The coronavirus outbreak abruptly stopped several years of robust economic growth, which had lifted income per capita above half of the OECD average. Although cases were fewer and containment measures less severe than in other countries, the economy contracted strongly in the second quarter of 2020. Public finances are sound and the government took rapid action to support firms and households. Coping with the pandemic and strengthening the recovery will require continued fiscal support, public investment and the advancement of priority reforms. Bulgaria also faces the challenge of how to sustain and ultimately enhance improvements in living standards for all to tackle rising inequality and persistently high poverty. Tackling obstacles to business sector growth will be key to attract investment, boost productivity and provide people with skills to take advantage of new job opportunities.

OECD Economic Surveys: Bulgaria 2021

1. Key Policy Insights

Abstract

The COVID-19 crisis has hit the economy

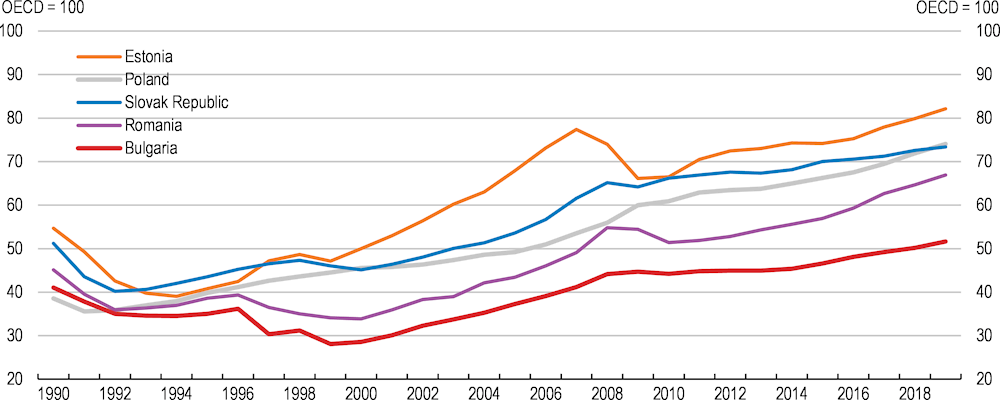

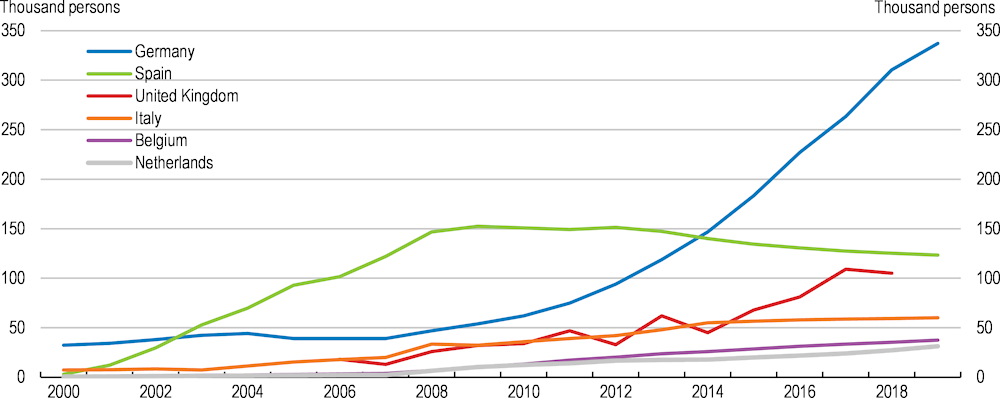

The COVID-19 pandemic hit at a time when the Bulgarian economy was performing strongly: economic growth had exceeded 3% annually for five years, real wages had been rising rapidly and unemployment had fallen to historically low rates. Convergence with OECD income levels had accelerated since 2014 (Figure 1.1) and Bulgaria was making sufficient progress in financial sector, insolvency and institutional reforms to gain membership of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II) and the Banking Union in July 2020.

Figure 1.1. Income convergence had increased from 2014

GDP per capita relative to the OECD average, computed at 2017 USD PPP

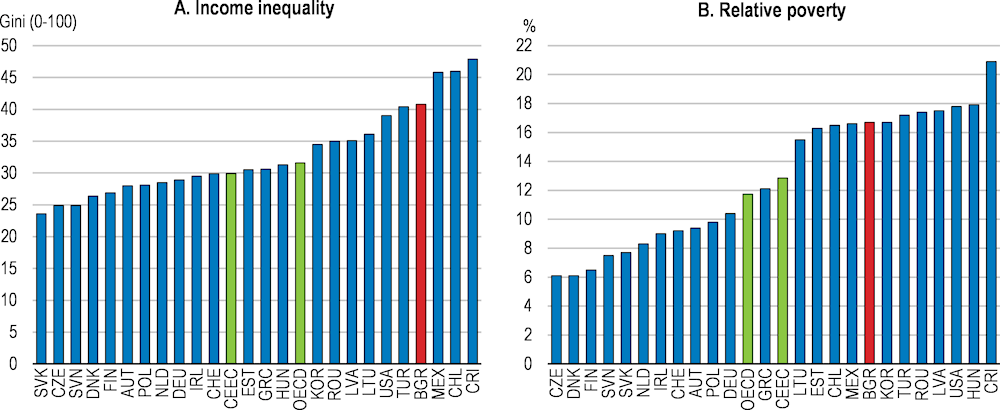

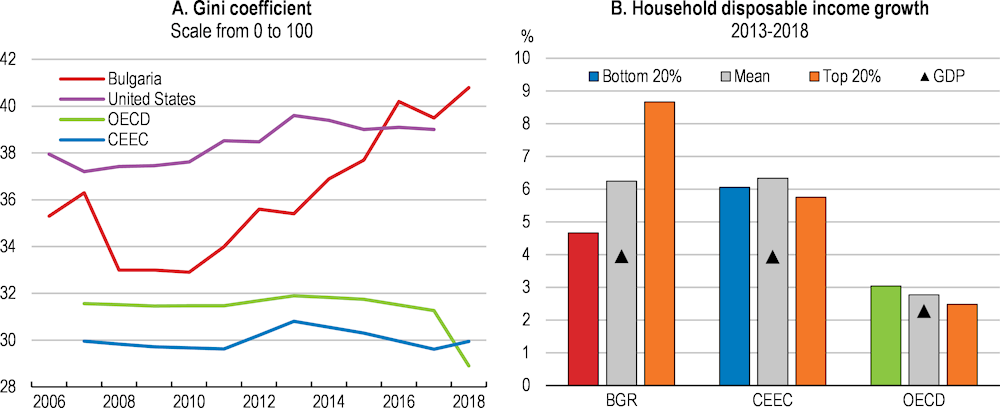

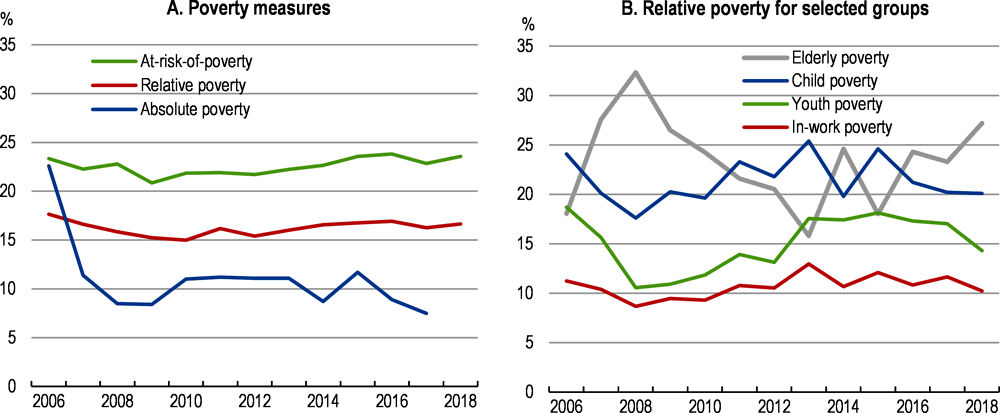

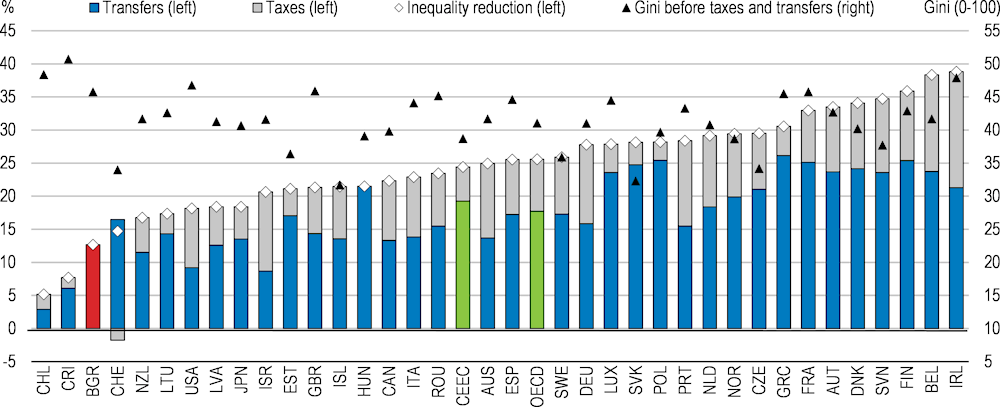

The booming economy translated into robust household disposable income growth, although the most affluent households benefitted the most and income inequality now exceeds almost all OECD countries. Relative poverty is also higher than in many OECD countries, with particular challenges in health outcomes and housing. Life expectancy remains relatively low, while more than half of the population report low life satisfaction, the highest share in the European Union (EU). Gender equality performance is better, with gaps in labour market participation and wages below the OECD averages.

Bulgaria avoided the worst of the initial COVID-19 outbreak, with a comparatively low number of cases and deaths. The first cases were reported on 8 March 2020 and the country quickly moved to introduce confinement measures on 13 March 2020. The shutdown lasted two months, but was less strict than in hard‑hit EU countries. Following the easing of confinement measures, new cases began to increase in July and an upsurge in infections occurred from October. While the country benefits from having a large number of acute care hospital beds, the sharp rise in infections is proving challenging for the health sector. Capacity issues are being reported in some places, perhaps reflecting problems in accessing health care across the country (Chapter 3) and a high prevalence of COVID-19 among medical personal is putting pressure on the system. The positive test rate was very high by November, reaching above 40%, indicating that testing was far too low. The government responded by introducing a comparatively mild set of containment measures at the end of October followed by a closing down of shopping malls, hospitality establishments and stopping physical presences at kindergarten, schools and universities at the end of November.

A sharp drop in economic activity occurred in Bulgaria as the COVID-19 pandemic hit Europe in March 2020. The economic consequences of the pandemic impacted severely service sectors most exposed to disruption from containment measures, especially hospitality and transportation and storage, and had wide implications for the economy given the curtailment of economic activities and a weakening in external demand. The large uptick in cases that began in October has dampened the recovery and if not suppressed could lead to a prolonged negative impact on growth.

The government moved quickly to put in place fiscal measures to support firms and households when it declared a state of emergency in March and has progressively increased and extended support as the enduring impact of the pandemic became clear (Box 1.1). Huge uncertainty surrounds the future course of the virus and, therefore, policy support should not be withdrawn too early. Bulgaria has ample fiscal space to extend the duration of its stimulus package in response to the crisis and to expand the response if required. Poverty and social exclusion remain high and the most vulnerable in the economy will require continued support in the face of such a large income shock.

In their support to the recovery, policymakers will have to balance the need to protect workers and firms and the risk of hindering the reallocation of resources that is always needed after a large shock. Helping workers to find new jobs should prioritise their retraining and upskilling, with a focus on reducing skills mismatches and providing fast-growing sectors with needed talent, for instance Bulgaria’s successful digital sector. Improving access to insolvency and rehabilitation for firms impacted by the crisis is also a priority given the slowness of bankruptcy proceedings and lack of debt restructuring options available to viable, but overly indebted, firms. In addition, boosting support to energy conservation and renewable energy would not only hasten the country’s decarbonisation, but it would also foster innovation. The country should ensure an effective and rapid use of the substantial European Union funding that is available to support the recovery. Once the recovery is well underway, the country should move back towards a balanced budget through a combination of increased revenues and improved spending efficiency, and longer term, continue to ensure fiscal sustainability

Box 1.1. Fiscal policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic

The government put in place a comprehensive package of measures designed to protect households and firms and to ensure adequate health and other services are in place to respond to the pandemic. The main policy measures are:

The 60:40 salary support scheme is the most important tool to support businesses and employees during the crisis. Introduced in March 2020, the government pays 60% of salaries and the employer’s social security and healthcare contributions for employees who face being laid off, with employers covering the remaining 40%. The scheme covers companies engaged in retail, transportation, hotels, restaurants and bars, cinemas, tourism operators and trade fair organisers, private education, human health services, cultural activities, sports and other recreational activities. Companies should have experienced a 20% fall in sales in March 2020, compared to the same month of 2019, to be eligible. Firms need to retain all their staff to qualify. It is expected that the scheme will be applied until the end of March 2021. (cost of 0.6% of 2019 GDP in 2020 and 0.3% of 2019 GDP in 2021)

Additional remuneration costs for staff in the ministries of health, interior and social protection for pandemic-related activities, and expenditures on health, social care, education, tourism and other sectors. The measure is due to remain in place until 2021. (cost of 0.6% of 2019 GDP).

A monthly pension supplement of BGN 50 (about EUR 25) to all pensioners from August until December 2020 and for the first quarter of 2021. (cost of 0.4% of 2019 GDP in 2020 and 0.3% of 2019 GDP in 2021)

The standard 20% VAT rate was reduced to 9% on 1 July 2020 for printed and digital books and textbooks, restaurant and catering services (excluding alcohol) as well as food and hygiene products for babies and small children. On 1 August, the reduced rate of 9% was extended to fees for gyms and other sports facilities, tour holidays and wine and beer served in restaurants and cafes. The reduced rates are due to be in place until 31 December 2021. (cost of 0.1% of 2019 GDP in 2020 and 0.2% of 2019 GDP in 2021).

Deferral of tax return and payments for corporate income taxes and personal income taxes for sole traders from April 2020 until end-June 2020.

The government has provided liquidity support to firms and households through a capital increase of BGN 700 million (0.6% of 2019 GDP) for the Bulgarian Development Bank. Of this, BGN 500 million is destined for the issuance of portfolio guarantees to commercial banks to allow more flexible conditions for business loans and BGN 200 million to guarantee non-interest consumer loans up to BGN 4500 (about EUR 2300) for employees who have gone on unpaid leave as well as for self-employed. The capital injection is expected to increase the availability of credit to firms and households by up to BGN 2.2 billion (EUR 1.25 billion).

Although Bulgaria was performing strongly before the pandemic, it was nonetheless facing a number of structural changes, which will need to be tackled once the economy recovers from the current crisis. Two key long-term challenges are discussed in this Economic Assessment. With an ageing and one of the world’s fastest-shrinking population, Bulgaria will need to put a strong emphasis on increasing productivity growth to generate future growth in living standards; productivity would be stimulated by reforms that improve the business environment (Chapter 2). Demographic decline is having a striking impact on rural regions, with large areas suffering from depopulation due to migration and a rapid ageing of remaining inhabitants. Regional income differences are larger than in most OECD countries and they have increased more across regions with differences in access to larger cities. Future recovery plans should ensure that lagging regions are not left behind. Improving their connection to supply chains through better transport and ensuring that there is enough affordable housing, especially in cities, for workers taking up new jobs, will be essential (Chapter 3).

Against this background, the main messages of this Economic Assessment are:

Macroeconomic support should not be withdrawn too early. The government plans to extend COVID-19 response measures to 2021, by continuing support programmes, and providing enhanced social benefits. There is fiscal space to expand further the stimulus package, if needed. Large flows of European Union resources are expected to fund substantial public investment. Like in other countries, future recovery plans should be well targeted, with a focus on measures to modernise the economy, make it more productive, and accelerate its decarbonisation.

The government should facilitate the reallocation of production factors, which is inherent to post-crisis recoveries. Access to retraining and upskilling will help workers migrate to new jobs and reduce the pervasive problem of skills mismatches. Improving the regimes for insolvency and firm restructuring is also important after a large crisis. Improving competition, fighting corruption, reducing red tape and improving state-owned enterprises (SOE) governance will also help the reallocation of resources across sectors.

The government’s recovery plan should avoid that large groups are left further behind, in particular regions already suffering from ageing, depopulation, and poor connectedness. Policy action is needed to integrate vulnerable populations, such as the Roma, who make up around one-tenth of the population. New approaches to tourism and agriculture provide an opportunity to spur on long-term growth in lagging regions.

The economy requires continued macroeconomic policy support

Hit by considerable economic volatility in the 1990s, the economy stabilised in the 2000s and proved resilient to a number of domestic and external shocks. A Currency Board arrangement has been in place since 1997, with the BGN initially fixed to German mark and subsequently to the euro, following the introduction of the euro as the single currency for the euro area. The Currency Board supported by prudent fiscal policy, has led to a stable exchange rate, low inflation and moderate public debt (Box 1.2). Bulgaria joined the European Union in 2007, the Bulgarian lev was included to ERM II in July 2020, and the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bulgarian National Bank have established a close cooperation over bank supervision as of 1 October 2020, an important policy goal of the government.

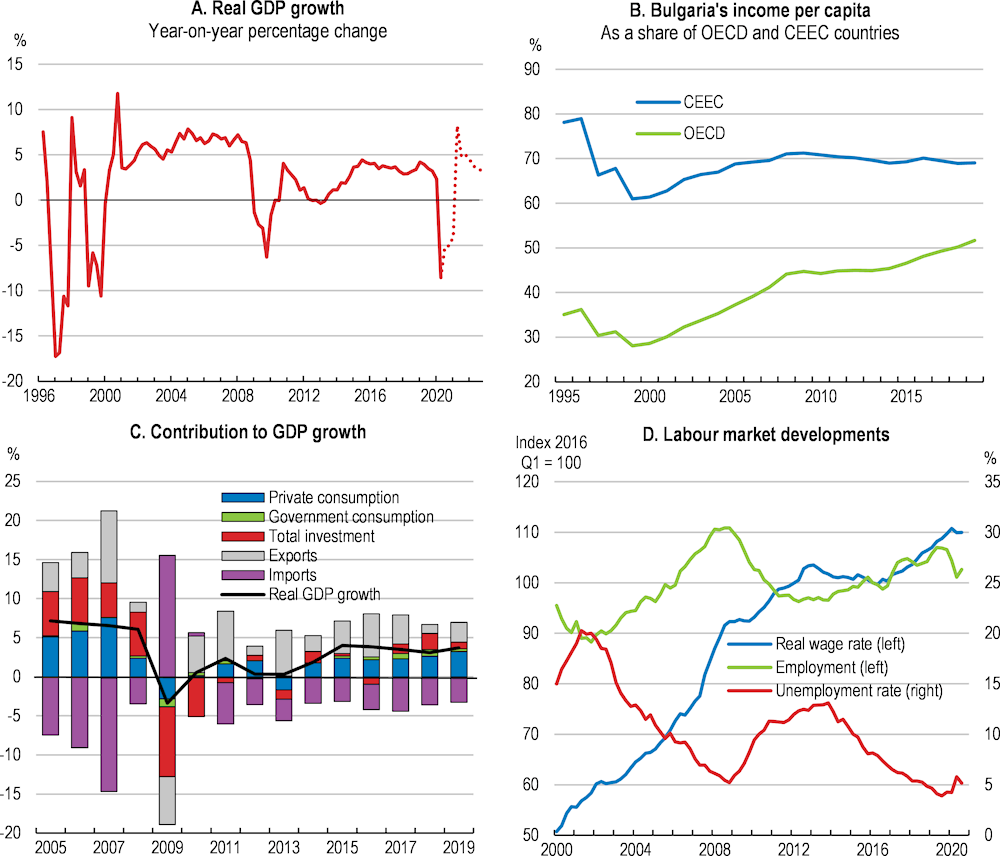

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the economy was growing robustly; employment was high and unemployment was at historical lows. Economic growth had been above 3% since 2015 and convergence with OECD incomes had accelerated (Figure 1.2, Panel A and Panel B). Growth became increasingly driven by domestic demand (Figure 1.2, Panel C) as private consumption grew strongly driven by the rise in employment and the substantial rise in real wages that had occurred due to tight labour market conditions and a large hike in public sector pay (Figure 1.2, Panel D). Consumer and mortgage credit growth has been strong given high wage rises and historically low interest rates. Inflation had begun to moderate due to a deceleration in food prices and lower rises in regulated energy tariffs. The external position remained positive, with the country running continuous current account surpluses over the past seven years. However, export performance had declined, hit by the slowdown in the country's main trading partners.

Box 1.2. From the currency board to adopting the euro

The currency board was introduced in 1997 as part of a stabilisation package, following a period of output volatility, macroeconomic imbalances, and very high inflation. Under this arrangement, the central bank holds only foreign assets and commits to buying and selling domestic currency against the reserve currency (the Euro) at the fixed exchange rate. The central bank does not regulate the money supply through open market operations or the extension of domestic credit as it holds no domestic assets. The ability of the central bank to act as lender of last resort to commercial banks is constrained to the excess foreign exchange reserves.

The currency board proved to be a valuable tool. Inflation was quickly reduced and there was a sharp fall in interest rates following its introduction. The government has generally maintained a fiscal surplus and gross public debt has decreased from 63% to 30% of GDP over 2000-2019. There was no deviation from the fixed exchange rate and the currency board has weathered a series of external and domestic shocks. The Bulgarian Lev was included in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) in July 2020, and, as of 1 October 2020, Bulgaria joined the Banking Union following the implementation of reforms to strengthen financial sector supervision and the macroprudential framework, and to improve the legal frameworks for the governance of state-owned enterprises and anti-money laundering. The central rate of the BGN is set as the rate fixed by the currency board, with a standard fluctuation band of plus or minus 15 percent. Bulgaria has chosen to join ERM II with its existing currency board arrangement remaining in place, as a unilateral commitment, implying no additional obligations on behalf of the European Central Bank.

Preparations for euro area entry will entail continued implementation of institutional reforms, including putting in place a new insolvency framework, as well as maintaining sound economic policies. Real wage and price pressures are likely to re-emerge following the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis given the large differentials in incomes and the price level between Bulgaria and the euro area. To make the convergence process sustainable, increasing productivity, particularly in the non-tradeable sector will therefore be of paramount importance for Bulgaria.

Figure 1.2. The economy was doing well before the COVID-19 pandemic

Note: Panel C: total investment also includes changes in stocks. Panel D: employment and unemployment rate refer to the 15-64 age group.

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook 108 database; World Bank, World Development Indicators database.

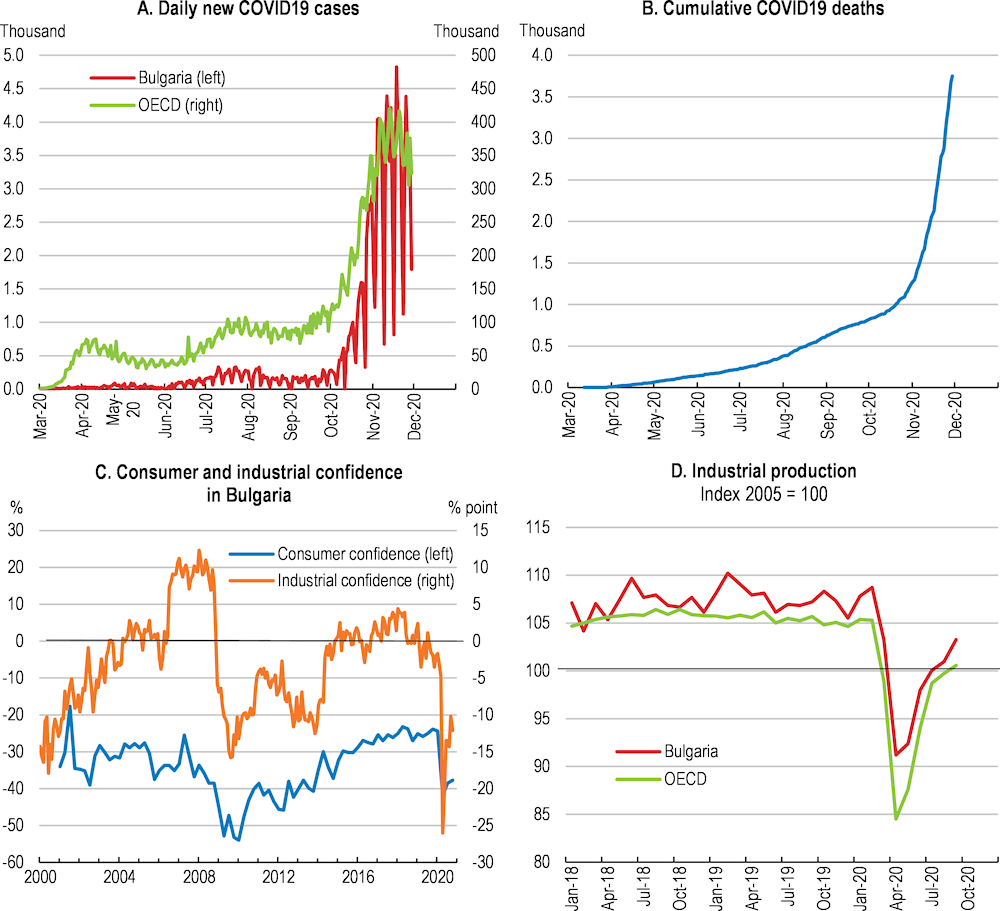

The initial COVID-19 pandemic outbreak was more limited in Bulgaria than in most OECD countries, but a large increase in cases began in October 2020. In the first half of 2020, the number of confirmed cases was lower than in many OECD countries (Figure 1.3, Panel A) and there was a low number of deaths (Figure 1.3, Panel B). However, an upsurge in new cases began in October, deaths began to rise and the health system came under pressure. A relatively mild set of measures, compared to similarly affected European countries, was put in place at the end of October to combat the spread of the pandemic, and subsequently, strengthened at the end of November.

Confinement measures began to affect the economy in March 2020, with the economy contracting by 10% in the second quarter of 2020, as domestic and external demand were badly hit – a contraction not matched since the worst quarter decline during the 1996-97 crisis in Bulgaria (Figure 1.2, Panel A). Household consumption suffered not only due to restrictions on economic activity, but also as labour market conditions deteriorated and uncertainty rose. Deteriorating labour market conditions were eased by the large-scale wage subsidy support programme (Box 1.1). Employment fell by 1.5% between end-2019 and the third quarter of 2020, while unemployment rose from 4.3% in fourth quarter of 2019 to 4.8% in the third quarter of 2020 (Figure 1.2, Panel D). Inflation fell, driven by the fall in international energy prices, the slowdown in core inflation and the cut in regulated natural gas and heating prices.

Figure 1.3. After a low initial outbreak, COVID-19 infections began to increase in October 2020

Source: OECD, Main Economic Indicators database; CEIC; https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-source-data.

Service activity fell by 10% in April 2020 compared to the previous month. Manufacturing activity, mainly oriented at export markets, declined across the board in April and May, with the exception of some niche subsectors, such as pharmaceuticals. Declining industrial turnover occurred due to both lower volumes and prices. Exports were hit hard by the fall in production and external demand, but the decrease in imports was larger in the first seven months of the year, narrowing the trade deficit. Private investment fell sharply as enterprises dealt with an abrupt decline in activity and a high degree of uncertainty. This was somewhat compensated for by the increase in public investment fuelled by EU funds.

Considerable uncertainty surrounds the recovery

A recovery is underway, but its path remains highly uncertain given the rise in COVID-19 infections and the revival in confidence remains vulnerable. The re-opening of businesses and the relaxation of containment measures was accompanied by a recovery of activity that took on momentum in July 2020. Business confidence sharply increased in June and consumer confidence also started to rebound, even though the fear of unemployment went up (Figure 1.3, Panel C). Industrial production increased, though it remains below February 2020 levels (Figure 1.3, Panel D). Service sector activity, particularly restaurant and accommodation activity, likely will be slow to rebound substantially until the pandemic eases. The economy had contracted by 5.2% by the third quarter of 2020 compared to the same quarter in 2019 based on seasonally adjusted data, a contraction slightly higher than the European Union average of 4.3%. The decline in activity was driven by a fall in the investment and exports, with private consumption contracting by less than in many European Countries given the milder initial pandemic and containment measures.

A recovery is underway, but its path remains uncertain, particularly given the current large rise in COVID-19 infections. The economy is expected to shrink by 4.1% in 2020 (Table 1.1), but is projected to recover to its pre-crisis level in 2022. Fiscal support will determine the strength of the recovery, with a large shift from pre-crisis fiscal surpluses to projected deficits of about 4% of GDP in 2020 and 2021. The surging pandemic will weigh on business confidence and private investment, and sporadic outbreaks will hold down growth until vaccination against the virus becomes general. Strong public investment, financed by European Union resources, will then drive the revival of investment. Trade is set to recover gradually, contributing positively to growth in 2021 and 2022. The prolongation and deepening of containment measures is a significant downside risk that would constrain the normalisation of domestic demand.

Table 1.1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Current prices BGN billion |

Percentage changes, volume (2015 prices) |

||||

|

GDP at market prices |

102.3 |

3.1 |

3.7 |

-4.1 |

3.3 |

3.7 |

|

Private consumption |

61.6 |

4.4 |

5.5 |

-0.7 |

2.7 |

3.1 |

|

Government consumption |

16.0 |

5.3 |

2.0 |

4.1 |

3.7 |

3.0 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

18.8 |

5.4 |

4.5 |

-8.4 |

5.8 |

4.4 |

|

Final domestic demand |

96.4 |

4.8 |

4.6 |

-1.4 |

3.5 |

3.4 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

1.6 |

1.1 |

0.0 |

-2.6 |

-0.3 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

97.9 |

5.8 |

4.6 |

-4.2 |

3.1 |

3.4 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

68.9 |

1.7 |

3.9 |

-10.7 |

6.0 |

5.7 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

64.4 |

5.7 |

5.2 |

-9.9 |

6.1 |

5.3 |

|

Net exports1 |

4.4 |

-2.5 |

-0.7 |

-0.8 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

|

Memorandum items |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GDP deflator |

- |

4.0 |

5.3 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

|

Consumer price index2 |

- |

2.8 |

3.1 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.8 |

|

Core consumer price index2 |

- |

2.1 |

1.8 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

1.8 |

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

- |

5.2 |

4.2 |

6.4 |

6.1 |

5.1 |

|

Household saving ratio, net (% of disposable income) |

- |

1.2 |

1.0 |

1.6 |

-2.6 |

-4.3 |

|

General government financial balance (% of GDP) |

- |

2.0 |

1.9 |

-4.4 |

-4.5 |

-2.6 |

|

General government gross debt (% of GDP)3 |

- |

31.8 |

29.9 |

34.4 |

38.6 |

40.7 |

|

General government debt, Maastricht definition (% of GDP) |

- |

22.3 |

20.2 |

24.6 |

28.9 |

31.0 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

- |

1.0 |

3.0 |

3.1 |

2.9 |

3.1 |

1. Contributions to changes in real GDP, actual amount in the first column.

2. Period averages, the core consumer price index excludes food and energy.

3. Consolidated gross financial liabilities of the general government sector.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 108 database.

The global economy faces an uncertain outlook, its recovery depending on the size and length of new COVID-19 outbreaks, the extent of containment measures put in place, the time it takes to provide vaccines and/or attain more effective treatments (OECD, 2020a). The main downside risks facing the economy are a protracted global slowdown due to COVID-19 and a continued high COVID-19 caseload that would constrain the normalisation of domestic demand. Aside from these bigger risks facing the economy, there are additional potential vulnerabilities, with low probabilities, that could have large implications for the economy (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2. Low probability vulnerabilities

|

Shock |

Possible impact |

|---|---|

|

Health pandemics |

The coronavirus outbreak stressed the risks and economic costs from future pandemics. Even if Bulgaria would contain a new outbreak, the shock to tourism and supply chains could be huge. |

|

Political instability |

Absent a resolution, the current political conflict and social unrests could lead to a prolonged period of political instability and pause the structural reform agenda. |

|

Disruptions to international trade due to a growth in regional and global trade tensions |

A small, open economy, which is deeply integrated in global values chains, Bulgaria would suffer from a decrease in trade due to increased tensions. |

|

An extreme natural disaster |

Areas of the country are vulnerable to earthquakes, flooding and forest fires. A severe natural disaster would require large disaster relief, putting pressure on government finances, and could negatively impact on regional long-term growth. |

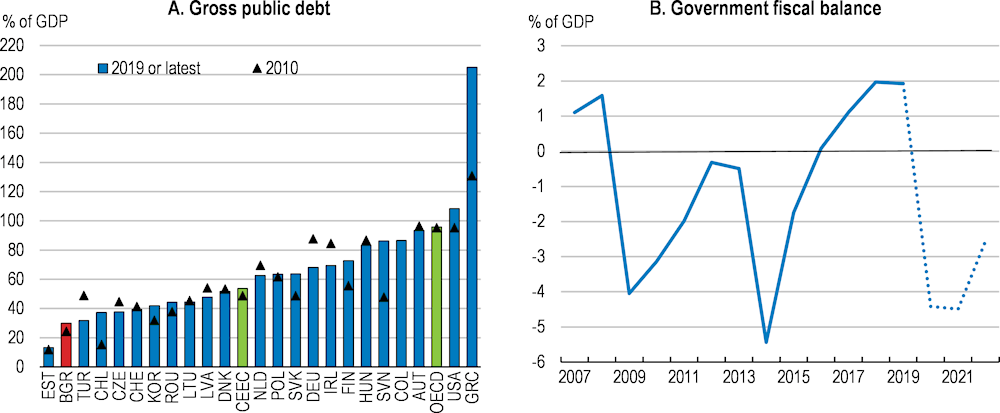

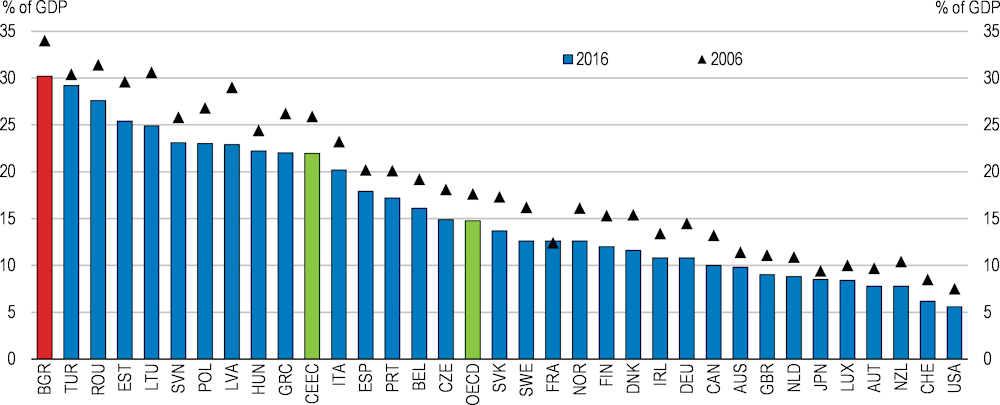

Fiscal space permits a large pandemic response

Bulgaria has reduced its vulnerability to shocks through prudent fiscal policy that has decreased public debt significantly and minimised sovereign financing risks. Fiscal rules put in place from the early 2000s onwards restricted deficits and brought down public debt. In addition to complying with the limits set by EU’s Growth and Stability Pact, with the latest amendments in the Public Finance Act the country has a deficit ceiling of 3% of GDP for the cash-based deficit under the consolidated fiscal programme and an expenditure ceiling of 40% of GDP for spending under the consolidated fiscal programme excluding expenditures made from EU funds accounts as well as expenditures under other international programmes and treaties with a regime of EU funds accounts and the national co-financing related to them. Gross public debt fell from 63% to 30% of GDP over 2000-2019; only one OECD country has lower public debt levels (Figure 1.4, Panel A). The country entered the COVID-19 pandemic in a strong fiscal position, having run a general government surplus of 2% of GDP in 2019 (Figure 1.4, Panel B). Fiscal reserves provide an additional buffer and stood at EUR 7 billion or 11% of GDP at end-September 2020 based on Ministry of Finance data.

The government’s fiscal support in response to COVID-19 was rapidly enacted: measures to protect households and firms were introduced in March 2020, subsequently increased in summer 2020 and extended into 2021 in November 2020 (Box 1.1). The budgetary constraints established by fiscal rules at the EU level have been lifted for all countries to allow them to respond to the pandemic. Financing for the overall stimulus package, which is estimated to have a budget cost of about 3% of GDP in 2020 and 2.5% of GDP in 2021, has come from national and EU resources. A fiscal deficit of about 4% of GDP is expected in both 2020 and 2021. The government intends to avoid removing temporary support too quickly.

Figure 1.4. Sound public finances leave room for fiscal stimulus

Bulgaria is set to receive substantial support from EU funds. Resources from the EU are expected to total EUR 24.1 billion or 39% of 2019 GDP over 2021-2027. Under the Multiannual Financial Framework, Bulgaria is expected to receive EUR 16.6 billion or 27% of 2019 GDP, with the biggest components being resources for Cohesion Policy and the Common Agricultural Policy. The new recovery instrument NextGenerationEU is expected to provide an additional EUR 7.5 billion in grants, with further potential lending of EUR 4.5 billion. Of this, the European Union Recovery and Resilience Facility is to provide resources of about 10% of pre-crisis GDP. A draft national plan has been drawn up for using the Recovery and Resilience Facility resources and is due to be submitted to the European Commission following public consultations. The draft plan foresees a substantial amount of resources going to make the economy greener, large investments in innovation and regional connectivity, such as improving transport and digital connectivity, and substantial assistance to increase the inclusion of disadvantaged groups and individuals in the economy.

Ensuring access to health care is a priority during the pandemic

Spending on health is relatively low and further funding may be necessary to deal with the pandemic as it unfolds. Increased health and related sector spending (0.6% of 2019 GDP) has allowed the government to extend free access to primary care services related to COVID-19, introduced early on during the pandemic. Supporting the population to access COVID-19 related health services is important given that out-of-pocket payments are high, accounting for almost 40% of current healthcare expenditures in 2018, among the highest shares in the EU (Chapter 3).

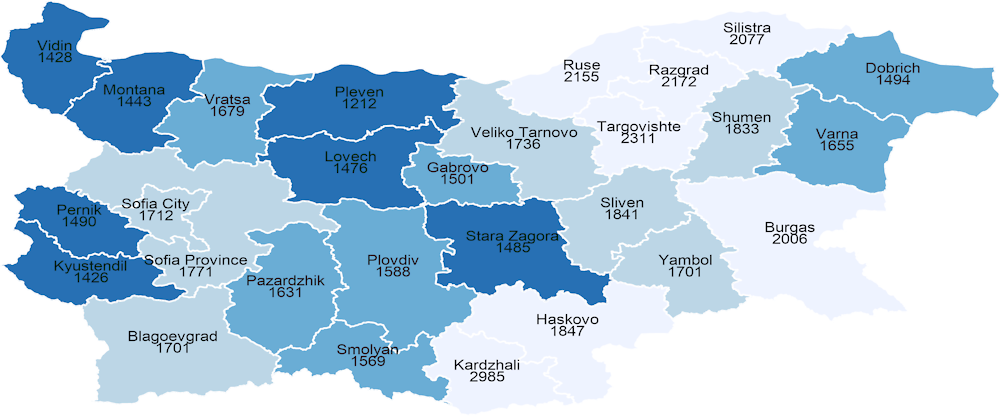

Accessing primary care can be difficult, with a low number of general practitioners, particularly in rural areas. The population per general practitioner varies from almost 3 000 in the southern Kardzhali region to 1 200 in Pleven (Figure 1.5). General practitioners play an important role in managing COVID-19, given that it is either they or an emergency care unit that has to prescribe a test for the state budget to cover it. The lack of primary care carries with it the risk that those impacted by COVID-19 may go straight to emergency facilities, a concern should the number of cases increase substantially. During the first wave, the health system was able to cope with a comparatively low number of hospitalisations. Hospital capacity is high, with 7.6 beds per 1 000 population, well above the OECD average of 4.7. However, several hospitals came under pressure as the number of cases increases rapidly during the second wave of the pandemic.

Figure 1.5. Access to general practitioners is unequal across regions

Population per general practitioner, 2019

Source: OECD calculations based on Bulgarian National Statistical Institute.

A wage subsidy scheme has prevented a large rise in unemployment

The government’s wage subsidy scheme (Box 1.1) has prevented a much sharper rise in unemployment and a larger deterioration in household incomes, while supporting the most impacted firms with their costs. It protected 7% of workplaces in 2020 Q2. The programme is due to be applied until the end of March 2021. For the tourism industry, the compensation rate was increased to 80% (Chapter 3).

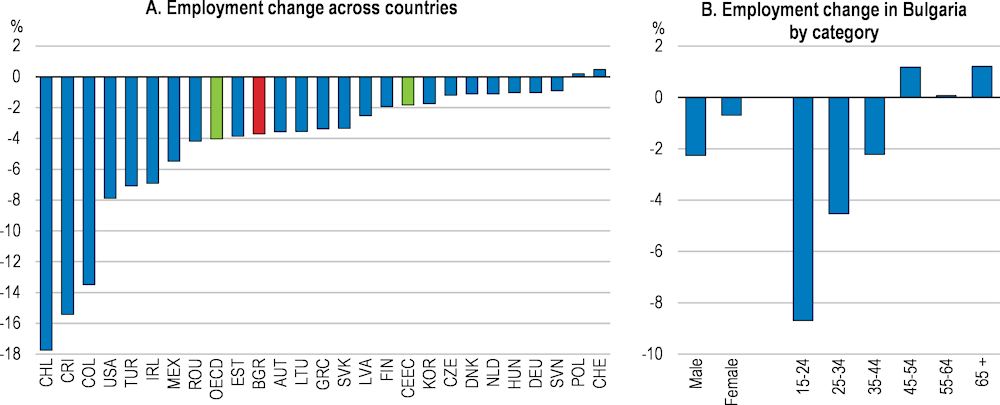

Employment of men and youth has been hit hardest by the economic contraction. Employment of 15 to 64 year olds fell by 1.5% by the third quarter of 2020 compared to the last quarter 2019. The fall in employment is on the lower side compared to OECD countries (Figure 1.6, Panel A). In contrast to many other OECD countries, men’s employment has fallen by more than that of women between the last quarter of 2019 and the third quarter of 2020 (Figure 1.6, Panel B). As with many OECD countries, youth are losing out: the employment of those aged 15-24 has fallen by more than five times the national average (Figure 1.6, Panel B).

Figure 1.6. Employment situation of the young most negatively affected

Percentage change between 2019 Q4 and 2020 Q3

Note: 2020 Q3 data for Austria, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Mexico, Romania, Slovak Republic, Turkey and CEEC are estimates.

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook database; National Statistical Institute.

The pattern of informality in the economy limits the income replacement rate of the 60:40 wage subsidy scheme for many workers. Informal employment is mainly due to an additional payment not included in a worker’s contract on which taxes, health and social insurance contributions is not paid (“envelope wages” or “under declared work”) (Box 1.3). Many workers in the hard-hit sectors are reported as earning only the minimum wage, despite usually receiving top-up payments and thus now have to survive on lower incomes. This presents a dilemma for policymakers. It is important to offer appropriate protection, but a strong incentive for formality in Bulgaria is the link between the amount of social contributions paid and the benefits received.

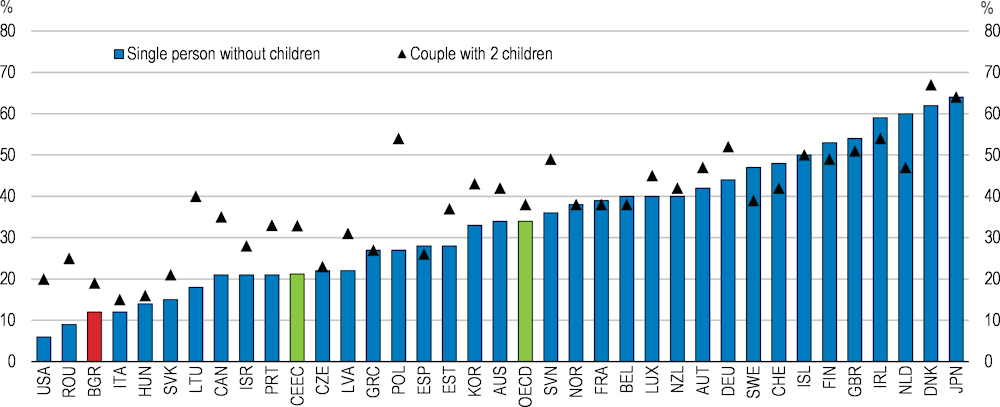

The discretionary 60:40 wage subsidy scheme is critical for the protection of the population given that there are limited automatic schemes that kick in for those who suffer income loss in downturns. The size of automatic income stabilisation has been found to be the lowest in the EU (European Commission, 2017). Many do not qualify for unemployment schemes; means-tested benefits are low with a small share of the population benefitting. There is a high risk of poverty in the economy and so the retention of some type of discretionary scheme will be important, particularly to protect low-income households.

Across OECD countries, direct and indirect support for wage costs has been the key intervention to provide liquidity support to firms. If demand takes a long time to re-emerge in some hard-hit sectors, the challenge will be for policy to strike the right balance between supporting viable jobs and enterprises and not inhibiting re-allocation of workers into new jobs.

Box 1.3. The informal economy is sizeable

Bulgaria has a large informal economy compared to most OECD countries (Figure 1.7). Still, informal activity has declined over time and the degree of informality is in line with the country’s level of development (Medina and Schneider, 2017).

The pattern of labour informality differs from other EU countries in that the incidence of partly undeclared (envelope) wages is high, while working without a contract is rare according to surveys. Only 1% of workers reported being employed without a formal written contract in 2019, among the lowest shares in the EU (European Commission, 2020a). By contrast, Bulgaria stands out with only 80% of employees denying receiving undeclared cash payments, well below the EU average of 95%. In another survey, almost 15% of employees reported receiving an envelope wage with the mean amount undeclared composing 30% of their net income (Williams and Yang, 2017). Moreover, in nearly one third of cases, the employee took an active role in initiating the illegal practice.

Undeclared work is more commonly reported in more labour intensive, lower skilled sectors. Workers admitting to carry out under declared work are in construction (35%), agriculture (17%), retail or repair services (13%) and personal services (13%) (European Commission, 2020a). While no information was available for the hospitality sector, a sizeable share of undeclared work is likely, notably in seasonal tourism jobs. For agriculture, an amendment to the labour code in 2015 to permit a daily labour contract for seasonal work resulted in a large increase in registered workers.

Figure 1.7. The informal economy amounts to almost one-third of (official) GDP

Estimated size of the informal economy

Source: Schneider, F. (2016), "Estimating the Size of the Shadow Economies of Highly-developed Countries: Selected New Results", CESifo DICE Report, ifo Institut - Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung an der Universität München, München, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 44-53, https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/167285.

Long-term public finances are sound but subject to uncertainties from ageing

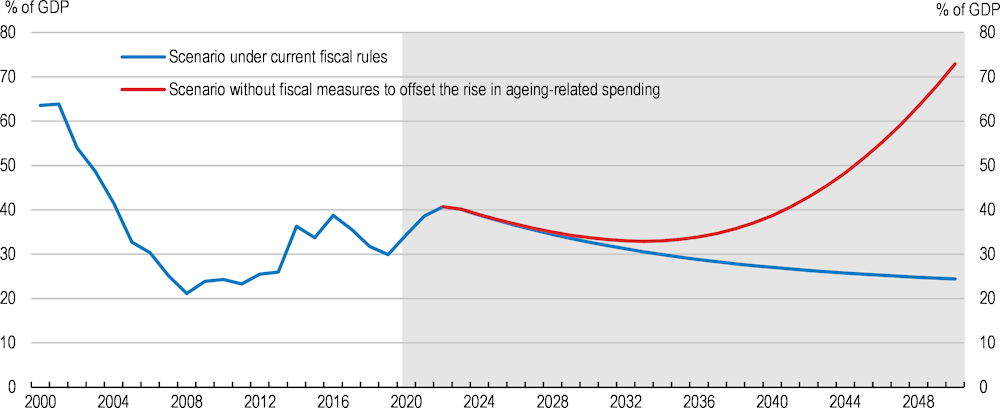

Public debt is projected to remain low in the medium-term despite the sizable fiscal response to COVID-19, though rising ageing costs are likely to lead to higher spending pressures going forward. Lower output and fiscal deficits of 4% of GDP in 2020 and 2021 lead to a rise in public debt. The projections incorporate an increase over time in pension and healthcare spending due to ageing and a rise in the demand for public services based on the OECD long-term model (Guillemette et al., 2017). In the scenario showing the debt trajectory under current fiscal rules, the ageing-related spending rise is offset by revenue increases and/or spending reduction measures. Under this scenario, the structural primary deficit is projected to be eliminated by 2024 and gross government debt is then expected to follow a declining path (Figure 1.8). To illustrate the large potential impact of ageing-related spending pressures, a scenario is included showing the effect of an increase in ageing-related spending occurring without compensating increases in revenues and/or expenditure savings. This would push the public debt trajectory higher. A large degree of uncertainty must be attached to any long-term simulations at this point in the pandemic and so the long-term debt path is subject to risks. Certain public monopolies or SOEs established by a special law are legally protected from insolvency and so their liability is a contingent liability to the state (OECD, 2019a). The aggregate debt of SOEs was 13% of GDP in 2016 (OECD, 2019a).

Figure 1.8. Ageing-related spending pressures could push up public debt

Gross government debt

Note: The projections incorporate actual outcomes until 2019, OECD projections until 2022 and from 2023 are based on the OECD long-term model estimates (Guillemette et al., 2017). Ageing-related costs for pensions and health care are expected to rise in both scenarios. The difference between the two scenarios is that in the scenario simulating the public debt path, “under current fiscal rules” assumes that offsetting revenue increases and/or spending reduction measures are put in place to compensate for the rise in expenditures due to ageing.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Economic Outlook 108 database.

Population ageing is likely to pose a large longer-term fiscal challenge. Despite having a population that is rapidly growing older, Bulgaria is projected to remain at the lower end of ageing spenders under the latest EU ageing fiscal cost projections (European Commission, 2018a). However, greater spending pressures are likely to emerge than projected in the EU ageing exercise for long-term care, health and pensions.

Long-term care services are provided informally, often by family members, and formal provision is low (Chapter 3; European Commission, 2018a). Long-term care is excluded currently from the health benefits’ package. Spending on long-term care is not projected to rise much above the current 0.4% of GDP in the EU ageing scenario, which remains well below the EU average of 1.6% in 2016. Pressure to increase the public provision and financing of long-term care services may grow by more than expected in coming decades as the country becomes richer and the opportunity cost in terms of foregone formal employment increases for the large proportion of female informal carers. In addition, the costs of providing long-term care services may increase towards those of the EU average as living standards increase in Bulgaria.

Pension spending will face additional pressures as an increasing share of the population reaches retirement age in the coming decades. The three-pillar pension system consists of a pay-as-you-go, statutory state pension, a mandatory supplementary scheme based on individual retirement savings accounts, and supplementary voluntary pension insurance, funded personal and occupational schemes. The statutory pension age is 61 years and six months for women and 64 years and three months for men in 2020. A pension reform in 2015 increased the contribution rate and determined the statutory retirement ages for men and women to gradually rise and equalise to 65 years of age by 2037. The increase in the retirement age put in place in 2015 was more gradual than the 2011 reform it replaced. The retirement age is due to be linked to increases in life expectancy after it reaches 65 in 2037. Participants under the second pillar were given the possibility under the reform to opt out and transfer their individual savings from management by private pension funds to the State Pension Fund (first pillar). Given that the ageing population and shrinking workforce are set to result in a growing social security deficit, a faster equalisation of the male and female retirement age, an immediate linkage of the retirement age and life expectancy rises, and further reforms, such as rises in contribution rates, would increase the sustainability of the pension system.

The difficult circumstances faced by many older people due to low incomes could increase social pressures to increase the adequacy of retirement incomes. Total public pension benefits compared to the last average wage earned, i.e. the replacement rate, are relatively low at 29% compared to 43% on average in the EU in 2016 (European Commission, 2018a). Current pension benefits are insufficient to protect the population from poverty. Nearly half of those over 65 years of age are at risk of poverty or social exclusion and a high share live in households that suffer from severe material deprivation. The government has made efforts to increase the basic pension to raise living standards for the most vulnerable old-age groups in recent years (European Commission, 2018b). However, pension rises have lagged behind the high wage increases seen in recent years given that indexation is based on 50% of the increase in the consumer price index and 50% of insurable income growth. A return to strong wage growth as the economy recovers from COVID-19 would further increase the gap between the incomes of the most vulnerable pensioners and the average worker. The EU ageing baseline projections assume that the benefit ratio will decrease over time, i.e. that pensions will fall relative to the average wage. However, given that a large share of the population faces low incomes on retiring, pressure is likely to mount to increase the living standards of the growing older population.

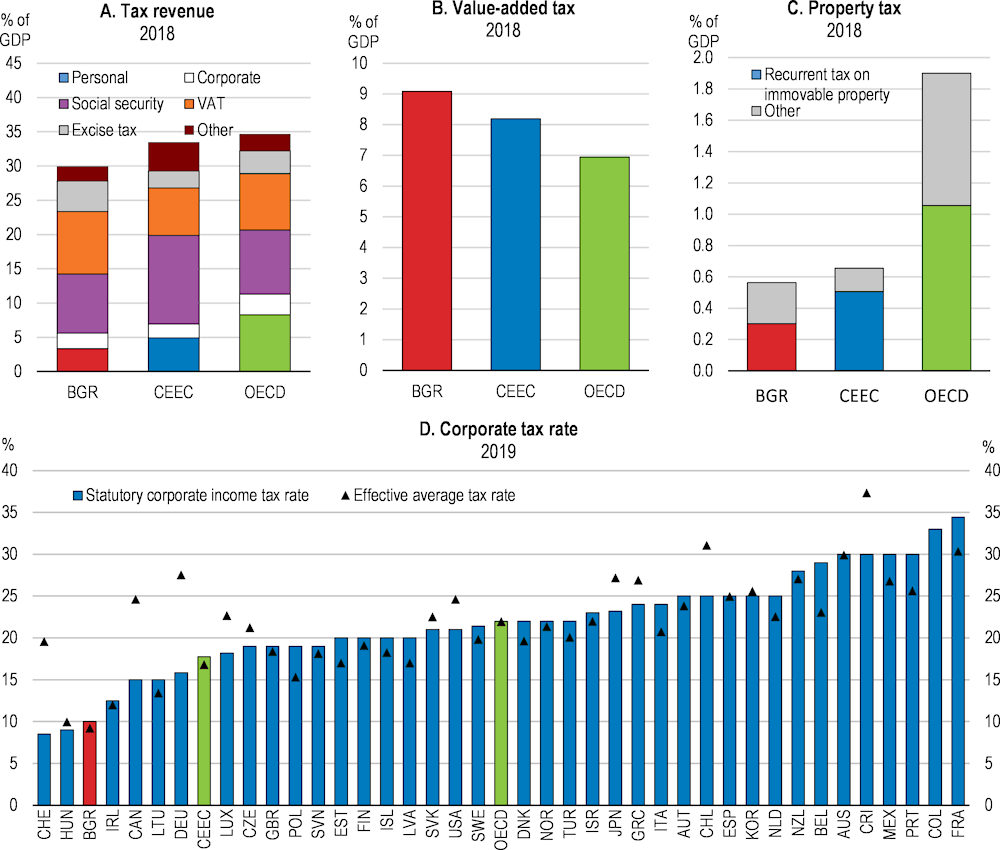

Box 1.4. Composition of government revenues

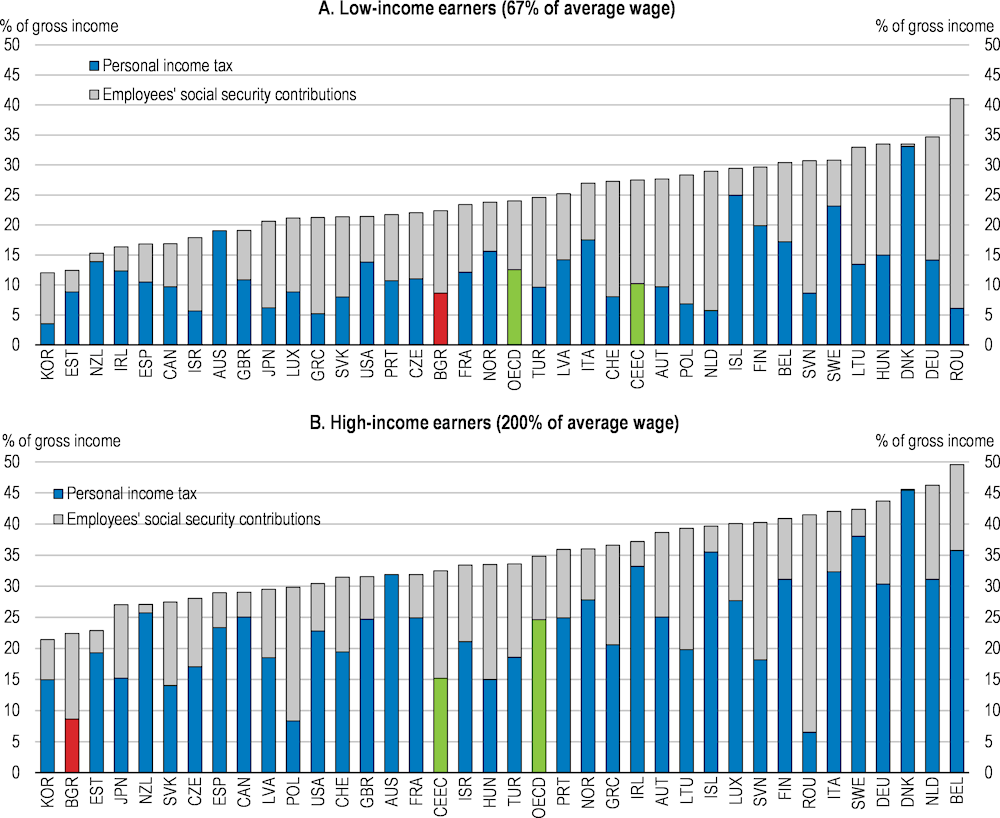

Tax pressure is relatively low compared to the OECD and EU, with a tax-to-GDP ratio of 30% in 2018 (Figure 1.9, Panel A). Indirect taxes such as VAT and excise taxes contribute more to tax revenues than on average in the OECD (Figure 1.9, Panels A and B). Taxes from income and property are relatively low (Figure 1.9, Panels A and C). A flat tax of 10% on personal and corporate incomes was put in place in 2008. It puts Bulgaria among the most competitive corporate tax regimes (Figure 1.9, Panel D), but results in much lower corporate tax revenues that on average in the OECD. The flat tax combined with having no personal allowances available to reduce taxable income results in a lack of progressivity in income taxes. In its Medium-term Budget Framework, the government has committed to continuing to reduce tax fraud and evasion, an important priority given growing spending needs.

Figure 1.9. Revenues are low and rely on indirect taxation

Note: CEEC is an unweighted average of the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia.

Source: OECD, Global Revenue Statistics and Corporate Tax Statistics databases.

The currency board is a cornerstone for macroeconomic stability

A currency board arrangement, put in place in July 1997 in the aftermath of the banking crisis and period of very high inflation, fixes the national currency to the euro. Backed by prudent fiscal policy and low public debt, it has endured several crisis and proved to be an important anchor for macroeconomic stability. The Bulgarian lev was included in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II) in July 2020 and the ECB and the Bulgarian National Bank have established a close cooperation over bank supervision. By mutual agreement, the finance ministers of the euro area countries, the President of the ECB, and the finance ministers and central bank governors of Denmark, Bulgaria and Croatia decided to include the Bulgarian lev in ERM II. The Bulgarian National Bank unilaterally commits to keep in place its currency board arrangement without imposing any additional obligations on the ECB or the other participants in the mechanism.

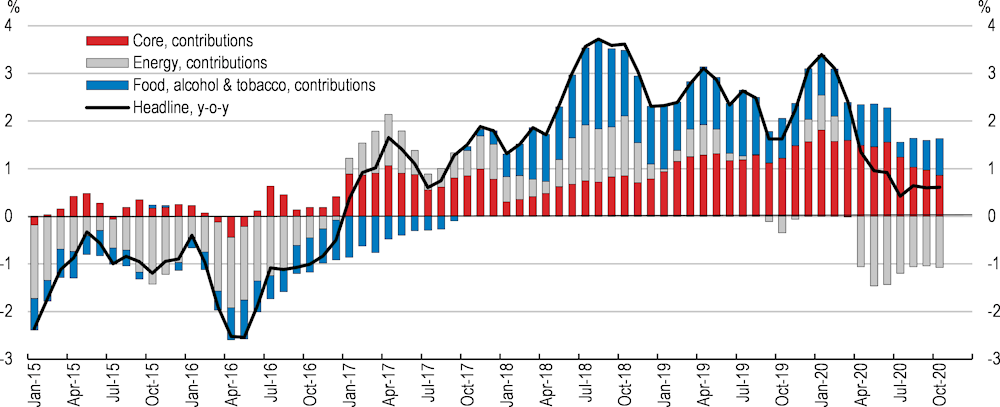

Prior to COVID-19, inflationary pressures had emerged from strong domestic demand driven by high real wage growth, and hikes in the prices of food and services. Price dynamics for inflation have been volatile in recent years driven by energy and food prices (Figure 1.10). Core inflation has tended to be below headline values in recent years, even though the gap between the two measures was narrowing as energy prices fell. Annual inflation has moderated from 3.4% at the beginning of 2020 to 0.6% in October 2020, driven not only by the fall in international energy prices, but also by the slowdown in core inflation and the cut in regulated natural gas and heating prices.

Figure 1.10. Inflation was stabilising prior to the COVID-19 shock

Harmonised index of consumer price

The recovery from COVID-19 is likely to bring renewed price pressures resulting in higher inflation than the euro area given that income per capita and price levels are substantially lower in Bulgaria. The monetary inflexibility implied by the currency board will require continued prudent fiscal and sound macro prudential policies. To avoid the accumulation of excessive price pressures and macroeconomic imbalances, appropriate structural reforms will be needed to boost productivity convergence (Chapter 2) and ensure wage growth is matched by productivity improvements, particularly for non-tradable goods.

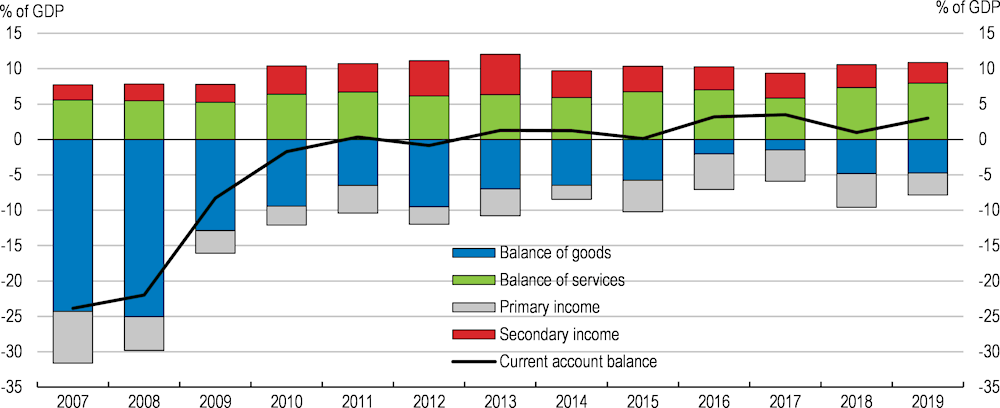

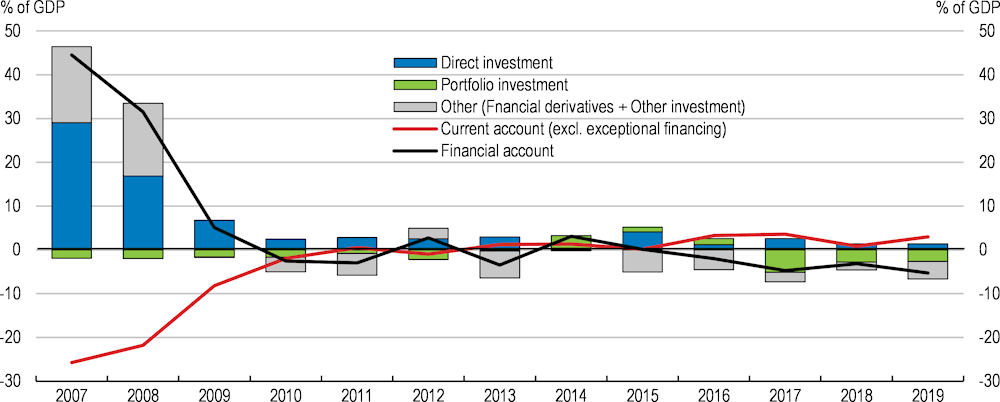

The economy has been running current account surpluses for nearly ten years. The current and capital account position of the country has substantially improved in the last decade. A reduction in the trade deficit helped drive current account surpluses based on export-led growth and constrained import demand in the recovery year following the 2008 global financial crisis. Current account surpluses of 1% and 3% of GDP were recorded in 2018 and 2019, respectively (Figure 1.11). At the same time, there has been a large drop in net financial inflows (Figure 1.12). Net direct investment inflows have fallen significantly from 2007, when there were substantial foreign investment inflows for real estate, financial and insurance services. The external debt of the banking sector has fallen since 2007/2008 contributing to a large drop in gross external debt to 58% of GDP in 2019.

Figure 1.11. Current account surpluses have been driven by a reduction in the trade deficit

Figure 1.12. Net international investment has fallen substantially

Bulgaria is in a good position to make the most of the opportunities offered by joining the euro zone. The country has maintained through its currency board a fixed exchange rate, initially to the German mark, and then the euro, since 1997. There has been no deviation from the fixed exchange rate. In this period, the monetary arrangement survived a series of domestic and external shocks, underpinned by prudent fiscal policy and declining public debt. It approaches euro zone entry with low debt and a record of containing fiscal deficits, putting the country in a stronger position than many former entrants. Bulgaria had to deal with a surge in unsustainable foreign inflows, similar to that experienced by some euro zone countries, prior to the 2008 global financial crisis. In the wake of this and the 2014 bank failure, much attention has been put on strengthening macroprudential norms and financial sector supervision. The long-term interest rate differential with the euro has fallen already to zero and the country is unlikely to face a flood of speculative funds following euro accession.

The financial sector has been fortified, but non-performing loans remain high

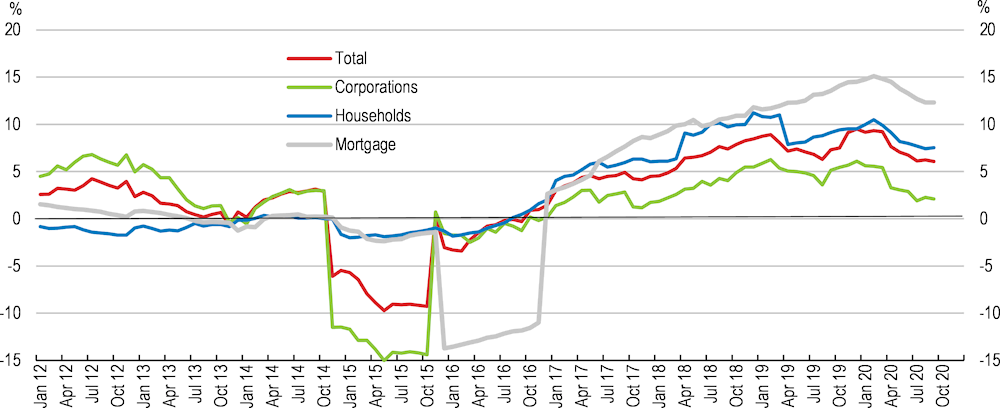

Banks dominate the financial system, with the capital market limited in size and non-bank players representing a relatively small share of activity. The five largest banks are responsible for 62% of banking system assets. Market shares are 72% for EU bank subsidiaries, 22% for domestic banks, and 4% for EU bank branches. Exposure of the financial system to external financing is low: the loan-to-deposit ratio stood at 73% at end-March 2020 and financing is covered by residential deposits, which made up 93% of banking system deposits at end-2019. Private sector credit had been growing prior to the COVID-19 shock following what was a period of muted activity since the 2008 global financial crisis and the one-off negative shock to credit that occurred following the collapse of the Corporate Commercial Bank AD (KTB) in 2014 (Figure 1.13).

Figure 1.13. Credit growth had picked up

Credit to non-MFIs, year-on-year percentage change

The authorities consider that the banking sector entered the COVID-19 pandemic well-capitalised, with adequate liquidity and increased profitability. Regulatory tier 1 capital is relatively high compared to the OECD average (Figure 1.14, Panel A). The overall leverage ratio is above the OECD average (Figure 1.14, Panel B). Bank profitability has increased, and the return on assets (Figure 1.14, Panel C) and equity (Figure 1.14, Panel D) is higher than on average for the OECD. Non-performing loans have fallen over time (Figure 1.14, Panel E), but remain well above OECD and CEEC levels (Figure 1.14, Panel F).

Figure 1.14. Financial sector health had improved

2019 or latest available year

Note: CEEC is the unweighted average of the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia, except in panel B where Hungary data is unavailable.

Source: IMF, Financial Soundness Indicators database.

Prior to the pandemic, measures had been put in place to further improve capital adequacy and asset quality of the banking sectors. The ECB carried out an asset quality review and stress test of the six banks based on a point-in-time assessment as of end-2018, publishing the results in 2019 (European Central Bank, 2019). Four of the assessed banks were found not to have any capital shortfalls. Two domestically-owned banks had capital needs, as revealed by the adverse scenario in the stress tests, and as a result were further recapitalised in 2020.

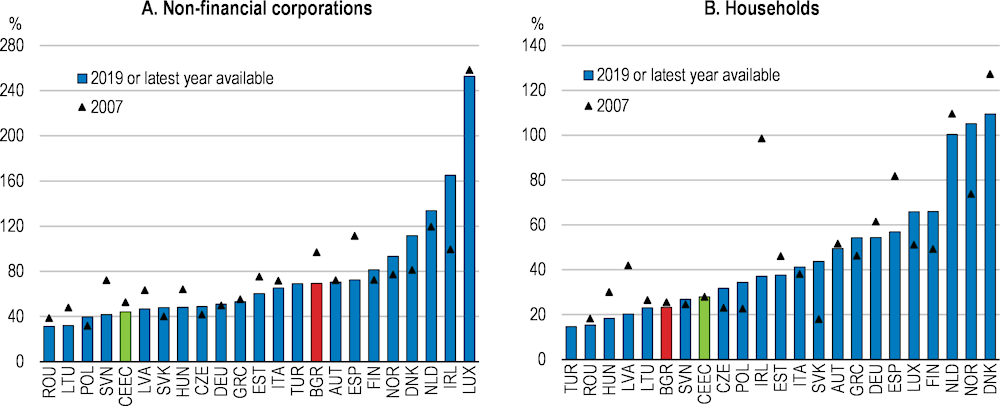

Credit risk from loans to households is likely to be lower than that from non-financial corporations. Non-financial corporation debt to GDP had fallen to just above the EU average (Figure 1.15 Panel A). Service sectors impacted by COVID-19 are among those with the lowest liquidity buffers, namely real estate activities and accommodation and food service activities that have loan to deposit ratios of 313% and 210%, respectively (Bulgarian National Bank, 2020). Indicators at the sectoral level only give a general indication of the level of indebtedness and liquidity position of firms due to the heterogeneity of individual firms within the sectors. Faced with a decline in activity, firms in the sectors most impacted by COVID-19 may begin to feel pressure with making loan repayments when the current debt moratorium runs out. Household debt is one of the lowest in the EU at 23% of GDP and mostly comprises bank loans (Figure 1.15, Panel B). Households’ bank deposits have grown over December 2019-July 2020 as in most EU countries, but the increase is on the lower end (OECD, 2020b). Non-financial corporations have not experienced the rise in bank deposits seen in many other EU countries (OECD, 2020b). Government support for households and the business sector diminishes default risks as long as measures remain in place.

Figure 1.15. Household indebtedness is low, while non-financial corporation debt had been falling

Debt in per cent of GDP

Note: Consolidated data. Panel B also includes non-profit institutions serving households.

Source: Eurostat (online code nasa_10_f_bs).

The COVID-19 crisis presents the banking system with the challenge of keeping credit flowing, often with the support of government programmes to the corporate sector, while managing rising risks. The view of the Bulgarian authorities is that the banking sector is facing these challenges in good condition, with a solid capital and liquidity position allowing the management of the rising risks. At the onset of the COVID-19 confinement, the Bulgarian National Bank took measures aimed at preserving the stability of the banking system and strengthening its flexibility. These include an increase in banking system liquidity by EUR 3.6 billion (BGN 7 billion) through a reduction in foreign exposure of commercial banks, full capitalisation of profits in the banking system, the cancellation of the increase in the counter cyclical capital buffer planned for 2020 and 2021 (totalling 0.6% of 2019 GDP). Depending on how the COVID-19 crisis unfolds, further measures may have to be considered if there is a rise in non-performing loans. The ECB and the Bulgarian National Bank put in place a precautionary swap line of EUR 2 billion to provide euro liquidity in April. A moratorium on loan repayments for debtors hit by COVID-19 has been put in place. The scheme is set to run until March 2021 allowing borrowers to submit loan deferral requests until end-September 2020. Over 80 000 loans totalling about EUR 3 billion (BGN 6 billion) benefitted from the programme in the first three months of its implementation (Association of Banks in Bulgaria, 2020). Additional firm and household credit support has been put in place, using commercial banks as intermediaries, but with the Bulgarian Development Bank providing 80% guarantees in the case of firms and 100% guarantees for household credit (Box 1.1).

Under the action plan to prepare for ERM II, the authorities have carried out impressive reforms to strengthen financial sector supervision and the macroprudential framework, and to improve the legal frameworks for the governance of state-owned enterprises and anti-money laundering. The government has identified gaps in the insolvency framework and put together a roadmap to address them and revise legislation (Chapter 2). Achieving membership of the European Banking Union should reinforce the resilience of the financial system given that a large share of foreign-owned subsidiaries come from Banking Union countries and that being part of the Banking Union supervisory and resolution arrangements should assist to maintain confidence in the financial system. The ECB will be responsible for the direct supervision of the significant financial institutions, oversight of less significant institutions and procedures for all supervised entities from October 2020.

Strengthening the recovery

Making the most of the export sector

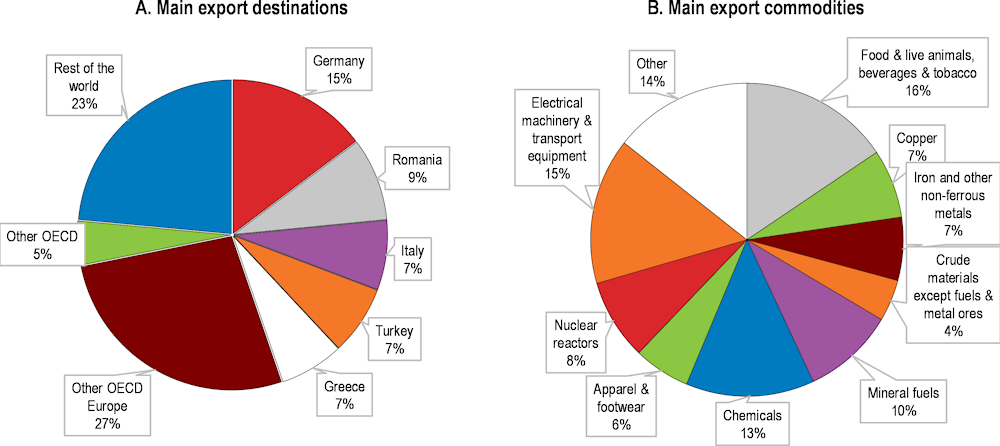

A small, highly open economy, the degree of robustness of external demand will be an important driver of the speed of the recovery from COVID-19. Trade grew strongly from the early 2000s through EU membership and beyond: exports and imports of goods and services increased from 78% to 124% of GDP over 2000-2019. However, at 64% of GDP, exports of goods and services remain lower than for many faster converging CEEC peers. About two-thirds of exported goods are destined for the EU with Germany, Romania, Italy, Turkey and Greece being the most important markets (Figure 1.16, Panel B). Services make up around a quarter of exports, with about 38% of total service exports consisting of travel services – hard hit by the current pandemic – and a fifth by transportation and storage services. Business services have become increasingly important, including a dynamic computer and information services sector. Goods exports rely on a high share of primary exports, including copper, iron and other metals, and petroleum products, and a lower share of higher value-added goods (Figure 1.16, Panel B). Boosting growth of the more dynamic exports sectors, not only in services activities, but also in higher value-added manufacturing (see Chapter 3 on the agricultural sector), will be important to increase convergence.

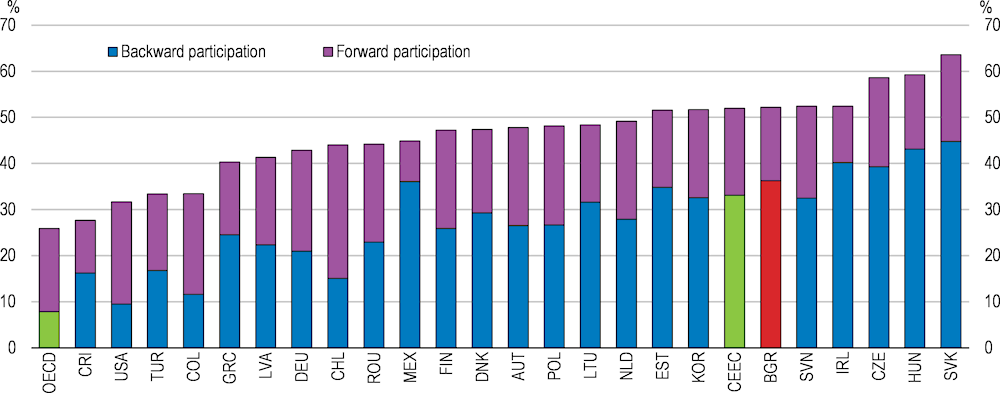

Bulgaria has successfully integrated into regional and global value chains and now faces the challenge of boosting the domestic value added of gross exports generated through this activity. Participation in global value chains is at a similar level to CEEC countries. The importing of foreign inputs to produce exported goods and services, i.e. “backward participation”, features more strongly than the exportation of domestically-produced inputs to foreign downstream producers (“forward participation”) (Figure 1.17). There are some niche fast-growing service sectors involved in global value chain activities, but they far from dominate. In general, this activity results in low value added content as the country participates in highly-fragmented global value chains, frequently involving processing and assembly of foreign inputs in manufacturing activities like the refinement of petroleum products, production of basic metals and machinery, electrical and transport machinery (Ivanova and Ivanov, 2017). Local subsidiaries of multinationals dominate in the export of inputs to producers abroad, with a low share for domestic firms participating in exports (Taglioni and Winkler, 2016).

Figure 1.16. Exports by destination and commodity

Share of total exports, 2019

Figure 1.17. Integration in global value chains is high

Percentage share in total gross exports, 2015

Note: Forward participation is the domestic value added in foreign exports as a share of gross exports, and backward participation is the foreign value added share in gross exports.

Source: OECD, Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database.

While increased global value chain integration has been correlated with value-added gains (Taglioni and Winkler, 2016), the contribution to convergence would be increased by moving up the value chain and increasing the spillovers to domestic firms. Boosting the domestic value-added from exports and further increasing global value chain insertion involves putting in place complementary business environment reforms. Kummritz et al. (2017) point out the economy-wide reforms that would assist Bulgaria in maximising benefits from global insertion. These encompass reforms from increasing innovation to improving logistics performance and reducing red tape to enhancing skills (Chapter 2). There is evidence from Ireland that supplying inputs to multinationals can be an important pathway for knowledge and technology transfers. Domestic firm productivity is negatively associated with purchases from foreign firms for downstream activities (Di Ubaldo et al., 2018). R&D investment is found to be an important channel for productivity spillovers. This suggests that Bulgaria should focus innovation support on domestic firms engaging in the supply of inputs to multinational/foreign firms rather than companies that concentrate on processing and assembling foreign inputs.

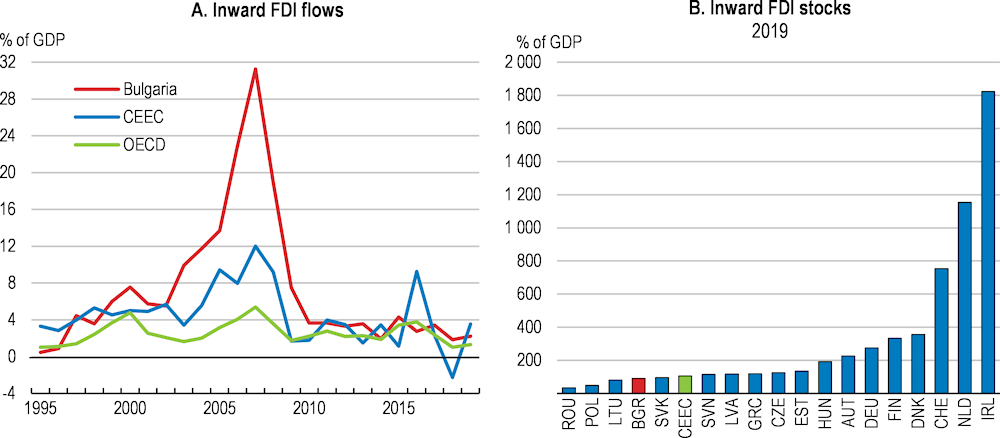

Foreign direct investment had a big role in expanding the exports sector, but spillovers to domestic enterprises could be increased. Continuing to attract foreign investment that is directed at increasing value-added in the manufacturing and services sector will be important to increase capital investment in firms and to contribute to raise business sector productivity (IMF, 2019a). Foreign direct investment averaged about 3.1% of GDP over 2012-2018, similar to the levels seen on average in CEEC and OECD countries (Figure 1.18, Panels A and B). However, the nature of foreign investment has been very different to that seen in many CEEC countries. Rather than being destined to a large degree for the manufacturing sector, the stock of foreign direct investment has been concentrated in real estate and, financial and insurance activities sectors. These non-manufacturing sector investment surged in pre-2008 global financial crisis years, driving up overall investment but abruptly falling after 2007. There has been some positive shift in the structure of FDI flows towards more trade-related sectors, as these inflows proved more resilient after 2008. The share of investment in manufacturing and other tradeable sectors has increased in recent years.

Figure 1.18. Foreign direct investment is close to the CEEC average

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators database; Eurostat (online code bop_iip6_q).

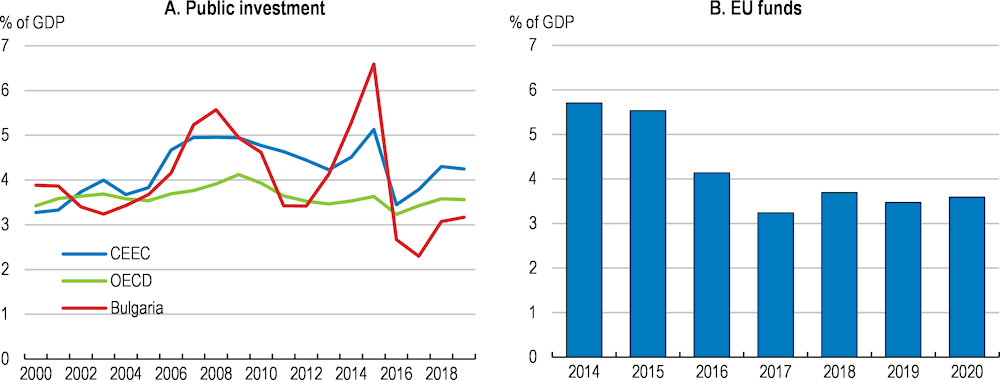

Public investment should be increased

Public investment has been volatile and has fallen below CEEC peers. Protecting public investment during the COVID-19 downturn will be important for the recovery and to improve key housing and transport infrastructure and innovation to increase potential growth. Capital spending has been found to have the largest multiplier of any government spending component for Bulgaria (Muir and Weber, 2013). In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, public investment fell and in recent years has remained well-below pre-crisis levels (Figure 1.19, Panel B). Troughs and peaks in public investment can be largely explained by the EU funding cycle, with strong peaks at the beginning of the 2014-2020 programming period (Figure 1.19, Panel B). Bulgaria is one of the largest beneficiaries of EU support (European Commission, 2020b). European Union funding is to continue to be high with strong investments expected at the beginning of the next programming period in 2021 and substantial resources to come from the European Union Recovery and Resilience Facility (about 10% of pre-crisis GDP). It will be important to strengthen public investment management to ensure an effective and rapid use of the large available European Union resources.

Figure 1.19. Public investment has fallen below CEEC peers

Note: Forecast for the 2020 data in panel B.

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook database; Ministry of Finance, Bulgaria.

The economy has investment gaps in infrastructure, the housing stock and innovation that will need to be closed to support greater economic convergence. Transport infrastructure needs to be improved to allow the country to have better connectivity with its neighbours, to increase its attractiveness as a transit zone and to better connect its regions (Chapter 3). The road and rail network require substantial investment, and there remain gaps in the broadband network in some regions. Limited access to affordable housing creates a barrier to mobility of workers within the country. The housing stock also is of poor quality and suffers from low energy efficiency. Investment also would need to focus on continued support for the growing digital economy, including improving access in lagging regions, assisting further digitalisation for firms and the government, and developing digital skills. Innovation in the economy is low, and publicly-financed research and innovation is underfunded and its efficiency could be improved (Chapter 2). A large-scale public investment programme in these areas would be timely to boost the recovery from COVID-19 and potential growth.

Removing barriers to competition

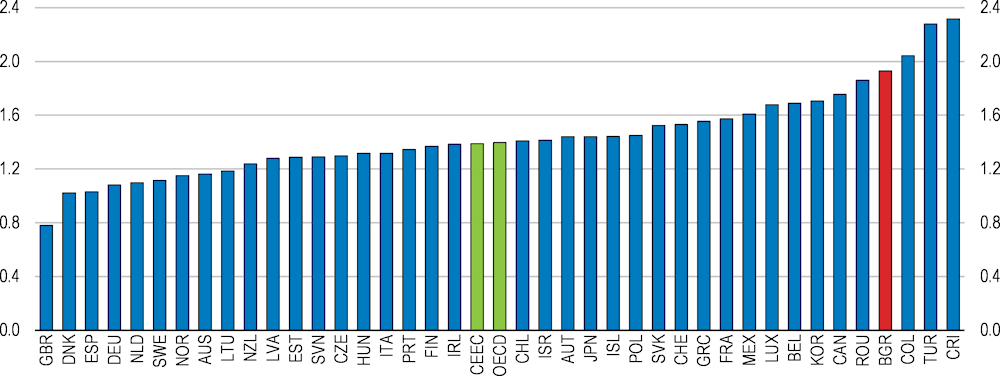

Reducing the high regulatory barriers to competition could give a substantial boost to productivity by supporting a more efficient allocation of resources in the economy. The OECD’s product market regulation indicators show that the regulatory barriers to competition in Bulgaria are higher than for all OECD countries, with the exception of Colombia and Turkey, based on the economy-wide 2018 product market regulation measure (Figure 1.20) (Chapter 2). This measure examines the alignment of a country’s regulatory framework with international best practice. There are high administrative requirements and an onerous licensing regime for new businesses, which if eased would encourage the creation of new businesses and the entry of competitors into new business areas. There is extensive public ownership of large operators in key network sectors, with incumbent companies completely owned by the state in sectors such as electricity generation, gas import and retail supply, and rail transport. The large presence of the state in these sectors, even though they are open to competition, can generate distortions and affect the incentives for private firms to enter and expand their presence in the sector. The barriers to entering legal professions (lawyers and notaries) are higher than in any OECD or CEEC country.

Figure 1.20. Barriers to competition are high

Overall Product Market Regulation indicator, index scale of 0-6 from least to most restrictive, 2018

Note: Information refers to laws and regulation in force on 1 January 2019. The OECD average does not include the United States.

Source: OECD, 2018 Product Market Regulation Indicators database.

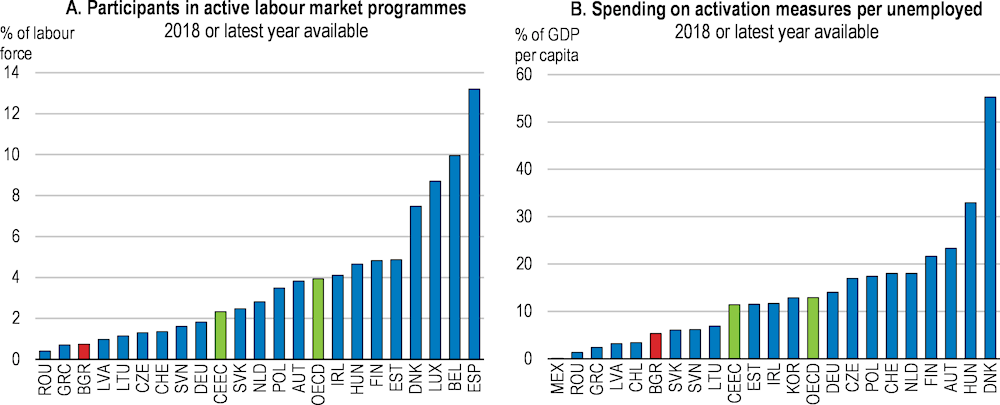

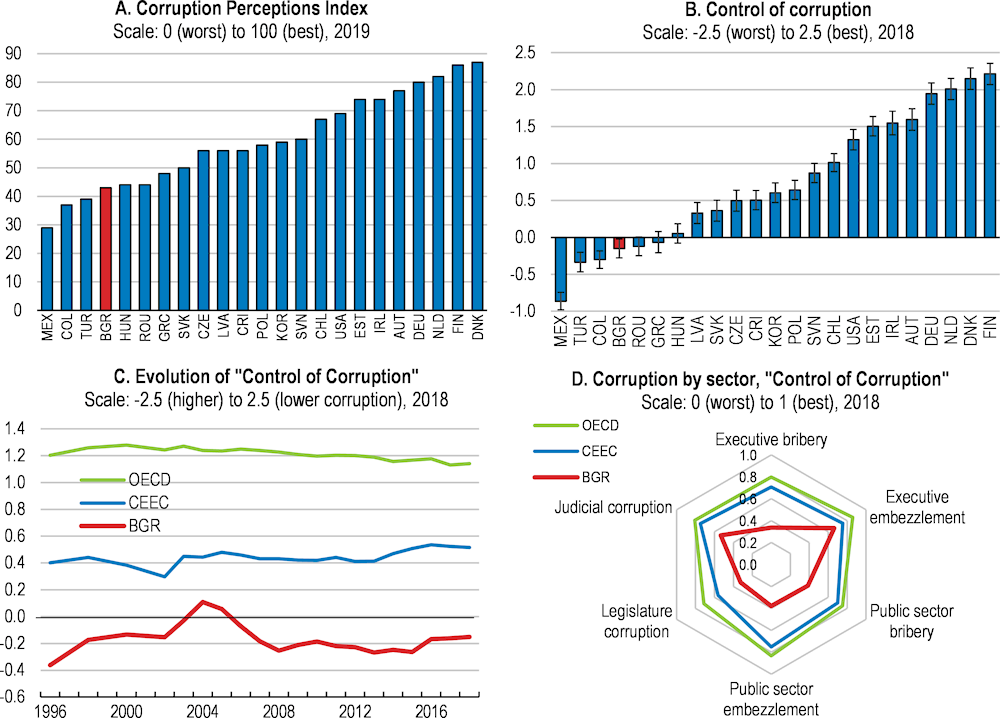

Increased public investment as well as structural reforms to improve the business environment and governance have a large potential to boost incomes. If the main reforms presented in this Assessment are adopted, the boost to GDP per capita would be substantial and with limited fiscal impact (Box 1.5).

Box 1.5. Quantifying the impact of selected policy recommendations

The following estimates roughly quantify the growth and fiscal impact of selected structural reform recommendations. The fiscal estimates give a costing for longer-term structural reforms that are likely to be delayed until the post-crisis recovery period. The estimated fiscal effects include only the direct impact and exclude behavioural responses that occur due to a policy change.

Table 1.3. Illustrative GDP impact of recommended reforms

Difference in GDP per capita level, %

|

Measure |

Description |

Effect after 10 years |

|---|---|---|

|

Business environment |

||

|

Lower regulatory barriers (PMR) |

Closing half of the gap to the OECD average |

2.3 |

|

Increased spending on public investment and innovation |

Move to CEEC average |

0.5 |

|

Improvement of public integrity and institutional quality |

Closing half of the gap to the OECD average for the control of corruption indicator |

4.7 |

|

Labour market inclusion |

||

|

Increased spending on active labour market policies |

Closing half of the gap to the OECD average |

1.0 |

|

Increased female legal retirement age |

Acceleration of equalising the legal retirement age of women and men (+0.5 year in average age) |

0.5 |

Note: Model simulations based on the framework of Égert and Gal (2017). Scenarios depict the effect on the level of GDP per capita as compared to a baseline scenario with no policy changes. Not all recommended reforms, including some included in the fiscal quantification, can be quantified based on available cross-country evidence.

Source: OECD staff estimates.

Table 1.4. Illustrative fiscal impact of post-recovery recommended reforms

Annual fiscal balance effect of selected reforms, % of GDP

|

Measure |

Description |

Effect after 10 years |

|---|---|---|

|

Deficit-increasing measures |

2.7 |

|

|

Business environment |

||

|

Increased spending on public investment and innovation |

Move to CEEC average |

0.6 |

|

Strengthened capacity for insolvency and rehabilitation framework |

0.1 |

|

|

Increased resources for integrity and anti-corruption institutions |

0.1 |

|

|

Labour market inclusion and social reforms |

||

|

Provide universal access for 4-year olds to early childhood education |

0.2 |

|

|

Increased spending on active labour market policies |

Closing half of the gap to the OECD average |

0.2 |

|

Increased spending on social safety net |

Move to CEEC average |

0.5 |

|

Increased spending on health and long-term care |

Closing half of the gap to the OECD average |

1.0 |

|

Deficit-reducing measures |

2.0-2.1 |

|

|

Tax and subsidy reforms |

||

|

Improved tax compliance and higher taxation after recovery |

Move towards CEEC average |

1.5 |

|

Phasing out subsidies for fossil fuels |

0.3 |

|

|

Labour market inclusion |

||

|

Increased female legal retirement age |

0.2-0.3 |

Note: Estimations for selected reforms showing only direct budget impacts.

Source: OECD calculations.

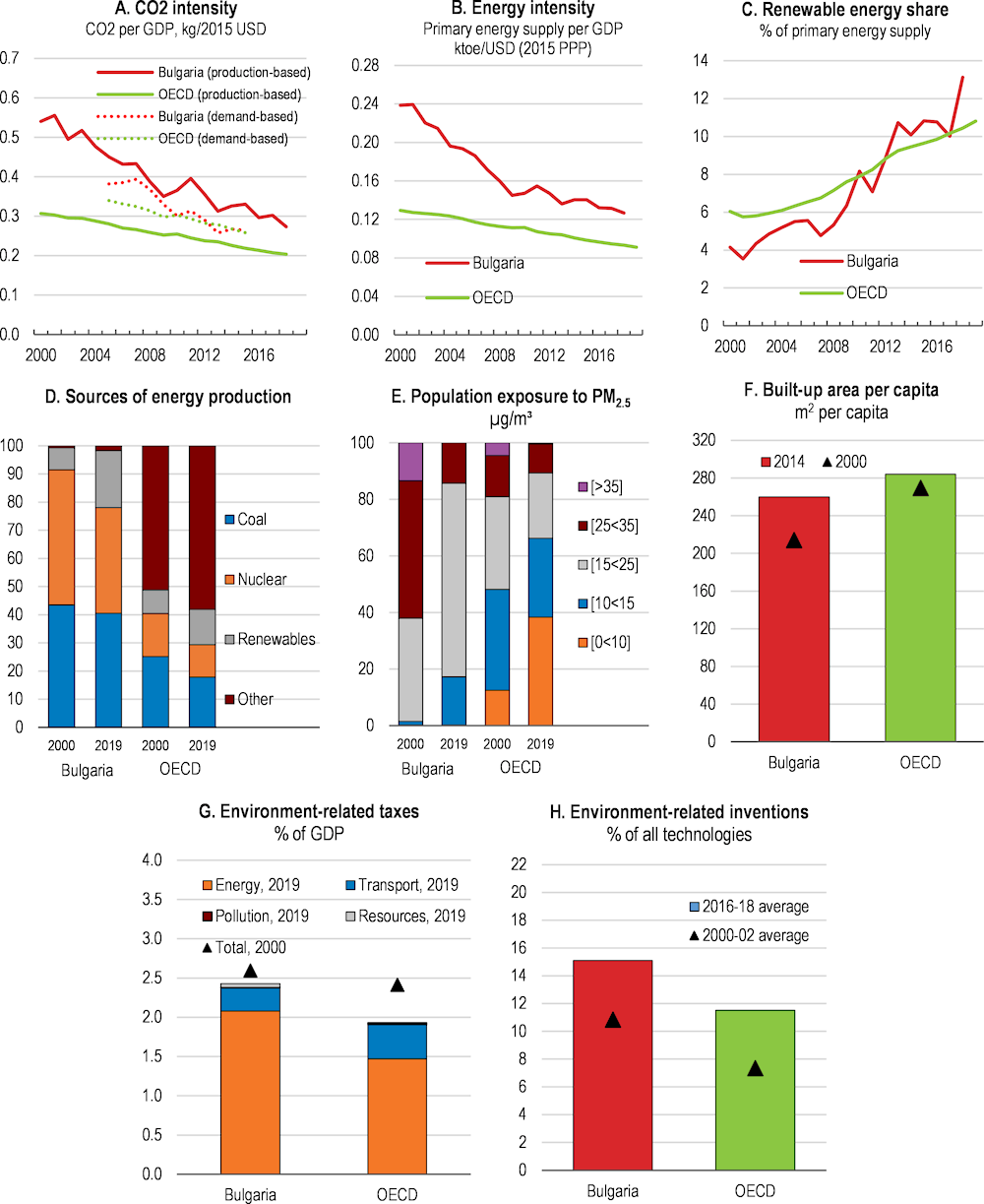

Decarbonising the economy

Environmental performance has improved, but the economy remains more carbon- and energy-intensive than most OECD countries (Figure 1.21). Renewable energy from hydro, wind and solar increased substantially upon EU accession, but since 2013 expansion has almost stopped. By contrast, policy initiatives have accelerated biofuels supply in recent years and contributed to bring the share of renewables in energy supply above the OECD average (Panel C). Nonetheless, coal continues to account for almost half of energy production and generates large greenhouse gas emissions. The coal-fired power plants are also an important source of poor air quality, along with high use of solid fuels for heating and the transport sector. Bulgaria has more pollution-related deaths than any OECD country with 827 deaths per 1 million inhabitants in 2017, well above the OECD average of 326.

As an EU Member State, Bulgaria’s emissions from the energy sector is regulated through the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS). For the sectors outside ETS, Bulgaria has a national 2030 target of keeping emissions no higher than their 2005 level (0% reduction). According to the national energy and climate plan for 2021-2030 submitted to the EU (BME and BMEW, 2020), the economy is on track to reach its 2030 emission and energy targets. However, the new ambitious EU emission target agreed in December 2020 will be a serious challenge to Bulgaria’s long-term strategy that does not yet include a phase-out plan for coal.

The recovery from COVID-19 presents an opportunity to accelerate the transition to low-carbon energy sources (OECD, 2020c) and tap into abundant financial resources for green infrastructure investments, including EU Green Deal funds. The transition will be a challenge as Bulgaria accounts for 7% of total EU coal production. The mining of coal and lignite sector directly employed 15 700 people in 2019 (LFS, Eurostat), representing less than 0.5% of the labour force but strongly concentrated in two regions (Stara Zagora and Kyustendil). Measures will thus be needed for reskilling and reallocating these workers (JRC, 2018; SE3Tnet, 2020). Although Bulgaria intends to continue using coal, it has requested to participate in the EU programme for Coal Regions in Transition, which is welcome.

Coal-fired power plants are already becoming unprofitable (European Commission, 2020b; SE3Tnet, 2020) and renewables are now often more cost-competitive in advanced countries (IEA, 2019). Market forces and a rise in the price of ETS allowances will thus eventually force Bulgaria’s coal industry to close (SE3Tnet, 2020). It already benefits from substantial state-aid, which should be removed gradually to not obstruct decarbonisation. As a low-income EU Member State, Bulgaria is allowed to distribute free ETS allowances to existing power plants under the condition that similar amounts are invested in modernising the electricity sector (54 million allowances were allocated during 2013-2020, BME and BMEW, 2020). Ten countries will maintain this right until 2030, but only Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania have decided to use it. Bulgaria also supports coal power plants through payments for cold reserve capacity for times of peak demand (rarely activated) and by preferential electricity prices for plants producing district heating as well (EU-approved state-aid scheme for efficient cogeneration). Removing all this public support would free estimated EUR 450 million annually (0.7% of GDP), which could be used to invest in renewables and for compensating consumers for temporarily higher electricity prices during the transition (SE3Tnet, 2020).

Figure 1.21. Energy intensity and reliance on coal remain high

Source: OECD (2020), OECD Environment Statistics database (Green Growth Indicators; Patents); OECD National Accounts database; IEA (2020), IEA Energy Prices and Taxes database; World Bank, World Development Indicators database.

Cost-benefit analysis should be applied to plan the phase-out of support, taking into account reduced energy security. Bulgaria is currently a large net exporter of electricity and maximum use of its (lignite) coal reserves would ensure energy supply for many years. At the same time, the government plans to develop its nuclear power programme with the construction of two new units (BME and BMEW, 2020) that would help ensure energy security and achieve cost-efficient decarbonisation (NEA, 2020). The use of a new generation of nuclear installations is also being considered, which is welcome since this would improve security of energy supplies. The two operating reactors are around 30 years old, but an upgrade and extension of operating lifetime to 60 years were completed in 2019. Having institutions and procedures in place to ensure the highest safety standards and vigilance is vital, including e.g. regular risk assessment of seismic hazards and measures to secure a high safety culture. In this respect, Bulgaria will benefit from best practice sharing by joining the Nuclear Energy Agency from January 2021.

Reducing energy demand through efficiency improvements would also alleviate decarbonisation. The potential to improve energy efficiency is huge and stronger action could deliver large cost-savings in addition to the environmental gains. Large subsidies for energy renovation has helped to improve efficiency in residential buildings, but targeting to low-income households could be improved (Chapter 3). The government should also step up the use of information campaigns to inform households about the benefits of energy saving investments as a means to improve efficiency. Although the tax revenue from environmental taxes is above the OECD average, it mainly reflects the high energy consumption relative to GDP. In fact, the implicit tax rate on energy use (the energy tax revenue relative to energy consumption) was the lowest in the EU in 2018. Using fiscal incentives, notably through well-designed energy taxes, could thus be considered to enhance efficiency when the economy is well into a post-COVID-19 recovery.

Aligning pricing of greenhouse gas emissions from sectors outside the EU ETS, notably buildings, transport, agriculture and waste, should also be a priority to achieve cost-efficient decarbonisation. Bulgaria overachieved its target for 2020 under the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), but further efforts will be needed to reach the 2030 zero reduction target. Carbon pricing of e.g. transportation and waste is the most efficient way to achieve emission reductions and a surplus under ESR can be traded with other EU countries and generate additional revenue. For instance, vehicle taxes are comparatively low and recycling of municipal waste is lower than in most EU countries, with municipal waste collection fees not based on the amount of waste generation (European Commission, 2020b). Implementation of carbon pricing should be complemented by social measures to protect poorer households.

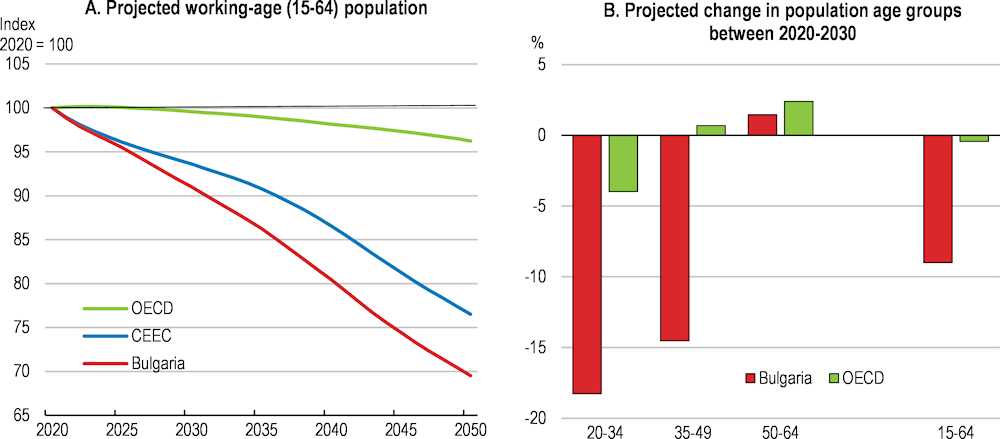

Ageing demographics will influence future growth

The population is ageing and shrinking rapidly. After losing more than one fifth of its population since the late 1980s due to high emigration and declining fertility, Bulgaria is set to see its population fall by further 30% by 2060 – the highest population decrease in the world according to the latest UN Population Division projections. The ageing and shrinking of the population is due to high emigration and a fall in fertility leaving the age structure increasingly top heavy compared to OECD countries. The working-age population (aged 15 to 64) is set to decline by one fifth in the next 20 years. The decline already has begun (Figure 1.22, Panel A) and the workforce will become older as younger age groups shrink dramatically in the next decade (Figure 1.22, Panel B).

Figure 1.22. The working-age population is shrinking and ageing quickly

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019), World Population Prospects 2019, Online Edition. Rev. 1.

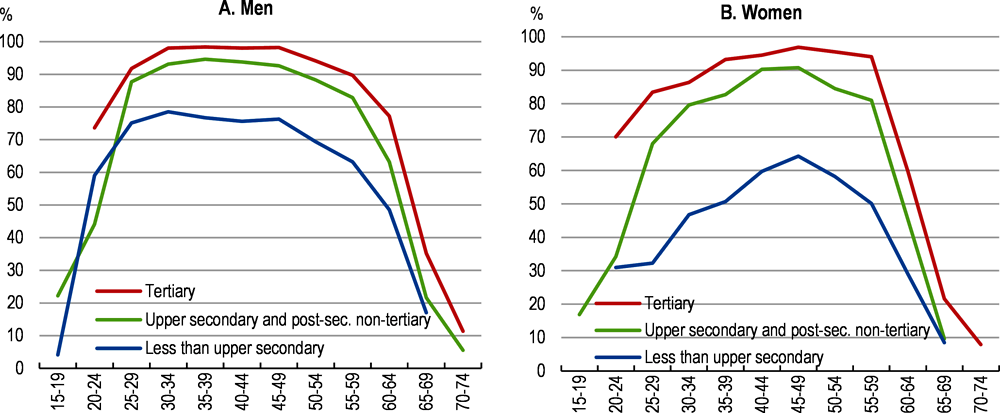

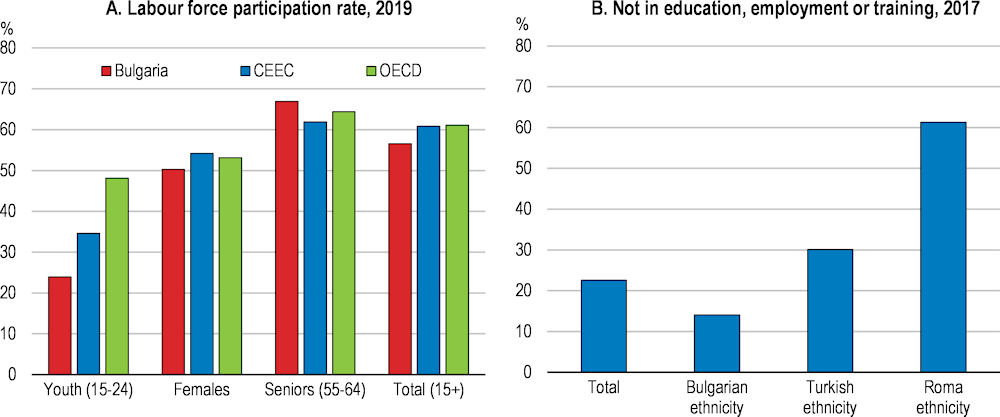

An economy facing such a stark ageing and shrinking of the workforce needs to maximise the population’s benefits from education and training throughout the lifecycle from early childhood education onwards (Chapter 2). Participation in lifelong learning is low, which is of concern for productivity given the shrinking and ageing workforce. On-the-job and formal training can stop the erosion of skills over the lifecycle (OECD, 2017a) and prepares workers for changing skills needs. The education level achieved early in life can determine whether you work more and longer (Figure 1.23).

Figure 1.23. Higher educated people work more and longer

Labour force participation rate by gender, age and educational attainment, 2019

Rising wages have contributed towards a substantial rise in participation in recent years, especially among older age groups. Nevertheless, accelerating the closure of the three-year gap in statutory retirement ages for men and women would not only bolster public finances, but also help to boost long-term growth.

Supporting the continued return of Bulgarians from abroad and attracting skilled immigrants also provides an opportunity to alleviate skill shortages. Emigration has slowed from the high rates seen in the 1990s to the early 2000s and there are a growing number of Bulgarians returning to the country as economic opportunities have improved. With just over 13% of Bulgarian immigrants in OECD countries having tertiary education (ISCED 5 and 6) (OECD, Migration Statistics database), Bulgarians abroad are an important asset for the country (Figure 1.24). Policies should be deepened to attract and smooth the transition of return migrants into the labour market.

Figure 1.24. A large proportion of Bulgarian nationals are living abroad

Numbers of Bulgarian nationals living in another EU country

Non-Bulgarian immigrants are few and, according to National Statistical Institute data, just over 13 000 non-EU nationals entered the country in 2019 – a year when there was substantial skills shortages. While progress was made in the 2016 Labour Migration and Labour Mobility Act, further could be done to reduce employment restrictions, the administrative burden for immigrants and employers, and to smooth the accreditation process for vocational and educational qualifications.