Improper household disposal of unused or expired medicine can contribute to pharmaceutical leakage into the environment. This chapter reviews the estimated amounts and disposal practices of unused or expired medicine in OECD countries.

Management of Pharmaceutical Household Waste

3. Household disposal and collection of unused pharmaceuticals

Abstract

3.1. Amount of pharmaceutical waste

The amount of medicine waste generated is affected by prescription and consumption practices. Demographic, epidemiological and lifestyle changes such as an ageing and growing population, the rise of chronic health conditions and the availability of inexpensive generic treatments and changes in clinical practice have been key drivers for increased pharmaceutical prescription and usage in OECD countries (OECD, 2021[1]).

The increase in the consumption of pharmaceuticals likely also increased the amount of UEM. Between 2000 and 2019, consumption of anti-hypertensive drugs in OECD countries increased by 65%, lipid-modifying agents increased by a factor of nearly four and the use of anti-diabetic as well as anti-depressant drugs doubled (OECD, 2021[1]).

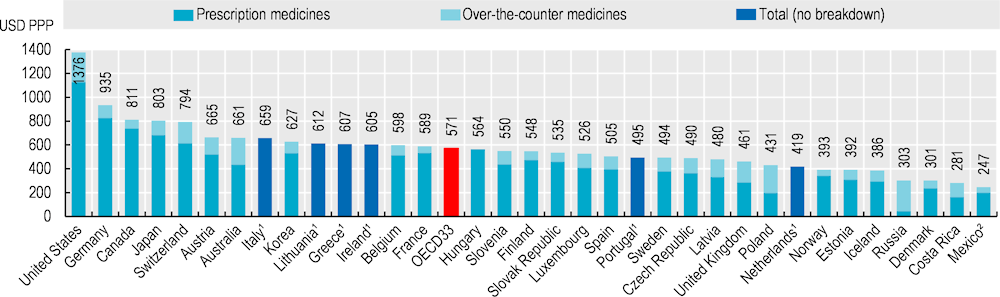

Pharmaceutical consumption per capita strongly varies between OECD countries. Expenditure data can provide a rough proxy for the amount of drugs in circulation and the amount of medicine waste that may be generated. In 2019, spending for retail pharmaceuticals averaged USD 571 per person across OECD countries, adjusted for differences in purchasing power. Cross-country differences are marked, with spending more than double the average in the United States, followed by Germany and Canada and lowest in Mexico and Costa Rica (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. Expenditure on retail pharmaceuticals per capita, 2019 (or nearest year)

Note: 1) Includes non-durable medical goods (e.g. first aid kits and hypodermic syringes), resulting in an overestimation of around 5‑10%. 2) Only includes private expenditure.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2021.

There are many reasons why drugs can become waste:

No-effect, adverse reactions and/or therapy change: Prescribed drugs prove to be unsuitable for treatment and are consequently abandoned, or the treatment is changed.

Non-adherence: Patients have a poor record in taking their medication.

Recovery or deceased: Patients recover more rapidly than foreseen or decease.

Stockpiling and/or expiring: Patients may stock pharmaceuticals for ‘just-in-case’, which leads to medicines reaching their expiry date before being completely utilised (in particular over-the-counter pharmaceuticals and non-prescription drugs). Stockpiling and potential expiry is not only an issue in households but also in public buildings, hotels, marine vessels, societal institutions, prison systems and military bases where drugs are commonly stored in case of emergencies but only used infrequently (Ruhoy and Daughton, 2008[77]).

Prescription or purchasing error: Patients may be prescribed or may purchase the wrong pharmaceuticals. Over prescribing can also lead to medicine waste.

Estimates of the share of medication becoming waste vary from 3% to as high as 50%. According to the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA), 3-8% of the medicinal products sold remain unused.1 In Finland, it has been estimated that 3-4% of medicines sold go unused (by medicine price) (Finnish Pharmacy Association, 2016[78]). Law et al. (2015[13]) assume that 42% of dispensed medicines remain unused. In another US survey, six out of ten patients that got opioid painkillers prescribed, report having leftover pills at home (Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2016[79]). Bound and Voulvoulis (2005[80]) assume 50% wastage for the United Kingdom and Musson and Townsend (2009[81]) estimate that 11% of prescribed medicines become waste.

The volume of UEM generated is difficult to trace, but a study commissioned by the French PRO Cyclamed estimated that households in France disposed of 17 600 tonnes of UEM or 259 g per capita in 2018 (2019[82]). Overall, UEM amounts up to about 0.05% of overall household waste in France (Eurostat, 2020[83]). Musson and Townsend (2009[81]) measured a concentration of 8.1 mg APIs per kg of MSW in Orange County, Florida, which they considered the lower bound of possible pharmaceutical contamination in MSW.

3.2. Household disposal practices and collection rates among OECD countries

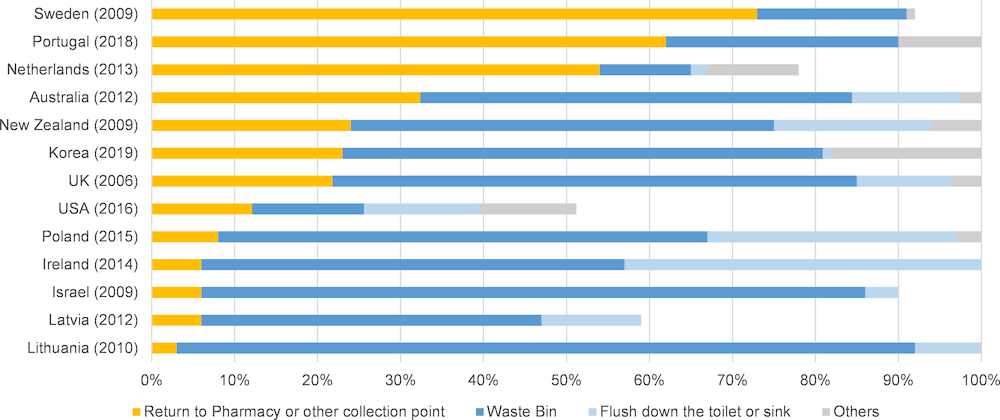

Household disposal practices vary among (OECD) countries, critical drivers being the availability of drug take-back systems and the public awareness of these systems. Whilst a share of UEM is returned to pharmacies and collection points, disposing of UEM in solid waste bins or down household drains remains common practice in most OECD countries. In some OECD countries, where most MSW is incinerated in state-of-the-art facilities, disposal via solid household waste is one of the recommended disposal routes (e.g. Germany). Disposal via the toilets and sinks, is commonly advised against.

Figure 3.2. Household disposal practices of unused or expired medicine in selected OECD countries

Note: Year of study indicated in brackets. Some surveys included responses of storage for later use. These were excluded in this graph, which leaves some entries <100%. “Others” includes inter alia household burning or handing to other users.

Source: Australia (Amanda J. Wheeler, Fiona Kelly, Jean Spinks, 2016[84]); Ireland (Vellinga et al., 2014[85]); Israel (Barnett-Itzhaki et al., 2016[86]); Latvia (Methonen et al., 2020[87]); Korea (DSI, 2019[88]);Lithuania (Kruopienė and Dvarionienė, 2010[89]);The Netherlands (Reitsma et al., 2013[90]); New Zealand (Braund, Peake and Shieffelbien, 2009[91]); Poland (Methonen et al., 2020[87]); Portugal (Winning Scientific Management, 2018[92]); Sweden (Persson, Sabelström and Gunnarsson, 2009[93]); UK (Bound and Voulvoulis, 2005[80]); USA (Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2016[79]).

Sweden, Portugal and the Netherlands seem to achieve the highest shares of respondents stating to return UEM to pharmacies or collection points (more than 50%). In addition, Cyclamed (2019[82]) estimates that 62% of all UEM are returned to pharmacies in France. In Lithuania, Israel and United Kingdom most participants stated to dispose UEM in household waste bins (Figure 3.2). Alnahas et al. (2020[94]) provide a comprehensive review of the literature on household disposal practices of unused medication, where additional results can be found for non-OECD countries.

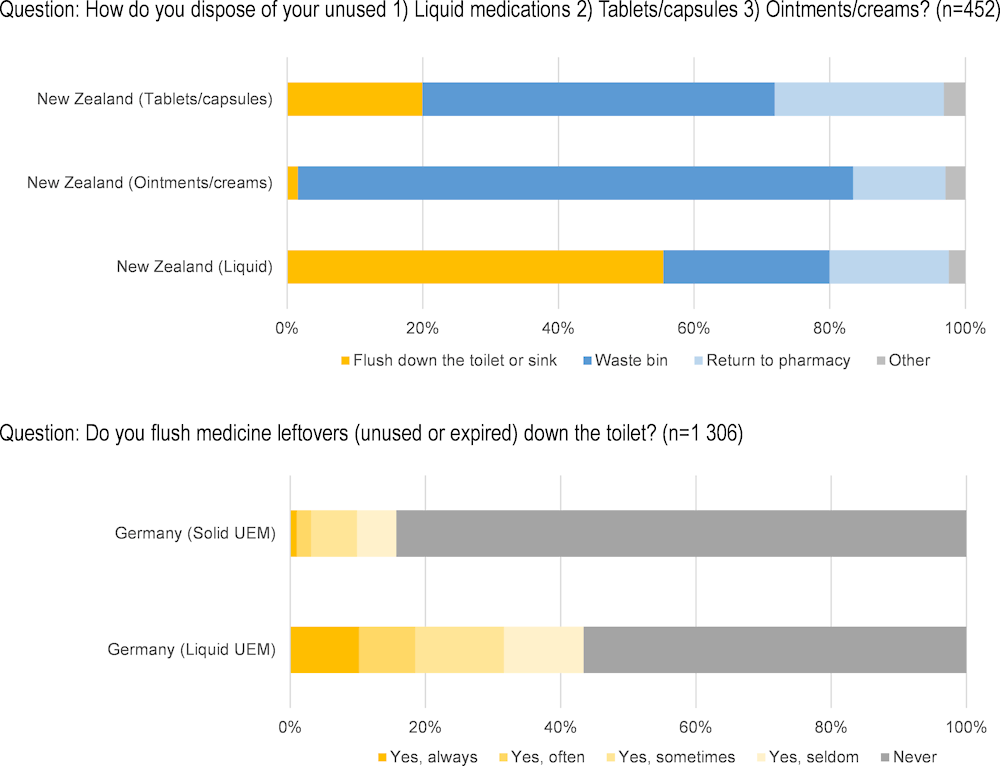

Disposal practices differ depending on the type of medicine. Liquids tend to be more often discharged in sinks or toilets, whereas solids (e.g. tablets and capsules) and semi-solid pharmaceuticals (e.g. creams and ointments) tend to be more often disposed of in solid household waste (Figure 3.3). Additionally, medicines considered to be more harmful, such as antibiotics, were more often returned to a pharmacy than over-the-counter products (e.g. cough medicine) (Tong, Peake and Braund, 2011[95]; Braund, Peake and Shieffelbien, 2009[91]; Paut Kusturica, Tomas and Sabo, 2016[96]).

Figure 3.3. Household disposal practices according to medicine type: the case of New Zealand and Germany

In some OECD countries, home backyard burning of UEM together with other household waste also remains occasional practice in rural areas. For instance, in a survey of Lithuanian countryside households, 50% of the respondents reported burning medication (Paut Kusturica, Tomas and Sabo, 2016[96]). Whilst this practice can be considered rare in OECD countries, it may be more common in rural areas in emerging economies. Leakage into the environment via household solid waste or the drainage are also likely to be higher in countries with less developed waste management systems, especially if collected waste is destined for uncontrolled dumpsites or households.

Note

← 1. A recent report cites this value (BIO Intelligence Service, 2013[7]), which was initially given by a representative of the pharmaceutical industry, during the Workshop on the presence of medicinal products in the environment held in Brussels by BIO IS on behalf of EAHC, on 19 September 2012.