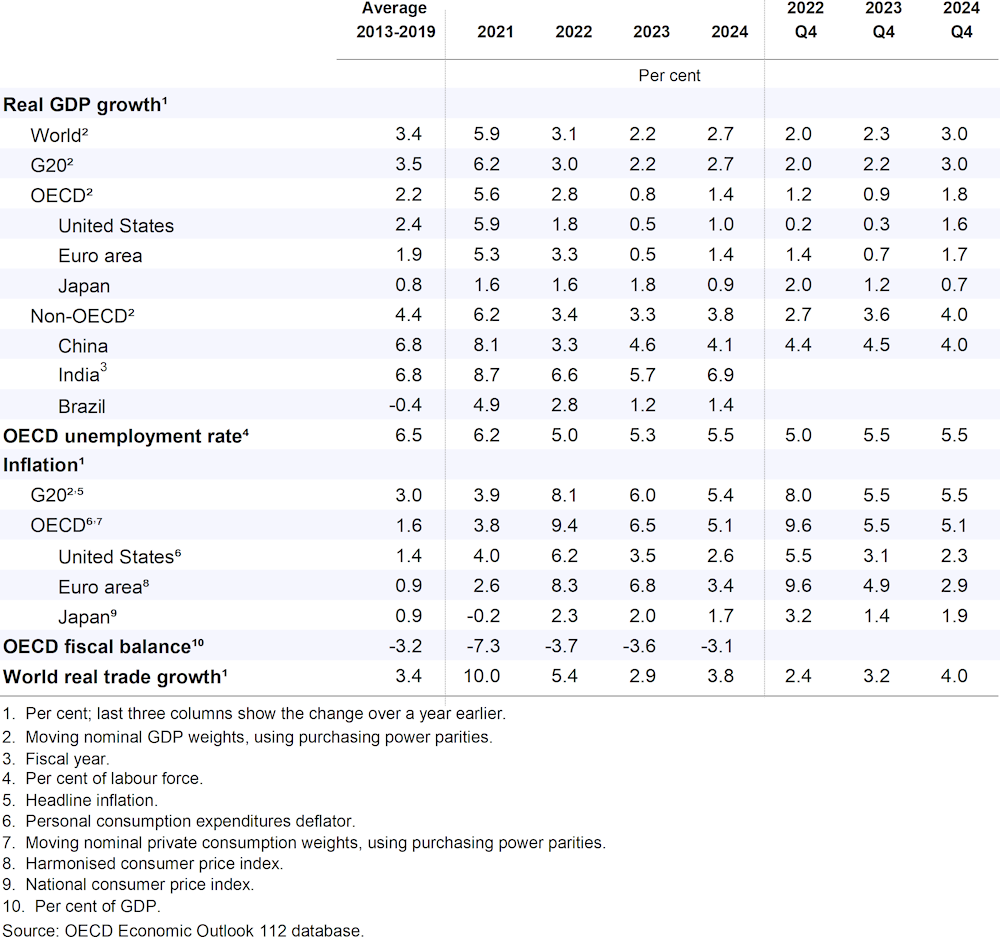

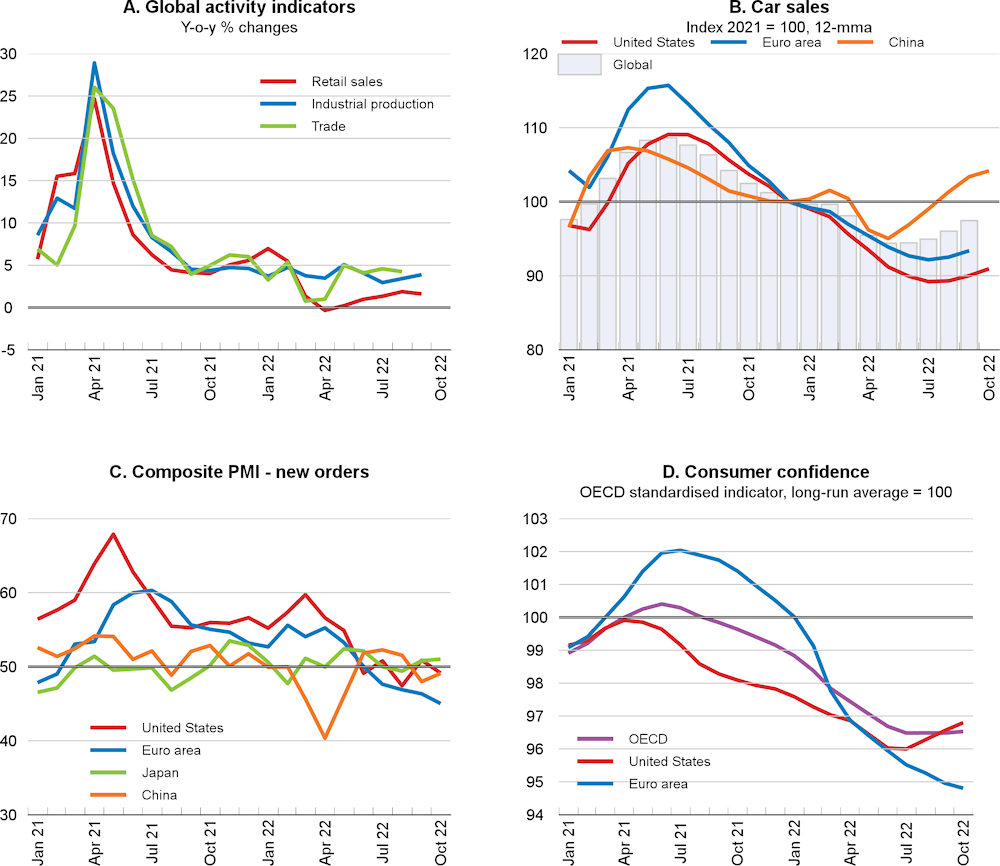

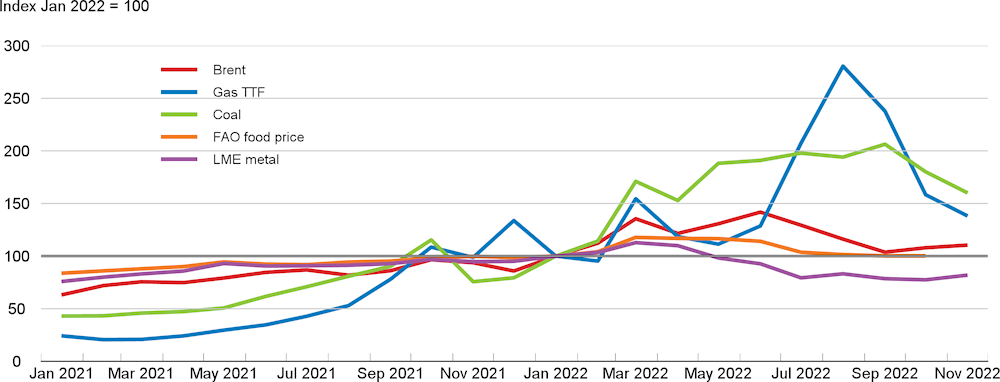

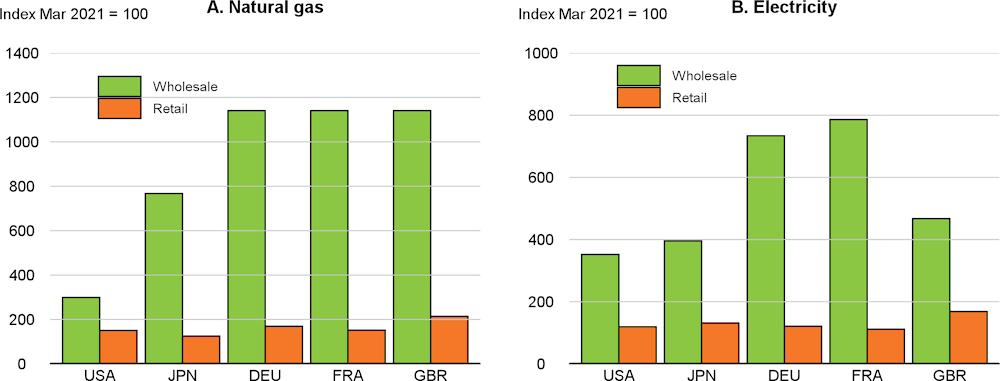

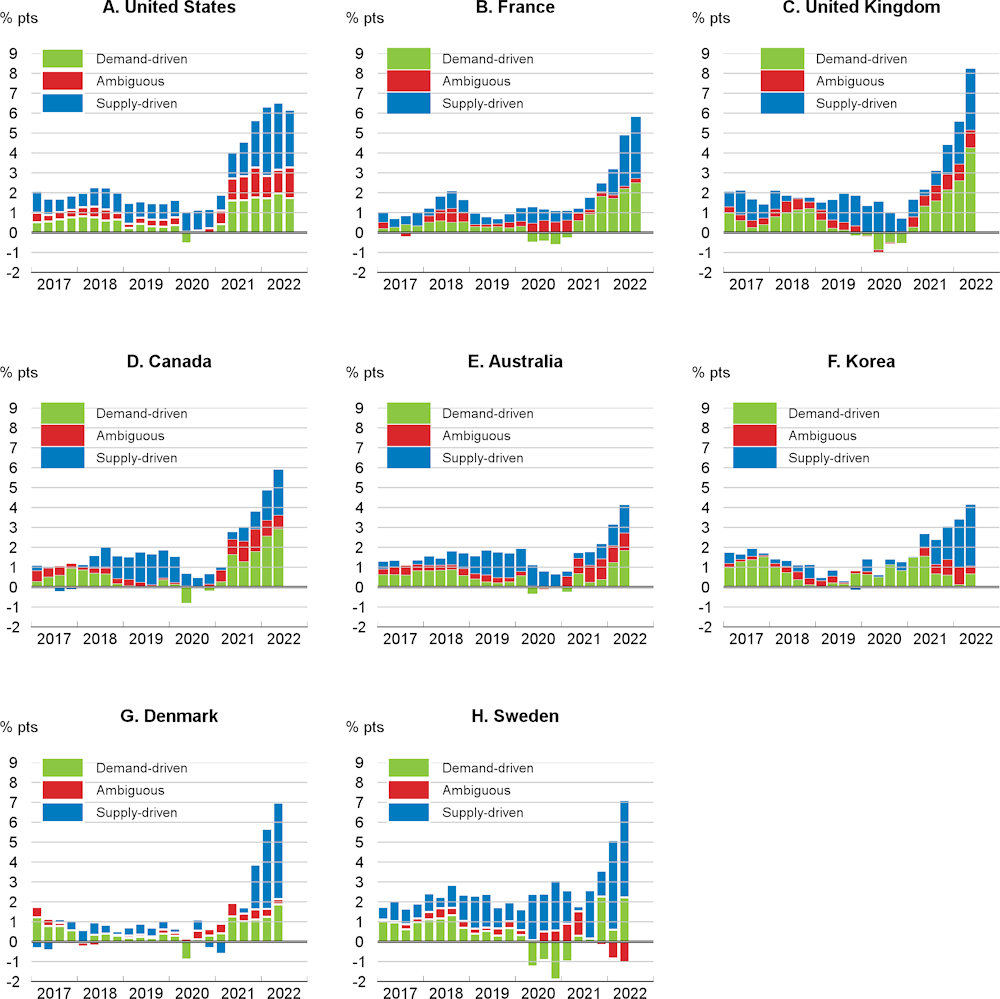

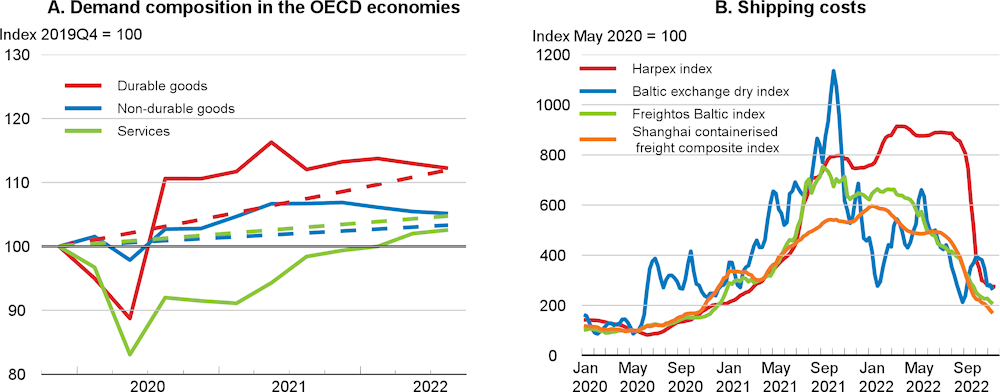

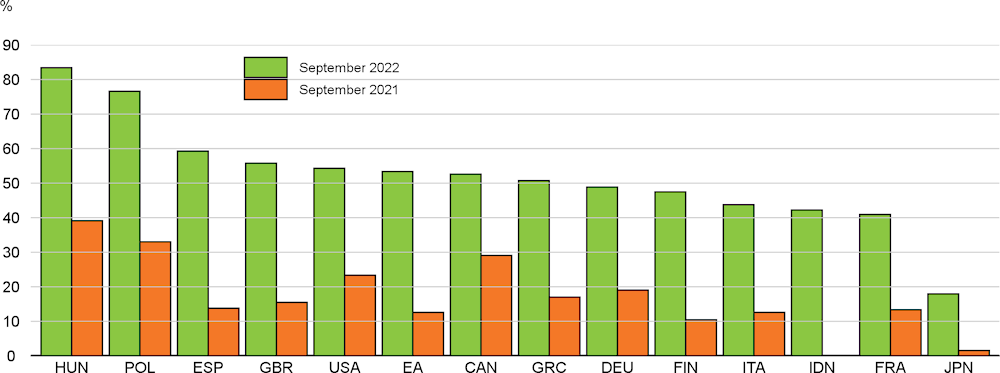

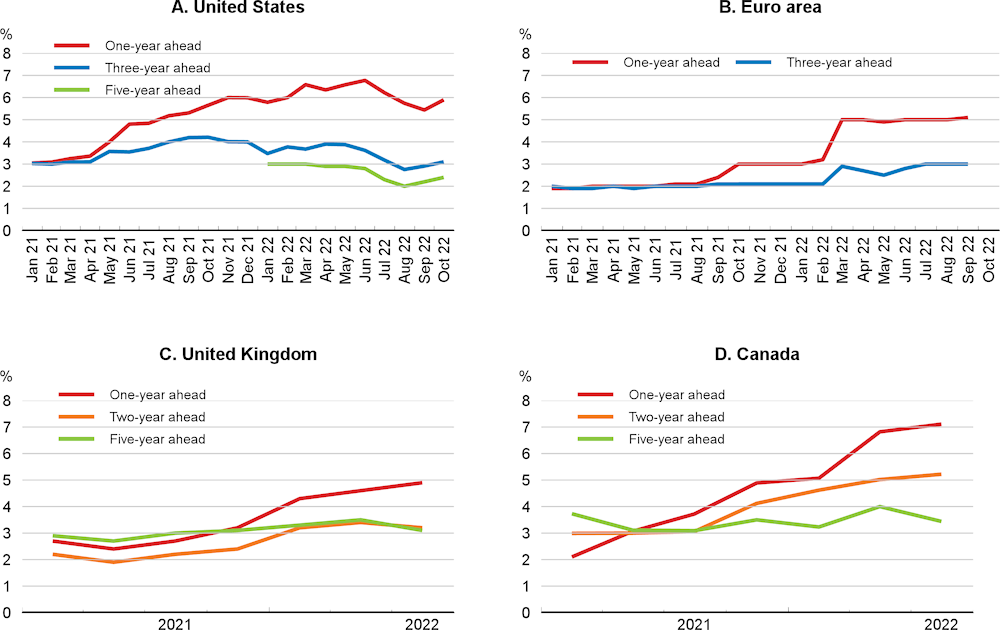

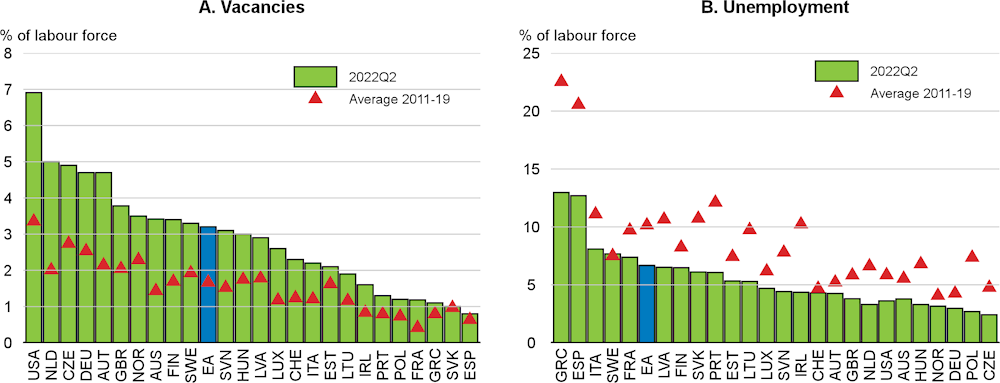

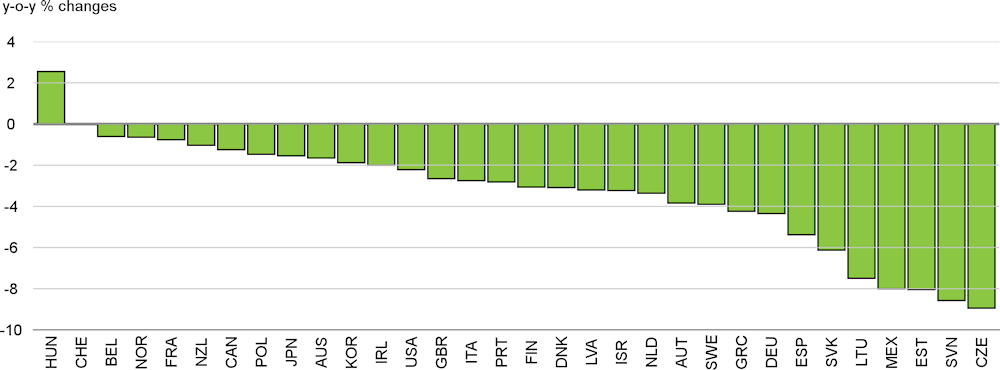

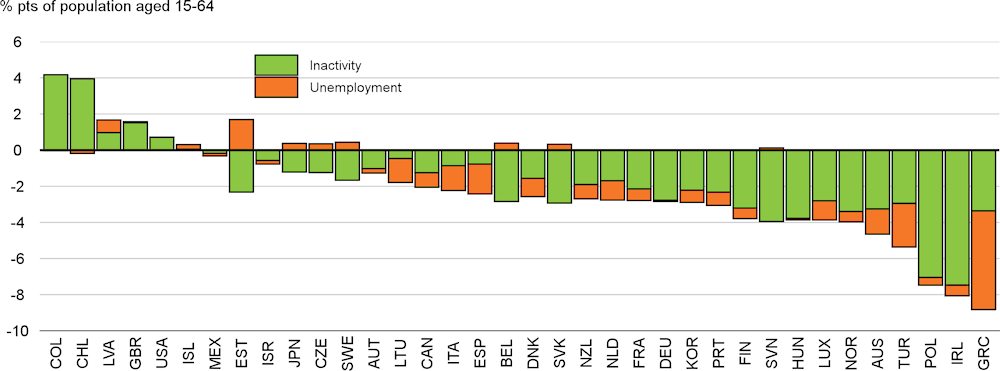

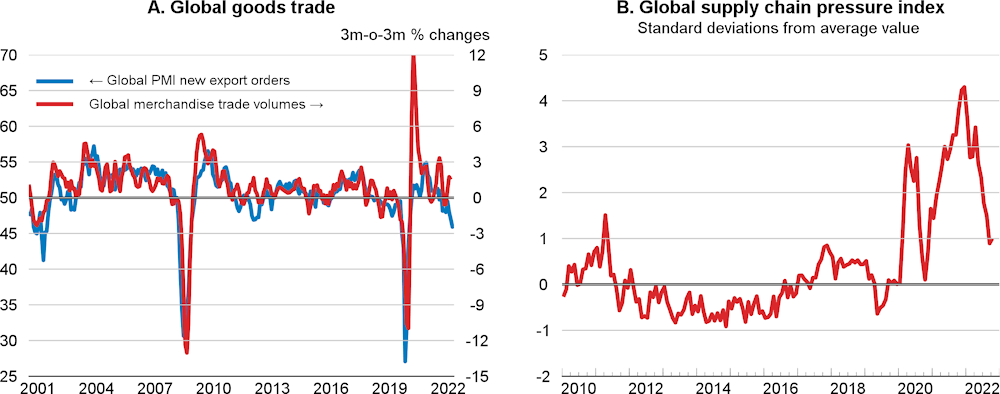

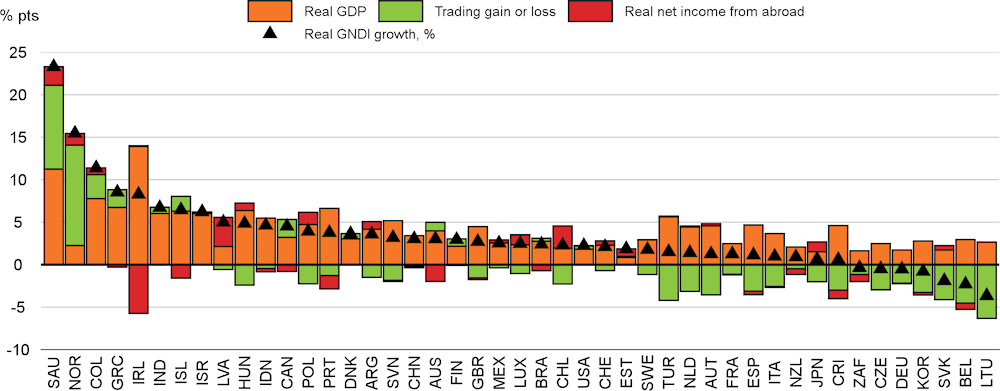

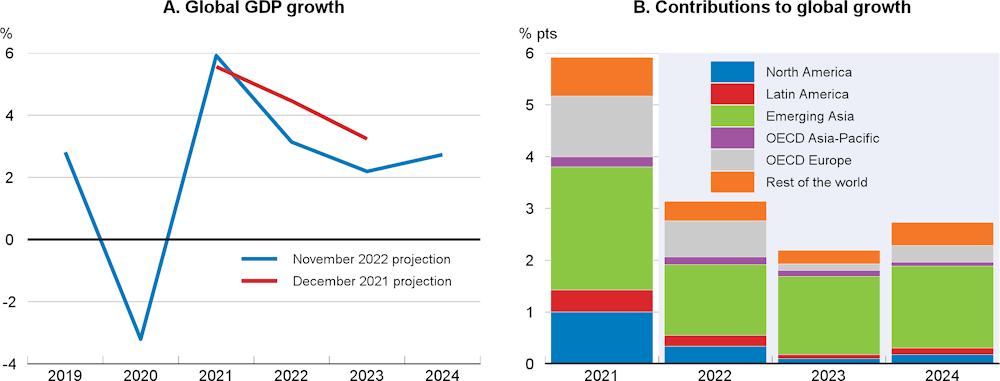

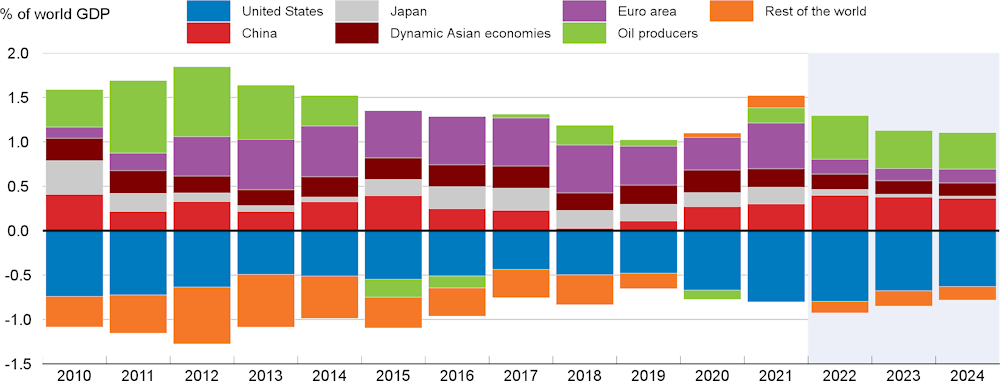

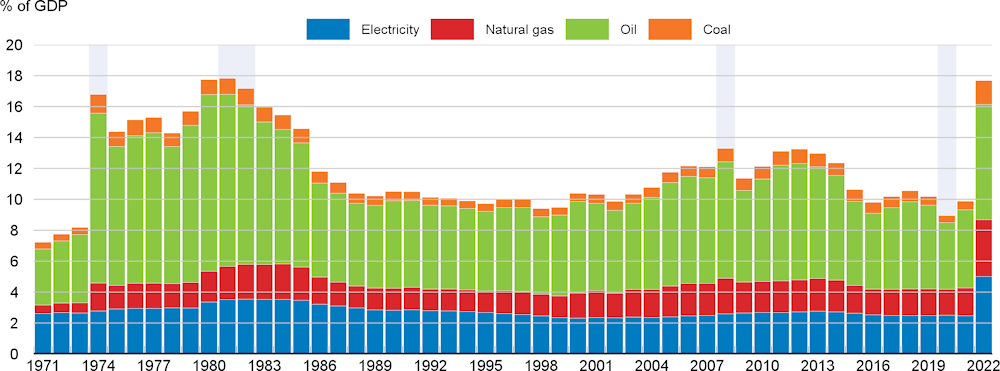

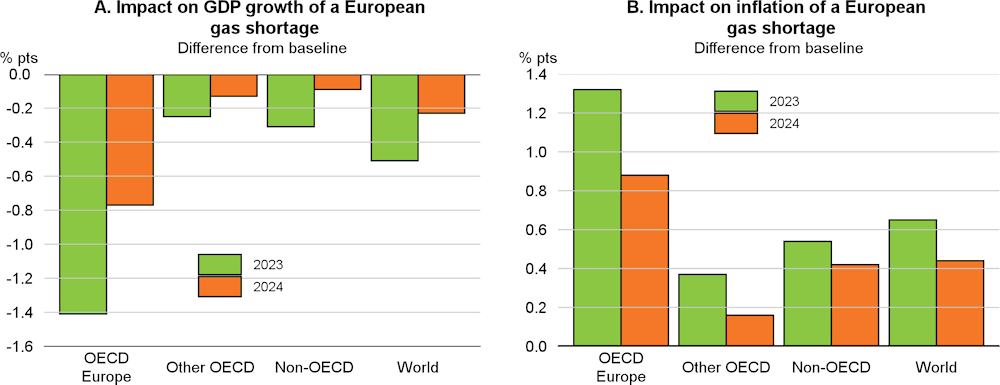

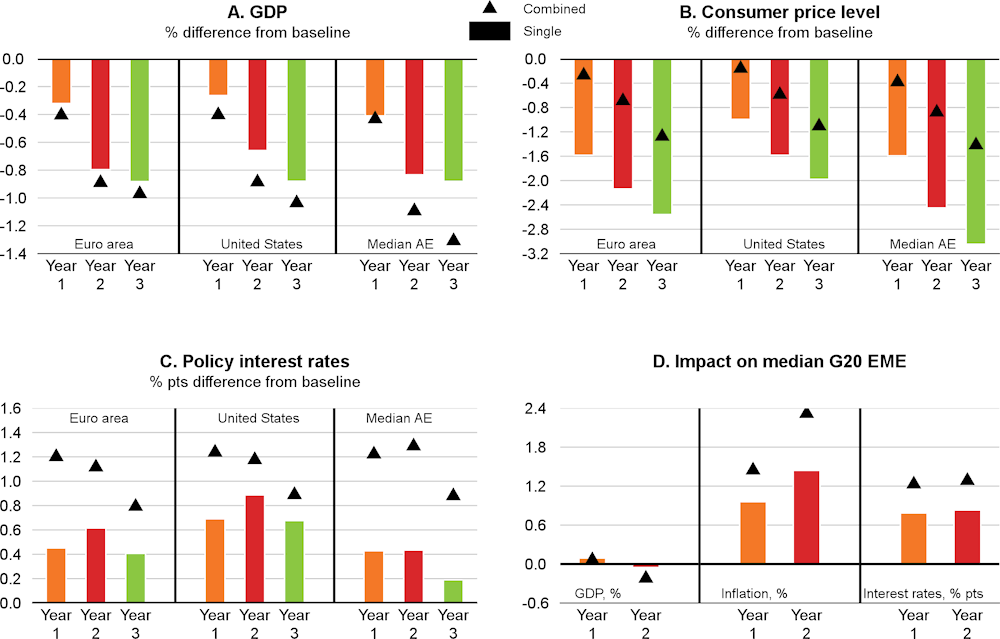

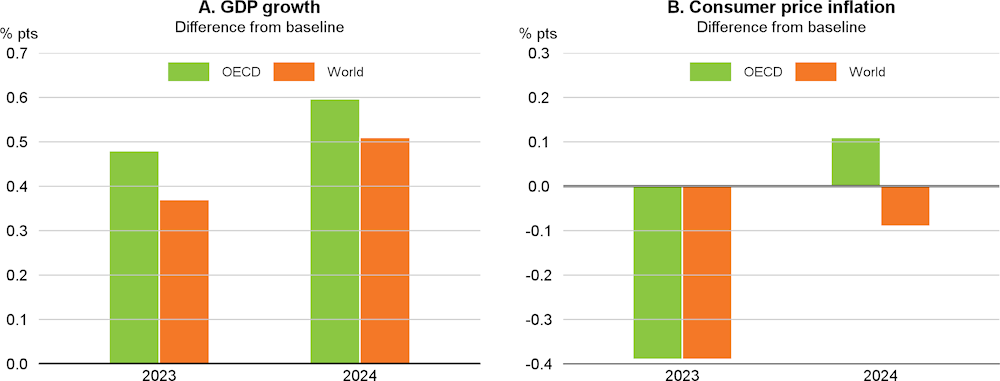

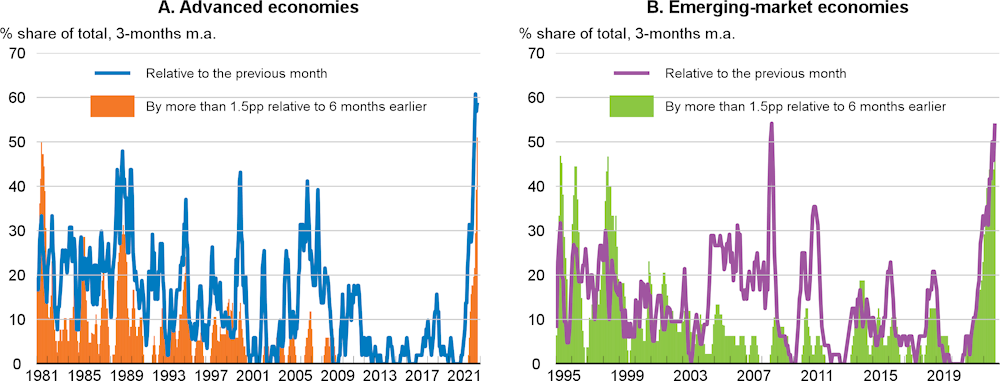

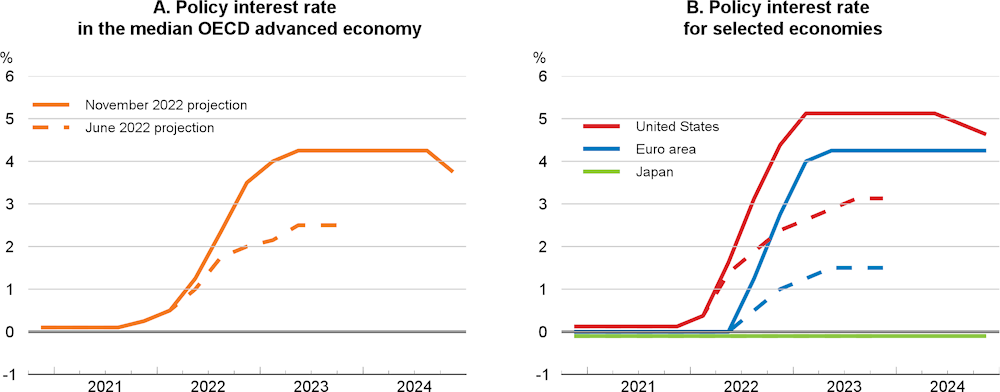

The global economy is facing mounting challenges. Growth has lost momentum, high inflation is proving persistent, confidence has weakened, and uncertainty is high. Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has pushed up prices substantially, especially for energy, adding to inflationary pressures at a time when the cost of living was already rising rapidly around the world. Global financial conditions have tightened significantly, amidst the unusually vigorous and widespread steps to raise policy interest rates by central banks in recent months, weighing on interest-sensitive spending and adding to the pressures faced by many emerging-market economies. Labour market conditions generally remain tight, but wage increases have not kept up with price inflation, weakening real incomes despite the actions taken by governments to cushion the impact of higher food and energy prices on households and businesses. Global GDP growth is projected to be 3.1% in 2022, around half the pace seen in 2021 during the rebound from the pandemic, and to slow further to 2.2% in 2023, well below the rate foreseen prior to the war. In 2024, global growth is projected to be 2.7%, helped by initial steps to ease policy interest rates in several countries. Global prospects are also becoming increasingly imbalanced, with the major Asian emerging‑market economies accounting for close to three-quarters of global GDP growth in 2023, reflecting their projected steady expansion and sharp slowdowns in the United States and Europe. Headline consumer price inflation in the major advanced economies is projected to moderate from 6.3% this year to around 4¼ per cent in 2023 and 2½ per cent in 2024 as tighter monetary policy takes effect, demand pressures wane, and transport costs and delivery times normalise, although the pace of decline will vary across countries.

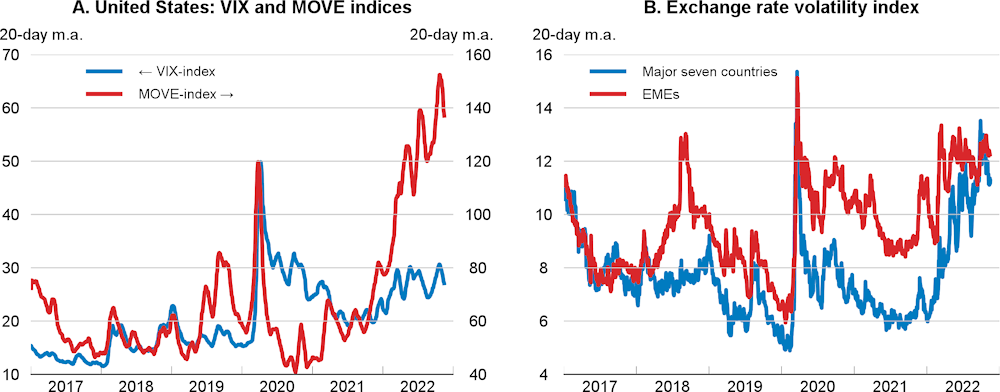

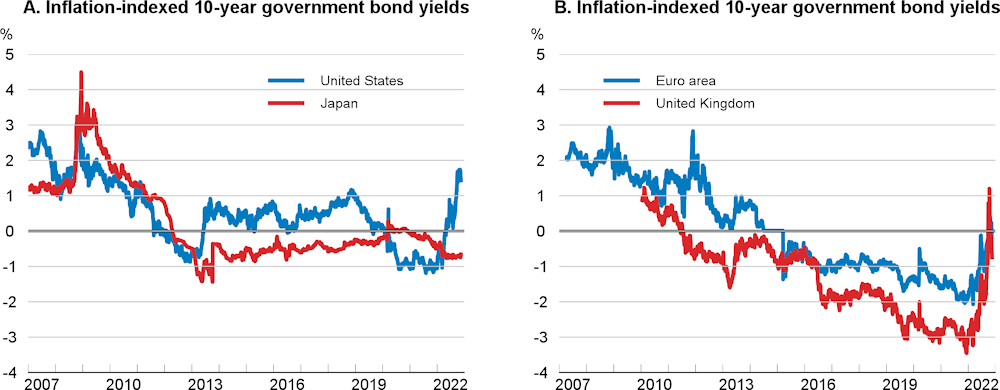

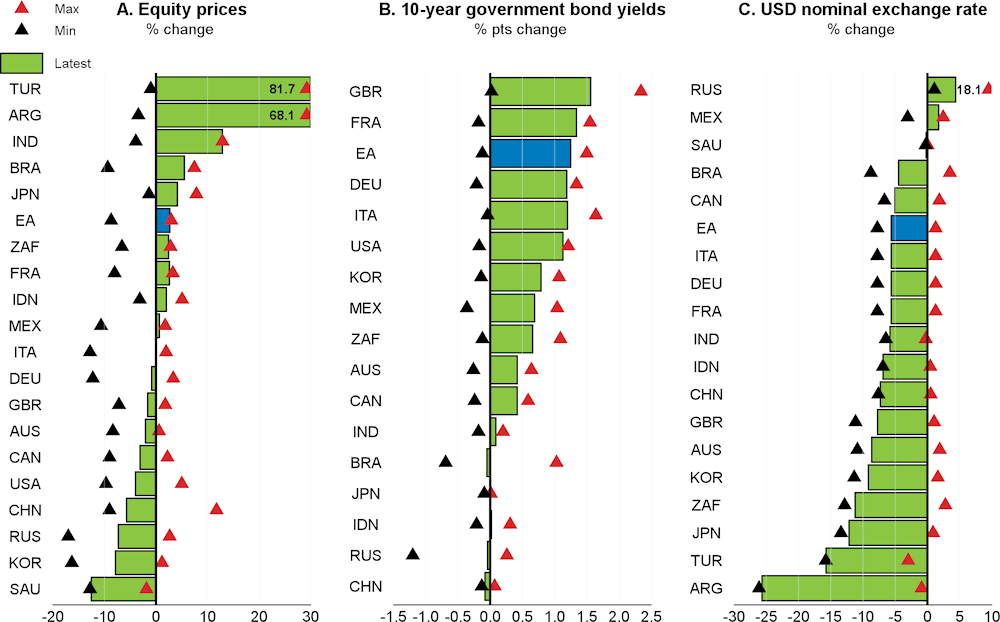

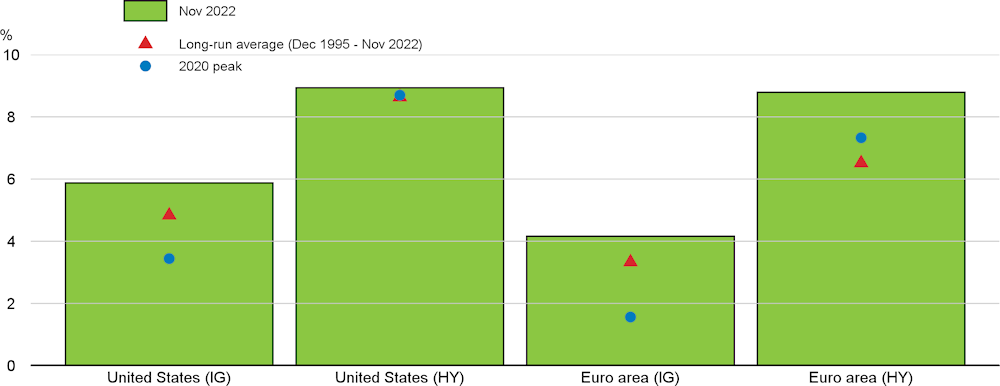

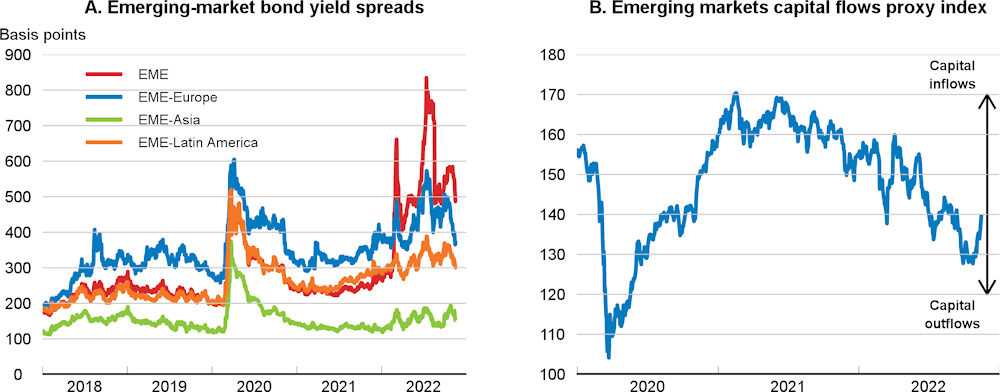

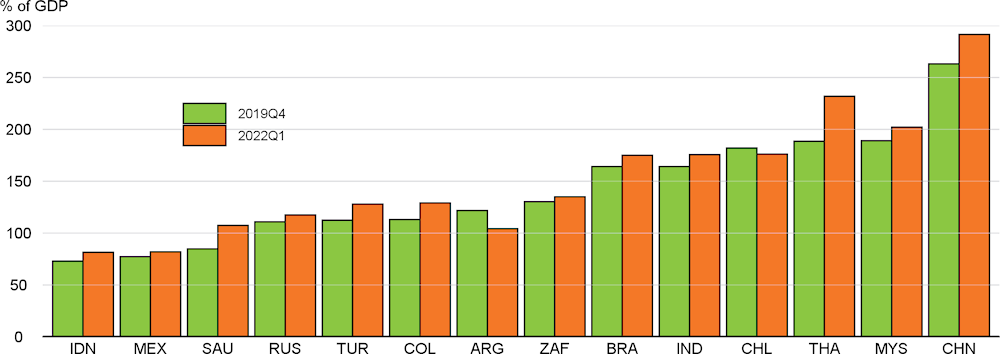

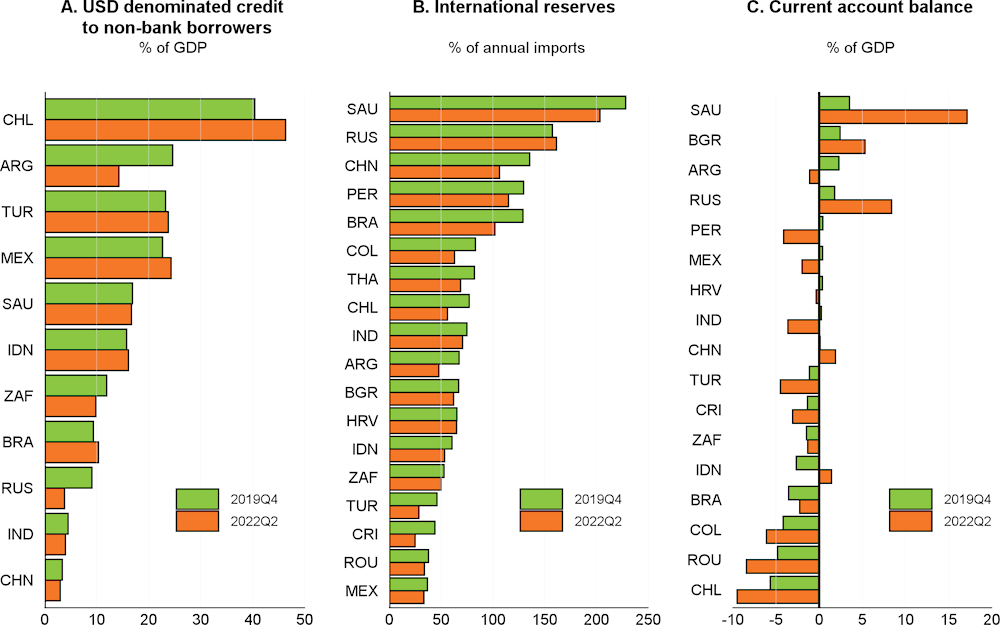

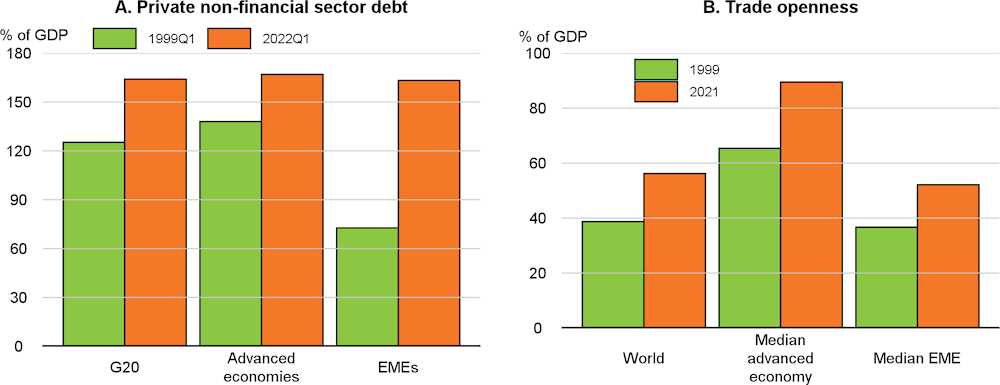

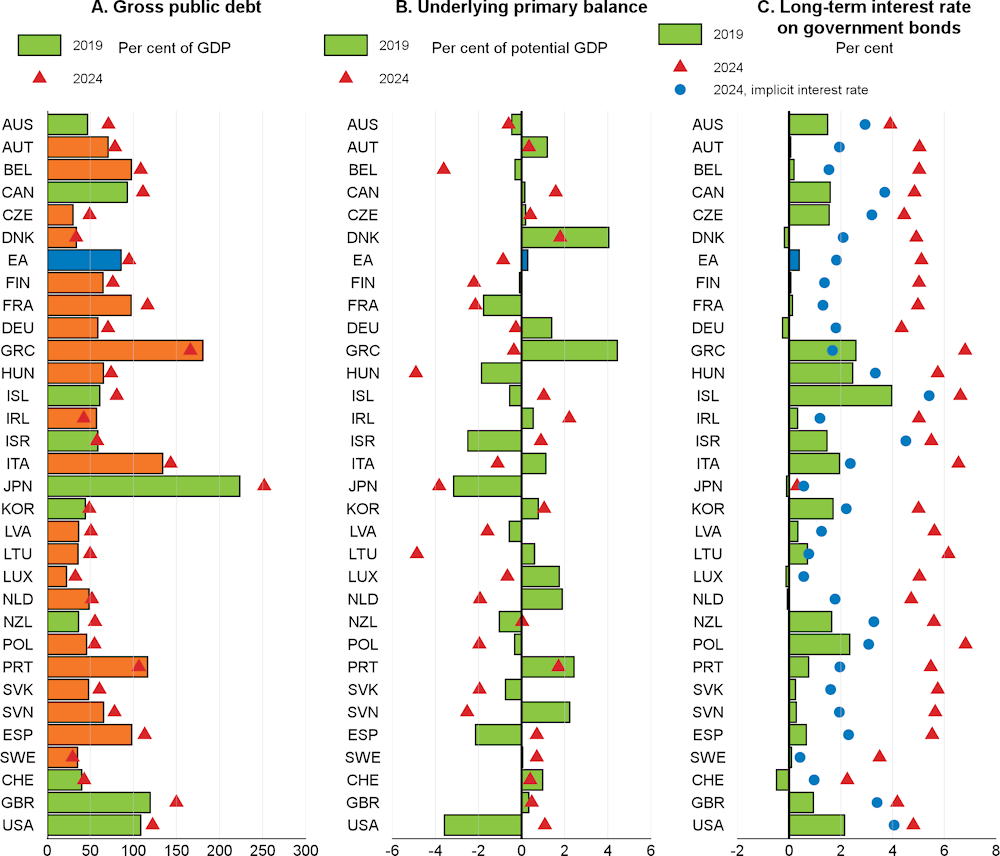

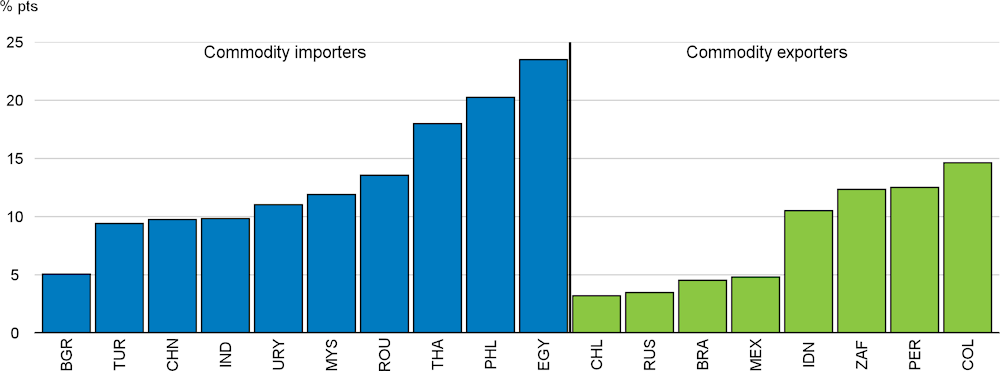

The uncertainty about the outlook is high, and the risks have become more skewed to the downside and more acute. The projections reflect the toll taken by high energy prices over the next two years, but outcomes could be weaker still if there are energy supply shortages in global markets that raise prices further, or if enforced rationing is required to lower gas and electricity demand sufficiently during the next two European winters. Higher policy interest rates could also slow growth by more than projected, with policy decisions difficult to calibrate given high debt levels and strong cross-border trade and investment links that raise the spillovers from weaker demand in other countries. Widespread and rapid monetary tightening also heightens financial vulnerabilities. Financial strategies put in place during the long period of hyper-low interest rates may be exposed by rapidly rising rates and exert stress in unexpected ways. Many emerging-market economies could also face significant difficulties, particularly commodity‑importing economies. Higher interest rates, the appreciation of the US dollar and a deterioration in the terms of trade increase the challenges of servicing elevated external debt and deficits, particularly if growth slows sharply and global financial conditions tighten further. Significant risks also remain about the projected steady expansion in China, with the continued weakness in property markets, rising non-performing loans and the disruptions from the continued zero-COVID-19 policy potentially weighing heavily on domestic demand and global growth. On the upside, reduced uncertainty, easier financial market conditions or lower commodity prices would moderate the slowdown in growth.

Elevated uncertainty, slowing growth, strong inflationary pressure and the ongoing impact of the war in Ukraine on energy markets leave policymakers with difficult choices in order to maintain macroeconomic stability and improve the prospects for sustainable and inclusive growth over the medium term.

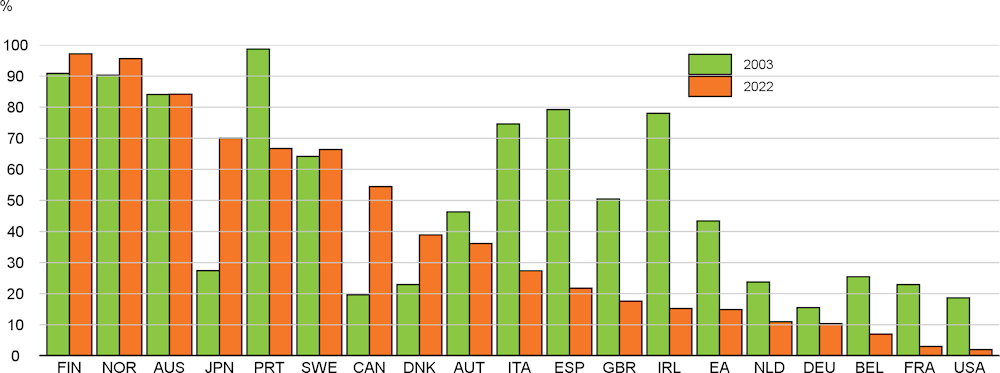

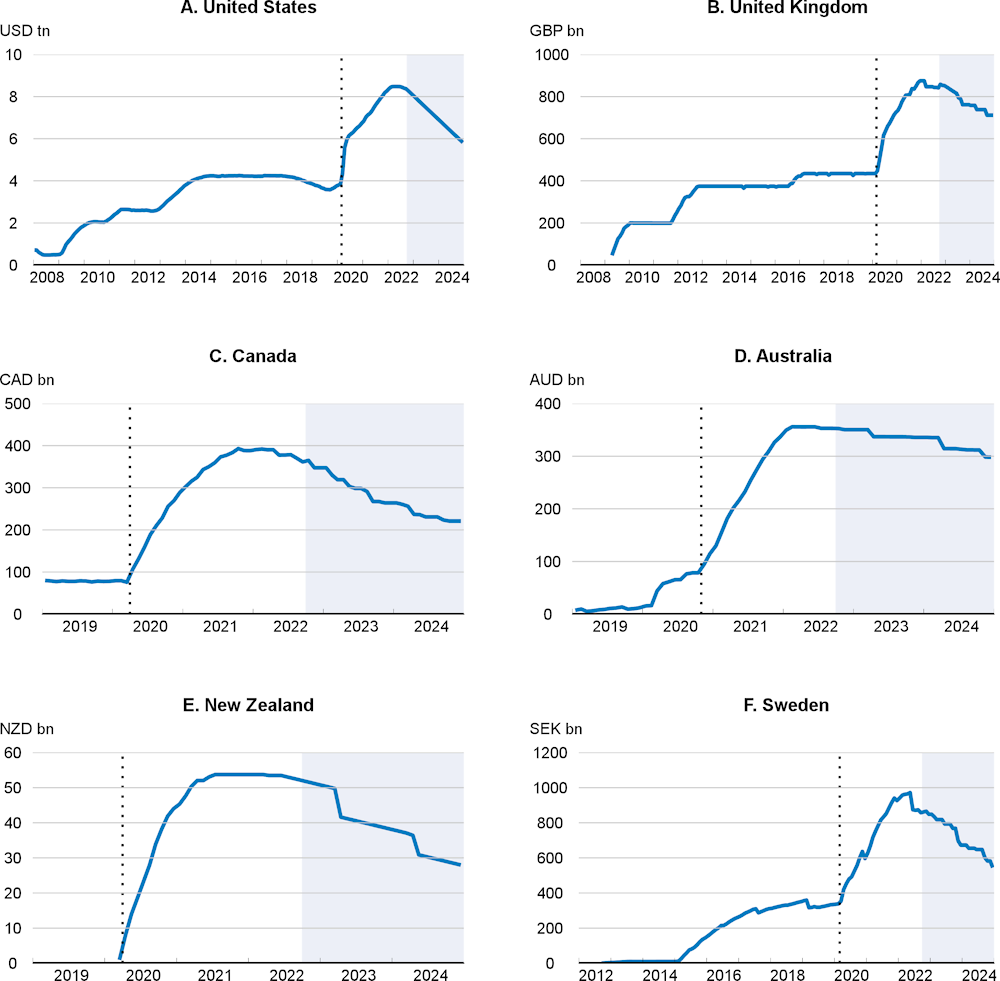

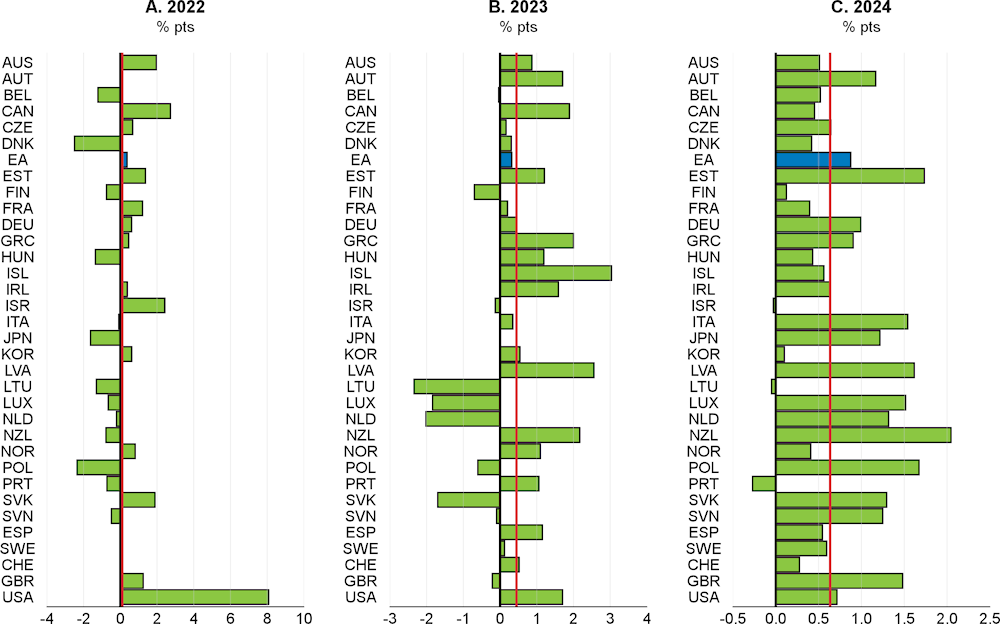

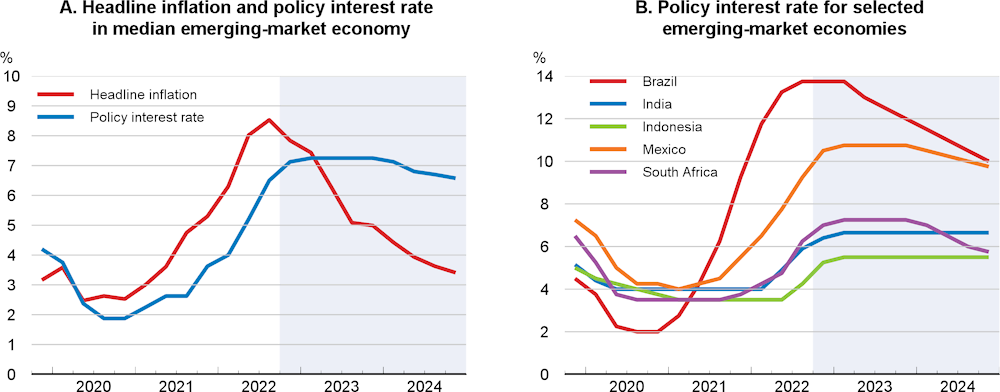

Continued monetary policy tightening is needed in most major advanced economies to anchor inflation expectations and lower inflation durably. Domestic policy measures will need to be carefully calibrated and responsive to new data given uncertainty about the growth outlook, the speed at which higher interest rates take effect and the potential spillovers from restrictive policy in other countries. Tighter global financial conditions and persistent inflation pressures are also likely to prompt further monetary policy tightening in many emerging‑market economies, and limit the scope for any easing in countries where growth is slowing and interest rates have already been raised substantially.

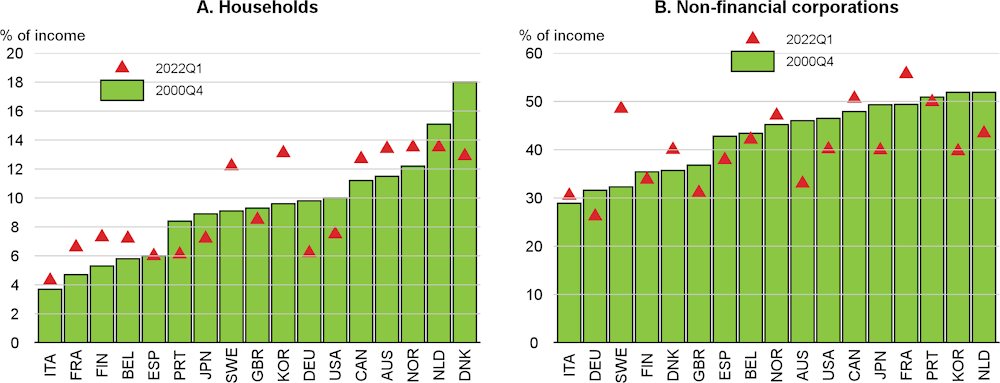

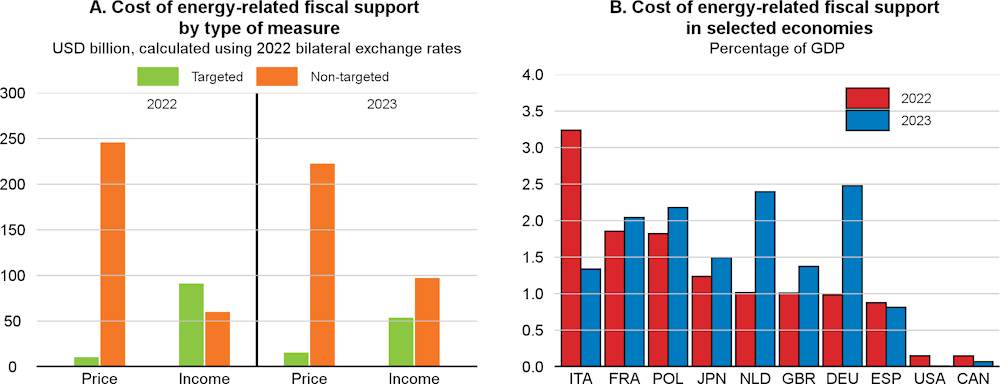

Fiscal support is being provided to help cushion the impact of high energy costs on households and companies. In the absence of such support there would almost certainly be sizeable output declines in many countries, with all of the attendant potential costs these could entail. However, better design is often needed to ensure support is only temporary and concentrated on the most vulnerable households and companies, preserves incentives to reduce energy consumption and can be withdrawn as energy price pressures wane. Short-term fiscal actions to cushion living standards should also take account of the need to avoid a further persistent stimulus to demand at a time of high inflation, thereby ensuring consistency with monetary policy and avoiding adverse effects on fiscal sustainability. Credible fiscal frameworks would help to provide clear guidance about the medium-term trajectory of the public finances and mitigate concerns about debt sustainability at a time of rising spending pressures and higher future payments on public debt.

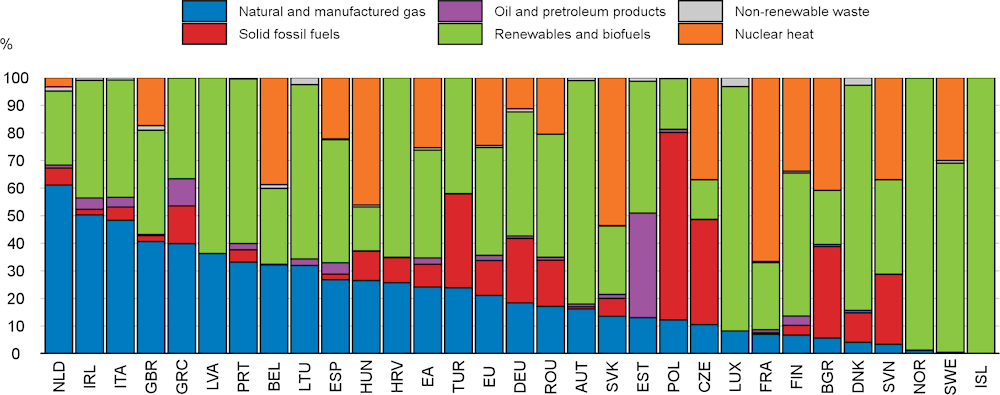

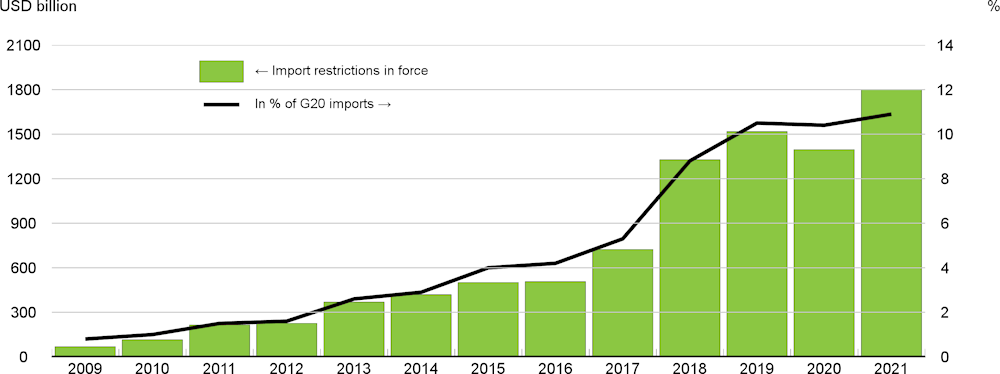

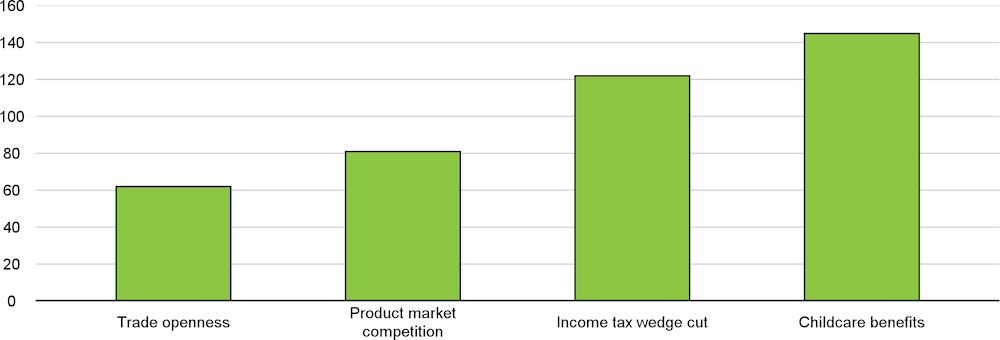

The war and the pandemic add to the longstanding challenges for growth, resilience and well-being from the acceleration of digitalisation, population ageing and the need to lower carbon emissions. Effective and well-targeted reform efforts are required to enhance productivity and skills, reduce inequality and improve gender balance, strengthen resilience and boost living standards. Well‑chosen policies, such as increased support for childcare and reduced tax wedges for lower paid workers, could help to address the current pressures faced by lower-income households and also offer medium-term benefits for employment and inclusion. Keeping international borders open to trade, removing obstacles to stronger cross-border economic migration, and ensuring faster integration of migrants into the labour market would also help to alleviate near-term supply-side pressures on inflation. Governments also need to ensure that the goals of energy security and climate change mitigation are aligned. Efforts to safeguard near-term energy security and affordability through fiscal support, supply diversification and lower energy consumption should be accompanied by stronger policy measures to enhance investment in clean technologies and energy efficiency.

The fallout from the war remains a threat to global food security, particularly if combined with further extreme weather events resulting from climate change. Better international cooperation is needed to keep agricultural markets open, address emergency food needs and strengthen domestic supply. Stronger international co-operation on debt relief, including through the G20, is also necessary to minimise the potential adverse economic and social consequences of default, with a rising number of lower‑income developing countries already experiencing debt distress and having fragile banking sectors.