This chapter addresses the extent to which current education governance and financing systems in Greece can fulfil their strategic, managerial and pedagogical objectives. Unnecessary bureaucratic burdens, delays and competency conflicts are ongoing challenges. The first section of the chapter reviews the context of education governance and finance, focusing on the features that are unique to Greece. These include the position of education, within the “administrative pyramid” which also defines the structure of the Greek public sector overall, and the near universal enrolment of secondary school students in shadow education institutions. The chapter then examines those areas of governance and finance in Greek education which are the most challenging. The final section sets out recommendations on how to address these issues and a possible sequence for introducing these reforms over time.

Education for a Bright Future in Greece

Chapter 2. Streamlining the governance and financing of Greek education

Abstract

This chapter addresses the extent to which current governance and financing systems in Greek education can underpin and support educational quality. Education systems need sound governance and effective financing. Sound governance should allow each administrative level to focus on its specific functions, whether strategic, managerial or pedagogical preventing bureaucratic burdens or delays, or competency conflicts. Effective financing should allow limited resources to be directed to those areas of the education system where they can be used most effectively, preventing waste of public resources. Effective financing mechanisms need to be aligned and subordinate to governance structures, so that they can support overall system improvements.

2.1. Governance and funding of Greek school education

2.1.1. The administrative pyramid shapes overall educational provision

The "administrative pyramid" is the term Greeks use to describe the specific governance structure of their state. Clearly not restricted to the education sector, the pyramid exerts its influence over all sectors of the government. However, in education its impact is particularly visible, because it directly affects the relationships between teachers (as part of the administrative pyramid) and students. For this reason it deserves a more detailed review.

The Greek Republic is a unified state, in which 13 regions have administrative roles, without locally elected councils and without executive bodies to represent these councils. Instead, the regions, governed by appointed officials, are an extension of the central administration. Regional directorates of education, the district administrations and school units, analogous to the national administration, are staffed by public servants, who occupy “organic positions”. “Substitute teachers”, a specific group of education staff without organic positions, are an exception to this. Permanent public servants with organic positions have secure, life-long public sector employment. They can lose their status only through leaving the public service of their own will (a very rare occurrence), after reaching retirement age, or due to a court verdict. In regard to the latter, a special procedure, conducted by regional level disciplinary commissions, must be carried out. The OECD review team was told that in practice these disciplinary commissions meet very rarely and are considered not to be very effective. Moreover, permanent public servants cannot be transferred to another institution or demoted without their prior consent (Roussakis, 2017[1]).

This permanence of employment makes the career of public school teacher with an organic position very attractive. The only way to obtain an organic position is to succeed in a nationally organised competition. Candidates apply for different types of positions, not for a specific position in a specific institution (for example, in a specific school unit or in a specific city), although they can state their preferred placement. The nationally approved selection criteria are used to rank candidates. If a position of a given type is open, those at the top of the list will be employed. Similarly, those ranked higher in the list are more likely to be offered the position matching their preferences. Thus, public servants are employees of the state, not of specific institutions. Candidate lists are maintained at the central level of the administrative pyramid, and are updated and used to fill vacancies that may appear.

In order to manage the competitions for organic positions, a complex system of criteria is employed to assess and rank each candidate. The candidates are allocated points, which gives rise to a ranking system. The selection criteria (points used for rankings) include ASEP (Supreme Council for Civil Personnel Selection) examination results, academic qualifications, prior work experience, and social criteria. The criteria, which are nationally mandated, are regularly adjusted and changed.

This centralised ranking system, based on objective criteria, if appropriately implemented, may prevent corruption within the system (i.e. the offer of a job or of goods and services in exchange for political support, or “rent-seeking behaviour”). In addition, this system ensures staffing in remote schools in the islands and mountains as new teachers may spend several years teaching in hard-to-staff remote islands while waiting for an organic position to become available elsewhere.

At the same time, due to the level of complexity and lack of transparency, the centralised system may be quite easily misused. Further, even if applied properly, the national competitions do not take into account the specific needs of educational institutions, in either the appointment of school principals or teachers. There are also social and pedagogical drawbacks to this centralised system for teacher deployment. In general, less experienced teachers are assigned to remote and/or disadvantaged schools. In these schools, they may be required to take on more challenging tasks – for example, teaching several different subjects to mixed-age student groups, as well as performing administrative and maintenance tasks for the school. On a personal level, families may endure separation in the hope that in the future, with additional points awarded for their service in the islands, they may be granted a position in an urban school, preferably in Athens.

The school units themselves do not have the option to choose their staff members or to influence the rankings. Each year, school principals may inform appropriate administrative structures of the number and type of teacher vacancies, but they cannot indicate the specific needs of the school unit (such as students coming from different backgrounds). This process does not allow for consideration of the overall balance of teacher competencies within the school, or the balance of more experienced and newer teachers (with more experienced teachers able to mentor their less experienced colleagues).

The central Ministry of Education bears a significant level of the administrative burden, but has a limited role in the budget process

The key element of the centrally run administrative pyramid is the Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs (MofERRA). The institutional structure of the Ministry is well suited to managing the centralised bureaucratic apparatus, as is discussed below. At the same time, high-level officials are replaced with each change of the government or policy. Because of this, the centralised structure is accompanied by regular shifts in policy direction and staff, presenting challenges to the sustainability of the Ministry’s strategic efforts.

The Ministry includes four secretariats-general. The largest one is the Secretariat-General of the Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs, which is responsible for education. The other three cover the remaining areas of responsibility: religion, research and technology, life-long learning, and youth initiatives.

The Secretariat-General of the MofERRA is divided into several directorates-general1:

Strategic Planning

Financial Services

Human Resources

Studies in Primary and Secondary Education

Staff in Primary and Secondary Education

Tertiary Education

Several autonomous directorates.

The role of the Directorate General for Financial Services is limited primarily to the budgeting of the Ministry itself and of institutions which are directly subordinate. No directorate collects or analyses data about overall financial flows and budgetary processes in education. As discussed below, this weakens the ability of the Ministry to effectively steer the education system and to introduce reforms. Similarly, the Directorate General for Staff in Primary and Secondary Education is involved in the oversight of the national competitions for organic positions (developing procedures, setting criteria, and maintaining candidate lists), but not in strategic planning for the needs of school units in different parts of the country and for different groups of teachers. Only recently has the Ministry begun to establish a national database of schools and students (often referred to as “education management information system”).

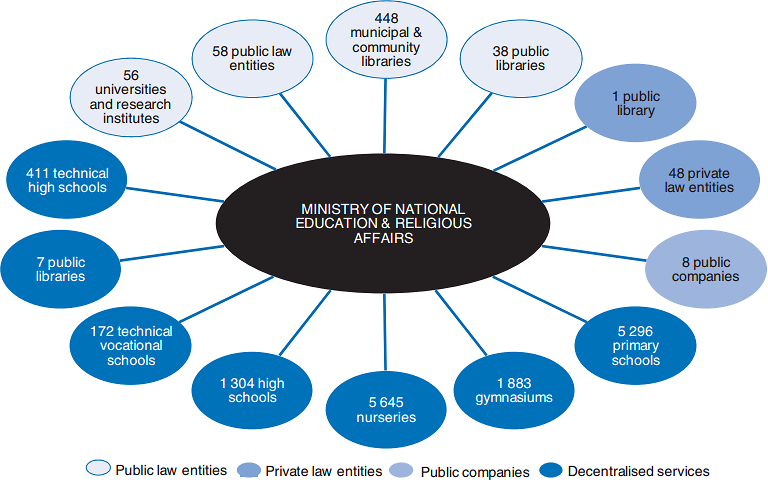

Besides regional and district directorates of education, which are discussed below, the Ministry controls the activities of other institutions, as shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1. Education institutions supervised by the MofERRA

Source: OECD (2011[2]), Greece: Review of the Central Administration, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264102880-en.

Figure 2.1 indicates the high level of administrative and bureaucratic burden placed on the Ministry. It is necessary to add, however, that in the Greek system, this burden is especially heavy, because it includes the obligation to maintain and manage the organic positions of each of the subordinate institutions, including the obligation to conduct national competitions.

In this way, the Ministry is closely involved in staffing and other human resource management responsibilities for primary and secondary education. The main administrative tools to execute this function are the regional and district level directorates of education. At the same time, there is no unit in the Ministry responsible for monitoring of the education process in terms of inputs, processes, and especially of outcomes. Instead, the Ministry relies on its subordinate management structures to make the necessary reports. However, it is well recognised that if different units of the administrative pyramid themselves report on their own activities, the value of the reports is diminished. The absence of independent monitoring mechanisms or institutions limits the ability of the Ministry to strategically manage the education sector.

Regional and district directorates of education support implementation of national education policies

Besides the Ministry itself, the administrative pyramid includes the regional directorates of education (RDE). Ministry sources informed the OECD review team that RDE directors’ selection process has been modified recently to strengthen its validity. They are expected to serve for a defined time period and are selected by a Central Education Council based on the same criteria as all education executives (including academic qualifications, teaching and counselling experience and an interview) (Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs, 2018[3]). RDE staff, like Ministry staff, have organic positions and are appointed through the standard Greek procedures. RDE are deconcentrated services of the Ministry, and operate as a single structure for both primary and secondary education in the 13 Greek regions (Roussakis, 2017[1])2. They implement national education policies at the regional level, based on nationally mandated norms, regulations and procedures. Their responsibilities include administration and scientific and pedagogical guidance of education (Roussakis, 2017[1]). RDE select permanent teachers (teachers with organic positions) and school unit leaders. For all intents and purposes, they are a part of the state-wide administration.

The same is true of state administration extending further down, to the district level. Parallel district directorates of education for primary and secondary education (DDE) operate in all 116 districts or prefectural units (Roussakis, 2017[1]). They are a part of the national administration structure in the same way and sense as RDE, with their staff appointed through an analogous procedure. Interestingly, the Greek Republic has local governments, governed by democratically elected councils with local executive apparatus. However, the DDE are not subordinate to these local councils, but are financed directly by the state, and have very clearly separated functions. Their main role is to implement national education policy, oversee and control the activities of school units as regards compliance with the regulations and with new education policies, manage the allocation of seconded and substitute teachers at the local level, and provide pedagogical support to school units through the services of school advisors.

The structure described here is what is referred to as the administrative pyramid (this is also the terminology used by the Greek officials). The crucial fact is that, besides the Ministry and the regional and district directorates, this pyramid also includes the institutions where teaching and learning take place – the school units. These are examined in Section 0.

Information on the quality and equity of school and student performance is limited

As mentioned above, capacities to monitor education outcomes are limited. The only instrument allowing the Ministry to objectively measure the outcomes of teaching is the Panhellenic examination, taken each year by students at the end of the 12th grade (“lyceum grade C”) and used for the competitive selection process to universities. In particular, students with higher examination scores are able to enrol in better – or more sought-after – universities. However, this exam comes only at the end of the school career of students who want to enter into university. Moreover, the results are not comparable from year to year, and therefore are of limited use to the Ministry in its efforts to improve education quality.

The Panhellenic examination process is highly appreciated by parents and by most education experts met by the OECD review team. It is considered to be objective and reliable, and is the one element of the education system which is universally considered to be invulnerable to corruption. This system ensures that there is limited opportunity for “buying” grades or for illegally paying for admission to tertiary education. However, because this centrally developed and administered examination is used mainly for tertiary education admissions decisions, the stakes for participating students are extremely high. This leads to considerable distortions of teaching and learning in upper secondary schools, and seriously impacts the education system itself. For example, in the final year of upper secondary school, curricula for subjects covered in the Panhellenic are narrowed to focus almost exclusively on content that may be featured on the examination, while teaching of other subjects is reduced. The focus of the examination itself (through the design of test items) is on the acquisition of knowledge (an information reproduction approach) rather than application of that knowledge to address problems in specific contexts (a competency-based approach). This reinforces the rote-learning approach to teaching in upper secondary education, as schools at this level prepare their students to compete.

The process of preparing students for the Panhellenic examination also distorts the overall education system, as families devote a significant portion of their household income to shadow education, or private afternoon schools, which often serve one function only: preparation for this examination (see Section 2.1.5 in this chapter and Chapter 3 for a discussion of shadow education).

Finally, it is important to note that no single test can measure proficiencies in any given domain exhaustively, nor can it fully capture the quality of student capacities; when decisions are based on a single high-stakes tests, some very capable students may not succeed (see Chapter 3 for a discussion of the equity implications of the Panhellenic examination).

The Ministry’s reported proposal to balance the Panhellenic examination with teachers’ assessments may help to alleviate some of these distortions (with the Panhellenic counting for 80% and teachers’ assessments counting for 20% of the score used to rank students for higher education admissions). The implications of this proposal for student equity and teacher capacity building are discussed in Chapter 3 and for school evaluation and student assessment in Chapter 4. Other instruments for monitoring education processes and outcomes, which are equally important for the Ministry to introduce and use are also covered in Chapter 4.

2.1.2. Stakeholder engagement within the administrative pyramid is limited

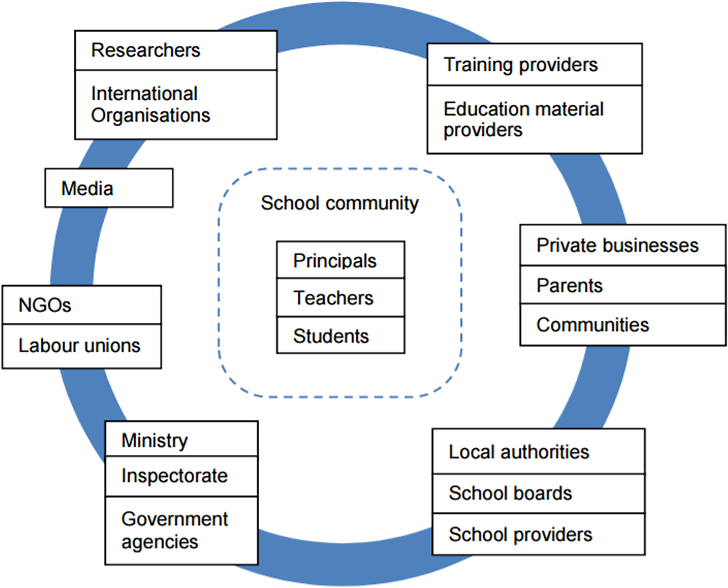

Education is a unique sector of any public administration in that a wide range of actors have their own, very different stakes in education outcomes. They include students, parents, teachers, employers, trade unions, public administrations at different levels, and thus, virtually the entire society. As indicated in Chapter 1, the current level of trust in the education system in Greece, while higher than for some other public institutions, remains low. Stakeholder engagement is an important way to build this trust, and may extend from participation in the work of school units, through co-operation with local governments, through public dialogue at different levels, up to development of an overall vision for education.

Within Greece’s administrative pyramid, however, stakeholders have had limited opportunities for engagement in education policy development at the national level, and even less at the local level. As described above, the governance structures and procedures in Greek education are focused on centralised management of human resources and do not provide channels and procedures for permanent public policy dialogue.

In recognition of this, the MofERRA has recently made efforts to gather stakeholder feedback on proposed policy reforms (Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs, 2017[4]). While initially outreach included forums to support public dialogue, confrontations cut short these efforts. The failure of this ad hoc, but promising initiative is indicative of insufficient levels of trust in the system, or of underlying, unexpressed frustration, which the education governance procedures are unable to address. With the opportunity for direct public dialogue limited, the stakeholders have only the option to respond to reform proposals online, or to share their views in writing with regional or district directors. They may be able to vent their frustration, but do not have a pro-active role in developing a future-oriented vision for education – and for their children.

Another important channel for stakeholder feedback is co-operation with teacher trade unions. They have a unique role to play because they express the needs and aspirations of key education staff. There is institutionalised participation of teacher unions in central (KYSPE, KYSDE) and local Education Administrative Boards (PYSPE, PYSDE) and also in the selection boards of schools directors, which give them an important role in the administration of the Greek education system. However, tense relationships between the Ministry and teacher unions around areas where there is no agreement have stalled productive social dialogue on the way forward. While it is natural that top education administration and teacher trade unions have differing positions and only rarely are able to reach consensus, the exchange of the opposing views is crucial for strategic management of the system. In Greece, the lack of engagement of teacher trade unions in policy dialogue was underlined by their refusal to meet with the OECD review team to present their point of view. The Primary Teachers’ Union (DOE) and the Federation of Secondary School Teachers (OLME) Teachers’ Union have focused much of their attention on teachers’ material working conditions (pensions, taxes, collective bargaining and agreements, and strike action), but have not insisted formally on having the opportunity to co-design policies on addressing problems of equity and exclusion, or of curricula and the textbooks (priorities are highlighted at www.olme.gr and www.doe.gr).

Research has highlighted the importance of engaging public servants in change processes, for example, through social dialogue and surveys on employee engagement (International Labour Organization, 2013[5]; OECD, 2016[6]). Demmke and Moilanen (2012[7]) found a strong relationship between the introduction of austerity measures and particular decreases in job satisfaction, trust in leadership, workplace commitment and loyalty in the European Union (EU) central administrations. On the other hand, employee engagement, is empirically linked to better organisational outcomes, such as efficiency, productivity, public sector innovation, citizen trust in public sector institutions, and employee trust in organisational leadership (OECD, 2016[6]). These findings are directly relevant to Greek education. Social dialogue with teachers and government accountability to ensure their voices are included would go a long way to strengthening trust in the Greek education system. Teachers and families are the most consistent force for change within the Greek education system, and they need to be included throughout in order to ensure ownership and sustainability of reforms. To review the causes of current low level of engagement of teacher trade unions in policy dialogue goes beyond the scope of the present report, but the OECD review team has no doubt that the current state of relations represents an obstacle to further development of Greek education.

2.1.3. School units have low autonomy

Schools are universally referred to in Greece as school units (Σχολική Μονάδα), both legally and in common parlance. This is not a coincidence; the vocabulary of “school units” instead of “schools” indicates low levels of autonomy. School units are not separate institutions, with separate rights and roles, but are fully embedded in the administrative pyramid alongside the Ministry, RDE and DDE. As discussed below, they lack certain characteristics typical of schools in other countries, and are in fact administrative units. It is therefore appropriate for a discussion of the Greek education system to follow the Greek custom and use the terminology of “school units”, not “schools”. Recent policy initiatives indicate that school units may be granted some measure of pedagogical autonomy, but the scope of this is still under discussion (see Chapter 4). According to Ministry sources a number or initiatives to gradually increase autonomy include a thematic week established in 2016-17 in lower secondary schools, in which schools have freedom to design their own activities through teacher collaboration, or a new ministerial decision has established that each school should develop a framework for the organisation of school life at the beginning of the school year, following discussions across the school.

School units in Greece have appointed principals (school leaders), but their responsibilities are extremely limited and focused on administrative issues. The first limitation is that they cannot select their own staff, be they teachers with organic positions or substitute teachers (OECD, 2017[8]). Allowing principals greater input on staffing decisions, or indeed the right to select and employ school unit teachers, would mean that they would be better able to ensure a good fit between the teachers and the students, taking into account the teachers’ competencies and the needs of the student population they will teach, consistent with the backgrounds and cultures of learners and their families. This is particularly important to ensure equitable teacher deployment throughout a school system. Another reason to consider the composition of the school’s teaching team is that no individual teacher is likely to have all the competencies needed to support students to develop 21st century skills. Teachers with complementary competencies may bring more to collaborative work within schools and the school network. The competencies of the overall teacher team of the school therefore need to be considered.

Given the opportunity, principals and teaching staff may find ways to tailor the educational offer of the school units to local needs. However, very limited autonomy of Greek school units, beyond recent efforts to introduce a thematic week makes this very difficult3. The same is true of the ability of principals to engage parents and members of the local community, to use local resources outside of the school unit to enhance the educational process, to raise additional funds, or to engage staff and other members of the school community in developing innovative programmes. Consistent with the low level of school unit autonomy is the fact that principals do not receive any training in ways to successfully engage parents or in entrepreneurial skills.

School principals are currently barred from visiting classes conducted by teachers and from appraising the pedagogical process. This feature of the Greek education system is quite unique, and is contrary to standard OECD practices. It means that principals are not responsible for the pedagogical approach which teachers adopt, and hence also for the results of the teaching in their school unit (OECD/SSAT, 2008[9]). School principals are all teachers themselves, often with many years of practice in schools, and their experience and support could be of much value to other teachers, especially young staff and substitute teachers. Not to use these extremely valuable resources to improve the pedagogical process in school units is counterproductive.

School units do not have clearly defined pedagogical staff, with their teaching work force composed of several distinct groups of staff. Rather, there are two main groups of teachers: those with organic positions in school units (public servants), employed essentially for life, and the substitute teachers, who have short-term contracts (Roussakis, 2017[1]). Moreover, there are often several seconded teachers, that is teachers with an organic position in a different school unit from the school unit in which they were hired and where they maintain a post, or in the DDE, who in the given school unit give only several lessons per week.

School units have no defined budgets. Different budget lines are determined by different ministries and institutions. These include the following four major budget flows (see Section 2.2.3 below for further discussion):

funds for teacher salaries managed by the Ministry of Finance

funds for textbooks managed by the MofERRA through the state agency Diophantos CTI

funds for building maintenance and for technical staff from the municipalities, based on a grant allocated by the Ministry of Internal Affairs

funds for investments from agency K.Y.S.A. under the Ministry of Infrastructure, Transport and Networks.

The different budget lines are set in unrelated processes, are executed by different authorities, are reported separately, and are never put together in a single document, even for comparison. It is impossible to assess how much it costs to run a given school unit, or to compare per student costs in different school units. This indicates that school units are an integral part of the administrative pyramid also in terms of their budget. Further, principals have a very limited role in the budget process, which means that during the determination of next year’s allocations for the school (from multiple sources), they have limited opportunities to formulate specific needs of their school units (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2014[10]).

To summarise the managerial position of school unit principals, they have no role in selection and appointment of their teachers, no role in shaping the pedagogical process in the school unit, and no role in the budget process. Compared with most OECD countries, Greek school units have weak leadership with low levels of autonomy to make decisions.

2.1.4. The economic crisis has had a significant impact on education

Adjustment to the crisis has been painful but successful

The smooth functioning of the administrative pyramid, which oversees the activities of primary and secondary education, was severely interrupted by the deep economic crisis. There were painful adjustments, including a serious decrease of teacher salaries and elimination of seasonal bonuses. In 2016, average teacher salaries amounted to 75% of their levels in 2009. Moreover, administrative support personnel such as secretaries, where provided, were withdrawn from school units, which put more pressure on other staff, especially on principals. However, these adjustments did not interrupt the work of school units. Similarly, despite fiscal constraints the provision of free textbooks to all students continued.

The crisis was most acutely felt in the employment and career advancement opportunities of teachers. The OECD review team was informed that the creation of new organic positions across the public sector was regulated in the Memorandum of Understanding, signed by the Greek government with representatives of the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank. Under the Memorandum there is an attrition rule in place, which specifies the ratio of employees lost due to retirement or having left the public sector, and new hires. The law specifies that this ratio was to be 5:1 in 2016, 4:1 in 2017 and 3:1 for 2018.

The choice of sector where the new organic positions are created is left to the discretion of the Greek authorities. The government decided that education is not a priority sector, and as a result, no new organic positions have been created in Greek education since 2009 (Roussakis, 2017[1]). Effectively, Greece has frozen hiring of new permanent teachers. This clearly gave Greek authorities more freedom to create organic positions in priority sectors, at the expense, however, of satisfying the needs of school units.

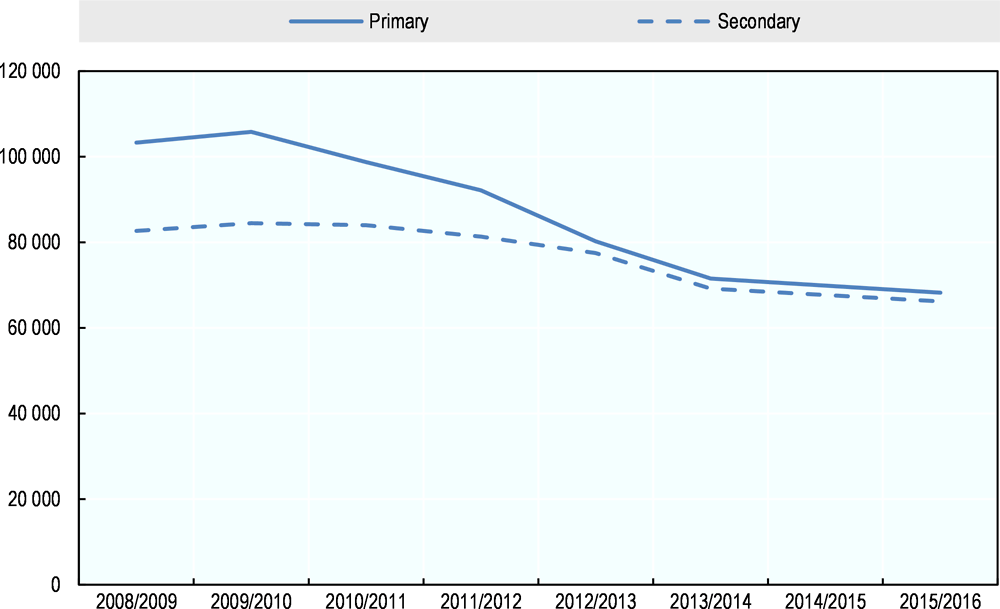

Over time, the natural retirement processes of teaching staff and teachers leaving school units have led to a serious decline of permanent staff in school units. Figure 2.2 presents number of teachers with organic positions in primary and secondary education.

Figure 2.2. Number of permanent teachers by level of education

Source: Roussakis, Y. (2017[1]), OECD Review, Partial Background Report for Greece, Greek Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs.

In the period 2008 to 2015, the number of permanent teachers (public servants) declined by 28%. The decline is particularly severe in primary education (almost 34% reduction in the number of permanent staff). Indeed, since 2009 there has been no new hiring of permanent staff, and therefore no need to conduct national competitions for organic positions, as described above, with the last ASEP examination conducted was in 2009.

To summarise, three factors contributed to the severe problem of understaffing in public school units in Greece: the economic crisis, the limitation on creation of new organic positions, and the strategic choices of the Greek government regarding the sectors where new organic positions will be created.

Substitute teachers have become prevalent in school units

The resolution of the problem of fewer organic positions was quite ingenious, both from an administrative and a financial point of view. The workaround solution involved the use of substitute teachers, in agreement and with the co-operation of the European Commission. The substitute teachers are employed every year for up to ten months of the school year. They do not receive salaries during summer holidays, and after the holidays (and increasingly earlier) may apply for another short-term appointment. Thus, from a macroeconomic perspective, they do not represent an additional long-term liability to the national budget. Further, the European Commission has agreed that European Structural Funds may be used to cover the salaries of substitute teachers (formally, these expenditures do not represent salaries, but payment for educational services, which explains why they do not receive salaries during holidays, unlike permanent teachers in Greece or indeed in other EU countries).

Over time, as the pace of permanent teachers leaving their organic positions due to retirement continues, the number of substitute teachers in the sector has grown. Between 2011 and 2015, the number of substitute teachers in primary and secondary education increased from 14 000 to 18 900 – that is, by nearly 35%. In this period, the share of substitute teachers grew from 8% to 14.1% (Roussakis, 2017[1]).

Table 2.1 indicates the percentage of substitute teachers in the teacher workforce for different subsectors of education in the school year 2016/2017. Note that the table provides the number of teachers as physical persons, not as full-time teacher equivalents. This limits the accuracy of analysis, because in terms of their contribution to the work of school units, and the salary received, it is the full-time equivalency which counts. Central and regional education administrations are excluded from the table, because they do not employ substitute teachers. Further, unlike historical data cited above, the table includes preschool teachers as well as decentralised services (these are various professional support services working with students and with school units).

Table 2.1. Substitute teachers in Greek education, 2016/2017

|

Number of all teachers |

Number of substitute teachers |

Share of substitute teachers |

Distribution of substitute teachers |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Preschool |

14 052 |

2 557 |

18.2% |

11.1% |

|

Primary |

66 649 |

12 304 |

18.5% |

53.4% |

|

Lower secondary (Gymnasium) |

37 983 |

4 231 |

11.1% |

18.4% |

|

Upper secondary (Lyceum) |

21 962 |

1 145 |

5.2% |

5.0% |

|

Vocational upper secondary |

13 725 |

1 038 |

7.6% |

4.5% |

|

Specialised vocational |

1 814 |

1 332 |

73.4% |

5.8% |

|

Decentralised services |

1 666 |

434 |

26.1% |

1.9% |

|

Total |

157 851 |

23 041 |

14.6% |

100.0% |

Source: The OECD review team calculations based on statistical data provided by the Greek Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs.

As the table indicates, substitute teachers have become a key feature of Greek education, accounting for nearly 15% of the teacher workforce, and their work in school units is crucial for continued operations of the sector. They are especially prominent in preschool education and in primary education, where they represent over 18% of the regular teaching staff, less so in lower secondary school, and many fewer in general academic and vocational upper secondary schools. The high share of substitute teachers in special vocational school units appears to be an anomaly; this is a very small subsector of education.

The last column of Table 2.1 indicates that substitute teachers are concentrated in primary education (over 53% all substitute teachers) and in lower secondary education (over 18%).

The use of substitute teachers is a short-term solution

It is important to note that the use of substitute teachers under the present legislation is not a good long-term solution. There are two aspects to this problem. The first concerns the functioning of school units. With the teaching workforce composed of two very different groups, it is difficult to achieve team unity and co-operation. Teachers with organic positions enjoy complete job security, knowing that they will be teaching in the same school the following year, while substitute teachers are in a precarious professional situation (see below). And while in school units in affluent areas of large cities substitute teachers are often a small minority, the OECD review team was told that in some provincial school units, especially those located on islands, substitute teachers dominate. Moreover, the use of substitute teachers is associated with constant turnover of a considerable part of the teaching staff. This undermines the basis for planning of teacher in-service training and for introducing new teaching approaches. As a result, the ability of school units to adopt and execute school unit development plans is weakened. The planned introduction of school unit self-evaluation and of some pedagogical autonomy (see Chapter 4) may exacerbate these problems significantly.

The second aspect concerns the professional position and professional perspective of substitute teachers. Their position in the sector is extremely precarious, without any certainty about their employment prospects in the following school year. Even if they find employment in a school unit the following year, which most of them will because of obvious demand for their services, this will very likely be in a different school. This seriously reduces their positive engagement in the school development plans and their motivation to closely co-operate with their students’ parents. Further, not being paid for holiday periods makes their life more of a struggle. Substitute teachers may be therefore reluctant to make investments into their professional development, such as paying for additional courses to obtain new qualifications.

The Ministry understands the negative impact of substitute teachers on the functioning of Greek education. Their main policy response is to stress the underfinancing of the sector, and to postulate a return to unhindered employment of permanent teachers using the traditional mechanisms of the administrative pyramid described above (see Section 2.1). This clearly would dispense of the need for substitute teachers. And indeed, it seems probable that Greek education is underfinanced (see Section 2.2.4). However, given the lack of data, it is not easy to prove that point, or to present a clear picture of regional and social variation of this perceived underfinancing.

Similarly, it is certainly true that a complete freeze of new permanent employment in school units is harmful to education. If the system of organic positions remains in force, what is needed is a transparent and objective system of allocating organic or permanent positions to school units. Therefore, a simple return to pre-crisis approaches is a policy choice that may have negative consequences and would require in-depth discussion.

The Greek education system demonstrated flexibility and creativity in responding to the refugee crisis

The ability of the Greek education system to respond to a sudden and unexpected crisis was very clearly demonstrated when a massive inflow of refugees arrived in Greece in 2010 (Triandafyllidou and Gropas, 2014[11]). Initially, Greece was the main entry point of immigrants, although by 2017 this shifted to Italy (UNHCR, 2017[12]). Most of the immigrants have treated Greece as a stepping stone and continued their precarious journeys further north, through the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) and Serbia.

From the start, there were many school-aged children among the refugees. Even though most families were intent on moving to central and northern EU countries, they often stayed with their children for considerable time in camps organised by the Greek authorities after travel routes out of Greece were blocked to them. This has created a serious challenge for the Greek education system to accommodate immigrant children, who very rarely have any previous knowledge of the Greek language, in local school units.

Remarkably, despite the bureaucratic burden of introducing new policies in Greece and the associated delays, the Greek education system soon began to respond to the challenge. This response occurred during the ongoing severe financial turmoil, which of course limited available resources. With many volunteers at different levels, Greeks managed to accommodate traumatised children, provide them a welcoming secure environment, ensure they could attend school units and begin learning (starting with the learning of Greek language, necessary for communication with other students and for classes). The good will of educators and the resilience of institutions revealed in times of crisis shows that Greek education governance structures have the resources and the capacities to respond both adequately and in a timely manner.

Interestingly and very innovatively, to provide additional necessary pedagogical staff to help immigrant children, Greek education used the system of substitute teachers. To fully use school unit facilities and to avoid potential conflicts, classes for newly arriving migrant students are typically organised in the afternoon, after day students have left the buildings. In many school units, these afternoon lessons have been organised with remarkable success, staffed by enthusiastic and caring substitute teachers. They have had to learn, largely on their own and through improvisation and trial and error, how to approach traumatised children, how to encourage them to attend classes, what pedagogical programme to adopt for their students, and how to adjust for cultural and social differences. In some ways, the allocation of necessary substitute teachers required less time and could be organised more quickly than would be the case for permanent teachers (whose deployment requires complex administrative procedures, and who could not be employed in any case, due to the freeze discussed in Section 2.1.4).

Nevertheless, it is important to point out the inherent dangers of this inventive, ad hoc solution. Recall (Section 2.1.4) that substitute teachers are employed for up to ten months only, and typically are appointed to another school, if they are employed the following school year at all. Moreover, their next year’s employment need not involve working with migrant children, as this type of experience is not a part of standard ranking of candidates for substitute teachers. This creates risk that the experience and knowledge gained in working with migrant students will be lost, and new substitute teachers assigned to these students will need to start learning their new role. The same is true of the personal ties formed in the process between the teacher and the student, which obviously are of great importance when dealing with fragile and traumatised students.

2.1.5. Rates of privately funded shadow education are high

Greek society, for a variety of reasons and for a considerable period of time, has financed the education of its children via both taxes, to pay for public schools, and directly from household budgets, to pay for shadow education. A description of the sector is in Chapter 1, Section 1.3.3. The share of the second financing stream is extremely high by international comparisons and continues to grow. This may be a response to the possible underfinancing of public education (see Chapter 2, section 2.4), or to the perceived weakness of public school units (see Chapter 2, Section 2.3).

Available estimates of household expenditures on private tutoring in Greece are not fully reliable, as they report very different figures. Nevertheless, there is a consensus that they are likely to be the highest in the EU and among the highest in the world. Overall estimates on the amount spent on shadow education in Greece vary between 1% and 2% of GDP (European Commission, 2011[13]). Considerable variation over time has been recorded. It has been estimated that in 2004, on average, Greek households spent more than EUR 10 000 for every child attending shadow education in secondary education in preparation for the university entrance exam (Psacharopoulos and Papakonstantinou, 2005[14]). This would translate to an overall estimated expenditure of EUR 1.1 billion – more than government expenditure on secondary education at the time (Psacharopoulos and Tassoulas, 2004, p. 247[15]). For 2007, it was reported that yearly household expenditures on supplementary education was about EUR 1.7 billion (Liodakis, 2010[16]).

More recent estimates, although in aggregate rather than at household level, would indicate that this diminished as the impact of the crisis took hold. In 2008 for example, the estimates are lower: an estimated EUR 952 million was spent by households on private tutoring, of which EUR 340 million were for individual lessons and EUR 612 million for frontistiria attendance (where per student prices are much lower). This represents over 20% of government expenditures on primary and secondary education in Greece, as well as over 18% of all household expenditures on education (KANEP/GSEE, 2011[17]), (European Commission, 2011[13]). Moreover, households spent an additional EUR 705 million on for private foreign language lessons.

Estimates by the same sources for 2013 are much higher. For 2013, it was estimated that total household expenditures on all private tutoring, including supplementary education, foreign languages, music and digital learning amounted to EUR 3.9 billion. This represented 80% of state budget expenditures on primary and secondary education, and nearly 2% of GDP [KANEP/GSEE (2016[18]), cited in Liodaki and Liodakis (2016[19])]. Expenditures on supplementary education (both frontistiria and individual lessons) represented 75% of this amount. This is a considerable financial burden on families (Kassotakis and Verdis, 2013[20]).

The frontistiria market adjusted to the economic crisis, in parallel to the public education sector (Liodaki and Liodakis, 2016[19]), in part through lowering of fees and adjusted educational offer. A small social frontistiria movement has attempted to provide after-school tutoring for those students who cannot afford even these diminished offerings (Zambeta and Kolofousi, 2014[21])

Based on these data, it can therefore be concluded that private investment in education, primarily in private tutoring, including frontistiria, represents considerable expenditure, comparable with the entire national budget allocation for primary and secondary education. The impact of this on schooling, on equity, and possible policy solutions are discussed in detail in Chapter 3, Section 3.2.5. However, even though frontistiria and private tutoring have important implications for the equity and quality of educational provision (as discussed in Chapter 3), a diversion of even a part of household education expenditures into the public school education system could be challenging and risky.

2.2. Policy issues

As discussed in the previous section, Greek education, like all other sectors in the public sphere, is embedded in a large administrative pyramidal structure. The impact of this rather unique governance model is clearly visible across all levels of education. It seems unlikely that any far-reaching governance and finance reform of Greek education system is feasible without addressing the questions of the administrative pyramid and of the organic positions. These two questions, however, which touch on the fundamental structure of the Greek state, are anchored in the Greek Constitution, and therefore cannot be tackled in a report focused on education.

In the present section, instead, specific policy issues of the current system of education governance and finance in Greece are identified; these issues were chosen because they are directly relevant to the problem of continuing self-improvement of Greek school units and do not raise constitutional issues.

2.2.1. Schools are seen as administrative units

Responsibility for school units is fragmented

Different groups of school unit staff are appointed by different institutions using different criteria. Today, the responsibility for different spheres of activities of school units is fragmented and diffused. Permanent teachers, who are public servants (teachers with organic positions), are selected by a special national-level commission, using national criteria and a credit system. No opinion of principals is required or solicited during the process of allocating successful candidates to individual school units.

The same rules are followed when permanent teachers apply to change the school unit where they teach. From the point of view of the majority of teachers, the most attractive school units are in Athens and Thessaloniki, the least attractive on remote islands and in the mountains. Therefore, if a vacancy in one of the attractive school units appears, many permanent teachers working in remote areas are willing to transfer. In theory, this situation could give school unit leaders in urban areas some ability to structure their workforce according to the needs of students or to the specific teaching programme of the school unit. However, as should be clear from the preceding discussion, current legislation does not allow this.

Seconded permanent teachers and substitute teachers are allocated to school units by service councils, organised in each DDE, using a different system of criteria and credits. The selection of both permanent and temporary teachers is performed without taking into account the needs of specific school units; it is based entirely on the number of points candidates have earned (and thus, on characteristics of candidates). In practice, this leads to permanent turnover of substitute teachers, who are employed again at the start of every school year and for one school year only.

A separate question concerns the ability of principals to appraise the teachers in their school and to terminate the employment of those who, over several years, were appraised as not being competent. Current Greek legislation bars principals from appraising their teachers, and removing a weak permanent teacher from the profession is nearly impossible. The professional opinion of principals regarding teachers is not included as a criterion for national competitions for organic positions or for promotion. Similarly, a negative appraisal of a substitute teacher by their principal after one year of work in the school unit to which they were assigned has no impact on their future employment prospects as either a substitute or for their prospects to secure a permanent position.

Technical staff are selected and remunerated by local government officials. Here the discussions with principals are much easier, due to local presence of interested stakeholders, and a lack of national procedures and standards.

The main reason this situation is problematic is that it does not allow the school to develop responding to its specific needs, or to acquire a common approach to the pedagogical process within the school unit. Indeed, some of the Athens school units visited by the OECD review team were very proud of the fact that they have a stable teacher workforce, and explained in various ways how this contributes to better teaching. However, these school units also had either very small classes, or no substitute teachers. At the same time, the OECD review team was told that in the provinces, some school units change over half of their teacher workforce every school year. In other words, they do not have the stability so valued in prestigious urban school units, which are seen as desirable work placements for teachers.

The inability of the principal to shape the teaching workforce becomes challenging if a school unit is academically weak and needs a school improvement plan. Major elements of such plans involve teacher retraining, strengthening of teacher co-operation, elements of peer learning (including stronger teachers supporting those weaker or less experienced), and joint planning and evaluation of specific pedagogical interventions. All these elements require time to develop and implement, and therefore become challenging if pedagogical staff varies considerably from year to year. School improvement plans cannot be effective without honest appraisal of the contribution made to the pedagogical process by every teacher, and ultimately without a path to discontinue employment of weak teachers.

Specific needs of school units are not identified

Many independent, non-cooperating agents are involved in the governance of school units. Each of these independent agents uses a separate set of nationally mandated procedures and national norms in their allocation of different resources. It is unavoidable that the same fragmentation appears in the budget sphere, with no single agent knowing, planning and managing the complete school budget (see Section 2.2.3). Therefore, the specific needs of the school units are not identified and may remain unaddressed.

These needs may be of quite different types. Some may be due to student characteristics. A heterogeneous student population, for example including non-native Greek speakers, or Greek students coming from very different family or socio-economic backgrounds may require additional positions of psychologists or other support pedagogical staff or extracurricular activity support. In contrast, motivated students coming from wealthier, better-educated urban families may need different type of staff.

Different types of school unit needs may also arise due to the allocation of teachers to schools. A school unit may have mostly young and inexperienced teachers, or mostly elderly teachers who are losing motivation for long-term professional development. It is sometimes the case that some school units suffer because of conflicts between groups of teachers. This type of problem requires close analysis and careful resolution.

Specific needs of school units may be related also to inadequate infrastructure. However, school unit investments are the responsibility of K.Y.S.A., a state agency reporting to the Ministry of Infrastructure, Transport and Networks. This means that the agency collects and assesses nationwide data on school unit facilities, and uses its own criteria for allocating scare resources. These are technical and construction criteria, which may be in conflict with educational and pedagogical priorities.

School units have no institutional identity and no autonomy

As discussed in Section 2.1 of this chapter, school units in Greece are embedded in an administrative pyramidal structure, with no clear demarcation lines regarding staff and budgets. The school unit has no influence over the selection process of its teachers, for both permanent staff (with organic positions) and for seconded and substitute teachers there are complex, nationally mandated procedures and selection criteria. The composition of the teacher workforce changes from year to year, and while the situation is relatively stable in large, prestigious school units in Athens, in some regions the turnover may be close to 100% of teachers.

There are two main reasons for this turnover. One reason is that permanent teachers are by law employed only on a full-time basis, so for some subjects a school may not have enough teaching staff, while for others, it may have excess capacity. In that case, teachers may be seconded from their own school (where they have the organic position) to another school. Such secondments are decided every year by the DDE (primary or secondary as the case may be), often just before the start of the school year. Continuation of work of seconded teachers in the same school unit is not a priority.

The second reason is that there is an increasing number of substitute teachers, and they are employed for up to ten months per year (usually for the duration of the school year). Due to the nature of the selection process, the substitute teachers allocated to the school unit may change – and very often do change – from year to year. As a result, planning teachers’ continued professional development becomes very difficult, if development programmes continue beyond a single school year.

Similarly, the school units do not have budgets. Separate budget lines are determined by different ministries in unrelated budget procedures, and are never put together, even for reporting purposes. The effect of this system is a less than optimal use of available resources. Indeed, in the period of fiscal constraints, the most important budgetary issue is to balance the needs and to decide on trade-offs between different allocation options. For example, if additional resources are available, they can be used to contribute more effectively to school unit academic improvement: additional teachers, additional pedagogical support staff, or additional school equipment. Analogous choices arise if budget cuts are inevitable. With the fragmented budgetary process, this type of optimisation of resource use is not possible. And even more importantly, it is not clear which level of the governance pyramid would be able to undertake it.

This lack of institutional identity of school units is underlined by the very weak position of the principal of the school unit. Not involved in the selection of teachers, unable to supervise and assess their classroom practice, the school unit principal is primarily an administrator. In addition, due to lack of secretarial support in the school unit, the director may have to perform many routine functions such as distribution of chalk to teachers, further reducing her or his ability to strategically manage the institution (not to mention her or his prestige).

The lack of school unit identity becomes acutely problematic for those units experiencing difficulties, which may struggle to provide quality education, and may need school improvement plans.

The OECD review team visited some prestigious school units in large urban centres and noted that they have ways of overcoming these types of problems, mainly because they have a stable teacher workforce and long-lasting principals, who over time had been able to develop sound pedagogical practices. However, the share of substitute teachers in these school units was very low. Lack of school unit institutional identity is especially damaging for school units that are academically weak and face large teacher turnover.

As has been noted, the Greek MofERRA has recently introduced plans for increased pedagogical autonomy of school units through a new decentralised support structure. These plans are certainly encouraging. Nevertheless, pedagogical autonomy can only be effective if it goes hand in hand with the strengthening of institutional autonomy and supporting staff capacity – in particular with the strengthening of the position of principals and their ability to assess and select school unit staff. Without that crucial aspect, pedagogical autonomy may become meaningless.

2.2.2. School units are subject to excessive regulation and prescription

Being embedded in the national administrative structure (the pyramid), Greek school units are subject to many regulations and restrictions, and need to follow multiple time-consuming, unnecessary bureaucratic procedures. These regulate the planning of the school year, the division of students into classes (for example, by alphabetic order in secondary school units, with the aim to avoid sorting by ability, but sometimes leading to gender imbalance in classes), organisation of additional activities like school excursions, and similar.

Perhaps most intrusive are regulations of the teaching process in class. The OECD review team was told that for each grade and subject, teachers are obliged to discuss the same topics in the same or close to the same dates, as established in teaching schedules. As a rule, these schedules (built according to the teaching programme) are excessively crowded, so to follow them in every detail is next to impossible. The OECD review team was also told by teachers that they have identified and reported on various problematic issues in the textbooks, but the publishers did not correct them. Therefore, in separate obligatory documents, again for each grade and subject, the Ministry instructs all teachers which parts of the prescribed schedule, and which corresponding sections of the textbooks, should be skipped. Such “jumping around” within the approved teaching plan is probably easier for the Ministry to introduce and monitor than would be a reduction of the teaching programme or a redesign of the textbooks. The result is to make the work of teachers that much more difficult, however.

These types of rules disempower teachers, preventing any opportunities for initiative, and prohibiting individualisation of teaching. The more rules are imposed, and the more instructions are issued on how to skip parts of these rules, the less autonomous and responsible the teacher becomes. In some cases, she or he may simply struggle to know what to teach.

These rules also mean that even if some parts of the material are not fully mastered by the students, the teacher is obliged to continue to the next topic in order to catch up with the mandated schedule. Such continuation to the next topic affects entire classes, of course, and not just individual students with their diverse needs. For an academically weaker class, or for some subjects which are difficult to learn on one’s own, this can lead to real long-term problems. Conversely, teachers cannot accelerate topics which students find easier (or with classes which are more motivated), and so free the available teaching time for more demanding questions.

Separate rules prohibit the use of educational material from other non-approved sources. Today, all students have access to the Internet and to many different learning tools – from Wikipedia to Internet search engines. There are obvious dangers to using fake sources and invalid references, and it should be one of the functions of the school to teach students how to make selective use of available information and how to question and verify everything they find on a smartphone or laptop. However, use of non-prescribed materials, including from the Internet, is not allowed in Greek school units. This limits the access of students to potentially valuable, diverse teaching materials, and also prohibits teaching of responsible and critical use of the Internet.

In practice, some teachers do use other, non-prescribed material, or deviate from the strictly imposed order of teaching. However, they need to do this without leaving traces, especially in official documentation that may be checked by school advisors from DDE. Principals have no influence on these matters either, and the OECD review team heard that they generally prefer not to know what is going on.

Again, it needs to be stressed that this prescriptive approach to regulating the pedagogical process is most damaging to school units in remote areas, with students coming from different social backgrounds, and to academically weak school units. When teaching highly motivated students, teachers may be able to follow all the prescriptions and still find time and energy to offer their students quality pedagogy. In contrast, when students are not motivated, and when they sometimes need to be taught the basics, the prescriptive approach becomes counterproductive.

2.2.3. Financing of school units is fragmented

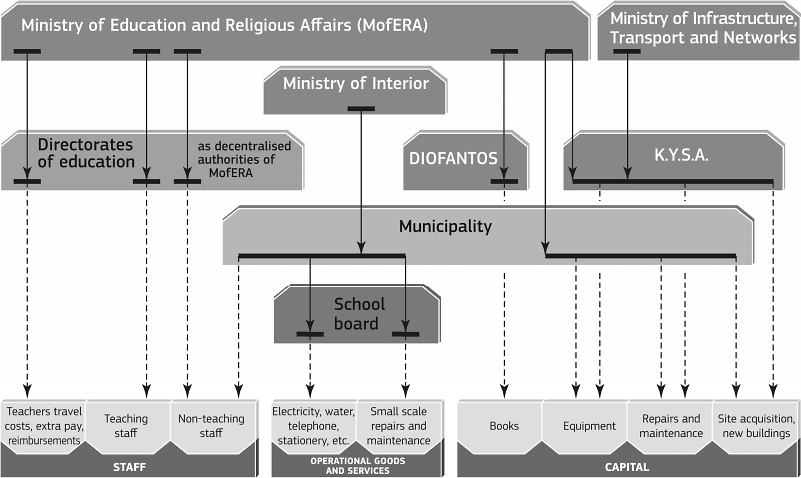

As briefly discussed in the preceding section, the funding for Greek school units comes from multiple sources. Figure 2.3 provides an overview of financial flows.

Figure 2.3. Funding of Greek schools, 2014

Source: European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2014[10]), Financing Schools in Europe: Mechanisms, Methods and Criteria in Public Funding, http://dx.doi.org/10.2797/7857.

The financial flows depicted in Figure 2.3 may be described in the following way:

The largest proportion of funds is allocated directly to the pedagogical staff of school units from the Ministry of Finance, and covers the salaries of permanent staff (public servants, from the state budget of Greece) and of temporary staff (seconded teachers, from the state budget of Greece; substitute teachers from the European Social Fund). This part of the school unit budget is managed by the Ministry of Finance, and is allocated on the basis of data collected from the school units. These data, including the amounts allocated to every school unit, are not directly available to the MofERRA.

The salaries of technical staff and the maintenance expenditures (heating, electricity, water, communal expenses, materials, small repairs) are financed from municipal budgets. For this purpose, municipalities use funds allocated to them by the Ministry of Internal Affairs. This is a cascading flow: money is first transferred from the national to municipal budgets in the form of grants, and then transferred from municipal budgets to bank accounts of technical staff. The allocation of the grant is performed according to a formula, which presumably takes into account the number of students, the number of school units, and also the fiscal situation of the municipality (the OECD review team was not able to obtain and review this formula). The MofERRA does not know the amounts of budget involved nor the allocation mechanisms used by the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Textbooks are managed by the Diophantos Computer Technology and Publications Institute, a national agency subordinated to the MofERRA, named after the famous ancient Greek mathematician. The printing and delivery of textbooks is conducted based on data collected from school units by Diophantos (the exact procedure was not disclosed to the OECD review team). Diophantos prints textbooks approved by the Ministry, every year for every grade and every subject, and then delivers them free of charge to all students. The numbers of textbooks, their destination, and the expenditure amounts involved are directly available to the MofERRA for review, should it wish to analyse them (it only needs to request the data from Diophantos).

New school investments are financed by K.Y.S.A. agency under the Ministry of Infrastructure Transport and Networks. In particular, K.Y.S.A. is responsible for purchases of land and buildings and for managing new constructions. For these purposes, K.Y.S.A. has its own budget allocation from the Ministry of Infrastructure, Transport and Networks, and uses it to address deficiencies in school unit infrastructure, based on its own priorities. Clearly, K.Y.S.A. needs its own data collection processes to decide on the priorities and sequencing of school unit investments. K.Y.S.A. expenditure data are directly available to the MofERRA.

School unit repairs, maintenance and equipment are partially financed from municipal budgets, and partially by K.Y.S.A. The school unit does not receive funds for this purpose, instead it is provided with appropriate new equipment. These are two separate financial flows supporting operations of school units, coming from different budgets and based on separate data, collected through different procedures. Funds from municipal budgets for repairs and maintenance are obtained through own revenues of municipalities. K.Y.S.A. budget for repair and maintenance comes from the MofERRA (and is separate from K.Y.S.A. budget for infrastructure). Only expenditure data on equipment coming from K.Y.S.A are directly available to the MofERRA.

Unfortunately, the OECD review team was not able to obtain even rough estimates of the sums involved in each of these five expenditure streams from the MofERRA. This indicates that there is no routine mechanism in the Ministry to assess, monitor and steer the overall financing of school units, or to assess and address potential imbalances in the financing of different subsectors of education (i.e., preschool, primary, lower secondary and upper secondary schools).

For each of these expenditure flows (fragments of school unit budgets), a different budgeting process takes place. Of course, each budgeting process involves collection of necessary data, planning of the budget lines for the next fiscal year, making actual expenditures during the fiscal year, and finally reporting of the expenditures made. There are allocation procedures for each budget stream, and in some cases even allocation formulas. However, these procedures and formulas are not known to the MofERRA and most likely do not include many relevant education factors. Each expenditure flow has a different institution bearing the political responsibility and taking the final decisions about the allocation and use of budget funds.

One consequence of this fragmentation is that it is impossible to assess and address regional disparities in spending on primary and secondary education. Such disparities, if they appear, always require review and effective countermeasures. It is worth adding here that about one third of the Greek education system is in two major urban areas – Athens and Thessaloniki (Roussakis, 2017[1]). It is most likely that per class spending in the school units located in these areas is much higher than in rural school units, while per student spending is much lower (due to larger classes). However, with the current limited availability of budget data, such an important analysis cannot be performed.

Another consequence is that it is extremely difficult to know how much Greece is spending on education altogether. Neither the OECD Education at a Glance (OECD, 2017[8]) nor Eurostat can provide data on education expenditures as percentage of Greece’s GDP. Indeed, there are two official numbers submitted to the European Union, namely 3.2% of GDP as assessed by Eurydice, and 4.5% of GDP as assessed by Eurostat (KANEP/GSEE, 2016[18]). The difference between these two numbers is a staggering 1.3% of GDP. It is unclear how either of these two figures was extracted from raw budget data and calculated. Both of these figures are quite low compared to the OECD average of 5.2% (OECD, 2017[8]). This suggests, but cannot be taken as a proof, that Greek education is underfunded. Towards the end of its mission, the OECD review team was informed that recent analysis indicated that the higher of these two numbers is more likely to be correct, but there was still no definite answer.

Finally, it is worth noticing that Diophantos is in the process of implementing a new national education database, called MySchool. This is a new and praiseworthy initiative which aims to address a serious weakness of Greek education. As identified among other issues in a recent OECD report, basic statistical data on students and teachers are unreliable, with little coherence between data collected by the MofERRA and by the Hellenic Statistical Authority (OECD, 2017[22]). Hopefully, MySchool will provide reliable student and teacher data. There are plans to include financial data in that database, as well. However, there is a risk that unless basic coherence on reporting of budget expenditures is achieved, entering budget data into MySchool may simply create a third, unrelated and uncorrelated source of information on budget expenditures on education – further compounding rather than clarifying the situation.

2.2.4. The underfinancing of education

As mentioned above, the estimates of overall spending on education in Greece range from 3.2% to 4.5%. These figures are quite low by international standards, and they indicate that Greek education is almost certainly underfinanced, if the true level of expenditures lies between them (something which seems likely but which cannot be confidently asserted at present).

It cannot be stressed strongly enough that persistent underfinancing of education has long-lasting negative effects on the operations of school units and on the quality of teaching and learning. It results in relatively low salaries, in shortages of teaching and support personnel, in inadequate school unit equipment and in deteriorating school unit facilities. In specific conditions of Greece, it is also accompanied by growth of privately funded supplementary education. The case for reversing these trends is therefore strong.

However, given the fragmentation of education finance and the complexity of funding sources and allocation methodologies (see Section 2.2.3), there is no simple way for the Ministry to address this potential underfunding. The complex machinery of recurrent and capital budgeting may be able to continue operating within the status quo, but is unwieldy as an instrument for making serious changes to financing levels.

The MofERRA argues, as discussed already, for more organic positions in primary and secondary school units. Presently it is impossible to state what the priorities in allocating these new organic positions should be. For example, the relative needs of primary and secondary education cannot be assessed, and the detailed data are maintained and processed by separate institutions (District Directorates of Primary Education and District Directorates of Secondary Education). Therefore, it is not easy to assess how many new organic positions should be created in primary, in lower secondary and in upper secondary education. The share of substitute teachers is particularly high in special vocational education (see Table 2.1). It is unclear, however, whether this means that more new organic positions should be allocated to these schools.

Further and perhaps more importantly, it is unclear how to distribute new organic positions across regions, districts and school units. The Ministry needs solid empirical evidence before it can make decisions as to the optimal distribution of positions to benefit the pedagogical work of school units. The new MySchool database, when operational, may provide some of the necessary data. For example, these data may support decisions, in each specific case, as to whether to staff small island and rural school units with new organic positions, or to consolidate them into larger school units. Relative needs have to be assessed taking into account also social conditions and the educational environment in which school units operate.

Further, provision for salaries of permanent teaching staff is only one, albeit the largest, expenditure stream in Greek education finance (one of five, see section 2.2.3). Good review of relative needs of school units must be undertaken, so that Greece can confidently decide, whether more funds should be directed to textbook provision, to ensure that these are updated, modernised and made attractive for students, or whether Greece should invest in school facilities and teaching equipment, or in school maintenance and in salaries of technical staff. As an example, we note that increase of support staff employment, such as school unit secretaries, would allow principals to focus on more important pedagogical tasks (see Section 2.3.4).

Apart from addressing the relative underfinancing of different subsectors of education, and of different types of expenditures, Greece will also need to address relative underfinancing of regions and perhaps even of districts.

Lacking nationally collected, trustworthy budgetary data covering all expenditures of school units, and without comparable data on school unit facilities across the regions, the Ministry risks taking decisions based only on subjective judgements, with less than optimal effects for education.

2.2.5. The use of textbooks is inefficient

There is no doubt that textbooks, both electronic and printed, are a major education resource for school units. In Greece, a full set of textbooks for all subjects is provided every year free of charge to all students of primary and secondary education (the same applies also to higher education, as discussed in Chapter 5). Clearly, this is a very expensive approach to textbook provision, although the OECD review team did not have access to actual budget expenditure data on textbooks.

In practice, the Greek approach works as follows: textbooks are approved for use in school units by the MofERRA; for each grade and each subject there is only one approved textbook (there is no choice of textbooks). Thus, all teachers use the same basic material for teaching (this is, indeed, a necessary pre-condition for imposing a common teaching schedule on all Greek schools). The approved textbooks are printed by Diophantos CTI and then distributed to all Greek school units.

The textbooks provided to students become their property, and do not have to be returned for reuse by the next cohort of students. In other words, textbooks are designed to be used for only one year. The following school year, textbooks for all grades and for all subjects are printed again for all students. This certainly encourages waste and lack of respect for books. At the same time, massive costs incurred in printing so many textbooks destined to be used for one year only create a strong motivation to prepare cheap, low-quality, and easily damaged textbooks, which may sometimes not even last the full school year.

Distribution requires collection and processing of many data items for all primary and secondary school units. In the future, this will certainly be performed using the MySchool database (which is being developed by the same national agency Diophantos CTI), but until then, this is a serious administrative burden (particularly in ensuring completeness of data and correction of data errors). Moreover, distribution costs are most likely higher than actual printing costs, in part because books are heavy, and in part because of the remote location of many Greek school units.

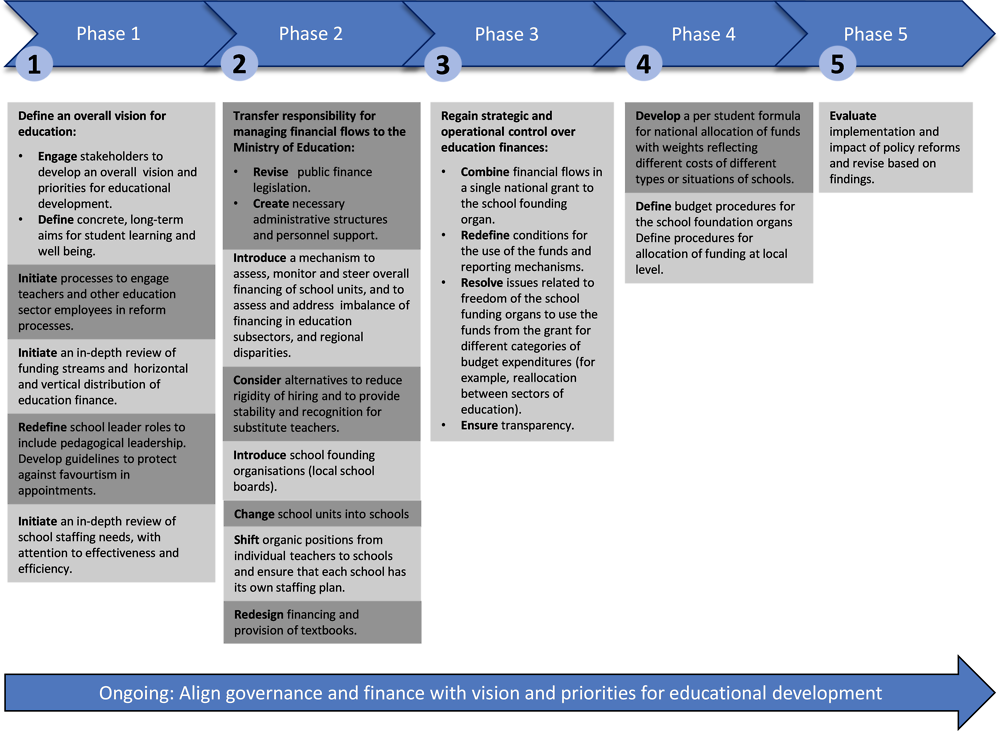

Moreover, there has been remarkably little modernisation of the unique textbooks used in Greek education. In lower secondary schools, the content of many textbooks is 10 years old, in upper secondary schools, many are 20 years old. This in part explains why there are yearly updated instructions which part of textbooks to skip, and which to use (the OECD review team was shown some of these instructions). Obsolete textbooks are especially troubling in upper secondary school units, where the most up-to-date knowledge should be taught. For students who access the Internet on their smartphones constantly, use of such outdated education material, even if available online at a dedicated website (http://ebooks.edu.gr/), may not inspire respect for the school system.