This chapter introduces the main issues and concepts underlying data governance. It explores the roots of “data” – from the first attempts to record information on cave walls to the emergence of computers in the 1940s. In the context of the OECD Project on Data Governance for Growth and Well-being, it defines “data” and “data governance”, and examines ways to balance benefits and risks related to data, including to rights and interests.

Going Digital to Advance Data Governance for Growth and Well-being

1. Introduction

Abstract

Humans have recorded information for millennia. The first known attempts were found in paintings in ochre and dirt, traced onto the walls of caves over 40 000 years ago (Marchant, 2016[1]). About 35 000 years later, our ancestors invented writing (Daniels, 1996[2]). After writing appeared on materials like papyrus and clay, the invention of paper in approximately 1AD enabled books to become the main repository of human knowledge for approximately 2 000 years (Tsien, 1985[3]). This trend was magnified by the development of the printing press in 1436 (Wolf, 1974[4]).

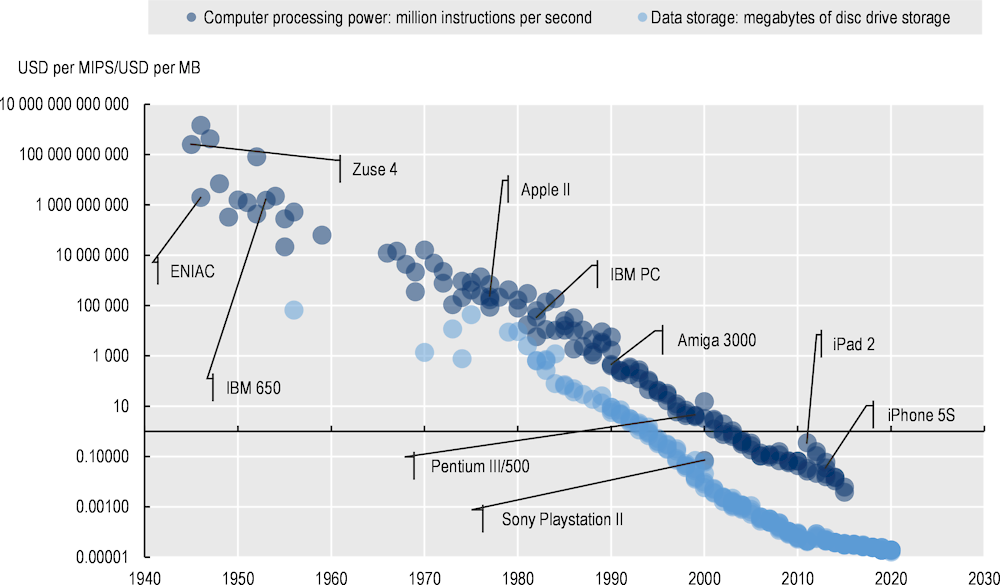

The information landscape changed with the arrival of the transistor in 1947 and the development of the integrated circuit in 1956 (Bell Labs, 2022[5]). Together, these two inventions paved the way for modern digital technologies, which are increasingly ubiquitous across the OECD and beyond. Mobile phones are used to access digital services that let us connect, transact and organise our lives, while digital sensors proliferate through infrastructure and production systems. Each of these digital interactions leaves a trail of data, which can be cheaply stored and processed (see Figure 1.1).

The proliferation of digital technologies has enabled a leap forward in the ability of humans to generate, collect and process information. Before the digital age, recording information took active human effort in some form, whether through observation or recording. In contrast, many sensor-equipped devices, also known as the “Internet of Things”, collect data automatically, including as a by-product of an economic or social interaction. Through the Internet and communication infrastructures, data can be easily and quickly shared between other connected users and machines.

Figure 1.1. Cost of computer processing power and data storage, 1940-2020

Notes: MB: megabyte; MIPS: million instructions per second. Costs are expressed in 2020 prices and are deflated using the consumer price index (US Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2022[6]).

Source: OECD (2022[7]), based on data collected by Moravec (2022[8]), “Processor list”, https://frc.ri.cmu.edu/~hpm/book97/ch3/processor.list.txt and McCallum (2021[9]), “Memory Prices 1957+”, https://jcmit.net/memoryprice.htm.

This report develops an understanding of the main issues and concepts underlying data governance debates to foster a holistic and coherent approach to data governance, domestically and across borders. A common conceptual grasp of data and data governance is key to this understanding (see Box 1.1).

Box 1.1. What is data? What is data governance?

The OECD Project on Data Governance for Growth and Well-being seeks to provide policy guidance to help reap the benefits of data, address related challenges and foster a holistic and coherent approach to data governance. In the context of this report, “data” refer to recorded information in structured or unstructured formats, including text, images, sound and video. Data can be in any format, including analogue formats like paper, or emerging quantum forms like qubits. However, the rise of digital technologies has enabled the growth and policy relevance of digital data, namely information stored by a computer in binary format. Almost every aspect of the online experience, including a website or a banner advertisement, is data. Data in digital formats are characterised by their ability to be processed and analysed by digital technologies. Throughout this report, the term “data” will mean digital data unless otherwise stated.

This working policy definition of data can refer to one data point; several data points in a given dataset; one dataset; or many datasets. Put differently, the term “data” in this report does not carry a specific connotation about their volume. This definition does not refer to how data were collected, namely whether they were inferred, observed or volunteered, or any specific data type.

Finally, it is necessary to make a distinction between the definition of data used in this report, and the evolving understanding of data in the statistical community. Drawing on sources of statistical best practice, the OECD’s Statistics Portal defines data as “characteristics or information, usually numerical, that are collected through observation”. In collaboration with the international statistical community, the OECD is developing a robust definition of data for statistical and national accounting purposes. For example, the OECD participates in an Intersecretariat Working Group on National Accounts Advisory Expert Group. It recently proposed the following definition of data: “Information content that is produced by accessing and observing phenomena; and recording, organizing and storing information elements from these phenomena in a digital format, which provide an economic benefit when used in productive activities.” While the statistical definition of data is evolving, its proposed use is intended to help establish which costs should be captured in determining the value of data and data assets in the System of National Accounts, as explored in Chapter 3.

In the context of the OECD Project on Data Governance for Growth and Well-being, “data governance” refers to diverse arrangements, including technical, policy, regulatory and institutional provisions, that affect data and their creation, collection, storage, use, protection, access, sharing and deletion, including across policy domains and organisational and national borders. Efforts to govern data take many forms. They often seek to maximise the benefits from data, while addressing related risks and challenges, including to rights and interests.

Sources: OECD (2021[10]), Recommendation of the Council on Enhancing Access to and Sharing of Data, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0463; OECD (2020[11]), “Data”, https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=532; ISWGNA (2022[12]), Recording of Data in the National Accounts, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/RAdocs/DZ6_GN_Recording_of_Data_in_NA.pdf.

Chapter 2 examines how data have emerged as a strategic asset that can transform lives and markets and confer economic and market power, particularly for the few firms that use data to their full potential. Nevertheless, this opportunity carries risks, including to privacy, data protection rights and intellectual property rights. As the stakes of data use and misuse have increased, data-related policies have emerged in various policy domains and contexts but are rarely cross-cutting or co-ordinated.

A common understanding of data is necessary for effective, integrated policy making. Chapter 3 outlines the characteristics of data that can challenge conventional measurement methodologies. It also highlights how data are underpinned by digital technologies and an evolving technological landscape. These characteristics make data a uniquely challenging subject for policy makers. Policies and institutions that pre-date the data-driven era must adjust to manage complex trade-offs between openness and control, overlapping interests and misaligned incentives for data collection and use.

Data’s main potential for growth and well-being relies on increased data openness, but sharing data also increases the risk of misuse. Better and more co‑ordinated policies are needed to help navigate these tensions and maximise the benefits of data governance for growth and well-being, as outlined in Chapter 4 of this report. The OECD is well placed to support governments in these efforts.

References

[5] Bell Labs (2022), 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics, https://www.bell-labs.com/about/awards/1956-nobel-prize-physics/#gref.

[2] Daniels, P. (1996), The World’s Writing Systems, Oxford University Press, New York, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED418582.

[12] ISWGNA (2022), Recording of Data in the National Accounts, Intersecretariat Working Group on National Accounts, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/RAdocs/DZ6_GN_Recording_of_Data_in_NA.pdf.

[1] Marchant, J. (2016), “A journey to the oldest cave paintings in the world”, Smithsonian Magazine, No. 1/12, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/journey-oldest-cave-paintings-world-180957685/.

[9] McCallum, J. (2021), “Memory Prices 1957+”, webpage, https://jcmit.net/memoryprice.htm (accessed on 10 January 2022).

[8] Moravec, H. (2022), “Processor List”, webpage, https://frc.ri.cmu.edu/~hpm/book97/ch3/processor.list.txt (accessed on 20 January 2022).

[7] OECD (2022), “Measuring the value of data and data flows”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 345, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/923230a6-en.

[10] OECD (2021), Recommendation of the Council on Enhancing Access to and Sharing of Data, OECD/LEGAL/0463, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0463.

[11] OECD (2020), “Data”, Glossary of Statistical Terms, https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=532 (accessed on 16 June 2022).

[3] Tsien, T. (1985), “Paper and Printing”, in Science and Civilisation in China, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Cambridge University Press.

[6] US Bureau of Economic Analysis (2022), “Personal Consumption Expenditures”, Chain-type Price Index, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis (FRED), https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DPCERG3A086NBEA.

[4] Wolf, H. (1974), Geschichte der Druckpressen, Interprint, Frankfurt/Main.