This chapter analyses the fundamental role that monitoring and evaluation can play in ensuring the continuous improvement and the effectiveness of policies targeted at addressing diversity in education and improving equity and inclusion in education systems. Specifically, this chapter focuses on monitoring equity and inclusion in education, evaluating policies and practices to address diversity, and promoting equity and inclusion at the system, local and school levels. The chapter concludes by proposing policy pointers for approaches to monitoring and evaluation that promote equity and inclusion in education.

Equity and Inclusion in Education

6. Monitoring and evaluating equity and inclusion

Abstract

Introduction

This chapter discusses the fundamental role that monitoring and evaluation can play in ensuring that an education system is not only introducing policies to improve equity and inclusion, but is also implementing them and achieving its objectives.

Without relevant information on the current state of equity and inclusion and progress towards these, policy makers might judge the system according to the imperfect data they have available. This might misdirect them or, in the case of absence of data, may mean that they are unaware of challenges that need action. Monitoring systems are therefore important to assess progress in improving equity and inclusion in education. They are crucial in providing feedback to inform improvements across the education system, as well as in identifying necessary support measures for schools.

Evaluation is important in determining whether policies are having the intended effects and in informing necessary adjustments. The evaluation process can help policy makers decide, for instance, whether policies are having inadvertent effects and should be discontinued, or whether they warrant further support. In the case of smaller programmes, this can entail their upscaling or institutionalisation. While evaluation can pose challenges, it is particularly important to seek co-operation and consensus across all stakeholder levels in evaluating and subsequently implementing changes that lead to equity and inclusion.

Programmes that support equity and inclusion in education are also designed and implemented at the local and school levels. Hence, the monitoring of progress towards more equitable and inclusive education systems is important at these levels, too. Individual actors need to assess their circumstances and thus receive feedback on their performance in the areas of equity and inclusion. This might also help them identify how to improve their interventions to support equity and inclusion in individual schools. External, as well as internal, school evaluation can be highly informative in improving equity and inclusion in education.

This chapter is organised in five sections. After the introduction, the second section elaborates on monitoring progress in improving equity and inclusion. The third section examines evaluations of policies, programmes and processes to improve equity and inclusion. The fourth section explores supports for schools in improving equity and inclusion practices through evaluation processes. The final section provides pointers for future policy development.

Monitoring progress in improving equity and inclusion in education

Education systems differ in how they monitor progress in improving equity and inclusion in education. The following sections summarise what is monitored, what instruments are used to measure progress and the use of monitoring results.

Operationalisation of equity and inclusion in monitoring systems

Monitoring and evaluation frameworks can be used for accountability and improvement purposes (OECD, 2013[1]). A major accountability objective is to inform the public of the quality of the education system, including the quality of education for diverse groups. Another objective is to provide feedback on reforms in the education system that can be used to improve educational processes and outcomes of all students. In general, six major aims can be distinguished (OECD, 2013[1]):

Monitoring of student academic and broader well-being outcomes, including the disaggregation by dimensions of diversity, socio-economic background and geographic location;

Monitoring of student outcomes over time;

Monitoring of the impacts of a policy;

Monitoring demographic, administrative and contextual data which can explain the outcomes of the education system;

Generating feedback and information for stakeholders in the education system; and

Using the generated information for development and implementation of policies.

These aims can be subsequently tailored for the purposes of monitoring progress in improving equity and inclusion in education. The extent to which these aims are present in a given education system varies. Equity and inclusion are intrinsically linked to the context of each education system – so their monitoring may differ considerably from country to country. Indeed, in academic literature, international definitions or national practices, there is no consensus on either the definitions of equitable and inclusive education systems, or the difference between the two. For the purposes of this report, readers are invited to refer to the explanations provided in Chapter 1.

Equitable education systems are those that ensure the achievement of educational potential regardless of personal and social circumstances, including factors such as gender, ethnic origin, Indigenous background, immigrant status, sexual orientation, gender identity, special education needs (SEN) and giftedness (Cerna et al., 2021[2]; OECD, 2017[3]). A closely related term is that of “equal educational opportunities”. In a system that offers equal educational opportunities, educational outcomes are the result of actions within the individual student’s control and their ability to reach their full potential is not hindered by circumstances beyond their control. Under this notion, educational outcomes should be a result of actions in individuals’ control and not of circumstances beyond their control so that they can reach their full potential. One of the roles of monitoring progress in improving equity in education is to look at the disparities in educational outcomes as well as (in)equalities in opportunities. In order to simplify and classify the concept of equity in education, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2018[4]) published the Handbook on Measuring Equity in Education that outlines a classification of equity in education into five concepts: meritocracy, minimum standards, impartiality, equality condition and redistribution (Box 6.1).

Box 6.1. Concepts of equity in education

Meritocracy

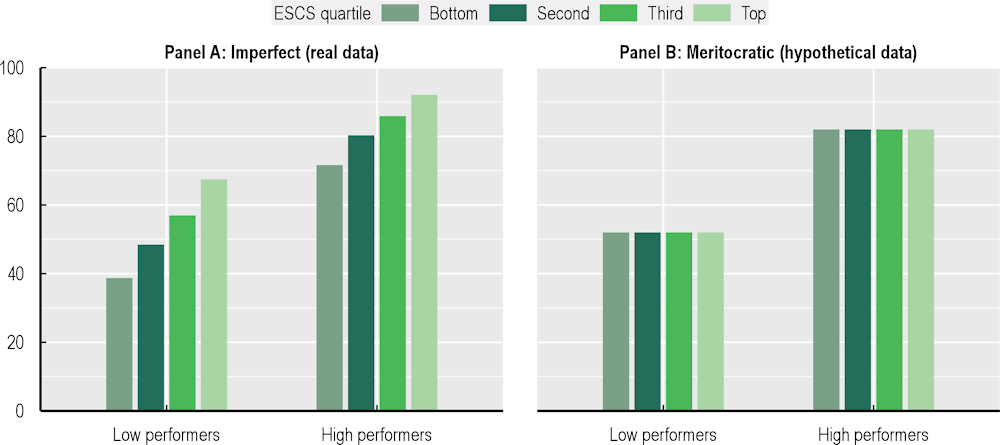

Under this concept, educational outcomes are redistributed based on merit. For instance, the OECD reports the percentage of students who expect to complete tertiary education by the level of their reading performance and socio-economic status (Panel A in Figure 6.1). In 2018, on average across OECD and even within the same reading proficiency level (merit), the expectations depended heavily on the socio-economic background of students. Under a meritocratic distribution, approximately equal levels of expectations within proficiency levels would be expected (Panel B in Figure 6.1). One of the biggest challenges when evaluating equity based on the concept of meritocracy is to find a suitable measurement of merit. Indeed, reading performance might not be the best merit based on which to evaluate equity in expectations to complete tertiary education.

Figure 6.1. Percentage of students who expect to complete tertiary education

Note: ESCS quartile relates to OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS) (OECD, 2019[5]).

Source: OECD (2019[5]), PISA 2018 Results (Volume II): Where All Students Can Succeed, Table II.B1.6.6 and Table II.B1.6.7, 10.1787/b5fd1b8f-en (Panel A).

Minimum standards

The measure of minimum standards focuses on whether some minimum educational outputs are achieved by everyone. For instance, Target 4.1 of the Sustainable Development Goals aims to ensure that all girls and boys complete primary and secondary education by 2030 (United Nations, n.d.[6]). The minimum standard is, in this case, full primary and secondary education completion.

Impartiality

Impartiality quantifies the relationship between an outcome variable and a measure of circumstance. The measure of circumstance can be gender, socio-economic background, immigrant status, etc. For example, the OECD regularly reports PISA reading, mathematics and science scores by gender, socio‑economic and immigrant background (OECD, 2019[5]). Education at a Glance 2021, which specifically focused on equity in education, reported a wide range of outcomes related to participation and progression through education disaggregated by gender, socio-economic status, immigrant background (country of origin) and geographic location (sub-national regions) (OECD, 2021[7]). There is no single way of quantifying the relationship between an outcome variable and a measure of circumstance. Thus, the practice varies from simple disaggregation of student outcomes by groups to more complex estimations of relationships (correlation coefficients or proportion of variance explained by circumstances).

Equality condition

While impartiality focuses on absolute levels of (in)equity, the equality condition is concerned with distribution of educational variables (often resources) across the population. For instance, the OECD reports how various resources hinder instruction (based on school leaders’ reports) across performance or socio-economic groups (OECD, 2020[8]).

Redistribution

Redistribution concerns whether educational inputs are distributed equally or, for instance, unequally to compensate for existing disadvantages. Redistribution is often applied in education finance. For example, in some countries, such as in England (United Kingdom), pay scales for teachers in high‑income areas are higher to compensate for the fact that living expenses there are higher (Department for Education, 2022[9]).

Source: UNESCO-UIS (2018[4]), Handbook on Measuring Equity in Education, http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/handbook-measuring-equity-education-2018-en.pdf (accessed 10 July 2022).

In practice, however, the perspectives taken towards the operationalisation of equity are often narrow and simplified to a disaggregation of student outcomes or an observation of inequalities in students’ performance (e.g., through the standard deviations of students' scores, percentile deviations of students' scores) (Appels et al., 2022[10]). Studies rarely explain what equity involves beyond the disaggregation of student performance, such as the role of schools in counterbalancing inequities, or the interactions between student performance, background characteristics, teachers and the broader environment (ibid.).

The importance of monitoring progress in improving equity in education is closely related to the rationale for equitable education in general. As mentioned in Chapter 1, disparities in learning outcomes are related to a range of negative outcomes later in life (UNESCO-UIS, 2018[4]). Furthermore, high inequities in education resulting from a lack opportunities can lead to the misallocation of skills and talent, and thus hinder economic growth (Hsieh et al., 2013[11]; OECD, 2018[12]).

While there is no agreed distinction between the monitoring of progress in improving equity and in improving inclusion, it is possible to differentiate the two by focusing on the conceptualisation in Chapter 1. Based on these definitions, the monitoring of progress in improving inclusion should be broader in focus than for equity. In addition to examining whether all students have equal opportunities to reach their potential, the monitoring of progress in improving inclusion should also focus on how students feel at school, their well-being outcomes and socio-emotional development (Mezzanotte and Calvel, Forthcoming[13]). Inclusion indicators can also examine whether students are truly included in the school setting (e.g., their sense of belonging) or just integrated; and explore the potential barriers students may face with regard to inclusion. One approach to monitoring inclusion is to focus on processes in the education system, in addition to inputs and outcomes (Box 6.2).

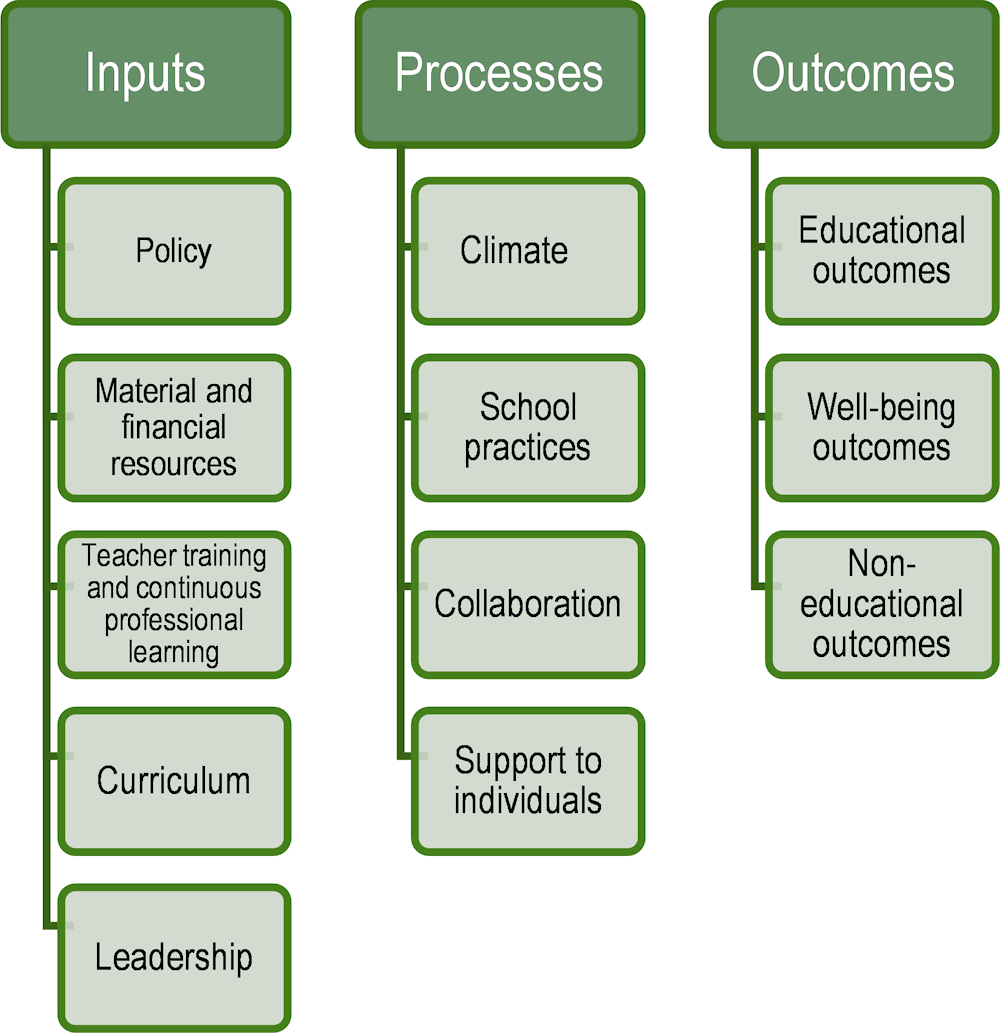

Box 6.2. Inputs-processes-outcomes model

The inputs-processes-outcomes model combines three dimensions to create a comprehensive framework for identifying areas requiring more intervention. Inputs include all sources provided to the system. These include not only financial resources but also policies, teacher training, curriculum and leadership. Processes are practices in schools such as the development of school climate, collaboration or support to individuals. Processes ultimately transform inputs into outcomes. Outcomes include educational outcomes (e.g., participation, dropout, grade repetition rates and achievement), well-being outcomes (such as sense of belonging, mental health and school climate) and non-educational outcomes (for example economic and labour market outcomes, and health outcomes) (Figure 6.2). By focusing on inputs and processes in addition to outcomes, the model can shed more light on the potential causes for regressed outputs.

The inputs-processes-outcomes model allows for the monitoring of progress in relation to both equity and inclusion. By focusing on outcomes, it can measure, for instance, how educational well-being or non-educational factors differ by student groups. The process dimension of the model goes beyond educational outcomes and examines factors such as school climate, collaboration and the support individuals – and can thus, to some extent, show whether the system has the capacity to adjust to the needs of the student groups under analysis. The inputs part of the model can shed light on both equity and inclusion: it can show, for instance, the extent to which financial resources are distributed equally to compensate for existing disadvantages but also, for example, whether curricula are truly inclusive of all students. The model has been adopted in education, such as in Education at a Glance 2018 (OECD, 2018[14]).

Figure 6.2. Inputs-processes-outcomes model

Source: Adapted from Mezzanotte and Calvel (Forthcoming[13]), Indicators of inclusion in education: a framework for analysis.

The monitoring of progress in improving inclusion also involves a greater emphasis on individual experiences rather than those of groups or categories (UNESCO, 2020[15]). Indeed, the more inclusive a school is, the less it needs to use categorical data given that fewer students require identification or support (ibid.). School-level approaches towards monitoring the progress in improving inclusion might thus be more appropriate. These are summarised in the section on Supporting schools in improving equity and inclusion practices through evaluation processes.

Data collection practices are diverse

The evaluation of the progress towards reaching inclusion and equity goals cannot happen without robust data collections that monitor the access, participation and achievement of all learners. This can include monitoring across specific groups (by gender, immigrant background, SEN, socio-economic or ethnic/Indigenous background, giftedness, and sexual orientation and gender identity) as well as various student outcomes.

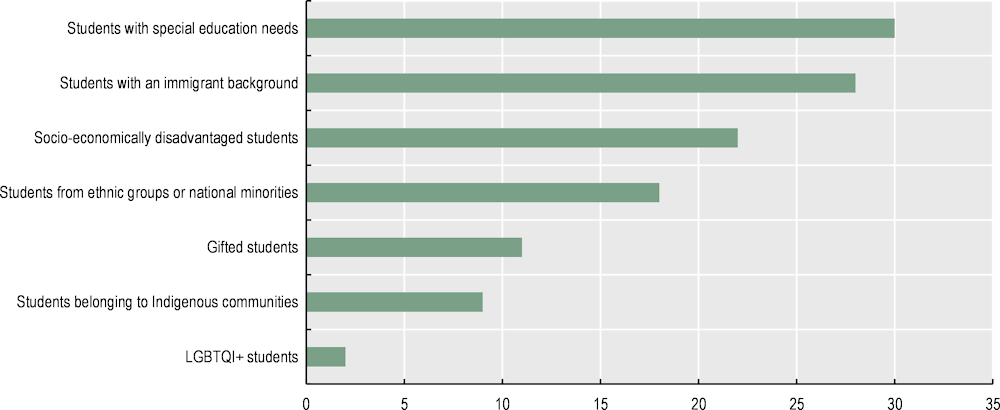

The Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 20221 indicates that a range of student groups are included in the national data collections of education systems across the OECD. Thirty education systems reported collecting data on students with SEN, 28 systems on students with an immigrant background, 22 on socio‑economically disadvantaged students, 18 on students from certain ethnic groups or national minorities, 11 on gifted students and nine on students belonging to Indigenous communities. Only Canada and Chile collected data on LGBTQI+ students (Figure 6.3).2

Figure 6.3. Data collections on diversity (2022)

Note: This figure is based on answers to the question "Does a national (or sub-national) authority collect data on these groups of students at ISCED 2 level?". Thirty-one education systems responded to this question. Response options were not mutually exclusive.

Options selected have been ranked in descending order of the number of education systems.

Source: OECD (2022[16]), Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022.

Some dimensions of diversity (namely, giftedness, sexual orientation and gender identity) are underrepresented in data collections, as is acknowledged in international research (McBrien, Rutigliano and Sticca, 2022[17]; Rutigliano and Quarshie, 2021[18]). There are a range of reasons why data for particular dimensions of diversity may not be collected at the national (or sub-national) level. Legislative frameworks in some countries may not allow for the collection of some characteristics (e.g., sexual orientation) due to the private and sensitive nature of such data. Some education systems, such as Portugal (Box 6.3), do not categorise students based on their characteristics but instead focus on the support measures they require. Other education systems adopt colour‑blind policies whereby data on certain characteristics, such as ethnic background, are prohibited to be collected by law (see the next section).

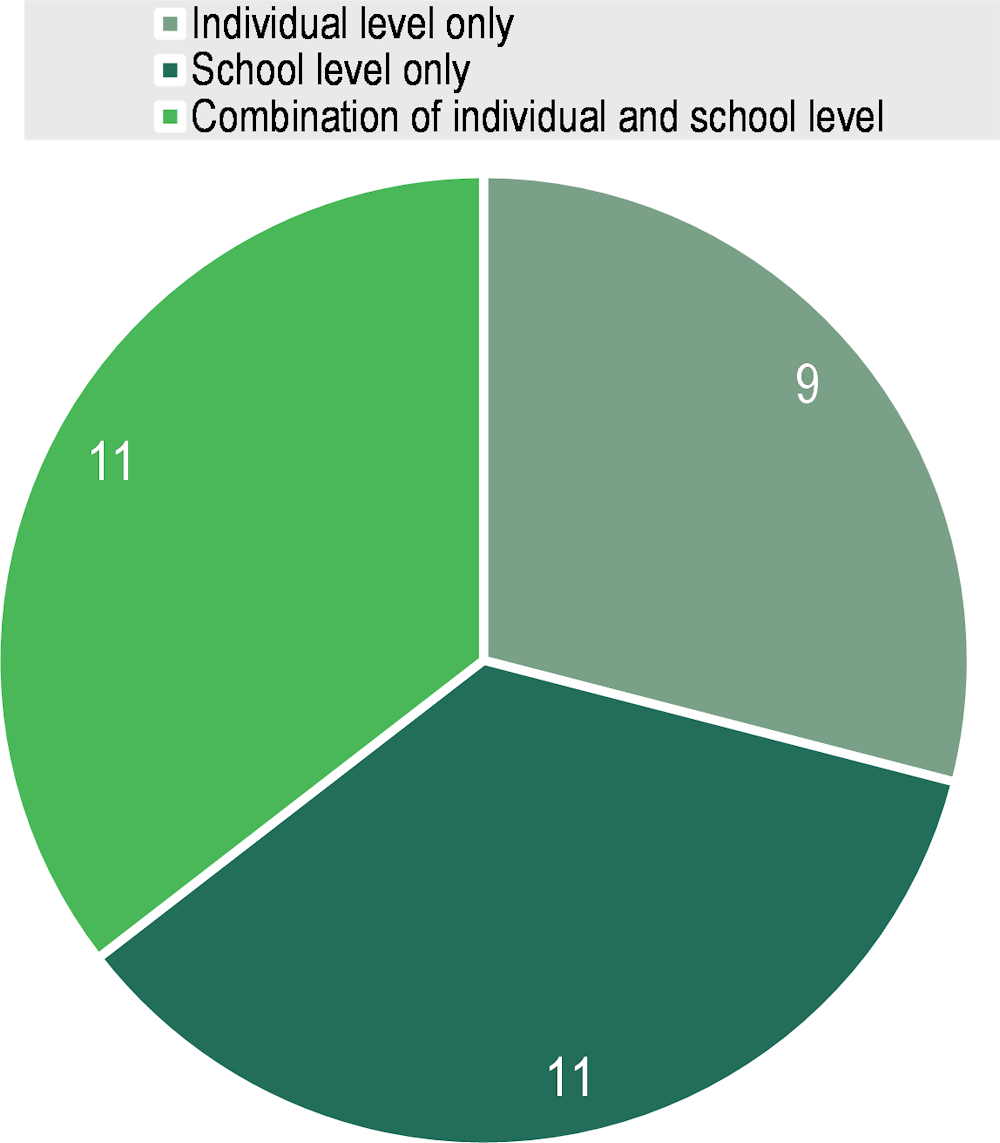

The methods for collecting data also differ across education systems. Some national (or sub-national) authorities collect data at the individual student level while others at an aggregated (e.g., school) level. Individual-level data collections mean that data is collected about each student and then sent to a national (or sub-national) authority. Aggregated level data means that data is sent to a national (or sub-national) authority in aggregates. For instance, each school sends the total number of students with an immigrant background, rather than data on each student’s immigration status (which would be collected in an individual-level approach).

Results from the Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022 show that aggregated collections were more common as a means for gathering data compared to individual-level data collections (Figure 6.4). Data was reported as being collected solely at an aggregate level in 11 education systems and solely at the individual level in nine systems. In 11 systems, the level of data collection differed depending on the student characteristic.

Figure 6.4. Type of data collection (2022)

Note: This figure is based on answers to the question "Does a national (or sub-national) authority collect data on these groups of students at ISCED 2 level? If so, are data points collected on an individual student level or aggregated on e.g., school level?". Thirty-one education systems responded to this question.

Source: OECD (2022[16]), Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022.

Individual-level data collections enable policy makers to consider intersectionality in their analyses and policy implications. Aggregated data are only as applicable for an intersectional analysis as they are set up during the collection. For example, a country with aggregated data collections would only be able to know the number of female students with an immigrant background if it specifically asked for that particular number and dimensional intersection from each school. On the other hand, by collecting individual-level data with attributes on both gender and an immigrant background, it is straightforward to create aggregate statistics for the intersection.

Practices around labelling diverse students differ

Labelling students with a particular need, ethnicity or other type of background can have both positive and negative impacts. Labelling is viewed as advantageous by some teachers: classification can help to identify and explain the limitations and potential negative consequences of current practice. For example, some teachers feel that student Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) classifications can help explain why regular practice does not suffice and legitimates a different approach (Mezzanotte, 2020[19]; Wienen et al., 2019[20]). Classifications can also bring consistency to research and communication, and can be useful in the assessment and placement of students in special programmes or settings (OECD, 2022[21]; Thomson, 2012[22]). For some typologies of SEN, the label can also bring some “relief” to students or parents, who can then better understand the driver of certain difficulties or struggles at school. Diagnosis or clarification can thus explain the causes of student behaviour, bring empathy and offer resolution (Mezzanotte, 2020[19]; Wienen et al., 2019[20]).

The absence of student labels can also make some students invisible to policy makers and can silence the experiences of diverse groups (Öhberg and Medeiros, 2017[23]; Simon, 2017[24]). After all, if data is not collected, no gaps can be seen. This may cause stakeholders in the education system to remain or become ignorant of the needs of some students. In the Netherlands, students with SEN are not labelled as such and individual schools are meant to monitor the progress of students with a “progress and development plan” (Inspectorate of Education, 2022[25]). However, while individual schools might have a good overview of these students, national data are of poor quality (ibid.). An accurate picture of the trends in the number of students with SEN (with a progress and development plan) and their outcomes in and through education is therefore limited (ibid.). In the Slovak Republic, it was estimated that due to limits in data collections on “disadvantaged socio-economic background”, only 39% of students at risk of poverty or social exclusion have been targeted by financial contributions for disadvantaged students (Hellebrandt et al., 2020[26]). In the area of intersectionality, research points out that the often reported gender gap in learning outcomes varies significantly by socio-economic status or the ethnicity of students (OECD, 2019[5]; Strand, 2014[27]). However, these kinds of intersections of students’ identities and heterogeneities are often absent in monitoring systems and thus are not considered in policy responses (Varsik and Gorochovskij, Forthcoming[28]).

Opponents to labelling argue that equality and national cohesion of ethnic groups and national minorities is achieved through invisibility, i.e., all are equal before the law without a distinction between ethnic groups (Balestra and Fleischer, 2018[29]; Simon, 2017[24]). Some European countries have on this basis adopted a “colour-blind” approach to data collection on ethnic groups. Under this policy, data on ethnic groups are not collected or, if they are collected, they are not considered in policy making.

Some researchers have also argued that labelling may result in teachers having lower expectations of the performance of certain students due to their preconceptions regarding the abilities of students belonging to diverse groups (Hart, Drummond and McIntyre, 2007[30]). Labelling may in this way result in students not being viewed as individuals but judged based on stereotypical preconceptions (OECD, 2022[21]; Osterholm, Nash and Kritsonis, 2007[31]). According to some teachers, labelling also has no value for educational practice without a further analysis of the student needs (Mezzanotte, 2020[19]; Wienen et al., 2019[20]). Furthermore, by labelling students, teachers and other stakeholders in the system might focus on deficits of students, rather than directing their attention as to how the system can help underperforming students (Ainscow and Messiou, 2017[32]). Finally, in the context of inclusion of students, inclusion cannot happen one group at a time; the process must encompass all students (UNESCO, 2020[15]). From this standpoint, data disaggregated by characteristics might seem irrelevant. As a result, some education systems are changing their approaches in order to limit the potentially negative consequences of labelling (Ebersold et al., 2020[33]). In Portugal, for example, students are no longer categorised by their characteristics (ethnic or immigrant background, SEN etc.), but by the type of educational support measure(s) they need (Box 6.3).

Box 6.3. Reform and monitoring of inclusive education in Portugal

As part of this legislative changes since 2018, Portugal shifted its emphasis from identification of student characteristics to identification of student support measure(s). Portugal no longer collects information on student characteristics (except for gender and nationality) on the rationale that it is not necessary to categorise in order to intervene. The identification of students’ needs happens at the school level and is conducted as early as possible in co-operation with a range of stakeholders including parents/guardians, social services or relevant teaching as well as non-teaching staff. The initial identification is followed by an approval for assessment and mobilisation of a multidisciplinary team. The team is also responsible for implementation and monitoring of the support measures.

As a result, the system collects information on students falling into one of three categories of support measures: universal measures, selective measures and additional measures. A student in each category can benefit from a wide spectrum of interventions ranging from curriculum accommodation/enrichment, tutoring, pedagogical-psychological support to redesigning of the pedagogical strategy, including significant curricular adjustments.

Portugal has co-operated with the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education to develop a monitoring system that will enable stakeholders to assess the effectiveness of the inclusion law. This new monitoring system was developed in 2022 and consists of six standards, 11 indicators and 19 related questions that monitor the level of implementation of the identified standards (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2022[34]).

Source: OECD (2022[21]), Review of Inclusive Education in Portugal, https://doi.org/10.1787/a9c95902-en.

Finally, identifying groups at an aggregate level might be required for other purposes than targeted support, such as maintaining statistical databases or allocating resources. As elaborated in Chapter 3, almost all education systems that provided answers to the Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022 reported accounting for various student backgrounds in their funding formulas. These labels may not impact how teachers view their students. In fact, assigning a label based on administrative data can occur without assigning the same label in the classroom (UNESCO, 2020[15]). In Finland, for instance, diagnostic labels are not used in the classroom, because the system focuses on the needs of individual students, regardless of their characteristics. For administrative purposes, however, certain statistics can be disaggregated by student groups, such as those of students with physical impairments (Jahnukainen and Itkonen, 2010[35]).

Monitoring mostly focuses on academic outcomes

The lives and experiences of students are shaped by a range of factors. Apart from learning, students also spend a considerable time at school socialising with their peers and interacting with school staff. Academic outcomes are only one aspect of the overall school experience, and it is important to understand how happy and satisfied students are with different aspects of their life, how connected they are to others and whether they enjoy good physical and mental health (Cerna et al., 2021[2]). This understanding can be developed through collecting data on a range of student well-being outcomes, including academic, psychological, physical, social and material (ibid.). These dimensions are key ingredients of the concurrent well-being of individuals and contribute to their personal development in the short-, medium- and long-term (ibid.).

The Strength through Diversity Project considers multiple aspects of student well-being: academic, psychological, physical, social and material (Cerna et al., 2021[2]). The psychological dimension of students’ well-being includes students’ views about life, their engagement with school, the extent to which they have a sense of agency, identity and empowerment, and their opportunities to develop goals and ambitions for their future. Physical well-being relates to students’ health status, safety and security, the ability to engage with others without physical barriers in access and mobility. Social well-being refers to the quality of students’ social lives. This includes relationships with peers, family and school staff. Finally, material well-being considers the material resources available that enable families and schools to cater to students’ needs.

However, despite growing research on the positive associations between high levels of student well-being and positive and fulfilling life-experiences (Pollard and Lee, 2003[36]), performance (Gutman and Vorhaus, 2012[37]) and negative associations with risky behaviours (such as drinking and smoking) (Currie et al., 2012[38]), schooling is in many education systems organised with the aim of maximising learning outcomes, sometimes at the expense of overall well-being. This is reflected in data collections, which tend to focus on learning outcomes, with comparatively little attention given to indicators of other aspects of well-being.

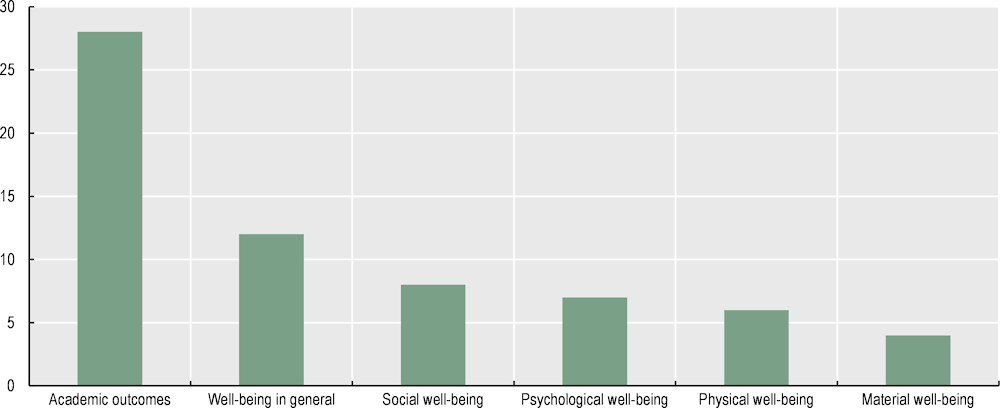

Most education systems (28) who participated in the Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022 reported focusing their official data collections on academic outcomes for students irrespective of specific groups (Figure 6.5). While 12 systems collected data on general well-being outcomes, collecting data on specific types of well-being was less common for students irrespective of specific groups. Eight education systems considered social well-being, seven systems psychological well-being and six physical well-being in their data collections. Material well-being outcomes were rarely included in national or sub-national data collections (with only four education systems reporting that they collected data on this aspect of well-being).

Figure 6.5. Data collections on students irrespective of specific groups (2022)

Note: This figure is based on answers to the question "Which dimensions of student outcomes are nationally (or sub-nationally) collected at least once during ISCED 2 level? [Students irrespective of specific student groups]". Thirty-one education systems responded to this question. Response options were not mutually exclusive.

Options selected have been ranked in descending order of the number of education systems.

Source: OECD (2022[16]), Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022.

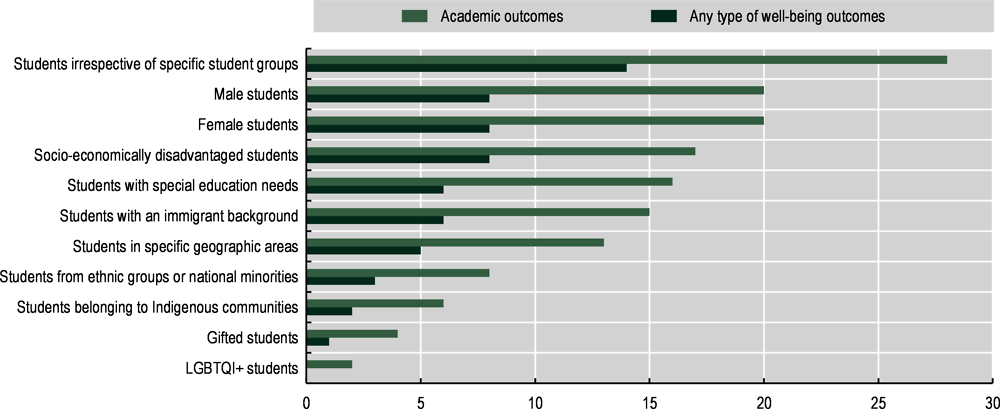

Education systems most commonly reported collecting data on the academic and well-being outcomes of students irrespective of specific groups (Figure 6.6). The dimensions of diversity that were most common in group-focused data collections were gender, socio-economic and immigrant background, SEN, and location in specific geographic areas. Only eight and three education systems collected academic and well‑being data respectively for students from ethnic groups or national minorities. Six and two systems collected academic and well-being data respectively on students belonging to Indigenous communities and data collections on gifted and LGBTQI+ students were even rarer. For all student groups, data on any type of well-being outcomes were collected considerably less often than data on academic outcomes.

Figure 6.6. Data collections on academic and well-being outcomes (2022)

Note: This figure is based on answers to the question "Which dimensions of student outcomes are nationally (or sub-nationally) collected at least once during ISCED 2 level?". Thirty-one education systems responded to this question. Response options were not mutually exclusive. Any type of well-being outcomes can include one or more of the following: psychological well-being outcomes, social well-being outcomes, material well-being outcomes, physical well-being outcomes, well-being outcomes in general.

Options selected have been ranked in descending order of the number of education systems that selected any type of well-being outcomes.

Source: OECD (2022[16]), Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022.

This trend is also visible in international research. In many education systems, student experiences at school remain unmonitored. For instance, systematic data collections on anti-LGBTQI+ bullying in schools are in place in only four countries (Finland, France, the Netherlands and Sweden), despite the fact that LGBTQI+ students are consistently reporting higher rates of bullying compared to their peers (IGLYO, 2022[39]; McBrien, Rutigliano and Sticca, 2022[17]). Furthermore, those collections often differ in the extent of detail they cover. In Sweden, for instance, the school inspectorate monitors bias-motivated bullying in schools that can be based on the sexual orientation or gender identity of the victim (IGLYO, 2022[39]). In other countries, however, the data is less detailed and more generic (McBrien, Rutigliano and Sticca, 2022[17]).

Instruments used to measure progress towards equity and inclusion

Data can be used by policy makers and other stakeholders to monitor progress, evaluate outcomes and ultimately improve students’ learning and other well-being outcomes. One common approach to summarising data collections comes in the form of indicator frameworks. Other instruments include the use of national assessments with background data, national or international longitudinal and key stakeholder surveys, and specific reviews on equity and inclusion.

Data collections happen within an educational context under different policy regimes. As a result, the methods for collecting data differ across education systems and no country uses a single instrument to measure progress towards equity and inclusion. Most often the approaches are combined. For instance, results from national assessments and surveys are often used in indicators frameworks and specific reviews on equity and inclusion.

Indicator frameworks

The joint international standardised data collection by UNESCO, OECD and EUROSTAT has been a major driver of the collection of international information on equity in education. The data are summarised in indicators and published in various reports, including Education at a Glance, which focuses on equity and inclusion in education every three years (most recently in 2021) (OECD, 2021[7]). The OECD has published a number of reports that focus on equity in and beyond education, although these mainly focus on disparities in terms of socio-economic background, gender, immigrant background and geographic location (e.g., in terms of urban/rural differences) (OECD, 2012[40]; OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2018[14]). Performance scores are often disaggregated by one or more dimensions of diversity. The effect of socio‑economic background on performance is often examined: as score-point difference in performance associated with one-unit increase in the index of economic, social and cultural status, or percentage of the variation in performance explained by the index (OECD, 2019[41]). Beyond education, indicators focus on labour market outcomes, such as earnings or labour market participation by educational attainment (OECD, 2018[14]). Data on adult skills or educational attainment by socio-economic background are also often reported (OECD, 2017[3]). More recently, the OECD engaged in developing a dashboard of indicators on equity in and through education (Box 6.4).

A key challenge is designing indicators in a way that adequately represents the value they are measuring. While national education goals and objectives may be comprehensive and broad, monitoring systems may be rather limited in the information they can offer. For instance, as was elaborated in the previous sections, measures of inclusion need to collect a wide range of data outside of the domain of learning outcomes. These may not be available, challenging and costly to obtain if new data sources and data infrastructures need to be created. In some areas, such as quality of the teaching force, data might not even be possible to obtain. In this context, it is difficult to create indicator frameworks that are feasible, reliable, with high coverage and validity (OECD, 2013[1]). It is therefore important to consider the purpose of each indicator so that it designed in a considered manner with the goal to measure what is valued, rather than value what is measured (Ainscow, 2005[42]). That way, policy makers and other stakeholders can limit the possibility that the measure itself becomes the target.

Box 6.4. Dashboard of indicators on equity in and through education

In 2022, the OECD engaged in developing a dashboard, whose objective was to position OECD countries across a range of indicators on equity in and through education. The dashboard has two overarching aims and five policy aims. The overarching aims are: (1) enabling all learners to developing the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values to thrive in equitable and inclusive societies; and (2) ensuring that education contributes to equitable economic and social outcomes. The five policy aims include: (a) raising educational outcomes through more equitable education opportunities; (b) investing in the early years; (c) empowering teachers and school leaders to support equity in and through education; (d) aligning resources with the needs of learners; and (e) enabling an inclusive school environment. As a result, equity in and through education is measured using 35 key comparative indicators often disaggregated by age, gender and socio-economic status.

In the process of the dashboard development, the OECD also identified several gaps and limitations in the existing data. These included a lack of information on the early years of education, particularly in terms of country coverage, teacher quality and teaching practices. Data on the quality of initial education and continuous professional learning for teachers and school leaders was also generally hard to find. Challenges were also visible in measuring equity throughout the student’s education, especially when focusing on enrolment in, access to and graduation from upper secondary and tertiary education by students’ characteristics.

Some important areas could not be covered due to lack of information or data based on subjective students’, teachers’ or school leaders’ reports. These areas include attitudes and values of students and young adults, skills to thrive in a digital world and on socio-emotional skills, social outcome indicators (civic engagement, for instance), and engagement with parents and communities. Other highlighted challenges included the timeliness of data (e.g., the Survey of Adult Skills, a product of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), is relatively old), lack of data focusing on inclusion as a process, and insufficient data on ethnic groups, refugees, LGBTQI+ students, gifted students and students with SEN.

Source: OECD (2022[43]), Dashboard of indicators on equity in and through education, OECD document for official use, EDU/EDPC(2022)20/ANN.

Reference points for measuring progress in advancing equity and inclusion

At the national (or sub-national) level, many education systems embed indicators into strategies, action plans or national improvement frameworks that set out goals for equity and inclusion. This can be done to monitor progress, and clarify the vision and objectives of the administration, while reducing and aggregating the abundance of available information to several key elements (Gouëdard, 2021[44]). Furthermore, by including an equity component in the strategy (e.g., disaggregation of outcomes by dimensions of diversity), the success of the policy can also be measured in relation to specific student groups.

New Zealand’s Child and Youth Well-being Strategy, for instance, measures progress towards six defined well-being outcomes (and equity in relation to those outcomes) (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2020[45]). In education, these cover participation, attendance, literacy, numeracy, science skills, socio-emotional skills and self-management skills. In Japan, the Third Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education (2018-22) focuses on well-being outcomes (OECD, 2019[46]). These include improvement in “the percentage of students in [primary and secondary] schools who do not eat breakfast” or improvement in “the percentage of students in [primary and secondary] schools who go to bed at around the same time every day and who wake up at around the same time every day” (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 2018[47]). In many cases, the strategies also include more specific instruments that measure the progress towards equity and inclusion.

Goals related to equity and inclusion are also central to the Scottish (United Kingdom) National Improvement Framework, with the specified key priorities including closing the attainment gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students, improving students’ health and well-being, and placing the human rights and needs of every child and young person at the centre of education. These key priorities reflect the vision for education specified in the Framework, which is to deliver both excellence and equity, ensuring that every child and young person is able to thrive and has “the best opportunity to succeed, regardless of their social circumstances or additional needs” (Scottish Government, 2021[48]). Similarly, in Latvia, ensuring equal opportunities is one of the strategic objectives of Latvia’s National Development Plan for 2021-2027 (Cross-Sectoral Coordination Center, 2020[49]).

National curricula can serve as reference points, given that countries often use national assessments to monitor the implementation of the national curriculum and/or progress against specific student learning objectives or educational standards (OECD, 2013[1]). National curricula can also articulate equity and inclusion as overarching goals for education to ensure that the value of equity is both taught and modelled in schools (OECD, 2021[50]). In Estonia, for instance, the values of “honesty, compassion, respect of life, justice and human dignity” are embedded in the national curriculum across various themes (OECD, 2021, p. 95[50]).

Education systems define a wide range of indicators

Indicators often include targets that can help instigate action. Targets can help policy makers identify the biggest gaps, quantify how much action is needed in different priority areas and monitor progress over time. If a strategy contains a specific target value for a policy or a set of policies, policy makers and other stakeholders can use it to evaluate whether the goals were met.

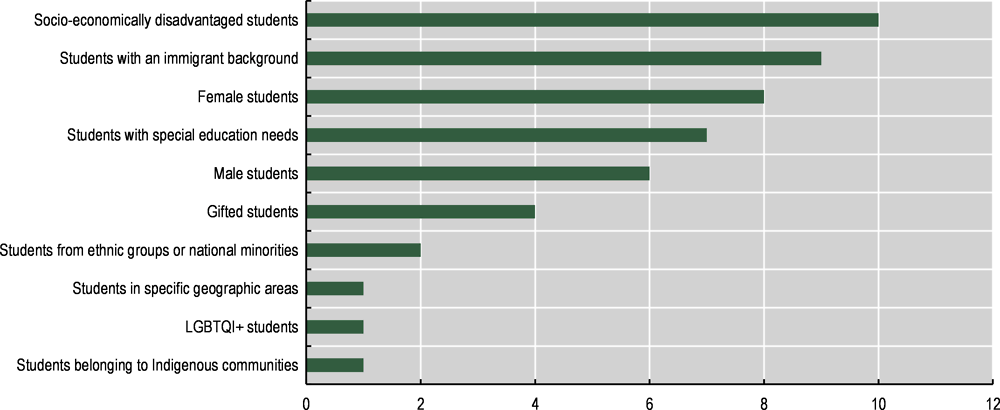

The results of the Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022 show that most OECD education systems did not define indicators specific to student groups (Figure 6.7). The indicators that were reported focused on equity and mostly measured impartiality (Box 6.1), i.e., whether educational outcomes differ for various student groups. Most education systems defined indicators with a focus on socio-economically disadvantaged students (ten systems), with an immigrant background (nine systems), female or male students (eight and six systems respectively), and students with SEN (seven systems). Four education systems reported having indicators specific to gifted students, and two systems specific to ethnic groups or national minorities. The other dimensions of diversity were represented even less often.

Figure 6.7. Indicators (2022)

Note: This figure is based on answers to the question "Does your education jurisdiction define nationally (or sub-nationally) indicator(s) specific to any of the groups of students at ISCED 2 level?". Twenty-five education systems responded to this question. Response options were not mutually exclusive.

Options selected have been ranked in descending order of the number of education systems.

Source: OECD (2022[16]), Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022.

Where education systems had indicators related to students with an immigrant background, these mostly examined their school participation rates and results (OECD, 2022[16]). Iceland and Spain reported monitoring immigrants’ results based on international large-scale surveys, such as the PISA, with Iceland having set a target for students with an immigrant background to reach the OECD PISA average in reading, mathematics and science (OECD, 2022[16]). Targets in Latvia focused on full participation of minors who were granted asylum status and children of returning migrants, and in Lithuania on full participation of citizens of foreign countries.

Education systems reported monitoring students with SEN and gifted students largely in terms of whether they were labelled as such, which educational setting they were placed in (e.g., dedicated or mainstream schools) and whether they had received specific educational support (OECD, 2022[16]). In Spain, for instance, the indicators focus on the number of students with SEN and gifted students in education disaggregated by the typology of SEN, gender and the type of school. In Lithuania, targets are set for the proportion of students whose needs for additional support are met (85% in 2025 and 97% in 2030) as well as proportion of students with disabilities receiving inclusive education in mainstream education settings (85% in 2025 and 90% in 2030).

Socio-economically disadvantaged students were also explicitly targeted with indicators in some instances (OECD, 2022[16]). In England (United Kingdom), the education system monitors the disadvantaged gap index. It summarises the relative attainment gap between disadvantaged students and all other students. In Scotland (United Kingdom), achievements in the expected level in literacy and numeracy are reported by socio‑economic background of students. Moreover, broader well-being outcomes are monitored, particularly as a potential consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic: the gap in total difficulties score between students (aged 13 and 15) in the most deprived and least deprived areas.3

Other education systems reported monitoring disadvantaged students indirectly (OECD, 2022[16]). One of the indicators in the Flemish Community of Belgium focuses on early leavers from education and training developed by EUROSTAT.4 In Latvia, the provision of portable computer equipment for disadvantaged students is monitored as part the 2021-3 Action Plan of the Education Development Guidelines 2021-7.

Indicators targeting gender gaps often focus on academic outcomes (OECD, 2022[16]). In Iceland, the percentage of female and male students reaching level 2 or higher in PISA in reading, mathematics and science are monitored, with targets being set for the year 2025 for each subject and gender. In Northern Ireland (United Kingdom), mid-upper secondary examination results are reported as being disaggregated by gender. In Estonia, drop-out rates from lower secondary education are monitored by gender, while the participation of girls in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) programmes are monitored in the Flemish Community of Belgium and Ireland.

Two education systems (Chile and the Slovak Republic) reported having indicators related to students from ethnic groups and national minorities and one education system had indicators related to students belonging to Indigenous communities. In the Slovak Republic, the “Roma Strategy of Equity, Inclusion and Participation” sets the target of decreasing the number of Roma early school leavers by half (to 36%) and decreasing the number of Roma students attending ethnically homogenous classes by half (to 30%) by 2030 (OECD, 2022[16]).

Finally, some education systems reported having developed indicator frameworks related to Indigenous peoples. Such indicators are, for instance, set out in Australia’s “Closing the Gap” framework, which was developed to close the gap between Indigenous peoples and the majority population in areas such as child mortality, early childhood education, school attendance, literacy and numeracy, upper secondary education attainment, employment, and life expectancy (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020[51]). For each of these areas, there is a clearly stated target provided with a timeframe (e.g., “95 per cent of all Indigenous four‑year-olds enrolled in early childhood education (by 2025)”) and progress with relevant statistics documented. Data is also provided at the provincial level.

National assessments with background data

In 2015, 27 and 30 out of 38 surveyed OECD systems administered national assessments or examinations during primary and upper secondary levels (general programmes), respectively (OECD, 2015[52]). National assessments and examinations are standardised student achievement tests. While national assessments do not affect students’ progression through school or certification, national examinations have a formal consequence for students, such as an impact on a student’s eligibility to progress to a higher level of education or to complete an officially-recognised degree (ibid.). The uses as well as methods for administering the national assessments and/or examinations varied across education systems. The main purpose of national assessments at lower secondary level was to provide teachers with student diagnostic information and the main purpose of national examinations at the upper secondary level was to determine student entry to tertiary education (ibid.). National assessments/examinations also varied greatly in terms of the subjects covered and whether they were administered to all students or just a sample (ibid.).

While sample-based surveys generally suffer from shrinking samples and larger estimation errors as the focus shifts to individuals with multiple specific characteristics (UNESCO, 2020[15]), national assessments/examinations are often administered to the full cohort of students, giving way for analyses that explore the outcomes of groups of students that have very low populations. However, various factors have an impact on student results and countries exercise caution when publishing disaggregated outputs. Analyses with an intersectional focus that consider multiple dimensions of diversity are thus rarely applied. When conducted, these revealed, for instance, that SEN identification is heterogeneous across various dimensions of diversity. Disadvantaged students aged 5-16 were approximately twice as likely to be identified with SEN in England (United Kingdom), controlling for gender and ethnic background (Strand and Lindorff, 2018[53]; Strand and Lindsay, 2008[54]). Boys were more likely to be identified with SEN compared to girls, controlling for ethnic and socio-economic background (Strand and Lindorff, 2018[53]; Strand and Lindsay, 2008[54]).

Comprehensive information on the extent to which assessments include background data of students is not available. The results from the Strength through Diversity Policy Survey 2022 on data collections on diversity (Figure 6.3) indicated that some dimensions of diversity, such as sexual orientation or gender identity, were collected to a much lower extent (if at all) than others. Indeed, gender and geographic locations are two characteristics that are often used to present results from student assessments. For instance, Italy and Poland publish results from their student assessments disaggregated by gender and geographic location (Central Examination Commission, 2019[55]; INVALSI, 2022[56]). Some education systems publish information from student assessments by a range of other categories. In England (United Kingdom) results of student assessments at the upper secondary level are published by SEN, ethnicity and socio-economic background (determined on the basis of free school meals eligibility) in addition to gender and geographic location (Department for Education, 2022[57]). Estonia publishes results of the state examination by students’ language of instruction, including sign language, gender and geographic location (Examination Information System, 2022[58]). The Slovak Republic publishes selected results from the lower secondary student assessment disaggregated by gender, socio-economic background, type of school and geographic location (NUCEM, 2022[59]).

Some students, such as students who arrived in the country during the school year in which they would normally be tested or less than one year beforehand, or students with SEN (particularly if they are enrolled in dedicated schools), might be excluded from participation in nation-wide assessments (European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Eurydice, 2011[60]). Exclusion of students from assessments may result in limited data on the progress of these student groups at the national (or sub-national) level. Sometimes, education systems make accommodations to the tests so that participation increases. For instance, several education systems provide tests in Braille or enlarged letters for students with visual impairments, or adapted material for pupils with physical disabilities (ibid.). For those with more severe typologies of SEN, students can also have an assistant, interpreter or special teacher at disposal during testing (European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Eurydice, 2011[60]; Hellebrandt et al., 2020[26]). Other accommodations include more time to take the test, more frequent breaks during testing, and the use of various forms of support (including magnifying glasses, special reminders or information leaflets, etc.) (European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Eurydice, 2011[60]). Finally, computer-based assessments can, in some instances, improve the accessibility of the test for some students with SEN, given that computerised accessibility tools can be incorporated into the assessment platform, as was recently done in the Pan-Canadian Assessment Programme (Council of Ministers of Education Canada, 2019[61]).

Publication of national assessment results: impacts on equity

National assessments and examinations are sometimes also used with the additional purpose of holding schools accountable. A common approach in this regard is to make aggregated school results publicly available. The provision of information could, in theory, achieve two outcomes: (1) lower the information asymmetry about overall student performance between school insiders and outsiders (e.g., parents, national (or sub-national) authorities); and (2) provide incentives to align the actions taken by school leaders with those set by governing bodies or national (or sub-national) authorities by focusing on pre‑defined standards, subjects or contents that are measured (Torres, 2021[62]). While the impact of publication of school results has been shown to be positive on the average academic achievement, the evidence is mixed in regards to the impacts on equity in education (Hanushek and Raymond, 2005[63]; Torres, 2021[62]). On the one hand, school accountability systems were correlated with lower overall results for low-performing students in secondary education and increased gaps between majority and minority ethnic groups in England (United Kingdom) and the United States (Burgess et al., 2005[64]; Hanushek and Raymond, 2005[63]). On the other hand, student assessments can have positive consequences for equity in education if they are used to improve awareness of the main challenges in the education system of for particular students (OECD, 2020[8]). Positive correlations were observed between equity in education and the use of student assessments to inform parents about their child’s progress; the use of student assessments to identify aspects of instruction or the curriculum that could be improved; and the use of written specifications for student performance on the school’s initiative. Higher equity in education was also observed among countries that used assessments to seek feedback from students and to have regular consultations on school improvement (ibid.). Finally, studies showed no substantial impact of test-based accountability practices on educational inequalities (Torres, 2021[62]). For instance, the publishing of school results in Japan did not reveal adverse distributional effects on student performance (Morozumi and Tanaka, 2020[65]).

Depending on how they are designed, the publishing of school results can have unintended consequences with negative implications for equity and inclusion in education (Torres, 2021[62]). These can include increased social segregation among schools (due to parents choosing to enrol their children in better‑performing schools) (Davis, Bhatt and Schwarz, 2015[66]), focusing teachers’ attention only on the measured subjects, or only on the students who have a realistic chance of passing a given proficiency threshold (Neal and Schanzenbach, 2010[67]). They may also result in teachers focusing on preparing students to “sit the test” rather than the entire curriculum (Jennings and Rentner, 2006[68]). Creating league tables can also cause difficulties in recruiting and retaining teachers in low-performing schools (Clotfelter et al., 2004[69]).

Previous studies have suggested that accountability should not only apply to learning outcomes, but also to school resources, professional capacity and other school processes (Darling-Hammond and Snyder, 2015[70]). The rationale is that schools’ outcomes need to be compared only if other aspects of the schooling process are considered, including resourcing and the (quality of) the teaching force (Torres, 2021[62]).

Longitudinal surveys

Longitudinal surveys use administrative data or specialised sample-based surveys to track the same people over time. The biggest advantage of longitudinal population surveys is that they can better determine patterns over time because changes can be observed for the same individuals. In contrast, cross-sectional surveys only provide snapshots of a given situation in time.

Education authorities in several countries co-operate with academic institutions or non-governmental organisations to administer longitudinal surveys. For example, the Millennium Cohort Study, Next Steps and Our Future longitudinal surveys have been conducted by higher education institutions and social research organisations with funding and in co-operation with several governmental departments in the United Kingdom (Centre for Longitudinal Studies, n.d.[71]; Centre for Longitudinal Studies, 2022[72]; CLOSER, n.d.[73]). The surveys offer a wealth of data that can be used for various group comparisons and intersectional analyses related to education and other areas (e.g., health, labour market outcomes). Most of these sources offer information on gender, SEN, ethnic and socio-economic background and some also on immigrant background and sexual orientation (ibid.). Similarly, the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children and the High School Longitudinal Study in the United States contain information on all dimensions of diversity except giftedness (Australian Institute of Family Studies, n.d.[74]; US Bureau of Labor Statistics, n.d.[75]).

Longitudinal surveys can also be created from administrative datasets that contain a unique student identifier that does not change over time. Since 1996, New Zealand assigns a unique student identifier (the National Student Number, NSN) to each student (NZQA, 2022[76]). This allows for monitoring of student enrolment, attendance and tracking of students’ educational paths. It is also helpful for various statistical purposes, research purposes and ensuring that student educational records are accurately maintained. The availability of NSNs was more recently used to calculate the Equity Index, consisting of 37 variables that measure socio-economic background and educational achievement in upper secondary education examinations (Ministry of Education, 2022[77]). The 37 variables include parental socio-economic indicators (e.g., education level, income, prison custody, mother’s age at her first child), child socio-economic indicators related to poverty, abuse or neglect (e.g., care and protection placement/notification/ investigation of child), national background variables (e.g., country of birth) and transience variables related to moving home or school (e.g., number of home and school changes) (ibid.). Similarly, in the Slovak Republic, the use of unique student identifiers has enabled the monitoring of Roma students’ participation in education (from the primary to tertiary levels), and allowed for the analysis of early school leaving rates disaggregated by Roma/non-Roma as well as socio-economically advantaged/disadvantaged populations (Hellebrandt et al., 2020[26]). The use of unique student identifiers has also enabled researchers to compare the educational outcomes of both Roma students and students from socio-economically disadvantaged groups (excluding Roma) with those of the general population and to analyse issues such as within- and between-school segregation and the unequal distribution of SEN identification (ibid.). In Chile, the Provisional School Identifier allows for monitoring and continuity in the educational trajectories of students including those of foreign nationality, and also enables the certification of their studies (Ministry of Education, 2022[78]).

Key stakeholder surveys

Information regarding students’ psychological, physical, social and material well-being outcomes are sometimes collected using surveys based on a sample. Such key stakeholder surveys can be used to broaden the evidence on student outcomes to domains that are outside of academic outcomes. Representative sample-based surveys can provide an overall picture of well-being outcomes, while limiting the administrative costs of running a full-population study. The disadvantage is, however, that analyses of student sub-groups is limited by the sample size. This is a particularly pressing issue in quantitative research focusing on intersectionality, where, by definition, researchers need data on students belonging to several sub-groups. Such two-, three- or more dimensional intersections, however, have often extremely small number of observations.

Statisticians have developed several techniques that can ensure representativeness while avoiding low cell counts for certain intersections: stratified random sampling, and purposive, quota or snowball sampling (Else-Quest and Hyde, 2016[79]). Under stratified random sampling, the population is first divided into sub‑groups (e.g., intersections) from which individuals are randomly sampled. Purposive, quota or snowball sampling, while no longer representative, are more suitable for qualitative methods, whereby participants are recruited to be typical of the population of interest through networks or by asking research participants to refer eligible peers (Scottish Government, 2022[80]).

The OECD Survey on Social and Emotional Skills uses stratified random sampling and provides reliable and comparable insights at an international level for policy makers and educators on how social and emotional skills relate to key life outcomes (OECD, 2021[81]). The survey collects information on environments at home, in school, among peers and other background characteristics (including gender, immigrant and socio-economic backgrounds) to analyse the complex interactions between these factors and student well-being outcomes. Similarly, the New Brunswick Student Wellness Survey in Canada allows for comparisons of some aspects of psychological, physical, social and material well-being disaggregated by several dimensions of diversity (with some limitations5) considered by the Strength through Diversity Project (New Brunswick Health Council, 2022[82]).

Since 2016, the Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (IAB), Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF), Sozio-oekonomische Panel (SOEP) (the Institute for Employment Research, Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, Socio-Economic Panel) conduct the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees in Germany to obtain reliable information on the circumstances faced by people who have sought protection in Germany in recent years. For this purpose, information on refugees’ schooling and vocational training and on their current work situation is collected, among other things (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2022[83]). In many countries, however, refugees are absent from systematic and comprehensive data collections in schools (Siarova and van der Graaf, 2022[84]). Researchers have also noted that data collections focusing on refugees are often not comparable between countries, their methodologies vary and available data is often limited and fragmented (European Union and the United Nations, 2018[85]; Wiseman and Bell, 2021[86]).

Absence of data is a particularly challenging problem for researchers focusing on education outcomes of LGBTQI+ students (McBrien, Rutigliano and Sticca, 2022[17]). Most countries do not systematically collect information on sexual orientation and gender identity, nor include it in regular censuses (OECD, 2019[87]).6 However, some practices around the collection of data on LGBTQI+ students exist. In the United States, the National School Climate Survey provides information on some aspects of student psychological, social and material well-being outcomes with particular focus on LGBTQI+ students. The survey reports on experiences of discrimination, harassment, school climate and resources of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer youth (Kosciw et al., 2020[88]).

Survey non-response presents a major challenge

High non-response rates make analyses of some student groups particularly challenging in sample-based surveys (UNESCO, 2020[15]). Some student groups might be hesitant to disclose sensitive information of their identity for fears of discrimination or persecution. This is particularly challenging for ethnic minorities and Indigenous populations. In the United States, Black or African American alone or in combination, American Indian or Alaska Native alone or in combination, and Hispanic or Latino populations were the most undercounted in the 2020 census (Jensen and Kennel, 2022[89]). Roma populations in Europe and Indigenous populations are also hesitant to self-identify resulting in their underrepresentation in censuses (Csata, Hlatky and Liu, 2020[90]; Jamieson et al., 2021[91]).

Improving response rates is not an easy task, and a range of factors and strategies can be considered. In terms of survey design, it is important to carefully tailor questions to the intended audience and to ensure that is “user-friendly” with an appealing appearance (Smith and Bost, 2007[92]). Survey length is also crucial. While longer surveys generally yield lower response rates, some research shows that the quality of provided answers is not affected (Deutskens et al., 2004[93]; the iConnect consortium, 2011[94]). The way in which answers are collected (by mail, electronically, by phone, in person, etc.) should also be considered in light of the target audience (Smith and Bost, 2007[92]). In the survey administration phase, it is important to clearly explain who will be able to view individual responses (in order to alleviate participants’ potential concerns relating to confidentiality) and how the data will be used and how it can help communities (ibid.). For instance, as a strategy to improve response rates for Indigenous students, some schools in Nova Scotia (Canada) focused on building awareness among parents and students regarding how the information collected in the particular surveys/data collections would be used to determine how to more effectively support Indigenous students such as through the allocation of Indigenous student support workers and recommendations targeted scholarship opportunities (OECD, 2017[95]).

Alter-identification is also a strategy that can be used where, due to the risk of stigma or discrimination (among other reasons), individuals may be reluctant to self-identify as having a particular background or belonging to a particular group. Alter-identification is where a third party estimates the size of a particular group and/or their participation in specific projects and programmes (European Social Fund Learning Network, 2018[96]). For instance, the Slovak Republic collects data on Roma communities by asking municipality representatives to estimate the share of Roma population under their jurisdiction (Ministry of Interior of the Slovak Republic, 2022[97]).

International surveys and international benchmarking

Surveys administered by international or non-governmental organisations can be useful in filling some of the gaps that exist in national data collections. For instance, OECD countries take part in PISA, where results are disaggregated by gender, immigrant and socio-economic background, to the extent sample sizes allow for it. The individual national versions of international questionnaires accompanying international large-scale assessments can also be complemented with specific items. For example, some countries complemented the PISA 2018 student questionnaire with questions about students’ ethnic/Indigenous background or gender identity (OECD, n.d.[98]). To protect individuals’ privacy rights, these data are neither made publicly available nor are reported in PISA international reports. They can be useful, however, in national analyses and monitoring frameworks.

Obtaining internationally comparable data is an issue for the concept of special education needs. While data collections on students with SEN are common (Figure 6.3), definitions among countries vary (Chapter 1). One of the consequences is that there is a large variance in the shares of students with SEN, from 1% in Sweden to 21% in Scotland (United Kingdom) (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2022[99]). Definitional issues are also present in the concept of giftedness. Chile, the Flemish Community of Belgium, Iceland, Ireland, Scotland (United Kingdom) and Spain use the terms “ability”, “high cognitive skills”, “exceptionally able” and combinations or variations of these to describe giftedness (OECD, 2022[16]). Korea, Türkiye and the United States used the word “talent” or its variations (ibid.). The French Community of Belgium, Italy and Norway defined gifted students in terms of their high potential (ibid.).

One of the few sources of international (though not necessarily internationally comparable) data on SEN is the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, which publishes information on the number of students with an “official decision of SEN” by the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) level as well as gender in 31 European member countries (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2022[99]). In addition, the agency provides contextual country background notes. These include the basic definitions of “special education needs”, educational assessment procedures, legal background and other information (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2022[99]).

Information on LGBTQI+ individuals can be compiled by international non-governmental organisations. For example, at the European level, the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex Youth & Student Organisation compiles a regular report on LGBTQI+ inclusive education systems based on data collected from national civil society organisations (Box 6.5).

Box 6.5. The LGBTQI Inclusive Education Index

Based on questionnaires submitted by civil society organisations that focus on the rights of sexual minorities and gender identity issues, The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex Youth & Student Organisation created ten indicators that aim to capture the extent to which governments have implemented laws and policies that foster the inclusion of all learners in the education system.

The indicators are developed around ten areas. Within each area, several factors are “graded” usually on a scale 0 to 10 (with some going to negative values indicating a high degree of discrimination). The areas are as follows:

Anti-discrimination law applicable to education: this focuses on anti-propaganda laws that might ban the display of sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression, or variations in sex characteristics within educational settings. It also covers anti-discrimination legislation and the extent to which it covers sexual orientation, gender identity and expression and variations in sex characteristics;

Policies and action plans: this assesses whether anti-bullying policy or national action plans are in place;

Inclusive national curricula: this determines whether compulsory national curricula are inclusive of LGBTQI+ people;

Mandatory teacher training: this indicates whether sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression, or variations in sex characteristics are mentioned in compulsory teacher training programmes;

Legal gender recognition: this assesses whether gender recognition provisions are in place;

National or regional data collection on bullying and harassment: this determines whether evidence on bullying and harassment based on sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression, or variations in sex characteristics is collected;

Support systems for young people: this focuses on the existence of LGBTQI+ youth services and groups, as well as support and guidance from school staff;

Information and guidelines: this asks whether policies prohibit the presence of LGBTQI+-related information;

School environment and inclusion: this focuses on hostility or inclusiveness of extra-curricular activities available to LGBTQI+ students. It assesses whether LGBTQI+ students were excluded from extra-curricular activities or whether the establishment of LGBTQI+ student groups was prohibited;

International commitments: this assesses whether the country is a member of the European Governmental LGBTI Focal Points Network and has signed the UNESCO Call for Action by Ministers on Inclusive and Equitable Education for All learners.

Source: IGLYO (2022[39]), LGBTQI inclusive education report, https://www.education-index.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/IGLYO-LGBTQI-Inclusive-Education-Report-2022-v3.pdf (accessed 23 May 2022).

The lack of recognition of some ethnic groups (e.g., Roma) as official minorities, combined with colour‑blind approaches, results in scarce international data collections on ethnicity (Rutigliano, 2020[100]). Moreover, administrative categorisation of “ethnicity” often differs. Some countries refer to “ethnic minority groups” or “minority ethnic groups” others base their definitions on nationality. In the latter case, ethnicity as a concept is then often unrecognised in official statistics and policy making (Rutigliano, 2020[100]). For some ethnic groups, such as Roma, there is a substantial heterogeneity in the definition and terminology of “Roma population”, making international data collections inherently more challenging (ibid.). In regard to Roma populations, evidence is often based on international surveys, such as those conducted by the European Agency for Fundamental Rights. The 2016 European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey collected a wide range of information on education, health, housing, labour market participation, discrimination and living conditions of the Roma population. Within education, they specifically focused on participation, segregation and educational attainment (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2018[101]).

Specific reviews on equity and inclusion

External evaluations in the areas of equity and inclusion can also come from school evaluation bodies, such as school inspectorates and independent institutions under the ministries of education. These reports often use evidence gathered from school inspection visits, data from administrative sources (e.g., national assessments) as well as international large-scale assessments. In Denmark, the Danmarks Evalueringsinstitut (Danish Evaluation Institute) is an independent institution the aim of which is to undertake systematic and mandatory evaluations of teaching and learning at all levels of the education system from pre-school to postgraduate level (The Standing International Conference of Inspectorates, 2021[102]). At the primary level, one of the themes they focus on is “inclusive learning environments” and several reports were published on this topic. One project includes a collection of experiences on the development of inclusive learning environments. More detailed reports by the Institute focused on the co‑operation between teachers and special education teachers, and the process of collaborative teaching methods7 (Danish Evaluation Institute, 2020[103]). Other reviews covered the inclusion of newly arrived students in the country into mainstream classes along with a detailed description of six selected municipalities and a specific review on teaching students with dyslexia (Danish Evaluation Institute, 2019[104]; Danish Evaluation Institute, 2020[105]).

In 2022, the Lithuanian Nacionalinė švietimo agentūra (National Education Agency) undertook a review of inclusion in and through education, analysing factors such as the representation of students with SEN in education above lower secondary level, the extent to which teachers are prepared to meet the diverse needs of students through continuous professional learning, and the participation of students with an immigrant and refugee background at various levels of education (National Education Agency, 2022[106]). The review also covered psychological well-being and labour market outcomes of young Lithuanians, as well as geographic disparities in education quality.