Bulgaria has achieved the transition from high economic volatility to a stable economy with a strong performance in recent history of weathering external and domestic shocks. However, convergence to average EU incomes has been slower than for better-performing Central and Eastern European peers. The focus here is on economy-wide measures that would improve the business environment, stimulate productivity and boost growth. These include decreasing regulatory barriers to firm entry and exit, reducing the cost of red tape, and improving skills and innovation. Increasing competition in the economy is a priority given that regulatory barriers to competition are high compared to the EU and most OECD countries. Ensuring competition principles are entrenched in broader public policies, particularly public procurement, will be important to increase competitive practices in the economy. Improving the performance of SOEs through corporate governance and ownership practices is of critical importance given their large role in providing electricity and transport services. These structural reforms will be particularly important to recover from the COVID-19 shock. A large reallocation of production factors will be needed to move away from industries suffering from long-lasting damages to those that will benefit from strong growth. Such reforms would also help a successful integration in the euro area.

OECD Economic Surveys: Bulgaria 2021

2. Structural reforms to raise productivity and boost convergence

Abstract

Income convergence needs to accelerate

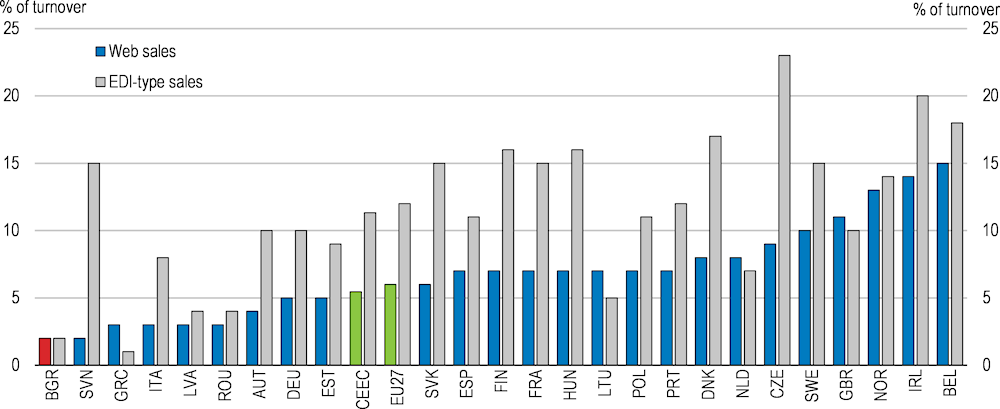

Bulgaria’s strong macroeconomic policy framework has assisted the economy to withstand the COVID-19 crisis. Nevertheless, convergence has been less rapid than for better-performing Central and Eastern European peers (CEEC). The CEEC countries with per capita incomes closest to Bulgaria in 1989—Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania—have grown faster, widening their income gap with Bulgaria (Figure 2.1, Panel A). Bulgaria’s slower convergence is to a large degree due to underperformance in the 1990s, when the country suffered a series of economic contractions, with detrimental impacts on labour productivity (Table 2.1). Performance has been stronger since 2000, with the convergence with OECD countries rising since 2014 (Figure 2.1, Panel B) and further implementation of structural reforms would ensure that this trend will continue.

Figure 2.1. Bulgaria’s income growth has lagged behind other CEEC countries

Real GDP in constant 2017 USD PPP

Note: Panel A shows the real GDP per capita of the CEE countries and Baltic States that had incomes closest to that of Bulgaria in 1989. These were the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia, defined later on as CEEC.

Source: OECD; World Bank, World Development Indicators database.

Bulgaria has carried out an impressive range of reforms in recent years. These include measures to strengthen financial sector supervision and to improve the legal frameworks for State-Owned Enterprises (SOE) governance and anti-money laundering required to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II) and the Banking Union. The Bulgarian lev was included in the ERM II in July 2020, and the European Central Bank and the Bulgarian National Bank have established close cooperation over bank supervision. The simultaneous joining of the ERM II and the Banking Union paves the way for future euro area membership. Current productivity growth rates of around 3% will not be sufficient to deliver rapid convergence with euro area incomes given that Bulgaria has the lowest per capita income in the EU. Still-high real wage differentials with the euro area means that wage growth will need to keep in line with productivity growth to ensure competitiveness and keep down inflation. The large decline in the working-age population that is due to occur increases the possibility that the substantial wage pressures seen in recent years will re-emerge.

Table 2.1. Recent labour productivity growth exceeds the OECD, catching up with CEEC peers

Output per worker growth and its components

|

|

|

Output per worker growth |

Output per hour worked growth |

Average hours worked growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

1995-2019 |

2.3 |

2.5 |

-0.2 |

|

Bulgaria |

1995-2000 |

-0.4 |

0.5 |

-0.8 |

|

|

2000-2007 |

3.9 |

3.7 |

0.1 |

|

|

2010-2019 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

0.0 |

|

|

||||

|

1995-2019 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

-0.2 |

|

|

OECD |

1995-2000 |

2.0 |

2.1 |

-0.1 |

|

|

2000-2007 |

1.4 |

1.8 |

-0.4 |

|

|

2010-2019 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

-0.1 |

|

|

||||

|

1995-2019 |

3.4 |

3.7 |

-0.2 |

|

|

CEEC |

1995-2000 |

4.0 |

3.9 |

0.1 |

|

|

2000-2007 |

4.9 |

5.2 |

-0.3 |

|

2010-2019 |

2.5 |

2.9 |

-0.3 |

Note: CEEC is the average of the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia.

Source: OECD, Productivity database.

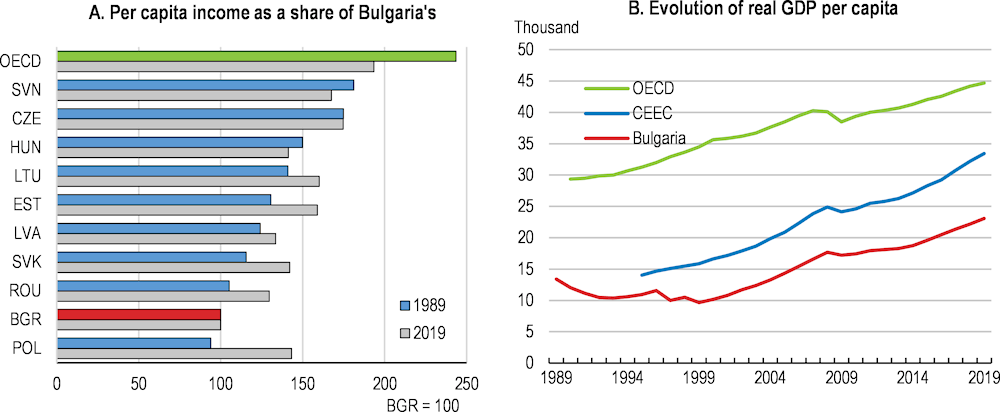

Intangible capital and multifactor productivity need to become more important growth drivers to increase convergence and compensate for the shrinking labour force. The largest contributions to growth in recent years have come from multifactor/total factor productivity growth and capital deepening (Figure 2.2). Multifactor productivity has played less of a role in driving growth than in the fastest converging CEEC peer countries, indicating that growth could be speeded up by larger improvements in the overall efficiency of economy. Capital deepening could strengthen if foreign investment inflows to the manufacturing sector rebounded towards early 2000s highs (Key Policy Insights). Labour quantity has negatively impacted on growth, while the changing composition of labour or quality of the labour force has been positive but of smaller magnitude than several CEEC countries. Intangible capital contributes far too little to growth. This consists of the growth in spending on R&D, software, databases, copyrights, designs, trademarks, and organisation and distribution networks, and has become an increasing driver of productivity growth in OECD countries (Demmou, Stefanescu and Arquie, 2019).

Figure 2.2. Intangible capital needs to be boosted to increase growth

Contributions to GDP growth, average 2010-2017 or latest year available

Source: EU KLEMS database, 2019 release; Stehrer, R., et al. (2019), "Industry level growth and productivity data with special focus on intangible assets", wiiw Statistical Report No. 8.

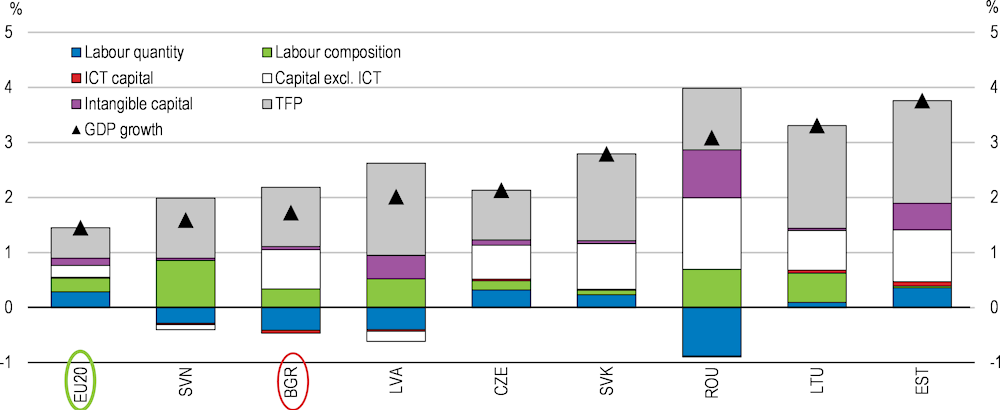

The working-age population is set to shrink by a quarter in less than 20 years. The decline in the working-age population has already begun (Figure 2.3 Panel A) and the economy prior to COVID-19 had been hit by a shortage of workers. Workers are set to become older as younger age groups shrink substantially in the next decade (Figure 2.3 Panel B). It is critical to make the most of the working-age population by maximising labour-force participation (Key Policy Insights) and skills for an ageing workforce. This makes it important that the population benefits from education and training throughout the lifecycle.

Figure 2.3. The working-age population is shrinking and ageing quickly

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019), World Population Prospects 2019, Online Edition. Rev. 1.

Skills and innovation will need to take on an increasing role in driving productivity given the declining workforce. Poor PISA progress, high dropout rates in secondary education, and the large proportion of NEETs (young people neither in employment nor in education or training) are worrying indicators for a country facing ever-shrinking younger cohorts. Innovation is held back by the low levels of R&D public and private spending, and much lower than average EU employment and export share in high and medium tech manufacturing. Increasing digitalization and the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) to improve products and processes is important to raise firm productivity.

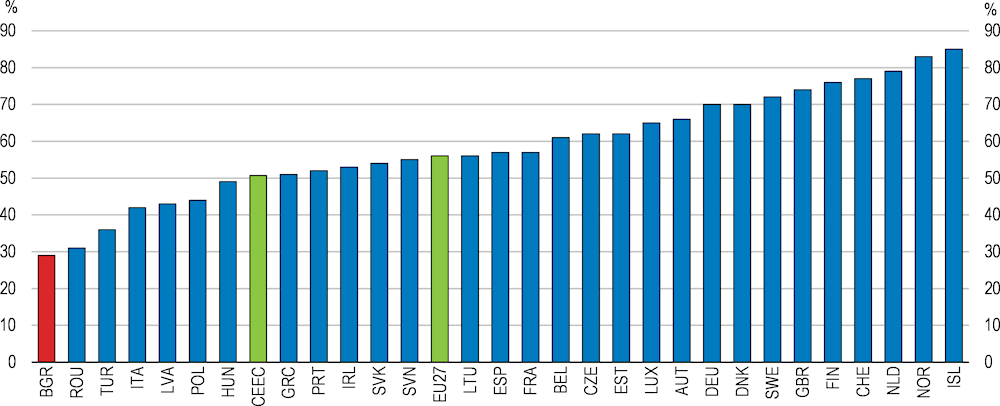

Investment has declined and firms devote a lower share of capital to R&D and ICT activities than on average in the EU. The gross investment rate of non-financial corporations was 23.8% in 2017, falling from over 30% prior to 2013 (Eurostat). While this is close to the EU average, increasing investment, particularly on R&D and ICT, will be important to increase firm productivity. Attracting foreign direct investment could contributed to further develop the export sector and increase value-added (Key Policy Insights). The proportion of firms that invest is the lowest of any EU economy. Two-thirds of companies invested in the last financial year compared to 85% on average in the EU and in the United States according to the 2019 EIB Group Survey on Investment and Investment Finance (EIBIS, 2019). Enterprises invest mostly in machinery and equipment and put substantially lower investment shares into intangible inputs like R&D and ICT compared to the EU average. Firms cited the top two barriers to investment as the availability of skilled staff and uncertainty on future prospects (EIBIS, 2019). The use of internal funds to finance investment (69%) is above the EU average (62%), though firms do not report a large problem with accessing credit. The measures focused on in this chapter are aimed at improving the investment climate for firms. The OECD’s forthcoming Investment Policy Review of Bulgaria report will give an in-depth assessment of the barriers and opportunities in the country.

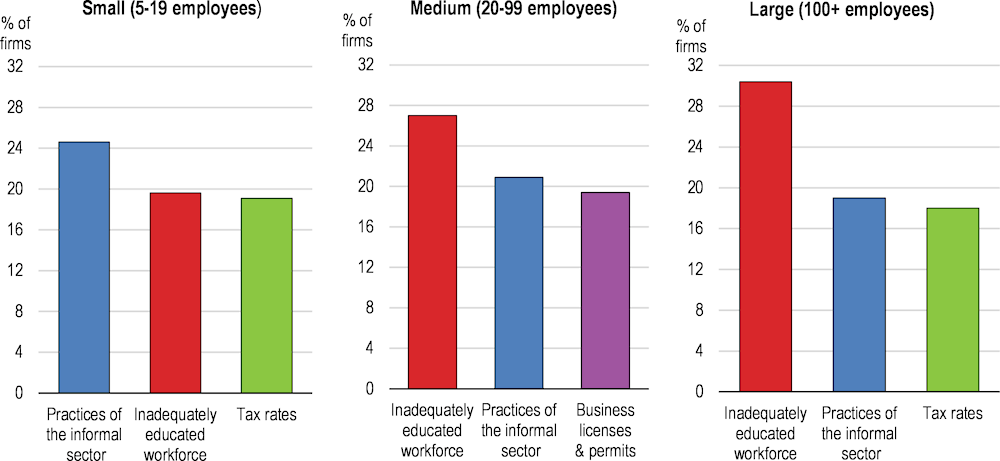

A shortage of appropriately skilled workers comes out as the biggest business environment constraint faced by firms in multiple surveys pre-COVID-19. An inadequately educated workforce and competition from informal firms came out as the top two obstacles to business growth in the 2019 World Bank’s Enterprise Survey, with skills ranking as more important for larger firms and informal practices for small and medium-sized firms (Figure 2.4). Both these factors are given more importance by firms than in OECD countries on average. While tax rates feature as the third largest hindrance overall, when examined the tax burden on firms appears comparatively low. The corporate tax flat rate of 10% is the second lowest in the EU. Employer contributions to social security at just under 20%—the incidence of which falls more on labour than on firms—are relatively low in the EU context.

Figure 2.4. Informality and inadequate skills are the top two constraints for businesses

Top three business constraints by firm size, 2019

Informal practices of concern in Bulgaria are tax evasion and the high incidence of under declared work. The informal economy is relatively large compared to EU countries, but has contracted over time and its size is in line with the country’s level of development (Key Policy Insights). Informal employment does not occur because people work without a contract, but instead is due to workers receiving an additional payment not included in their contract. Taxes, health and social insurance are not paid on this additional informal payment (“under declared work”). The country has made progress in reducing the size of the informal economy and increasing tax compliance, with a strong emphasis on employing a range of detection and deterrence measures to fight tax evasion and ensure registration of labour contracts. The motivation for accepting under declared work on the side of employees appears to be strongly related to wanting to increase take-home incomes, low tax morale and wide acceptance of the practice rather than avoiding excessive bureaucracy (European Commission, 2019a).The current crisis is likely to lead to increased informality given deteriorating labour market conditions.

The chapter goes on to focus on economy-wide structural reforms to enhance the business environment, raise productivity in the enterprise sector and increase convergence. These cover increasing competition, reducing red tape for enterprises, easing firm exit and rehabilitation, and enhancing skills and innovation. Improving infrastructure, further supporting financial development, and reducing corruption are important and dealt with elsewhere in the Economic Assessment (Key Policy Insights and Chapter 3).

Improving the regulatory framework for enterprise activity

Reducing regulatory barriers to competition

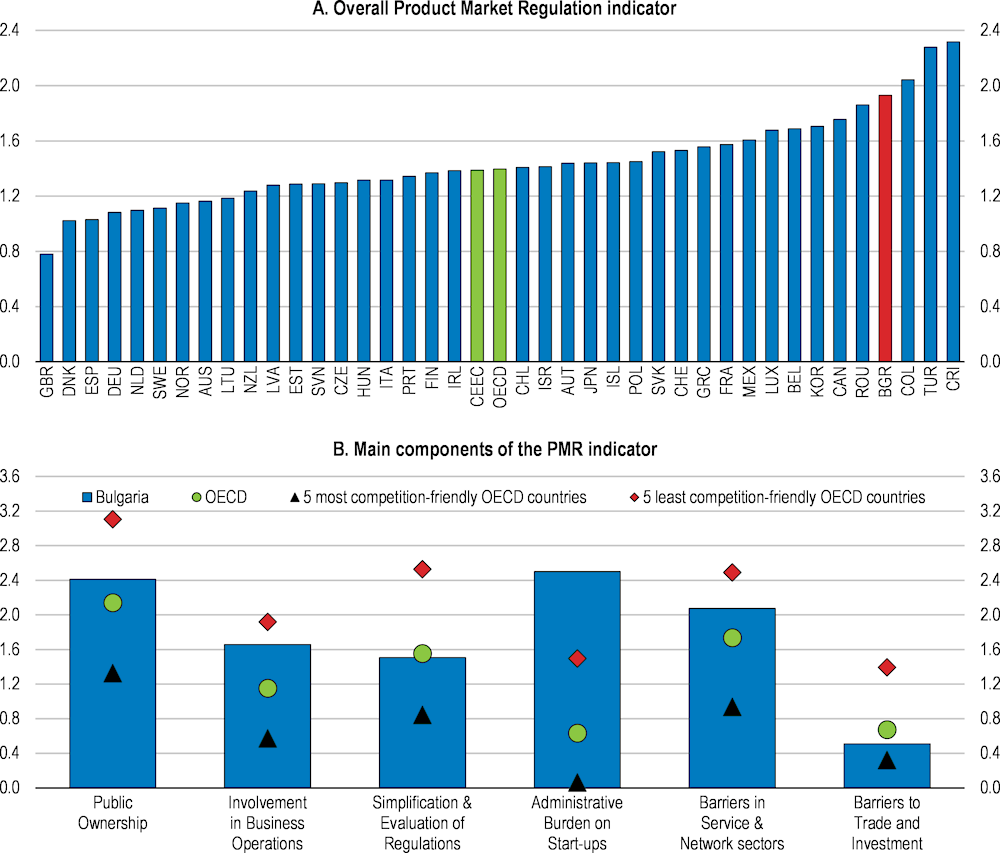

Regulatory barriers to competition are generally high and reducing them can raise productivity by supporting a more efficient allocation of resources in the economy, a challenge that becomes all the more pressing in the wake of COVID-19. The OECD’s product market regulation indicators measure how competition friendly a country’s regulatory environment is by assessing the alignment of its laws and regulations with international best practice. The regulatory barriers to competition in Bulgaria are higher than for all OECD countries, with the exception of Colombia and Turkey, based on the results for the economy-wide 2018 product market regulation indicators (Figure 1.20, Panel A). Breaking down the economy-wide measure indicates that Bulgaria is notable for high administrative requirements and an onerous licensing regime for new businesses and extensive public ownership of large operators in network sectors (Figure 1.20, Panel B). As an EU member, the barriers to trade and inward foreign direct investment are low relative to the OECD average (Figure 1.20, Panel B).

The incumbent companies in some key network sectors, such as electricty generation, gas import and retail supply, and rail transport, are completely owned by the state. Such an extensive presence of the state in sectors, even if they are open to competition, can generate distortions and affect the incentives for private firms to enter and expand their presence in these. The energy sector in general has undergone increased scrutiny by EU and and Bulgaria has recently embarked on a series of reforms, including: the setting up of a power exchange and steps for opening the retail market to competition. E-communications, a sector with limited state involvement, is open to competition compared to most OECD countries and has a regulatory environment that is close to international best practice. This provides a supportive basis for the acceleration of the development of the digital economy in response to COVID-19.

The electricity sector is composed of a regulated segment where prices/tariffs are set by an independent regulator (by reference price or formula), the Energy and Water Regulatory Commission (EWRC), and a liberalised segment with free pricing between producers and consumers. The sector is dominated by a few key players and in practice there are geographical monopolies in supply. Natural gas markets are also concentrated and consumers have been prevented from having a choice of suppliers. The European Commission fined the state-owned Bulgarian Energy Holding (BEH)—the holding company for a number of enterprises involved in electricity generation, supply and transmission, natural gas storage, transmission and supply, and coal mining—and two subsidiaries for blocking access to other wholesale gas suppliers to its gas infrastructure in 2018. The Bulgarian Commission on Protection of Competition is putting a strong focus on investigating anti-competitive practices in the energy sector and increased measures are expected to open up the sector. Further opening up the network sectors to new entrants could lead to improved productivity. Firm-level analysis for Bulgaria has shown that improved network service sector performance can enhance downstream firm performance (World Bank, 2015).

There also are very high barriers to entry in the legal professions (lawyers and notaries) as indicated by the product market regulation indicators, which show that restrictions, especially in terms of conduct, are higher than in most other OECD or CEEC countries. This is consistent with a recent assessment by the European Commission that found across all the professions studied, restrictiveness is highest for lawyers in Bulgaria (European Commission, 2017). The restrictiveness of these professions is related to high barriers to entry, but in particular due to very restrictive conduct regulations. In particular, legal firms cannot be set up as companies and not even as limited liability partnerships, fees are still regulated and there is a prohibition to cooperate with any other professions. As for notaries, these are heavily regulated in most European countries, and entry restrictions are very high. In Bulgaria, this is further reinforced by extensive restrictions also on the conduct of these professionals, ranging from all fees being regulated to prohibition of any form of advertising and the permission to operate only in a sole proprietorship with no limited liability. The government is aiming to ease entry to the notary profession with a law drafted to ease restrictions on age and nationality but there are no plans to address the extensive conduct restrictions. The product market regulation indicators measuring restrictions for architects and civil engineers, while higher than the OECD average, are not as onerous. The accountancy and real estate professions are completely deregulated, achieving the best possible score in terms of lack of barriers to entry.

Figure 2.5. Bulgaria stands out for its high barriers to competition

Index scale of 0-6 from least to most restrictive, 2018

Note: Information for OECD countries refers to laws and regulation in force on 1 January 2018, while for the five EU member states that are not OECD members refers to laws and regulation in force on 1 January 2019. The OECD average does not include the United States.

Source: OECD, 2018 Product Market Regulation Indicators database.

Easing the restrictions on regulated professions has been found to facilitate greater competition. For example, Greece had some of the highest regulatory barriers for regulated professions in the OECD and from 2010 put in place reforms to ease the restrictiveness of regulated professions by removing restrictive entry and conduct regulations. Preliminary analysis suggests that the reform had a positive effect on employment and there are some indications of a fall in the prices for consumers of legal services, accounting and tax consulting services and physiotherapy services. Real estate agent and notary services exhibited price reductions, especially in the case of notary fees for high value real estate transactions (Athanassiou et al., 2015).

Decreasing the red tape required to set up a firm

The administrative burden for opening joint-stock companies and personally-owned enterprises, including getting all necessary permits, is relatively according to the OECD’s 2018 Product Market Regulation indicators (Figure 1.20 Panel B). The added burden in Bulgaria is mostly explained by the need to get multiple certifications and approvals from state bodies compared to countries with a lower administrative burden for opening a new enterprise. Rather than being due to fees or license outlays, it is the high cost in terms of time taken to fulfil administrative requirements that results in Bulgaria scoring poorly. Estimates are that it takes 23 days for somebody to complete the necessary procedures versus 9.2 days on average in advanced OECD economies (World Bank, 2020). Higher entry costs for new businesses have been found to reduce output per worker and total factor productivity (Barseghyan, 2008).

A priority is to get rid of the necessity for a business start-up to contact multiple agencies. Nine public and private bodies typically need to be contacted to start a personally-owned enterprise with up to nine employees, compared with two in Romania (OECD, 2018a). To achieve this Bulgaria could extend the one-stop shop to cover the issuing of all licences and permits, and to accept all notifications necessary to open up a business. It could reduce the steps required to open up a business by removing the requirement to open a bank account and deposit the EUR 2 minimum symbolic required capital as part of the preregistration requirements; reducing the number of certifications that have to be provided by a lawyer/notary; reducing the VAT registration time (currently taking 12-14 days), or allowing for simultaneous business and VAT registration; and eliminating the need to physically visit the Commercial Registry to collect the (newly) registered company’s certificates. In addition the country could also adopt a ‘’silent is consent’’ rule to speed up the approval process for all permits and licences.

Facilitating firm exit and rehabilitation for viable enterprises

A more rapid and effective bankruptcy framework would spur on the exit of non-viable firms in financial difficulties or the restarting of activity of firms requiring a restructuring of financial obligations, thereby ensuring resources are allocated to more productive firms. Insolvency in Bulgaria is a relatively lengthy and complex process resulting in low asset recovery. Insolvency tends to be implemented late into enterprises getting into financial difficulties and so is used to liquidate firms rather than to engage in restructuring proceedings to help viable companies stay in business. Opening an insolvency proceeding on the side of the creditor is often a long and arduous task given that the judicial practice is for financial expertise to be required to examine a variety of insolvency ratios rather than the liquidity or cash-flow test outlined in the law (World Bank, 2016a). Bankruptcy is most likely to end up in liquidation of company assets piecemeal, with very few firms making it through insolvency proceedings intact. This not only makes it longer for companies to wind down operations, but also inhibits the sale of firms that remain viable. Creditors do not view bankruptcy proceedings as effective for debt collection (World Bank, 2016a).

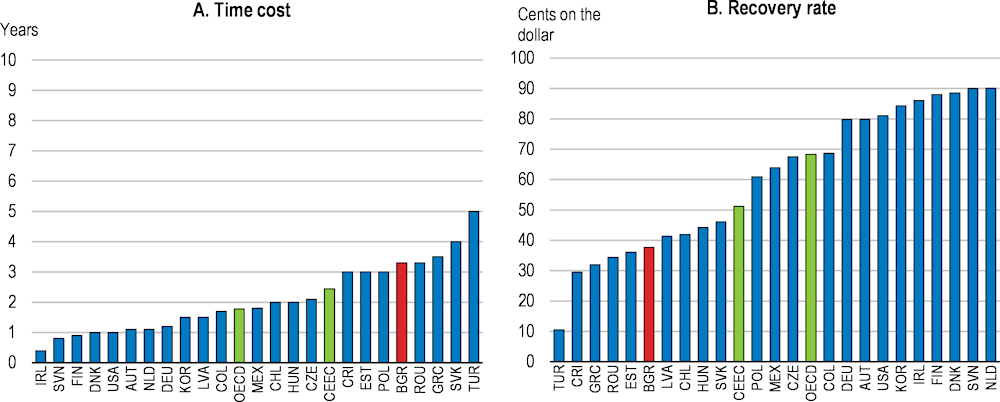

It takes 3.3 years on average to resolve a bankruptcy compared to 1.7 years in advanced OECD economies (Figure 2.6, Panel A). A low recovery rate of 38 cents per dollar is achieved compared to the 70 cents achieved in advanced OECD economies (Figure 2.6, Panel B). While the recovery rate has improved from 34 cents per dollar in 2004, the time taken for creditors to recover their credit has not changed. The cost of insolvency proceedings is slightly lower than the high-income OECD average of 9% of the estate (World Bank, 2020).

Figure 2.6. Insolvency is relatively lengthy and results in a low recovery of assets for creditors

Resolving insolvency, 2020

Note: The World Bank is conducting a review and assessment of data changes after a number of irregularities have been reported regarding changes to the data in the Doing Business 2018 and Doing Business 2020 reports. This may affect the data presented in these figures.

Source: World Bank, Doing Business Database 2020, https://www.doingbusiness.org/.

Increasing the use of business restructuring proceedings by debtors and creditors before a business becomes insolvent is a priority. Part of the reason that rehabilitations are relatively unusual in Bulgaria is that there is a substantial degree of distrust in the bankruptcy process reported on the side of creditors and debtors (World Bank, 2016). New legislation was introduced in 2016 to allow firms to restructure their debts outside of insolvency proceedings. The aim of this reform was to allow an enterprise in temporary financial difficulties to re-negotiate its debts with its creditors, thereby enabling the enterprise to restart its business activities. To increase the use of firm rehabilitation proceedings by debtors, the plan is to put in place an early warning system to encourage debtors to take early action to avoid insolvency and establish a debt forgiveness procedure. In addition, rehabilitation proceedings are to be improved to ease access and mechanisms are to be introduced to protect new and interim funding received by enterprises engaged in a rehabilitation process. Deepening reforms that encourage the preservation of viable companies in financial difficulties could save jobs as well as reduce costs. This is all-the-more relevant given the current COVID-19 pandemic situation.

Easing discharge from debt is important to provide a fresh start to entrepreneurs. Many will have used their own assets and credits to set up a business. In Bulgaria, bankruptcy does not give entrepreneurs the right to discharge all their personal debt related to the insolvent business and entrepreneurs who go into insolvency do not have access to debt settlement procedures. Debtors get certain relief from personal liability for specific types of debts, but not all. It is of course necessary to ensure that any reforms do not result in abuse of the system to get out of personal debt not necessarily connected with the business being wound down.

The government has identified gaps in the insolvency framework and come up with a timeline for implementing changes. Bulgaria’s Council of Ministers adopted a road map for legislative and procedural reform to make the bankruptcy and rehabilitation framework more effective in July 2019 (Box 2.1). Legislative changes are to be put in place in 2021, with ongoing implementation support including capacity building for the judiciary and other involved professionals, enhancement of the judicial infrastructure and an upgrading of electronic communication and data collection systems. The successful implementation of the proposed reform depends on the active participation of all stakeholder groups at each stage of development of the amended framework. With this in view, the government has planned a detailed plan for stakeholder engagement and consultation.

The implementation of the planned insolvency and restructuring reforms by 2021 will make it easier to carry out restructurings of viable firms and to ease bankruptcy procedures for firms that will not survive the crisis. Key reforms include setting formal requirements for the insolvency petition by a debtor to open a proceeding; and using a cash flow or liquidity criteria as the test of insolvency when a creditor makes an application for a debtor’s insolvency. To accelerate proceedings, multiple applications for bankruptcy of the same debtor should not be required to be consolidated in order to declare insolvency. Allowing multiple creditors to file applications separately and dealing with them in parallel, rather than delaying a bankruptcy application because of the introduction of new filings, would also speed up the process. Creditors would need to have cost-effective and timely access to the claims recognition and resolution procedure. The exceptions to the stay on enforcement by creditors with special pledges and state claims should be eliminated. Having such exceptions threatens the negotiation and drafting of a rehabilitation or insolvency plan if it means part of the assets are sold beforehand to meet prioritised obligations. It will be important for the success of the reform to implement complementary policies on judicial efficiency, taxation and regulation.

Pushing forward insolvency reforms will be important to support the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis, particularly the reallocation away from activities that are less viable in the medium term. Given the relatively high NPLs in Bulgaria, reforms would increase creditor recovery of losses, thereby supporting the growth of credit markets. In looking at the options for responding to a rise in insolvency and debt overhang due to COVID-19, recent OECD work identifies a priority being to rapidly put in place to legislation measures to enable the rehabilitation of viable enterprises in financial difficulties through preventative restructuring or pre-insolvency framework (OECD, 2020a). The advice is that such a framework could be developed to be in line with the EU Directive on Preventive Restructuring Frameworks and Second Chance. This could be complemented by tax or other incentives to restructure debts. In the case of Bulgaria, this would require a revision to legislation to allow firms to proceed to preventative restructuring without fully opening an insolvency proceeding. On SMEs, Bulgaria could follow the OECD recommendation to move towards best practice by simplifying formal insolvency procedures and promoting informal arrangements for SMEs (OECD, 2020c).

Bulgaria suspended all procedural deadlines for ongoing court litigations, arbitrations and executions not under the Penal Code as part of its response to COVID-19, including those related to insolvency, during the state of emergency from 13 March to 13 May 2020. This may lead to a backlog of work for courts also facing a rise in caseload due to COVID-19. The capacity of the insolvency regime to deal with this rise in caseload due to COVID-19 may require additional resources to improve judicial infrastructure.

Ensuring appropriate access to credit through crisis support programmes can prevent viable firms from going into arrears/late payments until debt restructuring can be carried out. If crisis endures for some hard-hit sectors, the challenge will be to strike the right balance between supporting viable jobs and enterprises through continued financing, and not inhibiting the re-allocation of workers into new jobs.

Box 2.1. Bulgaria’s Insolvency Reform Roadmap, 2019-2022

The government adopted the roadmap to address the gaps in the insolvency framework in June 2019. The roadmap incorporates the transposition of EU Directive 2019/1023 on Restructuring and Discharge of Debt, which has a transposition period of two years that begun in July 2019. Wide stakeholder consultations on the changes are being undertaken with representatives of government agencies, the judiciary, the legal professions and experts/academics. The following summarises the timeline and main provisions of the roadmap.

Timeline for legislative changes. The Ministry of Justice set up a working group to draft the legislative amendments by end-November 2020. Consultations are to take place until end-December 2020 and the updated bill is to be included in the legislative program of the Council of Ministers in January 2021. The amended and supplementary by-laws are due to be prepared and consulted on, and put in place from October 2021 onwards. Capacity-building and training programmes to complement the reform are being carried out from September 2019 to August 2022.

Improving access to insolvency. The legislative changes aim at easing and making faster access to insolvency proceedings and stabilization procedures, including shortening procedural deadlines. This includes having a single process for processing applications within the same insolvency proceedings; reforming the submission and acceptance phase; establishing accelerated procedures for small businesses; setting out objective grounds for initiating proceedings; increasing efficiency of property liquidation; and compulsory imposition of an insolvency plan between classes of creditors.

Workout and rehabilitation. Planned actions include the establishment of an early warning system with the aim of getting debtors to take action to avoid insolvency; and a debt forgiveness procedure. The reforms also will put in place a comprehensive overhaul of rehabilitation proceedings and introduce new mechanisms to protect new and interim funding.

Enhancing governance and capacity building. Governance is to be improved through putting in place a comprehensive framework on the duties and responsibilities of managers/directors, better regulation of the profession of trustees and officials in the bankruptcy arena; and additional safeguards to prevent bad faith of parties involved in insolvency and stabilization proceedings. The capacity of the regulator is to be enhanced through the provision of the human and financial resources needed for effective regulation.

Judicial infrastructure. Improved judicial infrastructure is critical for the success of the reform. The reform involves changing the rules governing local jurisdiction; regulating the role of experts, putting place special procedural rules for appeals, and providing the opportunity for judges to delegate administrative tasks to assistants. Bankruptcy and stabilization proceedings are due to be made smoother through the promotion of the use of electronic communication throughout the process. A code of ethics and professional standards is to be prepared for professionals involved in proceedings.

Training and communication. An updated training needs assessment is being carried out. The aim is to provide specialised trainings for bankruptcy and stabilization judges and legal personnel, including trustees, on the amended legal framework and new processes. A handbook is to be prepared on bankruptcy and stabilisation procedures, including templates for reporting activities. Systems are be put in place to implement electronic means of communication for insolvency and stabilisation proceedings, and to improve the quality and availability of statistical data.

Source: Government of Bulgaria, 2019, Roadmap for implementation of the recommendations concerning the frame for bankruptcy and stabilization in Bulgaria, Adopted by Council of Ministers on June 19, 2019, https://www.minfin.bg/upload/41380/CoM%20-%20Roadmap%20on%20Insolvency%20Framework%20Reform%20in%20BG.pdf

Improving corporate governance of SOEs

The leading role SOEs take in providing electricity, ports and railway infrastructure makes the recent government efforts to improve corporate governance important for the competitiveness of the economy. There are about 233 SOEs held by the central government, excluding the healthcare and social service SOE entities largely made up of state and municipal hospitals. The overall SOE sector represents 6.6% of total employment (OECD, 2019a). Prior to the recent reform, Bulgaria performed behind the OECD average and most CEEC countries, except for Lithuania, on the insulation of SOEs from market discipline and political interference in the management of SOE in terms of ensuring a level playing field between SOES and their private competitors, as measured by the OECD’s product market regulation indicator.

Bulgaria undertook a reform to improve the governance of SOEs by reviewing and aligning legislation with the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of SOEs as part of its commitments to join the ERM II and the Banking Union. The country fulfilled its commitment through the revision of legislation on public enterprises in 2019 and now adheres to the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of SOEs. The recent corporate governance reforms establish a framework to provide stronger ownership coordination and monitoring, including through a new centralised coordination unit; better disclosure for SOEs and the state, and independently- and transparently-nominated boards with qualified members (OECD, 2019a). SOEs that are engaged in commercial activities are to take on the same legal form as private companies in order to reduce unfair competition.

The new legal framework puts in place the basis to address the most important concerns on SOE governance. The government has established the necessary by-laws and is finalising the implementing arrangements for relevant public agencies, including municipal bodies. The 2019 OECD Review of the Governance of SOEs (OECD, 2019a) sets out recommendations for near-term implementation. The highly decentralised ownership arrangements whereby 17 ministries have oversight over SOEs is to be augmented by the establishment of a centralised ownership coordination unit. The coordination unit will require sufficient autonomy and resources (qualified staff, finance and institutional authority) to carry out its mandate. The implementing rules will need to ensure the submission of all necessary financial and non-financial information to the new coordination unit, the Ministry of Finance and the line ministries. The new legislation establishes the educational and professional qualifications for board members and standards they should fulfil to ensure independence and integrity. The new law harmonises the SOE nomination process for the appointment of independent Boards of Directors in SOEs.

The new legislation on public enterprises represents an important element in the reform of the legal and regulatory environment for SOEs, but further aspects remain to be tackled. Bulgaria is retaining its current decentralised ownership arrangements under the new framework. The government may consider granting the coordination unit direct ownership over some SOEs given that decentralised ownership arrangements may lead to an insufficient separation of ownership and regulatory functions (OECD, 2019a). Currently, most large SOEs apply International Financial Reporting Standards, but the legislation does allow for them to choose whether to use these standards or to report according to national law. A further strengthening of accounting and disclosure requirements could occur if all large SOEs were required to adopt International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and use the same disclosure norms as listed companies (OECD, 2019a). The impartiality of boards of directors to political influence could be increased by permitting more than the currently allowed maximum 50% share of independent members and allowing the SOE board of directors to appoint and remove CEOs (OECD, 2019a).

Continuing regulatory efforts to support competition

The Commission on Protection of Competition (CPC) is an independent institution with a staff of 117 (OECD, 2020a), including the seven elected members of the commission, which compares favourably to staffing in EU countries with a similar population (41 in Austria and 74 in Portugal) (Global Competition Review, 2019). The budget of the CPC was adequate at EUR 2.6 million in 2019, though lower than in Austria (EUR 3.8 million) and Portugal (EUR 9 million). A leniency regime was introduced in 2011 for cartels and was used for the first time in 2019 to allow three companies involved in bid rigging for public tenders to provide information in return for one company receiving immunity and the other two reductions in fines (as set out by the law). The CPC is preparing legal amendments to strengthen further the leniency program. The CPC also conducts market studies, which are a powerful competition advocacy tool, as they allow the CPC to identify threats or obstacles to competition, which are not violations of competition law, and recommends actions to remove them.

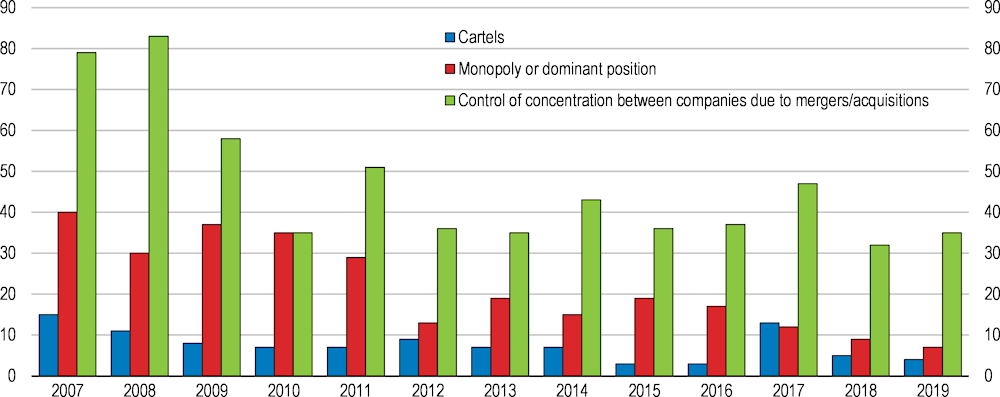

The CPC strongly focuses on the protection of competitive practices due to mergers/acquisitions, but there has been a decline in the numbers of decisions taken related to cartels and monopoly/dominant positions. Looking at the evolution of decisions issued by the CPC, there were 35 decisions related to mergers/acquisitions in 2019, in line with recent years but down on the higher activity of a decade ago (Figure 2.7). The CPC blocked two mergers and imposed conditions on several mergers in 2019 (OECD, 2020a). Decisions on anti-cartel enforcement and abuse of dominant positions have been falling since the peak of activity seen after joining the EU in 2007 (Figure 2.7). On cartels, the CPC’s efforts in 2019 were aimed at concluding a large proceeding related to the participation of over 40 entities in bid-rigging cartels for public procurement processes under the national programme for energy efficiency of multi-family dwellings (Chapter 3). The CPC sanctioned 27 undertakings related to these infringements (OECD, 2020a). There was an increase in the number of sector inquiries initiated in 2018, which addressed key sectors like the electricity market, the media market, the provision of bank services, and the production and sale of gasoline and diesel fuel in 2018. The energy sector has been a strong focus of the CPC and going forward there is an opportunity to boost competition in the sector with its decisions. The work has begun to show dividends with three local units of energy group CEZ fined (EUR 2.2 million) in June 2020 for abuse of dominant market position in negotiations with a payment services provider.

Figure 2.7. Activity related to confronting cartels and monopoly/dominant positions has declined

Decisions issued by Bulgaria's Commission on Protection of Competition, 2007-2019

Note: Data from Fora and Bugnar (2017) for 2007-2014 and OECD (2020b) thereafter.

Source: A. F. Fora and N. G. Bugnar (2017), "Implementing Competition Policy. Comparative Study - Romania and Bulgaria", Annals of Faculty of Economics, University of Oradea, Faculty of Economics, Vol. 1(2), pp. 319-327; OECD (2020b), "Annual Report on Competition Policy Developments in Bulgaria 2019", Report submitted by Bulgaria to the Competition Committee, DAF/COMP/AR(2020)40.

Creating a level playing field for public contracting

Efforts have been made to improve public procurement in recent years. A big push to modernise was made with the 2014 public procurement strategy and the adoption of legislation in 2016 that transposed the 2014 EU Procurement Directives into national legislation. The Public Procurement Agency has been confronting the challenge of modernising a system that made limited use of electronic procedures. The agency has implemented a centralised online portal on which all public procurement notices are posted and where each purchasing agency publishes procurement documents. The use of the centralised electronic platform for public procurement became mandatory for all government agencies and municipalities on 1 April 2020. Reform progress was positively assessed by the 2019 Cooperation and Verification Mechanism Report (European Commission, 2019b).

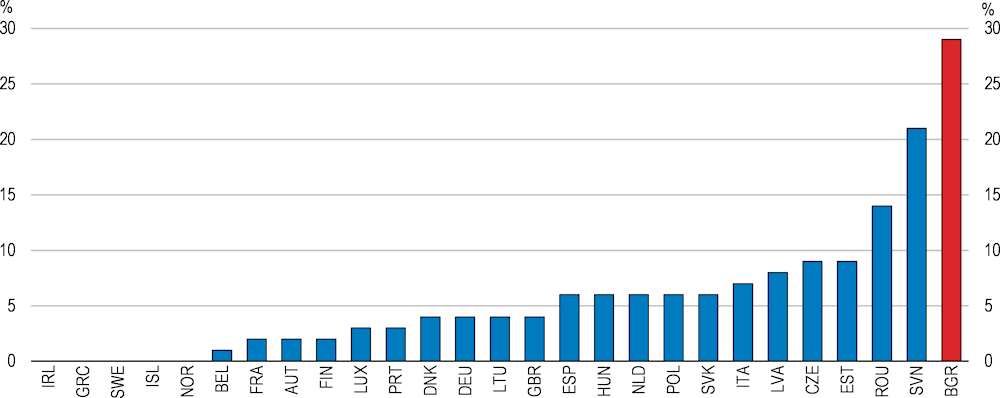

Further reforms are needed to continue to improve procurement outcomes. The World Bank carried out a review of public procurement procedures in 2019, which included follow-up actions and ex post checks and examined cases of conflicts of interest or corruption as part of the recommendations of the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (World Bank, 2019b). The recommendations to address continued challenges include putting in place more targeted measures to fight fraud, corruption and conflict of interest. Assessment activities to detect illicit practices need to be increased and rely on detailed data analysis. This can be helped by information provided by the new electronic system. For example, Bulgaria has the highest proportion of “no bid” procurement processes in the EU and unlike most countries these have grown over time (Figure 2.8). Here, in-depth analysis to find out the reasons behind no bid or single bid processes and looking at relevant international practices would be useful to limiting the incidence of such cases.

Figure 2.8. Too high a share of public procurement occurs without a call for bids

Proportion of procurement procedures that were negotiated with a company without any call for bids, 2019

Capacity building is a continued issue for public procurement in Bulgaria. The authorities plan to keep focusing efforts here, including to combat corrupt practices and to increase strategic capacity to conduct high quality analysis of procurement data and sector issues. Unfortunately, there is a high turnover of procurement officials at the local and national level and building capacity will involve retaining high-capacity staff. Overall, anti-corruption efforts need to result in criminal prosecutions (Key Policy Insights). The procurement system can help by implementing the World Bank’s recommendations to strengthen the reporting channels for corruption and conflict of interest, improve the complaints procedure and offer stronger protection to whistle-blowers.

Increasing skills and innovation

Increasing the availability of skilled workers is a key priority for enterprises

A shortage of skilled workers emerged as the biggest obstacle to business activity in surveys of Bulgarian firms pre-COVID-19 as the economy moved towards full employment. An inadequately educated workforce is the main constraint in the business environment reported by 30% of large and 27% medium-sized firms (World Bank Enterprise Survey, 2019). The 2019 Manpower Talent Shortage Survey found that 71% of large (250+) and 69% of medium-sized companies (50-250) report difficulty in filling positions putting Bulgaria in the category of countries where employers are reporting the highest skills shortages (ManpowerGroup, 2019). The difficulty in filling positions has been growing over time (up from 42% overall for firms in 2011) as the economy recovered from the 2008-09 crisis (which had a big impact on employment) and the labour force continued to shrink. As the economy recovers from the COVID-19 crisis and the workforce continues to shrink, the shortage of higher skilled workers may remerge as an obstacle for firm growth, particularly in the exports sector.

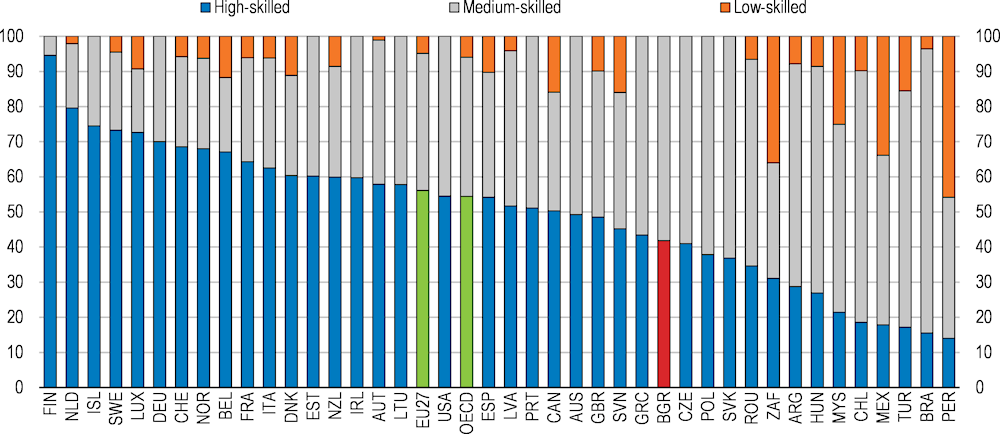

Pre-COVID-19, there was a shortage of workers with medium-to-high skills whereas there were no shortages for those in low-skilled occupations. The OECD Skills for Jobs Database 2018 indicates that shortages existed for high- (42%) and medium-skilled (58%) occupations (Figure 2.9). Demand for high-skilled employees was under the OECD average. In the future if the convergence process speeds up, then the demand for higher-skilled occupations would be expected to increase. Enterprises in the information and communications sector have struggled the most to find appropriate talent. Construction and agriculture, forestry and fishing, which typically employ lower-skilled labour, had a surplus of workers.

Figure 2.9. Shortages are for medium- and higher-skilled employees

Share of employment in high demand by skill level

Note: High-, medium- and low-skilled occupations are ISCO occupational groups 1 to 3, 4 to 8 and 9 respectively. Shares of employment in each skill tier are computed as the corresponding employment in each group over the total number of workers in shortage in each country. Data refer to the latest year for which information is available.

Source: Elaborations based on the OECD Skills for Jobs Database (2018).

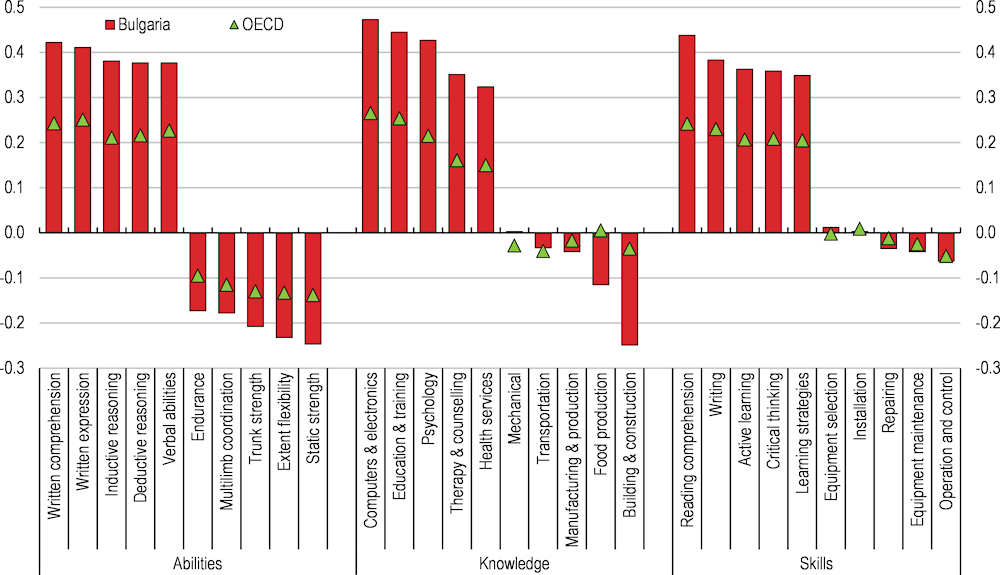

The types of competencies that were most in demand in Bulgaria pre-COVID-19 were those connected to complex, non-routine activities relevant to key growth sectors and for the new economy. The OECD Skills for Jobs indicators translate occupations that are in high demand into a measure of skills in shortage using the occupational skills classification database, O*NET. Competencies in the OECD Skills for Jobs Database are broken down into three categories. Abilities refer to the capacity to perform an activity not necessarily linked to a specific job task, such as trunk strength or the ability of abdominal and lower back muscles to support bodily movement over time. Knowledge represents faculties acquired by individuals through education or training, such as knowledge of computer programming for an IT specialist. Skills developed through both experience and education/training that the individual can bring to job or real life situations, such as critical thinking. Across the three categories, Bulgaria had a surplus of workers with competencies in routine manual and physical skills and abilities, often in excess of the OECD average (Figure 2.10). Shortages were highest in the knowledge of computer hardware and software, programming and applications, and education and training. Cognitive abilities such as reading comprehension, written comprehension and expression, and critical reasoning are in strong demand across occupations. As with technological change in the past (Autor et al., 2003), further moves towards digitalisation, robotics and artificial intelligence are likely to continue the shift in skills demand away from the routine and physical/manual tasks to more complex competencies. It is likely that it is these higher-skilled workers whose jobs will be more protected from the impact of the COVID-19 crisis.

Figure 2.10. Large shortages exist for complex and non-routine competencies

Knowledge, skills and abilities with the largest shortages and surplus, 2015

Note: Positive values represent shortages (e.g. unsatisfied demand in the labour market for the analysed dimension). Negative values represent surpluses (supply exceeds demand in the labour market for the analysed dimension). Results are presented on a scale from -1 to +1. The maximum value represents the strongest shortage observed in Bulgaria per area. Abilities refer to the competence to perform an observable activity (e.g. ability to plan and organise work; attentiveness; endurance). Knowledge areas refer to the body of information that makes adequate performance of the job possible (e.g. knowledge plumbing of a plumber; knowledge of mathematics for an economist). Skills refer to the proficient manual, verbal or mental manipulation of data or things (e.g. complex problem solving; social skills).

Source: OECD Skills for Jobs Database (2018).

Basic education is not providing a firm foundation for skills

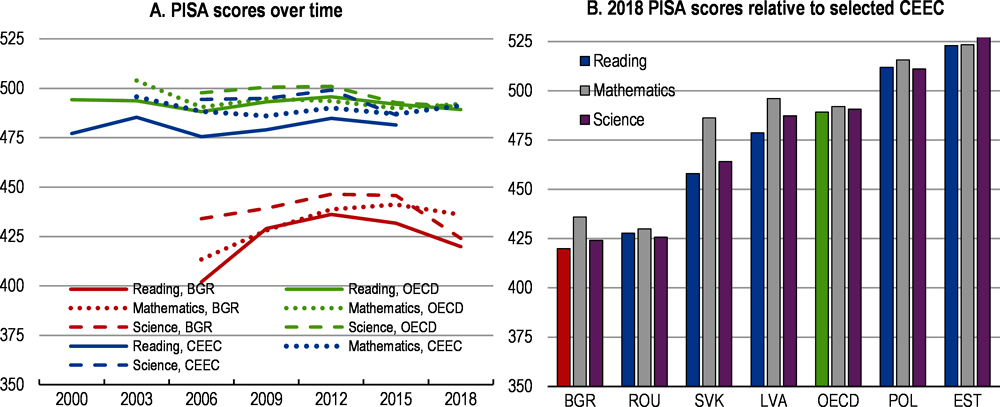

A better foundation for skills needs to be set early in life. Performance in the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which evaluates competencies in reading, mathematics, and science among 15-year-olds, is well below OECD and CEEC averages (Figure 2.11). Students ranked lowest in the EU in science and reading, and second last (in front of Romania) in mathematics. Science performance in 2018 dropped below the level of 2012 and 2015, experiencing one of the largest falls over 2015-2018 among PISA participants. Of concern is the large share (41%) of 15-year-olds who were assessed as functionally illiterate by the PISA reading test in 2018 (below level 2) (Figure 2.12). Having such a large proportion of students who have problems moving beyond a very basic interpretation of text poses a large mismatch between the more complex skills demanded by the labour market and will make difficult future lifelong learning participation. Only a small share of students perform at the highest level of proficiency in PISA tests, 2% in reading in 2018 compared to 7% in CEEC and 9% in OECD countries. School dropout rates are high with 14% of early leavers from education and training in 2019, a one-percentage point increase since 2014. This is the fourth highest rate in the EU after Spain, Malta and Romania. Roma students have a particularly high likelihood of not finishing school (Chapter 3). Early childhood education participation (aged 4 and over) is low at 82% in 2018 compared to an EU (27) average of 95% and has fallen in the past five years from 89% in 2014.

Figure 2.11. PISA education scores lag behind the OECD and CEEC

Note: CEEC is an unweighted average of the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia.

Source: OECD (2019b), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en.

Recent education reforms passed in 2016, which aim to reorient the curriculum and assessment framework to improve student learning, go in the right direction. Apart from implementing a new syllabus that puts an emphasis on mathematics, science, and literacy and digital skills, there are plans to introduce an external student assessment based on new learning standards in the 7th and 10th grade. Language support also is to be extended for pupils who do not have Bulgarian as their first language—a group who underperform in PISA. Using the results of the new external assessments to help monitor implementation of the new curricula and inform teaching and learning practices will be critical to achieving a better performance.

A big challenge is to attract and train large numbers of new teachers in the next decade, with 51% of all teachers aged 50 and above (OECD average 34%) according to the OECD’s Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) (OECD, 2019c). The recent moves to increase teacher salaries over time will be important to ensure qualified candidates enter and stay in the profession. Providing adequate training for new teachers and continued professional development will help to raise education standards and increase teacher satisfaction. Training in teaching special needs students is the area where the highest share of teachers report a particularly high need in Bulgaria: 27% of teachers have not received training in special needs as part of their professional development activity compared to 23% on average in the OECD and higher than all EU countries for which there is data with the exception of Estonia and Romania. Teachers report in TALIS that they have a high need for continued training is in ICT (23% compared to OECD average of 18%), knowledge of the curriculum (20% compared to an OECD average of 8%) and their subject field (19% compared to OECD average of 9%). Teachers cite the high expense, lack of time and incentives as the main obstacles to participation in professional development (OECD, 2019c). The need for resources for teacher training and professional development is likely to continue to grow for both in-service teachers and new entrants to the profession.

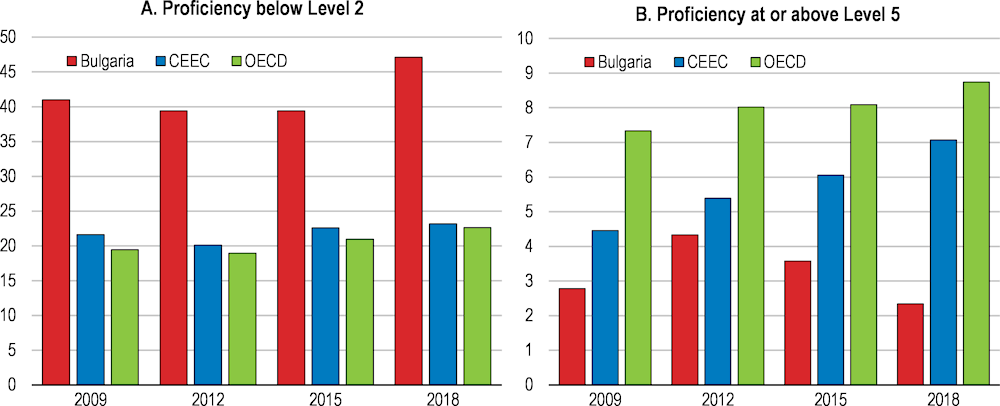

Figure 2.12. A growing share of 15-years olds lack basic proficiency and few perform at a high level

Proficiency level in reading

Note: The low achievers are defined as those with less than 407.47 score points (Level 2) and the top performers are those with 625.61 score points (Level 5) or above.

Source: OECD (2019b), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, Table I.B1.7, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en.

Improving the performance of the less socioeconomically advantaged will be key to driving up national performance given the much larger inequity in performance at the top and bottom in Bulgaria. This involves tackling the rural-urban divide and ethnic disadvantage (see Chapter 3). Partly this involves ensuring poorer municipalities have adequate resources for educational activities and infrastructure modernisation (European Commission, 2019c). Continuing efforts to track and prevent school dropouts is key to prevent future labour market vulnerability. Expanding preschool education to have universal coverage, especially for the most disadvantaged children and those in rural areas, would provide a basis to narrow the skills gap. A study of PISA performance found that the provision of two years’ preschool education would increase the scores of low achievers and minorities by up to 10 and 19 points, respectively (World Bank, 2016b). Implementing the draft law covering preschool school education to provide support to municipalities that lag behind in provision to those aged 4 and older would go some way to open up access. Eliminating fees for preschool is an important step for the socially vulnerable.

Vocational education and training could better meet labour market demands

Improved vocational education and training (VET) outcomes are important to provide needed occupation-specific skills and to meet changing skills demand. Over half of upper secondary students (51% in 2017) attend a VET programme (Eurostat). While the employment rate of recent VET graduates has increased, at 66% in 2018 it is still substantially below the EU average of about 80% (European Commission, 2019). There could be further moves to strengthen the links between employers and VET. VET provision mostly is based in schools with some practical learning in workshops and workplace assignments. More links should be sought between local employers and the VET system, such as the dual apprenticeship pilot currently underway. Adult enrolment in VET in Bulgaria is low and increasing adult access and take up of VET is a priority given the growing skills deficits.

Given that a third of VET graduates do not gain a VET qualification (Bergseng, 2019), a welcome reform is that from 2022 sitting a state examination for a VET qualification will be compulsory for students. The recent introduction of technical qualifications for study after the age of 16 in the United Kingdom is an example of developing a technical pathway that is of equivalent standing of the academic qualification A-level route. The T-level (technical-level) technical qualification in the United Kingdom is to be introduced over 2020/21-2022/23 and is to be taken by students at age 18 after two years of study encompassing a technical qualification, other occupation-specific requirements, a placement in industry, and training in maths, English language and digital skills (United Kingdom’s Department of Education, 2019). The plan is to replace a large number of technical qualifications with T-levels in 25 subject areas. The aim of introducing T-levels is to put technical education on an equal footing with the academic education option—the Advanced-level or A-level. A-levels are subject-based qualifications that U.K. students obtain following the last two years of secondary schooling, generally at 16-18 years of age, and are used by universities to assess the qualifications of applicants for admission. One T-level is to be equivalent to the usual qualification of three A-levels in the academic stream. Recipients of the qualification could go directly into employment, pursue further technical education, such as an apprenticeship, or opt to go into higher education.

While Bulgaria involves social partners in VET policy decision-making at the national level, the system could increase its focus on local labour market conditions by involving much more closely with local employers, union representatives and local government officials. Decision-making autonomy should be incrementally increased at the subnational level for those institutions that have proven capacity to deliver on increased responsibility (Bergseng, 2019). This would allow providers to link much more closely to local labour demand. Moving responsibility away from the national level also would make sense to remove the heavy administrative burden that falls on the Ministry of Education from its direct ownership and management of the country’s VET schools. This would free resources to allow the Ministry to concentrate on its core functions of policy planning, monitoring and reviewing the country’s learning programmes. Putting in place the necessary capacity among local actors to take up these responsibilities will be a challenge as currently municipalities and schools have limited involvement in VET governance. A strong quality assurance system would need to be put in place for providers that ensures fulfilment of national policy objectives.

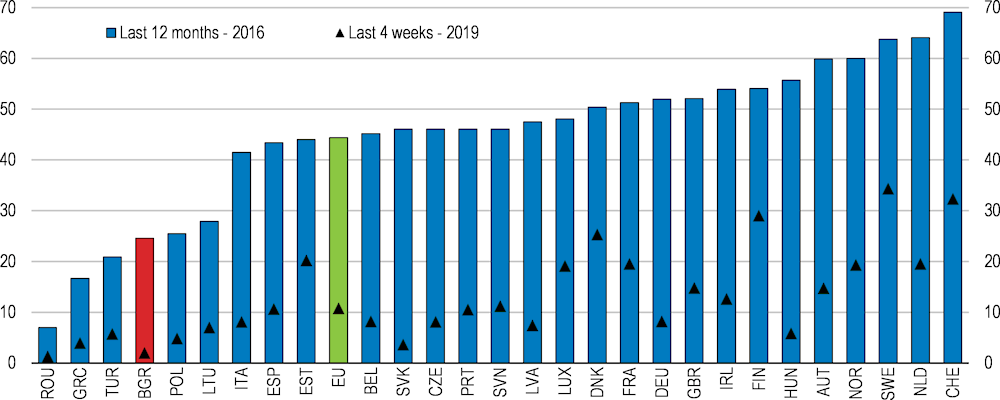

Adult learning is low

Participation in adult learning is low, which is of concern for productivity given the shrinking and ageing workforce. On-the-job and formal training can stop the erosion of skills over the lifecycle () and prepare workers for changing skills needs. Bulgaria has among the lowest participation rates in formal and non-formal education and training for adults aged 25-64 in the EU, with only 2% having benefitted in the last four weeks (2019) and 25% in the last twelve months (2016) (Figure 2.13). Participation has not increased much over time. Individuals with lower educational attainment are much less likely to participate in lifelong learning: only 7.6% of those with lower secondary or less participating in the last 12 months in 2016 compared to 22.3% of individuals with upper secondary or post-secondary education and 38.2% with tertiary education. Older workers also are much less likely to engage in learning (only 14.7% of 55-64 year olds participated in 2016).

Figure 2.13. Participation in lifelong learning is low

Participation rate in education and training, as a percentage of persons aged 25-64

Creating a culture of lifelong learning in Bulgaria is a large challenge given the low level of participation. Setting a better basis for learning early in life is a priority. The foundation for lifelong learning starts at a young age, with educational attainment being a strong predictor of the likelihood individuals will continue to learn during their working lives. Continued efforts need to be made, building on the National Strategy for Life-long Learning 2014-2020, to deepen coordination between employers, ministries, different levels of government and other relevant stakeholders. Encouraging employers to provide training and career guidance on training needs, and to give employees time to take up opportunities will be important to increase participation. Employers provide two-thirds of lifelong learning and have an important role in providing incentives to employees to participate. Adult training should be better aligned with the skills needs of employers through the incorporation of skills assessment information into programme design. Bulgaria has moved in this direction by adopting a formal mechanism to include the results of projected supply and demand of labour into the formulation of government policies.

There is a need for a training and assessment system for teachers in adult education to be set up and to increase the supply of qualified teachers and trainers (European Commission, 2019). The quality and impact of training should be assessed and quality information on courses and provides made public. One such example is the Korean Skills Quality Authority, which evaluates vocational training providers, training programmes and trainees and assigns grades based on evaluations (OECD, 2019d). Training programmes in Korea are screened for quality of inputs and outcomes and government funding is performance-based. More financing for programmes needs to be put in place in Bulgaria, which may require greater public incentives for employers, particularly in the case of SMEs. Any increased public financing should be linked to results as in the example of Korea.

There is a challenge in assessing progress in adult education and it is an area where evidence is less developed than for other education levels. The United Kingdom conducted a review of evidence on what works in further education and adult learning, and found that there is a paucity of minimum quality studies compared to the schools sector. Evidence is limited on the effectiveness of interventions, the impact on different groups and in different contexts, and there is little information on the cost-effectiveness of interventions (United Kingdom’s Social Mobility Commission, 2020). The complexity of the sector in terms of providers, learners and measuring outcomes contributes to the difficulty in evaluating programmes. The 2020 recommendation in the case of the United Kingdom is to create an independent group, a “What Works Centre,” that gathers rigorous evidence on what works for further education and adult learning for both classroom and work-based training that is then to be used in developing policy.

Fostering return migration and skilled immigration

Targeting the continued return of Bulgarians from abroad and attracting skilled immigrants provides an opportunity to alleviate skill shortages. Emigration has slowed from the high rates seen in the 1990s to the early 2010s and there are a growing number of Bulgarians returning to the country as economic opportunities have improved. With just over 13% of Bulgarian immigrants in OECD countries having tertiary education (ISCED 5 and 6), Bulgarians abroad are an important asset for the country. There is some evidence that return migrants experience difficulties in finding employment and that this can increase their incentives to migrate again (Martin and Dragos, 2012; Mintchev and Boshnakov, 2018). Policies should be deepened to attract and smooth the transition of return migrants into the labour market, and to make the most of emigrants’ contribution to economic and cultural activities in Bulgaria.

Ireland, a country with a large share of its citizens living abroad, has a number of initiatives to support emigrants thinking of returning and strengthening links with the Irish diaspora. The Citizens Information Board supports return migrants on financial issues, residency, education and getting access to social welfare services. Ireland launched its Diaspora Policy in 2015, which aims to increase links with the Irish aboard in partnership with civic society and the private sector (Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2017). Measures aim to strengthen the institutional basis for networks through, for example, arranging more structured and more frequent network meetings, and supporting Irish community organizations to achieve independently validated quality assurance standards. As well as focusing on cultural activities, part of the Diaspora programme is directed at supporting business networks and creating opportunities for emigrants to return home. The next stage includes identifying and removing barriers for those wishing to return home.

Non-Bulgarian immigrants are few and, according to NSI data, just over 13 000 non-EU nationals entered the country in 2019—a year when there was substantial skills shortages. While progress was made in the 2016 Labour Migration and Labour Mobility Act, further could be done to reduce employment restrictions, the administrative burden for immigrants and employers, and to smooth the accreditation process for vocational and educational qualifications. The example of Canada’s pre-departure services shows what can be done to smooth the transition for migrants. Canada has had these services in place since 1998 and they encompass information dissemination and orientation sessions. Needs assessments are carried out and can be used to refer future migrants to services on arrival. For migrants hoping to practice a regulated occupation, these services can advise on how to go about obtaining Canadian licensing (OECD, 2020c).

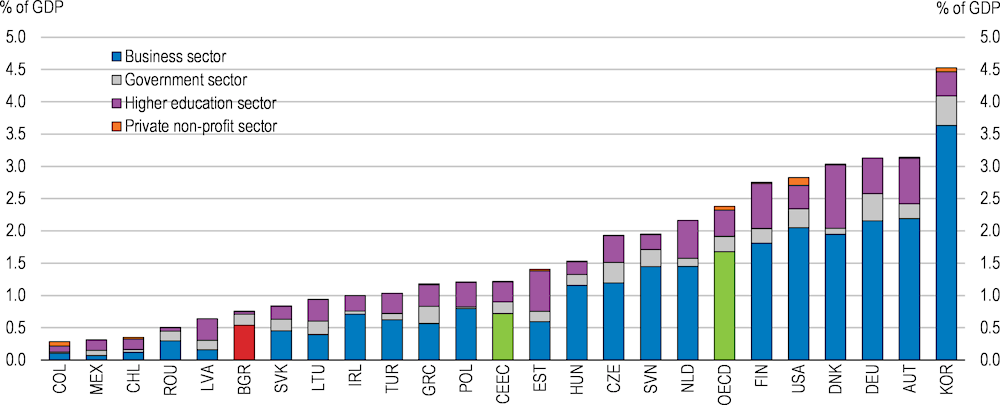

Promoting innovation

While growing, the level of innovation in the economy remains low. Bulgaria is termed a modest innovator, ahead of only Romania in the EU, in the European Innovation Scoreboard 2020, but its performance is improving and the country scored well (above the EU average) on employment in fast-growing enterprises in innovative sectors, and on intellectual assets related to design and trademark applications.. There is a low intensity of R&D in the economy: gross R&D expenditure was 0.75% of GDP in 2017 compared to spending of over 3% found in the EU countries with the highest R&D intensity (Figure 2.14). Spending has grown over time, almost doubling from 0.4% of GDP in 2007. The business sector accounts for the majority of spending (0.5% of GDP or 44% of the total), with the government spending just 0.2% of GDP. R&D expenditure in the higher education sector is the lowest in the EU at 0.04% of GDP compared to the EU28 average of 0.45%. Innovation activity of firms is low, but growing. The share of firms who reported innovation activity has increased, following a decline after the GFC, from 27% in 2016 to 30% in 2018 (National Statistical Institute).

Figure 2.14. R&D intensity is low and relies on the business sector

Gross domestic expenditure on R&D by sector, 2018

Source: Eurostat, Statistics on Research and Development database (rd_e_gerdtot); OECD, Research and Development Statistics database.

Large multinational companies are responsible for half of the business sector’s R&D spending. Bulgaria has the largest share of funding coming from abroad of all EU countries, with a 34.2% share sourced from foreign sources compared to 10% on average for the EU28. Foreign-funded R&D started to grow substantially in 2009, when its share of overall funding equalled 8.4% in 2009. It has been concentrated in “Professional, scientific and technical activities; administrative and support service activities” and in particular scientific research and development. This includes a wide range of activities such as clinical trials run in the country by foreign multinationals, EU-funded projects and foreign R&D investments in firms (Soete et al., 2015).

The underfunding of publicly-financed research and innovation, particularly in higher education, is not sustainable if the economy is to boost its research potential. The low level of public resources inhibits the development of cooperation with the private sector and is an obstacle for attracting researchers. Bulgaria had set a target for R&D investment of 1.5% of GDP as part of its European 2020 Strategy and to move towards this the country is planning to double its public research budget as part of its 2017-2030 Strategy for the Development of Scientific Research. More resources should go to recruit and retain young researchers by providing opportunities for doctoral degree holders and postgraduates given the need to renew the ageing research community. COVID-19 provides an opportunity to attract well-qualified Bulgarian and foreign talent into the sector. This will necessitate putting in place competitive salaries for researchers.

The government has begun to target research funding to public institutions based on performance. Apart from suffering from low resources, the public research and innovation system is fragmented with funding spread across a large number of universities and research institutes, which are poorly connected to enterprise activity (Soete et al., 2015). Resources should be directed to support the high-performing activities that are of most strategic relevance. Such an expansion of funding would need to be backed by strong monitoring and evaluation, where results are publicly disclosed. The trend in OECD countries has been for a rising share of public funding to go to co-operative research efforts between research institutions and industry (OECD, 2015). Directing additional funds to these activities will be vital in Bulgaria given the gap that exists between research and enterprise activity. Ties with multinational companies who are big innovators are important to exploit for national firms and researchers.

Direct support to enterprises for innovation goes beyond the scope of pure R&D, encompassing helping firms to develop new products from their R&D and to apply the results of external R&D/innovation to their in business activities. Direct subsidies are most appropriate when the objective is to target specific activities or firm types, e.g. new entrants or specific types of SMEs (OECD, 2015). Such support can take the form of grants, subsidised credits, mentoring/advisory services, government contracts or support for the development of networks or clusters. In the case of Bulgaria, there are some indications that firms that are not innovating could benefit from support to help them adopt new practices. At the firm level, support that helps with knowledge transfer could increase the innovative capacity of firms. Any allocation of direct support should be non-automatic and take place through a competitive, objective and transparent process (OECD, 2015). Selection processes need to be designed to avoid excessive bureaucracy, protect from rent seeking and ensure the highest potential firms benefit. There is zero tax relief for R&D expenditure. This is fitting given that support through tax incentives for firm innovation is less relevant in the Bulgaria case given its inconsistency with the low flat corporate tax system that has limited tax incentives. The introduction of these types of incentives could undermine revenue collection efforts.

Supporting growth of the digital economy

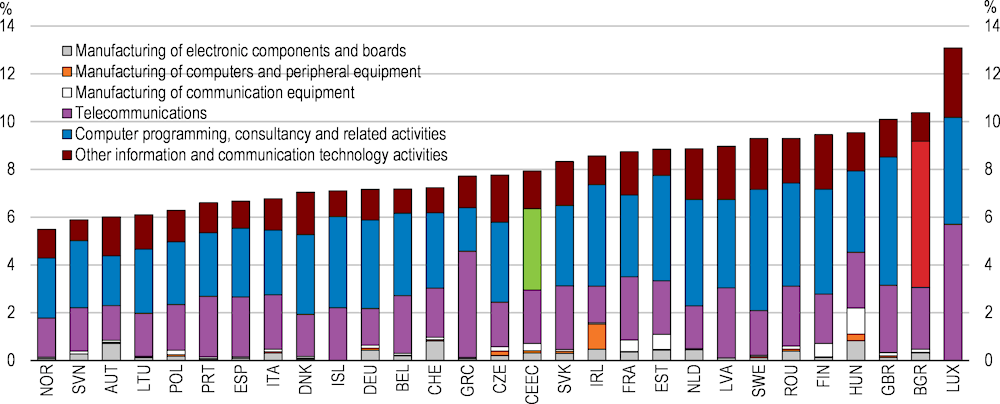

The growing ICT sector is a success story. The ICT sector is responsible for a high share of the non-financial business economy value added (10% in 2017) (Figure 2.15). Over half of this activity is in computer programming, consultancy and related activities. While it should be noted that value added activity makes up a comparatively lower share of the economy, further ICT sector growth is an opportunity for the country. Apparent labour productivity in the ICT sector is more than twice as high as the average recorded for the non-financial business economy. The sector is providing a growing number of high-paid jobs, accounting for just under 5% of non-financial business economy employment in 2017 according to Eurostat data and with an average salary in the software sector over three times higher than the national average (BASSCOM, 2019). Outsourcing activity has greatly expanded in the last decade with both major international companies like IBM, SAP and WMware, and an expanding number of domestic providers. There has been a growth in start-ups that provide digital products rather than outsourced services. A big challenge for the sector going forward is to expand the supply of skilled workers to keep up with demand.

Figure 2.15. The ICT sector is responsible for a high share of value-added activity

Share of the ICT sector in non-financial business economy value added, 2018 or latest year available

Note: The non-financial business economy is defined as NACE Sections B-N and Division 95, excluding NACE Section K.

Source: Eurostat (online data codes sbs_vna_sca_r2, sbs_na_ind_r2, sbs_na_dt_r2 and and sbs_na_1a_se_r2).

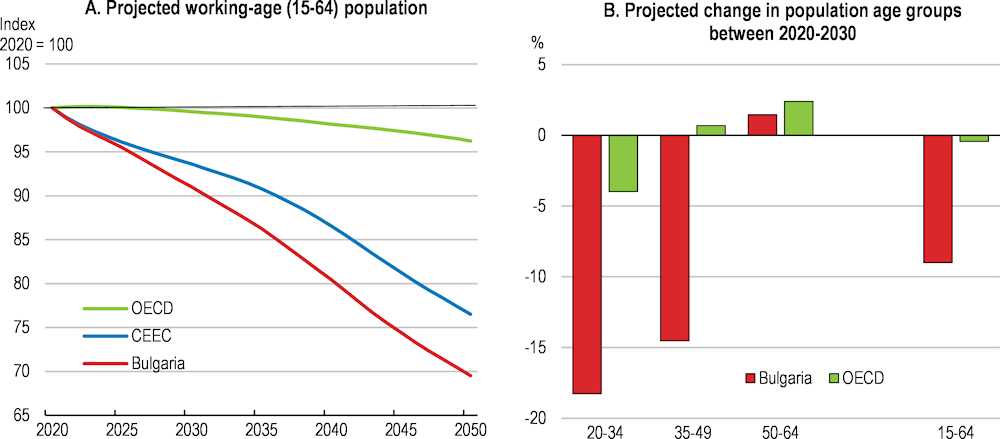

There is a stark contrast between the position of the high-performing ICT sector and that of most SMEs, which face strong constraints for participation in the digital economy. Infrastructure performs relatively well and access has been improving. According to cable.co.uk broadband speed league data, Bulgaria ranked 39th globally, out of 221 countries, in 2020. While internet access for households remains the lowest among EU member states (75%), the country has achieved the most rapid expansion in access with an increase of 42 percentage points over 2010-2019 according to Eurostat data. To build on the digital promise shown by the economy, it will be important to increase digital skills in the workforce and knowhow among SMEs. Basic digital skills of individuals are low (Figure 2.16). A small share of enterprises participate in the digital economy, for example, only 2% of total turnover generated by web sales (Figure 2.17). Increasing participation in the digital economy is an important component of increasing the resilience of the enterprise sector to withstand the turbulence created by the COVID-19 shock. Japan has implemented a support programme to assist non-high-tech firms that have difficulties accessing platforms and lack knowledge resources. This includes establishing space and online platforms for business matching, and ICT training pitched to the different digital skill levels of target companies (OECD, 2020b).

Figure 2.16. A priority is to increase digital skills

Individuals who have basic or above basic overall digital skills, % of individuals aged 16-74, 2019

Figure 2.17. Firms have a low share of e-sales

Turnover from e-sales, via web and electronic data interchange (EDI), by type of order, 2019, % of total turnover

Table 2.2. Recommendations

|

Main findings |

Recommendations (key recommendations in bold) |

|---|---|

|

Improving the regulatory framework for enterprise activity |

|

|

Competition in product markets is low, with regulatory barriers to competition that are higher than in nearly all OECD countries. |

Increase the Competition Authority’s detection and enforcement of sanctions on cartels and firms abusing monopoly/market dominant positions. Decrease regulatory barriers to entry for the legal professions. |

|

The leading role SOEs take in providing electricity, ports and railway infrastructure makes the 2019 legislative reform to improve SOE corporate governance important for the competitiveness of the economy. An important part of the reform was to establish a new centralised coordination unit to be responsible for stronger ownership coordination and monitoring of SOEs. |

Put in place the implementing arrangements for the 2019 Law on Public Enterprises for the relevant public agencies, including municipal bodies. Ensure the centralised ownership coordination unit has sufficient autonomy and resources (qualified staff, finance and institutional authority) to carry out its responsibilities. |

|

There is some evidence of limited competition in public procurement outcomes. The Public Procurement Agency has been confronting the challenge of modernising a procurement system that made limited use of electronic procedures. Assessment activities to detect illicit practices need to be increased and to rely on detailed data analysis, including from the new centralised electronic procurement system. |

Increase resources for capacity building and recruitment of key experts in the area of procurement to implement the new centralised system. Increase assessment activities to detect illicit practices. Use detailed data analysis, including information provided by the new electronic system, for increased risk-based analysis. Strengthen the reporting channels for corruption and conflict of interest, improve the complaints procedure and offer stronger protection to whistle-blowers. |

|

A lengthy and complex insolvency process results in low asset recovery. Pre-insolvency processes to restore financial viability to enterprises in out-of-court workouts are underdeveloped. |

Implement the roadmap on the insolvency framework adopted in June 2019, including the amending of insolvency legislation to accelerate and make more effective insolvency proceedings. Rapidly put in place improvements to legislation to ease access to insolvency or in the case of viable enterprise in financial difficulties to rehabilitation (pre-insolvency) proceedings. Implement complementary policies on judicial efficiency, taxation and regulation. |

|

The administrative burden for opening an enterprise is high. |

Extend reforms put in place with the operationalisation of the One-Stop Shop to cover the issuing all licences and permits, and to accept all notifications necessary to open up a business. Adopt "silent is consent" rule to speed up the approval process. |

|

Increasing skills and innovation |

|

|

Increasing the availability of skilled workers is a key priority for enterprises. Basic education is not providing a firm foundation for skills The VET system could better respond to labour demand |