Tertiary education in Greece is at the crossroads. This chapter analyses and provides recommendations to enhance tertiary education governance, quality and links to the labour market in Greece. A population with high educational attainment presently has low skill levels as measured by the OECD’s Adult Skills Survey. There are ongoing mismatches between the skills graduates have and the skills employers require, alongside high levels of unemployment. There is a need to build a national-level consensus on what tertiary education is for, on its governance, on how it interfaces with the labour market, and on how quality is to be assured.

Education for a Bright Future in Greece

Chapter 5. How higher education can help Greece restore prosperity

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

The Greek tertiary education system offers opportunities for economic growth and social cohesion; it is one of the most powerful means of improving the skills of the workforce, it can help counter the country’s fall in productivity and it is an important mechanism for strengthening the innovation system.

The tertiary education aspects of this review cover three broad areas:

Governance:

the framework for governance in the Greek higher education system, the regulation of the system, the autonomy of higher education institutions (HEIs) – including the rights of institutions in decision making on organisational, financial and scientific matters

the network of higher education provision in Greece

the role and composition of the governing bodies of HEIs.

The resourcing of the system:

the approach to funding

alternative sources of funding for institutions, including the role of tuition fees in graduate education

improving efficiency in institutions.

Quality and quality assurance:

the current performance of the system, including completion and dropout rates in HEIs and the outcomes of the system

the quality assurance of higher education programmes and the role of the Hellenic Quality Assurance and Accreditation Agency (ADIP)

internationalisation of Greek higher education.

The analysis in this chapter first summarises the skills profile of the Greek population, reviews the state of tertiary education in Greece, then reports on policy issues facing the system, drawn from the OECD review team’s visits and interviews, from data on higher education in Greece and from the research literature. Finally, it lays out some policy options, drawn from the analysis of the challenges and from the practices of other OECD countries.

5.1. Tertiary education at a crossroad

5.1.1. A population with high educational attainment but low skills and high unemployment

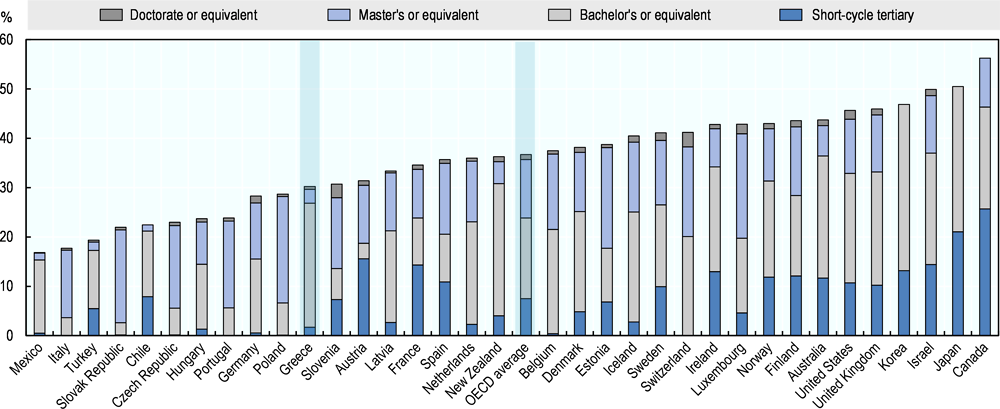

Educational attainment in Greece is around the OECD average. Around 25% of the population hold a bachelor’s degree – well above the OECD mean of 16%. However, the proportion holding a qualification at master or doctoral level in Greece is relatively low; overall, the proportion with a bachelor’s degree or higher is around the OECD mean of 29%. In the 25-34 year-old age group – the group of people likely to be at the core of the workforce over the next three decades – 41% have a tertiary qualification, close to the OECD mean of 43% (OECD, 2017[1]).

Figure 5.1. Proportion of the population holding a tertiary qualification, 2016

Source: OECD (2017[1]), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en.

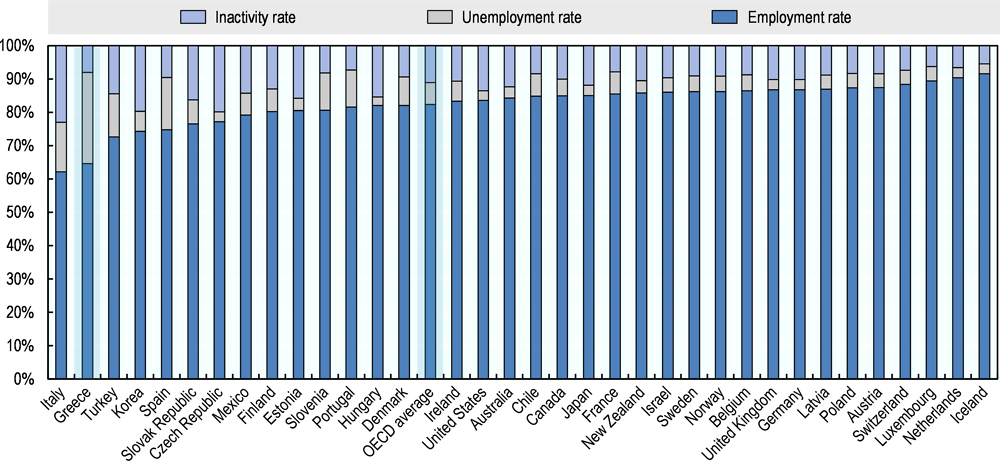

Employment outcomes for graduates, as shown in Figure 5.2, are poor: in the wake of the economic crisis, employment rates are relatively low, even for those who hold educational qualifications, and especially for young people. In the 25-34 year age group, 66% of tertiary graduates were in employment in Greece, down from 77% in 2010 and compared with the OECD mean of 83%. That employment rate is second lowest in the OECD (above only Italy, where the employment rate of tertiary graduates in that age range was 64%). Unemployment of tertiary qualified 25-34 year-olds is correspondingly high, the highest in the OECD at 28%, compared with the OECD mean of 6.6% (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]; OECD, 2017[1]).

Figure 5.2. Working status of tertiary qualified people aged 25-34, 2016

Source: OECD (2017[1]), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en.

Skills of the population are lower than in other countries

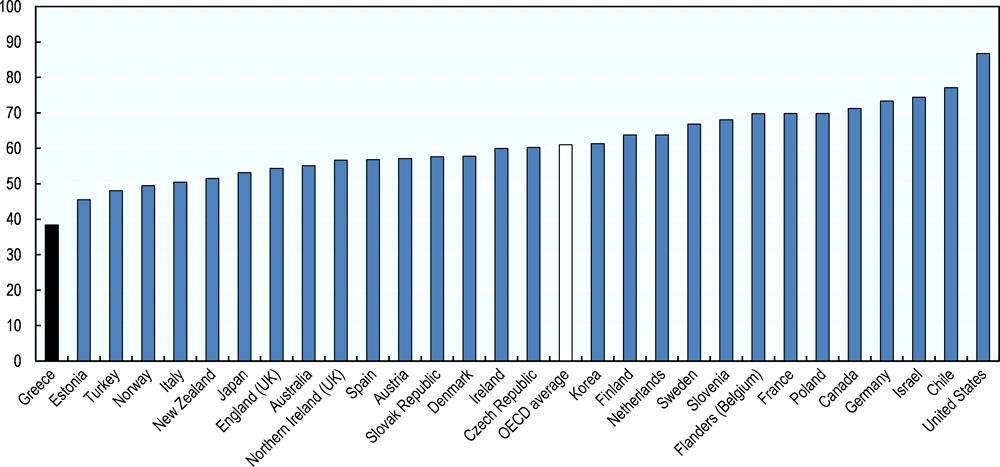

Despite the levels of educational attainment in Greece, the OECD’s Survey of Adult Skills1, conducted in Greece in 2015, shows that the skills of the adult population in Greece are lower than in most OECD countries. There is a lower proportion in the high-skilled categories in the three skill domains measured in the survey (literacy, numeracy and problem solving in technology-rich environments) – and a higher proportion in the low-skilled categories (OECD, 2016[3]) (see Chapter 1).

Of particular concern is the skill level of higher education graduates. While those with a bachelor degree or higher were found in the survey to be more skilled than those without a degree, the skill margin is significantly less than is typical among the countries that participated in the Survey of Adult Skills (OECD, 2016[4]). Tertiary-educated Greek adults aged 25-65 score 19 points higher in literacy than those with an upper secondary qualification (the OECD average difference is 33 points) and 38 points higher than those without an upper secondary qualification (the OECD average difference is 61 points) (OECD, 2016[3]).

This result raises questions about the effectiveness of the Greek tertiary education system in adding skills to the individuals who participate in it. One part of the reason for the low-skill premium for a tertiary qualification in Greece may be the high emigration of many of the highest skilled and most successful young people, in response to the economic crisis Greece has faced. As noted in Chapter 1, a high proportion of emigrants between the ages of 25 and 39 were graduates or holders of postgraduate qualifications (Kasimis and Kassimi, 2004[5]; Labrianidis and Pratsinakis, 2014[6]). At the same time, immigration to Greece by trained and skilled young people is low – likely because of the difficulty of obtaining employment in Greece. Questions remain, however, over the effectiveness of the Greek system in adding value to its students.

Figure 5.3. Difference in literacy proficiency, 2015

Note: Year of reference for Greece is 2015. All other countries: Year of reference 2012. Data for Belgium refer only to Flanders and data for the United Kingdom refer to England and Northern Ireland jointly.

Source: OECD (2016[3]), Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264258051-en.

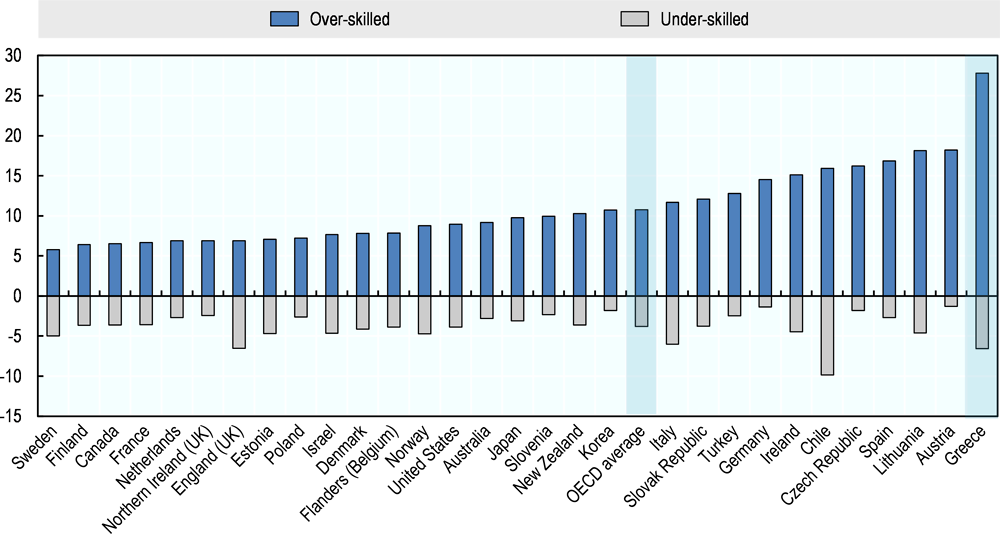

Mismatches between the skills workers have and the skills they need

There is a high level of mismatch between the literacy skills Greek workers have and those they need in their jobs. Around 28% of workers in Greece have a higher level of literacy than they need at work – the largest proportion across all countries participating in the Survey of Adult Skills, and compared to the OECD average of 11%. Around 7% of workers have lower literacy proficiency than required for their job, against the OECD average of 3.8% (OECD, 2016[4]).

Figure 5.4. Level of mismatch in the working population aged 25-64, 2015

Note: Year of reference for Greece is 2015. All other countries: Year of reference 2012. Data for Belgium refer only to Flanders and data for the United Kingdom refer to England and Northern Ireland jointly.

Source: OECD (2016[3]), Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264258051-en.

In many participating countries, there is a positive relationship between information processing skills and labour market outcomes. In Greece, however, it is educational attainment, rather than proficiency, that has the strongest impact on the likelihood of being employed and on earning higher wages. This suggests that Greek employers make employment decisions on the basis of applicants’ credentials, rather than on their demonstrated skills (OECD, 2016[3]).

The low-skill profile required by employers is likely a factor in the low and falling productivity seen over the course of the recession (OECD, 2017[7]). It also goes some way to explaining the difficulties faced by Greek employers in finding people with the appropriate skills for job vacancies identified in the 2015 Manpower Survey, and as reported in Chapter 1 and Figure 1.3 of this report (Manpower Group, 2016[8]).

These results paint a picture of a complex skills environment. It is likely that the high rate of graduate unemployment in Greece has encouraged graduates to seek low-skilled jobs; as a result, many employees work in jobs for which they are over-skilled, despite the fact that graduate skill levels in Greece are lower than in other European countries. The extent of over-skilling may also reflect the nature of the Greek economy, with a higher proportion of lower-skill industries than is typical in European countries. However, those firms operating in industries that require the highest skill levels struggle to compete for skills, given the relatively low overall skill profile of the country and given the fact that a high proportion of young emigrants have high levels of qualifications2 (Labrianidis and Pratsinakis, 2014[6]).

A complicating factor is the emerging threat posed to employment by the growth of automation. As noted in Chapter 1 and Figure 1.4 of this report, analysis of the skill requirements of the jobs of Greek respondents to the Survey of Adult Skills suggests that nearly 40% of Greek employment is in occupations that have a significant risk of being automated – above the OECD average of 34% (Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn, 2016[9]).

The challenge for Greece is to increase the proportion of the population with higher skills – to meet the skills shortage facing some employers, to enable the economy to move to a higher-skilled, higher-value footing and to help manage the risks to individuals’ employment of increasing automation.

Challenging demographic trends

The birth cohorts working through the education system are smaller than in the recent past; the number of live births dropped 22% between 2008 and 2014 (European Commission, 2016[10]). Over the next 15 years, that reduced cohort size will flow through to the core age for tertiary education population, while the effects of current high emigration will also reduce the size of the higher education intake. As a result, it is likely that fewer people will gain higher education qualifications in the medium term. If Greece is to lift productivity and to regain and maintain its former economic strength, there is a need to ensure that the higher education system is able to improve the efficiency and relevance of its programmes so that it can supply the skills, including non-cognitive skills, that the labour market needs.

5.1.2. The role of the higher education system

Education, and the higher education sector in particular, is an essential part of the solution to these issues. Part of the solution also involves better take-up of quality lifelong learning. As technological change accelerates, firms need to adapt and to ensure that their employees acquire appropriate skills. The forecast ageing of the population poses risks to the supply of skills while the risks from the forecast growth in automation suggests that the adult population needs to keep updating its skills (Council of the European Union, 2011[11]; UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, 2009[12]).

Lifelong learning is crucial both to keep workers’ knowledge up-to-date and to redirect workers towards economic sectors less threatened by technological replacement. The OECD identifies the need to move from a complete reliance on initial education towards fostering lifelong and skills-oriented learning (OECD, 2016[13]). In an uncertain environment, lifelong learning and training can tackle human capital depreciation and the shrinking of the talent pool.

Adult participation in lifelong learning in Greece rose after 2011, despite the economic downturn3 (Karalis, 2017[14]). However, compared with other European countries, participation is low (Karalis, 2017[14]; OECD, 2016[3]); in 2015, 80% of the Greek population aged 25-64 had no engagement with formal or non-formal education, against an OECD mean of 50% (OECD, 2016[4]). The Greek government has recognised the importance of this shortcoming; it has recently encouraged the creation of lifelong learning centres at higher education institutions.

5.1.3. The Greek higher education system

Greece has a long tradition in higher education and the Greek people place a high value on that tradition and on their higher education system. Greek nationals, graduates of the Greek higher education system, can be found throughout the academic world in leading scholarly roles.

Visiting higher education institutions, the OECD review team was impressed by the level of commitment and enthusiasm of students and their teachers and by the determination of institutional leaders to manage their institutions through a challenging period.

The current system of higher education in Greece

The shape of the system

In modern Greece, higher education institutions (HEIs) include 22 universities as well as 14 Technological Education Institutes (TEIs). While universities deliver a general academic education, TEIs have a mission to conduct higher education at bachelor’s and postgraduate level in science, technology and arts, but with an applied and vocational focus (European University Association, 2015[15]).

Table 5.1. The Greek higher education system

|

2002/03 |

2008/09 |

2014/15 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of HEIs |

|||

|

Universities |

19 |

21 |

22 |

|

TEIs |

15 |

16 |

14 |

|

Number of teaching staff |

|||

|

Universities |

11 079 |

13 058 |

10 770 |

|

TEIs |

10 948 |

10 882 |

4 140 |

|

Number of students |

|||

|

Universities |

175 597 |

171 882 |

190 835 |

|

TEIs |

124 874 |

112 337 |

99 391 |

|

Master’s and doctoral students |

28 952 |

52 574 |

62 973 |

|

Percentage of Greek 18 and 19 year-olds in their first year higher education |

|||

|

Universities |

14.0% |

17.1% |

23.7% |

|

TEIs |

12.5% |

9.5% |

10.4% |

Source: Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE) (2017[2]), Higher Education in Greece: Impact of the crisis and challenges, Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research, Athens.

The Greek public places great value on higher education

The population of Greece places a high value on higher education. Having a university degree mitigates the risk of unemployment and means that a person is more likely to earn a higher income (Mitrakos, Tsakloglou and Cholezas I, 2010[16]; OECD, 2017[1]). As discussed in earlier chapters, families make substantial financial sacrifices to enable their children to achieve good scores in the Panhellenic entrance examination, in order to secure a place in a good department of a Greek higher education institution (HEI) (OECD, 2017[17]; Psacharopoulos and Papakonstantinou, 2005[18]; Sianou-Kyrgiou, 2008[19]; Saiti and Prokopiadou, 2008[20]). A significant number of families send their children overseas for a university education (Tsakloglou and Cholezas, 2005[21]).

One consequence of the high competition to obtain places in prestige programmes and institutions, and the requirement to pay for additional classes (at frontistirio) to prepare for the Panhellenic examination, is that the tertiary education system has become stratified on socio-economic lines, both at an institutional and departmental levels (Sianou-Kyrgiou, 2010[22]; Sianou-Kyrgiou and Tsiplakides, 2011[23]; Tsakloglou and Cholezas, 2005[21]). Because of the inequities built into the earlier stages of the education system and into the rationing of higher education places, the government’s investment in the tertiary education system is disproportionately captured by those from higher SES groups (Saiti and Prokopiadou, 2008[20]; Sianou-Kyrgiou and Tsiplakides, 2011[23]).

The government has committed to revising the university admissions process so that students’ Panhellenic entrance examination scores will count for just 80% rather than 100% of the admission decision. The other 20% will be determined by their teachers’ assessments (see Chapters 2, 3 and 4).

Governance and regulation

In 2017, a new law (4485/2017) consolidated the regulatory framework for higher education. The new law defined the structures for HEIs’ internal decision making; it set out the composition and role of the senate and the rector’s council, the two key internal management boards, so as to counter the risk of the politicisation of institutional leadership. This law also created regional councils responsible for developing strategic plans for the development of higher education and research in the region – including exploring the synergies between the HEIs and the research institutes in the region and looking to align with the development priorities for the region. It also strengthened quality assurance in postgraduate programmes, provided for institutions to create two-year vocational qualifications4 and created lifelong learning centres in institutions. The law was developed following an extensive period of consultation with the tertiary education sector.

Free public education

Like many European countries, Greece has no tuition fees in undergraduate higher education. This is provided for under Article 16 of the Greek Constitution which affirms that education is a core function of the state and that the public education system aims to help people to become free and responsible citizens. It specifies that Greek citizens have the right to free education at all levels in public educational institutions (Hellenic Republic, 2008[24]).

This article is interpreted as covering the whole of a person’s initial education – that is to the level of a first higher education qualification. As a result, institutions may (and do) charge fees for master’s degrees but not for undergraduate studies.

The new law (4485/2017) imposed restrictions on the level and setting of fees for postgraduate qualifications, which had previously been set at the discretion of the institution. Institutions imposing such fees have to have the resourcing and the budget for each degree approved by the Ministry. No more than 30% of the revenue generated by the degree may be used as a contribution to institutional overheads5. This provision has caused some rectors concern, given the importance of fee revenue to institutions in a period of highly constrained resourcing.

Private higher education

The private higher education sector in Greece is small. An article in the publication ToVima6 estimates that there are 15 000 students enrolled in private colleges. Under the Greek laws 4093/2012 and 4111/2013, colleges are designated as “providers of non-formal post-secondary education and training services”. However, under European Union (EU) rules, the Greek government is obliged to grant full recognition to the qualifications undertaken at the Greek outposts on branch campuses of EU countries7. Some private colleges have gained recognition for their work by establishing arrangements with universities in other EU countries under which they offer the other university’s qualification (Tovima, 2015[25]). One (evidently thriving) private higher education institution, the American College of Greece (ACG), offers some degrees accredited by a US authority as well as others offered in co-operation with EU institutions.

Under the present Greek law, qualifications granted by the ACG and accredited in the United States are not recognised. This means that their degrees are not recognised if a graduate applies to join the public service. Someone whose four-year bachelor degree is from ACG but who also has a two-year master’s degree from a Greek public institution is treated under the government qualification recognition rules as having two years of post-secondary education – given that the four years of study at ACG is not counted. Such a person, applying for a position in the Greek public service, would be ranked lower than someone with a four-year bachelor’s degree from a public institution. However, someone who followed exactly the same path, but earned an equivalent four-year bachelor degree abroad in the United States would be treated as having six years of post-secondary education when applying to join the Greek public service.

Participation in higher education

Participation in higher education in Greece increased sharply between the late 1990s and the middle of the following decade and then stabilised (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]). Table 5.1 shows that university enrolments increased by 9% between 2002/03 and 2014/15, while TEI enrolments fell by 20%. The number of students enrolled at master’s and doctoral level more than doubled over that time. And the proportion of the 18-19 year-old population enrolled in higher education rose from around 26% to 34%8.

Completion rates

Because of the intense competition for places in the most popular programmes and the inability of HEIs to move resources in line with student and labour market demand, some students end up following programmes that they are less interested in and potentially less motivated for; this point is discussed more fully in Section 5.2.2.

One effect is that completion rates are low (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]; OECD, 2011[26]) and the time taken to complete a qualification is relatively long, with the majority of students unable to complete within the minimum time for their qualification plus two years. In 2014/15, of all undergraduate higher education students in Greece, 54% were in the eleventh semester or more of an eight-semester qualification, up from 37% in 2002/03 (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]).

International linkages

As noted above, significant numbers of Greek students go abroad for their studies in response to the rationing of places in the Greek public higher education system and in order to advance their career prospects (Tsakloglou and Cholezas, 2005[21]). The OECD review team was given examples of strong connections between Greek institutions and institutions abroad. TEIs have only relatively recently earned the right to offer their own master-level degrees; before that, they sought relationships with other higher education institutions in other European countries and offered teaching toward their partner institution’s degrees.

The OECD review team was informed that now that TEIs have the right to offer master degrees in their own name, they have maintained many of those relationships with their partners abroad. In some cases, these TEIs now offer joint master-level degrees with European university partners.

Fuelling the international focus of Greek higher education institutions is the Erasmus + EU programme. The OECD review team observed instances of vibrant and highly active exchanges under the auspices of Erasmus, with good numbers of inbound and outbound students, to mutual advantage.

The OECD review team was informed of cases where foreign institutions have sought to offer joint degrees with Greek institutions in order to enable their students to study Greek history and culture.

Resourcing higher education

The OECD review team was told that HEI revenue comprises multiple elements. Salaries of permanent staff are paid directly to the staff members by the Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs (MofERRA) without passing through the institution’s accounts. The government provides funding directly to the institutions in several distinct streams:

an operating budget

a grant for meals for students

a grant for salaries for adjunct staff

a capital grant through the public investments framework

programmes funded through the EU structural and investment funds.

In addition, institutions raise funding directly through their own efforts:

competitive research funding and consulting (including through funds administered by the European Commission and corporations)

postgraduate student fees.

The OECD review team was told that the Ministry’s funding is determined by an algorithm that includes elements such as: the number of students, a weighting for the cost of delivery of the field of study, personnel costs and the level of study. There are also adjustments for the number of sites at which the institution operates.

Infrastructure funding and operating funding have been reduced as a result of the economic crisis. According to Stamelos and Kavasakalis (2017[27]), funding was cut by around 11% during 2014, following a 24% reduction in the preceding year. The European University Association’s analysis shows the public funding for Greek universities declined more sharply than in any other European country9 (European University Association, 2016[28]).

One institution reported to the OECD review team that, between 2010 and 2017, the amount paid in salaries directly to staff by the MofERRA was held stable while the total funding paid to the institution dropped by 37%.

Reductions to the base research funding were offset by an increase in research programme funding (that is, funding for approved research projects) (see Section 5.1.5). However, many universities and TEIs have been able to shield their budgets to a considerable extent through revenue from research contracts (from European Union funds, businesses, philanthropists etc.) and through revenue from fees for master degrees.

5.1.4. Working with the labour market

HEIs report that they support graduates’ transition to the labour market through job fairs and careers advice. Some HEIs offer internship programmes to help students transition to the workforce following graduation.

Given their vocational focus, Technological Educational Institutions (TEIs) state that they have a focus on the needs of industry. However, the OECD review team found no examples of universities prepared to build strategic, long-term relationships with employer/ industry groups.

As shown in Figure 5.2, young graduates in Greece have the highest unemployment rate among OECD European countries and the second lowest rate of employment (OECD, 2017[1]). Criticism of a lack of a systematic or strategic focus of Greek universities on the labour market is widespread (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]; Livanos, 2007[29]; Livanos I., 2010[30]; Liagouras, Protogerou and Caloghirou, 2003[31]; Mitrakos, Tsakloglou and Cholezas I, 2010[16]; OECD, 2011[26]). Graduate unemployment has more than doubled since the economic crisis, rising from 7% in 2009 to 18% in 2016 (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]). Graduates of disciplines that have high levels of private sector employment, such as computer science and engineering, fare reasonably well in the labour market while those who have graduated in fields that typically lead to employment in the public sector (for instance, the social sciences and humanities) faced poor employment prospects even before the economic crisis. The time taken for a graduate in Greece to get a job is long except for high-demand disciplines like medicine, law and computer science (Liagouras, Protogerou and Caloghirou, 2003[31]; Livanos I., 2010[30]).

The very difficult financial climate in Greece since the onset of the crisis and the consequent freeze on public sector recruitment has compounded the problem of graduate unemployment. It is to be expected that graduate unemployment would rise if there were fewer jobs. However, even before the downturn, graduate employment rates were lower in Greece than in other European countries; many of the papers cited above draw their data from the relatively expansionist time before the crisis.

In response to poor employment prospects for young people, the government formed the National Council for the Education and Development of Human Resources (EΣEKAAΔ or ESEKAAD, established under law 4452/2017), replacing the former National Council of Education, with the role of advising government on education policy, employment promotion and the link between education and the labour market (Esos, 2017[32]). ESEKAAD includes representatives of business, research and professional organisations. It aims to sponsor research into the relationship between the education system and the labour market, including skill mismatches. It is promoting the creation of two-year vocational qualifications, provided for in the 2017 higher education law and designed to address areas of skill shortage. ESEKAAD has plans to initiate projects intended to support student mobility in the tertiary education system and it aims to work with the lifelong learning centres at higher education institutions.

With their vocational focus and their strategic relationships with industry, TEIs see this emphasis on employment promotion as creating opportunities for themselves. The OECD review team was told that TEIs aim to develop new two-year vocational qualifications with a view to offering some from the 2018/19 year. The OECD review team learned during its review visit that some TEIs are building on their existing strong relationships with industry groups to seek input into the design of these qualifications. The OECD review team was also told that TEIs consider that offering two-year vocational qualifications in institutions that also have a higher education mission will lend prestige to those qualifications, meaning that they expect to create demand among students and families for this path.

While it is too early to comment on their likely effectiveness, these measures reflect government’s awareness that the system has been too inwardly focused in the past and needs to direct more of its attention to the Greek labour market. The mission of ESEKAAD signals the government’s resolve to address that problem.

5.1.5. Research funding and performance

University research performance in Greece is reasonably good. Universities are responsible for the majority (~80%) of Greece’s research output and research citations, while the research profile of TEIs is growing (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]; Sachini et al., 2015[33]). Several universities10 appear in many of the main world university rankings systems (which have a focus on measures of research performance).

During the economic crisis, the government reduced core research funding to universities but compensated by increasing the research programme funding through the National Strategic Reference Framework (which takes greater account of the strategic or economic value of the research it funds), meaning that, in total, government funding of research in higher education rose slightly between 2011 and 2013, when the downturn was at its height. Research funding from overseas funders fell by around 4% over that time. Likewise, domestic business funding for universities’ research fell during the crisis (National Documentation Centre (EKT), 2015[34]).

In 2016, the government made a strategic investment in science and research, through the creation of the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (HFRI) as a funding and evaluation agency for investigator-led research, for post-doctoral fellowships and doctoral scholarships11. The HFRI is funded through the government’s budget and through loans from the European Investment Bank.

This means that the Greek government now has a four-tier research funding system:

capability funding through the core funding for universities and research institutes

blue skies research funded through the new HFRI

research programme funding on applied topics of strategic importance to Greece mainly through the National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF) and with some additional project funding from other government budgets and from municipalities

support for the acceleration of the commercialisation of research through government equity investment funds and low interest loans.

Under this funding framework, the government’s share of the funding of research declines as a project matures and approaches transfer and commercialisation stages, and as risk reduces.

These funding streams are complemented by funds from the State Scholarships Foundation (IKY) established to offer grants for postgraduate study, both in Greece and abroad. IKY also funds post-doctoral research fellowships and provides grants for students undertaking research degrees.

As part of the National Social Dialogue on Education over 2015/16, the Greek government looked at the opportunities to strengthen the research system in the regions. This led to the provision in the 2017 higher education law for Academic Councils for Higher Education and Research (ASAEE) designed to bring HEIs and research institutes closer. The purpose is to lift research quality in Greece’s regions and to address problems such as:

the geographic isolation of research groups

a lack of critical mass of researchers in regions

low commercialisation of research results (Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs, 2016[35]).

These councils are expected to produce two-year strategic plans for higher education and research in the regions that seek to increase co-operation between HEIs and research centres, to look for efficiency gains through rationalisation and resource sharing, and to strengthen linkages with regional development priorities.

With the private sector having significantly increased its expenditure on research and development – by more than 50% between 2014 and 2016 (National Documentation Centre (EKT), 2017[36]) – and with the government having maintained its research investment, expenditure on research and development in Greece reached almost 1% of GDP in 2016 (National Documentation Centre (EKT), 2017[36]). While that is well up from 0.7% in 2008, it is below the level in most other European countries; the mean for European countries was more than 2% in 2013-2015 (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]; National Documentation Centre (EKT), 2015[34]).

While Greek higher education research output has been growing, research commercialisation has not kept pace. In its 2017 report on trends in and the performance of the higher education sector, IOBE cites evidence that the Greek universities lag behind other European university systems in measures of commercialisation, such as patents and the ability to attract venture capital finance for spin-offs from research activities (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]). The government will need to monitor these trends as the new acceleration funding system becomes established.

5.1.6. Quality assurance in Greek higher education

The Hellenic Quality Assurance and Accreditation Agency (ADIP) was established under the Greek law 3374/2005 to oversee issues of quality in higher education. The impetus for the creation of ADIP was to enable the Greek higher education system to engage with the Bologna process (Papadimitriou, 2011[37]). The creation of ADIP was controversial, with trade unions and student unions having objected to an institutionalised approach to quality evaluation (Dimitropoulos and Kindi, 2017[38]; Stamelos and Kavasakalis, 2017[27]). The opposition from faculty members and their unions derived from the widely held mistrust of the state, and from anxiety that they would lose authority in educational matters. Students feared that assessments might lead to higher workloads. Students were also concerned that a negative quality assurance assessment could lead to a devaluation of their qualifications (Dimitropoulos and Kindi, 2017[38]).

ADIP became an affiliate of the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA) in 2007. Following an external review of its operations, ADIP was granted full membership of ENQA in 2015 (Stamelos and Kavasakalis, 2017[27]). The ADIP is an independent body, governed by its own board and overseen by the MofERRA. Its role is “…to develop and implement a unified quality assurance system as a reference system for the achievements and the work done by Higher Education Institutions. The [ADIP] should also collect and codify the crucial information that will guide the State in effectively strengthening higher education in the country…in order to ensure the confidence of Greek society in the national system of higher education” (Hellenic Quality Assurance and Accreditation Agency (ADIP), 2007[39]). ADIP’s website12 states that its purpose “…is to promote within the country’s higher education institutes its guidelines for the procedure of evaluation as well as to oversee, co-ordinate and support all evaluation procedures in higher education institutes… [and] to develop and implement a unified quality assurance system, as a reference point for the achievements and work for the Higher Education Institutions”.

The ADIP website states that: “…each higher education institution is responsible for ensuring continuous improvement of the quality of teaching and research work, and for the efficiency of performance of services in accordance with international practices, in particular those of the European Higher Education Area”. Under law 3374/2005, each institution must establish its own academic quality unit while ADIP conducts external evaluations of an institution’s quality.

The ADIP process is:

to require the institution to set up each year an internal evaluation group to conduct an internal quality report that collates data on the indicators that ADIP specifies

to require the institution to undertake a complete internal evaluation every four years

for an ADIP team to meet the institution to discuss and clarify the internal evaluation

for ADIP to convene a committee of independent experts, some from overseas, to conduct the external evaluation

for the independent experts to conduct a critical analysis and evaluation of the internal review report (Hellenic Quality Assurance and Accreditation Agency (ADIP), 2007[39]; Stamelos and Kavasakalis, 2017[27]).

ADIP states that “… the purpose of the external evaluation procedure is to determine the completeness, transparency and objectivity of the internal evaluation [and] its documentary data and … [to form an] opinion …:

to point out good practices and areas for improvement

to highlight and provide documented support for the logical requests of the Unit made at the level of the Institution or the State

to collect and promote the best practices nationwide”.

The internal evaluation report is expected to cover:

“the achievements of the [internal quality assurance unit]

the areas for improvement or corrective actions

the effectiveness of the actions already taken by the unit in order to assure and improve the quality of the work performed, and

…the adherence of the unit to its mission and objectives”.

The internal evaluation group collects information from staff and students. It also assesses performance against indicators such as student-staff ratios, dropout rates, progression rates and the ratio of graduates to new students (Stamelos and Kavasakalis, 2017[27]).

Under the new consolidated higher education law (4485/2017), the government has introduced new evaluation procedures for postgraduate programmes that will complement the ADIP processes.

5.2. Policy issues

5.2.1. Governance of the system

Governance encompasses the structures, relationships and processes through which policies are set and decisions are made (OECD, 2008[40]). Governance sets the basis for the system to operate. At a system level, governance refers to how the system is steered, managed, regulated and organised.

There is a need to build consensus on a vision for tertiary education

The Greek higher education system has been undergoing great change. As noted above, a new law (4485/2017) restructured the regulatory basis of the system, consolidating most of the higher education law and adding a range of new measures. That law replaced an earlier 2011 law that introduced institutional councils, including external members, as a means of establishing a new approach to governance and accountability. Both laws have proved controversial; institutional leaders advised the OECD review team that they considered that both laws had major shortcomings.

While law 4485/2017 followed extensive sector consultation, there appears to be little consensus on the best approach for the Greek higher education system as it works to manage its way out of the constraints that followed the prolonged economic crisis. In addition to that lack of strategic consensus, the public acceptance of the government’s reforms of the higher education sector is affected by:

the highly detailed and technical character of the Greek legislative style

the frequency of legislative change (see Chapter 1, and in particular, Table 1.6)

the fact that it is difficult to get an objective understanding of the performance of the sector in the absence of authoritative and readily available data on the sector.

Recent policy making on tertiary education in Greece thus, has the appearance of lacking coherence. The practice of making frequent amendments to legislation in response to emerging problems risks unforeseen consequences, with the effect of one measure nullifying the intent of another (OECD, 2008[40]). In addition, frequent technical changes to the law make it hard for institutional leaders to interpret and implement policy, leading to further uncertainty.

In these circumstances, there is a case for the government to work with the sector to develop a set of strategic principles to underpin its policy making, in an effort to win consensus on a vision for the system. A shared vision could define the purpose of the system and create a balance between the various roles tertiary education plays – of supporting students to build careers, supporting the economy by supplying skills to the labour market, contributing to the research and innovation system, and contributing to social, community and regional development.

This is not to suggest that the Greek government has not taken a strategic approach in its reform work or to addressing the serious challenges facing the system. The National and Social Dialogue on Education, held between December 2015 and July 2016, identified a number of significant problems that prompted strategies from the government. In particular, the government has created the opportunity for regions to explore the consolidation of their higher education and research institutions; it has reviewed and restructured research funding; it has developed plans aimed at making higher education more focused on economic and labour market needs.

While those are important initiatives, the OECD review team considers there is a need for a strategy that will take a forward-looking view of the whole system. There is a need to identify long-term and medium-term priorities, incorporating some of the important initiatives taken to date.

Higher education in the context of the Greek public sector culture

Under the current governance arrangements, higher education institutions (HEIs) are seen in Greek law as part of the administrative pyramid (see Chapter 2) and their tenured staff are designated as public servants. The place of HEIs as branches of government means that their financial and human resource decision-making rights follow those of government departments. As a consequence, even relatively minor decisions require ratification by central government. That level of centralisation of authority leads to problems of confused and weak accountability (Dimitropoulos and Kindi, 2017[38]).

Currently, in HEIs – as in all of the Greek public sector – accountability is guaranteed by controls on decision making and on finances, rather than from clear decision making parameters and delegations coupled with after the fact accountability, as is typical in countries that have followed a modern public management model (Hood and Dixon, 2015[41]; OECD, 2008[40]). The consequence is that HEI decision making can require a protracted approval process and negotiations between HEI leadership and ministry officials.

It is obvious that public finances and other aspects of the operation of HEIs must be managed with integrity and prudence and without favouritism. However, sector leaders told the OECD review team that they consider the current requirements carry high transaction costs and lead to delays in decision making.

HEIs’ decision-making powers and accountability requirements should reflect the size of institutions, the complexity of their mission and the demands of competing for funding in an international and highly competitive research funding market. Requiring these institutions to follow the same procedures and processes as all government agencies is limiting. The challenge is to move to greater autonomy of decision making, coupled with a rigorous regime of accountability for the integrity of the decision making. However, given that data on higher education are patchy and often difficult to locate, and that performance information on Greek higher education and Greek HEIs is often poor, a shift to accountability based on actual results would need to be accompanied by an improvement to the overall quality and quantity of data on the system.

5.2.2. Governance in institutions

The operating environment

The fact that HEIs are seen as an integral part of central government means that the most important strategic aspects of the management of an institution – its financial, staffing and academic decisions – are either made or ratified by the MofERRA, rather than by the rector, as chief executive and academic leader of the institution. This is a problem of long standing; the 2017 law didn’t alter the roles of the ministry and institutions with respect to decision making.

Funding is provided in distinct revenue lines. Salaries are paid directly to employees by the government, rather than through the employing HEI, while capital and infrastructure funding is provided through a separate funding stream. Institutions also receive a separate operating grant that they administer. The separation of these revenue lines makes it very difficult for HEI rectors to make strategic trade-offs – such as reducing personnel expenditure and transferring the savings to operating budgets or conversely. This closes off opportunities for rectors to make strategic decisions.

It also means that a rector is not responsible or accountable for the whole of his or her institution’s budget.

As a result:

Rectors can’t shift staff resourcing into fields of study where student demand is high and away from areas where demand is weak.

Rectors report that they are often required to operate as negotiators with MofERRA officials, not as chief executives, as they try to have their recommendations ratified.

Final decisions are made remote from the issues being decided. They are made by people without a direct understanding of the trade-offs being made and who won’t have to experience the impacts of those decisions.

As a consequence of the above, accountability is diffuse and confused. Decision making appears less transparent.

With limited powers of decision making in matters of financial and human resources, rectors cannot take a strategic approach to their leadership role. This creates the risk that institutional managers will adopt short-term, tactical decisions. If rectors see their role as negotiators rather than as strategic leaders, there are risks that institutions may miss opportunities for long-term development, and won’t perform to their full potential.

Academic decision making is centralised

Academic decisions (for instance, on new programmes, on programme changes and on admissions to the institution) are made at the Ministry, not by institutional managers.

Students who want to undertake higher education apply to the Ministry, specifying the programmes they are interested in studying, in order of their preference. The Ministry then assigns each student to a department on the basis of their performance in the Panhellenic entrance examinations, taking account of the students’ preferences. Because of the inability of institutions to shift resources to areas of high demand, there are limited places available in many programmes. This means that some students end up studying in fields they may not be interested in and in institutions they may not want to attend (and hence, they are less likely to succeed). Institutions are obliged to take the students that the Ministry allocates to them.

In allocating institutional places to students, the Ministry is making a key academic decision on behalf of institutions. Because some students are taking programmes that don’t necessarily interest them, institutions reported to the OECD review team that teacher education, of particular interest for this review, faces a bimodal distribution – with a good number of highly motivated and well-prepared students, balanced by others with weak motivation and scarcely adequate preparation. Coupled with this, there is no student performance element13 in the current funding system.

These features weaken incentives on institutions to work on improving student performance and contribute to three important problems that have been identified by commentators on the Greek higher education system:

As noted in Section 5.1.3, completion rates are low, with graduation rates in 2007 less than half the OECD average (OECD, 2011[26]; OECD, 2014[42]). The time to completion is slow, with the majority of students unable to complete a four-year bachelor’s degree in less than six years (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2])14.

As described in Section 5.1.4, there is a disconnect between the supply of graduates and labour market demand (Liagouras, Protogerou and Caloghirou, 2003[31]) and unemployment among graduates is high (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]; Livanos, 2007[29]; Livanos, 2010[43]; Liagouras, Protogerou and Caloghirou, 2003[31]; Mitrakos, Tsakloglou and Cholezas I, 2010[16]; OECD, 2011[26]), while employment rates of recent graduates are very low – in 2015, 32 percentage points below the EU-28 average (European Commission, 2016[44]).

The time taken to get a job for a graduate in Greece is long. Even before the crisis and the significant increase in unemployment, it took an average of 20 months for a graduate to find employment and for graduates in some fields (such as librarianship, sports, applied arts and humanities) even longer (Livanos, 2010[43]).

This combination of factors, plus the rigidity of the employment arrangements for academics (see Section 5.2.1) makes it difficult for the system to adjust in response to changes in the labour market and to student demand.

Managing staff

Staff performance management is weakened by the fact that rectors, deans and heads of schools and departments have limited power to reward good performance or to sanction poor performance. The OECD review team was told that managers are able to recognise good performance through promotion across “hard bars” in the career structure – for instance, promotion from associate professor to full professor – and through assigning additional tasks that lend prestige to high performers. But most institutions appear not to have regular evaluations of the performance of individual staff. Outside of the hard bars in the promotion system through the career structure, there are no opportunities to sanction poor performance. In addition, there is no mandatory system for student evaluation of the quality of teaching.

Strategic decision making

The policy of integrating HEIs into the core public service, of applying the same rights of financial, and personnel decision making to HEIs as to core government departments and of giving the Ministry (rather than the institutions) the right to assign students to programmes has the effect of undermining the opportunities for strategic management. It encourages short-term planning. It confuses lines of accountability, leading to unpredictable results. This means that the government is often forced to address problems through legislation.

5.2.3. Funding tertiary education

Institutions have faced a difficult funding environment

As noted in Section 5.1.3 above, funding levels have been cut substantially in Greece in the last six years as the government has struggled to address its economic difficulties. In its Public Funding Observatory report for 2016, the European University Association (EUA) included Greece as one of six European countries whose higher education systems were “in danger” as a result of funding cuts (European University Association, 2016[28]). Commenting on the period 2008 to 2015, the EUA noted that student numbers in Greek universities had risen by 15% while operating funding had fallen by 60%15. Higher education funding fell as a proportion of the Greek GDP (European University Association, 2015[15]), even as the Greek GDP was declining. The reduction in real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) terms was even more severe (European University Association, 2015[15]).

Institutions, and universities in particular, have managed to offset these losses to a significant extent by performing well in winning research contracts and in generating demand for fee-paying master-level degrees. However, the severity of the cuts meant that there has been a freeze on recruitment of staff, while the Ministry continued to allocate a large number of places to new students. The increased enrolment on the back of less funding has increased the pressure on institutions and their teaching staff.

The new higher education law (4485/2017) places new controls on who teaches in master degree programmes and the balance between their teaching at master and bachelor levels, and will restrict the level of fees that may be charged. Fees will need to be set so that 70% of the amount is to cover the marginal costs of the programme. As a result, no more than 30% can offset the difference between the full and marginal cost. This means that the revenue from master’s degree fees will be unlikely to cover the full cost of mounting those qualifications16. This measure risks cutting one of the few sources of income that institutions can strive to increase and thus, their opportunity to offset the restrictions in other revenue lines.

The OECD review team was told that the purpose of these aspects of the new law was to deal with the problem of institutions taking on excessive teaching loads, leading to some faculty members teaching under contract to several institutions and hence, capturing more than a full-time salary. While fixing those problems was a reasonable intention, the new law goes beyond remedying an anomaly in employment contracts. At a time when they have been facing very tight budget constraints, institutions were showing initiative and commendable entrepreneurship in launching new products that broaden their revenue base and help them remain viable.

The funding of teaching and learning is not based on student demand and is not transparent

Internationally, governments develop funding systems that create incentives for institutions to deliver on the government’s goals (OECD, 2008[40]). For instance, if maintaining or increasing participation is a government priority, then we would expect to see a factor in the funding formula that rewards institutions for enrolling more students. If the commercialisation of research is a priority, a government might grant extra funds to institutions that generate more commercial research contracts.

As noted in Section 5.1.3, the MofERRA uses an algorithm as the basis for determining the operational funding of higher education institutions. However, the detailed operation of that algorithm isn’t widely understood17. As noted above, information given to the OECD review team suggests that the funding for the salaries of teaching staff employed in tenured positions has remained relatively stable while funding for institutions’ operations and infrastructure has dropped. It is not clear what determines the level of salary funding. Given that salaries represent upwards of two-thirds of the total government resourcing of institutions18, there is little transparency of funding. This means that it is hard for institutional managers to determine how the government is using funding to steer the system and hence, how they should adjust their strategies in response.

This suggests that funding is designed primarily to support institutions; it is influenced, but not led, by student demand and isn’t affected by students’ success in completing their qualifications. As a result, there are weak incentives to cater for students’ needs or to support students to complete their qualifications. Given the pressures of a staff recruitment freeze and the bimodal nature of institutions’ student body (referred to in Section 5.2.2 above), the OECD review team was told that the need of poorly prepared students for additional academic support often goes unmet19.

A transparent funding approach, with a clear formula that is linked to government’s strategic objectives, would encourage institutions to deliver on those objectives and would build public and sector confidence in the system through increased accountability.

Funding of research works differently

It was noted in Section 5.1.5 above that the government changed the emphasis of its research funding for higher education institutions between 2011 and 2013. The core, untagged funding was reduced by around EUR 88 million, or 25%. This was offset by an increase of EUR 95 million in other government research funding, mostly through funding through the National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF) for designated research projects (National Documentation Centre (EKT), 2015[34]).

In effect, the government was shifting the funding away from research capability and for investigator-led research and towards projects that would have economic or strategic value for Greece20. That is an example of a strategic decision by government using a transparent change in the funding formula leading to a behaviour change in institutions. The OECD review team was unable to determine a similar example of the use of a change in the approach to teaching and learning funding for a strategic purpose21.

There are inefficiencies in the system

Poor completion rates and protracted time to completion

The protracted time to completion (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]; OECD, 2011[26]) described in Section 5.1.3 above is a sign of inefficiency in the system. The limited environment for decision making and weak accountability don’t provide incentives for rectors to improve efficiency in their institutions by lifting student completion rates.

A reluctance to exploit the potential for efficiencies

In Greece, academic programmes are strongly embedded in departments – students are admitted to a department which controls a programme. Because a department owns a whole programme, the incentive for departmental and faculty managers is to create specialist courses in each programme: the OECD review team was told of cases in which opportunities to use a single course to service multiple programmes (and to create efficiencies) went begging. This led to duplication and also discouraged interdisciplinary programmes. Rectors have only weak incentives to address this sort of inefficiency22.

Free textbooks

Greece is unusual in issuing new free textbooks annually to all undergraduate students and gifting them to students at the end of the academic year. While not an institutional issue, it is inherently wasteful for the system overall. A longer discussion of the free textbook issue is in Chapter 2.

Questions remain about the cost of the current network of provision

Additional questions that have troubled some sector leaders are the number of higher education institutions, their geographical spread and the duplication of teaching, especially in sparsely populated regions. These are complex questions. Greece has wrestled with these problems through the Athina project in the past, but without resolution (European Commission, 2016[45]; Zmas, 2015[46]).

The Athina project was initiated as a result of the 2011 higher education law (4009/2011). It aimed to consolidate the network of higher education institutions and to improve internal efficiency through departmental mergers. It also sought to make universities more innovative, create regional excellence hubs, connect the academic sector with regional development needs and strengthen research by mergers between universities and national research institutes (European Commission, 2016[45]; Zmas, 2015[46]). The Athina project also aimed to improve the visibility and the rankings of universities (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]). The arguments for the Athina project drew from the success of the Danish experience where 12 universities and a number of research institutes and specialist colleges were consolidated into 9 larger institutions with wide geographical spread (Pruvot, Claeys-Kulik and Estermann, 2015[47]; Zmas, 2015[46]).

Mergers, however, are complex, time-consuming processes with uncertain results23 (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]; Zmas, 2015[46]). The European Commision argues that the Athina project didn’t produce the financial gains targeted, as many of the departments which were consolidated were not in fact operating and existed in name only (European Commission, 2016[45]). Even if the Danish model of mergers produced good results, there was no guarantee that this would translate to success when it was applied to the very different Greek context (Zmas, 2015[46]).

The government established a procedure under the 2017 higher education law (4485/2017) to remap the higher education and research resources of Greece. This procedure creates opportunities for the consolidation, clustering and/or merging of similar departments or of institutions in a region. The new law provides for regional Academic Councils for Higher Education and Research (ASAEE) which will produce plans to increase co-operation between HEIs and research centres and seek efficiency gains through rationalisation while strengthening links to the regional development priorities.

The initiative for consolidation proposals will come from local stakeholders, with plans to be developed by the institutions in a region and agreed by the MofERRA. This new bottom-up approach is likely to mitigate some of the risks that arise in top-down rationalisation plans once a consolidation or merger is agreed on. There is, however, a risk that local interests may mean that some proposals may never get off the ground.

Consolidation of institutions involves a trade-off between the regional development that arises when institutions are embedded within local and regional centres, and the goals of improving quality and efficiency.

Advocates of greater consolidation argue that:

Quality and efficiency are both compromised by the spread of institutions across a wide area. Spreading academic capability over a wide area reduces the critical mass of expertise that is needed to maintain quality and to generate successful research programmes. Multiple campuses constrain opportunities to exploit economies of scale, while also leading to unnecessarily high infrastructure costs, putting further pressure on already constrained funding.

In some countries, rural communities are served by a single campus that consolidates all the higher education in a region. There are other examples – such as the US state of Georgia – where changing demography undermined the viability of the university network, but where a programme of university mergers has led to a sustainable system with teaching delivery dispersed across rural communities.

Mergers can build quality through the creation of “critical mass”, in particular of researchers. In the report on the National Social Dialogue on Education, it was argued that redrawing the boundaries between higher education institutions and research centres would address problems that result from the geographic isolation of research units, the fragmentation and overlap of research, a lack of critical mass and the limited use of research results in the "innovation chain" (Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs, 2016[35]).

This suggests that redrawing the higher education and research landscape around a small number of hubs of excellence, with strong links to the regional economy, with teaching outposts in smaller communities and with the use of new teaching technologies could create larger institutions that combine excellent research and better engagement with the local economy without the elimination of “local” delivery.

Those sceptical of mergers argue that:

Problems of fragmentation of expertise, a lack of critical mass and of the diseconomies of multiple campuses may be mitigated by new communications technologies.

Locating an institution or a campus in a region is, of itself, an economically important decision; a higher education campus can be one of the largest employers in a region and an important contributor to the local economy. One of the benefits of higher education is that, if an institution has an academic profile well-aligned to the economic and social needs of its community, then it can work with and support local industry and with community groups and hence, contribute to the development of the region.

International examples suggest that the potential financial gains of mergers are sometimes not realised. Merging or clustering of institutions carries high opportunity costs as leadership becomes internally focused on the organisation, rather than on the primary mission of the organisation. Unless a merger is well resourced and unless there is wide understanding and acceptance of the rationale, a merger can end up costing a great deal.

The matter of how many institutions a region needs and how the institutions in a region are linked is contentious. The OECD review team is not well placed to evaluate the trade-offs in the Greek situation in detail. However, the difficulties faced by small isolated institutions and the potential gains in quality, efficiency and regional links that could result from a consolidation of regional institutions make a strong case for change.

5.2.4. Comparing institutional governance with other countries

Studies find that Greek higher education institutions have less autonomy than the corresponding institutions in any other OECD countries (Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), 2017[2]; OECD, 2011[26]). In the Universitas 21 ranking of 50 national higher education systems (Universitas 21, 2017[48]), Greece ranks 35th overall. But that ranking is significantly affected by its ranking as 50th out of 50 on the “environment” dimension (which scores countries on their policy process, autonomy in budgets and academic programmes, diversity, competition between institutions and external monitoring of performance). Greece’s score on that measure is substantially lower than that of the next lowest countries (Saudi Arabia and India). On the output measure, which scores systems on their success in delivering research and producing graduates, Greece ranks 29th of the 50 countries.

The Universitas 21 environment measure draws from the European University Association (EUA) analysis of decision-making autonomy in 29 European countries and jurisdictions and which rates systems on organisational, financial, staffing and academic autonomy (Pruvot and Estermann, 2017[49]).

5.2.5. The operation of the quality assurance system

The OECD review team was informed by institutions that their own quality assurance units operate in co-operation with ADIP’s programme of external evaluations. However, some concern was expressed to the OECD review team about the demands on ADIP to conduct external evaluations across the whole of the higher education sector.

Stamelos and Kavasakalis (2017[27]) report that the creation of ADIP and the establishment of institutional quality units and external evaluations of institutions have had many positive effects on institutions and academic units/departments. They note, for instance, that the quality assurance process has encouraged institutions to prepare a vision and a strategy. This has encouraged institutions to strengthen connections with external stakeholders and to support graduates’ career placement. They have developed better internal management systems and controls. Departments have re-thought academic programme design. The practice of student evaluations of teaching has grown.

However, many of the indicators against which institutional quality is measured are not within the control of the institutions – for instance, both components of the student-staff ratio are determined by the MofERRA, rather than by institutional managers and at least part of the cause of high dropout rates is the Greek admissions practices – whereby the Ministry determines which students take each qualification (Dimitropoulos and Kindi, 2017[38]; Stamelos and Kavasakalis, 2017[27]). Dimitropoulos and Kindi (2017[38]) argue that, as a consequence, evaluations are “…often restricted to merely recording the existing state of affairs and the difficult conditions under which universities and faculty operate…”, undermining their rigour and value.

The issue of what aspects of performance are the responsibility of the Ministry, as opposed to the institution, illustrates the problem of diffuse accountability mentioned elsewhere in this chapter – for instance, in Section 5.2.5. There is a risk that institutions may shrug their shoulders and point to the Ministry in the face of poor results on measures such as poor completion rates; this could jeopardise some of the gains made as a result of the quality assurance mechanism.

Dimitropoulos and Kindi (2017[38]) note that “…no systematic research has been carried out to date, to assess the impact of the first round of evaluations in Greek higher education. So it is not known whether higher education institutions have taken advantage of the recommendations made”. Such an assessment of the effectiveness of the quality assurance system would be useful, particularly if it were to include a focus as to whether the system has led to improvements in the effectiveness of academic programmes.

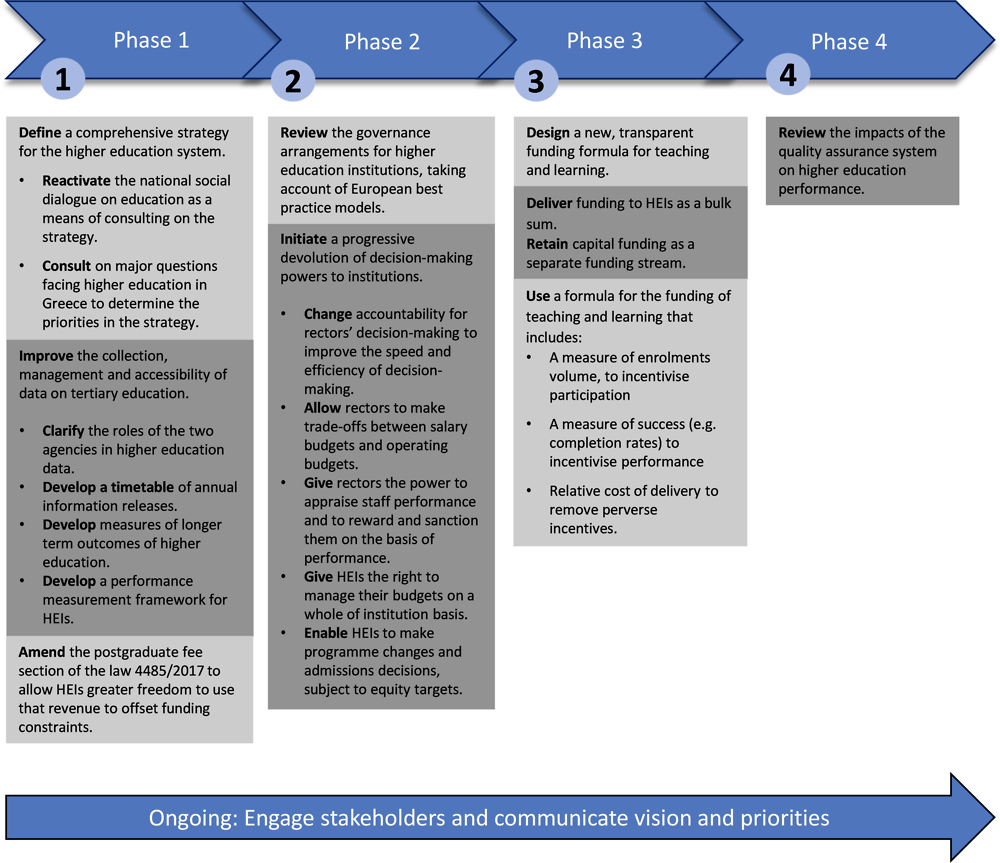

5.3. Policy recommendation: Establish the pre-conditions for tertiary education to be effective

With high participation in higher education, and with relatively low proficiency in literacy, numeracy and problem solving among Greek tertiary graduates, it is important for Greece to re-establish the pre-conditions for the tertiary education system to function effectively and with high quality and performance. To do so, Greece needs to focus on improving the governance of the tertiary education system as a whole and of its institutions. A progressive approach to providing greater autonomy to institutions, improving the alignment between the funding system and the government’s strategy for higher education, and counterbalancing increased autonomy with greater accountability for outcomes is needed.

The following policy options can contribute to achieving this:

Progressively increasing the autonomy of HEIs in organisational, financial and scientific terms, including revisiting the role and composition of the governing body, in order to:

enhance financial accountability in university governance

increase flexibility

promote internationalisation

facilitate change and adjustment and improve responsiveness to future needs of the economy.

Alternative sources of resourcing for institutions should be examined, including:

the role of tuition fees in graduate education

reducing/eliminating costly or redundant services in relation to increasing resources and providing essential new services.

Quality assurance and more effective accreditation by the Hellenic Quality Assurance and Accreditation Agency (ADIP) can be improved.

Dropout rates in HEIs can be reduced.

The current network of HEIs, including mergers between universities and TEIs in line with a smart specialisation strategy and regional development needs can be revisited.

Internationalisation Greek higher education and its attractiveness for cross-border mobility of students and academia, using EU qualifications frameworks can be addressed.

5.3.1. Improve the governance of the system and of institutions

A shared vision on the purposes of higher education and strategic principles to underpin policy making can support greater coherence and balance across the sector. Reliable data on institutional performance will be important for monitoring progress toward the vision, and for improving transparency of the system. In addition, a review of the governance arrangement of HEIs and of European best practice can help clarify the most appropriate structures and roles and responsibilities of governing bodies in the Greek context.

The Ministry has proposed greater autonomy for HEIs. A progressive shift of powers from the central government to institutions may take time. Capacity for strategic and timely decision making, including decisions related to academic offer, and effective performance management will need to be further developed.

Define the vision and set a strategy for Greek higher education

As noted above, system-level governance relates to how the system is steered, managed, regulated and organised. It deals with the relationships between government agencies and institutions, the policy process and the rights of the actors to make decisions. Governance sets the ground rules on which the system actors operate (OECD, 2008[40]).

Given the concerns about system governance that the OECD review team encountered, there is a need for greater clarity of the vision for higher education and for that vision and mission to be enduring, so as to avoid dramatic shifts with the political cycle. Establishing and disseminating a strategy for a tertiary education system is part of any government’s role; the government sets national system goals, defines the operating rules and establishes a regulatory framework that enables system actors to perform effectively (OECD, 2008[40]).

One option that Greece might take to address the concerns about system governance is to develop a consolidated statement of its strategy for higher education. Such a strategy also provides a vehicle for addressing a number of the other issues of system design that Greece currently faces.

Many OECD countries devise statements of strategic aims for tertiary education that provide goals, priorities and plans that help the government to “steer the system” towards the desired outcomes (rather than to rely exclusively on legislation or regulation to direct the sector) (OECD, 2008[40]). A number of European countries have adopted this approach with a view to strengthening the performance of their national higher education systems (refer to Box 5.1 for descriptions of the approach taken in Ireland, France and Romania). Steering a system through a strategy enables a government to grant greater autonomy to institutions, confident that they will work on the enduring system goals and the priorities that have been set.

Tertiary education strategies typically identify a time period and then set out:

a statement of vision and/or mission statement that defines the purpose the country sees for tertiary education and sets out the government’s aspirations for the system

a status report that identifies where the system is strong and as well as its challenges, its opportunities and strengths

the longer term strategic goals for the system

the medium-term priorities and actions

an indication of how the public will know whether the system is on track as it works towards those priorities – i.e. an explanation of the approach to monitoring over the life of the strategy (McCarthy, 2017[50]).

Box 5.1 sets out how three European countries have set their strategies.

Box 5.1. National higher education strategies: Three European examples

In 2011, Ireland set its national strategy for higher education to 2030. The strategy defines the context for a national strategy for higher education – looking at how higher education needs to change to meet new economic, social and cultural challenges and the expanding demand. It explores the mission of higher education in Ireland, looking at teaching and learning, research, engagement with wider society, and internationalisation. The strategy examines recent structural reforms – to governance, funding and structural arrangements – to ensure that the system can continue to deliver on its mission.

The strategy includes a set of high-level objectives together with a number of action areas (Department of Education and Skills, Ireland, 2011[51]).

In Romania, the National Tertiary Education Strategy 2015-20 aims to improve tertiary education attainment, quality, and efficiency, and to make higher education more relevant to labour market needs and more accessible to disadvantaged groups (European Commission, 2016[52]). It identifies needs and constraints and sets priorities that ensure the education system drives a knowledge-based economy.

The strategy contains three “pillars”: