This chapter explores how different interventions at the school level can be leveraged to advance equity and inclusion in education, and support all students in the classroom. The Strength through Diversity project has identified five broad categories of school-level interventions: (i) matching resources within schools to students’ learning needs; (ii) school climate; (iii) learning strategies to address diversity; (iv) non-instructional support and services; and (v) engagement with parents and the community. This chapter discusses each of these categories in turn, before concluding by setting out some pointers for policy development.

Equity and Inclusion in Education

5. Promoting equity and inclusion through school-level interventions

Abstract

Introduction

Education systems’ policies can create an equitable and inclusive framework for education settings (Chapter 2), but their implementation at the school level is what determines students’ daily experiences in classrooms. It is in schools where policies take the form of specific resources, teaching practices and instructional and non-instructional support mechanisms.

Numerous interventions at the school level are needed to promote equity among and the inclusion of all students, and in particular students from diverse backgrounds or embodying particular dimensions of diversity. Without explicit attention by schools to the needs of and challenges experienced by these students, their ability to reach their full potential may be hindered. Conversely, careful, targeted approaches are important to help all students feel that they belong at school, can improve their well-being and sense of motivation, and provide increased opportunities for academic success.

The Strength through Diversity project has identified the following five categories of school-level interventions that can be leveraged to foster equity among and the inclusion of all students:

Matching resources within schools to individual student learning needs;

School climate;

Learning strategies to address diversity;

Non-instructional support and services;

Engagement with parents and communities.

This chapter is organised into seven sections. After this introduction, it explores each of the above five categorised in turn, discussing how various interventions can help support the well-being and educational outcomes of all learners. It concludes by setting out some pointers for policy development.

Matching resources within schools to individual student learning needs

While central authorities often provide targeted (and, at times, earmarked) resources to support equity and inclusion efforts in schools, schools in many education systems across the OECD also have some authority over the allocation of the resources they receive (OECD, 2021[1]). Indeed, over the past three decades, many education systems, including those in Australia, Canada, Finland, Israel, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom, have granted their schools greater autonomy in both curricula and resource allocation decisions (OECD, 2017[2]). In 2015, PISA (2016[3]) asked school principals to report on the actors and bodies (teachers, principals, regions, local education authorities, national education authority) responsible for resource allocation decisions concerning their school (such as appointing and dismissing teachers; determining teachers’ starting salaries and salary rises; and formulating school budgets and allocating them within the school). It found that, on average across OECD countries, 39% of the responsibility for school resources resided with principals, 3% with teachers, 12% with school boards, 23% with local or regional authorities, and the remaining 23% with national authorities (OECD, 2016[3]). These results showed that local educational levels, and schools in particular, generally have responsibility for managing resources for their student population. As a result, these schools are responsible for resource policy issues, including concerns relating to an equitable and inclusive allocation of available resources. In terms of vertical equity1, this can concern addressing the needs of particular students attending the school, ensuring that disadvantaged students receive the necessary support to thrive.

Financial resources, however, are just one of many resources that schools can manipulate to serve their student populations, as mentioned in Chapter 3. The following section provides examples of various resources that can be leveraged directly by schools to address the needs of their students.

Allocating support staff within schools

Learning support staff, such as teaching assistants, can play a key role in supporting the work of teachers and in ensuring that all learners have the ability to achieve their educational potential. Research suggests that, if used effectively, learning support staff can contribute to improved student well-being and learning outcomes (Masdeu Navarro, 2015[4]). The presence of an additional professional in the class can, for instance, mean that students receive more individual help and attention during the lesson, from either the learning support staff member or the teacher. This can mean that students’ learning needs are more likely to be met, which in turn can lead to improved learning outcomes (ibid.). The effective use of learning support staff may also facilitate a more flexible learning environment that can contribute to increased engagement and inclusion of students in learning activities (for example, through allowing students to be grouped in ways that responds to different learning needs for particular classroom activities) (ibid.).

Studies have found that learning support staff can be effective at improving attainment when used to support specific students in small groups or through structured interventions (Masdeu Navarro, 2015[4]). In England (United Kingdom), for instance, two randomised control trials – one of a literacy programme targeted at lower secondary school students identified as struggling in literacy and the other of a one‑to‑one mathematics support programme for primary school students – found significant improvements in students’ learning in literacy and numeracy as a result of learning support staff intervention programmes. A large‑scale randomised control trial conducted in Denmark analysing the effects of the use of a learning support staff member on Grade 62 students’ achievement also found positive effects on student reading achievement, particularly among students with less educated parents (defined as both parents having, at most, ten years of schooling) (Andersen et al., 2014[5]). An evaluation of 44 pilot programmes of an initiative of the Denmark Ministry of Education to improve the academic achievement of low performing and disadvantaged students also indicated a positive impact of support staff on students’ well-being,3 particularly for the most disadvantaged students (Masdeu Navarro, 2015[4]).

The Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022 found that most education systems allocated learning support staff (such as teaching assistants) to support students with SEN. However, they can also be used to support the learning of other diverse students. For instance, a number of education systems (such as Australia, Finland and the United Kingdom) use bilingual assistants to support the specific language needs of students whose first language is not the language used by the school (Ministry of Finance of the Slovak Republic, 2020[6]).

Learning support staff may be used in various ways in the classroom. One model is co-teaching, which is where the classroom teacher works collaboratively with an assistant in planning and teaching lessons, with the objective of jointly delivering instruction in a way that meets the needs of all learners (Masdeu Navarro, 2015[4]; Mezzanotte, 2020[7]; Morin, 2019[8]). While this approach has its roots in special education, it is now employed in a variety of subjects across all levels of education (Masdeu Navarro, 2015[4]). It is, for instance, used as an approach in some education systems to support students whose first language is not that used by the school (Guthrie et al., 2019[9]; Masdeu Navarro, 2015[4]). Co-teaching has also been implemented in Chile and Canada to support the teaching of Indigenous language and culture (see Chapter 4) (OECD, 2017[10]; Santiago et al., 2017[11]). Co-teaching can be beneficial for students in that it allows them to spend more time with and receive more individual attention from teachers (Mezzanotte, 2020[7]; Morin, 2019[8]). Indeed, the literature suggests that co-teaching can result in a more effective teaching and learning environment, an increased understanding of students’ needs and a greater exchange of knowledge and teaching strategies among professionals (Dieker, 2001[12]; Dieker and Murawski, 2003[13]; Masdeu Navarro, 2015[4]). Co-teaching may also contribute to enhanced student engagement: a study analysing the effects of co-teaching in primary school science classes by specialist science student teachers and general teachers found positive effects on students’ enjoyment of the classes. Moreover, it also found fewer age or gender differences in attitudes to science than children (when compared with students who had not participated in the project) (Masdeu Navarro, 2015[4]; Murphy et al., 2004[14]). Co-teaching involving language assistants has also been recognised as beneficial in terms of improving student motivation, participation and cross-cultural understanding (Masdeu Navarro, 2015[4]).

Box 5.1. Multidisciplinary teams to support inclusion in Portugal

In Portugal, legislation requires that each school have a multidisciplinary team, known as an Equipa Multidisciplinar de Apoio à Educação Inclusiva, to support the inclusion of students who may be facing difficulties and who require additional support. The permanent members of each team are a special education teacher, an assistant of the school director, the school psychologist and three members of the school’s pedagogical council. In addition, teams include variable members, who are chosen depending on the student in question, as well as the student and their parents or guardians.

These teams are responsible for:

Raising awareness of inclusive education in their educational community;

Proposing learning support measures to be mobilised;

Following-up and monitoring the implementation of learning support measures;

Advising teachers about the implementation of inclusive pedagogical practices;

Preparing technical-pedagogical reports, individual education plans and transition plans; and

Monitoring and following-up on the functioning of learning support centres.

Source: OECD (2022[15]), Review of Inclusive Education in Portugal, Reviews of National Policies for Education, https://doi.org/10.1787/a9c95902-en

Class size

In some OECD countries, there is some flexibility in the organisation of class size in relation to the diverse composition of the student population. For instance, PISA finds that on average across OECD countries, socio-economically disadvantaged schools had more frequently smaller language-of-instruction classes compared to advantaged schools, as did rural schools compared to urban ones. Class size has been recognised as, in theory, a factor having the potential to impact on student learning – though research on this point is inconclusive (OECD, 2016[3]; OECD, 2019[16]). In smaller classes, teachers might be able to allocate more time and dedicated support to each student, whereas in larger classes some students may become disengaged due to their learning needs not receiving sufficient attention (OECD, 2019[16]). Findings from PISA 2015 show that students in schools with smaller class sizes were “more likely to report that their teachers adapt their lessons to students’ needs and knowledge, provide individual help to struggling students, and change the structure of the lesson if students find it difficult to follow” (OECD, 2019[16]). There are also several studies that indicate that smaller classes can improve student outcomes and might be more beneficial for students from disadvantaged or minority backgrounds (Andersson, 2007[17]; Björklund et al., 2004[18]; Dynarski, Hyman and Schanzenbach, 2013[19]). Overall, however, the empirical evidence on the effectiveness of policies to reduce class size on students’ academic outcomes is mixed (OECD, 2019[16]). While several studies using robust methodologies suggest that smaller classes may be of particular benefit to primary school pupils (Fredriksson, Öckert and Oosterbeek, 2012[20]; Chetty et al., 2011[21]; Vaag Iversen and Bonesrønning, 2013[22]), with some exceptions (Hoxby, 2000[23]), the evidence is less certain in the case of lower and upper secondary students, with large differences across countries (OECD, 2019[16]; Wößmann and West, 2006[24]). In general, the evaluation of the causal link between class size and performance is complicated by the fact that, in several contexts, disadvantaged schools have lower student-teacher ratios, which means it cannot be determined whether an observed performance outcome is the result of school composition (disadvantaged students often perform worse than their more advantaged peers) and or of class size. Results from PISA 2018 suggest that small class size in disadvantaged schools does not fully compensate for the negative impact of the concentration of disadvantage within a school, which suggests that allocating more teachers to schools alone is not sufficient for enhancing the learning environment (OECD, 2019[16]). Previous PISA reports have also noted that some of the education systems identified as top-performers have large classes, and have suggested that investments in teacher quality are more effective than investing in efforts to reduce class size (OECD, 2019[16]; OECD, 2014[25]).

Leveraging time: Adapting schedules and timetables

Research on the effects of the amount of learning time on students’ academic outcomes presents mixed evidence (OECD, 2020[26]). A number of factors – such as teachers’ instructional practices, the curriculum and students’ aptitudes – can mediate or condition the effectiveness of learning time, which means that the relationship between learning time and student achievement is hard to observe empirically (Baker et al., 2004[27]; OECD, 2020[26]; Scheerens and Hendriks, 2013[28]). Studies undertaken between 2009 and 2017 indicate that additional learning time has positive but diminishing effects on student performance student (Bellei, 2009[29]; Cattaneo, Oggenfuss and Wolter, 2017[30]; Gromada and Shewbridge, 2016[31]; Patall, Cooper and Allen, 2010[32]). This is reflected in findings from PISA 2018: on average across OECD countries, performance in reading improved with each additional hour of language-of-instruction lessons per week up to three hours, but this positive association between learning time in regular language‑of‑instruction lessons and reading performance weakened amongst students who spent more than three hours per week in these lessons (OECD, 2020[26]).

Research has also shown that the benefits of additional learning time can vary depending on student profile (for instance, whether they are low performing or come from a low socio-economic background) (OECD, 2020[26]). Radinger and Boeskens (2021[33]) note in an overview of the research that there is support for the hypothesis that added instruction time would be particularly beneficial for socio-economically disadvantaged students and could therefore promote equity in learning outcomes (Gromada and Shewbridge, 2016[31]; Patall, Cooper and Allen, 2010[32]). However, they also underline that in practice the effects of extending instruction time on equity are likely to depend on how the time is used (i.e., what content is covered and how teachers adapt their instruction to individual learners’ needs) (Kraft, 2015[34]), and on how students would otherwise have spent their time. For example, all else being equal, substituting supervised learning support at school for time spent on homework (where family inputs play a greater role in students’ success) is more likely to reduce inequities than increasing instruction time to cover additional curriculum content (Radinger and Boeskens, 2021[33]). A review undertaken by Patall et al. (2010[32]) found that additional school time may be particularly beneficial for at-risk students (Patall, Cooper and Allen, 2010[32]). Indeed, several studies reported that extended school time appeared to be effective for at-risk students or that more time benefitted minority, lower socio-economic status, or low‑achievement students the most. In addition, extending school time may be particularly important for single-parent families and families in which both parents work outside the home (Patall, Cooper and Allen, 2010[32]). Extra time may also be particularly useful for students from an immigrant or refugee background who do not speak the language of instruction (Cerna, 2019[35]). Supplementary extension and enrichment programmes can offer gifted students the opportunity to deepen and extent their learning beyond what is taught within the standard classroom hours (Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation, 2019[36]).

Extending school time should, however, be viewed as one of a number of possible interventions to improve the academic success of disadvantaged students, and not as a universal measure to improve achievement among students. Indeed, other support services, such as after-school programmes, summer school programmes, and other out-of-school services, may provide similar levels of academic support when extended school time is not an option for struggling students. Schools may also organise extra-curricular activities considered to have an impact on the overall well-being of students. These can consist of tutoring or after-school programmes for students falling behind (Travers, 2018[37]), supplementary extension or enrichment programmes for gifted students (Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation, 2019[36]; Rutigliano and Quarshie, 2021[38]), or recreational and social activities designed to improve the overall well-being of students (McBrien, 2022[39]). On this point, findings PISA 2018 showed that students who were enrolled in schools offering more creative extracurricular activities performed better in reading, on average across OECD countries and in 32 countries and economies, after accounting for students’ and schools’ socio-economic profile. At the system level, countries and economies whose schools offer more creative extracurricular activities were also found to tend to show greater equity in student performance (McBrien, 2022[39]).

Use of space

Another important resource is the school’s physical infrastructure: the way in which spaces in schools are designed can influence the ability of the school to be inclusive (Cerna et al., 2021[40]). It can directly affect the school’s climate (discussed below in the section on School climate), interactions and relationships in school, and the ability to engage the community around the school. It also concerns the well-being of particular groups such as with the accessibility for students with physical impairments or ways to organise spaces that are sensitive to minority cultures (ibid.).

As discussed in Chapter 3, infrastructural barriers can impede full accessibility of schools for students with physical impairments. Indeed, for a school to be considered accessible, all students, teachers and parents to be able to safely enter, use all the facilities including recreational areas, participate fully in all learning activities with as much autonomy as possible.

Space can also be adapted at the classroom level to support specific student needs. For instance, certain environmental interventions can be employed by teachers to support the learning of students with SEN (Mezzanotte, 2020[41]). For students with ADHD, for example, teachers organise the classroom space in a way that minimises the risk of distraction and supports improved focus, while also providing increased opportunities for teacher monitoring and interaction (CADDRA, 2018[42]). This could involve seating the student in an area with little distractions, such as near the teacher or seating the student next to positive role models, such as classmates who are likely not distract them and can help them stay on task (CHADD, 2018[43]).

Another way in which space can be used within schools to support students with SEN is through the creation of dedicated sensory rooms or designated quiet spaces. Sensory rooms or quiet spaces can help support autistic students through providing them with a safe space away from over-stimulation. If designed and used effectively, these spaces can also aid in developing students’ coordination, communication and sensory management skills (AsIAm, n.d.[44]). Providing a dedicated room or space is a strategy that has been employed in some schools in Canada to help Indigenous students feel safe and increase feelings of belonging. In some instances, these rooms provide a space where staff can provide dedicated support to Indigenous students (an example is discussed in OECD (2017[10])).

More generally, findings from PISA 2018 showed that, on average across OECD countries, students who had access to a room at school to complete homework scored 14 points higher in reading than students without access to a room for homework (and five points higher after accounting for socio-economic status). Education systems with larger shares of students in schools offering a room(s) for homework tend to show better performance in reading, mathematics and science. However, students in advantaged schools were found to be more likely than students in disadvantaged schools to attend a school that provides a room for homework (the share of students in advantaged schools whose school provides a room for homework being about seven percentage points larger than for the share of students in disadvantaged schools) (OECD, 2020[26]).

A further way in which school spaces can be made more inclusive is through celebrating the cultural heritages and diversity of the student body. A secondary school in New Brunswick, Canada, for instance, has sought to visually reflect the cultural diversity of its students through hanging country flags and displaying welcome boards throughout the school (OECD, 2018[45]). A school in the Coimbra Centro school cluster in Portugal has also decorated the walls of its library with flags and words in numerous languages along with a graph showing the different countries students come from (OECD, 2022[15]). In Australia, the New South Wales Department of Education produces an annual Calendar for Cultural Diversity, which schools can download and print to display on their premises. The calendar provides dates and information for key celebrations, commemorations and observances from different cultures. Each month of the calendar features a different language to reflect the linguistic diversity of the state’s public schools he calendars feature artworks submitted by students from across the state (NSW Department of Education, 2022[46]). In addition to promoting the inclusion of students from an immigrant or refugee background (OECD, 2018[45]), ensuring the visibility of diverse cultures within schools and classrooms has been recognised as important for fostering a sense of belonging among and supporting the engagement of Indigenous students (OECD, 2017[47]). A simple action that schools can take in this respect is using signage at their entrance that is symbolic of Indigenous cultures and includes the use of an Indigenous language or languages. Indigenous cultural symbolism and language can also be integrated throughout the school’s broader ethos, environment and learning activities (OECD, 2017[47]). This approach was taken by a school located in the Northwest Territories of Canada, which used the need to construct a new school building as an opportunity to integrate Indigenous cultural symbolism throughout the school and promote greater learning about Indigenous culture and the region’s history (OECD, 2017[47]).

School climate

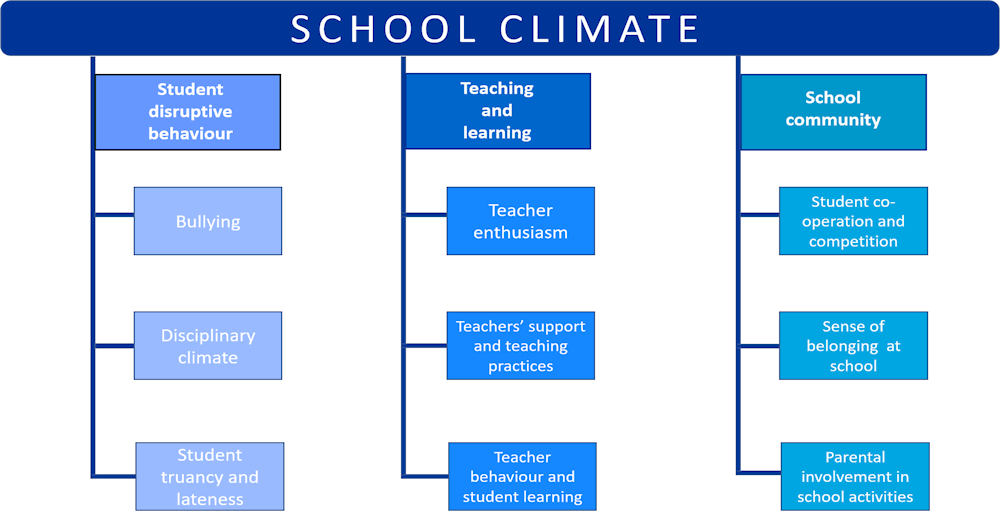

School climate is a broad and multidimensional concept that encompasses “virtually every aspect of the school experience” (OECD, 2019[48]; OECD, 2022[15]; Wang and Degol, 2015[49]). School climate is typically perceived and described as being either positive or negative. In a positive school climate students feel physically and emotionally safe; teachers are supportive, enthusiastic and responsive; parents and guardians engage in school life and activities voluntarily; the school community is built around healthy, respectful and cooperative relationships; and all stakeholders collaborate to develop a constructive school spirt (OECD, 2019[48]; OECD, 2022[15]). While there is not a general consensus on the elements that make up school climate, previous OECD work has identified four spheres that emerge from existing research:

Safety, which includes both maladaptive behaviours (such as bullying, disciplinary problems in the classroom, substance abuse and truancy) and the rules, attitudes and school strategies related to these maladaptive behaviours;

Teaching and learning, which includes aspects of teaching (such as academic support, feedback and enthusiasm, aspects of the curriculum, such as civic learning and socio-emotional skills) and indicators of teacher professional development and school leadership (such as teacher co‑operation, teacher appraisal, administrative support and the school vision);

School community, which includes aspects of the school community (such as student-teacher relationships, student co-operation and teamwork, respect for diversity, parental involvement, community partnerships) and outcomes of these indicators (such as school attachment, sense of belonging and engagement).

Institutional environment, which includes school resources (such as buildings, facilities, educational resources and technology) and indicators of the school organisation (such as class size, school size and ability grouping) (OECD, 2019[48]).

The student and school questionnaires distributed with PISA 2018 included more than 20 questions related to school climate, with further questions included in the parent questionnaire, which was disseminated in 17 PISA-participating countries and economies (OECD, 2019[48]). The responses to these questions provide a series of indicators for the safety (which is renamed in the PISA 2018 Results as “student disruptive behaviour”), teaching and learning, and school community dimensions of school climate, which are summarised in Figure 5.1 below (OECD, 2019[48]).

Figure 5.1. School climate as measured in PISA 2018

Source: OECD (2019[16]), PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life Means for Students’ Lives, PISA, https://doi.org/10.1787/acd78851-en.

A positive school climate can have a significant impact on students’ lives and is key for advancing equity and inclusion in education (OECD, 2019[48]; OECD, 2022[15]). Research indicates that a positive school climate promotes students’ abilities to learn (Thapa et al., 2013[50]), with a number of studies having shown that school climate is directly related to academic achievement, at all school levels (Gottfredson and Gottfredson, 1989[51]; MacNeil, Prater and Busch, 2009[52]; Thapa et al., 2013[50]) and with long-lasting effects (Hoy, Hannum and Tschannen-Moran, 1998[53]). A positive school climate has been found to have a strong influence on the performance of immigrant students (OECD, 2018[54]), and to be able to mitigate the impact of socio-economic status on academic achievement (Berkowitz et al., 2016[55]; Cheema and Kitsantas, 2014[56]; Murray and Malmgren, 2005[57]; OECD, 2019[48]). Beyond academic outcomes, there is a substantial body of research showing that school climate can have a significant impact on students’ mental and physical health (Thapa et al., 2013[50]). School climate can, for instance, improve students’ self-esteem and mitigate the negative effects of self-criticism, as well as positively affecting a range of other emotional and mental health outcomes (ibid.). A positive school climate has also been associated with lower levels of drug use and fewer self-reported psychiatric issues among secondary school students (LaRusso, Romer and Selman, 2007[58]), and has been recognised as predictive of better psychological well-being in early adolescence (Ruus et al., 2007[59]; Thapa et al., 2013[50]). There is evidence that school climate influences students’ motivation to learn (Eccles et al., 1993[60]) and can positively affect student engagement (OECD, 2018[54]; Thapa et al., 2013[50]). A positive school climate can thus, overall, have a profound influence on students’ ability to reach their academic potential and on their social and emotional well-being (OECD, 2019[48]).

Research indicates that some student groups may be more likely to be exposed to non-supportive or hostile school climates. Data from the 2021 Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN)’s National School Climate Survey shows that school is a hostile environment for a number of LGBTQI+ students across the United States, with the majority of survey respondents reporting that they routinely heard anti-LGBTQI+ language and experienced victimisation and discrimination at school (GLSEN, 2022[61]). This example highlights how school climate should be considered also in light of how it can affect and be experienced by different students, and interventions designed accordingly.

Improving a school’s climate

A school’s climate is the result of the multitude of educational policies and practices, student and teacher experiences, and other factors and dynamics that interact with each other in the context of the particular school. Many of these can be grouped in one of the three key elements of school climate identified by PISA 2018 (shown in Figure 5.1). Policies and practices concerning the second and third elements (teaching and learning, and the school community) are discussed in Chapters 2 and 4 of this report and in later sections of this chapter. The next subsection will focus on the first element, school safety, giving particular focus to bullying as a key factor that can shape school climate and that can be addressed through school‑level interventions.

Bullying and school climate

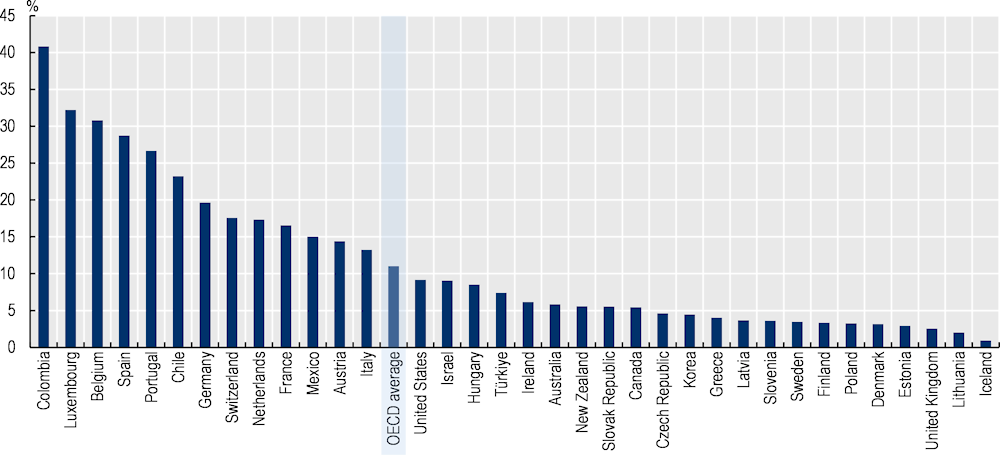

Data from PISA show that bullying is widespread across OECD countries. In the 2018 PISA cycle, on average 23% of students report being bullied at least a few times a month while 8% reported being frequently bullied4 across OECD countries (OECD, 2019[48]).

Both bullying and being bullied have been associated with poorer academic performance and lower well‑being. For instance, students who reported being bullied at least a few times a month scored 21 points lower in reading than those who were less frequently bullied (OECD, 2019[48]). PISA data also suggest that attending a school where bullying is widespread, even if students themselves do not experience bullying, is related to worse performance, highlighting the general role of a safe school climate. From a socio‑emotional perspective, students who are frequently bullied are also more likely to report feeling sad, scared and not satisfied with their lives. High bullying prevalence in schools is also related to a weaker sense of belonging at school, along with a poorer disciplinary climate and less cooperation among classmates.

To counter bullying in schools, teachers and school leaders need to be equipped to both recognise bullying and to actively create an environment where it is less likely to occur. Education systems have sought to address bullying in schools through a range of strategies and practices. These include suspending and expelling bullies, training teachers, teaching empathy and respect to students, maintaining constant adult supervision in school settings, collaborating with parents about student behaviour, and enacting school‑wide policies about bullying (Hall, 2017[62]). A review and analysis of 100 studies evaluating the effectiveness of school-based anti-bullying programmes across a number of countries found that such programmes were effective in reducing both school-bullying perpetration (by an estimated 19-20%) and school-bullying victimisation (by an estimated 15-16%).

However, the authors of the review also found that there was significant heterogeneity across programmes in terms of their effectiveness (ibid.). Further research is needed to develop an understanding of the factors that can contribute to the success of anti-bullying programmes, though, as a starting point, research has suggested that such programmes may be more effective where they are based on evidence and sound theory and where they are implemented with a high level of fidelity (Hall, 2017[62]). Research from the United States on the impact of anti-bullying policies in reducing anti-LGBT5 bullying also found that those with a specific LGBT focus were more likely to result in the improved safety and decreased victimisation of LGBT students than generic anti-bullying policies, which may suggest that targeted interventions may be more effective in addressing bullying directed at specific groups of diverse students (Kull et al., 2016[63]; McBrien, Rutigliano and Sticca, 2022[64]).

One of the most well-known anti-bullying programmes is the Olweus Bullying Prevention Programme. As discussed in Box 5.2, there is substantial evidence confirming this programme’s effectiveness in reducing bullying.

Box 5.2. Olweus Bullying Prevention Programme: a whole-school bullying prevention programme

The Olweus Bullying Prevention Programme was developed to address bullying at both the primary and secondary levels of education. The Programme adopts a whole-school approach to bullying prevention, involving not only students, but also school staff, parents and the community as whole. The Programme is designed so that all students participate in most aspects, with students who have been identified as bullying others or victims of bullying receiving additional individualised interventions.

The Programme addresses the problem of bullying at four levels:

School level: the Programme includes eight school-level components that focus on school communication and training, including the development of a Bullying Prevention Coordinating Committee, the members of which participate in two days of training on Programme implementation.

Classroom level: interventions include defining and enforcing rules against bullying, holding class meetings focused on bullying prevention, promoting positive peer relations and pro-social behaviours, and periodic classroom or grade-level meetings for parents.

Individual level: individual-level components are designed for dealing with individual bullying incidents. The Programme encourages and provides training to school staff to intervene when they witness, suspect or hear reports of bullying, and to effectively communicate with parents. On-the-spot and follow-up interventions provide staff with actions to take when they witness bullying first-hand and when they suspect or hear reports of bullying.

Community level: interventions at this level are designed to develop community support for the Programme so students receive consistent anti-bullying messages in all areas of their lives.

A number of studies have found the Programme to be effective. Quasi-experimental studies that conducted in Norway and the United States, overall found evidence of the Programme having had a short-term positive impact on child outcomes related to student well-being and satisfaction with school life and in terms of preventing crime, violence and antisocial behaviour.

As in 2019, the Programme had been implemented in Barbados, Brazil, Canada, Germany, Iceland, Lithuania, Mexico, Norway, Panama, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Source: Early Intervention Foundation (2019[65]), Olweus Bullying Prevention Programme, https://guidebook.eif.org.uk/programme/olweus-bullying-prevention-programme, (accessed 16 November 2022).

Learning strategies to support diverse students

The practices and strategies employed in the classroom play a crucial role in ensuring all learners are able to reach their educational potential and feel a sense of belonging. Addressing diverse needs in a classroom might involve the use of a variety of teaching formats and practices, adopting multiple ways of representing content to different learners, and adopting different rhythms with different students. In particular, student‑oriented teaching strategies – which place the student at the centre of the activity and give learners a more active role in lessons than in traditional teacher-directed strategies – have been found to have particularly positive effects on student learning and motivation (OECD, 2018[66]). These include differentiated teaching, individualised learning, such as one-to-one tuition, and small group approaches. In addition to adjustments teaching formats and strategies, flexibility in the way in which the curriculum is implemented at the school level can play an important role in addressing the needs of diverse students. The way in which assessments are designed and carried out can also affect student learning outcomes, having the potential to raise achievement and reduce disparities (OECD, 2013[67]).

The following section provides examples of different types of strategies that can be adopted to advance the learning outcomes and foster the inclusion of diverse learners in the classroom. These include adaptations to teaching formats and the curriculum, the use of frameworks to support inclusive teaching, pedagogical approaches, the use of digital technologies, and strategies to ensure equitable and inclusive student assessment.

Adapting teaching formats

There are a variety of ways in which teaching formats can be adapted to provide targeted support to particular learners. Two main approaches to providing teaching and support assistance are one-to-one tuition and small group interventions, which are often employed to support the learning of students with SEN (Brussino, 2020[68]). One-to-one instruction involves intensive individual education provision supported by a specialised teacher or a teaching assistant inside or outside of mainstream classes. In this format, students are encouraged to learn at their own pace with fewer time constraints and less pressure than may exist in group environments (Grasha, 2002[69]). In addition, one-to-one tuition does not stimulate competition with other students; this, for many, represents a positive aspect of such an approach.

However, limiting learning inputs and stimuli to only one teacher without including opportunities to learn alongside peers could discourage students with SEN. Interacting only with a teacher could make the learning less varied and could enhance feelings of marginalisation with respect to the rest of the classroom. From an economic perspective, one-to-one approaches can also be relatively expensive (Education Endowment Foundation, 2018[70]).

In small-group interventions, learning and teaching occur in small groups where a specialised teacher or teaching assistant follows a small number of students with SEN. In Japan, for instance, students who have been identified as having comparatively mild SEN are supported through small-group instruction in mainstream settings, and students identified as having greater needs can be supported either individually or in small teams in resource rooms in mainstream settings (Brussino, 2020[68]). Unlike one-to-one tuition, the small-group approach encourages peer learning and interaction. Specialised teachers provide support to small groups of students with SEN ensuring that students learn at their own rhythm and receive more support and feedback than in mainstream settings. Compared to one-to-one approaches, small groups can stimulate more active and deeper learning on top of strengthening socialisation and peer learning (Jones, 2007[71]). Small group instruction can also be more efficient in terms of resource and time management than one-to-one strategies (Bertsch, 2002[72]), even if additional investments and resources may be needed to provide specialised staff and teaching rooms (Jones, 2007[71]).

Small-group learning might create pressure and anxiety in students who are less active participants in discussions and group works. Further challenges could arise if teachers are used to teacher-centred teaching strategies as small-group learning entails more student-centred approaches (Bertsch, 2002[72]).

There are therefore several advantages and disadvantages to be considered when designing and implementing teaching formats for students with SEN, as summarised below (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1. Advantages and disadvantages of one-to-one and small group tuition

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

|---|---|---|

|

One-to-one tuition |

|

|

|

Small-group approach |

|

|

Sources: Adapted from Brussino (2020[68]), Mapping policy approaches and practices for the inclusion of students with special education needs, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 227, https://doi.org/10.1787/600fbad5-en.

Adapting the curriculum

As discussed in detail in Chapter 2, curriculum has an important role in the promotion of equity and inclusion in education systems. The implementation of curriculum at the school level also has a significant impact on student lives. In practice, the flexibility in delivering the curriculum supports teachers in addressing the needs of diverse students.

Individual Education Plans

A key tool in the adaptation of the curriculum is the development of individualised plans for students with SEN, which allow for the provision of tailored programmes based on the child’s difficulties and needs for flexibility (Mezzanotte, 2020[41]). These programmes are most often referred to as “Individual Education Plans” (IEPs), but may also be known in different education systems as ‘Negotiated Education Plans’, ‘Educational Adjustment Programmes’, ‘Individual Learning Plans’, ‘Learning Plans’, ‘Personalised Intervention Programmes’, and ‘Supervisory Plans’ (Mitchell, Morton and Hornby, 2010[73]). Generally, these plans are documents tailored on the individual children and their needs, and include elements such as a student’s present level of performance, the individualised instruction and related services to be provided, the support mechanisms being offered (such as accommodations or assistive technology), and the annual goals set for the student (Undestood, 2019[74]).

Individual Education Plans are offered in most OECD countries, with variation in the way in which they are developed (Mezzanotte, 2020[41]). In some countries, the development of each plan is carried out within the individual school. Some countries, such as the France, Ireland, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States, do not rely only on teachers or principals for the drafting of the IEPs, but also involve – or take into consideration – other actors, such as neuro-psychiatrists or clinical psychologists, parents and sometimes the children themselves, in the process (Sandri, 2014[75]; Cavendish and Connor, 2017[76]). Other countries, such as Spain, make curricula adaptations for students the exclusive competence of the tutor or teacher of the specific subject (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional (Ministry of Education and Vocational Training), 2015[77]). Education systems also differ in the legal status of IEPs and in whether their content is set by law or is a more flexible document that can be amended and updated according to the needs and progress of the student (Mezzanotte, 2020[41]).

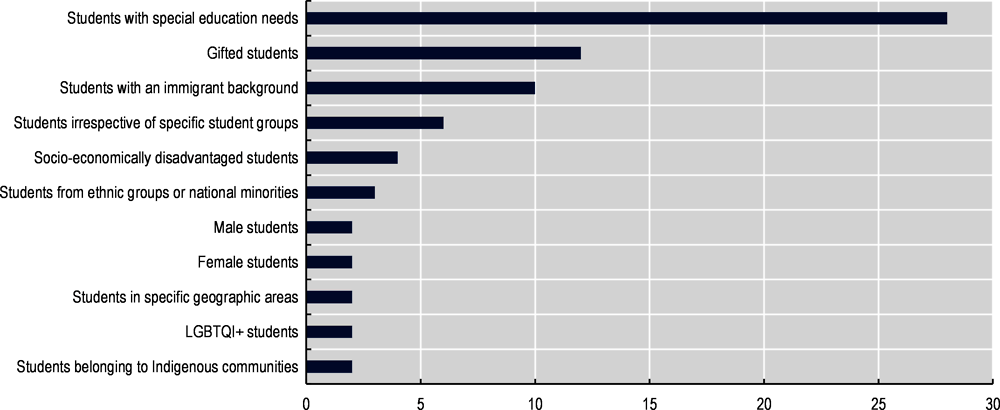

The Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022 (Figure 5.2) shows that the majority of education systems provided IEPs for students with SEN, as described above. However, the use of such plans extends to other student groups, too. For instance, IEPs are also provided to students with an immigrant background. In Sweden, for example, all new arrivals are assessed on their academic knowledge and language skills within two months of starting school (with academic knowledge assessments being held in the students’ mother tongues in order to enable students to demonstrate their previous learning without being hindered by language barriers) (Bunar, 2017[78]; Cerna, 2019[35]). School leaders use the results to determine the most appropriate educational trajectory for each student, having regard to their age, language skills and their academic knowledge. It is mandatory for all newly arrived students from grade 7 onwards to have an IEP (Cerna, 2019[35]; Skolverket (National Agency for Education), 2018[79]). Similarly, in Finland, an individual curriculum is designed for each student with a refugee or immigrant background based on their learning needs, previous school history, age and other factors related to their background that may be relevant to their schooling (such as whether they are an unaccompanied minor or have come from a war situation). The individual curriculum is determined by the teacher in collaboration with the student and their family (Cerna, 2019[35]; Dervin, Simpson and Maitkainen, 2017[80]).

Ten education systems reported providing IEPs to immigrant students in the Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022. In addition, 12 reported providing IEPs to gifted students, and six reported providing IEPs to all students, irrespective of whether a student belongs to a particular diverse group or groups.

Figure 5.2. Provision of an Individual Education Plan (or a similar document)

Note: This figure is based on answers to the question “Does the education policy framework in your jurisdiction require teachers at ISCED 2 level to provide diverse students with any of the following? [Provision of an Individual Education Plan (or a similar document)]”. Thirty-one education systems responded to this question. Response options were not mutually exclusive.

Options selected have been ranked in descending order of the number of education systems.

Source: OECD (2022[81]), Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022.

Conditions regarding the entitlement of IEPs vary across education systems. Some education systems, for example, require students to have received a formal diagnosis of SEN to be assigned an IEP and receive instructional support at school (Mezzanotte, 2020[41]). This can present challenges for students who have not been able to obtain an official diagnosis but are nevertheless in need of additional support (ibid). A way of addressing this issue in education systems requiring an official diagnosis could be to offer the option of developing an alternative, less formal individualised learning plan for students who do not meet the official criteria to be eligible for an IEP. In Finland, for example, Learning Plans can be developed for any student, including those who have not received an official SEN diagnosis and who are therefore not eligible for an IEP. The Learning Plan is designed to support any student to learn (be they a student with SEN, a student from an immigrant background, or a gifted student) and to help teachers in adopting differentiation teaching strategies (Mezzanotte, 2020[41]; Mitchell, Morton and Hornby, 2010[73]).

In addition to facilitating the development of tailored learning programmes while a student is at school, IEPs (or equivalent student planning documents) can be used to help students prepare for their future beyond secondary education (Mezzanotte, 2020[7]). The degree and nature of support offered by schools has been recognised as playing a key role in students’ ability to cope with and navigate the transition process from secondary education to tertiary education and/or the workforce (Ebersold, 2012[82]). This can be particularly important for students with SEN, who may face many barriers that hinder their entry into higher education or the labour market (Mezzanotte, 2020[7]). Several OECD education systems (such as Canada, Ireland, New Zealand and Scotland (United Kingdom)) specifically include transition planning in the guidelines provided for IEPs (Mitchell, Morton and Hornby, 2010[73]; Mezzanotte, 2020[7]). The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act 1997 mandates transition planning as part of the IEP for students from the age of SEN (National Transition Network, n.d.[83]), and the statutory guidance for organisations working with young people with SEN in the United Kingdom and Wales also specifies that transition planning must be incorporated into the education, health and care plans for students from year 9 (ISCED 2) onwards (Department for Education; Department of Health, 2015[84]).

Accommodations and modifications

Individual Education Plans enable schools to provide adaptations of the curriculum to address students’ specific needs. There are a variety of ways in which curricula can be adapted so as to be made more accessible to students, including in terms of content, teaching materials and responses expected from learners. Modifications (e.g., enlarging the font of a text), substitutions (e.g., Braille for written materials) or omissions of complex work are all possibilities for students with SEN (Mitchell, Morton and Hornby, 2010[73]).

Individual Education Plans generally provide for or facilitate two main types of adjustments: accommodations and modifications (see Chapter 2). Accommodations concern how students learn, while modifications relate to what students learn (Understood, 2019[85]). Accommodations are intended to help students learn the same information as other students, and can be instructional (adjustments in teaching strategies to enable the student to learn and to progress through the curriculum), environmental (changes or additions to the physical environment of the classroom and/or the school) or relate to assessment (adjustments in assessment activities and methods required to enable the student to demonstrate learning) (Olszewski-Kubilius and Lee, 2004[86]). In their implementation at the school level, accommodations are most effective when tailored to the specific needs of the children. For example, common accommodations that are often offered to students with ADHD include providing additional time for tests, the use of positive reinforcement and feedback, changes to the environment to minimise the risk of distraction and the use of technology to assist with tasks (CDC, 2019[87]; Mezzanotte, 2020[41]).

In cases where accommodations do not sufficiently provide for the needs of children with IEPs, modifications must be made. Whereas accommodations allow students to learn the same content as their peers, modifications are actual changes to assignments or the curriculum that schools and teachers can design to make it easier for students to stay on track (Sands, 2016[88]) and can involve the student learning different material, being graded or assessed under different standards than other students, or being excused from particular projects (Morin, 2019[89]). In the case of gifted students, for instance, schools can provide specific classes or courses with modified expectations. For some students (such as language and mathematics), the gifted student may work to learning expectations from a different grade level. In other subjects, the complexity of the learning expectations may be increased. With this type of programming, the affected subjects or courses would be identified in the IEP as subjects or courses with modified expectations (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2004[90]).

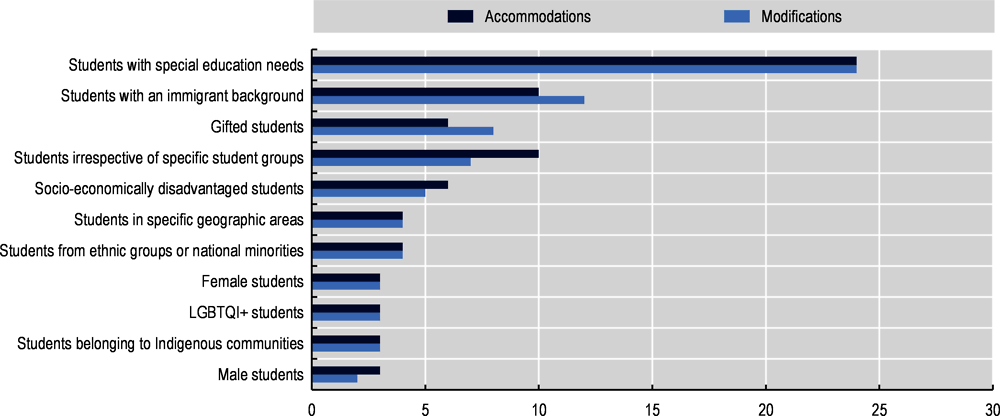

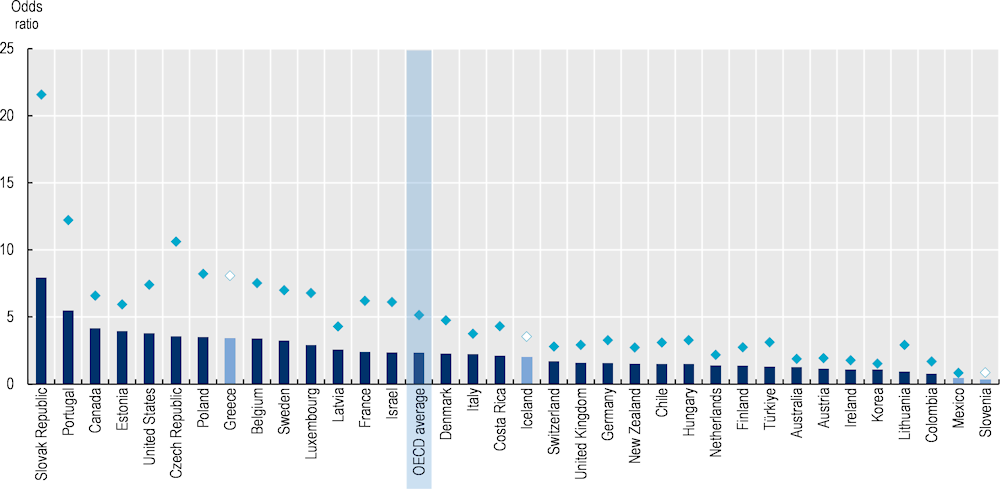

As shown in Figure 5.3, 24 of the education systems who participated in the Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022 reported providing accommodations and modifications for students with SEN. In many of these cases (19), students with SEN were the only group reported as being entitled to accommodations or modifications. Ten education systems reported offering accommodations exclusively to students with SEN (Canada, Denmark, the Flemish Community of Belgium, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, the Slovak Republic, Scotland (United Kingdom), United States), and ten reported offering modifications exclusively to this student group (Canada, England (United Kingdom), the Flemish Community of Belgium, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Scotland (United Kingdom), the United States). As discussed above, the entitlement to accommodations and modifications in certain systems may be linked to an official diagnosis of disability or specific disorder.

However, a number of education systems reported providing adaptations to other groups, or to all students irrespective of their specific groups. As shown in Figure 5.3, various systems reported offering accommodations (10) and modifications (12) to students with an immigrant background, and 10 and 7 education systems respectively reported offering them to all students, irrespective of their background. A number of systems also reported offering accommodations and modifications to gifted and socio-economically disadvantaged students.

Figure 5.3. Accommodations and modifications

Note: This figure is based on answers to the question “Does the education policy framework in your jurisdiction require teachers at ISCED 2 level to provide diverse students with any of the following?”. Thirty-two education systems responded to this question. Response options were not mutually exclusive.

Options selected have been ranked in descending order of the number of education systems that require the provision of modifications.

Source: OECD (2022[81]), Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022.

There are, however, concerns that practices associated with providing students with certain accommodations can give rise to the risk of “watering down” the curriculum and expectations of students (Ellis, 1997[91]; Sitlington and Frank, 1993[92]). The types of accommodations concerned are those that seek to enable students to acquire the necessary credits to graduate and enable them to understand and retain the knowledge necessary to attain course credits. Limitations associated with such accommodations include their emphasis on memorising loosely related facts, reduced opportunities for learning content and to develop thinking skills, inhibited "learnability" of subject matter, and reduced investment in learning (Mezzanotte, 2020[41]; Ellis, 1997[91]).

In addition, a study on IEPs in the United States published in 2014 has shown that many of the most commonly used support tools for students with ADHD have very limited research support, and that the most empirically-validated approaches were rarely included on the IEPs of students with ADHD (Spiel, Evans and Langberg, 2014[93]). It was found that only around one-fourth of the interventions implemented for students with ADHD were supported by evidence of efficacy in literature. For example, the most common support mechanisms – extended time on tests and assignments, progress monitoring, and case management – were found to have no reported evidence of effectiveness in improving performance among ADHD students. Other research has also found that additional test time does not appear to provide more benefits to students with ADHD than students without (Lewandowski et al., 2007[94]). In fact, extended test time can affect their ability to stay focused for the whole duration of the test, due to the difficulties such students experience in sustaining attention for longer time periods (Pariseau et al., 2010[95]).

Overall, the researchers identified a need for further research to evaluate the effectiveness of the more frequently-used services for students with ADHD, as most of these had never been systematically evaluated (Spiel, Evans and Langberg, 2014[93]). Another notable issue concerning adjustments to curricula and support mechanisms is that the range of services offered can vary greatly between specialised schools and mainstream classrooms (Murray et al., 2014[96]).

Frameworks for inclusive learning

Advancing inclusion and equity requires learning and teaching to be adapted to students, rather than expecting students to adapt to traditional learning and teaching practices. The next section presents two frameworks that can be used to guide and support teachers and school staff in designing and delivering pedagogies, curricula and assessments that foster the inclusion of all learners in increasingly diverse classrooms.

Universal Design for Learning

The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a tool that can be used to support teachers and education stakeholders in designing and implementing inclusive teaching through pedagogies, curricula and assessments. Universal Design for Learning aims to dismantle barriers to participation and learning for all learning by centring learner variability in curriculum development (Waitoller and King Thorius, 2016[97]; Rose and Meyer, 2002[98]).

The UDL provides three guiding principles for the design and implementation of flexible curriculum goal, materials, methods, and assessments, as follows (CAST, 2018[99]; Brussino, 2021[100]; Rose and Meyer, 2002[98]):

1. Multiple means of representation. This principle addresses the “what” of learning, accounting for the different ways in which learners perceive and understand information, and guides teachers to present information in various, flexible formats.

2. Multiple means of action and expression. This principle addresses the “how” of learning, accounting for the different ways by which students navigate the learning activity and express their knowledge.

3. Multiple means of engagement. This principle targets the “why” of learning, addressing the various ways in which students’ interest can be attracted and sustained, while also guiding teachers to build into a particular learning activity various sources of motivation and engagement.

Rather than representing three separate guidelines, these principles constitute an overarching structure to be embedded within curriculum, materials, instruction and assessment. The nature of these three guidelines allows educators to develop learning environments in which accommodations and modifications are not seen as additional work for the teaching staff, but as part of an inclusive structure to be implemented systematically (Jimenez and Hudson, 2019[101]).

The UDL is particularly helpful in increasingly diverse classrooms, as it provides for the flexibility necessary to support diverse learning needs and styles (Brussino, 2021[100]). Through its focus on providing students with different means to interact with learning material and adapting information to students (rather than asking students to adapt to the information), the UDL can help schools better accommodate students’ needs and learning in diverse classrooms (CAST, 2018[99]).

Universal Design for Learning Guidelines have been developed for teachers and other education stakeholders to implement the UDL framework. These guidelines provide practical suggestions to develop inclusive teaching and learning strategies that can promote the well-being of all students (see Table 5.2).

Table 5.2. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines

|

Provide multiple means of engagement |

Provide multiple means of representation |

Provide multiple means of action and expression |

|---|---|---|

|

Provide options for recruiting interest: Optimise individual choice and autonomy Optimise relevance, value and authenticity Minimise threats and distractions |

Provide options for perception: Offer ways of customising the display of information Offer alternatives for auditory information Offer alternatives for visual information |

Provide options for physical action: Vary the methods for response and navigation Optimise access to tools and assistive technologies |

|

Provide options for sustaining effort and persistence: Heighten salience of goals and objectives Vary demands and resources to optimise challenge Foster collaboration and community Increase mastery-oriented feedback |

Provide options for language and symbols: Clarify vocabulary and symbols Clarify syntax and structure Support decoding of text, mathematical notation and symbols Promote understanding across languages Illustrate through multiple media |

Provide options for expression and communication: Use multiple media for communication Use multiple tools for construction and composition Build fluencies with graduated levels of support for practice and performance |

|

Provide options for self-regulation: Promote expectations and beliefs that optimise motivation Facilitate personal coping skills and strategies Develop self-assessment and reflection |

Provide options for comprehension: Activate or supply background knowledge Highlight patterns, critical features, big ideas and relationships Guide information processing and visualisation Maximise transfer and generalisation |

Provide options for executive functions: Guide appropriate goal-setting Supporting planning and strategy development Facilitate managing information and resources Enhance capacity for monitoring progress |

Source: Brussino (2021[100]), adapted from CAST (2018[99]), Universal Design for Learning Guidelines, http://udlguidelines.cast.org (accessed 15 October 2020).

While UDL is often perceived as a tool to support students with SEN, it is designed to support the development of a universal approach to teaching diverse groups that encompasses learners. The UDL framework has been recognised as designing both the instructional context and content for variability and differentiation from the outset, eliminating or reducing the number and severity of learning barriers in way that results in increased access for all and less work for individual educators (Jimenez and Hudson, 2019[101]). A meta-analysis on the empirical research on the effectiveness of UDL as a teaching method to improve the learning of all students found that UDL can improve the learning process and have positive impacts for both students with SEN and those without (Capp, 2017[102]). Identified benefits of implementation of the UDL for students without SEN increased academic engagement, improved relationships with peers, a greater appreciation of diversity, the acquisition of new advocacy and support skills, increased empathy, and having higher expectations for their classmates (Capp, 2017[102]).

Intercultural education

Intercultural education has received increasing attention as a strategy for the inclusion of diverse students in mainstream education (Rutigliano, 2020[103]), particularly for students from a refugee or immigrant background (Portera, 2008[104]). A growing body of experts and academics have highlighted the necessity of implementing schools with an intercultural programme to enhance ethnic minority students’ performance and well-being and to benefit society as a whole (OECD, 2010[105]; Kirova and Prochner, 2015[106]; Calogiannakis et al., 2018[107]; Vandekerckhove et al., 2019[108]; Rozzi, 2017[109]). Researchers have found that intercultural education can lead to intercultural competence, which can be defined as “the ability to interact effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations, based on one’s intercultural knowledge, skills and attitudes” and is associated with empathy, flexibility and reflection (Rapanta and Trovão, 2021[110]). The results of a 2015 study on the impacts of programme implemented in Romania have also been interpreted as suggesting that intercultural education programmes may help promote more positive attitudes among teachers and students toward Roma (Nestian Sandu, 2015[111]).

The concept of intercultural education corresponds to a pedagogy based on “mutual understanding and recognition of similarities through dialogue” (Kirova and Prochner, 2015, p. 392[106]; Rutigliano, 2020[103]). The ultimate goal is to create a shared space where all students’ cultural differences are valued, and not put aside or simply acknowledged. In this sense, the notion of interculturalism goes beyond that of multiculturalism which is limited to cohabitation and the acknowledgment of the existence of different cultures (Meer, 2014[112]). UNESCO (2006[113]) has identified three basic principles to guide international action in the field of intercultural education:

Principle I: Intercultural Education respects the cultural identity of the learner through the provision of culturally appropriate and responsive quality education for all.

Principle II: Intercultural Education provides every learner with the cultural knowledge, attitudes and skills necessary to achieve active and full participation in society.

Principle III: Intercultural Education provides all learners with cultural knowledge, attitudes and skills that enable them to contribute to respect, understanding and solidarity among individuals, ethnic, social, cultural and religious groups and nations.

According to UNESCO (2006[113]), intercultural education should not represent a simple “add on” to the regular curriculum. It rather needs to be embedded into the learning environment as a whole, as well as other educational processes and features, such as teacher education and training, languages of instruction, teaching methods, and learning materials (ibid). Fostering an inclusive and intercultural approach in schools therefore requires actions at the different levels of an education system, i.e. clear legal and political frameworks, sufficient resources, capacity building and consistent changes at the school level in order to implement a new vision based on inclusion and diversity (Guthrie et al., 2019[9]). It can be seen as connected to the concept of Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy, which emphasises the need to sustain students’ cultural and linguistic backgrounds and diversity in the classroom (discussed in more detail Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies ). Intercultural education is also tightly linked to the involvement of the community as a whole (discussed further below), requiring both a commitment to creating an inclusive school atmosphere and a desire to strengthen the participation of all stakeholders in the design and implementation of such an environment.

In the European context, “intercultural education” was first referred to in an official capacity in 1983, when European ministers of education highlighted the intercultural dimension of education in a resolution regarding the schooling of immigrant children, and has featured in education projects promoted by the Council of Europe since the mid-1980s (Portera, 2008[104]; Rapanta and Trovão, 2021[110]). It is now considered by the European Union as the official approach to be used in schools for the integration of immigrant and ethnic minority group students (Tarozzi, 2012[114]). Several European countries, such as Italy and Greece, have specific policies and/or legal frameworks on intercultural education (Tarozzi, 2012[114]; Rutigliano, 2020[103]). Ireland also had a specific strategy for intercultural education from 2010 to 2015, which aimed to ensure that (i) “experience an education that respects the diversity of values, beliefs, languages and traditions in Irish society and is conducted in a spirt of partnership” (reflecting the Education Act 1998) and (ii) “all education providers are assisted with ensuring that inclusion and integration within an intercultural learning environment become the norm” (Department of Education and Skills and the Office of the Minister for Integration, 2010[115]).

Pedagogical changes to reach all students

General pedagogical knowledge refers to “the specialised knowledge of teachers for creating effective teaching and learning environments for all students independent of subject matter” (Guerriero, 2017, p. 80[116]). It provides teachers with a common reflection ground and language to discuss their students’ learning progress as well as well-being and ways to improve the teaching and learning support across subjects (Ulferts, 2021[117]). Teachers’ general pedagogical knowledge is a crucial resource for effective teaching and learning, with research showing that general pedagogical knowledge is associated with higher quality teaching and better student outcomes (Ulferts, 2021[117]; Ulferts, 2019[118]).

The pedagogical knowledge of teachers also has specific implications for equity and inclusion in education. There is, for instance, a growing body of literature that shows that culturally responsive teaching practices - drawing on students’ cultures and lived experiences to create authentic learning experiences in an environment that fosters critical engagement and mutual respect (Egbo, 2018[119]) - have a positive impact on not only students’ learning (Cabrera et al., 2014[120]; Cammarota, 2007[121]; Dee and Penner, 2016[122]; Ulferts, 2021[117]) but also their engagement and psychological well-being (Cholewa et al., 2014[123]; Savage et al., 2011[124]). Research further indicates that culturally responsive teaching practices improve the school climate (Khalifa, Gooden and Davis, 2016[125]; Ulferts, 2019[118]) and can help to reduce the disproportionate representation of culturally and linguistically diverse students in special education programmes (Klingner et al., 2005[126]; Ulferts, 2019[118]).

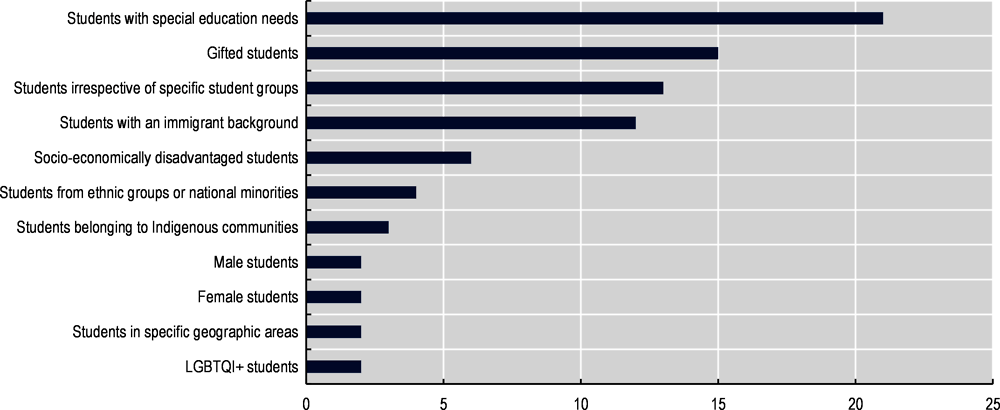

A number of education systems reported requiring teachers at ISCED 2 level to adapt their pedagogical approaches to respond to different learners in the Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022. This was most frequently reported as being required for students with SEN, by 21 education systems. In addition, 13 systems reported requiring teachers to adapt their pedagogical approaches to respond to all students, irrespective of student groups, and 15 to gifted students specifically. Twelve education systems reported requiring teachers to provide changes in their pedagogical approaches to support students with an immigrant background.

Figure 5.4. Changes in pedagogical approaches

Note: This figure is based on answers to the question “Does the education policy framework in your jurisdiction require teachers at ISCED 2 level to provide diverse students with any of the following? [Changes in pedagogical approaches (e.g., differentiated pedagogy for gifted students)]”. Thirty-one education systems responded to this question. Response options were not mutually exclusive.

Options selected have been ranked in descending order of the number of education systems.

Source: OECD (2022[81]), Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022.

There is a wide number of pedagogical approaches that can be adopted by teachers to support the learning of all their students, based on their need and attitudes. The following sections discuss some of the most well-known teaching strategies for advancing equity and inclusion in education.

Differentiated instruction

Differentiated instruction, or differentiation, is an approach to teaching that has received increased attention in a context of growing diversity. Differentiated instruction has been defined as a philosophy for teaching that is grounded in the idea that students learn best when their teachers effectively address variance in their readiness levels, interests, and learning profile preferences (Tomlinson, 2005, p. 263[127]). It is based on a flexible approach to education that involves “building instruction from students’ passions and capacities, helping students personalise their learning and assessments in ways that foster engagement and talents, and encouraging students to be ingenious” (OECD, 2018[66]; Rutigliano and Quarshie, 2021[38]). Differentiated instruction is at the core of equitable and inclusive education systems, as it means responding to and serving all student needs (OECD, 2022[128]), thereby supporting all learners in achieving their educational potential (OECD, 2012[129]). In the environment developed through differentiated instruction model, teachers, support staff and professionals collaborate to create an optimal learning experience for students: each student is valued for his or her unique strengths, while being offered opportunities to demonstrate skills through a variety of assessment techniques (Subban, 2006[130]). The differentiated classroom balances learning needs common to all students, with more specific needs tagged to individual learners, and can avoid the need for labelling students (ibid.).

Tomlinson (2001[131]) provides a comprehensive definition that sets out what differentiated instruction is and what it is not, the key elements of which are set out in Table 5.3 below. Based on this definition, differentiated instruction can be summarised as a proactive, flexible and student-centred approach that provides multiple approaches to learning processes and content and that incorporates whole-class, group and individual teaching formats.

Table 5.3. What is differentiated instruction?

|

What differentiated instruction is not |

What differentiated instruction is |

|---|---|

|

Differentiated instruction is not the “individualised instruction” of the 1970s. |

Differentiated instruction is proactive. |

|

Differentiated instruction is not chaotic. |

Differentiated instruction is more qualitative than quantitative. |

|

Differentiated instruction is not just another way to provide homogeneous grouping |

Differentiated instruction is rooted in assessment. |

|

Differentiated instruction is not just “tailoring the same suit of clothes.” |

Differentiated instruction provides multiple approaches to content, process, and product. |

|

Differentiated instruction is student centered. |

|

|

Differentiated instruction is a blend of whole-class, group, and individual instruction. |

|

|

Differentiated instruction is “organic.” |

Source: Adapted from Tomlinson, C.A. (2001[131]), How To Differentiate Instruction In Mixed-Ability Classrooms, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, https://rutamaestra.santillana.com.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Classrooms-2nd-Edition-By-Carol-Ann-Tomlinson.pdf (accessed 16 January 2023)

Differentiation is an approach to teaching that supports all learners in achieving their educational potential (UNESCO, n.d.[132]; OECD, 2022[128]), with studies indicating that it can have positive effects on student achievement (Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019[133]). It has been recognised as essential both to enhance the academic development of gifted students and to prevent the development of interpersonal challenges for gifted children (Beljan et al., 2006[134]). Differentiated instruction can also play an important role in the learning of immigrant students in the sense that it takes into account their proficiency in the host country language and ensures learning content is delivered in a way that is comprehensible (OECD, 2022[128]). The incorporation of tailored behavioural interventions and teaching practices also plays an important role in promoting the learning of students with SEN (Mezzanotte, 2020[7]). Box 5.3 provides an example of how teaching can be differentiated to support the specific needs of students with ADHD. Differentiated instruction can similarly be leveraged to support other students with similar SEN.

Box 5.3. Targeted academic instruction: an example for ADHD

Adapting academic instruction can help teachers support students with ADHD in achieving and fulfilling their potential (U.S. Department of Education, 2008[135]). Indeed, teachers can foster their students’ academic success by differentiating teaching methodologies to address different learning needs (HADD Ireland, 2013[136]).

For instance, teachers can adopt specific strategies with respect to the timeline and structure of their lessons to address the learning needs of students with ADHD. As discussed by the US Department of Education (2008[135]), students with ADHD are more likely to learn best when they are situated in a structured lesson, where the teacher is able to clearly explain what they want students to learn and what they expect from them, both from an academic and a behavioural perspective. In this respect, a number of specific teaching practices at the start of the lesson can be helpful, such as preparing the students for the day’s lesson by summarising the order of various activities planned and reviewing the content that was studied during the previous lesson. In addition, teachers can specify how they expect the children to behave and act (such as speaking with a low tone to their classmates to work on an assignment or raising hands before speaking) and set out all the material students will need for the class.

While conducting the lesson, it is important for teachers to keep track of the children’s understanding of the material by asking questions, divide work into smaller tasks that can foster the concentration, and provide follow-up directions both orally and in written form. In addition, as children with ADHD tend to struggle with transitions between lessons, preparing them for transitions from one lesson to the other can help them stay on task. Lastly, in terms of the conclusion of the lesson, it is helpful for teachers to notify students in advance, verify whether the assignments have been completed and instruct students on how to start preparing for the following lesson.

Table 5.4 summarises potential ways in which teachers can adapt their lessons and teaching to more effectively support students with ADHD.

Table 5.4. Academic instruction interventions

|

Academic Instruction |

|

|---|---|

|

Introducing lessons |

Provide an advance organiser |

|

Review previous lessons |

|

|

Set learning expectations |

|

|

Set behavioural expectations |

|

|

State needed materials |

|

|

Explain additional resources |

|

|

Simplify instructions, choices, and scheduling |

|

|

Conducting lessons |

Be predictable: maintain structure of the lessons |

|

Support the student’s participation in the classroom |

|

|

Use audio-visual materials |

|

|

Check student performance |

|

|

Ask probing questions |

|

|

Perform ongoing student evaluation |

|

|

Help students correct their own mistakes |

|

|

Help students focus |

|

|

Follow-up directions (oral/written) |

|

|

Lower noise level |

|

|

Divide work into smaller units |