Paraguay has experienced strong growth since the 2000s, supported by a solid macroeconomic policy framework. The country has set itself ambitious goals to adopt a development path that is more inclusive, efficient and transparent. To achieve those goals, it will have to tackle major challenges and implement a broad and vigorous reform agenda. The Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay was carried out to support the country in achieving its development objectives. This chapter explains the process of implementing the Multi-dimensional Review in Paraguay and summarises the main obstacles related to the Sustainable Development Goals (people, prosperity, planet, peace and institutions, and partnerships). It then presents the country’s main cross-cutting challenges – namely, moving along a more inclusive development path and laying the foundations for sustainable growth – as well as the main results of the detailed analysis in Volume 2 of this review.

Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay

Chapter 1. Priorities for inclusive development in Paraguay: Summary of multidimensional analysis

Abstract

Since the turn of the century and after the country’s emergence from an economic and institutional crisis, Paraguay has returned to the path of growth. It has also set ambitious development objectives for 2030, aiming to be a country that is not only more prosperous but also more inclusive, efficient and transparent. The country’s overall development policy focuses on this ambition and is embodied in the Paraguay 2030 National Development Plan.

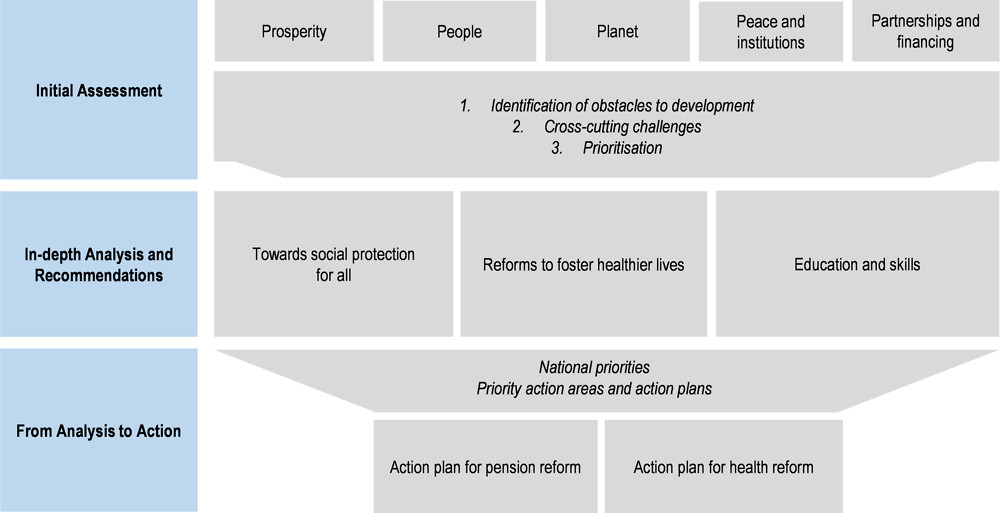

The Multi-dimensional Country Review (MDCR) aims to support Paraguay in achieving its development objectives. Volume 1 of this review (OECD, 2018[1]) assesses five areas of the country’s development process: population, prosperity, planet, peace and institutions, and partnership and financing development. Based on comparative analysis, it identifies eight priority lines of action. Volume 2 (OECD, 2018[2]) contains a more in-depth analysis and makes public policy recommendations.

This third volume summarises the main findings of the overall study and proposes specific action plans to address three priority action areas – health, pensions and education – to allow Paraguay to move towards more inclusive development. Using the main results of the previous volumes as its starting point, this chapter sets out an overall framework for priority reforms. The subsequent chapters present the main public policy guidelines on health (Chapter 2), social protection (Chapter 3), and education (Chapter 4), as well as specific action plans on health and pensions. Chapter 5 presents a dashboard of indicators to monitor the performance and implementation of the proposed reforms.

A reader’s guide to the Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay: priority areas and action plans

The purpose of the Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay is to help the country achieve its development objectives by analysing the main obstacles to development and proposing concrete solutions. Implemented between March 2017 and July 2019, the review consists of three phases and three reports: Initial assessment (OECD, 2018[1]), In-depth analysis and recommendations (OECD, 2018[2]) and From analysis to action (this volume).

To support Paraguay in achieving its development objectives, this MDCR has carried out a sequential prioritisation process culminating in public policy recommendations on social protection, health and education, as well as specific action plans on health and pensions.

The analysis of Paraguay’s performance across the five Ps addressed in the Sustainable Development Goals (prosperity, people, planet, peace and institutions, partnerships and financing) in Volume 1 of this study (OECD, 2018[1]) identified 15 obstacles to development, most of which are cross-cutting. Those 15 obstacles are summarised in eight priority fields of action:

Closing the infrastructure gap

Increasing financing flows for development

Implementing a systemic education reform

Strengthening governance

Addressing informality and the fragmented social protection system

Developing public policies with a regional approach

Updating the capacity of the statistical system

Strengthening the protection of the environment.

Combined, these obstacles leave the country facing two major challenges: to establish new drivers of sustainable growth and to place the country on a more inclusive development path. To tackle these challenges, whole-of-society strategies will be necessary. Although the national government will play a central role, it will need to harness the strengths of the private sector and civil society to continue attracting investment and fostering productive diversification and to carry out the systemic reforms needed in health, education and social protection. At the same time, the state needs to increase its capacity to lead these reforms by investing more in development, by improving the quality of public spending and by strengthening capacities in terms of the stewardship of public affairs.

After the completion of Volume 1, the OECD and the Government of Paraguay decided that Volume 2 of the Multi-dimensional Review should focus on key public policies to place the country on a more inclusive development path. In Volume 2 (OECD, 2018[2]), the analysis and public policy recommendations focus on three key areas of social policy:

Towards social protection for all

Reforming to foster healthier lives

Education and skills

The document provides an in-depth analysis of these areas and makes public policy recommendations to move the country towards achieving its development objectives.

Questions related to the capacity of the state were dealt with in detail in a Public Governance Review by the OECD, which began in parallel with the Multi-dimensional Review. The results of the Public Governance Review were published in 2018 (OECD, 2018[3]). The document included recommendations to strengthen the capacity of the Paraguayan state to establish, pilot and implement its National Development Plan. The recommendations included: (i) enhancing the strategic role of Paraguay’s centre of government, (ii) improving the link between strategic planning and budgeting, (iii) reinforcing public policies at the regional level, (iv) building a professional and efficient civil service, and (v) developing a more open, transparent, accountable and participatory government.

Figure 1.1. The Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay

Source: Authors’ work.

This third volume focuses on detailing the actions required to address the country’s development challenges. It includes chapters on the three topics dealt with in detail in Volume 2. The chapters discuss the Government of Paraguay’s priorities and its short- and medium-term plans, provide analysis on key topics identified through consultations with the Government of Paraguay and other stakeholders, as well as indicating the priority action areas that will allow the country to move forward in the direction set out in Volume 2.

It includes detailed action plans for pensions and health, both of which were prioritised in the framework of the Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay based on the Government of Paraguay’s political priorities and the progress of other planning processes, such as the development of the National Plan for Educational Transformation. These action plans were devised using the governmental learning methodology (see Box 1.1), with the participation of a wide range of stakeholders from the public sector, private sector and civil society. The process by which the action plans presented in this volume were drawn up sought to support Paraguay in generating consensus.

Finally, this volume offers a series of indicators to monitor the implementation of the proposed recommendations and action plans. Where the data are available, the indicators are linked to numerical targets and baselines so that they can be used as part of the system for monitoring Paraguay’s development policy.

Box 1.1. Public policy workshops as part of the Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay

The action plans for the Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay were drawn up in workshops using a form of the governmental learning methodology (Blindenbacher and Nashat, 2010[4]) that was adapted for Multi-dimensional Country Reviews. The methodology uses a series of techniques to encourage knowledge sharing and the willingness to introduce and support reforms in complex situations.

The workshop on Reforms for better health in Paraguay was held in Asunción on 14 March 2019 and was attended by representatives from the Ministry of Public Health and Social Welfare (MSPBS), the Ministry of Finance (MH), the Social Security Institute (Instituto de Previsión Social, IPS) and the Technical Unit of the Social Cabinet (Unidad Técnica del Gabinete Social, UTGS). The specific content of the workshop was determined by the conclusions of a high-level preparatory meeting held on November 2018 and attended by the Minister of Finance, the Minister of Public Health and Social Welfare, the Executive Secretary Minister of the Administrative Unit of the Presidency of the Republic and the President of the Social Security Institute. Attended by 60 people from these organisations, the workshop served to formulate an action plan, which is presented in this volume.

The workshop The pension system in Paraguay: reform options was held in Asunción on 28 March 2019 with high-level participation from the sector (the Minister of Labour, Employment and Social Security; the Executive Secretary Minister of the Presidential Management Unit; and representatives of the Ministry of Finance and the Social Security Institute [IPS]), who shared their view of governmental and institutional priorities. Besides civil servants from government agencies, the workshop’s participants also included pension fund managers and social partners.

Paraguay’s development ambition and the main obstacles it faces

Paraguay must leverage its macroeconomic stability to diversify its economy

The Paraguayan economy remains among the strongest-growing in the region, but with significant growth volatility due to its reliance on agriculture and livestock as leading economic activities. Despite increased diversification in recent years, over the past few decades, Paraguay’s exports have been marked by low levels of diversification and have been concentrated mainly in a small number of products, like soybeans, beef and electricity.

The much-needed economic diversification is making progress. Labour reallocation from agriculture to other sectors, especially manufacturing and services, shows that structural transformation is proceeding at pace. As a result, a number of sectors (livestock, construction, financial services) have seen their shares of value-added grow, while manufacturing has contributed an increasingly larger share to aggregate growth.

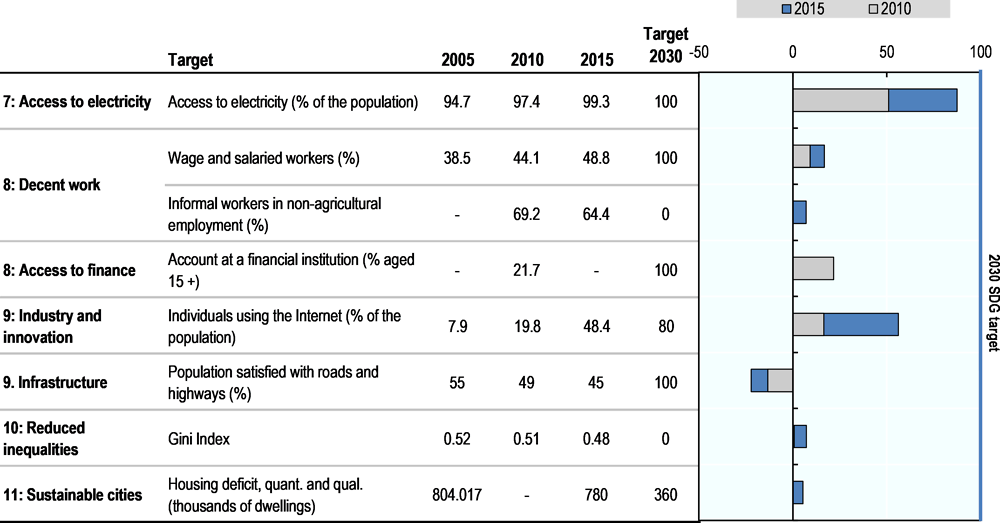

Figure 1.2. Progress in the Prosperity dimension of the SDGs

Note: The baseline for “informal workers in non-agricultural employment” is 2010 instead of 2005. The baseline for “access to finance” is 0 due to the lack of data. “Sustainable cities and communities” uses 2002 instead of 2005 and 2012 instead of 2015. The “Population satisfied with roads and highways” indicator uses 2006 instead of 2005.

Source: Authors on the basis of official national data when available, and alternatively, international data: DGEEC (2017[5]); United Nations (2018[6]); The World Bank (2018[7]); Gallup (2018[8]); International Energy Agency (2018[9]); The World Bank (2018[10]); and MH (2017[11]).

Macroeconomic stability, supported by a prudent and institutionalised monetary and macro-fiscal policy, is an excellent asset for the country’s development. Monetary policy and the inflation targeting regime have helped to control inflation volatility, with both the explicit target and the tolerance range being gradually adjusted downwards. To support the monetary policy framework, efforts to develop the financial system and the interbank market should be strengthened and liquidity conditions carefully monitored. The introduction of the Fiscal Responsibility Act and the Advisory Fiscal Council represent an important step in terms of fiscal sustainability as part of a broader package of macro-fiscal policy reforms. Implementing the act has been challenging as has been adjusting to the limits it puts to the use of counter-cyclical measures and the constraints it places on public investment.1 The fiscal framework is sound but tax collection and capital investment should be improved. Despite recent improvements, in particular in tax collection from domestic economic activity, tax collection in Paraguay is still lower than in benchmark countries, mainly due to low tax rates, but also because of evasion and informality. The government has set up a Technical economic tax commission (Comisión Técnica Económica Tributaria) that gathers public officials, experts and private sector representatives and which was tasked in November 2018 with providing input to a tax reform bill that seeks to modernise and simplify the country’s tax regime. The government has made notable efforts to contain current spending, which is reported to have declined in recent years, allowing for a slight increase in social spending and government investment. In similar fashion to the technical tax commission, the government has set up an inter-institutional commission to review the efficiency of public expenditure and make proposals to improve it. However, although it is starting to pick up, the level of investment in Paraguay has been considerably lower than in OECD and Latin American countries. Paraguay still faces significant challenges in budgetary execution and management of public investment projects. Any further government efforts to facilitate capital investment would contribute to boosting growth.

Strengthening productivity and competitiveness is also essential for sustaining long-term growth, but several challenges must be faced to achieve this. Despite government efforts and implemented measures, several challenges still remain to boost productivity and competitiveness. Paraguay channels less investment to research and development than benchmark countries, so investment and participation by the private sector in this area should be strengthened. There is also a wide scope to boost productivity by improving the quality of education and reducing skills mismatches, while high-quality infrastructure and connectivity are fundamental to raising productivity levels and improving social inclusion. The institutional and regulatory framework should be set in a way that boosts further competition, so government efforts to reduce the barriers to investment, trade and entrepreneurship are welcome.

Informality poses multiple challenges related to productive development and wealth distribution. First, it helps to sustain less productive segments and limits the potential of sectors that face competition from informal producers or unregulated imports. Second, it supports a dual economy, offering limited opportunities to a large portion of the population. Third, it restricts the potential fiscal and parafiscal revenue, limiting the state’s capacity, especially in terms of social protection.

Reducing informal employment and improving the coverage and quality of social services are essential to improve the well-being of Paraguayans

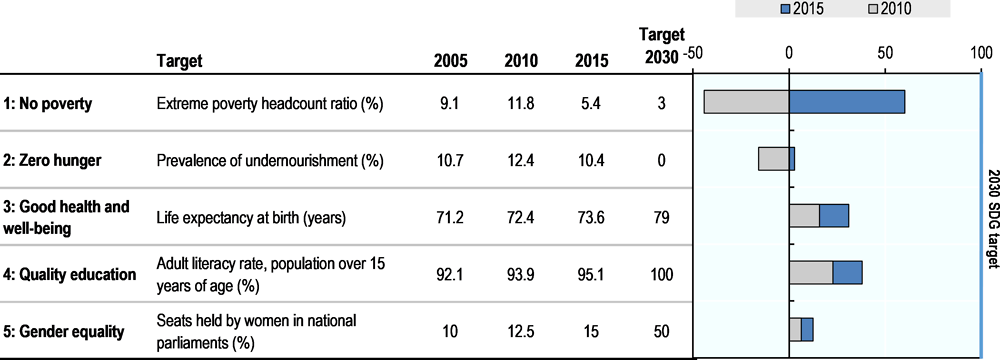

Paraguay’s good growth performance has raised incomes, but inequality remains substantial. The recent period of economic growth has raised the living standards of many Paraguayans. Macroeconomic stabilisation has also helped contain poverty by limiting food price inflation. Although poverty has fallen in Paraguay, inequality remains high and is a major concern for citizens. Geographical disparities are a major contributor to that inequality. Rural areas, for instance, have higher monetary deprivation (income poverty) and non-monetary deprivation (poor access to water, sanitation and health insurance).

Fiscal redistribution has little impact on income inequalities, but social programmes like the Tekoporã conditional cash transfers and the Adulto Mayor social pensions are visibly reducing monetary poverty, even though the programmes are still too small. In health coverage and housing development, Paraguay has made substantial progress, but the effectiveness of the social protection system is limited because it is fragmented.

Figure 1.3. Progress in the People dimension of the SDGs

Source: Authors on the basis of official national data when available, and alternatively, international data: DGEEC (2017[5]); United Nations (2018[6]); Gallup (2018[8]); Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network (2016[12]); and The World Bank (2018[10]).

Employment outcomes are quantitatively good, but job quality and informality are major challenges. Net job creation over the medium term has been good, overtaking the rapid growth in the working-age population. As a result, unemployment is low and labour-force participation remains stable at levels comparable to benchmark countries. The sector distribution of employment points to a dynamic structural transformation, with the share of agricultural jobs falling by ten percentage points in favour of services and construction. This transformation has led to a steady increase in salaried work in both the public and the private sectors. In spite of these changes, job quality remains an issue for many workers, with almost half earning less than the minimum wage. Informality poses a challenge due to the absence of a suitable social protection regime (pension and health insurance) for self-employed workers. The share of informal employment has fallen by one percentage point per year on average in the past five years, a relatively slow pace given the structural transformation taking place and the prevalence of informality. While employment protection legislation is not particularly stringent, high minimum wages relative to market wages and the social security contribution rules make formalisation expensive for employees.

In education, coverage has expanded, but challenges remain in both early childhood and secondary education and in terms of educational outcomes. Paraguay’s adult-education attainment rates are among the lowest of the benchmark countries, with 8.7 years of education on average. The cohorts educated since 1990 have significantly higher attainment rates. Although limitations in statistical capacity hamper the analysis of access to education, survey data suggest that access to primary and lower secondary education is nearly universal, with the exception of indigenous areas, thanks in part to previous education reforms aimed at expanding coverage. Gaps in access to school remain significant for pre-primary education and upper secondary education, and in both cases, gaps between rural and urban areas remain wide. Progress in recent years has been notable in secondary school and especially in tertiary education, where access has grown rapidly. Gross enrolment rates of 35%, however, remain low compared with those of benchmark countries. The quality of education remains a major challenge. Learners underperform with respect to the expected proficiency described in the national curriculum (as is the case for almost three-quarters of grade 3 students) and with respect to the performance levels of the benchmark countries in the region. The main challenges that the education sector faces are under-trained teaching staff and inadequate infrastructure. The National Fund for Public Investment and Development (Fondo Nacional de Inversión Pública y de Desarrollo, FONACIDE), created in 2012, channels royalties from the Itaipú binational plant to education, research and social infrastructure. FONACIDE has been instrumental in sustaining the increase in funding to support education, especially through investment in schools. In spite of a recovery in public expenditure in education and the earmarking of funds for social infrastructure, limited absorption capacity is a constraint on the speed at which these challenges can be overcome.

The efficiency of social-service delivery is limited by the fragmented social protection system and informality. The coverage rate for contributory social security is limited to 22% for the pension system and 29% for health insurance due to the prevalence of informal employment and the contribution rules for self-employed workers. The pension system consists of many different regimes with very little regulation and varying states of financial soundness. The generous provisions of the general regime are in stark contrast to the low coverage and the expansion of the non-contributory pension financed by the general budget. The health system is also fragmented in terms of both its funding and its service delivery. High out-of-pocket payments create obstacles to effective use of health services and reinforce inequalities in people’s state of health. Social assistance and income support are also fragmented, with overlapping objectives and differences in targeting methods. However, given the relatively weak impact of transfers on monetary poverty, there is potential for greater effectiveness through institutionally co-ordinated action. To succeed in addressing informality, co-ordination in programme design, implementation and enforcement is a necessity.

Towards better management of natural resources

Paraguay’s geography has given it one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world. With access to a large tropical forest and vast water resources, the country provides abundant resources for agriculture and livestock. Thanks to hydropower, Paraguay has one of the cleanest energy mixes in the region, allowing it to maintain low carbon emissions and control its air pollution levels. Total greenhouse emissions are also relatively low. However, the current economic expansion, largely based on the use of land for agriculture and livestock, has put increasing pressure on the country’s environmental resources. Deforestation remains one of the most critical issues in terms of environmental sustainability.

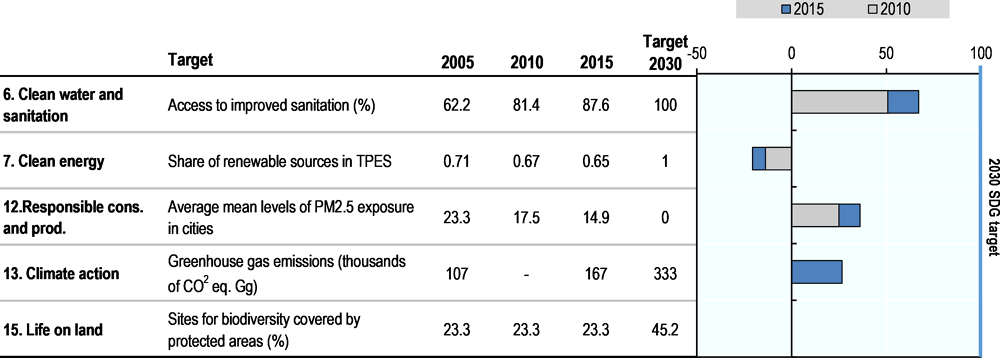

Figure 1.4. Progress in the Planet dimension of the SDGs

Note: The “Greenhouse gas emissions” indicator uses 2012 instead of 2015. The “Population satisfied with roads and highways” indicator uses 2006 instead of 2005.

Public services, including water, sanitation and waste management, are relatively cheap, but a large part of the population still have limited access, and regional disparities in the quality and distribution of these services persist. The rapid urbanisation process has increased pressure on Asunción and medium-sized cities, and shortages of water and its poor quality are major concerns for the authorities, particularly in urban areas. In rural areas, natural-disaster prevention has gained importance after two recent episodes where agricultural production was affected.

To maintain the current economic momentum and guarantee that it benefits the entire population, Paraguay needs to incorporate the sustainable use of environmental resources and capabilities into its development agenda. There are considerable needs in terms of environmental protection that are not being met. The regulatory framework against deforestation is insufficient and is not being implemented, and more support to strengthen the institutional setting is needed, particularly at the local level. Waste management is another issue of concern, with landfilling being the primary disposal method.

With access to abundant clean hydropower, Paraguay could be at the forefront of environmental policy in the region, promoting renewable energy, building energy-efficient technology, and improving energy utilisation in transport, among other areas. Only 29% of total energy consumption, however, comes from this clean electricity, the bulk coming from fuel and biomass. Transport, which accounts for nearly 90% of Paraguay’s greenhouse gas emissions, is one area where improvements could be made, such as through the introduction of electricity-based systems and incentives to reduce biomass consumption in the industry sector. Improving land management and administration will be fundamental to the implementation of a strategic plan for the environment.

Strengthening democracy and moving towards more effective and transparent public management

Paraguay’s vision for 2030 is that of a state grounded in democracy, solidarity, subsidiary, and transparency that promotes equal opportunities. Governance institutions in the country are still undergoing fundamental transformations. Today, democracy in the country is still in a consolidation phase. Fewer than half of Paraguayans consider democracy to be preferable to any other form of government and fewer than a quarter are satisfied with how democracy works in the country. Satisfaction with democracy almost doubled between 2006 and 2015 in spite of several episodes of political instability, which tested the resilience of the country’s democratic institutions. Further strengthening the justice system is crucial for ensuring the rule of law. Issues related to justice are linked to a number of constraints, including the range of functions that the Supreme Court fulfils on top of its core function of administering justice, the relatively small number of judges, and the pervasive influence of entrenched informal institutions that limit judicial independence.

Perceived personal insecurity is comparatively high in Paraguay, although violence is unequally spread and more prevalent in border areas. Homicide rates have fallen considerably in the past years, and homicides are concentrated in a small number of departments in border areas. Despite ongoing efforts, smuggling, drug trafficking, counterfeiting and money laundering continue to take advantage of porous borders and weak law enforcement.

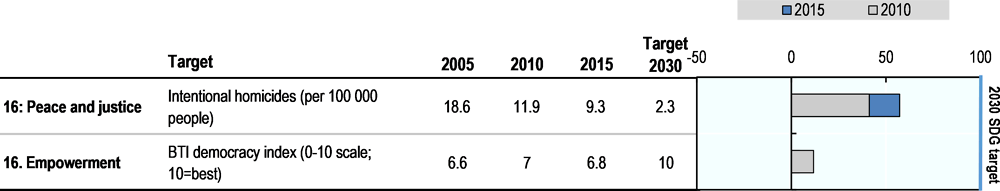

Figure 1.5. Progress in the Peace and Institutions dimension of the SDGs

Note: The BTI democracy index uses 2006 instead of 2005 and 2016 instead of 2015.

Source: Authors on the basis of official national data when available, and alternatively, international data: United Nations (2018[6]); The World Bank, (2018[10]); and Stiftung Bertelsmann (2008[13]).

The capacity of government is limited by its relatively small size compared to other countries. Government expenditure reached 25% of GDP in 2015, compared with 34% in LAC countries and 45% in OECD countries. Public employment is also relatively low at 9.8% of total employment compared to 12% in LAC countries and 21% in OECD countries. Strategically planning for the right mix of skills in the civil service in the years to come will help the government meet strategic objectives as well as increase efficiency, responsiveness and quality in service delivery. The government also needs to improve service delivery and maintain a commitment to inclusiveness, transparency and efficiency in order to raise levels of trust in government, which remain low. Ensuring satisfaction with service delivery is a significant challenge for Paraguay.

Paraguay has begun developing a comprehensive and coherent integrity system in which transparency plays a major role, but ensuring the system’s effectiveness remains a big challenge. Citizens’ perceptions of corruption are higher than in other countries in the region and have changed little in the past ten years. The government has taken a number of initiatives as part of a National Plan for the Prevention of Corruption (Plan Nacional de Prevención de la Corrupción). Among them, a key institutional pillar is the creation of a national anti-corruption agency (Secretaría Nacional Anticorrupción, SENAC), which has successfully co-ordinated all institutions in the executive branch to establish anti-corruption units and has raised awareness about public-sector integrity issues. Transparency efforts are crucial in the fight against corruption. Paraguay has made determined efforts against corruption in public procurement by making all tendering and procurement information available online and by including a whistle-blowing function on the procurement agency’s electronic platform. The mandatory provision of information on the use of public resources, including the remuneration of civil servants, and the law on transparency and access to information adopted in 2014 also underpin the government’s strategy for increasing citizen oversight of public affairs. Significant challenges remain, including ensuring there is the political will to follow through on complaints raised (only a small proportion have so far led to administrative or judicial investigation), addressing limitations in the scope of SENAC’s action (the organisation focuses on embezzlement but not other forms of corruption), and addressing the absence of a specific provision for whistle-blower protection.

The open-government strategy has spearheaded a whole-of-government approach to promote transparency, empower citizens, fight corruption and harness new technologies for strengthening governance. The action plan for the 2014-16 period was conceived through a participatory approach with 12 government institutions and 9 civil-society organisations. The third action plan for the period 2016-18 strengthened this model of participation and achieved the inclusion of more than 54 public institutions and 62 civil society organisations. The fourth action plan for the 2018-20 period innovated with the extensive use of social networks and brought together more than 60 public institutions and 100 civil society organisations. Progress in the form of legal and institutional reform has been notable and Paraguay ranks fourth among Latin American countries with information in the OECD Index on Open Government Data, tanking above the OECD average. While considerable efforts have been made to enhance openness by making information available, challenges remain to tailor public information to citizens’ needs and to strengthen accountability mechanisms.

More resources need to be channelled towards development

The analysis shows that financing flows for development are relatively limited in Paraguay compared with the benchmarking countries and the OECD. Given the country’s prudent fiscal stance and low reliance on public debt, public financing comes mostly from fiscal space. Fiscal space is helped by idiosyncratically high non-tax revenues from the two binational power plants but is constrained by relatively low tax revenues as a result of low tax rates and evasion rates that are above the regional average. The weight of non-discretionary expenditure, which represents almost half of total public expenditure, also limits fiscal space. The country has recently made notable progress on both fronts. Tax revenues have increased and the country has implemented major fiscal reforms, including the progressive implementation of the personal income tax since 2012, the expansion of VAT to the agricultural sector and the introduction of a tax on profits from agricultural activities in 2014. Measures to limit the growth of the public wage bill and to reduce the weight of non-discretionary expenditure have allowed public investment and capital expenditure to grow at much faster rates than current expenditure.

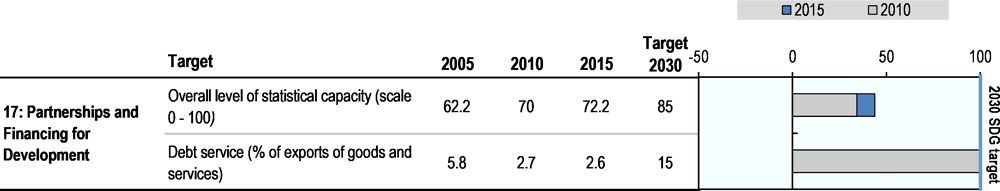

Figure 1.6. Progress in the Partnerships and financing dimension of the SDGs

Source: Authors on the basis of official national data when available, and alternatively, international data: DGEEC (2017[5]); United Nations (2018[6]); The World Bank (2018[10]) and MH (2017[11]).

Private development flows, at 5.5% of GDP, are relatively modest compared with public financing flows of 11.8% of GDP. Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows remain modest, at around 1.3% of GDP between 2014 and 2017, but the net flow of FDI has continued to grow in the country, despite the overall downward trend in the region due to national crises in neighbouring countries and the moderation of commodity prices. The recent dynamism in FDI flows has been partially driven by efforts to create an attractive regulatory framework and to attract investment. These measures have contributed to transforming the composition of investment, with a notable increase in the maquila industry, additional diversification in countries of origin, and the development of sectors with greater job creation prospects, such as automotive components.

The stability of the Paraguayan financial system is a major asset for development, but it needs to be further developed and become more inclusive. The banking sector is well capitalised, with sufficient access to sources of deposit financing, and it is highly profitable. Credit growth has accelerated in recent years, with 26% average banking credit growth over the 2005-15 period, and banking credit to the private sector reached 43% in 2015. To better finance development, regulations need to be strengthened for the entire financial sector, not just the banking sector. Moreover, high interest-rate spreads and reliance on short-term finance reflect constraints on the quality and availability of creditor information as well as the reliance on consumption credits. Financial inclusion is still very low and unequal in the country in spite of rapid growth in credit.

Towards a more inclusive and sustainable development path

The multi-dimensional analysis reveals two major cross-cutting challenges for Paraguay’s development. Paraguay needs to buttress sources of sustainable growth in the medium term on the one hand, and to place the country on a more inclusive development path on the other hand. Three complementary strategic priorities can be identified from Volume 1 of the Multi-dimensional Review:2 (i) to create the conditions for a sustainable structural transformation of the economy, (ii) to promote social development, and (iii) to increase the state’s capacity to steer the economy and the country’s development. Making progress in these three directions will require action in eight priority areas:

Closing the infrastructure gap

Increasing financing flows for development

Implementing a systemic education reform

Strengthening governance

Developing public policies with a regional approach

Updating the capacity of the statistical system

Addressing informality and the fragmented social protection system

Strengthening environmental protection

The strategic implications of these areas are described in this section. This report focuses on describing concrete actions in a series of specific areas linked to the state’s capacity to promote social development.

Creating the conditions for a structural transformation of the economy

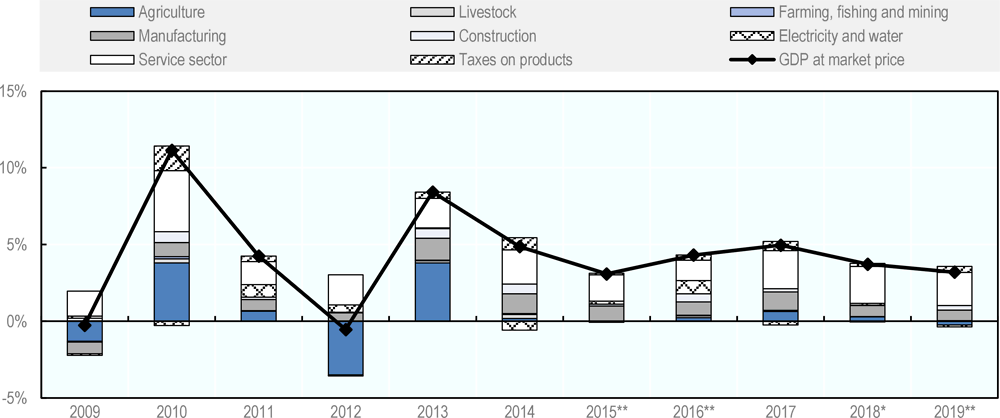

Paraguay’s dependence on agricultural exports is one of the causes of its volatile economic growth and the burden that economic growth has placed on the environment. The rebasing of national accounts to the 2014 base year has adjusted the dial regarding productive diversification. Indeed, economic growth has been propped up by the sustained growth of certain sectors, especially manufacturing, the importance of which was understated in the old series.

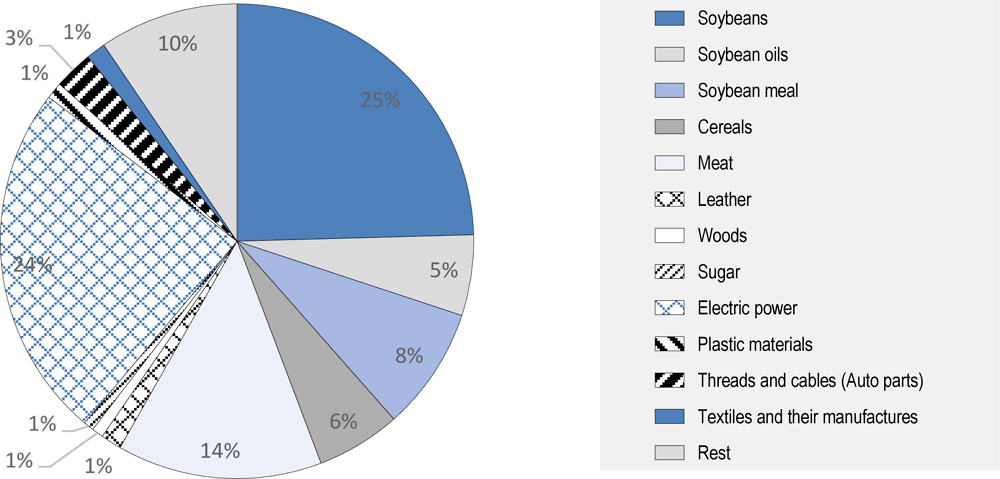

Paraguay’s export basket remains concentrated in agricultural products, but new sectors are emerging. Soy-based products, meat and cereals accounted for 58% of Paraguayan exports in 2017. In practice, much of the manufacturing activity in the country involves processing agricultural products. Some sectors have recently made breakthroughs, however, especially in the context of the maquila industries, including the production of textiles and motor vehicle parts (especially cabling). These sectors provide an opportunity to attract FDI and develop industrial capacity, but they are very labour-intensive and can relocate easily, so it is important to pursue capacity building in the corresponding value chains.

Figure 1.7. Diversification has allowed the Paraguayan economy to continue growing

Note: (*) Preliminary data; (**) Projection.

Source: Calculations based on the Statistical annex to the economic report (BCP, 2019[14]).

Figure 1.8. Main Paraguayan exports by product

Carrying out structural transformation requires creating attractive conditions for investment that go beyond the regulatory framework. This means developing infrastructure, developing the financial system to channel resources to the private sector and developing the education system in a way that is better suited to the current and future needs of the economy. Paraguay has drawn up a regulatory framework to develop infrastructure projects that involve the private sector through turnkey models and public-private partnerships. It has also created a well-developed investment system. Prioritising investment in infrastructure, however, should be more closely linked to economic and social priority objectives.

Promoting social development

Paraguay has made major strides in combating poverty and should continue its efforts while creating the conditions to improve the well-being of the population as a whole. As detailed in the National Development Plan, this means providing high-quality public services that protect citizens’ social rights to health, education, housing and decent work.

Good-quality public services can also alleviate inequality by ensuring equal opportunities. To achieve this, the quality of health care during the early years of life and access to pre-primary education are vital, as they reduce the gap associated with socio-economic origin.

This report proposes a series of measures associated with improved provision of education, health and social security. A common feature of these three sectors is that their provision is highly fragmented and gaps exist in terms of the regulatory framework and stewardship. A strategic vision is therefore essential in order to start a reform process that will be effective and peaceful.

Paraguay has begun to roll out an integrated, rights-based social protection system that is gender-sensitive and has a life-cycle approach (see Chapter 3). This significant breakthrough reflects a different understanding of social policy that goes beyond focusing solely on monetary poverty.

Informality poses a major challenge to Paraguay’s development, particularly in terms of the country’s social development, since it limits the scope of the social security system. Since government resources are directed primarily towards the most vulnerable, the middle classes are largely unprotected against life risks. Informality is also a challenge for productive development since it can impede more efficient use of resources and can even stymie the growth of potentially competitive companies and contribute to normalising evasion and smuggling.

Raising the capacity of the state to steer the economy and development

Since its transition to democracy in 1989, modernisation of the state of Paraguay has tended to take place in episodes when specific institutions were set up with limited mandates. The institutional fragility of certain state agencies and large regulatory voids limit the state’s capacity to steer the country’s economy and development.

In certain areas, Paraguay needs to create a coherent normative framework supported by a strong institutional setup. Pension providers, for instance, are not regulated or supervised, so the population have limited trust in the system and the economy cannot harness pension savings. Environmental protection has been further strengthened by the decision to convert the Secretariat for the Environment into the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development.

The state’s capacity is also hindered by corruption and perceived corruption. Regulations on integrity should continue to be developed, strengthened and implemented through SENAC. Although the commitment to transparency has empowered civil society to respond to cases of corruption and abuse of authority, legislative and judicial bodies have been slower to deal with such cases.

Mobilising domestic resources for development would help the government to better address the challenges that the country faces. Tax revenue accounts for 17.5% of GDP, compared with 22.7% for the Latin America and the Caribbean region and 34.3% for the OECD countries. Given the investment needs, especially for infrastructure, and the social investment needs, which require substantial current expenditure, it is essential to mobilise more domestic resources. This will require a tax reform, with a component limiting exemptions and reducing tax expenditure, and reforms to raise the quality of public expenditure, including rationalising spending in certain areas, such as social protection (see Chapter 3). Private investment also needs to be promoted by creating an environment conducive to productive transformation and redirecting effective incentives for investment from traditional sectors to the knowledge economy that the country would like to move towards.

Developing statistical capacity should be a priority in order to strengthen results-based management. Paraguay should assign and distribute tasks within the national statistical system through a clear policy framework, ensure the professional independence of the statistics authority (the DGEEC), and ensure that the agencies that release statistical information have adequate human and technical resources, in line with the Recommendation of the OECD Council on Good Statistical Practice.

Finally, many areas of public policy do not have territorial declensions. Centralised governance can make it difficult for both line ministries and agencies to generate local solutions and can hinder interministerial solutions. Although local development councils set up under the National Development Plan could help with adapting policies to local conditions, local bodies need to improve their technical capacities.

Implications for the National Development Plan

The Paraguay 2030 National Development Plan recognises three strategic axes: 1. Poverty reduction and social development, 2. Inclusive economic growth, and 3. Paraguay’s integration in the world. It also defines four cross-cutting themes: (i) equality of opportunity, (ii) efficient and transparent public management, (iii) territorial development and land management, and (iv) environmental sustainability. The combinations between the three axes and the four strategic lines result in 12 strategies.

The eight priority action areas identified in the Multi-dimensional Review fit squarely into the National Development Plan, although they may merit adjustments in specific areas. For instance, in the National Development Plan, the strategy to promote the value of environmental assets contains a whole series of lines of action for sustainable production but only two goals related to the energy mix. This is an area that should be strengthened from a conceptual viewpoint. Another example is the need to territorialise public policies, which the National Development Plan mentions, but only in the area of production.

In practice, the key objectives of the National Development Plan play an important role in shaping public policies. The budgetary classification was aligned with the structure of the National Development Plan and an aligned results-based budget system was set up. This meant that each budget line is associated with a main objective, thus revealing overlapping programmes such as the institutional fragmentation of anti-poverty measures. The budgetary classification also provides a starting point for results-based management.

The broad strategies of the National Development Plan, however, do not necessarily reflect the strategic orientations of reforms. Each institution’s strategic plans and programmatic directions are not systematically aligned with each other or with the National Development Plan (OECD, 2018[3]). Some important cross-cutting initiatives, such as the social protection system and the national formalisation strategy, are not directly accommodated in the National Development Plan, as they have their own transversal logic. The new approach to social protection should be fully reflected in the National Development Plan, which to date had as the single target in the area to make social security universal (an aim that is difficult to achieve if social security is understood as referring to the contributive social protection branches).

The efforts made to align the budget with the National Development Plan make the level of effort across strategies visible, but they do not necessarily contribute to the prioritisation of spending or public action. By attributing each budget line to the National Development Plan objectives and strategies, the government attributes current operating costs to specific elements. For example, public debt service in 2018, was attributed to the competitiveness and innovation strategy. The exercise does, however, reveal the efforts invested in achieving some of the objectives where adjustments are warranted. The cross-cutting line for the environment, for instance, received around 2% of the 2018 budget, and that is including housing production costs and defence logistics costs, among others. Average spending on environmental protection by European Union countries is 0.8% of GDP.

Strategic planning in Paraguay should leave room for drawing up priority programmes with sequential objectives and costed actions. These can be accommodated in the National Development Plan itself or at an intermediate level between the National Development Plan and the annual operating plans. They should also be linked to the medium-term spending plan. This would allow Paraguay to assign real priorities to reform programmes that could transform the country’s economy and society.

Public policy orientations for reform in health, social security and education

The second and third phases of the Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay focus on three key areas to make the country’s development path more inclusive: social protection, health and education. Volume 2 provides an in-depth analysis of these key areas and makes a series of public policy recommendations to help the country achieve its objectives in those areas. This third volume presents specific action plans for selected domains within the three key areas.

Overcoming fragmentation and accelerating reform can improve the health of Paraguayan citizens

Paraguay has made significant progress in key health outcomes but faces a double burden of disease. In recent years, Paraguay has been increasing healthcare access through primary healthcare units (Unidades de Salud de la Familia), but it has a long way to go before the entire population will be covered. The challenge is substantial since Paraguay’s epidemiological transition has created a double burden for the health system, with the country facing new challenges, in addition to age-old problems that it has not resolved. This epidemiological transition has been accompanied by changes towards sedentary lifestyles and unhealthy alimentary habits among the population, which has deteriorated risk factors, partly driven by social determinants of health. To rise to the challenge, Paraguay will need to redouble its efforts and strategise to successfully remodel its national health system (OECD, 2018[2]).

The fragmentation of the health system limits its capacity, quality of service and efficiency. Health service delivery is segmented and uncoordinated. The three subsystems are, for the most part, vertically integrated: each of them raises its own revenue, manages its own funds and delivers services independently. Each subsystem covers different segments of the population, mainly based on their employment status and their capacity to pay. They provide different sets of services and each segment of the population receives different benefits and a different standard of quality. Because the system is fragmented in this way, it is very difficult for the Ministry of Public Health and Social Wellbeing (MSPBS) to carry out its stewardship duties. Furthermore, the system’s regulatory framework and supervisory bodies are very weak and its information management is inefficient, which limits the available evidence base for the formulation of policy and makes the continuity of care difficult. Funding flows are fragmented and inadequate. Revenues earmarked for different population groups are held in separate pools, with no potential for cross-subsidy between them, so the health system relies heavily on households’ out-of-pocket expenditure.

Important challenges remain in the three dimensions of health coverage, namely population coverage, service coverage, and financial coverage (or financial protection). Access to health care is still not universal and insurance coverage is limited, especially among the most vulnerable people. Many Paraguayans incur catastrophic health expenses and expose themselves to other financial risks, mainly due to the system’s heavy reliance on out-of-pocket expenses by users. To deliver on its commitment to universal health coverage, the country needs to expand access to health services and insurance coverage and increase financial protection. On the funding side, Paraguay should consider ways of reducing the share of out-of-pocket health expenditure. Establishing a well-defined guaranteed health package would contribute to this goal. Paraguay also needs to develop the tools to ensure the quality of healthcare throughout the system.

To ensure there is sustainable progress in all dimensions, there needs to be a systemic reform based on a shared vision for the future. In particular, a national dialogue is needed to reach agreement on a vision for the future of the Paraguayan health system. Building on existing efforts to develop health networks around primary care, Paraguay should establish the conditions for the emergence of a more integrated health system by making inter-agency agreements the norm, moving towards the separation of stewardship, purchasing and service-provision functions currently within the purview of the MSPBS, and developing the necessary public institutions in the health sector. To achieve universal coverage, the health system needs to secure sustainable funding and ensure it is properly funded and more efficiently run, with stronger stewardship (OECD, 2018[2]).

The health funding strategy must be sustainable and must secure sufficient resources. Diversifying the sources of funding and reducing the share of users’ out-of-pocket health spending could help ensure the sustainability of health funding. Moreover, pooled funding mechanisms should be established to cover at least the key contingencies. Health cover for civil servants and employees of the state should transition to a social insurance scheme.

Strengthening governance is necessary to steer the health system towards universal coverage. To strengthen the stewardship entities, Paraguay needs to strengthen the implementation of the legal framework for the governance of the national health system. It also needs to strengthen and streamline its legal and regulatory bodies. Paraguay needs to invest more in the development, inter-connection and interoperability of information systems for the health system to deliver better statistical information and to support continuity of care. Furthermore, it needs to define a package of health benefits so that it can progress strategically towards universal coverage.

To improve how the resources are used, the health system needs to become more efficient. To improve its efficiency, the health system first needs to become less fragmented and to establish payment systems strategically. To make the system more integrated, it is necessary to review existing inter-agency agreements and set up a framework for creating new and better agreements. At the same time, Paraguay needs to design the purchase and procurement of health services strategically, taking into account the incentives generated by payments systems. Implementing strategies for purchasing medicines and programmes to prevent disease and promote health could help to reduce the system’s operating costs. At the same time, the government needs to boost efforts to direct the national health system towards integrated networks based on primary health care. In the long run, separating stewardship, purchasing and service provision functions would allow for better-aligned incentives and more pooling of funds and risk.

Achieving social protection for all Paraguayans requires larger investments and a systemic approach.

Despite notable progress in fighting poverty, many Paraguayans are not covered by the social protection system. Expanding social spending has made it possible to increase access to primary healthcare, the conditional cash transfer programmes are having a real impact on poverty, and the Adulto Mayor (Older Adult) social pension has made it possible for nearly half the over-65 population to collect a pension. However, only 24.5% of Paraguayans are covered by social protection – i.e. they pay into social security or receive a benefit – which is less than half the average for Latin America. The coverage gap affects not only the contributory system, which only 21% of the population contributed to in 2016, but also the non-contributory system: less than 30% of poor households receive transfers from one of the flagship social assistance programmes targeting children and older adults.

Social protection is highly fragmented, which hinders the system’s coverage and governance. Non-contributory social assistance is spread across 35 programmes under the responsibility of multiple agencies, including sector-specific ministries and organisations targeting specific groups. The contributory and non-contributory systems are evolving in parallel both strategically and operationally. Past attempts at co-ordination, which focused on anti-poverty actions, had limited scope and success, but they made it possible to create vital tools for co-ordination, such as a single targeting instrument, a beneficiary register and information systems to track results and activities. Nonetheless, there is still a sizeable gap between contributory and non-contributory programmes.

A systemic approach to social protection is needed in order to protect more citizens against multiple life risks and promote their productive inclusion. Paraguay has launched a series of reforms to put in place a social protection system and provide it with the leadership it had lacked. These reforms should allow co-ordination of efforts, both strategically and on the ground. In the medium term, they should also promote rationalisation of the set of social protection programmes, to bolster their effectiveness and efficiency.

The pension system exemplifies the challenges facing the entire social protection system in terms of coverage, funding, fragmentation and governance. Social security covers only a small portion of the population, with very little progress in recent years. This low coverage is partly due to the country’s large informal economy and the lack of an effective strategy for bringing self-employed workers into the system. Funding involves a dual challenge: ensuring stability in a contributory system that is generous despite relatively low contributions and low coverage, and the need for strong government funding to guarantee coverage of vulnerable older adults, in addition to the government funds needed to sustain some segments of the contributory system.

This volume presents an action plan for pension reform with four main priorities:

Expanding pension coverage. This requires developing a true coverage expansion strategy. This should include groups that are excluded de jure, such as public-sector contract employees, and groups that are excluded de facto, such as self-employed or domestic workers, for whom no existing regimes provide sufficient incentive. On the other hand, this strategy should include incentives for the formalisation of employment and for compliance, simplifying processes, providing information and making enforcement more effective. Lastly, the country needs to expand the social pension to its target population.

Parametric reforms for a fairer, more sustainable pension system. In their current state, the Paraguayan pension systems are unequal and unsustainable. The country’s large young population has allowed Paraguay to maintain a generous pension system for the relatively small older population, with much higher nominal replacement rates than the average for OECD countries, and relatively low contribution rates. To ensure the systems’ viability and equalise the effort in terms of workers’ savings, it is necessary to unify parameters and strengthen the link between benefits and contributions.

Better integration of the pension system. In the long term, several pension funds and regimes could merge to limit administrative costs and guarantee equity. Until then, steps should be taken towards a systemic vision of the pension system that takes into account not just the various contributory funds but also all non-contributory pensions, to close coverage gaps without creating adverse incentives.

Strengthen governance of the pension system. It is necessary to establish a mechanism for seeking consensus, to allow all of the necessary reforms to take place in a calm, responsible way. There is an urgent need for regulation and supervision of all pension providers, which will not only make it possible to ensure high-quality management but also generate resources for development and investment.

Reforms in the education and skills system are necessary to foster inclusiveness and access to better jobs

In recent years, access to education has expanded markedly, and primary education is almost universal. However, challenges remain, in particular in supplying pre-primary education and in increasing completion rates, especially for secondary education. A total of 10% of 14-year-olds do not attend school, and that rises to 28% among 17-year-olds. Socio-economic status and geographical area remain strong determinants of completing secondary education, perpetuating inequalities.

The quality and relevance of the education and skills-training system remain a core challenge. Most students in Paraguay do not attain basic skills. Students’ performance varies markedly by socio-economic status, geographical location and language. Dropout, poor learning outcomes and the low relevance of skills learned complicate the transition to the labour market, especially for those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Eighty per cent of those who do not finish secondary school and work have an informal job and six out of ten young people from households in extreme poverty do not work, study or follow an education at the age of 29.

For Paraguay to foster inclusiveness, create access to good-quality jobs and achieve its social and productive development objectives, it must transform its education and skills system by making progress in a number of key areas. Specifically, it needs to:

develop a national pact on education that lays the foundation for future reforms;

expand education coverage, supporting access in remote areas and among disadvantaged people, expanding pre-primary education, and implementing policies to favour school retention, thus avoiding grade repetition and dropouts;

improve learning and the quality of education by focusing on teachers, redesigning their initial training and career paths and improving the measurement of outcomes and performance while linking it to professional development;

modernise curricula based on a national qualifications framework designed with input from the production sector to ensure that it is better adapted to the needs of the economy and that it facilitates a wider range of training paths;

strengthen the technical and vocational education and training (TVET) system, establishing a government institution to co-ordinate all the stakeholders, improving quality-assurance systems and designing job-oriented training paths; and

improving the match between supply and demand for skills by adopting active labour market policies with greater scope, better information and careers guidance for students, a closer connection between training and the production sector, and a more developed system for analysing the labour market and anticipating needs.

References

[14] BCP (2019), Anexo estadístico del Informe Económico [Statistical annex to the economic report], Banco Central del Paraguay, Asuncion.

[13] Bertelsmann, S. (2008), Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2008.

[4] Blindenbacher, R. and B. Nashat (2010), The Black Box of Governmental Learning: The Learning Spiral - A Concept to Organize Learning in Governments, The World Bank, Washington DC, http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-8453-4.

[5] DGEEC (2017), Encuesta Permanente de Hogares [Permanent Household Survey] (database), Dirección General de Estadística, Encuestas y Censos, Fernando de la Mora, http://www.dgeec.gov.py/datos/encuestas/eph.

[8] Gallup (2018), Gallup World Poll, https://www.gallup.com/analytics/232838/world-poll.aspx.

[12] Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network (2016), Global Burden of Disease Study.

[9] IEA (2018), IEA database, International Energy Agency, Paris.

[11] MH (2017), Reporte Nacional de Inclusión Financiera 2017, Ministerio de Hacienda de Paraguay, Asuncion.

[1] OECD (2018), Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay: Volume 1. Initial Assessment, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264301900-en.

[2] OECD (2018), Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay: Volume 2. In-depth Analysis and Recommendations, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264306202-en.

[3] OECD (2018), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Paraguay: Pursuing National Development through Integrated Public Governance, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264301856-en.

[7] The World Bank (2018), Sustainable Energy for All (SE4All) (database), The World Bank, Washington D.C., http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?s.

[10] The World Bank (2018), World Development Indicators (database), The World Bank, Washington D.C., http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators.

[6] United Nations (2018), SDG Indicator system, United Nations, New York, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/database.

Notes

← 1. The fiscal responsibility law fixes a deficit ceiling of 1.5% but escape clauses allow deficits of up to 3% in case of economic recession.

← 2. This section divides one of the strategic priorities identified in Volume 1 into two parts, since the first volume of the Multi-dimensional Review uses a single title for guidelines (ii) and (iii).