This chapter deals with the illicit trade in Libya, which is a regional transit point being both a source and a destination of counterfeit goods. The Libyan conflict has led to an increase in illicit activities and notably in the areas of trafficking of weapons, narcotics, humans and cultural artefacts which are specifically analysed.

Illicit Trade in Conflict-affected Countries of the Middle East and North Africa

3. Libya

Abstract

Background to current conflict

Libya has been in a severe state of insecurity since the ouster and death of former leader Muammar Gaddafi in late 2011. The government elected in July 2012, the General National Congress, has faced numerous setbacks over the years. The most noticeable of these setbacks were the September 2012 attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi and the quick spread of the armed Islamic State throughout the country.

In 2014, the Libyan National Army launched Operation Dignity to attack militant groups across eastern Libya. Following this campaign, numerous armed groups formed a coalition called Libya Dawn. Fighting between these two factions broke out in Tripoli, the nation’s capital. A full civil war emerged from this confrontation with the Dawn coalition controlling Tripoli and much of western Libya and the Dignity coalition controlling Benghazi and eastern Libya.

The battle for control over Libya is highly complex, as it crosses tribal, regional, political, and religious lines. Both coalitions have created central governments, established central banks, and have named military leaders. However, over the course of the war, internal fragmentation has affected both sides, which has further complicated the situation.

To stop the fighting, the UN Special Envoy to Libya facilitated peace talks between the two controlling governments. These talks created the Libyan Political Agreement and the interim, UN-supported Government of National Accord, although the GNA has faced considerable obstacles to creating a unified Libyan government.1

The current territorial holdings in Libya as of May 2021 are complex.2 The Russian-, UAE-, and Egyptian-backed Libyan National Army controls most of the eastern part of the country. The key holdings of this group include Tobruk, Benghazi, and Sirte. Meanwhile, the Government of National Accord controls the capital and largest city, Tripoli, as well as Misrata and most of the western part of the country. The southern portions of the country are controlled by local militant forces, except for Sabha, which is controlled by the Libyan National Army. The southern militant forces hold varying affiliations, and the Islamic State has significant influence in the region. Also, it is important to note that all coastal ports are open and controlled by their corresponding governments with the two exceptions of National Army controlled Sirte and Derna which are closed.3

Illicit trade in Libya

Like in Yemen, the civil war has negatively impacted the Libyan populace. It is estimated that more 200,000 people have been internally displaced and approximately 1.3 million Libyans are in need of humanitarian assistance. In the same manner illicit trade affected Yemen, Libya has also been negatively impacted by the increase in illicit trade flows since the civil war began.

There seems to be little or no real effort by either of the central authorities in Libya to counter illicit trade, as both groups are largely preoccupied with fighting each other and organising an internationally recognized government. It comes as no surprise that illicit trade issues affect Libya heavily.4

Following the collapse of the Gaddafi regime, Libya evolved into a hotbed for illicit economic activities. While the Gaddafi regime had permissive policies toward these activities, the collapse of its political power and the failure of the state-building process created a decentralized and pervasive war economy.

Weapons

Arms flows are the largest and most impactful illicit dynamic in Libya, with both local and global ramifications the arms trade is the most. Weaponry is crucial to buying protection, threatening others, and holding control over the other illicit markets that fund military operations.

Before the civil war began in 2011, Libya already had a sizeable arms culture, as the country was one of the largest and most diverse owners of conventional weapons in Africa. Once the old regime in Libya was ousted, the political instability in the nation motivated everyday Libyans to take up arms to protect their families and homes.

A clear picture mapping the flow of arms into and across Libya can be drawn by separating the trade into two flows: diversion of existing arms stockpiles and external transfers to non-state actors. Addressing the first flow, the poorly guarded arms stockpiles were systematically looted by rebel and militia groups across the country. These stockpiles extended beyond smaller arms and light weaponry, as many of the confiscated arms were heavy weaponry, ammunition, tanks, and other military vehicles. There was fierce competition between the rival militarist groups to acquire these weapons, and ultimately many arms found their way into terrorist hands. To address this threat, the General National Congress instituted a weapons recall, but very few listened to the request.

The arms trade in Libya became more internationalized after 2014. Multiple UN reports suggest that the main regional and global players, provided their allies and affiliated groups with heavy artillery, anti-tank missiles, drones, and heavy weaponry, violating the U.N.S.C. arms embargo. Furthermore, international security contractors and foreign mercenaries have only increased the flow of goods into the nation in more recent years. There has also been a spill-over effect in the illicit arms trade, as there are reports indicating that Libyan weaponry has been used in Sudan, Syria, and Gaza. Moreover, due to the lack of adequate border controls, Libya arms have been extensively used by the Tuaregs and Malians in their conflict, Boko Haram in West Africa, and terrorist organizations like Al-Qaeda throughout the Maghreb region. International online markets have also worsened the Libyan arms trade situation. Small arms and light weaponry from at least 26 countries can be found on online illicit weapon marketplaces. Social media is playing an increasingly important role in this trend as well by making transactions between private groups easier than before.5

Narcotics

Like in Yemen, Libya is severely affected by the illicit drug trade. Smuggling has been embedded into Libyan society since Gaddafi was in power, as the nation sits at the centre of most trans-Saharan trade routes and has key links with the Mediterranean region. But since the 2011 uprising, the nation predominately acts as a destination hub, rather than a transit point, for illegal drugs since many of the illicit smuggling networks maintained by Gaddafi himself fell into the hands of the varying factions, although the international drug trade still exists.6

The largest drug trade in Libya is cannabis. Typically, blocks of cannabis resin produced in Morocco makes its way into Libya where it is either consumed by the nation or transferred onto Egypt and the Balkans. The internal cannabis trade is larger in southern Libya, with cities like Sebha, Ubari, and Murzuq being major players. The international drug trade normally transits on traditional trade routes through points like Tazirbu and Rebiana. Cannabis is also stored to serve growing domestic markets for hashish. Coastal cannabis flows through Libyan seaports are also rising in popularity. Al-Khoms and Musrata in the west and Tobruk in the east are the key coastal trade ports and show that both factions are engaging in the illicit drug trade.

The cocaine trade is less common than the cannabis trade, although it is still a major component of the overall illicit drug trade. Typically, cocaine moves in large heavily guarded convoys separate from other drug and illicit trafficking flows. This trade is intercontinental as cocaine typically comes from Latin America via West Africa. There is also cooperation with other illicit economic groups and smugglers that facilitate the illicit cocaine trade by clearing convoy routes for expedited transfer processes. There is also little evidence that suggests Libya is a destination country for cocaine, so it merely acts as a transit point to markets in Europe. It is also important to note that Libya is becoming less of a player in the cocaine trade as flows and trade routes are increasingly moving out of Africa.

Libya also sustains a domestic ecstasy and amphetamine market. Trade of these drugs typically moves through seaports and airports. Tripoli, Al-Khoms, Misrata, Benghazi, and Tobruk are the most relevant cities in this trade. Libya also had a small but serious heroin problem through the 2000s, but since heroin production in Afghanistan has slowed dramatically, the market in Libya shrank quickly.

The most expansive and important drug trade in Libya is pharmaceutical smuggling. This is because customs officials at airports and seaports only occasionally audit shipping containers, usually when they receive a tip-off. A conventional land trade route for pharmaceutical smuggling also exists which connects the booming market for these illegal drugs in virtually all parts of Libya. The situation is also worsened by the illicit practice of pharmacies supplying drugs without prescriptions. Painkillers, psychiatric medicines, and sleeping pills are the main drugs pharmacies, smugglers, and armed groups use to supplement their income.

Human trafficking

In addition to arms and drugs, human trafficking is a key aspect of overall illicit trade in Libya. For instance, in the western portions of the country, the Amazigh community used their control over human smuggling to boost their fortunes and gain political control in the country. However, by 2015, this group largely stopped this illicit activity even as the human smuggling trade was becoming more commoditised. Militias have also formed international ties with various tribes to facilitate illicit human trafficking flows.

Illicit Trade in cultural artefacts

The final component of illicit trade in Libya is the illegal trade of cultural artefacts. Like in Yemen, the looting and distribution of archaeological findings has been rampant. The collapse of the Libyan economy during this civil war has made theft, looting, and trafficking tempting for smugglers and looters. This situation has only been worsened by emerging online markets that facilitate the international illicit trade of Libyan antiquities.7

Quantitative picture – illicit trade in counterfeits in Libya

According to the OECD data on customs seizures, Libya is a transit point in illicit trade in fakes, being both: a provenance and destination in trade in counterfeit goods.

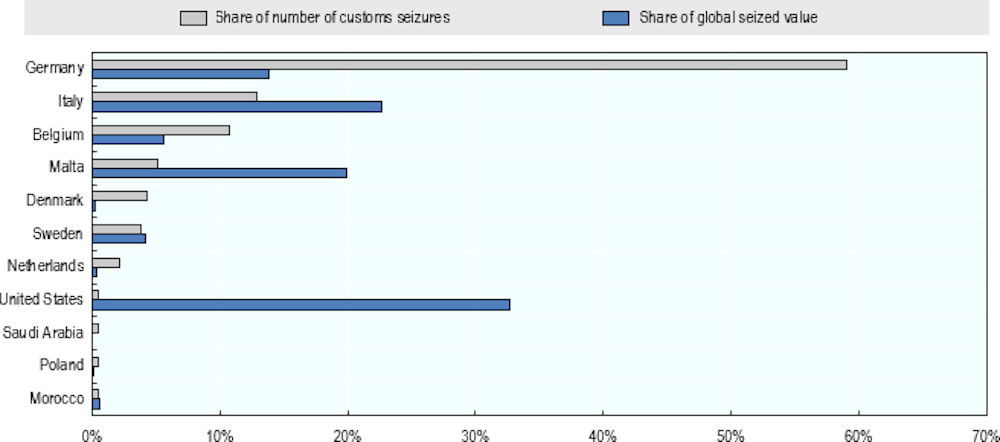

Over 2017-2019, Libya was the sixty-first provenance economy of global counterfeit goods. As can be seen in Figure 3.1, the counterfeit goods coming from Libya were mostly destined to European countries (e.g. Germany, Italy, Belgium, Malta) in terms of number of customs seizures. United States were the first destination country in terms of seized value.

Figure 3.1. Main destination economy for counterfeit goods originating from Libya

Source: OECD global customs seizures database

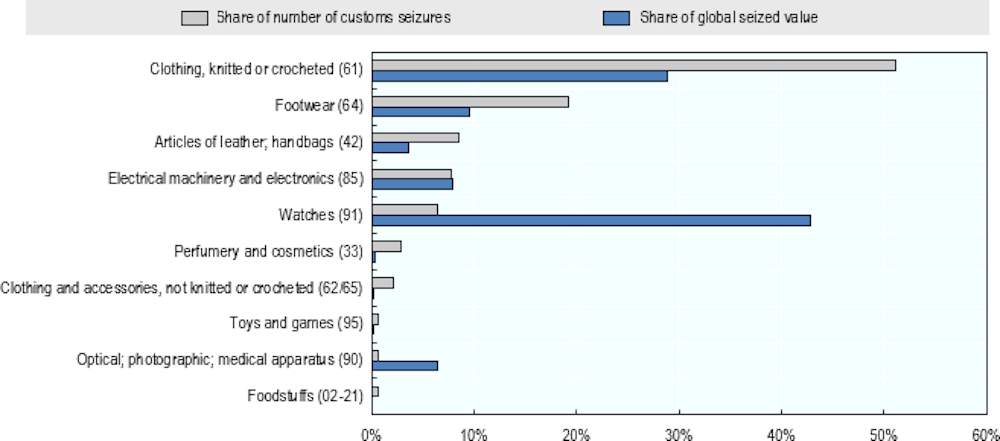

The scope of counterfeit goods exported from Libya is broad and includes clothing (51% of global customs seizure coming from Libya), footwear (19%) and leather goods (9%). In terms of seized value, watches clothing and footwear were the main counterfeit product categories (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Product categories of counterfeit goods originating from Libya

Source: OECD global customs seizures database

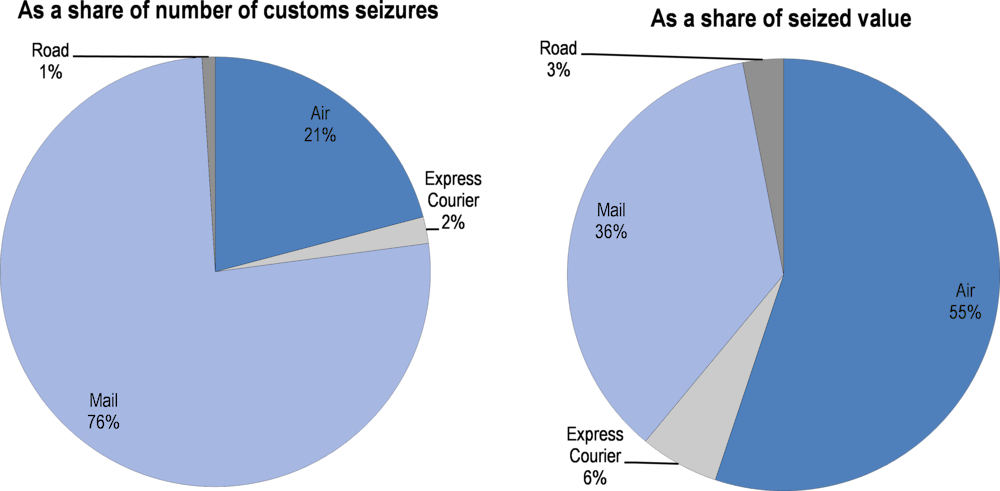

Data on customs seizures also provide insight on conveyance methods used to ship counterfeit goods. As can be seen in Figure 3.3, fakes coming from Libya were mostly shipped through mail (76%) and air (21%).

Figure 3.3. Conveyance methods of counterfeit goods originating from Libya, 2011-19

Source: OECD

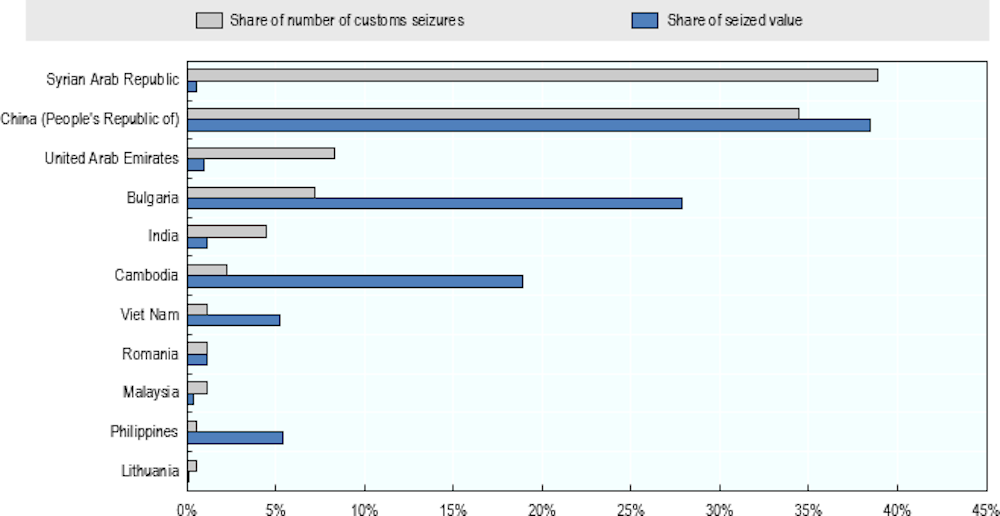

Regarding the fake goods imported into Libya, they mostly come from the MENA region. Syria was the first source of counterfeits entering Libya and the United Arab Emirates being the third provenance economy. Imports of fakes in Libya also frequently came from China and other Far-East Asian countries such as India, Cambodia, Viet Nam or Malaysia.

Figure 3.4. Main provenance economies of counterfeit goods imported into Libya, 2011-19

Source: OECD global customs seizures database

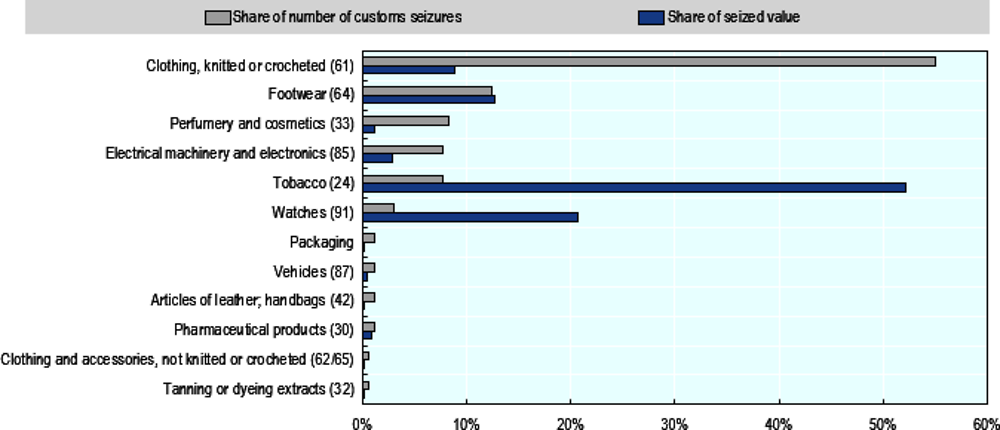

Figure 3.5 shows the main product categories of fakes imported into Libya. Over 2011-19, Libya mostly imported fake clothing (55%), footwear (12%) as well as perfumery and cosmetics (8%). In terms of seized value, counterfeit tobacco (52%) and watches (21%) were the main products imported into Libya.

Figure 3.5. Main product categories of fake imports in Libya, 2011-19

Source: OECD global customs seizures database

Counterfeit goods entering Libya were mostly shipped by sea. This conveyance method represented almost 100% of both the global seized value and the number of customs seizures destined to Libya.

Notes

← 2. For recent updates see https://microsites-live-backend.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/civil-war-libya