This chapter focuses on the illicit trade in Syria. In particular, it discusses how the war in Syria has influenced the networks of illicit actors. Specific attention is given to the trafficking of human, arms, narcotics, cultural artefacts as well as the abuse of e-commerce to facilitate illicit trade activities.

Illicit Trade in Conflict-affected Countries of the Middle East and North Africa

4. Syria

Abstract

Background to current conflict

Syria has been in a state of disarray since President Assad’s regime gained control in 2011. Sizeable protests against the regime quickly grew into a full-scale civil war between the government and anti-government rebel groups, both supported by regional and global powers. Three primary conflicts are driving the confrontation in Syria: violence between the government and opposition forces, international coalition efforts to defeat the Islamic State.

Efforts to reach a diplomatic resolution have largely been unsuccessful as opposition and Syrian regime officials struggled to find mutually agreeable terms. Some progress was made following peace talks held in Kazakhstan, resulting in a cease-fire agreement and four de-escalation zones.1 However, shortly after the cease-fire was implemented, Syrian government forces attacked opposition-held areas in these crucial zones. The Syrian government has also faced international condemnation after using chemical weapons over the course of the conflict.

More recently, the 2020 withdrawal of United States ground forces from north Syria has played a large role in the civil war, even with the United States-led coalition continuing to utilize airstrikes as part of their general strategy. The withdrawal of American troops has increased uncertainty around the role of other regional and global parties involved in the conflict, namely Russia, Turkey, Iran, and Israel.

As of May 2021, President Assad’s government controls a majority of Syria. The President’s supporters, control the nation’s coastal heartland, including the capital Damascus, and have regained control over the major mercantile cities of Aleppo in the north and Daraa in the south. Meanwhile the American-led coalition has largely defeated the Islamic State and has gifted the land they fought for, including the oilfields, to the Kurds in the northeast. Meanwhile the Turkish-led coalition have a foothold in the northwest part of the country and have created a buffer between the Turkish mainland and neighbouring Kurdish-controlled territory. The Islamic State and other jihadist organizations also have a few pockets scattered throughout the country.2

Illicit trade in Syria

In terms of trade, the territory of modern Syria has historically been a key trade corridor, linking Turkey with the Middle East. But today, Syria acts as a major highway for illicit trading activities. Many smuggling groups are apolitical, private, and profit-oriented networks composed of connected businessmen and border residents. By the start of the civil war, a long history of drug, weapons, and people trafficking have created networks of illicit actors in Syria and some of its neighbouring countries which were only strengthened by the insecurity and instability of the conflict. The international networks are vital conduits of weapons and ammunitions for militant organizations. Meanwhile, these same networks satisfy the necessities of Syrian citizens who need food, aid, and opportunities to escape the conflict zone. In turn, these networks benefitted from the chaos, by supplying the demand for weapons and aid, and by leveraging the war to loot sectors of the economy.3 4

Weapons

One of these key sectors was defence, although the arms trade in Syria appears to be less intense than the ones in Yemen and Libya. Unlike Yemen and Libya, which have long had many guns within their own respective borders, Syria has historically had far fewer weapons in civilian hands than its neighbours. Since there were comparatively less weapons in Syria outside of state control at the advent on the conflict, a large illicit arms trade was needed by the various militant groups to fuel the conflict. Weapons enter insurgent hands in three main ways: purchase from a corrupt government, transfer from defecting soldiers, and looting from offensive campaigns.

The Syrian insurgency has also been supplied by neighbouring countries. Once weapons are procured, they move easily into Syria over the unguarded border via vehicle, donkey, or foot, before being offered in marketplaces. The most common entry points for weapons are Turkey and Jordan, and many of the international arms originate from Libya and the Black Sea region. As the conflict has raged on, illegal arms smuggling has transitioned from largely ad-hoc efforts into an established trade operated by professional criminal organizations.5

Narcotics

The largest illicit trade operations in Syria seem to be centred around drug smuggling, rather than arms smuggling.6 In fact, the drug trade in Syria has grown so severe that some are even calling the nation a narco-state.7 Syria has long been active in the global drug trade. In the 1990s, when Syria occupied and ruled Lebanon, the nation was a main producer of hashish worldwide. However, the levels of drug production seen today only stared after the civil war started. One of the primary drugs the nation produces is Captagon, a fenethylline. Insurgent fighters from Afghanistan and Lebanon have been particularly impactful, as they brought drug-making and trafficking skills to foster hashish and Captagon cultivation. This drug serves a sizeable domestic market, as many Syrian soldiers are fed these pills by their commanding officers. In addition to fuelling domestic drug addiction, Saudi Arabia has also fallen victim to the massive trade of this drug.

Syria began exporting Captagon in 2013, using Aleppo, Homs, Rif-Dimashq, Damascus, Qusayr, and Tal Kalakh as key production and smuggling points. Seizures of Syrian narcotics has been on the rise since 2013, with a sharp increase after 2018. In fact, in 2020, 84 million pills worth over 1 billion euros were seized on just one ship. The key shipping route for Syrian narcotics flows through the Libyan port of Benghazi into the Assad-controlled port of Latakia. Syrian drugs can also be found as far as Malaysia.

There is evidence to suggest that the government regime is involved with the narcotics trade.8 Since the drug trade is so profitable, pills can be marked up over 50 times their cost in Syria, it would be advantageous for the Syrian government to become involved. The Assad regime has had difficulty in the past paying their troops, so any additional revenues, even if associated with smuggling, would make the government more effective in their civil war campaign. The Syrian government has also reportedly used drugs as a geopolitical tool, threating to overflow rival territories with illicit drugs if they disagree with their vision. However, the Assad regime is not alone in the drug trade. The Kurds in the north also operate trade routes along the border with Turkey, so there is substantial evidence suggesting most militia and insurgent groups are involved with illicit smuggling activities, although it appears the Islamic State in Syria is not directly linked with the trade in this drug.

Illicit trade in water rights

Beyond arms and drugs, illicit trade also exists in water rights. Since 2005, the Assad regime has limited access to water and requires licences for constructing water wells. This created an illicit trade in water rights, aggravated by corruption since only those who were able to bribe others to build wells gained access to water.

Human trafficking

There also exists an illicit industry to facilitate the movement and trade of people. It is common for individuals to sell their possessions to afford smugglers who can move their families safely. Sometimes, these people are unable to afford their own smuggling, so they be become indebted to the smugglers. This often forces them to work in slave-like conditions to repay their debts once they finally arrive to Europe.

Illicit trade in cultural artefacts

The illegal excavation of Syrian cultural objects from archaeology sites has worsened since the conflict began in 2011, a practice that bears certain similarities with Yemen and the smuggling of historical and cultural artefacts from Saudi Arabia’s southern neighbour. There has been little research into investigating the operation of theft and trafficking of cultural objects inside Syria. With that said, damage to Syrian heritage is well documented and there appear to be links to terrorist organizations who use archaeological raids to fund their wartime campaigns. More research on the illicit trade of Syrian cultural heritage is needed, but it will likely highlight the importance of coins and other small cultural objects in trade.9

Abuse of on-line environment

Finally, it must be noted that greater usage of the internet has worsened the illicit trade situation in Syria. Online illicit trade, largely conducted on the Dark Web, is based on impersonal and anonymised relationships between smugglers and buyers. This has also made tracking illicit trade in Syria harder, since the anonymity of the Dark Web no longer connects payments to nations or traditional currencies. The internet has been most used to facilitate the sale of narcotics, child pornography, sex workers, and steroids.

Quantitative picture – illicit trade in counterfeits in Syria

The OECD customs seizures database provides some insights on trade in counterfeits in Syria. It appears that Syria is a transit point of counterfeit goods. However, while the data on trade from Syria are pretty robust, the quantitative information on imports of fake goods into Syria are rare, presumably due to lack of sufficient governance frameworks in this conflict-affected country.

Regarding exports of fakes from Syria, this economy was the thirtieth provenance economy of global counterfeit goods during the 2017-2019 period (see Table A.2). As regards the imports of fake goods into Syria, the number of related seizures is sparse and all refer to the 2017-19 period meaning this is a quite recent phenomenon. Due to the limited seizures data on imports of fakes into Syria, this perspective will not be subject to further analysis.

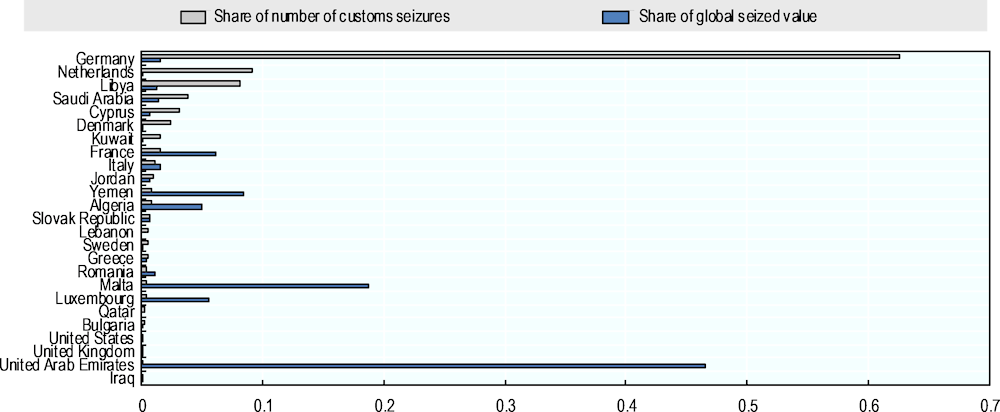

The dataset on customs seizures also indicates that counterfeit goods coming from Syria are mostly destined to European countries (Germany, Netherlands, Cyprus, Denmark, France and Italy) and MENA countries (Jordan, Libya, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar and United Arab Emirates). Over 2011-2019, more than 60% of global customs seizures coming from Syria were destined to Germany (see Figure 4.1). In terms of seized value, one can note the prominent role of the United Arab Emirates (46% of global seized value of counterfeit goods originating from Syria were destined to this country).

Figure 4.1. Destination economies of counterfeit products originating from Syria, 2011-19

Source: OECD global customs seizures database

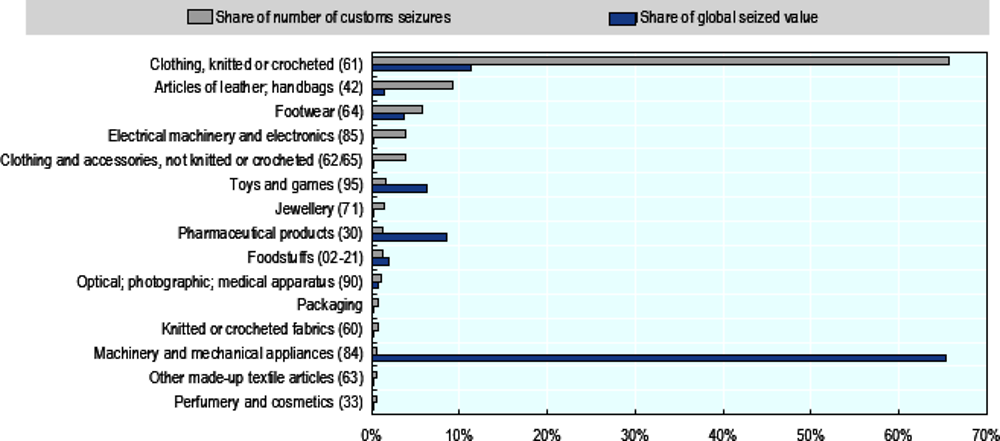

Regarding the product categories of counterfeit goods originating from Syria, the data on customs seizures indicate that fake clothing (66% of global customs seizures originating from Syria) was the most frequent type of good exported by Syria (see Figure 4.2). It was followed by leather goods footwear and electrical machinery and electronics. Counterfeit machinery and electrical appliances (65% of global seized value of counterfeit goods originating from Syria) were the most traded in terms of seized value.

Figure 4.2. Product categories of counterfeit products exported by Syria, 2011-19

Source: OECD global customs seizures database

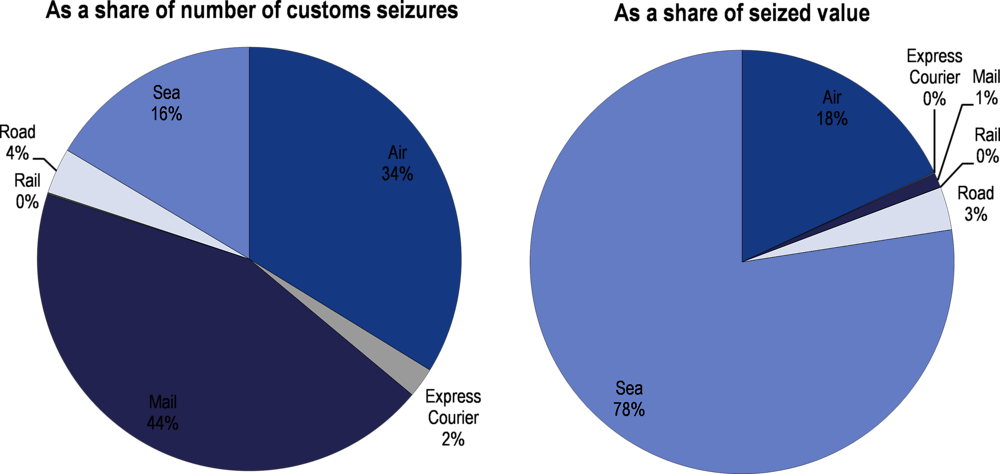

As can be seen in Figure 4.3, mail (44% of global customs seizures coming from Syria), air (34%) and sea (16%) were the most frequently used transport modes to export counterfeit goods from Syria.

Figure 4.3. Conveyance methods of counterfeit goods originating from Syria, 2011-19

Source: OECD global customs seizures database

Notes

← 1. See https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/24/world/middleeast/syria-war-iran-russia-turkey-cease-fire.htm

← 6. See https://coar-global.org/2021/04/27/the-syrian-economy-at-war-captagon-hashish-and-the-syrian-narco-state/