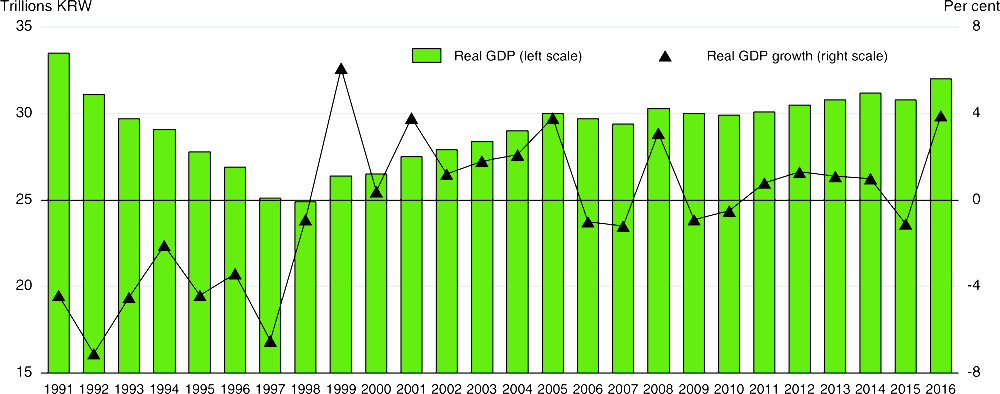

After contracting in 2015, the North Korean economy grew 3.9% in 2016, the fastest rate since 1999, despite a further contraction in its foreign trade (Figure A1.1). Manufacturing and mining (58% of GDP) were supported by the “speed battle” campaign of mass mobilisation to speed up production. The campaign included output quotas at state-owned enterprises, which required the accelerated use of resources. Agriculture also recovered following the 2015 drought. Continued marketisation through the dollarisation of the North Korean economy has supported economic activity and helped stabilise the unofficial exchange rate and the rice price (Lee, 2017a). Faster growth in 2016 boosted real GDP to its highest level since 1991. Nevertheless, per capita gross national income in the South is 21.9 times higher than in the North (Table A1.1), raising concern about the potential cost of economic rapprochement. Production and investment growth appears to have declined on a year-on-year basis in the first half of 2017, reflecting renewed droughts, the payback from the “speed battle” campaign and the tightening of sanctions (Lee, 2017b).

OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2018

Annex A1. Economic co-operation with North Korea

Figure A1.1. The North Korean economy grew rapidly in 2016, despite international sanctions

Table A1.1. Comparison of North and South Korea in 2016

|

(A) North Korea |

(B) South Korea |

Ratio (B/A) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Population (millions) |

24.9 |

51.2 |

2.1 |

|

GNI (trillion KRW) |

36.4 |

1 639.1 |

45.1 |

|

GNI per capita (million KRW) |

1.5 |

32.0 |

21.9 |

|

Total trade (billion USD) |

6.5 |

901.6 |

138.1 |

|

Exports |

2.8 |

495.4 |

175.7 |

|

Imports |

3.7 |

406.2 |

109.5 |

|

Of which: inter-Korean exports1 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

|

Industrial statistics (2014) |

|||

|

Power generation (billion kWh) |

23.9 |

540.4 |

22.6 |

|

Steel production (million tonnes) |

1.2 |

68.6 |

56.3 |

|

Cement production (million tonnes) |

7.1 |

56.7 |

8.0 |

|

Agricultural production (2014) |

|||

|

Rice (million tonnes) |

2.2 |

4.2 |

1.9 |

|

Fertiliser (million tonnes) |

0.6 |

2.1 |

3.4 |

1. North Korean exports to the South in column Panel A, and South Korean exports to the North in column B.

Source: Statistics Korea (Daejeon); Bank of Korea (Seoul).

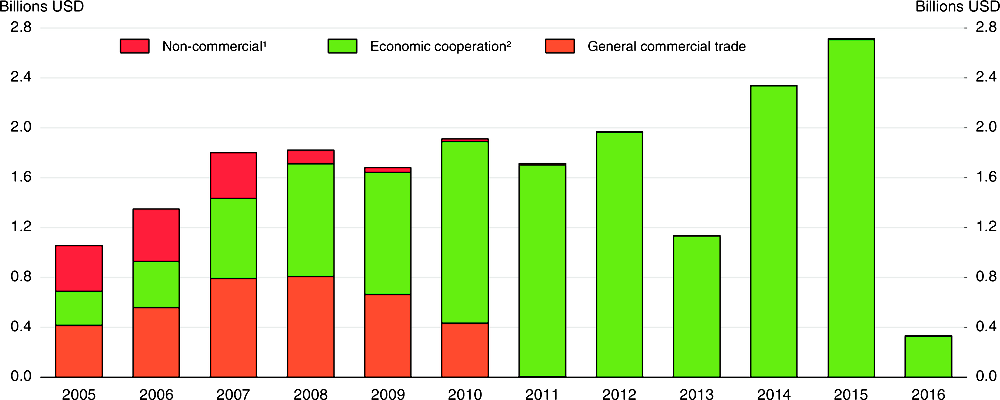

Inter-Korean trade in 2016 was only one-tenth of that in 2015 as production at the Gaesung Industrial Complex was suspended in February 2016 (Figure A1.2). The Complex, which was created in 2002, was home to 125 South Korean SMEs employing 54 000 North Korean workers. It was the last remaining symbol of inter-Korean reconciliation and the focus of inter-Korean trade. Its closure was in response to another nuclear test by the North and its launching of a long-range missile.

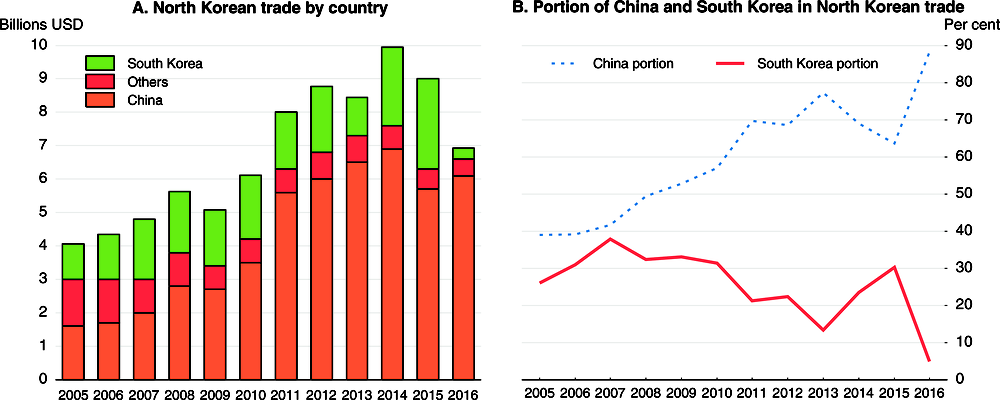

While North Korea’s trade with the South plunged, its commerce with China edged up in 2016, despite international sanctions (Figure A1.3). China’s recorded share of North Korean trade jumped from 64% in 2015 to 88% in 2016, while South Korea’s share fell to less than 5%. Coal and iron ore accounted for half of North Korean exports to China, boosted by a rise in their prices. However, the November 2016 UN sanctions prohibiting imports from North Korea for private use negatively affected the North’s trade with China in 2017. For example, Chinese refined oil exports to North Korea were down 54% (year-on-year) in September 2017, (Kim, 2017).

Figure A1.2. Inter-Korean trade fell sharply following the closure of the Gaesung Industrial Complex

1. Primarily humanitarian aid.

2. Includes special projects, notably the Gaesung Industrial Complex and the Mount Geumgang resort. However, the resort was closed in 2008 and the industrial complex was suspended in February 2016.

Source: Statistics Korea (Daejeon).

Figure A1.3. Trends in North Korean trade

In July 2017, South Korea launched the Berlin Initiative, which aims at peaceful coexistence and common prosperity through “dialogue and co-operation”, as well as “sanctions and pressure”. It is based on three objectives: i) the establishment of permanent peace through the denuclearisation of North Korea; ii) the development of sustainable inter-Korean relations; and iii) the creation of a Korean Peninsula New Economy Community that includes an East Coast Belt, West Coast Belt and DMZ Belt. The government’s goal is to “build a single market on the Korean Peninsula to create new growth engines and create an inter-Korean economic community of co-existence and co-prosperity” (Ministry of Unification, 2017). Nevertheless, inter-Korean economic co-operation did not resume as North Korea continued to develop its nuclear and missile programme, including the launch of an ICBM missile in July 2017. However, in early January 2018, the two sides held talks, their first in two years, to arrange North Korea’s participation in the PyeongChang Winter Olympics. This was followed by a summit between the leaders of South and North Korea in April 2018 at which they agreed to the “Panmunjeom Declaration for Peace, Prosperity and Unification of the Korean Peninsula”. The Declaration called for the “complete” denuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula, a peace treaty to replace the armistice in place since the end of the Korean War, steps to ease military tensions, expanded economic co‐operation between South and North Korea and increased humanitarian exchanges.

Sanctions imposed by the international community reduced North Korea’s trade by a third over 2014-16. In addition, North Korea is facing difficulties in earning foreign currency, as the dispatch of workers overseas and investment in the North’s Economic Development Zones, such as Najin and Sonbong, are blocked by international sanctions. The effect of sanctions has become increasingly apparent since early 2017, squeezing the North’s foreign currency earnings and making it difficult to import food and basic necessities (Lim and Choi, 2017). The sharp drop in oil imports has led to severe electricity shortages. North Korea is trying to mitigate the impact of sanctions by allowing greater marketisation of its economy (Lee, 2016). Rather than suppressing the role of markets, North Korea is focusing on stabilising prices and exchange rates by institutionalising markets. Already by October 2016, local authorities had established 436 “comprehensive markets”. Moreover, these markets are moving from the outskirts of urban areas to the centre and their size is increasing (Lim, 2017).