This chapter looks at the policies and programmes that Korea has in place to support young people in a weakening labour market. The chapter starts by comparing labour market outcomes of youth with those of older generations, as well as with youth in other OECD countries. It then assesses the coverage and adequacy of the programmes and policies aimed at re-engaging young jobseekers in employment and at providing them with comprehensive income and housing support. The chapter finishes with a discussion on how to address labour market duality and facilitate access to rewarding employment.

Investing in Youth: Korea

3. Supporting youth in a weakening labour market

Abstract

3.1. Youth performance in a weakening labour market

Korea’s labour market is known to be highly segmented, with large differences in employment conditions between regular and non-regular workers and between small and large companies. Numerous studies have documented how this labour market duality has resulted in earnings inequality and economic inefficiency (OECD, 2013[1]; Ha and Lee, 2013[2]; Hong, 2017[3]; Schauer, 2018[4]). As discussed in Chapter 2, young Koreans have been investing heavily in education to increase their chances for a high quality job and many spend a lot of time preparing for company entry exams. While their employment conditions have improved over the past decade, weakening economic growth is translating into increasing youth unemployment and longer school-to-work transitions.

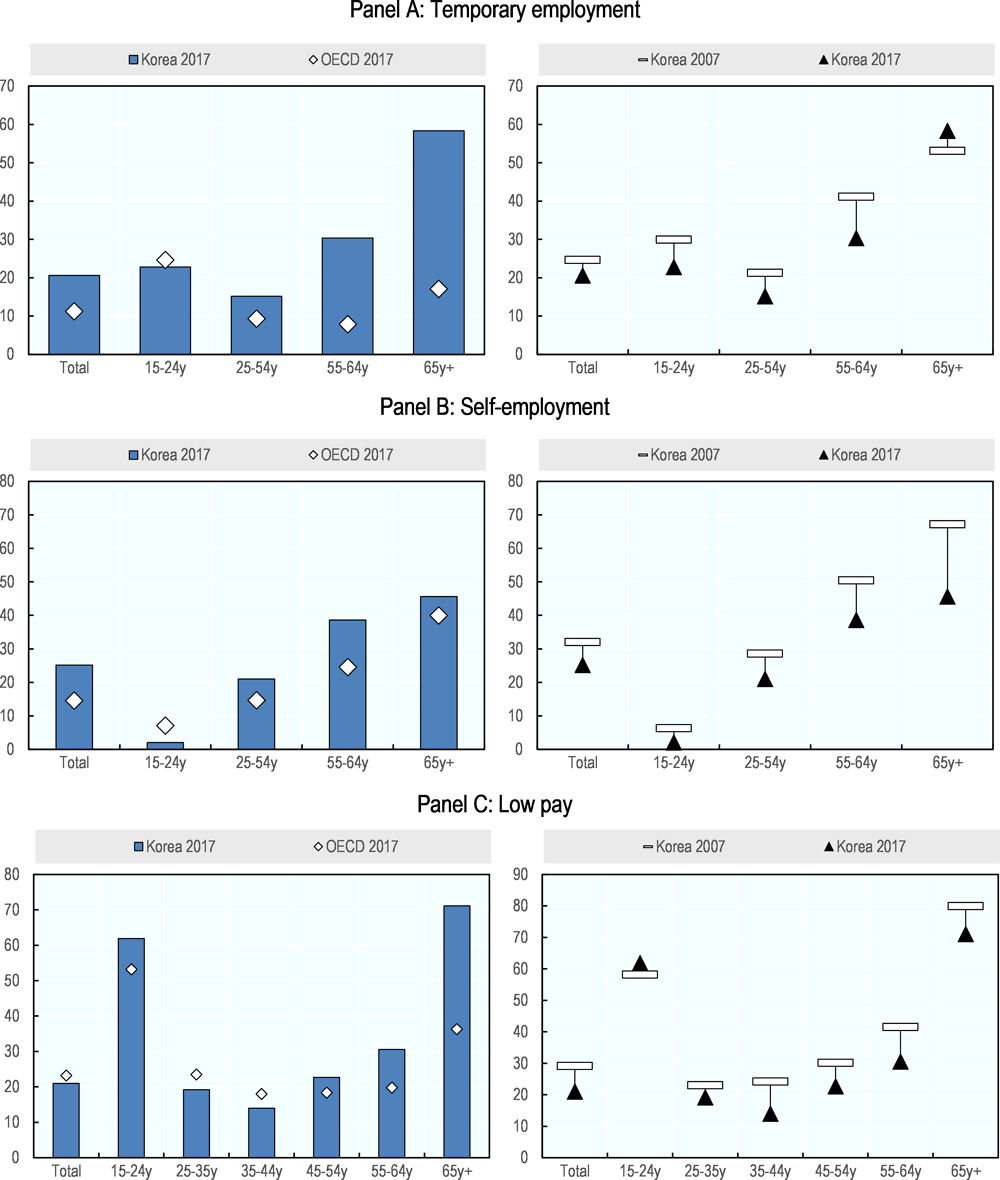

With one in five employees working under a temporary contract, Korea belongs to the top five of OECD countries in terms of temporary employment incidence. However, Figure 3.1, Panel A, reveals that the high share of temporary employment is largely driven by older generations, reaching nearly 60% of all employees aged 65 and more. In contrast, the incidence of temporary employment among Korean youth was below the OECD average in 2017, at 22.8% versus 24.6% respectively. Across all age groups, with the exception of older workers, the incidence of temporary employment significantly declined between 2007 and 2017.

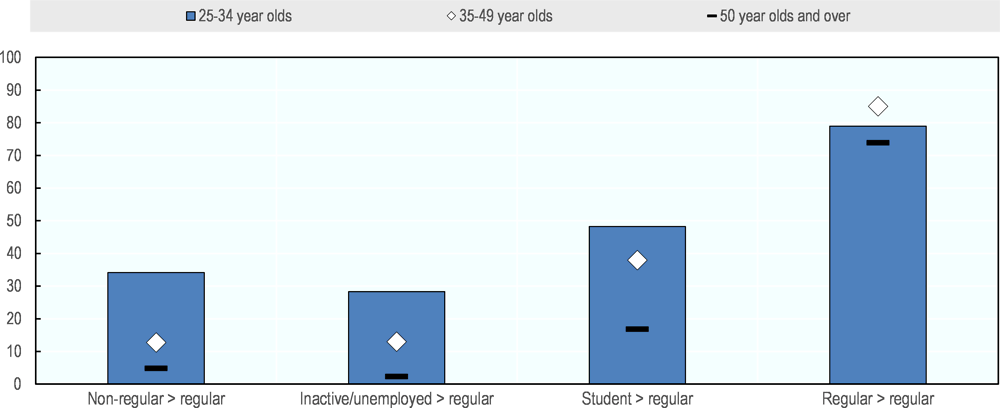

Transitions from non-regular to regular jobs are also more frequent among youth than they are among older generations. Calculations based on the longitudinal data of the Korea Labor and Income Panel Survey reveal that one out of three young workers with a non-regular contract move into a regular one within a time span of three years (Figure 3.2).1 In contrast, transition rates are very low for prime-age workers (13%) and even lower for older workers (5%). A significant share of unemployed or inactive youth (28%) manages to obtain a regular job within three years. The majority of youth who have a regular contract maintains that situation three years down the lane (79%).

The incidence of self-employment is also exceptionally high in Korea, ranking fourth among OECD countries. However, as with temporary employment, it is mainly older workers who work as self-employed: 38.6% among 55-64-year olds and 45.6% among those aged 65 and over (Figure 3.1, Panel B). Among youth aged 15-24, the incidence of self-employment in Korea is only one third of the OECD average (2.1% versus 7.1% respectively). For all age groups, the share of self-employment in total employment has significantly declined over the past decade.

While the existence of different employment arrangements is not an inherent concern in itself, labour market duality becomes a problem if it results in inefficiencies and welfare losses. As discussed in (OECD, 2013[1]), earnings inequality has risen particularly rapidly in Korea since the mid-1990s, at the same time that non-regular work was expanding. The incidence of low-paid work is particularly high among the youngest and oldest workers, reaching 62% and 71% of the age groups 15-24 years and 65 years and more (Figure 3.1, Panel C).2 By the time young people are in their late twenties, the incidence of low pay is lower in Korea than OECD countries on average. The low pay incidence for this group also declined between 2007 and 2017.

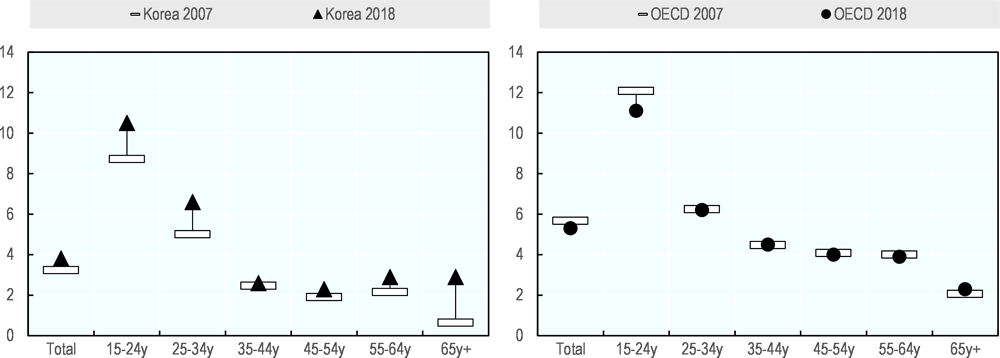

Despite the relatively promising labour market outcomes among youth compared with older generations, weakening economic growth is translating into increasing youth unemployment (Figure 3.3). While the unemployment rate among 15-24 year olds is still lower in Korea than in the OECD on average (10.5% and 11.1% respectively in 2018), the rate has markedly increased over the past decade. The observed increase is in contrast with other age groups, as well as with OECD trends. For the group 25-34 year olds, the unemployment rate was close to the OECD average in 2018, at 6.6% and 6.7% respectively, but higher than the 5.0% in 2007.

Figure 3.1. Young workers are less likely to have temporary contracts or to work as self-employed than their peers in OECD countries

Note: Temporary employment is expressed as a share of total dependent employment and self-employment as a share of total employment. The incidence of low pay refers to the share of full-time employees and self-employed workers earning less than two-thirds of median earnings for full-time workers (working 30+ hours). OECD averages are weighted averages of all OECD countries. The OECD low pay statistic excludes Canada, Japan, Lithuania and New Zealand.

Source: OECD Labour Force Statistics for Panel A and B; and authors' calculations based on household surveys for Panel C.

Figure 3.2. Transitions from non-regular to regular jobs are frequent among youth

Note: A non-regular worker is defined as a person who is working but not as a permanent full-time employee.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2005-2014 waves of the Korea Labor and Income Panel Survey (Korea Labor Institute, 2014[5]).

Figure 3.3. Youth unemployment in Korea is still below OECD average but it is rising

Source: OECD Labour Force Statistics.

The outcomes presented in Figure 3.1-Figure 3.3 suggest that labour market conditions affect younger and older generations in different ways. Unlike older workers who may have no alternative but accepting low quality jobs, many young people can rely on family support and prefer to wait for better opportunities. Rather than accepting a non-regular job, they have the possibility to prolong their search for a good-quality job. In the meantime, they remain unemployed or continue studying.

3.2. Improving support for young people

3.2.1. OECD Action Plan for Youth

Tackling weak aggregate demand and promoting job creation through macroeconomic policies are essential for bringing down youth unemployment and giving young Koreans a better start in the labour market. However, as put forward in the OECD Action Plan for Youth that was agreed upon by OECD Ministers in 2013 (see Box 3.1 for more details), a brighter economic outlook may not solve all of the difficulties youth face in gaining access to productive and rewarding jobs; cost-effective measures addressing structural issues are also needed.

Chapter 2 already discussed the need to improve the connection between the education system and the world of work, the role and effectiveness of vocational education and training, and the quality of career guidance services to strengthen the long-term employment prospects of youth. This chapter looks at the different aspects of the Korean social welfare and activation system, with a particular focus on the wide range of measures that the Korean government has put in place in recent years. The chapter also discusses how to reshape labour market policy and institutions to facilitate access to rewarding employment and tackle social exclusion.

Box 3.1. Key elements of the OECD Action Plan for Youth

Tackle youth unemployment

Tackle weak aggregate demand and boost job creation.

Provide adequate income support to unemployed youth until labour market conditions improve but subject to strict mutual obligations in terms of active job search and engagement in measures to improve job readiness and employability.

Maintain and where possible expand cost-effective active labour market measures including counselling, job-search assistance and entrepreneurship programmes, and provide more intensive assistance for the more disadvantaged youth, such as the low-skilled and those with a migrant background.

Tackle demand-side barriers to the employment of low-skilled youth, such as high labour costs.

Encourage employers to continue or expand quality apprenticeship and internship programmes, including through additional financial incentives if necessary.

Strengthen the long-term employment prospects of youth

Strengthen the education system and prepare all young people for the world of work

Tackle and reduce school dropout and provide second-chance opportunities for those who have not completed upper secondary education level or equivalent.

Ensure that all youth achieve a good level of foundation and transversal skills.

Equip all young people with skills that are relevant for the labour market.

Strengthen the role and effectiveness of Vocational Education and Training (VET)

Ensure that vocational education and training programmes provide a good level of foundation skills and provide additional assistance where necessary.

Ensure that VET programmes are more responsive to the needs of the labour market and provide young people with skills for which there are jobs.

Ensure that VET programmes have strong elements of work-based learning, adopt blends of work-based and classroom learning that provide the most effective environments for learning relevant skills and enhance the quality of apprenticeships, where necessary.

Ensure that the social partners are actively involved in developing VET programmes that are not only relevant to current labour market requirements but also promote broader employability skills.

Assist the transition to the world of work

Provide appropriate work experience opportunities for all young people before they leave education.

Provide good quality career guidance services, backed up with high quality information about careers and labour market prospects, to help young people make better career choices.

Obtain the commitment of the social partners to support the effective transition of youth into work, including through the development of career pathways in specific sectors and occupations.

Reshape labour market policy and institutions to facilitate access to employment and tackle social exclusion

Ensure more equal treatment in employment protection of permanent and temporary workers, and provide for reasonably long trial periods to enable employers to give youth who lack work experience a chance to prove themselves and encourage transition to regular employment.

Combat informal employment through a comprehensive approach.

For the most disadvantaged youth, intensive programmes may be required with a strong focus on remedial education, work experience and adult mentoring.

Source: OECD (2013[6]), The OECD Action Plan for Youth: Giving Youth a Better Start in the Labour Market, Meeting of the OECD Council at Ministerial Level, 29-30 May 2013, Paris. http://www.oecd.org/employment/Action-plan-youth.pdf

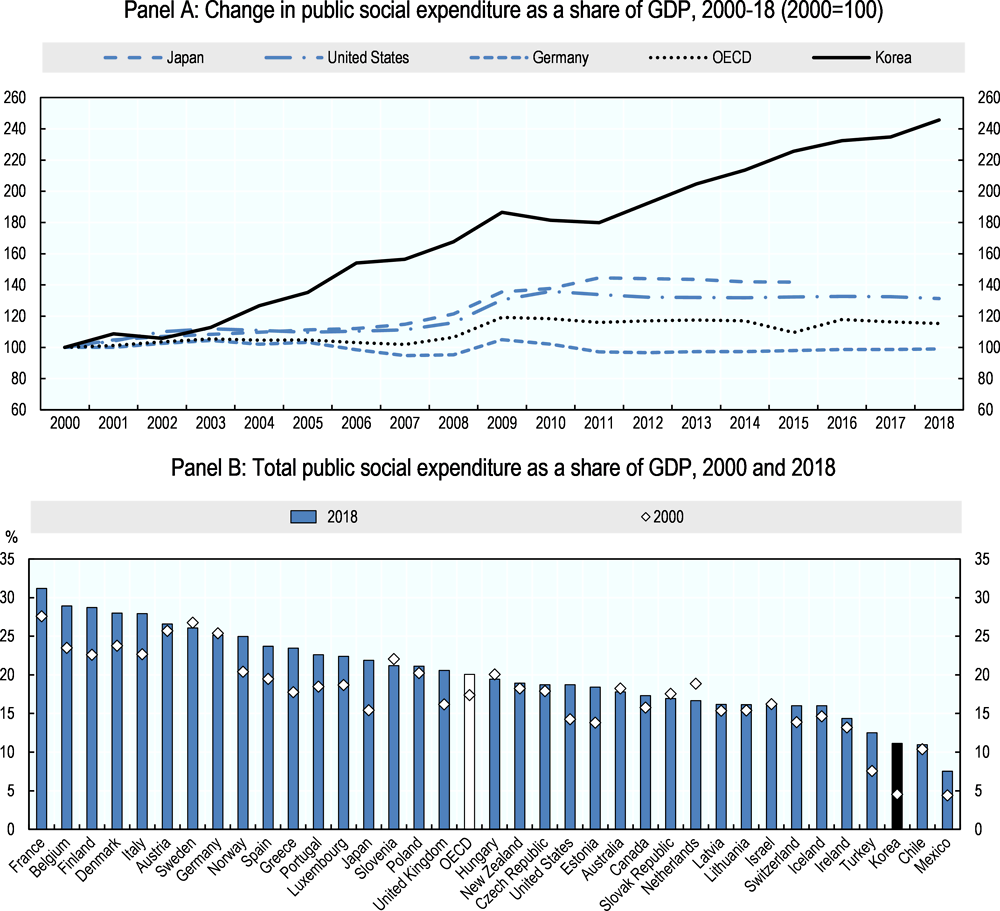

3.2.2. Small but growing welfare system

Korea has been continuously expanding public social spending over the last decades, more than doubling the share of GDP it devotes to social spending since 2000 (Figure 3.4, Panel A). The increase in Korean social expenditure outpaced that of most OECD countries and is mainly driven by pension benefits and health care services (OECD, 2018[7]). Even so, gross public social spending remains third lowest in the OECD ranking, leaving only Chile and Mexico behind (Figure 3.4, Panel B). In 2018, the Korean government spent only 11.1% of GDP on a range of social programmes related to pensions, health, income support for the working-age population, active labour market policies and other social services. The average across OECD countries stood at 20.1% in the same year.

Korea’s safety net for the working-age, as in many OECD countries, includes both social insurance and means-tested social assistance programmes for the very poor. Earnings-related unemployment benefits under the Employment Insurance system are available for a limited time for jobseekers with a sufficient contribution record. People in low-income households, including those who are not (or no longer) entitled to unemployment benefits, can apply for public assistance under the Basic Living Standard Programme.

Figure 3.4. Public social expenditure has been risen quickly in Korea over the past two decades, but remains low compared with other OECD countries

Note: For some countries, the second reference year is not 2018 but the latest available year: 2015 for Japan; 2016 for Australia, Mexico and Turkey; and 2017 for Canada, Chile and Israel.

Source: OECD (2016), Social Expenditure Database (SOCX), www.oecd.org/social/expenditure.htm.

To support young adults, the Government announced in March 2018 an ambitious plan with a wide range of youth support measures (see Box 3.2 for more details). Many measures are an extension of existing ones, but there are also important new initiatives. The plan represents an important shift from indirect measures, such as subsidies for firms that hire young people, towards a stronger focus on measures that directly benefit youth, such as tax exemptions and in-work benefits.

According to government estimates, the different support measures should bring the real earnings of young people employed by SMEs closer to those working for large enterprises, hereby lowering the implications of labour market duality. However, take-up of the different programmes remains low and reaching out to eligible youth needs to be strengthen (see Section 3.2.4 below). In addition, it is important to ensure that employment support for youth does not come at the expense of older workers – such as, increased hiring of youth in the public sector thanks to early retirement of older workers – since older workers face significant employment difficulties as well (OECD, 2018[8]). Several of the measures will be further discussed in the subsequent sections.

Box 3.2. Youth employment measures announced in 2018

In March 2018, the Korean Government unveiled an ambitious youth action plan with a wide range of economic, employment and social policy measures. The most important measures to improve youth employment and tackle youth poverty include the following:

Expanding support for young employees and their employers

1. Support for new employment

a. Increase in the subsidy for newly hired regular employees from KRW 20 million to KRW 30 million (about one-third of the minimum wage) over a period of three years and an extension of the coverage to include not only SMEs but also high-potential enterprises. For firms with less than 30 employees, the subsidy starts from the first newly hired employee; for firms with 30-100 employees from the second newly hired employee; and for firms with more than 100 employees from the third newly hired employee. In 2017, barely 300 youth benefited from the measures, while there were already 86 000 beneficiaries by October 2018.

b. Increase in the income tax exemption rate for young SME employees from 70 to 100%; an increase in the age limit from 29 to 34 years; and an increase in the duration from three to five years.

c. Expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit, which provides in-work support for both salaried and non-salaried workers who earn a low income, to single youth households aged under 30 (see Section 3.2.4).

d. Expansion of the certification of youth-friendly business to attract youth to promising SMEs and high potential enterprises.

2. Reduction of housing and transportation expenses

a. Extension of the low-interest loan (at 1.2%) of up to KRW 35 million for four years for a housing deposit of KRW 50 million or less to young people aged 34 or below with an annual income of KRW 35 million and working in an SME with less than 50 employees (see Section 3.2.5).

b. Introduction of transportation cards worth KRW 100 thousand per month for young people working for SMEs located in industrial complexes with poor transportation access to cover for transport cost (including buses, subways and taxi). By October 2018, there were 154 000 beneficiaries.

3. Expansion of mutual-aid savings programme for youth

a. Newly hired SME employees who stay at least three years with the same company can accumulate KRW 30 million: own savings worth KRW 600 thousand per year + employer contribution of KRW 600 thousand (subsidised by the Employment Insurance Fund) + government contribution of KRW 1 800 thousand per year. Existing young employees need to stay for five years with the company to accumulate the same savings amount. The number of beneficiaries rose from 5 200 in 2016 to 188 700 in October 2018.

4. Employment in large enterprises and public institutions

a. A large enterprise can benefit from an extended tax exemption period for every young person it hires.

b. Increase in employment in public institutions by 5 000 persons or more through an expansion of the autonomous recruitment quota and facilitation of honorary retirement. People who formerly worked for SMEs receive preferential treatment when applying for public institutions related to SMEs.

c. Introduction of a mandatory youth recruitment quota (3% of total hirings) in local governments on a pilot basis.

5. Employment opportunity for soldiers

a. Provision of employment-linked training programme and employment support after discharge, if they decide to stay in the same region.

Promotion of business start-ups

6. Funding and administrative support for innovative start-ups

7. Tax exemptions for new start-ups for a period of five years

8. Preferential treatment for start-ups

9. Incentives for large enterprises to support start-up/venture companies

Establishment of new youth centre

10. Launch of an online youth centre to guide youth through the available youth measures

11. Creation of 17 youth hub centres in collaboration with public employment centres and other place frequented by the youth population.

Source: Government of Korea (2018[9]), Youth Employment Measures, 2018.3.15.

3.2.3. Social safety net for young people

Employment Insurance is not very generous, except for low-wage youth

Unemployment benefits under the Employment Insurance system include job-seeking allowances and early re-employment allowances. Beneficiaries receive 50% of their previous average gross wage, with the minimum benefit set at 90% of the minimum wage and the maximum benefit currently fixed at KRW 50 000 per day. Those who manage to find a job quickly receive 50% of the remaining benefit as a bonus for being re-employed quickly. While the job-seeking allowance is meant to be an earnings related benefit, it has turned into a flat-rate benefit due to the yearly increases in the minimum wage. In 2018, the daily minimum benefit (KRW 47 213 in 2018) nearly reached the daily maximum benefit.

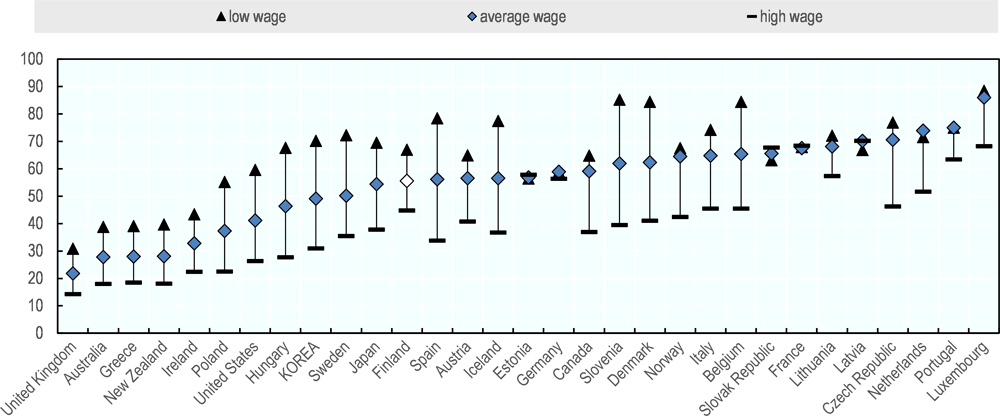

The net replacement rate for unemployed people – i.e. the ratio of net income out of work to net income while in work, taking into account cash income, social assistance and housing benefits, as well as income taxes and mandatory social security contributions – ranges in Korea from 31% for those with high previous earnings to 70% for jobseekers with low previous earnings (Figure 3.5). These net replacement rates put Korea in the lower third of the OECD ranking for average and high-wage earners and in the upper third of for low-wage earners. It should be noted that about 40% of employees in Korea aged 18-34 were low-wage earners in 2017 (defined as those earning 67% of the average wage or less), based on the Economically Active Population Survey.

Figure 3.5. Employment Insurance is not very generous, except for low-wage youth

Note: The net replacement rate is the ratio of net income out of work to net income while in work. Calculations consider cash income as well as income taxes and mandatory social security contributions paid by employees. Social assistance, housing-related benefits and family benefits are included, while entitlements to severance payments are excluded. Net replacement rates are calculated for a 24-year-old worker with an uninterrupted employment record of 24 months who has been unemployed for one month. The net-replacement rates are calculated for youth with a previous earning level equal to 67%, 100% and 167% of average full-time wages.

Source: Author's own calculations using output from the OECD tax-benefit web calculator, https://taxben.oecd.org/.

One in three young workers are not covered by Employment Insurance

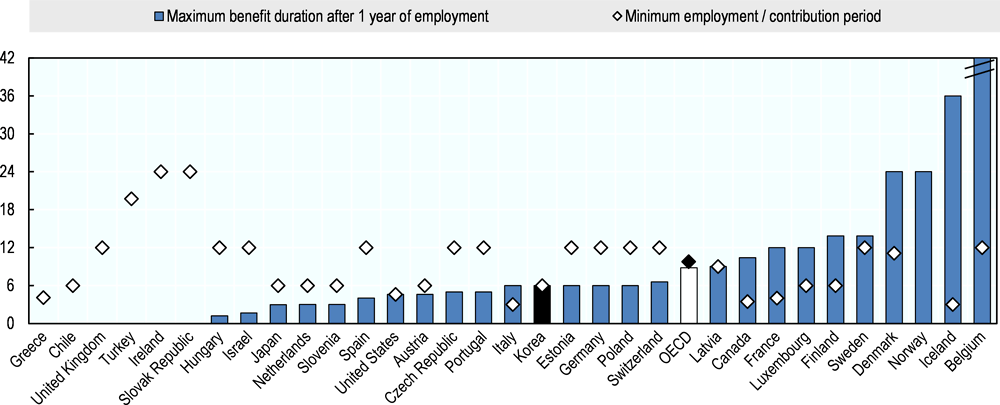

Young jobseekers are eligible for Employment Insurance, on the condition that they have been contributing for at least 180 days of during the last 18 months, are registered at an employment security office, and capable of and available for work. Unemployment must not be due to voluntary leaving, misconduct, a labour dispute, or the refusal of a suitable job offer. The minimum contribution period of 6 months is less strict than the OECD average of 9.7 months, but comparable with a group of seven other OECD countries, including Finland, Japan and the Netherlands (Figure 3.6).

The duration of benefit payments increases with age and the length of the insurance record. Youth insured for less than one year qualify for 90 days of benefits, while those who are insured for one or more years receive benefits for maximum 180 days (if aged less than 30) or 210 days (if aged 30-49). When considering a 24 year-old jobseeker who has been working and contributing for one year, Korea stands in the middle of the OECD ranking for unemployment benefit durations, next to Italy and Germany (Figure 3.6).

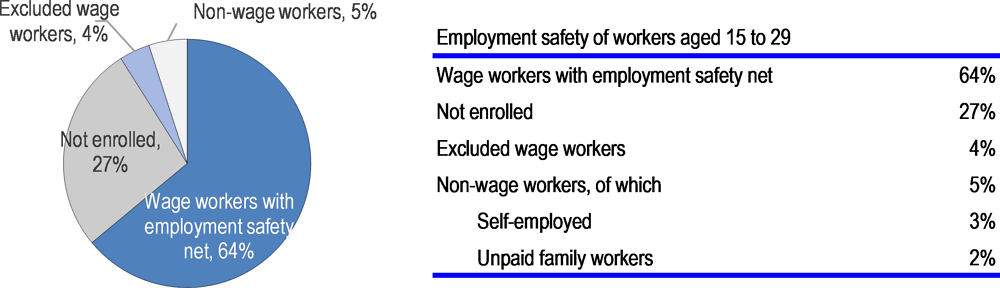

While the Employment Insurance scheme includes most salaried workers on a mandatory basis, the coverage among youth remains low in reality. According to data from the Economically Active Population Survey, more than one out of three 15-29 year-old workers did not have access to an unemployment safety net in 2017 (Figure 3.7). About 9% of young workers were excluded from the scheme by definition, like self-employed and unpaid family workers, but about 27% of 15-29 year-old workers should have been enrolled and they were not. Many of them are working in very small businesses with less than five employees.

Figure 3.6. The minimum contribution period for unemployment benefits is rather short in Korea, while the maximum benefit duration ranks in the middle among OECD countries

Note: In Greece, Ireland, the Slovak Republic, Turkey, and the United Kingdom, 24-year-olds with a contribution record of one year do not qualify for unemployment insurance benefits. There is no maximum benefit duration in Belgium. Norway has no minimum contribution period but a minimum earnings requirement. No maximum benefit duration applies in Chile. Results for the United States are for the State of Michigan. No results are available for Mexico. There are no unemployment insurance schemes in Australia and New Zealand.

Source: Compiled using "Benefits and Wages: Country Specific Information” on www.oecd.org/els/soc/benefits-and-wages-country-specific-information.htm.

To improve access to unemployment insurance among young workers, better enforcement of the legislation is crucial. Several strategies to strengthen compliance are proposed in the recently published OECD report Connecting People with Jobs: Towards Better Social and Employment Security in Korea (OECD, 2018[7]), including: 1) an expansion of the resources of the relevant monitoring authorities to observe and sanction offending employers; 2) an increase in the penalties as they are currently too low to be considered a real deterrent; and 3) a promotion and rigorous application of the arbitration procedure through which non-insured workers can claim Employment Insurance entitlements.

Korea may also want to expand eligibility for Employment Insurance to voluntary job leavers, to support young workers who are stuck in low-quality jobs and who need time and assistance to find a better job. The full exclusion of voluntary job leavers in Korea is rather strict compared with many other OECD countries. Many countries apply suspensions (i.e. delay of the start of benefit payment) or a sanction period (i.e. fixed-term waiting period subtracted from the overall entitlement period) (Table 3.1). Such penalties are usually justified because they discourage workers from leaving their job in favour of benefits, to combat misuse of the system. In practice, disqualification may force young people to stay in low-quality jobs out of necessity. Korea could consider a suspension or sanction period for voluntary job leavers rather than full disqualification. Most OECD countries see benefit sanctions or suspensions of a certain period as a viable enough solution for encouraging job mobility while ensuring income and employment support for those who may need it.

Figure 3.7. More than one in three young workers are not covered by Employment Insurance

Source: Supplementary results of the Economically Active Population Survey by employment type, Statistics Korea.

Table 3.1. Penalties for voluntary unemployment differ among OECD countries

Penalties issued for voluntary unemployment in OECD countries, 2014

|

No impact |

Suspension |

Sanction |

Disqualification |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Hungary |

Austria |

Australia |

Canada |

|

Slovak Republic |

Denmark |

Belgium |

Chile |

|

Germany |

Czech Republic |

Estonia |

|

|

Latvia |

Finland |

Greece |

|

|

Suspension |

France |

Italy |

|

|

Poland |

Iceland |

Korea |

|

|

Switzerland |

Ireland |

Luxembourg |

|

|

Sweden |

Israel |

Mexico |

|

|

Japan |

Netherlands |

||

|

New Zealand |

Portugal |

||

|

United Kingdom |

Slovenia |

||

|

Spain |

|||

|

Turkey |

|||

|

United States |

Source: Adapted from Langenbucher, K. (2015), “How demanding are eligibility criteria for unemployment benefits, quantitative indicators for OECD and EU countries”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 166, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jrxtk1zw8f2-en

In addition, incorporating non-standards forms of employment in the Employment Insurance scheme could narrow the scope for companies to opt for contractual arrangements that evade social contributions, such as contract workers or home workers, who are typically doing the same work as employed workers do, but without access to Employment Insurance. Several OECD countries have taken steps to extend social protection coverage to non-standards workers. For instance, Austria gradually integrated independent contractors, a hybrid between self-employment and dependent employment, into the general social protection system, whereas Italy gradually increased their social security contributions (see Box 3.3 for further details).

Box 3.3. Ensuring social protection for non-standard workers

In Austria, independent contractors control their own working time and workflow but are contracted for their time and effort. Concerns that employers might use this form of employment to evade the compulsory social protection system drove their gradual integration into the social security system. Since 2008, independent contractors are liable for the same (employer and employee) social security contributions as standard employees. While their number had been steadily growing until early 2007, it began to fall following the reform’s announcement and was at its all-time low in 2016.

In Italy, para-subordinate workers are self-employed, but highly dependent on one or very few clients. They used to pay lower pension contribution rates and were not covered for unemployment or sickness benefits. In response to their growing numbers, Italy gradually increased their social security contribution rates (and thus welfare guarantees) until they reached the contribution rate of employees. As a result, the number of para-subordinate workers nearly halved between 2007 and 2016. The government also introduced other measures to reduce the attractiveness of para-subordinate arrangements, including a tightening of the para-subordinate regulation (2012) and the abolition of certain types of para-subordinate arrangements (2015). Measures to persuade employers to hire workers on permanent contracts – such as a significant reduction in employer social security contributions for new hires through the 2015 Jobs Act – further contributed to the decline in para-subordinate contracts.

Source: OECD (2018[10]), The Future of Social Protection: What Works for Non-Standard Workers?, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264306943-en

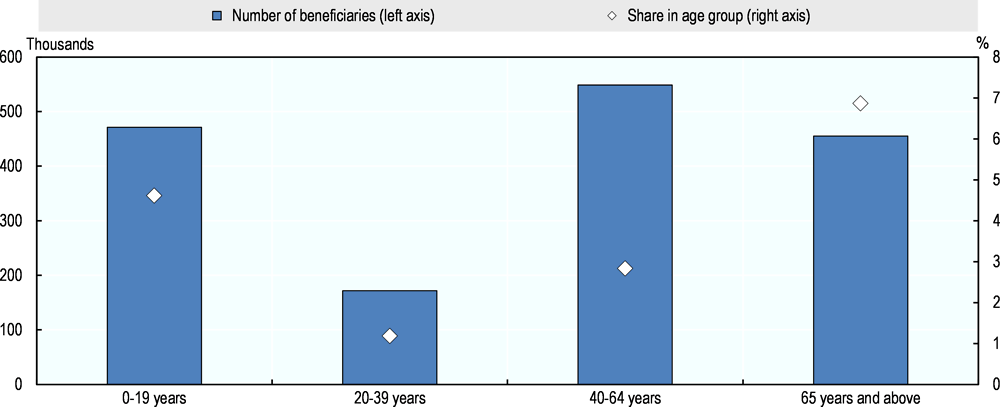

Support provided by social assistance is very restricted

The Basic Livelihood Security Programme (BLSP) is a comprehensive means-tested social assistance programme in Korea, providing various cash benefits to eligible persons living in absolute poverty (including a living benefit, housing benefit, medical benefit, education benefit, child-birth benefit, funeral benefit and self-support benefit). However, strict income requirements and family support obligations keep the caseload of the Basic Livelihood Security Programme very low. In particular, the family requirement implies that applicants cannot receive benefits if they have a close family member (child, spouse or parent) capable of supporting them. Yet, eligibility does not depend on whether such family support is actually provided. Both assets and income are taken into account to measure the capacity of family support. As a result, barely 1% of the age group 20-39 benefited from the programme in 2015 (Figure 3.8). The coverage is higher for other age groups, but remains very limited overall.

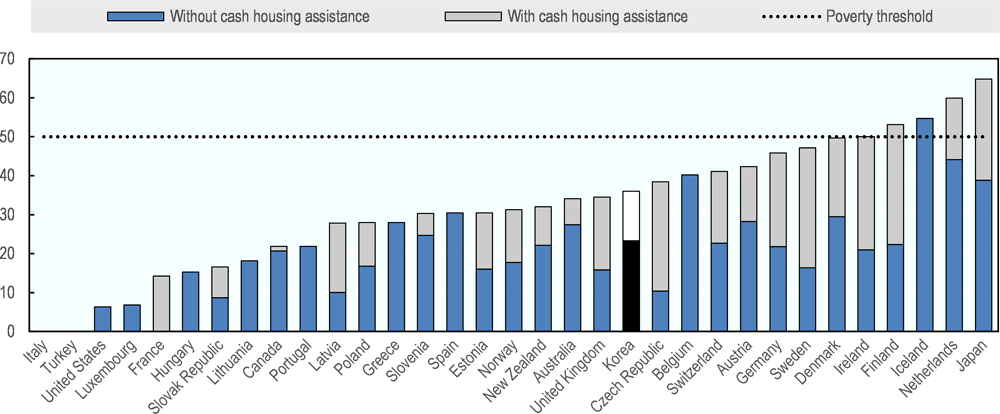

In addition, youth who have to rely on the Basic Livelihood Security Programme find their income considerably below the poverty threshold (defined as 50% of median household income). Taking cash housing benefit entitlements into account, their maximum disposable income reaches about 36% of median household income. Even so, this outcome is not very different from many other countries as shown by the 2018 estimates based on the OECD tax and benefit model, where Korea ranks in the upper half among OECD countries for benefit generosity for single persons (Figure 3.9).

Figure 3.8. Very few young adults receive public assistance

Source: Data provided by the Ministry of Health and Welfare; UN Data, UNSD Demographic Statistics (http://data.un.org).

Figure 3.9. Social assistance benefits are comparable with OECD countries, but leave youth in poverty

Note: Median net household incomes are based on the Income Distribution Database, expressed in current prices and are before housing costs (or other forms of “committed” expenditure). Results are shown on an equivalised basis and account for social assistance, family benefits and housing-related cash support, net of any income taxes and social contributions. US results include the value of Food Stamps, a near-cash benefit. Where benefit rules are not determined on a national level but vary by region or municipality, results refer to a “typical” case (e.g. Michigan in the United States, the capital in some other countries). In countries where housing benefits depend on actual housing expenditure, the calculation represents cash benefits for someone in privately-rented accommodation with rent plus charges equal to 20% of the average gross full-time wage.

Source: Author's own calculations using output from the OECD tax-benefit web calculator, https://taxben.oecd.org/.

A better social safety net for young adults is needed

Overall, the Korean social security system provides rather limited protection to youth without a job. For many young adults, unemployment entails no entitlement to income support. Under such circumstances, they are compelled to accept any available job as quickly as possible, which contributes to the enduring existence of poor-quality jobs and the persistent fragmentation of the labour market.

The 2018 youth action plan of the Korean government (presented in Box 3.2) mainly focuses on measures for employed youth, but includes little for those young people who are unemployed. To improve the social safety net for youth, Korea could in the first place expand the coverage of Employment Insurance to voluntary job leavers and non-standard workers and should better enforce Employment Insurance regulations. In addition, there is a need to ease access to the Basic Livelihood Security Programme through the abolishment of the family support obligation. While the government excludes since 2019 the family support obligation for the living benefit and health benefit to the households of the lower 70% of the income distribution with household members aged 65 or above or a severely disabled person, the government could go further and phase out completely the family support obligation. Abolishing this rule would bring Korea more in line with other OECD countries in terms of social assistance coverage (OECD, 2018[7]).

3.2.4. Effective employment support but with narrow reach

Customised activation support needs to be further expanded

The government introduced the Employment Success Package Programme in 2009 to provide customised job-search support for jobseekers as well as training to improve their employability. Various flat-rate allowances are offered as a motivation to participate in the programme and as a reward for having found a job. While public employment centres serve low-income and disadvantaged groups, private providers are subcontracted for youth.

The activation strategy of this programme is in line with best practices in OECD countries and includes frequent face-to-face counselling, customised interventions, strong user involvement and a strong degree of flexibility in the type and timing of interventions. The programme also has a good balance of incentives and requirements for participants.

Because of these strong features, nearly all participants complete the programme and the majority finds a job – 86.8% in the youth group (Table 3.2). Most jobs come with Employment Insurance coverage (89.9% for youth), even though only 53% of the young people who found a job through the programme earn more than 60% of the median income. While this share may seem low, the share of youth earning more than 60% of the median income in the total youth working population is not much higher, at 64% in 2017.

An in-depth evaluation by Lee et al. (2016[11]) shows that the positive employment outcomes of the Employment Success Package Programme are maintained in the long term. Three years down the road, the employment rate of young participants is considerably higher (67%) than that of non-participants (51%). Lee and co-authors also show how the effectiveness of the programme increased over time at a time when labour market conditions worsened for young people, suggesting that the quality of service provision has been improving.

Over a period of six years, the number of participants multiplied by thirty, from 10 000 in 2009 to 300 000 in 2015, as did the budget, reaching KRW 217 billion in 2015. Young jobseekers under 35 years accounted for about 45% of all participants in the programme (Table 3.2). However, they represent only one-fourth of the total number of unemployed youth in Korea (534 000 in 2015).

Table 3.2. The Employment Success Package Programme reaches high employment rates, but job quality is rather low

Participants in the Employment Success Package Programme, programme completion, post-programme employment and employment retention, Employment Insurance coverage and low-wage prevalence, 2015

|

Participants (units) |

Programme completion |

Post-participation employment rate |

Share of employed insured by EI |

3-month employment retention |

6-month employment retention |

Share of employed earning KRW 1.5 million or more |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Percentages |

|||||||

|

Young people |

133 472 |

99.0 |

86.8 |

89.9 |

79.2 |

64.3 |

53.0 |

|

Mature people |

24 599 |

99.1 |

82.1 |

85.8 |

79.1 |

64.5 |

43.3 |

|

Low-income people |

137 332 |

98.4 |

78.3 |

79.3 |

78.9 |

64.3 |

43.7 |

|

Total |

295 403 |

98.7 |

82.5 |

84.9 |

79.1 |

64.3 |

48.3 |

Source: Administrative data provided by the Ministry of Employment and Labor.

Better and more proactive outreach to non-participants is necessary to improve the reach of employment support. A similar conclusion of low take-up holds for many of the youth policy measures that are part of the 2018 youth action plan of the Korean government. The government is aware of the need to better promote youth measures and launched an online youth centre to guide youth through the available youth measures. They also announced the creation of 17 youth hub centres in collaboration with public employment centres and other places frequented by the youth population (see Box 3.2). These initiatives are in line with good practices in other OECD countries. Other options for reaching out to unregistered youth are presented in Box 3.4, which could provide inspiration for additional outreach measures.

Box 3.4. Policy options to reach out to unemployed and inactive youth

Youth outreach workers

Youth outreach workers meet, engage and build relationships with young people, often focussing on the hardest-to-reach. Their aim is to help them find solutions to practical problems and barriers to labour market integration and create pathways to employment. Austria, Belgium, Ireland, Finland, Sweden and the United Kingdom all work with youth outreach workers.

One-stop shops

One-stop shops or single-point services bring together a range of services into one place. They tend to be located in community settings and make it easier for youth to navigate the system instead of having to deal with a myriad of different services, each with their own paperwork requirements. Denmark, Germany and Finland have set up such one-stop shops for youth.

Mobile employment services for youth

Mobile employment services, like in Estonia and Germany, can move there where those in need of services are located, such as young people in rural areas. They also make it easier to reach many people at once, i.e. at job fairs or in universities. However, since they can be costly in terms of travel and staff time, employment services should make sure they reach a critical mass needed to justify the service. Partnerships with local actors with up-to-date local information are therefore crucial.

Proactive collaboration between the education sector and employment services

Employment services can support schools and universities to give career advice, raise young people’s awareness of available employment services, and spot at-risk youth early. When limited staff resources prevent employment services from working with individual institutions, they can co-develop curricula and other support material for career counsellors, develop an inter-institutional tracking and reporting system to identify students at risk of drop-out, or provide information about apprenticeships or internships. Norway and Japan offer good examples for such collaboration.

Use of internet and social media

Social networks can provide an accessible and powerful toolkit for employment services to promote and highlight services that affect all young people, especially unemployed and inactive youth. Digital services can be quickly updated, tailored for young people in terms of content and language and they can be a cost-effective way to reach large numbers of young people for minimal cost. OECD countries that use social media for outreach are Belgium, Italy, Spain and Portugal.

Job fairs and other events

Job fairs offer employment services and their partners the opportunity to present what services are available and raise young people’s awareness of the services they are eligible for.

Collaboration with non-governmental actors

A number of countries, e.g. Australia, run active outreach strategies that draw on the services of non-governmental institutions. While public authorities may struggle to track disengaged youth, they may still go to the local youth centre or sports club. A tight network of non-governmental youth activity providers can therefore be helpful in preventing young people who do not regularly engage in education or work from disconnecting entirely.

Sources: OECD (2016[12]) and European Commission (2015[13]).

The main challenge of the Employment Success Package programme is maintaining the high quality of its services while expanding its capacity. The private employment service market, the main provider of employment services for youth in the Employment Success Package Programme, is still developing. Agencies tend to be very small and low-performing providers can relatively easily remain in the market. According to Kil (2017[14]), the average staff number of job placement service providers was only 2.8 persons in 2015 and only 12% of them had five employees or more. OECD (2018[7]) reports that only 11 out of 333 private agencies lost their contract in 2017. Because of relatively low wages, there is also a high turnover among counsellors in private agencies.

Further adjustments to the quality assurance framework may be needed to ensure better service provision. Like in Australia, Korea has an elaborated rating system that evaluates the performance of private agencies, with a strong focus on sustainable employment outcomes. Even so, there seems to be considerable room for a stricter quality assessment and contract termination for poorly performing service providers. The performance of private providers could also be published online to guide jobseekers to the best-performing providers. For instance, Australia measures private providers’ relative performance on a continuous basis and publishes the Star Ratings online on quarterly basis. They serve as an important reference for jobseekers when choosing a provider. Possibly, proactive outreach could also become an element in the performance evaluation of private employment services to give them incentives to develop outreach strategies and actively search for unemployed and inactive youth.

To encourage private providers to develop more specialised competencies and expand their services, it will be necessary to offer contracts lasting longer than the current one-year timeframe. Australia and the United Kingdom, the two OECD countries that have gone furthest in subcontracting and privatising its employment services, also gradually extended the duration of service contracts to assure longer-term investments by providers. Australia now offers contracts for six years, instead of the initial three-year period.

In-work benefits are now available for youth

As in several OECD countries, Korea has an income tax credit scheme in place to top-up the earnings of low-income workers and address in-work poverty. This type of schemes has a major advantage over more traditional social transfers: they do not only redistribute resources to low-income families, they also make employment more attractive for workers with low earnings potentials, since the credit is conditional on having a job.

The Earned Income Tax Credit in Korea provides in-work support for both salaried and non-salaried workers who earn a low income. The credit was introduced in 2008 to support low-income workers and their families and was step-wise expanded to include additional population groups. Since the beginning of 2019, young people under age 30 are also eligible and estimations suggest that 157 000 young people will be able to benefit from the tax credit, accounting for 4.3% of all employed 20-to-29 year olds. In total, 1.9 million households benefited from the Earned Income Tax Credit in 2017, of which two-thirds are headed by a person aged 50 or more (OECD, 2018[8]).

A recent tax reform increased the maximum tax credit for single-person households from KRW 0.85 million to KRW 1.5 million and from KRW 2.5 million to KRW 3 million for double-income households. As a result, the Korean tax credit is among the more generous systems in the OECD, similar to France and Finland (Table 3.3). In regard to the wage level at which in-work benefits are phased out, Korea ranks in the middle of OECD countries.

Table 3.3. Korea has rather generous in-work benefits

Maximum benefit amounts and phase-out levels for in-work benefits for single persons without children, as a percentage of average wages, 2018

|

Maximum benefit |

Benefit phased out at |

|

|---|---|---|

|

United Kingdom |

7.9 |

37 |

|

Sweden |

6.7 |

373 |

|

France |

4.3 |

- |

|

Korea |

4.2 |

59 |

|

Finland |

3.7 |

306 |

|

Canada |

1.6 |

25 |

|

United States |

0.9 |

25 |

|

New Zealand |

0.8 |

80 |

|

Chile |

0.3 |

71 |

Note: Data refer to 2019 for Korea and to 2018 for the other countries. Average wages of 2017 are used to calculate the percentages. Other OECD countries have no in-work benefits at all or young people without children are not eligible.

Source: Author's own calculations using output from the OECD tax-benefit country profiles provided at http://www.oecd.org/social/benefits-and-wages/.

Given the rapid expansion of the system, it will be important to evaluate the effectiveness of the system, in particular with respect to the impact on labour supply as well as the take-up among eligible (young) people. Evaluation studies are rare but overall suggest a positive impact on labour supply, especially among the lowest-income households at the phase-in range of the tax benefit (Shin and Song, 2018[15]). There is also a risk that in-work benefits incentivise employers to offer lower wages as employees are effectively subsidised by taxpayers. While the strong increase in the minimum wage recently acts as a decent wage floor, it may be worth to evaluate the overall impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on employment and in-work poverty.

3.2.5. Housing support targeted at youth

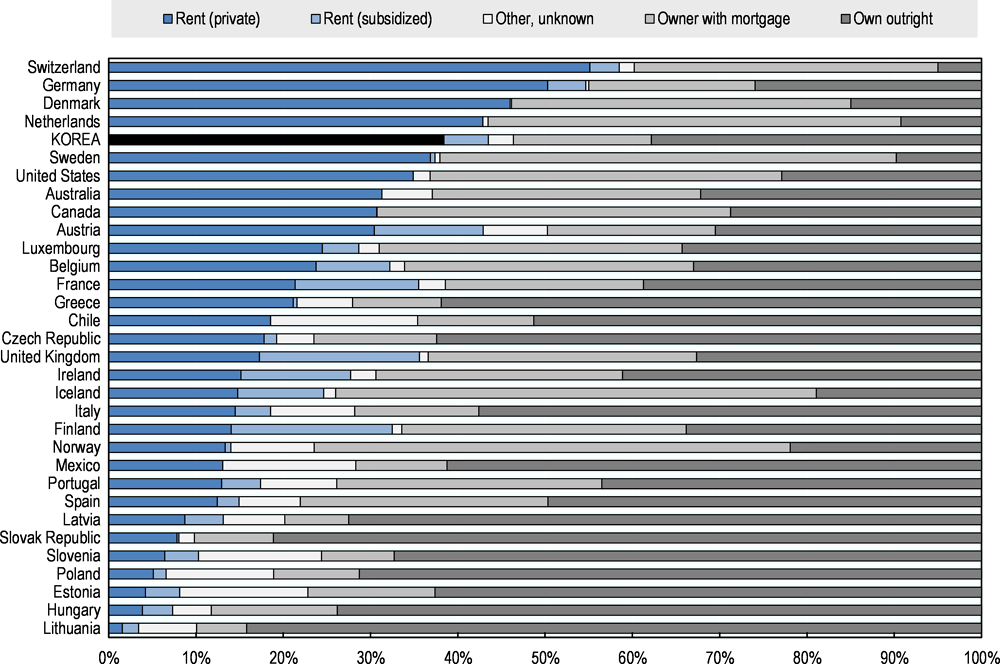

Korea has relatively good housing outcomes in an international context. Housing prices in Korea have been rather stable in the last few years, rising at less than 1% annually since 2013 (adjusted for inflation), in contrast to sizeable increases elsewhere in the OECD area, including the United States and the Euro area (OECD, 2018[16]). There is a perception that housing prices are too high relative to income, but housing in Korea does not seem less affordable than in most other countries: the house price-income ratio is comparable with many OECD countries (Kim and Park, 2016[17]), and Seoul is not among the most expensive metropolitan cities in the world (Demographia, 2015[18]). Final housing expenditure in Korea (18.3%) is also amongst the lowest in the OECD area (with an average of 22%) (OECD, 2018[19]).

Nevertheless, to support young adults in an economic climate with increasing employment insecurity and instability, the Korean government recently expanded the target groups for its housing policies to include young people (Seo and Joo, 2018[20]). As in other OECD countries, housing policy in Korea comprises a wide and complex mix of programmes, including homeownership subsidies, housing allowances, social rental housing and rental support and regulation. Housing policy remains largely in the hand of the national government, but local governments are becoming creative suppliers of public housing that is more customized to the local context (Seo and Joo, 2018[20]). The most important policies directed at the young generation include subsidised public housing (Happy Housing) and rental support for the private market.

The programme “Happy Housing” was initiated in 2013 and aims to enhance housing welfare for the young adult generation, whom tend to be excluded from public assistance because they are young, do not have dependent family members to support, and are capable of engaging in economic activities and providing for themselves. The reasoning behind the policy is that high housing prices and rental burdens in urban areas make it difficult for young people to get married and move up to the next life stage, hereby aggravating the country’s social challenges of low fertility and ageing population. By giving young adults the opportunity to temporarily reside in public rental housing with low rental costs, the government hopes that they can accumulate assets to move upward to a better housing situation at a later stage. The Happy Housing programme targets single college students, single workers who started working within the past five years, and couples who married within the past five years. The lease period is set at six years, but can be extended up to ten years if single occupants get married or newlyweds bear two children (Seo and Joo, 2018[20]). The 2017 Housing Welfare Roadmap foresees 300 000 rooms for young people and 200 000 units for newly-weds.

In addition to public rental housing, the government also supports the young generation in the private rental market, which is one of the largest in the OECD area, with 38.4% of the households renting in the private market, compared with 21.5% in the OECD on average (Figure 3.10). The Korean private rental market is complex, with three co-existing systems: jeonsei rental contracts, monthly rentals with deposit, and monthly rentals without deposit. For many years, the dominant rental lease in the housing market was jeonsei, an asset-based lease (see Box 3.5 for a description). Evidence from the 2012 Korea Housing Survey revealed that, among households headed by 20-to-34 year olds renting in the private market, 47.0% of all contracts were jeonsei contracts, 45.5% monthly rentals with deposits, and 7.5% monthly rentals without deposit (Lee, 2015[21]).

Figure 3.10. Most people in Korea rent on the private market

Note: Tenants renting at subsidized rent are lumped together with tenants renting at private rent in Australia, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Mexico, the Netherlands and the United States, and are not capturing the full extent of coverage in Sweden due to data limitations. Data for Canada refer to 2011 and for Chile to 2013.

Source: OECD Affordable Housing Database, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

Box 3.5. Jeonsei rental contract system

The jeonsei (or chonsei) rental system is unique to Korea, where a tenant pays, instead of monthly rent, a lump sum deposit (equivalent to 40−60% of the house price), which is fully returned when the contract is terminated. This rental system worked largely because, amid high economic growth and interest rates, landlords were able to earn more from the interest coming from the deposit than from the monthly rent. Landlords also favoured jeonsei because it spared them from the cumbersome rent collection and possible risk of tenants defaulting on the rent payment since the lump sum deposit acts as a buffer. With the recent slowdown in economic growth and lower interest rates, many landlords have been converting their units from jeonsei rental to monthly rental.

With interest rates falling to record lows, jeonsei contracts have become economically unviable for landlords, who prefer monthly rentals contracts because of the larger cash flows. The lower offer of jeonsei contracts has led to a shortage of houses available on jeonsei contracts and a more than doubling of the required deposit amount between 2006 and 2016 (OECD, 2018[19]). As a result, the share of jeonsei in total rental lease contracts (for all age groups) dropped from 67% in 2011 to 56% in 2015 (Kim and Park, 2016[17]). To support young people to access jeonsei contracts, the government decided to offer low-interest loans (at 1.2%) of up to KRW 35 million for four years for a housing deposit of KRW 50 million or less to young people aged 34 or below with an annual income of KRW 35 million and working in an SME with less than 50 employees (see Box 3.2).

However, given the high jeonsei amounts and the lack of interest of landlords in the jeonsei system, the question is whether such support is the best strategy to help young people in the housing market. With an average jeonsei deposit in Seoul metropolitan area of KRW 150 million in 2016 (OECD, 2018[19]), the low-interest loans offered by the government are not really an interesting offer for young people as they are restricted to housing deposits of KRW 50 million or less. Since the jeonsei system is no longer a viable option for landlords, it might be more realistic to allow the rental market to move away from the jeonsei system to a system of monthly rentals with deposit as in most other OECD countries. The government could then support young people through other means, such as housing allowances and rental market regulation.

For instance, Korea could introduce a scheme of temporary housing allowances for young people to facilitate their climb up the housing ladder. Compared with social rental housing, housing allowances have fewer distortion effects on residential and labour mobility (Salvi del Pero et al., 2016[22]). They can also improve equity in access to the subsidy for eligible households, if designed as entitlements, as they are more easily withdrawn from households above eligibility limits without necessarily imposing relocation to the receiving household. However, the implementation of housing allowances should be done carefully, as they might be captured by higher rental prices. The phasing out of housing allowances, and their interaction with taxes, should also be monitored carefully, to avoid benefit traps when increasing working hours or moving into higher-paid employment.

In addition, Korea’s private rental market requires better regulation to protect private renters. The private rental market is largely operated by individual unregistered landlords (OECD, 2018[19]). In many OECD countries, government involvement in the private rental market includes rent regulation, tenancy protection, tax relief on paid rent for tenants and other aspects of tenancy law (Salvi del Pero et al., 2016[22]). Tenancy law and quality standard regulations are important to ensure access to good-quality housing through the private rental sector. Housing literacy education should also be provided for those entering the private rental market for the first time, to enhance their awareness of legal requirements on lease contracts, obligations and responsibility, and the rights of tenants and landlords, so that they can be prepared for unexpected situations.

Finally, inadequate access to housing loans has been a stumbling block preventing low and middle-income people from owning a home in Korea (OECD, 2018[19]). Rather than restricting or tightening credit access, Korea may wish to adopt safe and sustainable mortgage options for young people. These measures should be accompanied by carefully designed regulatory oversight and prudent banking regulations.

3.3. Addressing labour market duality

The previous sections focussed on the social welfare and activation policies that Korea has in place to support young people. To improve youth labour market outcomes in the medium and long term, structural barriers to youth entering productive and rewarding jobs must be addressed as well. The following two sections explore the role of employment protection legislation as well as the polarisation in the product market.

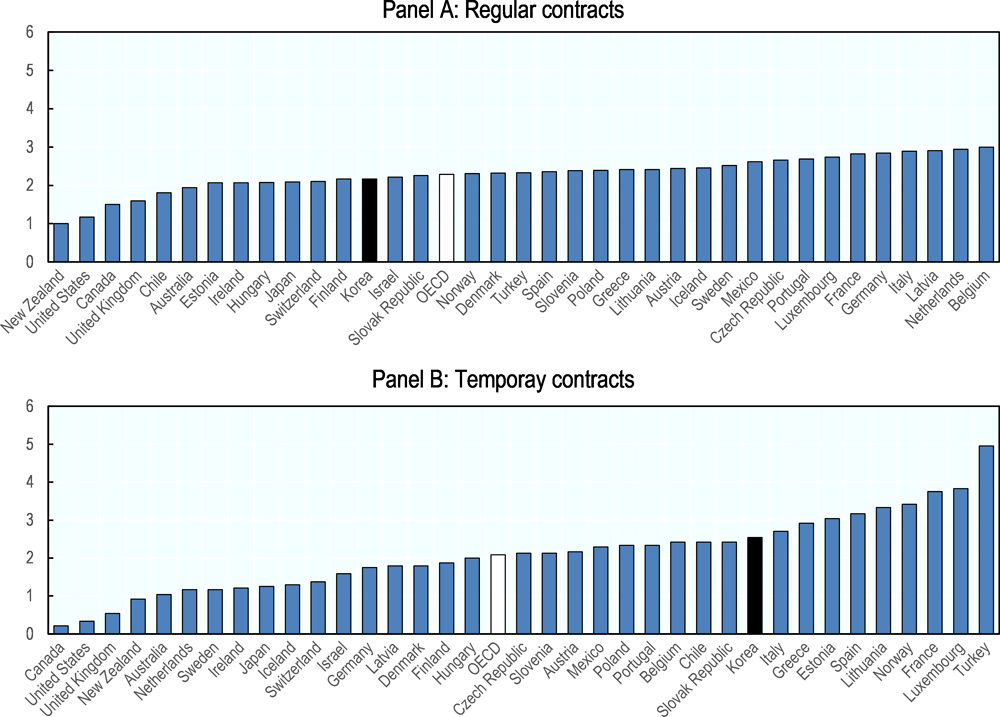

3.3.1. Balanced employment protection legislation

OECD research has shown that a balanced employment protection for permanent and temporary workers can enable employers to judge the vocational aptitudes and abilities of youth who lack work experience and encourage transition to regular employment (OECD, 2013[6]). In contrast, strict and uncertain procedures concerning the firing of permanent workers along with high severance payments tend to make employers reluctant to hire youth on an open-ended contract. When strict procedures for regular workers are combined with easy-to-use temporary contracts, employers tend to hire inexperienced young people mostly on temporary contracts. While short-term contractual arrangements often represent a stepping stone into more stable employment, there is a real risk that they may become traps when the gap in the degree of employment protection and non-wage costs between temporary and permanent contracts is wide (OECD, 2018[23]). Balancing the protection offered by different types of contracts tend to have positive effects for low-skilled or inexperienced workers, and youth are often among the main beneficiaries.

The Korean labour market used to be characterised by high levels of employment protection for regular workers and very restrictive rules for temporary work. In response to the Asian financial crisis of 1997, the government considerably liberalised both regular and temporary employment through a number of economic reforms (Ha and Lee, 2013[2]). While overall employment rates quickly recovered, the quality of employment deteriorated for an increasing number of non-regular workers and the labour market duality deepened (Cho and Keum, 2009[24]; Shin, 2013[25]).

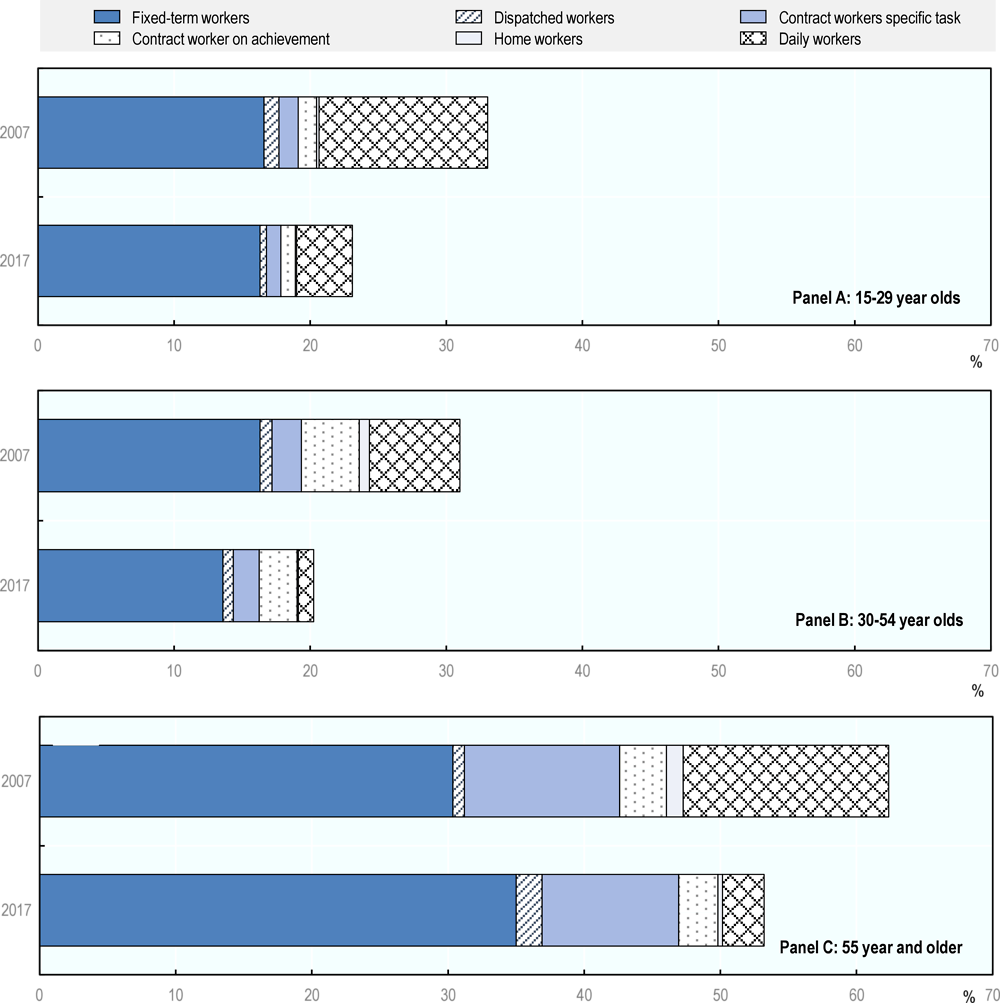

The Korean government has undertaken numerous reforms to address the resulting labour market duality. In particular, employment protection for the different types of non-regular workers has been improved by limiting the accumulation of fixed-term contracts and prohibiting discrimination (see OECD (2016[26]) for an overview). The OECD employment protection legislation index reveals that regulations for temporary employment in Korea are now stronger than in the average OECD country (Figure 3.11, Panel B), whereas the regulations for regular workers are less strict than the average OECD index (Figure 3.11, Panel A). For the latter group, Korean regulations tend to be relatively rigid for individual dismissals, while the regulations for mass dismissals are more flexible.

Overall, the reforms have been paying off and the incidence of temporary employment has been gradually decreasing. The decrease occurred across different types of contracts and age groups, including among the 15-to-29-year olds (Figure 3.12). Only among older workers, aged 55 and over, the share of both fixed-term workers and dispatched workers increased between 2007 and 2017, a topic that has been discussed at length in the report Working Better with Age: Korea (OECD, 2018[8]). The suggestions of the review to improve employment policies and employer practices towards older workers could also benefit younger workers, such as the proposal to restrict the scope for using lawful in-house subcontracting and the need to reduce the uncertainty surrounding dismissal costs.

3.3.2. Segmented product market

Large differences in employment conditions across Korean workers are not only related to employment regulations, but also the result of growing dispersion in the performance of firms and the employment conditions they are able to offer (Schauer, 2018[4]). Also other factors, such as insider-outsider dynamics (related to strong labour unions in large companies) and global trends of globalisation and technological progress, further contribute to labour market duality. The latter trends are not unique to Korea, but have a polarising effect on the labour markets in many OECD countries (OECD, 2019[27]).

Korea’s large business groups have played a key role in the country’s rapid economic development over the past half century and they remain leading players, with the top 30 groups accounting for about two-thirds of shipments in Korea’s manufacturing and mining sector and a quarter of sales in services. Despite their important contributions to Korea’s economic development, the powerful role of the large business groups and their presence in a wide range of business lines stifle the establishment and growth of SMEs and polarise the country economically and socially. Productivity in SMEs in manufacturing has fallen to less than one-third of that in large firms, resulting in wide wage dispersion between SMEs and large firms (OECD, 2018[16]). Low productivity and wage levels in SMEs discourage young people from accepting jobs at smaller companies, leading to fierce competition for jobs in large business groups and over-investment in tertiary education (see Chapter 2).

Figure 3.11. Korea has strong regulations for temporary contracts

Note: The reference year is 2014 for Slovenia and the United Kingdom and 2015 for Lithuania.

Source: OECD Employment Protection Database, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/lfs-epl-data-en.

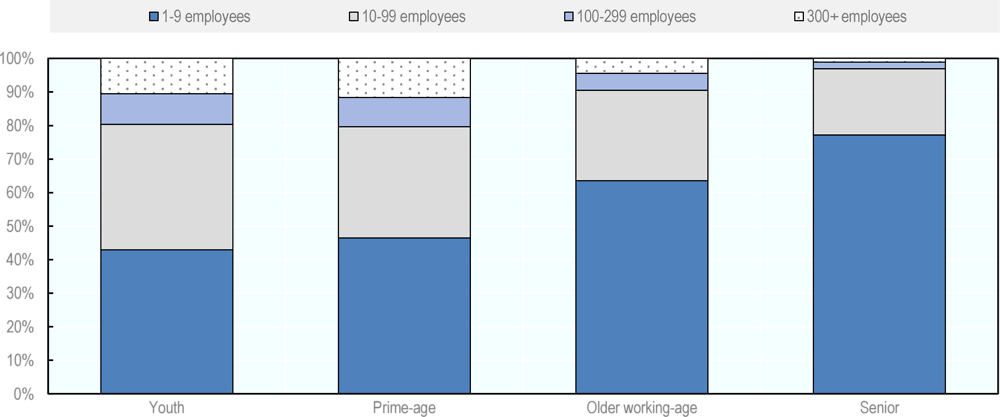

Only few young people work for a large company, but those who do, tend to have higher wages than those working in small companies. In 2017, only 10.5% of youth aged 15 to 29 years worked in a company with more than 300 employees according to the Economically Active Population Survey (Figure 3.13). The share is slightly higher among prime-age workers, where 11.6% work in a large company, but much lower among older workers. The vast majority of youth work in micro firms with 1 to 9 employees (42.9%) or firms with 10-99 employees (37.4%).

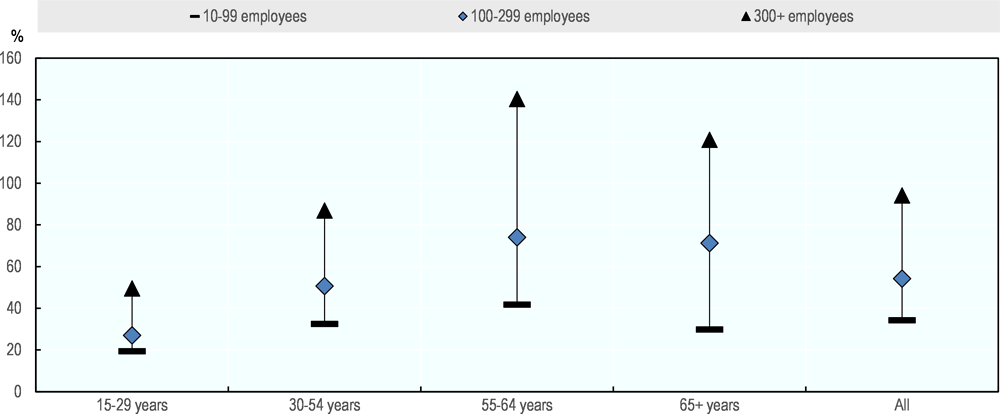

The wage premium in large firms is considerable. Among 15-29 year olds, wages tend to be 50% higher in firms with 300 employees and more compared with micro firms (1-9 employees). The earnings gap between small and large firms rises with age, reaching 140% among 55-64 year olds (Figure 3.14). However, as explained in Chapter 1, the concentration of more educated young people in larger enterprises does not explain most of their higher labour income.

Figure 3.12. Fixed-term contracts have not been replaced by other types of non-regular contracts

Notes: 1. Daily workers are workers categorised as daily workers by the worker status variable and whose jobs do not have the other non-standard characteristics listed in the legend according to the EAPS August supplement. 2. The total share of temporary workers is slightly lower than the share indicated in the figures since an individual’s employment may have multiple non-standard characteristics.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Statistics Korea (2017), 2007 and 2017 Economically Active Population Survey, Statistics Korea, Seoul.

Figure 3.13. Only one out of ten young adults work for a large company

Note: The age groups are defined as follows: Youth: 15-29 years old; Prime-age: 30-54 years old; Older working-age: 55-64 years old; and Senior: 65 years and over.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Economically Active Population Survey (Statistics Korea, 2017[28]).

Figure 3.14. The wage premium in large firms is considerable

Notes: 1. The sample is restricted to full-time employees only, defined as those working 30 hours or more per week. 2. Wages refer to earnings over the past three months.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Economically Active Population Survey (Statistics Korea, 2017[28]).

A comprehensive discussion of the product market segmentation in Korea and possible policy solutions go beyond this report, but these topics have been discussed extensively in the latest OECD Economic Survey of Korea (OECD, 2018[16]). As put forward it that report, it is crucial to reform large business groups and enhance dynamism in SMEs to achieve more inclusive economic growth. Breaking down the country’s product market polarisation would broaden the opportunities of young people in the labour market and would spread human capital more equally across economic sectors.

The policy recommendations provided in the OECD Economic Survey of Korea (see Box 3.6 for an overview) are not only necessary to ensure sustained economic growth in the coming years, but are also of key importance to improve labour market performance of the new generations in Korea and enhance their well-being. Without addressing the labour market duality created by the industrial polarisation, it will be difficult to improve the labour market performance of youth in a sustainable way.

Box 3.6. Key policy recommendations to reform large business groups and enhance dynamism in SMEs

The OECD Economic Survey of Korea 2018 puts forward the key following recommendations to address the economic polarisation in the country:

Reforming the large business groups

Strengthen product market competition by relaxing barriers to imports and inward foreign direct investment and liberalising product market regulation.

Reinforce the role of outside directors by enhancing the criteria for independence, reducing the role of management in nominating outside directors and requiring that outside directors comprise more than half of the boards in all listed firms.

Phase out existing circular shareholding by firms belonging to the same business group.

Make cumulative voting (which would allow minority shareholders to elect directors) and electronic voting (which would help minority shareholders to vote their shares) mandatory.

Follow through on the government’s pledge to not grant presidential pardons to business executives convicted of corruption.

Enhancing dynamism in SMEs to achieve higher productivity and inclusive growth

Introduce a comprehensive negative-list regulatory system and allow firms in new technologies and new industries to test their products and business models without being subject to all existing legal requirements (i.e. a regulatory sandbox).

Increase lending based on firms’ technology by expanding public institutions that provide technological analysis to private lending institutions.

Ensure that support provided to SMEs improves their productivity by carefully monitoring their performance and introducing a graduation system.

Increase the quality and availability of vocational education to reduce labour market mismatch and labour shortages in SMEs.

Source: OECD (2018[16]), OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris.

3.4. Round-up and policy recommendations

Young people perform relatively well in Korea’s segmented labour market with large differences in employment conditions between regular and non-regular workers and between small and large companies. Temporary employment is less frequent among Korean youth than among youth in OECD countries on average and transitions from non-regular to regular jobs are frequent. Although many 15-to-24 year olds in Korea hold low-paid jobs, by the time they are in their late twenties, fewer of them are in low-paid jobs than in OECD countries on average.

Despite the relatively promising labour market outcomes among Korean youth, both in an international context and compared with the generation aged 55 and over, young people are increasingly confronted with unemployment and inactivity, as presented by the rising unemployment rate and the high share of young people who are not in employment, nor in formal education or training. Indeed, the slowdown in economic growth and the resulted stronger difficulties for young people to gain access to productive and rewarding jobs call for strengthened employment and social policies to address structural issues.

To support young adults, the Government announced in March 2018 an ambitious plan with a wide range of youth support measures. Many measures are an extension of existing ones, but there are also important new initiatives. In particular, the plan represents an important shift from indirect measures, such as subsidies for firms that hire young people, towards a stronger focus on measures that directly benefit youth, such as tax exemptions and in-work benefits. However, the youth action plan remains silent about the limited social safety net for unemployed youth and it does not address the underlying structural barriers faced by youth in the Korean labour market.

The OECD Action Plan for Youth sets out a comprehensive range of measures to tackle youth unemployment and promote better outcomes for youth in the longer run by equipping them with relevant skills and removing barriers to their employment. While Chapter 2 discussed the need to improve the connection between the education system and the world of work, this chapter looked at the different aspects of the Korean social welfare and activation system, with a particular focus on the wide range of measures that the Korean government has put in place in recent years. The chapter also discussed how to reshape labour market policy and institutions to facilitate access to rewarding employment and tackle social exclusion.

In particular, Korea could improve support for young people along the following dimensions:

Expanding the social safety net for youth

Better enforce social security legislation. Strengthen compliance by expanding the resources of the relevant monitoring authorities to observe and sanction offending employers, raise penalties to increase their deterrent effect, and promote and rigorously apply the arbitration procedure through which non-insured workers can claim Employment Insurance entitlements.

Expand eligibility for Employment Insurance to voluntary job leavers. The full exclusion of voluntary job leavers is rather strict compared with many other OECD countries. Korea could consider a suspension or sanction period for voluntary job leavers to support young workers who are stuck in low-quality jobs and who need time and assistance to find a better job.

Incorporate non-standards forms of employment in the Employment Insurance scheme. Extending social protection to non-regular contracts that are currently uncovered, like in Austria or Italy, could narrow the scope for companies to opt for contractual arrangements that evade social contributions.

Ease access to the Basic Livelihood Security Programme. While the government exempts certain types of households from the family support obligation for living and health benefits since the beginning of 2019, it could go further and phase out the family support obligation completely. Abolishing this rule would bring Korea more in line with other OECD countries in terms of social assistance coverage.

Offering adequate employment support for young unemployed

Maximise the impact of the Employment Success Package Programme. In-depth evaluations suggest that the programme is quite effective in bringing participants into employment. However, the number of youth benefiting from the programme remains low. Better and more proactive outreach is needed to promote the programme among young people, possibly by increasing the provided income support to make the programme more attractive. Korea can also build on successful outreach strategies in other OECD countries. Possibly, proactive outreach could become an element in the performance evaluation of private employment services.

Strengthen private employment service provision. Private employment services tend to be very small and low-performing ones can relatively easily remain in the market. Although Korea has an elaborated rating system, there seems to be considerable room for a stricter quality assessment and contract termination for poorly performing service providers. The performance of private providers could be published online on a regular basis to guide jobseekers to the best-performing providers.

Reconsider the short duration of private providers’ contracts. One-year contracts are likely to hinder longer-term investment by private providers. To encourage them to expand their services and develop more specialised competencies, Korea could follow the example of Australia and the United Kingdom, who have gradually extended the duration of services contracts to six years.

Monitoring support for in-work poverty

Carefully monitor the impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit. Given the rapid expansion of the system, it is important to evaluate the effectiveness of the system, in particular with respect to the impact on labour supply as well as the take-up among eligible (young) people.

Facilitating access to affordable housing

Move away from support for jeonsei deposits towards housing allowances and rental market regulation. The government offers low-interest loans for housing deposits under the jeonsei system to young people at a time when landlords consider the jeonsei system no longer viable. It might be more realistic to allow the rental market to move away from the jeonsei system towards a system of monthly rentals as in most other OECD countries. The government could then support young people through other means, such as (temporary) housing allowances and rental market regulation. Korea may also wish to adopt safe and sustainable mortgage options for young people.

Addressing labour market duality

Reform large business groups and enhance dynamism in smaller firms. Without addressing the labour market duality created by the industrial polarisation, it will be difficult to improve the labour market performance of youth in a sustainable way. Breaking down the country’s product market polarisation would broaden the opportunities of young people in the labour market and would allow human capital to spread more equally across economic sectors.

References

[24] Cho, J. and J. Keum (2009), “Dualism in job stability of the Korean labour market: The impact of the 1997 financial crisis”, Pacific Economic Review, Vol. 14/1, pp. 155-175, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0106.2009.00431.x.

[18] Demographia (2015), 11th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2015 Ratings for Metropolitan Markets, New York University, New York, http://urbanizationproject.org/blog/urban-expansion (accessed on 4 February 2019).

[13] European Commission (2015), PES practices for the outreach and activation of NEETs: A contribution of the Network of Public Employment Services, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1163&langId=en.

[9] Government of Korea (2018), Youth Employment Measures.

[2] Ha, B. and S. Lee (2013), “Dual Dimensions of Non-Regular Work and SMEs in the Republic of Korea: Country Case Study on Labour Market Segmentation”, Employment Sector, Employment Working Paper, No. 148, International Labour Office, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_232510.pdf.

[3] Hong, M. (2017), “Income Inequality: Current Status and Countermeasures”, Employment and Labor Policies in Transition: Social Policy, No. 2017-05, Korea Labor Institute, Sejong-si, http://www.kli.re.kr/kli_eng.

[14] Kil, H. (2017), “Recommendations to Improve Employment Services”, Employment and Labor Policies in Transition: Social Policy, No. 2017-09, Korea Labor Institute, http://www.kli.re.kr/kli_eng.

[17] Kim, K. and M. Park (2016), “Housing Policy in the Republic of Korea”, ADBI Working Paper Series, No. 570, Asian Development Bank Institute, http://www.adb.org/publications/housing-policy-republic-korea/.

[5] Korea Labor Institute (2014), Korea Labor and Income Panel Survey, Korea Labor Institute, Sejong, https://www.kli.re.kr/klips_eng/contents.do?key=251.

[11] Lee, B. et al. (2016), Assessment and Analysis of the Outcome of the Successful Employment Package and Improvement Measures, Ministry of Employment and Labor (in Korean).

[21] Lee, H. (2015), “Comparisons of Young Renter Households’ Housing Situation by Locations Reflected in the 2012 Korea Housing Survey”, Journal of the Korean Housing Association, Vol. 26/1, pp. 81-90, http://dx.doi.org/10.6107/JKHA.2015.26.1.081.

[27] OECD (2019), OECD Employment Outlook 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[23] OECD (2018), Good jobs for all in a changing world of work: The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[19] OECD (2018), Housing Dynamics in Korea: Building Inclusive and Smart Cities, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264298880-en.

[16] OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-kor-2018-en.

[10] OECD (2018), The Future of Social Protection: What Works for Non-standard Workers?, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264306943-en.

[7] OECD (2018), Towards Better Social and Employment Security in Korea, Connecting People with Jobs, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264288256-en.

[8] OECD (2018), Working Better with Age: Korea, Ageing and Employment Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264208261-en.

[26] OECD (2016), OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-kor-2016-en.

[12] OECD (2016), Society at a Glance 2016: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264261488-en.

[1] OECD (2013), Strengthening Social Cohesion in Korea, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264188945-en.

[6] OECD (2013), The OECD Action Plan for Youth: Giving Youth a Better Start in the Labour Market, Meeting of the OECD Council at Ministerial Level, 29-30 May 2013, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/employment/Action-plan-youth.pdf.

[22] Salvi del Pero, A. et al. (2016), “Policies to promote access to good-quality affordable housing in OECD countries”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 176, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jm3p5gl4djd-en.

[4] Schauer, J. (2018), “Labor Market Duality in Korea”, IMF Working Paper, No. WP/18/126, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2018/06/01/Labor-Market-Duality-in-Korea-45902.

[20] Seo, B. and Y. Joo (2018), “Housing the very poor or the young? Implications of the changing public housing policy in South Korea”, Housing Studies, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2018.1424808.