This chapter provides a Policy Toolkit to help governments boost the impacts of foreign direct investment (FDI) on job quality and skills. It describes the main transmission channels of FDI impacts on labour market outcomes and related policies and institutions that can act upon these channels. It builds on the OECD Policy Framework for Investment and is aligned with other OECD instruments and strategies such as the Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the 2018 Jobs Strategy.

FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit

3. Policies for improving FDI impacts on job quality and skills

Abstract

Main policy principles

1. Provide strategic directions and promote policy coherence and co‑ordination on investment, employment and skills development

Ensure that national development or economic plans provide coherent and strategic directions on investment, employment and skills development objectives and that investment considerations are integrated in employment and skills strategies and vice versa.

Develop a dedicated strategy that articulates the government’s vision on the contribution of investment to job quality and skills development. The strategy sets the goals, identifies priority policy actions and clarifies responsibilities of institutions and co‑ordinating bodies.

Strengthen co‑ordination both at strategic and implementing levels by establishing, if inexistent, appropriate co‑ordinating bodies or by considering to expand the mandate and composition of existing ones, such as boards of investment promotion agencies and national skills councils.

Use public-private consultations and inclusive decision-making processes, including social dialogue, to negotiate, receive feedback and build consensus around reforms or programmes at the intersection of investment, employment and skills development.

Involve investment bodies in labour market information and skill needs and anticipation exercises to reduce information gaps and inform the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of employment and skills policies that are better targeted.

2. Ensure that regulations support investment and labour market adjustments while promoting high-quality jobs and protecting the most vulnerable

Promote labour provisions in international investment and trade agreements that raise labour standards, including by referring to ILO’s international conventions and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (MNEs), allow for sufficient domestic policy space and establish institutional mechanisms to promote co‑operation and monitoring of labour commitments

Ensure adaptability of product and labour markets to foreign investors’ entry and operations, and that the costs and benefits are fairly shared between workers and firms, by fostering competition and labour mobility while providing a level of employment stability that encourages learning in the workplace.

Periodically assess existing regulatory restrictions on FDI against evolving public policy objectives on job creation and skills development and, where relevant, consider streamlining or removing them. Involve relevant bodies and social partners in such assessments.

Set and enforce labour standards that support better working conditions to ensure that those practiced by foreign firms are not less favourable than those by domestic firms and are applied with the same level of diligence in all businesses and regions, including special economic zones.

Ensure the right to collective bargaining and workers’ voice arrangements, including within foreign MNEs and in special economic zones, and that these are adapted to a changing world of work and can promote collective solutions to emerging issues and conflicts.

3. Stimulate labour demand and develop skills through higher investment and targeted active labour market policies and programmes

Financial support, particularly corporate tax relief, which aims at attracting FDI in job-creating or skill-intensive sectors or in regions with low employment rates should be subject to regular reviews. If used, favour support that is tied to the performance of firms in terms of jobs created or trained workers, including workers of suppliers, and ensure that it addresses specific market failures and is developed through concerted efforts with all relevant bodies.

Develop training programmes in line with development and investment strategies and in partnership with social partners, and that provide transferable, certifiable skills to facilitate labour mobility and help workers and job seekers move to better jobs, including those adversely affected by changing labour markets, the low-carbon transition and evolving needs of MNEs.

4. Align investment opportunities with labour market potential by addressing information failures and administrative barriers

Adopt investment promotion activities based on the existing skill base and labour market potential that lower information barriers for investors. Support investors in identifying suppliers with high labour standards, and thereby also incentivise other companies to raise theirs.

Ensure that job information and matching services reduce information gaps and lower search costs in labour and product markets and stimulate internal labour mobility, particularly of job seekers or workers in communities near foreign firms’ activities. Develop these services through concerted efforts or jointly between investment bodies and public employment services.

Raise awareness about labour standards and incentivise companies to disclose their compliance with them, including local suppliers engaging with foreign buyers that conduct due diligence checks to assess risks in their supply chain.

Ensure transparency and consistency of procedures and requirements for obtaining permits from labour authorities, including permits for foreign workers.

3.1. Building more inclusive labour markets in a globalised economy

Achieving more inclusive labour markets are increasingly key priorities for governments – in developed and developing countries alike. While the global economy has been recovering from the global financial crisis for several years now, employment and wage growth remain sluggish, and levels of income inequality are unprecedentedly high in most countries. The COVID‑19 pandemic has taken an additional toll on labour market resilience by causing activity to collapse and unemployment to soar. Poverty will rise for the first time since 1998, with hundreds of millions of jobs lost, and wage disparities will widen as income losses have been uneven across workers (OECD, 2020[1]).

Policies in favour of job quality and skills development can play a significant role in building forward more inclusive labour markets and ensuring a fair and sustainable recovery. They can help improve well-being of individuals as well as support labour force participation, productivity and growth. Creating better jobs and developing skills figure prominently in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG4 (education) and SDG8 (economic growth). These goals aim to increase the number of people with relevant skills for employment and ensure that all can work productively and receive fair wages. Employment creation, social protection, rights at work, and social dialogue – the four pillars of ILO’s Decent Work Agenda – are an integral element of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Creating good jobs is also at the core of the OECD Jobs Strategy, which goes beyond job quantity and considers job quality, in terms of both wage and non-wage working conditions, as a key policy priority (Box 3.1). The Strategy also insists on the need to equip people with the right skills in a context of rapidly changing skills demands.

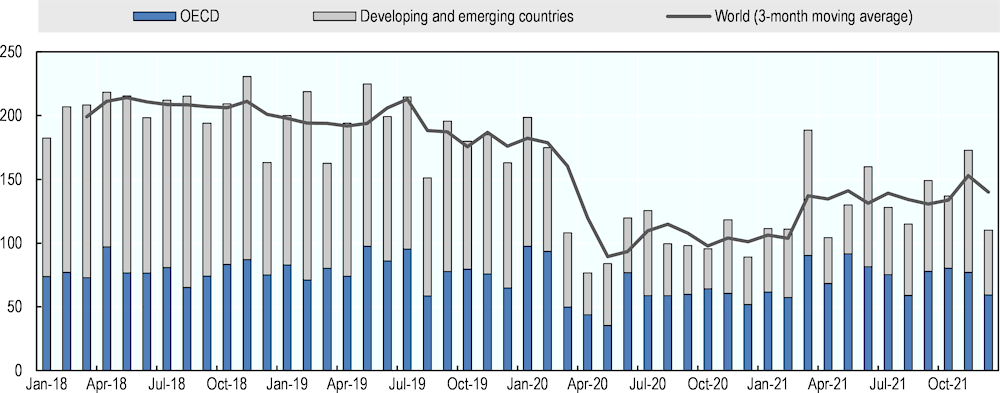

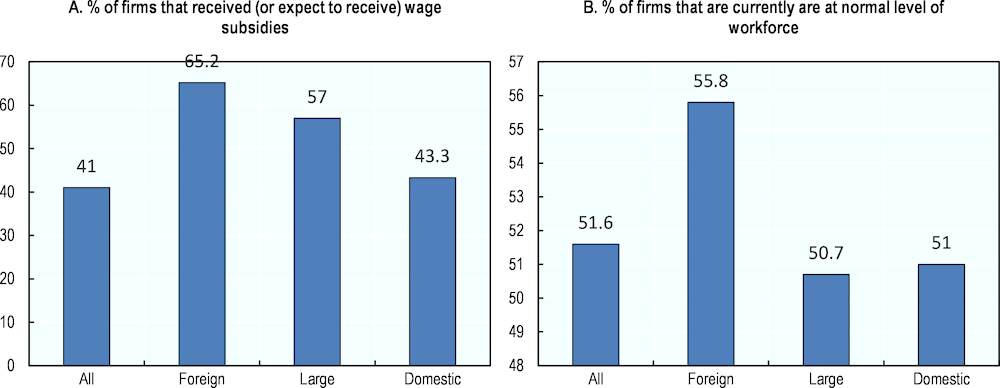

Yet governments still lack a comprehensive policy framework that can help them think about how private investment – a key driver of labour market outcomes – influences job creation and skill upgrading. Investment, and particularly foreign direct investment (FDI), together with international trade, technological change and digitalisation, have been shaping the world of work, with both positive and adverse impacts on host countries’ labour markets (OECD, 2019[2]). The COVID‑19 crisis is the most recent illustration of that, with the fall in global FDI adversely affecting job creation (Figure 3.1). Prior to the pandemic FDI flows were creating approximately 180 000 jobs every month, and considerably more in developing and emerging countries than in OECD countries. Between January and April of 2020, FDI-induced job creation contracted by over 60% globally. Furthermore, many of the jobs affected by the pandemic depend on the operations of MNEs and their suppliers in global value chains (GVCs). However, the pandemic has revealed how MNEs return to pre‑crisis workforce levels more rapidly than domestic firms and adapt faster to new forms of work by ramping up remote working (OECD, 2020[1]; OECD, 2022[3]).

Figure 3.1. The impact of the COVID‑19 crisis on jobs created through greenfield FDI

Source: OECD calculations from Financial Times fDi Markets.

3.2. FDI impacts on job quality and skills

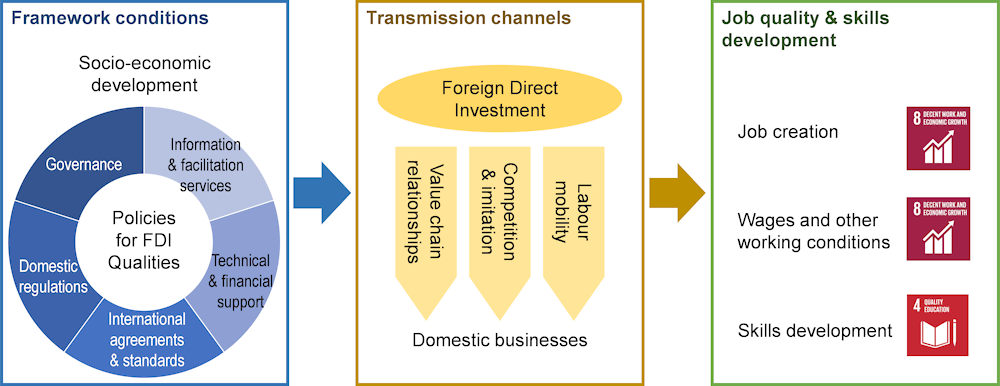

FDI can have varying effects on host country labour market outcomes (Figure 3.2, right box). The establishment of a greenfield investment or a change in the nationality of a firm’s ownership affects the demand for skilled and unskilled labour, with concomitant effects on employment and wages. Evidence shows that FDI has broadly positive impacts on job creation and earnings, but not all countries and all segments of the population benefit equally (OECD, 2019[2]). More FDI often leads to wage dispersions across firms and workers, mostly due to an increase in the skill premium. FDI can also affect other working conditions, including job security, occupational health and safety at work and core labour rights. Whether FDI improves or undermines working conditions depends on the type of activity of foreign firms and the extent to which they export home country practices and norms or adopt instead those of the host country.

Figure 3.2. Conceptual framework: FDI impacts on job quality and skills development

FDI effects on labour market outcomes involve several transmission channels (Figure 3.2, middle box). Outcomes can result from foreign firms’ direct operations in the host country, such as hiring new workers or firing incumbents following a foreign takeover or offering better or worse working conditions than domestic firms. Foreign firms’ direct operations have also spillover effects arising from:

1. Their value chain relationships with domestic firms, whether buyers or suppliers

2. Market interactions through competition and imitation (or learning) effects

3. Labour mobility of workers between foreign and domestic firms.

Value chain relationships or labour mobility between foreign and domestic firms can lead to knowledge sharing, and in turn raise productivity, wages and employment. The same spillovers occur when domestic firms imitate foreign competitors. FDI spillovers on labour market outcomes are often specific to certain segments of the workforce, industries, or locations. They are also not always positive if, for instance, foreign firms have irresponsible labour practices with their suppliers – particularly if the business relationship involves an activity with a higher risk of informal employment – or if competition for talent leads to lower quality of skilled labour in domestic firms. The intensity of such adverse impacts often depends on how fast the labour market adjusts to shocks. For instance, FDI does not increase the share of skilled workers and worsens wage disparities when skills shortages are severe and labour mobility is constrained.

The direction and magnitude of the combined direct and spillover effects of FDI on labour market outcomes ultimately depends on the economic structure of the host country and domestic firms’ characteristics (size, productivity level, skill-intensity, business and labour practices), labour market characteristics (employment levels, skill base, unionisation rates, etc.) and the policies and institutions in place (Figure 3.2, left box). While the next section focuses on the policies, the following sub-sections describe how FDI affects specific outcomes, namely employment, wages and non-wage working conditions and skills. Annex Table 3.A.1 provides detailed questions for governments to self-assess the impacts of FDI on labour market outcomes.

Box 3.1. The OECD Jobs Strategy, Skills Strategy and Job Quality Framework

The key policy recommendations of the 2018 OECD Jobs Strategy are organised around three principles:

I. Promoting an environment in which high-quality jobs can thrive. Good labour market performance requires a sound macroeconomic framework, a growth-friendly environment and skills evolving in line with market needs. Adaptability in product and labour markets is also needed, and the costs and benefits of this should be fairly shared between workers and firms, as well as among workers on different contracts by avoiding an over-reliance on temporary (often precarious) contracts through balanced employment protection schemes.

II. Preventing labour market exclusion and protecting individuals against labour market risks. Supporting the quick (re)integration of job seekers in employment is a top priority, but the new strategy also highlights the importance of addressing challenges before they arise by promoting equality of opportunities and preventing the accumulation of disadvantages over the life‑course.

III. Preparing for future opportunities and challenges in a rapidly changing economy and labour market. People will need to be equipped with the right skills in a context of rapidly changing skills demands. Workers also need to remain protected against labour market risks in a world where new forms of work may arise.

The OECD also developed a framework for measuring and assessing job quality that guided its 2018 Jobs Strategy. The objective was to revise the 2006 Strategy, which had largely focused its recommendations on the quantity of jobs. The OECD Job Quality Framework measures three aspects of job quality: earning quality (including distributional aspects), labour market security and the quality of the working environment.

The key policy recommendations of the 2019 OECD Skills Strategy are organised around three components:

I. Developing relevant skills over the life course. To ensure that countries are able to adapt and thrive in a rapidly changing world, all people need access to opportunities to develop and maintain strong proficiency in a broad set of skills. This process is lifelong, starting in childhood and youth and continuing throughout adulthood. It is also “life‑wide”, occurring not only formally in schools and higher education, but also non-formally and informally in the home, community and workplaces.

II. Using skills effectively in work and society. Developing a strong and broad set of skills is just the first step. To ensure that countries and people gain the full economic and social value from investments in developing skills, people also need opportunities, encouragement and incentives to use their skills fully and effectively at work and in society.

III. Strengthening the governance of skills systems. Success in developing and using relevant skills requires strong governance arrangements to promote co‑ordination, co‑operation and collaboration across the whole of government; engage stakeholders throughout the policy cycle; build integrated information systems; and align and co‑ordinate financing arrangements.

3.2.1. FDI creates both direct and indirect job opportunities but not necessarily for all

FDI affects employment growth or contraction through changes in labour demand. Effects differ by investor entry mode (greenfield project versus M&A) and vary by workforce type (skilled vs. unskilled). Greenfield FDI has a positive and direct effect on the demand for labour, leading to job creation, at least in the short term. A foreign takeover of a domestic firm could either have a positive or negative direct effect on jobs, but evidence shows that it can boost employment as acquired firms’ productivity and market share grow (Coniglio, Prota and Seric, 2015[7]; Ragoussis, 2020[8]). In contrast, a divestment by a foreign firm can lead to a drop in employment (Borga, Ibarlucea Flores and Sztajerowska, 2020[9]; Javorcik and Poelhekke, 2017[10]). Irrespective of the entry mode, foreign firms often have a higher demand for skilled workers than domestic firms due to technology advantages (Bandick and Karpaty, 2011[11]; Hijzen et al., 2013[12]).

Whether there will be net employment growth will also depend on FDI spillovers on domestic firms operating in the same value chain, industry or geographical area. Foreign firms could introduce labour-saving techniques that are then adopted by domestic firms through imitation effects, leading to a transitory decline in labour demand, but the progressive integration of foreign firms into the local economy can create a positive effect on jobs in the long run (Jude and Silaghi, 2016[13]; Lee and Park, 2020[14]). FDI may also raise employment at domestic firms in the same location, but only for higher-skilled workers (Setzler and Tintelnot, 2021[15]; Steenbergen and Tran, 2020[16]). FDI spillovers on employment growth are found to be negative, if domestic firms are geographically far from foreign firms as imitation effects are less likely to occur while market competition effects are less sensitive to distance (Lembcke and Wildnerova, 2020[17]).

Foreign and domestic firms’ adjustments on the labour market are broadly, albeit not totally, comparable (OECD, 2019[2]). During the COVID‑19 pandemic, the resulting decline in FDI as well as crippled MNEs operations adversely affected job creation, with knock-on effects on incomes. For instance, the decline in greenfield FDI reduced potential job creation by half in the first five months of 2020 (OECD, 2020[1]). Nonetheless, foreign businesses have cut jobs less than domestic firms, although many still had had to lay off workers or reduce working hours. Perhaps some MNEs are more resilient to disruptions by relying on a larger set of suppliers and buyers. In addition, foreign firms have managed better than their domestic peers to adapt their modus operandi to the new work realities by ramping up remote working.

3.2.2. FDI raises wages but can also exacerbate disparities if absorptive capacities are poor

In a competitive labour market, there is no reason why comparable foreign and domestic firms should pay different wages to workers with similar skills. Wage differences between the two groups arise, however, often because of other firm- and industry-specific characteristics (Hijzen et al., 2013[12]). Indeed, it is membership in a multinational production network – instead of foreignness – that generates the foreign-firm premium (Setzler and Tintelnot, 2021[15]). Characteristics include firms’ size, productivity level, workforce skill intensity, product market power, and working conditions, such as job insecurity. Foreign firms may still pay higher wages to workers with similar skills and tasks, for example, to reduce turnover and lower the risk of technology transfer to competing firms through labour mobility.

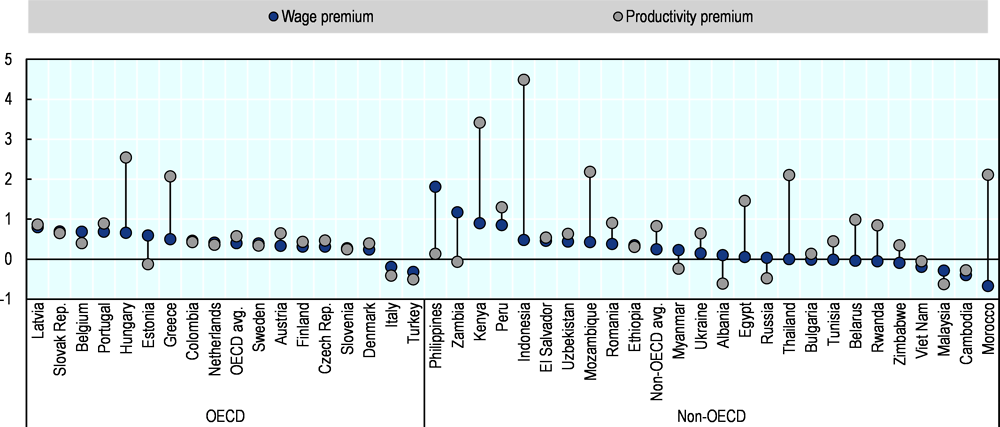

The FDI Qualities Indicators and wider evidence confirm the role of productivity, technology and skills as engines to enhance living standards: foreign firms pay higher wages than domestic firms. This is true only to some extent, however. Labour productivity in foreign firms is on average 72% higher than in domestic firms, but foreign firms pay only 31% higher wages, and this gap is larger among non-OECD countries (Figure 3.3). This means that performance premia of foreign firms are not fully translated into wage benefits for workers, possibly because MNEs are more active in highly concentrated markets – which in turn can generate rents. Such rents, and how they are shared with workers, can be due to policy pitfalls, such as barriers to competition (Criscuolo et al., 2020[18]). In developing countries, the foreign wage premium is smaller when institutional quality is higher (Blanas, Seric and Viegelahn, 2019[19]).

Foreign companies do not necessarily lift wages in all sectors and for all workers. The largest wage gains often benefit skilled workers and, in the case of a foreign takeover, those moving from domestic to foreign firms, rather than incumbents, revealing the importance of labour mobility as a crucial transmission channel of FDI impact on wages, at least in the short-run (Hijzen et al., 2013[12]). Foreign firms in low-paid activities do not always pay higher salaries than their domestic peers, however (OECD, 2019[2]). Foreign firms also do not necessarily improve earning conditions of all workers within the firm. For instance, following a foreign takeover, workers at the bottom-end of the wage distribution may not experience as much wage growth as they would have, had their firm not been taken over by a foreign firm (OECD, 2008[20]).

Foreign entrants’ competition for talent with domestic firms drives up wages, but potentially reduces the ability of the latter to hire or retain more skilled workers (Lu, Tao and Zhu, 2017[21]). This effect is stronger, and lasts longer, in industries facing skills shortages and in locations with limited labour mobility. Beyond raising the demand for labour, especially of skilled workers, FDI affects competitors’ wages through skill-biased technological transfer (imitation effects). Studies point to increased wages in domestic firms as a result of FDI in the same industry or location, particularly in developing countries where skilled labour is scarcer and the technology gap more substantial (Hale and Xu, 2020[22]). In a geographically large country like the United States, foreign firms’ operations substantially increase the wages of higher-earning workers in local domestic firms (Setzler and Tintelnot, 2021[15]). FDI effects on wages can also occur in upstream or downstream firms having value chain relationships with foreign firms, but empirical studies are inclusive on the direction of these effects. The FDI Qualities Indicators show, to some extent, that local sourcing by foreign firms amplifies positive spillovers of FDI on wages (OECD, 2019[2]).

Figure 3.3. Foreign firms’ wage and productivity premia in OECD and emerging countries

Note: The figure shows OECD and non-OECD countries for which World Bank Enterprise Surveys were available from 2015 and beyond.

Source:OECD (2022[3]), FDI Qualities Indicators: 2022.

If FDI can enhance living standards, it may nonetheless raise disparities through higher wage dispersion within the foreign firm and between foreign and domestic firms. In general, inequality between firms accounts for a sizeable share of the levels in overall wage inequality. Recent work shows that wage premia due to productivity-related rents is an increasingly important driver of between-firm inequality, even more than differences in workers’ characteristics, such as skills or gender (Criscuolo et al., 2020[18]). This is relevant in a context where some MNEs are viewed as “superstar” or “winner-takes-most” firms with large market rents. FDI is likely to have a smaller impact on wage inequality in countries or regions with better absorptive capacity, including more adequate skills (Wu and Hsu, 2012[23]; Lin, Kim and Wu, 2013[24]).

3.2.3. FDI can improve non-wage working conditions but not in all sectors or value chains

Job quality also covers non-wage working conditions, including job security, occupational health and safety at work and core labour standards. Foreign and domestic firms may have differentiated impacts on these working conditions but, as for the foreign wage premium, differences often reflect firm- or industry-specific characteristics and are not specific to the ownership status. Foreign and domestic firms could be active in different sectors where companies have different survival rates, worker turnover rates, or propensities to use temporary contracts. Yet, other working conditions are shaped by foreign firms’ intrinsic characteristics, such as more advanced management practices than in domestic firms, and good management can lead to higher job satisfaction and better health (Bloom and Van Reenen, 2016[25]). FDI effects on working conditions might also be contingent on foreign firms exporting their home country labour practices, and diffusing them to domestic firms, or responding instead to the host country’s standards. Overall, there is little evidence that MNEs transmit their working conditions abroad (Almond and Ferner, 2007[26]).

Evidence on FDI impacts on job security is mixed. The FDI Qualities Indicators suggest that FDI is associated with lower job security. This could be due to the ability of MNEs to rapidly move activities across borders in response to wage movements or changes in regulations (Cuñat and Melitz, 2012[27]). The observed relationship could also reflect foreign firms’ concentration in sectors with more exposure to trade fluctuations, or in areas with more flexible labour rules, such as in some special economic zones. Other findings show that, in the case of Sub-Saharan Africa, foreign firms provide more secure jobs, but not in countries with better governance and social policies (Blanas, Seric and Viegelahn, 2019[19]). The wider empirical literature examining these aspects does not provide a clear-cut response, however (Bernard and Sjoholm, 2005[28]; Bernard and Bradford Jensen, 2007[29]; Hijzen et al., 2013[30]; Javorcik, 2015[31]). There is also no evidence that foreign firms compensate workers for increased job insecurity or more difficult working conditions by paying higher wages (Hijzen et al., 2013[12]; OECD, 2017[32]).

There is a dearth of evidence relating FDI to occupational health and safety at work. Some studies suggest a positive correlation between fewer job accidents rates and FDI (Alsan, Bloom and Canning, 2006[33]) or find a negative effect of FDI on population health (Herzer and Nunnenkamp, 2012[34]). The FDI Qualities Indicators show that greenfield FDI tends to be concentrated in activities with higher risks of occupational injury, including in OECD countries, such as in manufacturing or infrastructure. During the COVID‑19 pandemic, foreign firms managed better and faster than domestic business to adapt their modus operandi to the new work reality by ramping-up teleworking, potentially reducing workers’ exposure to COVID‑19 (OECD, 2020[1]). Fewer workers can telework in poorer economies, however – more skilled workers have higher odds to work remotely. MNEs could accelerate the adoption of new forms of work in host countries through competition and imitation effects, labour mobility, and relationships with their suppliers or buyers.

Evidence indicates that inward FDI and core labour standards, which cover the freedom of association, the abolition of forced and child labour and the eliminations of discriminations at work, are positively correlated, but not in all sectors (Kucera, 2002[35]; OECD, 2008[20]; Blanton and Blanton, 2012[36]). MNEs may shy away from investing in countries with low labour standards because of reputational risks and to fulfil international standards on responsible business conduct or core labour rights, sometimes adopted in home country regulations. This however does not say whether, once they are operating, foreign firms help improve working conditions, including in their relationships with local suppliers and buyers. Furthermore, while the positive relationship between FDI and core labour standards holds at the aggregate level, there are significant variation among sectors – mining, oil and gas and services may be important exceptions (Blanton and Blanton, 2012[36]). FDI mode of entry also matters. One study finds that M&As tend to have minimal, or slightly negative, effects on labour rights, whereas joint ventures and greenfield FDI can improve workers’ rights. The sectors and motivations associated with the two modes of entry increase more labour demand, improving the bargaining power of workers (Biglaiser and Lee, 2019[37]).

FDI impacts on non-wage working conditions may also be increasingly affected by trends in digitalisation, which are themselves accelerated by cross-border investment. New business models are emerging, including the platform economy, in which self-employed workers provide services through online platforms often owned by foreign firms. These flexible working arrangements have created new jobs but also raised concerns about job security, poor working conditions and a weak bargaining position vis-à-vis platform firms (OECD, 2019[38]). Work through platforms is still a limited phenomenon in both developed and developing countries, and the exact impact of FDI on related working conditions is yet to be explored.

Another way FDI can affect job quality is through impacts on informal employment. In the absence of labour rights or social security, informal workers have more precarious working arrangements and worst working conditions. The evidence is clear that jobs in foreign firms are largely formal, but the wider effects of FDI on employment formalisation are less obvious. Transition to formal employment is often faster in countries with higher economic growth and exposure to global markets, including through higher FDI (La Porta and Shleifer, 2014[39]; McCaig and Pavcnik, 2015[40]). Evidence from Mexico, Turkey or Viet Nam shows that FDI leads to higher levels of formal employment, although this impact is not systematic across regions and sectors (Escobar and Dougherty, 2013[41]; Cao, 2020[42]; Steenbergen and Tran, 2020[16]). Other evidence suggest that FDI leads to higher demand for informal labour through increased outsourcing from foreign to non-formal firms (Beladi, Dutta and Kar, 2016[43]). MNEs are increasingly seeking to enforce compliance with labour standards in their supply chain relationships, however, which can lead to less sourcing from informal firms (Narula, 2019[44]). Overall, FDI positive spillovers are relatively weak in the informal sector as informal firms are mired in low productivity, with limited absorptive capacity (Narula, 2020[45]).

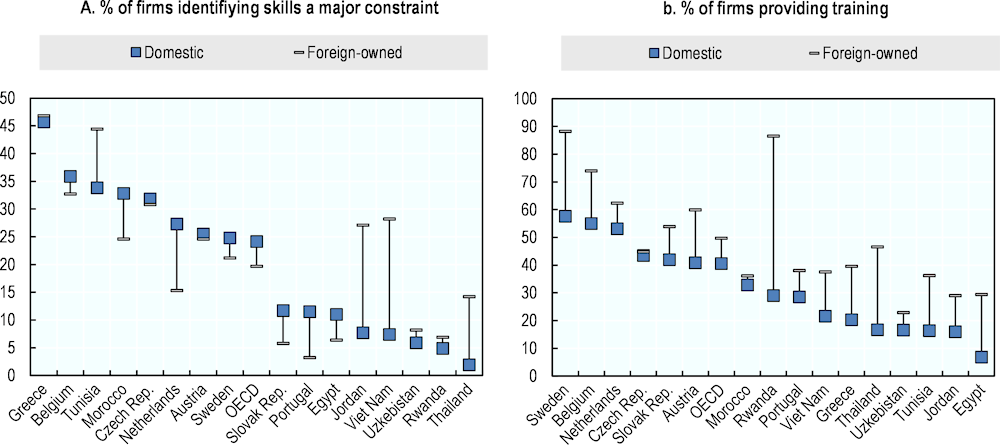

3.2.4. FDI increases the demand for and supply of skilled workers but labour market adjustments can be costly

Foreign firms – especially from more advanced economies – often bring new technologies that require complementary skills. If, as a result, skilled employment increases more than unskilled employment, the share of skilled workers in the host country will also grow. Many studies have shown that FDI raises the demand for skilled workers. The most salient example is Mexico’s maquiladoras where FDI has accounted for over 50% of the increase in the skilled labour wage share that occurred in the late 1980s (Feenstra and Hanson, 1997[46]). Other studies have confirmed since then that FDI has led to an increase in the demand for skilled labour (Bandick and Karpaty, 2011[47]; Peluffo, 2014[48]).

That foreign firms raise the demand for skilled-labour in a specific industry does not necessarily imply they operate in high-skilled sectors of the host economy. The FDI Qualities Indicators show that FDI tends to be concentrated in sectors with lower shares of skilled workers in countries with competitive wages and labour-intensive manufacturing activities (OECD, 2019[2]). FDI could also affect the demand for specific tasks that parent companies want to offshore (Autor, Levy and Murnane, 2003[49]). For instance, routine tasks can be more easily offshored, thus explaining why foreign affiliates in developing countries may be less skill-intensive than their parent company (but not necessarily less than domestic firms in the same industry). Foreign investors can also increase the supply of skills by providing training to their employees or to those of domestic companies as part of support activities (Crespo and Fontoura, 2007[50]). They may also induce local firms to invest in upskilling in response to rising competitive pressure from their presence in the market (competition effects) or to imitate more profitable foreign firms’ practices (imitation effects), including by training workers (Blomström and Kokko, 2002[51]).

Through impact on the demand and supply of skilled labour, FDI can enlarge the share of skilled workers in the host country, which, in turn, creates a virtuous circle as new investors will select the location for their knowledge‑intensive projects. Ultimately, FDI impacts on skill development will depend on how fast the supply side can respond to increased demand for skilled labour. When skill shortages exist in a region or industry, labour market adjustments from an unskilled to a skilled labour force can be lengthy and costly (Hale and Xu, 2020[22]). In that case, foreign entrants will offer much higher wages to attract available talent, thus exacerbating wage disparities and crowding out employment in domestic firms, without raising the share of skilled workers in the host economy, at least in the short term. This illustrates the importance of addressing skill shortages and promoting labour mobility across regions and industries as ways to reap the benefits of FDI for skills while mitigating adverse distributional impacts (Becker et al., 2020[52]).

3.3. Policies that influence FDI impacts on job quality and skills

Policies that are conducive to investment in general influence FDI entering the host country and its labour market implications (OECD, 2015[53]). They are, however, not sufficient to act on the different – direct and indirect – transmission channels of FDI impacts on job quality and skills development. Beyond a conducive investment climate, policy makers must ensure that institutions, strategies and policies that are at the intersection of investment, labour and skills development create the conditions to improve FDI impacts while mitigating potential adverse effects (Table 3.1). These include product and labour market regulations that are adapted to foreign firms’ entry and operations. But flexibility is not sufficient to deliver quality jobs and should be combined with measures that address specific market failures resulting from information failures or externalities resulting from FDI. Such interventions can cushion or amplify the spillover effects of foreign firms on the labour market, including distributional effects. Beyond measures implemented at national level, policy makers need to promote internationally agreed principles and conventions that can help ensure, inter alia, high labour standards in the operations of foreign firms.

Table 3.1. Policy instruments influencing the impact of FDI on job quality and skills development

|

Principle 1: Provide strategic directions and ensure policy coordination and coherence on investment, labour and skills development |

Governance |

Oversight and coordination bodies |

|

Public-private and social dialogues |

||

|

Labour market information and skills needs assessments |

||

|

Principle 2: Ensure that regulations support investment and labour market adjustments while safeguarding quality jobs and protecting the most vulnerable |

Domestic regulations |

Product market regulations |

|

Labour market regulations and standards |

||

|

Collective bargaining rights and workers’ voice |

||

|

Principle 3: Adhere to and promote internationally-agreed principles that can help ensure high labour standards in the operations of foreign companies |

International agreements & standards |

Labour provisions in investment and trade agreements |

|

Adherence to OECD Guidelines on MNEs |

||

|

Global framework agreements |

||

|

Principle 4: Stimulate labour demand and develop workers’ skills through targeted investment and active labour market policies and programmes |

Financial support |

Corporate tax relief in targeted sectors or regions |

|

Corporate tax relief against job or training commitment |

||

|

Employment, wage or training subsidies |

||

|

Technical Support |

Targeted training programmes, including for suppliers |

|

|

Training and skills development services (e.g. VET) |

||

|

Principle 5: Align investment opportunities with labour market needs and skills base byaddressing information failures and administrative barriers |

Information & facilitation services |

Job search services |

|

Investment promotion and facilitation |

||

|

Corporate disclosure on labour standards |

||

|

Social support services (e.g. transport) |

||

|

Public awareness campaigns |

The majority of policies do not explicitly target foreign firms, but they are particularly relevant to ensure that FDI has positive impacts on labour market outcomes. Indeed, the contribution of foreign firms to job quality and skills development is often linked to their performance, an aspect that does not justify developing specific policies for them. Nonetheless, the extent to which foreign and domestic firms react to the same policy setting can vary, together with their respective labour market outcomes. For instance, MNEs can choose to move production across subsidiaries following a policy change in one host country, an option that domestic firms do not have. Policymaking should take into consideration these differentiated impacts on foreign and domestic business, including through policy co‑ordination. Policies considered in this Policy Toolkit build and expand on Chapter 8 “Developing human resources for investment” of the OECD Policy Framework for Investment (Box 3.2). Annex Table 3.A.2 provides detailed questions for governments to self-assess policies influencing the impacts of FDI on job quality and skills development.

Box 3.2. OECD Policy Framework for Investment: Core questions and principles for developing human resources for investment

1. Has the government established a coherent and comprehensive human resource development policy framework consistent with its broader development and investment strategy and its implementation capacity?

2. Is there an effective system for tackling discrimination that affects labour market outcomes?

3. What steps has the government taken to increase participation in basic schooling and to improve the quality of instruction so as to leverage human resource assets to attract and to seize investment opportunities?

4. Is the economic incentive sufficient to encourage individuals to invest in higher education and life‑long learning, supporting improvements in the investment environment through a more qualified skill base?

5. To what extent does the government promote effective training programmes, including through involving the private sector?

6. Does the government have an affordable, effective and efficient overall health system?

7. What mechanisms are being put in place to promote and enforce core labour standards?

8. To what extent do labour market regulations support job creation and the government’s investment attraction strategy?

9. How does the government assist large‑scale labour adjustments? What role is business encouraged to play in easing the transition costs associated with labour adjustment?

10. What steps are being taken to ensure that labour market regulations support an adaptable workforce and maintain the ability of firms to modify their operations and investment planning?

11. To what extent does the government allow companies to recruit workers from abroad when they are unable to obtain the skills needed from the domestic labour market?

Source:OECD (2015[53]), Policy Framework for Investment, 2015 Edition, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264208667-en

3.3.1. Provide strategic direction and ensure policy co‑ordination and coherence on investment, labour and skills development

FDI that contributes to inclusive labour market outcomes can hardly be achieved through fragmented and isolated policy design, delivery and evaluation. Governments, together with the private sector and social partners, should articulate a clear vision on the contribution of FDI to job quality and skills by ensuring that national strategies provide coherent and interrelated directions on investment, employment and skills development objectives. It is equally important to strengthen co‑ordination mechanisms – or establish them if inexistent – that can effectively support social dialogue and collective solutions to emerging labour market issues driven by FDI. Inter-agency collaboration can also improve data collection efforts to better monitor the impact of FDI and help inform the policy design and evaluation. In particular, involving investment bodies in skill needs assessments can help better anticipate future needs and adapt policies accordingly.

National strategies and plans can provide coherent and strategic directions by integrating investment considerations in employment and skills strategies and vice versa

Governments usually have no dedicated strategy relating FDI to job quality and skills, but most, if not all, set priorities and goals on investment, employment and skills development in various strategies and plans. Multi-year national development or growth plans provide overarching directions in a wide range of policy areas and, if well-articulated, a coherent vision to ensure that initiatives and reforms in one area (e.g. investment) support – or do not jeopardise – strategic goals in other areas (e.g. employment). Cross-cutting strategies can also steer policy action towards developing priority activities or value chains that are aligned with the country’s aspirations and labour market realities. These national priorities, goals and policies ultimately affect the FDI transmission channels – the ways in which foreign firms have a direct and indirect impact on labour market outcomes – even when they are not strictly related to investment.

Coherent national development or growth plans also ensure alignment of objectives across specific strategies on investment, employment and skills development. In practice, this entails integrating investment considerations in, inter alia, employment and skills strategies and vice versa. This is the case of Rwanda, for instance, where the 2019 National Employment Strategy includes specific goals on investment, such as to support investment with strong linkages in labour-intensive sectors (Table 3.2). The strategy clarifies responsibilities across a wide range of institutions, going well beyond the Ministry of Labour, and provides an estimated budget for each goal. Similarly, the 2011‑20 Jordan National Employment Strategy identifies FDI as a key driver of growth and delivers a diagnosis on its impact, indicating that FDI created mostly short-term job opportunities, often in the construction sector, with few long-term effects (OECD, 2022[54]). The strategy provides policy directions on investment, such as to align tax incentives to investors with the country’s ambition of becoming a knowledge‑based economy.

Table 3.2. Rwanda’s 2019 National Employment Strategy includes specific actions on investment

Strategic goal: extend, prioritise and incentivise investment with strong linkages in employment-intensive sectors

|

Major Policy Actions |

Lead implementing institution |

Other implementing institutions |

|---|---|---|

|

Place emphasis on choosing employment-intensive technologies |

Ministry of Trade and Industry |

Private Sector Federation; Rwanda Development Board |

|

Consider the impact of investment on the number and quality of jobs created |

Rwanda Development Board |

Ministry of Trade and Industry; Private Sector Federation |

|

Carry out comprehensive employment impact assessment of infrastructure investment |

Ministry of Infrastructure |

Rwanda Development Board; Private Sector Federation |

|

Link incentive structures for FDI to the number and quality of jobs created and skills upgrading of local labour force |

Ministry of Trade and Industry |

Rwanda Development Board; Private Sector Federation |

|

Target policy incentives to employment-intensive sectors and the participation of the poor in high-growth sectors |

Ministry of Trade and Industry |

Rwanda Development Board; Private Sector Federation |

Source: OECD based on Rwanda’s Revised 2019 National Employment Policy.

It is equally relevant to incorporate the labour market and skills dimensions into the country’s investment strategy, and in a way that is adapted to the format of such documents. Some countries have comprehensive strategies that outline the government’s objectives and reform plans to foster investment and the roles and responsibilities of all relevant government bodies. Such strategies could provide clear policy directions on labour market reforms adapted to investors’ entry and operations or on promoting high labour standards through international investment and trade agreements. Most investment strategies are narrower in scope and set the government’s FDI attraction targets (e.g. sectors), tools (e.g. fairs, tax incentives, aftercare services) and performance indicators (e.g. average wages in foreign firms). They are increasingly taking into consideration quality jobs and skills as outcomes of FDI (OECD, 2020[55]). For instance, the development of Ireland’s 2021‑24 investment promotion strategy was informed by Future Jobs Ireland, which itself seeks to address challenges and opportunities for FDI arising from changing skills demand. FDI that support upskilling is a new focus of the strategy and is addressed through various initiatives to promote investments in training.

Co‑ordination bodies with clear mandates and inclusive public-private and social dialogue support policy delivery at the intersection of investment, employment and skills

The formulation and implementation of strategic objectives at the intersection of investment, employment and skills development are complex, and do not fit neatly within a single governmental department or agency. They require the involvement of several ministries, implementing agencies, social partners, and the private sector, including the foreign firms themselves. Given the multitude of actors with different interests, achieving a consensus between a broad range of stakeholders within and outside government is difficult. It is therefore important that responsibilities are balanced, explicit, sufficiently funded, and mutually understood by all actors. It is also crucial to establish, both at strategic and implementing levels, appropriate co‑ordinating bodies with clear mandates or to adapt the governance structure of existing bodies, such as boards of investment promotion agencies or skills councils, to be more inclusive and support collaborative decision-making, while managing the risk of undue influence from special interests.

In most countries, mandates over investment are separated from employment and skills, which are themselves scattered across various ministries and agencies – yet they are reasonably more integrated than with investment. Mandates are often enshrined in law or spelled-out in national strategies that often also define governance relationships with other bodies. Labour market ministries and agencies often set the country’s labour policy, regulate industrial relations and provide public employment services to individuals. The governance of skills systems entails more collaboration across government departments, including investment bodies. Education ministries and agencies are often in charge of policies related to skills development, whereas labour market ministries and agencies devise policies that maximise the effective use of skills by promoting further training opportunities and labour market activation measures. Ministries of finance are responsible for ensuring that the resources exist and for aligning financial incentives to maximise the effectiveness of employment and skills policies (OECD, 2020[56]).1

Bodies mandated with investment policy often include departments in the ministry of economy or industry and investment promotion agencies (IPAs). They can play a key role by developing and promoting policies for regional, sectoral or broad economic development, in which employment and skills occupy a central place. Thus, while investment bodies may not be directly involved in employment or skills policies, they still actively shape impacts of FDI by promoting and facilitating investment in specific job-creating or skill-intensive sectors, granting tax incentives to firms investing in regions with low employment rates or influencing wider reforms through policy advocacy actions. Investment bodies can also be responsible of raising investors’ awareness of labour and other sustainability standards. It is important to align allocated budgets with such responsibilities to ensure effective implementation.

The extent to which investment, employment and skills mandates can be integrated – or overlapping if not well-defined – depends on national context and is most likely greater in countries that receive significant FDI. In Rwanda’s 2019 National Employment Strategy, the Ministry of Trade and Industry and the Rwanda Development Board, the country’s IPA, are assigned specific actions to improve the FDI contribution to job quality and skills (Table 3.2). In fact, one mandate of Rwanda’s IPA is to align skills development with labour market demands, including by co‑ordinating and funding training opportunities (Box 3.3). Likewise, the Costa Rican or Thai IPAs have widened their mandates to also support skills development (OECD, 2021[57]). These cases are likely to be the exception rather than the norm, however, and they are not necessarily governance models for other countries with different contexts and priorities. But they illustrate how mandates can be partly integrated to leverage FDI for more inclusive labour markets, as long as responsibilities are clear, mutually understood by all and grounded in sound and coherent strategies.

Box 3.3. Promoting FDI, employment and skills under one umbrella agency: The case of Rwanda

Rwanda Development Board (RDB) is a government institution whose mandate is to accelerate Rwanda’s economic development by enabling private sector growth. It is principally responsible for promoting domestic and foreign investments, but other key services include skills development and improving workers’ employability.

The 2019 National Employment Strategy indicates that while promoting exports to regional and international markets of goods and services, the opportunities for labour mobility should also be given much consideration by RDB. In its mandate to provide guidelines, analyse project proposals and follow up on the implementation of Government decisions in line with public and private investment, RDB should mainstream employment opportunities in project proposals.

RDB vision is skilling Rwanda for economic transformation. The Chief Skills Office was established under the RDB in 2018 to align skills development with labour market demands. The Chief Skills Office, together with key stakeholders in the skills development and employment promotion ecosystem, developed the National Skills Development and Employment Promotion Strategy (NSDEPS).

The Chief Skills Office is composed of two departments: the strategic development capacity department and the targeted labour market interventions department. It is mandated to provide effective oversight and co‑ordination in the skills development and employment promotion ecosystem. Goals include promoting and co‑ordinating sector skills, capacity development strategies and actions to respond to private sector needs; conducting labour market analysis to identify current and future skills needs in priority sectors and for key investment projects; and facilitating labour market integration through innovative partnerships and interventions.

Source: OECD based on https://rdb.rw/.

Effective horizontal co‑ordination also can help achieve a better alignment across investment, employment and skills policies. In general, governments have no committees (or similar structures) exclusively dedicated to co‑ordination between ministries, agencies and social partners dealing with labour and skills development and those responsible for investment. If they are to be created, such inter-governmental committees need clear and strong internal governance structures, and decision-making processes should be agreed on to maximise the commitment and involvement of all stakeholders, including technical agencies, the private sector, social partners, and specific groups that are of potential relevance such as youth representations. Establishing such dedicated committees may not be necessary, however, and could be even counter-productive, if other, narrower, co‑ordinating mechanisms that already exist could be realistically adapted to help ensure some alignment across investment, employment and skills policies.

On the investment side, existing co‑ordinating committees such as boards of IPAs could consider involving the labour and skills communities to help them voice their concerns with regards to FDI, better co‑ordinate on specific measures and build consensus around future reforms that are of relevance to them (e.g. to introduce tax incentives for firms that provide training). In Jordan, for instance, the Minister of Labour sits in the Investment Council, a high-level co‑ordinating body headed by the Prime Minister that sets the country’s investment strategy and oversees the work of the IPA (OECD, 2022[54]). In general, the presence of representatives from the labour or skills communities is not widespread across IPAs’ boards (or similar structures). The status of such boards and the breadth of their co‑ordinating role can strongly vary across agencies (OECD, 2018[58]). In many countries, boards of IPAs have solely an advisory role that is confined to investment promotion and facilitation activities.

It is equally relevant to envisage including representatives of investment bodies in committees co‑ordinating employment or skills policies. They can, for instance, provide feedback on labour market reforms under discussion or voice the concerns of foreign investors in terms of training needs. In Ireland, the National Skills Council provides advice on skills needs and secures delivery of the identified needs, as well as bringing together a wide range of actors, including the CEO of IDA Ireland, the Irish IPA. The CEO is charged with providing regular updates on sectoral opportunities and potential target areas for increased FDI and advice on issues associated with the availability of skills to support employment. Respectively, the 2021‑24 investment promotion strategy indicates that the IPA will collaborate with the Department of Education and Skills, the National Skills Council, or the Expert Group on Future Skills Needs.

FDI can be a forward-looking indicator of what jobs and skills will be in demand in the future and could therefore be integrated into skills anticipation systems

FDI is a key driver of GVCs and technological changes (e.g. automation and digitalisation) that influence the kind of jobs that are available, the skills needed to perform them and related working conditions (e.g. new working arrangements on teleworking). The costs and benefits of these megatrends are complex and increase the uncertainty surrounding the future of work. In this context, it is of paramount importance to build responsive skill assessment and anticipation systems that enable countries to react to changing labour market and skills demands (OECD, 2019[6]). FDI decisions can constitute a forward-looking indicator of what jobs and skills will be in demand in the near future, rather than trade flows that reflect past investment decisions (Hallward-Driemeier and Nayyar, 2019[59]). Collecting information on foreign firms’ operations and skills needs will help governments developing adequate policies, such as training programmes, that can prevent skills mismatches and shortages as well as reduce retraining costs. For instance, ILO’s “Skills for Trade and Economic Diversification” guide recommends disaggregating data between foreign and domestic businesses when FDI accounts for a significant part of a sector.

Many countries have put in place labour market information systems and tools for assessing and anticipating skills needs, but limited co‑ordination between stakeholders is often a barrier preventing the information from being used further in policy making (OECD, 2016[60]). Ministries of Labour and Education, the statistical offices and employer organisations are the actors most frequently involved in skills assessment and foresight exercises. Involving the investment community, including the IPA and the foreign firms, in such foresight exercises could help reduce the gap between the information produced and the skills needs driven by FDI. IPAs have often access to unique information on MNEs’ operations and run surveys to identify their challenges and skills needs (OECD, 2018[61]). Furthermore, IPAs are increasingly tracking FDI impact by setting key performance indicators (KPIs), including on employment, wages and skills (Sztajerowska and Martincus, 2021[62]). Such data could be shared or even automatically connected to skills assessment and anticipation systems to ensure that policy responses are timely, coherent and well-targeted.

3.3.2. Ensure that regulations support investment and labour market adjustments that create good job opportunities for all and are adapted to a changing world of work

Product and labour market regulations affect FDI location choice, characteristics and, in turn, labour market impacts. They also affect how labour markets adjust in response to FDI entry and spillovers – impact is likely to be greater in settings with more efficient resource reallocation. Solid collective bargaining institutions and high labour standards are however fundamental to ensure that FDI creates opportunities for all. Regulations also include internationally agreed principles that can be instigated by governments, such as by joining international conventions or including labour provisions in investment agreements. They can also consist of non-binding recommendations addressed directly to business, such as the OECD Guidelines for MNEs, or agreements between MNEs and global union federations to ensure common labour standards across an MNE global operation.

Openness to foreign investment and wider pro-competition policies can help ensure that expected labour market gains from FDI materialise and are fairly shared

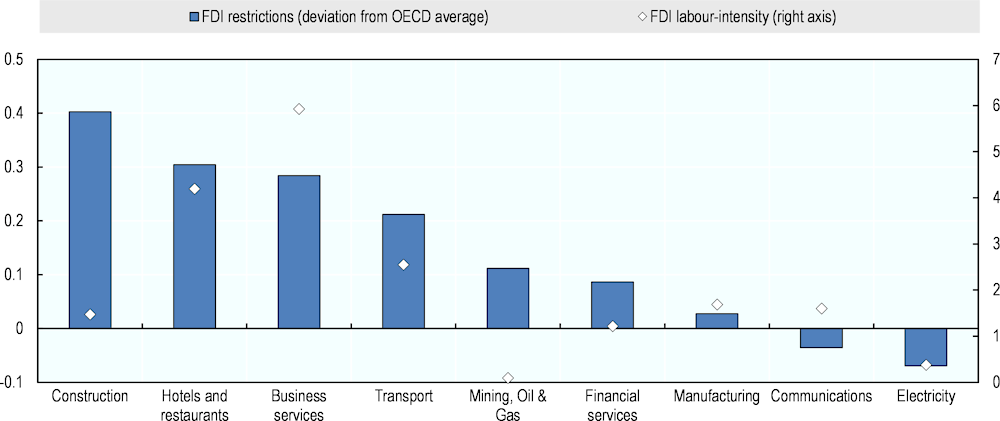

Governments should periodically assess existing regulatory restrictions on FDI against evolving public policy objectives on job quality and skills development and, where relevant, consider streamlining or removing them. Discriminatory measures on foreign investors’ entry and operations deter FDI and, in turn, potential labour market gains from higher investment. Forgone FDI benefits hinge on the labour or skill-intensity of restricted sectors as well as their propensity to increase labour supply – increased investment in higher education could support the growth of a skilled workforce. The type of discriminatory measure also matters. Joint venture requirements may push foreign investors to limit skills transfers while restrictions on the employment of foreign personnel in key management positions may limit the diffusion of managerial expertise (Moran, Graham and Blomström, 2005[63]). In Jordan, for instance, restrictions on full foreign ownership exist in business services, transport and tourism, while greenfield FDI has a strong job creation potential in these sectors, including for the many unemployed young graduates (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4. FDI regulatory restrictions and job-creating potential of greenfield FDI in Jordan

Source: OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index and Financial Times fDi Markets; OECD (2022[54]), FDI Qualities Review of Jordan: Strengthening sustainable investment, https://doi.org/10.1787/736c77d2-en.

Governments often introduce FDI restrictions with the stated objective of protecting domestic firms (and their workers) from foreign competition or to ensure that FDI generates high development benefits, for instance when investor entry is conditional on mandatory job creation requirements. But these policies may not be optimal for tackling such concerns as they create uncertainty and negatively influence foreign investors’ decisions (Mistura and Roulet, 2019[64]). By limiting competitive pressures, FDI restrictions also deter innovation and potential learning opportunities by domestic competitors, and related productivity spillovers that can help them retain their workers in better-paid jobs (Chapter 2). It is therefore essential to involve labour market bodies and social partners when assessing the costs and benefits of FDI restrictions as it can help promote collective solutions and build consensus around meaningful liberalisation reforms.

Whether openness leads to positive impacts of FDI on labour market outcomes also depends on the time horizon. For instance, liberalisation can crowd out domestic competitors and increase wage inequality in the short term, particularly in non-tradable services where foreign firms are more likely to capture market shares such as in the construction sector. Indeed, FDI in services is often associated with the largest increases in wage inequality because lower-skilled workers can be displaced in favour of higher-skilled workers. In the longer term, services liberalisation improves productivity in other sectors and can generate significant labour market gains, although not necessarily for all segments of the labour force. Governments could prioritise the tradable services sectors with solid comparative advantages to limit the transitory labour market losses from liberalising other services FDI (Steenbergen and Tran, 2020[16]).

Together with FDI restrictions, other regulations affect the degree of product market competition, including state control of business enterprises and barriers to trade, innovation and entrepreneurship. Product market competition can reduce foreign firms’ entry and operation costs, increase their productivity and, in turn, job-creating potential (Fiori et al., 2012[65]; Gal and Theising, 2015[66]). For instance, research on the role of product market regulations for the employment dynamics of entering and incumbent firms suggests that, in sectors that are more risky or financially dependent, more stringent product market regulation is negatively associated with the net job contribution of firms (Calvino, Criscuolo and Menon, 2016[67]).

Pro-competitive product market reforms and competition policy enforcement can also help achieve fairer sharing of productivity gains by foreign firms. As restrictions on FDI decrease, countries need to adopt and enforce sound measures to control anti-competitive practices (OECD, 2018[68]). Enhanced competition can help reduce rents of firms active in highly concentrated markets, and to share more fairly these gains with workers. In particular, strengthened competition could contain rents in “superstar” or “winner-take‑most” MNEs operating in markets with high mark-ups and low labour shares (e.g. ICT services) because of large product market concentration (Autor et al., 2020[69]; Criscuolo et al., 2020[70]).

The impact of product market reforms on FDI and related labour market outcomes also depends on host country labour market regulations. For instance, when workers’ bargaining power is high, possibly because of more stringent employment protection legislation, and the economy is far from full employment, a decline in firms’ mark-up due to product market reforms can lead to larger employment increases than in a context with more flexible labour markets (Fiori et al., 2012[65]). The intuition behind is that, with less flexible labour markets, employment will be further away from its full employment level. This example shows that policy makers should take into consideration product and labour policy interactions when collectively thinking about ways to introduce reforms that can positively affect FDI impacts on labour market outcomes.

Balanced labour market regulations can support foreign firms’ adjustments while providing a level of employment stability that encourages learning in the workplace

Stringent employment protection can increase firms’ labour adjustment costs but also improves job quality. Greater flexibility of the host country’s labour market matters for the location choice of investors and affects FDI volumes – and thus job creation – as well as their skill intensity. For instance, stringent legislation can deter FDI in the services sector more than in manufacturing (Javorcik and Spatareanu, 2005[71]). It may also dissuade R&D firms from locating their core innovation projects, as these need drastic employment adjustment because many workers with new skills are needed (Griffith and Macartney, 2014[72]). Impact can differ across contracts and, for instance, stringent legislation on regular contracts may affect FDI-related employment more adversely than rules on temporary work (Gross and Ryan, 2008[73]). At the same time, job security protects workers from being fired in response to small business fluctuations, encourages them to invest in long-term training and is often associated with better (mental) health (OECD, 2018[5]).

Once established, foreign firms do not appear to be more constrained by labour regulations than domestic firms, although they can be in some countries – including those with high FDI stocks (Figure 3.5). Employment protection legislation may matter less for foreign firms that can move production across subsidiaries located in different countries or that are attracted by markets with low production costs (Leibrecht and Scharler, 2009[74]; Cuñat and Melitz, 2012[27]). These firms may be able to bargain from a privileged position with host governments and unions, thus obtaining exceptions on hiring and firing practices (Navaretti, Checchi and Turrini, 2003[75]). Notwithstanding the additional leeway MNEs may have over domestic companies, their divestment decisions might still be affected by regulations such as those on collective dismissals – which often cover large firms – particularly footloose large foreign firms.

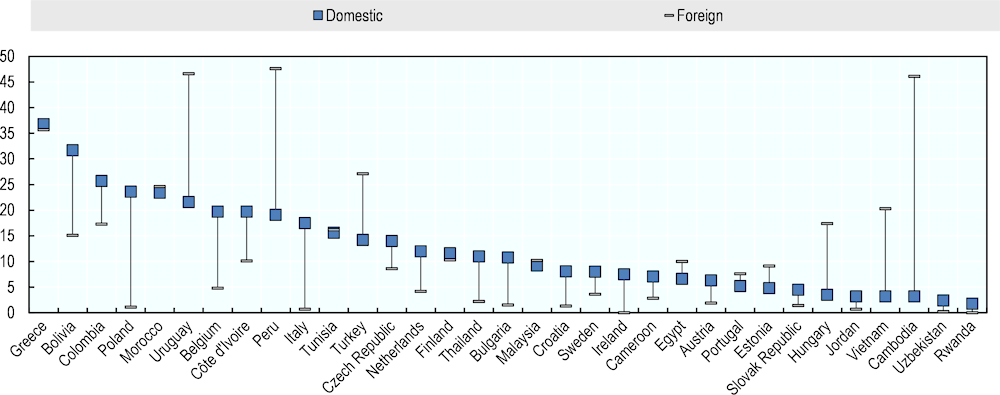

Figure 3.5. Percent of firms identifying labour regulations as a major constraint, by ownership

Note: The figure shows a group of selected OECD and non-OECD countries for which firm-level surveys were available from 2015 and beyond.

Source: OECD based on the World Bank Enterprise Surveys.

Employment protection legislation also affects how the wider labour market adjusts in response to FDI entry and spillovers. For instance, stricter employment protection can deter or delay labour mobility from domestic to foreign firms while it is typically via this channel that FDI enhances wages in host countries, at least in the short term (Hijzen et al., 2013[12]). However, it may protect vulnerable workers that otherwise would have been displaced and lose out via long unemployment spells or lower wages in post-displacement jobs, potentially in the informal economy. When local absorptive capacities are sufficiently high, i.e. when skills in demand by foreign firms are available, more flexible labour markets can host FDI without necessarily reducing employment or increasing wage disparities between foreign and domestic firms (Becker et al., 2020[52]).

Other regulations include working-time arrangements, minimum wages, occupational health and safety at work, legal guarantees of social insurance regimes or legislation on foreign workers – foreign firms tend to rely more often on foreign workers than their domestic peers do. Minimum labour standards ensure that those practiced by foreign firms are not less favourable than those by domestic firms. This helps to ensure that FDI is not worsening working conditions in the host country. Labour standards can be established through legislation, collective agreements or both. Core labour standards of the ILO aim to: 1) eliminate all forms of forced or compulsory labour; 2) effectively abolish child labour; 3) eliminate discrimination in respect of employment and occupation; and 4) ensure the freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining (see next sections). Labour market regulation must also enable companies to create formal jobs and avoid creating incentives for employers and workers alike to shift to, or remain in, the informal economy, where workers are not protected by labour laws and lack access to work-related measures of social protection. Specific strategies are needed to encourage workers to move into the formal economy and to address social protection for workers in the informal sectors (OECD, 2015[53]).

Countries may not want to raise or enforce labour standards because they fear this will deter foreign investors. But empirical evidence suggests that lowering labour standards does not facilitate, and may even discourage, FDI and might also change its composition and related societal benefits (Kucera, 2002[35]; OECD, 2008[20]). This holds equally in special economic zones, where governments should further harmonise labour standards, in particular minimum wages or restrictions to freedom of association, with those in the wider economy. Evidence shows that there is no strong link between higher formal labour standards and better actual labour practices, indicating that labour standards are not always properly enforced (OECD, 2008[20]). This is likely to reflect institutional weaknesses and insufficient resources.

When foreign firms export their home country labour standards practices, and these are higher than those of the host country, then FDI may even improve working conditions, including through imitation effects or through relationships with suppliers. There is, however, limited evidence that foreign firms export their home country labour standards. But this depends on the type of labour practice. For instance, management practices are more advanced in MNEs than in domestic firms, and good management can be a critical component of a good job. Foreign affiliates of more gender-inclusive countries also tend to have higher shares of female workers (see Chapter 4). Furthermore, foreign firms have relied significantly more than domestic firms on teleworking during the COVID‑19 pandemic (OECD, 2020[1]). With support from labour unions and employers’ associations, they could play a role in adapting themselves to new work realities, and their good practices could serve as a basis for domestic reforms that can improve labour standards.

The right to collectively bargain and workers’ representations can support better working conditions in MNEs but they must be adapted to a changing world of work

FDI – combined with trade, innovation, climate change and other factors – transforms the world of work and creates uncertainties on related labour market gains and losses. Collective bargaining systems and workers’ voice arrangements help ensure that all workers benefit from these transformations by supporting solutions to emerging issues (e.g. automation, digitalisation, teleworking, protecting biodiversity), complement policies to anticipate skills needs, or support to displaced workers in new forms of work (OECD, 2019[38]). Collective bargaining can also support a fairer sharing of productivity gains by influencing the wage formation process. This is relevant in the context of foreign firms that poorly translate productivity-related rents into wage benefits, particularly for less skilled workers with lower bargaining power (OECD, 2019[2]; Criscuolo et al., 2020[70]). Indeed, sector-level collective bargaining is associated with lower wage inequality while bargaining and workers’ representation at the firm-level can increase wages, productivity and job satisfaction (OECD, 2019[38]; Blanchflower and Bryson, 2020[76]).

Collective bargaining systems are generally based on a complex set of rules and practices, partly written in national laws and partly based on longstanding traditions. They can strongly differ across both developing and developed countries (Lamarche, 2015[77]; OECD, 2019[38]). The main aspects of collective bargaining are the level at which bargaining occurs (national or multi-sector level, sectoral level, or firm level), the coverage rate, the degree of co‑ordination between social partners and the effective enforcement of collective agreement (OECD, 2019[38]). Governments should ensure the freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining for all workers and across the country, including in free or special economic zones where foreign firms often operate. In some countries, specific sectors or geographical areas are excluded from the right to organise and bargain collectively. In some other countries, laws can prohibit union pluralism or prevent foreign workers from forming unions (OECD, 2022[54]). Governments and social partners may also want to embrace the diversity of existing and evolving models of collective bargaining and workers’ voice and consider to make collective bargaining systems more flexible and more inclusive.

A challenge for collective bargaining is to remain relevant in a globalised and rapidly changing world of work (OECD, 2019[38]). Technological and organisational changes are encouraging new forms of employment, blurring traditional categories, such as ‘employer’, ‘employee’ and ‘place of work’. Employers’ organisations, which are part of the collective bargaining system, are also being put to the test by changes to the world of work. They have an interest in ensuring a level-playing field for their members in the face of new competitors, who may circumvent existing labour regulations – for instance, digital platforms often consider themselves as matchmakers rather than employers (OECD, 2019[38]). As to FDI, existing, albeit limited, evidence indicates that foreign firms in host countries may not have sufficient incentives to join collective bargaining agreements or employers’ associations (Jirjahn, 2021[78]).

Collective bargaining coverage has declined in most OECD countries, a trend that may have been accelerated by outward FDI to countries where industrial relations and collective bargaining are weaker (OECD, 2018[68]; Duval and Loungani, 2019[79]) – the role of outsourcing in this decline is yet to be clarified and may not hold for all countries. In the absence of broad membership, one way to maintain high coverage is to extend the coverage of collective agreements beyond the signatory unions and employer organisations to all workers and firms in a sector (OECD, 2018[68]). In some countries, extensions are issued to ensure the same treatment and standards to all workers in the same sector, in particular for workers of foreign firms (Hayter and Visser, 2018[80]). Extensions may have a negative impact when the terms set in the agreement do not consider the economic situation of a majority of firms in the sector. In order to alleviate these concerns, extension requests could be subjected to reasonable representativeness criteria, in line with the ILO Recommendation on collective agreements No. 91 (OECD, 2019[38]).

It is an open question how the decentralisation of collective bargaining affects MNEs’ industrial relations. In practice, even when there is a right to collectively bargain in the host country, foreign firms’ negotiation power may still differ from that of domestic firms, possibly reflecting union fears that wage demands (or negative shocks) may lead to the relocation of production (OECD, 2008[20]). Their higher propensity to bypass collective employee representation when going abroad could adversely affect rent-sharing with workers. It may also weaken MNEs’ compliance with labour standards in GVCs. The OECD Guidelines for MNEs (OECD Guidelines) indicate that, in the context of negotiations with workers’ representatives, or while workers are exercising a right to organise, MNEs should not threaten to transfer activity to other countries in order to influence unfairly negotiations or to hinder the exercise of a right to organise (Box 3.4).

One concrete consequence of the bargaining imbalance in foreign firms at the national level has been the development of transnational workers’ representations to better co‑ordinate workers’ bargaining policies. Innovative cross-border mechanisms such as Global Framework Agreements (GFAs) have emerged to spread workers’ rights, including the right to unionise and bargain collectively, within MNEs (Helfen, Schüßler and Stevis, 2016[81]). GFAs are non-binding agreements negotiated between a MNE and global union federations. They are instruments for regulating labour conditions and employment relations within MNEs and throughout their global value chains. As such, they can help protect the interests of workers and support transnational co‑ordination of collective bargaining.

More than 300 GFAs have been signed by 2019, according to the ILO and the European Commission. In the EU, for instance, European Works Councils are consulted by MNE management on decisions at European level that affect workers’ employment or working conditions. They can be established, as per EU directives, in companies or groups of companies with at least 1 000 employees in the EU and the other countries of the European Economic Area, when there are at least 150 employees in each of two Member States. The large majority of GFAs make reference to ILO Conventions – most often to ILO fundamental Conventions, and an increasing number are also referring to the OECD Guidelines for MNEs and the ILO MNE Declaration. Furthermore, most GFAs make reference to supply chain due diligence, even if supplier companies are not parties to them (ILO, 2016[82]). Evidence suggests that GFAs do have the capacity to improve fundamental rights at work such as freedom of association and the rights to organise and bargain collectively, although this also depend on the MNE home country labour practices (Bourque, 2008[83]; Papadakis, 2011[84]; Helfen, Schüßler and Stevis, 2016[81]).