High alcohol consumption is associated with increased risk of heart diseases, stroke, liver cirrhosis, certain cancers, but even low-risk alcohol consumption increases the long-term risk of developing such diseases. Alcohol use was responsible for about 295 000 deaths across EU countries in 2019 (IHME, 2021[1]).

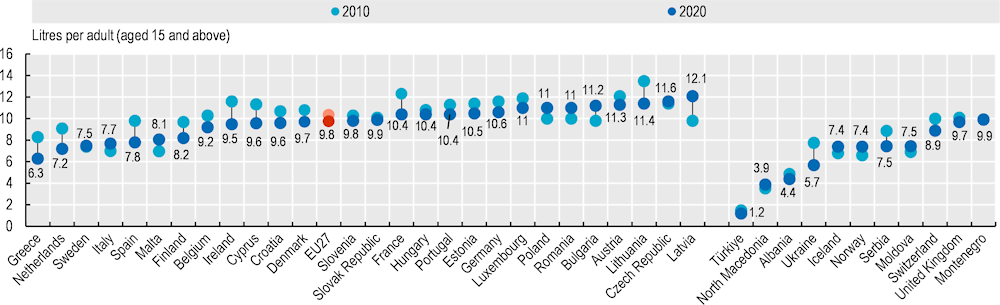

Measured through sales data, overall alcohol consumption stood at 9.8 litres of pure alcohol per adult on average across EU countries in 2020, a slight reduction compared to 10.4 litres in 2010 (Figure 4.8). Latvia, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Austria and Bulgaria show the highest levels of consumption, while Greece, the Netherlands and Sweden have relatively low levels among EU countries.

Over the past decade, alcohol consumption has decreased in most EU countries, with the largest reductions in Ireland, Lithuania, Greece and Spain. It has slightly increased in Latvia, Bulgaria, Poland, Romania and Malta, although it remains well below the EU average in Malta.

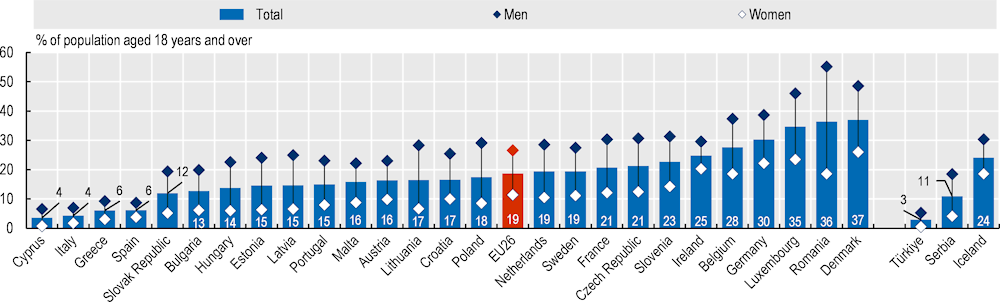

Nearly one in five adults (19%) reported heavy episodic drinking at least once a month in EU countries in 2019 (Figure 4.9), a proportion that has remained stable since 2014. This proportion varies from less than 5% in Cyprus and Italy to more than 35% in Romania and Denmark. In all countries, men were more likely than women to report heavy episodic drinking.

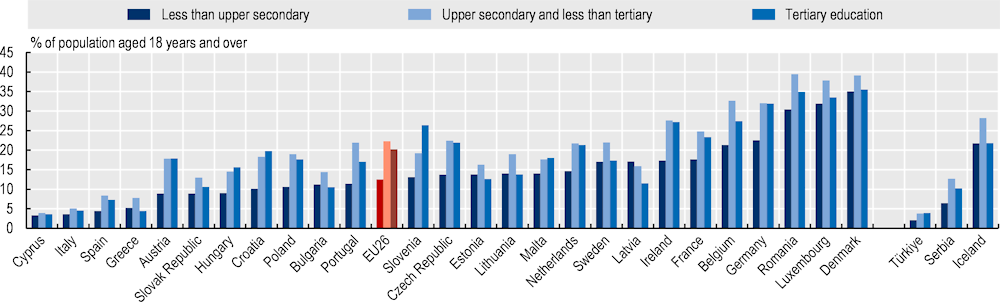

By contrast with many other risk factors, people with lower education levels do not have a higher rate of heavy episodic drinking in EU countries, except in Latvia. On average, 13% of people with less than upper secondary education reported heavy episodic drinking, compared to 20% or more of people with at least upper secondary or tertiary education (Figure 4.10). These differences largely reflect greater purchasing capacity: alcohol is more affordable for people with more education and higher incomes. However, when looking at alcohol-related harm, the burden is greater on people with lower socio‑economic status.

Many European countries have implemented a range of policies to limit alcohol consumption, such as taxation, restrictions on alcohol availability and bans on alcohol advertising, but their effectiveness is hindered by poor implementation on the ground and limited resources (OECD, 2021[2]). The Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan has identified reducing harmful alcohol as a priority, suggesting several actions, such as limiting online advertising and promotion, reviewing EU legislation on alcohol taxation and cross-border purchases, mandatory labelling of ingredient and nutrient content on alcoholic beverages by the end of 2022, and health warning by the end of 2023 (European Commission, 2021[3]).