Marcela Valdivia

OECD

Alicia Adsera

School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University

Marcela Valdivia

OECD

Alicia Adsera

School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University

This chapter explores the relationship between family formation and labour market outcomes among migrant women. After analysing the short- and longer-term effects on employment outcomes, it presents the factors shaping these results: from individual characteristics to institutional arrangements (parental leave, formal childcare and part-time arrangements). Finally, the chapter reviews some of the policies to support the employment of migrant mothers, focusing on the best practices.

Gender gaps in labour market outcomes persist despite educational gains among native‑ and foreign-born women. The effect of children – known as motherhood or child penalties – largely accounts for the remaining gaps and tends to be more pronounced for migrant women.

Roughly half of migrant mothers with small children (0‑4) are employed in OECD countries, a 20 percentage point gap compared to their native‑born peers. Belgium, France, Germany and Slovenia display the highest employment gaps, exceeding 30 percentage points; Hungary, the Czech Republic, Chile and Costa Rica, the lowest, and not exceeding 10 percentage points.

The employment of migrant mothers is more sensitive to the age and number of children compared to their native‑born peers, suggesting that childcare constraints are higher for the former. Migrant mothers also report higher levels of involuntary part-time employment: one in four would like to work more hours, compared to one in seven of their native‑born peers. While individual preferences and cultural factors are often cited as main barriers to maternal employment, these indicators suggest that migrant mothers are often trapped in inactivity due to childcare responsibilities.

Migrant mothers’ labour supply responds to various factors: family formation immediately after arrival limits the accumulation of human capital and time spent in the labour market before childbirth which, in turn, restricts access to parental leave policies. Once employed, elementary occupations – in which they are overrepresented – offer little financial incentive or institutional support to return to work after childbearing.

Migrant mothers tend to use formal childcare at lower rates than their native‑born peers and often face barriers to access, including financial costs, lack of institutional knowledge and language barriers, shortage of publicly subsidised spaces and/or lack of culture‑sensitive provision. As family networks are more limited for them, migrant mothers also rely less on informal childcare arrangements.

The employment of migrant mothers has positive implications on the labour market outcomes of their children, showcasing the importance of role modelling. For native‑born women with at least one parent born outside the EU, having a working mother during adolescence is associated with an increase of 13 percentage points in their employment rate. The positive association is particularly large in Germany (18 percentage points).

The employment of migrant mothers (and migrant women, more generally) in domestic and care services also increases the availability of these services, allowing parents – both foreign – and native‑born – to reconcile family responsibilities and paid work, and raising female employment.

As family formation and migration tend to be intertwined processes for many female migrants, it is essential to account for both processes simultaneously when thinking of integration. Pre‑departure counselling as well as targeted support immediately after arrival are complementary measures towards facilitating employment.

Countries can remove obstacles faced by migrant mothers to participate in integration programmes, notably through flexible modalities, extended timelines, the provision of childcare services and/or lowering the threshold of participation. Several countries also offer integration support in preschool settings, targeting both parents and children simultaneously.

The inclusion of women in the labour market is an important objective for equity considerations alone, but improved female labour market outcomes are also needed to ensure continued economic growth (OECD, 2023[1]). Ageing populations and declining fertility rates – as evidenced in the previous chapter – mean that many countries will face a shrinking labour force in the coming years. In this context, women – and migrant women in particular – represent a significant, under-utilised source of skills.

In recent years, the educational achievement of girls has taken over that of boys in most OECD countries, but women’s position in the labour market severely lags behind that of men (OECD, 2018[2]). Recent OECD work shows that remaining gender gaps can be significantly attributed to the effect of children (OECD, 2023[1]). Women who are mothers are more likely than childless women to work fewer hours, earn less than men, or opt out of the workforce entirely. The effect of children on labour market outcomes – often known as child or motherhood penalty – is also more pronounced for migrant women, but thus far research and attention from policy makers have been limited.

Across OECD countries, about half (52%) of foreign-born women with small children (0‑4) are employed, a 20 percentage point gap compared to native‑born mothers of the same age group (25‑54). The employment gap between mothers and childless women is also twice as large for migrant women than for their native‑born peers (‑19 percentage points versus ‑9, respectively). While low employment among migrant mothers may reflect general factors affecting migrant labour market outcomes – lack of country-specific human capital and labour market experience, limited information and social networks, discrimination – the intersection of gender, migration and family formation also shapes specific constraints that require attention.

The labour force participation of migrant mothers responds to various factors such as the connection between migration and family formation, which may lead to childbearing immediately after arrival, restricting women’s ability to acquire country-specific human capital and experience (see previous chapter); lower access to and uptake of family policies; lack of family networks, often critical in the provision of childcare; different social and gender norms influencing fertility choices and female employment; and lower socio‑economic status or labour market attachment before childbirth. All these factors, explored across this chapter, contribute to explaining the large variation in how women respond to labour market incentives and enter and exit the labour market upon family formation.

Removing barriers to the reconciliation between paid work and family responsibilities is particularly important for migrant women and society as a whole as:

Reduced labour market participation among mothers translates into foregone wages and experience at the individual level, as well as reduced household income and underutilised human capital at the societal level. This is especially true for migrant women who, on average, are more educated than their male counterparts across the OECD area (OECD, 2020[3]).

Despite the emphasis on the role of origin culture in the public debate,1 evidence shows that institutional arrangements and job opportunities are also important in explaining how migrant women adapt their labour supply to family circumstances. In Canada, six in ten migrant mothers (with children under six) report willingness to work but not being able to do so due to childcare responsibilities. In the European OECD countries, the same is true for one in five migrant mothers of children under 14.

Time use is more gendered among migrants than among the native‑born, meaning migrant women tend to spend more time doing housework than their native‑born peers. The relationship between housework and earnings is key to understanding migrants’ integration as this type of work significantly contributes to decreasing wages for migrant women (Fendel, 2021[4]).

Language plays a key role in the creation of community and a sense of belonging, but migrant women who remain in the household to attend to family responsibilities can find themselves in isolation, with few opportunities to learn or practice the host language (OECD, 2021[5]).

Migrant women’s access to the labour market is critical for their children’s educational success and future labour market outcomes. Mothers’ employment decisions can positively influence attitudes within their own families and lead to a more gender egalitarian division of work.

The key questions this chapter seeks to discuss are the following: what is the relationship between childbearing and labour market outcomes of migrant women in the short and long term? How do these trends differ from native‑born mothers? What factors shape maternal employment rates among migrant women? What are the main factors hindering access to family policy among migrant families? What mainstream and other policies are in place to support the employment of migrant mothers and what do we know about their impact?

The first and second parts summarise the short- and longer-term effects of family formation on the labour force participation of migrant mothers, respectively, and how these effects compare to those observed among their native‑born peers. The third part looks at factors shaping labour market outcomes for migrant mothers: human capital, sector and quality of jobs, migration channel and individual preferences. The fourth section describes how migrant women fare in terms of access to and uptake of family policy, focusing on parental leave and formal childcare. Finally, the chapter reviews some of the policies implemented by OECD countries to support the employment of migrant mothers focusing on the best practices.

Earlier research emphasised the role of human capital in explaining gender inequality in the labour market (both in terms of participation and earnings), but educational gains for women in the latest part of the 20th century have put alternative explanations at the centre (Blau and Kahn, 2017[6]). Persistent gender gaps in employment are now largely attributed to the effects of children on women’s careers (Kleven, Landais and Sogaard, 2019[7]). The so-called child or motherhood penalty can be understood as the impact of children on the labour market trajectories of women relative to men or relative to women with no children.

This impact may translate into lower employment, a reduction in the number of hours worked, and/or loss of earnings. The latter result from mothers’ reduced labour force participation, but the penalty has proven to persist even after controlling for forgone work experience, education, training and reduced hours (Budig, Misra and Boeckmann, 2012[8]). The mechanisms to explain the motherhood penalty range from loss of human capital due to prolonged periods of leave, employers’ discrimination and choice of sectors or job types that allow more flexibility for family care at the expense of higher wages. All these effects are not short-lived and tend to have enduring consequences spanning a woman’s career (Bazen, Joutard and Périvier, 2021[9]).

The extent to which mothers participate in the labour market responds to a combination of observable sociodemographic characteristics at the individual level, as well as unobservable individual preferences. In addition, whether a mother works also depends on the support of family policies, which tend to have a broad set of objectives, among which raising female employment may be only one. In this regard, the effectiveness of family policies depends on their degree of coherence with other policies. Access to formal childcare, for instance, boosts maternal employment when taxation and parental leave policies are also supportive (Adema, Clarke and Thévenon, 2020[10]).

This chapter compares the labour market participation of migrant mothers with that of their native‑born peers. It considers sociodemographic differences and how both groups fare in different domains of family policy – access to early childhood education and care (ECEC), parental leave and part-time arrangements. Given that the chapter focuses on cross-country variation in maternal employment rates, it mostly employs cross-sectional data, which can be informative about women’s situation in the labour market at different times in their careers and allow comparing sub-populations across various dimensions of labour force participation. The influence of family structures and roles are not analysed in this chapter.

Calculating the actual effect of childbirth on employment outcomes among migrant women, and among women in general, poses methodological challenges. In general, the negative association between labour force participation and childbearing may be driven by causal influences in either direction or by additional factors that affect both, such as gender norms that may increase childbearing preferences and discourage maternal employment (see section on individual determinants for a definition of gender norms). Research that has tried to control for many of these factors and establish a “causal” impact of motherhood found that it is sizeable and has not decreased over recent years despite gains of women on other margins (Cortes and Pan, 2020[11]; Kleven, Landais and Sogaard, 2019[7]; Kleven et al., 2019[12]; Holland and de Valk, 2017[13]).

For migrant women, gender norms comprise not only those prevailing at destination but also those from their origin country because socialisation occurs from a very young age and migrants tend to carry with them the norms and values from their home countries. In addition, a proper analysis of mothers’ career paths would ideally involve observing their complete working lives and comparing them with those of childless persons with otherwise similar individual characteristics. This exercise would allow one to observe career path dependencies and the causal effect of children. But due to data limitations, such as lack of longitudinal data, most studies use cross-sectional approaches comparing parents with childless peers, where the effect of family formation can be confounded with selection effects or with structural factors that already determine employment positions before parenthood (Kil et al., 2017[14]).

Overall, the limited research on motherhood and migration has attempted to explain differences between native‑ and foreign-born populations through the role of policies and institutions; gender norms influencing fertility behaviour and the allocation of time between unpaid care and paid work; or path dependencies determined by the timing of family formation, socio‑economic status or unstable labour market trajectories before childbirth. Few studies use longitudinal data, explore the role of partner’s employment or distinguish between full- and part-time employment (Maes, Wood and Neels, 2021[15]). To try to overcome this shortage of suitable data, a new line of research has recently introduced an event-study approach around the birth of the first child to estimate the motherhood penalty employing cross-sectional data. The approach consists in creating a synthetic population of “future parents” who are observably similar to the observed parents and analysing the change in employment and earnings of men and women after childbirth (Kleven, 2022[16]).

Economic theories dating back to the 1970s suggest that within couples, women tend to increase their participation in household-related activities at the expense of their labour force participation due to implicit comparative advantages of men and women in these two spheres. Intra-household specialisation increases particularly upon childbearing (Becker, 1985[17]). Because individual (potential) earnings tend to determine the allocation of time within a household, family formation and labour force participation have often been viewed as competing paths in the life course of a woman (Andersson and Scott, 2007[18]).

However, increased access to subsidised formal childcare and paid parental leave, among other things, have gradually enabled the combination of paid work for women and family formation. In parallel, educational gains among women have increased their potential wages and consequently the costs of dropping out of the labour force after childbearing (Kleven, 2022[16]). Indeed, across OECD countries, both native‑ and foreign-born women are, on average, more educated than their male peers, especially among the younger cohorts (OECD, 2019[19]; OECD, 2020[3]). Despite this, mothers – and migrant mothers in particular – still display lower employment rates than childless women.

Reduced labour market participation among mothers translates into foregone wages at the individual level, increased costs at the household level and underutilised human capital at the societal level. According to data from the 2019 EU labour force surveys, if barriers to work were removed among migrant mothers who report willingness to work and are unable to do so, European OECD countries could gain an additional 1.5 million workers. The number would increase to approximately 5 million if the employment rates of migrant mothers (with children under 14) rose to the levels of their native‑born peers.

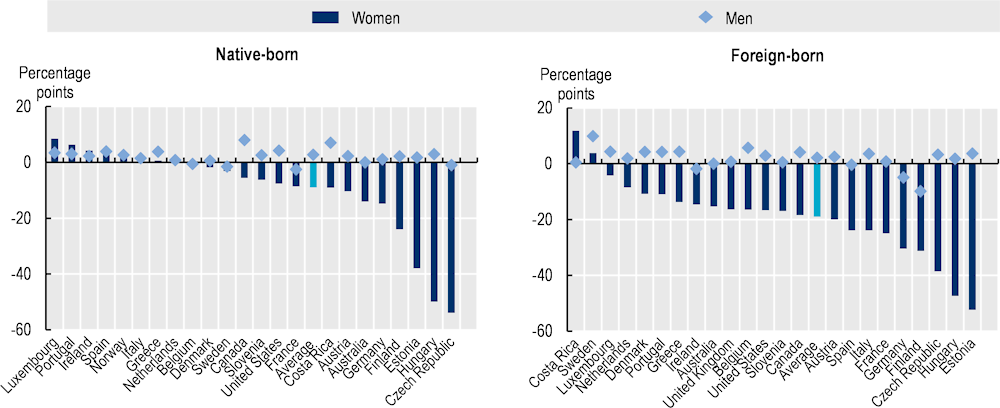

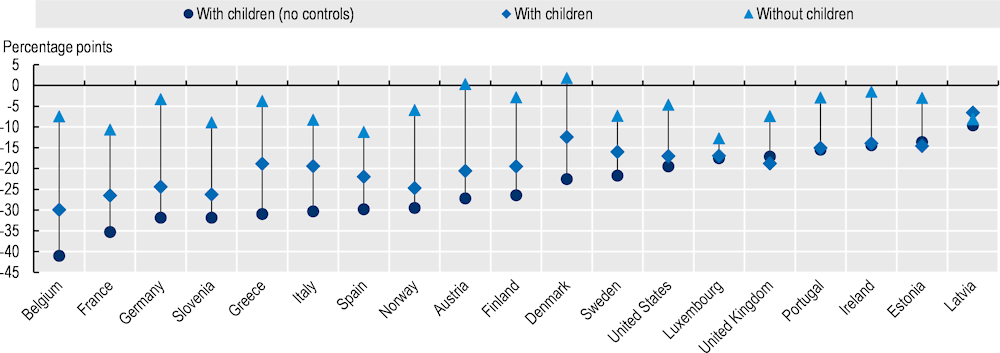

Figure 5.1 provides a first assessment of the role of childbearing in women’s careers by showing differences in employment rates between childless men and women, on the one hand, and parents of small children, on the other. Differences are not adjusted by age, education or number of children as these factors are explored below. Data only refer to partnered individuals, as the constraints faced by single women when making labour market decisions are likely to differ from those in a couple.

Note: Partnered individuals refer to those either married or in union. Parents are individuals with children aged 0‑4 in EU countries, 0‑6 in Canada, and 0‑5 in the United States. Positive values mean higher employment rates for parents.

Source: Eurostat (2019[20]), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey; Statistics Canada (2019[21]), Labour Force Survey (LFS), https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/type/data; INEC (2021[22]), Encuesta Continua de Empleo (ECE), http://sistemas.inec.cr/pad5/index.php/catalog/REGECE; US Census Bureau (2019[23]), Current Population Survey (CPS), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html.

In the great majority of countries,2 mothers consistently display lower employment rates than their childless peers regardless of their migration status. In the Czech Republic, Estonia and Hungary, for example, employment gaps exceed 30 percentage points for both native‑ and foreign-born women. Yet, the overall penalty is highest for migrant mothers: on average, their employment rate is 19 percentage points lower than for migrant women with no children, compared to an employment gap of 9 percentage points between native‑born women with and without a child. In contrast, the employment rate of men is either virtually not affected by paternity and, in most cases, is associated with a premium, regardless of migration status.3

Unless otherwise specified, maternal employment is defined as employment-population ratios for women of prime working age with at least one child aged 0‑4. The employment gap is an approximate measure of the effect of having a child on women’s employment and allows comparing employment rates for native‑born mothers relative to migrant mothers in the same country. The analysis focuses on mothers with small children because the migrant-native differentials around this age group tend to be the widest: the demand for care is particularly high at this stage of the child’s development; gender norms regarding working mothers are arguably the strongest when children are very young; and women, in general, do not appear to anticipate the associated costs of motherhood. The focus on prime‑working age allows to observe women during a period when they are likely to have completed formal schooling and may face childcare obligations, while ruling out a substantial outflow from employment into retirement.

There are, however, important methodological issues to consider in cross-country comparisons of maternal employment rates. Up until 2021 when harmonised data became available, many OECD countries followed ILO guidelines and counted individuals on full-time statutory (legal or contractual) maternity leave and those on full-time statutory (legal or contractual) parental leave as employed, as long as they were either expected to be on leave for a three‑month period or less or continued to receive 50% of their wage and salary. Some countries, however, followed other rules: in Sweden, for instance, all parents on parental leave were counted as employed regardless of the length of the leave as long as they had a (regular) job to return to. Norway set an upper limit in the length of leave (12 months), after which women in leave were counted as employed only if they received at least 50% of their salary. Conversely, in Estonia, all individuals on parental leave were considered inactive (see OECD Family Database). Because this chapter mostly relies on 2019 data, these differences must be considered when interpreting data.

The literature shows that the “child effect” varies across high-income countries and such differences have been mainly attributed to the structure of the labour market and institutional arrangements (namely, the provision of formal childcare and access to other family policies). But the effect has also proven to diverge across women with different educational backgrounds, household composition, and migrant or ethnic origin, suggesting that institutions critically interact with individual preferences.

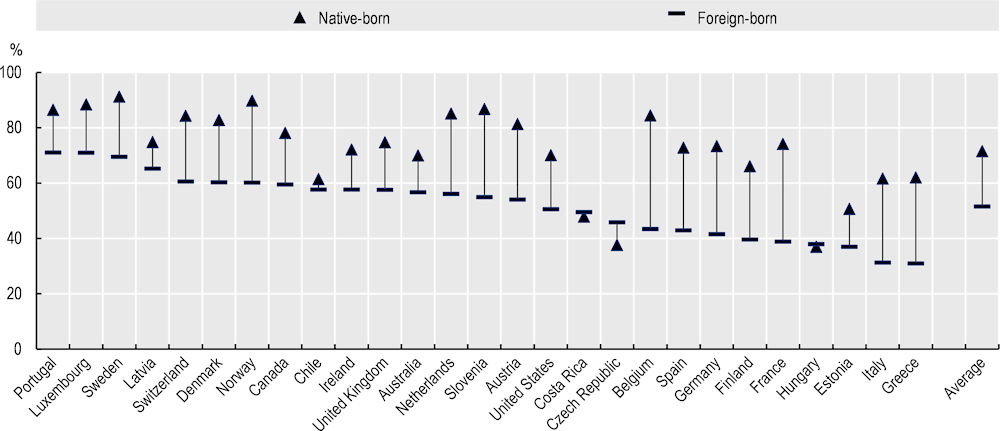

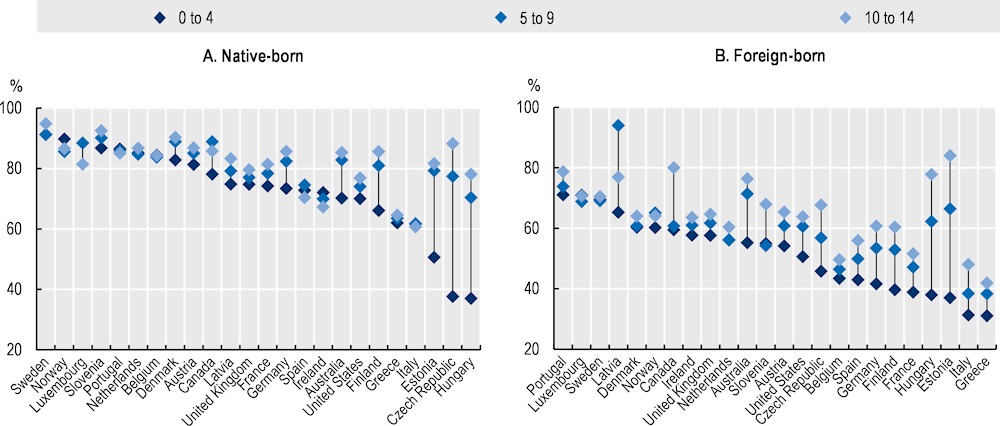

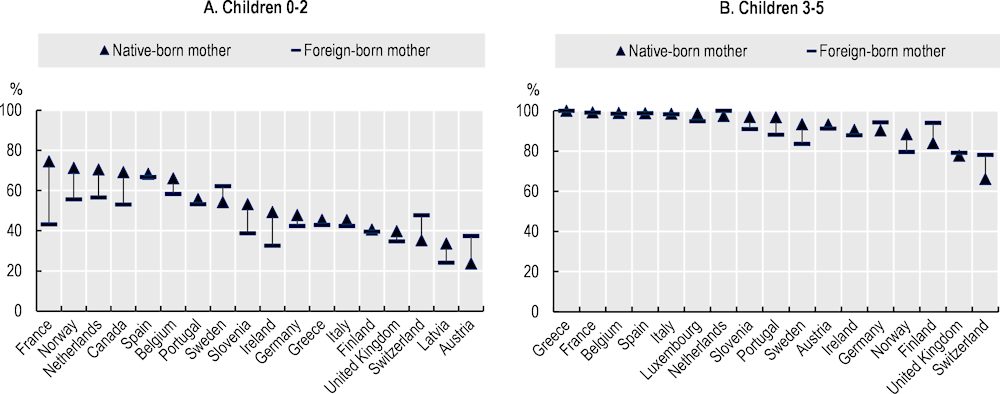

On average across OECD countries, 52% of migrant women with small children are employed, compared to 72% of their native‑born peers (Figure 5.2). While in more than half of the countries, the difference between these two groups exceeds 20 percentage points, there is significant cross-country variation. At one extreme, Belgium, France, Germany and Slovenia exhibit the largest differentials: the employment rate of migrant mothers is, respectively, 41, 35 and 32 percentage points lower than that of their native‑born peers. Conversely, countries from Central and Eastern Europe – Hungary, the Czech Republic and Latvia – and Latin America – Chile and Costa Rica – display the smallest native‑migrant gaps. Overall, gaps persist when controlling for age, education and number of children (Annex Figure 5.A.1 in Annex 5.A).

In Hungary and the Czech Republic, small gaps are also associated with low maternal employment rates for native‑born women. Even though Central and Eastern European countries have been distinguished by high, full-time employment rates among women since the late 1950s, maternal employment rates in Hungary and the Czech Republic have consistently remained low (Javornik, 2016[24]). Both countries are characterised by policies that support family caregiving: long parental leaves4 and family cash benefits, which encourage the second earners in the household (usually mothers) to leave the workplace for prolonged periods and care for children at home (OECD, 2016[25]). Not surprisingly, enrolment rates in ECEC for very small children (0‑2) are some of the lowest among OECD countries (6 and 12% for the Czech Republic and Hungary, respectively). Further, highly educated mothers in Hungary with very small children only fare slightly better than their low-educated peers, thus contributing to reducing the migrant-native gap as well (OECD, 2022[26]).

In Chile and Costa Rica, as in most Latin American countries, mothers find in informal jobs the flexibility needed for family-work balance, at the cost of poor employment conditions and prospects (Berniell et al., 2019[27]). Job opportunities in the informal sector, where migrant women are generally overrepresented, contribute to lowering the employment gaps between native‑ and foreign-born mothers.5

Note: Data cover women aged 25‑54 (15‑64 in Switzerland). Mothers are defined as women with at least one child aged 0‑4 (0‑5 in the United States and 0‑6 in Canada and Switzerland). For Costa Rica, data only cover mothers who are reported as the head of the household or the spouse/partner of the head of the household.

Source: ABS (2019[28]), Labour Force Status of Families, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-status-families; Statistics Canada (2019[21]), Labour Force Survey (LFS), https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/type/data; Government of Chile (2020[29]), Encuesta de Caracterización Socioeconómica Nacional (CASEN); INEC (2021[22]), Encuesta Continua de Empleo (ECE), http://sistemas.inec.cr/pad5/index.php/catalog/REGECE; Eurostat (2019[20]), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey; FSO (2021[30]), Swiss Labour Force Survey (SLFS), https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/work-income/surveys/slfs.html; US Census Bureau (2019[23]), Current Population Survey (CPS), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html.

Conversely, in Belgium, France, Germany and Slovenia, low maternal employment rates among migrants contrast with above‑average rates for native‑born mothers, suggesting that women face migrant-specific challenges in these labour markets. A combination of factors, explored across the chapter, include:

frequent shortages in the supply of public places in ECEC, particularly for very young children (Germany and France), which disproportionately affect lower income families;

financial incentives in the form of home care allowances (Belgium, Germany,6 Slovenia), to which individuals with low labour market integration and higher barriers to accessing formal childcare may be more sensitive;

compositional factors, including relatively higher shares of women who migrate for family reasons (France and Belgium), humanitarian protection (Germany),7 as well as higher shares of low-educated women in the migration stocks (France, Belgium, Germany);

some of the highest inactivity rates among migrant women (Belgium, France and Germany). In the face of poor employment prospects, migrant women and especially those with low human capital, may choose the “motherhood track”;

well-paid maternity leaves and employment-related criteria to access it (Belgium, France, Germany, Slovenia). The latter has been associated with higher migrant-native gaps in access.

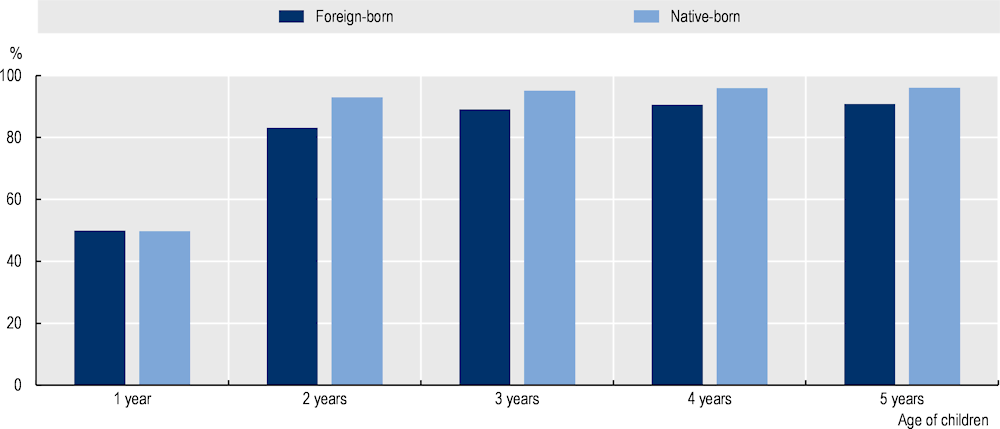

The age and number of children in the household also influence women’s decision to participate in the labour market. Because the number of children tends to differ between native‑ and foreign-born households, these compositional differences are also important when explaining maternal employment rates among both groups (Khoudja and Fleischmann, 2017[31]). For instance, foreign-born women are, on average, twice as likely to have a small child compared to their native‑born peers of the same age.

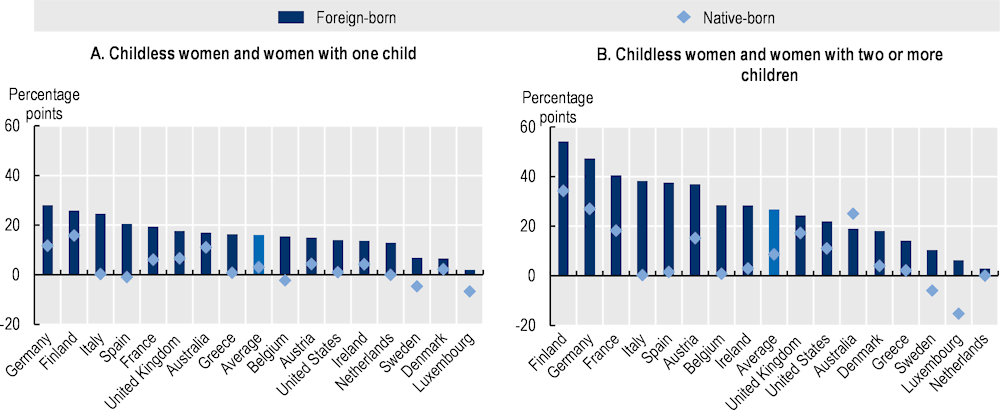

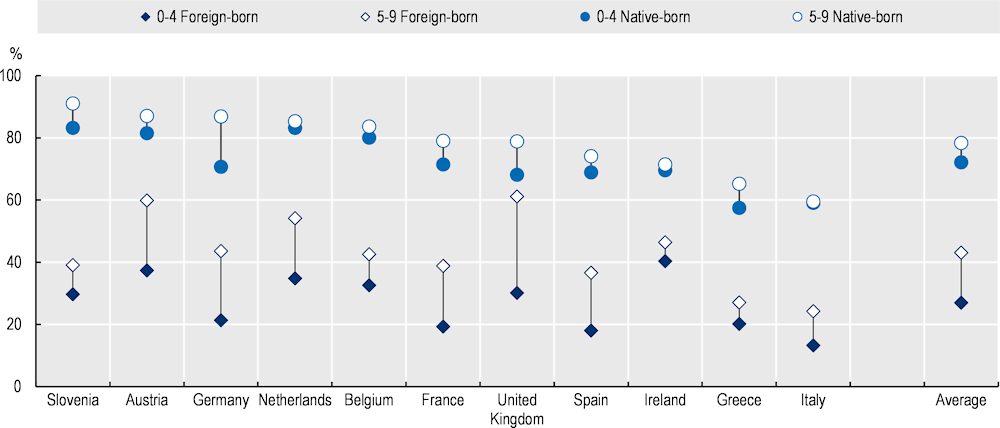

In most OECD countries, employment rates of both native‑ and foreign-born women decrease with the number of children present in the household, but the effect is larger for the latter with the birth of the first child. Figure 5.3 shows the employment rates of women with one child and two or more children, relative to women with no children. The employment gap between childless women and women with one child is five times as large for migrant women compared to their native‑born peers (on average, 16 versus 3 percentage points, respectively). When comparing childless women with mothers of two or more children, the employment gaps increase for both foreign- and native‑born women to 27 and 9 percentage points, respectively, but the effect is only slightly stronger for the native‑born given the low initial base.

Migrant mothers of one child display relatively positive employment outcomes in Luxembourg, Denmark and Sweden, which are considered family-friendly countries in general. Further, longitudinal studies have shown that the likelihood of having a first child in Sweden are positively correlated with higher income, for both men and women, showing that labour market stability increases childbearing. Conversely, in Germany, Finland8 and Italy having one child introduces significant employment gaps for migrant women. Finland is an interesting case in that it provides the longest parental leave among OECD countries and a Child Home Care Allowance (CHCA), which is granted when a child under three is looked after at home. Migrant women – and refugees in particular – have been shown to use the CHCA at higher rates, which can be partially explained by the concentration of these women at the lower end of the income distribution, meaning that their opportunity cost of providing home care is lower (OECD, 2018[32])

With more than one child, employment penalties increase the most for migrant women in Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom and France. The former two countries are interesting cases in that the employment of native‑born mothers is virtually not affected by the presence of children. Two interrelated trends, documented in the literature, can explain this: on the one hand, in Southern Europe – Italy, Spain and Greece – the negative impact of children on female activity is much smaller for highly educated women. On the other, European women are becoming mothers later in life, meaning native‑born women tend to have children once they have reached a stable position in the labour market, which gives them better opportunities to privately organise family matters and externalise childcare responsibilities (González, 2006[33]). This is particularly important in Italy and Spain, which report lower-than-average public spending on family benefits and ECEC, short supply of part-time employment and where employment instability is commonplace among women (Spain displaying the highest rate of temporary contracts among the foreign-born in 2019 across EU‑24 countries). Not surprisingly, migrant mothers, overrepresented at the bottom of the occupational spectrum and with more limited sources of family support, are less capable of balancing family and employment in these countries.

Note: Data refer to women of prime working age (25‑54). Mothers refer to women with children aged 0 to 4 (0‑5 in the United States and 0‑6 in Canada). Positive values mean higher employment rates for childless women.

Source: ABS (2019[28]), Labour Force Status of Families, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-status-families; Eurostat (2019[20]), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey; US Census Bureau (2019[23]), Current Population Survey (CPS), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html.

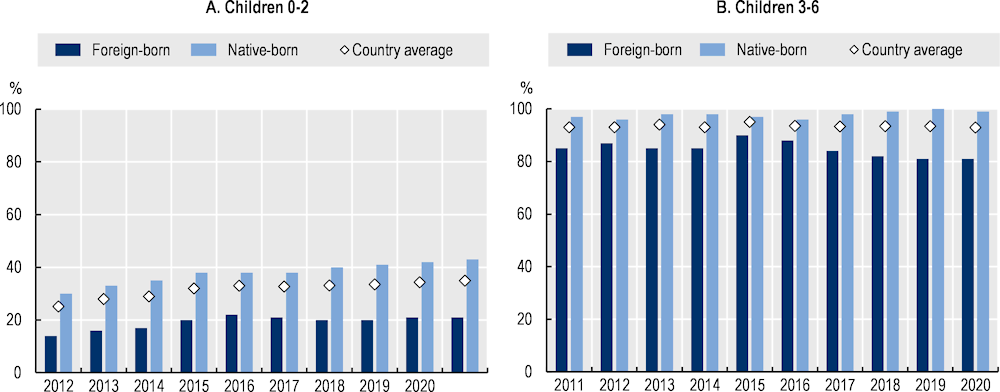

Maternal employment rates tend to increase along with the age of the youngest child. As the latter rises to five at least, employment rates increase for both native‑ and foreign-born mothers. This is not surprising as most OECD countries provide free access to ECEC to all children for at least the year before entering primary school and enrolment rates for children aged 3 to 5 average 83%, compared to 27% for children under three (OECD, 2022[34]). In addition, as seen in the previous chapter, migrant women who arrive as adults tend to display elevated fertility after arrival, which may affect insertion into the labour market. In these cases, the duration of stay in the country is also associated with higher ages among children.

When the age of children rises from 0‑4 to 5‑9 and 10‑14, the employment rates of migrant mothers increase, on average, more significantly than for their native‑born peers (partially, because the employment rate of the native‑born is already high). There is, however, significant variation across countries (Figure 5.4). As the youngest child turns at least five, the largest employment gains for both native‑ and foreign-born mothers are observed in countries of Central and Eastern Europe – Estonia, Hungary and the Czech Republic –, Finland and Germany. These countries have in common some of the longest paid parental and home care leave available to mothers,9 suggesting that both native‑ and foreign-born mothers respond to policies that incentivise childcare at home. Employment rates continue to rise for foreign-born mothers when the youngest child is at least ten in countries of Central and Eastern Europe – Estonia, Hungary, Slovenia and the Czech Republic – and Canada (+19 percentage points compared to children aged 5 to 9).

Note: Data cover women aged 25‑54. Mothers are defined as women with at least one child aged 0‑4, 5‑9 (6‑12 and 6‑13 for Canada and the United States, respectively) or 10‑14 (13‑17 and 14‑17 for Canada and the United States, respectively).

Source: ABS (2019[28]), Labour Force Status of Families, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-status-families; Statistics Canada (2019[21]) a, Labour Force Survey (LFS), https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/type/data; Eurostat (2019[20]), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey; US Census Bureau (2019[23]), Current Population Survey (CPS), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html.

Across all age groups, the largest migrant-native gaps are observed in Belgium and France. The employment rates among migrant mothers of elder children (aged 10 to 14) in those countries average 50 and 52%, respectively, and rank among the lowest, along with the countries of Southern Europe (Greece, Italy and Spain with employment rates of 42, 48 and 56%, respectively).

An alternative way to show employment evolution is through pseudo-cohorts that allow observing stable groups of individuals, rather than individuals over time (Figure 5.5). Data show that the employment of native‑born mothers, already relatively high when children are below 4 years old, increases little as children grow up (ages 5 to 9). Conversely, the employment situation of migrant mothers, whose initial base is substantially lower across all countries, improves more significantly over time.

Note: The chart follows a synthetic cohort of mothers with children 0‑4 in 2015 and 5‑9 in 2020. Data cover women aged 25‑40 in 2015 and aged 30‑44 in 2020. A cohort groups individuals with the same attributes. If these attributes do not vary over time, changes in the behaviour of cohort members can be assessed by the difference in the cohort between periods.

Source: Eurostat (2019[20]), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey.

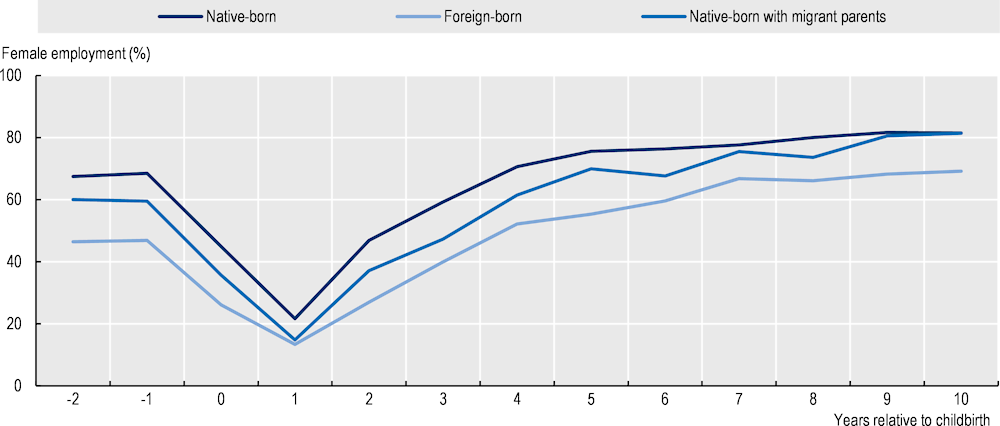

Using longitudinal data available for Germany, Figure 5.6 shows that native‑born and migrant mothers reduce their labour force participation following childbirth and experience a similar recovery as children age. After ten years, the employment gap between them is even lower than the observed one before childbirth. Significantly, intergenerational disadvantages persist with native‑born women of migrant parentage displaying lower employment rates prior to and following childbirth, compared to native‑born women with no migrant parentage.

Note: Sample is restricted to women aged 16‑50. Native‑born refers to German-born women with German-born parents. Foreign-born refers to women born in a country other than Germany and children of migrants refer to native‑born women who have at least one foreign-born parent. Employment includes full- and part-time employment, apprenticeship/education, minimal/irregular employment and workshop for disabled.

Source: Calculation by Pia Schilling based on DIW Berlin (2022[35]), German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), https://www.diw.de/en/diw_01.c.678568.en/research_data_center_soep.html.

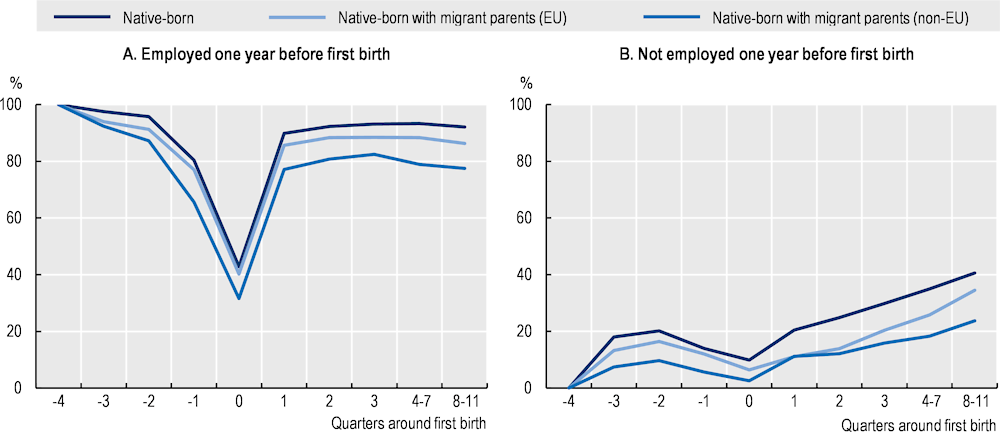

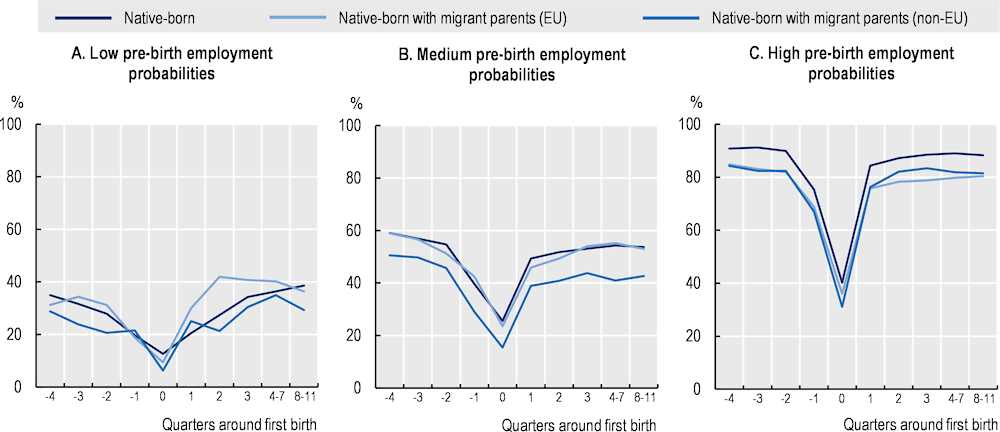

In understanding the magnitude of “motherhood penalties” employment trajectories before childbirth emerge as a key explaining factor. Figure 5.7 shows the proportion of women who were employed in each quarter from one year before until three years after the birth of their first child in Belgium,10 distinguishing women who were employed (Panel A) and women who were not employed (Panel B) one year before the birth of their first child. In the former, the proportion of employed women decreases in the quarters preceding the first birth, drops to low values in the quarter of the birth (maternity leave) and recovers as the child becomes older, but typically remains lower than one year before motherhood. There are strong differences between origin groups: the proportion of employed women decreases more strongly after family formation among native‑born women of migrant parents – particularly of non-European origin – than among women without a migrant parentage. For women who were not employed one year before parenthood, Panel B shows that the proportion of employed women increases for all origin groups, but less so among native‑born women of migrant parents – especially of non-European origin. The results seem to suggest that the birth of a first child has a stronger impact on the labour market participation of women with migrant origin than is the case among women without it, with the largest difference emerging for women of non-European origin.

Note: Proportions of women employed were estimated separately for women who were employed and women who were not employed one year before the birth of their first child.

Source: Belgian Administrative Socio-demographic Panel based on Social Security registers, 1999‑2010, calculations by Maes, J., J. Wood and K. Neels (2021[15]), “Path dependencies in employment trajectories around motherhood: Comparing native versus second-generation migrant women in Belgium”, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00801-1.

Alternatively, the pattern may reflect the lower employment stability that is typical of women with migrant parentage in the Belgian labour market, which implies that they are more likely than their native‑born peers to drop out of employment and less likely to re‑enter employment regardless of family formation. Figure 5.8 distinguishes between women in terms of their pre‑birth employment probabilities – their probability of being employed given current age and socio-demographic profile estimated among all women who do not (yet) have children11 – which offers a more robust indicator of women’s pre‑birth labour market attachment than observed employment positions at an arbitrary point in time. The proportion of employed native‑born women with migrant parents – particularly of non-European origin – is already lower before the birth of their first child compared to native‑born women with similar pre‑birth employment probabilities. As the proportion of employed women largely follows the same patterns around the transition to parenthood among native‑born women with and without migrant parentage, the impact of parenthood on employment seems similar across groups. In sum, differences between native‑born women with native‑born parents and native‑born women with migrant parents in their employment trajectories around the transition to parenthood can largely be traced back to women’s differential pre‑birth labour market attachment.

Note: Among women with low pre‑birth employment probabilities, native‑born women of EU-born parents are excluded from the analysis due to small sample size. Shares of women employed were estimated separately for women with low, medium and high employment probabilities one year before the birth of their first child. Among native‑born-women (n=6 890), 88% were employed before the birth of the first child; among those with migrant parents from the EU (n=972) and those with migrant parents outside the EU (n=703), 79% and 61% were employed, respectively.

Source: Belgian Administrative Socio-demographic Panel based on Social Security registers, 1999‑2010, calculations by Maes, J., J. Wood and K. Neels (2021[15]), “Path dependencies in employment trajectories around motherhood: Comparing native versus second-generation migrant women in Belgium”, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00801-1.

Belgium not only exhibits the largest migrant-native employment gap among mothers, but one of the largest employment gaps overall, and the two trends are closely linked. Research shows that labour market inequalities shape childbearing decisions and employment transitions for migrant women leading to cumulative disadvantages over time. While Belgium-born women perceive a stable foothold in the labour market as a precondition to childbearing and consequently postpone the transition until this condition is fulfilled, migrant women – especially from non-EU countries – are more likely to have their first child in response to unemployment or inactivity. Once children are present, labour market inequalities result in strong migrant-native gaps in the uptake of family policies such as parental leave and formal childcare, which would potentially raise their labour force participation.

On the one hand, difficult access to stable employment for migrants severely limits their access to parental leave which is strongly conditioned on labour force participation. On the other hand, formal childcare is more accessible to parents with stable employment amplifying the migrant-native gap in the uptake of these services. In turn, migrant families are more likely to resort to alternative work-family strategies that will likely reinforce gender roles within the household.

Source: Maes, J., J. Wood and K. Neels (2021[15]), “Path dependencies in employment trajectories around motherhood: Comparing native versus second-generation migrant women in Belgium”, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00801-1; Kil, T. et al. (2017[14]), “Employment after parenthood: Women of Migrant Origin and Natives Compared”, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-017-9431-7.

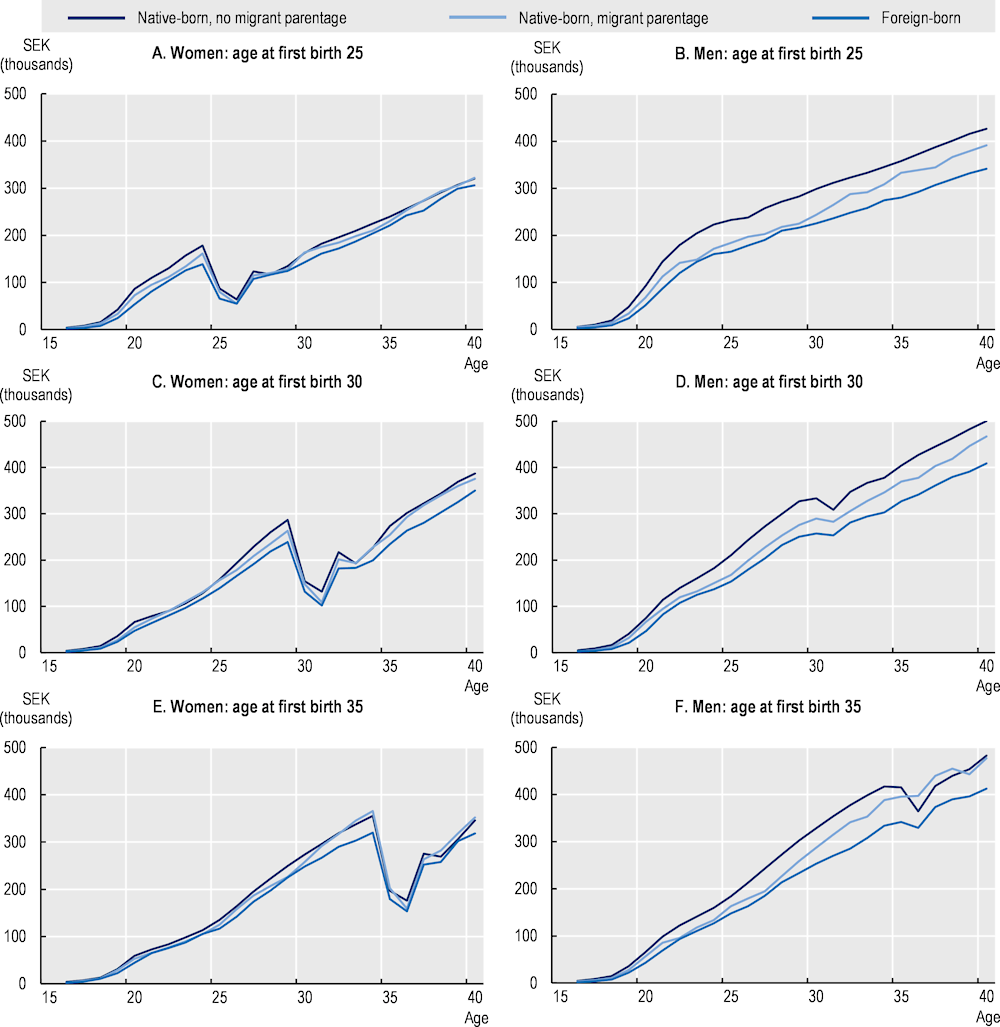

The motherhood penalty not only implies lower employment rates around childbirth and thereafter, but also lower earning profiles. Figure 5.9 displays mean earnings until age 40 in Sweden (in SEK 2020 prices) of both men and women according to the age at which they had their first child (ages 25, 30, 35 or none for the childless). Each figure displays the profile for Swedish-born of native‑born parents; Swedish-born of two foreign-born parents and foreign-born who arrived in Sweden before age 16. Each profile includes both individuals who either had or did not have more children after that first birth.

The earning profiles of women who had their first child at the same age (or who remained childless by age 40) are remarkably similar regardless of their migration origin. Differences, however, are substantial depending on the age at first childbirth: those who became mothers at age 25 portray the lowest earnings. This is not surprising as the charts pool women with various educational levels and those with lower attainment (and lower earnings potential) are bound to be overrepresented among young mothers.

The similarity of the paths indicates that, for mothers, the age at birth is more important in the lifetime earnings than other factors. In the case of men, figures show much higher earnings levels than those of women and somewhat larger differences by migrant origin. Native‑born men who become fathers in the late thirties also display a small dip in earnings around one year after birth which is likely due to the parental leave period.

Note: The figure only displays earnings and does not include allowances. Native‑born with no migrant parentage refers to Swedish-born with two Swedish-born parents. Native‑born with migrant parentage refers to Swedish-born with two foreign-born parents. Foreign-born refers to individuals who arrived in Sweden before age 16.

Source: Calculations by Stockholm University Demography Unit (SUDA), Stockholm University based on Swedish register data.

Migrant mothers can also be agents of change. Migration might propel female employment, as part of a family investment strategy to ensure financial security, particularly in the first years of arrival. Previous research emphasised the role of women as “tied migrants”; that is, they join the labour market mostly as a response to family income shocks and remain marginally attached to support their partner’s investment in local skills (Adsera and Ferrer, 2014[36]). The family investment theory, however, has been contested as recent behaviour of migrant women in the labour market more closely resembles that of their native‑born peers than often assumed.12 Whether labour market attachment after arrival is driven by economic considerations or by a reversal of traditional gender roles, migrant women’s decision to work can drive attitudinal changes and redefine gender dynamics within families, with implications for later generations.

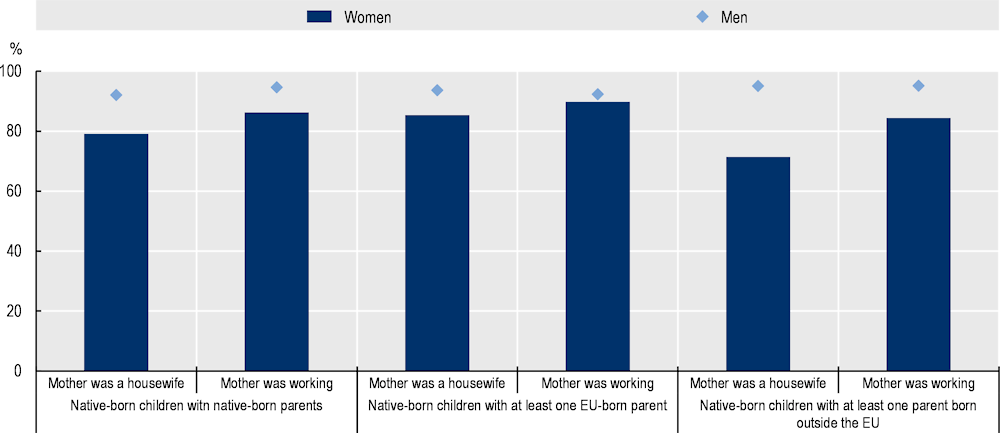

Migrant mothers’ labour market participation seems to have an important impact on the employment outcomes of their children, more so than for the latter’s peers with native‑born parents. While this is observed for both genders, the association is particularly strong for women whose parents came from non-EU countries. Figure 5.10 shows employment rates of native‑born individuals with different migration origin (children of native‑, non-EU and EU-born parents). These individuals were asked what the employment status of their mother was when they were 14 years old (i.e. the mother was either fulfilling domestic tasks or care responsibilities, or was employed). It can be observed that while the male employment rate remains relatively stable regardless of their mother’s employment status, for women, having a working mother translates into higher employment rates. For women with parents born outside the EU, in particular, having a working mother is associated with an increase of 13 percentage points in the employment rate. In Germany, among women with at least one migrant parent, having a working mother is associated with an increase of 18 percentage points.

Note: Data cover population aged 25‑54. Only financially non-vulnerable households are considered.

Source: Eurostat (2019[37]), EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-statistics-on-income-and-living-conditions.

Any analysis of maternal employment among migrant mothers must consider the origin, migration channel, household and skill composition, employment trajectories before childbirth and age at migration, which is closely related to age at family formation (Vidal-Coso, 2018[38]).

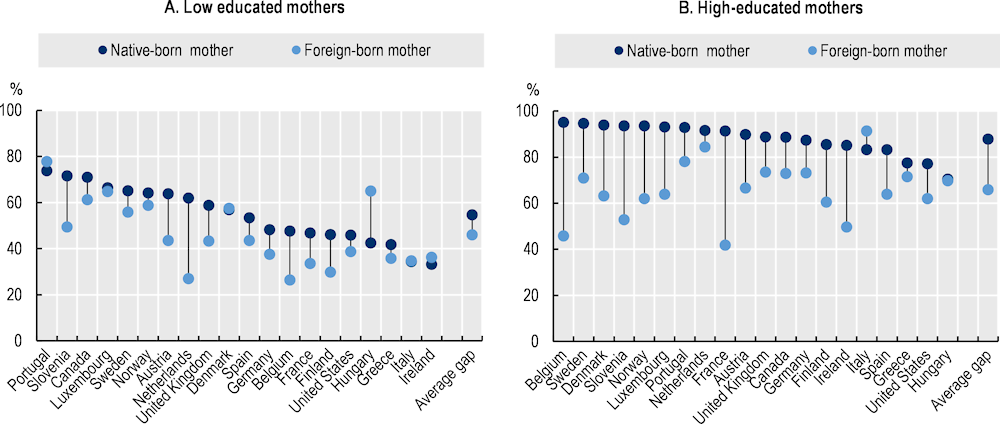

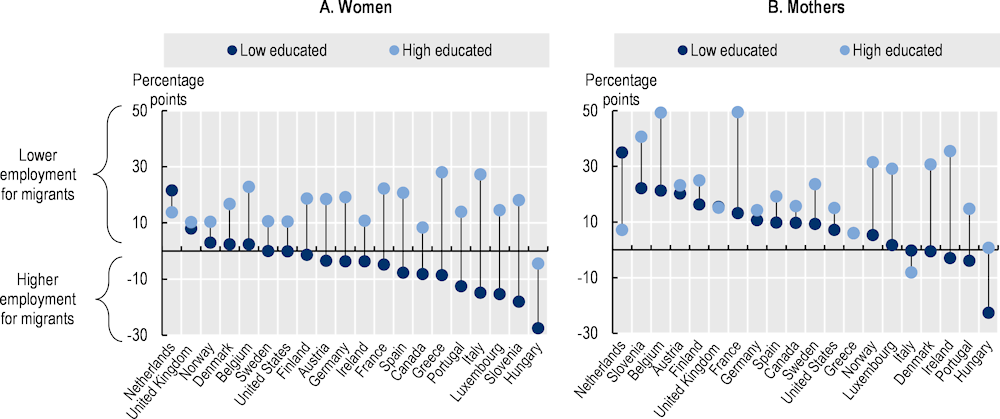

Women’s educational attainment is negatively associated with motherhood gaps in the labour market, which may be the result of higher opportunity costs of dropping out of the labour market. Higher education has also been associated with more egalitarian gender role attitudes (Steiber, Bergammer and Haas, 2016[39]). This is evident in Figure 5.11, which shows that highly educated native‑ and foreign-born mothers display significantly higher employment rates than their low-educated counterparts (+35 percentage points among the native‑born and +25 percentage points among migrant mothers).

Note: Mothers are defined as women with at least one child aged 0‑14 (0‑17 in Canada and the United States). Data cover women aged 15‑64.

Source: Eurostat (2019[20]), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey; Statistics Canada (2019[21]), Labour Force Survey (LFS), https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/type/data; US Census Bureau (2019[23]), Current Population Survey (CPS), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html.

However, migrant mothers have lower occupational returns on education compared to their native‑born peers, meaning that their employment rates do not increase as much with a higher education. This is consistent with overall employment trends among migrants. In general, low-educated migrants have either comparable or higher employment rates than their native‑born peers across OECD countries. Conversely, highly educated migrants, in virtually all OECD countries, display lower employment rates, especially if they hold foreign diplomas. Panel A of Figure 5.12 shows that indeed in almost two‑thirds of the OECD countries, low-educated migrant women display higher employment rates than their native‑born peers.

Upon childbearing, however, the comparative advantage of low-educated migrant women reverses: in eight out of ten countries, migrant mothers with only an elementary education display lower employment rates than their native‑born peers (Panel B, Figure 5.12). The employment gap is as high as 35 percentage points in the Netherlands. This is likely related to their occupation segregation, as will be explored further below: low-quality jobs, where migrant mothers with a lower education are overrepresented, increase the likelihood of labour market exits upon childbearing (Piasna and Plagnol, 2018[40]).

Employment gaps also increase for highly educated migrant women upon childbearing, but they increase at lower rates than among the low educated. Again, high-educated mothers may be able to self-select into high-quality jobs in terms of job security, career progression and working time, allowing them to better reconcile childcare responsibilities and paid employment. Further, outsourcing care responsibilities is more common among highly educated women so even in the absence of public subsidised childcare or family networks, highly educated migrant mothers are more able to outsource care.

Note: Data cover women aged 15‑64. Mothers are defined as women with at least one child aged 0‑14 (0‑17 in the US and Canada). Positive values mean higher employment rates for native‑born women/mothers.

Source: Eurostat (2019[20]), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey; Statistics Canada (2019[21]), Labour Force Survey (LFS), https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/type/data; US Census Bureau (2019[23]), Current Population Survey (CPS), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html.

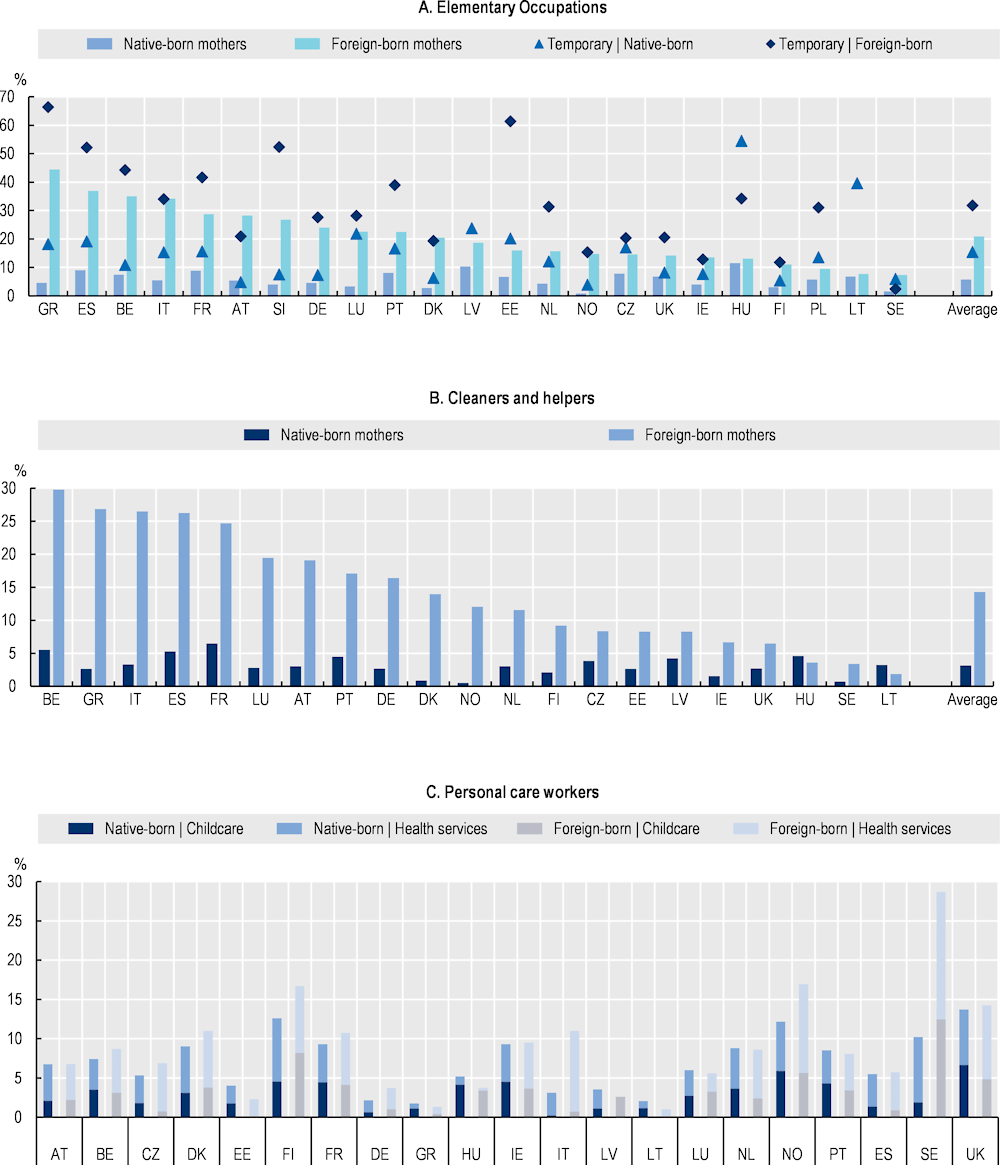

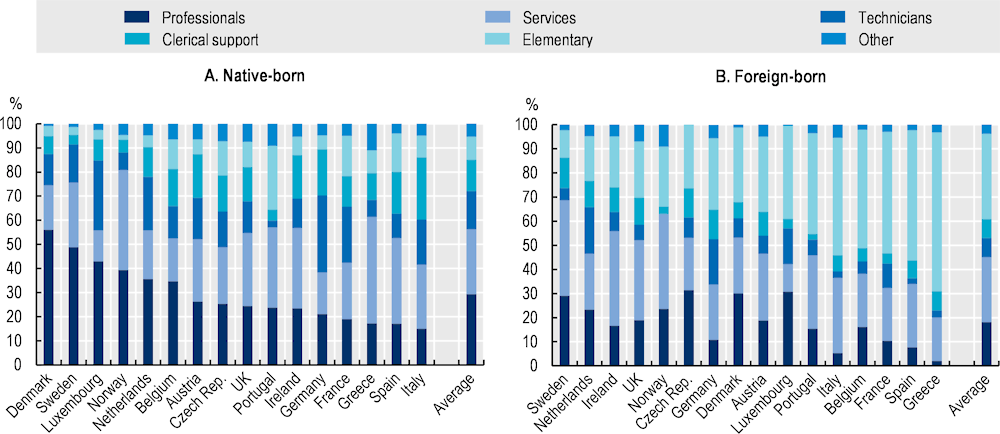

Overall, women experience greater concentration in a more limited number of occupations than men and this is also true for migrants. There is also evidence that the occupational gap between migrants and the native‑born is driven by factors other than age and education and that the unexplained occupational segregation is higher for migrant women than men (Frattini and Solome, 2022[41]; Palencia‐Esteban, 2022[42]).

“Female occupations” often include those that provide relatively better working conditions rather than better pay, like public sector jobs, which tend to have generous benefits like flexible hours and long parental leaves. In European OECD countries, however, migrant mothers (of children less than 14) are less likely to be employed in the public sector (‑12 percentage points). The gap can be as high as 40 percentage points in Luxembourg and exceeds 20 percentage points in Southern Europe (Italy, Spain and Greece) and the Netherlands.

In European OECD countries, one in five migrant mothers are employed in elementary occupations,13 among which the most common is cleaners/helpers (on average 17%). This is particularly evident in Belgium and Southern Europe, where the share of this occupation in employment exceeds 25%. Not only are migrant mothers overrepresented in elementary occupations, but they are also twice as likely to hold temporary contracts in these occupations compared to their native‑born peers (32% versus 15%, respectively).

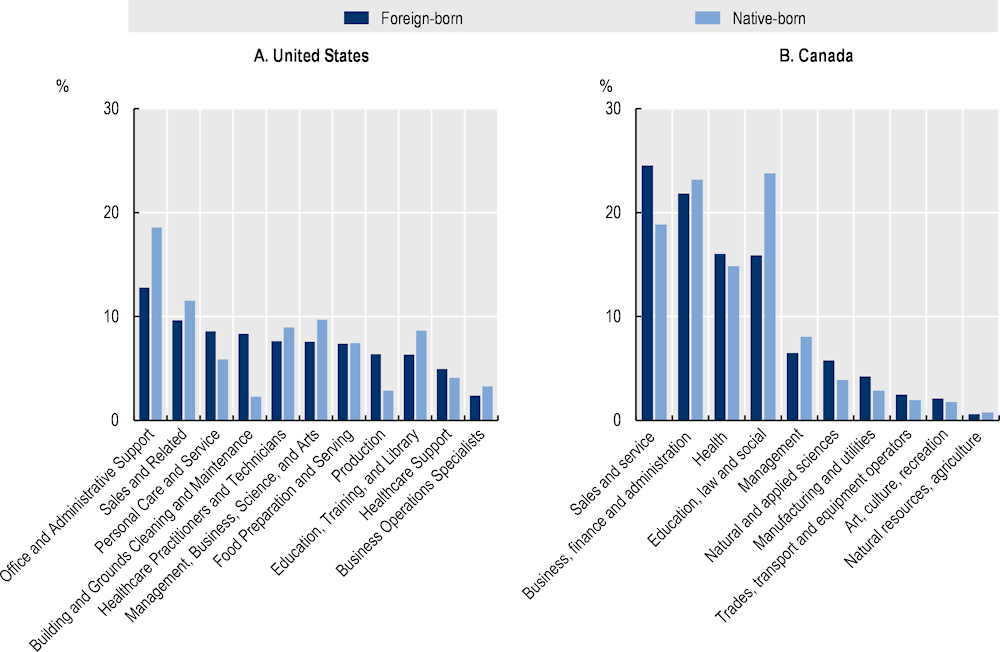

While this occupational concentration does not differ for migrant women with no children, the implications for mothers are much more significant. Employment conditions in these types of occupations are detrimental in terms of labour market attachment after childbirth. Cleaners and helpers, for example, are a particularly low-paid job, even among the generally low pay elementary occupations and are generally excluded from contributory social insurance schemes, which might prevent migrant mothers from accessing parental leave.14 Low-paying occupations are also associated with lower opportunity costs of dropping out of the labour market upon childbearing. Further, casual or temporary contracts, which are twice as common among migrant mothers, may come to an end while a mother is on maternity leave, thus contributing to the postponement of motherhood or exit from employment (Piasna and Plagnol, 2018[40]) (Figure 5.13). In the United States migrant mothers are slightly overrepresented in cleaning, personal care and production occupations compared to their native‑born peers. In Canada, the same is true in sales and services occupations (Figure 5.14).

The second most common occupation among migrant mothers in European OECD countries is as personal care workers (both in health services and as childcare workers/teachers’ aides). Their shares in employment in these occupations are highest in the Nordic countries and the native‑migrant gaps are smaller, averaging only 2 percentage points. Importantly, the availability and affordability of childcare and care services in health settings in these countries has counteracted the development of an informal market, which is distinct from several European countries. The implication is that migrants who become child and healthcare workers in Sweden, Norway, Finland or Denmark are generally formally employed, which allows them to benefit from better work conditions and entitlement to insurance benefits (Puppa, 2012[43]). This contrasts with the case of Italy where the private care market is characterised by low wages, hard working conditions, high insecurity and limited chances of job mobility (van Hooren, 2014[44]).

Note: Mothers are defined as women with at least one child aged 0‑14 (0‑17 in Canada and the United States). Data cover women aged 15‑64.

In Panel A, temporary refers to temporary contracts as a share of total contracts in elementary occupations. Elementary occupations comprise those in ISCO one‑digit category 900; cleaners and helpers correspond to ISCO three‑digit categories 911. Personal care workers comprise those in ISCO three‑digit categories 531 (childcare workers and teachers’ aides) and 532 (personal care workers in health services).

Source: Eurostat (2019[20]), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey.

There are two important implications of this occupational distribution: first, these occupations are associated with poor working conditions for migrant women in most countries given the prevalence of informal and private care markets. Second, the employment of migrant mothers (and migrant women, more generally) in household and care services has proven to increase the availability of these services and allow native‑born mothers to return to work after childbirth. This is especially true in contexts of high-income inequality or where social and family policies are less developed. Estimates by Farré, González and Ortega (2011[45]) in Italy, for example, show that immigration can account for one‑third of the increase in the employment rate of college‑educated women by providing child and elderly care (before 2008). In the United States, Furtado and Hock (2010[46]) find that a reduction in the cost of household services – led by low-educated migrants – allow tertiary-educated native‑born women to reconcile childbearing and paid work.

Note: Mothers are defined as women with at least one child aged 0‑17. Data cover women aged 15‑64.

Source: Statistics Canada (2019[21]), Labour Force Survey (LFS), https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/type/data; US Census Bureau (2019[23]), Current Population Survey (CPS), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html.

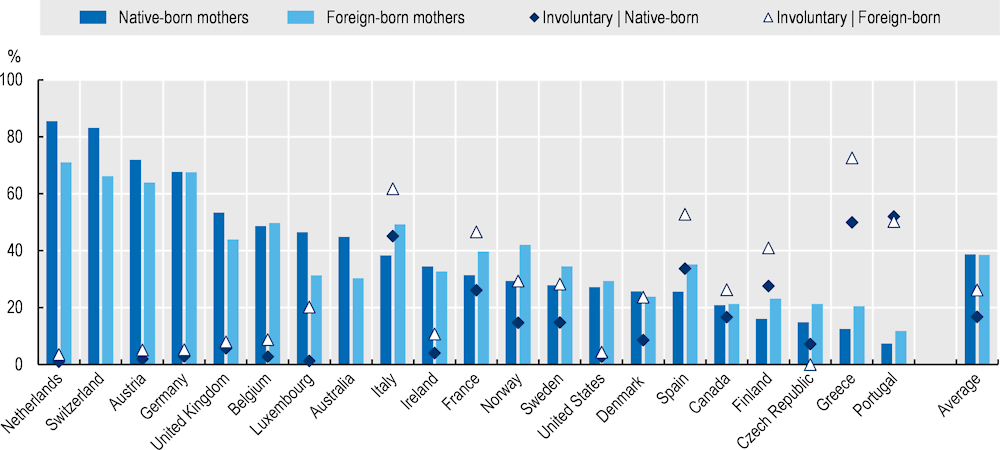

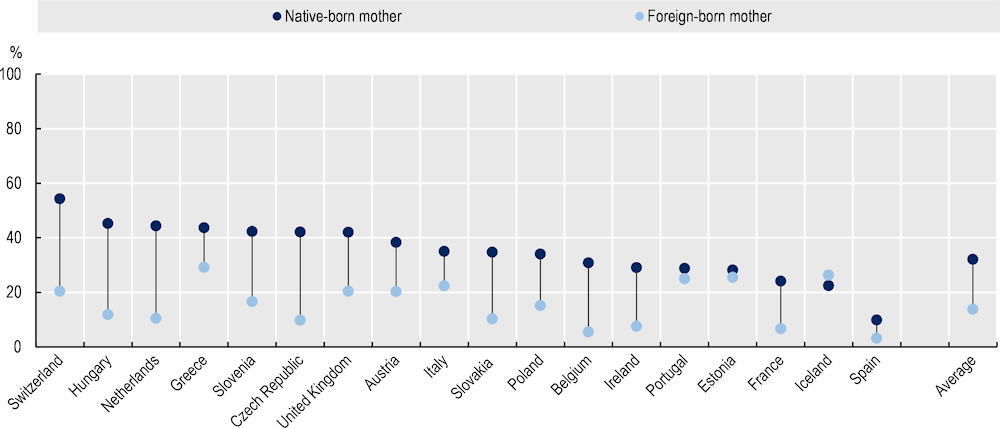

In many OECD countries, mothers are less likely to work long hours and they frequently use part-time employment as a means of combining work with family responsibilities. Part-time employment, for instance, has been associated with higher fertility in Europe during the mid‑90s (Adsera, 2011[47]). However, part-time employment is highly gendered as it is usually women who take up part-time employment, especially after childbearing. As such, the effects of this type of arrangement on gender equality are disputed. On the one hand, it may allow women to combine family responsibilities and paid work instead of dropping entirely out of the labour force. But it can also marginalise them into low-end market niches (OECD, 2017[48]). Part-time work is often associated with slower career progression, lower earnings and earnings-related pensions, and overall, lower job quality (OECD, 2019[49]).

The quality of part-time employment can be affected by the skill set of workers in part-time jobs – as they are often related to lower-educated and -skilled positions – and whether it is “involuntary” or “voluntary”.15 A key issue for the labour market integration and career progression of migrant mothers (and migrant parents overall) is that they are unwillingly stuck in part-time work. In the EU, foreign-born mothers are more likely than their native‑born peers to be unable to find a full-time job, even if they report wanting to work more. Across OECD countries, 25% of foreign-born mothers with at least one child aged 0‑14 find themselves in this situation compared to 15% of their native‑born peers (Figure 5.15). Involuntary part-time employment may result in lower wages, lower training opportunities, poorer career prospects for women and lower social security contributions which translate in higher vulnerability when facing unemployment, health problems and financing retirement (ILO, 2016[50]).

Note: Mothers are defined as women with at least one child aged 0‑14 (0‑17 in Canada and the United States). Data cover women aged 15‑64 (women aged 25‑54 in Switzerland).

Source: Eurostat (2019[20]), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey; FSO (2021[30]), Swiss Labour Force Survey (SLFS), https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/work-income/surveys/slfs.html; Statistics Canada (2019[21]), Labour Force Survey (LFS), https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/type/data; US Census Bureau (2019[20]), Current Population Survey (CPS), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html.

Part-time employment is also more precarious for migrant mothers since it is often associated with temporary contracts: in 2019, one in four migrant mothers working part-time in European OECD countries had a temporary contract, compared to one in seven native‑born mothers. This is also related to the occupational segregation of migrant women: for them, part-time employment is mostly concentrated in elementary occupations (Figure 5.16), whereas for their native‑born peers, it mostly takes place within professional occupations. Because the cost of adjusting to part-time work is absorbed by the firms, this type of arrangement is only possible when the employment status is protected (Guirola and Sánchez-Domínguez, 2022[51]). In this regard, low-skilled workers display less bargaining power than their higher-skilled peers (Adema, Clarke and Thévenon, 2020[10]). Not surprisingly, professionals and managers16 are much more likely to access secure and protected part-time employment. Migrant workers, overrepresented in lower-skilled sectors, are less likely to benefit from the latter.

Note: “Other occupations” include armed occupations, “Managers”, “Skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers”, “Craft and related trades workers” and “Plant and machine operators and assemblers.”

Source: Eurostat (2019[20]), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey.

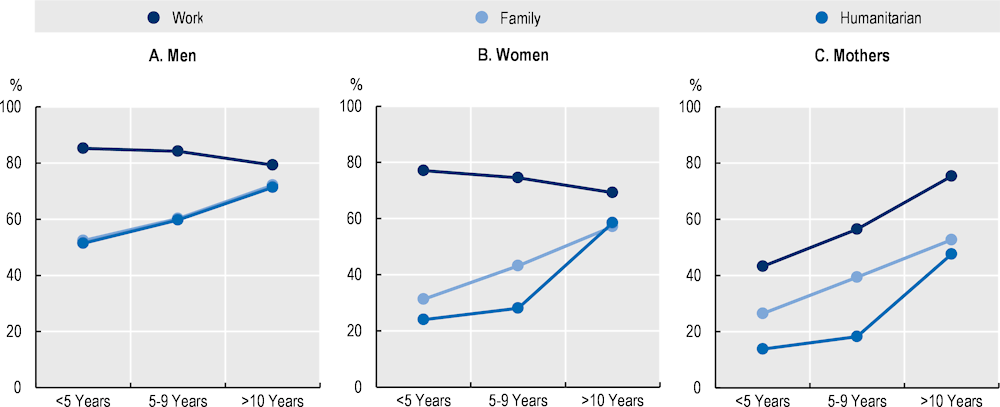

Migrant women are highly heterogeneous regarding their reasons for migration and self-select into different migration channels. Migration category, in turn, is highly predictive of women’s family and employment trajectories after arrival (Samper Mejía, 2022[52]). Most women arrive in the OECD countries as family migrants (see previous chapter), which comprise very different types of profiles: persons marrying a resident national or foreigner and joining him or her in the host country (that is, family formation), families joining a migrant who had migrated earlier (that is, family reunification) and family members accompanying a newly admitted economic migrant, student or refugee.

Research shows that, in general, the employment outcomes of women who arrive as family migrants tend to be less favourable than those of labour migrants. Their employment rates generally improve over time but often take many years to reach the employment rates observed for other migrant categories or for native‑born individuals.

Lower employment outcomes among family migrants may be driven by several factors:

Family formation before labour market insertion: women who arrive for family reasons may display elevated fertility patterns compared to their native‑born peers, particularly after arrival, as the migration event and family formation are often temporally interrelated events (see previous chapter on fertility). Their employment and fertility trajectories might also differ from those of women who migrate for employment reasons, who may need more time to adjust and decide whether to have children (and even find a partner) in the host country (Mussino and Strozza, 2012[53]).

The effect of a spouse: if the principal migrant is a labour migrant, family migrants might also be less compelled to seek their income from employment compared with other migrants, who cannot rely on a steady spousal income. The vast majority of married migrants live with their spouse in host countries. The share of migrants whose spouse is absent in the host country remains below 20% in almost all OECD countries, and it falls with duration of stay (OECD, 2019[54]).

Family migrants might choose not to participate in the labour market of the host country but rather raise children or care for other family members. Survey results indicate that, among female family migrants in Australia and Germany, for example, caring for children is the main reason not to work. Such dynamics within couples and households are likely an important contributor to the slow labour market integration of family migrants. When planning to migrate to a particular country, couples likely divide such roles such that the person who has higher chances to be admitted as a labour migrant, international student, or refugee assumes the role of principal migrant (OECD, 2017[55]).

Administrative or legal obstacles to access the labour market: across OECD countries, there has been a general trend to facilitate labour market access to family migrants but some – albeit few – categories, mostly with temporary status, still find themselves locked out of the labour market, at least initially. Frequently these are spouses of temporary labour migrants with no prospects of remaining in the country. However, in a few countries, restrictions also apply to family migrants who are likely to remain17 (OECD, 2017[56]).

Figure 5.17 shows that women who migrate for family or humanitarian reasons to the EU display similar employment trajectories, regardless of whether they have children or not: their employment rates are low within the first five year of arrival but improve significantly over time. Their employment rates, however, never attain the same levels as those displayed by women who emigrate for employment. When considering childbearing, employment rates fall for all categories of female migrants, including for those who migrate for employment, and the gap is particularly evident during the first five years of arrival.

In Australia, the employment rate of female migrants with a skilled stream visa was 76% in 2021, 18 percentage points higher than the employment rate registered for female family migrants (57%). The employment rate of female humanitarian migrants was substantially lower at 33%.18

Note: Data cover the OECD countries of the European Union and men and women aged 15‑64. Chart shows employment rates with no controls and pooling countries.

Source: Eurostat (2021[57]), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey.

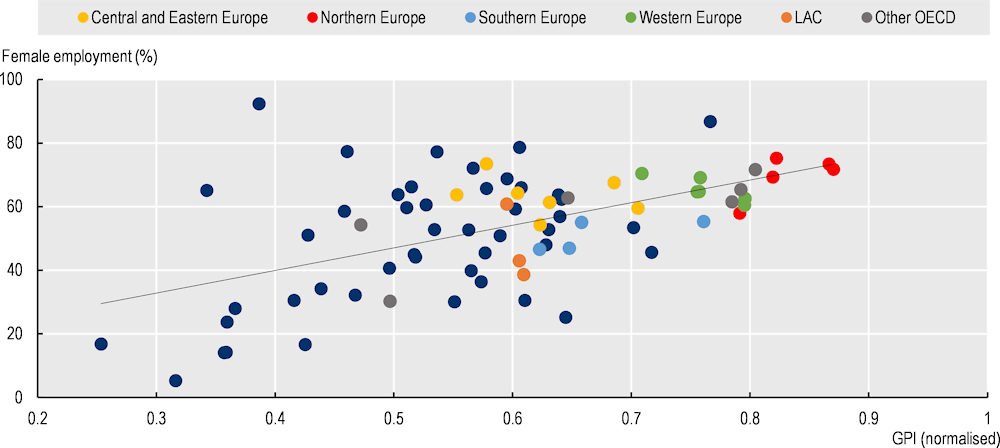

Fertility choices and the participation of women in the labour market not only reflect institutional arrangements in a given country but prevailing social and gender norms as well. Social norms are rules of action shared by people in a given society or group and define what is considered acceptable behaviour for members of that group (Cislaghi and Heise, 2020[58]). Gender norms can be considered as the beliefs commonly held about the role of women in society (Fernandez and Fogli, 2005[59]).

The unequal effects of children on their parents’ careers, the persistence of these effects across generations, as well as the fact that, on average, women are more educated than men, make these norms an important element to consider in the explanation of child penalties (Kleven, Landais and Sogaard, 2019[7]). Previous research suggests that family policies are shaped by their cultural context. Policies do not shape employment choices in a cultural void but, instead, interact with societal attitudes regarding the role of women. For example, very long parental leaves may reflect the notion that mothers should provide for young children at home. In this regard, gender norms may mediate the effect of family policies: parental leave policies and public childcare, for instance, are associated with higher earnings for mothers when cultural support for maternal employment is high (Budig, Misra and Boeckmann, 2012[8]).

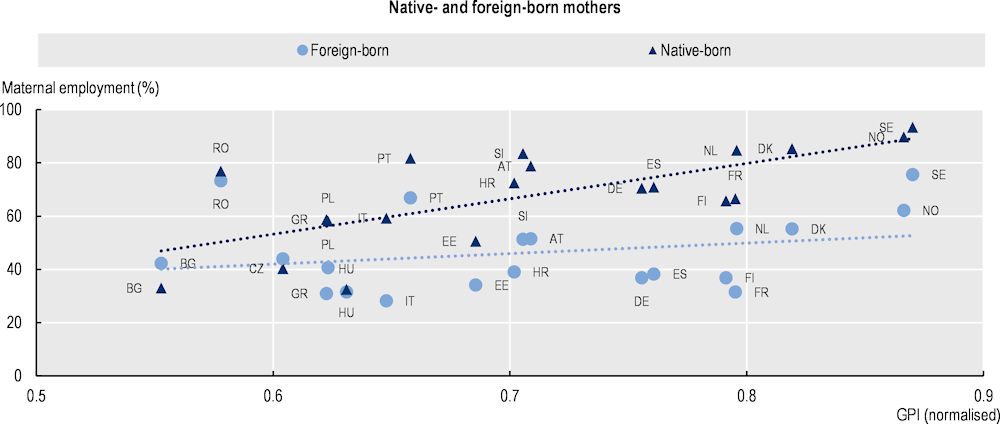

Figure 5.18 shows the correlation between progressive gender norms and female employment in selected OECD countries. Following Kleven (2022[16]), a Gender Progressivity Index (GPI) is created using data from the joint European and World Value Survey (2017‑21). The responses to five questions on the role of women in society are standardised. The questions are the following: Do you agree with the following statement: a) when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women; b) there is a duty towards a society to have children; c) when a mother works for pay, the children suffer; d) on the whole, men make better business executives than women do; e) university is more important for a boy than for a girl. The standardised response is then indexed such that higher values correspond to stronger gender progressivity. The chart shows that there is a positive correlation between progressive gender values and female employment and that there is high cross-country variation regarding gender norms. The Nordic OECD countries, followed by those of Western Europe, display the highest levels of female employment and gender progressivity. There is also a positive relation between progressive gender values and maternal employment, as shown in Figure 5.19.

Note: Data refer to women of working age (aged 15‑64). Northern Europe includes Sweden, Iceland, Denmark, Finland, Norway; Western Europe includes Austria, Belgium, Germany, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Luxembourg, Switzerland; Central and Eastern Europe includes Hungary, the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Slovenia; Southern Europe includes Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain; LAC includes Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Costa Rica; and other OECD countries include Australia, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, the United States, Canada, Türkiye, Israel.

Source: EVS/WVS (2022[60]). European Values Study and World Values Survey: Joint EVS/WVS 2017‑22 Dataset (Joint EVS/WVS), https://doi.org/10.14281/18241.21.

Finally, it is acknowledged that gender norms are learned in childhood in a process known as socialisation and are later reinforced or contested in family and the larger societal context. This means that the prevailing culture in the origin country likely influences attitudes and preferences within migrant families at the destination. Figure 5.19 shows that, indeed, maternal employment for migrant women is less sensitive to country-level gender norms, suggesting that, for them, the influence of gender norms in their country of origin are probably more significant.

However, cross-sectional data do not allow to understand how gender norms interact with institutional and economic incentives over time, but earlier research suggests that the transmission of these norms can happen vertically – from one generation to the next – or horizontally – through social interactions with peers and colleagues. In line with the theory of vertical transmission, Fernandez and Fogli (2005[59]) find, for the United States, that the average labour force participation among children of migrants is predicted by the average participation in the origin country of their parents and that similar patterns emerge for fertility rates. Similarly, Blau, Kahn and Papps (2008[61]) show that, in the United States, female labour force participation among migrants and their children is strongly correlated with female labour force participation in the country of origin.

Note: Maternal employment rates for women aged 15‑64 with at least one child aged 0‑4.

Source: Eurostat (2021[57]), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey; EVS/WVS (2022[60]), European Values Study and World Values Survey: Joint EVS/WVS 2017‑2022 Dataset (Joint EVS/WVS), https://doi.org/10.14281/18241.21.

Boelmann, Raute and Schonberg (2021[62]) find evidence of both channels of transmission when analysing differences in the labour force participation of women who grew up in East and West Germany, respectively. These two settings differed in female labour market participation, fertility patterns, and gender norms but institutions and economic conditions converged after reunification. The authors find that the child penalty in terms of female labour supply is smaller among East German mothers relative to their Western counterparts in similar institutional settings.

The influence of normative contexts has implications for migrant-native activity gaps. Analysing the labour market outcomes of the same origin group, children of Turkish migrants, across different destinations, Holland and de Valk (2017[13]) conclude that employment gaps between native‑born women with two native‑born parents and daughters of at least one Turkish-born parent are smaller in countries with strong normative contexts – Sweden’s institutionalised culture of gender equality – whereas countries with family policies that do not explicitly support any single‑family model – France and the Netherlands – amplify the gaps with daughters of Turkish-born parents.

Individual choices regarding maternal employment respond to individual preferences and macroeconomic conditions but are also mediated by the broader policy context. While there is a great variation in the role and approach of family policy across countries, since the early 2000s, many OECD countries have increased their support to balancing work and family life, with a focus on facilitating women’s employment and encouraging a more equal division of labour (Adema, Clarke and Thévenon, 2020[10]). To achieve these objectives, countries have relied on a combination of instruments: ECEC provision, paid parental leave, and flexible work time regulations. However, family policies may also have unintended consequences such as reinforcing gender job segregation or increasing social inequalities between different groups of parents. For instance, part-time employment is an attractive option for mothers and fathers wishing to reconcile work and family responsibilities, but it is rarely a stepping stone to full-time employment and many mothers work part-time on a long-term basis (OECD, 2019[49]). Similarly, parenting leave systems with stringent employment-related criteria may exclude recent immigrant parents who either had a child immediately after arrival or, simply, have had little time to gain relevant local experience, settle in the labour market and pay associated contributions to the insurance system.

Paid parental leave is considered employment supportive, helping women remain attached to the labour market following childbirth. The positive employment effects are strongest when the period of leave is relatively short as long leaves may lead to human capital depreciation and facilitate employers’ discrimination against women (OECD, 2016[63]).

OECD countries generally offer three types of paid and unpaid family-related leave around childbirth: maternity leave, paternity leave and parental leave (used by one or both parents), which in some countries is complemented with homecare leave of prolonged duration (Adema, Clarke and Frey, 2015[64]). Even if there is a positive correlation between generous parental leave policies and women’s labour market participation after childbearing, leave policies may create incentives for specific groups to stay out of the labour market. While research on access to and uptake of parental leave among migrant parents is limited, previous studies show lower uptake in the Netherlands, Belgium and Spain where eligibility criteria are related to labour market participation (Mussino, forthcoming[65]).

Overall, migrant parents – and recent migrants, in particular – may be excluded from parental leave systems on account of their design and, specifically, due to their employment status or occupation, income level or their residency status in a country (Duvander and Koslowski, 2023[66]). The use of parental leave is also mediated by the individuals’ own financial resources with disadvantaged parents displaying lower take‑up rates overall.19 In addition, there is evidence that migrants may lack knowledge about their parental leave rights and regulations, and this is particularly true among recent arrivals.

Most OECD countries link child and family income support with parental earnings and employment meaning that access to parental leave is often conditioned on periods of employment and/or contributory records (Daly, 2020[67]). In this sense, the use of parental leave becomes a reflection of labour market participation (Mussino and Duvander, 2016[68]). However, when pre‑birth labour market integration is low or outside formal employment, the same policy may have a negative impact, resulting in a low benefit or no benefit at all during leave and a more disadvantaged situation afterwards given the extended period outside the labour market and the lack of income (Mussino and Duvander, 2016[68]).

As seen in Chapter 4, migrants tend to display elevated fertility after arrival and have children at a younger age than the native‑born. These patterns may lead to low pre‑birth employment history, excluding parents from parental leave systems, especially if they have not formally entered the social insurance system, have not formally been employed, or been registered as unemployed at destination. The longer the qualifying period – particularly if it is meant to be uninterrupted –, the less accessible it becomes to migrant parents with unstable careers (working under temporary contracts, on a part-time basis, or as self-employed). Migrants also tend to be underrepresented in the public administration, where benefits tend to more generous in certain countries.

An alternative to employment-based criteria to access parental leave are universal benefits or tiered systems. In the former, leave rights are available to all parents residing in the country. In the latter, universal benefits are usually lower and more generous benefits are available to those meeting employment-related criteria (Duvander and Koslowski, 2023[66]) (Table 5.1). Universal benefits might promote a more gendered use of leave (claimants are predominantly mothers as low benefits provide little incentives for fathers to claim them) but they reduce ethnic disparities in accessing parental benefits.20 Tiered systems, on the other hand, might amplify social inequalities among groups of parents. In Sweden, where parents can receive an income‑related benefit for 390 days or a parental benefit at the basic level when they cannot meet the employment criteria, roughly 12% of women and 4% of men received the latter in 2018. Among them, approximately three‑fourths of recipients were migrants (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, 2019[69]).

Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, Japan, the Netherlands and Spain exclude self-employed workers from parental leave benefits. Although self-employment rates do not differ significantly between native‑ and foreign-born individuals, a non-negligeable share of migrant parents might be excluded on this account. Finally, Italy excludes domestic workers from parental leave, among which migrant women are overrepresented.

While entitlement to parental leave most often derives from employment (as opposed to nationality), some countries restrict access through residency criteria or waiting periods. Australia, for example, includes a newly arrived residents waiting period of two years, which applies to holders of permanent residence as well.

Overall, migrants may face challenges in accessing parental leave due to language barriers and lack of institutional knowledge. In Sweden, Finland and Norway, there is evidence of lack of information about parental leave rights and application procedures among native‑born parents (Ellingsæter, Hege Kitterød and Misje Østbakken, 2020[70]). Lack of information is likely to be more pronounced among their migrant peers. In Sweden, Mussino and Duvander (2016[68]) also find different patterns of parental leave use among native‑ and foreign-born mothers, suggesting lack of knowledge of parental leave regulations, especially regarding the different options for flexibility. Migrant mothers tend to exhaust their leave immediately following childbirth, whereas Swedish-born mothers exploit the flexibility of the parental leave system to a larger extent and stay connected to the labour force when taking leave.21

Two features have proven to increase uptake of leave among migrant parents: