This chapter provides an overview of the rationale and objectives of the FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit and explains how governments and other stakeholders can use it. It discusses key policy principles on FDI Qualities, drawn from the substantive chapters that provide detailed policy guidance on improving the impacts of FDI on sustainable development, particularly in the area of productivity and innovation, job quality and skills, gender equality, and decarbonisation.

FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit

1. Overview and key principles

Abstract

1.1. Rationale and objectives

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and fulfilling the commitments made in the Paris Agreement on climate change requires an acceleration in finance and investment. When the SDGs where adopted in 2015, UNCTAD estimated an annual SDG funding gap of USD 2.5 trillion in developing countries (UNCTAD, 2014[1]). According to the OECD Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2021, this gap could have increased by 70% due to the COVID‑19 pandemic in 2020, including due to a drop in foreign private finance (OECD, 2020[2]). Together with public and other private investments, foreign direct investment (FDI) is an important source of finance for inclusive and sustainable development.

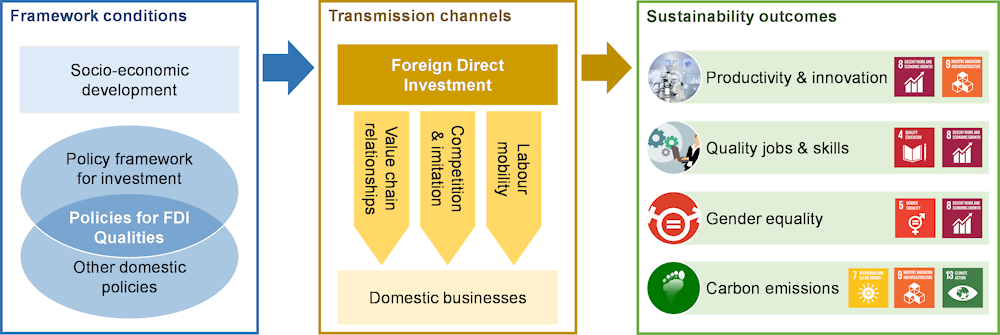

Beyond the quantities of FDI, its qualities also matter, as shown by the OECD FDI Qualities Indicators (OECD, 2019[3]): FDI can play a crucial role in making progress toward all of the SDGs, and in particular to advancing decarbonisation, increasing innovation, creating quality jobs, developing human capital, and promoting gender equality. Yet, the effects of FDI are not always positive, and impacts can differ across areas of sustainable development. Some sustainability objectives are mutually reinforcing while others could present trade‑offs. Among countries receiving FDI, some have benefited more than others and, within countries, some segments of the population have been left behind. Efforts to mobilise investment should be aligned with concerns on qualities and impacts of investment, including potential trade‑offs, in making progress toward the SDGs. To realise the potential benefits from investment and minimise negative effects and trade‑offs, policies and institutional arrangements play a critical role (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Conceptual framework: FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit

The FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit, together with the Indicators, aims to support governments in enhancing the impacts of FDI on inclusive and sustainable development.1 It complements the OECD Policy Framework for Investment (PFI) by focusing specifically on international investment and providing governments with detailed guidance on how to influence and improve its qualities, beyond investment climate reform (OECD, 2015[4]). While addressing the investment climate policies covered at length by the PFI, the Policy Toolkit gives more space to the linkages of investment policy with innovation, SME, labour-market, gender and environmental policies that influence the qualities of international investment, as well as trade‑offs that may exist across these policy areas (Figure 1.1). It is thus a natural extension of the PFI. Like the PFI, it is not prescriptive, but provides broad policy directions for improving the impact of FDI on sustainable development, thus allowing for a flexible approach according to a country’s context and stage of development. In this context, it also recognises that national governments have different priorities, resources and options at their disposal to leverage FDI to advance sustainable development.

The Policy Toolkit targets national governments and their implementing agencies, within and beyond the OECD. It has been further vetted by a number of non-governmental stakeholder groups that are part of the FDI Qualities Policy Network,2 who may also find it useful. While directed at governments, the Policy Toolkit can generate added value for the private sector and civil society by providing a reference document for good practices on investment policy making. Businesses, supported by investment promotion agencies (IPAs), and civil society can for instance use it for policy advocacy, highlighting potential opportunities of national and international policy communities with regards to FDI and sustainable development.3 To strengthen the co‑operation between governments and the donor community, the Policy Toolkit also includes a guide for development co‑operation (OECD, 2022, forthcoming[5]).4 It addresses development co‑operation partners and developing country governments, willing to engage with donors, to enhance the impact of FDI in their economies.

1.2. User guide for the Policy Toolkit

The Policy Toolkit is a practical tool that aims to help governments to:

assess the impacts of FDI in four areas of sustainable development based on the SDGs (productivity and innovation; job quality and skills; gender equality; and decarbonisation);

identify opportunities for policy and institutional reforms to enhance such impacts;

strengthen partnerships with the donor community to support efforts to improve the impacts of FDI in developing countries.

The Policy Toolkit outlines a structured process for reviewing policy and institutional frameworks. It can be used for stand-alone reviews (see Box 1.1 for a description of the pilot FDI Qualities Review of Jordan) or in combination with broader assessments of investment climate reforms (e.g. OECD Investment Policy Reviews). The Policy Toolkit can also be used for self-evaluation and reform design by governments as well as for peer reviews in regional or multilateral discussions.

This overview chapter describes and substantiates a set of core policy principles drawn from the substantive chapters that delve into specific areas of sustainable development. These core principles provide overarching guidance to governments on using diagnostic tools to inform policy action that improves the sustainable development impacts of investment. The users of this Policy Toolkit can refer to the substantive chapters for more concrete guidance on policies for improving the impacts of FDI on specific SDG areas. These chapters tailor the core principles to the specific areas of sustainable development (i.e. productivity and innovation, job quality and skills, gender equality; and decarbonisation) and provide guidance on how to assess the impacts of FDI on them. The chapters provide considerations for policy governance, discuss options for the use of concrete policy instruments and provide good practice examples derived from an initial mapping of FDI Qualities policies and institutions in ten OECD and partner countries (Box 1.2). Beyond the principles, each chapter provides detailed questions and indicators that help policy makers reflect on and evaluate, in a structured way, their policy choices influencing FDI impacts on sustainable development.

Box 1.1. FDI Qualities Review of Jordan: Strengthening sustainable investment – a pilot review

The OECD has been working with the Government of, represented by the Jordan Investment Commission (JIC), on measuring the contribution of FDI to sustainable development and identifying policies to increase the positive impacts of FDI (OECD, 2022[6]). This co‑operation between Jordan and the OECD is part of the OECD FDI Qualities Initiative and has contributed to improving the FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit as a hands-on tool for policy analysis and advice. The work has taken place in the context of the EU-OECD Programme on Investment in the Mediterranean, which supports reform efforts to advance sustainable investment in the Middle East and North Africa region.

The assessment provides tailored policy advice to the government on how to strengthen the impact of FDI in each of the four dimensions of sustainable development covered in the FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit. Based on a detailed mapping of policies and institutions, conducted jointly by the OECD and the government, the study examines to what extent public policies support the channels through which FDI affects these sustainability dimensions.

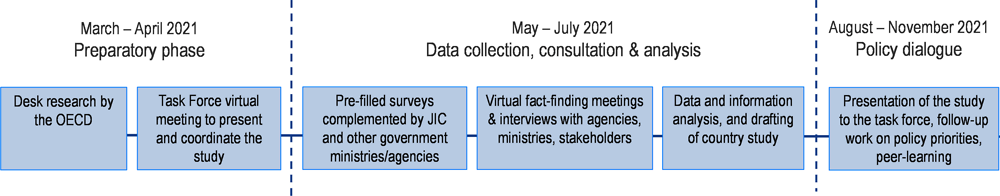

The nine‑month process of this pilot review has involved (i) a preparatory phase, including desk research and setting up an inter-ministerial taskforce, (ii) an analytical phase, including the collection of data, fact-finding, consultations, analysis and drafting, and (iii) a policy dialogue phase during which findings and policy recommendations have been discussed in the taskforce and, with peers, in a special session of the FDI Qualities Policy Network (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Process of the assessment

The taskforce has included more than 20 government agencies and international partners in Jordan that work at the intersection of investment and sustainable development. The taskforce has provided strategic guidance and ensured that the information collected by the OECD, and included in the mapping of policies and institutions, is accurate and complete. The taskforce met early in 2021 to discuss the main objectives of the study and in September 2021 to present the results and to get feedback on policy priorities. The Jordan Investment Commission (JIC) and the OECD have jointly co‑ordinated this taskforce.

Note: A similar pilot assessment was conducted on Portugal over 2020‑22 and the Slovak Republic over 2021‑22, focusing particularly on strengthening FDI and SME linkages to enhance productivity and innovation (OECD, 2022[7]; 2022, forthcoming[8])

Box 1.2. An initial FDI Qualities Policy Mapping of ten OECD and partner countries

The Policy Toolkit provides a novel typology to collect information allowing to assess policies and institutions at the intersection of investment and sustainable development. While using this typology to map policies and institutions is a useful tool for self-assessment, a growing database of countries covered in this mapping will allow for cross-country comparison and provides a compendium of good policy practices on investment and sustainable development, which does not exist at the moment. Applying the typology in an initial mapping of ten OECD and partner countries has informed and helped improve this Policy Toolkit. Selected examples on varying institutional arrangements and policies on investment and sustainable development across these countries are illustrated in this report.

The mapping has involved the collection of data on institutional frameworks and co‑ordination mechanisms across policy domains related to investment and the four areas of sustainable development covered in this Policy Toolkit (productivity and innovation, job quality and skills, gender equality, decarbonisation). Institutions that were mapped include ministries, government departments and implementing agencies responsible for these policy domains. Data on major national policy initiatives at the intersection of investment and sustainable development, designed or implemented by these institutions, are also collected. Specifically, information on policy targeting, beneficiaries of policy initiatives, policy instrument types and design features has been assembled.

The initial FDI Qualities Policy Mapping includes Jordan, Morocco, Indonesia, Thailand, Rwanda, Senegal, Uzbekistan, Costa Rica, Sweden, and Canada. In addition, as part of an OECD-European Commission project on FDI and SMEs, the mapping has been done for all 27 EU Member States, focusing on policies related to FDI impacts on productivity and innovation (OECD, 2021[9]).

1.3. Key policy principles on FDI Qualities

Provide coherent strategic direction on fostering investment in support of sustainable development, and foster policy continuity and effective implementation of such policies

Promote investment-related strategies and plans that are coherent with sustainable development objectives.

Co‑ordinate across ministries to support effective policy implementation and continuity of policy priorities in the area of sustainable investment.

Use public consultations and inclusive decision-making processes involving the private sector and civil society to build consensus on policy reforms on investment and sustainable development.

Seek to assess the impact of major investment projects on sustainable development and of related policies to identify bottlenecks in policy implementation.

Take steps to ensure that domestic policy, legal, and regulatory frameworks support positive impacts of investment on sustainable development

Foster an investment climate based on open, transparent and non-discriminatory investment policies, the rule of law and integrity, the prevention of corruption, the promotion of responsible business conduct, and quality regulation, in line with relevant provisions of the PFI.

Align domestic legal and policy frameworks – including in areas of productivity and innovation, job quality and skills, gender equality, and decarbonisation – with sustainable investment objectives.

Align international investment and trade agreements with sustainable investment objectives, including by ensuring appropriate domestic policy space and social dialogue to achieve these objectives.

Prioritise sustainable development objectives when providing financial and technical support to stimulate investment

Consider whether and to what extent financial and technical support can address market failures hampering sustainable development and thereby help attract sustainable investment and improve the capabilities of firms, job quality and skills of workers.

Take steps to ensure that financial and technical support is transparent and subject to regular reviews.

Facilitate and promote investment for sustainable development opportunities by addressing information failures and administrative barriers

Raise public and stakeholder awareness on impacts of investment on sustainable development.

Improve the link between investment promotion and sustainable development objectives, where relevant, including in the areas of quality infrastructure, research, innovation and skills development, and regional development.

Improve the link between investment facilitation activities and sustainable development objectives, including by taking measures to make procedures for obtaining authorisations and permits transparent and ensure that they are efficiently managed, and by enhancing business linkages between foreign investors and domestic firms.

Promote responsible business conduct and due diligence in operations, supply chains, and other business relationships – in areas such as corporate governance, consumers, labour standards, the environment, human rights, gender equality and the prevention of corruption – including by taking steps to support enterprises to demonstrate their compliance with international standards on sustainable development.

In support of sustainable finance and investing, promote the importance of considering comparable sustainability-related factors in FDI decisions and monitoring.

Strengthen the role of development co‑operation for mobilising FDI and enhancing its positive impact in developing countries

Identify ways that financial and technical assistance, such as blended finance, can support the implementation of the above four recommendations to enhance the impact of FDI on sustainable development.

Promote alignment of donors’ assistance with national priorities related to sustainable investment in accordance with relevant international standards, including through the mapping of such assistance, and the identification of potential support gaps or opportunities to replicate or scale‑up existing assistance.

Increase engagement with the private sector, trade unions and civil society, and promote effective multi-stakeholder partnerships aimed at enhancing the impacts of investment on sustainable development, including increased opportunities for women and youth in particular in relation to equal treatment and skills.

1.3.1. Provide coherent strategic direction on fostering investment in support of sustainable development

Ensure policy coherence and co‑ordination on investment and sustainable development

National strategies and plans on investment, growth, innovation, jobs, skills development, gender equality, decarbonisation and regional development should be as coherent as possible. Just like for investment climate reforms under the PFI, policy coherence to enhance the impacts of FDI requires a whole‑of-government approach. It requires policy responses that do not fit neatly within any single governmental department or agency. Policies and institutions cannot be considered in silos but rather require an adequate and coherent policy mix – including not just investment policies but a variety of policy areas. Cross-ministerial co‑ordination mechanisms, including national and sub-national levels of government, can help guarantee and monitor effective implementation of strategic frameworks and ensure continuity of policy priorities in the area of investment and sustainable development. Weak co‑ordination can increase the risk of duplication, inefficient spending, low-quality service, and contradictory objectives and targets, all of which can undermine investor confidence and, weaken the potential contribution of investment to sustainable development.

The institutional framework that governs policy formulation and implementation differs from country to country. The approach that governments pursue to organise the institutional framework reflects the priority they give to the role of investment for sustainable development. Different governance structures are feasible as long as appropriate reporting mechanisms and communication channels are in place to ensure policy alignment among different institutions and across national and subnational authorities. The more institutions are involved at the intersection of investment and sustainable development policies, the more complex their governance systems become. Complex systems also involve higher risks of information asymmetry, rising transaction costs, trade‑offs and inefficiency. The need for policy co‑ordination and coherence is thus even greater in countries with more complex governance structures, requiring a strong governing body that brings together all policy areas at the intersection of investment and sustainable development. Such a body could be an existing committee, such as one that is governing investment policy and promotion more broadly (OECD, 2022[6]).

Engage in public consultations and inclusive decision-making processes involving the private sector and civil society to build consensus on policy reforms on investment and sustainable development

Public-private consultations and social dialogue can promote collective and innovative solutions to emerging issues that are, at least partly, driven by FDI. These may include digitalisation, automation, artificial intelligence and the future of work. Stakeholder consultations also allow for feedback and build legitimacy and consensus around policy reforms and programmes at the intersection of investment and sustainable development. More open and inclusive policy making processes help to ensure that policies will better match the needs and expectations of citizens, businesses and sub-national regions. Greater participation of stakeholders in policy design and implementation leads to better targeted and more effective policies.

Multinational enterprises (MNEs) can, for example, provide useful insights and information on emerging global trends and give directions on what type of policy approaches would be required in the medium- and long-term. For example, in the area of skills, collecting information on foreign firms’ skills needs will help governments develop adequate policies, such as training programmes, that can prevent skills mismatches and shortages as well as reducing retraining costs. Many countries have put in place systems and tools for assessing and anticipating skills needs, but limited co‑ordination between stakeholders is often a barrier preventing the information from being used further in policy making (Chapter 3).

Assess the impacts of FDI on sustainable development

FDI can have a variety of effects on sustainable development in host countries. These effects are influenced, among other factors, by the characteristics of FDI. They depend for instance on whether the investment involves a new establishment (e.g. new project or a subsidiary) or the acquisition of an existing company, the motivations for the investment (e.g. efficiency-seeking or market-seeking), in which sector and location (metropolitan areas or less developed regions) it takes place, what type of foreign firms are involved (large or SMEs), and what corporate culture and management practices – often determined by policies on responsible business conduct in origin countries – the investment brings with it.

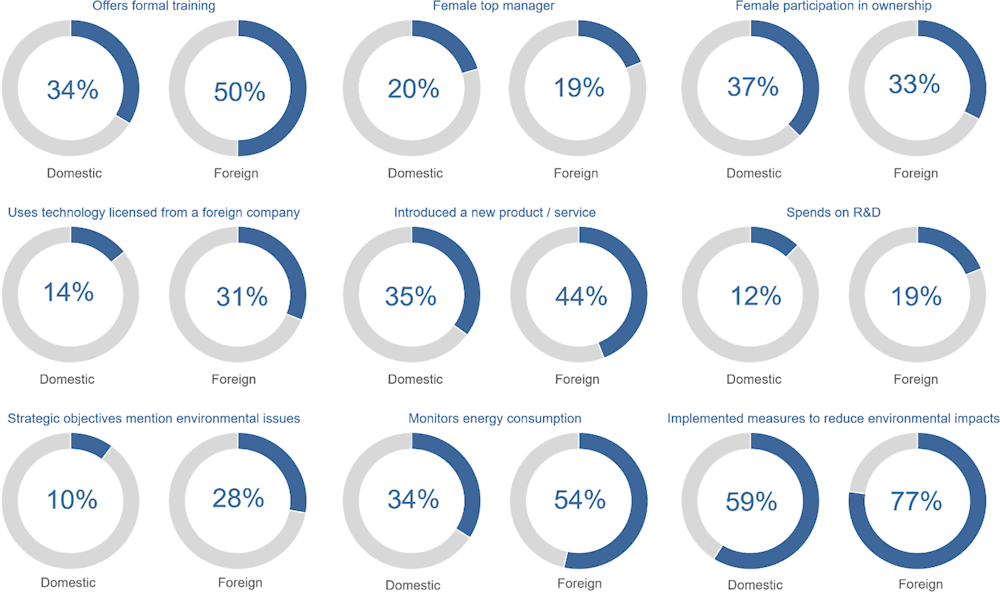

The impacts of FDI involve several transmission channels. Foreign firms directly affect sustainable development through their own operations. The 2022 update of the FDI Qualities Indicators shows, for instance, that foreign firms are more likely to offer formal training opportunities, invest in R&D, and incorporate environmental issues in their strategic objectives (Figure 1.3). Foreign firms’ operations also have spillover effects on domestic businesses arising from value chain relationships between foreign and domestic firms, market interactions through competition and imitation effects, and labour mobility of workers (Figure 1.1, orange box). The premise underlying the existence of FDI spillovers is that foreign firms are often more productive, technologically superior and more skill-intensive and, in turn, benefits might spill over to domestic firms. The direction and magnitude of the combined direct and spillover effects of FDI may vary not only among countries, but also across sustainability outcomes. Framework conditions – such as economic structure and development, domestic firms’ characteristics and skills of the domestic labour force – also determine the extent to which direct and spillover impacts take place.

Governments should routinely examine the characteristics of foreign direct investment and its impact on sustainable development, both through the activities of foreign affiliates and through spillovers on domestic firms. Understanding the impacts of FDI across economic activities and locations is a pre‑condition for identifying weaknesses and strengths of the governance and policy framework. Regularly assessing such impacts should therefore inform policy efforts in that respect. The substantive chapters provide a more detailed overview on how FDI relates to different outcomes and comprise a list of questions and indicators that can guide policy makers in their efforts to better understand FDI impacts and transmission channels. OECD tools, including primarily the FDI Qualities Indicators, and other data tools are described and can be used to address those questions.

The availability of data to assess the impacts of FDI, or specific aspects of these impacts, is not always guaranteed. Therefore, the timely collection of internationally comparable data on investment and business characteristics and practices related to firm size, location, innovation, employment, skills, gender, and the environment can assist governments in assessing the impact of investment on sustainable development. In this context, international and inter-ministerial collaboration can help improve data collection efforts.

Figure 1.3. Sustainable development performance of foreign and domestic businesses

Develop monitoring and evaluation frameworks to improve the effectiveness of policies influencing the impacts of FDI

Comprehensive monitoring and evaluation (M&E) frameworks are important to improve the effectiveness of government efforts to promote sustainable investment through FDI. M&E has received increasing attention as a result of a growing focus on the performance and efficiency of government institutions. The purpose of M&E is to ensure that a policy action progresses according to schedule and achieves planned milestones, and to evaluate the performance of the action against policy objectives. A comprehensive M&E framework for policies related to the impact of FDI is crucial to identify potential bottlenecks in policy design and implementation, and take corrective action when their performance is not in line with expectations. Although many different approaches to M&E exist, some practices are widely adopted, such as the setting up of a dedicated evaluation unit, the use of key performance indicators (KPIs) and qualitative evaluation methodologies (e.g. surveys, benchmarking, consultations), and the establishment of data tracking tools and feedback processes to ensure that relevant and reliable data are available. A comprehensive M&E framework may involve both ex ante and ex post evaluations of policies, including social and environmental impact assessments.

A recent OECD survey finds that three‑quarters of Investment Promotion Agencies (IPAs) view M&E as a key factor that influences their prioritisation strategy. Most IPAs use sustainability-related KPIs such as on productivity and innovation or jobs and about half of the IPAs use metrics related to export and decarbonisation. KPIs such as on job quality or gender equality are rarely used. Yet, KPIs used by IPAs for prioritisation and those for M&E do not always match. For example, no IPA has reported using indicators related to decarbonisation for their M&E although nearly half of IPAs use such indicators to prioritise their activities (OECD, 2021[11]).

1.3.2. Take steps to ensure that domestic policy, legal, and regulatory frameworks support positive impacts of investment on sustainable development

Guarantee open, transparent and non-discriminatory investment policies, the rule of law and integrity, and quality regulation

Open, transparent and non-discriminatory investment policies are key for attracting investment and provide the foundation for an investment climate that is conducive to sustainable development (Box 1.3). The PFI provides guidance in 12 policy areas for investment climate reforms that range from the domestic and international legal framework for investment, competition and taxation to green growth and responsible business conduct (OECD, 2015[4]).

The PFI also highlights the role of strong institutions and good public governance for effective implementation of investment policies, which also applies to policies at the intersection of investment and sustainable development discussed in this Policy Toolkit. The pre‑requisites for strong institutions include respect for the rule of law, quality regulation, transparency and non-discrimination and integrity. Effective action across these dimensions will encourage investment and reduce the costs of doing business. Strong institutions help to maintain a predictable and transparent environment for investors, domestic firms and workers. Policy continuity and effective implementation are further facilitated by an environment of trust. High levels of trust can facilitate compliance with laws and regulations, strengthen confidence of investors and workers and reduce risks aversion.

Box 1.3. Openness to FDI can support sustainable development

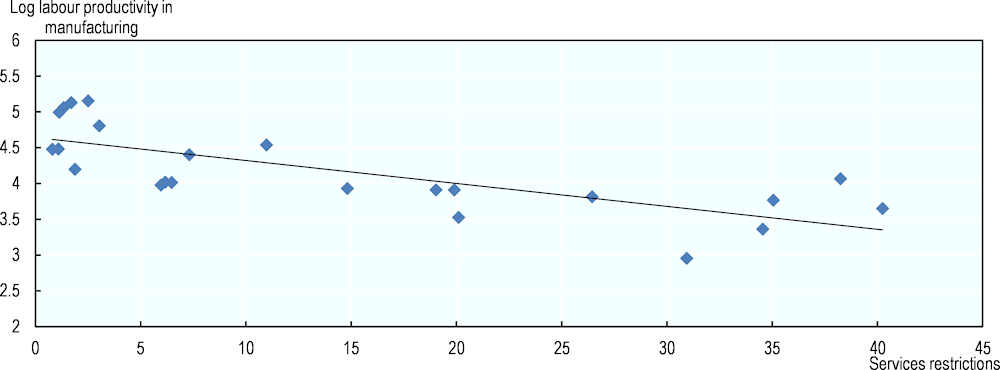

Openness to FDI not only involves higher investment stocks (Mistura and Roulet, 2019[12]), it is also associated with higher productivity in industries that access new markets as well as in downstream sectors that benefit from potentially better access to high quality inputs and services domestically (Chapter 2). Recent OECD research shows that liberalising FDI in services is positively associated with productivity in downstream manufacturing industries, where SMEs are particularly likely to benefit (Figure 1.4.).

More open FDI regimes also affect the labour market, skills and gender equality. Opening sectors to FDI that are skill-intensive is associated with more demand for skills, although, in the short term, opening may also crowd out domestic firms as their skilled workers move to better paid jobs in foreign affiliates, increasing skill-based inequalities. Increased competitive pressure from FDI also affects the need for domestic firms to invest in innovation and skills development to pay higher wages and retain workers, which leads to an overall increase in the supply of skills in the longer term (Chapter 3). Reducing FDI restrictions in sectors that employ relatively more women could, due to increased demand, increase labour market participation of women and their wages. FDI restrictions tend to be highest in services, which often have a relatively high proportion of women (Chapter 4).

Discriminatory restrictions on the establishment and operations of foreign investors can also diminish the potential of FDI on decarbonisation (Chapter 5). Some sectors that present significant opportunities for decarbonisation efforts remain partly off-limits to foreign investors in many countries – notably, transport, electricity generation and distribution, and construction. Many services, typically associated with lower carbon emissions and in some cases crucial for energy-saving technologies (e.g. digital services), are also more frequently restricted to foreign participation (Gaukrodger and Gordon, 2012[13]).

Figure 1.4. FDI openness in services and productivity in downstream manufacturing sectors

Note: Analysis is based on firm-level data from 23 OECD and developing countries; see methodology in OECD (2019). Services restrictions are based on the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index.

Source: OECD (2019[14]), OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Southeast Asia, https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/investment-policy/Southeast-Asia-Investment-Policy-Review-2019.pdf.

Ensure that domestic regulations reinforce possible benefits of FDI on sustainable development

Open and competitive markets are not sufficient to tackle the major societal and environmental challenges that, if not addressed, may jeopardise a prosperous and healthy future for people and the planet. Improving impacts of FDI on sustainable development requires more tailored policy considerations and more focus on policies beyond the PFI, including regulatory frameworks on innovation, skills, the labour market, gender equality and the environment. Aligning these frameworks with objectives related to investment as a tool to support sustainable development is key in this context.

Environmental regulations and reporting requirements are, for example, increasingly being adopted to address the cross-border environmental footprint of multinational enterprises (Chapter 5). The EU Taxonomy Regulation, which entered into law in 2020, for instance, places a reporting obligation on certain companies to disclose how much of their global investment is aligned with environmentally sustainable activities. Starting from 2022, large investors (with over 500 employees) with operations in the EU must disclose which proportion of their turnover, capital expenditure and operating expenditure is associated with environmentally sustainable economic activities.

In the area of job quality, stringent employment protection legislation can increase firms’ labour adjustment costs but also improves job security. Greater flexibility of the host country’s labour market matters for the location choice of foreign investors and affects FDI volumes – and thus potential job creation – as well as their knowledge intensity (Javorcik and Spatareanu, 2005[15]). But job security also protects workers from being fired in response to small fluctuations, which can encourage them to invest in long-term training. Moreover, stricter employment protection can deter or delay labour mobility from domestic to foreign firms while it is typically via this channel that FDI enhances wages in host countries (Hijzen et al., 2013[16]). But it may also protect vulnerable workers that otherwise would have been displaced to lower wage jobs or that would have experienced long-term unemployment. When local production capacities are sufficiently high, more flexible labour markets can host FDI without necessarily reducing employment or increasing wage disparities between foreign and domestic firms (Becker et al., 2020[17]). Labour market policy is most effective when negotiated with trade unions and workers’ representatives (Chapter 3).

The creation of good quality jobs for women by foreign investors requires domestic regulation that ensures decent labour standards on minimum wages, occupational health and safety, employment protection, social protection (e.g. maternity leave), flexible working arrangements, and protection from gender discrimination and sexual harassment in the workplace (Chapter 4). FDI can also support female entrepreneurship by creating business opportunities along the value chains of MNEs or through technology and productivity spillovers. However, regulatory barriers such as non-transparent procedures or restrictions on business registrations, signing contracts or owning bank accounts and land can hinder women’s ability to take advantage of these opportunities (World Bank, 2021[18]).

Endeavour to join major international agreements and conventions that promote sustainable development and foster responsible business conduct

A fundamental condition for FDI to positively influencing sustainable development is that domestic legislation fulfils international standards and principles on sustainability objectives, such as on climate action, job quality and gender equality, or sets national standards that are even more ambitious than the international ones. Endeavouring to join major international agreements and conventions promoting sustainable development is thus important.

In the area of climate action, the Paris Agreement (2015) is the central international effort to combat climate change aiming to limit global mean temperature change to 1.5°C. Progressively more ambitious climate mitigation commitments are expected from all states party to the treaty over the coming decades. As of January 2021, 187 states and the EU, representing about 80% of global greenhouse gas emissions, had ratified or acceded to the Paris Agreement. Carbon emissions have global effects, regardless of where they were released, meaning that the impact of one country’s climate policies is dependent on the climate policies of other countries. The Paris Agreement gives governments, as well as industry and the general public, reassurance of commensurate action from their trade partners (Chapter 5).

International labour standards are essential for ensuring that the global economy, including FDI, provides benefits to all (Chapter 3). The ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (1998) represents the most widely accepted effort to define a set of core labour standards, related to eliminating all forms of forced or compulsory labour, effectively abolishing child labour, eliminating discrimination in respect of employment and occupation, and ensuring the freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining. The Declaration covers eight fundamental conventions and the majority of countries has formally subscribed to some or all them, which has strongly influenced changes in national labour laws. Indeed, many developing countries where poor labour practices in the operations of foreign firms have been a concern tend to have reasonable de jure labour standards, in some cases comparable to those in developed countries. But poor labour practices in the operations of foreign firms, and businesses more generally, reflect weak public enforcement of national and international labour provisions. Non-compliance with international labour provisions by foreign firms and their suppliers continues to be a pressing concern in many countries with weak rule of law (see Principle 2).

Gender equality and non-discrimination based on sex are fundamental rights enshrined in numerous international human rights instruments (Chapter 4). The UN Charter of 1945 is the first international instrument to establish the principle of equality between men and women. Since then, numerous international human rights instruments have promoted women’s rights and contributed to the inclusion of gender equality principles in national legislation, including the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979), the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995), and a number of ILO conventions dealing with gender-specific issues such as the Equal Remuneration Convention, the Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, the Convention on Workers with Family Responsibilities and the Maternity Protection Convention.

Multilateral initiatives such as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles Concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy can help raise awareness about responsible business conduct (RBC), including on labour practices, gender equality and climate action (OECD, 2011[19]). They are non-binding recommendations by adhering governments, supported by employer and worker organisations, which are directly addressed to MNEs. They recommend MNEs, for example, to observe standards of employment no worse than those observed by employers in the host country, or to mitigate the climate impacts of their operations, within the framework of laws, regulations and administrative practices in the countries in which they operate, and in consideration of relevant international agreements, principles, objectives, and standards. They also recommend MNEs to carry out due diligence through their value chain relationships to address existing or potential adverse risks on sustainable development (OECD, 2011[19]).

Align international investment and trade agreements with sustainable development standards and principles

Many countries have concluded investment treaties over the past half century as part of their efforts to foster international investment and, in turn, advance economic development in home and host countries. These treaties take various forms: Since 1959, when the first modern bilateral investment treaty (BIT) was signed, well over 3 000 BITs have been negotiated, of which more than 2 200 are in force today. An ever increasing number of bilateral or multilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) containing provisions on investment cover hundreds of additional bilateral relationships. The focus of these treaties has traditionally been on investment protection. Governments have sought to use investment treaties as instruments to improve legal certainty and reduce unwarranted risk for foreign investors wishing to locate long-term investments abroad. An overarching goal of this approach has been to foster more investment from abroad than may otherwise have been possible in the absence of a treaty, although existing research finds mixed evidence of the impacts of treaties on investment flows (Pohl, 2018[20]).

Only recently have governments begun to consider investment treaties as instruments to influence not only the quantities but also the qualities of international investment in terms of its impacts on sustainable development. While relatively little is known today about the ways that investment treaties influence the impacts of FDI, this is likely to depend crucially on the nature, design, context and interpretation of treaty provisions used for claims and on dispute settlement arrangements. Indeed, the scope of absolute protections and government action with regard to their interpretation are key factors affecting policy space for non-discriminatory regulation. Some recent treaties provide for state‑state dispute settlement (SSDS) rather than investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) for investment protection claims.

Express language addressing social and environmental priorities is also increasingly used in investment agreements, although concrete impact has been difficult to demonstrate. So far, no attempt has been made to assess whether and how investment treaties in general or certain design elements and features in particular influence the qualities of international investment and very little empirical evidence is available that would allow any quantitative statements in this regard. Further research will need to reflect through which mechanisms investment treaties influence the qualities of FDI, which specific treaty provisions are observed in treaties that are tuned towards the qualities of FDI, and what effects these clauses have.

Provisions in these international agreements can be designed to allow treaty parties to make commitments to strengthen domestic law regulation and enforcement in several key areas relating to the qualities of FDI. This could take place for example through provisions that buttress domestic law or its enforcement by including commitments to adopt and enforce key international conventions on labour, the environment or human rights. In addition, provisions could also directly address business conduct by, for example, encouraging observance of RBC standards, requiring compliance with domestic laws or establishing conditions for access to investment treaty benefits (Gaukrodger, 2020[21]).

International investment and trade agreements that are aligned with climate objectives, international labour standards and principles on gender equality and encourage co‑operation and monitoring of commitments will thus provide support to government efforts to enhance the positive impact of investment on sustainable development. Yet, these treaties remain a single policy tool among many for governments seeking to improve the sustainability impacts of international investment. Such treaties should not be seen as a substitute for other international and domestic policies designed for long-term improvements in the investment climate and for advancing sustainable development.

1.3.3. Prioritise sustainable development objectives when providing financial and technical support to stimulate investment

Consider financial and technical support to help build domestic capabilities of firms, entrepreneurs and workers that enhance the impact of FDI on sustainable development

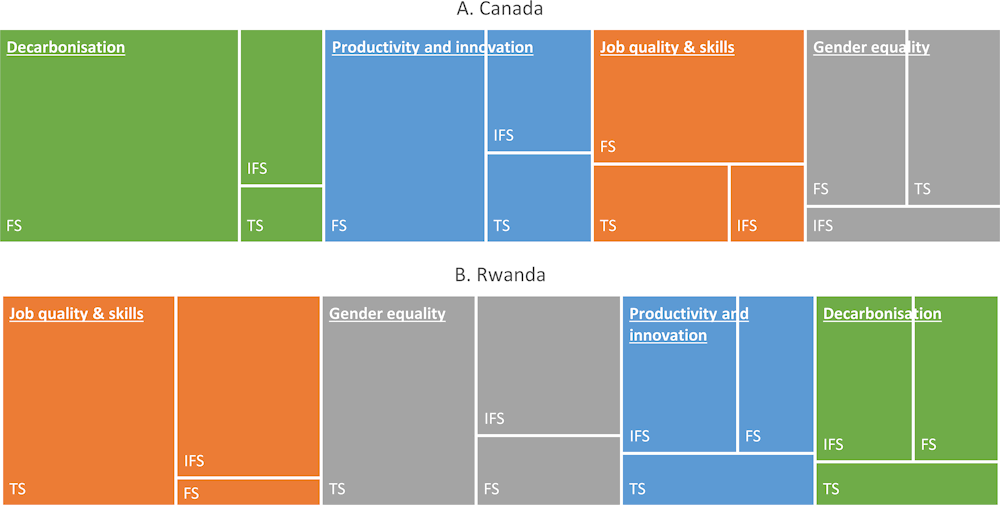

Governments can use financial and technical support measures, as well as information and facilitation services (as discussed in the next section) to foster decarbonisation, productivity and innovation, as well as job quality, skills and gender equality. Depending on the priorities for sustainable development, policy attention and types of policy instruments may vary across areas of the SDGs (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5. Mix of financial and technical support, and information and facilitation services by area of sustainable development

Note: The areas reflect the volume of policy initiatives but do not provide any indication of the relative scope and scale of initiatives (e.g. in terms of budget or number of beneficiaries).

Source: OECD (2022[22]), FDI Qualities mapping: A survey of policies and institutions that can strengthen sustainable investment.

Private investors do not internalise the positive spillovers of low-carbon investments and are likely to under-invest in related technologies and skills compared to socially optimal levels. Targeted financial and technical support by the government is therefore warranted. A wide range of support measures are available to stimulate low-carbon investments and build low-carbon capabilities, and studies have shown the success and cost-effectiveness of the support policy depends crucially on the country context rather than on the specific tool used (Chapter 5). In general, government support for specific low-carbon technologies should decrease over time as related sectors (e.g. renewable energy generation) mature and the costs of the technologies decline. Minimum investment size thresholds for securing financial support can discourage investment by smaller foreign and domestic enterprises, despite their high innovation potential and may be counterproductive. Providing investment incentives to both green and non-green substitutes (e.g. renewable and non-renewable energy) also limits the overall effectiveness measures to stimulate low-carbon investments and reduce the environmental footprint of FDI (OECD, 2021[23]).

Financial support may be used to strengthen production capacities of local firms, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that enhance the impact of FDI on sustainable development (Chapter 2). Direct lending and grants can be provided to SMEs to help them invest in R&D, acquire new technology, adopt digital and low-carbon solutions, and engage in innovation and internationalisation activities. Various tax relief measures can also be granted to support subgroups of the SME population such as innovative firms and start-ups to expand their business and join global value chains. Supplier development programmes are increasingly part of government support to improve the production capacity of local SMEs and help them become partners and suppliers of foreign firms. These programmes usually assess the need for upgrading SME capabilities in various aspects of their performance and provide coaching and training in quality control, management strategy, financial planning, as well as product certification and foreign market standards. Government agencies may also organise seminars and courses for SMEs, and provide a range of business diagnostic tools to help them assess their innovation and technological capabilities.

Training and skills development programmes raise the skills level of workers and help reduce skills mismatches and shortages that can be amplified by FDI entry or expansion (Chapter 3). Skills upgrading can further enable domestic firms to benefit from potential FDI spillovers (Becker et al., 2020[17]). Albeit costly, training programmes offered by government agencies have shown some success when well-designed and well-targeted (Bown and Freund, 2019[24]). For instance, sectoral training or re‑training programmes in transferable certifiable skills have been found to facilitate labour mobility and help workers move to better-paid jobs (Autor et al., 2020[25]). These programmes could be particularly beneficial for women and other vulnerable workers affected by rapidly changing labour markets and the evolving needs of MNEs. Pre‑employment training programmes can also help host countries quickly respond to the needs of potential new foreign investors. On-the‑job training programmes delivered by investors are found to contribute to a more flexible workforce and, ultimately, to higher wages; governments can partner with the private sector in skill development by supporting companies that train their workers. (Almeida and Faria, 2014[26]). Providing all firms with financial support to run such programmes is, however, not always a cost-effective solution, and other policy aspects, such as product market reforms to increase competition should be considered as a complement.

Financial and technical support can also be used to promote gender equality goals (Chapter 4). Tax incentives can be given to companies that encourage the hiring or training of women, or that provide services such as childcare. Similarly, subsidies and grants can be given to companies to help offset the higher costs companies may face in hiring, promoting and training women. Currently, the use of incentives to promote gender inclusive practices in the workplace remains limited (Kronfol, Nichols and ThuTran, 2019[27]). Due to various economic, social and cultural barriers, female entrepreneurs tend to have fewer entrepreneurial and managerial skills and have more difficulty accessing formal credit than male entrepreneurs (Union, 2019[28]). The 2013 OECD Council Recommendation on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship encourages countries to design policy instruments to help female entrepreneurs overcome barriers related to lack of skills and credit. Financial support can take the form of soft loans or microcredit, or tax benefits (OECD, 2017[29]). Technical support can help women entrepreneurs strengthen their skills and grow their business, including to internationalise their operations. This can include training programmes to develop skills in business, management and digitisation, professional advice on legal and tax issues and other business development services.

Ensure that financial support to stimulate investment addresses market failures and is transparent and subject to regular reviews

Governments often use financial support, such as investment tax incentives or subsidised loans and grants, to attract investors and promote investment in specific activities, sectors and locations. Financial support for investors is sometimes conditional on specific criteria related to sustainable development and has thus the potential to advance sustainable development. A new OECD Investment Tax Incentives Database, currently covering 36 developing countries, shows that about a quarter of all tax incentive schemes promote at least one area of sustainable development and 28 of the 36 countries use such tax incentives (Celani, Dressler and Wermelinger, 2022[30]). About half of the countries use tax incentives to promote exports; a third of the countries use tax incentives with specific eligibility conditions and design features to create employment and improve job quality. Other areas – including those associated with skills development, improving environmental outcomes, local supply linkages, and gender equality – are less frequently observed.

The net benefits of these policies are not well understood (Dayan et al., 2021[31]). Further analysis is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of financial support to advance sustainable development. Costs, including impacts on tax revenue for example and the potential to spur rent-seeking behaviour, may outweigh their gains. Transparency about the benefits available to investors is often incomplete; this complicates the assessment of whether the policies in place address market failures, achieve their goals, and at what costs.

The benefits of transparency are recognised among tax and investment policy communities. Under the OECD Declaration on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises, adhering countries agree to “endeavour to make such measures [investment incentives] as transparent as possible, so that their importance and purpose can be ascertained and that information on them can be readily available” (OECD, 2011[32]). The OECD’s Task Force on Tax and Development has also identified the need for a more effective global transparency framework for tax incentives for investment (OECD, 2013[33]), and transparency is listed as an essential element of good governance in the IMF-OECD-UN-World Bank report to the G‑20 Development Working Group on improving use of tax incentives in low income countries (IMF-OECD-UN-World Bank, 2015[34]). Fostering transparency of investment incentives is also an important objective for many countries in ongoing negotiations on investment facilitation at the WTO.

Improving transparency of investment incentives is a first step to better understanding their effectiveness and efficiency. This is particularly important in the context of the COVID‑19 recovery, where many governments consider implementing new incentives to attract investors or reducing existing ones due to growing fiscal constraints. In addition to supporting policy evaluation, increasing transparency and awareness of available benefits, eligibility criteria, and awarding processes could also help countries attract untapped investment sources. For example, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) have fewer resources to navigate the often complex legal framework governing incentives (and less power to negotiate agreements directly with governments). But all investors would benefit from access to clear and regularly updated information to assess new investment opportunities. Combined with good governance, greater transparency around investment incentives can support co‑ordination across different agencies involved in granting incentives, and strengthen confidence that incentives are granted in a fair and not overly discretionary manner. Greater transparency on investment incentives could also help foster trust and co‑operation across countries. This is timely in light of the recent global minimum tax agreement by 137 countries and jurisdictions in the context of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS), which may affect how governments use investment incentives in the future.

In addition to the need for transparency, financial and technical support should be time‑limited and subject to regular review. Net benefits of support programmes are context-specific and may change over time. Monitoring and re‑evaluation of financial and other support is often neglected. Government authorities should regularly prepare tax expenditure reports to measure and monitor the costs of tax incentives (OECD, 2015[4]; IMF-OECD-UN-World Bank, 2015[34]). The government should also periodically carry out audits to ensure that financial and technical support measures are not abused. Financial and technical support measures should be reviewed periodically to assess their effectiveness in helping meet desired goals.

Sunset clauses provide opportunities for periodic evaluation, for example to improve efficiency of the incentive, alignment with the intended policy objective and help in identifying and winding down incentives that are no longer needed. Sunset clauses are provisions in a law or regulation stating that sections of it cease to have effect after a specific date, unless further legislative action is taken to extend them. Well-designed and implemented sunset clauses create a natural break that strengthens a firm’s incentive to accelerate investment immediately and avoids extensive revenue losses to the government. On the other hand, sunset clauses also introduce an element of uncertainty to investors and increase the complexity of the legal system.

1.3.4. Facilitate and promote investment for sustainable development opportunities by addressing information failures and administrative barriers

Raise stakeholder awareness on impacts of FDI on sustainable development

Assessing investor performance and impacts on sustainable development is not only essential for governments to identify possible policy responses but also to raise awareness among stakeholders and the general public about the impacts of their consumption and investment choices. Governments can use assessments on the impacts of FDI to inform the general public and engage with stakeholders, resulting in a better informed and more inclusive policy debate.

Concerns about access to information on the carbon footprint of consumption and investment choices have led many governments to introduce measures to raise public awareness and understanding of carbon performance, including platforms for dialogue and information sharing, information campaigns, and product labelling schemes. For instance, many governments long ago introduced mandatory energy labelling schemes for appliances, which have been key in helping consumers choose more energy-efficient products. While there are still no regulatory requirements on carbon labelling, some investor-driven initiatives are emerging to cater to customers that are responsive to climate credentials (Chapter 5).

Social and cultural norms in FDI recipient countries can also shape the extent to which countries can leverage FDI for sustainable development. For example, in the area of gender equality, women in host countries may not be able to benefit from the job opportunities generated by foreign investors due to various social and cultural barriers (Chapter 4). Gender stereotypes are at the root of patterns of gender inequality in the labour market, e.g. the fact that women tend to be concentrated in low-value‑added sectors and in part-time jobs. Public information and awareness-raising campaigns can help change traditional norms that harm investment impacts on sustainable development.

Link investment promotion and aftercare activities to sustainable development objectives

IPAs are key players in bridging information gaps that may otherwise hinder the realisation of foreign investments, and their potential sustainable development impacts. Their primary role is to create awareness of existing investment opportunities, attract investors, and facilitate their establishment and expansion in the economy, including by linking them to potential local partners. The tools used by IPAs vary widely, ranging from intelligence gathering (e.g. market studies) and sector specific events (inward and outward missions) to pro‑active investor engagement (one‑to‑one meetings, email/ phone campaigns, enquiry handling).

Most IPAs prioritise certain types of investments over others, by selecting priority sectors, countries or investment projects, and allocating resources accordingly (OECD, 2018[35]). The approaches and tools adopted by IPAs increasingly aim to attract investment that supports national sustainable development priorities. A recent OECD survey shows that sustainable development considerations are important for IPAs when setting their prioritisation strategy (OECD, 2021[11]): 90% of IPAs in the OECD use productivity and innovation performance indicators to prioritise investment attraction, and 87% use indicators linked to job creation and skills. About half use low-carbon transition-related indicators.

IPAs also play an important role in keeping their economies attractive and competitive, notably through their policy advocacy role. Working at the intersection of business and public service, IPAs are in a unique position to channel the feedback received from investors to policy makers and advocate for open, transparent and well-regulated markets. With the continued policy uncertainty following the COVID‑19 pandemic, IPA’s policy advocacy role has become ever more important and is likely to be reinforced in the future.

While IPAs prioritise and attract new investments to fulfil their sustainability goals, they are also providing aftercare services to existing investors to support their operations and facilitate their expansions or reinvestments. Many IPAs provide matchmaking services and organise business-to-business meetings where representatives of foreign and domestic firms are introduced to each other. Many IPAs also organise demonstration and networking events that include knowledge exchange and information sharing. The policy goal is to bring down information barriers and allow foreign firms to identify local suppliers for future collaboration (Chapter 2). Some of these matchmaking programmes specifically target women entrepreneurs to help them connect with foreign investors (Chapter 4). Through these aftercare activities, IPAs should also consider promoting responsible business conduct and encouraging them to more systematically comply with laws, such as those on the respect for human rights, environmental protection, labour relations and financial accountability, as well as to embrace sustainable practices in their business operations.

Streamline procedures for obtaining permits needed for investors to engage in business activities that foster sustainable development

Regulatory burdens and complicated procedures for obtaining permits can dissuade foreign firms from investing when faced with more welcoming environments elsewhere. They can hamper the growth of smaller businesses and their move towards high value added, knowledge‑based and low carbon production, which would allow them to establish business linkages with foreign investors too. It is therefore important that regulatory procedures (such as to start a business and to deal with construction permits, environmental licensing, getting electricity, paying taxes, and enforcing contracts) are streamlined, easily accessible and consistent with investment licensing procedures. Having a single window portal for all administrative procedures can help reduce transaction costs for investors, as long as it does not create additional duplication and complexity in the company establishment process.

Less regulation is not always better, however, and may ignore the potential economic, social and environmental benefits of regulation (Thomsen, 2019[36]). An investment and business climate is a complex organism and requires a holistic approach to reform, such as that provided by the PFI. Regulatory reforms should therefore be informed by regulatory impact assessments, including environmental and social impact assessments.

Promote corporate disclosure and fostering interoperability, comparability, and quality of core ESG metrics in reporting frameworks, ratings, and investment practices

Sustainable finance is generally referred to as the process of considering environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors when making investment decisions, leading to increased longer-term investments into sustainable economic activities and projects (Boffo and Patalano, 2020[37]). ESG disclosure is gaining in acceptance because it can provide a useful tool for corporate investors to assess and communicate their socially responsible practices, and for financial investors that seek to assess the potential for social returns in a consistent manner across companies and over time.

Despite substantial efforts to improve ESG disclosure frameworks in recent years, the reporting of ESG factors still suffers from considerable shortcomings with respect to consistency, comparability and quality that undermine its usefulness to investors. Some industry participants have noted that a lack of consistent disclosure frameworks at the international level hinders comparability. While progress is being made by framework developers and providers, there is still no universally accepted global set of principles and guidelines for consistent and meaningful ESG reporting (Boffo and Patalano, 2020[37]).

Better corporate disclosure of climate‑related risks will also help aligning the environmental pillar of ESG investment ratings with a low-carbon transition (Chapter 5). Inconsistencies in the construction of ESG ratings across providers, the multitude of different metrics, and insufficient quality of forward looking metrics prevent agencies from supplying consistent and comparable information on transition risks and opportunities across firms and jurisdictions. Notably, rating providers appear to place less weight on negative environmental impacts while placing greater weight on the disclosure of climate‑related corporate policies and targets, with limited assessment as to the quality or impact of such strategies. Such limitations could mislead investors with an aim to align portfolios with the low-carbon transition. Greater transparency and precision of climate‑related corporate risks along the Task Force on Climate‑Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations, for example, would facilitate investments into lower carbon assets (OECD, 2021[38]).

1.3.5. Strengthen the role of development co‑operation for mobilising FDI and enhancing its positive impact in developing countries

Strengthen co‑operation between governments and the donor community to enhance the impact of FDI on sustainable development

Donors devote a significant portion of their resources to supporting the private sector, including to support improvements to the investment climate, enhance productive capacities and develop physical infrastructure. Over the period 2013‑19, total private‑related support through official development finance reached USD 755 billion in disbursements, representing 45% of total official development finance (OECD, 2021[23]). While donors have traditionally focused on incentivising FDI in developing countries, further consideration to the qualitative dimensions of investment can make donors’ interventions more effective and foster greater impact of investment on the SDGs.

Greater co‑operation between governments and the donor community can help more systematically integrate the qualitative aspects of investment into donors’ activities, and support governments’ efforts to enhance the positive impact of investment on sustainable development. Governments and the donor community should work together to identify financial and technical assistance solutions to support policy reforms and implementation, promote alignment with international standards, reduce exposure to financial and sustainability risks, and provide support to the private sector through financial and other instruments, as well as support for business strategies. The forthcoming FDI Qualities Guide for Development Co-operation explores different modalities for leveraging development co‑operation to enhance the sustainability impact of FDI, and can serve as a framework for donors and developing country governments willing to co‑operate in this agenda.

Ensure alignment of donors’ interventions with national priorities

In order to ensure the effectiveness of donors’ interventions, it is essential to ensure alignment of such interventions with national priorities on investment and sustainable development in recipient countries. Various international instruments aiming to strengthen aid effectiveness, including the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005), Nairobi Outcome Document (2016), and Kampala Principles on Effective Private Sector Engagement in Development Co‑operation (2019) reflect a growing recognition that development efforts need to be led by the countries receiving development support (OECD, 2019[39]).

Development co‑operation actors and partner countries may consider various modalities to mobilise and enhance the positive effects of FDI, including through support to governments to improve the investment climate, or direct engagement with the private sector to influence the behaviour of foreign investors. The nature and type of relevant interventions may vary depending on the areas of sustainability covered by the FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit that donors and partner countries wish to target.

Identifying and mapping existing donors’ interventions can help assess alignment with national priorities on investment and sustainable development, and inform development co‑operation strategies. Such a mapping can also help identify potential gaps in the breadth of modalities used and areas of the SDGs targeted, support greater co‑ordination of donors interventions, and help identify opportunities to replicate or scale‑up relevant interventions.

Engage with the private sector and civil society

The private sector and civil society are key actors and stakeholders of development co‑operation efforts to promote investment and sustainable development. Engaging with both the private sector and civil society is therefore essential to inform, implement and monitor development co‑operation programmes and projects aimed at mobilising FDI and enhancing its impacts on sustainable development.

Results from a review of 919 private sector engagement projects carried out by the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co‑operation (GPEDC) found that only 9% of reviewed projects listed civil society as partners, and even fewer listed business associations (5%) or trade unions (0%). The Kampala Principles on Effective Private Sector Engagement in Development Co‑operation, developed by the GPEDC, emphasise the importance of establishing more inclusive partnerships to foster trust through inclusive dialogue and consultation in projects that aim to engage the private sector for development results (GPEDC, 2019[40]).

Donors and governments in developing countries have an opportunity to involve the private sector and promote multi-stakeholder partnerships through interventions directly targeting businesses. Such interventions may include financial participation in sustainable private investment projects, support for responsible business conduct standards (e.g. the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and associated due diligence guidance) and multi-stakeholder partnerships that include voluntary, collaborative arrangements between various actors with the aim to work towards a sustainability goal. More broadly, across and throughout interventions targeting the investment climate and spill-over effects, donors and recipient country governments can make development co‑operation efforts more effective by consulting and involving various actors and stakeholders, including policy makers, the private sector, civil society and trade unions at all stages of programmes and project cycles.

References

[26] Almeida, R. and M. Faria (2014), “The wage returns to on-the-job training: evidence from matched employer-employee data”, IZA Journal of Labor & Development, Vol. 3(1), 1-33.

[25] Autor, D. et al. (2020), “The fall of the labor share and the rise of superstar firms”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 135(2), 645-709.

[17] Becker, B. et al. (2020), “FDI in hot labour markets: The implications of the war for talent”, Journal of International Business Policy, Vol. 3, 107-133.

[37] Boffo, R. and R. Patalano (2020), ESG Investing: Practices, Progress and Challenges, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-Investing-Practices-Progress-Challenges.pdf.

[24] Bown, C. and C. Freund (2019), “Active labor market policies: lessons from other countries for the United States”, Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper, Vol. (19-2).

[30] Celani, A., L. Dressler and M. Wermelinger (2022), Building an investment tax incentives database: Methodology and initial findings for 36 developing countries, OECD Publishing.

[31] Dayan, S. et al. (2021), Improving transparency of investment incentives: Draft discussion note.

[21] Gaukrodger, D. (2020), Business Responsibilities and Investment Treaties, public consultation paper by the OECD Secretariat, https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/investment-policy/Consultation-Paper-on-business-responsibilities-and-investment-treaties.pdf.

[13] Gaukrodger, D. and K. Gordon (2012), Investor-State Dispute Settlement: A Scoping Paper for the Investment Policy Community, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5k46b1r85j6f-en.

[40] GPEDC (2019), Kampala Principles on Effective Private Sector Engagement in Development Co-operation.

[16] Hijzen, A. et al. (2013), “Foreign-owned firms around the world: A comparative analysis of wages and employment at the micro-level”, European Economic Review, Vol. 60, 170-188, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2013.02.001.

[34] IMF-OECD-UN-World Bank (2015), Options for Low Income Countries’ Effective and Efficient Use of Tax Incentives for Investment, A report prepared for the G-20 Development Working Group by the IMF, OECD, UN and World Bank, https://www.oecd.org/tax/options-for-low-income-countries-effective-and-efficient-use-of-tax-incentives-for-investment.htm.

[15] Javorcik, B. and M. Spatareanu (2005), “Do foreign investors care about labor market regulations?”, Review of World Economics, Vol. 141(3), 375-403.

[27] Kronfol, H., A. Nichols and T. ThuTran (2019), “Women at Work. How Can Investment Incentives Be Used to Enhance Economic Opportunities for Women?”, Policy Research Working Paper 8935, The World Bank Group.

[12] Mistura, F. and C. Roulet (2019), The Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment: Do Statutory Restrictions Matter?, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/641507ce-en.

[10] OECD (2022), FDI Qualities Indicators: 2022.

[22] OECD (2022), FDI Qualities mapping: A survey of policies and institutions that can strengthen sustainable investment.

[6] OECD (2022), FDI Qualities Review of Jordan: Strengthening sustainable investment,, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/736c77d2-en.

[7] OECD (2022), Strengthening FDI and SME linkages in Portugal, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d718823d-en.

[41] OECD (2021), Council Report on the Implementation of the OECD Recommnedation on the Policy Framework for Investment, Note by the Secretary-General.

[9] OECD (2021), Enabling FDI diffusion channels to boost SME productivity and innovation in EU countries and regions: Towards a Policy Toolkit.

[38] OECD (2021), ESG Investing and Climate Transition: Market Practices, Issues and Policy Considerations, https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-investing-and-climate-transition-market-practices-issues-and-policy-considerations.pdf.

[23] OECD (2021), OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Thailand, OECD Investment Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c4eeee1c-en.

[11] OECD (2021), Together or separate: Investment Promotion Agencies’ prioritisation and monitoring and evaluation for sustainable investment promotion across the OECD countries.

[2] OECD (2020), Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2021: A New Way to Invest for People and Planet, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e3c30a9a-en.

[3] OECD (2019), FDI Qualities Indicators: Measuring the sustainable development impacts of investment, http://www.oecd.org/fr/investissement/fdi-qualities-indicators.htm.

[39] OECD (2019), Making Development Co-operation More Effective. 2019 Progress Report., OECD, https://doi.org/10.1787/26f2638f-en.

[14] OECD (2019), OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Southeast Asia, https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/investment-policy/Southeast-Asia-Investment-Policy-Review-2019.pdf.

[35] OECD (2018), Mapping of Investment Promotion Agencies in OECD Countries, https://www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/mapping-of-investment-promotion-agencies-in-OECD-countries.pdf.

[29] OECD (2017), 2013 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264279391-en.

[4] OECD (2015), Policy Framework for Investment, 2015 Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264208667-en.

[33] OECD (2013), Principles to Enhance the Transparency and Governance of Tax Incentives for Investment in Developing Countries, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-global/transparency-and-governance-principles.pdf.

[32] OECD (2011), Declaration on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises, 2011 Edition,, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0144.

[19] OECD (2011), OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, 2011 Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264115415-en.

[5] OECD (2022, forthcoming), Draft FDI Qualities Guide for Development Co-operation.

[8] OECD (2022, forthcoming), Strengthening FDI and SME linkages in the Slovak Republic, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[20] Pohl, J. (2018), Societal benefits and costs of International Investment Agreements: A critical review of aspects and available empirical evidence, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e5f85c3d-en.

[36] Thomsen, S. (2019), How much difference do the Doing Business indicators make?, https://oecdonthelevel.com/2019/01/15/how-much-difference-do-the-doing-business-indicators-make/.

[1] UNCTAD (2014), World Investment Report 2014, UNCTAD, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2014_en.pdf.

[28] Union, O. (2019), The Missing Entrepreneurs 2019: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship, https://doi.org/10.1787/3ed84801-en.

[18] World Bank (2021), Women, Business and the Law, https://wbl.worldbank.org/en/wbl.

Notes

← 1. The OECD Council invited the Investment Committee (IC) to “develop and promote the FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit, which could possibly be welcomed by Ministers at the 2022 Ministerial Council Meeting as a tool to complement and support the use of the PFI, thereby further aligning the PFI with the SDG Agenda” (OECD, 2021[41]).

← 2. The OECD has established a dedicated multi-stakeholder policy network to support and provide guidance to the FDI Qualities initiative, through policy dialogue and technical discussions on project activities. The network includes government officials from OECD and partner countries; development co‑operation practitioners; private sector and civil society; international organisations and academia; and experts from policy communities across the OECD.

← 3. The Policy Toolkit does not have dedicated recommendations to businesses, but it calls extensively on governments to adhere to, and implement, the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises (OECD, 2011[19]). The Guidelines provide recommendations, agreed by adhering governments, on responsible business conduct, i.e. how businesses can avoid harm to people and the planet and improve positive contributions to society. Under the FDI Qualities initiative, the role of businesses, including the identification of good business practices, could be further developed.

← 4. The OECD Council further invited the IC to “reinforce co‑operation and alignment with development partners, particularly in the development of the FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit” (OECD, 2021[41]).