This chapter discusses how education systems can develop capacity to respond to diverse student needs and create a system in which school staff, students, parents, guardians and members of the broader community all share and support the will to foster equity and inclusion. It discusses the importance of preparing teachers to address diversity and promote equity and inclusion, and of recruiting and retaining teachers from diverse backgrounds. This chapter also considers capacity building in terms of cultivating values of acceptance, tolerance and respect among students. Finally, it discusses the importance of building awareness among parents, students, teachers and communities more broadly, as a key step in ensuring that the different stakeholders of a given system are on board with and collaborate for advancing equity and inclusion in education.

Equity and Inclusion in Education

4. Building capacity to foster equity and inclusion

Abstract

Introduction

This chapter examines the importance of capacity building in supporting all learners to achieve their educational potential and in fostering students’ self-worth and sense of belonging to schools and communities.

Teacher quality has frequently and long been acknowledged as a significant factor in students’ academic performance. However, beyond learning outcomes, teachers, as the primary actors in the classroom, also play a critical role in fostering students’ overall well-being. In light of this, developing teachers’ capacity to identify and serve students’ needs has been recognised as a key policy lever in advancing equity and inclusion in education. This involves not only incorporating competences and knowledge areas for equitable and inclusive teaching into initial teacher education (ITE) programmes but also ensuring that teachers are able to update and deepen their knowledge through high-quality professional learning and opportunities for collaboration. Professional learning and opportunities for collaboration are also essential to prepare and support school leaders, who are central actors in shaping the ethos of schools, and in ensuring that policies for equity and inclusion are carried into effect through practices tailored to the local context of the school and community.

Enhancing the diversity of the teaching workforce can have positive impacts on multiple dimensions of student well-being, from learning to broader socio-emotional outcomes, for both learners from diverse groups and for the student body as a whole. However, lack of diversity among teachers is a challenge faced by many OECD education systems, with evidence showing imbalances in representation across various dimensions of diversity. Addressing this involves considering both strategies for attracting diverse candidates into initial teacher education and how diverse teachers can best be supported so that they are more likely to stay in the profession.

Beyond teachers and school leaders, the perceptions and attitudes of a range of stakeholders feed into shaping the classroom environment and the extent to which it is inclusive for diverse students. Cultivating an appreciation for diversity and values of acceptance, respect and understanding among students is a crucial aspect in creating learning spaces in which all students feel a sense of belonging and can achieve their educational potential. In addition, raising awareness of diversity in society among parents and community members is also an important foundational step in advancing equity and inclusion in education, both to mitigate stereotypical or discriminatory beliefs and to ensure that a range of stakeholders support and contribute to the successful implementation of equitable and inclusive policies and practices.

This chapter has seven sections. After this introduction, the second section discusses the importance of preparing teachers to effectively respond to diversity in the classroom, examining in particular how diversity, equity and inclusion can be incorporated into teachers’ initial teacher education and continuous professional learning. The third section then considers the various functions and roles of school leaders in promoting equity and inclusion in education, and reflects on the need to prepare and support school leaders in this respect. The fourth section addresses strategies to promote the recruitment and retention of teachers from diverse backgrounds and groups, in light of the positive impacts enhanced diversity of school staff can have for student well-being. This chapter then explores how schools can cultivate values of acceptance, respect and understanding by fostering positive relationships among students, before discussing the importance of awareness-raising to ensure wide-ranging support for and collaboration in the implementation of policies and practices to promote equity and inclusion in education. It concludes by setting out some pointers for policy development.

Preparing and supporting teachers to respond to increasing diversity and create equitable and inclusive learning environments

Efforts to promote equity and inclusion in education depend upon high-quality teachers who are properly prepared and supported to respond to increasing diversity and create learning environments in which all students can thrive (Cerna et al., 2021[1]). Teachers, as the predominant actors in setting the nature of the classroom environment, play a pivotal role in multiple dimensions of student well-being. While teacher quality has frequently and long been acknowledged as having a powerful impact on students’ learning outcomes (OECD, 2022[2]), teachers can also raise students’ social and emotional skills (Blazar and Kraft, 2017[3]; Jackson, 2018[4]; OECD, 2022[2]), and their dispositions and competences can influence students’ engagement, drive and self-beliefs (Rutigliano and Quarshie, 2021[5]). Teachers’ practices have, for instance, been recognised as playing a role in reducing cognitive and socio-emotional gaps related to socio-economic status (OECD, 2018[6]). Research further shows that teachers, and in particular their attitudes, will and training, have a profound influence on the educational development and psychological well-being of gifted students, playing a central role on their identification, support and monitoring (De Boer, Minnaert and Kamphof, 2013[7]; Lassig, 2015[8]; Plunkett and Kronborg, 2019[9]; Polyzopoulou et al., 2014[10]; Rutigliano and Quarshie, 2021[5]). Similarly, teachers often play an important role in the recognition or identification and referral of various special education needs (SEN), such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Brussino, 2020[11]; Mezzanotte, 2020[12]; Moldavsky et al., 2012[13]). There is also evidence to indicate that teachers’ perceptions, and specifically their expectations regarding educational potential and attainment, can impact on the learning outcomes of refugee students (Koehler, Palaiologou and Brussino, 2022[14]).

In light of this, developing teachers’ capacity to manage diversity and respond to all students’ needs has been recognised as a key policy lever in advancing equity in education (OECD, 2018[6]). Beyond being a central aspect in supporting all learners to achieve their educational potential, it is also a crucial component in fostering students’ self-worth and sense of belonging to schools and communities (Cerna et al., 2021[1]).

Competences and knowledge for equitable and inclusive teaching

Teaching is a complex, multifaceted task, and even more so in a context of rapid societal change (Forghani-Arani, Cerna and Bannon, 2019[15]). Increasing diversity in the classroom is resulting in additional expectations and demands on teachers, who are required to respond to a growing range of student needs (Brussino, 2021[16]). In order to be able to create equitable and inclusive learning environments that support all learners in achieving their educational potential, teachers need to be equipped with a range of competences, knowledge and attitudes (Cerna et al., 2021[1]). Knowledge areas for equitable and inclusive teaching are wide-ranging and may encompass cultural anthropology, social psychology, child cognitive development, integrated learning and second language acquisition (OECD, 2017[17]). These areas are in addition to a strong understanding of the different dimensions of diversity and of how they may intersect, which is a crucial foundation for the creation of equitable and inclusive learning environments (Cerna et al., 2021[1]). Teachers would also benefit from having knowledge and an appreciation of the historical, social and cultural context of the communities in which they teach. This has been identified as a key area for teachers’ professional development in relation to teaching Indigenous students, along with knowledge of the relevant Indigenous language (OECD, 2017[18]). Research in the context of the United States also suggests that the extent to which White teachers address and value Black students’ primary culture can be a significant factor in their academic success (Douglas et al., 2008[19]; Hale, 2001[20]; Irvine, 1990[21]). Teachers’ reported culturally responsive teaching behaviours in relation to Spanish language and cultural knowledge have also been significantly and positively correlated to Latino students’ reading outcomes in the United States (López, 2016[22]).

Supporting the learning and well-being of all students also requires teachers to have strong theoretical knowledge of differentiated instruction and the skills to put this into practice. Differentiated instruction has been defined as “an approach to teaching that involves offering several different learning experiences and proactively addressing students’ varied needs to maximise learning opportunities for each student in the classroom” (UNESCO, n.d.[23]). Differentiated instruction is at the core of equitable and inclusive education systems, as it means responding to and serving all student needs (OECD, 2022[24]), thereby supporting all learners in achieving their educational potential (OECD, 2012[25]). It requires teachers to recognise students’ different learning abilities, be flexible in their approach and adjust the way information is delivered to suit the needs and characteristics of different learners (OECD, 2022[24]; UNESCO, n.d.[23]). Differentiated instruction can, for instance, help foster the learning of students with an immigrant background by taking into consideration their proficiency in the host country language and adjusting learning content in light of this (Fairbairn and Jones-Vo, 2010[26]; OECD, 2022[24]). Teachers’ abilities to adapt and differentiate teaching methodologies can also play an important role in supporting the academic success of students with ADHD (HADD Ireland, 2013[27]; Mezzanotte, 2020[12]). Research has further shown that tailoring teaching strategies to suit the needs of gifted students can enhance their learning outcomes at different levels of education (Callahan et al., 2015[28]; Rutigliano and Quarshie, 2021[5]).

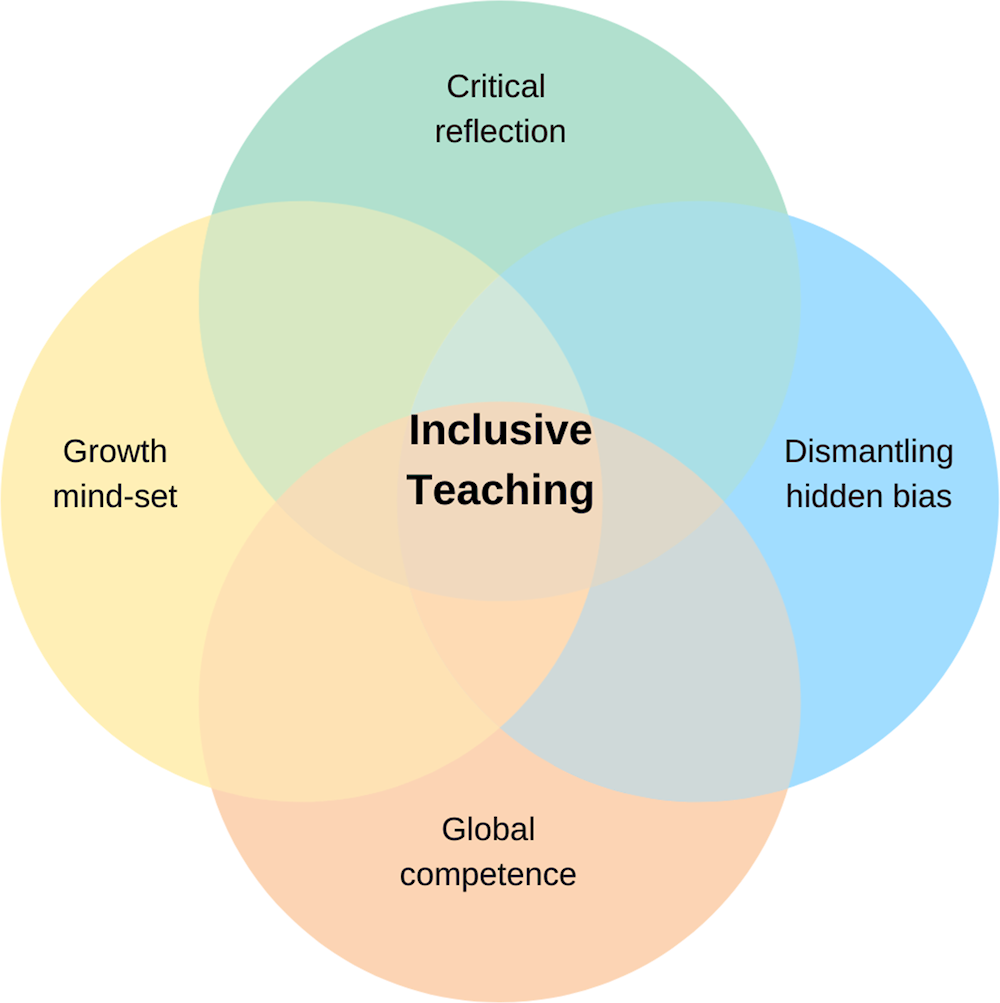

The acquisition of these knowledge areas is both facilitated by and enables the development of the competences that are required for equitable and inclusive teaching. Brussino (2021[16]) identified four core competences that are key for teachers’ ability to create learning spaces where all learners can thrive (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Core competences for inclusive teaching

Source: Brussino (2021[16]), "Building capacity for inclusive teaching: Policies and practices to prepare all teachers for diversity and inclusion", OECD Education Working Papers, No. 256, https://doi.org/10.1787/57fe6a38-en.

i. Critical reflection

Critical reflection refers to the process by which individuals identify the assumptions behind their actions, understand the historical and cultural origins of these assumptions, question their meaning and develop alternative ways of acting (Brussino, 2021[16]; Cranton, 1996[29]). When teachers critically reflect upon their identities, they can better understand and navigate the assumptions and perspectives they take into the classroom, which can affect how they teach and thus impact on students’ learning and well-being (Brussino, 2021[16]; Shandomo, 2010[30]). Critical reflection can also help teachers acknowledge social constructs and the way in which perceptions of various dimensions of diversity contributes to creating sources of marginalisation and discrimination (Brussino, 2021[16]).

ii. Dismantling unconscious bias

Both teachers and students participate in the classroom with unconscious biases (Brussino, 2021[16]). These biases, which may be shaped by a diversity of factors (such as previous experiences, personal interactions and stereotypes), can affect their interactions and decision-making process in the classroom (Brussino, 2021[16]). Teachers can perpetuate or accentuate students’ hidden biases by relying solely on their own cultural frames of reference, using language that is not inclusive of all students, or by favouring students who share their own perspectives and viewpoints (Brussino, 2021[16]). In turn, teachers’ hidden biases can negatively affect student performance, self-expectation and learning (Cherng, 2017[31]; Lavy and Sand, 2015[32]). Teachers working in disadvantaged schools, for example, tend to hold low expectations regarding students’ academic achievement, which can negatively impact students’ self‑esteem, aspirations and their motivation to learn and thus contribute to reinforcing inequities in education (OECD, 2018[6]; OECD, 2012[25]). Teachers can also have preconceptions regarding the capabilities of refugee and newcomer students, believing that these students are not capable of high achievement (McBrien, 2022[33]). Similarly, labelling students as having particular SEN can reduce the academic expectations held and set by teachers (Brussino, 2020[11]; Higgins et al., 2002[34]). Research has shown, for instance, that ADHD classification among students is negatively associated with teachers’ academic expectations, which can in turn impact students’ achievement, motivation and self-confidence (Batzle et al., 2009[35]; Mezzanotte, 2020[12]). Evidence also shows that both unconscious gender stereotyped bias among teachers can influence the way in which teachers award grades to students of different genders (Lavy and Sand, 2015[32]; OECD, 2015[36]). Teachers’ preconceived ideas have further been shown to result in them being less likely to identify students from lower socio-economic and/or diverse backgrounds as gifted, which contributes to the underrepresentation of certain groups in gifted backgrounds (Casey, Portman Smith and Koshy, 2011[37]; Ford, 2010[38]; Rutigliano and Quarshie, 2021[5]). In addition to affecting the way in which they interact with or perceive their students, teachers’ biases, if unaddressed, may result in them perpetuating an environment that is unsafe or harmful for some students, through, for instance, making prejudicial remarks about certain groups or neglecting to address those made by other students (McBrien, Rutigliano and Sticca, 2022[39]).

In order to be able to create environments that are inclusive for all learners, it is crucial that teachers are able to recognise their own biases and the ways in which these can impact on students, to reflect on them critically, and to engage in strategies to mitigate them (Brussino, 2021[16]).

iii. Global competence

Global competence can be defined as “the capacity to examine local, global and intercultural issues, to understand and appreciate the perspectives and world views of others, to engage in open, appropriate and effective interactions with people from different cultures, and to act for collective well-being and sustainable development” (OECD, 2018, p. 7[40]). Global competence requires a perspective-taking approach, adaptability, and a diverse set of socio-emotional skills, including communication and conflict resolution capabilities (OECD, 2018[40]). Equipping teachers with the knowledge and skills to develop their global competence is crucial to enable teachers to facilitate discussions on diversity and to promote inclusion in the classroom (Brussino, 2021[16]).

iv. Promoting a growth mind-set

Promoting a growth mind-set (in which individuals understand their abilities and knowledge as being able to be developed through effort, strategies and support (Dweck, 2016[41])) can have positive learning impacts, such as higher student motivation and performance, especially for students from disadvantaged backgrounds (Brussino, 2021[16]; Dee and Gershenson, 2017[42]). On average across OECD countries participating in PISA 2018, students who reported having a growth mind-set scored higher in reading, science and mathematics than students who reported having a fixed mind-set. A growth mind-set was associated with a larger score gain for students from disadvantaged backgrounds and immigrant backgrounds, when compared to advantaged and non-immigrant students (Gouëdard, 2021[43]), which indicates that facilitating the development of a growth mind-set in the classroom can be important from an equity perspective. A growth mind-set approach can be fostered through conceiving of and using feedback and formative assessments as a tool for student growth (Brussino, 2021[16]), as well as through pedagogies and teaching strategies that concentrate on students’ effort rather than their intelligence (Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020[44]).

There is a need to better prepare and support teachers to respond to increasing diversity in the classroom

Despite growing interest in equity and inclusion in education, research suggests a need for greater emphasis on diversity, equity and inclusion in teacher training across OECD countries. (Brussino, 2021[16]). In the most recent OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), only 35% of lower secondary teachers reported that teaching in multicultural and multilingual settings had been included in their ITE and only 22% reported that it had been included in their professional learning activities in the previous 12 months, on average across the OECD (OECD, 2019[45]). Data from TALIS 2018 further showed that teachers generally did not feel confident in their ability to teach effectively in multicultural classrooms. On average across the OECD, only 26% of lower secondary teachers reported feeling well or very well prepared for teaching in a multicultural or multilingual setting upon finishing their formal ITE or training, and 33% of teachers reported that they still did not feel able to cope with the challenges of a multicultural classroom at the time of the TALIS survey completion (OECD, 2019[45]).

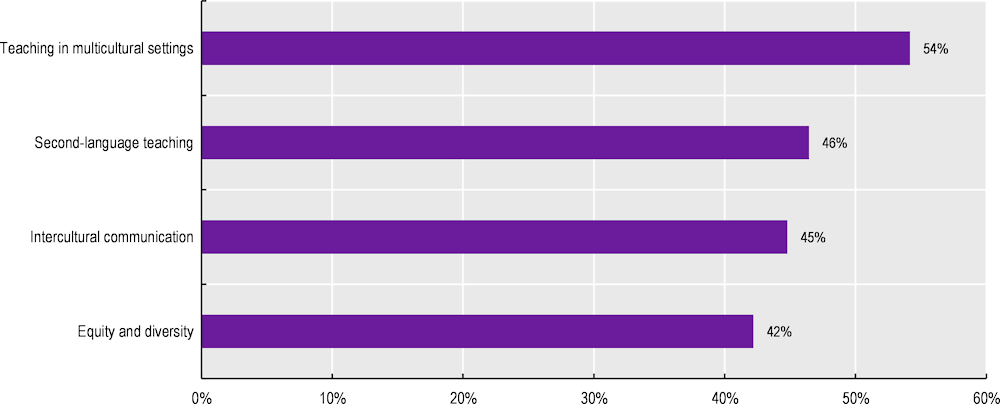

Teachers’ self-perceived need for greater training in teaching in multicultural or multilingual settings, and in relation to diversity, equity and inclusion more generally, is also reflected in the OECD PISA 2018 survey (Figure 4.2). The results show, for instance, that, on average across participating countries, 54% of students attended a school where teachers reported a moderate-to-high need for training on teaching in multicultural or multilingual settings and 46% of students had teachers who reported a need for training in intercultural communication (OECD, 2020[46]). This need appears particularly acute in light of the fact that data from TALIS 2018 showed that 17% to 30% of teachers across the OECD worked in schools with a culturally or linguistically diverse student population, depending on the criterion considered (OECD, 2019[45]). Data further revealed a global increase between 2013 and 2018 in the share of teachers expressing a high need for training in teaching in a multicultural or multilingual setting (OECD, 2019[45]).

Figure 4.2. Teachers' needs for training on diversity, equity and inclusion (PISA 2018)

Source: OECD (2020[46]), PISA 2018 Results (Volume VI): Are Students Ready to Thrive in an Interconnected World?, Table VI.B1.7.15, https://doi.org/10.1787/d5f68679-en.

Data from TALIS 2018 also revealed a need for greater teacher preparation in relation to teaching students with diverse abilities. While 62% of teachers reported that training on teaching in mixed-ability settings had been included as part of their formal ITE, only 44% of teachers reported feeling prepared to teach in such settings on completion of their studies (OECD, 2019[45]). At least one in five teachers on average across OECD countries reported a need for training on SEN, while 32% of school leaders reported that the delivery of quality instruction in their schools was hindered by a shortage of teachers with competence in teaching students with SEN (ibid.).

Research shows that teacher training and professional learning related to diversity and inclusion is important for teachers’ feelings of self-efficacy regarding their ability to teach in diverse classrooms, as well as having a positive impact on their teaching practices (OECD, 2022[47]) and on their ability and willingness to support the needs of all learners. TALIS 2018 showed, for instance, that teachers who received training on teaching in multicultural or multilingual settings as part of their ITE and/or through continuous professional learning report higher levels of self-efficacy in teaching in such settings (OECD, 2019[45]). Research further showed that training on teaching in multicultural environments can help in addressing teachers’ biases (Parkhouse, Lu and Massaro, 2019[48]) and in strengthening their capacities to foster positive relationships with students (Biasutti et al., 2021[49]; Varsik and Gorochovskij, Forthcoming[50]). Evidence also shows that gifted education programmes, from identification and assessment of students to differentiation and other pedagogical strategies, are more effectively implemented by teachers who have undertaken specialist studies in gifted education (Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation, 2019[51]; Rutigliano and Quarshie, 2021[5]). Dedicated training courses have also been positively associated with improved teacher understanding of, and greater confidence in teaching content related to, LGBTQI+ issues (Greytak, Kosciw and Boesen, 2013[52]; Greytak and Kosciw, 2010[53]; Kearns, Mitton-Kukner and Tompkins, 2014[54]; McBrien, Rutigliano and Sticca, 2022[39]).

Strengthening the incorporation of topics related to diversity and inclusion in initial teacher education

Preparing and supporting teachers to respond to increasing diversity in the classroom and promote equitable and inclusive learning environments starts with ITE. Initial teacher education sets the foundation for teachers’ on-going professional learning and plays a crucial role in equipping prospective teachers with the competences, values and knowledge to respond to a diverse range of needs and support all learners in achieving their educational potential (OECD, 2022[24]).

Integrating diversity, equity and inclusion into initial teacher education curricula

While, as discussed above, data reveal a need for greater teacher training with respect to teaching in diverse classrooms, examples of content relating to equity, inclusion and diversity and inclusion can be found in ITE curricula in several education systems across the OECD. Dedicated, ad hoc courses on topics related to diversity, equity and inclusion – such as multicultural education and urban education – have increasingly been integrated into ITE curricula in various states across the United States for instance, along with community-based activities in diverse school settings (Brussino, 2021[16]; Mule, 2010[55]; Yuan, 2017[56]). Standalone courses related to diversity, equity and inclusion can also be found in the curricula of ITE programmes in several European countries (Brussino, 2021[16]; European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, 2017[57]). In Germany, for instance, prospective teachers are able to select two courses on SEN as part of ITE (Brussino, 2020[11]). In Denmark, the mandatory ITE module “Teaching bilingual children” “aims to prepare all student teachers to teach bilingual children and to deal with the identification of second language educational challenges in the teaching of subject knowledge” (European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, 2017, p. 62[57]).

In addition to standalone theoretical courses and modules, training on teaching in diverse settings has also been incorporated into ITE curricula through specific practical activities and programmes that encourage prospective teachers to critically reflect on their own worldviews or biases. In Melbourne, Australia, for example, the eTutor programme piloted by the RMIT School of Education aimed to strengthen pre-service teachers’ capacity to teach in multicultural environments by creating an online space in which they could interact and engage in dialogue with students from other cultures (Gottschalk and Weise, Forthcoming[58]). An evaluation of the programme revealed that these interactions helped shift the attitudes of many of the pre-service teachers who participated and promoted greater understanding and empathy for students from diverse cultural backgrounds (ibid.). In the United States, the Persona Doll Project was a semester-long practical exercise undertaken by undergraduate pre-service teachers as part of an early childhood teaching programme (Brussino, 2021[16]; Logue, Bennett-Armistead and Kim, 2011[59]). Each student was given a persona doll with backgrounds and life experiences different to their own and was required to act as an advocate for the child personified by the doll, using storytelling to inform other students in the course of issues related to diversity, equity and inclusion associated with the doll’s identity. The project helped promote awareness among pre-service teachers of their own assumptions along with improved understanding as to how different teaching strategies can promote inclusion in the classroom, with the students reporting greater confidence in teaching in diverse settings after having participated in the project (Logue, Bennett-Armistead and Kim, 2011[59]; Brussino, 2021[16]).

Incorporating hands-on classroom experience in ITE is key in preparing prospective teachers for classroom diversity, as it allows practical prospective teachers to become familiar with classroom dynamics, connect pedagogical theories to classroom practices and anticipate the challenges they might face in schools (Brussino, 2021[16]; Musset, 2010[60]; OECD, 2019[61]; European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, 2017[57]). Indeed, research indicates that practical experiences in diverse environments can have positive impacts on student teachers, helping them to reflect on and question their values and attitudes as well as supporting the acquisition of knowledge and competences relating to diversity, equity and inclusion in education (European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, 2017[57]). Structured field experiences, for instance, have been recognised as helping to foster prospective teachers’ cultural awareness, when combined with opportunities for meaningful reflection (Acquah and Commins, 2017[62]). In Australia, students enrolled in the Master of Teaching programme at the University of Melbourne who are interested in teaching in regional or remote areas of Australia have the opportunity to develop their expertise in working with Indigenous students and communities through the “Place Based Elective”. The Elective includes a professional practice component, where student teachers live and work with an Indigenous community, and an on-campus learning component, where student teachers develop their knowledge and skills in this area by engaging with the research literature and sharing their learning experiences with others (The University of Melbourne, 2022[63]). In the United States, the School of Education at Indiana University offers several cultural immersion programmes that provide pre-service teachers with the opportunity to develop their skills in teaching students from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds (Cerna et al., 2019[64]). Placements include the American Indian Reservation in the Navajo Nation, the Hispanic Community in the lower Rio Grande Valley, urban settings in Indianapolis and Chicago, and multiple international locations in Latin America, Europe, Asia and Africa. Studies on the programme have highlighted its positive impacts in terms of shifts in pre-service teachers’ consciousness and perspectives, as well as their appreciation for other cultures and awareness of diversity at both the global and the domestic level (ibid.).

Incorporating equity and inclusion as part of the specified objectives and competences for initial teacher education

Despite research suggesting that ITE is more effective in preparing teachers for inclusive teaching where equity and inclusion are embedded into the curriculum as central and cross-cutting themes, ITE training on these concepts currently tends to be limited to standalone, ad hoc courses addressing specific dimensions of diversity, if it features at all (Rouse and Florian, 2021[65]; UNESCO, 2020[66]).

A way in which education systems can seek to address this issue is by incorporating knowledge and skills related to diversity, equity and inclusion within the competence frameworks or standards that set out what prospective teachers are required to demonstrate at the completion of ITE. As competence frameworks and teacher standards can influence the content that is taught in ITE, this may be a way of ensuring that prospective teachers are equipped with at least some of the necessary competences to respond to the needs of diverse learners before entering the classroom (OECD, 2022[24]), though further research is required to ascertain how effective this is in practice. The Teachers’ Standards in England (United Kingdom), for instance, specify that both trainee and practising teachers must (Department for Education, 2021[67]):

i. know when and how to differentiate appropriately, using approaches that enable pupils to be taught effectively;

ii. have a secure understanding of how a range of factors can inhibit pupils’ ability to learn and how best to overcome these; and

iii. have a clear understanding of the needs of all pupils, including those with SEN, those of high ability, those with English as an additional language, those with disabilities; and be able to use and evaluate distinctive teaching approaches to engage and support them.

Similarly, the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (APST), which prospective teachers must satisfy in order to obtain their ITE qualification, require prospective teachers to show that they have a solid understanding of diversity and inclusion in the classroom and are prepared to address diverse students’ needs and learning styles through differentiated instruction. They include specific standards relating to teaching students with SEN, as well as specifying what teachers should know and be able to demonstrate in relation to teaching Indigenous students and in terms of teaching Indigenous languages and culture to all students (AITSL, 2011[68]; OECD, 2017[18]; OECD, 2022[24]; Révai, 2018[69]). In Austria, student teachers must demonstrate that they have the pedagogical competences and knowledge to teach students with various needs in order to be able to graduate from the Upper Austria College of Education. Reflecting this, inclusive content is embedded in each subject of the ITE curriculum (UNESCO, 2020[66]).

More generally, the competence frameworks for ITE in Estonia and Latvia include skills and knowledge related to the development of co-operative learning environments based on student needs and abilities and the operationalisation of the values of tolerance and human rights (European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, 2017[57]; Brussino, 2021[16]).

While further research is required as to the effectiveness of this strategy, it is envisaged that the extent to which incorporating diversity and inclusion into competence frameworks influences ITE curricula in practice will depend on how clearly and specifically the standards or competences are framed.

Graduating teacher standards or competence frameworks may operationalise or reflect policy objectives for ITE that are defined at the system level (Brussino, 2021[16]). Several countries have developed explicit objectives for ITE that relate to preparing prospective teachers to respond to diversity and/or advance equity and inclusion (European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, 2017[57]). In Norway, for instance, the values of “equality and solidarity” and “insight into cultural diversity” are explicitly promoted within the National Framework Curriculum for Teacher Education, and the Education Act for Primary and Secondary Education and Training specifies diversity as one of the main objectives for ITE (Brussino, 2021[16]; European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, 2017[57]). The Teaching Council of Ireland also includes diversity and inclusion among the objectives it specifies for ITE in its “Initial Teacher Education: Criteria and Guidelines for Programme Providers” (Brussino, 2021[16]; The Teaching Council, 2017[70]). Less explicitly, the general objectives listed for ITE in the Netherlands include promoting prospective teachers’ understanding, respect and critical thinking (Brussino, 2021[16]; European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, 2017[57]).

Fostering equitable and inclusive teaching through continuous professional learning

Initial teacher education alone cannot fully prepare teachers for their profession (OECD, 2022[24]). Certain skills and pedagogical strategies are also better learnt in the classroom while teaching (Brussino, 2021[16]). Continuous professional learning enables teachers to refresh, develop and broaden their knowledge, and to keep abreast with evolving research and practices regarding equity and inclusion in education (OECD, 2022[24]). Researchers and international organisations have recognised the crucial value of continuous professional learning both in relation to teacher quality generally (LeCzel, 2004[71]; Leu, 2004[72]; O’Grady, 2000[73]; OECD, 2022[47]; OECD, 2019[45]) and more specifically in ensuring that teachers are able to meet diverse student needs and create environments that support all learners (UNESCO, 2017[74]). Continuous professional learning is also important to expand teachers’ skills and knowledge in a context of growing student diversity and in preparation for unforeseen events and developments, as was highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD, 2022[24]).

Formal continuous professional learning

Formal continuous professional learning related to diversity, equity and inclusion can be provided in a variety of ways, including through seminars, courses, workshops, conferences and online training, and may be delivered or supervised by a range of actors, including official government institutions, external private providers and non-governmental organisations (Brussino, 2021[16]). Examples of formal continuous professional learning on various specific dimensions of diversity can be found in several OECD education systems. In Italy, for example, teachers undertake in-service training on teaching students with SEN co‑designed by the Ministry of Education, University and Research in partnership with the particular school. Research institutes, scientific organisations, associations and local health authorities sometimes play a role in delivering some of the specific training activities (Brussino, 2021[16]; European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2021[75]). In New Zealand, Te Ahu o te Reo Māori is a three-month programme funded by the Ministry of Education and delivered by four external providers to develop teachers’ competencies in Indigenous language and in incorporating Indigenous language and culture in the classroom (Kral et al., 2021[76]). Following the programme’s pilot in 2020, participants reported significant improvements in their level of confidence in using Indigenous language in their everyday teaching and in their abilities to engage with Indigenous families and communities (Kral et al., 2021[76]). In Greece, the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs has partnered with the European Wergeland Centre (a resource centre established by the Council of Europe and Norway) to provide training for teachers as part of the project Schools for All – Integration of Refugee Students in Greek Schools (Koehler, Palaiologou and Brussino, 2022[14]; The European Wergeland Centre, n.d.[77]). Experienced trainers deliver training and provide mentoring throughout the school year to equip teachers and school leaders with the competences, tools and confidence to create safe and inclusive learning environments where refugee students are welcomed (The European Wergeland Centre, n.d.[77]).

Online training modules and courses are also offered in several OECD education systems to help prepare teachers and school staff to address diverse student needs and support all learners. In New Brunswick, Canada, an online continuous professional learning course on teaching in culturally and linguistically diverse settings is available to help equip teachers to implement inclusive pedagogy for students with an immigrant background, students belonging to ethnic or national minorities, and Indigenous students (Gottschalk and Weise, Forthcoming[58]). In England (United Kingdom), the government has developed an online portal to improve access to continuous professional learning material on teaching students with SEN, which includes a resource library with materials on teaching students with SEN in mainstream settings (Brussino, 2020[11]; United Kingdom Department for Education, 2014[78]). In addition to training related to specific dimensions of diversity, examples of online learning programmes addressing diversity, equity and inclusion more broadly can also be found in several education systems. Online training programmes have, for instance, been developed in the Flemish Community of Belgium and Sweden to encourage and support teachers to effectively use digital tools in the classroom to increase accessibility of learning opportunities and tailor learning to the specific needs of students (Gottschalk and Weise, Forthcoming[58]). In Italy and Spain, the Erasmus Training Academy offers online continuous professional learning courses for teachers on topics such as enhancing diversity and tolerance in the classroom, addressing prejudice and discrimination, preventing conflict and early school leaving, and promoting socio-emotional learning (Brussino, 2021[16]; Erasmus+ School Education Gateway, n.d.[79]).

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) can play a key role in some contexts in providing continuous professional learning regarding how teachers can support and serve the needs of specific diverse groups. Non-governmental organisations frequently develop training material and provide courses and programmes for teachers and school staff, sometimes funded by or in partnership with government or official institutions. In Portugal, for example, the National Association for the Study of and Intervention in Giftedness offers training courses to educational staff and supports school leaders and teachers in the implementation of personalised programmes for gifted learners (National Association for the Study and Intervention of Giftedness, n.d.[80]; Rutigliano and Quarshie, 2021[5]). Government departments in Ireland and Sweden have also collaborated with NGOs specialising in LGBTQI+ issues to develop seminars for teachers (Irish Department of Children and Youth Affairs, 2018[81]; McBrien, Rutigliano and Sticca, 2022[39]; Swedish National Agency for Education, 2022[82]), while, in France, several LGBTQI-focused NGOs have received official government accreditation to provide training for teachers (IGLYO, 2022[83]). There are also several examples of NGOs providing training to teachers in relation to addressing the needs of refugee students. The Support for Newcomer Education (Ondersteuning Onderwijs Nieuwkomers) programme run by the organisation LOWAN in the Netherlands, for example, includes the provision of training programmes in selected schools to equip teachers with the skills to be able to effectively welcome refugee and newcomer students, assess their needs and select the most appropriate teaching strategies. The programme is subsidised by the Dutch Ministry of Education (Koehler, Palaiologou and Brussino, 2022[14]).

While NGOs may have strong expertise with respect to the experiences of and issues faced by specific diverse groups and individuals, they may lack the requisite knowledge to effectively translate what these experiences and issues mean in terms of educational strategies and practices (Dankmeijer, 2008[84]; McBrien, Rutigliano and Sticca, 2022[39]). Partnerships between educational institutions or ministries and NGOs may therefore be more effective in terms of enabling teachers and school staff to benefit from the particular expertise provided, though further research is required in this respect. Collaboration between NGOs and central or local authorities can also foster the upscaling of effective programmes (see Chapter 6). This has been identified as one of the key elements, for instance, in the upscaling and/or institutionalisation process of inclusive education initiatives for refugee and newcomer students, including the LOWAN programme referred to above (Koehler, Palaiologou and Brussino, 2022[14]).

Supporting teachers’ participation in continuous professional learning

To ensure all teachers are able to improve their knowledge and skills for equitable and inclusive teaching, it is important to address barriers that may hinder or discourage participation in continuous professional learning (OECD, 2022[24]). This may be particularly crucial in education systems where continuous professional learning is not mandatory for teachers.1 Two important aspects in this respect are ensuring that teachers have dedicated time to engage in continuous professional learning and that financial costs do not hinder or discourage them in doing so (OECD, 2022[24]; OECD, 2022[47]). In the French Community of Belgium, teachers are entitled to take six half-days of working time per year to engage in continuous professional learning (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2021[85]). Similarly, in Victoria, Australia, each teacher is entitled to four dedicated days per year to engage in continuous professional learning to improve their teaching (OECD, 2022[24]). School-wide professional learning days have also been implemented in several OECD education systems as a way to ensure dedicated time to professional learning, to complement teachers’ self-directed or individual learning, and to advance school improvement (ibid.). In New Zealand, for instance, the most recent collective agreement between the government and the main teaching unions provides for eight “Teacher-Only Days” during term time, which are supported by guidelines and resources developed at the national level (OECD, 2022[24]). In terms of addressing potential costs associated with continuous professional learning, Norway provides financial support to teachers engaging in professional learning on priority topics as part of a new model for teachers’ in-service competence development that was introduced in 2017 (Boeskens, Nusche and Yurita, 2020[86]).

Seeking teachers’ feedback and views and monitoring their progress and participation is crucial to ensure that the training that is offered meets their needs and is effective in equipping them to create equitable and inclusive learning environments in a context of increasing diversity. Teacher questionnaires can be a useful tool in assessing teachers’ needs and how well prepared they feel to implement inclusive teaching practices. The TALIS questions concerning teachers’ feelings of self-efficacy in teaching in a multicultural setting could be expanded to consider other dimensions of diversity and used by schools as teacher self-evaluation tools to prompt reflection on their abilities and areas of need for further training (Mezzanotte and Calvel, Forthcoming[87]). In Alberta, Canada, for example, tailored questions on teachers’ feelings of preparedness regarding teaching Indigenous curriculum content were added to the OECD 2013 TALIS survey (OECD, 2017[18]). Research has shown that giving teachers opportunities to influence the substance and process of professional learning can also help to facilitate a sense of ownership and enable teachers to connect what they have learnt to the specific context of their school (Forghani-Arani, Cerna and Bannon, 2019[15]; King and Newmann, 2000[88]). In light of this, it is important to give teachers a say in shaping both the types of programmes that are offered and their professional learning pathway, through, for instance, ensuring representation of active teachers on the relevant body or bodies that set the professional learning offering (OECD, 2022[24]). Teachers should further be supported to effectively transfer and assimilate the new ideas and knowledge they have acquired through continuous professional learning into their classroom practice (ibid.). An inclusive school leadership and management that promotes a culture of collaboration (see below) plays a crucial role in this respect.

Collaborative approaches to support teachers in creating inclusive learning environments

In addition to more formal continuous learning programmes and projects, horizontal and collaborative continuous professional learning initiatives bringing together evidence-informed pedagogical theories and classroom practices are also emerging in some OECD education systems as a way of preparing and supporting teachers to foster equitable and inclusive learning environments (Brussino, 2021[16]). If implemented effectively and well-supported, collaboration can lead to increased teacher job satisfaction and improve teachers’ capacity for equitable and inclusive teaching through the transferring and sharing of knowledge and experiences (OECD, 2022[24]; OECD, 2022[47]). Alberta and Ontario in Canada are two examples of education systems where in-school collaboration is actively promoted and implemented through a range of activities (Box 4.1).

Box 4.1. Fostering in-school collaboration in Alberta and Ontario (Canada)

Alberta

The Alberta Teachers’ Association, which plays a key role in teachers’ continuous professional learning, has shifted its focus from individualised professional learning to more collaborative school-based activities that foster co-operation and encourage critical reflection. Some of the activities facilitated or proposed by the Association as part of this include:

Action research: This involves teachers asking how a current practice might be improved and then studying the relevant research to select a potential approach. Teachers use their classrooms as research sites by investigating their own teaching through experiments to see what is effective in facilitating co-operative learning among students.

Classroom and school visits: Teachers are encouraged to visit colleagues teaching in other classrooms to view innovative teaching practices, and expand and refine their own pedagogical strategies.

Collaborative curriculum development: By working together, teachers design new planning materials, teaching methods, resource materials and assessment tools, and they can delve deeply into their subject matter.

Ontario

As part of its efforts in supporting teacher collaboration, the Ontario Ministry of Education has produced a series of “Capacity Building” briefs that share actionable strategies that teachers and school leaders can implement to improve their practice. The Ministry promotes a process of “collaborative inquiry” in which teachers work with other teachers from their school to research problems of practice. In teams, teachers generate evidence of what is and is not working at their school, make decisions about interventions, take action and then evaluate the effectiveness of their intervention before repeating the cycle. Teachers are encouraged to participate in a range of learning activities applying this process. These include:

Co-teaching classes: In small groups, teachers work together to plan a lesson and then co‑teach that lesson with assigned roles, reflecting on the student learning outcomes of the learning experience, including naming evidence of the impact on student learning.

Collaboratively assessing student work: Teachers collaboratively discuss student work based on common assessment criteria.

Monitoring marker students: Teachers pick a small number of students in a class, grade or school, share their assessment results with others in the school, and document the use of teaching strategies against the learning outcomes for these students.

Sources: The Alberta Teachers’ Association (2022[89]), PD Activities for Professional Growth, https://www.teachers.ab.ca/For%20Members/ProfessionalGrowth/Section%203/Pages/Professional%20Development%20Activities%20for%20Teachers.aspx (accessed 8 June 2022); Nusche, et al. (2016[90]), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Denmark 2016, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264262430-en; Ontario Ministry of Education (2014[91]), Capability Building Series: Collaborative Inquiry in Ontario, https://thelearningexchange.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2017/02/CBS_CollaborativeInquiry.pdf (accessed 22 November 2018); Deming (2018[92]), The New Economics: For Industry, Government, Education, MIT Press.

Collaborative approaches can play an important role in supporting equitable and inclusive teaching practices through promoting the sharing of knowledge and strategies among teachers (Brussino, 2021[16]; OECD, 2022[47]). In particular, “professional learning communities” can serve as effective tools in supporting the development of teachers’ knowledge and competences to address and support all students’ needs by providing informal environments for mutual learning and reflection (Alhanachi, de Meijer and Severiens, 2021[93]; Brussino, 2021[16]; Lardner, 2003[94]). The Life is Diversity (Leben ist Vielfalt) network, for instance, was initiated by pre- and in-service teachers in the North Rhine‑Westphalia region of Germany and organises regular workshops, seminars and meetings for teachers on topics such as addressing unconscious bias, intercultural classroom teaching strategies and multilingualism in the classroom. Feedback received indicates that stakeholders consider that the network has had positive impacts in terms of increasing teachers’ intercultural sensitivity as well as their preparedness and self-confidence to teach in diverse classrooms (Cerna et al., 2019[64]; European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, 2017[57]; Universität Paderborn (Paderborn University), 2016[95]). Similarly, “On the Shoulders of Giants” is a bottom-up professional learning community initiated by a group of teachers in Valencia, Spain, that organises monthly seminars where teachers come together to discuss research and share their experiences on strategies to improve students’ learning. Data collected as part of an evaluation suggested that participating in the programme had improved teachers’ practices and attitudes towards continuous professional learning, as well as encouraging collaboration and knowledge sharing among teachers (Rodriguez, 2020[96]). In New Zealand, Communities of Learning is a country-wide initiative in which schools work together to develop educational environments’ that are responsive to students’ different learning paths and promote equitable education outcomes for Indigenous students and students with SEN (Annan and Carpenter, 2015[97]; OECD, 2017[18]).

Collaborative teaching is another professional learning strategy that can support teachers in addressing and serving diverse students’ needs. Collaborative teaching has traditionally involved general education teachers working in tandem with special education teachers (Varsik and Gorochovskij, Forthcoming[50]). This strategy utilises the presence of a special education teacher to assist in planning lessons, teaching or evaluating student progress, while holding all students to the same educational standards. While all students learn the same content, teachers have more leeway to address students’ specific needs (Morin, n.d.[98]; Varsik and Gorochovskij, Forthcoming[50]). The Federation University in Australia offers a resource pack for teachers who wish to adopt this teaching style with a colleague, providing guidance on how to formulate clear teaching team roles and responsibilities, develop effective communication strategies to maximise teaching, and identify complexities and variables in managing team workflows (Federation University, 2022[99]; Varsik and Gorochovskij, Forthcoming[50]). For students with SEN, being in a co-taught classroom can be beneficial as it allows students to spend more time with and receive more individual attention from teachers (Mezzanotte, 2020[12]; Morin, 2019[100]). Beyond addressing SEN, collaborative teaching partnerships have also been implemented to help prepare and support teachers in teaching Indigenous language and culture. In Chile, for example, collaborative teaching is a strategy adopted as part of the country’s Programme for Intercultural Bilingual Education to incorporate Indigenous language subjects into the curriculum. Schools form a pedagogical team made up of a traditional teacher and a mentor teacher, with the former bringing knowledge of Indigenous language and culture and the latter providing pedagogical skills and knowledge of the educational system (Santiago et al., 2017[101]).

Dedicated advisory or support workers can provide valuable support and guidance to teachers and school leaders in supporting the learning and well-being of diverse students. Learning support teachers are, for instance, used in several education systems to support students with SEN. Support teachers focus on the provision of supplementary teaching to students who require additional help (Mezzanotte, 2020[12]). Cultural mediators with a Roma background are also employed in a number of European countries to both support and increase the performance of Roma students and improve their well-being, as well as to build trust and sustained relationships between schools and Roma families (Rutigliano, 2020[102]). Similarly, an increasing trend in Chile is the use of language facilitators to provide mother tongue language support in mainstream classrooms and to facilitate relationships between schools and parents and guardians who may not speak Spanish (Guthrie et al., 2019[103]). In Canada, dedicated Indigenous support staff work directly with teachers on their teaching strategies and practices, lead improvements in the curriculum and learning activities to build cultural competencies, and serve as a connecting point with Indigenous parents (OECD, 2017[18]).

To be effective, collaborative initiatives both within and across schools need to be supported by both pedagogical leadership and resources (OECD, 2022[24]). This can be facilitated at the system level through, for instance, regulating teachers’ working time in a way that provides space for collaborative learning, funding or additional staff resources, and/or official guidance (ibid.). In Austria, for instance, the New Secondary School Reform has led to a variety of measures to facilitate and support teachers’ collaboration. These include the creation of new roles within schools and the introduction of a team teaching approach, which, in addition to allowing teachers within schools to learn from each other by working together, enables teachers from different schools and education levels to come together and share best practices (Nusche et al., 2016[90]; OECD, 2022[24]). Korea also encourages the sharing of knowledge among teachers by funding action research by teachers and counting these efforts towards their professional development requirements. Funding is made available to individual schools and to groups of teachers from across several schools who wish to undertake joint research (OECD, 2014[104]). In Australia, the Department of Education and Training in the state of Victoria has developed guidelines and resources to support schools in developing professional learning communities to facilitate teachers’ and school leaders’ engagement in team learning. These include a Framework for Improving Student Outcomes, which encourage teachers and school leaders to make use of student learning data to design and implement differentiation strategies to support individual students’ needs (Brussino, 2021[16]; State of Victoria Department of Education, 2020[105]).

Designing and implementing teacher evaluation for equitable and inclusive teaching

Using teacher evaluation to promote and support teachers’ learning

Teacher evaluation processes can serve as a key tool in preparing and supporting teachers to address the needs of all learners and promote equity and inclusion in education. To enable them to fulfil this function, it is important that they are designed and implemented in a way that supports and encourages teachers to acquire the competences and knowledge necessary for equitable and inclusive teaching (Brussino, 2021[16]). Frameworks for teacher evaluation in relation to diversity, equity and inclusion are, however, currently lacking in many education systems across the OECD (Brussino, 2021[16]). More generally, data from the TALIS 2018 survey suggest there is a need across the OECD to improve teacher evaluation processes so that they better support and promote teachers’ learning and development, as only 55% of teachers who had reported receiving feedback considered that it had led to a positive change in their competencies (OECD, 2019[45]).

Clear and well-structured teaching standards are a powerful mechanism to define what constitutes good teaching and to align the various elements involved in developing teachers’ knowledge and skills (OECD, 2005[106]), and can thus serve as a reference point for school-level teacher evaluations (Révai, 2018[69]; OECD, 2022[24]). Incorporating competences and knowledge related to diversity, equity and inclusion into teaching standards is therefore a key strategy to ensure that teacher evaluations are more effective as a tool in preparing and supporting teachers for inclusive teaching. New Zealand and Australia offer examples of how diversity and inclusion can be incorporated into teacher professional standards and, more broadly, of how teacher appraisal processes can be designed and implemented to support and promote teachers’ professional learning (see Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Standards to promote teachers’ professional learning in Australia and New Zealand

Australia: Professional Standards for Teachers and Teacher Self-Assessment Tool

The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (APST) inform teachers’ voluntary certification for advanced teaching career stages and provide a framework to assist in planning teachers’ on-going professional learning. The APST consist of seven standards, which teachers have to meet at different levels (graduate, proficient, highly accomplished and lead), depending on their career stage and level of experience. Within each Standard, focus areas set out what teachers are required to demonstrate in terms of knowledge, practice and professional engagement. Some of the focus areas specifically concern what teachers are required to show to support the inclusion of diverse students, including students with diverse linguistic, cultural, religious and socio-economic backgrounds; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students; and students with disabilities. More broadly, the APST also contain specific standards in relation to differentiated teaching and the creation of inclusive learning environments.

New Zealand: Professional Growth Cycle for Teachers

In early 2021, New Zealand began to implement the Professional Growth Cycle for Teachers in substitution of its former teacher performance appraisal system. Through a holistic approach centred on professional growth and school-staff collaboration, the cycle aims to focus how teachers meet and implement the Code of Professional Responsibility and Standards for the Teaching Profession in their daily teaching practices. The Standards include developing a culture “characterised by respect, inclusion, and empathy”, understanding each student’s “strengths, interests, needs, identities, languages and cultures”, and implementing adaptive teaching. School leaders design teachers’ annual cycle of professional growth based on the Standards (in collaboration with the teacher) and support teachers in engaging with the professional growth cycle throughout the school year. School leaders provide teachers with a statement at the end of the school year as to whether they meet these standards and support teachers in the areas identified for improvement.

Sources: Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (n.d.[107]), Understand the Teacher Standards, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards/understand-the-teacher-standards (accessed 13 April 2022); Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (n.d.[108]), Documentary evidence examples – Proficient teachers, Education Services Australia https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/defaultsource/general/documentary_evidence_proficient_teachers.pdf?sfvrsn=d90ce33c_0 (accessed 09 June 2022); Teaching Council of Aotearoa New Zealand (2021[109]), Professional Growth Cycle, https://teachingcouncil.nz/faqs/faqs-professional-growth-cycle/ (accessed 09 June 2022).

Researchers in the United States, together with the American Federation of Teachers and five school districts, have developed a set of principles that can serve as a basis for reflection on how evaluations can be designed in a way that promotes teachers’ development with respect to equitable and inclusive teaching practices (Brussino, 2021[16]; Fenner, Kozik and Cooper, 2017[110]).

i. Committing to equal access for all students: Teachers know and share the laws and regulations to provide full and equal access to public education for all. Teachers outline the needs of all students, including those with unique learning needs, and how these needs are included and met in the classroom.

ii. Preparing to support diverse students: Teachers show knowledge and understanding of individual students’ experiences and identities, and value diversity as an asset. Strategies to support individual needs and learning styles are implemented along the rationale of individualisation included in the Universal Design for Learning (see Chapter 5).

iii. Evidence-based reflective teaching: Teaching practices are adapted to students’ needs and identities through individualised, student-centred approaches. These are appropriately challenging and founded upon evidence-based practices.

iv. Promoting a collaborative classroom environment with a sense of community: Teachers engage in creating active and solid partnerships with diverse stakeholders, including students, families, teachers and other community services.

Classroom observation and post-observation feedback can be effective in improving teachers’ teaching practices, both through enabling teachers to receive post-observation feedback from peers and to learn by observing other teachers (Brussino, 2021[16]; Hendry, Bell and Thomson, 2014[111]). Peer observation can be particularly important in supporting the development of equitable and inclusive teaching strategies among teachers, and for this reason is a common feature of professional learning communities (Brussino, 2021[16]). Despite growing interest in peer observation, observing other teachers and providing post‑observation feedback is not yet a mainstream practice across OECD countries (ibid.). Indeed, on average across OECD countries, only 15% of teachers in PISA 2018 reported providing feedback based on their observation of other teachers more than four times per year (OECD, 2020[46]). There are, however, examples of policies and practices to promote peer observation in some OECD education systems, which can be useful in informing the further development and facilitation of peer observation processes among teachers (Brussino, 2021[16]). In Canada, for instance, the University of Toronto has developed guidelines to mainstream peer observation across its faculty members, which include “Creating an inclusive classroom” as one of the key observation areas. The guidelines set out how different peer observation models can be used to assess various aspects of teaching in terms of diversity and inclusion (Brussino, 2021[16]; Centre for Teaching Support & Innovation, 2017[112]). The Department of Education and Training in Victoria, Australia, has also published a guide to support the implementation and embedding of peer observation in schools, in line with its focus on creating a culture of working collaboratively to continuously improve teaching and learning (State of Victoria Department of Education and Training, 2018[113]). As a starting point for planning peer observations, the guide sets out a series of instructional strategies thar promote student learning which include “differentiated teaching to extent the knowledge and skills of every student in the class, regardless of their starting point” (ibid.).

Ensuring teachers are fairly evaluated

A further issue to be addressed in relation to teacher evaluation is the fact that evidence indicates that diverse teacher groups and teachers working in disadvantaged schools tend to score disproportionately lower in teacher evaluations (Bailey et al., 2016[114]). This can involve a degree of rater or evaluator bias (i.e., the tendency of raters to be influenced by non-performance factors when rating), which has long been recognised as an issue in teacher evaluation or appraisal processes (Milanowski, 2017[115]). Evaluators’ perceptions of teacher performance may, for instance, be influenced by stereotypes or preconceptions regarding certain groups or by the socio-economic profile of the students being taught (ibid.). Tying teacher performance ratings to student performance is another issue in teacher evaluation processes that raises concerns from an equity perspective. As students’ socio-economic status impacts on their academic performance (Ikeda, 2022[116]), tying teacher ratings to student performance can discriminate against teachers working in disadvantaged schools (Brussino, 2021[16]; Newton et al., 2010[117]), in which, as discussed above, teachers from diverse backgrounds are often over-represented. As teacher evaluation can affect tenure, progression and pay, bias in teacher evaluation processes can further be a driver in teacher turnover (Johnson, 2015[118]; Brussino, 2021[16]) and thus impact on the diversity and inclusivity of the teacher workforce.

Further research is needed regarding strategies that are effective in addressing evaluators’ bias in teacher evaluation processes (Brussino, 2021[16]). Training teacher evaluators on how to recognise and address conscious and unconscious bias in the classroom is, however, likely to be a key element. Avoiding bias and reporting evidence in an objective manner are among the areas on which prospective evaluators are trained and assessed in the Cincinnati Public Schools District in Ohio, the United States. Prospective evaluators complete a rigorous training programme, which includes undertaking live teacher evaluations in partnership with a qualified mentor (Leahy, 2012[119]).

Addressing equity issues associated with tying teacher evaluation to student performance is complex, with diverse factors falling to be considered. One potential strategy to improve fairness towards teachers working in more disadvantaged settings is to adjust evaluation ratings depending on classroom composition characteristics (Milanowski, 2017[115]). The National System for Performance Evaluation in Chile (Sistema Nacional de Evaluación de Desempeño), for example, is structured in a way that takes into account the characteristics of the school in determining the financial awards for teachers (Brussino, 2021[16]; Santiago et al., 2017[101]). The System evaluates school performance on a range of specified, weighted factors, and rewards teachers and education assistants working in schools that perform well. To ensure greater fairness, schools in each region are ranked within groups of schools that are considered broadly comparable. The variables that are used to define the groups are: geographical area (urban or rural), level and type of education, position on the Schooling Vulnerability Index, average household income of students’ families, and the average schooling level of students’ parents or guardians (Santiago et al., 2017[101]).

Building capacity among school leaders to promote equity and inclusion

School leaders are key actors in shaping the ethos of schools and in ensuring that policies and legislation for equity and inclusion in education are carried into effect through practices tailored to the local context of the school and community (Cerna et al., 2021[1]; European Agency for Special Education Needs and Inclusive Education, 2021[120]; OECD, 2017[18]). From an equity perspective, school leadership has been recognised as an important factor in influencing student learning outcomes (OECD, 2022[2]), and the starting point for improving student achievement in disadvantaged schools (OECD, 2012[25]). School leadership also plays a crucial role in the development and implementation of inclusive instructional programme, as well as in creating collaborative school environments that promote inclusive teaching practices and serve the needs of all students (Brussino, 2021[16]; European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2020[121]; UNESCO, 2020[122]; OECD, 2022[24]). Indeed, an international literature review found that schools with inclusive cultures tended to have leaders who were “committed to inclusive values and to a leadership style that encourages a range of individuals to participate in leadership functions” (Ainscow and Sandill, 2010[123]).

Particular forms of leadership have been recognised as being effective in promoting equity and inclusion in schools through facilitating “more powerful forms of teaching and learning, creating strong communities of students, teachers and parents, and nurturing educational cultures among families” (Ainscow and Sandill, 2010[123]). The Supporting Inclusive School Leadership project developed by the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education identified three core functions of “inclusive school leadership” (i.e. leadership that promotes equity and inclusion in education) (European Agency for Special Education Needs and Inclusive Education, 2021[120]; European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2018[124]):

Setting direction. This involves identifying and articulating a shared vision of inclusive education, setting expectations for staff and building acceptance of group goals in line with this vision, monitoring performance, and communicating with stakeholders.

Organisational development. This involves creating and facilitating professional learning opportunities, supporting and motivating teachers, facilitating reflective practice, and focusing on learning.

Human development. This involves creating and sustaining an inclusive school culture, developing collaborative practices, building partnerships with parents and the community, and distributing leadership roles.

According to the Supporting Inclusive School Leadership project, these core functions translate into a number of specific roles and responsibilities at the individual, school, community and system levels. These are set out in the table below (European Agency for Special Education Needs and Inclusive Education, 2021[120]).

Table 4.1. School leadership roles and responsibilities to promote equity and inclusion

|

Individual level |

School level |

Community level |

System level |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Support innovative and evidence-based pedagogies and practices in the classroom |

Guide and influence the organisation of school resources in ways that promote equity |

Build partnerships with support agencies and other schools in the community |

Influence the development of system-level policies on equity and inclusion in education through consultation and communication |

|

Monitor classroom practices |

Engage the school community in self-review processes and reflect on data to inform on-going school improvement |

Build school capacity to respond to diversity through research engagement and collaborative professional development activities (for example, with universities) |

Translate and implement policies in ways appropriate to the particular school context, and manage school-level change relating to curriculum and assessment frameworks, professional development, funding and resource allocation, and quality analysis and accountability |

|

Develop a culture of collaboration through promoting positive and trusting relationships |

Provide and facilitate professional learning opportunities for school staff |

Foster a sense of commitment to a shared vision of inclusion |

|

|

Use data to inform teachers’ on-going professional learning |

Ensure the curriculum and student assessment processes meet the needs of all learners |

Manage financial resources to meet the needs of the whole school community |

|

|

Promote learner-centred teaching practices |

Ensure that both staff and learners feel supported |

||

|

Actively engage all families |

Source: Adapted from European Agency for Special Education Needs and Inclusive Education (2021[120]), Supporting Inclusive School Leadership: Policy Messages, https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/SISL%20Policy%20Messages-EN.pdf (accessed 16 December 2022).

UNESCO has also emphasised the importance of school leaders being able to build consensus and a sense of commitment among the school community for implementing the values of equity and inclusion, and to establish an environment where stakeholders feel able to challenge discriminatory, inequitable and non-inclusive educational practices (OECD, 2022[47]; UNESCO, 2017[74]). This requires them to be able to analyse their own contexts, identify local barriers and facilitators, and to foster collaboration among school staff, among other competences. Previous OECD work has further highlighted the need for school leaders to be equipped with the specialised competences and knowledge necessary to drive the improvement of student learning outcomes in disadvantaged schools (OECD, 2012[25]). These knowledge and competence areas include factors influencing student motivation and achievement, effective teaching strategies for disadvantaged and/or low performing students, fostering a positive and caring school culture, and engaging parents or guardians and the wider community as active allies for school improvement (OECD, 2012[25]).

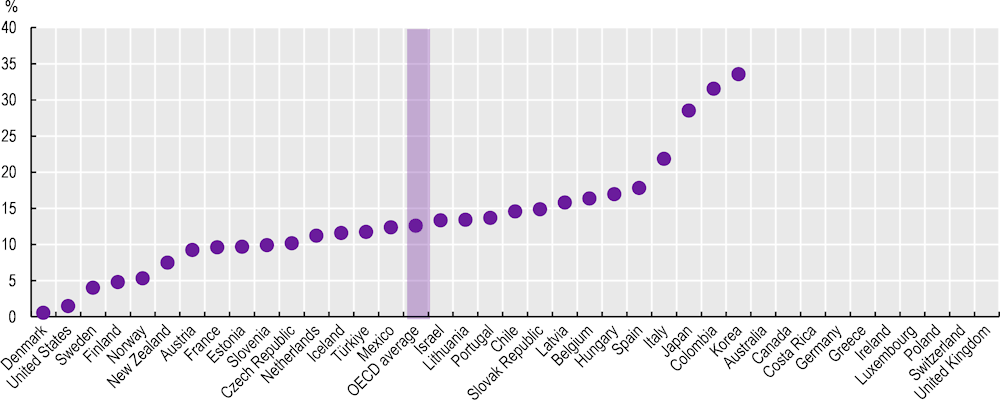

To develop the knowledge and competences required to be able to promote equity and inclusion in education, school leaders need access to professional learning and resources, along with the support of and opportunities to collaborate with colleagues and other stakeholders (European Agency for Special Education Needs and Inclusive Education, 2021[120]). The OECD TALIS 2018 survey included a question on lower secondary school leaders’ perceived need for professional development for “promoting diversity and equity”. As shown in Figure 4.3 below, 13% of school leaders on average across the OECD reported a need for professional development in this area, though with variation across countries. 26% of school leaders (on average across the OECD) also reported a high need for professional development in developing collaboration among teachers and 24% reported a high need for training in using data for school improvement - (OECD, 2019[45]) – both of which have been identified among the roles and responsibilities of school leaders in promoting equity and inclusion in education (see Table 4.1) (European Agency for Special Education Needs and Inclusive Education, 2021[120]; UNESCO, 2020[122]).

Figure 4.3. Percentage of lower secondary school leaders reporting professional development needs for promoting diversity and equity

Source: OECD (2020[125]), TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II): Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals, Table I.5.32, https://doi.org/10.1787/19cf08df-en.

The School Leadership Toolkit published by the European Policy Network on School Leadership also notes that equity considerations are “relatively neglected” in school leadership training programmes, and emphasises the importance of redesigning school leaders’ initial education and on-going learning curricula and activities to better “integrate methods and techniques for promoting fairness and inclusion in school practice” (European Policy Network on School Leadership, 2015[126]). In this vein, the Toolkit proposes a set of five general principles for designing training programmes and activities so as to build school leaders’ capacity for promoting equity and inclusion (European Policy Network on School Leadership, 2015[126]):

School leadership programmes and activities should seek to develop school leaders’ capacity for evidence-based critical reflection on the conditions and factors influencing teaching, learning and equity in the local context of their schools.

School leadership programmes and activities should seek to promote a holistic approach to school leadership, which includes the attainment of both equity and learning goals.

School leadership programmes and activities should stimulate the recognition of and reflection on diversity in students’ perspectives, experiences, knowledge, values and ways of learning.

School leadership programmes and activities should “[t]arget whole school leadership capacity building, focusing on democratic, collaborative and innovative school leadership methods”.