Infrastructure development should be accompanied by effective regulatory oversight and monitoring. The 2020 Sanitation Law of Brazil brought changes to ANA’s regulatory and operational role while raising several challenges, from how it can adapt its mandate and develop its capacity and resources, to how it can embrace issuing standards for service and sanitation, oversight of sub-national authorities and promoting the regionalisation of service provision. This chapter summarises the implications and challenges of the new Sanitation Law and provides examples from international practices as well as relevant OECD normative guidance.

Fostering Water Resilience in Brazil

3. Making water and sanitation regulation in Brazil more effective

Abstract

The 2020 sanitation law

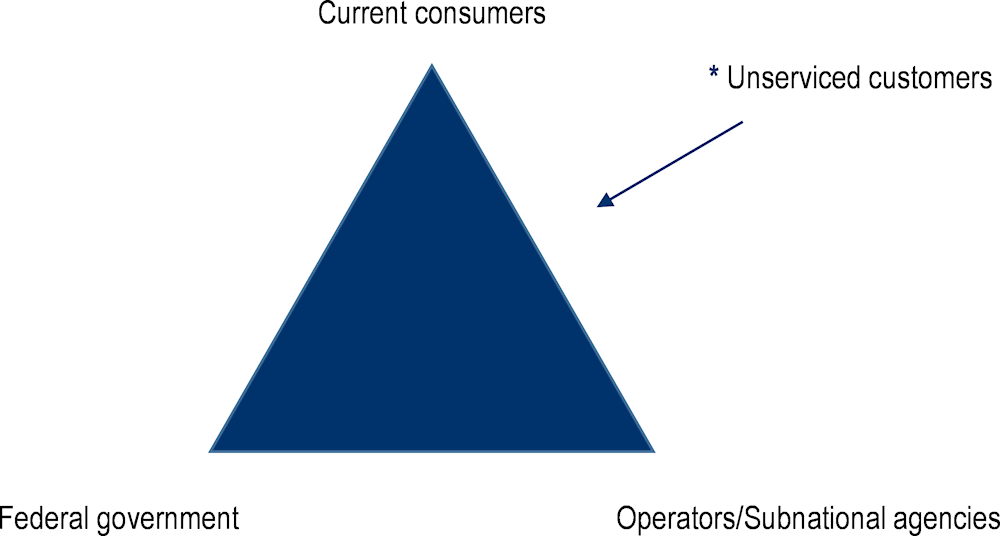

The new Sanitation Law (Law 14.206 of 15 July 2020) marks the reform of the regulatory framework for water and sanitation in Brazil. In addition to expanding ANA’s role from water resource management to defining reference standards for water sanitation services (WSS) and overseeing their application by sub-national authorities (Figure 3.1), the new framework provides increased opportunities for privatisation and private investment, with the aim of developing infrastructure and expanding sanitation services throughout the country (universal provision). This is an important change for the sector, as under the previous legal framework, WSS was regulated locally without federal direction or supervision, which led to dispersed, un‑harmonised and unbalanced rules, creating inefficiencies and regulatory risks. The new Sanitation Law is expected to create a more stable regulatory environment.

Figure 3.1. Evolution of the role of ANA

Sources: Official Journal of the Union (2020[1]), Law 14.026 of 15 July 2020, https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/lei-n-14.026-de-15-de-julho-de-2020-267035421; ANA (2021[2]), Homepage, https://www.ana.gov.br/eng/ (accessed on 20 November 2021); SNIS (2018[3]), The National Sanitation Information System, http://www.snis.gov.br/painel-informacoes-saneamento-brasil/web/painel-setor-saneamento.

The main outcome sought by the new national sanitation framework is the universalisation of provision, with the goal of supplying 99% of the population with drinking water and providing sewage collection and treatment to 90% of the population by the end of 2033.1 A number of means are outlined in the new Sanitation Law for the achievement of the main goal, chiefly the harmonisation of approaches and standards at sub‑national authorities through the adoption of ANA-issued reference standards, capacity building at sub-national authorities, regionalisation and the enhancement of private sector access.

ANA was placed at the centre of the reform, becoming the national regulator for the WSS sector. In particular, ANA has been tasked with the formulation of reference standards, to be followed on a formal voluntary basis by the sub-national authorities, and with the responsibility to guide local regulatory agencies and service providers (in the form of preparing technical studies, guides and manuals, as well as promoting human resource training) (Figure 3.1 and Table 3.1).

Table 3.1. Main changes to ANA roles and responsibilities in the 2020 Sanitation Law

|

Before the 2020 Sanitation Law |

Additional responsibilities of ANA in the 2020 Sanitation Law |

|---|---|

|

National Policy for Water Resources

National System of Water Resources Management (SINGREH)

|

Establishment and monitoring of reference standards for sub-national authorities to:

Oversight of compliance with those standards

Capacity-building of sub-national authorities: responsibility to guide and educate service providers, local regulatory agencies and service providers, as well as to prepare technical studies, guides and manuals, and promote human resource training Voluntary mediation or arbitration in disputes involving granting authorities, regulatory agencies or public basic sanitation service providers Encourage forming blocks of local government authorities to provide services to third parties, allowing less viable locations to combine, enabling private investment (regionalisation) |

|

Main stakeholders:

|

Main stakeholders:

|

|

WSS regulation responsibility: municipal and state level with no federal involvement |

WSS regulation responsibility: municipal and state level with federal-level oversight from ANA |

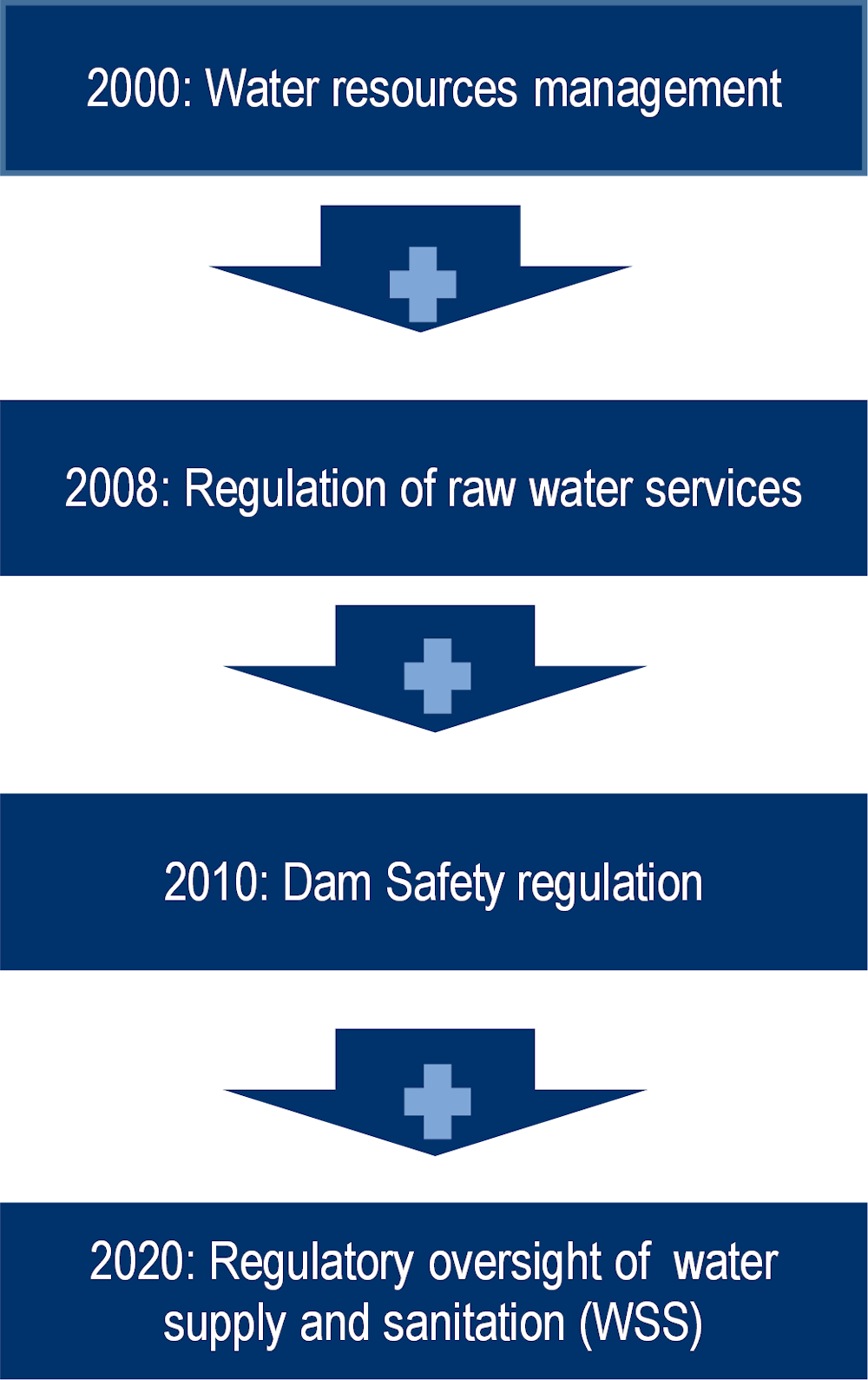

The successful delivery of the new legal framework has the potential to raise challenges for the various actors involved. First, Brazil is a vast continental country, with many realities: social inequality, geographical and cultural differences across its regions, and low capacity to pay for services, all of which are intensified by the COVID-19 crisis, as well as uneven capacity of state-level actors. A process of harmonising regulations with the aim of achieving universal access to WSS for Brazilian citizens in this context will require engagement and flexibility from all actors involved. According to SNIS (National System of Information for Sanitation) data, in 2018 only 83.6% of the population had access to water supply (93% in urban areas), and 53.2% to sanitation services (61% in urban areas) (Figure 3.2 -in Portuguese) (SNIS, 2018[3]),.

Second, the characteristics of the water sector imply that it is highly sensitive to and dependent on multi-level governance (OECD, 2015[4]). This is further exacerbated in the context of a decentralised federation such as Brazil. In addition, there are a high number of sub-national regulatory agencies in WSS: a total of 72, including 34 municipal, 13 inter-municipal, and 25 state regulators. Therefore, there is a need for coordination between ANA, federal regulators, municipal/local governments, and the federal government.

Third, whilst the scope of ANA’s responsibilities has expanded, especially with regard to the new matters of harmonisation (through the issuance of reference standards applicable to all sub-national authorities, as well as the oversight function over their implementation), shortcomings in its mandate are noted, especially in relation to its lack of enforcement powers.

Figure 3.2. Water and Sanitation data – a snapshot for Brazil (2018)

Source: SNIS (2018[3]), The National Sanitation Information System, http://www.snis.gov.br/painel-informacoes-saneamento-brasil/web/painel-setor-saneamento.

Making the reform effective

According to international practices and OECD normative frameworks, some key dimensions should be taken into account by ANA for the successful delivery of the new national framework and legislation. The proposals are described below.

Achieving role clarity

The reform of Brazil’s water and sanitation sector is an ambitious undertaking and its success rests on the collaborative effort and effective coordination of all actors. The new regulatory framework defined in the Sanitation Law provides for long term goals (i.e.: December 2033 for the achievement of universal provision of WSS).

At the same time, the framework implies that a high number of actors need to be involved for the framework’s successful delivery. As outlined in Table 3.2, the current sector relationship matrix is complex, even when disregarding current and future customers, or investors: municipal, regional, and state authorities retain responsibility for the provision of services and development of local regulation, with federal authorities looking after national regulation, as well as planning and funding infrastructure.

Table 3.2. WSS framework and actors involved

|

Activity |

Actors responsible |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Municipal authorities |

Regional/inter-municipal authorities |

State authorities |

Federal authorities |

|

|

Service provision |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Development of regulation |

X |

X |

X |

X (ANA) |

|

Infrastructure planning |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Funding of infrastructure |

X |

X |

||

Source: Official Journal of the Union (2020[1]), Law 14.026 of 15 July 2020, https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/lei-n-14.026-de-15-de-julho-de-2020-267035421; ANA (2021[2]), Homepage, https://www.ana.gov.br/eng/ (accessed on 20 November 2021); OECD/ANA (2019-21[5]), “Water Governance Workshops”.

The South Australian regulator, the Essential Services Commission of South Australia (ESCOSA), was in a similar position to ANA while receiving additional responsibilities because of regulatory reform. Similarly to ANA, ESCOSA operates in a federal system (however without federal oversight) and is impacted by a number of layers of governance. To achieve role clarity and define responsibilities for all actors involved in the new regulatory make-up, ESCOSA and the other sector actors created a series of high-level pacts (“relationship agreements”). Through those, the relevant actors understood each other’s short- and long-term objectives driven by the reform, and were able to act in sync for the achievement of the new policy objectives (ESCOSA, 2020[6]). In addition, such high-level pacts can become useful operational tools and be referred to as needed if dialogue or cooperation between actors goes off track.

An effective regulator must have clear objectives, with clear and linked functions and mechanisms to coordinate with other relevant bodies to achieve the desired regulatory outcomes. OECD Best Practice Principles on the Governance of Regulators describes how regulators can have a well-defined mission and distinct responsibilities within regulatory schemes. As OECD (2014[7]) states:

Unless clear objectives are specified, the regulator may not have sufficient context to establish priorities, processes and boundaries for its work. In addition, clear objectives are needed so others can hold the regulator accountable for its performance.

The strategic framework, including the vision, mission, and strategic objectives of the regulator offers an opportunity for the definition and communication of roles, responsibilities and expectations. Such exercises facilitate engagement of stakeholders in a discussion on the strategic direction of the regulator, while at the same time it is considered good practice that economic regulators have independence in defining their long-term strategies. OECD data shows that in the water sector, 70% of regulators received inputs from the government in the process of setting their strategy (OECD, 2018[8]). Such collaboration is especially relevant in the current Brazilian context, with the implementation of such a significant reform in water and sanitation services. The final strategic framework will need to be communicated to stakeholders in a transparent manner, possibly through a communications strategy that can include an updated website for ANA, and effective monitoring of strategic objectives.

In the case of ANA, the regulator must also manage potentially conflicting functions of water resources management and economic regulation of WSS (i.e., the performance of one function could potentially limit, or appear to compromise the regulator’s ability to fulfil its other function). Such arrangements where a regulator is working on different public interests require good regulatory practices. Therefore, having institutional arrangements that ensure transparency in decision-making, accountability of decisions and actions are crucial. ESCOSA has gone through numerous changes in mandate over the past decade. ESCOSA’s experience suggests that clear regulatory objectives, coupled with robust internal governance and focus on creating good internal culture and values yield benefits in the long term.

Similar to Brazil, the European Union (EU) is a vast territory formed of 27 members with a very varied local geography, socio-economic priorities and consumer needs. Nonetheless, the EU has succeeded in introducing a common framework for the quality of water resources across all its members, while taking account of regional specificities. This is achieved through different legislative vehicles (directives and regulations), which set common principles (for example: recovery of costs, or the obligation for polluters to pay for the environmental harm they generate) and specific objectives (like on drinking-water quality standards, wastewater treatment, sludge disposal, etc.), while at the same time allowing EU members flexibility in application. In addition, data from the association of water regulators in the EU (Box 3.2) shows a wide scope of action among regulators.

As can be seen from the example of ARERA in Italy, the independence of a regulator (including financial, human resources and internal organisational aspects), is a key asset in enabling it to deliver its regulatory scope of action, as shown by the areas of the independence of ARERA (Box 3.1). In addition, similar to ANA, ARERA has gone through a change in functions in the past decade, which prompted it to reshape its regulatory approach to deliver the national policy for WSS.

Box 3.1. Independent regulation in Italy

The scope of action of the independent Italian regulator, ARERA is supported by a culture of independence.

Table 3.3. Scope of action and independence of ARERA

|

Scope of action of ARERA |

Independence of ARERA |

|---|---|

|

Economic regulation

Enforcement

Information and institutional advising powers |

|

Source: OECD/ANA (2019-21[5]), “Water Governance Workshops”.

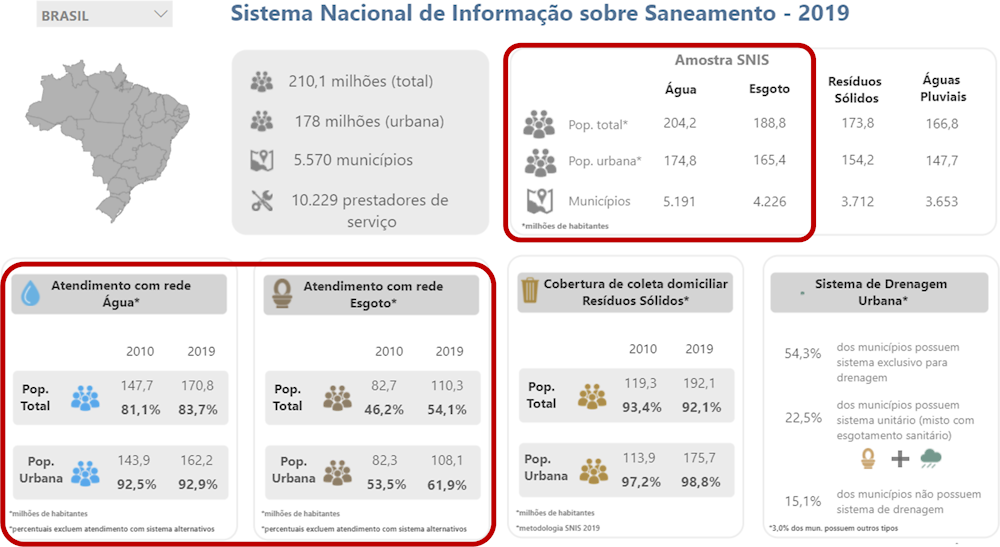

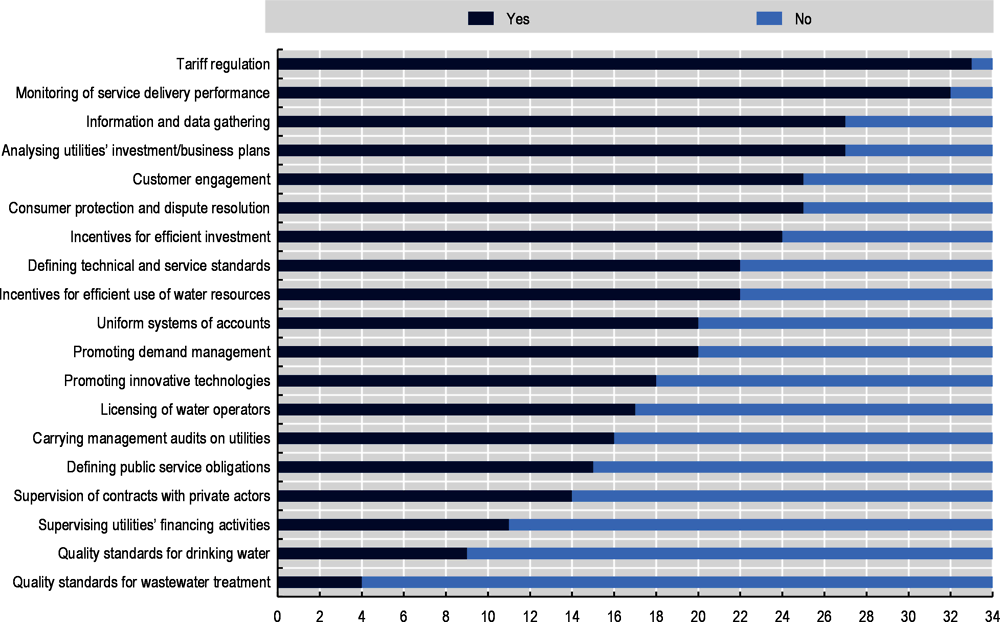

Box 3.2. European Water Regulators (WAREG) scope of regulatory action and independence

WAREG data suggests that regulatory agencies in the European Union have a wide scope of action, with responsibilities ranging from the setting of consumer standards and development of quality standards to data collection and tariff approval. This goes together with funding independence, with more than half of WAREG agencies receiving their main funding from the regulated companies.

Figure 3.3. Scope of regulatory action in WAREG

Source: OECD/ANA (2019-21[5]), WAREG (2021[9]), Water Regulatory Governance across Europe, https://www.wareg.org/documents/water-regulatory-governance-around-europe/.

The implementation of the new law will require:

Clear leadership by the Ministry of Regional Development and action by the Ministry of Economy, ANA, sub-national authorities, service providers, civil society and consumers. Successful implementation of the reform rests on the collective effort of all actors and role clarity of each entity. In this ecosystem, it will be essential for ANA to define its new role regarding the reform and goals set by the government, and communicate this role, its responsibilities and areas of action to all stakeholders.

Relevant stakeholders to determine their ex-ante “definition of success”. More specifically, this should include realistic and attainable short- and long-term objectives and milestones for the stakeholders, as well as convergence areas for coordination among the stakeholders. The new legal and policy framework is a substantial undertaking that advances long-term goals. To this end, ANA should seek to build on its previous experience and draw realistic plans on what objectives are attainable in the short term, and which other goals require longstanding and multi-year work together with its stakeholders.

The facilitation by ANA of a higher-level pact among the actors involved in the WSS ecosystem, in a similar framework to the one created on water resources management in 2015 between ANA and the 27 states, which was based on conditionalities. ANA should build on this previous experience in order to cement the basis of a regulatory scheme in sync with the objectives of other actors in the context of the new Sanitation Law.

Acknowledgement within the high-level pact that the reform and its implementation change dynamics between institutions intervening in the sector and create “winners” and “losers” in terms of responsibilities and powers. The implementation of the reform will require identification of these changes and how they affect different stakeholders and inter-institutional relations. Engagement and capacity-building activities may need to be differentiated between these institutions.

Coordinating effectively

The reality of the new water supply and sanitation policy is that there will be a reallocation of responsibilities within the WSS ecosystem. In designing its strategy for the implementation of the new framework, ANA should be mindful of how such changes influence the process of coordination with other stakeholders. As ANA builds relationships with sub-national authorities, it may encounter resistance to change. Sub-national authorities will need to adopt and follow the ANA-issued regulations, and control is removed from local authorities that were previously not subject to federal oversight and had historically defined their own regulatory frameworks. A key challenge for ANA is to engage with sub-national authorities effectively, so that all parties have a shared understanding of the law and the regime, and that sub-national regulators have a simple set of tools to get them started in adopting the new reference standards and enhancing the use of best practices. There is a need for buy-in from all actors on shared objectives, including those who may feel they lost autonomy or freedom of action due to the reform.

Through the legal and policy context created by the new framework, and with the aid of international best practice, there is great scope for cooperation between ANA and the sub-national authorities, as identified using the guiding framework of the OECD Principles on Water Governance (Box 3.3).

A key coordination mechanism will need to be in place between ANA and the sub-national authorities to ensure that in the application of the new law, there is no formal or perceived conflict in relation to:

who takes the final decision

who implements the decision

who evaluates the impact and regularly reviews the implementation process.

Box 3.3. Developing effective coordination following the OECD Principles on Water Governance

The OECD Principles on Water Governance (OECD, 2015[10]) provide a toolkit for developing effective coordination. Applied to the Brazilian context using the 2017 unpublished paper on the Governance of Drinking Water and Sanitation Infrastructure in Brazil (OECD, 2017[11]), the following can be outlined:

1. Effectiveness:

a. There is a need for coordination of municipal sanitation plans with national, state and regional policies.

b. There is a need for horizontal coordination and a clear prioritisation of targets at the federal level across programmes for grant funding in sanitation.

c. Information about the number of municipal supply systems in Brazil needs to be consolidated.

d. There is a need for a more consolidated approach, in comparison to the current fragmentation of responsibilities and programmes among federal authorities.

2. Efficiency:

a. There is a need for technical, planning and implementation capacity in municipalities.

b. Quality control needs to be implemented.

c. Financing matters, such as the ability to spend funds allocated, economic sustainability, lack of public confidence, entry of private investment, need to be addressed at the sub-national level.

3. Trust and engagement:

a. There are concerns about conflicts of interest at the municipal level.

b. There is weak participation of stakeholders and consumers.

Source: OECD (2017[11]), Report on the Governance of Drinking Water and Sanitation Infrastructure in Brazil, https://www.ana.gov.br/todos-os-documentos-do-portal/documentos-sas/arquivos-cobranca/documentos-relacionados-saneamento/governance-of-ws-infrastructure-in-brazil_final.pdf.

This complements the regulatory approach examples from Italy at ARERA and from Australia at ESCOSA, where changes in the regulators’ mandate prompted renewed coordination and dialogues with other national actors and industry. Effective coordination can be achieved through several key activities:

ANA needs to engage with sub-national authorities so that all parties have a shared understanding of the law and the regime. For this, the OECD Principles on Water Governance as applied to the Brazilian context need to be considered. More specifically, there needs to be horizontal coordination at the federal level so that the various programmes for grant funding are aligned. There is a need for consolidation in approach among the federal authorities, and quality control needs to be implemented in a harmonised manner.

ANA can facilitate a dialogue with other state authorities, including the sub-national regulators, so that the responsibilities of each agency are understood. Beyond increasing awareness, the sector actors need to be committed to the delivery of the new framework.

Defining an adequate transition period and managing expectations of ANA

A timing difference will arise between the passing of the new Sanitation Law and the development of reference standards by ANA, as well as the adoption of the regulations by sub-national authorities. At the time of the workshops (October 2020), ANA already published the timetable of consultation and the prioritisation list for the development of the reference standards (ANA, 2020[12]).

In the process of developing regulations, and especially in this transition period, ANA should appraise its status quo. This can come in the form of a “gap exercise”, though which ANA identifies on the one hand areas of regulation that work adequately in sub-national authorities and can thus be adapted for national scale-up very quickly, and on the other hand areas that need significant improvement and need an overhaul.

The new Sanitation Law is a long-term process, which represents a major overhaul from the previous framework in WSS. Therefore, it raised high expectations with the public and key stakeholders. Most of these fall to ANA, being the institution at the centre of the reform. Therefore, there is a need for ANA to deliver early successes, or “quick wins” in the first one or two years following the entry into force of the new law to show stakeholders the positive changes which stem from the reform. For this, the pilot projects (such as the upcoming water and sewage concession project in Alagoas) are important as they will set the tone in relation to how the framework can be put into practice.

In addition, the transition period will bring specific challenges that ANA, the federal government as finance provider and the sub-national authorities will need to manage. For instance, the vast majority of current contracts are concluded under the legal framework, and some have significant deficiencies. These contracts will need to be given special consideration. Also, a few contracts are expected to be signed in the immediate period after the passing of the new Sanitation Law. Although the reference standards are not finalised, specific objectives or principles need to be developed by ANA so that the new contracts are compliant with the new framework and good practice that is aimed to be adopted in Brazil.

Furthermore, ANA will need to be mindful of the legal precedent from the local legislature or state courts. Some of these might not be compatible with the reference standards that ANA intends to set, and ANA together with sub-national authorities will need a strategy to manage eventual discrepancies in the transition period.

ANA needs to manage the expectations which arise from its role as a standard-setter – more specifically in relation to the quality of regulation at the local level, which is expected to increase, not only through uniformity but through the sharing and infusion of good practice into sub-national authorities. Finally, ANA is once-removed from the service providers in its role as supervisor of state regulators (as local regulators will supervise the providers), and the success of the final desired outcomes will rest on constructive and effective relations between the federal and state regulators.

In sum, managing the transition period will require:

An assessment by ANA of the status quo across all sub-national authorities, as well as an appraisal of current adequate standards and practices at some sub-national authorities.

ANA should take a clear stance in managing expectations in the short term in relation to what can be delivered for the consumers and the sector in the next couple of years, as well as how the provision and the contractual practicalities will be dealt with until the reference standards have been developed and implemented.

Building adequate human and technical capacities

ANA is regarded by stakeholders as professional, mature and well-respected. The addition of new responsibilities through the 2020 Sanitation Law came as recognition of its previous capacity and success in the area of water resources management. To implement the reform, the new mandate and functions must be accompanied by an effort to ensure funding, skills and competences, as well as unified culture.

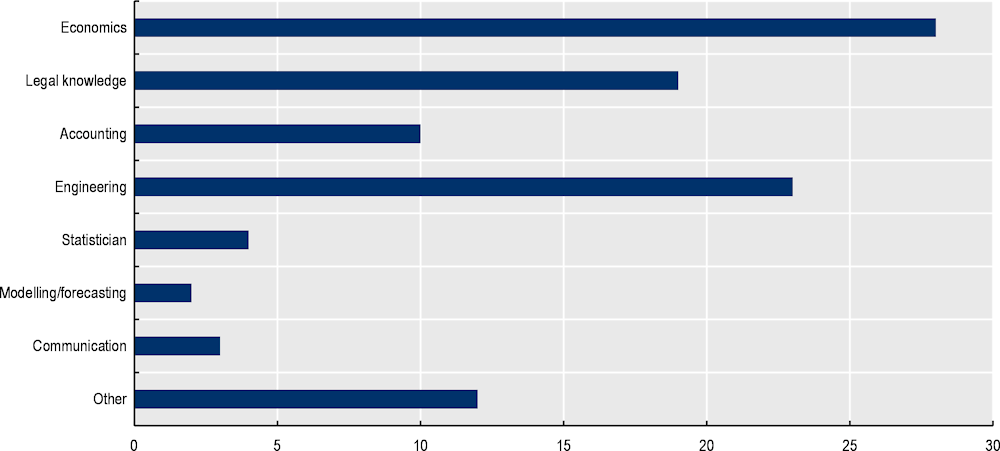

Current skills within ANA do not necessarily fit the new functions. At the moment, ANA has adequate human resources for water resources management. The new responsibilities in relation to the regulation of WSS (issuing of reference standards and oversight, capacity building, relationship building, etc.) require focusing on a different set of skills. Usually, staff of water regulators requires expertise from the economics, accounting and legal professions (Figure 3.4).

Aside from an assessment of the skills needed, the fiscal situation in Brazil means that ANA will encounter difficulties to update its workforce given stringent federal rules. The Brazilian Ministry of Economy enforces the rules around recruitment and headcount, with the requirement that public agencies file a request for public exams with the Ministry of Economy to recruit personnel for professional positions. Such positions will make up the bulk of ANA’s workforce needed for the delivery of the new mandate. Historically, the Ministry of Economy authorised a few public exams for public agencies with the justification of maintaining fiscal balance. Although federal restrictions on career progression based on experience and academic training, and salary increases in line with the length of service have been lifted, other restrictions, such as on movement of personnel across agencies (Government of Brazil, 2018[13]) remain.

Figure 3.4. Job families in water regulatory agencies

Note: Based on OECD Survey on the Governance of Water Regulators (2014).

Source: OECD (2015[14]), The Governance of Water Regulators, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264231092-en.

In sum, the following solutions can be considered:

At the moment, ANA has adequate human resources for water resources management. The new responsibilities in relation to the regulation of WSS (issuing of reference standards and oversight, capacity building, relationship building, etc.) require a focus on a different set of skills. Therefore, it is advisable that ANA not focus only on the substance of the regulatory reform, but also on the internal management and resources needed for the delivery of early successes. For instance, ANA will need to rethink its skills set and add more legal, economics and data analytics specialists to an already well-established engineering-focused staff base. Integrating new professionals into ANA will likely be a challenge since current professionals will have to “make room” for additions. Further, the various disciplines will need to work together to add maximum value to ANA’s decision-making and regulatory processes, rather than competing internally.

ANA should be mindful of the additional financial resources needed to carry out the mandate bestowed by the new Sanitation Law, as well as consider how the increased financial burden will be resourced, and how this might affect its independence in the long term.

Achieving effective oversight and enforcement

The new Sanitation Law tasks ANA with the responsibility of overseeing the adoption of and adherence to the new WSS reference standards by the sub-national authorities. However, the new function is not accompanied by corresponding enforcement powers, which is at odds with OECD best practice recommendations that “all key regulatory functions are discharged by responsible authorities with enforcement powers”. This suggests that ANA has a narrow scope of action when it comes to its regulations. However, it can develop a benchmarking system that presents performance comparisons. The increase in transparency can put pressure on actors that are not implementing reference standards.

OECD data from the survey on the Governance of Regulators (OECD, 2014[7]) suggests that among the five economic sectors, the scope of action of water regulators is the second least restricted. The scope of action refers to the range of activities that the regulator can perform, including decision-making, enforcement and sanctioning powers. Instead of enforcement mechanisms, the new law creates indirect incentives for sub-national authorities to adapt ANA-issued WSS regulations – notably that the federal government will provide municipalities with access to federal funding for WSS contingent upon the adoption of the regulations issued by ANA by the sub-national regulatory agencies. From an interactive polling on Day 3 of the second workshop session, it emerged that by an overwhelming majority the participants viewed the need for appropriate tools for rewarding good performance and penalising poor performance as a top priority tool for ANA to deliver the national sanitation strategy.

The new Sanitation Law bestows onto ANA the responsibility to regularly review the progress of sub-national authorities in adopting the reference standards. However, ANA has no enforcement powers to sanction non-compliance, apart from withholding federal funding from state level regulators in case of non-compliance with reference standards. There are no legal tools for ANA to develop a compliance-driven, incremental approach to enforcement. In addition, the current state of play suggests that municipal authorities have received funding even in the absence of adopting ANA-issued regulations and designing municipal sanitation plans. Enforcing rules and pursuing policy in a context where implementation and supervision were previously lax constitutes a challenge. However, there are several approaches that ANA can develop to mitigate this structural shortcoming regarding its regulatory powers.

Even in this legal context, the OECD Best Practice Principles on Enforcement and the OECD Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections Toolkit (OECD, 2018[15]) offer ANA guidance on developing a strategy for the performance of effective inspections. The aims of a good enforcement system are to:

Deliver the best possible outcomes in terms of risk prevention or mitigate and promote economic prosperity, enhance welfare and pursue the public interest.

Ensure trust and satisfaction among different stakeholders, whose perspectives often conflict (OECD, 2012[16]). This is important in the current Brazilian context, where roles, responsibilities and functions of different sub-national authorities and local providers might change long-term while implementing the new WSS framework.

Even in the absence of enforcement powers, ANA can and should use a suite of “soft approach” tools to increase the likelihood that sub-national authorities become more compliant with ANA-issued regulations. These are:

Engaging with the sub-national agencies. This is explained in detail in section “stakeholder engagement” below. ANA’s role will be crucial in making the relevant WSS sector actors involved in a meaningful way in the process of setting the reference standards.

Strengthening and building capacity. Providing capacity-building to sub-national WSS regulatory agencies is one of the ANA’s main new responsibilities that can be leveraged to support state regulators’ compliance with new regulatory requirements. To discharge the duty of capacity-building successfully, ANA needs to start by assessing the current skills and gaps in knowledge or skills at state regulators. In this manner, it can identify good practices to share between state regulators and identify priority areas in the short term and develop a longer-term strategy.

Increasing transparency. On one hand, transparency needs to be implemented in the functioning of the WSS sector (i.e., visibility of contracts, bid documents, performance indicators and progress against them, etc.). On the other hand, ANA’s analyses and performance assessments on sub-national authorities’ compliance with the reference standards (via a benchmarking system), as well as forward-looking strategies and stakeholder engagement plans/outcomes need to be made accessible in the public domain and written in a language that is accessible to specialised stakeholders and the wider public alike.

Collecting data and reporting to ANA. There is a need for goals and targets for service providers (for instance, verifiable and clear thresholds that ANA receives). These should be codified in the reference standards and will need to include pre-set regulatory outcomes. ANA should also consider an array of means through which it receives information, including making use of current systems, such as the National Information System for Sanitation (SNIS). As noted from the example below (Box 3.4) at the Australian regulator, ESCOSA, the iterative regulatory model implies the use of a range of data and varied information for the regulator to perform ex-post analysis of the regulation. Similarly, the European Union carries out “fitness checks” to ensure that previous legislation is fit-for-purpose, and the result of the checks are taken into consideration as part of the broader legislative impact assessments in the water sector (EC, 2020[17]). In addition, the Italian national independent regulator, ARERA, employs a site of data-gathering powers to support its regulatory and enforcement actions.

Finally, ANA can explore the development and use of new approaches based on the principles of “responsive regulation”. In other words, enforcement action should be modulated depending on the profile and behaviour of specific businesses. However, from a behavioural perspective, a sanction-led approach has shown to be ineffective at deterring poor behaviour and is premised on the faulty assumption that market actors are likely to misbehave. In fact, research shows that only a small number of people intentionally do bad things. Research further shows that most people want to do the right thing most of the time but might not know what or how to do it. Therefore, what is needed is help to do the right thing (Hodges, 2017[18]). This is the core of Ethical Business Regulation (EBR).

EBR draws on the findings of behavioural psychology, shared ethical values, and economic and cultural incentives, and starts from the core idea that decisions are made by people, rather than organisations. EBR implies a collaborative approach to the development and implementation of regulation, and implies dialogue between market actors, their stakeholders and public officials based on a shared ethical approach. In the absence of enforcement powers, the application of EBR elements in the oversight and regulatory process can be a strategy that ANA employs. EBR was embraced by the Water Industry Commission for Scotland in the process of future charges review, and allowed the regulator to reshape not only its approach to regulation but also its relationship with key stakeholders, including industry and consumers (Box 3.5). ANA can look at adopting EBR principles in the development of its reference standards, as well as in devising its stakeholder engagement strategy, which is further discussed in sub-section “Ensuring effective stakeholder engagement”.

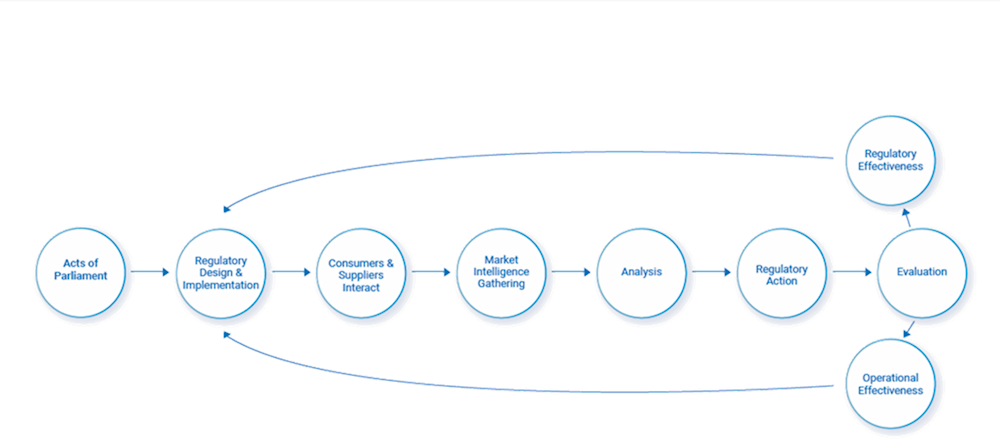

Box 3.4. ESCOSA Business Model

The ESCOSA business model presupposes an iterative approach to regulation, whereby performance and evaluations are defined at the end of the regulatory cycle. Therefore, regulations are reviewed in light of the regulator’s strategy, so that they remain relevant and allow ESCOSA to deliver in line with its mandate.

Figure 3.5. ESCOSA business model

ESCOSA has a long-term objective defined as “the protection of the long-term interests of South Australian consumers with respect to the price, quality and reliability of essential services”, which is defined by legislation. On this, the regulator built its purpose statement of adding “long-term value to the South Australian community by meeting its objective through its independent, ethical and expert regulatory decisions and advice”. In its strategy document, ESCOSA goes further and defines the values which will enable it to achieve its statutory objective, and thus guide its regulatory activities: responsiveness, accountability, innovation and the building of inclusive relationships.

Source: ESCOSA (2021[19]), Strategy 2021-2024, https://www.escosa.sa.gov.au/about-us/strategic-plans.

Box 3.5. Ethical Based Regulation at WICS, UK

The Water Commission Industry for Scotland has been reviewing its charges for water for the period 2021-2027. In doing so, WICS worked closely with water industry stakeholders to put in place the key elements of a new regulatory approach, which focuses on establishing the best outcomes for customers, communities and the environment.

In particular, stakeholders have committed to adopting the principles of Ethical Business Regulation (EBR), which requires open and honest conversations about the future challenges for the Scottish water industry and how best to tackle them. Transparency was determined as paramount in all interactions between the regulator, the providers of services and other stakeholders (including the public and consumers).

Source: WICS (2020[20]), Strategic Review of Charges, https://www.watercommission.co.uk/UserFiles/Documents/VB2140%20WICS%20Methodology%20update_8.1.pdf; WICS (2020[21]), Strategic Review of Charges 2021-27 – Draft Determination,

Several solutions can be devised for achieving oversight in the absence of enforcement powers at ANA:

ANA should ensure that the rules around the allocation of funding for authorities that did not follow the reference standards are enforced. Such actions demonstrate the robustness of the framework and set the tone for how the new policy is to be pursued.

Even without enforcement powers, a suite of soft tools can be implemented by ANA, as follows:

maintaining continuous and meaningful engagement with the sub-national agencies

strengthening and building capacity at sub-national WSS regulatory agencies

enhancing transparency in decision-making and in the functioning of WSS

establishing a robust system of data collection, analysis and reporting.

ANA should consider the development of alternative, behaviourally driven approaches to the development of regulation, such as EBR, which implies a collaborative approach and dialogue between market actors, their stakeholders and public officials, based on a shared ethical approach.

Ensuring effective stakeholder engagement

In the process of stakeholder engagement, ANA should be mindful of the stakeholder groups it needs to engage with and define their role in this process since several different categories will need to be included. These are:

the government, as the actor that defines the legal framework and national WSS strategy

operators and sub-national agencies (including the employee groups such as syndicates and unions) as providers of services

consumers, both current and future, which the national policy aims to affect

For this process to be successful, as the OECD normative framework (OECD, 2020[22]) suggests, there might be a need for ANA to educate stakeholders about engagement culture: stakeholders need to be informed about when and why they have a chance to influence the regulatory process. This would be especially relevant for smaller sub-national authorities that did not go through an engagement process before, or for newly established consumer groups created to address actors in the new system.

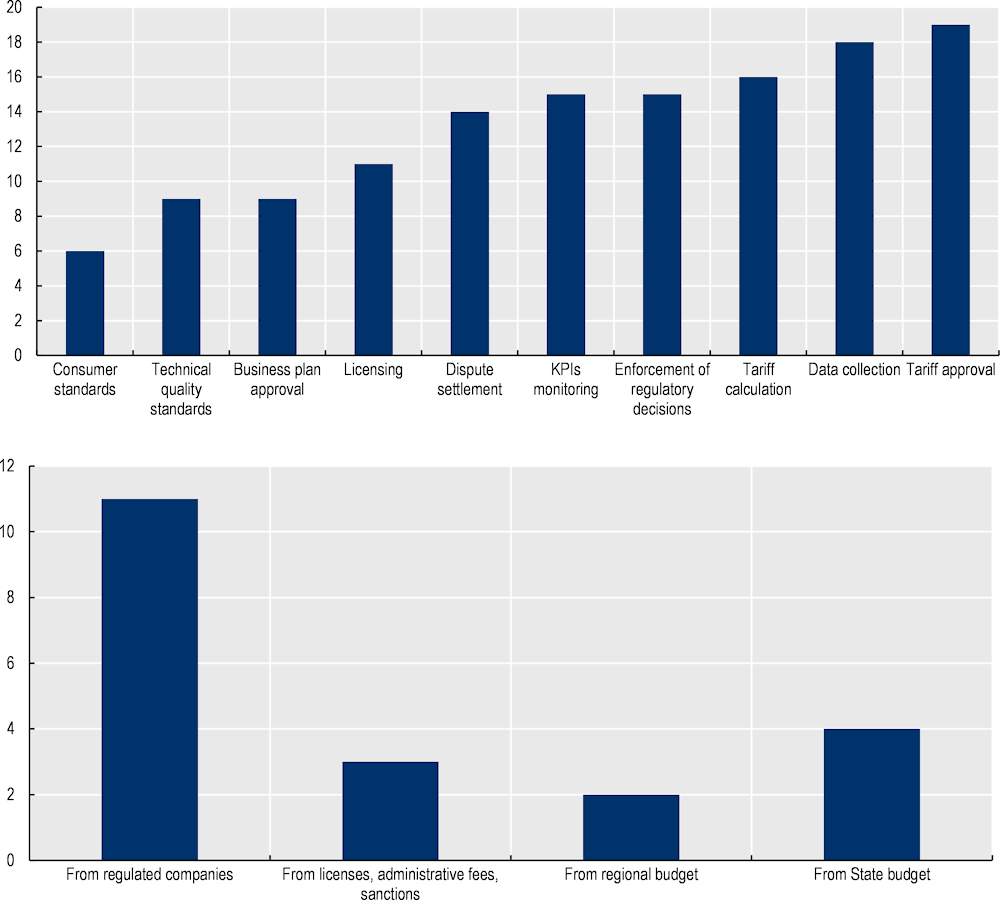

As a feature of stakeholder engagement, ANA should develop strategic partnerships as channels to share good practices to get to the core of the issues faced by sub-national authorities and provide insight and guidance where needed most. This, in turn, can help with the building of capacity. Through building capacity, ANA can also influence the relationship with consumers by empowering service providers to communicate better with the end-user (current or potential) (Figure 3.6). Note that unserved (potential) customers often lack voice in regulatory processes since they are usually the most vulnerable populations. ANA can provide incentives that help agencies address the long-term impacts of current policies.

Figure 3.6. Stakeholder process triangle

As a particular characteristic of the Brazilian situation, ANA should also rethink its strategic relationship with the unions, associations, local regulatory agencies, public companies, etc. as component stakeholders of the sub-national authorities. Resistance to change from staff working in sub-national authorities or service providers can be exacerbated by the wider economic context (such as the current COVID-19 crisis) and fears over job loss. At ESCOSA, it is not unusual for the regulators to include a wide range of stakeholders in their formal engagement strategy. The advantage of engaging with a wide base of stakeholders is not only to enhance understanding of and compliance with the rules and regulations, but also to raise awareness of the activities of the regulator and increase public acceptance. Of course, establishing a track record of successful initiatives is crucial for the creation of trust among the citizenry.

Moreover, WSS is a capital-intensive and monopolistic sector, with important market failures. Thus, it is important for ANA to ensure that relevant stakeholders within this system of multi-level governance (including other federal regulators, federal and local governments) are continuously appraised of the regulatory developments in the sector. This means that stakeholder engagement and communication strategy is not only defined for the short term. Rather, it is advised to build and maintain a long-term relationship and culture of continual coordination, so that the objectives stated in the new Sanitation Law are achieved over the next decade.

In addition, the reality of the new framework is that, on one hand, the rules developed under the reference standards will be numerous and complex, recognising various inter-dependencies. On the other hand, ANA will have a high number of sub-national authorities whose regulation needs to be reviewed. This means that ANA will be disadvantaged in terms of knowledge and access to information. For this, a different approach to stakeholder engagement might need to be considered: like the high-level pacts with governing actors referred to in “Achieving role clarity”, there is the possibility of creating such mechanisms with the service providers. These mechanisms are akin to a “moral contract”, a commitment between the regulator and the regulated entities to work together in a spirit of trust, cooperation and open communication – with the aim to provide quality service to consumers and achieve agreed objectives (ESCOSA, 2000[23]). The benefits of a high-level pact with service providers are a less adversarial relationship, improved use of resources, better planning, and improved productivity, all of which lead to improved quality of service. ESCOSA used high-level pacts with the industry, which were also accompanied by a joint review procedure – or “health checks”. These can come in the form of a questionnaire that assesses the robustness of the relationship, followed by open discussion in which results are discussed and possible solutions for deficiencies in the relationship are put forward by both parties.

In sum, effective stakeholder engagement will rely on several key elements:

Strengthening the stakeholder engagement strategy internally at ANA, and using OECD guidance to educate and build expectations with external stakeholders on matters shared for consultation.

Rethinking ANA’s strategic relationship with the groups not usually engaged (for instance unions, or unserved consumers), and building these relationships keeping in mind the current economic context and the specific challenges that these groups might encounter.

Keeping continuous dialogue with stakeholders, so all key players (including the federal government, sub-national authorities, consumer groups and private providers) are apprised of developments in the sector as they happen and there is a “no surprise” relationship among the sector actors.

Decentralising to achieve better regulatory outcomes

A key opportunity provided by the new legislative framework is its provision for the creation of regional units (which should include at least one metropolitan area).2 This allows for changes to be driven and implemented at a higher level than before, as sub-national authorities will be empowered to develop initiatives and attract investment at the regional rather than municipal level as was the case before the legislative reform.3 The regionalisation is designed to serve a dual role: (1) redistributing funds from wealthy to poorer areas, (2) achieving economies of scale through the implementation of larger-scale projects. According to the new Sanitation Law, it is within the remit of ANA to promote the regionalisation of service provision.4 This will be done through the development of reference standards and regulations.

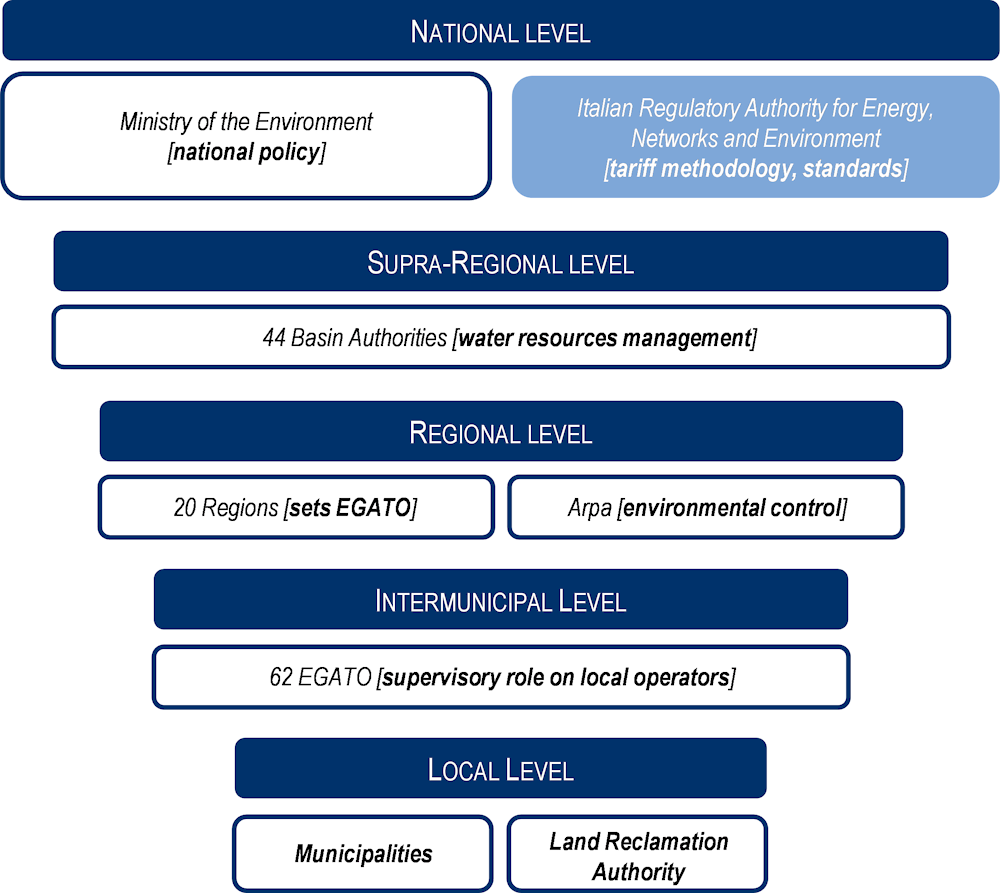

The understanding is that the regionalisation is not yet determined, but that it will consider geographical and water basin landscapes rather than only political regional boundaries. In the context of Brazil, the process of regionalisation for the purposes of implementing the new WSS policy is important, as it can allow for the regulatory model to be put into the local context, and thus target specific needs of each region. The Brazilian case is very similar to Italy, where regionalisation was implemented in WSS since 1995 (Box 3.6).

Box 3.6. Regionalisation in Italy: ARERA case study on territorial aggregation by uniform catchment areas

In Italy, the regulator for energy, networks and environment, ARERA, is the independent authority that, since 1996, sets tariffs and service quality standards. ARERA also monitors their compliance and enforces the standards through penalties and rewards within the national legislative environmental framework. The regulatory competencies were initially designed to the break monopoly in gas and electricity transmission and distribution services, and were prompted by the liberalisation process in the energy sector and by EU legislation to reinforce the internal energy market. In 2012, these were extended by law to water and wastewater utility services to better implement national water policies set by the Italian government.

In terms of water sector governance, Italy introduced the concept of Optimal Territorial Entities (Ambiti Territoriali Ottimali, ATO) in 1994. These are single catchment areas defined within each of the 20 Italian regions. Each ATO is governed by an assembly formed of representatives of all the municipalities included in its jurisdiction, which takes fundamental decisions on the governance of the sector, such as:

defining criteria to select service suppliers, according to EU laws (competition for the market)

coordinating with service suppliers to collect and validate data required to set local tariffs, according to the methodology defined by ARERA at the national level

defining objectives to be achieved and draft business plans to be approved by ARERA

monitoring of the realisation of planned investment.

The progressive reduction in the number of ATOs in the past years, combined with the effects of ARERA’s regulation, has reduced the extreme fragmentation of water services. Therefore, the number of operators decreased from more than 8,000 in the late 1990s to fewer than 2,100 today.

More specifically, ARERA’s regulation has promoted:

horizontal integration by creating economic incentives for the merger of operators within each ATO, and thus leading to economies of scale

vertical integration of different water services (potable water, sanitation and sewage treatment) into a single service for economies of scope.

Figure 3.7. Multi-level water governance in Italy

Regions decide which municipalities are aggregated in ATOs, with no involvement from the government or the national regulator. The Governing Entity of the ATO takes the decision on whether the service supplier should be selected through a tender (for fully private suppliers), or supplied in-house (for public suppliers) or by a public-private partnership (with the private partner selected through a tender). The local tariffs are approved by ARERA after a compliance check against the national tariff methodology, also defined by ARERA.

Source: OECD/ANA (2019-21[5]), “Water Governance Workshops”; Official Gazette of the Italian Republic (1994[24]), Law n. 36/1994 (Galli Law), https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1994/01/19/094G0049/sg.

In sum, to achieve the regionalisation objectives of the new law:

ANA should work with the other relevant federal authorities for the successful definition and implementation of the regionalisation objectives of the new Sanitation Law, since ANA will be in the position of having a “helicopter view” of the WSS status quo and emerging opportunities.

ANA should devise and promote policies which incentivise sub-national authorities to pursue investment projects from a regional, rather than local viewpoint. Particular attention should be given to the professionalisation of both regulators and operators.

Planning infrastructure and involving the private sector in WSS

OECD research shows that regulation plays an important role in investment through effects on determining the return on investment as well as ensuring efficient use and expansion of infrastructure through the effects of pricing (Cette, Lecat and Ly-Marin, 2017[25]) (OECD, 2017[26]). In particular, barriers to entry are found to influence investment negatively, and that regulatory independence is shown to boost investment when combined with incentive-based regulation.

In addition, the Survey on the Governance of Water Regulators (Figure 3.8) shows that increasing investment is a core part of the regulatory functions among water regulators. This is in line with the newly bestowed mandate of ANA.

Figure 3.8. Core regulatory functions carried out by water regulators

Note: Based on OECD Survey on the Governance of Water Regulators (2014)

Source: OECD (2015[14]), The Governance of Water Regulators, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264231092-en.

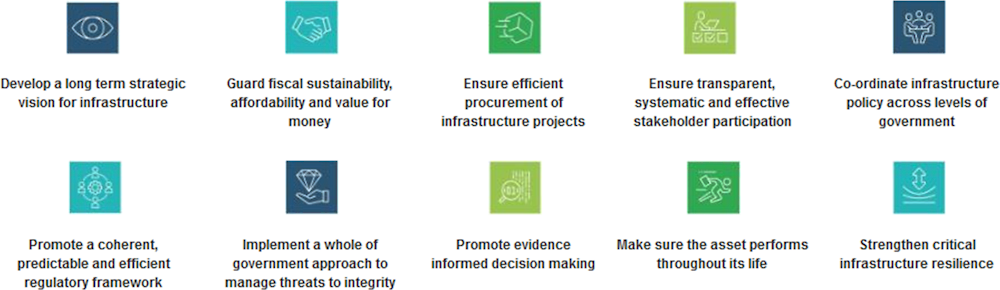

The Recommendation on the Governance of Infrastructure (OECD, 2020[27]), adopted by the OECD Council in July 2020, provides countries with practical guidance for efficient, transparent and responsive decision-making processes in infrastructure investment. This comes in the form of 10 specific recommendations that are interdependent (Figure 3.9). The recommendations can be adapted to the Brazilian context as they support a whole-of-government approach and cover the entire life cycle of infrastructure projects, putting special emphasis on regional, social, gender and environmental considerations. A key feature is the promotion of a coherent, predictable and efficient regulatory network.

Figure 3.9. OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Infrastructure

Source: OECD (2020[27]), Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Infrastructure, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0460.

The Brazilian government has set targets for investment in WSS through the National Sanitation Plan. However, in addition to long-standing fiscal constraints, there is the newly emerged additional challenge which stems from the COVID-19 crisis. Therefore, infrastructure investment and delivery are important tools for the economic and social recovery efforts in the foreseen economic context. In practice, and in harmony with the objectives of the national policy on WSS, ANA needs to look at creating long-term incentives to attract private and foreign investors and, in some cases, to encourage existing companies to continue the provision of current services.

In addition to the guidelines provided by the legal framework and international practice, Brazil already has experience in opening network sectors to private investors. This happened in the electricity sector from the 1990s, and ANA should strive to learn from that experience (i.e., through research of privatisation policy and contracts, with knowledge sharing from the electricity regulator, Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica). There is scope to create forums for cross-fertilisation between Brazilian sector regulators and their experiences and roles in the implementation of major reforms and ambitious policy goals.

Box 3.7. Lessons from ARERA about increasing private sector investment

Private involvement in WSS in Italy has been a controversial topic due to the public perception that water is a public good. This materialised in 2011 through a national referendum that ended mandatory competitive tendering for water concessions and ended the explicit requirement that firms receive a fair rate of return when water tariffs were set. In this context, the role of the national regulator, ARERA, became instrumental in the incentivisation of water infrastructure investments.

Currently, three main functions influence investment through ARERA’s regulatory approach:

1. ARERA has the power to approve economic and financial plans of single operators (received through the governing entity of the ATOs) and to ask for modifications in case of non-compliance with the tariff methodology. ARERA can also impose sanctions in case data is not received or correctly modified; this increases the quality of information provided to the regulator and promotes stability in the water sector.

2. Through a single national tariff methodology (divided into variants that consider the diverse economic and financial situation of Italian regions), ARERA promotes efficient infrastructure and management planning, resulting in positive effects on investment development and infrastructure value.

3. ARERA’s rules are defined every four years, with an update every two years. This brings certainty and stability in the sector, elements fundamental to attracting investment capital. This is done based on observed and measured costs, not as a consequence of political interference. It also lowers the risk of reviewing regulatory schemes, hence increasing the capability to program future investments.

As a result of ARERA’s regulatory approach, the level of investment in Italy has constantly risen: investments reached EUR 38.7/inhabitant in 2017, with a total increase of 24% from 2012 to 2018. For 2018-19, investments reached EUR 44.6/inhabitant.

Between 2016 and 2019, investment expenditure (including the availability of public funds) amounted to EUR 11.9 billion (EUR 2.2 billion in 2016, EUR 2.8 billion in 2017, EUR 3.5 billion in 2018 and EUR 3.4 billion in 2019).

Source: OECD/ANA (2019-21[5]), “Water Governance Workshops”; Official Gazette of the Italian Republic (2017[28]), Law n.205/17, https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/12/29/17G00222/sg; ARERA (2019[29]), Annual Report, https://www.arera.it/it/inglese/annual_report/relaz_annuale.htm#.

The planning of infrastructure investment will be reliant on several key elements:

The responsibility of ANA on the creation of reference standards should consider policies that incentivise the sub-national authorities to seek private investment. In this process, ANA can learn from other national agencies, such as the electricity regulator.

In the context of ANA and of the new Sanitation Law, the OECD Recommendations on the Governance of Infrastructure can be applied using the following elements:

identifying policy goals, and evaluating whether regulation is necessary and how it can be most effective and efficient in achieving those goals

considering means other than regulation and identifying the trade-offs of the different approaches analysed to identify the best approach

supporting coordination between supranational, national and sub-national regulatory frameworks

providing evidence-based tools for regulatory decisions, including stakeholder engagement, economic, fiscal, social and environmental impact assessment, audit and ex post evaluation

conducting systematic reviews of existing regulation relevant to infrastructure, including consideration of costs and benefits, to ensure that regulations are up to date, cost justified, cost effective and consistent, and deliver the intended policy objectives

promoting good governance of regulatory agencies to ensure sustainable tariff setting, overall regulatory quality and confidence in the market, and contribute to the overall achievement of policy goals (e.g., independence, transparency, accountability, scope of action, enforcement, capacity and resourcing).

Understanding finance providers’ perspectives

In addition to understanding the investment needs of specific regions, ANA and the other relevant actors in the WSS sector (including government) need to understand what specifics are needed by private investors and finance providers in the process of designing of a regulatory framework aimed at increasing incentives for private investment. For instance, key questions such as contracts funding, incentives of operators and sub-national authorities to keep to the terms of the agreement in the long term (30 years or more), and the availability of adequate financial products need to be considered.

Furthermore, as mentioned in the sub-section on Planning infrastructure and involving the private sector in WSSPlanning infrastructure and involving the private sector in WSS above, ANA’s regulations and reference standards need to influence operators to seek private funding and not just look at sources of government funding, with a view to covering long-term costs and increasing investment efficiency.

Regulatory stability is an expected outcome from the issuance by ANA of reference standards and harmonisation of regulation among the sub-national authorities. This is a key characteristic that private investors look for. Therefore, for the sanitation policy to achieve its objective of increasing private access to WSS, there needs to be commitment to maintaining a harmonised framework and applying it to the new contracts. Otherwise, there is the risk that investors lose faith in the new framework and private capital will not be invested.

Public acceptance of private sector involvement

Public acceptance of private involvement in the WSS can present two issues. On one hand, as one of the international experts highlighted in the workshop, a feature of the current situation is that local politics is involved in the operation and provision of WSS by municipalities. Change of this status quo can be difficult, and ANA should work with the local authorities to highlight the benefits for consumers which arise from further investment and private sector involvement. As Professor Berg noted in the slide deck for workshop week 19-22 October, citizens “need to be confident that the system works for them”.

On the other hand, there is a risk that there will be an initial cultural aversion by consumers to any increased private management of water services, stemming from the perception of water resources as a public good. Public acceptance of private sector involvement is important, as citizens’ perceptions are fundamental to the accountability of regulation. ANA can look at several solutions. For instance, a dedicated economic regulator in charge of guaranteeing the public interest, such as Ofwat in England and Wales (UK), can achieve public confidence in a completely privatised industry, and ANA can look to position itself as being such a guarantor. Alternatively, public confidence might be maintained by ensuring transparent management arrangements with stakeholder involvement and a clear political lead in strategic decisions (for instance, by ensuring controlling public authority participation in the capital of any public-private partnership). Finally, learning from example at WICS, a collaborative approach with the wider public, can be achieved through a consultation process that puts the customers and communities at the heart of the process (this can be done through the form of customer consultation panels, consumer forums, etc.).

The following elements need to be considered:

Dialogue among the relevant stakeholders, especially the providers of private finance, is needed to understand the challenges that the current framework poses for investors. This would highlight whether the financial framework is suited for the purposes and needs of WSS investment, and could flag further areas beyond WSS policy that the federal government needs to consider.

The harmonisation and stability of the regulatory and WSS contractual framework brought by ANA’s reference standards will be key in attracting new investment.

Public acceptance of private investment in WSS will be noted both at the level of service provision, as well as by the end consumers. ANA should work on raising awareness among these stakeholder groups about the short- and long-term benefits of private investment.

References

[2] ANA (2021), Homepage, Agência Nacional de Águas, https://www.ana.gov.br/eng/ (accessed on 2021 November 20).

[12] ANA (2020), Agenda regulatória 2020-2021-2022.

[29] ARERA (2019), Annual Report, https://www.arera.it/it/inglese/annual_report/relaz_annuale.htm#.

[25] Cette, G., R. Lecat and C. Ly-Marin (2017), “Long-term growth and productivity projections in advanced countries”, OECD Journal: Economic Studies, Vol. 2016/1, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_studies-2016-5jg1g6g5hwzs.

[17] EC (2020), EU Water Legislation - Fitness Check, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/fitness_check_of_the_eu_water_legislation/index_en.htm.

[19] ESCOSA (2021), Strategy 2021-2024, Essential Services Commission of South Australia, https://www.escosa.sa.gov.au/about-us/strategic-plans.

[6] ESCOSA (2020), Regulators Working Group, Essential Services Commission of South Australia, https://www.escosa.sa.gov.au/industry/water/retail-pricing/sa-water-regulatory-determination-2020/regulators-working-group.

[23] ESCOSA (2000), Speech by Lewis W. Owens at the SA Power Briefing, Essential Services Commission of South Australia.

[13] Government of Brazil (2018), Diário Oficial da União - Portaria nº 193, de 3 de Julho de 2018, http://www.in.gov.br/materia/-/asset_publisher/Kujrw0TZC2Mb/content/id/28503558/do1-2018-07-04-portaria-n-193-de-3-de-julho-de-2018-28503542 (accessed on 17 June 2020).

[18] Hodges, S. (2017), Ethical Business Practice and Regulation, Hart Publishing.

[30] OECD (2020), OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Infrastructure, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/gov/infrastructure-governance/recommendation/.

[22] OECD (2020), “Public consultation on the draft OECD Best Practice Principles on Stakeholder Engagement in Regulatory Policy”, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/public-consultation-best-practice-principles-on-stakeholder-engagement.htm.

[27] OECD (2020), Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Infrastructure, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0460.

[8] OECD (2018), OECD 2018 Database on the Governance of Sector Regulators, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/regreform/regulatory-databases-and-indicators.htm.

[15] OECD (2018), OECD Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections Toolkit, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303959-en.

[31] OECD (2018), The Governance of Regulators, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/governance-of-regulators.htm.

[26] OECD (2017), OECD Journal: Economic Studies, OECD Publishing, OECD, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/oecd-journal-economic-studies_19952856.

[11] OECD (2017), Report on the Governance of Drinking Water and Sanitation Infrastructure in Brazil, https://www.ana.gov.br/todos-os-documentos-do-portal/documentos-sas/arquivos-cobranca/documentos-relacionados-saneamento/governance-of-ws-infrastructure-in-brazil_final.pdf.

[10] OECD (2015), OECD Principles on Water Governance, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/OECD-Principles-on-Water-Governance-en.pdf.

[14] OECD (2015), The Governance of Water Regulators, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264231092-en.

[4] OECD (2015), Water Resources Governance in Brazil, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264238121-en.

[7] OECD (2014), The Governance of Regulators, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209015-en.

[16] OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

[5] OECD/ANA (2019-21), “Water Governance Workshops”.

[28] Official Gazette of the Italian Republic (2017), Law n.205/17, https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/12/29/17G00222/sg.

[24] Official Gazette of the Italian Republic (1994), Law n. 36/1994, https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1994/01/19/094G0049/sg.

[1] Official Journal of the Union (2020), Law 14.026 of 15 July 2020, https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/lei-n-14.026-de-15-de-julho-de-2020-267035421.

[3] SNIS (2018), The National Sanitation Information System, Sistema Nacional de Informações sobre Saneamento, http://www.snis.gov.br/painel-informacoes-saneamento-brasil/web/painel-setor-saneamento.

[9] WAREG (2021), Water Regulatory Governance across Europe, https://www.wareg.org/documents/water-regulatory-governance-around-europe/ (accessed on 5 January 2022).

[20] WICS (2020), Strategic Review of Charges, https://wics.scot/publications/price-setting/strategic-review-charges-2021-27/approach/2021-27-methodology-refinements.

[21] WICS (2020), Strategic Review of Charges 2021-27 – Draft Determination, https://wics.scot/publications/price-setting/strategic-review-charges-2021-27/determinations/2021-27-draft-determination.

Annex 3.A. Action plan

The tables summarise the main actions presented in Chapter 3.

Annex Table 3.A.1. Making water and sanitation regulation in Brazil more effective

|

Achieve role clarity |

Clear leadership from the Ministry of Regional Development and actions from the Ministry of Finance, ANA, sub national authorities, service providers, civil society actors and consumers. The successful implementation of the reform rests on the collective effort of all actors and role clarity of each entity is important for implementation |

|

The relevant stakeholders should determine their ex ante “definition of success”. More specifically, this should include realistic and attainable short-term and long-term objectives and milestones of the stakeholders, as well as convergence areas for coordination among the stakeholders. |

|

|

ANA should build on the previous experience of the 2015 resources management pact in order to cement the basis of a regulatory scheme that is in sync with the objectives of other actors in the context of the new Sanitation Law. |

|

|

Coordinate effectively |

ANA needs to engage with sub-national authorities effectively, so that all parties have a shared understanding of the law and the regime. For this, the OECD Principles on Water Governance as applied to the Brazilian context need to be considered. More specifically, there needs to be horizontal coordination at federal level, so that the various programmes for grant funding are aligned, there is a need for consolidation in approach among the federal authorities, and quality control needs to be implemented in a harmonised manner. |

|

ANA can facilitate a dialogue with other state authorities, including the sub-national regulators, so that the responsibilities of each agency are understood. Beyond increasing awareness, the sector actors need to be committed to the delivery of the new framework. |

|

|

Define an adequate transition period and manage expectations from ANA |

An assessment by ANA of the current status quo across all sub-national authorities, as well as an appraisal of current adequate standards and practices at some sub-national authorities. |

|

ANA should take a clear stance in managing short term expectations in relation to what can be delivered for the consumers and the sector in the next couple of years, as well as how the provision and contractual practicalities will be dealt with until the reference standards have been developed and implemented. |

|

|

Build adequate human and technical capacities |

It is advisable that ANA not only focus on the substance of the regulatory reform, but also on the internal management and resources needed for the delivery. For instance, ANA will need to rethink its skills set and add more legal, economics and data analytics specialists to an established engineering-focused staff base. |

|

ANA should be mindful of the additional financial resources needed to carry out the mandate bestowed by the new Sanitation Law, as well as consider how the increased financial burden will be resourced, and how this might affect its independence in the long term. |

|

|

Achieve effective oversight and enforcement |

ANA should ensure that the rules are enforced regarding the allocation of funding for those authorities that do not follow the reference standards. This demonstrates robustness of the framework and sets the tone on how the new policy is to be pursued. |

|

Even without enforcement powers, a suite of soft tools can be implemented by ANA, as follows:

Collecting data and reporting. |

|

|

ANA should consider the development of alternative, behaviourally driven approaches to the development of regulation, such as Ethical Business Regulation, which implies a collaborative approach and dialogue between market actors, their stakeholders and public officials, based on a shared ethical approach. |

|

|

Ensure effective stakeholder engagement |

Strengthen the stakeholder engagement strategy internally at ANA, as well as use OECD guidance to educate and build expectations with external stakeholders on the matters that will be shared for consultation. |

|

Rethink ANA’s strategic relationship with groups not usually engaged (e.g., unions, or unserved consumers), and build these relationships keeping in mind the economic context and specific challenges that these groups might encounter. |

|

|

Keep a continuous dialogue with the relevant stakeholders for all key players (including federal government, sub‑national authorities, consumer groups and private providers) to be apprised of the developments in the sector as they happen, so that there is a “no surprise” relationship among the sector actors. |

|

|

Decentralise to achieve better regulatory outcomes |

ANA should work with the other relevant federal authorities for the successful definition and implementation of the regionalisation objectives of the new Sanitation Law since ANA will be in the position of having a “helicopter view” of the WSS status quo. |

|

ANA should devise and promote policies which incentivise sub-national authorities to pursue investment projects from a regional, rather than local perspective. |

|

|

Plan infrastructure and involve the private sector in WSS |

The key responsibility of ANA on the creation of reference standards should be delivered as to consider policies that incentivise the sub-national authorities to seek private investment. In this process, ANA can learn much more from other national agencies, such as ANEEL (the electricity regulator). |

|

In the context of ANA and of the new Sanitation Law, the OECD Recommendations on the Governance of Infrastructure can be applied using the following elements: a. identifying policy goals, and evaluating whether regulation is necessary and how it can be most effective and efficient in achieving those goals b. considering means other than regulation and identifying the trade-offs of the different approaches analysed to identify the best approach c. supporting coordination between supranational, national and sub-national regulatory frameworks d. providing evidence-based tools for regulatory decisions, including stakeholder engagement, economic, fiscal, social and environmental impact assessment, audit and ex post evaluation e. conducting systematic reviews of existing regulation relevant to infrastructure, including consideration of costs and benefits, to ensure that regulations are up to date, costs are justified, effective and consistent, and that they deliver the intended policy objectives promoting good governance of regulatory agencies to ensure sustainable tariff setting, overall regulatory quality, and greater confidence from the market, and contribution to achievement of policy goals (e.g., independence, transparency, accountability, scope of action, enforcement, capacity and resourcing). |

|

|

Understand finance providers’ perspectives |

A dialogue among relevant stakeholders, especially the providers of private finance, is needed to understand the challenges that the current framework poses for the investors. This would highlight whether the financial framework is fit for the purposes and needs of WSS investment, and could flag areas beyond WSS policy that the federal government needs to consider. |

|

The harmonisation and stability of the regulatory and WSS contractual framework brought by ANA’s reference standards will be key in attracting new investment. |

|

|

Public acceptance of private investment in WSS will be noted both at the level of service provision, as well as by the end consumers. ANA should work on raising awareness to these stakeholder groups on the short- and long-term benefits of private investment. As Professor Berg noted in the slide deck for workshop week 19-22 October, the citizens “need to be confident that the system works for them”. |

Notes

← 1. Law 14.026 of 15 July 2020, Article 11-B.

← 2. Article 8, Paragraph 2, Law 14.026 of 15 July 2020: “For the purposes of this Law, regional basic sanitation units must be economically and financially sustainable and preferably include at least 1 (one) metropolitan region, and may be established by sanitation service granting authorities”.

← 3. Article 13, Law 14.026 of 15 July 2020.

← 4. Article 4-A, Paragraph 3V, Law 14.026 of 15 July 2020.