Data have emerged as a strategic asset that can transform lives and markets and confer economic and market power. This chapter outlines why data and their role as a source of value and potential competitive advantage have emerged as a priority for individuals, organisations and nations. At the same time, it highlights risks associated with data collection and use. Noting that the stakes of data use and misuse have increased, this chapter discusses the emergence of data-related policies in various policy domains and contexts.

Going Digital to Advance Data Governance for Growth and Well-being

2. Data as a strategic asset: The fundamental shift in their use, misuse and appreciation

Abstract

2.1. Data use is transformational for economies and societies

Data are a strategic asset due to their potential benefits for economies and societies. Data use is transformational through two main channels. First, insights gleaned from processing and analysing data can reveal patterns and relationships that enable better, evidence-based decision making. For consumers, this might mean making better and more empowered purchase decisions. For firms, data can be considered an input to production, including in combination with other, more traditional economic factors like labour or land. Second, data can bridge gaps between and among consumers and producers, or governments and citizens, facilitating new transactions and creating new markets. For example, the collection and sharing of data can enable more transparency between unknown third parties online. This can enable them to overcome previous information asymmetries that may have inhibited a successful interaction or transaction.

Through these two channels, the use of data, including their transfer across borders, can improve individual well-being and address societal challenges, as well as boost innovation and productivity. Data hold great potential across many areas of economies and societies. This includes the areas of public service design and delivery; science, research and development; education system monitoring and improvement; territorial management, including for smart cities; consumer empowerment and protection; and global development progress and co‑operation (OECD, 2022[1]). Similarly, cross-border data flows play an enabling role for digital trade, including in the context of global value chain co-ordination (OECD, 2022[2]).

The COVID-19 crisis highlighted the growing importance of data to economies and societies, underscoring the role of data in responding to crises and societal challenges. The collection and use of data was crucial to almost all facets of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, an unprecedented amount of real-time and granular data was collected during the crisis (Paic, 2021[3]). For instance, data were fundamental to managing and improving health system performance, including better allocation of limited public health resources to fight the spread of the virus. Also, public bodies published open data and collaborated closely with the private sector. This enabled the co-design of services that citizens could use to better cope with the pandemic on a day-to-day basis (OECD and Govlab, 2021[4]).

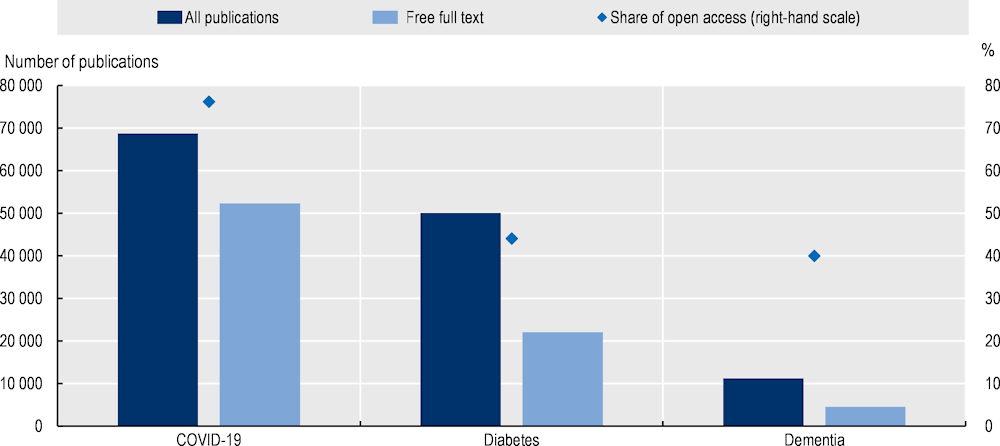

Figure 2.1. Open access of COVID-19, diabetes and dementia publications, January-October 2020

Source: OECD (2021[8]), OECD Science, Technology and Innovation Outlook 2021: Times of Crisis and Opportunity, https://doi.org/10.1787/75f79015-en.

Data were essential to trace the spread of the virus, including by tracking contacts of confirmed cases and enabling monitoring. In Korea, for example, geolocation data, surveillance camera footage and credit card records were used to trace coronavirus patients (OECD, 2020[5]). In Israel, geolocation data were used to identify people coming into contact with virus carriers. This enabled authorities to inform them to isolate immediately (OECD, 2020[5]).

Data and their governance are also crucial elements of the global science system. Data provide evidence that enables knowledge creation and discovery, including to improve medical treatments and save lives. In particular, access to research data from public funding can help enable basic research and foster innovation networks (OECD, 2020[6]). During the pandemic, open science policies removed obstacles to the free flow of research data and ideas, and accelerated the pace of research critical to combatting the disease (OECD, 2020[8]; 2022[1]; Paic, 2021[3]). An unprecedented number of scientific publications was made openly available, with research databases removing paywalls so the scientific community could quickly share COVID-19 related information (see Figure 2.1). The growing volumes of research data also spurred the uptake of artificial intelligence (AI), including AI and data mining tools, which helped advance efforts to develop vaccines and better understand the virus.

2.2. Data-driven business models, including platforms, are transforming markets

While data are of value in many contexts, firms are at the forefront of realising the potential of data in their operations. Data can drive innovation and efficiency improvements, for instance by enabling real-time monitoring of firm operations. Data can also be used to co‑ordinate business operations, including to manage supply chains and strengthen oversight. For example, in agriculture, sensor data from geocoded maps of fields can be linked with historical and real-time data on weather patterns, soil conditions, fertiliser usage and crop features, to optimise production (Jouanjean et al., 2020[9]). In manufacturing, streams of data from connected devices can be used to optimise operations and provide new or better after-sales services. Such data-enhanced business models create room for product differentiation, a key lever of competitiveness and performance for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (OECD, 2022[10]). Despite this significant potential and the ubiquity of data processing technologies across the OECD, there remains room for SMEs and lagging firms to use data and reap the benefits for economies and societies (OECD, 2021[11]; 2022[12]).

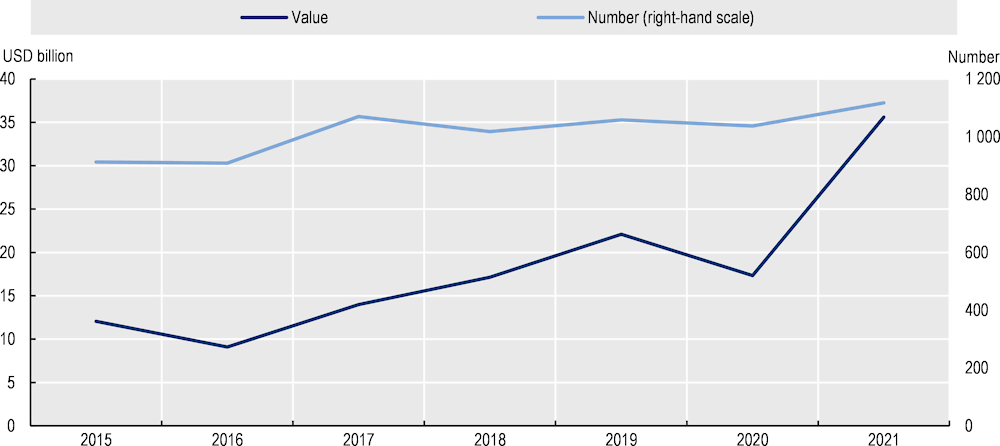

While some firms lag behind, the digital age has facilitated the rise of firms at the cutting edge of the technological frontier. Unlike firms whose operations are simply enhanced by data, some data-enabled firms rely on their ability to generate, collect and analyse data (Nguyen and Paczos, 2020[13]). For data-enabled firms, data are a critical input into their productive activities, and data or data-related tools may be among the most valuable assets they control. The most famous data-enabled firms are now household names across OECD countries, and have been among the largest firms in the world by capitalisation (Ker and Mazzini, 2020[14]). Markets increasingly value firms that can use data. Venture capital investments in “big data” firms, for example, have more than tripled since 2015 to reach USD 35.6 billion in 2021 (see Figure 2.2). Such investments reflect an evaluation of the long-term value of the data assets owned by these firms.

For firms, data have value to investors and strategic potential for innovative and market advantages. However, future returns from their generation and use may be uncertain. This can lead firms to view data systematically as a source of advantage that requires investment and protection. For example, firms may hoard data if sharing them exposes the firms to competition (Jones and Tonetti, 2020[15]). Alternatively, they may have no incentive to share data if they cannot privately capture the benefits of such an arrangement. Maximising the benefits of data to society by enabling and encouraging their wider use is thus a key concern of data governance frameworks (see Chapter 4).

Online platforms are examples of data-enabled firms at the frontier of markets and technological development. The core product of many prominent online platforms is a data-enabled service that connects multiple “sides” of a market, such as consumers, merchants and advertisers. The “matching” service offered by such online platforms is enabled by the quantity and quality of data available to them, which they often collect from individual interactions. Many popular online platforms offer products at zero price to at least one side of the marketplace. Meanwhile, they generate their primary revenues from advertising (targeted using data) or successful transactions (namely, a commission from a successful data-driven match), incentivising greater data collection (OECD, 2022[17]). Many global companies provide zero-price products and services (to at least one side) using this business model (OECD, 2022[17]).

Figure 2.2. Venture capital deals in big data firms worldwide, 2015-21

Source: OECD (2022[16]), “Measuring the value of data and data flows”, https://doi.org/10.1787/923230a6-en, based on Preqin Pro, http://www.pro.preqin.com/ (accessed 14 February 2022).

Platforms enjoy significant direct and indirect network effects where economies of scale benefit users on multiple sides of the market. In other words, as the number of users on one side increases, the value of the product to users on another side also increases. Because the marginal cost of adding an additional user to the platform can be close to zero, online platforms can rapidly scale up and expand their geographic coverage. This enables transactions between far-flung users that were previously impossible (OECD, 2022[17]; 2019[18]). As platforms scale up, so do their opportunities to gather data to improve their services. This potentially drives a feedback loop that could result in few players in a given market (also known as a “winner takes most” or “winner takes all” effect) (OECD, 2022[12]).

2.3. The shift in the nature and use of data introduces economic and social risks

As the significance of data to economies and societies has grown, so too have the potential harms associated with their use and misuse. In particular, the combination of the growing collection of data, and increased access and use of data analytics and related digital technologies, has created the potential for deliberate or accidental misuse of data.

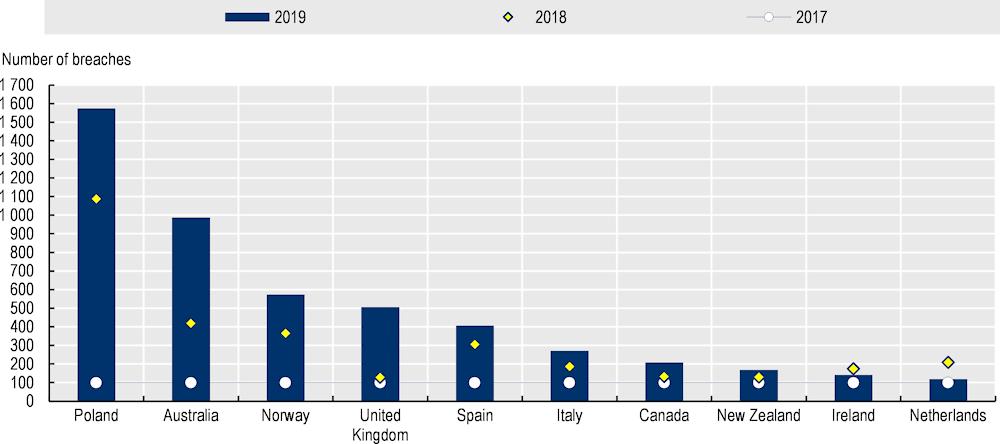

A key risk relates to the violation of privacy and personal data protection rights. Indeed, several OECD jurisdictions reported a general increase in the number of personal data breach notifications over two years (see Figure 2.3). Even where individuals and organisations agree on (and consent to) specific terms for data sharing and data re-use, including on the purposes for which the data should be re-used, there remains a significant level of risk that the data may end up being used differently, including by a third party. Issues of informed consent become more difficult in an environment where consumers often face information overload, and technologies like AI enable more unanticipated uses for data (OECD, 2022[19]). Similarly, data collection and processing might be less transparent or apparent. The ubiquity and discreteness of connected devices, for example, might sometimes mask that personal data are constantly collected. This collection can often occur without an easily accessible interface for user interaction and control (e.g. to set personal data gathering preferences) (OECD, 2021[20]).

Moreover, online businesses can control the “choice architecture” online to a greater extent than in an offline interaction or transaction. This can result in “dark commercial patterns” – business practices that use elements of digital choice architecture, especially in online user interfaces, that subvert or impair consumer autonomy, decision making or choice (OECD, 2022[21]). Such practices often deceive, coerce or manipulate consumers and are likely to cause direct or indirect consumer detriment in various ways. However, it may frequently be difficult or impossible to measure such detriment. Evidence suggests they are highly prevalent on websites, apps and cookie consent notices (OECD, 2022[21]). In the context of data collection, such practices can lead consumers to give up more personal data than they may have otherwise chosen. They do this, for example, by making privacy-intrusive settings the default or making it hard to opt out of them. In addition, the data that online businesses collect through consumer interactions increasingly allow the construction of fine-grained consumer profiles. Businesses may be able to leverage information asymmetries from such data profiling to exploit consumer vulnerabilities at a highly granular level. However, there is little evidence to suggest that such practices are widespread (OECD, 2022[21]).

Figure 2.3. Personal data breaches are on the rise across a number of OECD jurisdictions

Notes: Australia, New Zealand and United Kingdom data refer to the fiscal year. Canada data combines data on number of breaches for the public and private sectors. Numbers of personal data breach notifications (PDBNs) in 2017 are normalised to 100. Numbers of PDBNs in 2018 and 2019 are compared against this normalised value. To avoid overrepresentation of changes from small numbers, data under 50 were eliminated from the calculation.

Source: Iwaya, Koksal-Oudot and Ronchi (2021[22]), “Promoting comparability in personal data breach notification reporting”, https://doi.org/10.1787/88f79eb0-en.

The risk of privacy and personal data protection rights violation also exists outside of the commercial context. Data typically collected by private companies for their business purposes have become increasingly valuable to governments. For instance, government law enforcement and national security agencies have made more requests to private companies to access their user data (Llanos, 2021[23]). While legitimate public interests can justify such access, the elevated number of requests also raises concerns about infringements of privacy and civil liberties, which can erode trust among governments and between governments and individuals. Furthermore, they can affect personal data flows across borders and create uncertainty and compliance costs for businesses (OECD, 2022[2]). In response, major companies have begun to publish transparency reports on demands from government agencies. However, such disclosures may not be possible in some jurisdictions (Llanos, 2021[23]) (see section 4.2 for OECD policy efforts to address this trust gap).

Regulatory frameworks can be slow to adapt to a fast-moving technological landscape. Consequently, they can be unable to address evolving uses and misuses of data that are viewed as unethical or that may generate undesirable outcomes. Factors that complement regulatory or legal issues, and that are often considered ethical in nature, include issues such as fairness, respect for human dignity, autonomy, self-determination, human rights and the risk of bias and discrimination. These ethical considerations and factors provide additional guidance for data governance and use, beyond mere legal compliance.

A key example concerns the role of data in AI or other algorithmically driven systems, and the possibility of creating feedback loops that reinforce biases. Recent work explored the effect of AI on the lives of working women, for example. It highlights that gendered data used by labour market intermediaries to target online job advertisements can worsen gaps between the number of men and women in some occupations (UNESCO, OECD and IDB, 2022[24]). Moreover, the underlying data used as input into AI systems may not be sufficiently representative. They may also perpetuate historical gender stereotypes around gender roles in labour, care and domestic work. The rise of questionable uses of data underscores the importance of a common understanding of data ethics to guide the use of data where regulatory frameworks may fall short (OECD, 2022[1]). OECD standards such as the OECD Good Practice Principles for Data Ethics in the Public Sector aim at providing further action-oriented guidance in this area (OECD, 2019[25]) (see Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Addressing the risks: Towards a common understanding of data ethics

Often considered in the frame of broader human rights, data ethics approaches can complement legal approaches and help inform how regulations should be drafted or revised. In particular, taking a data ethical approach can help build trust in responsible organisations. Data ethics audits, impact assessments or certifications can help build overall trusted data transactions. Such schemes should take a multi-stakeholder approach and include civil society organisations, as well as academics and researchers.

A wide range of data ethics definitions and frameworks has been developed across jurisdictions, often encompassing legal, policy and voluntary approaches. Such frameworks tend to provide high-level principles to guide the use of data, including in AI applications. Notably, the private sector and professional and representative bodies, which often self-regulate in data-related fields, increasingly promulgate data ethics frameworks.

In the public sector, ensuring the ethical use of data calls for defining and embedding value-based approaches in the daily management and use of data by public servants and public-sector organisations. The OECD Good Practice Principles for Data Ethics in the Public Sector emerged from observed data ethical practices in OECD countries and partner economies, and their actions to develop data ethical capabilities in the public sector. As their overarching message, the Good Practice Principles state that government data use should serve the public interest and deliver public good. They also discuss the collective and community nature of data governance, the environmental impact of data infrastructures and the abuse of data use during electoral campaigns.

Note: This box is based on an expert workshop on Data Ethics: Balancing Ethical And Innovative Uses of Data, which was co-hosted by the OECD and Danish Business Authority on 9-10 December 2021.

Sources: Jobin, Ienca and Vayena (2019[26]), “The global landscape of AI ethics”, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0088-2; New Zealand Government (2020[27]), “International Data Ethics Frameworks”, https://www.data.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Discussion-paper-International-data-ethics-frameworks-March-2020.pdf; OECD (2019[25]), “Good Practice Principles for Data Ethics in the Public Sector”, https://www.oecd.org/digital/digital-government/good-practice-principles-for-data-ethics-in-the-public-sector.htm.

A different type of risk relates to the lack of incentives for firms to share data. Firms may choose not to share data if they have limited ability to profit from the benefits of the use of data for other firms or society at large. This, in turn, diminishes the utility of data to society. In addition, concerns regarding the intellectual property rights of organisations and the protection of their commercial interests can negatively affect incentives to invest in data collection and data use. For SMEs, for example, identifying which data to share and defining the scope and conditions for access and re-use are perceived as major challenges. Moreover, firms may be reluctant to share data because of potentially significant costs. Sharing data inappropriately could lead to costs associated with privacy violations, as well as opportunity costs of potential innovation. For example, sharing data prematurely can undermine the ability to obtain patent and trade secret protection (OECD, 2021[28]; 2019[29]; 2019[30]).

The use of data by companies is of considerable interest to competition authorities. If data represent a significant barrier to entry to a market, firms that control that data may be able to act in a manner that may have anti-competitive effects. For example, they might exclude competitors from a market if they control access to their data inputs (OECD, 2020[31]). Mergers could strengthen the effect of such behaviour. Similarly, when firms have particularly valuable or complementary datasets, a potential merger could give rise to an advantage that is difficult for competitors to overcome and result in durable market power (OECD, 2020[32]; 2020[33]). Another risk of mergers is that personal data collection in one market could also be leveraged in a related market, which could limit the contestability of both markets. In other words, where data access is limited and essential to compete, challengers would need to offer a matching ecosystem of products to match an incumbent’s position (Condorelli and Padilla, 2019[34]). Data and their role in fostering network effects, economies of scale, and scope and feedback loops that can lead to increasing concentration in digital markets, is also an area of concern for competition authorities (OECD, 2022[17]).

The use of data by firms also has wider effects on the economy. Data and other intangibles have taken on increasing importance to knowledge- and service-intensive production. The growing importance of data and other intangibles may have disproportionately benefitted the largest global firms (Bajgar, Criscuolo and Timmis, 2021[35]; Corrado et al., 2021[36]; 2022[37]). Investments in intangible assets, including data, within industries are linked to increasing productivity dispersion in those industries. Namely, as data become important to a given industry and investment in data grows accordingly, gaps in the productivity of firms within those industries grow as well (Corrado et al., 2021[36]; 2022[37]). Intangibles-intensive industries are also becoming increasingly concentrated, with less churning at the top. This indicates that big firms are getting bigger and tend to stay at the top of their industries (Bajgar, Criscuolo and Timmis, 2021[35]).

These dynamics threaten long-term inclusive growth and well-being across the OECD. Productivity growth allows economies and societies to benefit from a wider range of outputs with the same level of input; productivity growth is the most important factor in increases in living standards and economic growth (OECD, 2015[38]). The varying rates of productivity growth between firms has been previously linked to wage inequality (Berlingieri, Blanchenay and Criscuolo, 2017[39]). They may also be related to the trend towards greater income and wealth inequality in advanced economies in recent years. Moreover, reaping the productivity benefits of increased data use is essential to managing forthcoming social challenges, like demographic shifts and climate change. It also enables long-term economic growth and well-being across the OECD. Promoting access to and use of data across all sectors and company sizes, and overcoming related barriers, can enable a wider distribution of the benefits of data use.

2.4. The fundamental shift in data use is reflected in public policies at the national and international levels

Both the potential and realised transformative effect of data on economies and societies, and the attendant risks, have led to more public policies and regulations that target data. This growth in policy attention also reflects changes resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and more awareness of the need for policy to ensure wider yet responsible use of data. Such measures usually respond directly to the opportunities and risks of data use outlined in sections 2.2 and 2.3. However, they rarely attempt to address the interrelated policy issues related to data in a cross-cutting manner.

The COVID-19 crisis, for example, highlighted the need for timely data for decision making (see also section 3.4). Consequently, governments have increased the collection and sharing of data from health systems. In the first half of 2020, few countries scored highly on dataset availability, maturity and use and dataset governance (Oderkirk, 2021[40]). Yet in 2021, 15 of 24 surveyed OECD countries had enacted legal, regulatory or policy reforms to improve health data availability, access or sharing. Meanwhile, 16 of those countries had introduced new technologies to improve health data governance. Governments also introduced measures to improve data linkage and sharing and improve sector-related capacities. As a result of these reforms, most surveyed countries saw significant improvement in the timeliness and quality of key health datasets (de Bienassisi et al., 2022[41]).

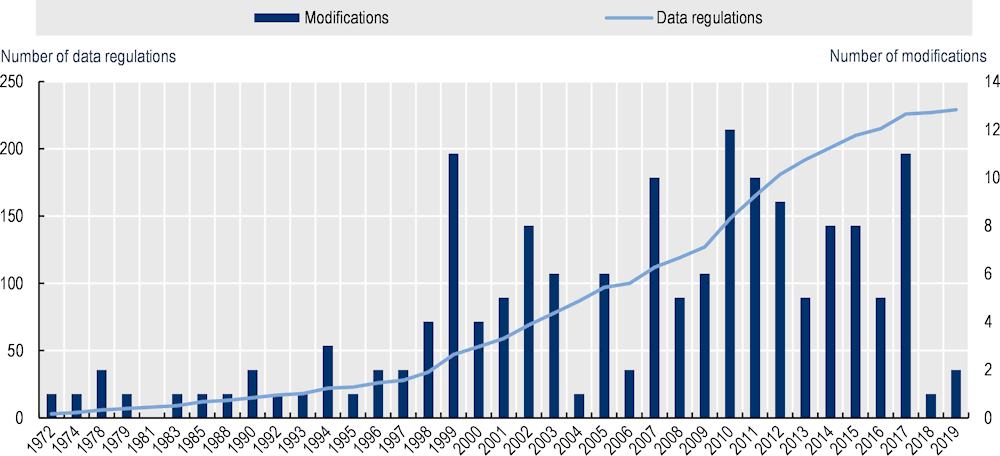

With more collection, exchange and use of data, including across borders, over the last two decades, governments have put in place policies to govern the transfer of data across borders (see Figure 2.4). In some cases, this includes the location for storage of such data. Governments may put in place such measures for a number of reasons. These include the desire to preserve competition and contestable markets, data protection, privacy and digital security; to enable regulatory control or audits; or to uphold national security. In addition, because the collection, use and control of data are also often viewed as a competitive advantage at the national level, some such regulations also act as a kind of digital industrial policy, including in the context of economic development (OECD, 2022[2]).

Figure 2.4. Growing number of regulations affecting cross-border data flows

Note: This figure includes different types of regulation relating to data transfers and local storage requirements.

Source: Casalini and López González (2019[42]), “Trade and Cross-Border Data Flows", https://doi.org/10.1787/b2023a47-en.

Another specific form of data-related regulation growing across the OECD includes ex ante competition regulation in certain digital markets. This growth reflects concerns that competition frameworks and ex post competition enforcement are not adequate for increasingly data-driven and digital markets. These ex ante regulations often aim to increase market contestability by imposing requirements on a particular handful of firms. These firms are usually the largest online platforms, which are perceived as having a particular ability to harm competition in digital markets. Notably, the targeted firms, sometimes designated “gatekeepers”, may have a position in markets that might differ from the traditional definition of “dominance” in competition frameworks (OECD, 2022[17]).

In addition to other measures like transparency and business conduct obligations, merger requirements and obligations to limit “self-preferencing” and bundling, many forms of proposed ex ante regulation address data-related concerns. Such measures reflect a view that access to and control of data can act as a structural barrier to entry and can carry the risk of exclusionary and exploitative conduct. Indeed, part of the function of these data-related measures is to “[grant] other firms an edge to compete with designated firms”, namely those firms that are considered “gatekeepers” (OECD, 2021[43]). Data-related measures in ex ante regulations include obligations for data portability and interoperability, prohibitions on combining certain datasets i.e. including after merger activity, and obligations to grant access to certain kinds of datasets to competitors.

References

[35] Bajgar, M., C. Criscuolo and J. Timmis (2021), “Intangibles and industry concentration: Supersize me”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2021/12, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ce813aa5-en.

[39] Berlingieri, G., P. Blanchenay and C. Criscuolo (2017), “The great divergence(s)”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 39, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/953f3853-en.

[42] Casalini, F. and J. López González (2019), “Trade and Cross-Border Data Flows”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 220, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b2023a47-en.

[34] Condorelli, D. and J. Padilla (2019), Harnessing Platform Envelopment in the Digital World, Department of Economics, University of Warwick, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3504025.

[36] Corrado, C. et al. (2021), “New evidence on intangibles, diffusion and productivity”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2021/10, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/de0378f3-en.

[37] Corrado, C. et al. (2022), “The value of data in digital-based business models: Measurement and economic policy implications”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1723, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d960a10c-en.

[41] de Bienassisi, K. et al. (2022), “Health data and governance developments in relation to COVID-19: How OECD countries are adjusting health data systems for the new normal”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 138, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/aec7c409-en.

[22] Iwaya, S., E. Koksal-Oudot and E. Ronchi (2021), “Promoting comparability in personal data breach notification reporting”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 322, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/88f79eb0-en.

[26] Jobin, A., M. Ienca and E. Vayena (2019), “The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines”, Nature Machine Intelligence, Vol. 1, pp. 389-399, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0088-2.

[15] Jones, C. and C. Tonetti (2020), “Nonrivalry and the economics of data”, American Economic Review, Vol. 9, pp. 2018-2058, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20191330.

[9] Jouanjean, M. et al. (2020), “Issues around data governance in the digital transformation of agriculture: The farmers’ perspective”, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 146, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/53ecf2ab-en.

[14] Ker, D. and E. Mazzini (2020), “Perspectives on the value of data and data flows”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 299, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a2216bc1-en.

[23] Llanos, J. (2021), “Transparency reporting: Considerations for the review of the Privacy Guidelines”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 309, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e90c11b6-en.

[27] New Zealand Government (2020), “Discussion Paper: International Data Ethics Frameworks”, prepared for the Government Chief Data Steward for the Data Ethics Advisory Group, https://www.data.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Discussion-paper-International-data-ethics-frameworks-March-2020.pdf.

[13] Nguyen, D. and M. Paczos (2020), “Measuring the economic value of data and cross-border data flows: A business perspective”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 297, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6345995e-en.

[40] Oderkirk, J. (2021), “Survey results: National health data infrastructure and governance”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 127, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/55d24b5d-en.

[21] OECD (2022), “Dark commercial patterns”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 336, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/44f5e846-en.

[12] OECD (2022), “Data shaping firms and markets”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 345, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/923230a6-en.

[2] OECD (2022), “Fostering cross-border data flows with trust”, OECD Digital Economy Policy Papers, No. 343, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/139b32ad-en.

[19] OECD (2022), Going Digital Guide to Data Governance Policy Making, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/40d53904-en.

[10] OECD (2022), Japan-OECD Joint Workshop on Data Free Flow with Trust, OECD, Paris.

[16] OECD (2022), “Measuring the value of data and data flows”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 345, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/923230a6-en.

[17] OECD (2022), OECD Handbook on Competition Policy in the Digital Age, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-handbook-on-competition-policy-in-the-digital-age.pdf.

[1] OECD (2022), “Responding to societal challenges with data: Access, sharing, stewardship and control”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 342, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2182ce9f-en.

[43] OECD (2021), “Ex ante regulation and competition in digital markets”, OECD Competition Background Note, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/ex-ante-regulation-and-competition-in-digital-markets-2021.pdf.

[8] OECD (2021), OECD Science, Technology and Innovation Outlook 2021: Times of Crisis and Opportunity, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/75f79015-en.

[28] OECD (2021), OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/97a5bbfe-en.

[20] OECD (2021), Report on the Implementation of the Recommendation of the Council Concerning Guidelines Governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data, OECD, Paris, https://one.oecd.org/document/C(2021)42/en/pdf.

[11] OECD (2021), The Digital Transformation of SMEs, OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bdb9256a-en.

[31] OECD (2020), “Abuse of Dominance in Digital Markets”, OECD Competition Background Note, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/abuse-of-dominance-in-digital-markets-2020.pdf.

[32] OECD (2020), “Consumer data rights and competition”, OECD Competition Background Note, OECD, Paris, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP(2020)1/en/pdf.

[6] OECD (2020), Enhanced Access to Publicly Funded data for Science, Technology and Innovation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/947717bc-en.

[33] OECD (2020), “Merger control in dynamic markets”, OECD Competition Background Note, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/merger-control-in-dynamic-markets-2020.pdf.

[5] OECD (2020), “Using artificial intelligence to help combat COVID-19”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/using-artificial-intelligenceto-help-combat-covid-19-ae4c5c21/.

[7] OECD (2020), “Why open science is critical to combatting COVID-19”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/why-open-science-is-critical-to-combatting-covid-19-cd6ab2f9/#:~:text=In%20global%20emergencies%20like%20the,critical%20to%20combating%20the%20disease.

[30] OECD (2019), Enhancing Access to and Sharing of Data: Reconciling Risks and Benefits for Data Re-use across Societies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/276aaca8-en.

[25] OECD (2019), “Good Practice Principles for Data Ethics in the Public Sector”, webpage, https://www.oecd.org/digital/digital-government/good-practice-principles-for-data-ethics-in-the-public-sector.htm (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[29] OECD (2019), OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/34907e9c-en.

[18] OECD (2019), Unpacking E-commerce: Business Models, Trends and Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/23561431-en.

[38] OECD (2015), The Future of Productivity, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264248533-en.

[4] OECD and Govlab (2021), “Open Data in Action: Initiatives During the Initial Stage of the COVID-19 Pandemic – OECD”, webpage, https://www.oecd.org/fr/gouvernance/gouvernement-numerique/use-of-open-government-data-to-address-covid19-outbreak.htm (accessed on 14 April 2021).

[3] Paic, A. (2021), “Open Science – Enabling Discovery in the Digital Age”, Going Digital Toolkit Note, No. 13, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/data/notes/No13_ToolkitNote_OpenScience.pdf.

[24] UNESCO, OECD and IDB (2022), The Effects of AI on the Working Lives of Women, UNESCO/OECD/Inter-American Development Bank, https://doi.org/10.18235/0004055.