The first section of this chapter assesses sustainable investment in Jordan and derives overarching policy considerations. An analysis by areas of sustainable development (productivity and innovation, job quality and skills development, gender equality, and low-carbon transition) is provided in the second section.

FDI Qualities Review of Jordan

1. Overview and key policy considerations

Abstract

1.1. Impact of FDI on sustainable development in Jordan and overarching policy considerations

This section assesses the main challenges and opportunities in terms of sustainable development in Jordan and discusses how foreign direct investment (FDI) can support the recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis and sustainable development in the future. It then derives key considerations for institutional and policy reforms to boost FDI-led progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

1.1.1. Main challenges and opportunities for sustainable development in Jordan

Stagnant productivity growth, labour market imbalances and dependence on imported fossil fuels constrain sustainable development in Jordan

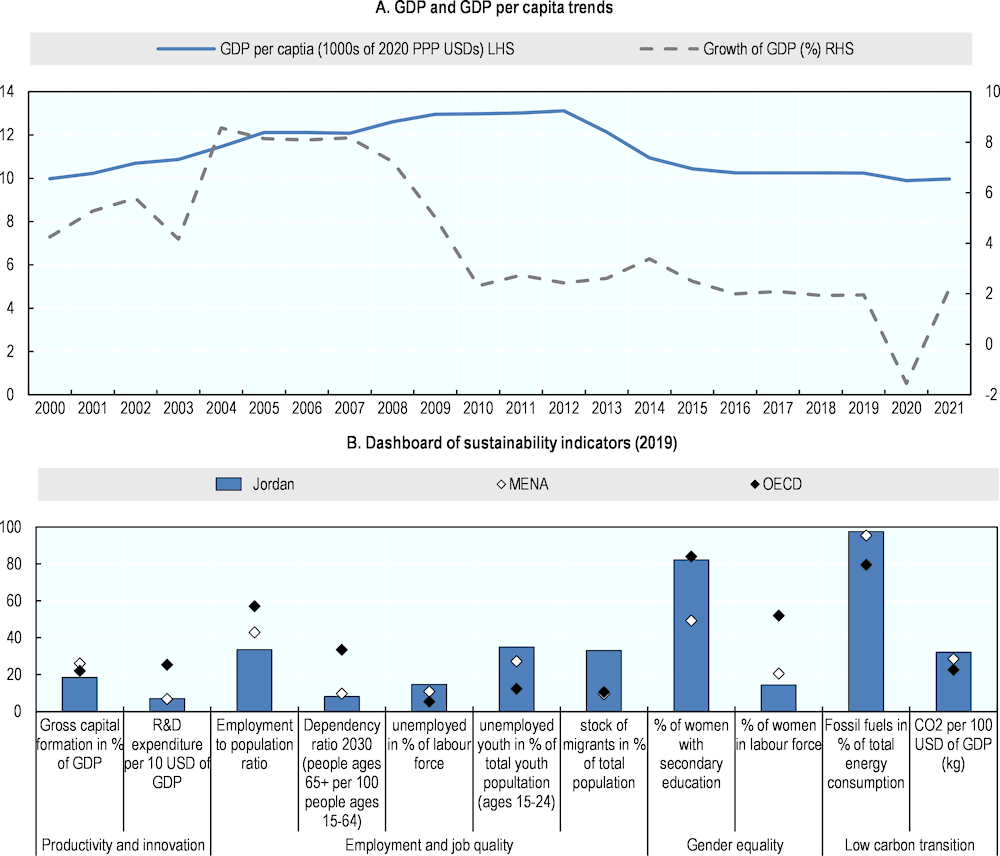

Economic development in Jordan has slowed in recent years, after witnessing a period of rapid economic growth and development in the 2000s. Annual GDP growth averaged between 4‑8% over 2000‑08 (Figure 1.1, Panel A), similar to growth rates in many peers in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) as well as other emerging regions. More than in other MENA countries, foreign direct investment (FDI) and integration into global value chains (GVCs) have enabled economic growth and productivity in Jordan. FDI inflows have mainly gone to real estate development and the energy sector (power generation) (70% of greenfield FDI) but also manufacturing such as garments, textiles and chemicals. However, Jordan’s economic development process slowed down after the global economic crisis in 2008; growth now averages around 2% per year. In addition to this slowdown, ongoing conflicts in neighbouring countries that have cut off important trade corridors led to a significant drop in demand for Jordan’s exports and a sharp increase in energy costs from imported fuels (Chapter 2). Jordan’s reduced competitiveness has also been accompanied by lower investment than in the MENA region and OECD countries and a relatively low intensity of knowledge activities such as research and development (R&D) (Figure 1.1, Panel B).

Jordan has an opportunity to reap the benefits of a young and well-educated population but more inclusive growth is challenged by various labour market imbalances. The employment rate is low compared to the average for MENA and OECD countries, with many people in informal and low-paid jobs, and many young and highly educated graduates are unemployed, particularly women (Figure 1.1, Panel B). Progress in women’s educational attainment in Jordan has not been followed by increased participation of women in the labour market. The female participation rate is among the lowest in the world, at only 14%, and the gender pay gap remains significant (Chapter 4). Insufficient job creation through private investment, combined with a growing labour force and considerable skills imbalances, are the main challenges facing the labour market in Jordan – challenges that the influx of refugees and the COVID‑19 pandemic have exacerbated (Chapter 3). The public sector is no longer absorbing a large number of new graduates, but continues to offer more attractive working conditions than the private sector, thereby limiting labour mobility. These challenges have also led to a decline in average per capita incomes since 2012; corrected for purchasing power parity, incomes have now returned to levels seen in 2000 (Figure 1.1, Panel A).

Water, food and energy security are amongst the biggest challenges to achieving sustainable development in Jordan and have serious implications for Jordan’s carbon emissions and its ability to meet its climate targets (Chapter 5). Water scarcity and high energy costs are also crucial barriers to private sector growth and productivity. Jordan is one of the world’s most water-scarce countries, and climate change is expected to exacerbate this scarcity. Jordan’s geographical conditions are such that high energy inputs are required to filter and transport water over long distances and varied terrains. Jordan’s energy sector is overwhelmingly fossil fuelled (Figure 1.1, Panel B), and has been subject to rising costs due to conflicts and political instability in the region, high dependence on energy imports and the growing demand of a larger population due to the influx of refugees. Given its natural resource endowments, Jordan has a strong potential for the development of renewable energy technologies, especially in solar and wind energy. While there is still a long way to go, Jordan has made important strides in recent years reaching its 10% renewable energy target for 2020 ahead of schedule, and is now aiming for as much as 31% of its electricity mix to come from renewable sources by 2030.

Figure 1.1. Economic and sustainability context in Jordan

Source: OECD based on The Conference Board’s Total Economy Database and World Bank (Panel A) and UNDP’s Human Development Index 2020 (Panel B). Data for 2021 are based on projections.

Boosting services can support inclusive and sustainable growth in Jordan

Reigniting exports and FDI can drive inclusive and sustainable growth in Jordan as well as support the ongoing recovery from the pandemic. Fiscal and balance of payments constraints remain a challenge. Despite fiscal adjustments, Jordan’s debt-to-GDP ratio has risen to above 90% since the 2008 crisis. Future growth cannot depend on fiscal stimulus, nor can it be expected to come from fiscal discipline. The current account deficit is already large, so growth cannot be driven by increases in private domestic demand for non-tradable goods, as these would require more imports and worsen the external balance. Jordan’s growth and productivity potential thus lies in export activities and foreign investment inflows, which will lower the current account deficit and also have a multiplier effect on the non-tradable sector.

The immediate potential for inclusive and sustainable growth lies in services activities that are neither energy- nor water-intensive. Jordan has the natural endowments to reduce the costs of electricity in the medium term through an acceleration of investments in renewable energy generation and leveraging new technologies to maintain grid stability (Chapter 5). This would also help Jordan’s green growth agenda more generally and create new opportunities for sustainably increasing water supply, which would also improve competitiveness in (energy- and water-intensive) manufacturing activities.

The potential for inclusive growth in services is supported by the growing workforce with tertiary education (Chapter 3). While the most recent change in the labour force is driven by significant inflows of refugees, Jordan’s comparative advantage in skills-intensive activities has developed over a longer period, driven by a significant increase in women’s tertiary education (Chapter 4). Traditionally, female labour was in the education, health and non-market services sectors, but further female workers cannot be absorbed by these non-tradable sectors due to fiscal constraints. Jordan should therefore boost investment and create jobs in tradable services such as ICT and other business services, transport and logistics, creative industries and tourism. Many of these services, which have already served as a driver for growth and exports over the past decade, could be further expanded in the future and, with appropriate investment, have significant potential to raise productivity from current low levels.

1.1.2. There is strong potential for FDI to contribute to a sustainable recovery in Jordan

FDI in Jordan is an important source of financing that held up during the pandemic…

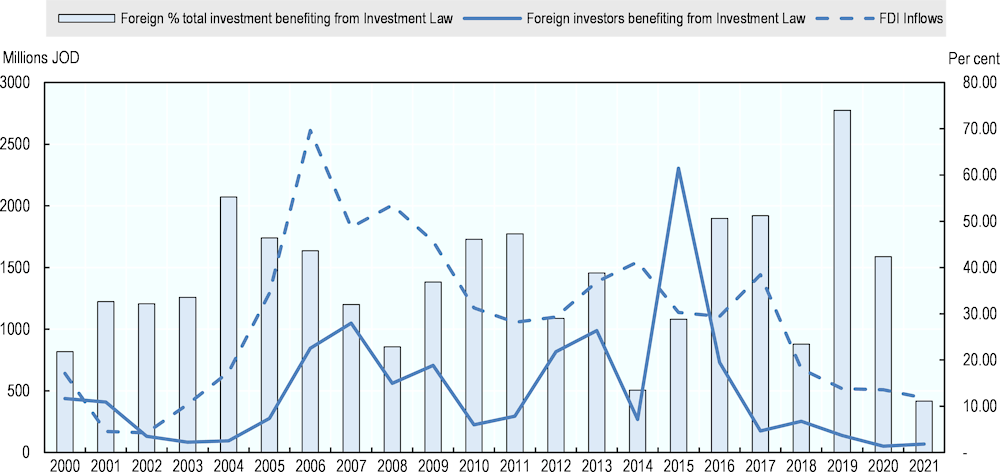

The Government of Jordan prioritises FDI as a driver of sustainable development. Ambitious liberalisation reforms in the 1990s made the Kingdom one of the most successful countries in attracting FDI – the FDI stock-to-GDP ratio exceeded 80% in 2020, which is high compared to other economies. In 2014, the government adopted a modernised investment law and launched a revamped investment promotion agency, the Jordan Investment Commission (JIC), which became the Ministry of Investment (MoI) in 2021. Projects benefitting from the Investment Law refer to firms that are registered with MoI to exercise activity in Development Zones (areas within customs) and Free Zones (areas outside of customs). These companies benefit from various tax exemptions or reductions – the Investment Law and related regulations also give incentives to some activities outside of zones, but projects are not registered through MoI. Foreign projects registered with MoI represented 50% of total inward FDI inflows between 2000 and 2020 (Box 1.1). They also accounted for 40% of all MoI-registered projects, the rest being domestic projects (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. FDI inflows and foreign investments benefiting from the 2014 Investment Law, 2000‑21

Source: OECD based on Central Bank of Jordan (official FDI inflows) and Jordan Ministry of Investment.

Box 1.1. Sources of FDI statistics in Jordan

Jordan uses a number of different data sources, as do most countries, in compiling its FDI statistics; it conducts FDI surveys, considered to be the best source of information for FDI statistics, and is currently developing a new survey in conjunction with the Department of Statistics and MoI. The Central Bank of Jordan (CBJ) is the official source of FDI statistics and it compiles FDI statistics that largely follow the international guidelines. Differences in FDI inflows as compiled by CBJ and foreign projects registered with MoI may reflect differences in data collection methodologies, possibly explaining the inconsistencies observed in 2001 and 2015. Other sources of investment statistics include the Amman Stock Exchange (ASE), where foreign companies – firms with 10% foreign ownership or more – account for 70% of ASE market capitalisation and 73% of employment by listed companies. Investment statistics compiled by the CBJ, MoI and ASE do not use the same industry classification, reducing the ability to conduct an analysis on the impacts of FDI on sustainable development. The OECD completed in 2020 an in-depth review of FDI statistics in Jordan that provides detailed recommendations, including publishing FDI position and transactions by industry. CBJ collects such FDI statistics but does not disseminate it online. Jordan could also collect and disseminate, through the Department of Statistics, in co‑operation with MoI, firm-level statistics disaggregated by business ownership, either through establishment census data or periodical surveys (or both).

Source: OECD (2020[1]), OECD Review of Foreign Direct Investment Statistics: Jordan, https://www.oecd.org/investment/OECD-Review-of-Foreign-Direct-Investment-Statistics-Jordan.pdf; Central Bank of Jordan, Jordan Investment Commission and Amman Stock Exchange.

Despite important investment climate reforms, persistent structural challenges and dependence on a few industries, combined with global shocks and regional instability, have gradually eroded Jordan’s FDI performance in the last 15 years. FDI inflows represented less than 2% of GDP in 2020 and 2021, on par with comparator groups, but much lower than the country’s average performance over the last decade (Figure 1.3Figure 1.3). Jordan’s FDI inflows held up during the first year of the COVID‑19 pandemic and increased by 4% in 2020 compared to 2019 while it dropped by 18% in the MENA region. Foreign projects benefiting from the 2014 Investment Law and registered with MoI – projects in Free or Development zones – have declined more strongly in 2020. Due to the ongoing crisis, Jordan’s FDI inflows declined by 18% in 2021.

Figure 1.3. FDI in Jordan has been declining overall but held up during the COVID‑19 pandemic

Note: MENA includes Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, the Palestinian Authority, and Tunisia. Data for 2021 is preliminary.

Source: IMF Balance of Payments database, IMF World Economic Outlook database (GDP) and OECD FDI statistics database.

… but its contribution to sustainable development has been limited

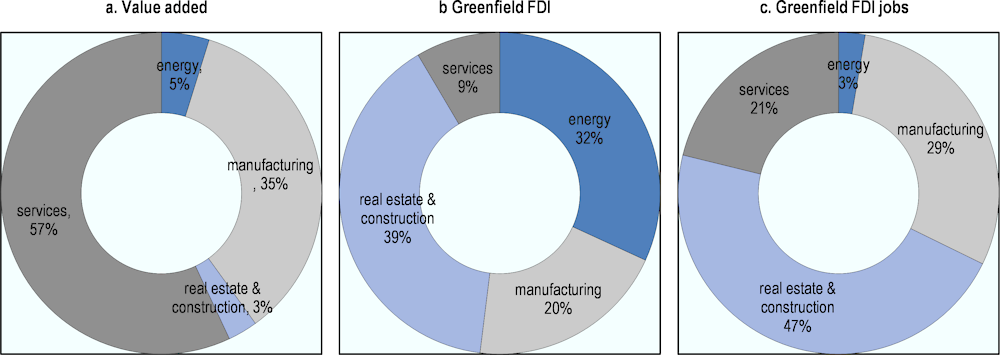

The challenge for Jordan is not only to restore and increase FDI levels, but also to enhance their alignment with the SDGs to support the recovery. Despite a large stock of FDI, Jordan has not been as successful as other economies in leveraging investment to promote sustainable development. Some of the sectors that attract the most FDI in Jordan – including real estate, construction and oil and gas-related energy – do not contribute the most to productivity and innovation, green growth or the creation of quality jobs for young women and men. While the services sector produces almost 60% of the country’s value added, it attracted less than 10% of greenfield FDI between 2003 and 2020 (Figure 1.4). Within services, the financial sector attracts most FDI – the sector accounts for 77% of total market capitalisation by foreign firms in Amman Stock Exchange (ASE) against 10% in other services. FDI in manufacturing created many jobs in the early 2000s, particularly for women, but accounted for 20% of greenfield FDI, a share that has been gradually declining in recent years, compared to 40% in most ASEAN economies (OECD, 2021[2]). Furthermore, manufacturing FDI has been concentrated in low productivity and low skill-intensity sectors, such as the garment industry, and has been responsible for large shares of oil-based fuel consumption.

Figure 1.4. Jordan has an opportunity to improve the impact of FDI on sustainable development

Note: Greenfield FDI corresponds to announced capital expenditure (CAPEX). Number of jobs and CAPEX are partly based on estimates. Greenfield FDI variables cover the period between 2003 and 2017 and national economy variables cover the period between 2013 and 2017.

Source: OECD calculation based on Financial Times fDi Markets and Jordan’s Department of Statistics.

Evolving global FDI trends and changing investment patterns in Jordan might be able to better match the country’s factor endowments, thereby also promoting sustainable development. Jordan’s renewable energy sector, business, financial and health services, transport and logistics, and ICT – sectors that are also expected to boost global FDI flows in 2021 and beyond – have received relatively more FDI in recent years compared to manufacturing and construction. These sectors often have higher productivity levels, create better-paid jobs that can meet the aspirations of Jordanian women and men, and can support green growth. Overall, Jordan’s current comparative advantages present clear investment opportunities in fast-growing high-skilled tradable services as well as some opportunities in certain manufactured and agricultural goods, including the export of chemical products (Hausmann et al., 2020[3]; ILO, 2022[4]). Considering the export potential of sectors that can attract FDI with high impacts on the SDGs – and the barriers that hinder this potential – is important given the small size of the Jordanian market and the limited intra-regional trade.

Attracting MNEs to sectors that can drive the SDGs is crucial, but is not enough to maximise the benefits of FDI in Jordan. The impact of foreign companies’ operations on sustainable development is equally important. The OECD FDI Qualities Indicators show that foreign companies in Jordan perform better than domestic firms in several dimensions of sustainability. They tend to be more productive, pay higher wages, employ more women, and provide more training opportunities. Their performance premium is, however, small and weaker than in other peer countries, suggesting that there is a strong potential for policy interventions that help FDI to achieve better sustainability outcomes. This potential is even higher when it comes to green business practices, an area in which foreign firms perform relatively poorly.

FDI also influences SDG outcomes indirectly through foreign companies’ supply chain linkages and other market interactions with domestic firms. The potential for positive FDI spillovers is, however, limited in Jordan. Supply chain linkages between foreign and domestic firms, a key channel for FDI spillovers, are weak in comparison with other countries (Chapter 2). This limits the ability of foreign firms to influence the business, labour, gender and environmental practices of domestic firms. Furthermore, weak competition due to, among other things, a bloated public sector, has created a large group of small and old unproductive private sector firms that are vulnerable to foreign competitors. This also creates inefficiencies in the allocation of resources and limits labour mobility. Generally, high-skilled Jordanians prefer to work in the public sector because of the attractive working conditions. A more dynamic private sector will enable FDI to reallocate human capital to more productive activities and, in turn, support sustainable development.

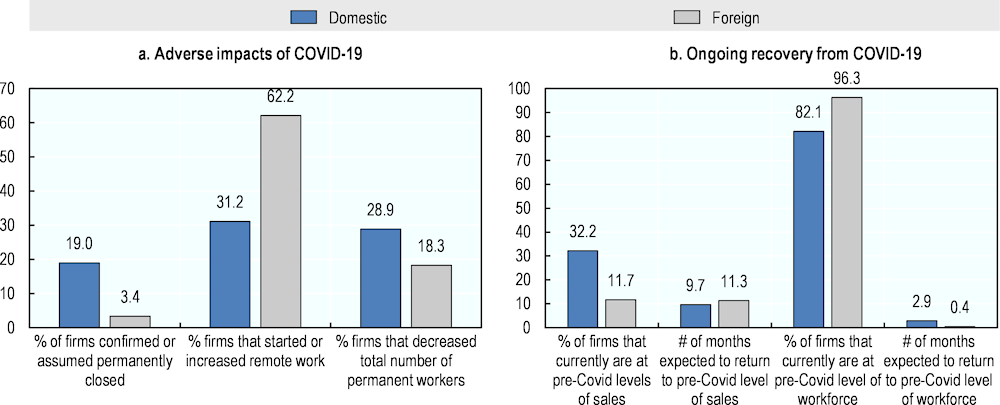

Crippled MNE operations due to the COVID‑19 pandemic may have temporarily delayed Jordan’s achievements towards reaching the SDGs, but MNEs can also support a more inclusive, sustainable and faster recovery due to their higher productivity and stronger resilience to shocks. During the pandemic, the proportion of foreign firms in Jordan that had to close permanently their business was six times lower than of domestic firms (Figure 1.5, Panel A). They were also proportionally more to start or expand remote work, fewer to decrease employment and faster to retrieve their pre‑pandemic workforce levels – similar to foreign firms in other countries (OECD, 2020[5]). Recovery in terms of sales levels is, however, slower among foreign firms, potentially reflecting their high concentration in activities that are severely affected by the pandemic, potentially the apparel sector that employs a large share of women (Figure 1.5, Panel B).

Figure 1.5. The impact of COVID‑19 on the activities of domestic and foreign firms in Jordan

Source: OECD based on World Bank Enterprise Survey of Jordan “COVID‑19: Impacts on Firms” conducted on November 2020‑January 2021.

1.1.3. Improving the institutional framework for investment and sustainable development

Considerations for reforming the institutional framework on sustainable investment

Further consolidate the strategic framework for sustainable investment. Forthcoming horizontal strategies and plans such as Jordan Vision 2025 and Economic Growth Plans should provide coherent and strategic directions on investment and sustainable development objectives. The government should also ensure that investment considerations are explicitly integrated in various strategies on innovation, SMEs, employment, skills, gender, and decarbonisation and vice versa. Strategies should provide clear policy directions, set targets and clarify responsibilities across government bodies to ensure synergies and avoid overlaps.

Centralise information on the strategic framework. In all areas of sustainable development covered in this report, strategies are framed under Vision 2025, but information on strategies and plans under this vision could be further centralised on a single platform with links to websites of ministries and made easily accessible to ministries, agencies, investors and all actors involved in improving the impacts of FDI on sustainable development (including in English).

Strengthen co‑ordination at strategic levels. Policy co‑ordination in the area of sustainable investment could be further strengthened by ensuring that public and private institutions from relevant sustainable policy areas and stakeholder groups (including foreign investors) are represented. The most natural state body for such co‑ordination is the Investment Council.

Co‑ordinate and co‑operate on policy programmes across implementation agencies. Co‑ordination of policy initiatives and joint programmes is currently largely absent in the area of investment and sustainable development. Involving MoI in policy design of other agencies – and vice versa – would help to bring in investor perspectives and develop joint policy interventions.

Develop a national standard for monitoring and evaluation of policies. Currently, the practice of monitoring and evaluation depends on the discretion of policy implementing agencies and, if it occurs, methodologies are not sufficiently transparent. Efforts to collect quantitative and qualitative information from various stakeholders should be strengthened and could involve surveys and public-private dialogue events.

Jordan gives high priority to private investment as a driver for sustainable development

Jordan has a coherent framework of national strategies to support the SDGs with consistent references to the role of private (domestic and foreign) investment. Providing the overarching direction, Jordan’s Vision 2025, the Economic Growth Plan 2018‑22 and other strategic documents point to sectors with significant potential for investment, productivity, employment (including for women) and green growth. The emphasis is on the development of modern, ITC services and sustainable infrastructure (e.g. renewable energy or transport), which is in line with sectoral growth opportunities discussed in this report (Chapter 2).

Vision 2025 is supported by multiple national strategies for the implementation of policy objectives across various areas of sustainable development and policy domains (e.g. Jordan Investment Promotion Strategy; National Policy and Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation 2021‑25; National Employment Strategy 2011‑20; National Strategy for Human Resources Development 2016‑25; National Strategy for Women 2020‑25; Green Growth National Action Plan 2021‑25). While the importance of private investment is mentioned in all strategies, references are sometimes generic and not always linked to specific priority actions or projects; this is particularly true for policy efforts towards a low-carbon economy.

Strategies are not always developed in a co‑ordinated manner both within and across areas of sustainable development. For example in the area of productivity, job quality and gender equality, strategies are introduced without cross-referencing those of other state bodies. On the other hand, the strategic framework for green growth, as a top national priority, has been effectively consolidated since 2017 under the National Green Growth Plan – which could be a guiding example for consolidation and alignment in other sustainability areas. Across areas of sustainability, all strategies are framed under the 2025 Vision but information on strategies and plans under this vision could be further centralised on a single platform with links to websites of the various ministries and made easily accessible to ministries, agencies, investors and all actors involved in improving the impacts of FDI on sustainable development.

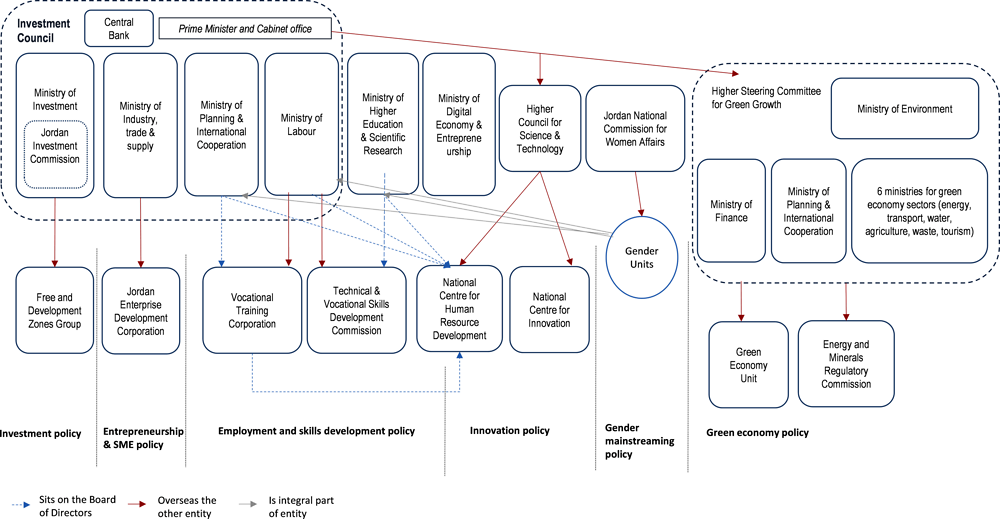

Strengthen policy co‑ordination and promote joint policy initiatives

There are no mechanisms in Jordan exclusively dedicated to policy co‑ordination in the area of investment and sustainable development. Other existing mechanisms nevertheless could take a more prominent role to ensure some strategic alignment at high political level – notably through the Investment Council where the presence of the Ministry of Labour is unique to Jordan, but also through other high-level bodies (Figure 1.6). The creation of a new Ministry of Investment in 2021 that will be responsible for all investment-related affairs and bodies, including JIC and the Public-Private Partnership Unit, could constitute a positive development in terms of streamlining licencing procedures and improved co‑ordination with other ministries, but the institutional reform is still at its early stages.

Co‑ordination could be further strengthened by ensuring that public and private institutions from all pertinent policy areas and all stakeholder groups (including for example foreign investors) are represented in relevant committees, councils and boards of directors. High-level bodies overseeing skills development, innovation, gender equality and green growth are not represented in the Investment Council nor are they all united in other co‑ordination bodies. Yet, in the area of gender equality, both the Ministry of Labour and the Ministry of Planning and International Co‑operation, which are part of the Investment Council, have gender units that help represent gender issues in labour market and investment policy making. Similarly, in the area of green growth, the Higher Steering Committee for Green Growth (HSCGG) reports directly to the Prime Minister who also chairs the Investment Council. This suggests that the Investment Council holds important authority overseeing the framework for investment in green growth.

At the implementation level, horizontal co‑ordination and co‑operation between agencies through joint planning and delivery of policy initiatives is broadly absent and – in some cases – agencies have overlapping responsibilities. For example, there is limited co‑ordination between MoI and the main agencies in charge of delivering employment services and training support, including the newly established bodies in charge of technical and vocational training and skills needs assessments. Similarly, joint initiatives between MoI and the Jordan Enterprise Development Corporation (JEDCO) or agencies working on innovation, gender equality and green growth have not been identified.

Considering ways to involve MoI in other policy domains related to sustainable development could help tailor programmes to the investor needs and concerns (e.g. the design of skills programmes would benefit from investor perspectives to identify and address skills shortages; or investor perspectives could help in the design of green growth programmes and identify key bottlenecks to climate‑resilient investments). In some cases, there is overlap in mandates and responsibilities of different agencies, which can create unnecessary administrative burdens for investors (e.g. several governmental institutions are involved in setting administrative and licensing procedures for renewable‑energy projects). On the other hand, vertical co‑ordination mechanisms between levels of government are fairly well-established (e.g. MoI is well-placed to convey investor concerns to the Investment Council and can thus give important inputs to policy reforms at higher levels).

Figure 1.6. Public institutions influencing sustainable investment in Jordan

Source: OECD based on the FDI Qualities Mapping of Policies and Institutions of Jordan (2021).

Monitoring and evaluation of the impact of policies and engagement with stakeholders happens sometimes but efforts could be reinforced in Jordan. There is no national standard for monitoring and evaluation of policies in Jordan. Rather, the practice of monitoring and evaluation depends on the discretion of each policy implementing agency. For example, in the area of innovation, HCST and the National Centre for Innovation carry out policy evaluation, but the evaluation mechanisms and methodologies are not sufficiently transparent. A key challenge for Jordan’s policy implementation agencies to exercise monitoring and evaluation is a lack of qualitative information received from investors. Jordan could further strengthen stakeholder engagement to assess gaps between laws and their implementation and identify key challenges that policy beneficiaries (e.g. investors, SMEs and workers) may face on the ground. The establishment of the Economic and Social Council in 2009 as an advisory body to the government on economic and social policies demonstrates strong commitment by the government to address this concern.

1.1.4. Improving policy coherence will be crucial to leverage FDI for sustainable development

Clear whole‑of-government strategies and strong co‑ordination mechanisms are the foundations for a coherent policy framework that can enable the contribution of FDI to the SDGs. The Government of Jordan, like many other governments, has advanced meaningful reforms to improve the investment climate, expecting that the developmental benefits of FDI would automatically follow. These benefits did not materialise as much as the government hoped for, however. Beyond a conducive investment climate, wider regulatory reforms and targeted policy support could help unleash the potential of FDI for sustainable development in Jordan.

Policy considerations for the policy framework on investment and sustainable development

Reassess existing restrictions on FDI, notably in service sectors, against public policy objectives of advancing the SDGs and achieving Vision 2025. Restrictions on foreign ownership are prevalent in business services, distribution, transport and logistics, and tourism, sectors where FDI has high potential to generate economy-wide productivity gains, create low and high-skill jobs – including for young women – and support the low-carbon transition.

Pursue pro-competition reforms to reduce “behind-the‑border” barriers and the high cost of doing business, including labour cost. Competition in the product and labour markets will allow for a more dynamic and innovative private sector that enables labour mobility from the public to the private sector and to better absorb the gains (or adverse impacts) from FDI spillovers.

Address regulatory barriers deterring FDI benefits on specific sustainability outcomes. This includes easing the process to establish a business, granting women’s economic rights in the legislation, addressing labour market segmentations and improving collective bargaining rights, and facilitating access to land for renewable‑power projects.

Design policies that can promote FDI benefits on gender equality, reducing carbon emissions, boosting productivity in tradable services and creating better quality jobs. Adjusting the policy mix to adapt it to the changing patterns of FDI could help support the emergence of a more inclusive, greener and knowledge‑based Jordanian economy.

Favour investment incentives related to sustainable development. Continue streamlining tax incentives and opt for incentives related to sustainability criteria, such as companies’ investment in R&D or training, while phasing-out incentives to sectors with declining productivity or high carbon emissions. Periodically assess the relevance of incentives and provide more clarity and transparency on existing incentives, beyond those granted by the Investment Law.

Raise awareness about sustainability standards and encourage companies to disclose their compliance with them. Strengthening the capabilities of the Jordanian NCP by providing him with adequate human and financial resources to fulfil its mandate of, inter alia, promoting responsible business conduct and due diligence in supply chains. Encourage listed companies to disclose their ESG performance based on ASE’ Guidance on Sustainability Reporting”.

Business climate reforms can help unlock the sustainable development potential of FDI

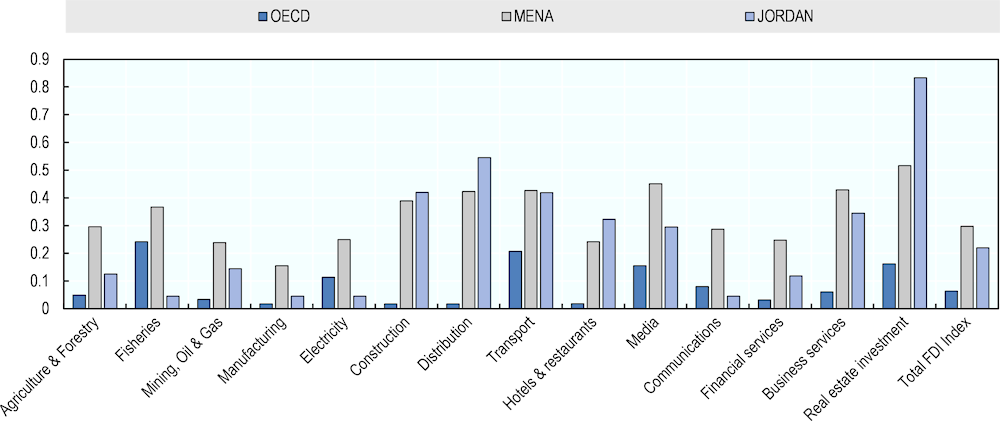

Reform and opening of services could help achieve the key objectives of Jordan’s Vision 2025 and other related national plans. Discriminatory measures on foreign investors’ entry and operations deter FDI and, in turn, related direct and spillover gains for sustainable development. Reforms in Jordan have largely liberalised the manufacturing sector but many other service sectors remain partly off limits to foreign investors (Figure 1.7). Restrictions on full foreign ownership exist in business services, distribution, transports and logistics and tourism, services where FDI entry has a strong potential to generate productivity gains throughout the economy, stimulate labour demand and create high-skill jobs – including for young women – and support the low-carbon transition. Joint venture requirements in such sectors may also hinder foreign investors from deploying their most advanced (green) technologies or responsible business practices, in turn limiting knowledge transfers and the adoption of higher international sustainability standards by domestic competitors and suppliers.

Figure 1.7. FDI restrictions in service sectors can deter economy-wide gains from investment

Note: The OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index covers statutory measures discriminating against foreign investors (e.g. foreign equity limits, screening and approval procedures, restrictions on key foreign personnel and other operational measures). Other important aspects of an investment climate (e.g. the implementation of regulations and state monopolies among others) are not considered.

Source: OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index 2019‑20.

In addition to restrictions on FDI, wider ‘behind-the‑border’ domestic regulatory barriers limit business creation and innovation in Jordan and, in turn, can hamper the sustainable development impacts of FDI. Pro-competition reforms could help reduce the high cost of doing business in Jordan – for instance in the energy sector – and hence increase the country’s competitiveness. Increased competition will also allow for a more dynamic private sector that can enable labour mobility and better absorb the gains from FDI spillovers. Jordan Vision 2025 aims to enhance the ability of firms to grow and compete on a level playing field and the government has recently revised its competition policy to minimise market distortions. The government’s reform agenda also aims to rationalise public sector hiring practices, which could increase the incentive for highly skilled Jordanians to work for the private sector.

Other regulatory barriers influence positively or negatively the impact of FDI on sustainable development in Jordan, but not to the same extent in the different sustainability dimensions. Barriers include, among others, lengthy steps to start a business and access to finance (SME productivity and innovation), legal barriers and loopholes preventing women from participating in the labour market (gender equality), high levels of wage‑setting distortions, burdensome procedures to hire foreign talent and weak collective bargaining rights (job quality and skills development) and challenges in accessing land for renewable‑power projects (reducing carbon emissions). The government has introduced important reforms in all these areas, yet further efforts would ensure that the wider regulatory framework is transparent and aligned with the government’s goal of leveraging FDI as a tool to achieve the SDGs. Section 1.2 and subsequent chapters focus more on the regulatory barriers that hinder the benefits of FDI in specific sustainability outcomes.

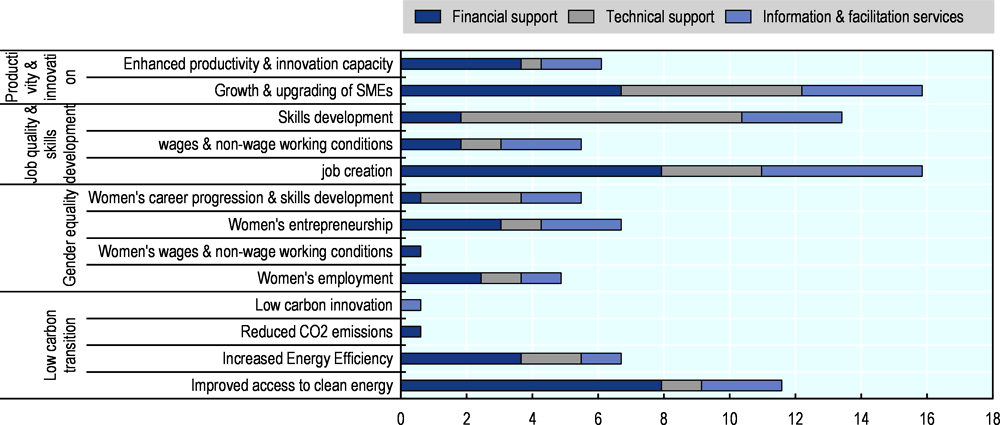

Policies in place can be better aligned with Jordan’s emerging challenges and opportunities

Targeted policies and measures can help governments act on specific sustainability outcomes of FDI. In Jordan, the policy mix reflects the country’s most pressing priorities, as most policy instruments influence – directly or indirectly – the contribution of FDI to job creation and SME growth (Figure 1.8). This emphasis is coherent with Jordan’s daunting needs of absorbing a young and growing labour force through private sector development. Policy interventions that enable the benefits of FDI also focus on incentivising private investment in the clean energy sector and on equipping workers with the right skills, although often only for lower-skilled jobs in the manufacturing sector.

Other sustainability dimensions appear to be less of a priority for the government, yet they are crucial to meeting the emerging challenges and opportunities facing the Jordanian economy. While general employment and skills development policies benefit both men and women, very few programmes specifically target increasing women’s low labour market participation rates. Likewise, only few policies proactively support the benefits of FDI or limit its adverse impacts on reducing carbon emissions, boosting productivity and innovation in key services or creating better quality jobs. Private sector job creation in the manufacturing sector is central for Jordan, but adjusting the policy mix to adapt to changing patterns of FDI could help support the emergence of a more inclusive, greener and knowledge‑based economy in which the tradable service sector plays a greater role.

Tax and financial incentives are the most widely used types of policy instruments across all sustainability dimensions. This is because most of them can affect several outcomes at the same time, for instance by incentivising investment in certain sectors or regions where development needs are high. Fiscal incentives – most often corporate income tax (CIT) exemptions or rate reductions – distort competition and are not always effective in inducing firms to promote sustainable development. While the 2014 Investment Law streamlined the legislative framework under which tax incentives are granted, and created a more cohesive set of measures, investment incentives are still widespread in Jordan and scattered across different laws (OECD, 2018[7]). The government intends to streamline further investment incentives. It is currently working on a new incentives regime that removes provisions related to fiscal incentives from the Investment Law and consolidates them in one single law and under the Ministry of Finance responsibility.

Figure 1.8. Policy instruments influencing the impact of FDI on sustainable development in Jordan

Note: Every policy tool can influence several outcomes across and within the four sustainability areas. See (OECD, 2021[6]) for the methodology.

Source: OECD elaboration based on the OECD FDI Qualities Mapping of Policies and Institutions of Jordan.

The government introduced a new reform in 2020 (Regulation N. 18 of 2020 on CIT Incentives in the Industrial Sector) that phased-out permanently reduced CIT rates in some manufacturing sectors and made tax reductions conditional on reaching specific outcomes related to job creation, gender equality, SME growth and regional development (Table 1.1). This recent reform of CIT incentives in the manufacturing sector could serve as an example to guide the ongoing revision of the tax incentives granted in the 2014 Investment Law and related regulations, which also cover the service sectors. The revision could opt for tax incentives related to similar sustainability criteria (job creation, gender, SME growth) and consider other criteria such as companies’ investment in R&D or skills training, while phasing-out incentives to sectors with declining productivity or high carbon emissions.

Other incentives provide tax allowances and subsidies to investors meeting specific outcome conditions. When well-targeted, such incentives can enhance the impacts of FDI by attracting investors that do not foresee to make profits in the first years of activity. Financial support was introduced temporarily to mitigate the adverse impacts of the COVID‑19 pandemic, for instance, such as Defence Order N.6 that provided wage subsidies to companies to limit job losses, subsidies that were strongly demanded by the foreign firms (Chapter 3). Overall, tax incentives or any other types of financial support that apply horizontally and do not target sectors but rather activities (e.g. R&D activity) are likely to generate fewer distortions. Furthermore, the government should periodically assess the appropriateness and relevance of tax and financial incentives and MoI should provide further clarity and transparency on the wide range of available incentives, beyond those granted by the 2014 Investment Law and related regulations.

Technical support to businesses and workers and, to a lesser extent, information and facilitation services are largely used in most dimensions of sustainability. These policies are crucial to strengthen domestic absorptive capacities and, in turn, better reap the benefits of FDI spillovers or mitigate their potential adverse effects. For instance, existing, albeit limited, sectoral training programmes in ICT can help reduce skills shortages in a high-growth sector where FDI may crowd out competitors unable to retain their talented staff. Information and facilitation services include, among others, FDI-SME matchmaking services and some awareness-raising initiatives on environmental or labour standards, helping companies to voluntarily disclose their compliance with them. In 2018, ASE developed a “Guidance on Sustainability Reporting” to encourage listed companies, among which many are foreign-owned, to report on their Economic, Social and Governance (ESG) performance. Reported information on ASE website is, however, limited.

Table 1.1. CIT incentives related to outcome conditions in the manufacturing sector in Jordan

CIT reductions in the manufacturing sector as of 2023 (year when the phasing-out of CIT reduction is over)

|

Outcome conditions |

Performance criteria |

CIT reduction in pharmaceuticals and garments (in percentage points, baseline: 20%) |

CIT reduction in other manufacturing sectors (in percentage points, baseline: 20%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Job creation |

Increase Jordanian employment by 1% (2.5% if located in QIZs) from the baseline* |

3.1 |

1.9 |

|

Gender equality |

The share of Jordanian women is no less than 15% of total workforce (25% for garments firms in QIZs) |

2.3 |

1.4 |

|

SME growth |

SME selling at least 10% of its production and purchases at least 1% inputs on the domestic market |

2.3 |

1.4 |

|

Less developed regions |

Project located in a the less developed region |

1.4 |

0.9 |

|

Greater Amman region |

Project located in the Greater Amman region |

0.9 |

0.6 |

|

Maximum CIT reduction** |

10 percentage points |

6 percentage points |

Note: * The baseline corresponds to the share of Jordanian workers in total workforce and varies across industries. QIZ: Qualified Industrial Zones. ** Companies get the maximum CIT reduction if they fulfil two or three criteria out of five (depending on the industry and the criteria).

Source: Regulation N. 18 of 2020 on Corporate Income Tax Incentives in the Industrial Sector.

As an adherent to the OECD Declaration on International Investment and MNEs since 2013, Jordan is mandated to establish a National Contact Point (NCP) to promote due diligence for responsible business conduct, covering aspects related to gender, environment, employment and industrial relations. The NCP, hosted by MoI (and previously by JIC), has been largely inactive (OECD, 2021[2]).

Only a few policy instruments in Jordan provide regulatory incentives or impose requirements on investors with the stated objective of improving sustainability outcomes. Providing no or very few regulatory incentives to specific investors is desirable as derogatory legal regimes such as free or development zones distort competition and can become enclaves with lower labour or environmental standards, a risk that materialised in Jordan’s QIZs, where working condition are difficult, although the government has recently been active in restoring better working conditions. Few regulations require companies to disclose their sustainability performance in the area of environmental sustainability. If well-designed, such regulations can be useful instruments to limit the adverse impacts of high-polluting FDI projects (Chapter 5).

1.2. Impacts of FDI and policy considerations by area of sustainable development

This section provides key findings and policy considerations by sustainability cluster, showing how FDI supports a specific aspect of sustainable development (i.e. productivity and innovation; job quality and skills development; gender equality; low-carbon transition) and what reform opportunities exist.

1.2.1. Policies for boosting FDI impacts on productivity and innovation

FDI was a key driver of aggregate productivity growth in Jordan in the 2000s but inflows of FDI have slowed considerably ever since. The bulk of FDI is concentrated in capital-intensive resource extraction and real estate, jointly accounting for more than 70% of total greenfield FDI. Jordan’s labour productivity has been stagnant since the global economic slowdown in 2008, and ongoing conflicts in neighbouring countries have cut off important trade corridors, leading to a significant drop in demand for Jordanian exports and a stark increase in energy prices. Reduced competitiveness in manufacturing has influenced foreign manufacturers to engage less in knowledge‑based activities in Jordan. Due to this, as well as to the limited capacities of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (e.g. related to endowments of and access to strategic resources such as finance and infrastructure), foreign firms are engaging less in business linkages with domestic firms, further reducing the potential for knowledge and technology spillovers from FDI activity. Future growth and productivity are likely to occur in tradable services (e.g. finance, transport, ICT and wholesale and retail services), which have experienced relative stability in FDI inflows in recent years, and are less affected by high energy prices and water scarcity compared to manufacturing.

The productivity opportunity in services, including through foreign investment and linkages with SMEs, is recognised by the Jordan 2025 national strategy and supported by multiple strategic documents and action plans whose governance is entrusted to several state bodies at various levels. Councils at the highest level in Jordan could ensure that public and private institutions from all relevant policy areas and all stakeholder groups (including foreign investors) are represented (e.g. in the Investment Council) and have the chance to enrich policy making processes with their insights. At the policy implementation level, horizontal co‑ordination and co‑operation on investment, innovation and SME programmes could be also strengthened to ensure greater synergies and alignment of resources, policy objectives and actions across Ministries and implementing agencies. Joint programming is currently broadly absent.

Further opening services to FDI could support productivity growth, while at the same time supporting progress in other sustainability areas (Section 1.1). The current fairly open FDI market access regime in ICT services and electricity already involves important productivity opportunities for Jordan. Beyond FDI restrictions, there are several ‘behind-the‑border’ regulatory elements (e.g. intellectual property rights protection, or competition and labour market policy) that influence investment in services; better assessing those would be possible through the inclusion of Jordan in the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI). In the area of policy implementation, Jordan has made notable improvements but starting a business, dealing with construction permits and protecting minority shareholders rights remain key constraints for businesses. Streamlining the regulatory environment for SMEs would contribute to further improving the business climate and thus enabling SME productivity growth.

The mix of pro‑active policies is skewed towards programmes that aim to strengthen the growth and upgrading of local SMEs, while less policy attention goes into enhancing productivity and innovation of the economy as a whole through FDI. Yet, efforts to consolidate Jordan’s research and innovation ecosystem have intensified in recent years. Emphasis has been placed on increasing the financial support allocated for R&D and enhancing access to finance for innovative SMEs. Despite recent improvements in the availability of risk capital for entrepreneurs, more could be done to improve the provision of technical assistance, information and facilitation services to domestic firms that want to further develop their innovation and R&D capacities and serve as suppliers and partners of foreign affiliates. Furthermore, investment promotion policies are not conducive to attracting productivity-enhancing and R&D-intensive FDI. Jordan could reconsider the sectoral targeting of investment incentives away from manufacturing and more towards services and R&D-intensive activities with higher potential for productivity growth. The quality of investment facilitation and aftercare services could be also improved to help identify the sourcing needs of foreign investors and steer FDI projects towards locations with the greatest potential for supplier linkages and thus knowledge and technology spillovers on domestic firms.

Policy considerations to boost the impact of FDI on productivity and innovation

Consolidate the strategic framework for investment, productivity and SME development: Strategies are introduced without cross-referencing those of other state bodies. Information on strategies could be centralised and made available online (including in English).

Ensure that all stakeholders are represented in policy discussions: Councils at the highest level (e.g. the Investment Council) could further ensure that public and private institutions from all relevant policy areas – i.e. investment, innovation and SME development – and all stakeholder groups (including foreign) are represented.

Strengthen co‑ordination and co‑operation among policy implementation agencies: Joint programming is currently broadly absent among the Jordan Investment Commission, Jordan Enterprise Development Co‑operation and the National Centre for Innovation.

Continue reforming and opening services: Services liberalisation would support productivity objectives defined in Jordan’s Vision 2025 strategy and strengthen productivity in other sectors, including manufacturing. The inclusion of Jordan in the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index would allow identifying reform opportunities for ‘behind-the‑border’ regulatory aspects.

Target investment incentives in sectors with higher potential for productivity growth: Jordan could reconsider the targeting of investment incentives away from manufacturing and more towards services with higher potential for productivity growth or R&D- and skill-intensive activities.

Improve the quality of investment facilitation and aftercare services to strengthen FDI spillovers on SME productivity and innovation: Investment facilitation and aftercare can be instrumental in encouraging foreign affiliates to identify and collaborate with local SME suppliers. Jordan could consider increasing the focus of FDI policy on the potential for supply chain development, and ensure that supplier development programmes are aligned with the needs and priorities of foreign investors.

Improve support services for SMEs to strengthen their absorptive capacities: Jordan could facilitate access to finance and improve the quality of technical assistance, information and facilitation services provided to Jordanian SMEs. This could help SMEs develop their innovation and R&D capacities and narrow performance gaps with foreign affiliates.

1.2.2. Policies for enhancing the impact of FDI on job quality and skills development

The Government of Jordan has high expectations that FDI can support quality job creation and skills development. The employment rate is low by international standards, with many people in informal and low-paid jobs, and many young graduates unemployed, particularly women. Insufficient job creation through private investment, combined with an increasing labour force and considerable skills imbalances, are the main challenges facing the labour market in Jordan – challenges that the influx of Syrian refugees and the COVID‑19 pandemic have exacerbated. The public sector is no longer absorbing a large number of new graduates, unlike in the pre‑2000s period, while the private sector often offer less attractive working conditions, thereby limiting high-skill labour mobility from public to private sector jobs.

FDI in Jordan has advanced job creation, improved living standards and developed workers’ skills, but its impact has been limited and not all segments of the population have benefited. Over the last two decades, employment gains from FDI were largest for foreign workers in low-wage sectors such as construction, manufacturing or tourism and, since recently, for the higher-skilled Jordanians working in better-paid sectors like ICT or finance. Despite improving educational attainments, inconsistency between curricula and evolving employers’ needs are preventing Jordan from reaping the benefits of FDI, including services FDI that digitalisation and recovery from COVID‑19 are likely to boost. Labour market gains from FDI remain off limits to low and medium-skilled Jordanian job seekers, who do not always have the incentives or skills to compete with foreigners on low-wage jobs in sectors with challenging, albeit improving, working conditions such as the apparel or chemicals industries – the country’s top export sectors.

Coordination on investment, employment and skills development exist at strategic levels – for instance through the Investment Council – but less across implementing agencies. The fact that the Minister of Labour sits in the Investment Council is a strong signal of the government commitment to policies that enhance the impact of FDI on labour outcomes. It is also particularly relevant as MoI oversees the Free and Development Zones where FDI is prevalent and foreign labour is abundant. Co‑ordination between MoI and implementing agencies providing employment and training support is weaker and joint policy programming nearly inexistent. Involving MoI in the work of relevant skills development bodies such as the newly established Sector Skills Councils could be useful as the agency promotes investment in the same sectors and could bring forward its sectoral expertise and voice the concerns of the foreign investors in terms of skills shortages and training needs.

The government could advance product and labour market reforms that support FDI to create jobs for the highly skilled workers while protecting those at risk of losing their work. Restrictions on foreign ownership exist in business services, distribution, transport and tourism, sectors where FDI has the potential to create jobs for both low and highly skilled Jordanians. Pro-competition reforms to develop a competitive private sector and limit the distortion created by public sector could support labour mobility of highly skilled workers. Labour market regulations in Jordan are not a major constraint for the private sector and recent reforms raised minimum labour standards, but further efforts are needed to level the playing field in working conditions among Jordanians and non-Jordanians and between firms in Free and Development Zones and those outside. Strengthening collective bargaining rights and workers’ voice can particularly help ensure that all workers benefit from FDI by supporting collective solutions to emerging issues and conflicts.

Product and labour market reforms are, however, not enough for FDI to deliver quality jobs. Targeted policies in Jordan aims at stimulating labour demand by attracting investment in priority sectors, locations and occupations and at increasing the supply of adequate skills. Fewer policies pursue the objective of improving wages and non-wage working conditions. If well-implemented, these proactive policies can cushion or amplify FDI spillover on the Jordanian labour market. Policies and programmes are, however, skewed towards Jordanians with medium to low skills in the manufacturing sector. Adapting the policy mix to also target graduates and highly skilled workers in growing service sectors will help Jordan meet the challenges that automation, digitalisation and trade – all accelerated by FDI – impose on its labour market.

Policy considerations to boost the impact of FDI on job quality and skills development

Align strategies and reforms on investment, employment and skills development, including the revision of the 2014 Investment Law and the forthcoming investment promotion and employment strategies, with priority sectors of Vision 2025 and other national plans, particularly high-wage, high-skill and labour-intensive sectors. Strategies should provide clear policy directions on how FDI can improve labour market outcomes, set explicit goals and clarify responsibilities across government bodies.

Strengthen inter-governmental co‑ordination and promote joint policy initiatives. The Investment Council could take a more proactive role to ensure strategic alignment across investment, employment and skills development policies – the presence of the Minister of Labour in the Council should help achieve some policy coherence. At the implementation level, improve co‑ordination between MoI and main government bodies delivering employment services and training support and promote joint policy programmes across agencies.

Reassess existing restrictions on foreign investment against policy objectives of stimulating labour demand, particularly in the job-creating services sectors. Statutory restrictions on foreign ownership exist in business services, distribution, transport and logistics, and tourism sectors where FDI projects have the potential to create direct and indirect jobs for both the low and highly skilled Jordanian youth.

Pursue labour market reforms that are conducive to investment and labour mobility and that promote a better working environment. This includes addressing wage‑setting distortions (e.g. different minimum wages), simplifying regulations on the hiring of foreign labour and strengthening collective bargaining rights to increase labour market integration, promote mobility from public to private sector jobs and reduce informal employment.

Improve investment promotion and facilitation by providing clear information to investors on labour market characteristics, labour regulations, training programmes and employment incentives and accompany them in getting the relevant work permits. Furthermore, set key performance indicators to identify and prioritise investments that create quality jobs.

Raise awareness about international labour standards and incentivise companies to disclose their compliance with them by reactivating the NCP and help it fulfil its mandate of, inter alia, disseminating guidance to MNEs on labour standards and due diligence in supply chains. Encourage companies listed in the Amman Stock Exchange (ASE) to disclose their ESG performance, including on labour, based on ASE’s Guidance on Sustainability Reporting.

Provide integrated active labour market policies that are adapted to investors’ needs while supporting the most vulnerable. This includes upskilling the educated youth while retraining vulnerable groups working in sectors adversely affected by competition, providing more targeted job search services, including transport subsidies, and increasing their outreach, and favouring tax incentives based on companies’ labour market performance and promoting the transition of young graduates to a first-work experience.

Establish robust labour market information and skills anticipation systems that involve investment actors to design evidence‑based employment or training policies and effectively monitor their impacts. MoI could bring forward its sectoral expertise to the Sector Skills Councils and voice the concerns of investors in terms of skill shortages and future training needs.

1.2.3. Policies for improving FDI impacts on gender equality

Jordan has made considerable strides in terms of women’s economic inclusion, but major challenges remain and some have been exacerbated by the COVID‑19 pandemic. Despite significant progress in female education, few women still participate in the labour force. The female participation rate is among the lowest in the world, at only 14%, and the gender pay gap is high even when taking into account factors such as education, age, working time status, and sector. Women work mainly in the service sectors, particularly education, health and social care, and in low value‑added manufacturing industries. A significant proportion of women, about 37%, are in the public sector. Social and cultural norms hinder women’s economic participation in all professions, including entrepreneurship. Female refugees face even harsher working conditions, as they are often employed in informal jobs.

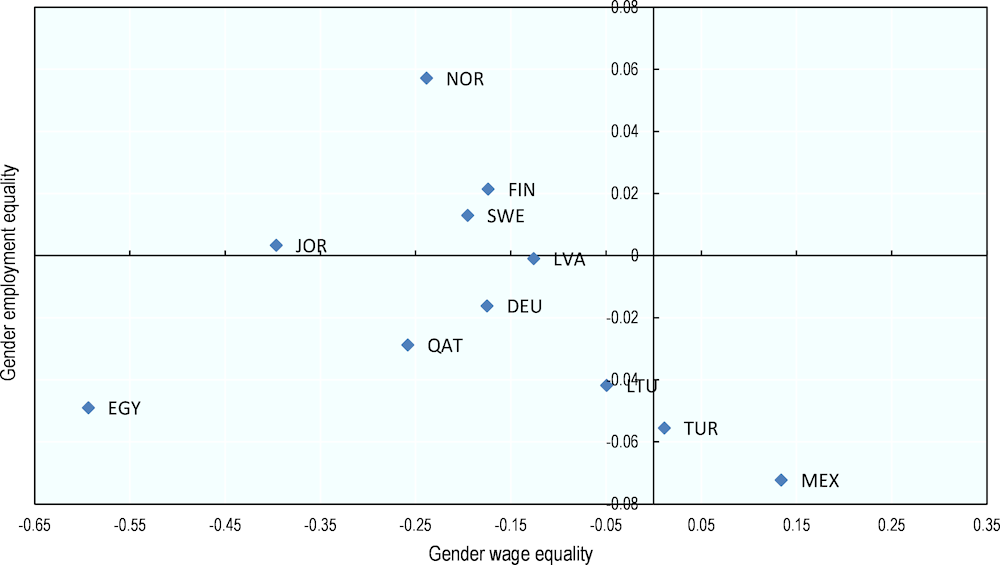

FDI can contribute to greater gender equality in the labour market of host countries. Over the past two decades, the majority of FDI in Jordan has been directed to male‑dominated sectors, such as energy (oil and gas), construction and business services. Gender pay gaps in those sectors, however, are lower than in other sectors (Figure 1.9). Manufacturing industries that employ significant proportions of women, particularly garments and textiles, have received less and, since 2008, declining amounts of greenfield FDI. Moreover, foreign companies are not more gender inclusive than domestic companies. They employ higher proportions of women on average, but are less likely to have female top managers or owners. Working conditions in Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZs), where many foreign textile and garment companies operate, are also described as difficult, especially for female migrants. Jobs in the zones tend to be labour-intensive, low-paid and offer few prospects for professional growth. Business linkages between foreign and domestic firms are significant in some female‑dominated sectors such as garments, but evidence shows that those linkages have not led to job creation in the local labour market.

Figure 1.9. Greenfield FDI is associated with lower gender employment quality but higher gender wage equality in Jordan

Note: Gender employment equality is measured by the share of female employees in total employees. Gender wage equality is measured as the ratio between the average monthly wages of women and men. Data refer to 2019. This figure shows a scatter plot between two Type 2 FDI Qualities indicators. See Annex B of OECD (2019) for a description of the methodology.

Source: OECD elaboration based on Financial Times’ fDi Markets database; ILO and UN National Accounts.

Improving the inclusion of women in the country’s economic life is a policy priority for Jordanian policy makers, highlighted in several national plans and strategies, such as the National Strategy for Women 2020‑25, the Action Plan for Women’s Economic Empowerment 2019‑24 and the Employment Strategy 2011‑20. These objectives are in line with Jordan’s ambition to become a prosperous, sustainable and inclusive economy where all citizens, including women, can benefit from economic growth, as described in its national development plan, Vision 2025. These objectives are also indirectly supported by its investment promotion strategy, which emphasises the importance of attracting foreign investment that creates quality jobs but are not explicitly mentioned. These national strategies and plans are not always developed in a co‑ordinated manner, however. Moreover, continuity of and access to these strategies are not always guaranteed.

The governance framework influencing the impacts of FDI on gender equality in the labour market involves many actors, operating in areas such as investment, entrepreneurship, labour market and education. They include ministries and their implementing agencies, independent agencies, such as the Jordanian National Commission for Women and MoI, and various private and non-profit entities. Several mechanisms exist to ensure co‑ordination between governmental actors, such as gender units in relevant ministries or the National Contact Point for RBC in MoI. For some of these co‑ordination platforms, however, the scope of action and resources are unclear.

Several reforms implemented in the last decade have significantly improved the policy framework that allows for a positive impact of FDI on gender equality. Yet, challenges remain in several areas. FDI restrictions are high in some services sectors with high employment potential for women, such as hotels and restaurants, information and communication, and financial services. Recent reforms of the Labour Law and of the Social Security Law have addressed important gender equality gaps in the labour market. Nevertheless, legal barriers to women’s economic participation remain in areas related to maternity leave, the workplace and inheritance issues.

Jordan has several policy initiatives in place to support gender equality in the labour market. Some of these policies directly leverage domestic and foreign private investment, such as tax incentives granted to manufacturing companies that employ at least 15% of Jordanian women. Financial incentives (e.g. grants and loans) and training and skills development programmes are the main policy instruments used by these initiatives. The lack of monitoring and evaluation systems for these policies and programmes makes it difficult, however, to provide an assessment of Jordan’s overall policy approach. Finally, Jordan has ratified major international agreements on women’s human rights and signed several trade agreements with gender provisions. These international commitments have been important in advancing Jordan’s domestic gender equality reforms.

Policy considerations to improve FDI impacts on gender equality and women’s empowerment

Improve the co‑ordination, continuity and accessibility of strategic planning for gender equality and investment. Strategies in relevant policy areas should be designed in a more co‑ordinated way. They should be developed with more continuity and made easily accessible, e.g. through a common platform in English.

Strengthen co‑ordination between relevant governmental actors to improve the integration of gender objectives in labour market, entrepreneurship and investment policies. The network of gender units in relevant ministries could be expanded and the role of the NCP, hosted by MoI, should be reinforced.

Introduce a system of monitoring and evaluation would improve the effectiveness and co‑ordination of policies to support women’s economic integration. Jordan has several policy initiatives to support women’s economic integration, but the impact of these policies and if and how they are co‑ordinated is unclear.

Reduce restrictions on FDI and foreign personnel in some service sectors could unlock jobs for women. Restrictions on FDI are higher than in the OECD area in some service sectors such as hotels and restaurants and financial services. In addition, restrictions on foreign personnel affect sectors such as ICT, energy and professional services. These sectors tend to employ many women globally.

Advance labour market reforms to close gender gaps and enhance the positive impact of FDI on women. Despite recent reforms, important legal barriers to women’s economic participation persist in domestic legislation in areas such as maternity, sexual harassment at work and inheritance.

Improve initiatives to support female entrepreneurship to help women – owned/led businesses to connect with foreign firms. Programmes to help women-owned/led enterprises connect with foreign companies could help them expand. Strengthening domestic-foreign linkages in sectors dominated by women could also lead to job creation for women.

Increase information and facilitation programmes to overcome social and cultural barriers that prevent women from working in foreign MNEs. Information campaigns to inform communities and families about working conditions and policies to improve women’s security could induce more women to work, including for foreign companies.

1.2.4. Policies for improving FDI impacts on carbon emissions

Carbon emissions in Jordan continue to rise, albeit at a diminishing rate, driven predominantly by the largely oil-fuelled energy and transport sectors. As the technological barriers to further electrification and decarbonisation of these sectors are falling rapidly, the private sector, and foreign investors specifically, can profitably cater to these investment needs. Over the last decade, foreign investment projects have been negligible in the transport sector, and largely dominated by fossil fuels in the energy sector. More recently, FDI has started to shift away from fossil fuels and into clean energy sources. Accelerating this shift is critical for diversifying energy sources, reducing reliance on fossil fuel imports and improving energy security, and will at the same time help advance Jordan’s low-carbon transition.

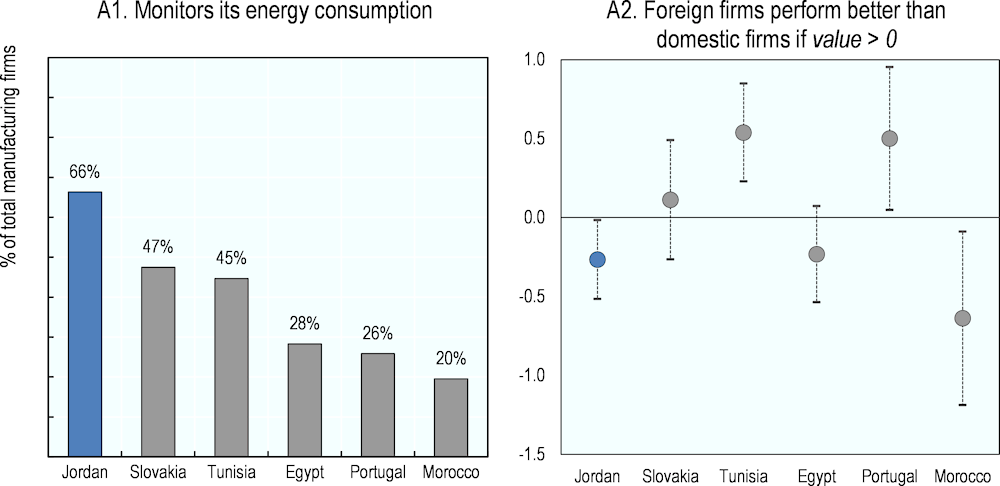

The low-carbon transition requires greening of investments beyond the energy sector. There is evidence that foreign firms may be responsible for over 50% of oil consumed in manufacturing. Moreover, according to the FDI Qualities Indicators, foreign investors in Jordan underperform in terms of green business practices, particularly when it comes to tracking energy use and emissions, and implementing measures to reduce emissions (Figure 1.10). This suggests that there may be little scope for positive spillovers from foreign to domestic firms, when it comes to greening business practices and improving the climate impacts of private investment. Even if foreign firms were to outperform domestic firms in terms of climate impacts (which there is currently no evidence of), the opportunities for influencing the business practices of domestic suppliers is somewhat limited, given to the limited extent of local supply chain linkages.

Figure 1.10. Foreign firms in Jordan perform poorly in terms of green business practices

Note: Panels A and C reflect all firms, while Panels B and D show the percentage differences across foreign and domestic firms (circle) and the 95% confidence intervals around such differences (line).

Source: OECD based on World Bank Enterprise Surveys (2021).

The Government of Jordan has made green growth a top national priority, and demonstrated its commitment to transition towards a green economy through various multi-year strategies and plans, resulting in a series of reforms and proactive policies to support decarbonisation and the green growth agenda. Several reform programmes implemented in the last decade have played an important role in levelling the playing field for foreign investors in low-carbon technologies. These include the unbundling of the power sector to increase competition in power generation and distribution, which has created more space for private investment in renewable energy; and the phasing out of energy subsidies and the resulting price distortions that give rise to over-investment in carbon-intensive activities. While these reforms are a crucial first step to influencing the carbon characteristics of FDI entering the country, greater efforts could be made to align the green growth agenda with the investment promotion strategy and to clarify the role of private investors in advancing low-carbon targets more explicitly and specifically.

Additional policies to stimulate low-carbon investments primarily include measures that seek to expand renewable energy generation capacity, and to promote energy savings and increase energy efficiency of economic activities. The most commonly used policy instruments are a variety of financial and fiscal incentives for investments that achieve these targets. These financial and fiscal incentives are however not advertised on MoI’s website, which raises questions as to whether foreign investors are aware of them. Greater co‑ordination between the main implementing institution, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, and MoI to ensure that available financial incentives are included in promotional material published by MoI may raise the effectiveness of these instruments in attracting low-carbon investments. Other programmes include information campaigns designed to raise awareness among consumers about the emissions characteristics of energy companies, and training programmes designed to promote career opportunities related to low-carbon technologies. Such initiatives enhance the attractiveness of Jordan as a destination for low-carbon investments, and raise the potential for low-carbon spillovers from foreign to domestic firms.

Policy considerations to improve the impact of FDI on carbon emissions

Ensure high-level alignment and co‑ordination across investment and climate policy makers. Jordan has made a visible effort to consolidate its many national strategies and action plans relating to climate change into a single cross-sectoral framework for green growth under the oversight of a cross-ministerial steering committee. To ensure greater alignment with the Investment Council’s priorities, there may be scope for involvement of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources within the Investment Council.

Align the national green growth framework with the investment promotion strategy and clarify the role of private investors in achieving green growth outcomes. Greater efforts could be made to clarify where private investment will be most crucial, and link the identified green growth priority actions to private investment opportunities identified and promoted by MoI. An updated investment promotion strategy should ensure that investment opportunities in renewables are considered on a proactive rather than reactive basis by MoI.

Streamline and unify licensing and registration procedures for renewable projects under one authority. Several institutions are involved in the administrative and licensing procedures for renewable‑energy investments. MoI’s one‑stop shop facilitates licensing procedures for all types of investment; MoI also provides licences to free zone investors, some of which target renewable power generation; however, the main licence that a renewable project developer must obtain is a power-generation licence delivered by the electricity regulator (EMRC). Streamlining and unifying these licensing procedures under one authority can help decrease the transaction costs associated with renewable energy investments.

Consider replacing local content requirements on solar and wind components, with targeted incentives for industrial development. The local content requirements on solar photovoltaics and wind turbines are at odds with Jordan’s relatively limited manufacturing capacity of related components. Such discriminatory measures are likely to discourage foreign investments in downstream solar and wind power generation. Instead, the government could provide targeted incentives for specific solar and wind components that are not yet manufactured locally.

Consider transitioning from a single buyer electricity model to a well-designed wholesale market for electricity. The government should consider enabling the three main electricity distributors to purchase electricity directly from the producers at market prices, in order to level the playing field for foreign investors in renewable power. Gradually transitioning to a well-designed wholesale market for electricity could further enhance the ability of the power sector to accommodate high shares of renewable energy, and accelerate Jordan’s energy transition.

Streamline the land acquisition and land lease process. Policymakers could create a database of government lands available for renewable projects, and facilitate land acquisition procedures through a central office to reduce transaction costs for investors. The government could further identify available private lands, and provide lenders with a mechanism to ensure that leases of land with multiple private owners can be efficiently concluded.

Link investment promotion efforts to low-carbon objectives. MoI could consider further tailoring its investment promotion material and activities to target low-carbon investors across the six green growth priority sectors, with particular emphasis on investment opportunities related to electrification of road transport, and energy saving opportunities in tourism and industry. There may also be scope for linking investment promotion efforts to incentives or requirements related to monitoring and reporting of energy use.

References

[3] Hausmann, R. et al. (2020), A Roadmap for Investment Promotion and Export Diversification: The Case for Jordan, Working Paper Series 2019.374, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

[4] ILO (2022), The Impact of Trade and Investment Policies on Productive and Decent Work: METI Country Report for Jordan.

[6] OECD (2021), FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit, consultation paper, https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/investment-policy/FDI-Qualities-Policy-Toolkit-Consultation-Paper‑2021.pdf.

[2] OECD (2021), Middle East and North Africa Investment Policy Perspectives, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/6d84ee94‑en.

[5] OECD (2020), Investment and sustainable development: Between risk of collapse and opportunity to build back better, Discussion paper for the joint IC-DAC session at the 2020 Roundtable on Investment and Sustainable Development, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/investment/Between-risk-of-collapse‑and-opportunity-to-build-back-better.pdf.

[1] OECD (2020), OECD Review of Foreign Direct Investment Statistics: Jordan, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/investment/OECD-Review-of-Foreign-Direct-Investment-Statistics-Jordan.pdf.

[7] OECD (2018), Enhancing the legal framework for sustainable investment: Lessons from Jordan, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/mena/competitiveness/Enhancing-the‑Legal-Framework-for-Sustainable‑Investment-Lessons-from-Jordan.pdf.