This chapter brings together the main recommendations and priority areas of action for the education and skills system based on the analysis in Volume 2 of the Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay. The country has made substantial advances in several facets of the education system. The education and skills system faces three major challenges: improving coverage and completion rates, especially in pre-primary and secondary education and for certain socio-economic groups; improving the quality of learning outcomes, which involves changing how teacher training and teaching careers are managed; and ensuring that both general and technical training are better matched to the economy’s demand.

Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay

Chapter 4. Priority areas for action in education and skills formation

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Transforming the education and skills system in Paraguay is vital to promoting inclusiveness and access to better-quality jobs, and to achieving Paraguay’s development objectives. The low rates of school completion (especially secondary school) among the more disadvantaged socio-economic groups sustain the high levels of inequality in the country. In terms of growth, the necessary diversification of the economy needs workers with 21st-century technical and human skills.

Volume 2 of this Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay (OECD, 2018[1]) analyses the performance of the education and skills system. It identifies three main challenges. First, persistent obstacles to universal access to education, especially at the pre-primary and the secondary level, and progression and completion rates that remain unsatisfactory. Second, learning outcomes are unsatisfactory, even though Paraguay has enough teachers. Third, judging by outcomes in the labour market, the transition from school to work is problematic due to the dropout rate and the low relevance of the acquired skills.

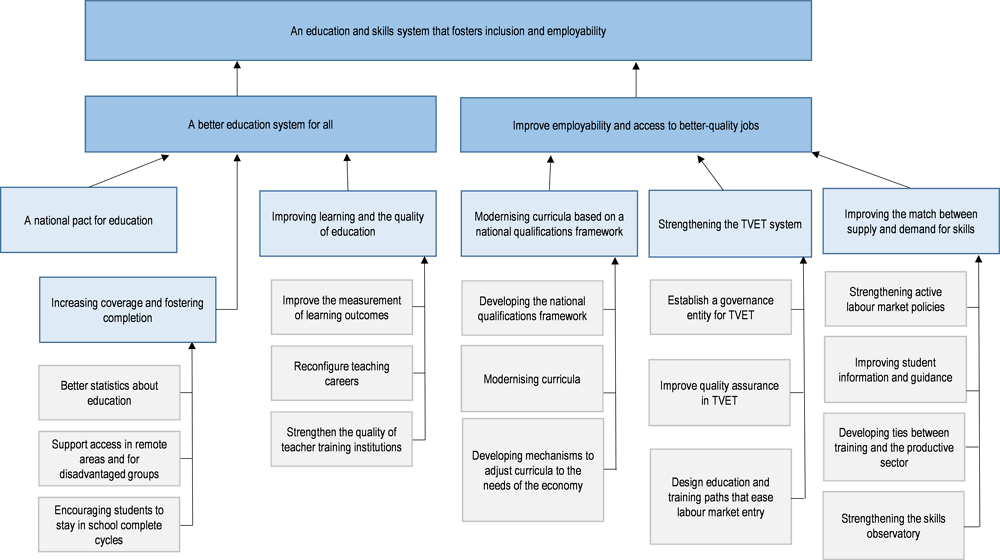

Paraguay is giving new impetus to educational reform by formulating an educational action plan for the administration’s term of office (MEC, 2019[2]) and by preparing a National Plan for Educational Transformation with a medium-term horizon of 2030. In this context, this chapter takes up the main recommendations on education and skills training from the Multi-dimensional Review (summarised in Figure 4.1), highlighting priority areas of action as an input for the process of designing reforms for the education system and vocational education.

Figure 4.1. Priority areas of action in education and skills training

Source: Authors’ work.

Policies to help create a better education system for all

Main challenges in the field of education

In recent years, access to education has expanded markedly, and primary education is almost universal. However, challenges remain, in particular in supplying early childhood education and in increasing completion rates. A total of 10% of 14-year-olds do not attend school, and that rises to 28% among 17-year-olds (OECD, 2018[1]). Socio-economic status and geographical location remain strong determinants of completing secondary education, which perpetuates inequalities.

The quality of the education system remains a core challenge. Currently, over a third of students perform at the lowest skill level in national evaluations. Most students in Paraguay do not attain basic skills (i.e. skill level 2 in the PISA-D tests). Students’ performance varies markedly by socio-economic status, geographical location and language, while there are no substantial differences between male and female students.

The skills taught have low relevance, which complicates the transition to the labour market. This transition is even more complicated for people from disadvantaged backgrounds. Indeed, 80% of those who do not complete upper secondary schooling are in informal employment and six out of ten young people from extremely poor households1 are neither working nor in an educational or training programme by age 29.

Priorities of the Ministry of Education and Science

The Ministry of Education and Science (MEC) formulated its 2018-23 Educational Action Plan in early 2019. It is structured around three complementary lines of action:

1. Ensuring equal access opportunities and guaranteeing the conditions needed for timely completion by students of different educational levels and modalities

2. Quality of education in all educational levels and modalities

3. Managing educational policy in ways that are participatory, efficient, effective and co-ordinated between levels.

The Educational Action Plan encompasses many of the proposals in this review in the area of education. Among the points that this report emphasises, the Educational Action Plan rightly attaches importance to teachers’ training and professional career paths, which are vital to improving management and the quality of educational outcomes.

There are three areas the Educational Action Plan embraces but which deserve greater detail. They are the development and use of assessment capacity, strengthening ties between performance and reward in teachers’ careers, and strengthening links beyond the education system with other skills-training institutions (especially the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security within the National Education and Labour Council and through the National Vocational Education and Training System [SINAFOCAL] and the National Service for Professional Promotion [SNPP]) as well as the production sector, in the context of the overhaul of technical education.

A pact for education

The ongoing efforts to develop a National Plan for Educational Transformation for 2030 reflect both the size of the challenge and the determination to transform the education system into a driver of inclusion. Five key elements should be included in this renewed drive for reform:

Coverage and completion. It is necessary to continue the measures designed to expand education coverage and promote school completion, supporting access to school in remote areas and among disadvantaged people, and implementing policies to favour school retention and completion, avoiding grade repetition and dropouts.

Quality of education. The quality of educational outcomes is vitally important for transforming recent efforts in terms of educational inputs into skills for tomorrow’s citizens.

Teacher training and quality. Policies to improve learning outcomes must focus on teachers, reshaping their training and career pathways, as well as educational resources and school management. Such policy-making will require better empirical data on learning outcomes.

Relevance of skills to the labour market. Reforming the secondary education curriculum to favour integration into the labour market and provide a basis for access to higher education will make education more relevant. An integrated technical and vocational education and training (TVET) system will favour quality school-to-work transitions, in which participation by stakeholders – including educators, the private sector and unions – will be critical.

Adjusting the educational offer to the demand of the labour market. Policies to improve the match between the demand and supply should strengthen information, training, intermediation and skills-anticipation mechanisms.

Paraguay needs to adopt a national pact on education built on a consensus reached in a consultative process. The Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Education and Science, and the Technical Secretariat for Planning (STP) are currently engaged in a joint effort to design an ambitious National Plan for Educational Transformation (PNTE) with a time horizon of 2030. To start realising its ambitious goals, the Paraguayan education system needs to define targets and milestones for the different areas of action, and must clearly establish the necessary financial commitments and look to other countries’ experiences to learn best practices.

Expanding coverage and promoting school completion, particularly in pre-primary and secondary education and among the most vulnerable groups

Generating better statistical data about education

One priority for evaluating future challenges, monitoring progress and informing education policy is the generation of more and better statistical data about education. Until now, the data on enrolment rates (and, by extension, the number of non-enrolled boys and girls) have been considered unreliable. The Central Register of Students (Registro Único del Estudiante) can be used to centralise student information and favour the production of more reliable, easy-to-manage and comparable data. It will also be necessary to overcome the current challenges for developing education metrics regarding access, enrolment, progression and school completion (OECD, 2018[1]).

Expanding access to early childhood education

It is necessary to raise community awareness of the importance of early childhood education. Paraguay could strengthen the Councils on Childhood and Adolescence as a public awareness strategy and could establish them in places where none exist. Indeed, having received pre-primary education raises PISA scores by the equivalent of one additional year of secondary schooling, according to the results of Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries participating in PISA 2012 (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2014[3]).

Access to pre-primary education could be improved by helping families overcome the main economic and geographical barriers. To address economic barriers, the government could make the Tekoporã conditional cash transfers more strongly conditional on preschool attendance. That way, beneficiaries would receive those transfers only if they ensure minors’ school attendance. Regarding geographical barriers, it would be useful to scale up the non-formal initial education programme Maestras Mochileras (Backpacking teachers). In addition, the pre-primary educational offer should be expanded through more and better schools and teachers, and by developing modalities to meet special needs.

Supporting access in remote areas and for disadvantaged groups

Paraguay has a range of strategies to improve access to secondary education. Major inequalities persist in access to the education system, particularly at the secondary level. These gaps are mainly related to factors such as gender, socio-economic status, and geographical location (OECD, 2018[1]). Paraguay could improve coverage of secondary education through strategies such as (i) scholarships for students from disadvantaged groups or with special needs, (ii) introducing mechanisms to offer open secondary schools and distance-learning secondary schools, and (iii) school transport for secondary education in remote areas.

Encouraging students to stay in school and complete education cycles

It is necessary to promote policies to encourage students to stay in school and complete their studies, avoiding grade repetitions and dropouts. In Paraguay, 22.9% of students repeated at least one grade in primary or secondary school. Repeating grades is more common among male students (26.5%) than among female students (19.3%). Socio-economic and cultural factors play a role: while 28.3% of disadvantaged students repeated at least one grade in primary or secondary school, the figure drops to 10.9% among other students. Among students with a native language other than Spanish, the figure rises to 30.3% (PISA-D). The government should implement a gradual expansion of the school day, starting with a pilot to measure its impact on dropout reduction (and learning outcomes).

Mechanisms should also be developed to identify and support students at risk of exclusion, with flexibility in pedagogical methods to support those with greater difficulties. Paraguay has an adequate number of teachers, so specific resources could be dedicated to supporting struggling students so they will not have to repeat grades, as the educational outcomes from repeated grades are inconclusive.

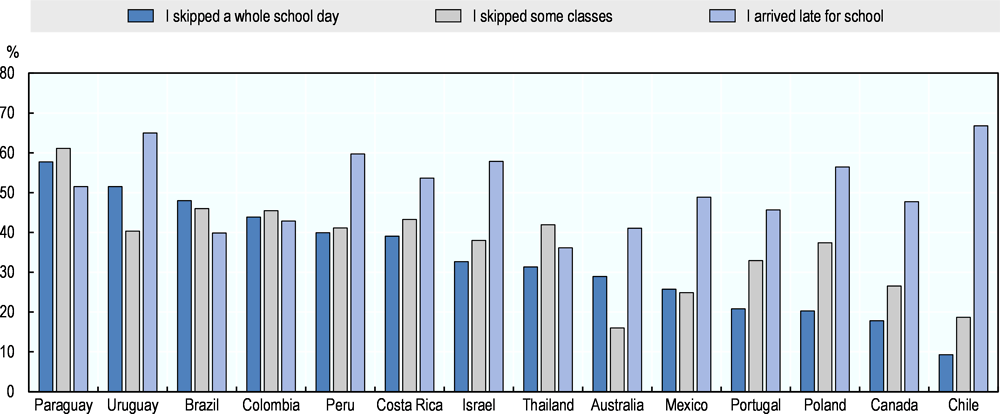

Schools should put mechanisms in place to reduce the high rates of absenteeism and tardiness. In Paraguay, more than half of 15-year-old students reported being late to class one or more times in the previous two weeks; 61% of them said they had missed at least one class on days when they were in school; and 58% of the students acknowledged having missed an entire day of school in the previous two weeks (see Figure 4.2).

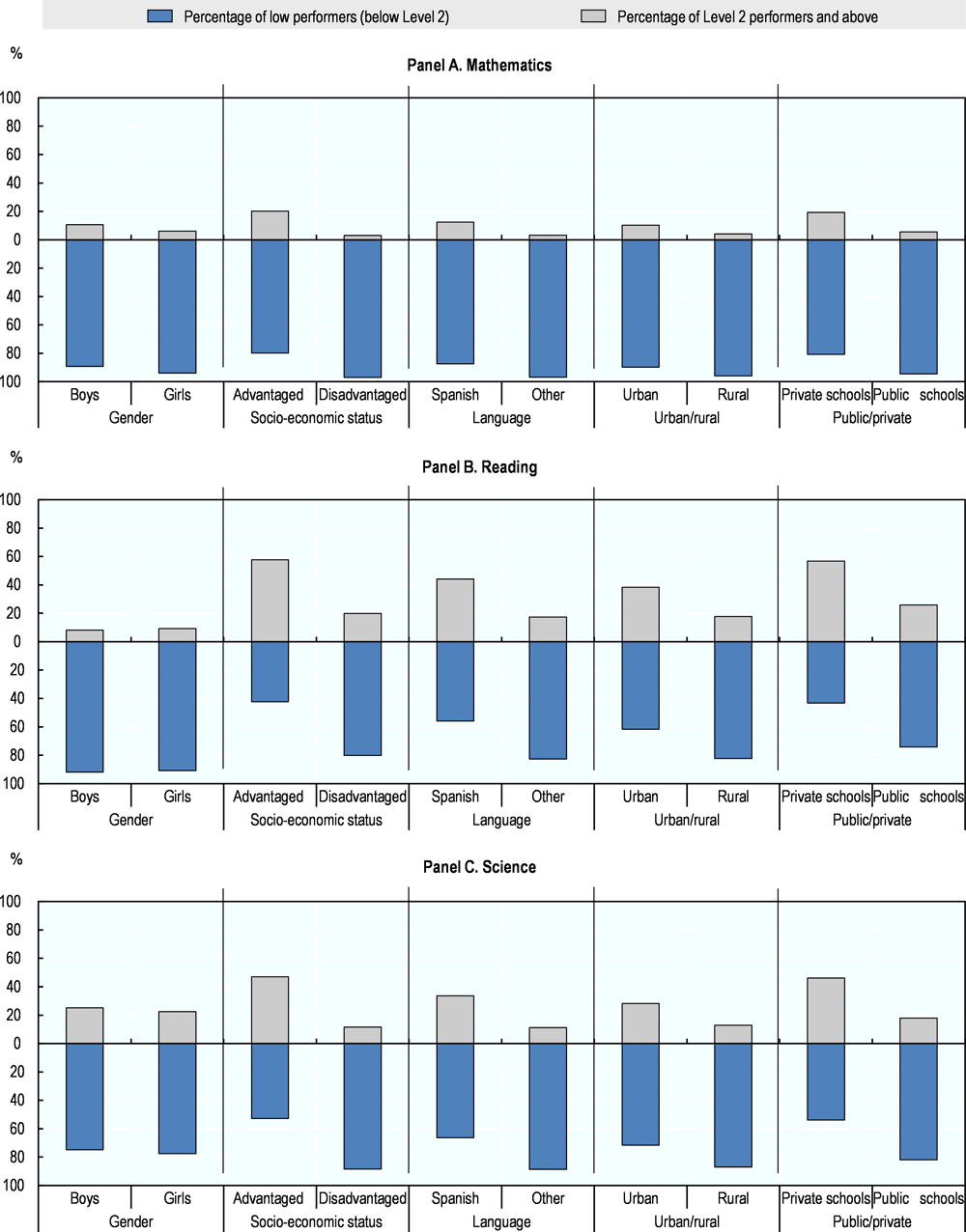

Besides ensuring access, it is necessary to improve the quality of education in remote areas and among the most disadvantaged socio-economic groups. In Paraguay, students’ performance varies mainly based on their geographical location, their socio-economic condition and their language, while there are no substantial differences between male and female students (see Figure 4.3). While 80.2% of socio-economically disadvantaged students do not achieve basic reading proficiency, this figure drops to 42.3% among other students (see Figure 4.3 Panel B).

Figure 4.2. School absenteeism and tardiness

Improving learning and the overall quality of the education system

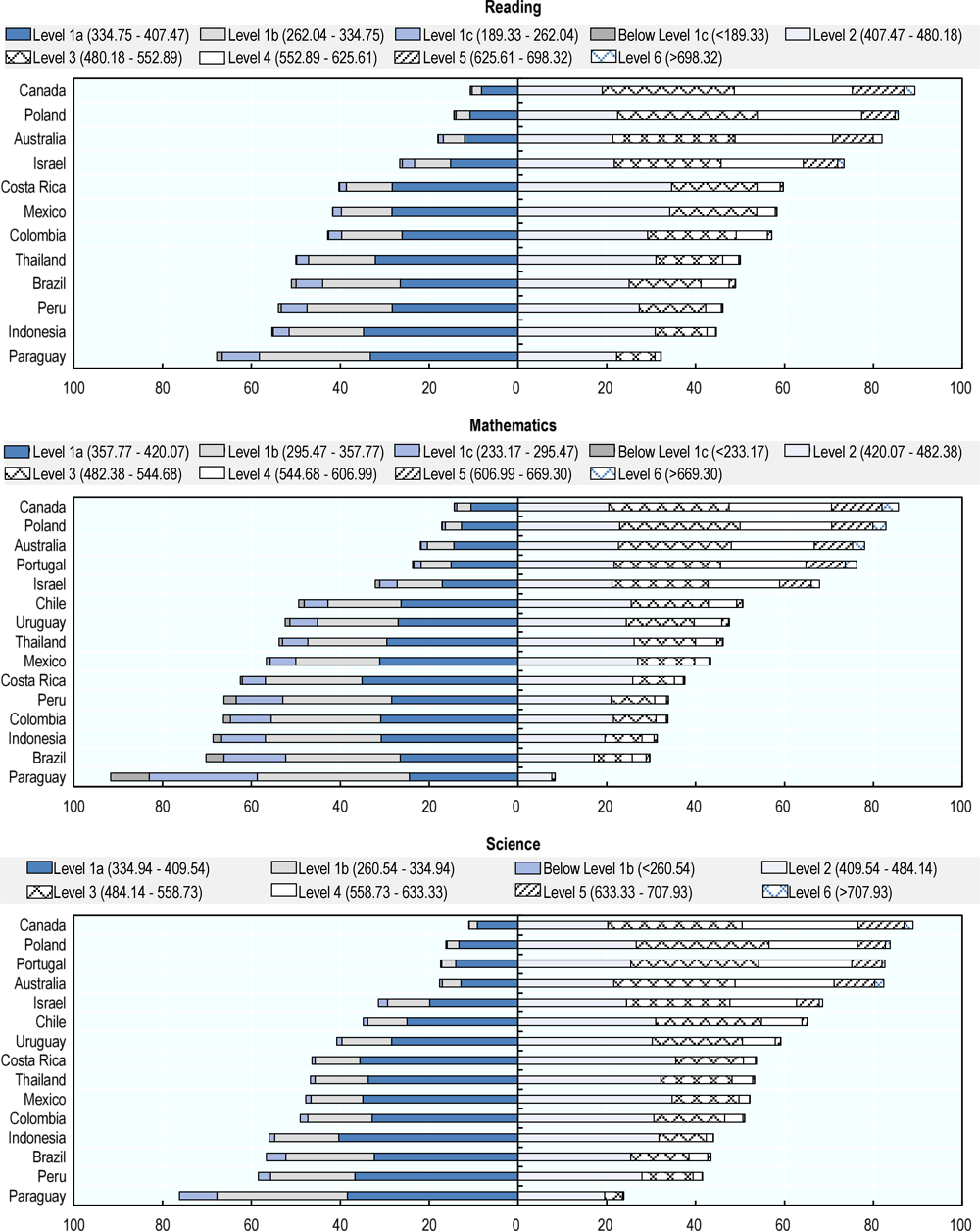

Besides confronting the coverage challenge, an effort is needed to improve the quality of learning. At present, most students in Paraguay do not attain basic proficiency levels in mathematics, reading and science (see Figure 4.4). The PISA for Development results place Paraguay towards the bottom of the comparison group, but they can also help identify priorities for strengthening quality.

It is necessary to improve empirical evidence on learning outcomes to inform policy-making. There is highly valuable data from the educational census tests administered by the National Educational Process Evaluation System (SNEPE). It is necessary to strengthen SNEPE as the main tool for evaluating student performance. The use of SNEPE should be improved and its results should be made public to favour analysis and evidence-based policy-making. Continuing to use PISA will also make it possible to track changes and to leverage international comparisons, identifying approaches that could inspire reforms.

Figure 4.3. Performance varies mainly by geographical location, socio-economic condition and language, while there are no substantial gender disparities

Figure 4.4. Most students in Paraguay do not attain basic proficiency levels

Note: Level 2 (basic proficiency) reflects students who have the minimum skills to participate effectively and productively in their life as students, workers and citizens.

Source: PISA database 2015 and PISA for Development database (OECD, 2018[4]).

Improving educational outcomes requires improving the quality of teaching. The first step is to reshape teachers’ career pathways. It is necessary to attract talent and raise the status of teaching to ensure that the best candidates enter and remain in the profession. This entails rethinking mechanisms for selection, but also incentives (salaries, social recognition, etc.). Additionally, incentives for development and improvement should be strengthened, with a stronger link between performance and reward, using the performance measurement mechanisms that are being put in place. Lastly, it is necessary to strengthen and systematise teachers’ evaluations, to monitor progress, identify limitations and overcome them.

The other priority is to raise the quality of the Teacher Training Institutions (IFDs) to improve the quality of teaching. A process should begin for accrediting IFDs and strengthening the National Agency for the Evaluation and Accreditation of Higher Education (ANEAES), to guarantee its ability to perform these tasks effectively. This improved teacher training should apply to both initial training and continuing professional education.

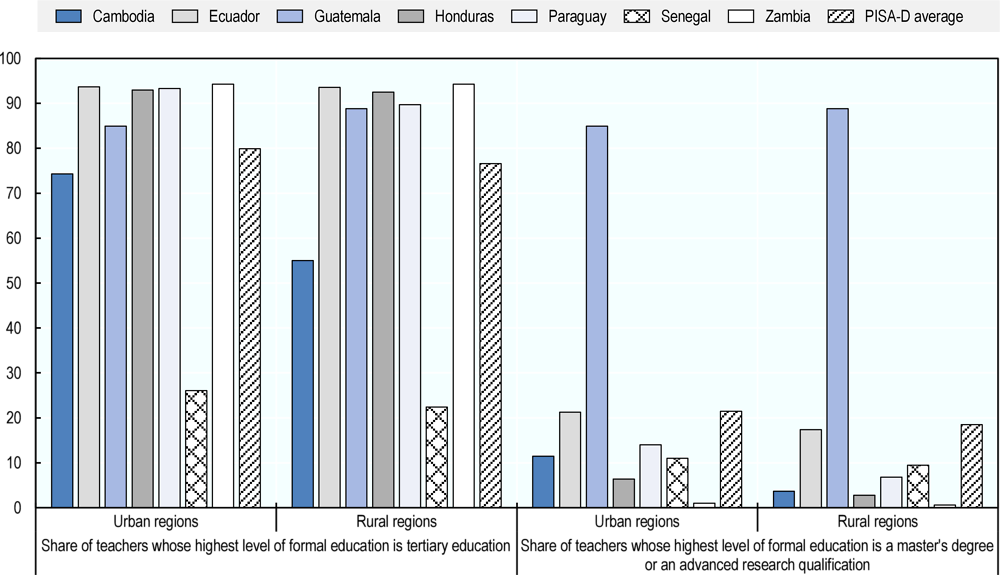

Figure 4.5. Teachers’ educational level according to PISA for Development

Improving employability and access to better-quality jobs

Besides keeping young people in school longer, it is imperative to prepare them to be the workers and citizens of tomorrow. Integration into the labour market is a key indicator for the relevance of learned skills, albeit it is not the only one. In Paraguay, given the relatively high dropout rates, vocational training is a task for both the formal school system and for the initial and continuing vocational training systems, each of which can bolster the skills of different population segments.

People transition from school to the labour market relatively early in Paraguay. Despite recent improvements, school dropout rates remain high, especially once students begin secondary school at age 15. Most people aged 15 to 18 who do not attend school justify dropping out by citing a need to work and a lack of resources at home (OECD, 2018[1]).

Young Paraguayans have difficulties transitioning from school to the labour market. The unemployment rate among young people aged 15 to 24 was 14.6% in 2018, 3.7 times the rate among people over 25 (3.9% according to the ILO (2019[5])), an unemployment differential comparable to that of other Latin American countries but higher than the worldwide differential, in which youth unemployment is three times that of the adult population (ILO, 2018[6]). These transitions are especially hard for women, 40% of whom have no work after leaving school and more than 35% of whom are unemployed (OECD, 2018[1]).

The dropout rate contrasts with the downward trend in returns to secondary education. The decrease in returns to secondary education is common throughout Latin America and is explained first by demand factors (i.e. change in the demand for qualified workers) and second by supply factors (i.e. the increased percentage of the population getting secondary education). However, at the individual level, it involves a lower return rate among young people, whose opportunity cost for continuing their education is high. Therefore, actions to keep young people in the education and training system should be supplemented by actions to make the training offer more attractive, with emphasis on promoting young people’s employability.

Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) has grown considerably in Paraguay. From 2004 to 2012, enrolment in vocational upper secondary programmes (the technical baccalaureate) grew by nearly 40% (MEC, 2014[7]). Around 25% of high school students are enrolled in technical secondary education; this represents a lower percentage than the OECD average (44%, (OECD, 2018[8])) but the increase is notable.

The fragmentation of TVET in Paraguay is an obstacle to improving its outcomes and generating institutionalised progress. There are a multitude of public and private professional-training providers. The main players are the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MTESS). The Ministry of Education offers formal TVET in secondary schools, but also a set of non-formal programmes that include vocational training options. The MTESS, in turn, offers courses through the National Professional Promotion Service (SNPP) and manages the private supply of training through SINAFOCAL. However, it also offers advanced technical training. Other ministries also offer training programmes, especially the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Farming.

Because of institutional fragmentation, there is room to improve the use of vocational training resources. It is not easy to identify the resources dedicated to TVET in this country since the MEC budget does not have a separate line item for technical training. Paraguay devotes 0.12% of GDP to vocational training through SINAFOCAL and the SNPP, close to the average for OECD countries (0.14% in 2016). Thanks to a payroll-based employer contribution to finance training, there are resources for this type of skills training. However, vocational training has not benefitted from the increased resources for education implemented through the National Fund for Development and Public Investment (FONACIDE).

Modernising curricula based on a national qualifications framework

A national qualifications system is a key tool for creating a clearer, more relevant vocational training system. Such a system makes it possible to identify the skills needed based on homogeneous qualification levels and families of professions. From there, skill-based training modules can be designed. Moreover, it also makes it possible to develop mechanisms to recognise abilities acquired in different educational formats or through job experience, thus keeping vocational training from being a dead-end or from being perceived as one. Lastly, in a fragmented system such as Paraguay’s, it helps clarify the supply of training options as a whole.

Paraguay has taken major steps towards developing a national qualifications system. It has created a list of 23 occupation groups, and descriptors of the five qualification levels in the framework (Ojeda Cano, Álvarez and Jiménez Yegros, 2018[9]). From there, work has begun to complete the catalogue of occupational profiles and develop curricula (in three prioritised occupation groups). These advances took place thanks to the creation of inter-ministerial teams from the MEC and MTESS, and with support from international co-operation projects, especially the European Union’s EUROsociAL programme.

Completion and institutionalisation of the national qualifications system should be prioritised within the country’s educational initiatives. To date, progress has been slow. As a result, a number of curricular modules have been developed but not implemented, which puts them at risk of becoming obsolete. The delays in designing and formalising the qualifications system are partly due to the institutional weakness of the vocational education and training system as a whole. However, the qualifications system itself could make it possible to solve some problems arising from institutional fragmentation. Completion of the occupational profiles catalogue is part of the 2018-23 Educational Action Plan. An inter-institutional effort should be made, perhaps supported by a coalition of donors and international technical counterparts to give the decisive push.

It is necessary to reform curricula to prioritise 21st-century skills. This should be a priority, especially, for the technical and vocational segments – for technical secondary education within the formal education system and in non-university post-secondary education, as well as vocational education. Such training should instil up-to-date technical skills but also find the right balance between specific skills and transversal and basic skills. Many of the skills employers say they cannot find are soft and behavioural skills. Developing dual training programmes can help develop this balance. In dual training programmes, students spend a large share of their time in workplace-based learning. Workplace-based learning eases school-to-work transitions and can allow for greater efficiency in the use of resources for TVET (OECD, 2014[10]).

The curriculum for technical baccalaureates should be tailored to industries’ changing demands by involving the private sector and other stakeholders. In practice, the production sector should be more directly involved in curriculum planning and in the work carried out to formulate the national qualifications framework.

Strengthening the technical and vocational education and training system

The government should establish a governance body for technical and vocational education and training. The National Education and Labour Council (CNET), created by the new charter of the Ministry of Education should be convened, and its members appointed by executive branch decree. This would provide strategic support to the joint work that the MEC and MTESS have been doing for several years, particularly on the national qualifications system. By including social partners (trade unions and employers’ organisations), the CNET framework would also give more impetus and relevance to this ongoing work.

A more solid legal base would strengthen the contribution of the CNET’s creation to the task of integrating the MEC’s and MTESS’s technical and vocational training functions. In the current circumstances, there may be overlaps between CNET and SINAFOCAL in terms of the strategic direction of the technical and vocational training system. Nonetheless, the mission of SINAFOCAL, as defined in Law 1652 of 2000, is much narrower, as its target population does not include students receiving initial training. Therefore, instituting the CNET in a law on technical and vocational education and training could clarify the distribution of powers among TVET bodies in Paraguay and give CNET enough autonomy.

CNET should have sufficient human resources for its mission. It should include a specific secretariat with duly compensated full-time specialised professionals. So far, the need to make human resources from the MEC and MTESS available to an inter-ministerial technical unit has enabled progress in the qualifications framework. That approach, however, does not seem sustainable as there is no mechanism to ensure that it has enough resources and capacity to carry out its function.

The need to structure TVET actions among multiple ministries is a challenge faced by many countries, including many OECD countries. A key element of such co-ordination is to consider all training activities part of a single skills-training system in which each agency has a well-defined role. This means eliminating duplication: in many countries, such as Singapore, vocational training and university-based academic training are in the hands of different authorities. This co-ordination also involves making the assessment system uniform to ensure that two people who are qualified for the same profile have comparable skills (even if acquired in a different way) (OECD, 2011[11]).

Box 4.1. Building an effective system for technical and vocational education and training

Countries currently follow different governance models for TVET policy. While some countries’ governments put TVET in the hands of the Ministry of Education (e.g. Russia and Turkey), other countries entrust its oversight to the Ministry of Labour (e.g. Malawi and Tunisia). Countries such as India and Burkina Faso have a ministry devoted exclusively to TVET policy, while others have a TVET-focused government agency in charge, such as Jamaica and the Philippines. By contrast, France and Bangladesh have a co-ordinating council on a higher level than the relevant organisations, while in Korea and Canada, TVET policy is divided between the relevant ministries (UNESCO/ILO, 2018[12]).

Each governance model is valid and reflects the structure of the national government of each country; it would be complicated to judge a model as being more or less successful. There are, however, a series of actions that any country could take to improve inter-ministerial co-ordination for better TVET and employment outcomes (UNESCO/ILO, 2018[12]). All countries should regularly verify that their TVET policy governance system meets these nine criteria:

1. Responsibility must be backed by authority, so that the organisation in charge can enforce measures instead of relying on the goodwill of the other parties involved.

2. There should be clarity about the system’s function and purpose, with all stakeholders sharing a single vision and understanding the other stakeholders’ contribution to achieving it.

3. The nature and thrust of the co-ordination mechanisms must be effective and be recognised by all parties involved.

4. Cultural influences should also be kept in mind so that governance systems adapt to them rather than entering into conflict with them.

5. Responsibility should be based on influence over funding, allowing the ministry or agency in charge of TVET to influence the actions of other ministries. TVET funding should be used to support policy priorities, so it is channelled into areas of greatest need, whether geographical or sectoral or to correct social inequality.

6. TVET should be part of an integrated human-resource development system with separate but clear pathways for learners to follow, supporting achievement of economic and social development targets.

7. Operational efficiency should not be based on additional ad hoc co-ordination measures. This means that co-ordination in the TVET system should be robust enough to withstand sudden crises and a growth or change in demand.

8. Employers’ role has a positive impact on co-ordination and governance, which bolsters the programmes’ quality and relevance, improves graduates’ outcomes in terms of vocational readiness and employment, and reduces skills shortages and hard-to-fill vacancies.

9. There is evidence that training providers function well at the local level, with solid lines of communication and co-ordination with the national government and employers.

Source: UNESCO/ILO (2018[12]), Taking a whole of government approach to skills development, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and International Labour Organization, www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_647362.pdf.

Paraguay needs to ensure the quality of vocational training and education. To achieve this, it must strengthen the accreditation process for Higher Technical and Vocational Institutes and for work training and education institutes. In vocational training, the recent implementation of the National Register of Vocational Education and Training Institutions (REIFOCAL) supplies an important tool. It should be strengthened so that it can register a larger proportion of technical and vocational training suppliers. Note, too, that the requirements SINAFOCAL imposes on private service providers should also be applicable to the SNPP.

A better-integrated TVET system should facilitate a diversity of training paths that ease students’ transition to employment and strengthen the link to the labour market for continuing education. This requires inter-institutional agreements for recognition of certified qualifications, allowing passageways between systems, including between the TVET system and secondary and university academic education. This way, students who enter the workforce early to meet their families’ needs can later complete their education, if necessary, in formal educational institutions.

Improving the match between supply and demand for skills

Facilitating transitions into the workforce requires strengthening active labour market policies to support the process of connecting with the labour market, supporting more effective guidance mechanisms that give more information to students and workers, bolstering links with the production sector, improving data creation and analysis about the labour market, and improving the anticipation of needs.

Active labour market policies and the Public Employment Service (SPE) can facilitate a better transition from school to work. To achieve this, the SPE must be more relevant, with a greater local presence and more personalised service, including guidance.

The state can contribute to a better match between training and the labour market by analysing the dynamics of the labour market. An analysis of the skills that the market demands and of the competences of the people left out of the job market (an employability map) may help better define skills-training policy.

It is also necessary to improve the information and guidance mechanisms for students. Providing students with information on educational and professional career paths may help them to make informed decisions about their field of study and future career. Including information about labour-market outcomes may help reduce prejudices about technical and vocational training. One approach is to develop a survey of graduates (of both the formal and non-formal system) to gather data about their job situation. Spain is expanding its survey of university graduates to TVET graduates with this aim. The possibility of lifelong learning and late initial training, which recognises previously acquired knowledge, can help incentivise training options with faster transitions into the labour market.

The MTESS’s Labour Market and Occupational Observatories (the latter housed in SINAFOCAL) should be strengthened to anticipate the demand for skills in a more comprehensive way. The Occupational Observatory has begun this anticipatory work using qualitative methods (interviews) and unrepresentative surveys. The labour observatory is also analysing the labour market based on national surveys (the Ongoing Survey of Households [EPH]). A recent OECD analysis (OECD, 2016[13]) underscores the variety of exercises that exist. Systems for anticipating needs vary considerably between countries, but it is considered good practice to use a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative approaches may include skills-demand projections (based on macroeconomic projection models with a relatively long time horizon, from five to ten years). Qualitative approaches, in addition to ad hoc surveys, may include structured strategic foresight methods to keep the results from focusing on marginal mismatches (OECD, 2016[13]). It is also necessary to monitor vocational training graduates, to analyse the improvement in their skills, income or productivity, so as to improve public policies accordingly.

Participation by workers and the production sector, as well as a direct relationship between the data generated and public policy, are two key ingredients to successful needs-anticipation exercises (OECD, 2016[13]). Currently, the SNPP has sector-specific working groups but needs to improve data collection methods and the incentives to the private sector. The main benefits to the production sectors generally come from the results’ influence on policies regarding both initial and continuing training. Some countries have skills councils that help draft training policies. In some cases, such as the United Kingdom, these councils may also play an instrumental role in setting up apprenticeship systems, designing and sizing the offer based on circumstances in the industry, and helping to match businesses with apprentices (OECD, 2016[13]). This mechanism offers companies a potential very direct benefit, aside from the benefit associated with their indirect participation.

The needs-anticipation exercises should also include other parts of the administration. The Ministry of Industry and Commerce, for instance, has the ability to collect information on the labour market’s needs more specifically than the labour observatory, which bases its analyses on the EPH. It can also collect information regarding the skills needs of prospective international investors. Other government agencies should have an increased participation in these exercises, either as contributors or to help guarantee the nationwide comparability of the information produced. These might include other sector-specific ministries (especially the MAG) as well as the statistical authority (the DGEEC) and the Central Bank of Paraguay (for formulating macroeconomic projections).

References

[5] ILO (2019), ILOSTAT, International Labour Organization, Geneva, http://www.ilo.org/ilostat.

[6] ILO (2018), World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2018, International Labour Organization, Geneva, http://www.ilo.org/publns (accessed on 8 May 2019).

[2] MEC (2019), Plan de acción educativa 2018-2023 [Education Action Plan 2018-2023], Ministerio de Educación y Ciencias de Paraguay, Asuncion.

[7] MEC (2014), Informe Nacional Paraguay: Educación para Todos 2000-2015 [National Report of Paraguay: Education for All 2000-2015], Ministerio de Educación y Ciencias de Paraguay, Asuncion, http://www.acaoeducativa.org.br/desenvolvimento/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Informe_Paraguai.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2019).

[8] OECD (2018), Education at a Glance 2018: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2018-en.

[1] OECD (2018), Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay: Volume 2. In-depth Analysis and Recommendations, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264306202-en.

[4] OECD (2018), PISA for Development Reporting Tables and System-level Data (databse), OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisa-for-development/database/PISA_D_school_based_assessment_Report_Tables_FINAL.xlsx.

[13] OECD (2016), Getting Skills Right: Assessing and Anticipating Changing Skill Needs, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252073-en.

[10] OECD (2014), Skills beyond School: Synthesis Report, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264214682-en.

[11] OECD (2011), OECD reviews of vocational education and training Learning for Jobs. Pointers for policy development, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/edu/learningforjobs (accessed on 2 June 2019).

[3] OECD/CAF/ECLAC (2014), Latin American Economic Outlook 2015: Education, Skills and Innovation for Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/leo-2015-en.

[9] Ojeda Cano, M., S. Álvarez and M. Jiménez Yegros (2018), Hacia un Sistema Nacional de Cualificaciones Profesionales en el Paraguay. La construcción del catálogo nacional de perfiles profesionales, La Revista Paraguaya de Educación, Asuncion, https://www.mec.gov.py/cms_v2/adjuntos/15276?1550061015.

[12] UNESCO/ILO (2018), Taking a whole of government approach to skills development, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and International Labour Organization, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_647362.pdf.