Paraguay has made considerable progress in reducing poverty and improving living conditions. To bolster its achievements and further advance social development, the country must create a comprehensive social protection system that can improve living conditions for the most vulnerable people, foster everyone’s inclusion in the country’s economic development and provide vital risk-management tools for the whole population. This implies facing the challenges of coverage, funding and governance throughout the social protection system and in each of its facets, especially the pension system. This chapter presents the main conclusions from the Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay on social protection and puts forward a more specific action plan for pension reform.

Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay

Chapter 3. Pension system reform as a pillar of the overhaul of social protection in Paraguay

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

In recent years, Paraguay has improved its citizens’ living conditions and standard of living considerably. Income poverty has dropped to nearly half its turn-of-the-century levels. However, poverty and inequality remain high. The integration of many people into the labour market and the modern economy remains challenging. In addition, supportive policies are needed to sustain the emerging middle class (OECD, 2018[1]).

Bolstering achievements and continuing social progress require the country to overhaul social protection thoroughly to change it from a group of programmes into a truly integrated system. Low rates of formal employment (35% in 2015) limit the reach of contributory social security. Expansion of social assistance programmes has made it possible to close part of the coverage gap but has also created a multitude of programmes that, regardless of their individual merit, suffer from a lack of co-ordination that hurts their efficiency.

Paraguay has made a firm commitment to social protection. In early 2019, the country approved the development of a social protection system (SPS). This system co-ordinates all of the state’s social protection activities. Is also defines social protection broadly, going beyond the emphasis on poverty reduction of past initiatives.

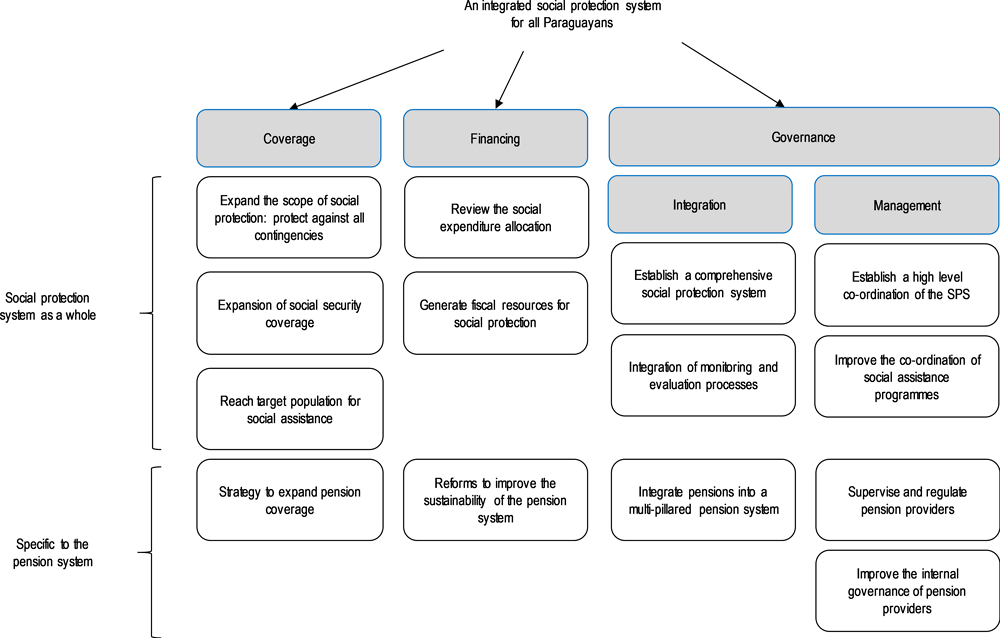

To create a comprehensive social protection system, the country must overcome four big challenges. First, expanding the entire system’s coverage to the whole population, especially to the most vulnerable and to hitherto unprotected populations. Second, ensuring funding for each component of the system by making more resources available for social protection, by improving their use, and through reforms to keep the system’s key elements sustainable. Third, taking steps towards truly integrating the policies and programmes of the existing fragmentary system. Last, establish effective governance of social protection through leadership, clear distribution of tasks, and strategic and operational co-ordination.

These challenges apply to the social protection system as a whole and to each specific component. This chapter starts with an overview of the priority areas for action on social protection, based on the recommendations put forward in Volume 2 of the Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay (OECD, 2018[2]). The rest of the chapter details an action plan for pension reform with specific steps to address the main challenges in the specific area of pensions.

Social protection as a key element of inclusive development in Paraguay

In recent years, social policy in Paraguay has focused on addressing poverty and the most extreme forms of deprivation and vulnerability. The National Development Plan for 2030 puts special emphasis on fighting poverty, a key priority in the social development targets, which also include developing high-quality social services and participatory local development, and promoting a suitable, sustainable habitat. This high-priority focus helped establish significant social policy tools, including poverty-reduction programmes such as Tekoporã and non-contributory pensions including notably the Adulto Mayor (Older Adult) pension.

In developing a social protection system (SPS), the country has embraced a broader view of social protection. The country’s Social Protection System rests on three pillars: (i) social integration, (ii) labour market and productive integration, and (iii) social welfare. Social integration includes policies that aim to improve basic quality-of-life conditions as well as universal policies such as education and health. Productive integration involves generating income through decent work. Social welfare refers to tools for lifelong risk management and risk reduction. This vision is based on rights guaranteed by the Paraguayan constitution (health, education, workers’ rights, housing, social security) and other regulatory documents.

Diagnosis and priority actions for social protection

Analysis in Volume 2 of this Multi-dimensional Review (OECD, 2018[2]) indicates that Paraguayan social protection as a whole is facing challenges that can be grouped into three broad categories: (i) coverage, (ii) funding and (iii) governance. In governance, one can distinguish between, on the one hand, management of the whole system and of its parts, and on the other hand, integrating this highly fragmented system. These issues apply to every component of the social protection system and to the system as a whole.

Figure 3.1. Major challenges and priority areas of action for social protection in Paraguay

Source: Authors’ work.

Coverage is improving, but still insufficient

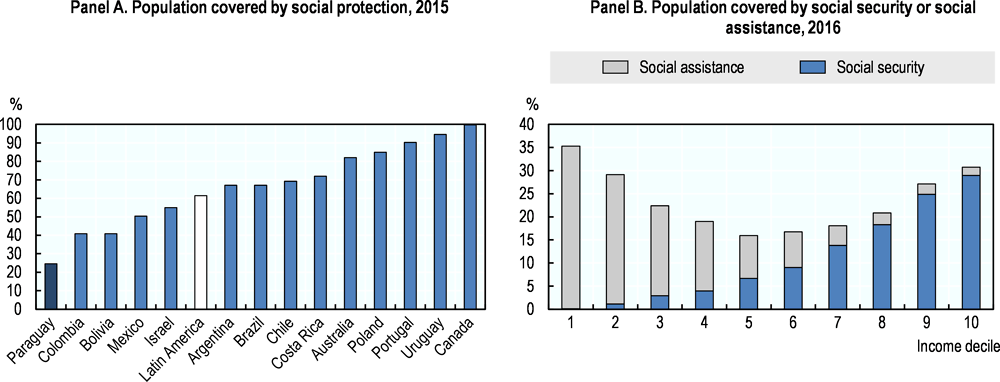

Social protection does not yet reach all citizens who need it. Social protection programmes cover a quarter of Paraguayans, which is low among countries in Latin America. If the definition is expanded to include anyone whose household receives any type of benefit, the coverage rate is higher (63% according to the World Bank’s ASPIRE database). This is mainly because programmes providing school meals (and distributing school supplies) have broad coverage, serving 85% of children in the first through sixth grades (World Bank, 2018[3]).

Figure 3.2. Social protection does not yet cover all Paraguayans

Note: Effective coverage of social protection is measured as the percentage of people actively paying into a social security regime or who receive at least one benefit (from any contributory or non-contributory programme, excluding healthcare benefits). Panel A: 2016 for Paraguay, 2015 or most recent year available for other countries. Panel B: Social assistance includes conditional cash transfers (Tekoporã), in-kind benefits (food) and non-contributory pensions (ex gratia pensions, pensions for veterans and their survivors, military personnel or police, and the Adulto Mayor pension). Social security comprises contributions to a social security regime and the collection of contributory pensions.

Source: Panel A: Data for Paraguay are based on the Encuesta Permanente de Hogares (Ongoing survey of households) (DGEEC, 2017[4]) and the other countries’ data come from (ILO, 2017[5]). Panel B: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Encuesta Permanente de Hogares (DGEEC, 2017[4]). See OECD (2018[2]).

There have been major advances in coverage. The population with effective access to primary healthcare rose from less than half in 2000 to more than 80% in 2016. The creation and expansion of non-contributory programmes such as Tekoporã and Adulto Mayor have helped narrow the coverage gap considerably, especially among older adults (OECD, 2018[2]).

Despite this progress, major gaps in coverage remain. Less than 30% of households with income below the poverty line receive a cash transfer. Major coverage gaps also exist in the absence of adequate responses to the needs of indigenous peoples, unemployed women and the great majority of workers in precarious conditions (Gabinete Social de la Presidencia de la República de Paraguay, 2018[6]). Moreover, Paraguay achieved coverage expansion largely by developing its targeted non-contributory programmes, but has not developed insurance mechanisms suited to most of the middle-income population, which is unprotected (Figure 3.2).

Social protection also lacks tools to cover certain risks. For instance, Paraguay has no unemployment insurance programme. Extending basic services and protection to vulnerable people involves many challenges and has been prioritised until now. Unemployment insurance schemes can sustain aggregate demand in times of crisis, support workers in managing risk and help them find better jobs. Traditional unemployment insurance schemes based on pooled payroll contributions can be very costly and generate adverse incentives in the presence of informality. Still, options such as individual unemployment savings accounts can help workers manage their unemployment risk and make their job search more effective without heavy government spending (Robalino, 2014[7]). The design of an unemployment benefits scheme should be based on an analysis of the cost to the public purse and the incentives that it would generate in the labour market.

The challenge of increasing and improving funding for social protection

Social spending in Paraguay has increased continually since the early 2000s. Spending on social protection, education and health makes up 63% of budgeted expenditures. Social protection spending increased from 2007 to 2016 for both social security (from 2.7% to 3.6% of GDP) and social assistance (from 0.7% to 1.2% of GDP). This puts Paraguay above the regional average but below countries with more developed social protection systems, such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Uruguay.

Even with increased spending, most essential programmes – whether designed to be universal or targeted – are not covering all of their target populations. Targeted programmes such as the Tekoporã conditional cash transfer and the Adulto Mayor social pension would need to at least double their budgets to reach their intended population (OECD, 2018[2]). Even nearly universal programmes such as school meals lack the resources to reach all children, which leads to rationing by local authorities, not always with transparent criteria (World Bank, 2018[3]).

The country’s comparatively low tax revenues partly explain the limited resources for social protection. Paraguay’s ratio of tax revenue to GDP is half the average for OECD countries, so it is hard for Paraguay to ensure public funding of all benefits of the welfare state. Low tax rates are one reason for this but the main cause is widespread evasion and informal employment, despite recent progress in these areas.

The country needs to redirect some social spending to key areas of social protection. The various programmes and implementing agencies are not integrated, which has led to high institutional fragmentation. This causes overlaps and increases management costs. In addition, spending sometimes goes to relatively expensive, unfocused programmes, failing to maximise the impact on the most vulnerable individuals.

Governance and management: the great challenge of integrating a highly fragmented system

Social protection in Paraguay is highly fragmented between non-contributory social assistance and contributory social security. Such fragmentation is fairly common in countries with work-related social security and a large informal economy. Separation of funding sources often leads to their separate management. All social protection operations then reproduce this segmentation, which is especially obvious in healthcare (Chapter 2) and the pension system (this chapter).

Social assistance operations are also highly fragmented internally. Not only are there numerous programmes (more than 35), but they are run by a multitude of institutions, including sector-specific ministries (Education, Health, Labour, Agriculture) and agencies focused on specific populations (children, youth, people living in poverty, women). The overlaps among specific populations lead in turn to overlapping programmes.

Past attempts at effective co-ordination among the organisations had a limited scope and limited success. The Social Cabinet brought together sector-specific ministries and specific secretariats but stopped meeting at ministerial level during the previous administration, losing its role in strategic co-ordination. The programmes’ strong centralisation also limited co-ordination on the ground. Two bodies were responsible for the co-ordination role: the executive group of the Social Cabinet, led by the Technical Secretary for Planning with support from a Technical Unit, and the Technical Secretariat for Planning itself, under the co-ordination of the anti-poverty programme Sembrando Oportunidades (Sowing Opportunities), which served as an operational co-ordinator but focused on fighting poverty. The Social Cabinet has since been reformed and has recovered a protagonist role.

Co-ordination tools exist but must be strengthened. The large number of programmes led to creation of separate information systems and different targeting mechanisms. Both have been converging in recent years. On the one hand, integrating the beneficiary databases into the SIIS (Sistema Integrado de Información Social) integrated database helps move the country towards a single registry of beneficiaries. On the other hand, Paraguay has developed a unified targeting instrument in the form of an information-form card to identify qualified beneficiaries (the “social information card” or ficha social) with the option of adding specific modules. This helps to unify the targeting criteria, though its rollout is still underway.

In healthcare and pensions in particular, there are gaps in regulation, governance and oversight. The system’s fragmentation makes the stewardship and oversight roles harder. In the health sector (see Chapter 2), it is necessary to strengthen the supervisory agency (the Health superintendence) by pragmatically unifying the oversight criteria for the private and public subsectors. The country also needs to bolster the steering function of the Ministry of Health, which would be easier if the service-provision function were separated from the stewardship and regulation function. Major gaps in the pension system include under-regulation of pension providers, especially for asset management, and the lack of a supervisory authority to ensure compliance with such laws.

Creation of a social protection system is underway

Since late 2018, Paraguay has carried out a set of institutional reforms to install a social protection system. To date, the biggest reform was probably the reorganisation of the Social Cabinet under decree 376 of 2018. It entrusts the Social Cabinet with designing and running the social protection system. Other reforms include turning the housing and social development authorities into full-fledged ministries, which lets them take part in inter-ministerial co-ordination, including the Council of Ministers.

The country has prioritised establishing a social protection system. For example, the decree reorganising the Social Cabinet also made the Ministry of Finance part of that cabinet, supporting the link between the SPS and the budget. It also places co-ordination in the hands of the Executive Secretary of the Presidential Management Unit, a minister responsible for running projects that are priorities of the Office of the President.

In the future, it will be necessary to institutionalise the social protection system in a more durable way. Paraguay has taken major steps towards inter-institutional co-ordination of operations by setting budgetary targets for 2019 and by beginning strategic planning for 2023. However, the SPS itself was established solely through an act of the the Social Cabinet, which makes the system vulnerable to future shifts in social policy.

Institutional consolidation also needs to continue. The law creating the Ministry of Social Development (Law 6139 of 2018) makes this ministry responsible for designing and implementing social development policies and for co-ordinating actions to reduce poverty and improve living conditions of vulnerable people. However, consolidation of the multitude of projects implemented by different institutions has not yet happened. This could be achieved on the ground as a knock-on effect of SPS co-ordination, but could have been accelerated through the ministry’s functions and powers. Paraguay must also ensure co-ordination between its contributory and non-contributory systems, keeping in mind that although the Social Security Institute (IPS) has an administrative role in the SPS, the IPS does not participate in its governance.

An action plan for pension reform in Paraguay

The Paraguayan pension system exemplifies the challenges facing the social protection system as a whole, in terms of coverage, funding, fragmentation and governance. Coverage of the working population is low and has progressed very little in recent years. Funding involves a dual challenge: ensuring stability in a contributory system that is generous despite being supported by relatively low contributions and low coverage, and the need for strong government funding to guarantee coverage of vulnerable older adults, in addition to the government funds needed to sustain some other segments of the contributory system. The system’s fragmentation, in turn, translates into unequal distribution of its generosity, causing large disparities in retirement parameters among workers with similar characteristics, and generating high administrative costs. Fragmentation also magnifies the challenge of governing the pension system, seen as both a systemic problem (the need for guidelines on pension fund investments and responsible management) and an individual problem in the management practices of each of the funds that make up the pension system.

Box 3.1. Workshop on “The pension system in Paraguay: Reform options”

The action plan for reform presented in this chapter was developed during a public policy workshop titled “The pension system in Paraguay: reform options”, held on 28 March 2019 in Asunción, Paraguay.

The workshop included opening speeches by Paraguayan government representatives that helped identify governmental priorities and contextualise the action plan. Public policy priorities highlighted by the administration’s leadership included formalising employment and developing an integrated system for social protection.

The workshop attracted about 40 participants, including civil servants (from the Ministry of Finance; Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security; Social Security Institute; the President’s Social Cabinet; and the Technical Secretariat for Economic and Social Development Planning), representatives from the labour and management communities, and managers of the various public pension funds that operate in the system.

The workshop followed the “government learning” methodology, adapted for multi-dimensional reviews. Key inputs included the main conclusions of the Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay on pensions, comparative experiences, and the specific experiences of Spain and South Africa. The workshop examined the proposed recommendations and necessary actions, debating them in four working groups, one for each of the four key areas identified in this chapter: (i) expanding coverage, (ii) equity and reforms, (iii) integration and consistency of the pension system, and (iv) governance.

The design of a holistic reform of the pension system will require a process of technical research, economic and legal evaluation by the agencies involved, as well as a broad communication agenda. The specific action plans presented in this chapter suggest specific actions in the short and medium-term and can be used as a key input for developing a systemic reform.

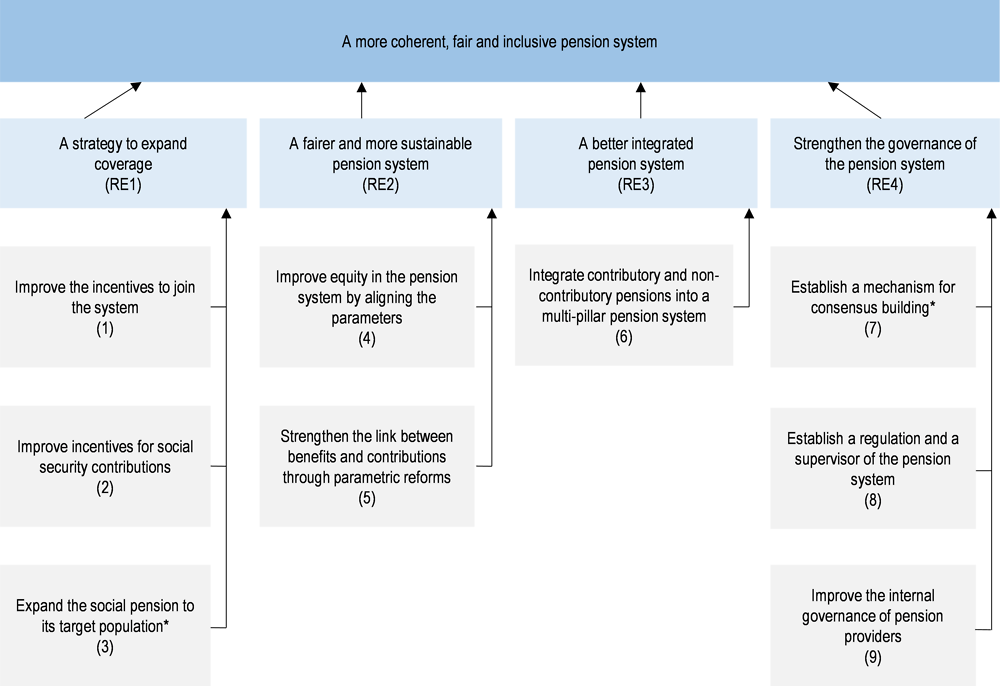

Given these challenges, this section presents an action plan structured into four parts, each of which seeks a specific expected result (ER) (Box 3.1):

Expand pension coverage, with emphasis on social security

A fairer, more sustainable contributory pension system

A more integrated pension system

A pension system with stronger governance

In each of these areas, the report offers detailed recommendations and a list of actions to bring them about. These action plans were developed by the OECD on the basis of a participatory workshop involving the stakeholders (public sector, social stakeholders, pension fund managers) (Box 3.1). They also include specific points were added from Volume II of the Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay (OECD, 2018[2]) consistent with the Paraguayan government’s planning documents and in support of the priorities identified therein. Notably, they reflect the priorities for the implementation of the Vamos! (Let’s Go!]) SPS and the Integrated Strategy for the Formalisation of Employment in Paraguay (MTESS, 2018[8]).

Figure 3.3. Priority goals and actions for pension reform

Note: (*) This recommendation was added after the public policy workshop on pensions.

A strategy to expand coverage of the pension system (ER1)

In 2017, 21.8% of the employed population made social security contributions (MTESS, 2017[9]). Among older adults, pensions covered only 46% of the population above age 65, and even that reflects an expansion of non-contributory pensions since the introduction of the Adulto Mayor programme, which by 2015 was covering 30% of the older adult population, doubling their coverage rate since the programme’s founding. This level of coverage puts Paraguay well below the average for Latin America.

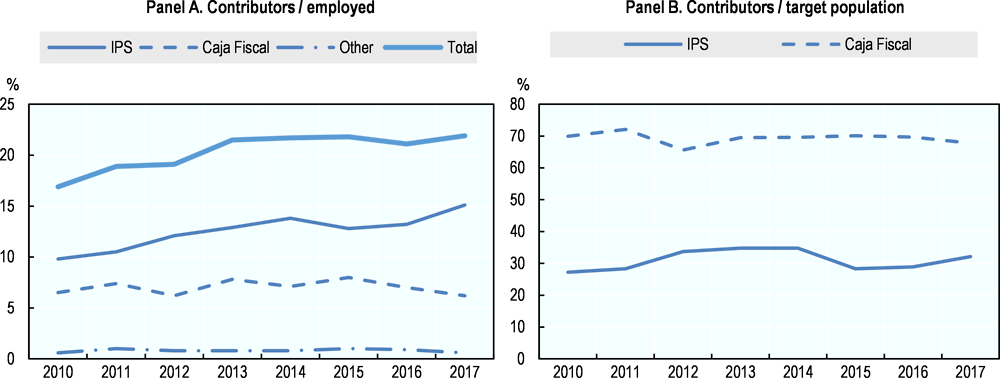

Coverage of the working population has progressed much less than coverage of older adults. From 2010 to 2017, the proportion making contributions to the pension system rose by 5 percentage points, from 16.9% to 21.9%. This increase, however, was concentrated in the early part of the period and has been stagnant since 2013 (Figure 3.4). In fact, this change is mainly due to an increase in formal employment in Paraguay which increased by 10 percentage points from 2005 to 2015 (excluding domestic work). Nonetheless, the coverage rate of pension funds has hardly changed in the public sector (Caja Fiscal) or the private sector (the IPS) relative to their specific target population (Panel B).

Figure 3.4. Coverage of the working population has changed thanks to the increase in formal employment

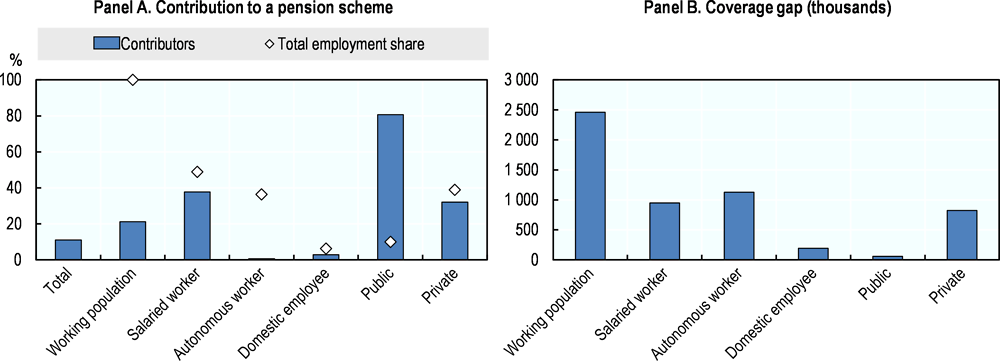

In practice, expanding contributory coverage involves a dual challenge: an effort to cover categories of workers who the system had effectively excluded, and increasing compliance for private-sector employees. Among the excluded categories, the largest group is the self-employed. Although they can contribute voluntarily to the IPS pension regime, only a small percentage do so. In practice, 1.1 million self-employed workers have no pension coverage (Figure 3.5). Excluded categories also include workers hired by the state as service providers (who are not in a permanent dependent employment relationship) who, because they are covered by specific provisions in the Civil Service Law (Law 1626 of 2000) and not by the Labour Code, are under service contracts with no social protection cover. As for private-sector employees, whose IPS contributions are mandatory, the coverage gap remains large, affecting about 950 000 workers in 2016. Action is therefore needed to encourage contributions and provide incentives for compliance.

The first two lines of action for developing a coverage expansion plan overlap with, but go further than, Paraguay’s employment formalisation strategy. The Integrated Strategy for the Formalisation of Employment in Paraguay (MTESS, 2018[8]) includes a series of information, inspection and deterrence measures to promote compliance with social security contributions. The strategy defines informal employees based on the definition of the International Labour Organization (ILO), which includes access to social security. However, for self-employed workers, formalisation is only determined by registering as a taxpayer (holding a RUC [Central Registry of Taxpayers] number), as the legislation does not provide for their compulsory affiliation to social security. As a logical consequence, the strategy sets formalisation of wage employment as its main goal. In practice, the Strategy for Formalisation does include steps to encourage self-employed workers to register, but those steps are not necessarily presented as a comprehensive plan to broaden coverage.

Figure 3.5. The dual challenge of the coverage gap

Improve incentives for registration (recommendation 1)

Increasing social security registration among self-employed workers is a vital step towards sustainably narrowing the social protection coverage gap. Currently, self-employed workers can register with social security (the IPS) voluntarily, though they can only access retirement benefits (Law 4933 of 2013). In practice, the regime is unattractive and covers very few workers.

To encourage voluntary registration with the pension system, a more appealing regime needs to be available. Adding other benefits could be decisive since workers place more value on short-term benefits (OECD, 2018[2]). This could include short-term financial benefits (maternity leave, sick leave, etc.) as well as health coverage.

Regulating and possibly expanding the social regime for micro-entrepreneurs should be a priority. Establishing the social regime for micro-entrepreneurs could increase their registration rates, but it should be opened to other categories. Law 5741 of 2016 (National Congress of Paraguay, 2016[10]) creates a special benefits regime for micro-entrepreneurs, who can access all IPS benefits as long as their business has annual sales revenue of less than PYG 500 million (Paraguayan guaraníes), in other words about 20 annualised minimum wages. Based on available information, the regime established by Law 5741 has not yet been implemented. Note, too, that this law creates a set of obstacles to its own use, such as the need to register in advance as a micro-enterprise with the Ministry of Industry. It also offers a rather less advantageous regime than the general regime (for instance, it calculates the pension regulatory base over 10 years, compared to 3 in the general regime1) despite having the same contribution rate. Lastly, the regulations will need to clarify calculation of self-employed workers’ contributions, since the law bases it on employees’ reported salaries. Moreover, regulations would have to clarify the calculation of contributions for self-employed workers, which are set on the basis of declared wages by law.

Making contributions more flexible could be key to encouraging enrolment in pension schemes by self-employed workers, whose income is not only lower but more sporadic. Adding this type of leeway is characteristic of regimes designed to incorporate self-employed workers, especially those in sectors with irregular or seasonal income (Hu and Stewart, 2009[11]). There could also be monetary incentives for contributions, but they have to be designed with caution to avoid producing differentials that could discourage wage employment in favour of self-employment. It is also important to anticipate the government spending involved. In Costa Rica, the state contributes 0.8% of an employee’s salary to the employee’s social contribution and a much larger amount of the social contribution of self-employed workers, exceeding 11% for low-income self-employed workers. This contribution largely explains why Costa Rica has the region’s lowest rates of informal self-employment (OECD, 2017[12]). An alternative is to offer temporary discounts on self-employed workers’ contributions. For example, in Spain, the Special Regime for Self-Employed Workers (RETA) offers newly registered self-employed workers a discounted contribution level (commonly called the “flat rate”2). This discount decreases over time and disappears after two years (three years for workers under age 30).

Successful examples of incorporating self-employed workers into the social security system include adoption of simplified monotax (monotributo) regimes for small taxpayers in the region. In Argentina, the monotax regime covers both tax obligations and pension contributions for the workers who sign up for it. In 2013, five years after it was put in place, the simplified regime covered 2.7 million contributors, in other words, nearly a quarter of all workers. In general, the monotax regimes in the region have shown a marked ability to bring workers into the fiscal and pension system (Cetrángolo et al., 2014[13]). Regarding pensions, though, note that monotax regimes generate fairly modest tax revenues while granting entitlements. In practice, this means generating a liability for the pension system that must be offset by government funding.

The Integrated Strategy for the Formalisation of Employment suggests a design for a monotax proposal, which this chapter’s action plan reiterates. This proposal should explicitly identify the regime to which the monotax would provide access and explicitly quantify the necessary infusion of government funds, based on existing actuarial studies.

Another key aspect of expanding coverage is to incorporate categories excluded from the pension system. One priority is to include in a mandatory social security scheme contract workers of the public sector, through their inclusion to the civil servants regime (Caja Fiscal), or to IPS in the case of public institutions that contribute to the general regime. They add up to about 36 000 workers, that is almost 17% of total salaried workers of the public sector, and they remain currently outside the scope of social security.

When adding new categories of workers to the social security system, certain public policy principles must be respected. Bringing in workers with nonstandard occupations or employment relationships (i.e. other than open-ended formal employment) often involves creating special regimes. A recent OECD analysis of these workers’ special regimes and coverage (OECD, 2018[14]) highlights four lessons: (i) contribution rates should be as homogeneous as possible between one form of employment and another, (ii) voluntary registration systems do not work well for atypical working relationships, (iii) benefit portability should be guaranteed when changing jobs or changing job status, and (iv) it is necessary to ensure the security of workers with flexible work schedules (by guaranteeing a minimum number of hours or through guaranteed minimum income and bonus pay).

The minimum contribution level is one obstacle to expanding social security coverage, both for categories currently covered and for potential new regimes. The minimum wage in Paraguay is fairly high relative to the population’s work-related income. It is more than 80% of average pay, while in the average OECD country it is less than 40% of average pay (OECD, 2018[1]). Aside from perhaps revising the method for determining the minimum wage, one option would be to consider using another parameter as the minimum contribution base, whose level and evolution could be unlinked from the minimum wage to encourage lower-income workers to participate. For instance, in Panama, the minimum Social Security Fund pension is used as the minimum contribution base. Since it is below the minimum wage, using this base does not impose a high proportional cost on low-income workers. In almost all countries in the region, including Paraguay, the theoretical cost of formalising lower-income workers is higher than for more affluent workers (OECD/IDB/CIAT, 2016[15]). The Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MTESS) and the IPS should analyse the feasibility of this proposal for coverage of financial benefits (under, for example, the regimes in Law 4933) that can be indexed to the new parameter.

Improve incentives for social security contributions (recommendation 2)

Effective expansion of coverage also requires clear incentives for making these contributions. This requires action in four specific areas: (i) more effective and better co-ordinated enforcement, (ii) making it easier to register and to pay contributions, (iii) a strategy to raise employers’, employees’ and the public’s awareness of the importance of paying contributions regularly, and (iv) an analysis of contribution histories making it possible to develop strategies to bring workers back into the system.

Strengthening enforcement will require providing it with sufficient resources and stronger processes. With fewer than two inspectors per 100 000 workers, Paraguay is below the average for the region (just under four) and for OECD countries (seven) (Alaimo et al., 2015[16]). A key tool for enhancing enforcement is the use of interconnected data from the various government agencies. Using a unique personal identifier (such as the national ID number) in both the IPS database and the MTESS register of workers and employers could be a first step towards linking the two databases. Argentina and Brazil have made progress in this regard, though there is still further work to be done. Linking the information to data from the tax administration agency is also necessary, since companies have incentives to declare employee pay, as this reduces their tax base.

Processes have been simplified further by eliminating the registration fee and opening an online registration system. This change will need careful monitoring, since the two-month moratorium on fines adopted in late 2018 (Decree 553/18) may have had a favourable effect on the registration of companies. It is also necessary to continue efforts to simplify and, if possible, unify procedures. This is especially important for social security (IPS) registrations, but there are also multiple registers in other areas which are not sufficiently interconnected (for example, in the Ministry of Industry and Commerce for access to MSME benefits, in the Ministry of Childhood and Youth for registration of workers under 18 years old, etc.).

Third, it is necessary to implement a communication strategy about rights and responsibilities. This strategy is partly related to the work of labour inspections: the inspection itself should include supplying information and accompanying the fulfilment of compliance in a way suited to the businesses’ circumstances, which requires updating the inspection manuals. For example, the manual could set a deadline for correcting certain specific compliance issues among the more vulnerable categories of businesses, such as micro and small enterprises. On the other hand, a broader information strategy, modelled on that of the Financial Inclusion National Strategy (ENIF) could bring information to businesses, workers as well as schools about rights and responsibilities related to work and social security. Note that most formal employees who fail to pay into social security do so at their employer’s request or as a condition of employment, so it is necessary to strengthen workers’ ability to defend their rights.

Expand social pension coverage to its target population (recommendation 3)

The social assistance programme for vulnerable older adults is an entitlement of Paraguayans living in poverty, established by Law 3728 of 2009. This benefit, commonly known as the Adulto Mayor pension, has gone a long way towards reducing the level and severity of poverty and towards reducing inequality (OECD (2018[1]), (2018[2])). However, nearly ten years after the law was enacted, the programme’s coverage remains limited: in 2016 less than a third (28%) of older adults in the households from the two poorest deciles were receiving programme benefits (OECD, 2018[2]).

To ensure coverage of its target population, the Adulto Mayor programme would need a significantly larger budget. The programme’s 2019 budget totals 0.5% of projected GDP. Ensuring universal coverage would require increasing this budget to 1% to 1.5% of GDP, depending whether one assumes perfect targeting or the current levels of inclusion errors. The Ministry of Finance, who administers the programme, is working on both fronts: on the one hand, it is improving the programme’s targeting performance, and on the other hand, it has supported the programme’s growth, carrying it from 94 000 beneficiaries in 2013 to 193 000 in 2019.

Integrating the social protection system could bolster effective targeting of the social pension. Note, however, that because the benefit level is tied to the minimum wage, it is relatively high compared to the income of the population as a whole.

Making parametric adjustments for a fairer, more sustainable pension system (ER2)

The challenge of funding the pension system has two distinct but interrelated aspects. First, the contributory system’s main regimes are generous compared to those of other countries. Actual contribution levels to the main regimes are lower than those of most OECD countries, while the 100% replacement rates for full retirement in the main regimes are higher than those of OECD countries and the region as a whole (OECD, 2018[2]). These parameters result in actuarial deficits for most of the pension funds. Also, some regimes have current deficits. Such is the case of the Caja Fiscal’s teachers’ regime, whose deficit is covered by current surpluses from other civil regimes in the Caja Fiscal. It is also the case of non-civilian regimes, whose deficit is covered by contributions from the public purse.

Moreover, the pension system’s generosity is unevenly distributed. Given the multiplicity of regimes and pension funds, there are major parametric differences among workers. These differences in replacement rates, accrual rates and terms of retirement tend to generate social unrest, since they are not necessarily justified by each group’s working conditions. While the Interfund law (Ley Intercajas) establishes a mechanism to promote worker mobility, parametric differences may penalise a worker who transfers from a pension fund with lower seniority requirements to one with higher requirements.

The demographic situation in Paraguay is favourable to the pension system, but parametric reforms will be easier if they are pursued now. The country’s population is young, with 48% under age 25 according to national estimates. United Nations population projections predict that the dependency ratio will continue to decrease until the year 2045. Bear in mind, though, that if parametric reforms were to apply only to people just entering the system, they would take 30 years to phase in and would therefore take full effect in precisely that decade.

Strengthen the link between benefits and contributions through parametric reforms (recommendation 4)

The design of a parametric reform should be based on comprehensive actuarial studies built on shared assumptions. These, in turn, especially require homogeneous demographic projections, particularly mortality tables, for the insured population.

Taken together, a pension system’s parameters should guarantee the system’s sustainability, and in the case of Paraguay, the sustainability of each of the pension funds and regimes. Therefore, the necessary adjustments to the retirement age, the regulatory base and benefit levels require specific actuarial studies and an inclusive, well-informed debate involving the stakeholders. The discussion of this matter during the policy workshop held in phase III of the Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay, did not therefore propose specific values for most of these parameters.

One priority is to establish a regular review of the regimes’ actuarial health and the current demographics. This would be a basis for proposing the necessary adjustments to the retirement age and other parameters. For instance, in South Africa, actuarial analyses are performed at most every three years and any regimes or funds that show a deficit must submit a corrective plan (within three months). In practice, when the government employees’ pension regime cannot cover all of its liabilities plus the future liabilities that would be accumulated over the next two years, the actuarial report proposes increased employer contributions to cover at least 90% of future liabilities (Republic of South Africa, 1996[17]) and can recommend other measures. In other countries, the reports leave it to the state to choose how to remedy the deficit, whether through parametric changes or through government funding.

Regarding the retirement age, note that the 2003 parametric reform of the Caja Fiscal (Law 2345, the Caja Fiscal Reform and Sustainability Act) set the retirement age at 62 for employees in the public administration and magistrates, and that life expectancy at birth has increased by 2.4 years since then. At the same time, other regimes, including public regimes, still set the retirement age at 60 or lower.

The parametric reform should include extending the reference period used in establishing the calculation basis. The period considered in the calculation basis has been extended for several special regimes. It is 120 months for the private-sector teachers’ regime governed by Law 4370/11 and is 5 years for most of the Caja Fiscal regimes (Law 2345/03). The 36-month period for the IPS general regime generates a set of incentives to underreport earnings and can penalise those workers for whom job placement is more difficult towards the end of their working lives (Molinas et al., 2015[18]). Given the periods established in special regimes, an extension to 120 months seems feasible in the short term and would be technically possible as the necessary information is digitised within the IPS.

Implementation of parametric reforms should be gradual and should not affect workers who cannot adjust their work patterns or their contribution patterns to ensure a suitable retirement. Participants in the pension policy workshop underlined that reforms should not apply to workers close to retirement. In practice, enacting reforms only for new entrants would involve a very long phase-in period for the reforms (about 30 years). However, for reforms such as extending the calculation basis period to 10 years, a phase-in of the same duration would make it possible to adapt workers’ pension-related behaviours and would have a much greater impact on the system’s actuarial health.

Improve equity in the pension system by aligning parameters (recommendation 5)

There are big differences among the parameters of different pension regimes, resulting in differences in their generosity. These have operational implications, such as the ability to limit incentives for labour mobility.

The differentials are also problematic from an equity standpoint, especially for state-guaranteed regimes. From the point of view of their funding, public regimes are explicitly or implicitly guaranteed by the state. This is obvious in the case of the Caja Fiscal, for which government funds cover the current deficit of regimes that carry deficits (as is the case of the Non-Civil contributory regime).3 For IPS regimes, the state has never made good on its contribution as defined in the charter, and this gives rise to an implicit guarantee as this contribution could be demanded in case of a deficit.

Progressing towards unifying the different regimes’ pension parameters would make it possible to reduce the fragmentation’s potential negative impact on the labour market. In fact, though the years of contributions can count towards accrual of entitlements, changing to another pension fund can lead to less favourable results for some workers.

On the other hand, the convergence of parameters is a prerequisite for a smoother transition to an integrated system (see ER3). With differing parameters, a transition to an integrated system involves, in practice, a long phase-in during which only people newly entering the system are channelled into the integrated system – generally state employees who are joining the general regime. The alternative would involve large transfers of government funds from the state to the pension system (Palacios and Whitehouse, 2006[19]).

Harmonising the parameters of public and private pension funds could occur through regulatory reform, but also through the funds’ own response to a solvency requirement. Taking the South African model, pension funds could be required to either show a positive actuarial balance or proceed with the necessary parametric adjustments.

In seeking to standardise pension funds’ parameters, the country should allow for differences justified by the needs of groups that have objectively different circumstances. About half of the countries in Latin America allow for differences in retirement ages for men and women. In practice, most OECD countries have eliminated different retirement ages for men and women (OECD, 2017[20]). Given their more fragmented careers, an earlier pension for women worsens the retirement asset gap between men and women. Conversely, most OECD countries compensate women for time devoted to caregiving tasks by subsidising contributions made during maternity leave, which, together with redistributive aspects of the contributory system, helps narrow the retirement gender gap caused by caregiving tasks (OECD, 2015[21]).

The proliferation of special retirement arrangements is not generally justified by technical criteria. For example, in many cases, there is a historical justification but no technical justification for arrangements that let certain categories of workers retire early or with shorter contribution histories. First, such arrangements help distort the labour market, since riskier or harder jobs should compensate the worker with wage premiums. Second, early pensions may not be the best way to support workers who can still work (in which case retraining support would be more beneficial) or who can no longer work (in which case more generous disability benefits should be considered). Third, if additional pension benefits are deemed necessary, it is important to verify that the amount is fair in light of the person’s career and the nature of the job (Zaidi and Whitehouse, 2009[22]).

Working towards integration of the pension system (ER3)

The fragmentation of the pension system generates inequality and inefficiency in the system and in the labour market. On the one hand, workers in different systems obtain more or less generous benefits despite depending explicitly or implicitly on public resources. The most conspicuous inequality is among workers who retire with replacement rates much higher than international averages and workers who, having contributed for fewer than the 15 years needed to obtain entitlements, are excluded not only from retirement benefits but also from health coverage, even if they have paid in for ten years4 (OECD, 2018[2]). On the other hand, fragmentation leads to the creation of relatively small pension funds, which may involve high administrative costs.

Integrating the pension system is consistent with the logic of creating a social protection system. The systemic vision underlying the Vamos! SPS involves dealing with the pension system as a whole (Gabinete Social de la Presidencia de la República del Paraguay, 2019[23]). Note, however, that non-contributory benefits are part of pillar 1 (Social inclusion) of the SPS, while contributory benefits are part of pillar 3 (Social welfare). That said, although the IPS does not seat in the Social Cabinet, it is one of the institutions contributing to pillar 3 and is part of the inter-institutional technical team defined for monitoring pillar 3 – along with the MTESS, the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MSPBS) and the Ministry of Finance (MH).

Integrate the contributory and non-contributory pensions into one multi-pillar pension system (recommendation 6)

Under the OECD typology (OECD, 2005[24]), the three pillars of Paraguay’s pension system are fragmented both internally and among themselves. This raises concerns about equity. This can also inadvertently create coverage gaps among citizens who do not fit into any of the programmes. Additionally, it generates perverse incentives: for instance, the lack of developed programmes for a supplementary voluntary savings pillar could encourage higher-earning workers to limit their pension savings if higher contributions would not increase their retirement assets.

The redistributive pillar, designed to alleviate poverty among older adults, has two distinct components in practice. On the one hand, the Adulto Mayor programme, which offers a benefit equal to one-fourth of the minimum wage for older adults living in poverty (as measured by a multi-dimensional test), is funded by the government. On the other, the contributory minimum pension for IPS beneficiaries, equal to a third of the minimum wage, is funded with resources from the contributory system.

The mandatory contributory pillar is fragmented between civil servants (Caja Fiscal) and private-sector workers (the IPS), with a multitude of special regimes within each subsystem. It also includes most of the independent pension funds, though the ANDE (Administración Nacional de Electricidad [National Electricity Administration]) and Itaipú funds’ regimes may be said to combine elements of the second pillar (contributory) and a third pillar (supplementary).

Building an integrated system might involve creating a single pension administration or at least the absorption of several fund management entities. This proposal, supported by the participants in the public policy workshop on pensions, could be phased in by closing the public programmes to new entrants but maintaining their separate management until those retirees or funds no longer exist. In practice, this separation would mean transferring part of the liability to the new regime (or to the general regime), the size of which would need to be quantified.

Besides possibly merging the management of the various pension regimes, progress could be made towards a more integrated system by analysing the complementarity of the different elements that make up the pension system, both within each pillar and across pillars. A key element of this integration is determining the contingent liabilities incorporated into each of the regimes, especially the public regimes.

The second key element is to integrate the contributory and non-contributory systems. This could include joint administration of the two elements, though the distinctive capacity needed in the non-contributory pillar to support vulnerable older adults should be preserved, as they involve a comprehensive approach to their circumstances in harmony with other first-pillar SPS programmes. Under the current system, however, workers who never qualify for retirement are completely excluded from the contributory system for both pensions and healthcare. Therefore, for workers unsure whether they will have a long enough contribution history, there is no incentive to contribute. Adjusting the contributory and non-contributory pension parameters could enable these workers to obtain a reduced pension supplemented by a non-contributory component. Because it would be part of the IPS, the final pension would have to comply with the legally defined minimum pension, though with less government funding than the current approach.

The second aspect of integrating the contributory and non-contributory pillars is the mechanism for funding the IPS contributory minimum. At present, this benefit has no explicit funding source, and it therefore involves a mechanism for redistributing funds among IPS contributors. However, these contributors include workers who will not qualify to receive a pension. There should be a detailed study of those receiving a minimum pension benefit and of its distributive impact. The lowest retirement pension, corresponding to the minimum proportional pension, amounts to 60% of the average of the last 36 months of declared wages. The minimum pension applies when this is below 33% of the minimum wage. Therefore, in practice, the minimum pension serves to correct very low benefits due to eroded regulatory bases more than as a redistribution mechanism between those with large and small pension entitlements In general, a benefit such as the minimum pension could be considered a non-contributory benefit. For instance, Spain has a similar mechanism (the complemento a mínimos, a supplement to the minimum pension) to complement retirement assets deemed too low, funded by the treasury (Hernández de Cos, Jimeno and Ramos, 2017[25]).

Lastly, Paraguay could develop the voluntary retirement savings system as a mechanism to promote savings among higher-income categories. Because these categories are near the ceilings for the pay-as-you-go system, they have limited incentives to contribute to the system. Moreover, there is no ceiling on contributions, which lowers the incentives for voluntary retirement savings for those with high incomes. A retirement savings system can make it possible to channel resources in the financial system towards productive investments by encouraging the use of long-term instruments. The existing occupation-specific programmes could be part of this system, through either voluntary or compulsory sign-up within the framework of the employer.

Strengthening governance of the pension system (ER4)

The fragmentation of Paraguay’s pension system is reflected in regulations that are, in turn, fragmented and flawed. The different regimes and pension funds are governed by separate laws, many of them out of date, rooted in thinking that is at odds with technical considerations and opinions. Additionally, the pension system lacks necessary regulations regarding the principles of pension fund management and oversight. In the past, this shortcoming has resulted in large losses of assets, and in other cases, in insufficient returns.

In part, this fragmentation comes from a lack of a basic political consensus on the principles the pension system should respect. The handling of the pension superintendence bill in 2018 exemplifies how easily political stances polarised the debate, making it impossible to adopt despite support from both the outgoing and incoming administrations during the political transition.

Establish a mechanism for seeking consensus among pension system stakeholders (recommendation 7)

Therefore, seeking areas of political consensus should be prioritised when working to improve governance of the pension system. Note that this approach was not one of the proposals in Volume II of this study, but it was a recurring request from the stakeholders who participated in the pension policy workshop, in the discussion about necessary oversight and the discussion of parametric reforms.

Paraguay should determine the most appropriate way to establish these spaces for dialogue, which should in any case include buy-in by the Legislative Branch, given the way recent reforms have played out. In Spain, the Toledo Pact, signed between the political parties in 1995, made it possible to shield the social protection system from partisan wrangling and channel it into calm political debate, with the necessary technical support within Congress. This pact made it possible to reach broad consensus on the need for ongoing adjustments to the system amid changing circumstances. It also made it possible to generate the consensus needed for large-scale reforms such as the funding principles, setting up a reserve fund and integrating different regimes (Ministerio de Trabajo e Inmigración de España, n.d.[26]).

Establish regulations and a regulatory body for the pension system (recommendation 8)

Paraguay should draft regulations on the use of pension funds. This would help ensure that pension savings are managed using the necessary standards of prudence and performance. At the same time, it would make it possible to channel resources into productive areas of the economy. The need for such regulations has been widely accepted by the executive branch and is supported by multiple multilateral institutions. Beyond the accepted need to regulate, these regulations should adopt risk-based oversight in accordance with the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (2016). Specific investment guidelines (such as ceilings per asset category) could be defined after a debate that looks at international experiences and regulations, as well as current practices in Paraguay.

Within investment regulations, it would be important to assess the IPS’s regulations and investment strategy. Underdeveloped capital markets and the restrictions on international investment have produced a risk of leaving too large a percentage of assets in demand deposits or short-term deposits, putting assets at risk in case of a banking crisis and risking very low yields.

Besides establishing regulations, Paraguay should establish a supervisory body for pension providers. There is broad consensus on the need for a supervisory body, the need for it to be impartial and administratively and financially independent, and the need for transparency guidelines. However, some elements are still open to debate in defining the governance of the supervisory body and the best way to organise audits, sanctions and any necessary receivership.

Improve the internal governance of pension providers (recommendation 9)

Pension management firms’ administrative capacity and governance should continue to be strengthened. This means continuing the process of digitising records, which is vital to effective implementation of the Interfund law and for effective risk management. It also means generating actuarial reports at regularly scheduled intervals. This would require strengthening the training of qualified staff in the country.

Regarding the IPS, despite the separation of pension and healthcare funds, their joint management generates some risks that should be eliminated. In order to separate the funding sources for the IPS’s different functions more strictly, these sources must be identified for each type of benefit. This means not just distinguishing between short- and long-term benefits but also establishing explicit funding mechanisms for certain benefits, such as cover for occupational risks.

Action plan summary table

Table 3.1. A strategy to expand coverage

|

Policy recommendations |

Stakeholders |

Actions for implementation |

|---|---|---|

|

Improve incentives for formalisation (1) |

||

|

Offer a more appealing system for self-employed workers. |

MTESS IPS |

- Propose changes in the social regime for self-employed workers:

- Develop a monotax proposal - Discuss mandatory coverage |

|

Bring excluded categories into social security |

IPS/Caja Fiscal MTESS Congress MH |

Public-sector employees |

|

Consider the minimum pension as minimum income when calculating contributions |

MH MTESS All Pension Funds |

Launch a discussion to define a minimum contribution base parameter other than the minimum wage. |

|

Improve incentives for social security contributions (2) |

||

|

Strengthen the inspection and oversight system to fight evasion |

IPS MTESS MH MITIC MIC |

Strengthen and interconnect information systems:

Strengthen inspection teams and processes:

|

|

Help employers register their employees. |

MTESS IPS |

Online registration of companies. Merge Obrero Patronal registration between the IPS and the MTESS. |

|

Link inspection and oversight with informational and advisory campaigns |

MTESS IPS |

Strengthen communication and the availability of information about the changes, progress of processes, submission methods, etc. |

|

Approve a strategy for informing the public about the benefits of making regular social security contributions |

MTESS IPS MITIC MEC |

Design a strategy that includes:

|

|

Follow up with participants who stop making contributions. Whenever possible, emphasise reintegrating them into the system. Analyse and learn about why people stop making contributions. |

MTESS IPS MH All Pension Funds |

Work on the quality of administrative records. More specific analyses of registrations and deregistrations, job transitions |

|

Expand social pension coverage among its target population (3) |

||

|

Expand coverage of the Adulto Mayor programme among its target population |

MH |

Bring older adults living in poverty into the Adulto Mayor programme. Ensure medium-term funding of the programme. Revise the targeting criteria |

Table 3.2. Action plan for a fairer and more sustainable pension system

|

Policy recommendation |

Stakeholders |

Actions for implementation |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Strengthen the link between benefits and contributions (4) |

|||

|

Establish a mechanism to review the retirement age |

All pension funds MTESS MH |

Review periodically (every 3 years) based on actuarial studies. To that end, the available information should be verified (mortality tables). Perform a solid statistical study, obtain actual bases, and if none are available, obtain data from other countries. |

|

|

Set a uniform ceiling for any pension benefit |

All pension funds MTESS MH |

Draft a proposal based on the retirement age mechanism |

|

|

Raise number of years used to calculate the pension benefit |

All pension funds MTESS MH |

The increase must be gradual, progressive and predictable. The proposal is to eventually use the ten best years of contributions. |

|

|

Review the benefit level |

All pension funds MTESS MH Social sectors |

The goal is to phase in unification based on a cohort newly entering the system. |

|

|

Adjust contribution rates |

All pension funds MTESS MH |

Actuarial analysis should do a study for a new model of new contributors. This should be reviewed periodically every 5 years or as required by economic events. |

|

|

Establish a ceiling for contributions |

All pension funds MTESS |

Elaborate a proposal to limit the maximum contribution so as to incentivise private savings |

|

|

Improve equity in the pension system (5) |

|||

|

Standardise the retirement age and the benefit calculation base. |

All pension funds MTESS |

Harmonise the retirement age among all pension funds. They will need support to determine the parameters. Clarify the role of the supplementary fund. |

|

|

Standardise replacement and accrual rates |

All pension funds MTESS |

Differentiation among the funds: The Caja Fiscal is very different and it would be useful to standardise. Analyse the adjustment of replacement rates on the basis of actuarial studies of each fund. |

|

|

Ensure all pension benefits are indexed |

MTESS |

||

Table 3.3. A more integrated pension system

|

Policy recommendation |

Stakeholders |

Actions for implementation |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Integrate the contributory and non-contributory pensions into one multi-pillar pension system |

|||

|

Create an integrated pension system with a defined programme of benefits and obligations with equality from one sector to another |

MTESS IPS MH Administration of the pension funds |

|

|

|

Integrating contributory and non-contributory programmes into a single system |

MTESS IPS MH |

|

|

|

Develop a voluntary retirement savings system |

MH IPS MTESS |

Analyse the potential impact of a cap on IPS contributions that would let workers put the excess into other pension funds |

|

Table 3.4. Strengthening governance of the pension system

|

Policy recommendation |

Stakeholders |

Actions for implementation |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Establish a mechanism for seeking consensus among pension system stakeholders (7) |

|||

|

Generate a broad agreement among political parties, business owners and workers |

Political parties MTESS MH Trade unions Social Cabinet |

|

|

|

Oversee and regulate pension providers (8) |

|||

|

Establish a supervisory body for pension providers |

Legislative branch MTESS MH Central Bank of Paraguay (BCP) |

|

|

|

Furnish the supervisory body with sufficient financial and human resources |

MH |

|

|

|

Ensure impartiality of the supervisory body and the auditors by separating their pay from the audited institution. |

Legislative branch MTESS MH BCP |

|

|

|

Set guidelines for managing pension funds’ assets and liabilities: - Investment guidelines with actuarial criteria - Ceilings for levels of investment by category - Prudence concept - Diversification principle |

Pension funds IPS MH MTESS BCP |

|

|

|

Improve the internal governance of pension providers (9) |

|||

|

Digitise the registry of contributions, contributors and beneficiaries in all pension funds |

Management firms |

|

|

|

Standardise financial reports submitted to the Ministry of Finance and other institutions |

Management Firms MTESS |

|

|

|

Clearly separate the management of the IPS’s pension and health functions |

IPS MSPBS |

|

|

|

Transform the Caja Fiscal into an independent institution |

MH |

|

|

References

[16] Alaimo, V. et al. (2015), Empleos para crecer, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington D.C., http://dx.doi.org/10.18235/0000139.

[13] Cetrángolo, O. et al. (2014), Monotributo en América Latina: Los casos de Argentina, Brasil y Uruguay, OIT, Oficina Regional para América Latina y el Caribe, Programa de Promoción de la Formalización en América Latina y el Caribe, Lima, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---americas/---ro-lima/documents/publication/wcms_357452.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2019).

[4] DGEEC (2017), Encuesta Permanente de Hogares [Permanent Household Survey] (database), Dirección General de Estadística, Encuestas y Censos, Fernando de la Mora, http://www.dgeec.gov.py/datos/encuestas/eph.

[6] Gabinete Social de la Presidencia de la República de Paraguay (2018), Nota Sectorial de proteccion social 2.0: Protección social en Paraguay. La oportunidad de implementar un sistema de protección social, Asunción.

[23] Gabinete Social de la Presidencia de la República del Paraguay (2019), Presentación estructurada de la propuesta general del sistema de protección social del Paraguay, Asunción.

[25] Hernández de Cos, P., J. Jimeno and R. Ramos (2017), “El sistema público de pensiones en España: situación actual, retos y alternativas de reforma”, Documentos Ocasionales, No. 1701, https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/SES/Secciones/Publicaciones/PublicacionesSeriadas/DocumentosOcasionales/17/Fich/do1701.pdf.

[11] Hu, Y. and F. Stewart (2009), “Pension Coverage and Informal Sector Workers: International Experiences”, OECD Working Papers on Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 31, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/227432837078.

[5] ILO (2017), Paraguay: Protección social en salud: reflexiones para una cobertura amplia y equitativa, International Labour Organization, Santiago.

[26] Ministerio de Trabajo e Inmigración de España (n.d.), “Informe de evaluación y reforma del Pacto de Toledo [Evaluation and reform report of the Toledo Pact]”, Colección Seguridad Social, No. 35, Ministerio de Trabajo e Inmigración de España, Madrid, http://www.seg-social.es/wps/wcm/connect/wss/837109f0-e8fa-47fb-b878-668afc1bca1e/Informe+Pacto+de+Toledo+2011..pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=.

[18] Molinas, V. et al. (2015), Estudio actuarial del fondo de jubilaciones y pensiones del Instituto de Previsión Social, Asuncion.

[8] MTESS (2018), Resolución MTESS No 98/18 por la cual se aprueba la estrategia integrada para la formalización del empleo en Paraguay, Ministerio de Trabajo, Empleo y Seguridad Social de Paraguay, Asunción.

[9] MTESS (2017), Boletín Estadístico de Seguridad Social 2017 [Social Security Statistical Bulletin 2017], Ministerio de Trabajo, Empleo y Seguridad Social de Paraguay, Asuncion, http://www.mtess.gov.py/application/files/1615/4351/0534/DGSS_Boletin_2017.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2019).

[10] National Congress of Paraguay (2016), Ley No. 5741 que establece un sistema especial de beneficios del sistema de seguridad social (IPS) a los microempleadores, Asunción.

[1] OECD (2018), Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay: Volume 1. Initial Assessment, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264301900-en.

[2] OECD (2018), Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay: Volume 2. In-depth Analysis and Recommendations, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264306202-en.

[14] OECD (2018), The Future of Social Protection: What Works for Non-standard Workers?, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264306943-en.

[12] OECD (2017), OECD Reviews of Labour Market and Social Policies: Costa Rica, OECD Reviews of Labour Market and Social Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264282773-en.

[20] OECD (2017), Pensions at a Glance 2017: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2017-en.

[21] OECD (2015), “How incomplete careers affect pension entitlements”, in Pensions at a Glance 2015 OECD and G20 indicators, OECD publishin, Paris, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/pension_glance-2015-6-en.pdf?expires=1559060719&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=ABD19050275A4985CB7C50B644425BEE (accessed on 28 May 2019).

[24] OECD (2005), OECD Pensions at a Glance 2005: Public Policies across OECD Countries, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2005-en.

[15] OECD/IDB/CIAT (2016), Taxing Wages in Latin America and the Caribbean 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264262607-en.

[19] Palacios, R. and E. Whitehouse (2006), “Civil-service Pension Schemes Around the World”, SP Discussion Paper, No. 0602, The World Bank, Washington D.C., http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/546181468147557849/pdf/903400NWP0P1320Box0385283B00PUBLIC0.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2019).

[17] Republic of South Africa (1996), Government Employees Pension Law (GEPF), Government Employees Pension Fund of South Africa, Cape Town, http://www.gepf.gov.za/uploads/annualReportsUploads/Government_Employees_Pension_Rule_and_Law.pdf.

[7] Robalino, D. (2014), “Designing unemployment benefits in developing countries”, IZA World of Labor 15, http://dx.doi.org/10.15185/izawol.15.

[3] WB (2018), Paraguay: Invertir en capital humano: Una revisión del gasto público y de la gestión en los sectores sociales, The World Bank, Washington D.C., http://www.worldbank.org (accessed on 31 May 2019).

[22] Zaidi, A. and E. Whitehouse (2009), “Should Pension Systems Recognise “Hazardous and Arduous Work”?”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 91, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/221835736557.

Notes

← 1. This is not to say that the regulatory base should be set at 3 years. Indeed, this report recommends that it be extended at least to 10 years for other regimes, including the general regime of IPS.

← 2. RETA contributors choose their contribution base within a range defined by regulations, depending on their working circumstances rather than their actual income. For many of them, the discounts and contributions are therefore calculated according to the minimum contribution base.

← 3. In the case of the deficit of the regime for public sector teachers, the deficit is covered by surpluses in other civil regimes in the same fund.