This chapter provides an overview of the educational, employment and well-being outcomes of young people in Korea. It first outlines Korea’s economic context. It then compares the educational and employment performance of young Koreans with that of young people across OECD countries, focusing on employment, unemployment and educational attainment. The chapter also describes the size and composition of the population of young people who are not in employment, education or training as well as employment quality and skill mismatches. The chapter concludes with information on the life satisfaction and poverty rates among young people.

Investing in Youth: Korea

1. Youth employment and education in Korea

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

1.1. Introduction

Korea has been one of the ‘economic miracles’ of the post-World War II period, but its current growth prospects are much more limited. Within this environment, young people are hitting upon increasing difficulties in finding a stable footing on the labour market. They often invest a lot of time and money in qualifications and certificates and can nonetheless find themselves relegated to unstable and unsatisfactory employment.

This chapter lays out the general educational and labour market outcomes of young people in Korea. It starts out by presenting the general economic environment (Section 1.2). The chapter then outlines the labour market situation of young people, including the employment and unemployment rate, and discusses reasons for the relatively high share of youngsters who are neither working nor in formal education, followed by an analysis of job search and job quality, and a discussion of skill mismatches (Section 1.3). The final sections present youth income poverty and well-being measures (Section 1.4) and a wrap-up of the different findings (Section 1.5).

1.2. The economic context

Korea’s economic growth record over the past half century has been astounding, boosted by a successful policy mix and an expansion of the working-age population. In 1966, Korean GDP per capita was around one tenth of Japanese GDP per capita, and only slightly higher than in sub-Saharan Africa. By 2016, it had reached more than half the Japanese and fourteen times the sub-Saharan value. Large conglomerates were a driving factor behind this growth. They established themselves on the international market thanks to an export-oriented industrial policy backed by sound fiscal and monetary policies. The conglomerates were able to hire the increasingly skilled workers needed for complex production processes because the working-age population was growing and the government invested heavily in high-quality education (Jones, 2013[1]).

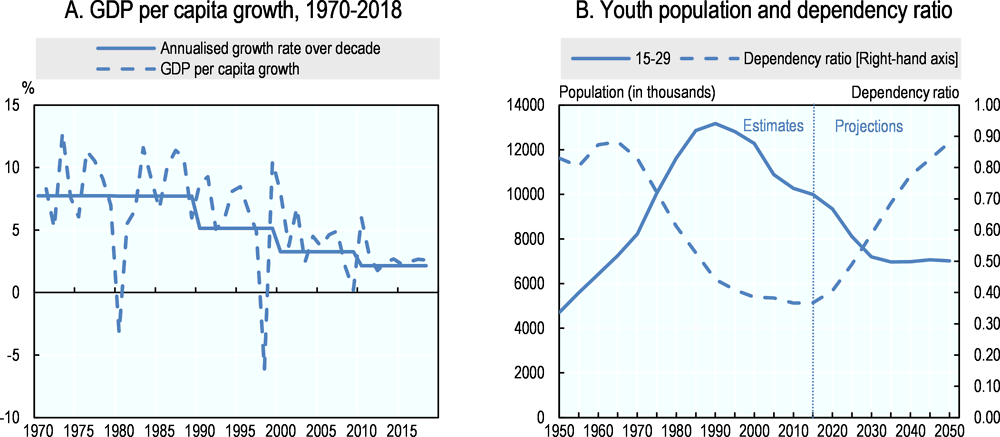

Current growth, 2.7% in 2018, is strongly affected by weaknesses in domestic demand and international trade as well as population ageing and dualism in the product and labour market. Future growth will depend in large parts on how well the country will master these challenges. The annualised decennial GDP per capita growth rate has dropped since the 1990s, from 7.7% in the ‘70s and ‘80s to 1.7% in the ‘10s (Figure 1.1, Panel A). Growth now equals the OECD average even though GDP per capita is still significantly lower in Korea than in leading OECD countries (OECD, 2018[2]). One contributing factor is that the period with a low dependency ratio – the number of children and old people to number of working-age individuals – benefitting Korea over the past four decades is ending (Figure 1.1, Panel B). The population of 15-29 year olds has already been shrinking since the 1990s.

Other potential obstacles for Korea’s future growth are the stark differences between small and large enterprises and between regular and irregular employment. Policies that were successful in the short term contributed to the problem of enterprise and labour market dualism in the longer term (Koh, 2010[3]). Large firms, concentrated in the manufacturing sector, generate 40% of sales but only employ 14% of workers. Small and medium-sized companies (SMEs), concentrated in the service sector, provide the bulk of jobs. But SMEs’ relative labour productivity has been trending downwards. It now equals around a third of the productivity of large companies, the forth lowest ratio in the OECD (OECD, 2018[2]). The labour market bifurcates not only between large and small companies, but also between regular and non-regular employment. Non-regular workers, such as part-time, temporary or dispatched workers, make up around a third of the workforce and frequently work in SMEs. The enterprise and employment dualities fuel income inequality because non-regular workers typically earn less than regular workers do: in 2016, the average hourly wage of non-regular workers was more than a third lower than the average hourly wage of regular workers (OECD, 2018[4]).

The two dualities lower growth prospects: small companies tend to stay small. Sometimes, they want to continue profiting from subsidies that are only available to SMEs, which in turn, limits employment growth. But the strong concentration of financial and human capital in large firms can also limit the growth of innovative small companies, reducing productivity growth.

Figure 1.1. Korea's economy was boosted by a young population, but ageing is reducing long-term growth prospects

Note: The dependency ratio is equal to the ratio of the number of individuals aged below 15 and above 64 to the number of individuals aged 15‑to‑64.

Source: United Nations (2017[5]), World Population Prospects and OECD (2018), “Growth in GDP per capita, productivity and UCL”, http://dotstat.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=PDB_GR.

1.3. The education and employment performance situation of Korean youth

The ageing population trend means that young Koreans today are part of smaller cohort than ten years ago. The fact that young workers are becoming increasingly scarce might suggest that they are highly valued on the labour market. However, as this section will show, many youngsters are not employed or have disappointing work conditions, despite their high educational achievements.

1.3.1. Youth labour market outcomes

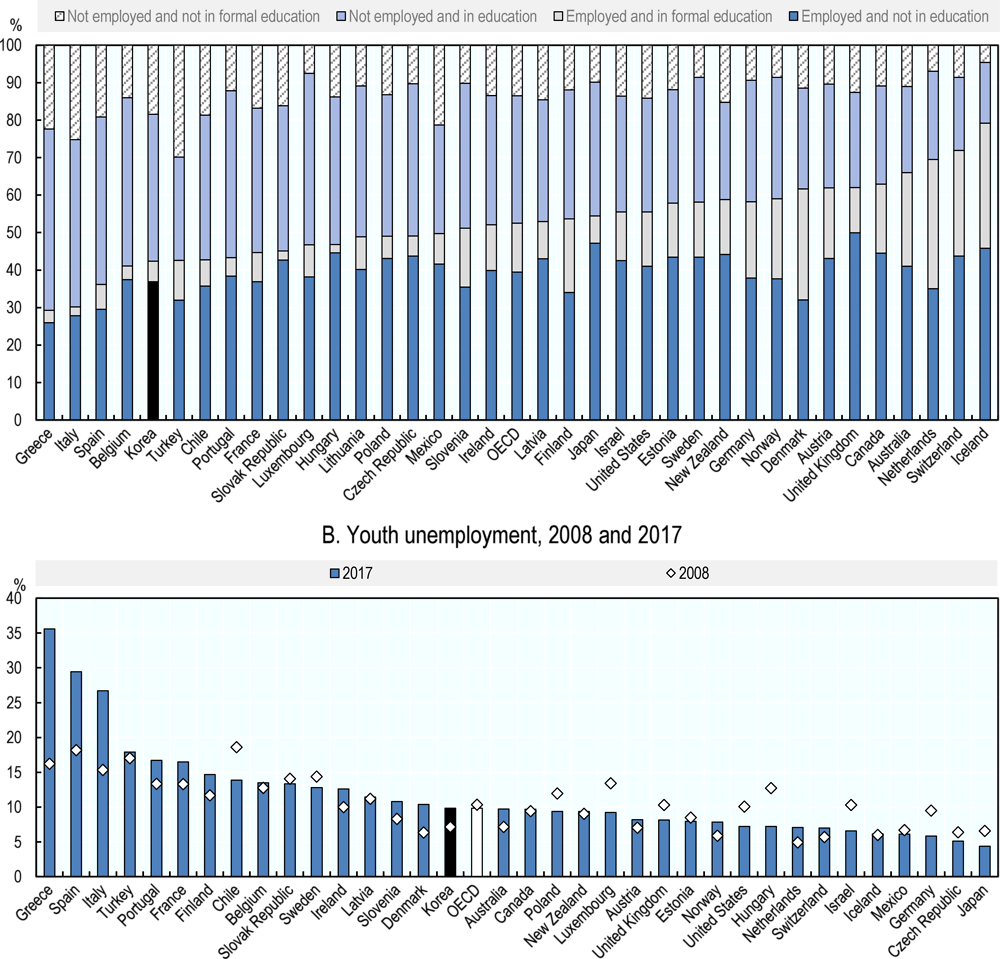

The employment rate of young Koreans is well below the OECD average. In 2017, 42% of youth aged 15-29 living in Korea were employed (Figure 1.2, Panel A). The 2017 OECD average was about a quarter higher (at 53%). The Korean youth employment rate fell by four percentage points between 1997 and 2017 due to decreases in the employment rates of 15-19 year olds (from 10 to 8%) and of 20-24 year olds (from 58% to 45%) that were partially offset by a slight increase among 25-29 year olds (from 68% to 69%). Youth employment declined more between 1997 and 1998 than between 2007 and 2008, mirroring the stronger employment effects of the Asian Financial Crisis than the more recent Global Financial Crisis (Lybecker Eskesen, 2010[6]).

Figure 1.2. Fewer than half of young people aged 15-29 in Korea are employed

Note: The reference year in panel A is 2017 except 2013 for New Zealand, 2014 for Japan, 2015 for Chile and Turkey and 2016 for the United States. The calculations exclude individuals with missing educational information or who are in military service. Youth are defined as 15-29 year olds.

Source: Calculations based on Labour Force Surveys by sex and age, OECD (2018[7]), Education at a Glance 2018, and Labour Force Surveys including the Economically Active Population Survey (Statistics Korea, 2017[8]).

Low employment rates touch most but not all population groups in Korea. In 2017, 88% of Korean men of aged 30-64 were employed, compared with 83% across the OECD and 91% in Japan. In contrast, aside from young men and women, women aged 30-64 also have a below-average employment rate: at 61%, it was four percentage points lower than the weighted OECD average. Women with young children in particular can find it difficult to combine caretaking activities with the long working hours that still continue to be the norm in Korea (Kang, 2017[7]), despite recent legal changes in maximum working hours.

Youth unemployment is not an exceptionally strong factor driving the low youth employment rate in Korea: at slightly below ten percent, the 2018 youth unemployment rate was in fact almost equal to the OECD average, though still more than twice as high as in Japan (Figure 1.2, Panel B). However, it is not surprising that the Korean population and politicians are concerned about youth unemployment since it has been trending upwards, from 7.1% in 2008 to 9.5% in 2018.

An important explanation for the low youth employment rate is that few young people combine education and employment. Indeed, fewer than one in eight of Korean students were employed, compared with around one in four across the OECD and even one out of three in Iceland. Their share has also only slightly increased over the last decade, from 11.2% in 2007 to 12.3% in 2017. The employment rate of young Koreans is also low because many of them take part in informal education or spend a long time preparing for company entry exams, accounting for 4.4% of all 15-29 year olds in 2017.

Many young people prefer to invest in further (formal or informal) education or prepare for employment exams to obtain a job in a large company or the public sector rather than accept a job with a small company. Job and wage conditions for regular workers at large companies tend to much more advantageous than at SMEs (OECD, 2016[8]). Although the investment may be rational, few young people eventually succeed in obtaining a high-quality job in a large enterprise (see section 1.3.5).

1.3.2. Educational investment

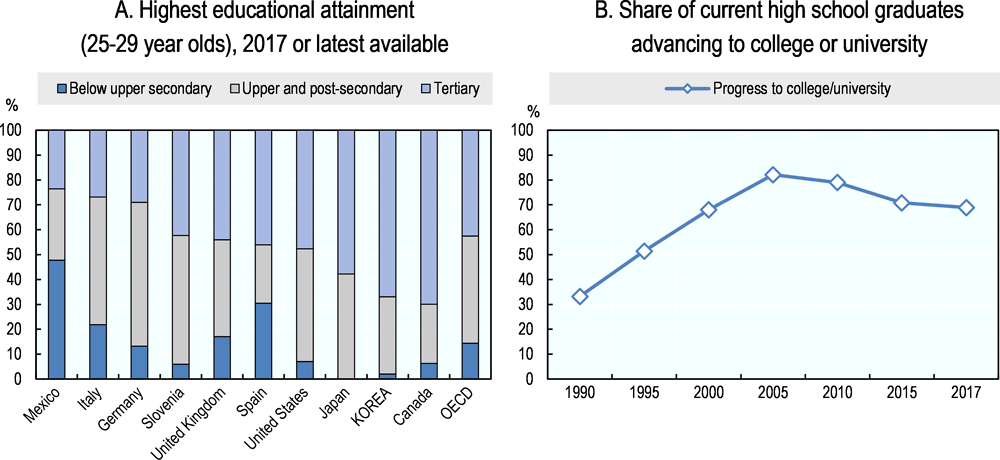

Virtually all young Koreans complete upper secondary education and more than two thirds of Koreans aged 25-29 obtain a college or university degree. As a result, Korea has among the most educated youth population in the OECD area (Figure 1.3, Panel A). Secondary students spend more hours studying than in any other OECD country that participated in the 2015 PISA programme: 51 hours, compared to the 44 hour average (OECD, 2017[9]). While the quality of colleges and universities varies, young Koreans generally leave school with a high level of skills: among the 24 countries or sub-national regions that participated in the Survey of Adult Skills, the skills of 16-24 year olds were only higher in Japan. In contrast, among Korean 55-65 year olds, they were the third lowest (OECD, 2013[10]).

The large skills gap between the younger and older groups demonstrates the extraordinary increases in educational attainments that occurred in Korea over the past half century (Cheon, 2014[11]). This educational expansion now seems to have come to a halt: the share of high school graduates who advanced to college or university reached an all-time high of 82% in 2005, but declined again to 69% in 2017 (Figure 1.3, Panel B).

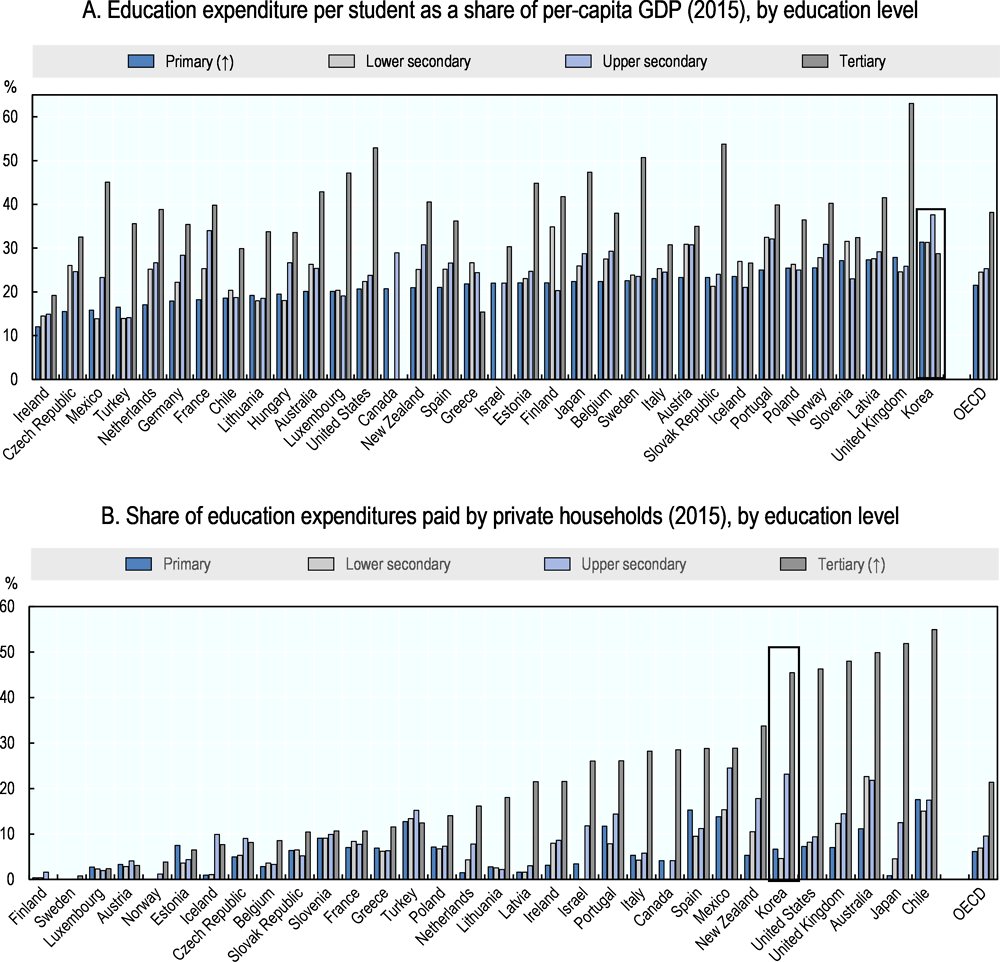

However, the high educational attainment comes at a substantial financial cost. Combined public and private expenditure on primary through upper secondary educational institutions is among the most elevated in the OECD (Figure 1.4, Panel A). The government bears almost all of the costs for primary and lower secondary education, while households finance around a quarter of the expenditures for upper and post-secondary education and 45% of expenditures for tertiary education (Figure 1.4, Panel B). National universities are predominantly funded by the government while private universities and colleges are predominantly funded by tuition (Jones, 2013[1]). Since the higher-ranked national universities do not only convey more prestige and better labour market prospects but also cost less in tuition fees, many parents invest in after-school private tuition to increase their children’s chance of admission. However, the situation has gone out of hand and expenses on private after-school teaching academies (hagwons) and other private tuition now amount to 1.1% of GDP (OECD, 2019[12]). These expenditures equal more than a fifth of combined public and private spending on regular educational institutions in Korea (5.4% of GDP in 2016, compared to the OECD average of 5.0%) (OECD, 2019[13]).

Figure 1.3. The majority of Korean young people choose to go to college or university

Note: The shares exclude observations with missing educational information. The latest available year is 2018 for Canada and Mexico and 2014 for Japan.

Source: Calculations based on Labour Force Surveys and Social Indicators (Statistics Korea, 2018[14]) (Statistics Korea, 2017[15]; Statistics Korea, 2011[16]; Statistics Korea, 2015[17]).

1.3.3. The NEET challenge

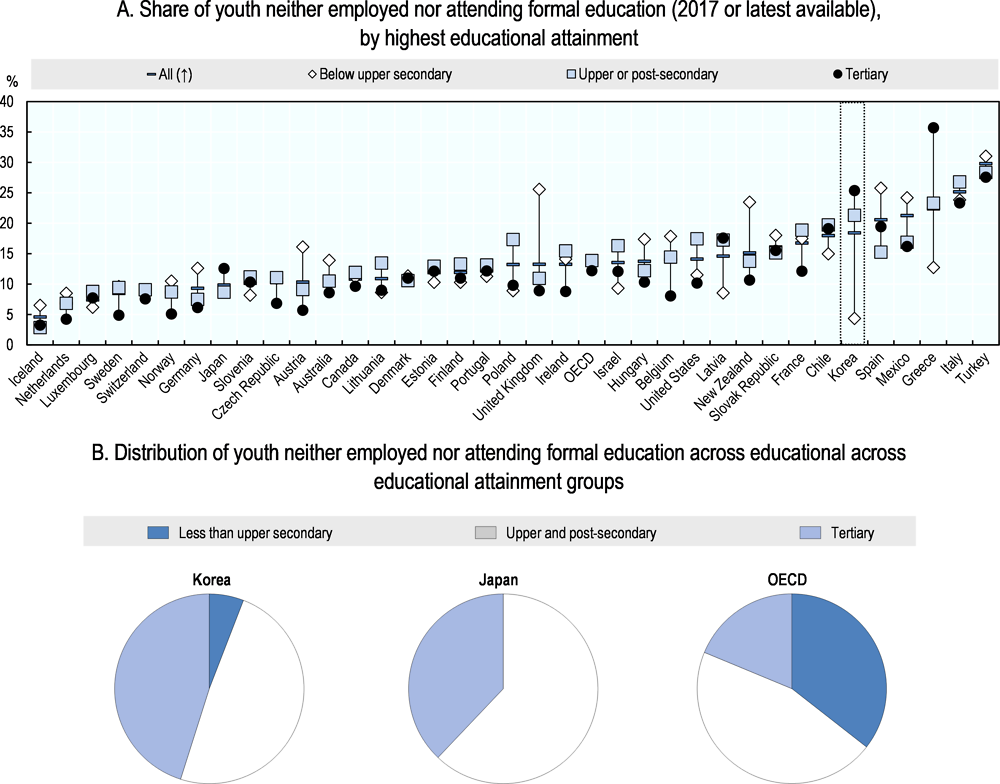

A considerable share of young Koreans are neither employed, nor engaged in formal education or training (the so-called NEETs). In 2017, the NEET rate reached 18.4% in Korea, compared with the 13.4% cross-country OECD average. The share is lower than the 22.1% recorded in Korea in 2000, but represents an increase from the low point of 17.9% in 2014. College and university graduates are more likely to be NEETs than those with lower educational attainments are, whereas the opposite applies in most other OECD countries. (Figure 1.5, Panel A).

About 45% of young Koreans who are neither employed nor attending formal education have a tertiary degree (Figure 1.5, Panel B). This share is much higher than the OECD cross-country average of around 18%, but somewhat comparable to the share in Japan. The shares of young Korean men and women who are in this situation are on average similar, but they are higher for men among under-25 year olds and higher for women among over-25 year olds.

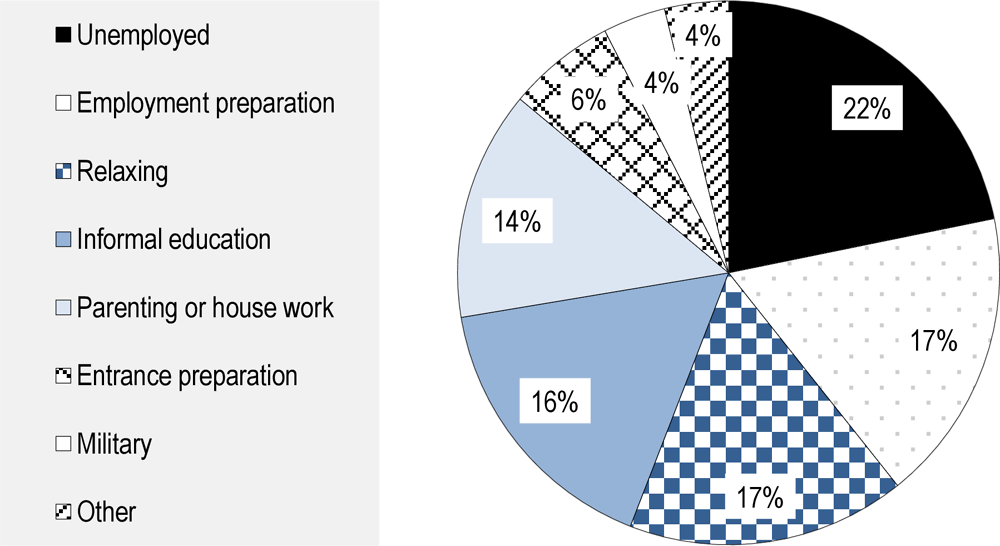

One of the reasons for the elevated share of college or university graduates who are NEET is that they may take breaks to attend informal educational institutions. While these young people are considered as NEETs in Figure 1.5 (in line with the OECD NEETs definition), they are actually preparing for university or company entry exams or following informal education courses, such as language courses. Calculations based on the Economically Active Population Survey suggest that 17% of all NEETs are preparing for company entry exams and 6% are preparing for school or university entrance exams (Figure 1.6). A further 16% are enrolled in informal educational activities. The remaining NEETS stay at home to take care of the household or kids (most of these carers are women) or relax (twice as frequently among men than among women).

Figure 1.4. Korean education expenditures are high and households shoulder an important burden for higher education

Note: Expenditures per level of education are sorted from lowest to highest expenditure on primary education as a share of per-capita GDP. The share of education expenditures paid by private households is sorted from lowest to highest for tertiary education. Data are missing for Denmark and Switzerland (Panel A and B) and in addition for Panel B for Germany and Hungary. The OECD averages are unweighted.

Source: Education Finance Indicators dataset based on Education at a Glance 2018 – Part C (OECD, 2018[18]).

Overall, 4.4% of Korean civilian youth aged 15-29 were enrolled in some form of informal education or exam preparation in 2017 as their primary activity. Excluding these youth would imply a drop in the overall NEET rate from 18.4% to 14.1%, only slightly higher than the OECD average of 13.4%. Among university graduates, the NEET rate would drop from 25.4% to 22.7%, remaining nevertheless well above the OECD average. While these calculations do not include military personnel, it is clear that conscription is one of the factors that increases the age at which young Korean men enter the labour force (see Box 1.1).

Figure 1.5. Korean college or university graduates are more likely to be NEETs than their lower-educated peers

Note: The reference year is 2017 except 2014 for Japan, 2015 for Chile and Turkey and 2016 for the United States. The calculations exclude individuals with missing educational information or who are in military service. Youth are defined as 15-29 year olds.

Source: Calculations based on Labour Force Surveys and OECD (2018[18]), Education at a Glance 2018.

The comparatively high share of youth in informal education in Korea remains a challenge for several reasons. First, while informal education may complement formal education, its widespread use indicates a gap between skills supply and demand. Many students think the formal education system does not equip them with the skills they view as prerequisites for success (Jang and Kim, 2004[19]). Employers seem to judge the formal education degrees as insufficient measures of someone’s skill, preferring their own employment exams to select their employees. Second, informal education also exists in other countries: the NEET rates presented above would drop by three to five percentage points for countries such as Denmark, Spain and Sweden if informal education were taken into account (OECD, 2016[20]).

Figure 1.6. Some Korean NEETs are in informal education

Source: Authors' calculations based on the 2017 Youth Supplement to the Economically Active Population Survey (Statistics Korea, 2017[21]).

Box 1.1. Conscription in Korea Almost all young Korean men are required to serve in the military.

Depending on the military branch, the initial military service period ranges from 21 to 24 months. President Moon’s July 2018 Defense Reform 2.0 plan foresees to shorten the service by two or three months (depending on the branch) until 2022 (Channel NewsAsia, 2018[22]). Former conscripts remain part of the reserve for another six years, during which they have to spend a few days a year in training. In contrast, nearly two thirds of OECD countries no longer actively conscript youngsters (although two have recently re-introduced conscription). And with the exception of Israel, where young women serve for a minimum of 24 months and young men for 36 months, the conscription period is shorter in all other OECD countries (CIA, 2018[23]). Most Korean men complete their military service obligation during their twenties, often taking a break from their studies.

There are few alternatives to military service. Conscientious objectors can be sentenced and jailed, but the Constitutional Court ruled that the government will have to create an alternative civilian service (Griffiths, 2018[24]). Currently, alternative service is available only to some highly qualified engineers or scientists working for selected government or industry institutes.

Sources: Channel NewsAsia (2018), “South Korea to reduce length of mandatory military service”, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/south-korea-military-service-reduce-length-army-10569914.

CIA (2018), “Military Service Age and Obligation”, The CIA World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2024.html. Griffiths (2018), “South Koreans may no longer face jail if they refuse to serve in the military”, https://edition.cnn.com/2018/06/29/asia/south-korea-military-service-intl/index.html.

1.3.4. Job search and tenure

It can take a while for Korean school leavers to settle into a job. In 2017, the average length of time between leaving school and starting a first job was nearly a year.1 At the same time, more than half of young people managed to start a job within just three months of leaving education. These durations compare unfavourably with a number of OECD countries such as Australia, Canada, Germany and the United States, but are comparable or lower than durations observed in the Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom in 2011 (Quintini and Martin, 2014[25]).2

The higher the education level, the shorter does the job search appear to be. Former high school students on average take around sixteen months to start working, college and university students nine months and postgraduate students four months. When those who have not yet found a job are included, the average durations increase by one to two months. The share who started their first job within three months of graduating ranges from 51% among high school graduates to 56% among university, 59% among college and 68% among graduate school graduates.

A longer job search is not inherently negative if it leads to a better match and improved employment conditions. However, in Korea, shorter or longer job search durations are unrelated to having a first job with a short contract duration. But since the group that searches for a job for a long time likely includes both highly qualified applicants that can ‘afford’ to wait for the best possible job as well as those who have barriers to recruitment, for the individual student, waiting for a better job can be rational. Finally, the comparison may under-state the actual job search duration among tertiary dropouts or graduates: they may delay their graduation date strategically in order to avoid gaps on their resumes (Yang, 2015[26]).

Despite the lengthy job search, many young Koreans do not stay at their first job for a long time. In 2017, young people kept their first job for an average of around one and a half years. In 2004, the duration was around three months longer. Tertiary graduates stay slightly longer than those who only graduated from high school, but the difference amounts to only three months. Almost three out of five young people left their first job because they were dissatisfied with their work conditions or with their progression possibilities. Overall, Koreans in their early twenties have lower job tenures than youth in other OECD countries. In 2015, employed 20-24 year olds in other OECD countries had held their job for an average of 1.8 years, twice as long as in Korea.3 However, by the time they are in their late twenties, the job tenure rates of Koreans and all OECD youngsters are both equal to 2.1 years.

1.3.5. Job quality and earnings

Finding a job is important for a person’s well-being and future prospects, but so is the quality of that job – that is, whether it is open-ended or temporary, pays an adequate salary, matches the individual’s skills and provides good working conditions.

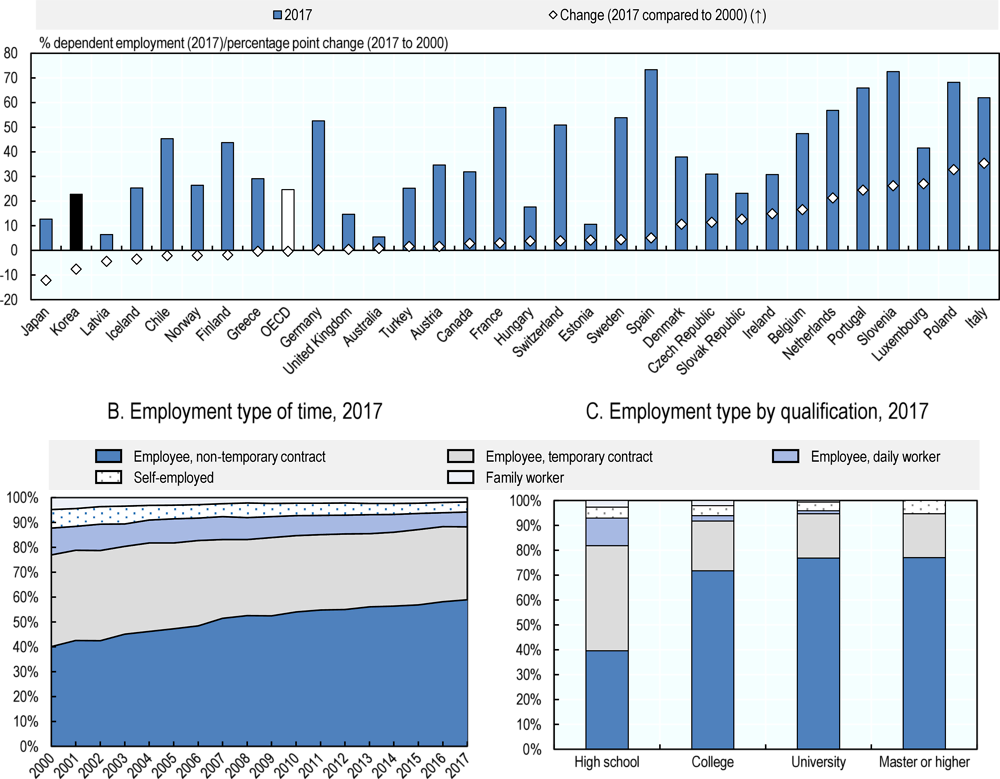

A decreasing share of young workers have temporary contracts, and particularly so if they are highly educated. Between 2000 and 2017, the share of temporary employees and daily workers among young workers dropped from 47.7% to 35.4% (Figure 1.7, Panel B). Across the OECD, in contrast, the incidence of temporary employment among 15-24 year-old employees stayed almost constant over the same period, around 24.5% (Figure 1.7, Panel A). This average hides that in some countries including Ireland, Italy and Portugal, the incidence drastically increased while in Japan and Korea, it decreased significantly. In 2017, about one in two employed upper secondary school graduates and one in five tertiary graduates were employees with a temporary contract or daily workers (Figure 1.7, Panel B).

Part-time employment, while expanding, is still comparatively uncommon in Korea, especially among highly educated youth. In 2017, only 15.9% of young Korean workers did not work full-time, compared with the latest OECD average of 22.8%. In Korea as well as across the OECD, part-time employment is more common among younger than older workers. Korean youth part-time employment has more than doubled since 2000, when it stood at 6.7%. More than half of these part-time workers are enrolled in formal education. However, it is unclear whether part-time work is voluntary or whether they cannot find full-time alternatives as data is lacking. Part-time work is much more common among upper secondary (26.5%) than among tertiary graduates (7.4%). OECD countries have on average a similar share of part-time work among secondary graduates but twice the share among tertiary graduates.

Figure 1.7. Regular employment is becoming more common and is elevated among highly educated young people

Note: Panel A: The earlier reference year is 2001 for Australia and Poland, 2004 for Korea and 2010 for Chile. With the exception of panel A, the figures are restricted to employed 15-29 year olds. The ‘Less than high school’ category is omitted because of the low number of observations.

Source: OECD (2018[27]), “Incidence of permanent and temporary employment” and authors’ calculations based on the Economically Active Population Survey (Statistics Korea, 2017[21]).

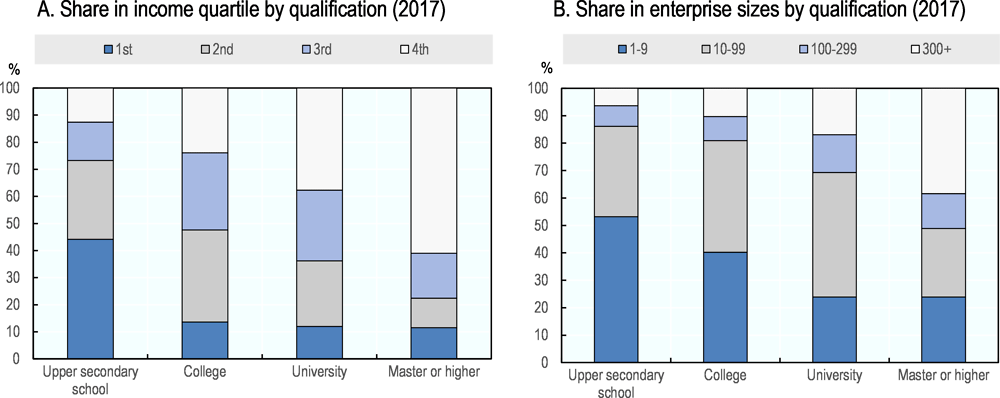

An undergraduate or postgraduate university degree significantly increases the chances of earning a high income and working for a large enterprise, but by no means guarantees it. Education earnings premia decreased throughout the 1980s and 1990s (Kis and Park, 2012[28]) but were stable from 2005 to 2016 (OECD, 2018[18]). However, the Korean earnings premium for graduates from higher education is below the OECD average (OECD, 2019[13]) and for a significant share, their investment does not pay off financially. In particular, the 2017 Economically Active Population Survey indicates that 29% of college and 18% of undergraduate university degree holders earned less than the average earnings among high school graduates, backing up earlier results for 2010 (Lee, Jeong and Hong, 2014[29]). When tuition fees and forgone earnings are considered, the financial pay-off from higher education is likely negative for a substantial share of university and in particular of college graduates.

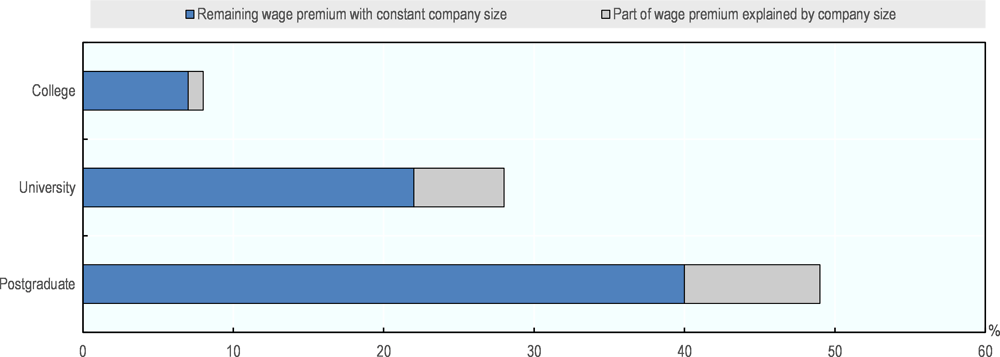

Earnings and working conditions are often better at large companies than at SMEs (Ha and Lee, 2013[30]), but the concentration of more educated young people in larger enterprises (Figure 1.8, Panel B) does not explain most of their higher labour income (Figure 1.9).

Figure 1.8. University graduates often earn more and work more frequently in large companies

Note: The calculations are restricted to employed 15-29-year olds. The ‘Less than high school’ category is omitted because of the low number of observations. Each income quartile includes approximately 25% of employed youth.

Source: Calculations based on the 2017 Economically Active Population Survey (Statistics Korea, 2017[21]).

Figure 1.9. The higher employment rates with large companies only explain a small part of the higher average earnings of university graduates

Note: These results are based on regression analyses. The dependent variable is the hourly labour income and control variables are age, sex and year. The combined length of the two boxes indicate the results of the regressions that do not include the company size as a control variable; while the length ‘Remaining wage premium’ boxes alone indicate the wage premium that remains when company size is controlled for.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the 2007-2015 Youth Panel (National Youth Policy Institute, 2015[31]).

1.3.6. Skill and study mismatch

Indicators of skill mismatch suggest that there is significant scope for improvement in efficiently using the skills of young people in Korea, in particular with respect to the field of study. Data from the 2012 OECD Survey for Adult Skills (PIAAC) reveal that 62.0% of 16-29 year old employed Koreans were mismatched to their job in terms of their field of study, qualification or literacy; a share that is similar to the OECD average of 61.6% across the 22 OECD countries that participated survey (OECD, 2014[32]). The qualification mismatch (24.9% in Korea), which indicates whether someone has a level of education above or below the education requirements usual for their occupation, and the literacy mismatch (12.8%), which indicates whether someone has literacy skills above or below those usually required for their occupation, are both below the respective OECD averages of 36.4% and 17.3%. In contrast, the field of study mismatch (46.8%) is ten percentage points higher in Korea than the OECD average and the fifth highest among the participating countries.

Rising education levels have led to falling under-qualification and rising over-qualification. Calculations based on the Korea Youth Panel Survey of the National Youth Policy Institute (2015) illustrate that the share of youth who reported that their current job requires a higher education level than they have decreased from 13.6% in 2007 to 10.0% in 2015.4 The share with a higher than required education level increased from 26.6% to 33.2%. In 2015, 44.5% of university and 78.5% of postgraduate degree holders reported that they were over-qualified for their job. At the same time, almost a third of employed high school and more than ten percent of college graduates felt they were under-qualified.

More positively, self-reported field of study mismatch appears to be falling and are lower for the highly educated. In 2007, 30.4% of the employed 15-29 year olds stated that the agreement between their job content and their major was (very) low. By 2015, the share had almost halved to 16.4%. About one quarter of high school graduates, one fifth of college graduates and one eighth of university graduates in 2015 felt that there was a low agreement.

1.4. Youth poverty and well-being

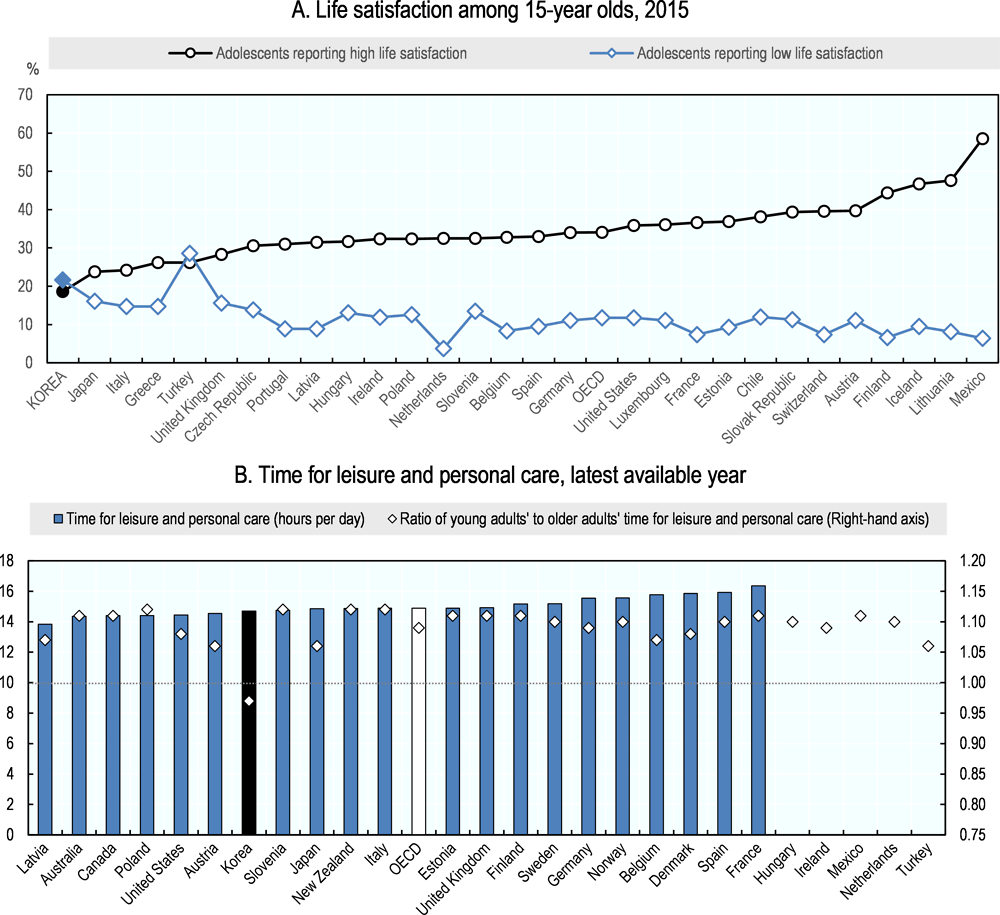

International data sources show that young Koreans are relatively unsatisfied with their life. Data from the 2015 OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) presented in Figure 1.10 (Panel A) indicate that Korea has the lowest share of young people reporting high life satisfaction among OECD countries and the second-highest share of those reporting low satisfaction. According to the World Values Survey (Inglehart et al., n.d.[33]), only 31% of the 18-28 year-old Koreans rate their life satisfaction between 8 and 10 on a scale of 1 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied), compared with 54% on average in sixteen OECD countries.

Domestic data sources indicate life satisfaction levels that vary across age groups and engagement in education or employment. According to the 2014 Korea Labour and Income Panel Survey (Korea Labor Institute, 2014[34]), 51% of young people are (very) satisfied with their lives, compared with 48% of 30-64-year olds and 37% of seniors. Among young people, NEETs are less satisfied with their lives than others: only 37% are (very) satisfied as opposed to 52% among non-NEETs.

A lack of free time probably contributes to the comparatively low life satisfaction. Korea is the only OECD country where young people devote less time to leisure and personal care than older working-age adults (Figure 1.10, Panel B). The large number of hours devoted to studying – the highest in the OECD (OECD, 2017[9])– explains this time scarcity. Paradoxically, students who study particularly long hours tend to be more satisfied with their life than those that study fewer hours (OECD, 2017[35]). One possible reason could be that these students feel more optimistic about their opportunities later in life.

Figure 1.10. Korean adolescents have the lowest satisfaction among OECD countries and comparatively little free time

Source: OECD Children Well-Being Dataset and How’s Life (OECD, 2017[36]), “Table 2.A.4. Horizontal inequalities in well-being by age group, young vs. middle-aged adults, latest available year.”

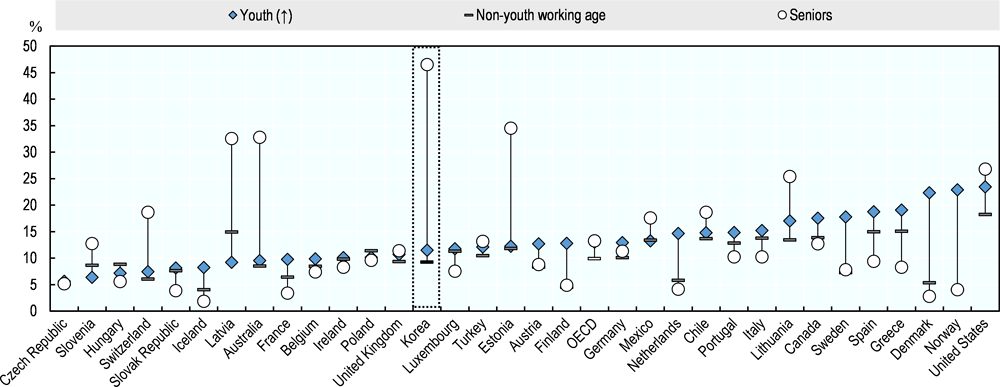

The share of young persons who are estimated to be poor is much lower than the share among older persons. In fact, the difference in the estimated poverty rates between seniors and working-age individuals is higher in Korea than in any other OECD country (Figure 1.11). When a multidimensional poverty measure is used, taking into account net wealth, housing, health, employment, social and cultural capital and security in addition to income, the poverty rates of 19-34 year olds becomes similar to those of 35-64 year olds (Kim and Kim, 2018[37]).

The risk of poverty is much higher among young people who are no longer living at home: In Korea, 23% of young people who had moved out from home were poor, compared with only 8% of those who were still living with their parents. On average across the OECD, pattern is the same: 19% of those living with their parents were poor compared to 8% who were not. The share of young people who continue living at home is much higher in Korea (84.2% in 2016) than across the OECD (61.3%). Only in a handful of other OECD countries, including Greece, Italy and the Slovak Republic, do as many young people live with their parents. Part of the reasons may be cultural, but these countries also share a comparably low youth employment rate.

Figure 1.11. Compared with the elderly, few young Koreans live in poverty

Note: Individuals are defined as poor if they live in a household with an equivalised household income (household income adjusted by the number of household members) below 50% of the median income. The poverty rate of seniors in Australia is high because many retirees draw their pensions as a lump sum instead of monthly payments. The statistic refers to 2015 for Turkey and 2016 for Belgium, Canada, Hungary, Iceland, Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Korea Labor and Income Panel Survey, the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions, the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey, the Chile National Socioeconomic Characterization Survey, the Canadian Income Survey , the German Socio-Economic Panel, the National Survey on Income and Expenditure Dynamics and the Current Population Survey.

1.5. Wrap-up

Young Koreans are affected by the slowdown in economic growth, as shown by an increase in their unemployment rate. Also the employment rate of young Koreans has declined over the past decade and currently stands well below the OECD average. Instead of working, young people prefer to invest heavily in their education, both formally and informally, and tend to spend a long time preparing for company entry exams. While Korean youth are amongst the most educated and skilled, the financial costs of education for the government and parents are very high, as is the personal investment of young people in terms of time and energy devoted to studying.

Youth unemployment in Korea is equal to the OECD average, but it has been rising slowly in recent years and the share of youth who are neither employed nor attending a formal educational institution (NEETs) is considerably higher than OECD average. The NEET rate is particularly high among college or university graduates, in contrast to the situation in many OECD countries, in part because they frequently attend informal education and prepare for company entry exams. While informal education may complement formal education, its widespread use indicates a gap between skills supply and demand. Indeed, indicators of skill mismatch suggest that there is significant scope for improvement in efficiently using the skills of young people.

A university degree significantly increases the chances of earning a high income and working for a large enterprise. However, when tuition fees and foregone earnings during the years of study are taken into account, the financial pay-off from higher education is likely negative for a substantial share of university and in particular of college graduates.

The Korean educational and labour market contexts reduce life satisfaction. Holding the pole position in hours spent studying puts Korean adolescents firmly at the rear of reported life satisfaction among their peers in the OECD. Nevertheless, young Koreans are still in a more enviable position than retirement-age Koreans in terms of both higher life satisfaction and lower poverty rates.

Improving the labour market outcomes for young people and making better use of their economic potential as workers requires reforms in a range of policy areas. The remainder of this report explores causes and consequences for skills mismatches and a difficult school to work transition, as well as possible policy remedies to improve the social and labour market outcomes of young Koreans.

References

[22] Channel NewsAsia (2018), “South Korea to reduce length of mandatory military service”, Channel NewsAsia, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/south-korea-military-service-reduce-length-army-10569914.

[11] Cheon, B. (2014), “Skills Development Strategies and the High Road to Development in the Republic of Korea”, in Salazar-Xirinachs, J., I. Nübler and R. Kozul-Wright (eds.), Transforming Economics - Making Industrial Policy Work for Jobs, Growth and Development, International Labour Office, Geneva.

[23] CIA (2018), Military Service Age and Obligation, The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2024.html (accessed on 2 November 2018).

[24] Griffiths, J. (2018), “South Koreans may no longer face jail if they refuse to serve in the military”, CNN, https://edition.cnn.com/2018/06/29/asia/south-korea-military-service-intl/index.html.

[30] Ha, B. and S. Lee (2013), “Dual dimensions of non-regular work and SMEs in the Republic of Korea - Country case study on labour market segmentation”, Employment Sector Employment Working Paper, No. 148, International Labour Office, Geneva.

[33] Inglehart, R. et al. (n.d.), World Values Survey: Round Six - Country-Pooled Datafile Version, JD Systems Institute, Madrid, http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp.

[19] Jang, S. and N. Kim (2004), “Transition from high school to higher education and work in Korea, from the competency-based education perspective”, International Journal of Educational Development, Vol. 24/6, pp. 691-703, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.IJEDUDEV.2004.04.002.

[1] Jones, R. (2013), “Education Reform in Korea”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1067, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k43nxs1t9vh-en.

[7] Kang, J. (2017), “Evaluating Labor Force Participation of Women in Japan and Korea: Developments and Future Prospects”, Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, Vol. 23/3, pp. 294-320, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2017.1351589.

[37] Kim, M. and S. Kim (2018), Multidimensional Poverty of Youth in South Korea, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, Sejong.

[28] Kis, V. and E. Park (2012), A Skills beyond School Review of Korea, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264179806-en.

[3] Koh, Y. (2010), “The Growth of Korean Economy and the Role of Government”, in Il, S. and Y. Koh (eds.), The Korean Economy - Six Decades of Growth and Development, Korea Development Institute, Seoul.

[34] Korea Labor Institute (2014), Korea Labor and Income Panel Survey, Korea Labor Institute, Sejong, https://www.kli.re.kr/klips_eng/contents.do?key=251.

[29] Lee, J., H. Jeong and S. Hong (2014), “Is Korea Number One in Human Capital Accumulation - Education Bubble Formation and its Labor Market Evidence”, KDI School Working Paper Series, No. 14-03, KDI School, Seoul.

[6] Lybecker Eskesen, L. (2010), “Labor Market Dynamics in Korea - Looking Back and Ahead”, Korea and the World Economy, Vol. 11/2, pp. 231-261.

[31] National Youth Policy Institute (2015), Korea Youth Panel Survey.

[13] OECD (2019), Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f8d7880d-en.

[12] OECD (2019), Rejuvenating Korea: Policies for a Changing Society, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c5eed747-en.

[18] OECD (2018), Education at a Glance 2018: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2018-en.

[2] OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-kor-2018-en.

[27] OECD (2018), OECD.Stat, http://dotstat.oecd.org/?lang=en.

[4] OECD (2018), Towards Better Social and Employment Security in Korea, Connecting People with Jobs, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264288256-en.

[9] OECD (2017), “Do students spend enough time learning?”, PISA in Focus, No. 73, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/744d881a-en.

[36] OECD (2017), How’s Life? 2017: Measuring Well-being, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/how_life-2017-en.

[35] OECD (2017), Results from PISA 2015 Students’ Well-Being - Korea Country Note, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/PISA2015-Students-Well-being-Country-note-Korea.pdf.

[20] OECD (2016), Investing in Youth: Sweden, Investing in Youth, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267701-en.

[8] OECD (2016), OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-kor-2016-en.

[32] OECD (2014), OECD Employment Outlook 2014, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2014-en.

[10] OECD (2013), OECD Skills Outlook 2013: First Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264204256-en.

[25] Quintini, G. and S. Martin (2014), “Same Same but Different: School-to-work Transitions in Emerging and Advanced Economies”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 154, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jzbb2t1rcwc-en.

[14] Statistics Korea (2018), 2017 Social Indicators, http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/11/4/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=371114&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&searchInfo=&sTarget=title&sTxt=.

[15] Statistics Korea (2017), 2016 Social Indicators, Statistics Korea, Sejong, http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/11/4/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=364663&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&sTarget=title&sTxt=.

[21] Statistics Korea (2017), Economically Active Population Survey, Statistics Korea, Seoul, http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/5/2/index.board.

[17] Statistics Korea (2015), Social Indicators in 2014, Statistics Korea, Seoul, http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/11/4/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=335111&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&sTarget=title&sTxt=.

[16] Statistics Korea (2011), 2010 Social Indicators in Korea, Statistics Korea, Seoul, http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/11/4/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=273265&pageNo=&rowNum=10&amSeq=&sTarget=&sTxt=.

[5] United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, P. (2017), World Population Prospects Volume I, United Nations, New York.

[26] Yang, K. (2015), “With jobs scarce, South Korean students linger on campus”, Reuters News, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-southkorea-youth-unemployment/with-jobs-scarce-south-korean-students-linger-on-campus-idUKKBN0KA1UQ20150101.

Notes

← 1. The results presented in this section are calculations based on the Youth Supplement of the 2017 Economically Active Population Survey (Statistics Korea, 2017[21]).

← 2. The durations are not directly comparable between Korea and the other OECD countries. The Korean duration is equal to the reported length of time it took to find the first job after graduation. For the other countries, it is the difference between the weighted average of the age of entry into employment and the weighted average of the age of exit from education. The authors note that this measure does appear to match up with evidence from panel data. Given more recent improvements in labour market outcomes for youth across OECD countries, the 2011 values may exceed current ones.

← 3. The job tenure information by age group is taken from “Employment by job tenure in intervals – average tenure” (OECD, 2018[27]). Job tenure for the first job by education is calculated based on the 2015 August supplement of the Economically Active Population Survey (Statistics Korea, 2017[21]).

← 4. The mismatch calculations differ between the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) and the Youth Panel. The qualification mismatch indicator in PIAAC compares the respondents’ education level with the self-reported qualification that ‘someone would need to get their type of job’. In the Youth Panel, the respondents’ education level is compared to the self-reported minimum level of education ‘required to carry out the current job’. The PIAAC field of study mismatch measure is based on a comparison of the occupation (at the 3-digit ISCO classification level) with the field the worker specialised in. It is hence not self-reported. The Youth Panel field of study is based on the question how the current job content compares with their major.