This chapter analyses stages of young Koreans’ educational and labour market trajectories that can contribute to skill mismatches. It first provides an overview of Korean students’ choices concerning general and vocational education and discusses career guidance policies. In the following two parts, the chapter focuses on initiatives to strengthen the quality and labour market relevance of upper secondary vocational and tertiary education, respectively. Finally, it presents current practices and advantages of competency-based hiring.

Investing in Youth: Korea

2. Reducing the gap between skill supply and demand in Korea

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction

Korean youth and their parents value education highly, but their skills do not always match labour market needs. Many graduates spend a long time searching for a job or report that their qualification exceeds their job requirements. At the same time, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) struggle to fill positions.

Mismatches can emerge during different phases of skills acquisition and recognition. A first inception moment occurs when students’ field of study choice follows personal, parental or even societal preferences and disregards labour market needs. A second source is education and training that fails to equip youngsters with solid and relevant knowledge and competences, potentially because institutions fail to keep up with rapid changes in labour market needs. A third cause arises when candidates or businesses have inefficient job search or hiring practices. Finally, rapid structural and technical change can render previously in-demand skills obsolete.1

This chapter analyses the sources of skill mismatches in Korea and proposes policy remedies. Section 2.1 discusses students’ educational choices and possible improvements to secondary-level career counselling. Section 2.2 reviews Korea’s upper secondary vocational education and training (VET) system and proposes ways to strengthen the system further. Section 2.3 focuses on existing and potential links between tertiary institutions and employers. Section 2.4 describes hiring practices and suggests ways to bolster competency-based recruitment.

2.1. Guiding students to improve educational choices

Many Koreans consider a bachelor’s degree as the lowest acceptable qualification level. More than eight out of ten Korean teenagers2 and nine out of ten Korean parents (Jones, 2013[1]) hope that they or their child will obtain a four-year university degree at a minimum. This preference, which partially stems from society’s disdain of vocational education (Park et al., 2010[2]), pushes students to attend even sub-par tertiary institutions.

Building on Chapter 1’s findings, this section shows that young Koreans do not always benefit from higher education as the default choice and proposes ways in which the Korean government can reinforce its recent investments in career counselling at the secondary school level.

2.1.1. Strong societal preference for general education

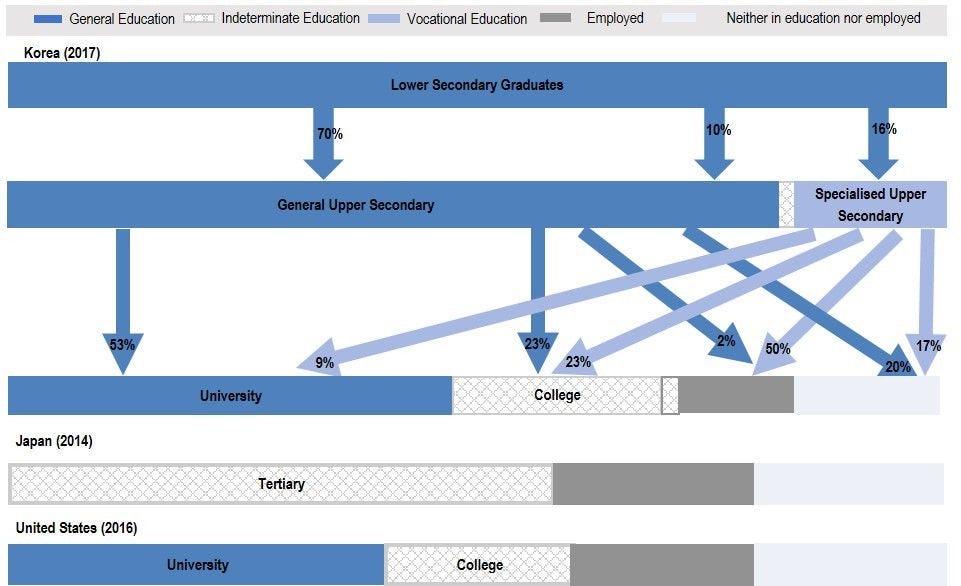

Two key decisions determine the education and training path of young Koreans. The first decision occurs when students complete their lower secondary education and choose between general or vocational upper secondary education.3 The second decision happens after they complete upper secondary education: they can enter the labour market, pursue a general or vocational two-to-three year college degree or enter university in pursuit of a four-year bachelor’s degree. At both junctures, the majority chooses general over vocational education (Figure 2.1). In fact, over the past two decades, the share of upper secondary students attending a vocational school has roughly halved from one third in the year 2000 (Park, 2011[3]) to around 16% in 2017. However, compared to only a few years ago, upper secondary vocational students are now more likely to start a job than to advance to college or university. Nevertheless, the orientation towards education over labour market entry remains stronger than in Japan and the United States (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. The majority of young people select general upper secondary education and advance towards tertiary education

Note: The arrows indicate the percentage of graduates from the respective lower or upper secondary institution that advance to the different further education or employment options. The length of each bar represents the overall percentage distribution. For the upper secondary level, the types of schools that not directly named are autonomous high schools, special high schools and special-purpose high schools (including Meister high schools and high schools with other special focuses, such as foreign languages). Specialised upper secondary are general upper secondary vocational schools. The options not shown for the post-upper secondary phase are non-tertiary post-secondary education and military service. ‘Non-employed’ refers to all upper secondary school graduates who are neither in education nor enlisted or employed. The United States figures are based on a weighted average of 2016 upper secondary graduates and 2013-2014 upper secondary dropouts.

Source: Korean Educational Statistics (n.d.[4]), 2017 Educational Statistics: “Number of students in kindergarten/elementary and secondary school” and “Situation after graduation from high school”; Bureau of Labor Statistics (2017[5]), College Enrolment and Work Activity of High School Graduates News Release; and Statistics Japan (2016[6]), Statistical Yearbook.

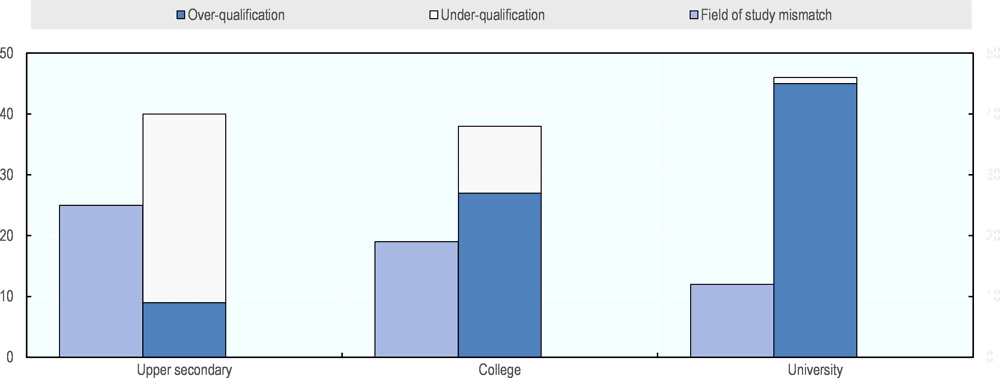

Individuals’ choices influence whether they end up in a job that matches their interests and skills. Figure 2.2 shows that over-qualification rates rise with education, with 45% of university students being over-qualified for their current job. At the same time, graduating from upper secondary schools with a vocational focus or from a tertiary institution in a field with clearly defined professional pathways is associated with a significantly lower likelihood of being over-qualified. For instance, graduates from pharmacology departments are 26 percentage points less likely to report being over-qualified for their job than similar tertiary graduates of other departments are.

However, the skills of over-qualified workers may not be as high as their additional qualifications suggest. Indeed, across the OECD and in Korea, few over-qualified workers have literacy skills that exceed their job’s requirements (OECD, 2016[7]). Calculations based on the Korean Youth Panel also show over-qualification is prevalent among students who rank lowest in their class. A possible explanation is that low-ranked students have little aptitude for their chosen path. However, low self-reported class rank might also reveal low self-confidence that can push graduates to apply for jobs below their qualification level.

Figure 2.2. University graduates are more frequently over-qualified than those with less education

Note: Individuals are classified as over-/under-qualified if they highest educational achievement is above/below the self-reported minimum level of education required to carry out the job. Field-of-study mismatch occurs when respondents say that there is (very) little agreement between their current job content and their major.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Youth Panel (National Youth Policy Institute, 2015[8]).

Workers who are more qualified and skilled than their job requires on average make less money than well-matched workers do. This finding is true across the OECD and in Korea for all age groups (OECD, 2016[7]). Settling for a lower-level job at the beginning of one’s career can also increase the probability of having a mismatched job several years down the line (Meroni and Vera-Toscano, 2017[9]), lead to permanently lower wages (Korpi and Tåhlin, 2009[10]) and lower job satisfaction (Quintini, 2011[11]).

Career guidance can address such mismatches: it helps students select programs that offer good career prospects and correspond to their interests and aptitudes. It can also boost student’s confidence in their abilities and choices. Over time, guidance may even be able to change societal perceptions about desirable career options. The following two sections discuss the government’s existing career counselling measures at the secondary level and propose further improvements.

2.1.2. The government has increased investments in career counselling

Quality career counselling can help youth make informed educational choices and transition more easily from school to work. To take informed decisions about their future, secondary students need to know what occupations exist, what kind of training and education they require and how much demand the labour market has for these occupations. They also need to assess how their own interests, strengths and weaknesses fit in with different occupations in a realistic way. Unfortunately, the people they turn to for advice – parents, siblings, teachers – may not be knowledgeable about career options and may discount vocational occupations in particular (Musset and Mytna Kurekova, 2018[12]). Career information and counselling can address these information deficits.

In recent years, the Korean government has invested heavily in career guidance. Its strategy is to create career awareness in primary school, offer career exploration in lower secondary school and stimulate career planning in upper secondary school (ICCDPP, 2017[13]):

The Ministry of Education recruited more than 5 000 career counsellors for lower and upper secondary schools, covering nearly 95% of schools by 2014.

A weekly letter informs parents about career options.

Students can access occupational information and aptitude tests from a variety of sources, including Career-net provided by the Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training’s (KRIVET) Career Development Centre and Work-net and HRD-net provided by the Ministry of Employment and Labour.

The 2015 Career Education Act offers the possibility to create Regional Career Education Centre under the auspices of the National Career Education Centre ((n.a.), 2015[14]).

In 2016, the Ministry of Education launched the Free Learning Semester nation-wide. It usually takes place in the first semester of lower secondary schools. The semester allows students to explore subjects beyond the core curriculum. Since there are no exams during the semester, students can visit workplaces on days usually reserved for exams (OECD, 2017[15]).

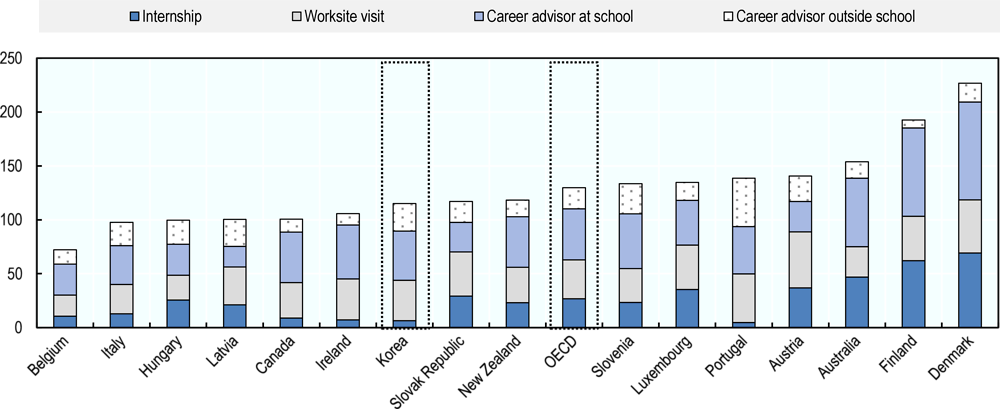

Nonetheless, there remains room for further improvements in career guidance in Korea. In 2012, the share of 15-year old PISA test takers who had participated in a workplace visit (37%) or seen a career advisor at school (46%) were close to the OECD cross-country averages (36% and 46%, respectively), but considerably below countries like Denmark, Finland and Australia (Figure 2.3). Given the recent initiatives, the share probably improved since 2012. But one area where Korea was underperforming in 2012 is unlikely to have seen drastic improvements: internships for lower secondary students. Only 6% of 15-year olds had completed an internship, compared to the OECD average of 27% and 69% in Denmark. The recent career guidance initiatives do not encompass internships in lower secondary schools.

Figure 2.3. In 2012, few Korean secondary students had completed internships

Note: Countries are sorted in ascending order of the sum of the percentage of students who accessed the different types of career guidance. These sums can exceed 100 because the same student can access multiple forms of career guidance.

Source: OECD PISA 2012, www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/pisa2012database-downloadabledate.htm.

2.1.3. Relatively small adjustments could boost career counselling’s pay-offs

Korea’s recent investment in secondary-level career counselling is a good start. It follows international best practice in that it encourages children and teenagers to start thinking about possible careers at an early age (OECD, 2017[15]). Nevertheless, further changes that ensure the quality of career counselling, engage disadvantaged youth and strengthen community links can boost the payoffs.

Safeguarding the quality of career counselling

Career counsellors’ skills and knowledge are a key ingredient to successful career guidance. If counsellors do not know enough about available academic and non-academic education and training pathways and in-demand skills, they are unable to provide students with the information they need to make informed choices about their further trajectory (OECD, 2011[16]). At the same time, even knowledgeable and skilled career counsellors require support from other teachers and will have a limited influence on their students’ outcomes if they are stretched too thin.

Korea imposes minimum training requirements for in-school career counsellors and offers expanding training options. Currently, career guidance counselling teachers in secondary school have completed a full teaching degree as well as an additional 570 hour training. Despite the mandatory training, the skills of counsellors vary from school to school (Yoon and Pyun, 2017[17]). The Korean government is aware of potential skill deficits among school-based career counsellors. It therefore introduced graduate-level courses in career counselling for current primary and secondary school counsellors at ten graduate schools from 2017 onwards (Yoon and Pyun, 2017[17]).

In some OECD countries, post-secondary education and continuous training are mandatory for school-based career counsellors. For example, in the Australian state of New South Wales, career advisers are secondary teachers who have completed an additional post-graduate certificate (NSW Department of Education, 2017[18]). It is difficult to evaluate the effects of different levels of initial and continuing training on the quality of career guidance and the eventual educational and labour outcomes of students. But given the range of skills and knowledge a career counsellor needs to possess to be able to connect with students and provide high-quality guidance, a professionalization of the role appears necessary (OECD, 2004[19]). It therefore makes sense for Korea to maintain its mandatory training requirements and expand post-graduate training in career counselling.

A quality assurance mechanism can be an additional tool for schools to establish high quality career guidance. One possible initiative is a self-administered benchmarking tool such as the ones that Careers New Zealand developed. The benchmarking tool asks schools to rate themselves on detailed career guidance outcomes and inputs, allowing them to identify their strengths and weaknesses (Careers New Zealand, 2016[20]). Evidence suggests that schools that did not receive specific assistance from Careers New Zealand reviewed fewer dimensions of their career guidance services and did so less confidently than schools that cooperated with Careers New Zealand (Education Review Office, 2015[21]). These findings indicate that self-assessment tools are most useful when the government body that develops them helps to train school staff on their use. Korea could consider adopting similar benchmark indicators and involving the Regional Career Education Centres in training schools in their use for self-assessment exercises.

Korean secondary schools are required to have at least one Career Guidance Counselling teacher. These teachers have numerous duties, including teaching the Careers and Occupations class, providing group and individual career counselling, and carrying out psychological assessments. This multitude of duties, as well as the fact that there is an average of nearly 430 students per school (at the lower secondary level) (Korean Educational Statistics, n.d.[4]), often leads to a high workload for the career guidance teacher, who usually carries out his or her tasks without support staff (Yoon and Pyun, 2017[17]).

The first potential solution to decrease the workload of counselling teachers to a manageable level is to hire more personnel – either counselling teachers or support staff. This approach obviously has large cost implications. It may also be difficult to implement if qualified staff are scarce and training facilities limited. The approach’s advantage is that it would increase the capacity to offer individualised counselling rather than group-level guidance. Evidence from Utah suggests that lower counsellor-to-student ratios can improve students’ career planning (Carey et al., 2012[22]). Given the high costs, a pilot program or staggered rollout could provide evidence on whether increasing the number of counselling teachers improves graduate outcomes.

Another possibility is to integrate career education into regular classes. Out of nine OECD countries, in 2015, Korea was the leader in incorporating career guidance and counselling training in its initial teacher education and professional activities (Musset and Mytna Kurekova, 2018[12]). However, subject-matter teachers may still be reluctant to integrate career education into their classes (Yoon and Pyun, 2017[17]). This difficulty is not restricted to Korea: teachers may generally fear that career education takes time away from teaching their core curriculum (Yates and Bruce, 2017[23]), and may not know how to integrate career topics into their classes (The Gatsby Charitable Foundation, 2014[24]). Targeted tips on how to improve lesson planning can help: in North Carolina, a pilot programme provided lower secondary teachers with a half-day group training and ten sample lesson plans tailored to their subjects. This intervention successfully increased the presentation of career-relevant material and boosted student scores in mathematics, but not in other subjects (Rose et al., 2012[25]; Woolley et al., 2013[26]). One possible interpretation is that in other subjects, teachers would require more initial training. Korea should maintain its practice of including counselling training in initial and continued teacher training and could consider adapting successful lessons from other contexts, such as the North Carolinian programme.

Adapting to the needs of disadvantaged youth

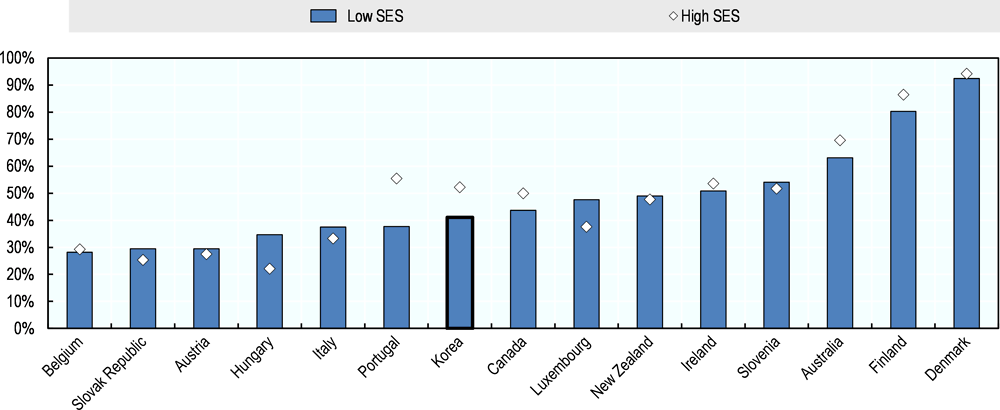

The effectiveness of career counselling depends on the (potential) advisee’s participation in and engagement with the process, but both are affected by the advisee’s socio-economic background. Paradoxically, it can mean that the students most in need of career guidance – those who are less aware of different professional options, have lower career aspirations or face economic barriers – receive the least amount of counselling. Indeed, in most OECD countries, more disadvantaged students participate less in career guidance activities than advantaged students do (Figure 2.4). The difference is larger in Korea than in all other participating OECD countries except Portugal. The gap further widens at university level, where employment support programs are more effective for students from higher socio-economic backgrounds (Shin et al., 2012[27]).

Figure 2.4. Disadvantaged students receive less career counselling

Note: The shares are estimated based on survey results from the 2015 wave of the PISA survey.

Source: Musset and Mytna Kurekova (2018[12]), Figure 4.3. School-based career activities and participation by SES.

Career counselling design needs to acknowledge this reality and actively pursue a more equitable approach. While Korea’ Career Education Act of 2015 mentions that state or local governments need to implement measures to provide career education to students who are disabled, from low-income families or North Korean refugees ((n.a.), 2015[14]), the act does not specify what policies should flow from this prescription.

Possible interventions could either take the form of programmes targeted towards disadvantaged or at-risk groups, or general programmes designed in such a way that they assure adequate participation of these groups. The two approaches have different advantages. Targeted programs can directly address the stronger needs of disadvantaged students, while general programs do not need to single out these same students in a way that may be uncomfortable for them. Among targeted interventions, the Swiss LIFT programme is a positive example. The program assists students from ninth to eleventh grade who are considered ‘at risk’ because of their school performance or social background with targeted support including work experience (3-5 hours per week) and counselling. Although there was no experimental design demonstrating how the intervention affected the participants, young people who completed the program had a higher probability of advancing towards an apprenticeship (Balzer, 2017[28]). Non-targeted programs can be more equitable in terms of the amount of career guidance students receive (but not necessarily in outcomes) if many components are mandatory. A non-targeted programme that is believed to be effective is compulsory one-on-one career counselling for students approaching important transition points of lower to upper secondary education and of graduation from upper secondary school (OECD, 2010[29]).

Involving employers

Making schools a venue in which students, parents and employers come together can change society’s perceptions about the relative worth of different education and career trajectories and can improve students’ engagement in and outcomes from career counselling. Students may perceive workers’ testimonials as more reliable and insightful than information provided by career professionals, publications or websites. Empirical evidence suggests that young people value contacts with businesses and that these school-facilitated encounters may increase their later earnings (Mann and Percy, 2014[30]; Kashefpakdel and Percy, 2017[31]). More realistic expectations and confidence in the occupation selection and job search processes could explain this outcome. Employers may benefit from the prestige associated with being a ‘good citizen’ participating in community-minded events and, potentially, from steering young people towards occupations with current shortages. However, since these benefits are more difficult to measure and can take a long time to materialise, co-operation programmes should make it as simple as possible for employers to participate. For example, to get a job shadowing programme in North Carolina off the ground, a toolkit was developed that assisted employers in their tasks (Musset and Mytna Kurekova, 2018[12]).

In practical terms, employer involvement in career education can take various forms, including:

Information events or career fairs at school: These events are usually easier to organise and less expensive than other programmes.

Workplace visits: Such visits may be particularly interesting for young people and are also not very costly to set up. If parents are involved, these visits may also help change their perceptions: For example, when Siemens invited parents and high school students to visit one of its new plants in North Carolina, many parents changed their mind about whether their children had a future in manufacturing (Mourshed, Farrell and Barton, 2013[32]).

Job shadowing: In a job shadowing programme, students visit a workplace for multiple days and observe the day-to-day work of one or several workers. Compared to longer internships, job shadowing takes less time. These programmes may be particularly appropriate for lower secondary school students to get a first feel for the reality of workplaces and are less costly for employers than internships. Several OECD countries, including France and Norway, have made job shadowing mandatory for students in the last years of lower secondary education.

Mentorship programmes: Of the different forms of employer engagement, mentoring programmes may be the hardest to organise on a school-wide basis. Mentors have to remain engaged in the process and finding a sufficient number of motivated individuals to take up this function may be difficult. A possibility would be to target mentoring programmes to at-risk youth. This approach was, for example, taken in a German programme called “Coaching for the transition to work” that improved the career planning and transitions of young people (Musset and Mytna Kurekova, 2018[12]).

Internships: Longer internships go beyond the ‘taste’ of work life that shorter work-shadowing programmes provide. They offer students the opportunity to carry out some limited tasks themselves and therefore stand between work shadowing programmes on the one hand and apprenticeships (see Section 2.2) on the other hand. There is little evidence on whether internships offer more benefits to secondary-level students than shorter work shadowing programmes, especially for students at the lower secondary level. If students have to secure their own internships, disadvantaged students may not have access to the same quality of internships as students from more advantaged backgrounds who can use their parents’ networks to find an interesting opportunity.

To ensure that students learn about a sufficiently broad spectrum of occupations and sectors, it is important that schools initiate these school-employer co-operations rather than relying on employers to step forward. For instance, in the United Kingdom, the different regional governments have enshrined schools’ obligation to create employer engagement programmes in law (Mann and Percy, 2014[30]). Nevertheless, local governments and other government institutions can also assist schools in creating employer engagement programmes. For instance, since creating internship programmes can be labour-intensive, local governments or employment agencies may create their own programmes. An example is New York City’s summer internship programme. This programme is open to 14-24 year olds from disadvantaged backgrounds since the 1960s. It is very popular and appears to have positive social and labour market impacts (OECD, 2016[33]).

2.2. Promoting upper secondary vocational education

Encouraging young people to consider whether occupations with current or projected labour supply shortages are right for them is only the first step towards easing skill mismatches. As a second step, education and training programs need to equip youth with the skill set they actually need for their chosen occupation. This requirement applies equally to vocational and general education programs and to secondary and tertiary institutions. This section shows why SMEs suffer more from skill shortages than large companies and proposes ways in which further changes to upper secondary vocational education and training can ameliorate this situation. Section 2.3 then takes up the issue of the quality of tertiary education.

2.2.1. Skill shortages are common in SMEs and for occupations requiring an upper secondary education

Skill mismatches do not only affect workers, but also companies unable to fill vacancies appropriately. While under-qualified workers are typically less productive (Mahy, Rycz and Vermeylen, 2015[34]), the effect of unfilled positions can be even more negative (Bennett and McGuinness, 2009[35]; Tang and Wang, 2005[36]).

In Korea, skill shortages exist and affect SMEs in particular, but it is unclear whether the problem is worse than elsewhere. A Korean survey (OECD, 2014[37]) suggests that 40% of SMEs experienced skill shortages, while a 43-country survey that did not include Korea reported skill shortages among 45% of small and 56% of medium-sized enterprises (Manpower Group, 2018[38]). While the two surveys are not directly comparable, they do not suggest that the skill shortage problem is particularly bad in Korea. However, both Korean surveys (Ministry of Employment and Labour, 2018[39]) and cross-national surveys (Manpower Group, 2018[40]) indicate that in Korea, SMEs report skill shortages more frequently than large firms, while in most other OECD countries, the opposite is true.

Skill shortages vary across sectors and occupations. Results from the Occupational Labour Force Survey (Ministry of Employment and Labour, 2018[39]) indicate that some sectors including transportation, manufacturing and information and communication are harder hit by skill shortages (as measured by the ratio of unfilled to total job openings) than others. The same survey shows that most of the unfilled job openings in occupations with large skill shortages – such as driving, food processing and machine operating – have low or intermediate skill requirements.4 Overall, in 2018, 37% of unfilled job openings required an upper secondary degree, more than the unfilled job openings for all levels of tertiary education put together. Strengthening vocational education at the upper secondary level that prepares students for direct labour market entry could help address these skill shortages.

The higher concentration of unfilled vacancies in lower-skilled occupations and in SMEs put forward two conclusions: First, skill shortages could decrease if more students chose vocational over general education at the upper secondary level. Second, since increasing their comparatively low wage levels is not an option for many SMEs (see Chapter 3), investing in the training of apprentices can slightly alleviate their difficulties in filling vacancies with skilled workers. Recent initiatives of the Korean government related to reforms of upper secondary vocational education and to apprenticeships suggest that the government agrees with these conclusions.

2.2.2. Several initiatives aim to make upper secondary vocational education more attractive

Vocational upper secondary schools traditionally educated a large share of Korea’s workforce, but their importance has declined. Reforms in the 1990s expanded higher education. Along with a general preference for higher education among Korean parents and youth, these reforms contributed to the shift from vocational to general education (Cheon, 2014[41]).

To counter-act this development, the Korean government has diversified vocational education options in the hope of attracting more young people to the field and training the type of workers employers require. Previously, upper secondary vocational students generally attended ‘specialised high schools’. Training at these schools usually focused on comparatively simple tasks and employer engagement was limited. As a result, many employers regarded graduates from vocational schools as low-skilled workers (World Economic Forum, 2014[42]). The two most important measures aiming to address this weakness are the introduction of Meister schools and apprenticeships:

Meister schools, a type of special purpose upper secondary schools focused on practical vocational training, were introduced in 2010. Unlike other upper secondary schools, these schools select their students and are tuition-free. As a result, they are far more costly for the government than regular vocational upper secondary schools (Lee, Kim and Lee, 2016[43]). Meister schools develop their curriculum jointly with industry representatives and internships are a mandatory part of the programme. During the first year, Meister schools focus on basic skills, such as computer literacy and soft skills, and introduce students to different industries. From the second year onwards, students specialise and receive more occupation-specific training (World Economic Forum, 2014[42]). Around 1% of upper secondary students attended a Meister school in 2017.

Apprenticeships, introduced in Korea in 2013, combine theoretical education at an upper secondary level5 with practical training in the company that hires the apprentices. The degrees awarded to graduates are based on National Competency Standards (see Box 2.1). In October 2016, 8 345 companies were participating in the programme. More than 25 000 apprentices had either already graduated or were currently attending an apprenticeship programme (Kang, Jeon and Lee, 2017[44]).

The two programmes are relatively successful at securing employment for their graduates. For example, Meister school graduates are more likely to be employed than graduates of regular upper secondary vocational schools are. However, they do not necessarily earn more than regular vocational school graduates do (Lee, Kim and Lee, 2016[43]). The majority of apprentices already hold unlimited contracts during their apprenticeship (Kang, Jeon and Lee, 2017[44]).

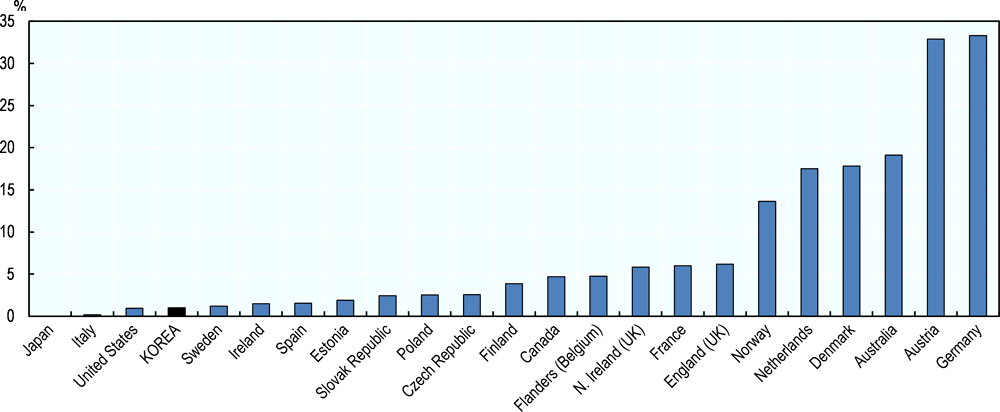

Despite these promising outcomes, very few students participate in these programmes. In 2012, only 1% of students enrolled in upper secondary and short post-secondary education were participating in an apprenticeship programme. Although the share nearly doubled since 2012, Korea remains at the bottom of the OECD ranking and far below the OECD 2012 (23 countries or regions) average of 6% (Figure 2.5).

Box 2.1. The development of a National Qualification Framework and National Competency Standards

In a joint initiative between the Ministry of Employment and Labour and the Ministry of Education, Korea is currently creating a framework based on National Competency Standards (NCS). The framework highlights the equivalence of different qualifications and work experience, defines the knowledge and skills required for each competence, and provide the basis for NCS learning modules. The process of developing competency standards and pilot-testing them has been ongoing since 2013 and is now almost complete. The incorporation of competence standards in the development of school curricula, in the creation of certificates and in the hiring practices of enterprises is work in progress.

The National Competency Standards are developed in the context of a National Qualification Framework (NQF). Governments all over the world are adopting such frameworks as a means of transitioning towards a competency-based skill development and recognition system. These frameworks define qualification levels, classify different qualifications according to those levels and outline criteria for acquiring a given qualification. Countries have different goals when introducing National Qualification Frameworks, including promoting lifelong learning, raising the prestige of vocational education and assuring the quality of education and training programmes (Tuck, 2007[45]). Supporting policies need to accompany the introduction of the frameworks to achieve these aims.

In Korea, in a reversal of the typical order of qualification framework development, working groups consisting of ministry representatives and industry, education and qualification experts first developed the different standards and defined qualification levels only afterwards (OECD, 2017[15]; Kim, Kim and Kim, 2014[46]).

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Skills Strategy Diagnostic Report: Korea 2015, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264300286-en; Kim, S., M. Kim and S. Kim (2014), An Implementation Plan for the National Qualifications Framework (NQF) for Lifelong Vocational Competency Development, Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training, Seoul; Tuck, R. (2007), An Introductory Guide to National Qualifications Frameworks: Conceptual and Practical Issues for Policy Makers, International Labour Office, Geneva.

Figure 2.5. Apprenticeships are far less common in Korea than in many other OECD countries

Note: 16-25 year-olds pursuing a programme at ISCED 3 and ISCED 4C level.

Source: Kuczera, M. (2017[47]), "Striking the right balance: Costs and benefits of apprenticeship", OECD Education Working Papers, No. 153, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/995fff01-en

Despite these promising outcomes, very few students participate in these programmes. In 2012, only 1% of students enrolled in upper secondary and short post-secondary education were participating in an apprenticeship programme. Although the share nearly doubled since 2012, Korea remains at the bottom of the OECD ranking and far below the OECD 2012 (23 countries or regions) average of 6% (Figure 2.5).

2.2.3. The relevance of upper secondary vocational education needs to be strengthened

Korea is making considerable efforts to promote vocational education. Certain indications, such as the declining share of upper secondary graduates who immediately enrol in college or university, suggest that the initiatives are paying off in terms of reducing over-investments in education. Nevertheless, the programmes can be even more impactful.

Boost the relevance and quality of vocational upper secondary schools

Korea’s upper secondary vocational education system is in the middle of a full re-organisation. In addition to the establishment of Meister Schools and the re-introduction of apprenticeships, the government is also reducing the number of regular vocational upper secondary schools and aiming to align curricula to National Competency Standards (see Box 2.1). Given the scope of these changes, it makes sense to assess systematically how successful the reforms have been. In the meantime, the thrust of reforms can be further supported.

A first potential measure is to create additional Meister schools in service-related occupations. Existing Meister schools already cover an impressive number of activity areas ranging from advanced urban agriculture, mechanical engineering and shipbuilding over information science, semiconductors and robotics to food science and horse-related occupations (Ministry of Education, 2018[48]). While the government may reasonably wish to limit the number of Meister schools for financial reasons and to preserve their special status, a few additional schools could cover the training needs of other sectors. This recommendation applies in particular to service sector occupations, for which the Korea Employment Information Service forecasted an under-supply of new entrants with upper secondary education over the 2014-2023 period (KEIS, 2015[49]).

Moreover, regular vocational upper secondary schools can incorporate elements of the Meister schools. Key among them is a stronger connection with industry. For example, schools can cooperate with companies to create internship opportunities for their students. Temporary placements with companies can also ensure that teachers’ skills remain updated. Evidence from Finland suggests that such placements can raise the quality of vocational education and should occur in intervals of at most five years (Frisk, 2015[50]).

Finally, the way in which competence-standard based curricula are created may have to be adjusted. Currently, a study of ten vocational training institutes revealed increased administrative costs and teaching requirements that included ‘unnecessary’ at the expense of ‘necessary’ material (Lee, Ra and Ryu, 2016[51]). In addition, another study suggests that competency standards-based curricula often do not develop students’ theoretical knowledge sufficiently (Chio et al., 2015[52]), a criticism that has also surfaced in other OECD countries such as the Netherlands (Mulder, Weigel and Collins, 2007[53]). This situation increases the risk that acquired skills and knowledge do not transfer to other occupations and that they become obsolete more quickly. Australia’s experience suggests that leaving some flexibility in curricula in terms of what training elements are required can strengthen their acceptance by educators (Allais, 2010[54]).

Broaden the scope of apprenticeships

The Korean government recognises that apprenticeship can ease the school-to-work transition and improve the functioning of the labour market. In fact, countries in which more youth are apprentices tend to have a lower prevalence of skill mismatches (Quintini, 2011[11]). Offering a broader range of apprenticeships – in terms of length, occupations and types of employers - can increase the demand for and supply of apprenticeships and hence involve a larger number of young people.

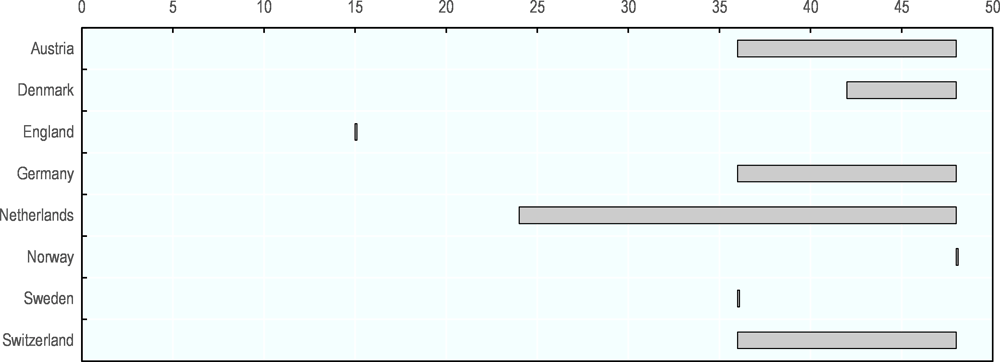

Korean apprenticeships are shorter than in many other OECD countries. Three quarters of Korean apprentices train with a company for twelve months (Kang, Jeon and Lee, 2017[44]). While a few other OECD countries, such as France and Lithuania, also offer short apprenticeship programmes, in many others, including Germany, Switzerland and the United States, the majority of programmes are longer (G20/OECD/EC, 2014[55]) (Figure 2.6). Under the right circumstances, apprentices acquire a broader set of sets and deeper knowledge if they train longer. Moreover, employers can recover more of their initial investment by working with more experienced apprentices. Indeed, in several OECD countries with longer apprenticeships such as Austria, Germany and Switzerland, 70% or more of the time apprentices spend with a company is productive work the company benefits from directly, as opposed to time spend on theoretical or practical training (Kuczera, 2017[47]).

Korea can benefit from expanding the duration of the typical apprenticeships. However, any expansion needs to bring real benefits to the apprentices in the form of a more thorough training. A 2012 reform that set the minimum length of an English apprenticeship to one year for example had mixed effects: it decreased the number of apprentices that started and completed the programme on the one hand, but increased the earnings of those that graduated (Nafilyan and Speckesser, 2017[56]).

Most Korean employers offering apprenticeships are in the industrial rather than service sector. Companies in the machinery and robotics sector alone account for more than one third of apprenticeship providers, and companies in information and communication technology, electronics and chemistry for another third (Kang, Jeon and Lee, 2017[44]). Elsewhere, the service sector is much more active. For example in Australia in 2009, the five most common apprenticeship programmes were in service occupations, jointly accounting for about 60% of apprenticeship positions (Steedman, 2010[57]).

More service-related apprenticeships could lower the need to attend college for students who want to work in this area and provide service-sector employers with appropriately skilled workers. It is even possible (though far from guaranteed) that this extension could contribute to a reduction in the productivity gap between the manufacturing and service sectors: In Italy, a reform that increased the number of apprenticeships increased firms’ productivity (Cappellari, Dell’Aringa and Leonardi, 2012[58]). However, productivity gains could vary across sectors. A report by a UK-based consulting firm suggests that the productivity gains from completing an apprenticeship are below average in the retail sector, although this may be due to shorter apprenticeships (Centre for Economics and Business Research, 2013[59]).

Figure 2.6. In several OECD countries, apprenticeships last multiple years

Note: The value for England indicates the average duration of apprenticeships.

Source: Kuczera (2017[47]), Striking the right balance: Costs and benefits of apprenticeship, “Table 3. What is the duration of an apprenticeship and how much work placement does it involve?”.

The overwhelming majority of Korean apprenticeship providers are SMEs: 96% of providers have fewer than 299 employees (Kang, Jeon and Lee, 2017[44]). In other OECD countries, SMEs also predominate among apprenticeship providers, though often less dramatically so. For example, in France, SMEs (which in France include enterprises with up to 250 employees) provided three quarters of new apprenticeships (BusinessEurope/CEEP/UEAPME, 2016[60]).

Korea should continue to support SMEs in offering apprenticeships, but could also consider involving large employers. This option would have several benefits. First, the number of apprenticeship spots could increase. Second, educational institutions could recruit training partners at lower costs. Third and most importantly, the prestige of apprenticeships could rise. Large companies would also benefit by having young workers with more targeted skills than those recruited from general college or university programmes. In practical terms, the government could continue to restrict apprenticeship subsidies to SMEs but simultaneously encourage upper secondary vocational schools and other educational institutions offering apprenticeships to reach out to large companies in addition to continuing their recruitment efforts with SMEs.

However, any efforts to involve larger employers in apprenticeship schemes need to be undertaken carefully. Evidence from Germany and the Netherlands suggests that apprentices in larger firms have better basic skills. One possible reason is that these firms attract apprentices with higher innate ability (Kuczera, 2017[47]). If this ‘skill magnet hypothesis’ is correct, it represents a problem if large enterprises ‘empty’ the pool of existing qualified applicants. On the other hand, if apprentices at large enterprises are higher-ability workers that would otherwise not consider becoming apprentices, then the effects would be positive. Therefore, it would be advisable to carry out a pilot programme in one sector or region first.

Lower the costs and increase the pay-offs from apprenticeships

A company will only offer apprenticeships if the perceived short- and long-term benefits exceed the immediate costs. The main short-term benefit is the apprentices’ productive work. The main long-term benefits are reduced recruitment costs and an improved skill fit among workers. The principal costs, in addition to the apprentices’ wages, are the wage costs of the employees providing the apprentices’ training and, depending on the sector and occupation, training equipment costs. Apprenticeship wages are frequently set at the sectoral level, are below the wages of skilled workers and rise over the training period. Overall, the net costs are higher when enterprises predominantly develop their apprentices’ general rather than firm-specific skills. This effect is particularly true if a large share of former apprentices does not stay on with the firm that trained them.

Governments have various instruments at their disposal to increase benefits and reduce or defray costs. Under certain conditions, some countries including the Netherlands and the United Kingdom allow apprenticeship wages to be set below the minimum wage. Other countries, such as Denmark, exempt apprenticeship wages from employer social security contributions or subsidise these contributions, such as in Austria (Kuczera, 2017[47]). The Korean government already provides subsidies to SMEs that offset part of the training costs. Without these subsidies, providing apprenticeships would not be viable for some firms (Jones and Fukawa, 2016[61]). In addition to these existing subsidies, the government can consider additional options including a review of training and administrative requirements and financial assistance for the creation of joint training centres.

Experiences from other OECD countries illustrate how a review of training and administrative requirements can balance employer and apprentice interests and keep training requirements up-to-date. For example, Norwegian advisory bodies of vocation education and training composed in principle of employer and employee representatives can call for reviews of training lengths or curricula that entail the development and approval of new curricula (Kis, 2016[62]). Regular reviews can ensure that apprentice’s occupational profiles respond to technological change. For example, Denmark and Germany recently carried out review initiatives to respond to adapt apprenticeships for the needs of advanced manufacturing (Eurofound, 2018[63]). Korea’s own experience demonstrates how important it is to involve employer representatives in designing apprenticeships: The 1990s attempt to establish apprenticeships failed in part due to a lack of involvement of employers’ organisations.

A further option to reduce training costs is to create training centres or alliances. Training centres could, for example, be located on polytechnic campuses (Jones and Fukawa, 2016[61]). In fact, a few sector councils are already active in this regard: they search for firms interested in being involved, develop programmes and operate joint training centres (Ryu, 2017[64]). Korea also has a precedent for pooled training: the SME Training Consortium Program created in 2011 and since renamed the National Human Resources Development Program. Through the programme, the government financially assisted groups of SMEs that hired a joint training manager to train their existing workforce (Lee, 2016[65]). Despite these consortia and proportionally higher subsidies, SMEs still offer less training (OECD, 2017[15]).

Multiple OECD countries have models of joint apprenticeship training. In some, apprentices can train with multiple companies. For example, in Australia, group training organisations formally employ apprentices and hire them out to one or more companies. This way, apprentices can acquire a broad range of skills. Austrian training alliances facilitate exchanges or unilateral transfers of apprentices between companies. In other countries, joint training centres directly offer part of the training. For instance, in Switzerland, in addition to theoretical education complementary to what vocational schools teach, autonomous training centres provide the initial practical training before apprentices move on to company-based training (Kuczera, 2017[66]).

In Korea, Sector Councils can continue playing a role in exploring options for joint training models. Depending on local and sectoral conditions, joint training alliances could even involve co-operations between small and large companies. These could be particularly useful if several conditions are met: First, where SMEs are important suppliers for large companies, large companies have an interest in ensuring that SMEs have an educated workforce. Second, large companies need to be able to fulfil the training needs of the SME apprentices. At the same time, the occupational profile of workers with completed apprenticeships needs to be sufficiently distinct from the worker needs of the large companies. Otherwise, SME apprenticeship providers would have to fear that large companies poach their newly qualified workers.

2.3. Ensuring quality tertiary education

While the benefits of a college or university education should not consist of material gains alone, most (prospective) students would probably agree that studying longer should not leave them financially worse off. Even so, Chapter 1 illustrated that the financial pay-off from higher education is negative for a substantial share of university and college graduates. The following parts describe contributing factors to low pay-offs from tertiary education and the government’s efforts to address these factors, and propose further reform possibilities.

2.3.1. Korean tertiary education institutes vary greatly in quality

The quality of Korea’s tertiary education is not as high as its primary and secondary education and it varies strongly across institutions. In 2013, Korea ranked 25th out of 60 countries in overall educational competitiveness but only 41st in university education (Kim, 2016[67]). The best universities excel across a broad range of subjects. Their students are more frequently employed than students from lower-ranked institutions are. At lower-ranked institutions, students have access to fewer faculty members and are more likely to drop out (Lee, Jeong and Hong, 2014[68]). However, it is difficult to assess whether the differences are larger than in other OECD countries. In England, for example, experimental data from the Longitudinal Education Outcome dataset suggest that graduates from the lowest-ranked institutions are employed or advance to further education at rates equal to graduates from the highest-ranked institutions (Department of Education, 2017[69]). In Italy, in contrast, the employment rates of humanities graduates vary strongly across faculties even when taking into account their parents’ educational achievement and occupational prestige (though not the students’ abilities) (De Battisti, Nicolini and Salini, 2008[70]).

The balance between different types of institutions is shifting. Between 2000 and 2012, lower-ranked universities expanded their enrolment, at the expense of lower average admission scores among their admitted students (Lee, Jeong and Hong, 2014[68]). Enrolment at higher-ranked institutions has remained relatively constant while the number of colleges has declined (Jones, 2013[1]). Moreover, universities now more frequently offer degrees traditionally conferred by colleges, and colleges do the same with traditional upper secondary degrees. An example is a four-year bachelor degree in cosmetology.

Stark quality differences across higher education institutions generate important costs for Korean youth and the society as a whole. In particular, upper secondary students spend large amounts of time and money to prepare for admission to higher education. Some secondary graduates even prefer to sit out a year so they can re-take the College Scholastic Aptitude test and attend a higher-ranked institution. The system encourages students to focus on getting into the ‘best’ possible institution rather than fully considering all alternatives, hereby contributing to the skill mismatch.

While graduates from lower-ranked tertiary institutions have poorer outcomes, including lower average earnings (Yeom, 2016[71]; Jung and Lee, 2016[72]), it is unclear how much lower student ability, lower institutional quality (such as poorer teaching, less individualised attention and less career counselling) and reputation effects respectively contribute to these worse outcomes. Certain studies on the United Kingdom and the United States (Broecke, 2012[73]; Hoekstra, 2009[74]) suggest that the earnings impact of attending a more selective institution persists even when the ability of students are taken into account, pointing to at least some quality or reputation effects. Others, however, do not find the same result, except for students from low-income families (Dale and Krueger, 2002[75]).

In recent years, the Korean government and individual institutions have undertaken efforts to create more holistic admission criteria and ensure the quality and relevance of college and university teaching. The next sections describe these efforts and suggest further possible initiatives.

2.3.2. The Korean government seeks to align tertiary education offers and market demands

Creating a higher education system in which institutions distinguish themselves more by their educational focus than by their rank and in which quality is more uniform can lower the singular focus of upper secondary students to gain admission to the most prestigious institutions and create a better match between graduates’ skills and labour market needs.

Since a less quality-stratified system can only be achieved over the long term, the Korean government already introduced measures to reduce the reliance on the standardised aptitude test and school records in college or university admission. Since 2008, tertiary institutions may use interviews, essays and tests as additional selection criteria (Choi and Park, 2013[76]). A side effect appears to be that top universities increasingly select students from certain autonomous schools and schools in affluent areas (Jin, 2016[77]). One possible reason is that graduates from autonomous schools, which unlike other schools can select their students and can thus pick the brightest ones, have higher academic ability (Yoon, 2015[78]). Other possible reasons are social prestige, more school resources and higher investments in private tutoring.

General initiatives to increase the quality of tertiary education have focused on reducing the number of students at low-quality colleges and universities and increasing transparency and accountability. The 2014 Action Plan for University Structural Reform aimed to lower college and university quotas by 160 000 between 2015 and 2023. Under this plan, very low-quality higher education institutions have to shut down and low-ranked institutions are forced to accept fewer students (Kim, 2016[67]). Moreover, colleges and universities now have to report their graduate employment rates. Prospective students can consult these rates online (Korean Council for University Education, n.d.[79]). The intention behind this requirement is to increase institutions’ performance through guiding students and directing funding towards the more successful ones (Kis and Park, 2012[80]). However, as most Korean tertiary institutions are private and primarily fund themselves through tuition fees, the funding mechanism’s leverage is limited.

2.3.3. Quality assurance in tertiary education can be strengthened

The variety of initiatives named above underlines the desire of the government to make it easier for young people to transition from college or university to the workplace and for businesses to find workers with the skill sets they need. Yet while single initiatives can be worthwhile, policies boosting the quality and labour market relevance of tertiary education overall can bring even more benefits.

Continue to broaden university entry requirements

There is no one best practice on how university admissions should weight achievements in upper secondary education, standardised aptitude tests and other criteria. Each decision has downsides and upsides in terms of efficiency (selecting the ‘most able’ students), equity (taking into account systematic (dis)advantages of different groups) and the admission system’s administrative costs. Nevertheless, it is preferable to avoid criteria that require considerable investments from students without helping them to perform better in their studies or work life (Hoareau McGrath et al., 2014[81]).

The Korean government can therefore continue to support universities in using alternative admission standards rather than the standardised aptitude test. One issue appears to be that the public perceives the alternative admission standards as the less respected easy way in (Diamond, 2016[82]). To address this perception, a starting point could be to undertake systematic analyses on the relative academic and labour market success of students admitted through different mechanisms. Such analyses could reveal how high the predictive capability of the standardised aptitude tests is at different institutions; and influence public perceptions. Colleges and universities where the predictive value of test scores on performance is low could consider reducing or eliminating their role in admission decisions. In the United States, several colleges – including highly ranked ones - have made SAT scores optional, in accordance with a 2008 recommendation (National Association for College Admission Counseling, 2008[83]). This change lead to more applications by traditionally under-represented students without compromising graduation rates (Syverson, Franks and Hiss, 2018[84]).

Strengthen quality and labour market relevance through reporting

One of the options to assure the quality of tertiary education is to set minimum performance standards and to close down institutions that do not fulfil them. As described above, the Korean government is not shying away from doing so. However, if it were to decrease quotas too drastically or to close too many colleges or universities, it would have to fear a backlash. Families might be concerned that the country was returning to a system where few students have access to tertiary education. Moreover, the approach would raise the question as to whether the relevant regulatory authority is truly able to identify the institutions that do not serve the needs of their current and future students.

The Korean government is also using a second quality improvement instrument: it directs more funding to institutions that perform well or that shift to degrees that are more ‘employable’. But as noted above, the impact of these initiatives are limited by the fact that the majority of tertiary institutions are private and government funding represents a small share of their budget. Moreover, performance-based funding may have disadvantages even in contexts where they are likely to be more impactful (Kis, 2005[85]). First, it is difficult to measure the quality of teaching. Even poor labour market outcomes can be a mistaken indicator: graduates may have received a high-quality education relevant to the students’ chosen occupation, but there may be a temporary slump in the demand for these graduates either within a given region or nation-wide. Second, colleges and universities can be tempted to fudge their numbers. Third, depending on the selected performance indicators, the policy may incentivise colleges and universities to change the degrees they offer in unintended ways. For example, in the United States, performance funding created more short degrees that were easier and quicker to complete but that had limited use on the labour market (Li and Kennedy, 2017[86]). Performance-based accountability across US states does not appear to have improved either graduation rates or research output (Shin, 2010[87]). Fourth, cutting funding to under-performing institutions may precisely prevent them from making necessary improvements.

A less drastic third alternative that can nonetheless improve quality of institutions over time is the ‘gainful employment’ regulation, as is used in the United States: students are unable to take out federal loans to attend institutions where the ratio between students’ debt and their later earnings is too unfavourable (Cellini, Darolina and Turner, 2016[88]). Presumably, this will incentivise students to select universities with better labour market records. In 2011, the Korean government already implemented a similar programme, although the criteria were related to the universities’ management rather than labour market outcomes (Kim, 2011[89]). With nearly a third of higher education students receiving a need-based grant and more than one-sixth taking out a direct loan (KOSAF, 2017[90]), this approach could be quite influential in improving the quality of universities. However, it should adjust for the mix of programmes to not penalise quality institutions specialising in degrees with less labour market demand.

A fourth possibility is to steer students to institutions with better labour market outcomes through requiring colleges and universities to publish more relevant information. Reporting requirements for Korean higher education institutions could be expanded from alumni employment rates to include average earnings. The ‘Launch my Career’ websites developed by the American Institutes for Research, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Gallup and the governments of Colorado, Tennessee and Texas are a positive example. The websites provide information on the average cost of attending, time to graduation and twenty-year earning gains for each institution and degree (American Institutes for Research, 2018[91]). To create a similar website for Korea, significant additional data would have to be collected, even if tracking earning gains over a shorter time period, such as five years, would be sufficient. But if prospective students started to shun institutions with decent employment rates but below-average earnings, the potential pay-off could be substantial. One possible drawback is that recent changes in universities’ teaching methods, collaboration with industries and job placement support are not immediately reflected in long-term labour market outcomes, and would need to be reflected in the information provided on the website.

Focalise institutions’ profiles and further co-operation with employers

Closing institutions, making funding dependent on performance and increasing reporting requirements aim to push universities to improve their performance and re-direct students to better-performing programmes. However, they do not necessarily improve the employability of students and the match between supply and demand of skills. Initiatives that may be able to address these issues include improved co-operation with employers and a sharpened profile for colleges through the implementation of NCS-based curricula.

In recent years, the Korean government has already launched a number of initiatives aiming to create curricula that are responsive to industry needs and to facilitate the school-to-work transition:

National Competency Standards: Certain colleges and universities are developing degree programmes based on competency standards (see Box 2.1). The large volume of articles in Korean professional journals on the creation of such curricula suggests that the process is labour- and time-intensive.

Convergence Technology Campus: This offer affiliated with Korea Polytechnic offers non-degree programmes to young tertiary graduates unable to find employment in their original field. Professors coming directly from industry retrain them in one of three areas (data/life sciences/embedded systems). During the intensive ten-months programme, participants receive tuition aid and a stipend.

Leaders in Industry-University Co-operation: The initiative (launched in 2012) clusters research projects and aims to tailor education to local needs. Participating higher education institutions can for instance receive funding to buy equipment needed to incorporate training adjusted to specific companies’ needs (OECD, 2017[15]; Chung, 2012[92]).

Program for Industrial Needs-Matched Education: The Ministry of Education introduced the programme in 2016. It aims to restructure nearly two dozen universities that are supposed to offer fewer degrees with poor labour market prospects. The programme’s funding represents more than half of some of the participating institutions’ budgets. In practice, most participating institutions planned to expand engineering and science and shrink or close humanities departments. Critics noted that the planning and transition periods were too short and that demand for engineering and science graduates is over-stated, ultimately implying that the program could even increase skill mismatches (Do, 2016[93]; Lee and Byeon, 2016[94]).

Apprenticeships: Even though the majority of apprenticeships are at the upper secondary level, some colleges and universities also teach apprentices (Jones and Fukawa, 2016[61]). In addition, the ‘uni-tech’ programme combines practical training during three years in upper secondary education and two years in college. Graduates have an employment guarantee with a participating business (Lee et al., 2017[95]).

To ensure the labour market relevance of degrees, colleges and universities should continuously review their course offerings in light of evidence on in-demand and shortage skills. They can gather evidence from enterprise and graduate surveys, qualitative forecasts such as Delphi studies, scenario-based predictions or from labour market indicators such as relative wage growth and unemployment rates as presented in the OECD Skills for Jobs Database (OECD, 2018[96]; Galán-Muros and Davey, 2017[97]). For example in Sweden, higher education institutions rely on Statistic Sweden’s skill needs forecasts to plan how many places they are going to offer in different programmes (OECD, 2016[98]). These forecasts predict future skill needs and demands based on an analysis of the current education system and projections about the development of total employment demand, different industries, occupational trends and educational demand (Statistics Sweden, 2017[99]).

The government has different options for incentivising universities to consider skill demand when deciding how many spots to offer in different programmes. A number of OECD countries including Australia, England and Lithuania provide subsidies for programmes preparing for certain shortage occupations. In some cases, however, the government intervenes directly. For example, in 2014 Denmark introduced caps for programmes whose graduates were significantly more likely to be unemployed. In Poland, programme quotas can rise more quickly than average if there is a ministerial decision that a field is a strategic priority for national development (OECD, 2017[100]).

Once promising skill areas and occupations are identified, tertiary institutions need to ensure that students pursuing degrees leading up to those occupations learn the necessary skills. If employer organisations actively contribute to developing and updating the National Competency Standards (see Box 2.1), these standards can be an appropriate basis for part of the curriculum design. Even degree programs not leading up to a particular occupation can benefit. For instance, graduates in humanities or social sciences often have jobs for which they need strong written and oral communication skills. Curricula can hence be evaluated according to how well they allow students to develop these and other relevant skills. Nevertheless, curricula should not be based on competency standards alone. Even occupation-specific degree programmes should impart broader theoretical and practical skills than might be strictly necessary for the particular occupation. Workers with a broader knowledge and skills may find it easier to retrain later in life should their occupation drastically change or disappear.

Employer involvement with tertiary institutions can ensure that students are prepared for the labour market, but requires efforts to be sustained. The Korean government and different institutions have various programmes to encourage partnerships between educational institutions and employers, but collaborations are often short-lived (Choi, 2013[101]). Evidence from several European countries suggests one possible way to make collaborations more durable: companies that cooperate with universities on multiple activities tend to be more engaged (Melink and Pavlin, 2014[102]). This evidence suggests that universities should try to create multiple engagement channels with employers. These can include internship programmes, employer advisory boards to jointly design curricula, research and teaching co-operation, and others (Galán-Muros and Davey, 2017[97]). One example from Korea is Korea Polytechnic University’s co-operation with more than 3 000 SMEs. In addition to worksite placement, the co-operation also provides companies access to experimental equipment (Korea Polytechnic University, 2016[103]).

Integrate entrepreneurship education into tertiary curricula

Integrating entrepreneurship education into their curricula is a further way through which colleges and universities can prepare students for the world of work and stimulate the economy. New company creation can drive economic and job growth and represents a viable alternative to dependent employment for young labour market entrants.

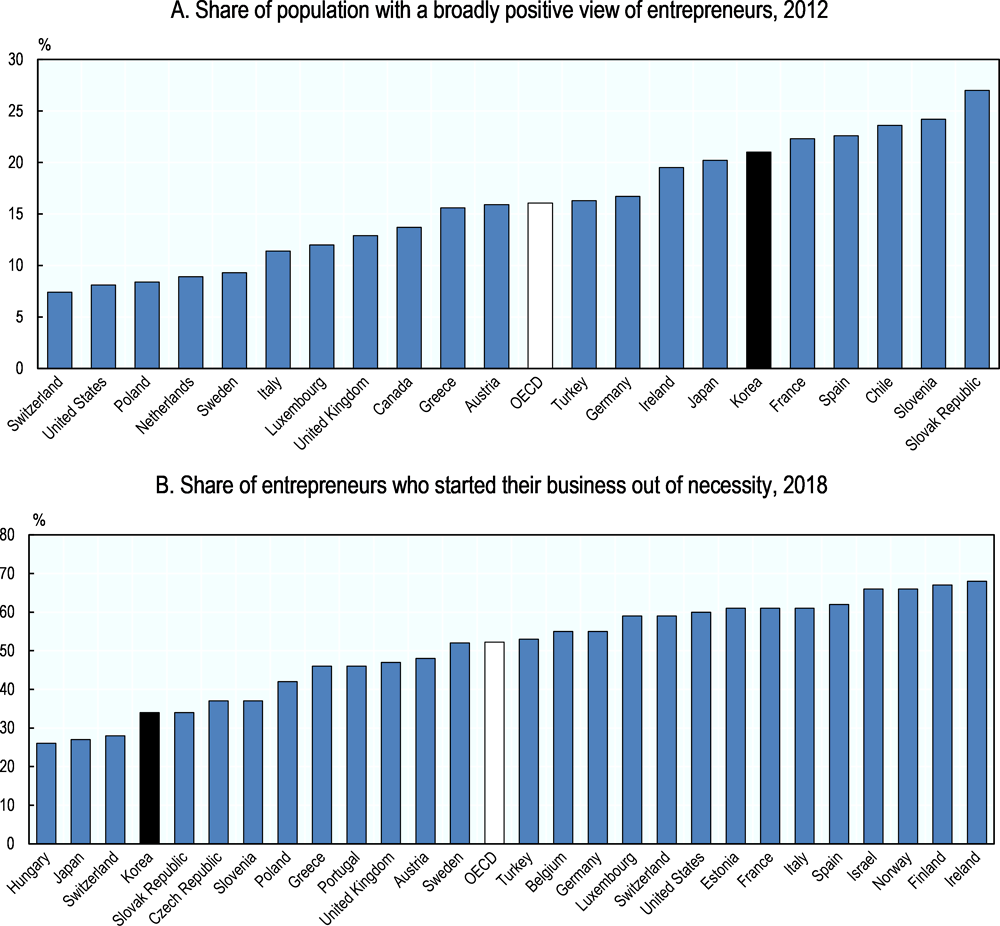

Currently, the role of entrepreneurship in Korean society is more limited than appears desirable. Many of the self-employed are older workers who lost their job and have little or no social protection to rely on. Both a cause and an effect of this concentration of self-employment among older workers, Koreans view entrepreneurs less positively than is the case in most other OECD countries (Figure 2.7, Panel A). Another effect is that a comparatively high share of Korean entrepreneurs became self-employed because they were not able to find another job (Figure 2.7, Panel B). This type of ‘necessity entrepreneurship’ has much less positive effects on economic growth than ‘opportunity entrepreneurship’ (Acs, 2006[104]).

Figure 2.7. Entrepreneurs in Korea are not as well regarded and as opportunity-oriented as elsewhere

Source: OECD (2016[33]), OECD Economic Surveys: Korea, and Bosma and Kelly (2018[105]), Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2018/2019 Global Report.

More young people express an interest in starting their own company than those that end up doing so. In the 2015 Youth Panel Survey, around 6% of tertiary students aged 20-29 stated that the type of company they wanted to work for was their own, but only 3% of workers in the same age group were actually self-employed. Overall, the share of self-employed among workers in that age group is among the lowest third of OECD countries, but higher than for example in Norway or the United States.

While entrepreneurship education cannot eliminate all obstacles that prevent young people from realising their entrepreneurial aspirations, it can equip students with the skills to surmount them. In essence, entrepreneurial education is supposed to equip students with the competencies to identify entrepreneurial opportunities and to start and run a business. These competencies include attitudes such as entrepreneurial passion and perseverance, knowledge to identify promising ideas, and practical skills such as marketing and creating a business plan (Lackéus, 2015[106]).

The Korean government has realised the importance of entrepreneurship education. It is now mandatory in Korean primary and secondary schools (OECD, 2016[33]). At the tertiary level, the Ministry of SMEs and Start-ups contributed to creating entrepreneurship graduate schools (Byun et al., 2018[107]) and the Korea Entrepreneurship Foundation. Among other activities, the foundation collaborates with universities’ entrepreneurship centres in creating teaching materials

Prior experiences from other OECD countries can help Korean universities design impactful teaching content related to entrepreneurship, by making entrepreneurship education accessible across disciplines; balancing theory and practice; and monitoring, evaluating and adjusting entrepreneurship education (see Box 2.2).

2.4. Supporting companies in altering recruitment practices

Inefficient recruitment practices can exacerbate skill mismatches if they force candidates to invest a lot of time in preparing their application and do not necessarily attract the best match for the job.

2.4.1. Companies rarely use competency-based hiring

Competency-based hiring is still rare in Korea. A survey of nearly 450 human resources managers from private enterprises and public institutions found that few companies use job posting with detailed information on required competencies or carry out structured job interviews. At the same time, many managers judge these interviews to be the best predictor for job performance. The majority of interviewees had also never heard of the National Competency Standards (Chang, Jung and Chang, 2015[108]). Companies that have heard of the Standards often do not rate them highly (Lee, Ra and Ryu, 2016[51]). One reason may be that industry involvement was relatively passive and that there are insufficient review mechanisms (Chio et al., 2015[52]).

Instead, many large employers and public institutions in Korea, like in Japan, have their own recruitment exams, with a strong focus on written tests. They often recruit groups of hires rather than hiring for a particular position. Small and medium-sized employers, in contrast, are not able to rely on the same selection mechanisms. The different standing and unequal work conditions in SMEs and large enterprises (see Chapter 3) encourage recent graduates to invest months preparing for employment exams rather than launching into the working life. Many candidates prefer to work for a large enterprise than for an SME, even if they end up being over-skilled, hereby contributing to the skill mismatch.

Box 2.2. OECD lessons for the integration of entrepreneurship education into tertiary education

Make entrepreneurship education accessible across disciplines

Business schools tended to be the first university departments within universities that taught entrepreneurship-related content, but universities in different OECD countries are increasingly opening up relevant courses to students in other disciplines. For example, the Limerick Institute of Technology in Ireland offers the “Market-Link Entrepreneur” programme consisting to a series of business workshops to students from all faculties (OECD/EU, 2017[109]).

Balance theory and practice

As in other realms of education, student learning benefits from having a balance between theoretical and practical teaching approaches and from experiential learning. Students may be more likely to eventually take the leap into entrepreneurship if they learn to develop and implement ideas through practical experiences such as role playing and business plan competitions. Where possible, involving employers in these activities can provide more practical insights and further strengthen ties between universities and companies and between students and their potential future employers (or customers) (OECD/EU, 2017[110]).

Monitor, evaluate and adjust entrepreneurship education

Teaching entrepreneurship-related content is a recent innovation at most colleges and universities. This means that knowledge about ideal teaching styles and about outcomes are still limited. Carrying out evaluations and making adjustments when necessary can ensure that the quality of these programmes reaches its full potential. Internationally validated assessment tools such as OctoSkills, the EU’s Entrepreneurial Skills Pass or LoopMe could be adjusted to the Korean context and integrated into such evaluations (OECD/EU, 2018[111]). Similar to the role of the Danish Foundation for Entrepreneurship, a central body such as the Ministry of SMEs and Start-ups or the Korea Entrepreneurship Foundation could coordinate or carry out these monitoring and evaluation activities.

2.4.2. National Competency Standards may help job candidates exhibit their skills and companies lower their recruitment costs

The Korean government has expanded competency-based hiring in the public sector. Under the new system, hiring managers create job description that clearly define required competencies. Candidates do not have to present credentials unrelated to these requirements. This new approach has positive pay-offs: for example, when candidates did not have to provide English test scores for a position for which these were irrelevant, more upper secondary and college as opposed to university graduates were hired than was typically the case. From the employer perspective, the most positive outcome was that first-year turnover declined (The Korea Herald Editorial Report, 2016[112]). Evidence from a project focused on unemployed youth in New Mexico also suggests that competency-based hiring reduced turnover and hiring costs (Carlton and Blivin, 2016[113]).