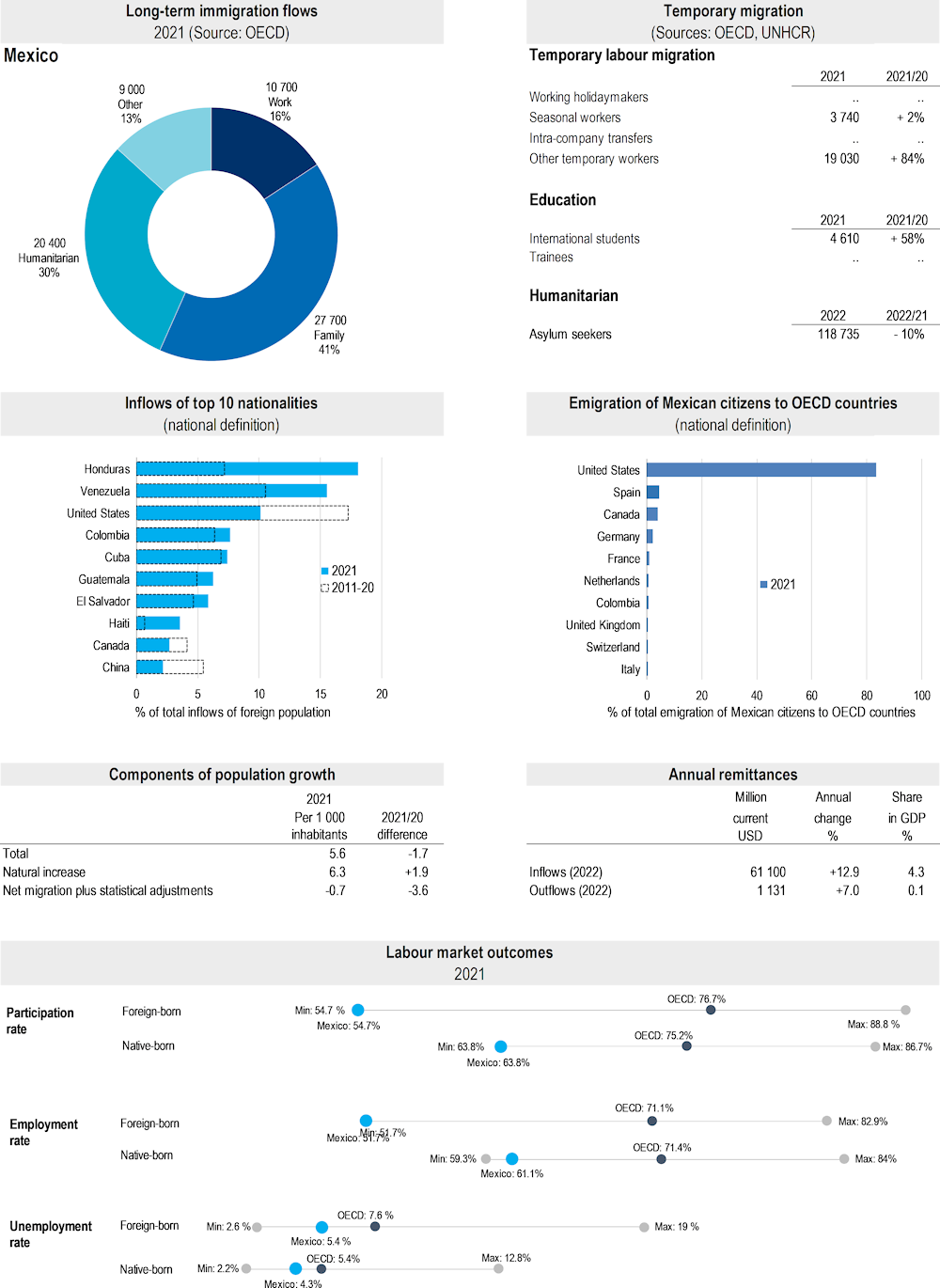

In 2021, Mexico received 68 000 new immigrants on a long-term or permanent basis (including changes of status), 16% more than in 2020. This figure comprises 15.7% labour migrants, 40.9% family members (including accompanying family) and 30.1% humanitarian migrants. Around 4 600 permits were issued to tertiary-level international students and 23 000 to temporary and seasonal labour migrants.

Honduras, Venezuela and the United States were the top three nationalities of newcomers in 2021. Among the top 15 countries of origin, Honduras registered the strongest increase (+4 400) and Venezuela the largest decrease (‑500) in flows to Mexico compared to the previous year.

In 2022, the number of first asylum applicants decreased by ‑9.7%, to reach around 119 000. The majority of applicants came from Honduras (31 100), Cuba (18 100) and Haiti (17 200). The largest increase since 2021 concerned nationals of Cuba (+9 800) and the largest decrease nationals of Haiti (‑34 700). Of the 65 000 decisions taken in 2022, 35% were positive.

Emigration of Mexican citizens to OECD countries increased by 12% in 2021, to 128 000. Approximately 83% of this group migrated to the United States, 5% to Spain and 4% to Canada.

Throughout 2022, Mexico experienced an increase in irregular migration at the southern border. Additionally, as a result of the application of Title 42, Mexico continued taking back migrants expelled by US authorities. Due to the increase of irregular transit through Mexico, Mexico imposed visa requirements for Venezuelan nationals in January 2022 and for Brazilian nationals in August 2022. After the end of Title 42, in May 2023, Mexico announced that, on humanitarian grounds, it would continue to accept 30 000 individuals per month from Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba. Although in 2022 the issuance of humanitarian documents increased by more than 47% compared to 2021, this does not necessarily implied a decrease in the irregular migrations flows. In addition, to mitigate these irregular migratory flows, Mexico is seeking co‑operation channels to facilitate regular labour migration.

Within the framework of the Migration Law, the National Institute of Migration (INM) increased scrutiny at the border, which were declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, as they did not contain elements that would allow the individualisation of the procedure.

In 2022, close to 120 000 asylum claims were filed in the country which has put the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance under significant strain. While its processing capacity has improved over the years with support from the UNHCR, and its annual budget has increased in recent years, it has not been enough due to the increased number of claims.

In March 2023, a fire at a IMN accommodation facilities in the northern city of Ciudad Juárez killed 40 migrants. Immediately after, the INM announced it would work with the Mexican Human Rights Commission to evaluate conditions at migration centres.

In April 2023, Mexico’s Supreme Court also ruled that the country’s National Guard can support the INM by guaranteeing the safety of migrant and migrant centres. Human rights groups have opposed the decision.

Regarding integration, UNHCR continues to promote and support the integration of recognised refugees through their relocation in cities with increased prospects of formal employment. As part of its Local Integration Programme, the UNHCR in collaboration with Mexican authorities helps them secure access to employment, long-term accommodation, education, and health services. In 2022 alone, approximately 13 000 refugees received relocation and integration assistance – the highest annual number to date.

The Government of Mexico has had an approach with local governments to promote and foster actions for the integration of migrants. In addition, technical assistance has been provided in collaboration with international organisations, such as the IOM, UNHCR and GIZ.

In the northern border of Mexico can be found some Migrant Integration Centres where the migrant population is provided with job offers, as well as basic health, food and educational services while they are staying in Mexico. This strategy is in charge of the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare and the Ministry of Welfare.

Further information: www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx | www.comar.gob.mx