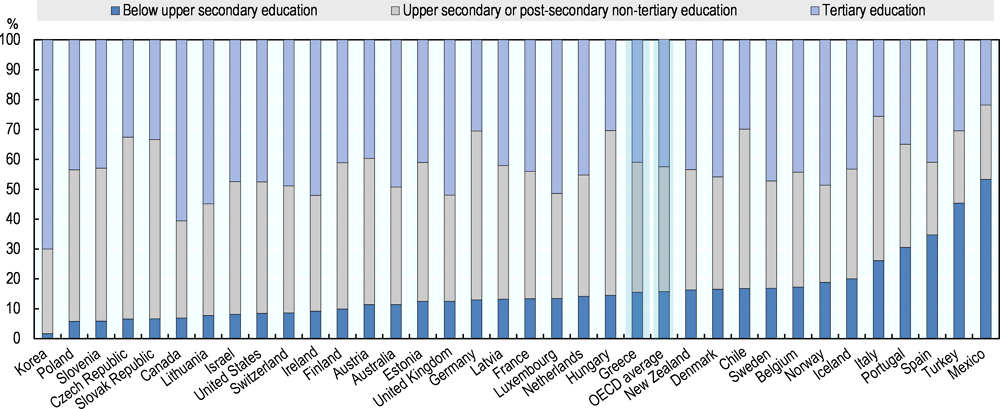

Greece has improved the educational attainment of 25-34 year-olds. This has been especially high in tertiary education, moving from 31% of 25-34 year-olds having completed tertiary education in 2010 to 41% in 2016, situated around the OECD and EU-22 average (OECD, 2017[4]).

In current conditions, it is important for the Greek education system to focus its efforts on strengthening the delivery of education in its schools and tertiary education institutions. High-quality education delivery can ensure that Greek students have the knowledge and skills needed to contribute to improve growth and social development and boost well-being in Greece in the future.

Greece has recognised the need for improvement and has engaged in a series of reforms to tackle key policy areas. A wave of reforms has been implemented since 2011. More recently, efforts have been renewed to address ongoing challenges, including the teaching workforce, school decentralisation, equity and tertiary education.

Many of these reforms thus focus on educational improvement, quality and equity, and the governance of schools and education institutions and resources. It is important to review the specific issues and challenges that underpin the need for reform so they can contribute to transition towards a 21st century education system that supports growth and well-being in Greece.

The Ministry has engaged in consultations with different stakeholders to develop recommendations for progress in education. A three-year education plan was adopted in 2017, with guidelines and proposals in a range of priority areas for 2017-19. These include targeted measures to improve teacher quality, school leadership and school self-evaluation, updates to the curriculum, all-day school provision, and actions targeted to the different levels of education (early childhood education, primary, secondary education, and tertiary education). The three-year plan also highlights the need for education policies to take into account the geographical specificities of Greece, including islands, isolated mountainous areas, and sparsely populated villages across the country.

Within this context, the OECD was invited to conduct an analysis of the education system and to deliver recommendations on selected policy areas that are part of its three-year plan, and also to cover education policy more broadly. The OECD review aims to provide a broad perspective on a series of issues that can contribute to raise the quality of education in Greece:

developing effective governance: decentralisation, autonomy and funding

achieving efficiency, equity and quality of the education system

targeting school improvement: teacher professionalism, evaluation and assessment

developing the conditions for quality, governance and funding in tertiary education.

In these areas, the OECD has been asked to draw upon lessons from research and best practice and to highlight policy options that can guide and enhance current Greek reform efforts to improve its education system and student performance.

This report presents an analysis and policy options from the OECD Education Policy Review of Greece, bringing an international perspective to this work. It explores the international evidence on the impact of different policy interventions which aim to support student achievement and well-being. It also describes how different countries have approached these issues – providing a range of “lessons learned” – and recommendations as to how their experiences might inform to Greece’s own path forward. Each chapter also suggests a long-term strategy for introducing changes.

More concretely, the report suggests that Greece is at a crossroads, following a hard crisis which has left the country in a challenging state. Education is a priority in Greece, and building on the progress already made, more efficient investments in schools, teacher and leaders and in universities with the aim of improving student outcomes for all, can contribute to encouraging a bright future for Greece.

To this end, it is important for Greece to develop the pre-conditions for these investments to be effective. These can be helped by:

developing an overall vision that is centred on students and the future of Greece

developing a long-term coherent educational strategy with sequential and strategic approaches that are politically feasible, and taking into consideration resources available and the implementation capacity of the system and the educational profession

considering broad public consultation or stakeholder engagement to ensure the sustainability of the vision and its implementation

improving the development and use of educational data, including on school and student outcomes, teacher well-being, educational funding, and the participation of private resources in education, such as in shadow education.

1.1.2. Background and methodology

In spring 2016, the OECD conducted a preliminary assessment of education policy development in Greece. This work resulted in the report Education Policy in Greece: A Preliminary Assessment (OECD, 2017[4]), presenting policy options for the development of more autonomy for educational institutions to achieve better student outcomes, strengthening teacher professionalism, and providing institutional support, with accountability and tools to support the education system as whole, including better data. It also made recommendations on ways to improve learning outcomes and to ease students’ transition into adult life and the labour market.

Building on this initial assessment, a second phase of the work was agreed between Greece, the European Commission Structural Reform Support Service (SRSS) and the OECD to undertake a full education policy review following the standard OECD country review methodology (Box 1.1), which includes background information provided by the country, quantitative and qualitative analysis developed by the OECD. These are complemented by review visits by an OECD review team to meet with a range of education stakeholders, discuss and understand the context (Annex A). The review is part of OECD’s overall efforts to support countries in their education reforms.

This document presents the findings and policy options identified during the review. It builds on desk-based analysis and other sources of information, a partial country background report provided by Greece, selected data from the European Union, EURIDYCE, the Centre for Educational Policy Development of the General Federation of Greek Workers (KANEP/GSEE), OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) data, among other sources. In addition, the OECD review team undertook three review visits: 29 May-1 June 2017, 25-29 September 2017 and 6 December 2017 (see Annex B for a description of meetings held throughout the review). During the review visits, the OECD team had the opportunity to exchange with a range of education stakeholders at various levels of the education system, including through visits to educational institutions and meetings with policy makers.

Box 1.1. The OECD education policy review process

OECD Reviews of National Policies for Education can cover a wide range of topics and subsectors tailored to the needs of the country. They are based on in-depth analysis of strengths and weaknesses, using various sources of available data, such as PISA, national statistics and research documents. The reviews draw on policy lessons from benchmarking countries and economies, with expert analysis of the key aspects of education policy and practice being investigated.

Reviews include one or more visits to the county by an OECD review team with specific expertise on the topic(s) being investigated (often with one or more international and/or local experts). An OECD Education Policy Review typically takes from eight months to a year, depending on its scope, and consists of six phases: 1) definition of the scope; 2) preparation of a background report by the country; 3) desk review and preliminary visit to the country; 4) main review visit by a team of experts; 5) drafting of the report; and 6) launch of the report.

The methodology aims to provide tailored analysis for effective policy design. It focuses on supporting specific reforms by tailoring comparative analysis and recommendations to the specific country context and by engaging and developing the capacity of key stakeholders throughout the process.

OECD Reviews of National Policies for Education are conducted in OECD member and non-member countries, usually upon request of the country. In addition, countries can now request support in the implementation of their education reforms.

For more information:

1.2. Contextual economic, social and demographic factors influencing education

1.2.1. An ageing and more diverse population

Greece (officially the Third Hellenic Republic) is located at the south-eastern end of continental Europe. The country is bordered by Turkey to the East, and Albania, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north. Greece has a unique geography, as it is bordered by sea (the Aegean Sea to the east, the Mediterranean Sea to the south and the Ionian Sea to the west), and encompasses as many as 1 500 islands, with around 227 of them populated. It also is one of the most mountainous countries in Europe (OECD, 2011[9]).

Of the total of 10.9 million Greek citizens in 2014 (Hellenic Statistical Authority, 2014[10]; Eurydice, 2016[11]) more than 76% of the population is living in urban or suburban areas (in 2011), an increase from 72.8% in 2001. This drift to the cities, long observed in Greece, now seems to have reached its peak (Eurydice, 2016[11]).

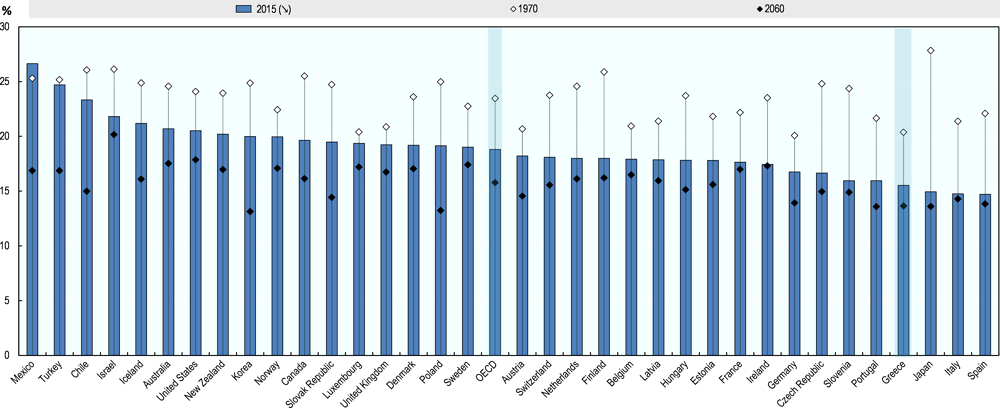

Over the last two decades, the population has been declining due to ageing and a low birth rate. Greece's fertility rate is 1.3 births per woman – the lowest of the OECD after Korea, below the OECD average of 1.7 and lower than the replacement level of 2.1 (Hellenic Statistical Authority, 2017[12]; OECD, 2017[13]). This has resulted in a decline in the proportion of young people, comprising 14.7% of the total population, among the lowest of OECD countries. Older cohorts of 65 years and over have increased to 20% of the population. There has been a slight compensation in the productive age population - driven by rising levels of immigration (Eurydice, 2016[11]).

Figure 1.1. Decline of the share of youth in total population in most countries

Source: OECD (2016[14]), Society at a Glance 2016: OECD Social Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264261488-en, Fig. 3.15.

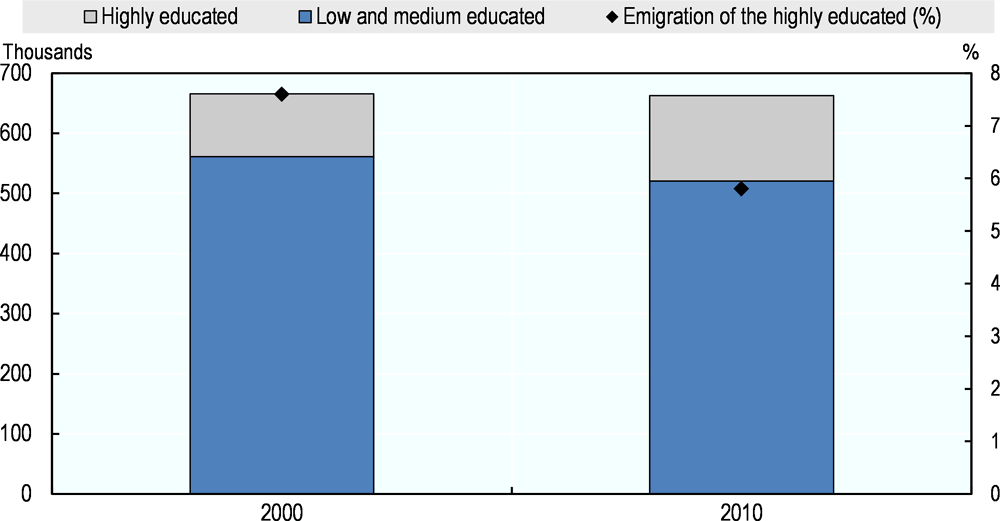

Greece's overall population shrinkage has also been affected by recent waves of emigration, driven by the economic crisis. Between 2008 and 2013 an estimated 427 000 Greeks, including nearly 223 000 young people (aged 25-39) left Greece permanently to seek work in other countries – mostly in Germany, the United Kingdom, and Australia. A further 106 000 were estimated to have left in 2014.

This trend is likely linked to a lack of economic or employment opportunities. A third of those aged 15-24 have indicated that they would move permanently abroad if they had the opportunity to do so (Lazaretou, 2016[15]; OECD, 2017[16]). The current emigrant population consists primarily of young professionals. Three quarters of emigrants were college graduates and one third of them were post-graduates or medical and engineering graduates (Pratsinakis, 2014[17]; OECD, 2017[16]; Labrianidis and Pratsinakis, 2016[18]; Theodoropoulos et al., 2014[19]).

Figure 1.2. A growing Greek emigrant population in OECD countries, 2010

Source: OECD (2015[20]), Connecting with Emigrants: A Global Profile of Diasporas, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264239845-en.

At the same time, Greece has faced increasing immigration. While around 6.2% of the Greek population in 2013 had been born abroad, putting Greece among OECD countries with the smallest foreign-born population, there has been a massive increase in refugees. In 2015 Greece received nearly one million refugees. While many intended to move on to other European countries, around 50 000 applications for asylum (mostly from Syria, Iraq and Pakistan) were made, many with the intention of staying in Greece. Compared with an annual average of just under 9 000 applications for asylum in 2012-14, this represents a 338% increase (OECD, 2017[16]). As of September 2017, nearly 50 000 refugees were in Greece, most of them residing in Refugee Accommodation Sites. Of these, more than 40% were children (UNHCR, 2017[21]).

1.2.2. The impact of the economic crisis

Greece has suffered an economic crisis which has had a marked impact on the education system. Following a deep and prolonged depression, during which real GDP fell by 26% between 2009 and 2016, the economy is projected to start growing again (Gourinchas, Philippou and Vayanos, 2016[22]; OECD, 2016[23]).

Since 2009, material conditions for people in Greece have declined significantly: average household net adjusted disposable income per capita fell by 31.6% and average earnings dropped by 15.6% in 2013. Both now lie far below the OECD average. While the poverty rate has risen to one-third of the population, not all groups have been equally affected: the impact was greater for men than women, for children and young adults (aged 30-44), students and the unemployed. Employment rates have fallen for those with only upper secondary education (European Commission, 2015[24]). While relative poverty also declines sharply with the level of educational attainment, no group, including university graduates, was spared (OECD, 2013[25]).

Wide differences in educational deprivation between children from high and low socio-economic backgrounds have emerged: in 2012, 9.8 per thousand from a low socio-economic background were likely to lack such at-home basics as a desk, a quiet place to study, books for school and a computer for school work, while just 0.9 per thousand from a high socio-economic status were similarly deprived (OECD, 2016[26])

Labour market insecurity in Greece is among the highest in the OECD. The unemployment rate stood at 22.4% in the first quarter of 2017, the highest in the OECD and well in excess of the EU-28 average of 7.9% (OECD, 2017[27]) with youth unemployment standing at 46.6% in March 2017. Tertiary-educated young adults endure the highest rate of unemployment of all OECD countries, at 28% compared to an average of 6.6% and 7.4% across OECD and EU-22 countries (OECD, 2017[28]).

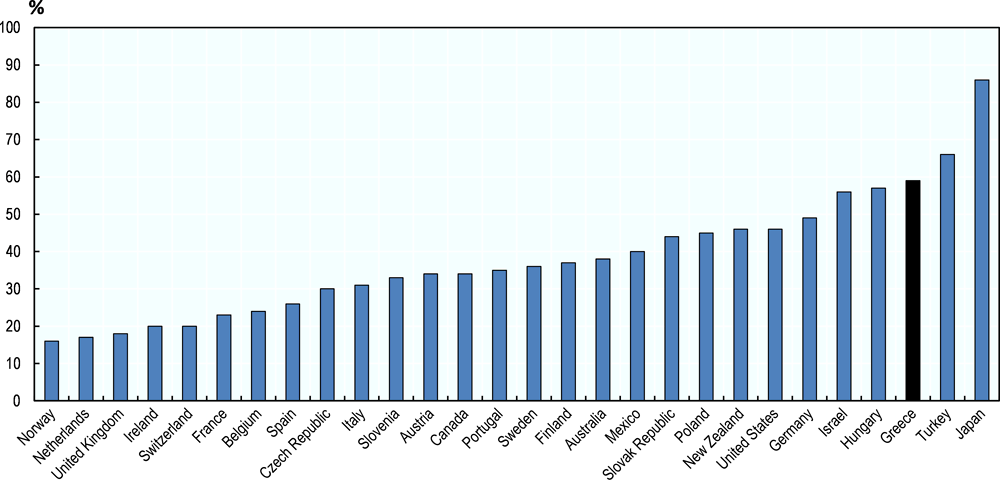

Despite this, a recent survey shows that many Greek firms report that they find it difficult to find candidates with the right skills to fill their current vacancies (Figure 1.3). Firms report that one of the top reasons why they find it hard to fill jobs is the lack of available applicants with the technical competencies required (Manpower Group, 2016[29]).

Figure 1.3. Firms facing skills shortages, 2016

Note: Survey based. Firms are classified as facing a skills shortage if they report having difficulties filling jobs.

Source: Manpower Group, Talent Shortage Survey, various years, cited in OECD (2017[30]), OECD Economic Surveys: New Zealand 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-nzl-2017-en.

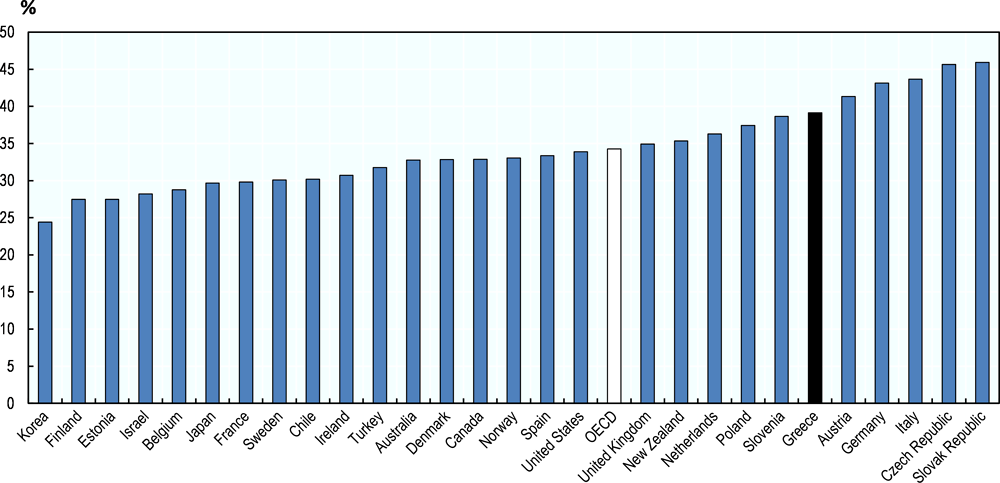

New production technologies will play increasingly important roles in determining the availability and nature of work (OECD, 2017[31]). Benedikt Frey and Osborne (2013[32]) have estimated the risk for some occupations in the United States to be automated out of existence in the coming decades. In terms of tasks that could be automated with likely advances in artificial intelligence, one estimate is that nearly 40% of current Greek employment is in occupations at significant (30-70% risk) or high (more than 70%) risk of automation. This is far higher than the OECD average of 34% (Figure 1.4) and represents a long-term challenge for the country. And while such predictions are always prone to fluctuation or change based on disruptive events, other studies confirm the looming risk for Greece, even if there are ongoing disagreements on its likely scale (Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn, 2016[33]; OECD, 2017[31]).

Figure 1.4. Risk of job automation, 2015

Note: Jobs are at high risk (significant risk) of being automated if at least 70% (50-69%) of their tasks are automatable. Data correspond to 2012 for countries participating in the first round of the Survey of Adult Skills: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden, United States and United Kingdom. Data correspond to 2015 for countries participating in the second round of the Survey of Adult Skills: Chile, Greece, Israel, New Zealand, Slovenia and Turkey.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2017[34]), OECD Survey of Adult Skills (2012, 2015), OECD Survey of Adult Skills (database), http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/ (accessed on 13 September 2017); M. Arntz et al. (2016[35]), "The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis", OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 189, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlz9h56dvq7-en.

1.2.3. The political context

The current Greek political landscape has been influenced by the economic crisis, the rise in public debt and decline in public expenditure, as well as the need to respond quickly to the memoranda signed between Greece and the European Commission, and their implementation as monitored by the Commission, and the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund as major providers of financial assistance.

The political sphere has a strong influence on education and many other areas of public service. Greece has a long tradition of highly centralised government with a strong commitment to social equity and an egalitarian society, values which are enshrined in the Constitution of Greece (Article 4). The Greek system, through its legislation, seeks to develop the conditions to avoid privilege and differentiation. This is the case in education, where there are efforts to prevent selection among students, teachers, schools or regions on any basis other than “objective criteria” defined at a national level.

The government also plays an important role in the labour market, with almost 20% of total employment in the public sector. While public employees may have higher benefits and employment security than those in the private sector, the proportion of total employment in this sector has been declining recently (OECD, 2017[4]). This is also the case for teachers and other education employees.

It is important to recognise the impact of the public sector on equity, as highlighted in the OECD Economic Survey for Greece (OECD, 2013[25]). During the pre-crisis period, public employment played a social role, though at the expense of efficiency (OECD, 2009[36]). For a very long period, hiring in the public sector has been driven by a clientelist political culture. The fact that the public sector pay structure often favoured employees from more disadvantaged groups may have induced higher participation among these groups, reducing social exclusion (OECD, 2011[37]).

At the same time, there are other contextual governance issues that shape educational provision. There are concerns of a long-standing culture of clientelism and mistrust of governmental initiatives more generally. Within the education system, educators are wary of any kind of external or internal evaluation of school or teacher performance, lest the results be misused. At the same time, there are concerns about corruption, the misuse of public funds, or public employment for private purposes. This culture of clientelism has long been recognised in Greece and has proved difficult to change, with recent efforts through legislation, according to Greek authorities. This culture may be most visible in the analysis of corruption. A recent Eurobarometer survey asked European Union population about the existence of corruption in their countries, and more than half (52%) of Greeks who responded expressed that it was “very widespread”, and 44% “fairly widespread” (European Union, 2017[38]).

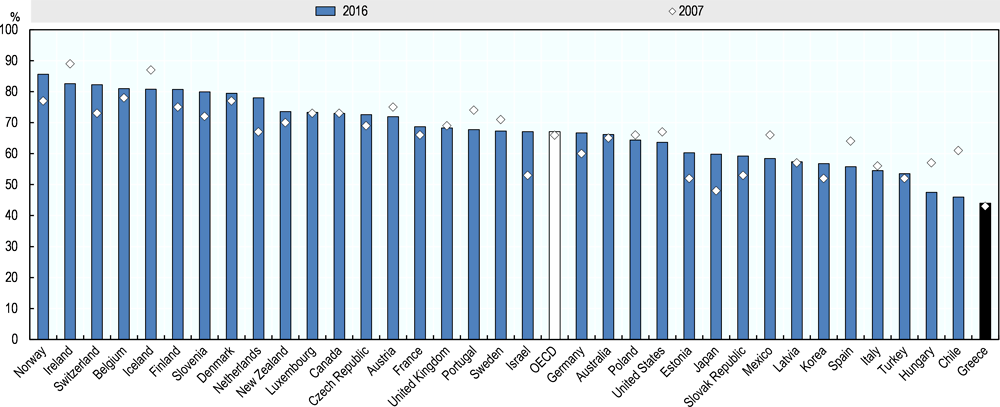

While in education the extent of corruption is perceived to be low in terms of individuals and educational institutions, according to both Eurobarometer and national surveys (the most recent of which found that 68% of respondents said they “trusted” public universities and schools (Dawn, 2016[39])) the culture of clientelism can be an issue when developing policy. Nevertheless, overall satisfaction with schools and the education system, already the lowest in the OECD in 2007, at 43%, against an OECD average of 66% remained among the lowest at 44% in 2016, as shown in Figure 1.5 (OECD, 2016[26]; OECD, 2017[16]).

Figure 1.5. Citizen satisfaction with the education system and schools is low, 2016

Note: Data refer to the percentage of "yes" answers to the question: "In the city or area where you live, are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the educational system or the schools?" Data for China are for 2013 rather than 2016.

Sources: Gallup World Poll (database), in OECD (2017[40]), Government at a Glance, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2017-en.

Other factors also affect the efficient and sustainable delivery of public services. A recent OECD Public Governance Review of Greece identified a variety of issues in public sector human resources management in terms of ensuring that employees with the right talent and skills are being utilised effectively. The economic and political climate in Greece has highlighted these challenges, which if not addressed, could have an adverse impact on the future quality of education. In particular, the selection, training and promotion procedures of civil servants, including those working in education, have not been updated as necessary to deliver the reforms required for education improvement. The OECD report suggests that the lack of clarity in the human resource strategy and the governments’ difficulties in implementing reforms and in modernising systems “limits the ability of management to increase efficiency in service delivery, promote organisational innovation and forward plan” (OECD, 2011[41]).

Recent developments have also had an impact on the public sector more generally. Since the onset of the European sovereign debt crisis, Greece has embarked upon a range of reforms which have affected public sector employment. Since 2011, retiring staff have been replaced at a rate of 20% (OECD, 2011[41]), while retirements for many have been delayed. Devolution of authority and general restructuring have also had an impact on employment.

1.3. Education in Greece: Overview, governance, outcomes

1.3.1. An overview of the Greek education system

Education in Greece is enshrined in Article 16, Section 4 of the Greek Constitution, which sets out that:

Education constitutes a basic mission for the State and shall aim at the moral, intellectual, professional and physical training of Greeks, the development of national and religious consciousness and at their formation as free and responsible citizens.

The same article also guarantees that "Art and science, research and teaching shall be free and their development and promotion shall be an obligation of the State" (Hellenic Republic, 2008[42]).

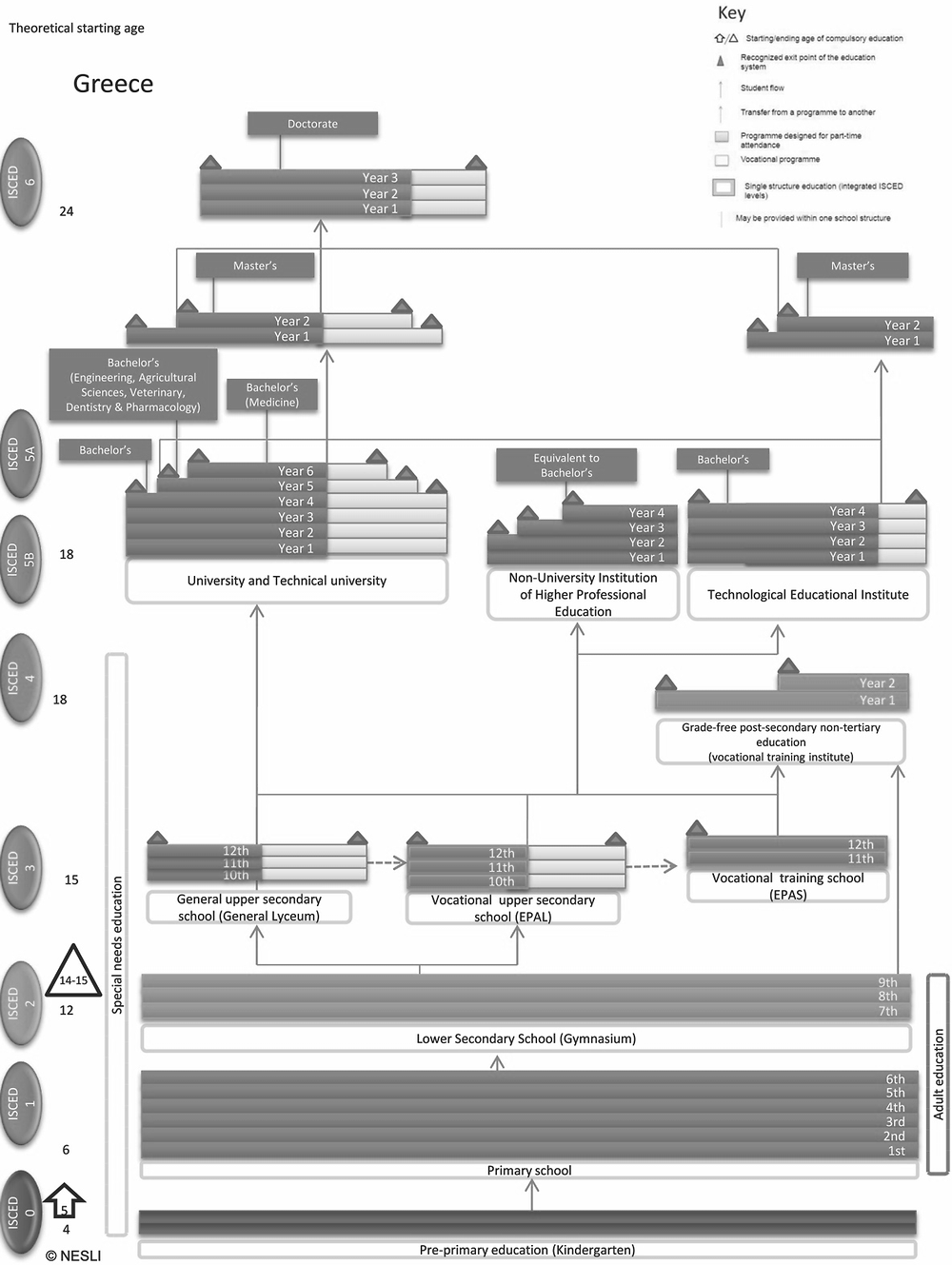

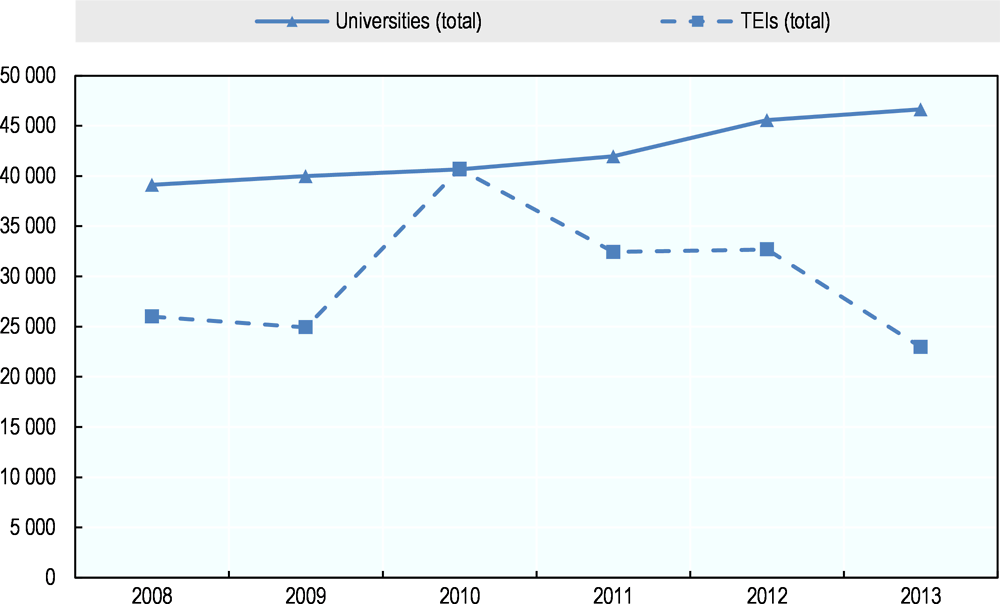

The Greek education system is under the central responsibility and supervision of the Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs (MofERRA). Early childhood education usually starts at age 4 (although with low enrolment rates) and pre-primary, primary and lower secondary education is, since March 2018, now compulsory between the ages of 4 and 14/15. Primary education (Demotiko) lasts six years, and lower secondary education (Gymnasium) lasts three years. Student tracking starts at the end of lower secondary education, when 15-year-old students choose between vocational or academic tracks. Upper secondary education – unified upper secondary school (Lyceum) and vocational upper secondary school (Epaggelmatiko Lyckeio, EPAL) – lasts three years. Enrolment in vocational programmes is relatively low: in 2015, 14% of 15-19 year-olds were enrolled in such programmes, and only 2% in apprenticeships. Increasing enrolment in vocational programmes of all types is a major policy priority for the current government (OECD, 2017[28]; European Commission, 2015[24]). Students who want to go into tertiary education take the Panhellenic examination which gives access into higher education institutions (HEIs), which include 22 universities as well as 14 Technological Education Institutes (TEIs) across Greece. Universities deliver a general academic education, while TEIs have a mission to conduct higher education at bachelor and postgraduate level in science, technology and arts, but with an applied and vocational focus (European University Association, 2014[43]).

In 2015 there were around 13 000 pre-primary to secondary schools in Greece, with around 1 368 000 students and about 135 000 teachers in public education (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Number of schools, students and permanent teachers in Greece, 2015

|

School types |

Number of schools |

Number of students |

Number of permanent teachers |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Kindergarten (all kinds) [Nipiagogeio] |

5 224 |

137 585 |

12 432 |

|

Primary school (all kinds) [Dimotiko Scholeio] |

4 566 |

604 497 |

59 310 |

|

Secondary school (all kinds and levels) |

3 437 |

617 280 |

69 181 |

|

Lower secondary school (all kinds) [Gymnasio] |

1 747 |

296 865 |

32 207 |

|

Upper secondary vocational school [Epaggelmatiko Lykeio - EPAL] |

399 |

86 038 |

11 634 |

|

Upper secondary general school [Geniko Lykeio - GEL] |

1 059 |

230 239 |

20 266 |

|

Other |

232 |

3 004 |

803 |

Source: Institute of Educational Policy (2016[44]), “Experts’ Reports”, Report prepared by the Institute of Educational Policy and academic experts for the OECD review team, March 2016.

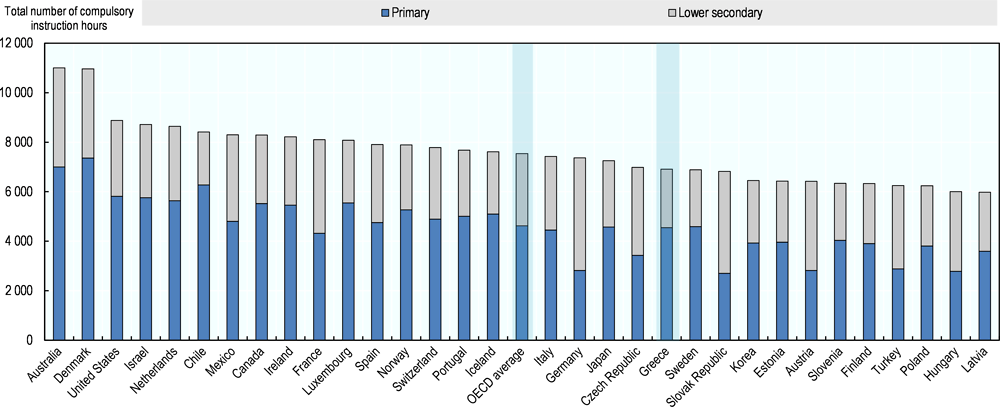

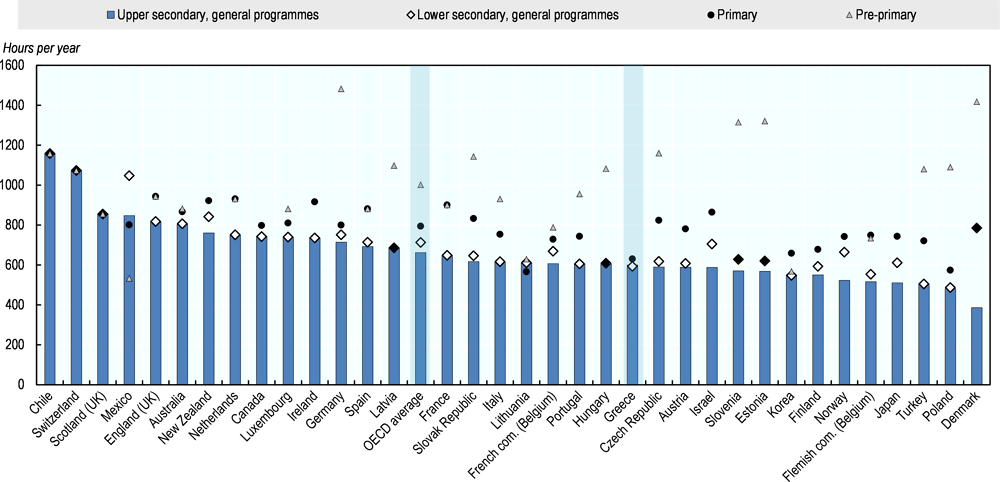

In these schools, students in Greece are currently expected to receive a total of around 7 000 hours of instruction during their mandatory primary and lower secondary education. This is slightly less than the OECD average of 7 540 hours (Figure 1.6). Recent efforts have been to lengthen the school day, moving towards provision of all-day schools (see Chapter 3). According to the MofERRA sources, primary and lower secondary non-compulsory curriculum hours have increased and since 2016/17, attendance of students in lower secondary education has increased by three additional weeks in comparison to 2015/16.

Figure 1.6. Mandatory instruction time in general education, 2017

Source: OECD (2017[29]), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en

Figure 1.7. An overview of pathways through the Greek education system by level, 2016

Source: OECD (2016[47]), “Diagram of the education system: Greece”, OECD Education GPS, http://gpseducation.oecd.org/CountryProfile?primaryCountry=GRC.

1.3.2. Education governance and funding

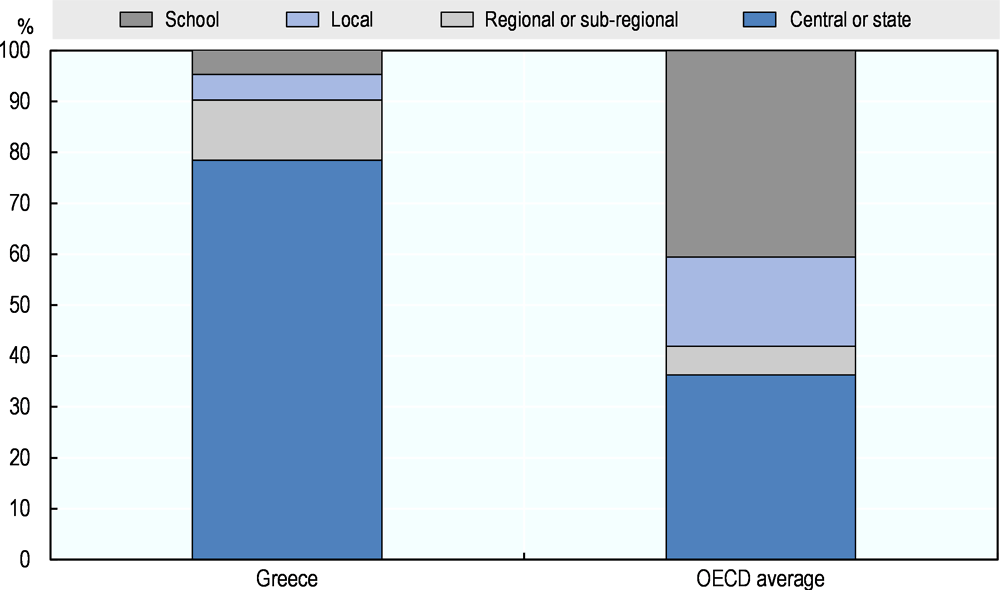

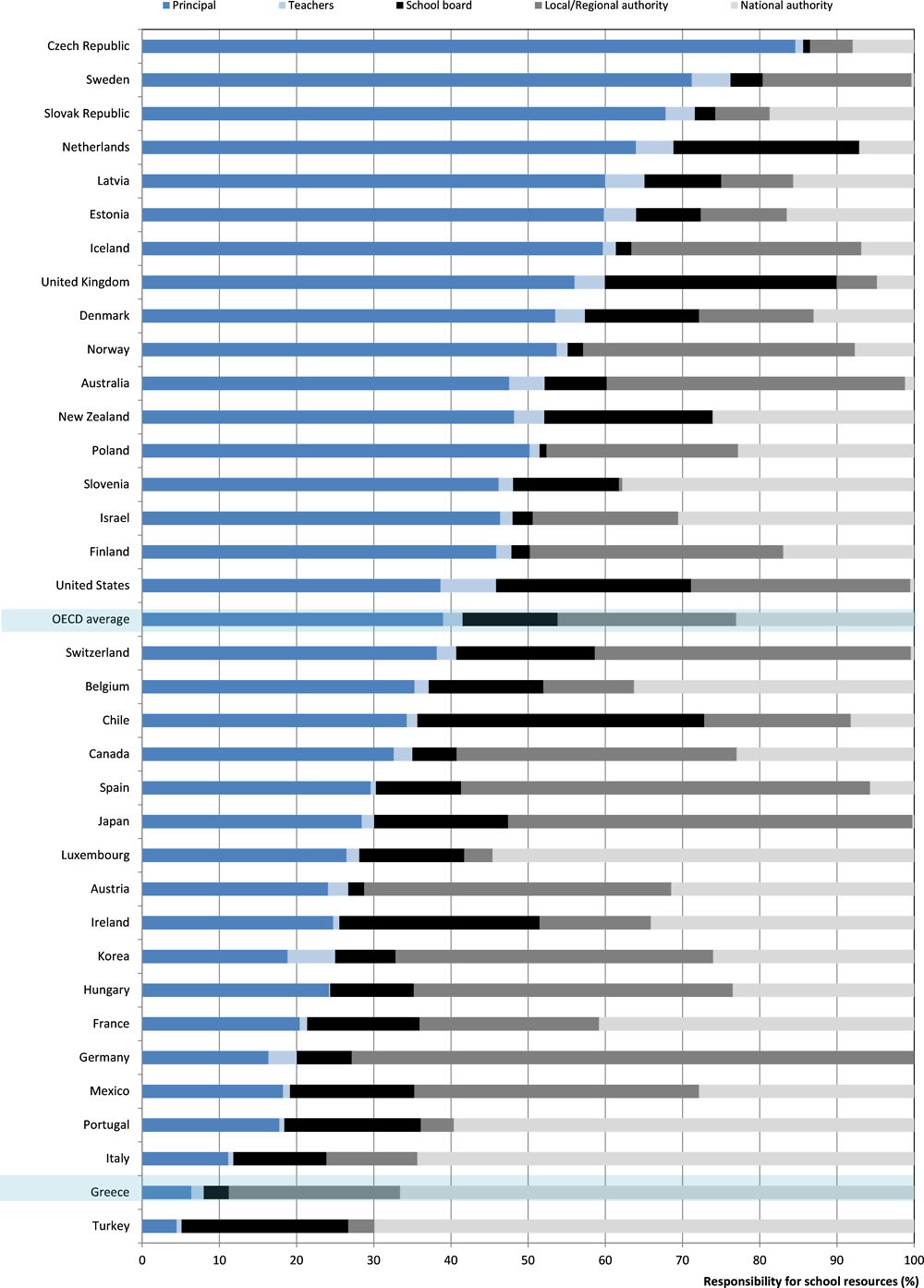

The education system in Greece is highly centralised: the main responsibilities in all education sectors are with the national Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs. A 1982 OECD review described the system as "highly centralised", and governed by "Parliamentary laws and executive acts", managed "by a powerful centralised bureaucracy" (OECD, 1982[48]). The system remains centralised, with low levels of responsibility at the regional and local level, as shown in Figure 1.8. According to PISA data, autonomy over curriculum and assessment in Greek schools is below the OECD average. There is also a below-average level of autonomy for allocation of resources such as hiring and dismissal of teachers.

Figure 1.8. Education decisions in lower secondary education, 2011

Source: OECD (2012[49]), Education at a Glance 2012: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2012-en.

Public spending on education in Greece has been deeply affected by the economic crisis. While the total public spending on education increased by more than 80% between 2000 and 2008, it has decreased sharply since then (OECD, 2017[50]). The latest available figures for 2014 general government expenditure in education was 4.4% of GDP, lower than either the EU-28 average (4.9%) or the OECD average (5.2%) (European Commission, 2016[51]; OECD, 2017[52]). The 2017 Parliament State Budget Discussion estimates that 2.9% of GDP will be spent on education in 2017 (Roussakis, 2017[53]). Recent data reported from the Greek Statistical Authority suggests public education expenditure of 4.1% of GDP and private expenditure to be at 1.6% of GDP in 2016. Basic public expenditure data in education and administrative data on numbers of students and teachers are often unreliable and internally inconsistent. The OECD review team found limited coherence across the different levels of the system and a lack of consistency between the data gathered by the Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs (MofERRA) and the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT). In comparing what was budgeted in 2013 and actual expenditure, the KANEP/GSEE found a 1.3% of GDP (EUR 2.37 million) discrepancy (Centre for Education Policy Development, 2016[54]).

In spite of the impact the economic crisis has had on household income, many families spend significant amounts on frontistirio fees (i.e. after-school tutoring, also referred to as “shadow education”) to support their children’s education but mostly to improve their chances of securing a place at a highly-ranked university. Participation in after-school tutoring of 15-year-olds is the highest among OECD countries (OECD, 2013[55]). Discussion of the impact of household expenditure on shadow education follows in Chapter 2 and 3.

Public schools receive funding from the state budget via several ministries and for some expenditures, through intermediary authorities. The MofERRA provides funds through block grants to the Directorates for Education (for school unit staff costs, as these bodies allocate teaching and non-teaching staff to schools), as well as to the state-run infrastructure agencies K.Y.S.A. (for equipment), and DIOFANTOS (for the provision of text books). Following the administrative reform of education, through the “Kallikrates” programme, pedagogical guidance of education has been transferred to these regional Directorates of Education. Each Directorate formulates, among other responsibilities, scientific and pedagogical guidance for education in the region. The Directorates supervise the implementation of national education policy, while tailoring policy to match the specific regional requirements and connecting regional educational services with the central education (Institute of Educational Policy, 2016[44]). In addition, the MoFERRA and the Ministry of Interior both provide funds to municipal level school committees for maintenance of school buildings. The Ministry of Interior provides additional funds to school boards for operational goods and services. The Ministry of Infrastructure, Transport and Networks provides capital funding to schools through the K.Y.S.A., which is only to be used for repairs, maintenance, and land and building acquisitions. Municipalities estimate school unit needs based on the number of students and staff and other input-based criteria (such as working in inaccessible, remote or problematic areas, as well as distances between schools).

Public tertiary education institutions (TEIs) are centrally financed by the state budget and the Public Investments Programme on Higher Education. The budget for TEIs is based on a four-year development plan. TEIs are entitled to generate income, but by constitutional law, they cannot charge tuition fees to first-cycle full-time students. In the second-cycle, students may pay fees. Student support mechanisms are available in the form of scholarships, merit-based grants, loans and family allowances. Around 1% of students enrolled in tertiary education receive a scholarship for undergraduate studies. A discussion of the small private tertiary education sector is provided in Chapter 5.

1.3.3. Student performance: From completion towards higher equity with quality

It is worth recalling how far Greece has progressed: the 50-year-olds of today were born in and started school at the end of the 1960s, when altogether one third of the Greek population had no schooling, when only six years of primary education was mandatory, and when any major changes to the system established in 1927 were still a decade away (Garrouste, 2010[56]). Completion rates overall have risen, with an increase in the proportion of adults who have completed upper secondary (from 32% to 44%) and higher education (from 20% of those aged 55-64 to 40% for those aged 25-34) (OECD, 2016[57]).

Figure 1.9. Educational attainment of 25-34 year-olds, 2016

Source: OECD (2017[28]), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en.

The participation rate in early childhood education and care (ECEC) is low in relation to the OECD average, but has been increasing. Participation of two-year-old children in 2014 was 29%, five percentage points below the OECD average, and 44% for those aged three, when the OECD average was 71% (OECD, 2017[4]) the participation of four-year-olds up until to compulsory school age was 79.6% in 2015, in comparison to an EU average of 94.8% (Eurostat, 2018[58]). PISA analyses reveal that students who had attended pre-primary education for more than one year outperformed the rest, in many countries by more than one school year, even when taking account of the student's socio-economic background (OECD, 2013[59]). In Greece, students who were low performers in mathematics at age 15 were far more likely to have not attended pre-primary school.

Participation increases with age, and while the number of people with at least upper secondary education in Greece is roughly equivalent to the OECD average, the number of those with tertiary education, at around 39%, is slightly over EU-28 average but lower than the OECD average (OECD, 2015[60]).

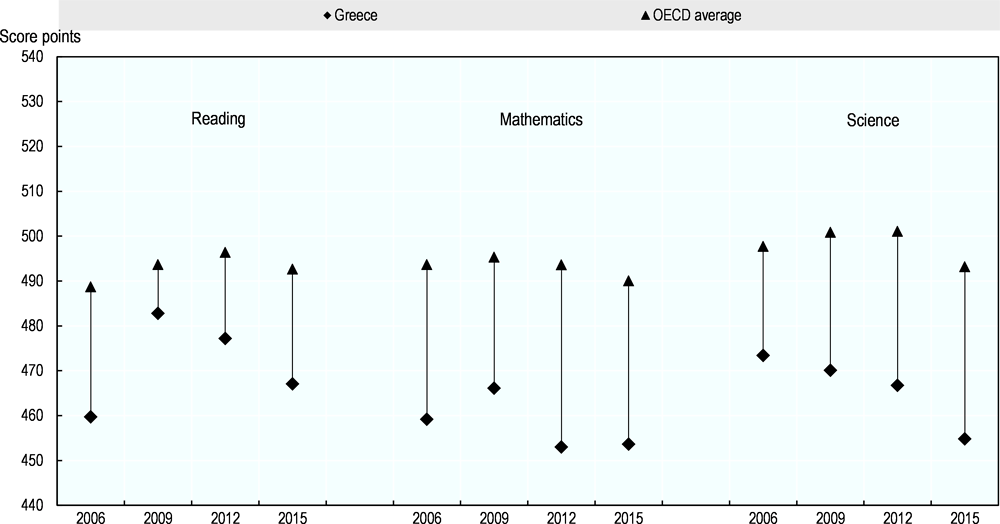

In terms of skills and competencies, the Greek results in the OECD Programme for International Students Assessment (PISA, which measures the performance of 15-year-old students in reading, mathematics and science), while close to the OECD average and have not improved over recent cycles. More concretely:

In science literacy, mathematics and reading performance, Greek students scored below the OECD average in 2015, and the average performance of 15-year-old students was one of the lowest among OECD countries (454 in mathematics in comparison to an OECD average of 493).

In 2015, more than one-third of Greek 15-year-olds participating in PISA were low achievers (scoring below Level 2) in mathematics (36% compared to an OECD average of 23%), and only 4% scored at the highest levels – Level 5 and 6 (compared to an OECD average of 11%).

In addition, progress has varied across the different domains. While results in mathematics have been stable since 2006, results in science and reading have declined sharply between the 2009 and 2015 rounds, dropping by 19 PISA score points in science (OECD, 2016[61]) and by 16 PISA score points in reading (OECD, 2016[61]).

The review team was informed that in Greece the PISA assessment of competencies is not considered to be well-aligned with the Greek curriculum, which has a strong content focus (Breakspear, 2012[64]). Nevertheless, besides student completion information, there are no other national data available by which to analyse student performance at a national level. PISA data provide an international overview of student performance in relation to other OECD and European Union countries and the trends indicate that student performance is either static or has declined since 2009 (Figure 1.10).

Figure 1.10. Trends in PISA performance in Greece, 2000-15

Sources: OECD (2014[62]), PISA 2012 Results: What Students Know and Can Do (Volume I, Revised edition, February 2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264208780-en, Annex B4: Trends in mathematics, reading and science performance, OECD countries and OECD (2016[63]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264266490-en, Table I.4.4a.

Both student achievement and motivation, as reported by students, are lower than the OECD average. Figure 1.11 shows Greece located below average in both schoolwork-related anxiety, and in achievement and motivation.

Figure 1.11. Students' achievement motivation and schoolwork-related anxiety, 2015

Source: OECD (2017[6]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students' Well-Being, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888933470611.

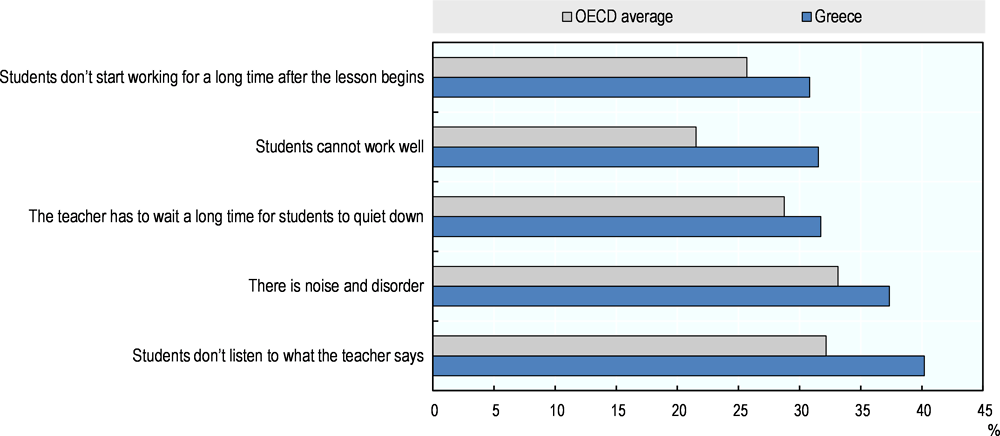

At the same time, PISA data reveal low levels of classroom discipline, with students waiting a long time to start work in lessons, not working well and not listening to their teachers, as shown in Figure 1.12 (OECD, 2016[65]). Another indicator often used for school environment is school attendance. In Greece, 42% of 15-year-old students reported that they had skipped at least one class in the two weeks before the PISA test and 23% had skipped at least one entire day (OECD, 2013[66]). Across OECD countries, these levels stood at 18% of students reporting they had skipped at least one class and 15% reporting that they had skipped at least an entire day of school without authorisation in the two weeks before the 2012 PISA test.

Figure 1.12. Disciplinary climate in Greek secondary schools is low, 2015

Source: OECD (2016[65]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en.

Equity in the Greek education system

Greece has a relatively inclusive school system. The school system is comprehensive and so does not separate students into different academic tracks. This is a positive approach, as early student selection has a negative impact on students assigned to lower tracks, without raising the performance of the whole student population (OECD, 2012[67]). All students follow a similar curriculum until age 16. PISA results show that on average the impact of a student’s socio-economic background on performance is around the OECD average (Figure 1.13).

Figure 1.13. Science performance and equity, 2015

Notes: B-S-J-G (China) refers to the four PISA-participating China provinces: Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Guangdong. FYROM refers to the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Argentina: Only data for the adjudicated region of Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires (CABA) are reported.

Source: OECD (2016[61]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264266490-en.

Across most countries, socio-economically disadvantaged students not only score lower, they also have lower levels of engagement, drive, motivation and self-belief. Greece, achieves lower than average levels of performance with average equity in education outcomes as assessed in PISA 2015.

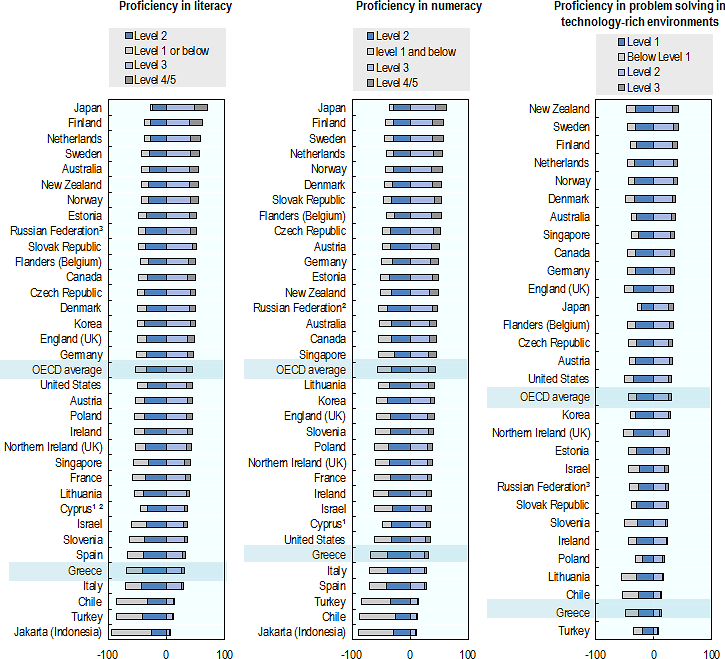

When analysing the skills and competencies of adults, data from the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) reveal that tertiary-educated adults in Greece have relatively low proficiency in literacy, numeracy and problem solving in technology-rich environments.

It would appear that the expansion of educational attainment in Greece has not translated into improved skills. In Greece 50% of 55-65 year-olds did not complete upper secondary education, but only 15% of 25-34 year-olds do not have this level of educational attainment; 19.9% of 55-65 year-olds have a tertiary qualification, compared to 27.3% of 25-34 year-olds (OECD, 2016[3]). However, despite the increase in secondary and tertiary attainment for young people, 25-34 year-olds score only 6 points higher in literacy than 55-65 year-olds, while the OECD average difference for these age groups is 29 points.

Overall, in the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), Greek adults showed low levels of proficiency in literacy and numeracy in comparison to other countries participating in the survey. They also had a higher share of adults scoring at Level 11 or below in both proficiency domains, which are levels considered (Figure 1.14).

Figure 1.14. Proficiency of adults, 2012

Notes: Note by Turkey: The information in this document with reference to “Cyprus” relates to the southern part of the Island. There is no single authority representing both Turkish and Greek Cypriot people on the Island. Turkey recognises the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). Until a lasting and equitable solution is found within the context of the United Nations, Turkey shall preserve its position concerning the “Cyprus issue”.

Note by all the European Union Member States of the OECD and the European Union: The Republic of Cyprus is recognised by all members of the United Nations with the exception of Turkey. The information in this document relates to the area under the effective control of the Government of the Republic of Cyprus.

Source: OECD (2016[68]), Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264258051-en.

Almost 2 million adults (27% of all) between the ages of 16 and 65 have low literacy skills, and 2 030 000 individuals have low numeracy skills (29%) (below Level 2 in the Survey)2. These are people who struggle with basic quantitative reasoning or have difficulty with simple written information, and for them, entering and progressing in working life and engaging in civic life is becoming more and more difficult. One third of people aged 55-65 have weak foundation skills (in both literacy and numeracy). In contrast to what is observed in other countries, 25-34 year-old adults in Greece have similar literacy levels as 55-65 year-olds. Figure 1.14 shows that about 5% of adults aged 16-65 in Greece perform at the highest levels (Level 4/5) on literacy compared to the average of 11% of adults in all participating OECD countries.

Problem solving in technology-rich environments is also measured in the OECD Survey of Adult Skills. Proficiency reflects the capacity to use ICT devices and applications to solve the types of problems adults commonly face as ICT users. PIAAC results show that Greek adults are at low levels in proficiency in this area. Only 17% of adults perform at the highest levels of problem solving, which is significantly lower than the average countries participating in PIAAC (31%) (OECD, 2013[69]).

The regional dimension of education

While equity in education appears to be close to the OECD average, there is also selected evidence pointing to regional disparities in educational attainment (such as early school leaving rates). These data indicate that regional disparities in terms of educational attainment are the fifth largest among OECD countries [ (OECD, 2017[70]); KANEP/GSEE, 2008, 2009 and 2011 cited in (Ballas et al., 2012[71])]. The data on regional school and student performance while, limited, suggest a correlation between the state of educational provision and educational outcomes in individual prefectures and the socio-economic conditions of the area (Ballas et al., 2012[71]).

In fact, the geography of Greece – with its islands and mountainous regions – strongly influences the provision of education (see Table 1.2). In primary education, while 30% of the nursery and primary schools are located in the large urban centres (Athens-Attiki and Thessaloniki-Central Macedonia), almost every small town and village has its own school: 18% of nursery and primary schools are located on islands; 3.5% of schools are classified as “difficult to access”. In secondary education the situation is very similar: 34% of schools are located in large urban centres (Athens-Attiki and Thessaloniki-Central Macedonia) but the rest are much more sparsely distributed; 18% of the schools are located on islands; 5.5% of schools, of which more than half are located on islands, are classified as “difficult to access”. This has direct consequences for the financing and management of the system.

Table 1.2. Geographical distribution of nurseries, primary and secondary schools, 2017

|

District |

Overall number of primary schools |

Number of difficult to access primary schools |

Percentage of difficult to access primary schools |

Overall number of secondary schools |

Number of difficult to access secondary schools |

Percentage of difficult to access primary schools |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Attica |

2 047 |

4 |

0.2% |

865 |

2 |

0.2% |

|

Central Greece |

631 |

35 |

5.6% |

218 |

7 |

3.2% |

|

Central Macedonia |

1 756 |

31 |

1.8% |

556 |

9 |

1.6% |

|

Crete |

769 |

22 |

2.9% |

218 |

9 |

4.1% |

|

Eastern Macedonia and Thrace |

705 |

47 |

6.7% |

186 |

23 |

12.4% |

|

Epirus |

429 |

m |

M |

147 |

3 |

2.0% |

|

Ionian Islands |

262 |

15 |

5.7% |

89 |

12 |

13.5% |

|

North Aegean |

292 |

40 |

13.7% |

107 |

24 |

22.4% |

|

Peloponnese |

603 |

23 |

3.8% |

219 |

12 |

5.5% |

|

South Aegean |

411 |

63 |

15.3% |

147 |

50 |

34.0% |

|

Thessaly |

827 |

19 |

2.3% |

238 |

8 |

3.4% |

|

Western Greece |

847 |

38 |

4.5% |

260 |

15 |

5.8% |

|

Western Macedonia |

351 |

9 |

2.6% |

122 |

12 |

9.8% |

Source: Roussakis, Y. (2017[53]), OECD Review, Partial Background Report for Greece, Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs.

Shadow education

One of the major issues for public debate of education policy in Greece is the question of criteria for access to different levels of schooling, especially university (Varnava-Skoura, Vergidis and Kassimi, 2008[72]). Before the expansion of the country’s tertiary offer in the 1980s, each year only one-third of all candidates could expect to secure a place at one of the then 18 universities and 12 Technological Education Institutions (TEIs) in Greece3 (Tsakloglou and Antoninis, 1999[73]). Despite the now expanded university and TEIs offer, in 2017 there were just over 96 000 students sitting the entrance exams, as compared to just over 70 000 places available at state institutions around the country (see Table 3.2). As long as there is a cap on the number of places available in tertiary institutions, as well as significant disparity in the prestige of different tertiary institutions, the Panhellenic examinations at the end of upper secondary education will remain a key moment in a young person’s life. As discussed in detail Chapter 5 of this volume, a young person’s results in these exams have major consequences for their life and career prospects.

Several historical events and social factors have driven a long-standing demand for private tutoring in Greece:

Following the Greek-Turkish War of 1919-22, over one million Greeks (or those identified as such) were forcibly relocated from eastern Thrace and Asia Minor and around 350 000 Turks were expelled from the Greek mainland and islands between 1923 and 1930 (Özsu, 2017[74]). This sudden influx (which represented a 25% increase in population) led to a simultaneous decrease in the quality of secondary schools and an increased demand for higher education. As a result, entrance examinations for higher education institutions were instituted and the foundations for a shadow education sector were laid (Kassotakis and Verdis, 2013[75]; Polychronakis, 2004, p. 38[76]).

After the Greek Civil War of 1946-49, many school teachers with left-wing affiliations were forced from their posts; a number of these began to work as private tutors (Kassotakis and Verdis, 2013[75]).

Under the dictatorship of 1967-74 teachers who opposed the regime were excluded from teaching at state schools. At the primary and secondary education level, more than 250 teachers were reportedly dismissed from state schools together with about fifty officials from the Ministry of Education (Anonymous, 1972[77]). Many of these teachers offered private lessons instead (Kassotakis and Verdis, 2013[75]).

Mark Bray first popularised the term “shadow” education for this for-profit, after-school tutoring because it mimicked the regular curriculum, used many of the same materials and existed in something of a shadow of legitimacy and legality (Bray, 2009[78]; Bray and Lykins, 2012[79]). On the other hand, private tutoring has also been characterised as a form of supplementary education which can compensate for limited schooling opportunities and serve individual needs for academic remediation. The policy challenge is therefore to capitalise on any improvement to academic excellence and equity in public education it might bring, while counteracting its potential threats to public schools (Lee, 2007[80]).

Shadow education is a growing industry worldwide. It is estimated that approximately 90% of Korean and approximately 60% of West Bengali elementary school students participate in some form of shadow education, as do approximately 85% of Chinese students and 60% of students at upper secondary school in Kazakhstan (Bray and Lykins, 2012[79]). In both Greece and Japan there is a widespread belief among parents that investment in shadow education leads to higher levels of educational achievement (and with it admission to high-ranking tertiary institutions) (Bray and Lykins, 2012[79]). Another key driver was dissatisfaction with school quality: this was a common reason given by parents for sending their children to shadow education in Japan although contrary to the Korean experience, where enrolment rates in shadow education fell when school quality improved, parents in Japan have continued to send their children even though school performance is strong (Jones, 2013[81]; Jones, 2011[82]).

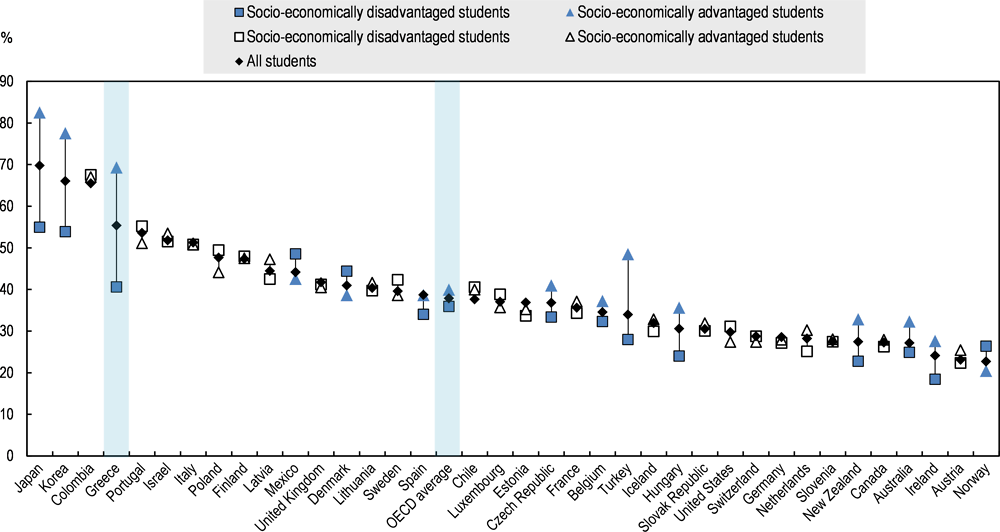

According to PISA 2012, overall 55% of 15-year-olds reported attending after-school lessons in mathematics. This share of after-school mathematics was among the highest in OECD countries and is significantly higher than the OECD average of 38%. In particular, socio-economically advantaged students are far more likely to attend after-school lessons in mathematics than disadvantaged students (see Figure 1.15). The difference between the two groups in Greece is also among the largest across OECD, along with Japan and Korea (OECD, 2013[59]).

Figure 1.15. Percentage of students taking after-school lessons, 2012

Note: White symbols represent differences that are not statistically significant. ESCS refers to the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status. OECD member countries are ranked in descending order of the difference in the percentages between students who are in the bottom quarter of ESCS and those in the top quarter (top-bottom).

Source: OECD (2013[55]), PISA 2012 Results: What Makes Schools Successful (Volume IV): Resources, Policies and Practices, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264201156-en.

It is difficult to find reliable data on the number of students participating in shadow education in Greece. A 2014 study of 534 households showed that 99% of students in their final year of secondary school attended either a frontistirio (54%), private lessons (21%), or both (24%). Only 1% of respondents’ children had not resorted to shadow education in preparation for the university entrance exam (Liodaki and Liodakis, 2016[83]; Palmos Analysis, 2015[84]). PISA 2012 asked students if they attended supplementary education in after-school lessons (see Figure 1.15).

Private tutoring in Greece is often referred to as παραπαιδεία (parapedi – parallel education), which has highly negative connotations4. The MofERRA's 2017 three-year plan refers to it in these terms:

Secondary education has been replaced by shadow education (private tuition centres), a fact which undermines the educational process itself. The effects of this situation were particularly devastating for the upper classes of the upper secondary school or Lyceum]. This problem is not only educational but also profoundly social (Ministry of Education Research and Religious Affairs, 2017[85]).

A 2011 survey of 1 200 secondary school students in Georgia, perhaps comparable given the cultural ties and the Greek diaspora living there, found that 25% of them had received after-school tutoring, with the rates rising to 35% in the capital city and as low as 19% in villages (Machabeli, Bregvadze and Apkhazava, 2011[86]). This urban/rural divide is also to be found in Greece (Table 1.3), with a 14 percentage point difference between access to and use of out-of-school tutoring in rural and urban areas. Given the widely perceived positive correlation between out-of-school tutoring and success in the Panhellenic examination for admission to higher education, this would indicate a further source of inequality between these groups.

Table 1.3. Out-of-school tutoring use in urban, semi-urban and rural areas, 2015

|

|

Urban (population more than 10 000) |

Semi-urban (population up to 10 000) |

Rural (population up to 2 000) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Receive out-of-school support: |

84% |

84% |

70% |

|

● At a Frontistirio |

61% |

45% |

50% |

|

● With a private tutor only |

28% |

47% |

38% |

|

● At a Frontistirio and with a private tutor |

9% |

5% |

12% |

Source: Palmos Analysis (2015[84]), Pan-Hellenic Research for the Association of Teachers of Attica (TEFA): Out-of-school Support in Secondary Education (in Greek), Association of Educational Tutors of Attica (SEFA), Athens, http://palmosanalysis.com/panelladiki-ereyna-gia-sefa/.

Shadow education in Greece takes place in groups at afternoon and evening cram schools (referred to collectively as frontistiria – an individual school is a frontistirio) and in one-on-one private lessons known as idietera mathimata, or idietera. Typically, frontistiria offer classes between 4 and 7 p.m. This is only possible because obligatory classes in public school units begin at 8:10 in the morning and conclude at 2:10 in early afternoon. There are sometimes also classes on Saturday mornings. Frontistiria offer classroom-based education, but with small classes of between five and eight students. The price for parents depends on class size, so in poorer areas class sizes may be larger. Parallel to frontistiria, there are also individual private tutors, charging higher prices, and sometimes operating in the shadow economy. Frontistiria follow the same prescriptive and tightly organised teaching schedule as public school units. This is because the goal for most is to help their students pass the Panhellenic examination, which they consider to be closely aligned with the obligatory teaching schedule. There is anecdotal evidence that some of them even plan their work in such a way that specific subject topics are covered by frontistirio teachers before they are covered in public school units, for example a week earlier. In this way they prepare their students not only for the Panhellenic examination, but also, facilitate their participation and learning in the public school unit, which may contribute to their success.

Frontistiria can further be divided into those that prepare students for the Panhellenic examination and those that support lower secondary students, teach foreign languages, music lessons and digital skills that are not covered adequately in the formal education system (Kassotakis and Verdis, 2013[75]). All frontistiria are licensed by the MofERRA and on opening their premises inspected, but no quality control on their teaching, materials or staff is imposed by the MofERRA (Kassotakis and Verdis, 2013[75]). Shadow education is often, but not always, organised in illegal or semi-legal manner, with unmonitored scope, unregulated activities, and undeclared, untaxed revenues. Greek shadow education is startlingly different from this typical image. In Greece, much of the shadow education sector takes the form of a legal and publicly recognised parallel education system, well regulated by the state, and functioning in a competitive environment.

In order to start a frontistirio, an individual or a company needs to receive a permit from the MofERRA, which is issued after the MofERRA checks the facilities for safety and collects start-up fee (Kassotakis and Verdis, 2013[75]). The review team noted that some experts of the MofERRA are drawn from the frontistiria establishment. There are also active associations of frontistirio owners and of frontistirio teachers. Many frontistiria advertise heavily on the Internet and in the print media. Like any business, frontistiria are also subject to the same laws on false or misleading advertising. For example, many frontistiria publish data about the success rate of their students in the Panhellenic examination, clearly taking full credit for students’ success and assuming that public school units did not contribute in any way. Some frontistiria publish their own textbooks (although some of these are limited to sets of exercises with and without solutions).

Frontistiria operate in large, well-equipped facilities, often located close to the secondary school units from which they draw much of their enrolment. There is nevertheless a city-wide market for these supplemental educational services, at least in larger cities.

It is difficult to find reliable data on the number of students participating in out-of-school tutoring beyond the self-reported data in PISA. Nevertheless, the national association of frontistiria owners (which does not include all frontistiria) reported that in the 2013/14 school year, their members enrolled 183 000 students (61% in the upper secondary level and 35% in lower secondary level) at 2 200 separate establishments – down from 2 500 in the year 2000 (Panayotopoulos, 2000[87]). These numbers reflect a remarkable resurgence as compared to historical trends and demonstrate that high rates of shadow education participation are by no means inevitable: in 1979/80 there were an estimated 1 232 Ministry-approved frontistiria enrolling just over 176 000 students, but by 1983/84 their number had shrunk to 1 132 and student numbers had fallen to 82 598 (OECD, 1997[88]). According to official (but unpublished) data, in the 2010/11 school year, over 149 000 students attended 2 352 secondary frontistiria, which employed 18 159 teachers (Kassotakis and Verdis, 2013[75]). This represents about 45% of all students of general and vocational upper secondary schools. In comparison, in the same school year there were 1 788 public upper secondary schools operating in Greece. Some estimate that almost all upper secondary school students in their last year attend either a frontistirio, individual private tutoring, or both (Kassotakis and Verdis, 2013[75]). The 2013/14 participation rates represent 20% of the total lower secondary school enrolment of 319 950 in 2013/14 and 30% of the entire upper secondary school student population of 369 889 for the same school year. Students who had the assistance of private tutors can be added to this number (Palmos Analysis, 2015[84]). A 2014 survey of 534 households whose children had taken the Panhellenic examination in the last five years found that 99% of students in their final year of upper secondary school attended either a frontistirio (54%), private lessons (21%), or both (24%) (Liodaki and Liodakis, 2016[83]). A random survey of 2 370 first year students in 58 departments across seven major Greek universities in the spring of 2014 found that almost half (48.9%) attended frontistiria, 14.2% engaged private tutors, and approximately one third of the sample did both (Ioakimidis et al., 2000[89]).

It is therefore safe to say that much of the shadow education in Greece, unlike in many other countries, does not operate in the shadows at all. It is a visible, vibrant, regulated, official, competitive component of the Greek education system, enrolling a clear majority of secondary school students. This position of the shadow education system would not be possible if it did not serve vital, indispensable education purposes, in parallel and in addition to the public education sector. This ensures its stability, as evidenced in multiple reviews over many years (OECD, 1997[88]). There is also some adaptation of the public school unit system to the existence and needs of shadow education, as seen for example in extremely short school days (unlike in many European Union and OECD countries, public school units in Greece offer remarkably few afternoon, after-class activities, allowing their students to attend long sessions at fronstistiria – see Figure 3.3 in Chapter 3). Any plans to scale down or eliminate the shadow education would require major reforms of the overall functioning of Greek education.

1.3.4. School curriculum

In primary education, there is a single type of all-day primary education services are provided at all primary schools with a revised timetable and curriculum. Primary education is free, including the distribution of school textbooks and supplementary learning resources for all students. Curricula are centrally developed and nationally implemented for all schools and at all levels of Greek education.

Current primary education national curricula fall under the Cross Thematic Curriculum Framework for Compulsory Education (DEPPS) (Ministerial Decision 21072β/Γ2/28-2-2003). This cross-thematic approach defines the structure of teaching on the basis of a balanced horizontal and vertical distribution of educational material. It promotes cognitive subjects interconnection as well as comprehensive analysis of key concepts. In addition, a "Flexible Zone of Interdisciplinary and Creative Activities" has been added to the framework (Eurydice, 2016[45]).

National curricula for each subject are organised into six levels (each of them corresponding to one out of six primary school grades or into fewer levels depending on the subject). The national curricula specify subjects' aims, educational objectives, thematic units, indicative activities and cross-thematic projects. The syllabus for the subjects taught during mainstream school hours is compulsory for all students at all primary school grades, with the following subjects taught: Greek, mathematics, natural sciences, geography, history, social and political studies as well as foreign languages, arts education, information communication technology (ICT) skills, physical education and the “flexible zone”, with the aim to improve the capacities and skills of primary students through activities centred on specific objectives (OECD, 2009[36]; Eurydice, 2016[45]).

In lower secondary education, the curricula concentrates on Greek language and literature, sciences, humanities and social sciences, foreign languages, technology and ICT, physical education, home economics and culture. The school day starts at 8:15 a.m. and ends at 2:15 p.m. Subjects taught in lower secondary schools are compulsory for all students of the same class, except for the second foreign language subject which, in accordance with Ministerial Decisions 137429/Γ2/02-09-2014 and121072/Δ2/22-6-2016, comes with three (3) language options: French, German and Italian.

In upper secondary education provides general non-compulsory education (Lyceum). Attendance lasts for three years and includes grades Α, Β, and C. The first year is focused on general education for a total of 35 hours per week. There are nine general education subjects for all students plus two elective subjects chosen among four subjects (Eurydice, 2017[46]).

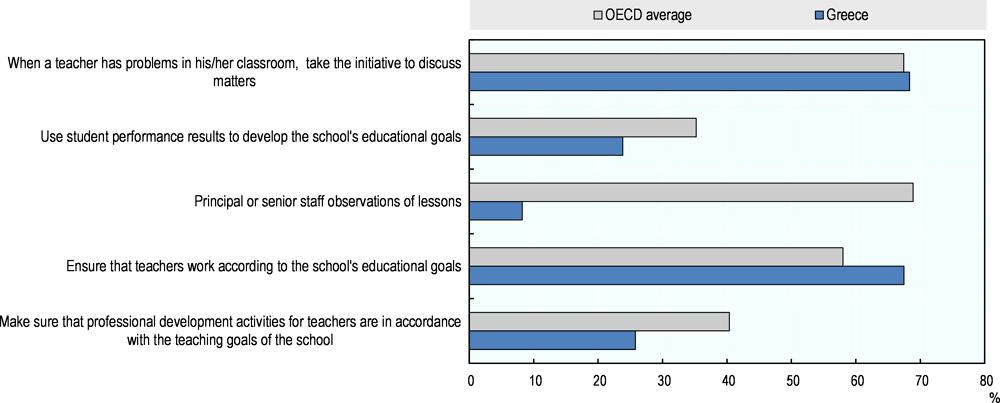

1.3.5. School governance and leadership

Schools in Greece operate in an environment of low autonomy, according to international comparative data from the OECD Education at a Glance and PISA. More than 80% of school decisions are adopted by the national government in Greece, in relation to 35% across OECD countries (Figure 1.16). This is also the case for curricular decisions, resources or assessment policies (Figure 1.16). This reflects the way in which education governance is structured in Greece, with the central government making decisions on all areas related to schools, including the selection of teachers and educational staff. Schools, their principals and teachers have little freedom at the school level.

Figure 1.16. Distribution across the education system of responsibility for school resources, 2015

Source: OECD (2016[90]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en.

PISA results suggest that school autonomy in relation to content is more closely associated with educational performance than is autonomy in decision making concerning resource allocation. School systems that provide schools with greater discretion in decisions on student assessment policies, courses offered, course content and textbooks used, tend to perform at higher levels in PISA (OECD, 2012[91]; OECD, 2016[90]). However, further evidence also shows that while autonomy in content can contribute to make a difference, this depends on the capacity and quality of those working in schools to be able to use such autonomy effectively (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2014[92]).

In Greece, school principals have traditionally played a more administrative and management role. Figure 1.17 shows the lower levels of engagement in more pedagogical issues around teachers and schools.

Figure 1.17. School directors levels of pedagogical leadership, 2012

Source: OECD (2013[55]), PISA 2012 Results: What Makes Schools Successful (Volume IV): Resources, Policies and Practices, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264201156-en.

In Greece, the selection process for principals has been based on academic qualifications, years in service, and contribution to educational work and personality (assessed through a secret teacher ballot) in the school to which they are applying, and could benefit from a more professional process aligned to expectations. In 2017, this process has been complemented with the assessment of the candidate through an interview and other criteria, presented in Chapter 4.

In terms of training, a 2010 law (Law L.3848/2010) established that attainment of a certificate of administrative capacity should be required as a selection criterion for school principals, but this apparently has not been implemented. Conversely, the MofERRA reports that since 2012, the Institute of Training of the National Centre of Public Administration and Local Government has designed and implemented specialised training programmes for principals, but there is lack of quantitative or qualitative data on the outcomes of these programmes.

School principal appraisal appears to be limited to the selection and recruitment process, and this appears to be of a more administrative nature than focused on improvement (OECD, 2015[60]).

1.3.6. The teaching profession

With regards to the teaching profession, prospective teachers in primary education and secondary education must complete a first cycle degree (UNESCO, 2015[93]). Those secondary school teachers that study in teacher faculties are expected to follow a pre-service teacher training programme of four years. They are trained and qualified in the undergraduate programmes of study offered by the relevant university departments and have a mandatory teaching practicum (OECD, 2015[60]). However, prospective teachers can also follow more general tertiary courses and add a Certificate of Educational Attainment in order to qualify as a teacher. New teachers must participate in an induction programme, which lasts less than a year. The OECD review team was told that many teachers have higher levels of education (master and PhD level), although no statistics were available at the time of writing to support this.

Recruitment, which is competitive, is centrally administered. All teacher candidates for permanent or substitute positions participate in the Supreme Council for Civil Personnel Selection (ASEP) examination. Appointment to schools, if places are available, is then based on a ranking system, which takes into account the ASEP examination results, academic qualifications, individual preferences, the time of application, social criteria, and prior teaching service (European Commission, 2013[94]; UNESCO, 2015[93]). However, with the freeze in teacher hiring, the ASEP examination has not been administered since 2008.

Table 1.4. Years of service and teaching hours: Primary and secondary, 2017

|

Primary education teachers serving in schools with more than 4 classes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Years of service |

0-10 |

10-15 |

15-20 |

>20 |

|

Weekly teaching hours |

24 |

23 |

22 |

21 |

|

Secondary education PE scale (teachers with university degrees) |

||||

|

Years of service |

0-6 |

7-12 |

13-20 |

>20 |

|

Weekly teaching hours |

23 |

21 |

20 |

18 |

|

Secondary education TE scale (teachers with TEI or equivalent degrees) |

||||

|

Years of service |

0-7 |

8-13 |

14-20 |

> 20 |

|

Weekly teaching hours |

24 |

21 |

20 |

18 |

|

Secondary education DE scale (teachers with non-tertiary education degrees - VET) |

||||

|

Years of service |

0-20 |

>20 |

||

|

Weekly teaching hours |

28 (chief-technicians) 30 (technicians) |

26 (chief-technicians) 30 (technicians) |

||

Note: Teachers in small schools (1-3 classes) teach 25 hours a week, whatever their length of service.

Source: Roussakis, Y. (2017[53]), OECD Review, Partial Background Report for Greece, Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs.

In Greece, the starting statutory salary for teachers at the pre-primary, primary, lower and upper secondary general secondary teachers is exactly the same. In real terms, teachers’ salaries in Greece are among the lowest in the OECD. In 2015, the average statutory salary in Greece for teachers with 15 years’ experience was USD 25 077 across all levels of education, compared to an average of USD 44 623 at lower secondary level, and USD 46 631 at upper secondary level across OECD member countries.

Greek teachers also have one of the lightest teaching loads in the OECD, according to comparative data. Annually, a Greek general lower secondary education teacher teaches nearly 120 hours fewer than the OECD average. Greek authorities report that this is partly explained by the multiple non-teaching tasks teachers take on in light of the lack of administrative staff in Greek schools.

In terms of career progression, the number of overall hours decreases with the number of years of service, implying that those with more experience teach fewer hours than younger teachers (Table 1.4, Figure 1.18). Greek authorities report that this is a measure to alleviate teacher burn-out, as there are no possibilities for teachers to reduce their load for professional development (MofERRA, 2018[95]).

Figure 1.18. Number of teaching hours per year in general lower secondary education, 2015

Note: Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the number of teaching hours per year in general upper secondary education in 2015.

Source: OECD (2017[28]), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en.

The crisis has had an impact for teachers on several fronts. Teachers’ salaries had, by 2017, decreased to 74% of their 2008 level (OECD, 2017[4]). In addition, as there has been a freeze in the hiring of teachers as civil servants, teachers hired since the crisis have substitute status, with annual contracts instead of long-term civil service status. According to the MofERRA, the teacher workforce now includes 22 000 substitute teachers, the majority of whom move between schools each year. In 2015/16, substitute teachers represented up a 14.1% of all teachers (up from 8% in 2011/12) (Roussakis, 2017[53]).

In terms of teaching practice, teachers can have some stability challenges. While teachers may request to work in a specific region, not all requests can be fulfilled. The result is a rotation of a significant portion of the workforce as substitute teachers sent to different schools every year and sometimes well into the school year.

Officials within the Ministry have expressed their concern as to the impact the economic crisis has had on teacher morale and resulting low levels of trust in the education system. A recent European study on the attractiveness of the teaching profession confirms these observations. It found that the MofERRA in Greece had presented a negative picture of teachers in the media, accusing them of being lazy and of resisting change. The study, which was carried out in 2012, also included a large-scale online survey of stakeholders in the education system. When teachers asked if they might envisage looking for another job, more than 60% of Greek teachers answered affirmatively (European Commission, 2013[94])5.