This chapter presents a Policy Toolkit to help governments attract foreign direct investment (FDI) that contributes to decarbonisation, both by reducing the emissions associated with foreign investments and inducing low-carbon spillovers to domestic firms. The chapter describes the channels through which FDI affects carbon emissions and the contextual factors determining the magnitude and direction of such impacts. The objective of the Policy Toolkit is to provide an overview of the policy choices that can improve the impacts of FDI on decarbonisation.

FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit

5. Policies for improving FDI impacts on carbon emissions

Abstract

Main policy principles

1. Provide strategic direction and promote policy coherence and co‑ordination on investment and climate action

Ensure a coherent, long-term strategic framework to mainstream decarbonisation across economic sectors that is linked to the national vision or goals for growth and development, with clear climate goals (e.g. emissions reductions, renewable energy) that are translated to science‑based targets for the private sector.

Develop a dedicated strategy that articulates the government’s vision on the contribution of investment, including foreign direct investment, to decarbonisation. The strategy sets the goals, identifies priority policy actions and clarifies responsibilities of institutions and co‑ordinating bodies.

Strengthen co‑ordination both at strategic and implementing levels by establishing appropriate co‑ordinating bodies or by considering to expand the mandate and composition of existing ones, such as boards of investment promotion agencies and higher councils for green growth.

Encourage public consultations and stakeholder engagement to receive feedback and build consensus around policy reforms and programmes to decarbonise investments.

Design and implement effective monitoring and evaluation frameworks to assess the impact of FDI and related policies on decarbonisation, and to identify bottlenecks in policy implementation, including strategic environmental assessment (SEA) and environmental impact assessment (EIA) systems. Build capacity at national and subnational levels to review environmental assessments, reduce delays in the process, and improve transparency and information systems supporting the review process.

2. Ensure that domestic and international investment regulations are aligned with and reinforce national climate objectives, including commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Endeavour to join major international agreements and conventions promoting decarbonisation and set domestic environmental standards for investments (e.g. on emissions, fuel economy, appliances) that are aligned with climate objectives and that support climate‑friendly business conduct.

Ensure that international investment and trade agreements are aligned with climate objectives and allow for sufficient domestic policy space to achieve these objectives.

Develop laws and regulations that level the playing field for climate‑friendly investment, including by ensuring an open and non-discriminatory environment for foreign investors in low-carbon technologies, strengthening competition in electricity markets, and ensuring intellectual property protection for low-carbon innovations.

3. Stimulate investment and build technical capabilities related to low-carbon technologies, services and infrastructure

Phase out subsidies for investments that distort price signals and reduce the competitiveness of low-carbon technologies and consider introducing carbon pricing measures. Address any adverse effects on jobs with appropriate measures to compensate and retrain workers so as to ensure a just transition.

Ensure that financial support to stimulate low-carbon investment addresses market failures that reduce the competitiveness of low-carbon investments, and is transparent, time‑limited and subjective to regular reviews.

Use financial and technical support to build domestic low-carbon capabilities, and to support the flow of knowledge and technology from foreign to domestic firms.

4. Address information failures and administrative barriers that reduce the competitiveness of low-carbon investments

Raise public awareness on climate priorities and individual actions for investors and consumers to reduce carbon footprint.

Encourage corporate disclosure of carbon emissions embodied in products and services (e.g. carbon labelling), and facilitate reporting of suspected violations of environmental regulations, or risks of violations, related to their business operations.

Tailor investment promotion activities and tools raise visibility of low-carbon investment opportunities. Facilitate compliance with environmental permitting. Support foreign investors in identifying domestic suppliers and partners with complementary capabilities. Use IPAs as intermediaries to make policy makers aware of the regulatory needs of low-carbon investors.

5.1. The urgency of reducing CO2 emissions

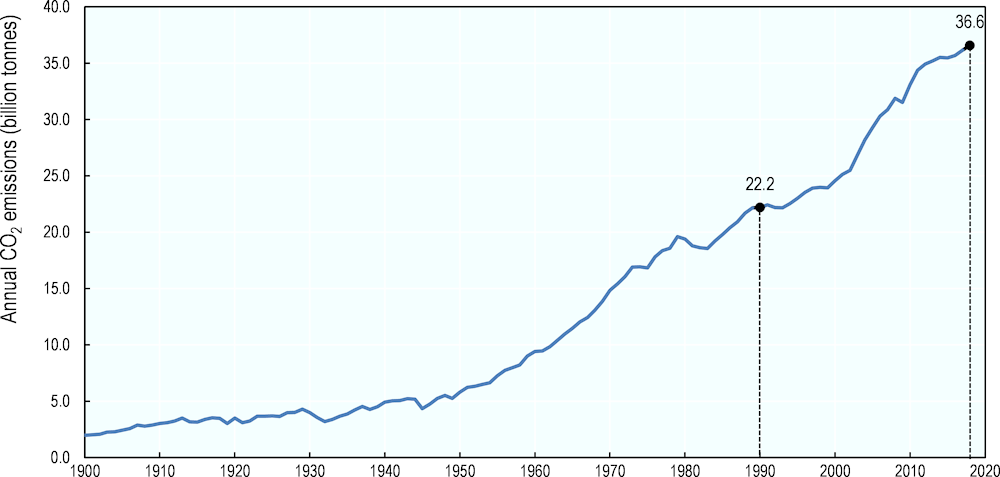

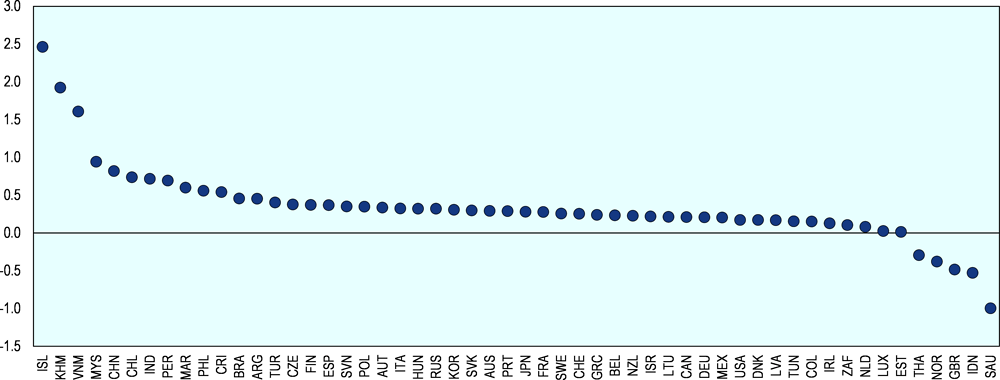

Adverse environmental developments are among the gravest global threats of current times. A global economy reliant on fossil fuels and the resulting rising greenhouse gas emissions, now 60% higher than their 1990 level (Figure 5.1), are creating drastic changes to the climate, including more frequent and extreme weather events, land degradation, ocean acidification, and biodiversity loss. Climate change and the resulting migration pressures and threats to food and health security are at the forefront of global efforts to sustain the planet (WEF, 2020[1]). To address these mounting challenges, on 12 December 2015, 190 countries signed the Paris Agreement to combat climate change, pledging to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 (UNFCCC, 2015[2]). This landmark agreement was discussed at the 26st Conference of the Parties (COP26) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) with new impetus and more ambitious pledges to accelerate actions and investments needed for a sustainable low-carbon future.

Figure 5.1. Global annual CO2 emissions

Source: International Energy Agency’s World Energy Statistics.

The climate crisis has serious financial repercussions, including disaster-related damage costs that amount to hundreds of billions of dollars, annually (IPCC, 2018[3]); adaptation costs associated with protection and reinforcement; and mitigation costs associated with decarbonisation. Climate change mitigation and adaptation will require an estimated USD 7 trillion per year worth of public and private investments alone to meet global infrastructure development needs and climate objectives through 2030 (OECD, 2017[4]). Of these, USD 4 trillion per year are needed across emerging economies, and USD 1.7 trillion per year in emerging Asia (OECD, 2020[5]). In the wake of the COVID‑19 pandemic, government efforts to support economic recovery are essential but should not undermine actions to limit the climate crisis. Stimulus measures and policy responses must be aligned with ambitions on climate change, biodiversity and wider environmental protection (OECD, 2020[6]; OECD, 2020[7]). The window of opportunity for climate action is closing fast and short-term economic measures will have a significant impact on the ability to meet global goals (United Nations, 2015[8]).This chapter focuses on the potential contribution of FDI to climate change mitigation.1 Box 5.1 provides some definitions and clarifications for the following discussion.

Box 5.1. Key terms and concepts

CO2 emissions: Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the primary greenhouse gas (GHG) responsible for global warming. This Policy Toolkit focuses primarily on CO2 because it is generated by all economic activities, but its implications can be extended to cover other GHGs. The GHG Protocol jointly developed by the World Resources Institute and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development uses a delineation that has become standard, dividing emissions into three types:

Scope 1: Direct emissions generated by industrial processes and any other on-site activities.

Scope 2: Indirect emissions associated with energy (i.e. electricity, heat or steam) imported from off-site.

Scope 3: All other indirect emissions in the life cycle of the products produced, including those associated with any intermediate goods, transport of goods to market, emissions in end use and disposal of products produced. It includes also emissions associated with leased assets, franchises and investments.

Carbon intensity: the emission rate of CO2 of a specific economic activity. A common measure used to compare emissions from different sources of electrical power is carbon intensity per kilowatt-hour.

Low-carbon technology: a technology that helps reduce CO2 emissions by (1) reducing energy use (e.g. energy-saving); (2) reducing or eliminating carbon emissions from production or use (e.g. renewable energy, hydrogen); (3) removing carbon from the atmosphere (e.g. carbon capture); or (4) conserving resources (e.g. recycling). The Policy Toolkit focuses primarily on the first two classes of technologies but can be applied to all four.

Renewable energy: energy from sources that are naturally replenishing. It generally is considered to include six renewable‑power generation sectors: geothermal, marine/tidal, small hydroelectric, solar, wind, and the combined sector biomass and waste. Clean energy and renewable energy are used interchangeably for the purpose of this report.

Source: OECD (2020[9]), Climate Policy Leadership in an Interconnected World: What Role for Border Carbon Adjustments?, https://doi.org/10.1787/8008e7f4-en; OECD (2019[10]), FDI Qualities Indicators: Measuring the sustainable development impacts of investment, www.oecd.org/fr/investissement/fdi-qualities-indicators.htm; Ang, Röttgers and Burli (2017[11]), The empirics of enabling investment and innovation in renewable energy, https://doi.org/10.1787/67d221b8-en; WRI/WBCSD (2004[12]), The Greenhouse Gas Protocol, https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/ghg-protocol-revised.pdf.

5.2. The impact of FDI on carbon emissions

Evidence stemming from the traditional literature on the trade‑FDI-environment nexus proposes that FDI affects the host country’s carbon footprint in contending ways by expanding the scale of economic activity, changing the structural composition of economic activity and delivering new techniques of production (Grossman and Kruger, 1991[13]; Copeland and Taylor, 1994[14]; Porter and van der Linde, 1995[15]). In isolation, the scale effect is expected to increase carbon emissions, since an increase in the size of an economy implies more production and, in turn, more emissions. The technique effect, which refers to a change in production methods resulting from FDI inflows and the transfer of technology from foreign to domestic firms, is expected to reduce emissions by helping diffuse less emitting technologies (Pazienza, 2015[16]). The composition effect is associated with a change in industrial structure driven by FDI, and its impact on emissions will depend on the production specialisation of a country. An FDI-driven shift toward services would for instance be associated with a reduction in emissions, while a shift toward heavy manufacturing would deteriorate the host country’s carbon footprint.

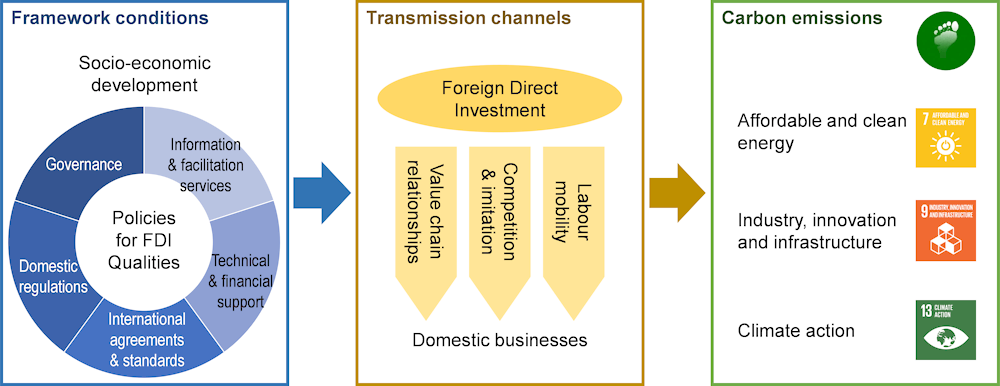

These various effects underpin the channels through which FDI influences carbon emissions (Figure 5.2, yellow box). Specifically, FDI generates emissions from production processes, energy use, product end use and product disposal that reflect investor characteristics (e.g. sector, technology, and motive). The supply chain relationships that foreign investors forge affect the emissions embodied in the intermediate goods they use, and the emissions generated from the distribution of goods to market. Market interaction with local firms can influence the emissions of domestic business through competition and imitation effects. Similarly, mobility of workers from foreign to domestic firms can influence the business practices and resulting emissions-intensity of domestic firms.

Figure 5.2. Conceptual framework: FDI impacts on carbon emissions

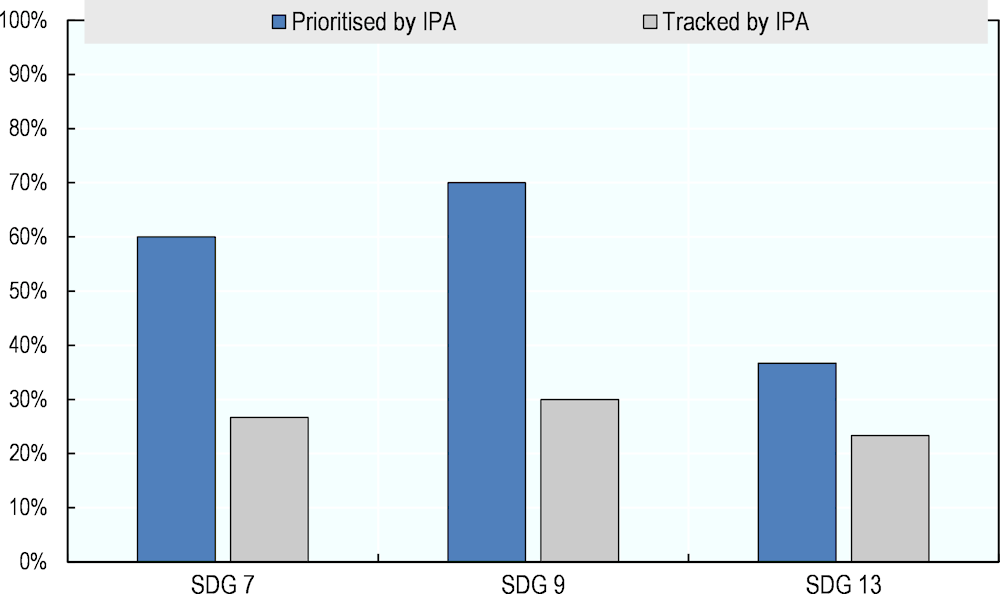

The motivation behind this Policy Toolkit is that, under certain circumstances, FDI can contribute the needed financial and technological resources to advance the low-carbon transition. Developing countries that face greater constraints both in mobilising finance and acquiring and disseminating technologies may draw particular benefits from FDI in their efforts to tackle climate change. Resulting benefits for host countries include (Figure 5.2, green box):

improving energy security, diversifying energy sources, reducing reliance on energy imports and electrifying remote rural areas (SDG7);

fostering innovation, creating new industries and jobs, and gaining an edge over competitors and attendant export opportunities in key industries (SDG9);

and the localised benefits of mitigating climate change, reducing environmental degradation, and improving air quality and associated health impacts (SDG13).

The manner in which FDI affects carbon emissions and the extent to which it can contribute to decarbonisation depend on a number of contextual factors that are the focus of this chapter, including FDI characteristics and spillover potential, socio‑economic factors, and the policy environments of home and host countries. Targeted policy interventions can level the playing field for more climate‑friendly FDI, and influence spillovers to domestic firms. The next section will look closely at framework conditions and policies that affect the impact of FDI on emissions (Figure 5.2, blue box).

5.2.1. FDI characteristics and impacts on carbon emissions

The carbon intensity of foreign investments depends on a range of characteristics specific to investors, including the technologies they use, the energy they consume, the products and services they offer, their motives for investing internationally, and their corporate cultures and environmental policies. Annex Table 5.A.1 provides the core questions of the Policy Toolkit for governments to self-assess the impacts of FDI on decarbonisation, including through spillovers.

Low-carbon technologies

Low-carbon technologies, by definition, reduce the CO2 emissions associated with economic activity in any sector and are therefore key attributes that determine the carbon intensity of FDI. Broadly speaking, low-carbon technologies reduce CO2 emissions by (1) reducing energy use (e.g. energy-saving); (2) reducing or eliminating carbon emissions from production or use (e.g. renewable energy, hydrogen); (3) removing carbon from the atmosphere (e.g. carbon capture); or (4) conserving resources (e.g. recycling).

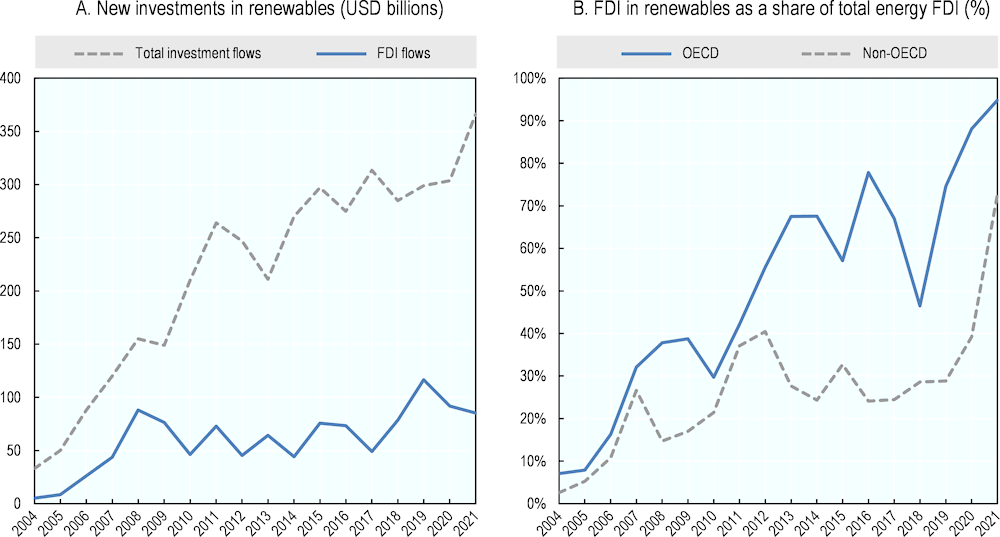

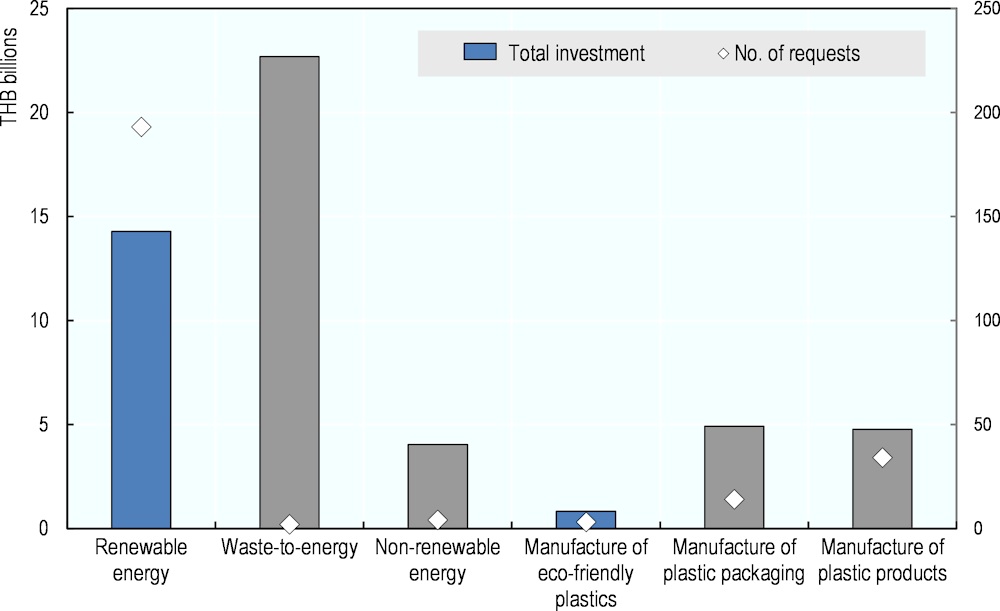

The energy sector, one of the largest contributors to CO2 emissions, is a noteworthy example in which FDI can deliver innovations in energy generation, storage, and distribution (e.g. smart grids). Large‑scale diffusion of these technologies is particularly important as it reduces the indirect emissions of all electricity-consuming activities. In fact, electrifying other sectors is an important avenue for decarbonisation provided that electricity generation itself is decarbonised. Thanks to their financial and technical advantages, multinational enterprises (MNEs) are key players in the deployment of capital- and R&D-intensive clean energy technologies across borders, accounting for 30% of global new investments in renewable energy (Figure 5.3, Panel A). FDI in the energy sector has also shifted considerably away from fossil fuels and into renewables, particularly in advanced countries, but increasingly also in developing countries (Figure 5.3, Panel B). The contribution of FDI to the energy transition may become increasingly relevant in developing countries, where demand for energy is expected to grow most rapidly in the coming decades.

In the industrial sector, decarbonising production processes requires switching to lower-carbon fuels for production and making more efficient use of materials. According to some studies, 20% of the energy consumed in industry is electricity, while it is already technologically possible to electrify up to half of the industrial fuel consumption (McKinsey, 2020[17]). In the transport sector, new low-carbon vehicles are being developed for road transport, rail, waterborne transport and aviation, including vehicles that run on electricity, hydrogen fuel cells, and compressed or liquefied natural gas. In the construction sector, advanced building materials and energy-efficient home appliances are being developed and existing technologies improved. As multinationals are key players in these emissions-intensive activities, they can make an important contribution to furthering electrification or developing altogether new breakthrough technologies for emissions reductions (e.g. hydrogen fuel cell, carbon capture utilisation and storage), as well as integrating climate action into their risk management processes, business models and supply chains.

Figure 5.3. Renewables as a share of total FDI in the energy sector

Source: OECD elaboration based on Financial Times (2022[18]), FDI Markets: the in-depth crossborder investment monitor from the Financial Times, https://www.fdimarkets.com/; and BloombergNEF (2022[19]), Energy Transition Investment Trends 2022, https://about.bnef.com/energy-transition-investment/.

Investor attributes

FDI motives are among the factors that push firms to invest abroad in low-carbon technologies, or alternatively to transfer high-carbon production to foreign locations. Foreign markets offer opportunities to sell new low-carbon products and services designed in relatively small or saturated home jurisdictions. Scarcity of production factors (e.g. labour), natural resources (e.g. wind power) or strategic assets (e.g. infrastructure) in home countries may also drive MNEs to seek cross-border opportunities for their low-carbon investments, while accumulated technical knowhow related to low-carbon technologies in home countries can give investors a competitive edge internationally.

Investor entry modes also have implications on the carbon intensity of FDI activities. Mergers and acquisitions entail changes in corporate ownership, structure and governance, which in turn can affect the environmental policies and implications of existing establishments in host countries, for better or worse. Yet, greenfield investments involve new economic activity or expansions of existing activities and will typically result in greater (positive or negative) impacts on host countries. From a climate perspective, the direction of the impact will depend on the carbon intensity of the new investments and the technologies they generate and deploy.

Home country consumer and shareholder expectations and pressures from civil society can further contribute to green branding strategies and drive MNEs to reconsider their foreign operations and supply chains, strengthen environmental reporting or adopt carbon labelling. These considerations are consistent with the ‘Pollution Halo’ hypothesis, whereby, MNEs apply a universal environmental standard across borders and, in so doing, tend to spread their greener technology to their affiliates in host countries (Porter and van der Linde, 1995[15]).

5.2.2. FDI spillovers on carbon emissions

The premise behind FDI spillovers is that multinational firms have access to innovative technologies and operating procedures, which, if applied, could help raise environmental performance overall and induce the broader uptake of low-carbon technologies. The realisation of these spillovers hinges on the transfer of knowledge from foreign to domestic firms, through their market interactions and through the mobility of workers. The spillover potential varies across technology and spillover channels. FDI spillovers on carbon emissions are likely to be negative, if, for instance, foreign investors are attracted by weaker environmental regulation (i.e. the pollution haven hypothesis) and they induce a race to the bottom with respect to environmental standards.

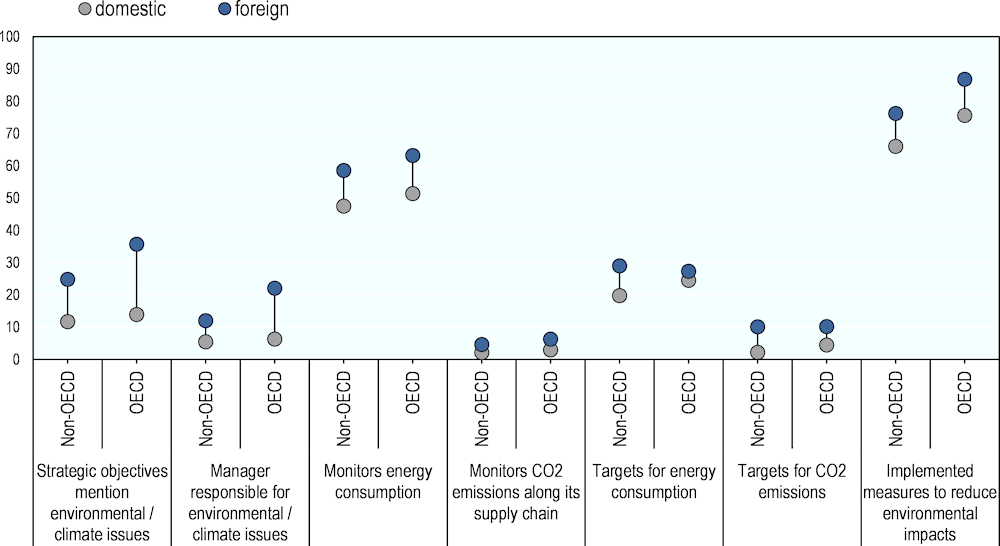

The OECD FDI Qualities Indicators, developed using the green economy module of the EBRD-EIB-World Bank Enterprise Surveys, suggest that foreign manufacturing companies outperform domestic peers in terms of green business practices, and indeed have the potential to contribute to greening the business practices of domestic businesses. This potential may be especially large in developing countries. According to the surveys, a minority of firms incorporate environmental or climate change issues into their strategic objectives (11‑36%), and even fewer employ a manager responsible for environmental issues (5‑22%). More substantial shares of companies monitor energy consumption (48‑63%) and introduce measures to save energy (34‑51%), and over 60% of companies seek measures to control pollution, while still very few companies specifically monitor or seek to reduce carbon emissions (2‑6%). In general, companies in OECD countries tend to outperform companies in non-OECD countries, and foreign firms perform at least as well as domestic firms across all environmental dimensions (Figure 5.4). The gap between foreign and domestic firms is often wider in non-OECD countries than in OECD countries, particularly when it comes to addressing carbon emissions.

Figure 5.4. Green performance of foreign and domestic firms

Note: The OECD and non-OECD averages are based on a subset of countries from Europe, Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia.

Source: OECD based on EBRD-EIB-WB (2022[20]), World Bank Enterprise Surveys, https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/enterprisesurveys.

Value chain spillovers

The supply chain decisions of foreign investors influence the emissions embodied in the intermediates they use in production; similarly, their choices of distributors will influence the emissions associated with the delivery of goods to market. In practice, there is evidence that very few firms monitor carbon emissions along their supply chains, even though the practice is more common among foreign firms, suggesting that these emissions are rarely internalised by investors (Figure 5.4). At the same time, the bulk of MNE impacts on emissions originates from their supply chains in many industries. For instance, in the garment industry the supply chains of global leaders in the garment industry account for 70% of emissions in the sector (McKinsey-GFA, 2020[21]). Encouraging foreign investors to engage with sustainable suppliers and partners, both locally and in their foreign operations, can further support emissions reductions objectives.

Moreover, advancing the low-carbon transition and maximising its contribution to employment generation depends on countries’ abilities to build and strengthen domestic supply chains (IRENA, 2013[22]). Linkages with local suppliers and buyers are an important channel of knowledge and technology diffusion. In the context of the low-carbon agenda, these types of spillovers can take many forms, ranging from increased compliance with environmental regulations to innovations in energy use and industrial processes. Broadly speaking, these spillovers are more likely to occur in manufacturing industries and services sectors, as the opportunities for local linkages are greater than in the energy, building and transport sectors. A key requirement for these spillovers to materialise is that local businesses have sufficient absorptive capacity to meet the demands of foreign investors. This means that the realisation of FDI’s low-carbon spillovers through value chain linkages requires a parallel evolution of skills and shifts in the labour force, which also helps ensure a just transition (OECD, 2015[23]).

In addition to supplier and buyer linkages, a key conduit for FDI’s low-carbon spillovers is through local partnerships, strategic alliances and joint ventures. This may be the most important transmission channel of R&D-intensive investments in the development and commercialisation of breakthrough technologies, where research collaborations across a number of private and public sector actors are common.

Other spillover effects

The entry and establishment of foreign investors heightens the level of competitive pressure on domestic companies, inducing them to innovate or imitate in order to keep up and remain competitive. As noted previously, foreign multinationals may be particularly successful in catering to end users that are responsive to environmental performance and green branding. As companies compete to serve growing consumer demands for low-carbon products and services, foreign competition can catalyse low-carbon innovation across domestic businesses in their efforts to retain customers or tap into new markets. Thanks to these competitive pressures, low-carbon technologies and operating procedures can disseminate to the wider business sector and make a significant contribution to reducing its environmental and carbon footprint.

A special case in which monopolistic markets can inhibit decarbonisation is the energy sector, traditionally dominated by incumbent utilities that control power generation, transmission and distribution, and have little incentive to diversify energy sources. Unbundling the power sector by separating power generation, transmission and distribution functions can help create more space for foreign investment in renewable power, which in turn can exert competitive pressures toward conventional power generators, and spur the wider diffusion of renewable power investments across domestic actors.

Movement of workers between foreign and domestic firms and corporate spin-offs originating from foreign MNEs can further propagate knowledge spillovers from foreign to domestic firms. The low-carbon transition creates many new jobs related to low-carbon technologies (IRENA-ILO, 2021[24]). Foreign MNEs play an important role as employers in developing skills related to these new technologies and in creating a capable low-carbon workforce (Chapter 3). As such, labour mobility is a key conduit for the diffusion of these skills and low-carbon operating procedures more broadly to domestic companies. Labour mobility also allows new foreign entrants to seek out talent and hire the skilled workers needed to run their businesses, and can therefore contribute to additional low-carbon FDI attraction.

5.2.3. Socio‑economic determinants of FDI’s carbon impacts

The level of socio‑economic development determines a country’s production specialisation, industrial structure, positioning in global value chains, and the sophistication of its infrastructure and technology. Some theories conjecture an inverted-U relationship between output growth and the level of emissions (known as the ‘Environmental Kuznets Curve’), expected to increase as a country develops and the economy grows, but begin to decrease as rising incomes pass a turning point and create demands for tougher environmental regulation, bringing forth cleaner techniques of production (Grossman and Kruger, 1991[13]). According to these theories, differences in comparative advantage of advanced and developing countries result in differing FDI profiles, with developing countries attracting relatively more polluting investments in heavy manufacturing and extraction activities, and advanced economies attracting less polluting investments in services and high-tech manufacturing. Though exceptions exist, empirical studies are consistent with this hypothesis, as they find evidence of positive FDI effects on emissions more frequently in low- and middle‑income countries than in high-income countries (Hoffman et al., 2005[25]; Pao and Tsai, 2010[26]; Behera and Dash, 2017[27]).

The OECD FDI Qualities Indicators also suggest that differences in the carbon intensity of FDI can be explained in part by differences in comparative advantages. According to the indicators, only resource‑rich countries, where fossil fuels constitute a large share of GDP, tend to attract carbon-intensive FDI (Figure 5.5). This is likely because extraction and energy transformation offer lucrative investment opportunities for large multinationals with the requisite capacity for these heavily capital- and energy-intensive activities.

Figure 5.5. FDI and CO2 emissions

Note: See OECD (2019[10]) for explanatory details.

Source: Update of OECD (2019[10]), FDI Qualities Indicators: Measuring the sustainable development impacts of investment, www.oecd.org/fr/investissement/fdi-qualities-indicators.htm.

Locational pull factors specific to low-carbon investments are related to the characteristics of FDI discussed above, and in particular to investor motives. Countries with underdeveloped electricity grids outside of urban centres offer viable untapped markets for producers of small-scale low-carbon electricity alternatives, compared to those with more extensive and dependable grids. Consumers that are aware of and responsive to green credentials such as carbon labels provide attractive markets for producers of low-carbon consumer goods. Countries that enjoy an abundancy of wind, sun or tidal bays are the most profitable destinations for investments in wind turbines, solar plants, and tidal generators. Industry and technology clusters appeal to producers of low-carbon equipment seeking to gain from agglomeration effects, and other strategic assets such as skills or technologies similarly attract investors seeking to acquire knowledge and technical capabilities (UN, n.d.[28]; Hanni et al., 2011[29]).

5.3. Policies that influence FDI impacts on carbon emissions

The host country’s policy framework influences its business environment, including the FDI entering the country and its carbon implications (Figure 5.2, blue box). A policy framework for low-carbon investment is in many respects comparable to an enabling environment that is conducive to investment in general. Policies conducive to FDI, however, will not automatically result in a substantial increase in low-carbon FDI. A policy framework for investment is thus a necessary but insufficient condition for low-carbon investment. Policy makers will also need to improve specific enabling conditions for low-carbon investment by developing policies and regulations that systematically internalise the cost carbon emissions, and facilitate low-carbon FDI and its knowledge and technology spillovers (OECD, 2015[30]).

This Policy Toolkit aims to provide a comprehensive policy framework for countries to maximise positive impacts of FDI on carbon footprint while mitigating adverse effects, in line with the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. It builds on Chapter 12 on “Investment framework for green growth” of the OECD Policy Framework for Investment, and on the OECD Policy Guidance for Investment in Clean Energy Infrastructure, and complements these instruments by offering a comprehensive mapping of policies and institutional settings that influence FDI’s carbon impacts across selected advanced and developing countries (see Chapter 1). The Toolkit is structured around four broad principles and the policy instruments that support these principles (Table 5.1). Annex Table 5.A.2 provides the core questions of the Policy Toolkit for governments to self-assess policies that influences the impacts of FDI on decarbonisation.

Table 5.1. Overview of FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit for reducing FDI impact on carbon emissions

|

Principle 1: Provide strategic direction and promote policy co‑ordination and coherence on investment and climate action |

Governance |

National strategies and plans |

|

Oversight and co‑ordination bodies |

||

|

Public consultation, data, M&E |

||

|

Principle 2: Ensure that domestic and international investment regulations and standards reinforce climate objectives |

International agreements & standards |

International agreements on climate change |

|

International agreements on RBC |

||

|

Environmental provisions BITs & RTAs |

||

|

Domestic regulations |

Legal framework for investment |

|

|

Environmental standards & requirements |

||

|

Regulatory incentives |

||

|

Principles 3: Stimulate investment and build technical capabilities related to low-carbon technologies, services and infrastructure |

Financial support |

Carbon pricing instruments |

|

Subsidies and tax relief for green investments |

||

|

Public procurement of green investments |

||

|

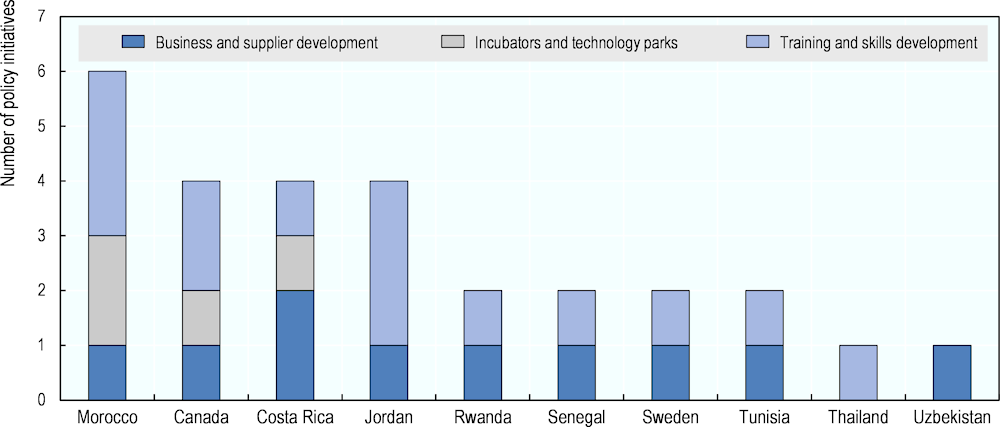

Technical Support |

Business & supplier development services |

|

|

Green technology parks |

||

|

Training and skills development services |

||

|

Principle 4: Address information failures and administrative barriers to level the playing field for low-carbon investors |

Information & facilitation services |

Green investment promotion & facilitation |

|

Public awareness campaigns |

||

|

Corporate environmental disclosure |

5.3.1. Provide strategic direction and promote policy coherence on investment and climate

Ensure coherence across climate, sectoral and investment strategies and plans

Strong government commitment to combat climate change and to support low-carbon growth, underpinned by a coherent policy framework and clear decarbonisation targets, provides investors with encouraging signals regarding the government’s climate ambitions. Setting a clear, long-term transition trajectory that is linked to the national vision or goals for growth and development is critically important to build capacity for investors to understand transition risks, and to attracting foreign investment that contributes to the country’s climate agenda (Box 5.2). Given the cross-cutting nature of climate change, a strategic framework for addressing climate change should include a comprehensive and coherent multi-sector approach, integrating environmental targets and ambitions into sector strategies and plans. For instance, incorporating climate considerations in national infrastructure development plans and priorities can help avoid locking-in environmentally unsustainable infrastructure for decades. This may require the establishment of new connections between national sectoral planning processes in order to avoid repackaging existing sectoral plans into a climate strategy.

Box 5.2. The EU Green Deal’s integrated framework for the climate transition

The European Green Deal sets out a detailed vision to make Europe the first climate‑neutral continent by 2050, safeguard biodiversity, establish a circular economy and eliminate pollution, while boosting the competitiveness of European industry and ensuring a just transition for affected regions and workers. Under the EU Green Deal, the European Commission pledged to raise the GHG emissions reduction targets to 55% by 2030, compared to the previous target of 40%. To implement the increased ambition, on 14 July 2021 the Commission presented the ‘Fit for 55’ package, which contains legislative proposals to revise the entire EU 2030 climate and energy framework, including the legislation on effort sharing, land use and forestry, renewable energy, energy efficiency, emission standards for new cars and vans, and the Energy Taxation Directive. The Commission proposes to strengthen the emissions trading system, extend it to the maritime sector, and reduce over time the free allowances allocated to airlines. A proposed new emissions trading system for road transport and buildings should start in 2025, complemented by a new social climate fund with a financial envelope of EUR 72.2 billion to address its social impacts. New legislation is proposed on clean maritime and aviation fuels. To ensure fair pricing of GHG emissions associated with imported goods, the Commission proposes a new carbon border adjustment mechanism.

By offering a holistic and integrated approach to mainstream decarbonisation across a multi-sector regulatory framework, the Green Deal provides investors with a clear long-term trajectory for Europe’s climate transition. This long-term commitment and direction reduces uncertainty about regulation and taxation to advance the transition, and allows investors to better understand the transition risks associated with their operations going forward, and to take steps to mitigate these risks.

The investment promotion strategy must also reflect national climate objectives across priority sectors in alignment with the multi-sector strategic framework for addressing climate change. Concretely, it should translate national level emissions targets to science‑based targets for the private sector in order to drive responsible climate action by business. In this regard, it is important that the investment promotion strategy and its main features are developed in co‑ordination with other key ministries, including for instance the ministry of environment and the ministry of energy. The investment promotion strategy should be very clear and specific about targets, tools to reach the set targets, and performance indicators to measure progress. It should provide clear indications on its implementation, including how staff should be organised internally, what the main activities are that it should focus on, what the key performance indicators to measure outputs and outcomes are, and what procedures are in place to collaborate effectively with other relevant public agencies and stakeholders (e.g. the private sector). Clearly delineating the role of private investors, both domestic and foreign, in achieving climate objectives can help adequately tailor investment promotion efforts to target investors that help further these objectives. The government should consult with the private sector and other local stakeholders in the design and implementation of strategies and plans that are relevant for low-carbon investment, and regularly evaluate their effectiveness.

Ensure inter-ministerial and inter-agency co‑ordination and alignment

As is the case for other policy areas covered by the Policy Toolkit, a complex system of institutions design and implement investment, climate and sectoral strategies, and it is important for co‑ordination mechanisms to be in place to ensure their coherence and consistency, and to achieve desired outcomes related to FDI and carbon emissions. Overlapping and sometimes conflicting rules, procedures and regulations across ministries and levels of government, including between the central and provincial levels can create administrative burdens on investors (OECD, 2015[30]). Although co‑ordination is a fundamental and longstanding problem for public administrations, there is still no standardised method for approaching co‑ordination issues, and much of the success or failure of attempts to co‑ordinate appear to depend upon context. Overall, co‑ordination approaches and instruments should be matched to circumstances and policy areas. Instruments of co‑ordination can be based on regulation, incentives, norms and information sharing. They can be top-down and rely upon the authority of a lead actor or bottom-up and emergent (Peters, 2018[31]). Common approaches for co‑ordination are summarised in Box 5.3.

Box 5.3. Examples of inter-agency co‑ordination approaches and instruments

National strategies and action plans typically involve wide consultation and deliberation, and provide diagnostic overviews of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats associated with their stated objectives. If properly designed, national strategies and plans can set a shared vision of the goals pursued across climate and investment policy domains, and how one can contribute to the other. Costa Rica’s National Decarbonisation Plan, for instance, explicitly states that the priorities related to FDI attraction for decarbonisation will be addressed in co‑operation with the Ministry of Trade and Commerce (COMEX), the investment promotion agency (CINDE) and the export promotion agency (PROCOMER).

Dedicated agencies or ministries assume the leadership of the national policy agenda in some policy domains (e.g. environment, energy, investment) and often responsibility of co‑ordination. At the same time, inter-agency joint programming can draw together a number of interested agencies and facilitate co‑ordination and other aspects of governance as agencies share agenda and action.

The Centre of government (e.g. the President’s or Prime Minister’s Office) can bridge political interests and bureaucratic boundaries. High-level policy councils can also deal with aspects of policy co‑ordination although they have variable roles and composition across countries. In Jordan, for instance, the higher steering committee for green growth, responsible for the overall strategic framework for green growth, reports directly to the prime minister, who also sits in the high-level investment council, responsible for the country’s investment strategy, ensuring that the strategic directions of the two are aligned.

Informal channels of communication between officials or job circulation (of civil servants, but also experts and stakeholders) can play a role and suggest a relatively well-developed culture of inter-agency trust and communication. Such arrangements tend to work best where there already exists a relatively well-developed culture of inter-agency trust and communication.

Source: OECD (2022[36]), FDI Qualities mapping: A survey of policies and institutions that can strengthen sustainable investment.

Design and implement effective environmental assessment processes and ensure stakeholder involvement and consultation

Environmental assessment processes, including Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), are structured analytical and participatory approaches for obtaining and evaluating environmental information prior to its use in decision-making. This information consists of assessments of how the environment will be affected if certain alternative actions are implemented and advise on how best to manage environmental implications if one alternative is selected and implemented. SEA focuses on strategic and policy actions such as new or amended laws, policies, programmes and plans. EIA focuses on proposed investment projects such as highways, power stations, water resource projects and large‑scale industrial facilities, which are sometimes linked to the implementation of a policy or plan (e.g. extended highway network may be an outcome of a new transport policy). Environmental assessment systems are fundamental to ensure that international investments contribute to sustainable development, and in particular to climate and environmental goals. As an integral part of the policy programme and plan life‑cycle, SEAs guarantee that the policies, regulations and standards that influence the attraction and environmental performance of investments are aligned with national climate objectives. In Senegal, for instance, to ensure the success of the new energy policy, the government has set up a monitoring and evaluation system for major energy projects through an inter-ministerial committee chaired by the Prime Minister. EIA systems, additionally support investors in minimising environmental risks associated with their investment projects.

Strong political will is important for the effectiveness of EIA systems in mitigating potential adverse environmental impacts of FDI. When the EIA authority is under financial pressure or politically inferior to other government institutions that support the investment project, EIAs may be used to rationalise predetermined outcomes, rather than to provide independent and rigorous analysis, upon which the approval is based. In such cases underestimation of the role and impact of EIA can negatively influence the impact of foreign investments on the host country’s environment (Dung, 2019[32]). Strengthening the implementation of EIA systems is essential for their effectiveness in greening FDI and reducing its carbon impacts. In some countries investment proponents face major delays in the review and approval of EIAs due to lack of human and financial resources. Another factor exacerbating delays may be the lack of quality of EIA documents submitted to the authority, as a result of lack of capacity in the environmental assessment industry. Relevant authorities at national and subnational levels may also lack the capacity to monitor and audit implementation of investments to ensure compliance with EIA results (OECD, 2020[33]). Building capacity at national and subnational levels to review EIAs and reduce delays in this process, and improving the transparency and information systems supporting EIAs can significantly improve the environmental impacts of foreign investments.

Public consultation is a vital component of successful EIA/SEA systems and specific EIA/SEA studies. Timely and well-planned public consultation programmes will contribute to the successful design, implementation, operation and management of proposal actions. Stakeholder engagement also enhances the effectiveness of the EIA/SEA process. Stakeholders, including foreign multinationals, provide a valuable source of information on key impacts, potential mitigation measures and the identification and selection of alternatives. Their consultation further ensures the EIA/SEA process is open, transparent, and robust, and also that individual EIAs/SEAs are founded on justifiable and defensible analyses.

Collect data to monitor the impact of FDI on carbon emissions

Measuring and tracking the impact of FDI on carbon emissions, and its potential contribution to decarbonisation can help identify appropriate policy responses. The first section of this chapter presents a framework for understanding FDI impacts on emissions, and factors that may influence these impacts. The collection and production of timely and internationally comparable date on FDI by sector, is important for monitoring its contribution to decarbonisation. Supplementing this with firm-level surveys that capture different aspects of their environmental practices can provide policy makers with a valuable tool for self-assessment of FDI impacts on carbon emissions, and green growth more generally. Annex Table 5.A.1 provides a set of core questions and indicators that can guide policy makers in this self-assessment.

5.3.2. Adhere to international agreements and standards that reinforce climate objectives

Ratify major international agreements promoting climate action

Carbon emissions have global effects, regardless of where they were released, meaning that the impact of one country’s climate policies is dependent on the climate policies of other countries. Given the short‑term economic costs of climate policies, the ambition of domestic policies depends on the perceived economic impacts those policies may create, as well as the perceived risks of carbon leakage that may render domestic climate action vain. Policy makers, as well as industry and the general public, seek reassurance of commensurate action from their trade partners, through treaties or other forms of international agreement, whether bilaterally or multilaterally (OECD, 2015[23]). The international agreements that directly or indirectly influence carbon emissions and the economic activities that generate them include multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) negotiated at the global level, under the auspices of the UN. These MEAs span several environmental fields, including GHG emissions reductions, cross-border air pollution, soil and desertification, and environmental governance (Table 5.2).

The UNFCCC is the central forum for global negotiations on climate change and for international co‑ordination of climate policies, and plays a crucial role in advancing national climate policies. In December 2015, 196 states negotiated a landmark climate change agreement at the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) of the UNFCCC in Paris. The resulting Paris Agreement aims to limit climate change to 1.5°C global mean temperature change, and expects progressively more ambitious climate mitigation commitments from all parties over the coming decades. As of January 2021, 190 members of the UNFCCC are parties to the agreement, and 187 states and the EU, representing about 79% of global greenhouse gas emissions, have ratified or acceded to the Agreement (UNFCCC, 2015[2]). The central mechanism of the Paris Agreement is a ‘pledge‑and-review’ process. Every five years the parties submit increasingly ambitious nationally determined contributions (NDCs) that lay out mitigation plans, and may include ones related to adaptation. Parties are left to establish their own national policy framework to achieve the commitments outlined in such NDCs, but are required to report emissions, with progress reviewed by an independent review system. The Paris Agreement is instrumental in providing political space for policy makers to strengthen climate action domestically. Fulfilling the Paris Agreement will require substantial new domestic climate policies in each state party to the treaty, including pollution controls that also result in GHG mitigation, land use regulations, clean infrastructure investment targets, or policies aimed at fostering low-carbon innovations.

Technology transfer is a crucial element of the new international climate regime. Developing countries, led by India, advocated for strong technology transfer provisions, and in particular the increased availability of free intellectual property for the purpose of faster diffusion of clean technologies. The Paris Agreement also creates scope for further development of a regime for technology transfer: it establishes as norms the ‘strengthening of co‑operative action’ and ‘promoting and enhancing access,’ and builds on the ‘Technology Mechanism’ established under its predecessor treaty, the 2010 Kyoto Protocol. While little detail is provided as to how these norms should be pursued in practice, international trade and investment are likely to play a pivotal role in fostering the needed technology transfer.

Table 5.2. Summary of MEAs that influence GHG emissions

|

Year |

Title |

Theme |

Objective |

Parties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1979 |

Geneva Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (CLRTAP) |

Air pollution |

To protect human health and the environment against air pollution and to limit and, as far as possible, gradually reduce and prevent air pollution including long-range transboundary air pollution. |

51 |

|

1991 |

Espoo Convention on EIA |

Governance |

To prevent, reduce and control significant adverse transboundary environmental impact from proposed activities. |

44 |

|

1992 |

Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) |

Climate change |

To achieve stabilisation of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that prevents dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. |

197 |

|

1994 |

Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) |

Soil |

To combat desertification and mitigate the effects of drought, particularly in Africa, with a view to contributing to the achievement of sustainable development in affected areas. |

196 |

|

1994 |

International Tropical Timber Agreement (ITTA) |

Nature and biodiversity |

To promote and apply comparable and appropriate guidelines and criteria for the management, conservation and sustainable development of timber-producing forests. |

74 |

|

1997 |

Kyoto Protocol |

Climate change |

To ensure that greenhouse gas emission do not exceed the assigned amounts, with a view to reducing overall emissions of such gases by at least 5% below 1990 levels in the commitment period 2008 to 2012. |

192 |

|

1998 |

Aarhus Convention on Access to Information |

Governance |

To guarantee the rights of access to information, public participation in decision-making, and access to justice in environmental matters |

47 |

|

2015 |

Paris Agreement |

Climate change |

The Paris Agreement builds upon the UNFCCC Kyoto Protocol and commits all to undertake ambitious efforts to combat climate change and adapt to its effects, with enhanced support to assist developing countries to do so. |

192 |

Adhere to international agreements on RBC and promote environmental due diligence

Home country governments can also influence the impacts of outward FDI on global emissions by implementing international agreements on responsible business conduct (RBC), and encouraging environmental due diligence across supply chains. The OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines) recommends that businesses take due account of the need to protect the environment, including improving environmental performance in their own operations and supply chain and addressing any adverse environmental impacts of their own operations and their supply chains, within the framework of laws, regulations and administrative practices in the countries in which they operate, and in consideration of relevant international agreements, principles, objectives, and standards. In particular, Chapter 6 of the Guidelines on “Environment” addresses aspects such as environmental management systems, continual improvement of corporate environmental performance, training of workers on environmental matters, and raising environmental awareness. Adherence to the Guidelines and efforts to facilitate corporate compliance with the Guidelines is therefore instrumental in minimising any adverse environmental impacts associated with FDI, and increasing its contribution to climate and environmental objectives.

The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct provides practical support to enterprises on the implementation of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, by providing plain language explanations of its due diligence recommendations and associated provisions (OECD, 2018[34]). Implementing these recommendations helps enterprises avoid and address adverse impacts related to workers, human rights, the environment, bribery, consumers and corporate governance that may be associated with their operations, supply chains and other business relationships. Further tailored guidance for businesses on addressing climate risks in sector supply chains is included in the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment and Footwear Sector (OECD Garment Guidance), which has a risk module dedicated to GHG emissions, and the OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains. These guidance advocates a risk-based approach to addressing GHG emissions in a company’s supply chain, using leverage with suppliers to encourage suppliers to reduce emissions and to support suppliers directly in implementing measures to reduce GHG emissions.

Growing demands to hold corporations accountable for their climate impacts are leading some courthouses to draw heavily on international instruments like the OECD Guidelines award legal victories to citizens, by ordering multinational giants to cut GHG emissions of their operations and those of their supply chains independently of their home and host country regulations (Box 5.4). Such rulings raise questions on the need for mandatory due diligence legislation that defines the obligations of companies to prevent environmental damage, and enables public regulators and judges to enforce such legislation.

Box 5.4. The Shell climate ruling

Basing its verdict on the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines), in May 2021, a Dutch court ruled that Royal Dutch Shell (Shell) must reduce its CO2 emissions by 45% by 2030 (compared to 2019), regardless of the policies of the Dutch Government. The ruling asserts that Shell’s total CO2 emission levels, from its own operations and from those of its supply chain and end users, present a breach of the company’s legal obligation to prevent climate change, explicitly linking climate change to human rights. It also emphasises the responsibility Shell headquarters has over the entire Shell group, thereby acknowledging the parent companies’ responsibility for subsidiaries. The ruling makes clear that the severity of the impact of climate change on human rights justifies the economic sacrifices Shell will be required to make. This historic ruling is the first to impose a clear and measurable emissions reduction target on a company and its value chain, making clear that preventing climate change harm is an essential element of responsible business conduct as defined by the UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines.

Ensure that investment and trade agreements reinforce domestic environmental laws and allow for sufficient domestic climate policy space

Trade and investment agreements can promote and facilitate trade and investment in environmental goods and services. However, depending on the way in which they address or fail to address environmental concerns, these treaties may in some cases be perceived to conflict with climate objectives and with the measures taken by governments to implement the Paris Agreement.

WTO rules may prevent governments from regulating traded goods on the basis of the climate impacts of their production (OECD, 2020[9]). Governments may seek to protect low-carbon industries as a means of achieving long-term decarbonisation targets, and these trade protections may run contrary to free trade principles. Investment treaty rules and interpretations of them can allow investors to claim damages and lost profits in investor-state arbitration from governments that take measures to decarbonise their economies (Financial Times, 2022[35]). Governments with both an interest in seeing robust climate action and a deep involvement in investment and trade negotiations are in an important position to ensure alignment and mutual reinforcement across climate, trade and investment regimes.

Comprehensive free trade agreements (FTAs) seek to reconcile trade, investment and environmental policy objectives and often address issues related to the environment in a dedicated chapter. Some existing environment chapters include obligations such as effective enforcement of environmental laws, domestic procedural protections, or promotion of public participation in environmental matters. In addition, FTAs increasingly seek to promote international co‑operation on a variety of policy objectives, including climate action. References to specific climate objectives, such as the removal of tariff and non-tariff trade barriers related to climate‑friendly goods and services, or the reduction of fossil fuel subsidies, are sometimes included in hortatory provisions about shared government goals and imperatives (e.g. EU-Singapore FTA 2018, Art. 7.1 and 12.11). In other cases, FTA treaty parties commit to specific measures of co‑operation, such as international responses to climate change; exchanging expertise on environmental regulations and their implementation; sharing investor records of compliance with the home state environmental laws; or establishing a committee to supervise the enforcement of environment and trade matters covered in the agreement (USMCA 2018, Art. 24.26).

In international investment agreements (IIAs) – defined as standalone investment treaties (e.g. BITs) and the investment provisions included in regional FTAs – the nature, design, context and interpretation of treaty provisions used for claims and dispute settlement arrangements are of key importance for impact on environmental and climate action. For example, investment protection obligations, if not carefully drafted and interpreted, may come into conflict with several principles and performance standards included in multilateral environmental agreements (e.g. precautionary principle, polluter pays principle). Measures to safeguard the implementation of multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) can therefore include clarifications of hierarchy in the event of a conflict to the advantage of the environmental agreements.

Poorly drafted investment agreements or broad arbitral interpretations that remain unaddressed may limit the ability of governments to restrict new fossil fuel investment projects, or increase the perceived costs of phasing them out. Investment agreements can be adjusted to preserve policy space to regulate on environmental matters. The scope of absolute protections and government action with regard to their interpretation are key factors affecting policy space for non-discriminatory regulation. A number of recent treaties limit protection to discrimination or to direct expropriation and discrimination. Other recent treaties provide for state‑state dispute settlement (SSDS) rather than investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) for investment protection claims.

Express language addressing the environment is also increasingly used in investment agreements to seek to avoid conflicts with climate objectives, although concrete impact in preserving policy space has been difficult to demonstrate. A growing number of IIAs include clauses in the body of the treaty that seek to reserve the host state’s right to regulate environmental matters. The scope of the environmental concern that the clauses describe varies in specificity. In some cases, provisions limit treaty coverage, and potential recourse to international arbitration, to investments made in accordance with applicable laws, including environmental law. A recent treaty carves out non-discriminatory and legitimate environmental measures from the scope of ISDS and provides governments with the power to jointly apply the clause (China-Australia FTA, 2015, Section B). The fear of a race to the bottom in the competition to attract foreign investment has motivated the inclusion of clauses in IIAs that discourage or prohibit the lowering of environmental standards for the purpose of investment attraction. Such clauses have appeared in IIAs since 1990 but have only recently been subject of a few claims.

Trade and investment agreements can also help to reinforce domestic laws and regulations related to the climate and strengthen environmental governance. For example, some agreements require the parties to ratify and effectively implement their obligations under an MEA. For instance, in the recently signed agreement between the EU and UK, each signatory commits to effectively implementing the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement (EU-UK Trade and Co‑operation Agreement 2020, Art. 8.5). A similar proposal has been made by the EU in relation to the modernisation of the Energy Charter Treaty.

Recent IIAs have begun to seek to influence business conduct, generally through hortatory provisions. More demanding provisions in a few treaties may require business to comply with environmental assessment and screening processes; maintain an environmental management system; observe RBC standards related to the environment; or conduct an environmental impact assessment (e.g. Morocco-Nigeria BIT 2016, Arts. 14; 18, 24).

Going forward, investment and trade agreements should form part of wider policy efforts to create incentives for investments that help transition to low-carbon energy infrastructure, reform the current reliance on fossil fuels or correct regulations that weaken the business case for investment and innovation in low-carbon infrastructure. Efforts to understand the impact of investment treaties on the environment and climate action are therefore vital. These effects are under consideration in ongoing OECD work on the future of investment treaties, which will focus in particular on climate change. Results from this work will be reflected in future iterations of this Policy Toolkit.

Table 5.3. Illustration of how FTAs and IIAs explicitly refer to environmental protection

|

Policy objective |

Type of reference |

Example |

|---|---|---|

|

Encourage international co‑operation |

General promotion of progress in environmental protection and co‑operation |

EU-Singapore FTA (2018), Arts. 7.1, 12.11 (Trade and Sustainable Development) |

|

Commitment to co‑operate on environmental matters |

USMCA (2018), Art. 24.25 (Environment) |

|

|

Reinforce domestic law |

Explicit safeguards or enhancements of international environmental agreements |

CARIFORUM-EU FTA (2008), Art. 72 |

|

Non-lowering of environmental standards for the purpose of attracting investment |

Japan – Jordan BIT (2018), Art. 20 |

|

|

Preserve domestic policy space |

Explicit affirmation of environmental regulatory power of host state |

Korea – Uzbekistan (2019), Art. 17 |

|

Carve‑out clauses for environmental measures with respect to treaty provisions |

China – Australia FTA 2015, Art. 9.8 |

|

|

Exclusion of non-discriminatory environmental measures from ISDS |

China – Australia FTA 2015, section B |

|

|

Influence investor conduct |

Investor obligations related to environmental protection |

Morocco – Nigeria BIT (2016), Arts. 14(1), (3); 18(1), (4),24(1) |

Note: This table contains selected examples of FTA and IIA provisions, based on the OECD (2022[36]) FDI Qualities Mapping. The impact of these references is uncertain and is likely to depend on factors like treaty design, context and interpretation.

5.3.3. Ensure that domestic regulations reinforce climate objectives

Ensure transparency, openness and non-discrimination

A fair, transparent, clear and predictable regulatory framework for investment is a critical determinant of investment decisions and their contribution to decarbonisation (OECD, 2015[30]). Transparency and predictability matter even more when considering returns on investments with long time horizons, to ensure planning certainty and clear expectations on investment and climate policies and actions. Strong government commitments at both the international and national level are necessary to catalyse low-carbon green investment. With clear, long-term and ambitious signals and emission goals, nationally and internationally, investors and markets will have a better view on where to invest (OECD, 2015[23]). While these signals are important for all business, they are crucial for giving the confidence to multinational investors with the requisite capacity and skills to invest in risky new technologies that are highly capital- and R&D-intensive.

The non-discrimination principle provides that investors are treated equally, irrespective of their ownership. Discriminatory restrictions on the establishment and operations of foreign investors can deter FDI in general, and diminish its low-carbon impacts. While manufacturing industries have undergone significant FDI liberalisation worldwide, over the last three decades, some sectors that present significant opportunities for decarbonisation efforts remain partly off-limits to foreign investors in many countries – notably, transport, electricity generation and distribution, and construction. Many services, typically associated with lower carbon emissions and in some cases crucial for energy-saving technologies (e.g. digital services), are also more frequently restricted to foreign participation (Gaukrodger and Gordon, 2012[37]). Restrictions on FDI in these sectors are likely to result in sub-optimal flows of investment, limit the transfer of know-how and hamper the deployment of low-carbon technologies.

Discriminatory measures can also be used to actively target low-carbon investments, enhance their spillover potential, or deter carbon intensive‑investments. Technology transfer obligations could support low-carbon spillovers to domestic firms. However, trade‑distorting discriminatory measures, such as local content requirements (LCRs) and subsidies, even if targeting low-carbon products, can hinder international investment across the value chains by raising the cost of inputs for downstream activities. Particularly in small developing countries with low domestic demand and relatively poor supporting infrastructure, policies of this type could increase the costs of domestically purchased environmental goods (OECD, 2015[30]).

The opportunities presented by international investment can sometimes bring risks, including for security interests of host countries. Since 2016, governments are taking these risks increasingly seriously and most OECD countries now have screening mechanisms allowing them to intervene in a much broader section of the economy if international investment may threaten their essential security interests (OECD, 2020[38]). Investment screening could conceivably affect the energy transition and low-carbon innovation in several ways: energy infrastructure (e.g. energy storage) is itself considered “critical infrastructure” in many countries (EU, 2019[39]); advanced technologies (e.g. semiconductors) are likewise typically included under investment review mechanisms, with knock-on effects on energy-related technologies (e.g. solar panels, smart grids). Finally, foreign-funded research and international R&D co‑operation, which may be needed or accelerate the energy transition, have come under scrutiny for their national security implications as well, and governments may heighten their attention to such arrangements. Policymakers need to balance the benefits of international investment and international co‑operation with the potential implications for essential security interests and seek to mitigate and manage the associated risks. While scrutiny of investment in sensitive sectors is necessary and legitimate, governments should ensure that such screening remains closely tailored to risk and that it is guided by the principles of transparency, predictability, proportionality, and accountability as described in the OECD Guidelines for Recipient Country Investment Policies relating to National Security (OECD, 2009[40]).

Strengthen competition and property rights

Competition rules are designed to promote and protect effective competition in markets, encouraging firms to invest efficiently and to innovate and adopt more energy-efficient technologies. Such competitive pressure is a powerful incentive to use scarce resources efficiently and complements climate policies and regulations aimed at internalising the environmental costs of carbon emissions. By helping to achieve efficient and competitive market outcomes, competition policy hence contributes in itself to the effectiveness of climate policies. These pressures not only influence the foreign investor’s operations and direct carbon impacts, but also push local businesses to imitate or improve foreign low-carbon technologies in order to remain competitive.

Competition policy may be especially important for supporting decarbonisation of the power sector, which is traditionally characterised by vertically integrated monopolies. Unbundling the power sector by separating power generation, transmission and distribution functions can help create more space for foreign investment. Moreover, by opening competition in power generation, unbundling provides more space for clean energy technologies to enter the market and can therefore stimulate changes in the national energy mix. The decentralised nature and the smaller generation capacity of clean energy projects compared to their fossil fuel counterparts, makes independent power production well-suited for mainstreaming clean energy technologies. In the areas of transmission and distribution, increased competition can also render the national energy network more flexible, increasing its capacity to accommodate both on- and off-grid renewable energy (OECD, 2015[41]). Even where structural separation has been implemented, dominant incumbent enterprises may deter independent renewable power producers from entering a market through tender procedures (Ang, Röttgers and Burli, 2017[11]). Therefore, countries in which regulators adequately address anticompetitive practices by incumbent utilities, including state‑owned enterprises (SOEs), are likely to be more attractive destinations for multinationals seeking investment opportunities in renewable power. In general, policy makers need to ensure that producers of low-carbon electricity benefit from non-discriminatory access to the grid, as uncertain grid access increases project risk; investment in the grid is open to private investment, including foreign investment (potentially through joint ventures); private developers benefit from non-discriminatory access to finance, e.g. from state‑owned banks; tenders for public procurement are carefully designed with clear and transparent bid evaluation and selection criteria (OECD, 2015[23]).

Intellectual property rights (IPRs) create strong incentives for innovation as they ensure that investors earn a fair return on their technological innovations. IPRs can be used to generate revenues from licences, encourage synergistic partnerships, or create a market advantage and be the basis for productive activities, and are especially important for the development of low-carbon technologies, which are both research- and capital-intensive (IRENA, 2013[22]). At the same time IPRs can be perceived as an obstacle to the transfer of low-carbon technologies from developed and emerging economies to developing countries. Defining an IPR regime conducive to low-carbon innovation is particularly challenging as it needs to strike a balance between providing a secure environment for investment in innovation, while ensuring that small investors can afford valuable technologies. The importance and impact of IPRs on the transfer of technology are likely to be context specific. In remote areas of low-income countries, the need to expand energy access requires the rapid deployment of well-known renewable energy technologies, for which IPR protection might be less critical. In some African markets very few low-carbon technologies are protected under IP regimes (Haščič, Silva and Johnstone, 2012[42]). By contrast, a strengthening of the IPR regime is likely to play a positive role in emerging economies, responsible for a third of global patenting in clean energy technologies, and representing most of the projected growth in energy demand in the coming decades. With two‑thirds of the patenting in clean energy technology being submitted by foreign companies, consolidating the IPR regime could give more incentives to foreign developers to transfer technologies to these emerging markets (OECD, 2015[41]).

The ability to enforce contracts and minimise transaction costs associated with litigation plays an important role in investment decisions in general, but may be crucial for largescale low-carbon infrastructure projects, which typically require a set of complex and interlinked contractual arrangements. The potential costs of litigation are magnified by the many risks associated with low-carbon infrastructure projects (e.g. completion risk, technology risk, revenue risk, supply risk, weather risk, etc.), and may disproportionately affect smaller investors (OECD, 2015[41]). Securing land use rights is similarly vital for large‑scale utility projects, which so far have dominated renewable energy investment in developing countries. Most renewable energy plants demand more surface per megawatt installed than their fossil-fuel counterparts, and will require the company leading the project to engage with more than one landowner. Therefore, although not strictly related to low-carbon investments, inadequate property registration systems can increase the transaction costs associated such projects, particularly in the area of clean energy investments. At the same time, governments need to ensure that land concessions do not undermine the subsistence of vulnerable members of the population, which may depend on plots of land that offer the critical natural renewable resources. Prior mapping of natural resources and stakeholder consultations can help minimise these risks.

Set environmental standards that are aligned with national climate objectives

Environmental performance standards, such as emissions standards, restrict the emissions or energy use of vehicles, power plants, buildings, appliances and industrial processes. For instance, fuel economy standards apply to the fuel efficiency of new road vehicles, and blending mandates apply to the use of biofuels in transport. Building standards apply to the thermal insulation of new buildings or to the retrofitting of old ones. Emissions standards of power plants regulate the carbon intensity of their electricity mix. Efficiency standards for consumer appliances remove certain products from the markets. Given that performance standards require, the uptake of more efficient technologies, but do not make their use more expensive, not all energy-efficiency improvements result in net energy savings (OECD, 2019[43]). Counter to the pollution haven hypothesis, there is little and often conflicting empirical evidence that investors locational decisions are driven by differences in stringency of environmental standards and regulations. Indeed adopting regulations and standards that reinforce climate goals can help level the playing field for foreign investments in low-carbon technologies, services and infrastructure. Countries should indeed regularly assess whether their technology and performance standards are in line with long-term climate goals, as strong vested interested may result in targets set at the most feasible level rather than the optimal level necessary to meet objective (OECD, 2015[23]).