In the recovery path from the COVID-19 pandemic, Central Asia has shown unexpected resilience to the new economic headwinds brought by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While governments moved rapidly to respond to the shocks of pandemic and war and improved elements of the business environment, structural reforms in the region are advancing more slowly. More effective implementation, heightened public-private dialogue and increased transparency in policymaking could lay the foundations for a more robust and healthy business environment.

Improving the Legal Environment for Business and Investment in Central Asia

1. Setting the scene

Abstract

The region has not been spared the consecutive economic shocks resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and the effects of Russia’s war in Ukraine

The economic effects of the pandemic exacerbated fundamental structural weaknesses across the countries of Central Asia

The COVID-19 pandemic was arguably the biggest economic shock hitting post-independence Central Asia. Beyond its human toll, the pandemic created both demand and supply shocks. Domestic and external demand fell, production and trade flows were disrupted, and financial conditions tightened (IMF, 2020[1]). Oil exporters like Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan faced the additional shock of plummeting oil prices due to decreased global demand. Economic policy responses consisted of temporary fiscal measures to support vulnerable households and small businesses. Liquidity support, concessional lending to banks and loan repayment deferrals served to support the private sector. However, limited fiscal space and weak transmission mechanisms for monetary policy highlighted the cost of insufficient structural reform efforts across the region, against the backdrop of declining effectiveness of traditional drivers of growth – the export of surplus labour and extractive goods – before the pandemic (OECD, 2021[2]).

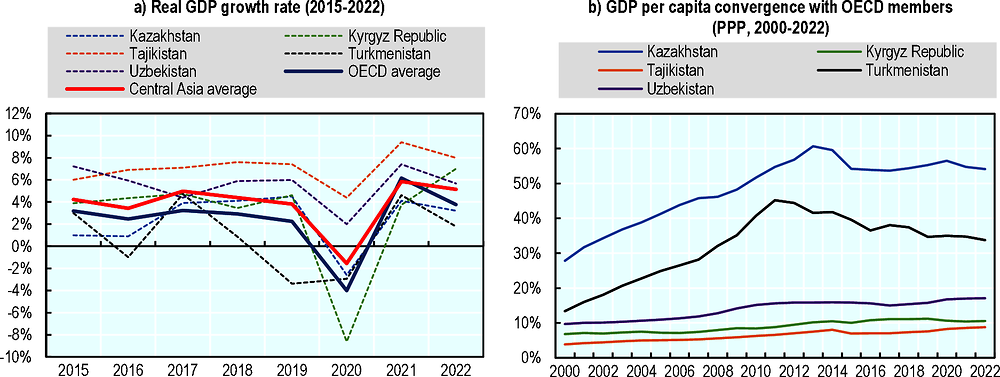

Figure 1.1. Economic growth in Central Asia

Note: Panel b) shows countries’ GDP per capita (in purchasing power parity) as a share of OECD members’ average GDP per capita (PPP).

Source: (IMF, 2023[3])

The economies of Central Asia still managed to recover rather rapidly following the phase-out of lockdowns. Cyclical factors, namely the normalisation of domestic activities, higher commodity prices and recovering remittances, allowed the region to expand again (EBRD, 2021[4]). However, strained public finances and higher debt levels resulting from large stimulus packages and reduced tax collection left the region vulnerable to potential economic shocks. Russia’s war in Ukraine, in particular, was expected to have profound negative spill over effects given the region’s trade, investment, energy and labour dependence on Russia.

This resilience has not, however, reversed the slowdown in trend rates of growth and convergence with higher income countries, particularly OECD member countries. Having progressed rapidly since 2000, the convergence progress began to decelerate in 2013 (Figure 1.1). Apart from Kazakhstan, all countries of the region remain below the 50% of the OECD average GDP per capita at purchasing-power parity terms (PPP). Resuming income convergence requires policies to facilitate a shift in growth models for the region, by increasing productivity in sectors generating the most employment and expanding the size of the formal sector, where wages and productivity have been growing.

The region has withstood the effects of Russia’s war in Ukraine so far, but long-term risks to growth remain

Russia’s full-scall invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 did not derail the region’s post-COVID recovery. On the contrary, across most of the region, growth was supported by an important boost to consumption driven by government spending, more demand for services, high remittance inflows, and real public sector wage increases (OECD, 2022[5]). The region also experienced a 20% increase in trade with Russia in 2022 (Foreign Affairs, 2023[6]), as it filled the void created by Western firms’ withdrawal from the Russian market. It also increased exports to the rest of the world, as Central Asia played a new role of a transit platform between their northern neighbour and Europe and started to diversify trade links. Inflation has gradually slowed down thanks to a decrease in international food and energy prices, restrictive monetary policy, and fiscal reforms (IMF, 2023[7])

However, GDP growth is expected to decelerate to 4.6% in 2023 and 4.2% in 2024 in the Caucasus and Central Asia region, reflecting an attenuation of the initial positive spill overs from the war in Ukraine (IMF, 2023[7]). Remittance inflows are already showing a normalisation of their trend. For instance, remittances in Uzbekistan recorded a 21.2% year-on-year decrease in the first half of 2023 to reach 5.2 billion USD (Central Bank of Uzbekistan, 2023[8]), reflecting a return to the usual level of financial inflows. Agriculture and gold production are expected to soften in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan (IMF, 2023[7]). Yet, a high degree of uncertainty still weighs on this forecast. On the one hand, a sharper-than-expected contraction of the Russian economy, sustained inflation and climate-related disasters could negatively affect growth. On the other hand, good harvests, trade, and investment diversion, as well as a continued influx of highly skilled migrants and foreign exchange could further boost demand and increase productivity growth in the region (IMF, 2023[9]).

The longer-term outlook is uncertain. China’s economic slowdown may hit the region’s exports and investment inflows, but deflation could mean a drop in the cost of goods imported into Central Asia and could contribute to decelerating inflation. Looking at the European Union, the impact of clouded economic perspectives could be mitigated by the EU’s need to diversify its energy supplies and its increased trade with Central Asia. Central Asia energy and raw material supplies to the EU have already been on the rise since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Climate change is another concern which requires concerted, regional-level effort to palliate more frequent droughts, extreme weather and energy supply disruptions.

Whilst the economies of the region are expected to continue growing, the current fragmented and volatile context requires governments to accelerate structural reforms in order to support growth and increase resilience. In that regard, achieving the goals of inclusive and resilient economies will require full engagement from the private sector, alongside other structural policies to improve trade facilitation, ramp up diversification, and increase resilience to climate change. Within this context, the OECD has been providing policy advice and support to the region to help the latter advance reforms supporting the development of the private sector, and ultimately of local economies.

The OECD first assessed the legal environment for business and investment in Central Asia in 2020

In 2020, the OECD offered targeted advice to Central Asian governments on improving the legal environment for business

The OECD report on Improving the Legal Environment for Business and Investment in Central Asia provided targeted advice and identified priority reforms for the governments of Central Asia to improve the legal environment for business, tailored to the particularities of each economy. The analysis allowed the OECD to both ascertain the key legal and regulatory barriers to private sector development and investment in Central Asia and to disseminate a number of OECD instruments for the first time in the countries of the region.

Box 1.1. Description of the OECD’s methodology and assessment of the legal environment for business in Central Asia (2019-2020)

Defining the legal environment for business

Given its multidimensional nature, establishing a common understanding of the legal environment for business is a contentious endeavour. For the Improving the Legal Environment for Business in Central Asia project, the “legal environment” encompasses policy, administrative, regulatory, and other legal areas that govern and affect businesses, investment and operations. Leveraging OECD instruments, such as the Policy Framework for Investment, the SME Policy Index, the Trade Facilitation Indicators, and the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, the project examined ten dimensions for analysis: the legal and regulatory frameworks for investment; tax regulations; land legislation; registration procedures; contract enforcement and dispute settlement; the operational environment for business; trade facilitation; expropriation regimes; exit mechanisms; and public-private dialogue.

OECD methodology

The 2020 report was built on two complementary components:

Two questionnaires focused on the ten dimensions noted above were circulated to the governments of participating countries and representatives of the private sector, respectively. The input was collected and analysed by staff at the OECD.

The OECD organised a series of private- and public-sector consultations. In particular, the project organised a workshop in each of the project countries, as well as roundtable meetings with local and international entrepreneurs in each of the countries and at business associations in Paris, and held bilateral meetings with individual policymakers, entrepreneurs, and investors from or active in the region.

Policy support

On the basis of the data collection and analysis conducted, as well as on consultations with governments and with the private sector, the OECD identified three key reform priorities for each country. These priorities took into account the de jure legal environment for business and the de facto operational reality for firms, domestic and international. The OECD has been careful to reflect ongoing reform processes in each country, as well as the activities of donors and other international organisations active in the region.

In 2020 and 2021, the OECD worked with the Central Asia governments on the identified reform priorities, continuing the OECD’s deepening co-operation with a dynamic region through a series of capacity-building exercises with each country focusing on the priorities identified. In addition, a regional two-day event focussing on contract enforcement was organised in 2020, gathering policymakers from the region, academics and international experts for experience sharing.

Source: (OECD, 2020[10]).

The original report identified significant gaps between de jure protections and the de facto operational environment for firms

Table 1.1. Top challenges identified in the legal environment for business and investment in Central Asia in 2020

|

Kazakhstan |

Kyrgyzstan |

Tajikistan |

Turkmenistan |

Uzbekistan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Operational environment for firms Implement consistently and thoroughly the new code for entrepreneurs |

Operational environment for firms Streamline the legal environment for entrepreneurs and small businesses, especially legislation and service delivery |

Legal and regulatory framework for investment Ensure the implementation of existing laws for investment and entrepreneurial activity, and improve the accessibility of necessary information |

Legal and regulatory framework for investment Enforce, streamline, and publish all legislation on investment on the Ministry of Justice’s legal database to ensure transparency |

Legal and regulatory framework for investment Ensure proper implementation of the new investment law and remove sectoral restrictions |

|

Legal and regulatory framework for investment Improve dispute settlement for all businesses operating in the country |

Contract enforcement Ensure transparent fair and efficient contract enforcement for businesses |

Contract enforcement Improve the enforcement of contracts and arbitral decisions in domestic courts |

Operational environment for firms Develop a simplified targeted legal framework and support for SMEs and small entrepreneurs |

Operational environment for firms Streamline and consolidate business-related legislation and licenses for domestic firms and entrepreneurs |

|

Trade facilitation Enhance trade facilitation and improve cooperation between agencies involved in export procedures |

Taxation Simplify the tax code and tax administration for companies of all sizes |

Taxation Make tax administration simpler, more consistent and more transparent |

Business registration Streamline business registration and licensing, and introduce a one-stop-shop |

Taxation Ensure changes to tax requirements are predictable, and improve tax administration for small firms |

Source: (OECD, 2020[10]).

The OECD assessed progress made and new challenges arising in the legal environment for business in Central Asia since 2020

The report finds improvements in the operational environment for business driven by digitalisation, a streamlining of procedures, and adaptation to economic shocks

Efforts to streamline the operational environment have eased the administrative burden on firms

Most countries of the region have made significant progress in digitalising and simplifying the provision of government services. In particular, countries implemented measures to streamline the number of licenses and permits required to operate a business, a welcome step mentioned by interviewees during the fact-finding process (Box 1.2). These efforts have also translated into intensified regional integration, as several countries implemented digital trade and customs procedures. For instance, Kazakhstan introduced an electronic queue system, allowing trucks to register at the desired date and time of the border crossings with China, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan (Zakon.kz, 2023[11]). OECD interviewees reported easier border crossing between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. Intra-regional trade increased by 73.4% between 2018 and 2022, from 5.8 billion USD to 10 billion USD (The Astana Times, 2023[12]).

Governments swiftly reacted in the face of a challenging global economic context

In the face of the COVID-19 context, governments managed to rapidly adapt in a volatile context. Restrictive monetary policies and higher reserve requirements contained inflation and excess liquidity (IMF, 2023[9]). Fiscal policy, benefitting from increased remittances (through increased consumption), focussed on measures to support businesses affected by supply chain disruptions, increased costs, and lockdown, and measures to secure food and energy supplies, ensure price stability and increased agriculture output. The vacuum created by the withdrawal of Western firms from the Russian market created new export opportunities for Central Asian firms (EBRD, 2023[13]). Efforts to diversify trade routes through the Middle and Southern Corridors have helped mitigate to some extent disruptions along the Northern Corridor going through Russia (OECD, 2022[5]).

However, deeper reforms are taking time to materialise

Recent economic disruptions have hindered governments’ efforts to advance more profound reforms. The prevalence of the state in the economy and the lack of competitive neutrality remain roadblocks to the creation of a level playing field between state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the private sector. The investment framework is still challenging, due to perceived risks of indirect expropriation and opaque privatisation and public procurement processes. Strains on public finances have led to undue pressures on businesses to pay taxes early or to wait for long periods to receive VAT returns.

Weak implementation remains a key challenge for firms across the region

An issue already identified in the initial OECD report relates to the implementation of legal provisions. Whilst the formal statutory conditions for businesses may somewhat guarantee the freedom to do business, the de facto operational environment remains complicated, changeable, and often opaque. This is demonstrated in the unpredictability of tax systems, and divergences in statutory interpretation. With regards to investment, whilst the framework is quite open, as shown by the region’s performance in the OECD’s FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, its application remains problematic for foreign investors, which continue to struggle with the challenges of transparency in public procurement, information availability, corruption and the prevalence of the state in the economy through SOEs.

Whilst public-private dialogue has been improving across the region, regulations are subject to frequent changes and the private sector is often given little notice to implement changes. Frequent changes, such as in tax policy, with little time for firms to adapt, result in implementation challenges, risks of noncompliance and fines. The rapidity of changes also poses difficulties for ministries and government agencies to integrate updates into processes and harmonise interpretation. An issue frequently raised by firms relates to the lack of agreement within the public administration on the interpretation of primary and secondary legislation. Firms have often found themselves faced with conflicting instructions from different government agencies and civil servants.

The lack of transparency around decision-making and incentive allocation also creates a roadblock to firms’ voluntary compliance with the law. Governments have started to rely on regulatory impact assessment (RIA) to assess the positive and negative effects of proposed and existing regulations and make policymaking evidence based. However, firms have reported that the results of such RIAs are not always integrated into policy and that RIAs are sometimes carried out with predetermined policy objectives, which influence the outcome of the RIAs. This reduces the effectiveness of the exercise and does not encourage compliance, as firms are not convinced of the expected positive effects of conducting RIAs on the operational environment. In addition, the reported existence of sometimes unpublished or unavailable decrees granting favourable conditions to SOEs, such as tax breaks and preferential lending conditions, distorts competition and further discourages compliance with legal provisions.

The 2023 assessment of progress made since 2020 has allowed to update and fine-tune the recommendations for each country of the region

Box 1.2. Description of the OECD methodology for the 2023 monitoring of the legal environment for business and investment in Central Asia

OECD methodology

The monitoring exercise relied on several tools:

a matrix table of the 2019-2020 recommendations with preliminary desk research to tentatively identify areas of progress in each country of the region;

a series of written questionnaires circulated to the five governments of Central Asia;

a series of fact-finding online interviews with private sector and international organisation representatives in the region;

open access quantitative data;

in-person working group meetings in each country of the region to discuss the preliminary findings and give the opportunity for government and private stakeholders to complement and/or comment on the analysis.

Note: For further details on the methodology, please refer to Annex A of the report

The table below summarises progress made along the priority reform areas identified in the 2020 report for each of the five countries of the region, before delving into each country’s individual assessment. It also provides updated recommendations per country. Going forward, the final chapter of the report suggests revised overarching policy recommendations for the region to lay the foundations for the development of a vibrant and inclusive private sector. Overall, the assessment finds that reforms have been initiated to digitalise public services, facilitate trade, reduce the number of redundant procedures and improve fiscal policy, however, gaps remain in the implementation and interpretation of the text. Tax administration has also been mentioned as particularly problematic by private sector interviewees.

Table 1.2. Overview of reform implementation

|

Kazakhstan |

Kyrgyzstan |

Tajikistan |

Turkmenistan |

Uzbekistan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Operational environment for firms Regulation became more transparent and equitable, but implementation lags behind and complexities remain |

Operational environment for firms The government's digitalisation efforts have begun to bear fruit, but further streamlining of business-related legislation and predictable enforcement are needed |

Legal and regulatory framework for investment The investment framework has seen some progress, yet restrictions and uncertainties still need addressing |

Legal and regulatory framework for investment The government has increased communication about changes in the law, but reform efforts seem to have slowed down due to the COVID-19 pandemic |

Legal and regulatory framework for investment Significant reforms to increase investor protection rights were undertaken but a lack of transparency remains |

|

Contract enforcement Judicial and dispute resolution reforms have been advanced in priority by the government, but contract enforcement and dispute resolution continue to be perceived as a major challenge for businesses |

Contract enforcement The judicial system is evolving, but further steps to ensure predictable, fair and effective enforcement of treaties would be preferable |

Contract enforcement The legal framework for businesses has registered some improvements, dispute resolution mechanisms need strengthening |

Operational environment for firms The post-pandemic period has provided some relief to businesses, but the business environment remains difficult to navigate |

Operational environment for firms The streamlining of procedures and legislation has made significant progress, yet the pace of reforms creates implementation challenges, and land and property rights remain an issue |

|

Trade facilitation The trade regulatory framework improved, especially with digitalisation and for IP rights, but implementation lags and regulatory barriers to services trade remain |

Taxation New amendments to the Tax Code aimed at creating conditions to level the playing field for businesses, but tax administration and policy remain complex and unpredictable |

Taxation Fiscal policy developments have reduced the tax burden on firms; however, tax administration remains the most contentious issue mentioned by firms |

Business registration The government has revised and simplified some procedures for business registration and licensing, but procedures are still paper-based and cumbersome |

Taxation Fiscal policy developments have reduced the tax and administrative burden on firms; however, tax administration remains the most contentious issue mentioned by firms |

Source: OECD analysis (2023).

References

[8] Central Bank of Uzbekistan (2023), Приток денежных переводов сократился более чем на 20% — ЦБ, https://www.spot.uz/ru/2023/07/27/remittances/ (accessed on 31 July 2023).

[13] EBRD (2023), Regional Economic Prospects: Getting By - High Inflation Weighs on Purchasing Power of Households, https://www.ebrd.com/rep-may-2023.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2023).

[4] EBRD (2021), “Bittersweet recovery”, Regional Economic Prospects, https://www.ebrd.com/sites/Satellite?c=Content&cid=1395301907147&d=&pagename=EBRD%2FContent%2FDownloadDocument.

[6] Foreign Affairs (2023), Is Russia Losing its Grip on Central Asia, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/russia-losing-its-grip-central-asia (accessed on 5 October 2023).

[7] IMF (2023), Regional Economic Outlook for the Middle East and Central Asia - Building Resilience and Fostering Sustainable Growth, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/MECA/Issues/2023/10/12/regional-economic-outlook-mcd-october-2023 (accessed on 13 October 2023).

[9] IMF (2023), Safeguarding Macroeconomic Stability amid Continued Uncertainty in the Middle East and Central Asia, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/MECA/Issues/2023/04/13/regional-economic-outlook-mcd-april-2023 (accessed on 31 July 2023).

[3] IMF (2023), World Economic Outlook Database, April, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/April/download-entire-database.

[15] IMF (2022), “Financial Development and Growth in the Caucasus and Central Asia”, IMF Working Paper, Vol. 22/134, https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2022/English/wpiea2022134-print-pdf.ashx.

[1] IMF (2020), COVID-19 Pandemic and the Middle East and Central Asia: Region Facing Dual Shock, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2020/03/24/blog-covid-19-pandemic-and-the-middle-east-and-central-asia-region-facing-dual-shock (accessed on 31 July 2023).

[14] OECD (2023), Insights on the Business Climate in Kazakhstan.

[5] OECD (2022), Assessing the impact of the war in Ukraine and the international sanctions against Russia on Central Asia, https://www.oecd.org/migration/weathering-economic-storms-in-central-asia-83348924-en.htm.

[2] OECD (2021), Beyond Covid-19: Prospects for Economic Recovery in Central Asia.

[10] OECD (2020), Improving the Legal Environment for Business and Investment in Central Asia, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/Improving-LEB-CA-ENG%2020%20April.pdf.

[12] The Astana Times (2023), Five Trade Trends in Central Asian Connectivity, https://astanatimes.com/2023/06/five-trade-trends-in-central-asian-connectivity/ (accessed on 5 October 2023).

[11] Zakon.kz (2023), New rules: how to book an electronic queue for crossing the state border, https://www.zakon.kz/pravo/6390366-novye-pravila-kak-zabronirovat-elektronnuyu-ochered-dlya-peresecheniya-gosgranitsy.html (accessed on 1 August 2023).