Tourism has boomed in Indonesia in recent years and is already one of the main sources of foreign-currency earnings. Indonesia has rich and diverse natural assets, whose tourism potential remains underutilised. The government has an ambitious target of attracting 20 million tourists by 2019, up from nearly 14 million in 2017. The main destination will continue to be Bali. Using Bali as the preferred development model, the government wants to develop other destinations, particularly through infrastructure programmes to improve connectivity, which is a longstanding challenge for tourism as well as for regional development more generally. Enhancing the tourism-related skills of local populations will provide them with expanded job opportunities. This calls for reforms to vocational education and training. Moreover, recent efforts by the authorities to improve the business environment need to continue, including through helping firms embrace digitalisation. Tourism may be growing too fast in some destinations without adequately taking into account sustainability issues, both for the environment and local communities. Better planning and co-ordination at all levels of government and across relevant policy areas can facilitate more sustainable tourism development.

OECD Economic Surveys: Indonesia 2018

Chapter 2. Making the most of tourism to promote sustainable regional development

Abstract

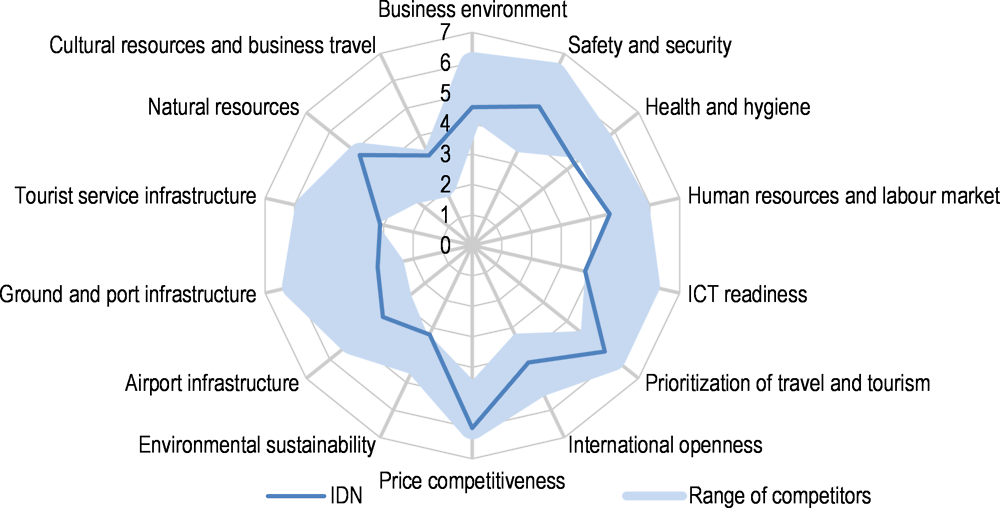

Indonesia has diverse and rich landscapes and ecosystems that position the country as an attractive destination for tourists. However, the province of Bali, with less than half of 1% of Indonesia’s landmass, has been the dominant destination, receiving half of all foreign visitors. Tourism also represents a smaller share of Indonesia’s economy than comparator countries like Thailand or Malaysia. Traditionally, Indonesia has earned most of its foreign currency by exporting primary products. Government efforts to diversify the economy towards manufacturing have proved difficult. In 2014 the new President decided to use tourism as a new pillar of the economic strategy to achieve faster and more inclusive growth. Indonesia’s competitiveness as a tourist destination improved from 70th in 2013 to 42nd in 2017, according to the World Economic Forum's Travel and tourism competitiveness index (WEF, 2017). Even so, the country still lags behind its regional competitors in a number of dimensions, particularly those related to infrastructure and environmental sustainability (Figure 2.1).

Tourism is special in that it touches many sectors of the economy including hotels, restaurants, agri-food and transport and also affects spatial development and the environment. It also involves multiple administrative levels (national, provincial, district and municipal). The horizontal and vertical nature of tourism complicates the role that governments can play in supporting the development of the industry. The Indonesian authorities expect a surge in the number of tourist arrivals in the near future, which will put pressure on infrastructure, local communities, cultural heritage and environmental assets like forests, coral reefs, beaches and wildlife. Digitalisation is also reshaping the tourism sector worldwide, which requires policy attention to ensure infrastructure and regulations are appropriate. Finally, the market is growing but is also increasingly competitive. In 2016 there were 1.2 billion international tourists, with an average annual growth rate of 4.4% since 2012 (UNWTO, 2018). Emerging economies, notably in Asia, have improved their competitiveness; for example, Thailand rose from 12th to 4th place in 15 years with regards to foreign visitor spending (WTTC, 2018).

Figure 2.1. Indonesia’s competitiveness as a tourist destination

Score from 1 to 7 (best), 2017

Note: Competitors are Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand.

Source: WEF, Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2017.

This chapter is organised into three sections. The first one summarises recent developments in Indonesia’s tourism industry and examines the government's strategy. The second section considers how tourism can improve regional development in terms of employment, infrastructure and the business environment. The last part covers the sustainability of tourism development with particular attention to the environment and local communities.

Recent developments and tourism prospects in Indonesia

Recent developments and the size of the industry

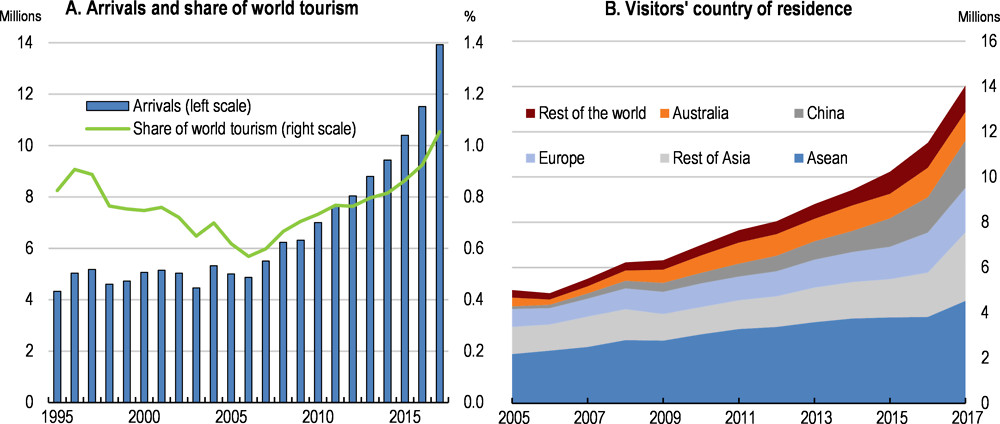

At the national level the number of foreign tourist arrivals remained around 5 million per year over 1995-2007, despite a near doubling in worldwide tourism. Since 2007 the number of international arrivals has soared, reaching 14 million in 2017 and boosting Indonesia’s market share to around 1% (Figure 2.2). The authorities aim to reach 20 million foreign visitors by 2019. Most of the recent increase has originated from Asian countries. Chinese tourists became the largest source market in 2017, surpassing Malaysia, Singapore and Australia. The tourism product portfolio is mostly culture and nature related, accounting for 95% (60% and 35%, respectively) of survey respondents’ purpose of visit (Teguh, 2017). Only a small share of tourism is related to sport or business events (5%). Within culture, “culinary/gastronomy or shopping” represents the largest share (45%) of responses, followed by “city and village tourism” (35%). Nature-based tourism is focused on eco-tourism (45%) and marine tourism (35%).

Figure 2.2. Tourist arrivals in Indonesia

A more stable and welcoming environment likely contributed to the recent growth of foreign visitors. Terrorism damaged the country’s reputation in the early 2000s; new attacks occurred in the recent past but did not specifically target tourists. In 2015 the government made visa policy changes to attract more foreign tourists. Now citizens of 169 countries do not require a visa to enter and stay in Indonesia (for a maximum period of 30 days). The free visa policy is expected to bring significant foreign exchange earnings per year, as the loss of the visa receipts (USD 35 per person) is more than compensated by the spending of additional tourists in the country (around USD 1000 per visit). In 2016 the government also legislated to allow international cruise liners to embark and disembark passengers at five seaports, which should facilitate arrivals by sea.

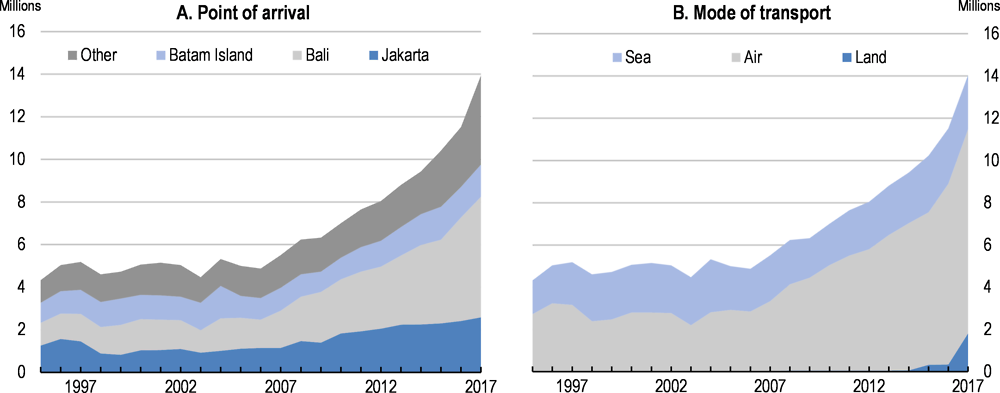

Bali remains the principal destination of foreign tourists, accounting for half of the rise in the number of arrivals over 2007-17 (Figure 2.3, Panel A). In 2018 tourists nominated it the preferred destination in Asia (TripAdvisor, 2018). Jakarta has also experienced strong growth over the same period (1.4 million additional tourists), partly driven by business tourism. Other areas (besides Batam island) also vastly increased their importance, with 2.5 million more tourists over 2007-17, and half of that growth in 2017 alone. Borobudur (Central Java) and Lake Toba (North Sumatra) are the two main new destinations. The growing importance of these new destinations can be linked to a recent government strategy to develop tourism outside Bali. As an expansive archipelago, air transport is the mode of transport used by the vast majority of inbound tourists, making effective air connectivity crucial (Panel B).

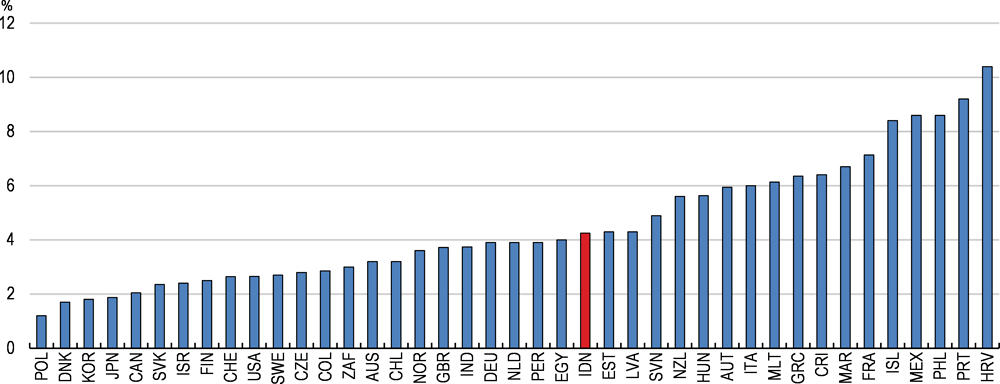

The direct contribution of tourism (domestic and foreign) to the economy, computed from the statistics office’s Tourism Satellite Account, is in line with the average for OECD and G20 countries (at around 4.3% of GDP in 2015) but lower than countries that have a focus on tourism such as Spain, Croatia, Portugal, the Philippines or Mexico (Figure 2.4). The indirect measure also includes tourism’s downstream effects. Assuming the direct and indirect effects to be of the same size (Box 2.1), the total contribution is estimated to be around 8.5% of GDP for 2015. Given that arrivals have increased by about one-third since then, the importance of tourism is likely to be higher now. Input-output tables also show that most of the value added is generated within the country.

According to UNWTO, there were nearly 120 million domestic guests in commercial accommodation in 2016, up from around 40 million in 2009. Domestic tourism is concentrated around the Muslim holiday Eid ul-Fitr (Lebaran); the authorities also increased the number of public holidays to facilitate and encourage travel. Internal movements both facilitated and were facilitated by the rapid growth of low-cost airlines (Schlumberger and Weisskopf, 2014). This will likely continue in the future with the growing middle class, the expansion of airports and the quality improvement of some airlines (no Indonesian airline was left on the European Union’s ban list by 2018). However, a domestic tourist spends about USD 70 per trip compared to over USD 1 000 for a foreign visitor (Indonesia-Investments, 2016). Thus, the economic impact of domestic tourists remains limited, and the rest of this chapter focuses on foreign tourism.

Figure 2.3. Entry points and transport mode of foreign tourists

Figure 2.4. Contribution of tourism to the economy

Direct contribution, in per cent of GDP, 2016 or latest available

Note: Direct contribution means that it only takes into account the output generated from a direct relationship between the visitor (foreign or domestic) and producer of a good or services. 2015 data for Indonesia. Data for France refers to internal tourism consumption. Data for Germany and Greece refer to gross value added.

Source: OECD, Tourism Database; Statistics Indonesia.

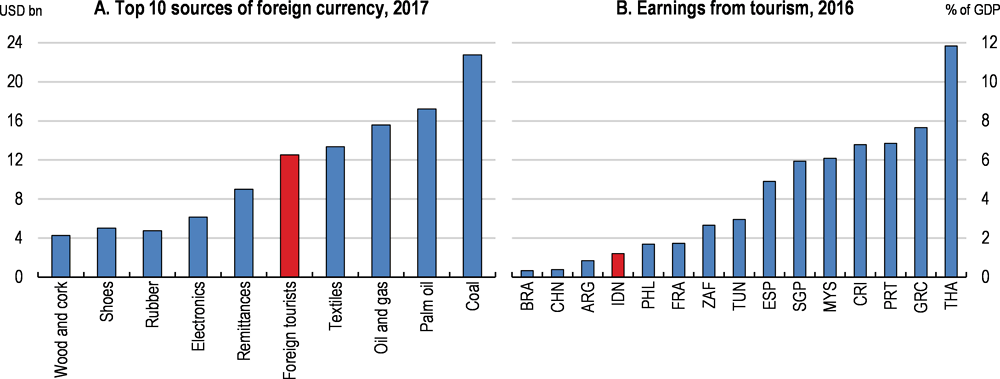

Tourism brings in substantial foreign-currency earnings, helping diversify Indonesia’s exports away from natural resources (e.g. mining and crude palm oil). Foreign tourist spending has already gradually become one of the main sources of foreign currency for Indonesia (Figure 2.5, Panel A). However, the importance of tourism exports is still much lower than for other countries (Panel B). Input-output tables show that the biggest beneficiaries from foreign tourism are hotels and restaurants (8.5% of sector output), the transportation and storage sector (1.3%), and other community, social and personal services (1.3%). Using the same approach shows that these sectors benefit much more from foreign tourism in Thailand, with tourism representing 32%, 10% and 15% of sector output respectively. To some extent, this is related to the size of the domestic economy in Indonesia. There is considerable room to attract higher spending tourists: Indonesia ranks only 12th amongst 53 Asia-Pacific countries in terms of spending per arrival (UNWTO, 2017).

Figure 2.5. Foreign-currency earnings

Note: Panel A refers to main sources of exports. Panel B uses tourism expenditure from UNWTO.

Source: CEIC; UNWTO; OECD Economic Outlook Database.

Box 2.1. Measuring the indirect economic impact of international tourism

The OECD Inter-Country Input-Output tables (ICIO) can provide new insights into the economic benefits of tourism activities by revealing the origin of value added generated by non-residents’ household expenditures within a country. The current ICIO tables describe the monetary flows, within and between countries, of intermediate and final goods and services for 63 economies and 34 industrial activities over the period 1995 to 2011.

Using ICIO tables the direct and indirect value added embodied in final demand by tourists can be estimated. The direct value is computed from the sales of final goods and services to tourists (e.g. spending in a restaurant) while the indirect contribution comes from inputs, both domestic and imported, required for those sales (e.g. food purchased by restaurants).

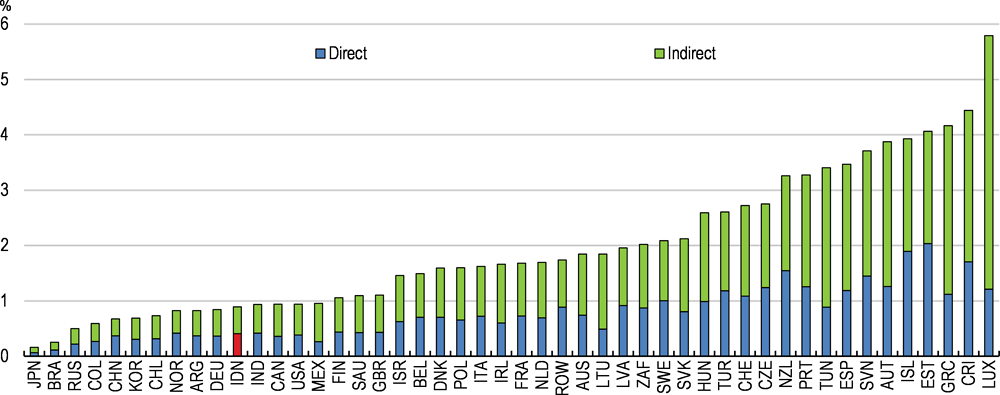

On average for Indonesia, as well as for OECD countries, around half of the tourism value added comes directly from core industries that sell directly to tourists. Those sectors produce mostly services, while most industries indirectly related to tourism (such as agriculture and food manufacturing) provide goods. The importance of international tourism trade is estimated to be relatively low for Indonesia (Figure 2.6). However given the surge in tourism since 2011, the forthcoming update of the ICIO tables will likely show a larger contribution. Domestic value added in the purchases of non-residents was around 88% in 2011, down slightly from about 91% in 1995. In Thailand and Malaysia the domestic share has decreased more substantially since 1995 (by 11 percentage points), to 73% and 66%, respectively. This high share of domestic value-added means that future growth in tourism can benefit many parts of the economy.

Figure 2.6. Foreign tourists’ expenditure

In % of GDP, 2011

Note: The direct contribution comes from the sales of final goods and services and the indirect contribution from inputs required from those sales. The indirect contribution includes both domestic and foreign value added.

Source: OECD, Input-Output Database.

The medium-term perspective

Since 2014 tourism has become one of the government’s top priorities. The National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) for 2015-19 and the accompanying tourism strategy (“Pengembangan Destinasi dan Industri Pariwisata”) set policy directions for the sector related to:

Connectivity, basic services and tourist service infrastructure;

Tourism workforce skills development and SME support;

Tourism services, international marketing and investment promotion;

Integrated destination master planning; and

Institutions and mechanisms for programme implementation.

Different planning exercises at the central government level interact, including the medium-term plan, the Long-Term National Development Plan (RPJP) and the Long-Term National Tourism Development Plan (RIPPARNAS) for 2010-25. In the latter the government selected 50 tourism destinations nationwide to be developed by 2025. Bappenas (the national planning ministry) leads the planning stage, and the Ministry of Maritime Affairs co-ordinates the implementation of tourism-related plans across line ministries. Despite a high degree of decentralisation in government, planning is largely top-down; in addition to local stakeholder involvement, it also lacks ex ante and ex post evaluations.

The objectives set out in the medium-term plan are ambitious (Box 2.2) and will depend on massive infrastructure investment (more below). The initial focus on 10 “New Balis” has thus gradually switched to four priority destinations (Borobudur, Mandalika, Lake Toba and Labuan Bajo). So far, the increase in tourist arrivals has still been largely dependent on Bali, but from 2017, other destinations started to gain importance. The target for some destinations implies an enormous increase, and it is not clear that the population and the environment can sustain such levels (more below). To reach the objectives, the government aims to attract 10 million Chinese tourists by 2019 (up from 1.6 million in 2016). The UNWTO forecasts that international tourist arrivals in the whole of Southeast Asia will increase by 5 million people per year between 2010 and 2020 and by 6 million between 2020 and 2030, mostly through an increase in intra-regional flows (UNWTO, 2017). Competition in the region may delay the realisation of the government’s target.

Box 2.2. The Government medium-term plan for tourism

The government’s medium-term plan for 2015-19 set ambitious targets for 2019:

20 million international arrivals, up from 9 million in 2014.

275 million domestic visits, up from 250 million in 2014.

8% share in GDP, up from about 4% in 2013 (using the national tourism satellite account).

Doubling of foreign exchange revenues from tourism to IDR 240 trillion (about USD 16 billion).

Increase in employment in the industry by 2 million to nearly 12 million.

Improvement in the World Economic Forum ranking of tourism competitiveness to 30th from 70th.

As part of its tourism development strategy, the government has prioritised 10 destinations for significant infrastructure development. The underlying aim is to learn from Bali’s experience as a major international tourist destination and replicate the model in destinations across Indonesia with high potential. The selection of the destinations was in large part driven by the pre-existence of a tourism industry; however, it did not take into account locations’ viability to develop as an international tourism destination including with respect to natural and cultural attractions. The need to promote geographical diversity also played a role. The 10 priority destinations are located in 10 of the 34 provinces with targets that represent sizeable increases (Table 2.1). Four destinations (Mandalika, Tanjung Lesung, Tanjung Kelayan and Morotai) have been designated as Special Economic Zones (SEZs).

Table 2.1. Tourist arrivals objectives for the 10 priority destinations

Number of people

|

2013 |

2019 target |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Borobudur (Central Java) |

227 337 |

2 000 000 |

|

Mandalika (West Nusa Tenggara) |

125 307 |

1 000 000 |

|

Lake Toba (North Sumatra) |

10 680 |

1 000 000 |

|

Labuan Bajo (East Nusa Tenggara) |

54 147 |

500 000 |

|

Morotai (Maluku Utara) |

500 |

500 000 |

|

Mount Bromo (East Java) |

33 387 |

1 000 000 |

|

Tanjung Kelayan (Belitung) |

451 |

500 000 |

|

Tanjung Lesung (Banten) |

1 739 |

1 000 000 |

|

Thousand Islands (DKI Jakarta) |

16 384 |

500 000 |

|

Wakatobi National Park (Southeast Sulawesi) |

3 315 |

500 000 |

Note: Respective provinces for each destination are in parentheses.

Source: Ministry of Tourism.

Figure 2.7. Locations of the 10 New Balis

Note: The 10 New Balis are depicted with green dots. The two current main destinations (Bali and Jakarta) are also presented.

Source: Ministry of Tourism.

The Ministry of Tourism is the lead institution for developing tourism in Indonesia. Its budget quadrupled in 2015 to IDR 1.2 trillion (about USD 80 million, less than 1% of public expenditure) mostly to improve tourism promotion (although it was cut by 30% in 2017). Marketing includes 100 Pesona Indonesia events for domestic visitors and 100 Wonderful Indonesia events for foreign tourists. WEF (2017) ranked the country’s brand strategy 47th for its level of accuracy, ahead of Malaysia (85th) and Thailand (68th). However, the campaign’s effectiveness in attracting tourists ranks only 51st, versus 7th for Malaysia and 20th for Thailand. The Ministry of Tourism bases its promotion efforts on market potential, using a weighted average of the number of tourists (40%), the previous rate of growth (30%) and total spending per visitor (30%); the latter favours Europeans because they tend to have a longer stay. At the end of 2017 this formula was prioritising spending on promotion in China, followed by Europe, Australia and Singapore. Digital tools help the Ministry to better focus its strategy (see below).

Another approach used by the authorities to grow the tourism industry is to promote events (Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and Exhibitions, MICE). Development of the MICE sector can bring benefits beyond short-term profits and jobs by adding competitive advantage to destinations and diversifying source markets. MICE can also hasten infrastructure development. In 2018 the biggest events are the summer Asian Games and the October IMF-World Bank annual meeting. For the latter Bank Indonesia estimates that the economic gain will be around IDR 5.7 trillion (nearly 0.1% of GDP), from around 15 000 delegates. The authorities have also promoted packages for attendees to visit other parts of the country. With MICE, it is crucial to ensure that the supporting infrastructure is in place and that relevant facilities are optimally utilised afterwards.

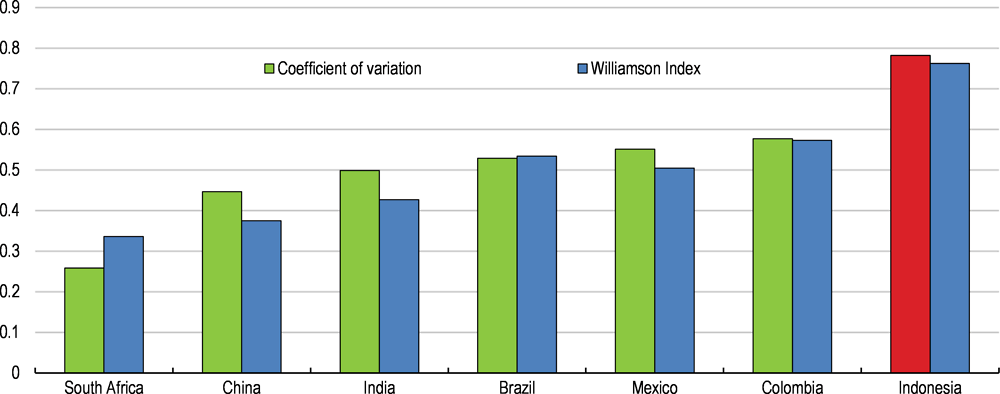

Boosting regional development through tourism

Being an archipelago of around 17 500 islands, with 300 distinct ethnic groups, is an opportunity for tourism but can be a challenge for regional development. Income inequalities persist across provinces and districts despite government policies aimed at reducing disparities, notably in terms of infrastructure investment and budget decentralisation. The variance in GDP per capita is larger within Indonesia than in other emerging economies (Figure 2.8). As discussed in OECD (2016a), disparities exist on many dimensions, including basic services like access to safe drinking water and electricity. Those differences are usually even starker inside provinces than between them. Tourism could boost some regions that are currently lagging behind and complement other policy tools aiming to reduce inequalities across the country, such as education and health care spending as well as decentralisation more broadly, as documented in the previous Economic Survey (OECD, 2016a).

Figure 2.8. Regional income inequality is high in Indonesia

Note: The coefficient of variation is unweighted. The Williamson index is a similar measure of variance that weights regions by their share of the national population. Regional GDP per capita data are for 2016 for Indonesia and Mexico, 2015 for Colombia, 2014 for Brazil and 2013 for China and India.

Source: Statistics Indonesia; OECD, OECD Regional Database; OECD calculations.

Building relevant infrastructure will be crucial for scaling up tourism

Achieving the planned growth of tourism requires substantial investment in infrastructure, notably in the area of transport connectivity. Transportation across Indonesia by road, sea and air has historically been difficult (OECD, 2016a). The government has pushed up public infrastructure investment, also supported by state-owned enterprises’ active involvement. For example, 7 airports were recently built and 8 additional ones are planned by 2019 which should expand tourism to new regions; 27 airports have also been upgraded with runway extensions. However, the profitability of some projects is low in some remote regions. While infrastructure should also take into account the needs of local communities, tourism can be one way to improve returns on relevant infrastructure.

The close interdependence of transport and tourism activities requires coherence in policy formation, notably in terms of planning. Synergies between transport and tourism can improve visitor mobility and satisfaction, and help to secure the economic viability of local transport systems by servicing both residents and tourists. At a national level, rail, road, cruise and aviation policies are usually developed within separate Indonesian agencies in relatively segregated processes, even though there are consultative mechanisms that aim to facilitate communication and co-ordination. The effectiveness of information exchange and learning across policy sectors determines how transport interests are taken on board in tourism policies and how tourism interests are in transport policies (Haxton, 2015). For example, in Switzerland, various working groups, comprised of representatives of the tourism industry, cantons, municipalities and the federal administration identify challenges and develop potential solutions around the Tourism Forum Switzerland.

Infrastructure needs are enormous compared to government funding capacity. For example, it takes about 14 hours to drive the 810 kilometres from Jakarta to Surabaya, the second largest city. Needs are also important because the population is scattered across many islands (mostly Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan and Sulawesi). Adequate prioritisation is thus key. However, the selection of public investment projects in Indonesia suffers from a lack of transparency (World Bank, 2018a). Pre-feasibility studies and selection criteria are also not systematically applied. International best practice highlights the importance of socio-economic cost-benefit analysis to improve government decision-making, even though broader impacts should also be incorporated, such as the implications for relocation and reorganisation of households and businesses (ITF, 2017). Long-lived assets are especially risky and uncertain; thus, strategic planning by the central government with clear objectives is crucial to complement project-by-project assessment. Analytical tools such as scenario-based approaches – to include finance ability, public acceptance and sustainability – are also useful to assess project quality.

The emphasis on the initial investment should be complemented by attention to the future phases of the project lifecycle, including operation, maintenance and disposal (OECD, 2017a). Poor maintenance and operation weigh on quality and durability of infrastructure. For example, Jakarta’s airport has a rating based on user reviews of only 65% compared with 80% for Bangkok and 94% for Singapore (Flightradar24, 2018). Skytrax (2018) ranks Jakarta’s airport 44th out of 100 international airports, while Singapore’s is 1st, Kuala Lumpur’s 35th and Bangkok’s 38th. Recent renovations at 12 airports should improve their quality. Road transport is also affected by a lack of proper maintenance. For example, in some provinces more than half of the roads are in disrepair due to co-ordination issues, ineffective planning and weak capacity in some institutions (OECD, 2016a).

New planned infrastructure should be built with ambitious targets of high-quality services, and existing facilities must be properly maintained to ensure their longevity and quality. Indonesia should conduct analysis of its infrastructure assets over their whole life cycle to monitor their state, as, for example, Turkey is doing (OECD, 2017a). Some government initiatives have already aimed to improve the management of roads with an asset-management system (James, 2016). In addition it is now possible to use private firms for maintenance. The government is also planning to contract out the operation of some airports, which could improve their efficiency.

Land acquisition difficulties have been the main reason for delays of many infrastructure projects. For instance, the 75km Batang-Semarang toll road was scheduled to open in 2018, but construction started in 2006, as various land acquisition issues slowed down the project; by end September the road was 88% complete (Jakarta Globe, 2018a; Kompas, 2018). Several recent government economic policy packages have sought to ease land acquisition and the granting of permits (OECD, 2016a). The Land Acquisition Law (Presidential Regulation 71/2012), effective as of 2015, was an important improvement as it limits the procedure for land acquisition to 583 days and allows for revocation of private land rights in the public interest (PwC, 2016). In addition, the State Asset Management Agency (LMAN) has been capitalised with USD 2.5 billion to finance the acquisition of land for priority projects: the costs incurred for acquiring the land are reimbursed by LMAN when construction commences. Planning, capacity building, co-ordination between the central and sub-national governments together with law enforcement all need to improve. The lack of consolidated and accepted land-tenure information would be addressed by the rapid implementation of the One Map policy (a unique cadastre for Indonesia), which was launched in late 2015 and is to be completed by 2019.

Other infrastructure also matters. For example, waste and water treatment are important to ensure the sustainability of tourism (more below). In addition, internet access is increasingly a necessity. Indonesia’s geography hampers easy deployment of optical fibre across the country, as it often implies crossing seas. The launch of Project Loom for Indonesia in 2015 may facilitate reaching remote and rural areas using balloons. However, the project appears to be making only slow progress. Some reports also point to the lack of ATMs in tourist areas; also, even when present, they often malfunction or do not accept foreign cards. In that regard, WEF (2017) reports that Thailand had twice as many ATMs per person, with 113 versus 55 per 100 000 adult population. In the end, the infrastructure needed to support significant and sustainable tourism growth is sizeable and will take years to be in place. Private investment has an important role to play. The focus of the government on four "new Balis" (Box 2.2) is a positive step, even though sustainability remains an issue (see below). Better planning will help reduce the major gaps (see below). The authorities should also continue removing hurdles for private investment, notably law and regulatory complexity, and improving the depth of local banking and capital markets.

Private infrastructure is also lacking in some areas. To accompany tourism targets, the medium-term government plan called for an additional 120 000 hotel rooms, 15 000 restaurants, 10 000 travel agencies, 300 international-class recreation parks, 2 000 diving operators and 100 marinas. To achieve these targets barriers to investment need to be removed and a more business-friendly environment supported (see below).

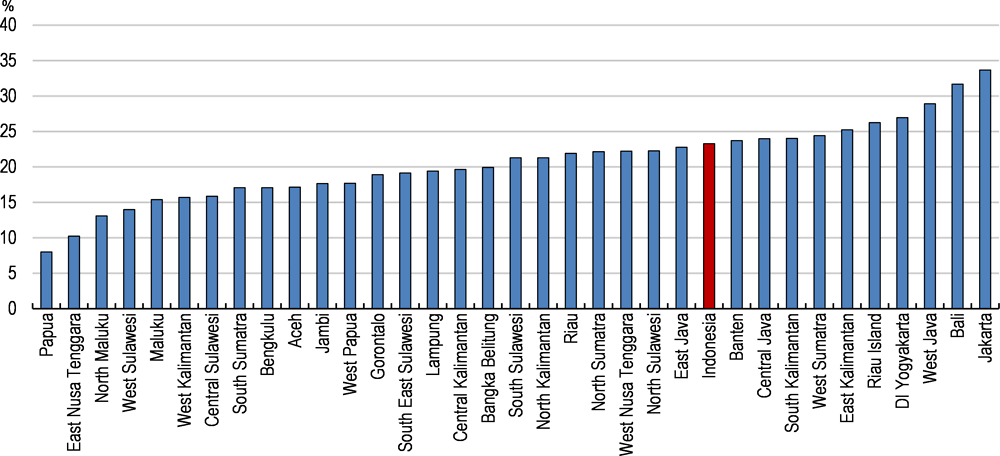

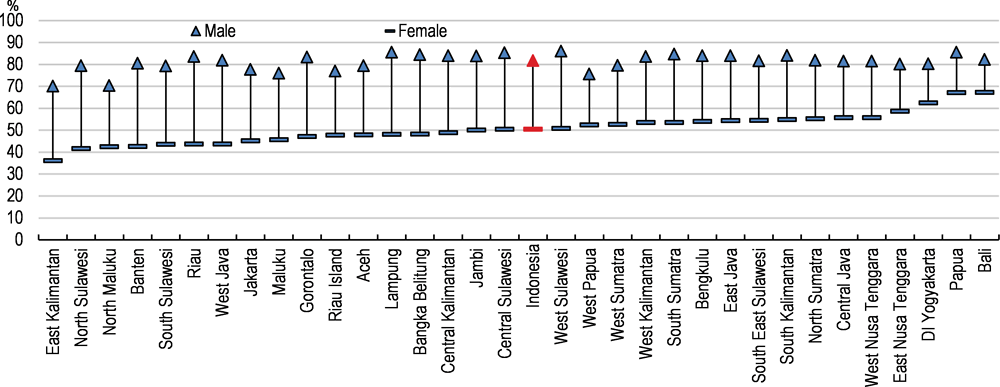

Tourism can generate employment opportunities in more areas

Statistics Indonesia produces tourism satellite accounts that indicate that tourism is labour intensive as it represented 10.4% of total employment and 4.3% of GDP in 2015 (compared to 6.8% and 4.3%, respectively, on average in the OECD). In 2016, employment in tourism-related activities increased further to reach 12.3% of total employment. Using that ratio for 2015 (employment over GDP) as a simple rule of thumb implies that additional activity in tourism will add at least twice as many jobs as an equal expansion in all sectors. The ILO (2011) also estimated that one extra job in Indonesia’s core tourism industry (hotels and restaurants) indirectly generates roughly 1.5 additional jobs in the related economy. Overall, this implies that the tourism sector has huge job-creation potential. But this potential varies across regions. Using the share of workers in hotels, restaurants, wholesale and retail as a proxy – reveals huge differences (Figure 2.9). To some extent that can be partly explained by the level of income: a richer population spends more on services. A recent study highlighted that the employment multiplier, measuring the impact of one additional unit of final aggregate demand on regional employment, for the tourism-related sector is for instance over three times higher in East Nusa Tenggara than in Jakarta (Faturay, Lenzen and Nugraha, 2017). There is an opportunity to develop tourism in areas with higher leverage on employment when such development is sustainable (see below).

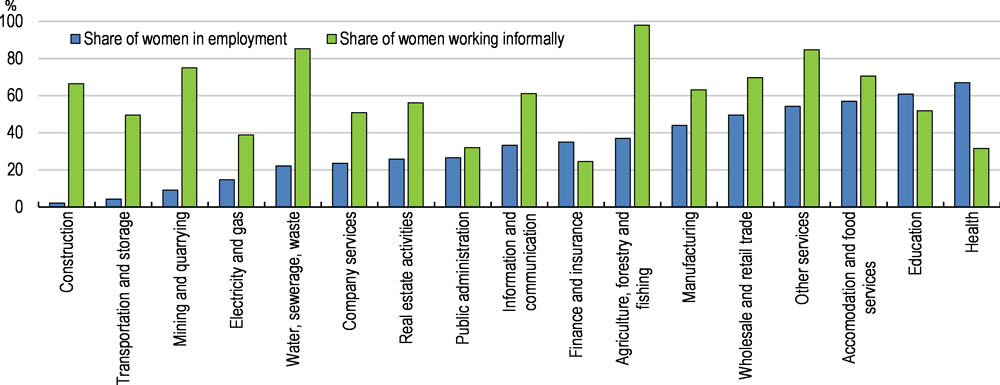

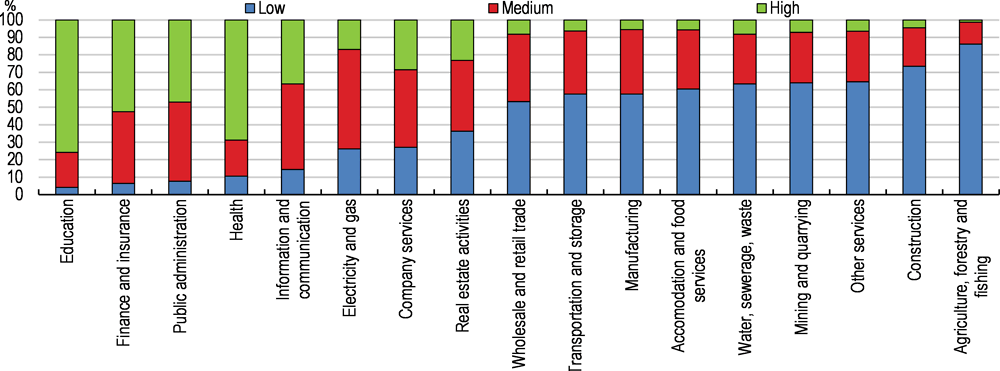

The range of skills levels available in Indonesia corresponds well to the needs of the tourism sector, as tourism-related industries employ a relative high share of low-skilled workers (Figure 2.10). In Bali, the share of high-skilled workers in accommodation and food services is much higher: 17.5% compared to 5.5% at the national level; the share of low-skilled workers is also much lower in Bali at 37% compared to 60% for Indonesia. Bali’s success in promoting higher-skilled jobs in tourism could be emulated, suggesting the potential for tourism development to not only provide job opportunities, but also to allow workers to climb the skills ladder. The sector is also well suited for women, young people and disadvantaged groups such as ethnic-minority populations (Ashley, Boyd and Goodwin, 2000). Some jobs can also be part-time and supplement income from other activities. The variety of jobs and the flexibility of the sector make it a natural and efficient tool for regional development.

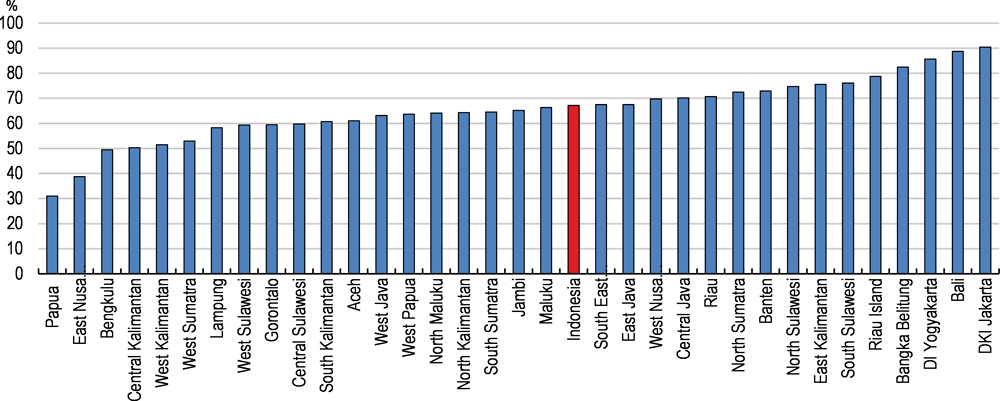

Figure 2.9. Share of employment in the wholesale, retail, restaurant and hotel sectors

By province, 2017

Figure 2.10. Educational attainment of employees across sectors

In percent, 2017

Note: Sectors correspond to ISIC Rev4 classification. Low, medium and high correspond to primary, to lower secondary and upper secondary and to tertiary educational attainment, respectively.

Source: Statistics Indonesia, SAKERNAS Database; and OECD calculations.

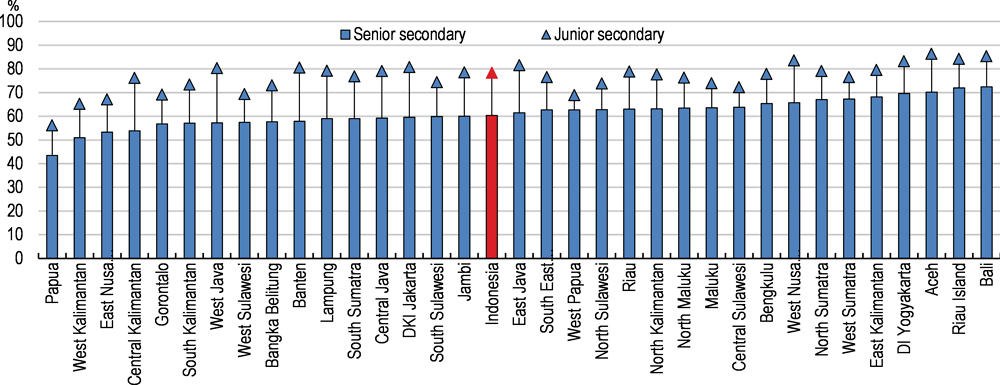

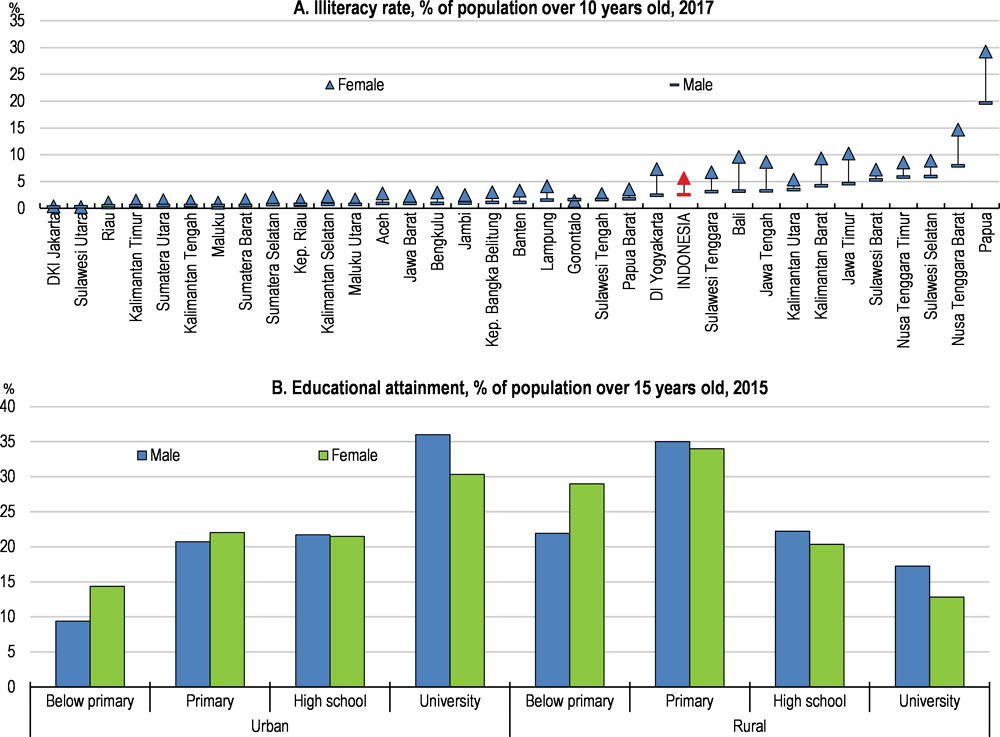

The quality of human resources is weighing on Indonesia’s ranking in tourism competitiveness compared to Singapore, Malaysia, Viet Nam, Thailand and the Philippines (WEF, 2017) (see Figure 2.1 above). This is partly related to lower educational attainment. Enrolment in primary education has improved nationwide and completion is close to universal, but stark differences remain across provinces in secondary education, likely hiding even larger disparities inside provinces (Figure 2.11). In 2016 a survey highlighted that tourism-related businesses in APEC economies have difficulties recruiting staff because they lack a proper education (APEC, 2017). As recommended in the previous OECD Economic Survey, improving the quality of secondary education, especially in some provinces, is essential for providing the necessary skills to give all regions the wherewithal to continue to boost living standards. Introducing regular teacher evaluations and a remuneration with stronger links to performance and training could help to improve quality. Better pay has made teaching more attractive; this should be used to strengthen selection into teacher training programmes so that over time retiring teachers are replaced by increasingly committed and competent teachers. Moreover, by improving basic competencies, more Indonesians will be able to upgrade their skills throughout their adult lives.

Figure 2.11. Net enrolment ratio in lower secondary schools

By province, 2017

Going forward, there could be massive numbers of vacancies for various positions in tourism and intense global competition to recruit workers with necessary competencies; however, there are no official reports on the sector’s current labour needs in Indonesia. The large tourism workforce in Bali is sometimes used to provide missing skilled workers, but training the local population would be preferable in the medium term. The authorities should promote the monitoring of shortages and give the education system enough flexibility to adapt curricula and class sizes quickly. This could be facilitated by setting up a national information service beyond the tourism sector that provides up-to-date labour market information for all involved parties including students and teachers (OECD/ADB, 2015). Such a system can take the form of a website providing trends in demand and supply by occupation, industry and district, complemented with skills shortages and surpluses. Information on occupation remuneration and requirements in terms of qualifications and experience could also contribute to increase the flexibility of the system. For example, ministries of education and labour in Peru provide data on the cost and employment outcomes at all higher-education institutions (McCarthy and Musset, 2016).

It is crucial to involve local communities more heavily in the development of tourism and eventually contribute to improving the matching between job opportunities and the skills of the local population. The government has launched several higher-education institutions specialised in tourism close to major tourist destinations. The government is now developing vocational higher-education institutions in Lombok, Medan and Palembang where there is evidence of skill shortages. There are plans to build similar institutions in Kalimantan, West Papua and Manado. There are also some specific projects like WISATA (with support from Switzerland) that aim to develop tourism education at vocational schools in some regions (Swisscontact, 2016). Nevertheless, co-ordination and capacity issues in Indonesia are slowing down progress in that direction. More consultation and collaboration with local authorities would help them to build their capacity to implement and monitor education reforms (OECD/ADB, 2015). One complementary solution could be to have a centralised pool of teachers and curricula to send directly to priority destinations. The Egyptian Tourism Workforce Development project, which aims at providing better levels of service and food safety in 12 tourism regions, addressed similar constraints by using mobile hospitality master trainers (Stacey, 2015).

Further investment in vocational education and training (VET) is important to meet the growing needs of the tourism sector. Indonesia has one of the highest rates of secondary school VET enrolment, with 45% of upper secondary students enrolled in VET in 2015, up from 20% in 2005 (ADB, 2018). However, the authorities should better monitor these schools, including private ones (as they are the major providers of education and training in tourism) since employers report that many graduates lack relevant skills (Kadir, Nirvansyah and Bachrul, 2016). Setting up regular retraining programmes for teachers would reduce the shortage of high-quality vocational teachers and lecturers. Training new and adequate teachers will become increasingly important to accompany the growth of the tourism sector. VET is also more expensive than academic education in Indonesia (at least twice as costly), which means that spending efficiency should be improved (OECD, 2016a). The government could introduce tools to measure activities to allow for benchmarking (OECD/ADB, 2015).

Tightening the relationship between firms and the education system could allow early detection of skills shortages and improve course content in VET. Brazil’s experience with Pronatec – a publicly-funded programme that supports private and public vocational training courses – could provide useful insights. That system is more flexible because it is outside the main education system and tries to link training places in each region with skills needs using explicit requests from individual businesses (O’Connell et al., 2017). The Indonesian government is committed to promoting more vocational training and aims to train 1 million students in 2018 notably by having schools and firms signing agreements. This should benefit tourism too. The authorities should also promote work placements as a way to improve the school-to-work transition. Further developing on-the-job training is also crucial to allow for career progression and new technology adoption.

There are currently not enough incentives for employer involvement in tourism-related VET (Kadir, Nirvansyah and Bachrul, 2016), notably because the sector relies heavily on casual and temporary staff (Stacey, 2015). The focus is then more on initial skills provision rather than on up-skilling. One particular issue with the involvement of firms in VET is the fear that trained people leave the firm or the area after completing training. There could be more information to employers on the benefits of skills development for service quality and competitiveness. A tax incentive for providing training is also planned.

In the tourism sector mastering foreign languages is particularly important. For example, because of the language barrier Singaporeans tend to prefer Malaysia as holiday destination rather than Indonesia (Indonesia-Investments, 2016). English is important, but given that the country aims to attract more tourists from China, Mandarin training courses should also be further developed, especially in areas where China is a large and growing source market.

The use of foreign workers could be facilitated to help mitigate near-term skills shortages. The 2012 ASEAN mutual recognition agreements ease the procedure to recruit foreign tourism experts. More advertisements of that agreed procedure could encourage firms to use those opportunities more, for example to attract English-speaking Filipinos or Malaysians. The recent initiative, led by Indonesia, that facilitates mutual recognition of skilled workers amongst the members of the Organisation for Islamic Co-operation is also welcome (OIC, 2018). In addition, there are costs implied by migration, which are particularly high in APEC economies, notably due to fees charged by agents, intermediaries, travel agents and officials that are involved in the recruitment process. This represents a barrier to recruitment and reduces the demand for migrants (APEC, 2017). The government should promote and ease foreign migration as a tool to mitigate shortages of high-skilled workers in the tourism sector in the near term.

Improving the business environment to boost entrepreneurship

The tourism industry is characterised by the importance of micro and small firms: on average in OECD countries nearly half of all employees in accommodation and food services work in firms with 1-9 workers (nearly 60% for Turkey) (Stacey, 2015). A stable and conducive business environment can enable quick and robust growth in the number of firms in the tourism industry since not much capital is required. The environment in Indonesia has improved vastly: the 2015 World Bank Enterprise Survey shows that the average time to obtain an operating licence was reduced from 21 days in 2009 to just 6 in 2015 and is now much lower than the average for East Asia and Pacific (19 days) and lower-middle-income countries (22 days). Similarly, Indonesia's Ease of Doing Business ranking has improved considerably from 122nd in 2010 to 72nd in 2018. However, some issues remain and drag down its relative position; for example, even if getting an operating licence has become easier, starting a business and enforcing contracts are still complex (Table 2.2). Effective regulations are important to support tourism, especially regarding health and safety conditions in hotels, restaurants and transport.

Table 2.2. Ease of doing business

Ranking in 2018

|

Malaysia |

Thailand |

Viet Nam |

Indonesia |

China |

India |

Philippines |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aggregate rank |

24 |

26 |

68 |

72 |

78 |

100 |

113 |

|

Starting a business |

111 |

36 |

123 |

144 |

93 |

156 |

173 |

|

Construction permits |

11 |

43 |

20 |

108 |

172 |

181 |

101 |

|

Getting electricity |

8 |

13 |

64 |

38 |

98 |

29 |

31 |

|

Registering property |

42 |

68 |

63 |

106 |

41 |

154 |

114 |

|

Getting credit |

20 |

42 |

29 |

55 |

68 |

29 |

142 |

|

Protecting minority investors |

4 |

16 |

81 |

43 |

119 |

4 |

146 |

|

Paying taxes |

73 |

67 |

86 |

114 |

130 |

119 |

105 |

|

Trading across borders |

61 |

57 |

94 |

112 |

97 |

146 |

99 |

|

Enforcing contracts |

44 |

34 |

66 |

145 |

5 |

164 |

149 |

|

Resolving insolvency |

46 |

26 |

129 |

38 |

56 |

103 |

59 |

Note: Countries are ordered by the aggregate ranking. Indonesia’s ranking is based on Jakarta and Surabaya.

Source: World Bank, Ease of Doing Business Database.

The authorities are developing some tourist destinations as Special Economic Zones (SEZs), which removes the local government’s administrative burden. Amongst the 10 priority destinations, only some will be SEZs. In practice, SEZs can compete with another part of the same province for the same industry, potentially generating significant distortions. There is a risk that using SEZs bypasses the spirit of decentralisation and disconnects local governments from economic development in their areas. The previous Economic Survey argued that SEZs could serve to pilot new regulations, notably related to employment, but so far no such experimentation has taken place (OECD, 2016a). In parallel, to remove the need for SEZs, local governments should continue easing the administrative burden. To that end, the launch in June 2018 of the online single-submission system for all licensing and permits is most welcome even though its implementation is still in train. It is crucial that implementation be evaluated to ensure that it works well. More specifically related to tourism, the authorities could designate a central contact person in the government to assist proponents of significant tourism investments, as done in Australia (OECD, 2018a).

A more dynamic business environment would allow new linkages across different sectors to emerge more easily, for instance connecting farmers with restaurants, hotels with restaurants and transport (taxis, buses, boats) with accommodation. More information to tourists could also increase their satisfaction and create more opportunities for the sector. The integration of tourism activities in domestic value chains can foster activity and productivity. Bundling attractions and services together can increase visitors’ spending by providing diverse tourism services and encouraging longer stays and facilitating access to local culture, which is the primary purpose for around 60% of visitors (see above). One way to achieve this is to improve tourist information and service centres, which rank poorly (96th) in the WEF (2017) tourism competitiveness indicators. Tourist information centres are a hub for reliable information and offer local knowledge to create packages. Financing for information centres could come from local government, visitors and local firms. Extra services could complement the trusted standard information for visitors, for instance ATMs, local artists’ exhibitions and free Internet. In Australia tourist information centres have been shown to extend the time and money spent by visitors who appreciate local content (Ballantyne, Hughes and Ritchie, 2009). Districts could create such centres with provincial co-ordination and promotion on provincial websites.

Another approach is to encourage the expansion of the creative economy. In tourism, creative industries are knowledge-based activities “that link producers, consumers and locations by utilising technology, talent or skill to generate intangible cultural products, creative content and experiences” (OECD, 2014a). The creative economy can help offer new products and services for new target groups away from conventional models of environmental or heritage-based cultural tourism: that can be through unconventional media advertisements, arts creation in a specific building, and sound-and-light shows. Increasingly visitors are looking for experience-based, instead of destination-based, tourism. However, in Indonesia, the tourism-related creative economy mainly exists in the more service-based Javanese and Balinese economies, as they have access to a more highly educated workforce (Fahmi, Koster and van Dijk, 2016). Other places can leverage the diversity of their cultures and use a more traditional approach to attract visitors. Local governments can provide a platform – which can be a tourist service centre – to exhibit local arts and crafts, products and services.

Access to finance for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) has improved across the board, notably driven by the KUR programme and the recent regulation requiring banks to dedicate at least 20% of their business loans to SMEs (OECD, 2018b). That can spur more start-ups and business dynamism in the tourism sector, of which the great majority are micro and small enterprises. However, banks holding more risk may increase lending interest rates in response. The lack of collateral and seasonal nature of tourism often drives difficulties for small enterprises seeking bank lending, all the more so given high rates of informality and extensive use of cash, which prevent many people from building a credit history. Indeed, in 2015 66% of SME business investment was financed by internal resources (ibid). In addition to the establishment of a collateral registry, a recent regulation by the banking regulator (OJK) requires banks to concentrate on business revenues in the loan decision-making process in the absence of collateral, while sub-national government entities offer guarantees to compensate for any such absence. However, further clarifying land property rights and developing credit bureaus would also be beneficial.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) could complement domestic capital to grow the tourism industry more quickly, given the sizeable investment gap. Foreign investors in the tourism sector can be more robust and stable than their domestic counterparts as they have more capital and experience (UNCTAD, 2007). FDI can also bring in new technologies and skills, including advanced management, environmental and financial systems. Foreign firms often generate proportionally more employment than local ones and tend to offer higher wages as on average they offer higher-quality services (ibid). However, restrictions to FDI in Indonesia remain relatively high compared to similar countries, as the negative investment list restricts foreign equity in certain sectors (OECD, 2016a).

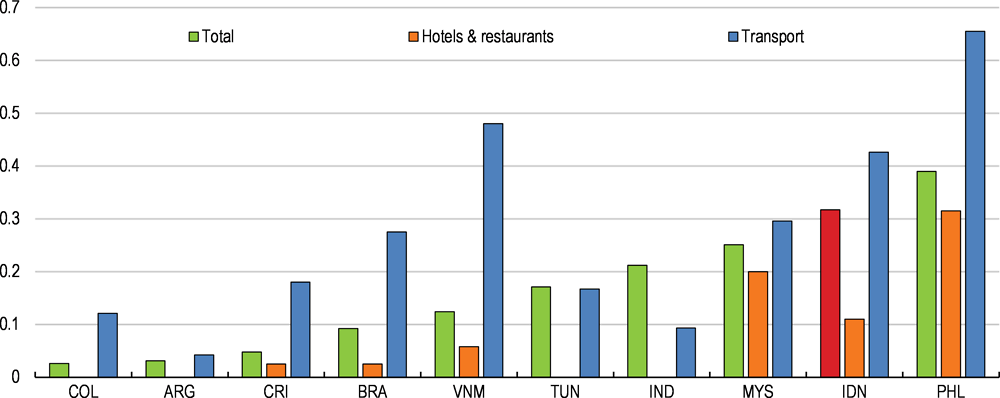

Constraints on FDI are particularly significant in the transport sector and less so for hotels and restaurants (Figure 2.12). Foreign land ownership restrictions also put constraints on the development of hotels and restaurants although a right to build can be issued to foreign companies for 30 years (renewable for 20 years). Those in turn affect the development of tourism. For example, foreign ownership of airports is limited to 49%. In practice, none of the existing airports has any private capital, even though the President of Indonesia expressed interest in their privatisation. In the example of the recently constructed Kertajati airport, a regionally owned enterprise (PT BIJB) is participating in the project, illustrating a new approach with co-operation between the different levels of government and an enterprise (Jakarta Globe, 2018b). The development of airports could be faster if more foreign private investors were encouraged to participate, including by further revising the negative investment list. Removing limitations on foreign land ownership would also facilitate FDI.

Figure 2.12. Restrictions on foreign direct investment across emerging market economies

FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index from 0 (open) to 1 (closed), 2017

Note: The FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index measures statutory restrictions on foreign direct investment across 22 economic sectors. It gauges the restrictiveness of a country’s FDI rules by looking at the four main types of restrictions on FDI: 1) foreign equity limitations; 2) discriminatory screening or approval mechanisms; 3) restrictions on the employment of foreigners as key personnel; and 4) other operational restrictions, e.g. on branching and on capital repatriation or on land ownership by foreign-owned enterprises.

Source: OECD, FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index Database.

Firms in the tourism industry also face challenges with respect to taxation (Chapter 1). The administrative burden discourages firm registration. A turnover tax, introduced in 2013, aims to ease the burden for small firms, but the regime could focus more narrowly on very small firms, linked to additional non-financial support to encourage their participation. Many services are subject to a withholding tax on total revenue if the client elects to use this option. Tax from rental incomes, for instance through the sharing economy, is always fixed at 10%, whatever the person’s income situation. Hotels and restaurants are exempted from the value-added tax (VAT), but pay a local sales tax usually at the same rate. That means that they pay more tax than with a VAT system as VAT is included in their inputs. In practice compliance rates are low. The tax regime would improve by shortening the list of exemptions. Merging the regimes into a fair and simple tax system would make compliance easier. Compensation through transfers for the sales tax would avoid a loss of revenues for local governments (Chapter 1).

Reaping the benefits of digitalisation

Digitalisation is a global phenomenon affecting all industries, including tourism. It changes the ways of doing business even for traditional players, including via the convergence of networks, the increasing connectivity of devices and changes in social interaction (OECD, 2018c). Some estimates evaluate the resulting gain for Indonesia at about 10% of GDP over 10 years (Das et al., 2016). The process of digitalisation as it applies to tourism is already well underway and provides tourism operators with direct access to international markets and customers. In Indonesia 80% of tourists use digital media to search destinations and share their experiences (ITX, 2018). One of the most visible changes is the development of online travel agents and digital platforms that intermediate between customers and providers like hotels, restaurants or taxis. Ongoing digitalisation of many other sectors – logistics, transport, culture, retail, finance – is also affecting the tourism sector, such as through cashless payments.

Digitalisation is an opportunity to attract more visitors, to increase competition, and to create jobs (OECD, 2017b). The growth of the digital economy challenges regulators to balance stimulating innovation and promoting tourism against the need to protect consumers and ensure a level regulatory playing field for traditional businesses (OECD, 2016b). Through digitalisation new products and services are created to expand supply. One case in point is the sharing economy; that is, the temporary sharing by individuals of what they own (for example, their car or their house) or do (for example, making meals or providing excursions). It establishes a direct connection between visitors and the local population, which can foster a feeling of ownership of tourism development. When such products or services meet demands that were not satisfied, the economic effect is undoubtedly positive. Some of them are developing only slowly, however, as Indonesia sometimes lacks the relevant facilities. For example, mobile payments are developing fast internationally, with 65% of Chinese tourists using them during overseas travel in 2017 (Nielsen, 2018) but their availability is still lagging in most of Indonesia.

Digital platforms are an example of one area developing particularly quickly: in 2017 Airbnb's 11 200 hosts received a median income of USD 2 100 (which is similar to the median income in Thailand and above that in the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam), adding up to a total of USD 85 million (Airbnb, 2017). The 900 000 guests represented a 69% increase over 2016. Airbnb is also estimated to have supported 48 100 jobs in 2016 across three Indonesian destinations – the highest for the firm amongst the 21 APEC countries excluding the United States (ibid). The government should work with digital platforms on how tax compliance can be best assured, looking at examples in other countries such as India.

Foreign and domestic tourists’ use of the Internet is increasing rapidly, notably via mobile phones. It provides a strong argument for the expansion of infrastructure to offer similar service in tourist areas as in major cities – with benefits flowing to local residents as well as visitors. Notably, better reach and reliability of 4G technology would be beneficial as well as investing in 5G technology. In many destinations the uptake of digital technologies by tourism businesses and the provision of basic features, such as online booking and payment facilities, are limited by the available infrastructure and the necessary skills to fully reap the associated benefits. Their usage is unequal around the country. According to the Indonesia Internet Service Providers Association, nearly 55% of the population used the Internet in 2017, with a large gap between urban (72%) and rural areas (48%) (APJII, 2017). The gap is a sign of demand weakness but also supply constraints, which weigh on regional development. To alleviate inequality the government committed to offer fixed broadband with speeds of at least 2 Mb to all government offices, hotels, hospitals, schools and public spaces by 2019 (Andrews et al., 2018). That is welcome and can generate spillovers to surrounding areas. Wireless broadband internet can be easier to deploy in remote locations. As this expands it will reduce the gap between rural and urban areas.

More competition in the telecommunications market would encourage innovation, expand supply and hold down retail prices. According to the OECD’s product market regulation indicators, competition in the telecommunications sector is limited; Indonesia has the most restrictive environment across all countries covered (Koske et al., 2015). The sector is highly concentrated with the largest company having more than half of the market share. The degree of public ownership is also relatively high. Regulatory restrictions, notably in the number of competitors, further limit competition. Lifting entry barriers and reducing government influence over PT Telkom Indonesia could encourage new entrants and greater innovation.

The Indonesian government was an early adopter of digital information systems to promote tourism. The Ministry of Tourism dedicated 30% of its 2016 budget to digital promotion with an objective of reaching 50% (Tempo, 2017). The Ministry has developed a digital dashboard to monitor Indonesia's tourism reputation on social media on a daily basis (at national and destination levels). The system compares the country with its nearby competitors to assess its relative performance. In addition, mobile positioning systems are utilised to monitor the number and distribution of tourists. This information allows decision makers to better understand visitor flows and perceptions, respond to issues as they arise and make better informed marketing decisions. In 2016 the Ministry launched Indonesia Travel X-Change (ITX), a business-to-business platform that helps connect sellers of tourism products and services with buyers (travel agents). The system provides a booking and online payment system plus analytical tools, and eases communication between sellers and buyers (Nurdin, 2018). However it is still being developed and manages only 2 270 rooms in 28 destinations. The platform should be finalised quickly and advertised more widely.

Digitalisation and the need to be visible to potential customers can also foster the formalisation of tourism-related businesses. Excessive bureaucracy tends to increase the share of the informal sector. The authorities could develop and promote online mobile applications for easing administrative tasks, for example to file income tax and VAT (Chapter 1). Initiatives such as the one by Bank Indonesia to create a mobile application (SI APIK) for small firms are welcome: standard and validated accounts and various financial reports, for example, are now much easier to produce for companies whose managers have low numeracy skills. Other applications could be developed, such as for paying local licence fees.

Ensuring growth in tourism is sustainable

Indonesia committed to achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which include eradicating poverty, improving health and education, achieving gender equality and protecting environmental assets. The development of tourism can directly contribute to all of the SDGs and especially in: “decent work and economic growth” (goal 8), “responsible consumption and production” (goal 12) and “life below water” (goal 14) (OECD, 2018a). Good policy planning is also important to preserve environmental assets.

Tourism and the environment are deeply interconnected

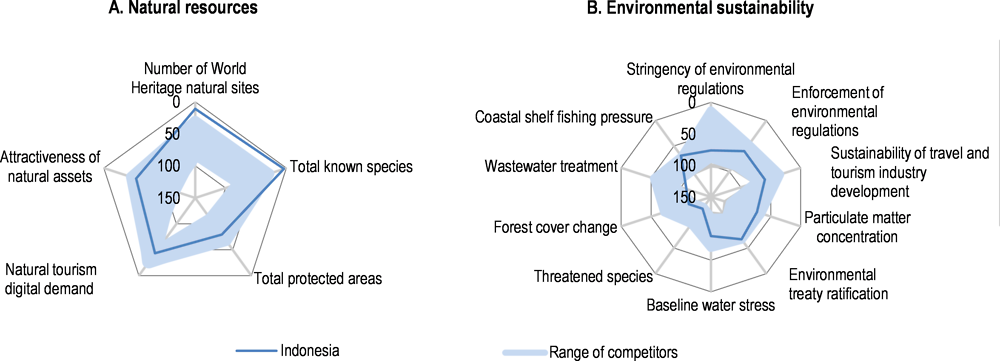

Indonesia’s tourism competitiveness is boosted by its exceptional natural resources: it ranks 14th of 136 countries (WEF, 2017), not least thanks to its five Natural UNESCO World Heritage Sites and the sheer number of its known species (Figure 2.13, Panel A). However, Indonesia’s overall competitiveness is dragged down by its dismal overall score on environmental sustainability, which leads to its ranking of 131st (see Figure 2.1 above). This poor performance is broad-based across measures of environmental sustainability but driven by the situation of threatened species, the change in forest cover and lack of wastewater treatment (Figure 2.13, Panel B). It is crucial that alterations to natural assets are valued against their potential use, including as a tourism asset. For example, forests and peatlands destroyed with man-made fires to clear land for plantations entail losing much more than only trees and grasses but also the economic returns from their sustainable use. The public value of those assets is higher than the private returns because of externalities and the fact that private actors are not bearing the cost. Given that those fires are prohibited, law enforcement should be stepped up, and campaigns should provide information about the economic loss from the associated environmental damage.

Figure 2.13. Components of tourism competitiveness related to the environment

Ranking out of 136 countries, 2017

Note: Competitors are a simple average of Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand.

Source: WEF, Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2017.

Sustainably developing tourism must take into account the impact of its growth on the environment. Uncontrolled tourism can have a range of negative impacts, including: depleting water resources (especially fresh water); changing land use and degradation; using local food, energy and other raw materials that may already be in short supply; generating air pollution and noise through increased transport; increasing solid waste, litter and sewage; creating aesthetic pollution; and other physical impacts such as construction activities, marina development, anchoring and other marine activities. That points to the need for assessment and monitoring of the environmental situation in each tourist destination, with for instance more involvement of the five Sustainable Tourism Observatories in Indonesia (a global network under UNWTO). In some cases, that would lead to mitigation plans to counteract the degradation. Conversely, tourism, if developed strategically, also has the potential to contribute to environmental protection and conservation. For instance, by raising awareness of environmental values it can serve as a tool to finance protection of natural areas and increase their economic importance.

Most of the expected increase in the volume of tourists will take place in few destinations. Thus, environmental pressures in these locations will be sizeable. For instance, sanitation services are already inadequate (Figure 2.14). In Bali, average daily water consumption per person is 60 litres in rural areas and 120 litres in cities, but tourists consume up to 200 litres, and capacity is already insufficient (Bali, 2015). Meeting the target for visitor numbers could degrade the natural environment, reducing future benefits from tourism. Growing pressures on the environment from mass tourism are already forcing some countries to shut some tourism destinations, at least temporarily. For example, the island of Boracay in the Philippines (which received 2 million visitors in 2017) is being closed for six months in 2018, and direct boat access to Maya Bay in Thailand is forbidden from June to October 2018 (Jakarta Globe, 2018c). To raise the sustainability of the sector, medium-term planning should gradually refocus on increasing yield rather than numbers of tourists. That also means improving the availability and quality of data to allow accurately gauging such targets. As in New Zealand, the government could also have a fund to support some areas that face pressures from tourism growth and are financially constrained (OECD, 2018a).

Figure 2.14. The coverage of sanitation services is low in many areas

Basic and safely managed sanitation coverage by province, in per cent of the population, 2016

Infrastructure projects that raise the number of visitors should be accompanied by other investment needed to support environmental sustainability. For example, when building a new airport that will bring hundreds of thousands of additional tourists, the capacity of waste and water treatment systems should also be raised, all the more so as foreign visitors are especially heavy users of water and producers of waste (Messenger, 2017). According to the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, 48% of the 61 million tonnes of waste produced in 2016 in Indonesia was sent to (mostly non-sanitary) landfills and 29% was unmanaged. Indonesia has become the second-largest contributor to plastic marine pollution with 80% of marine waste coming from improperly disposed waste from land. Coral reefs are consequently the most littered by plastic in the Asia-Pacific region (Lamb et al., 2018), potentially affecting the tourism experience. That suggests the need for appropriate integration of medium-term strategies and sustainability objectives into the plans for all infrastructure projects. An excise tax on plastic bags is planned and would indeed contribute to reduce waste and marine pollution. Introducing a deposit and collection scheme for water bottles would reduce plastic pollution.

Sustainable tourism development will require the integration of responsible consumption and production practices in the sector. Programmes already exist that aim to change tourists’ behaviour in terms of water by encouraging guests in hotels to re-use towels rather than have them washed daily, for example. These should be intensified. Good examples of other private-sector initiatives include the lead taken by Chile’s tourism association, Fedetur, to develop projects that aim to reduce energy consumption and CO2 emissions from tourism, and the development of carbon calculators for tour operators and travel companies by the Tourism Institute of Bogota in Colombia. In the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, the government provides advice, training and financing to promote green energy (OECD, 2018a). Companies could benefit from such actions, which not only lower their energy costs but enhance their reputations as environmentally friendly operators and attract new customers. More important is to adopt the polluter-pays principle. For example, wastewater discharge monitoring should be stepped up with appropriate fees levied. Likewise, charges for water extraction and supply can help to control water demand and finance new treatment facilities.

There are many opportunities to make better use of environmental assets to attract more visitors while ensuring their preservation for the benefit of future generations. For example, Indonesia is home to 17% of the world’s wildlife species but is not protecting them well enough, as evidenced by the megafauna conservation index, which ranks it only 89th (Lindsey et al., 2017). Less than 12% of land is protected, which is low relative to other countries (see Figure 2.13 above). Indonesia should intensify the protection of forests and wildlife by increasing the share of protected areas. This will be also contribute to preserving landscapes. In addition, public access to the vast majority of protected land is restricted, much more so than in most other countries (Mackie et al., 2017). Greater efforts are needed to improve the management of protected areas; in 2011 nearly all national parks failed to reach their conservation objectives (Bappenas, 2016).

The Ministry of Environment and Forestry’s 2015-19 medium-term plan includes a specific target of 20 million visitors in conservation areas by 2019, of which 1.5 million would be foreigners. When the area can tolerate tourism activity, visitors should have access. User fees should be introduced and be set high enough to pay for the cost of basic infrastructure, maintenance and conservation, and the number of visitors to sensitive sites should be limited (Box 2.3). Some protected areas in Indonesia are already open with an entrance fee, such as Sungai Wain Protection Forest. The example of the Raja Ampat marine park in West Papua could be more widely replicated: since 2015 international visitors must pay an entry fee of IDR 1 million (USD 67) and Indonesians half as much; the funds are used to cover operational costs of the five marine protected areas, and for conservation and development programmes (Stay Raja Ampat, 2018).

When user fees cannot be set high enough to limit visitors to sustainable limits, infrastructure and regulations could also limit the number of potential visitors and restrict movement within opened protected areas. For example, in the Galapagos Islands, the number of ships allowed to cruise the archipelago is limited. In addition, concession fees could complement revenues and provide services to attract more tourists but with sensible restrictions under appropriate contracts. For some areas like cultural heritage sites, the authorities could encourage private investment to transform them into tourism facilities by granting concession rights free of charge, as practiced in Italy since 2014 (OECD, 2018a).

Ecotourism – visiting relatively undisturbed natural areas with low impact and often at small scale – is a way to promote some less developed regions. Costa Rica has successfully built a strong ecotourism sector by creating a well-recognised green trademark, which has also raised rural incomes through the resulting new job opportunities (OECD, 2016c). In Indonesia, the example of Kalibiru (special province of Yogyakarta) is encouraging: forestland was granted to the community and deforestation was stopped in the context of a small-scale tourism project, with particular attention to sustainability (Vitasurya, 2016). The authorities should encourage the development of small-scale ecotourism projects and provide capacity building and supporting infrastructure (including digital) to promote potential clusters.

Tourism development can have some direct positive environmental impacts. First, the increase in tourism will generate more revenue for all levels of government in terms of taxes, fees and other levies. While earmarking is not usually desirable, these additional revenues can help governments to preserve the environment. Second, tourism also has the potential to increase public appreciation of the environment and to spread awareness of environmental issues, including through greater domestic tourism as occurred in Brazil (OECD, 2015). Finally, the economic interests of the private sector for developing tourism can directly trigger some positive outcomes for the environment. For example, some tour operators are donating to the Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Programme, and Indonesian hotels regularly clean beaches in their vicinity. Efforts of the private sector to contribute to public goods and to co-ordinate with the public sector should be encouraged.

Box 2.3. Tourism in protected areas

Depending on the purpose, protected areas are generally classified under six categories ranging from a site reserved for scientific research and wilderness protection to a natural ecosystem used in a sustainable way (Dudley, Stolton and Shadie, 2013). Many sites are capable of supporting visitors, albeit in different forms, which can generate funds for environmental protection and awareness raising. Finding the right balance between short- to medium-term economic returns and long-term asset preservation will depend on the optimal number of visitors (Daubanes, 2017). Demand for visits increases with environmental quality and uniqueness, but more visitors mean more infrastructure is required, and risks to the quality of the protected area are higher. Eventually overuse leads to degradation, which lowers demand. Different tools can help regulate the volume of tourists and exploit their potential without blighting the future of the protected area:

Visitor fees, such as for access and for additional activities (e.g. diving, trekking), can generate benefits that help cover the initial set-up costs (to organise facilities for tourists) and operating costs, and can fund environmental protection. The fees can be adapted to users’ characteristics; for instance, they can be lower for locals than for foreigners. The price can be adjusted to the season to regulate flows. However, user fees are generally not sufficient to preserve an area, as they do not restrain bad behaviour and may not prevent excessive flows.

Concession fees can complement revenues to protect the area. In some places private actors could run businesses related to food, lodging, transport, guiding, outdoor activities and retail services. Key challenges are to design adequate frameworks for contracts and then to monitor compliance.

Specific regulations can be used to limit visitors to carrying capacity such as a maximum number of visitors at any given moment.

A regulatory framework to control the use of the protected area can take different forms. First, rules are set to limit use and establish a minimum level of protection, but they need enforcement. Second, signs, pathways and similar measures can encourage visitors to follow the right principles. Third, information such as signs and flyers make visitors aware of the consequences of their actions but leaves them more freedom during their visit.

For successful management of protected areas, governments should establish national frameworks that take tourism into account as well as educate local populations and preserve the environment (Eagles, McCool and Haynes, 2002). Each protected area can then establish a management plan under the national policy. Local stakeholders’ involvement is important to ensure that they share in the economic benefits of opening up the protected area. Biosphere reserves (11 in Indonesia already) are part of the UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere Programme which aims to achieve the interconnected functions of conservation, development and logistic support, including through a multi-stakeholder approach, zoning schemes and education and training (UNESCO, 2017). Those reserves allow for the development of sustainable tourism and should be promoted.

Improving the planning process to better include local needs

There are three main development plans in Indonesia produced at the central level: long-term (20 years), medium-term (5 years) and short-term (1 year). The current long-term plan (Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Panjang Nasional, or RPJPN) covers 2005 to 2025 and is translated into the National Medium-Term Development Plan (Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Nasional, or RPJMN), currently in its third period (2015-19). Most of the SDG targets are aligned with national targets (under the President’s agenda, known as “Nawacita”, and the Medium-Term Development Plan), thereby securing resources for their achievement. Related tourism planning is also well established (see above). However, despite a highly decentralised system, the connection with sub-national governments is not working efficiently and local needs are then not sufficiently taken into account. The monitoring of sub-national government spending is weak and the inter-governmental fiscal transfer system lacks predictability (World Bank, 2018a). Co-ordination across multiple ministries and government units is also lacking (Ministry of Tourism and ILO, 2012).

Decentralisation can help align policies with local needs, but in practice its effectiveness is constrained by the limited capacity of officials at lower government levels and by insufficient co-ordination between actors (OECD, 2016a). For example, in 2014 the Ministry of Tourism, GIZ (the German Development Agency) and the province of West Nusa Tenggara established the first Tourism Masterplan for the island of Lombok. While a positive initiative, a lack of co-ordination with districts and villages prevented full implementation of the plan, justifying the need for a new masterplan that is being prepared in 2018 with the World Bank. For the development of Lake Toba, six district-level governments are involved in the development of the area's tourism, which again suggests the likelihood of co-ordination problems (Dong and Manning, 2017). That points to a role for provinces in improving co-ordination between lower-level governments in tourism matters. This could be through a provincial working group on tourism involving districts and villages, for example. Regional tourism satellite accounts would increase awareness of tourism at the sub-national level and also fully describe the local sectoral connections. Given the complexity of building such accounts, an initial step would be to enhance statistical collection at the provincial level.

The growth of tourism is expected to increase employment opportunities for the local population (see above). For this to happen, it is essential to have the acceptance and support of such development from the communities that will reap the benefits and costs associated with tourism development. As in many countries, destination management plans (DMP) can be used to support tourism development and take into account local needs and characteristics (OECD, 2018a). They can help to co-ordinate public and private actors. They can also help promote local ownership and encourage a more integrated and balanced approach to tourism development when undertaken in co-ordination with national strategic plans (see Box 2.4 for an example from Iceland). In France, “destination contracts” were signed in 2016 to develop specific local areas. The contracts were established gathering all tourism actors and aimed to attract more international visitors (French Ministry of Economic and Financial affairs, 2016). Masterplans, which are a form of DMP, will be delivered for the 10 priority tourist destinations in 2019 at the earliest, with the assistance of the World Bank and Switzerland. Strategic plans of this nature are necessary to put the appropriate framework in place to promote strategic and sustainable tourism growth and as such should involve key stakeholders from the outset. The authorities should therefore gradually produce masterplans for all strategic tourism areas, notably to incorporate needed infrastructure at the local level.

Box 2.4. Tourism management in Iceland: adapting to rapid growth