Making SMEs and start-ups a driver of growth and job creation requires a number of policies to improve the performance of SMEs, whose labour productivity in the manufacturing sector has fallen to less than a third of that in large companies. The large-scale support for SMEs should shift from supporting the survival of firms to raising productivity. Measures to accelerate SMEs’ take-up of new technology and increase their participation in international trade would boost productivity and inclusive growth. Given the chronic labour shortages facing SMEs, reforming the education system to reduce labour market mismatch is a priority. Relaxing the regulatory burden and government control would allow innovative SMEs to create new products and services. Entrepreneurship is lagging, reflecting a higher fear of failure and a lack of skills. Upgrading entrepreneurship education and lowering the personal costs faced by entrepreneurs who fail would be beneficial. A greater role for venture capital, in part by activating the M&A market to allow investors to recuperate their funds, would encourage firm creation.

OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2018

Chapter 2. Enhancing dynamism in SMEs and entrepreneurship

Abstract

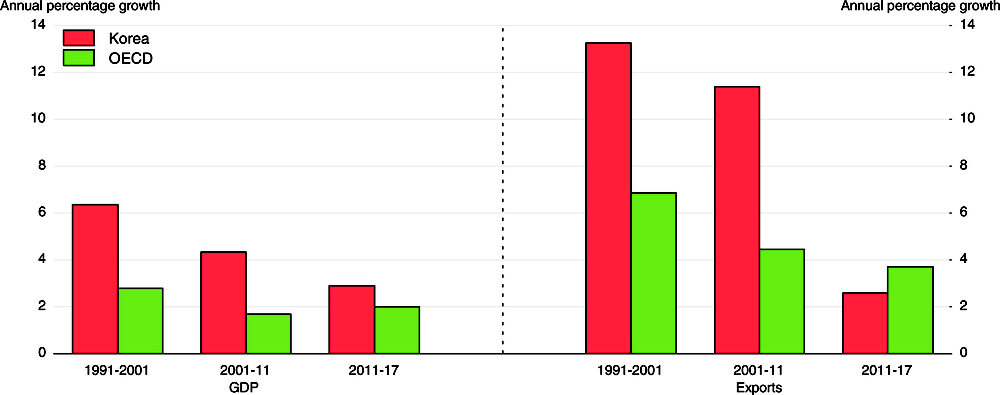

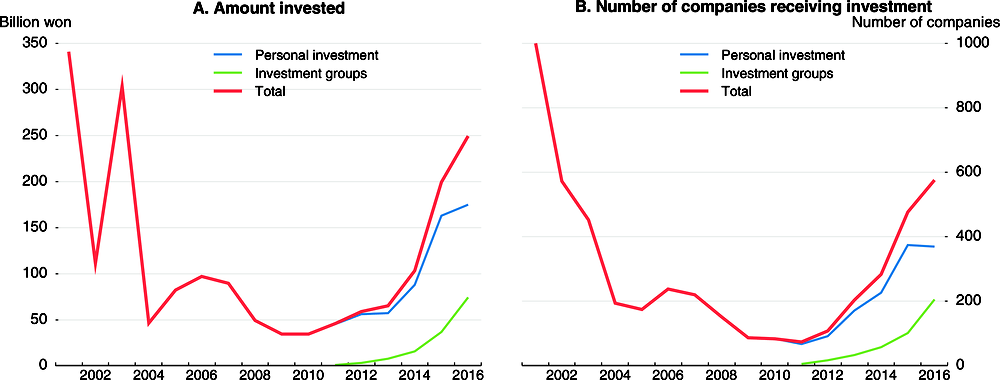

In the new paradigm envisaged by the government, SMEs and start-ups will replace large firms as drivers of innovation. One reason for a new strategy is that the traditional model of growth led by exports of manufactures by large business groups, known as chaebols, which fuelled Korea’s exceptionally rapid economic development (Chapter 1), appears to be faltering. Although economic growth typically slows as countries approach the high-income economies, the sharp deceleration from an annual rate of 6.4% over 1991-2001 to 2.9% since 2011 (Figure 2.1), raises concerns. Moreover, export volume growth slowed from a double-digit annual pace over 1991-2011 to 2.6% since 2011, lagging behind global trade.

Figure 2.1. Korea’s output and export growth have slowed sharply

The export deceleration has limited the growth of employment and household income. In addition, the “trickle-down effect” – the expansion in domestic demand and employment for a given increase in exports – appears to be weakening. The additional value added and employment induced by production in the semiconductor, car, and ship industries has already started to decrease (Hong and Hong, 2017). In the face of intensified competition from emerging countries, particularly China, firms have limited wage increases and shifted production overseas. The share of overseas production by large firms rose from 16.8% in 2009 to 22.1% in 2014, with a negative effect on subcontracting companies. Large firms have also responded to intensified competition by increasing labour-saving investment and by shifting their product mix to more capital and technology-intensive products. However, the experience of the past few years suggests that exports by large companies are not sufficient to sustain Korea’s growth.

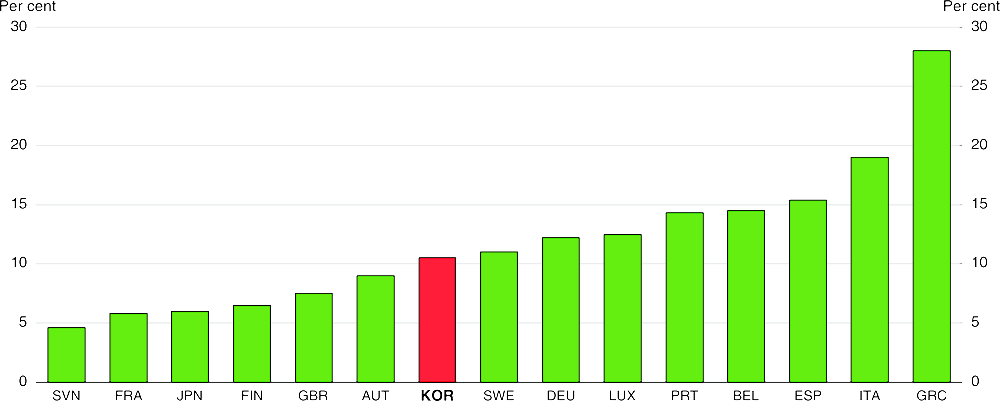

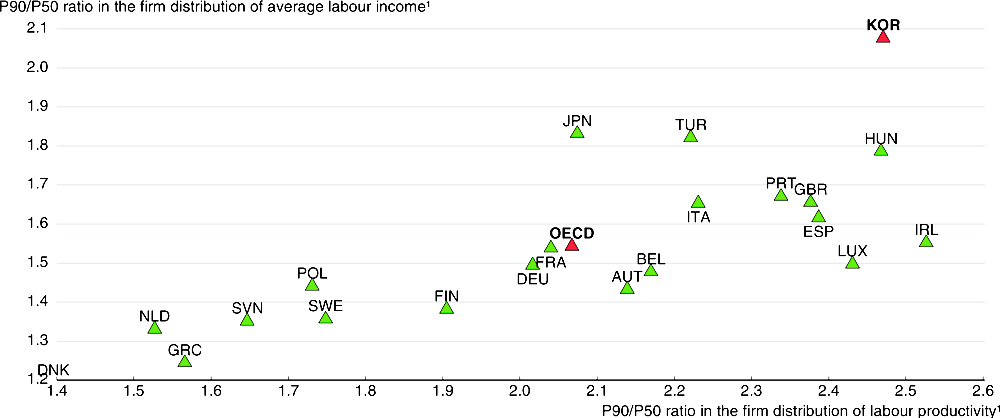

In addition, Korea’s traditional growth model has led to economic polarisation and inequality. The economic dominance of large business groups, which received generous government support during the high-growth era (Chapter 1), has stifled opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). While the government has provided extensive support to SMEs, large productivity gaps between large firms and SMEs and between the manufacturing and service sectors have contributed to greater income inequality. Indeed, the dispersion between productivity in firms at the 90th and 50th percentiles in the OECD area is positively correlated with the dispersion in average wage income (Figure 2.2). For example, productivity and labour income gaps are relatively small in some northern European countries in contrast to some central European countries. The dispersion of productivity in Korea is the second highest in the OECD and the dispersion of wage income is the highest, boosted as well by labour market dualism.

Figure 2.2. Labour income inequality is positively correlated with productivity disparities between firms

1. This figure compares the labour productivity and labour income of a firm at the 90th percentile to one at the 50th percentile.

Source: OECD (2016c).

The lack of SME dynamism in an economy dominated by large manufacturing exporters is thus a source of inequality in addition to being a serious drag on output growth in Korea. Policies that improve the performance of SMEs will promote inclusive growth by creating job opportunities and boosting the quality of SME jobs by raising productivity and wages. Indeed, small enterprises are the main source of net job creation in the OECD (OECD, 2016b). In addition, development of SMEs tends to promote broad-based income gains across regions and industries, thereby reducing income inequality and poverty (OECD, 2009 and 2017c). Moreover, promoting innovative entrepreneurship is an important channel for enhancing social participation and mobility, particularly for women and youth.

Achieving inclusive growth thus requires policies that improve the performance of SMEs, particularly in the service sector. The longstanding government objective of promoting growth through innovation requires a greater contribution from SMEs. To accomplish this, the government aims to build an innovative ecosystem to foster SMEs, helping them to lead the fourth industrial revolution, and increase their participation in world trade. This emphasis is reflected in the creation of the Ministry of SMEs and Start-ups (MSS) in 2017. In addition, a range of new programmes is envisaged (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Initiatives launched by the new government to promote SMEs and start-ups

Measures to boost financing

The government is launching a KRW 10 trillion (USD 9.3 billion) venture capital investment fund.

Increased financial support for SMEs is being provided through state-owned banks.

The Ministry of SMEs and Start-ups (MSS) is boosting support for start-ups that contribute to job creation.

The Financial Services Commission is working to attract more funds to SMEs and venture start-ups.

The government is developing the KOSDAQ (Korean Securities Dealers Automated Quotations) market (a second-tier market for smaller firms) to support innovative SMEs.

The central bank is increasing its lending support through financial intermediaries.

The government is expanding assistance to SME exporters.

Addressing labour shortages

The government is providing SMEs with annual support of KRW 20 million (USD 18 524) per newly hired young adult employee for three years.

The government is encouraging young employees at SMEs to remain in their jobs by increasing the matching funds that it provides to their individual savings accounts.

Other policies

To promote the fourth industrial revolution, MSS is introducing programmes, such as cross-generation start-up teams, to promote the creation of new industries.

MSS is implementing all of its start-up programmes as “Tech Incubator Programmes for Start-ups", which provide mentoring and technology development.

The government is protecting small merchants and SMEs by reducing costs, including labour, social insurance premiums, credit card fees, taxes, financial debts and rent.

Penalties on unfair subcontracting practices are being increased and policies to eliminate such practices are to be introduced.

Building on the 2014 and 2016 OECD Economic Surveys of Korea, this chapter analyses the current status of SMEs to develop policy directions that promote higher productivity and inclusive growth. After a brief overview of the SME sector, the second section discusses the need for innovation to increase productivity. The third section addresses an urgent need – overcoming the chronic labour shortages faced by SMEs. The benefits of increasing SMEs’ role in international trade is analysed in the fourth section, followed by a discussion of various measures to improve the SME ecosystem. Policies to promote entrepreneurship are considered in the sixth section, followed by a discussion of SME financing issues. Policy recommendations are presented at the end of the chapter.

Overview of SMEs in Korea

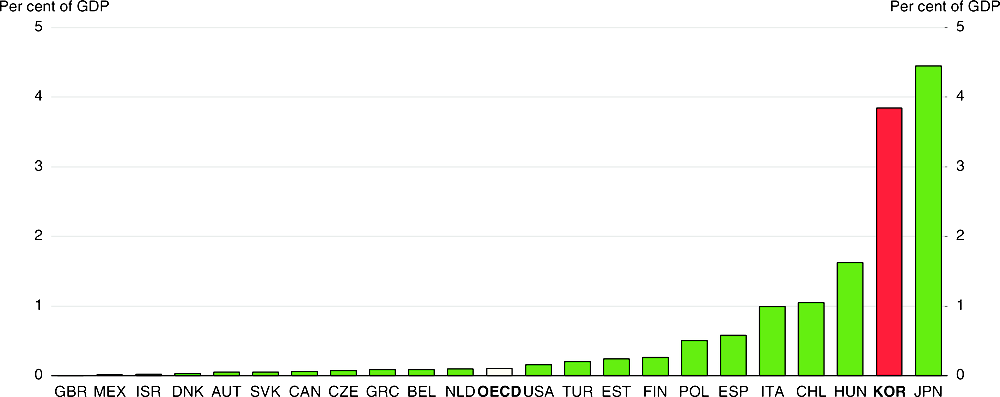

SMEs play a prominent role in Korea (Box 2.2). The early departure of employees from firms – before age 50 on average – prompts a large number to create small firms using their retirement allowance. SMEs are thus a key element of the social safety net. Korea’s 1987 Constitution declares that the “State shall protect and foster SMEs”. In 2017, there were 288 central government programmes to support SMEs, in addition to 1 059 programmes at the local government level. Central government spending on such programmes amounted to 3.0% of its total spending in 2017. The government also provides large-scale support to SMEs through public funds and credit guarantees, which were the second largest in the OECD at 3.8% of GDP in 2016 (Figure 2.4).

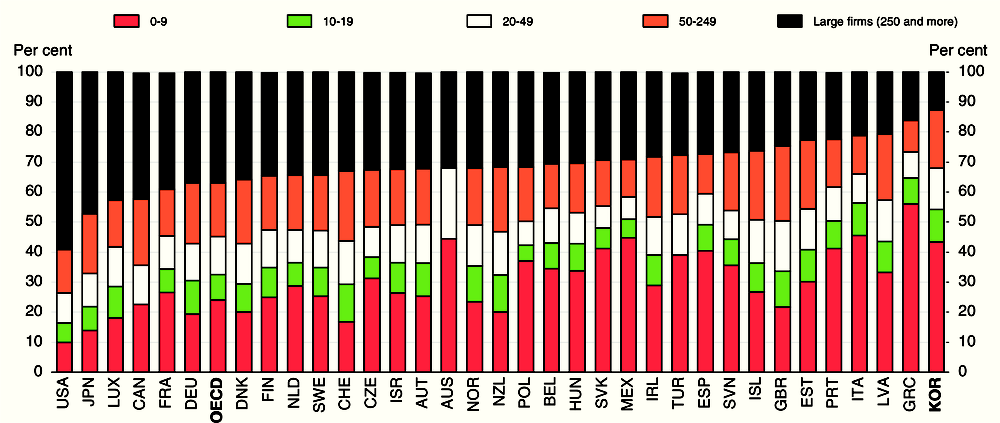

Box 2.2. A statistical overview of large firms, mid-sized firms and SMEs in Korea

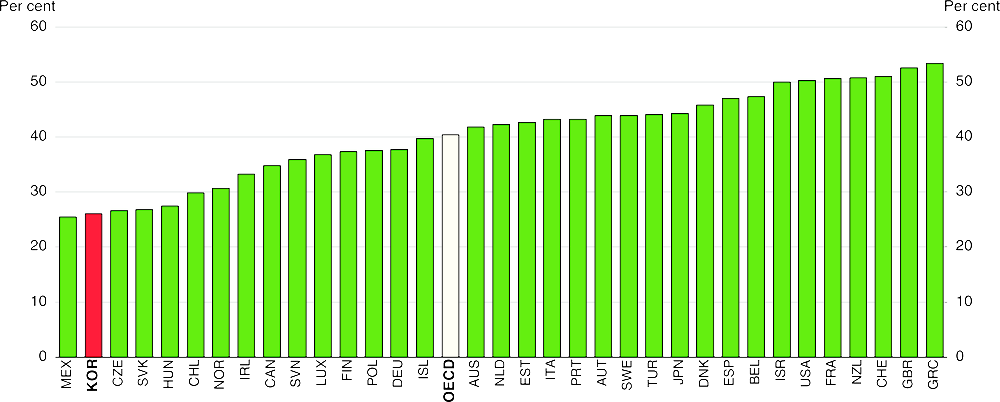

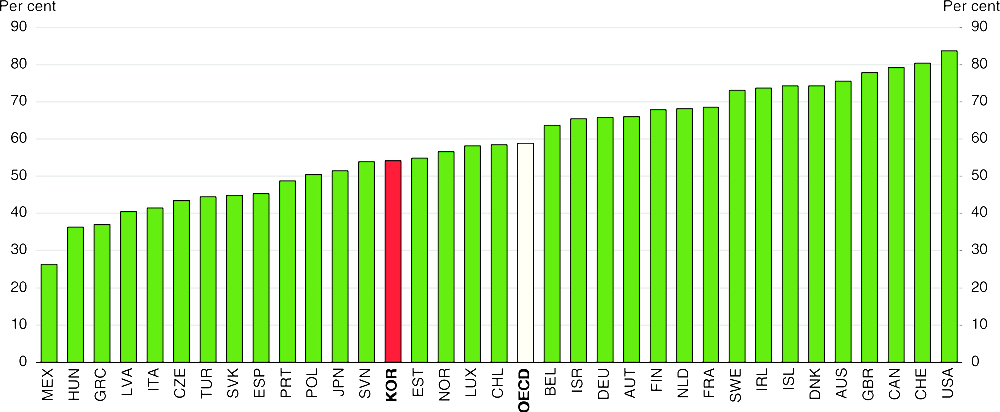

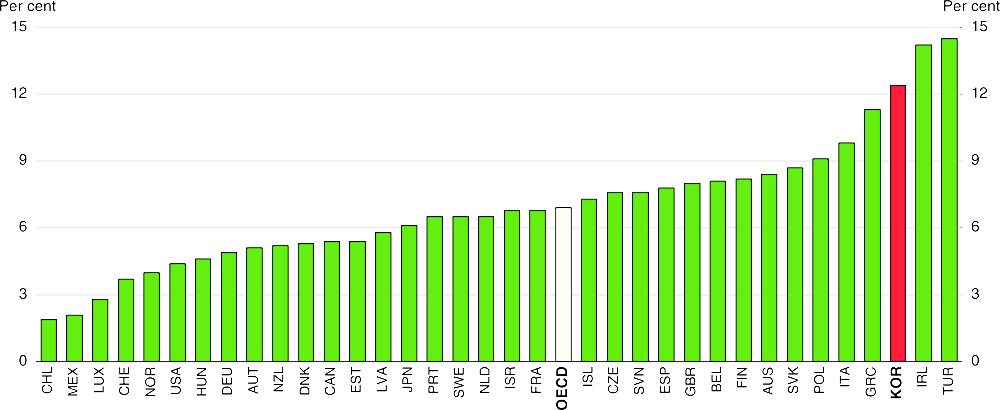

There is no standard international definition of SMEs. For statistical purposes, the OECD defines SMEs as firms with up to 249 employees, divided into: micro-enterprises (1 to 9); small firms (10 to 49); and medium enterprises (50 to 249). By this definition, the share of workers employed at SMEs in Korea was the highest in the OECD at 88% in 2015 (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.3. The share of employment in SMEs in Korea is the highest in the OECD

Percentage of all persons, total business economy, 2015 or latest available year

1. For Canada, Switzerland, Israel, Japan, Korea and the United States, data do not include non-employer enterprises, which are primarily self-employed persons. Data for Korea and Mexico are based on establishments. Data for the United Kingdom exclude an estimated 2.6 million small unregistered businesses. For Australia, Canada and Turkey the size class 1~9 refers to 1~19.

Source: OECD Structural and Demographic Business Statistics (ISIC Rev. 4) (database).

Until 2014, the definition of SMEs in Korea was based on the number of regular workers, sales, capital and total assets, with the thresholds varying by industry. However, this had a statistically significant negative impact on the growth of small firms: SMEs artificially stayed below the thresholds in order to continue receiving the favourable treatment offered to SMEs (Kim, 2017). To reduce this distortion, the definition was changed in 2015 to total assets (up to KRW 500 billion – USD 463 million) and sales. To be classified as a SME, a firm’s average sales during the past three years must not surpass a certain threshold of the industry in which they operate. The ceiling on sales ranges from KRW 40 billion (USD 37 million) to KRW 150 billion (USD 139 million) in the industries specified in the law on SMEs. However, the incentives for SMEs to remain below the threshold are still present under this revised definition.

Almost two-thirds of SME employment is in the service sector, with manufacturing accounting for another 27% and construction 8%. SMEs accounted for 90% of employees in the service sector, 85% in construction and 81% in manufacturing in 2014 (OECD, 2017c).

In 2014, the government established an intermediate classification of mid-sized enterprises that includes firms that are too large to qualify as SMEs and are not affiliated with the large business groups that are subject to rules on cross-shareholding. Total assets of firms in this category must be between KRW 500 billion and KRW 10 trillion (USD 9.3 billion), which, as in the case of SMEs, creates disincentives to growth. This category excludes firms that are more than 30% owned by financial, public and non-profit institutions or whose largest shareholder is a foreign company. Although economic power is concentrated in the large enterprises (see Chapter 1), the mid-size firms, which are often referred to as “high potential enterprises”, play an important and expanding role. Indeed, their growth in sales and assets in 2013 exceeded that of SMEs and large firms (Table 2.1).

SMEs accounted for 99.8% of firms and 76.8% of employment in 2014 (Table 2.1). In addition, SMEs had the largest proportion of sales, although large enterprises accounted for two-thirds of exports. However, SMEs had the lowest operating profit margin and the highest debt-to-equity ratio (Panel C), although this partly reflects the fact that they tend to be younger than larger firms.

Table 2.1. A comparison of large firms, mid-sized firms and SMEs

|

A. Percentage of total in 2014 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Large enterprises |

Mid-size firms1 |

SMEs |

|

|

Enterprises |

0.05 |

0.12 |

99.8 |

|

Employees |

13.5 |

9.7 |

76.8 |

|

Sales |

40.2 |

14.8 |

45.0 |

|

Exports |

67.0 |

15.7 |

17.1 |

|

B. Percentage growth in 2013 |

|||

|

Sales |

0.3 |

5.8 |

5.6 |

|

Assets |

7.9 |

8.3 |

3.6 |

|

C. Ratios in 2013 |

|||

|

Operating profits margins2 |

4.7 |

4.1 |

3.2 |

|

Debt-equity ratio |

133.5 |

120.2 |

168.3 |

|

Labour productivity3 |

100.0 |

56.2 |

28.8 |

1. Often referred to as high potential enterprises.

2. As a percentage of sales.

3. Labour productivity as per cent of that in large companies.

Source: Statistics Korea.

Korea faces large and widening gaps in labour productivity between the different firm sizes. Indeed, the labour productivity of SMEs is only about half of mid-sized firms, which in turn is a bit more than half of the large firms. As noted above, large productivity gaps exacerbate income inequality and are an obstacle to inclusive growth. In addition, the low productivity in SMEs and mid-sized firms handicaps large firms, whose international competitiveness depends in part on the efficiency of its suppliers. Low productivity in smaller firms thus tends to accelerate off-shoring.

In addition, SMEs are assisted through: i) preferential treatment in public procurement; ii) lower tax rates at both the central and local government levels and preferential treatment that lower taxable income; iii) exemptions for associations of SMEs from the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act; iv) the right to hire foreign workers; and v) discounted prices for water and electricity. The decline in labour productivity in SMEs in manufacturing from more than half of large companies to less than a third (see below) calls into question the effectiveness of such support and the importance of new approaches.

Figure 2.4. Government credit guarantees for SMEs in Korea are exceptionally high

Stock of guarantees in 2016 or latest year available

SMEs’ share of value added in manufacturing edged up from 47.4% in 2004 to 49.1% in 2014 (Table 2.2). While their share in heavy industry also increased slightly, it remains much less than the SMEs’ 84.6% share of value added in light industry. The concentration of SMEs in labour-intensive sectors is a key reason for their lower wages and productivity. It also makes SMEs the main source of job creation. Firms with less than 300 employees accounted for 91.9% of the employment gains in 2015 (Table 2.3). Micro-firms (those with less than ten employees) alone accounted for three-quarters.

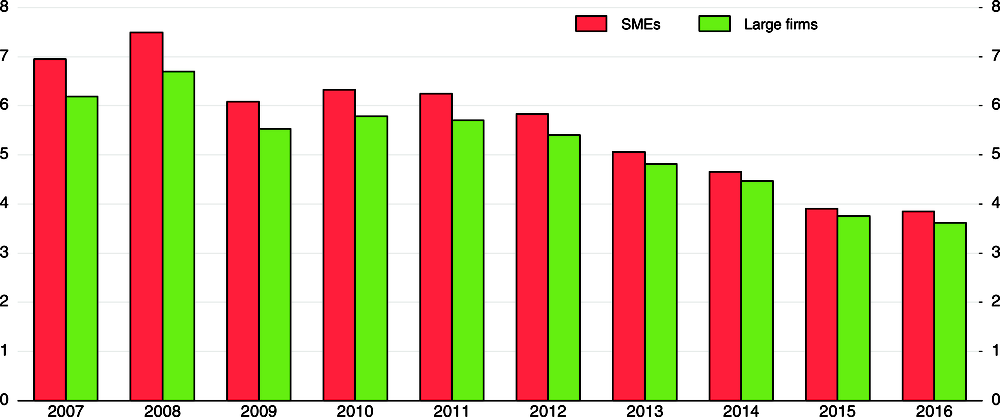

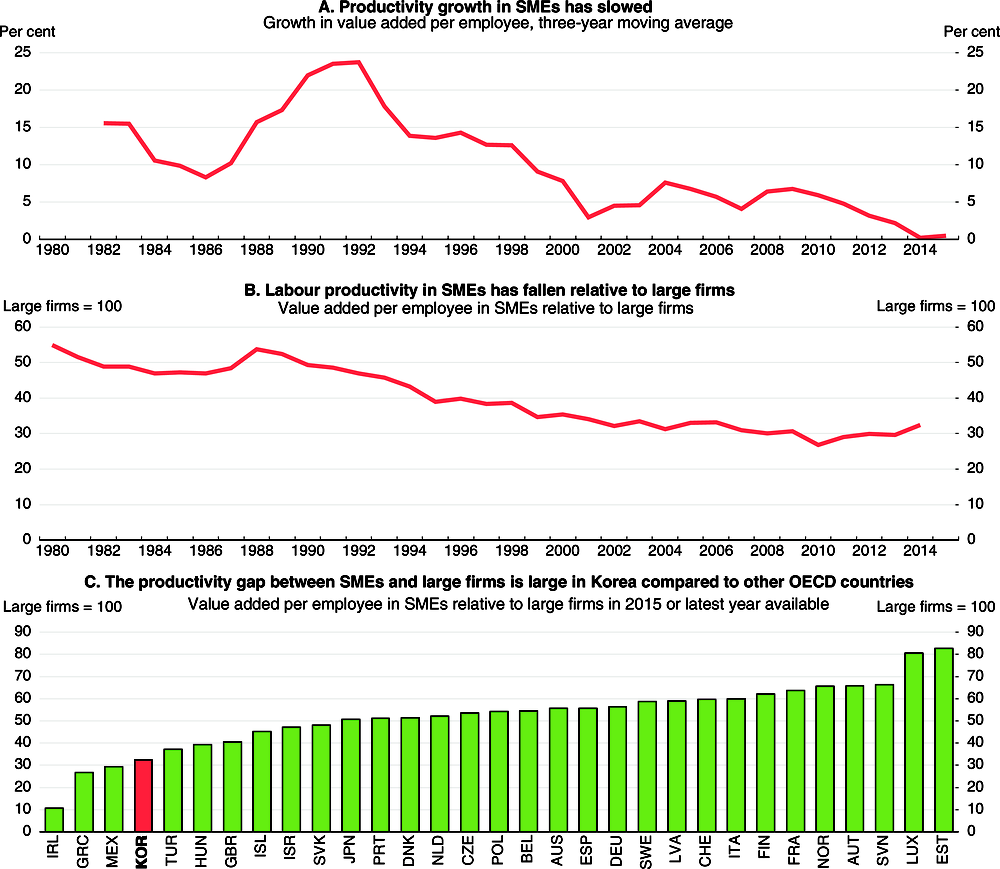

Despite increasing government support, the growth of value added per worker in SMEs has been on a downward trend (Figure 2.5). Labour productivity in SMEs in manufacturing fell from 53.8% of that in large firms in 1988 to 32.5% in 2014 (Panel B). The productivity gap between large firms and SMEs is one of the biggest in the OECD (Panel C). While data are not available for the entire service sector, labour productivity of small firms (one to nine employees) in the retail and wholesale sector was only 24% of that in large firms in 2012, the largest gap among the 25 countries for which data are available (OECD, 2015b). Low productivity in SMEs may be related in part to weak investment, which has limited their role in the transition to technology and knowledge-intensive activities. On the positive side, their financial structure has been strengthened: the debt-to-equity ratio of SMEs, which soared to 305.5% during the financial crisis in 1997, fell to 168% in 2013.

Table 2.2. SMEs’ share of manufacturing value added is edging up

Percentage of value added

1. Light industry includes food and beverages, tobacco, textiles, clothing, leather products, wood and wood products, paper and paper products, printed and recorded products, rubber and plastic products, furniture and other products.

2. Heavy industry includes refined petroleum products; chemicals and chemical products; medical materials and medicines; non-metal mineral products; primary metals; metal processing products; electronic components; communication, computer, video and audio equipment; medical, precision and optical machinery; watches; electrical equipment; other machinery; cars; and other transport equipment.

Source: Statistics Korea, Survey of Mining and Manufacturing.

Table 2.3. SMEs, especially micro-firms, account for most of employment gains

Thousand workers in 2015

|

Firms by number of employees |

Gain in employment due to: |

Net gain in employment A + B |

Share of employment gains (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Establishment and closure of firms (A) |

Growth and decline of firms (B) |

|||

|

0-4 |

125 |

129 |

254 |

64.1 |

|

5-9 |

47 |

1 |

48 |

12.1 |

|

10-29 |

42 |

-6 |

36 |

9.1 |

|

30-99 |

27 |

-11 |

16 |

4.0 |

|

100-299 |

15 |

-5 |

10 |

2.5 |

|

Under 300 |

256 |

108 |

364 |

91.9 |

|

300+ |

9 |

23 |

32 |

8.1 |

|

Total |

265 |

131 |

396 |

100.0 |

Source: Noh (2017).

Figure 2.5. Labour productivity in SMEs in manufacturing is low

Source: Statistics Korea, KOSIS database; OECD Structural and Demographic Business Statistics (ISIC Rev. 4) (database).

Enhancing productivity of SMEs through innovation

In the new paradigm envisaged by the government, Korea will shift from a fast follower adopting technology developed elsewhere to a first mover, led by SMEs and start-ups. SMEs and start-ups play a central role in innovation in many countries. As they tend to operate outside the dominant paradigm, they can more freely explore technology and commercial opportunities that tend to be overlooked by existing firms (Baumol, 2002; OECD, 2010). The advent of digitalisation is changing the business environment by levelling the playing field between SMEs and larger firms. A small firm today has access to communications and information systems that were available only to large multinationals a few decades ago. The active use of digital platforms can improve the productivity and price competitiveness of SMEs compared to large enterprises. It can also enhance access to alternative financial instruments and promote the emergence of innovative start-ups by using the Internet to lower fixed costs and outsource important functions (OECD, 2017b). Even micro businesses can engage in exports as a major activity, capitalising on digital tools. Two-thirds of SMEs that export report that more than half of their international sales depend on online tools (OECD, 2017c).

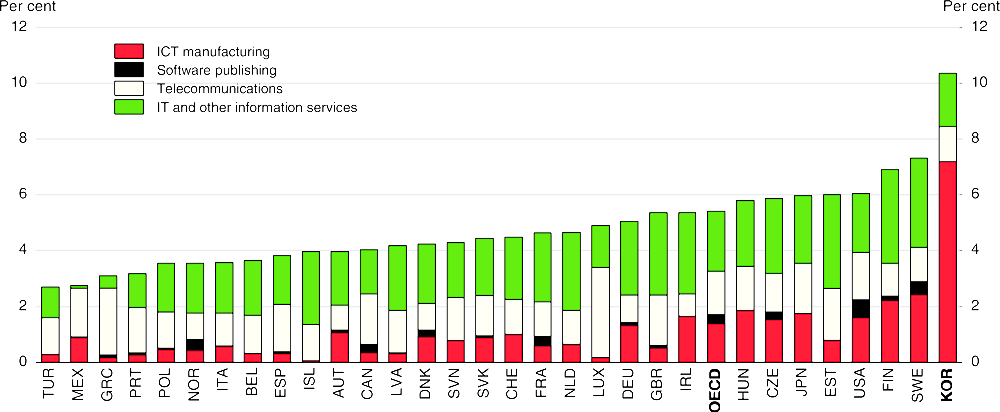

Building on its position as a world-leader in the provision of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) goods and benefiting from extensive broadband deployment, Korea has great scope to harness the potential of the digital economy to drive productivity. Korea’s large and growing ICT sector accounted for over 10% of value added in 2015, double the OECD average (Figure 2.6). However, this reflects the large share of ICT manufacturing (7% of value added). In contrast, telecommunications, IT and other information services were below the OECD average as a share of GDP.

Figure 2.6. The ICT sector is large in Korea, and concentrated in manufacturing

In 2015

Weaknesses in digitalisation and automation slows innovation by SMEs

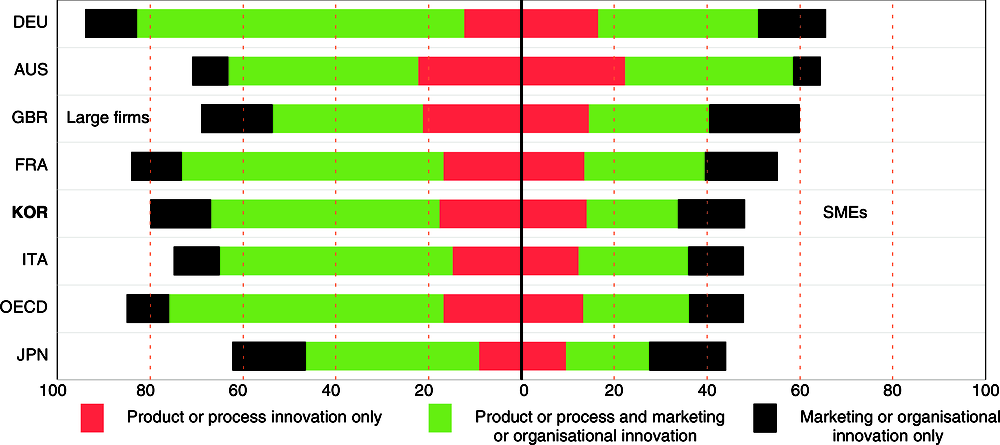

The proportion of innovative firms among SMEs is around the OECD average, but there is considerable scope for improvement to match the best performers (Figure 2.7). To generate innovation and new markets, it is essential to develop “convergence technology” – notably sensors, robots, and 3D printing – which integrates the possibilities generated by ICT. However, only 2.5% of Korean SMEs have acquired these technologies.

Figure 2.7. The proportion of innovative firms among SMEs in Korea matches the OECD average

Innovative firms, in percent of all firms in the given size category over 2012-141

1. For Korea, 2013-15.

Source: OECD (2017f), OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2017.

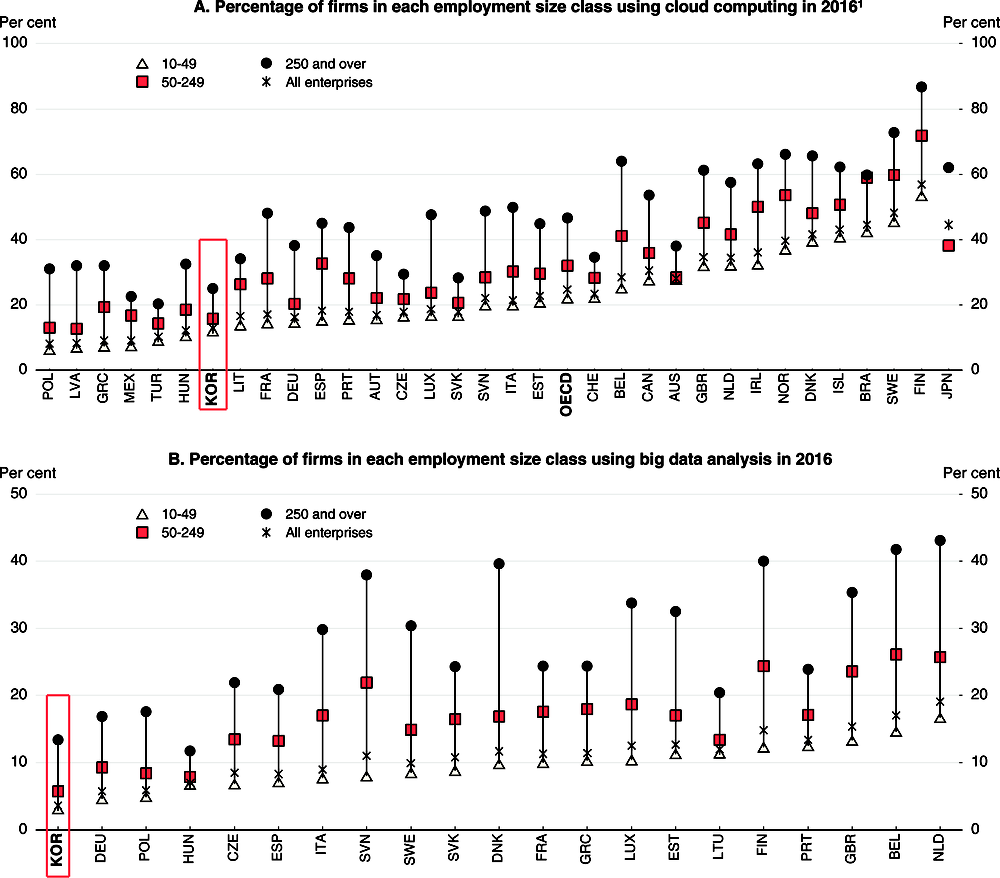

In particular, Korean firms lag far behind in their use of cloud computing technology, a key ICT convergence technology (Figure 2.8). The share of firms in Korea with between 50 and 249 employees that used cloud computing in 2016 was 10%, one-third of the OECD average. Cloud computing allows SMEs to overcome the barrier of high fixed costs associated with the use of “big data”, which is generated from activities that are carried out electronically and from machine-to-machine communications. Big data is a useful tool given its vast volume, variety and the velocity at which data are generated. For example, it allows SMEs to improve their production processes, satisfy the needs of customers, and gain a better understanding of the business environment. The share of Korean SMEs using big data was only 4% in 2016, well below the 11% OECD average (Panel B), reflecting their limited use of cloud computing.

Figure 2.8. Korean firms lag significantly in their use of key digital technologies

1. Cloud computing refers to ICT services used over the Internet as a set of computing resources to access software, computing power, storage capacity and so on. Data refer to manufacturing and non-financial market services enterprises with ten or more persons employed, unless otherwise stated. Size classes are defined as: small (10~49 persons employed), medium (50~249) and large (250 and more). The OECD average in Panel A is a simple average of the available countries.

Source: OECD (2017e), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017.

In addition, 62.5% of SME exporters have not automated their manufacturing processes (Chang and Lee, 2017). Moreover, the level of automation that has been introduced is relatively basic, consisting of barcodes (17%) or radio-frequency identification (14%). The reason that SMEs do not automate their manufacturing processes is that more than half of them do not feel the necessity of automation. This suggests a lack of competition that would oblige firms to introduce automation to ensure their survival.

The creation of smart factories, based mainly on ICT, occurs primarily among large firms, while the share of SME workplaces converted to smart factories is low at 7.4%. To assist SMEs, the government announced that it would help 20 000 SMEs establish smart factories, which integrate software and the Internet of Things (IOT), by 2022. Half of the KRW 2 trillion (USD 1.85 billion) in funding is from the government with the other provided by the firms. In addition, the Korea Smart Factory Foundation supports SMEs that have limited technological capability. In order to accelerate the spread of smart factories, it is necessary to address the problems of redundant investment due to delayed standardisation, the leakage of internal technology to large firms and rising fixed costs. In addition, the diffusion of smart factories is limited by reliance on expensive foreign solutions (K. Chang, 2017). A lack of human resources in digitalisation also slows the introduction of technology in SMEs, which do not have the financial strength to match salaries offered by large firms (see below).

Policies to promote digitalisation and the take-up of new technology

The gap between firms at the technological frontier and lagging firms in the global economy has widened in recent years. This reflects, in part, the increasing cost and technical sophistication of new investments necessary to introduce cutting-edge technology. In addition, “it has become relatively easier for weak firms that do not adopt the latest technology to remain in the market” (Andrews et al., 2016). The survival of non-viable firms traps workers and capital in unproductive activities. In Korea, more than 10% of the capital stock in 2013 was sunk in non-viable (“zombie”) firms, defined as more than ten years old with an interest coverage ratio of less than one for more than three consecutive years (Figure 2.9).

Figure 2.9. The share of capital sunk in non-viable firms

Firms at least ten years old that had an interest coverage ratio under one for more than three consecutive years

Policies to spur competition are needed to encourage reallocation and increase firms’ incentives to increase digitalisation and other key technology. The most effective policies in this regard include (Andrews et al., 2018):

Reduce barriers to international trade and inward foreign direct investment.

Employment flexibility, which facilitates the expansion of innovative firms and the downsizing of lagging firms. However, Korea was ranked 106th in the world in labour market flexibility and 112th in the cost of redundancy by the Global Competitive Index (World Economic Forum, 2017).

Insolvency regimes that promote productivity by strengthening market selection and the reallocation of resources to more productive uses (see below).

Venture capital investment, which promotes the creation of innovative firms. Korea ranks fourth highest in the OECD with respect to venture capital investment as a share of GDP (see below).

Avoiding high corporate income tax rates promotes firm creation. Korea’s corporate tax rate was 22% in 2016, slightly below the 24.6% OECD average, but was raised to 25% for 77 large firms in 2017.

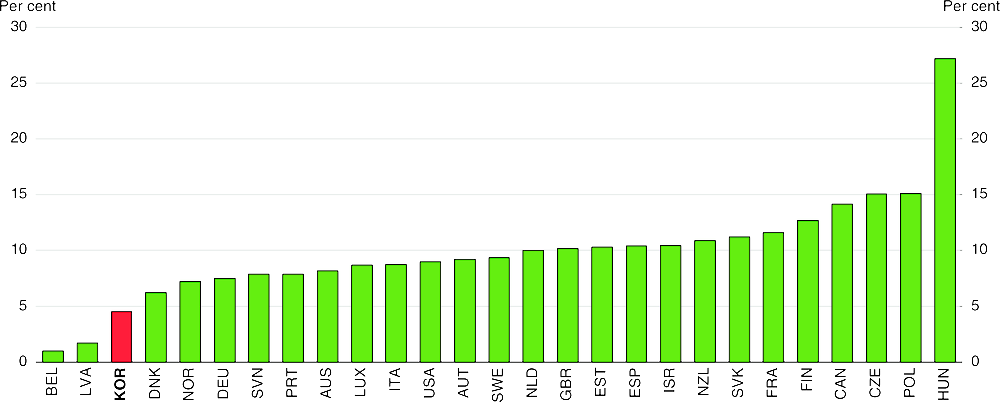

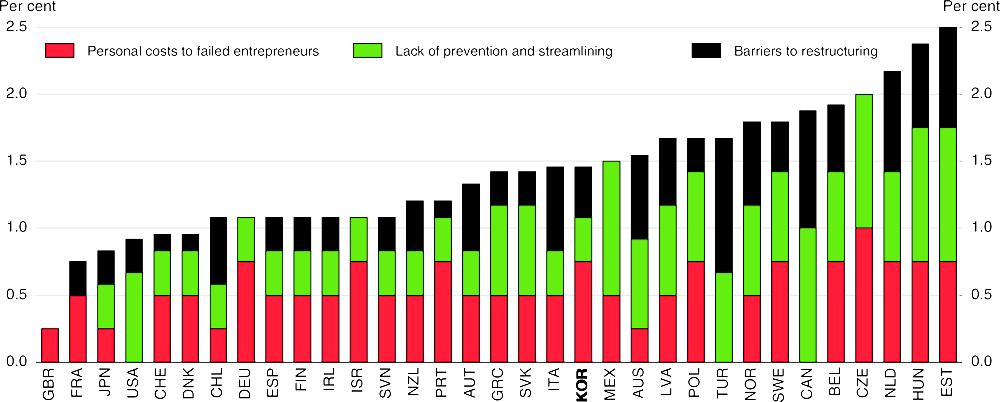

Firm entry and exit drive the “creative destruction” that leads to technological change and productivity growth. However, the firm exit rate has been falling in Korea and was the third lowest in the OECD area in 2014 (Figure 2.10), reflecting in part weakness in the insolvency regime (Adalet McGowan et al., 2017b). The problems of weak market selection, survival of non-viable firms and inefficient capital reallocation are likely to be more pronounced in economies where insolvency regimes: i) impose a high personal cost on failed entrepreneurs; ii) lack sufficient preventive measures; and iii) lack tools to facilitate restructuring. In the OECD’s indicator of insolvency regimes, Korea ranked below average (Figure 2.11), reflecting problems in three areas:

The time to discharge – the number of years a bankrupt person must wait until they are discharged from pre-bankruptcy indebtedness – is long in Korea, raising the personal costs associated with entrepreneurial failure.

Korea lacks an early warning system for bankruptcy, although the government has provided business consulting services since 2013.

Korea has an indefinite stay on assets, which stops actions by creditors to collect debts from a debtor.

Figure 2.10. The exit rate of companies is very low in Korea

The number of employer enterprise exits as a percentage of active employer enterprises, 2014 or latest year

Promoting SME innovation through R&D and international links

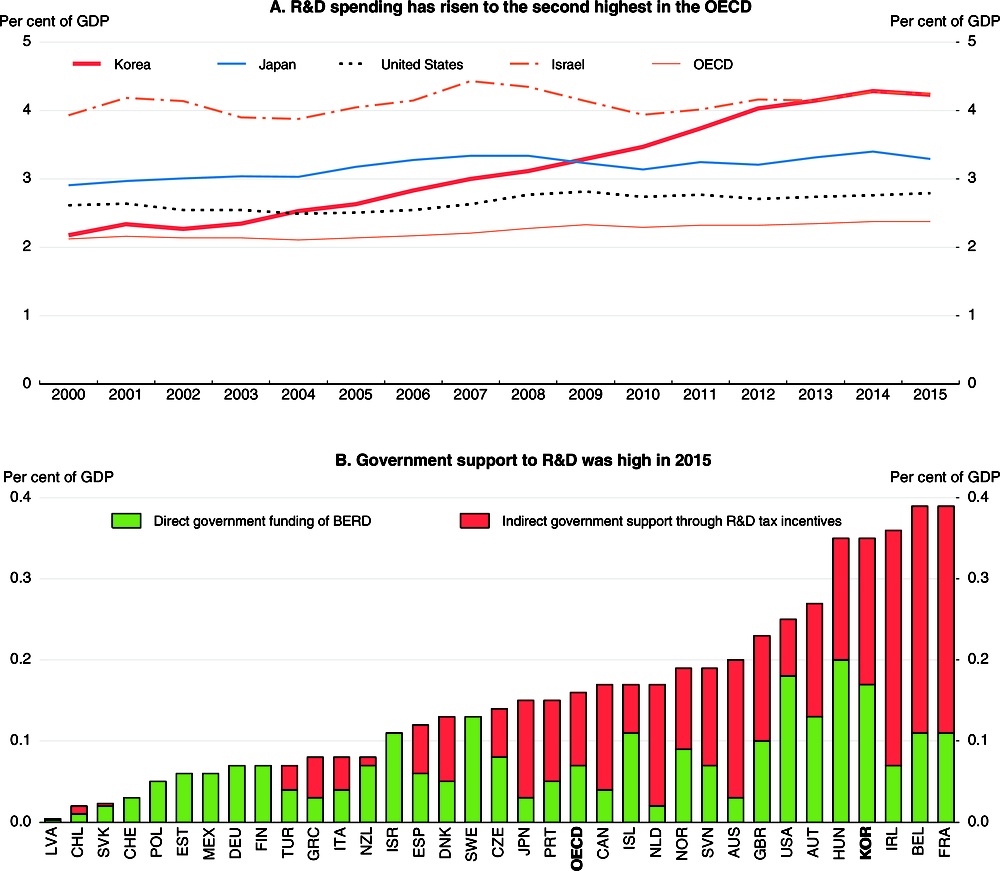

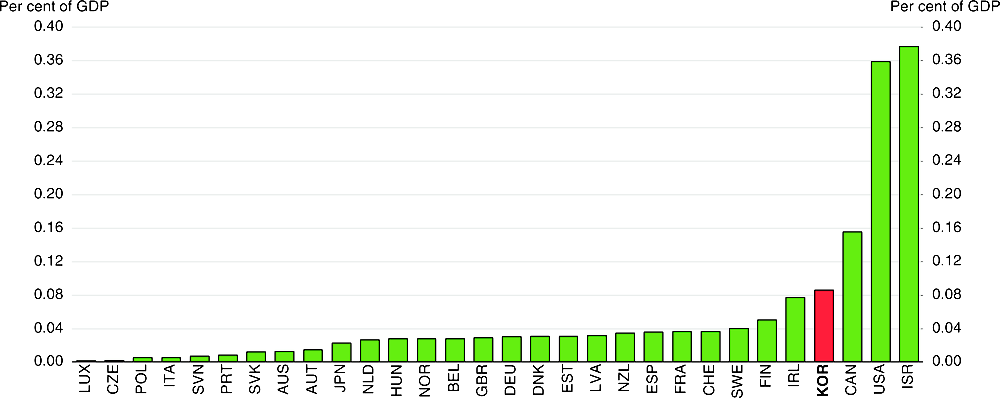

Korea’s total R&D spending has risen rapidly since 2000, reaching 4.2% of GDP in 2015, the second highest in the OECD (Figure 2.12). Business expenditure on R&D is the highest in the OECD at 3.2% of GDP, underpinned by government support equivalent to 0.35% of GDP, the fourth highest in the OECD (Panel B). To promote innovation, the government provides tax incentives for R&D, asset acquisition, technology commercialisation and human resource support.

Figure 2.11. Korea ranks slightly below average in the OECD’s indicator of insolvency regimes

In 2016; a lower score indicates a better insolvency regime

Figure 2.12. R&D spending and government support for R&D are exceptionally high in Korea

However, the traditional chaebol-led R&D model, focusing on manufacturing, cannot achieve the government’s goal of achieving a fourth industrial revolution. SMEs’ low level of investment in R&D and other knowledge-based assets has slowed their uptake of new technology, including digitalisation. SMEs account for about 20% of business R&D, compared to an OECD average of around 30% (OECD, 2016e). The lower R&D investment by SMEs reflects in part their concentration in services (see below). At present, SMEs can choose between a tax credit of 25% of spending on research and manpower development expenses or 50% of the additional spending above the average of the past year. Marginal R&D tax subsidy rates (the generosity of the tax system for a marginal unit of R&D expenditure) for Korean SMEs are relatively high at 0.25 for profit-making firms (versus an OECD median of 0.18) and 0.20 for loss-making firms (OECD median of 0.11). In contrast, the R&D tax subsidy rates for large firms are 0.04 for profit-making ones and 0.03 for loss-making ones (OECD, 2017i).

Given SMEs generally low productivity and weak financial position, it is important to ensure that R&D incentives are effective for them. The tax incentive for SMEs could be strengthened by combining a basic deduction for R&D spending, with a deduction for a certain amount of additional spending. Start-ups are typically not profitable in their early years so the R&D tax credit, which applies to the corporate income tax, does not provide any incentive to invest. Although unused credits can generally be carried forward for five years (OECD, 2017i), many start-ups do not survive that long. Allowing the R&D tax credit to be used immediately to offset other business taxes would encourage greater R&D (Noh, 2017).

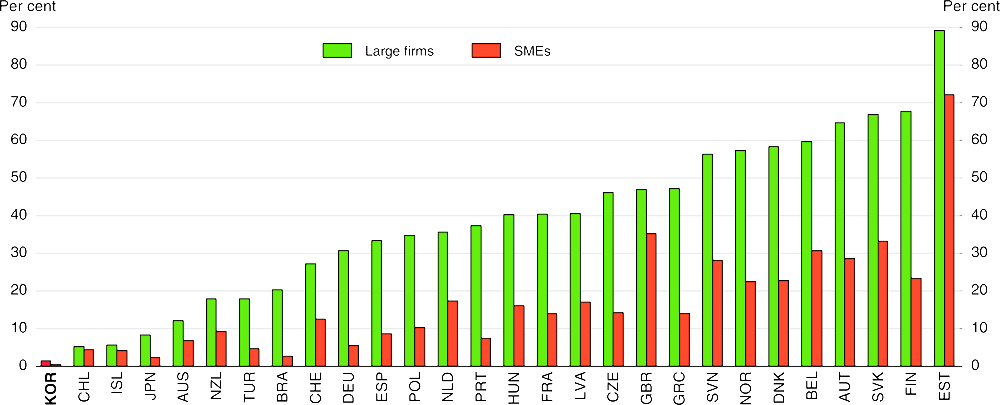

Open or network-based innovative knowledge economies can help new and small businesses participate in innovation (OECD, 2010). Digitalisation facilitates collaborative networks with multinational corporations, universities and research institutes around the world by reducing costs (OECD, 2015b). However, in Korea, both large firms and SMEs rank last in the OECD measure of international innovation co-operation (Figure 2.13). Moreover, Korea ranked third lowest in 2015 in its share of R&D funding from overseas. Korea also ranked second lowest in international co-patenting and third lowest in international science co-operation in 2013. The government has developed a plan to promote such co-operation, emphasising the creation of a global network of overseas science, technology and innovation outposts, expansion of S&T official development assistance, promotion of international joint R&D, and sharing of large R&D facilities. These measures could be usefully complemented by reducing barriers to trade and investment, which would facilitate foreign investment in R&D and help Korea connect to global science and innovation networks (2016 OECD Economic Survey of Korea).

Figure 2.13. Korean firms are less connected to global innovation networks

Firms engaged in international collaboration for innovation by firm size, 2012~141

1. As a percentage of firms engaged in product or process-innovation. For Korea, data are for 2013-15.

Source: OECD (2017f), OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2017.

Coping with labour shortages in SMEs

Raising productivity in SMEs is essential to raise wages (Figure 2.2) and overcome the chronic labour shortages in smaller firms, which reflect low wages and poor working conditions. A recent poll by the Korea Small Business Institute reported that 80.5% of SMEs are experiencing difficulty finding employees, despite rising inflows of foreign workers. The number of foreigners allowed to enter Korea on work visas to be employed at SMEs rose from 479 000 in 2012 to 549 000 in 2016. Many Korean workers shun jobs in SMEs as being underpaid and difficult. A 2016 survey of university students by the Federation of Korean Industries reported that 32% wanted to work for a big company and another 25% preferred state-run institutions. Only 5% said they wanted to work at an SME. In addition, SMEs experience a high rate of labour turnover.

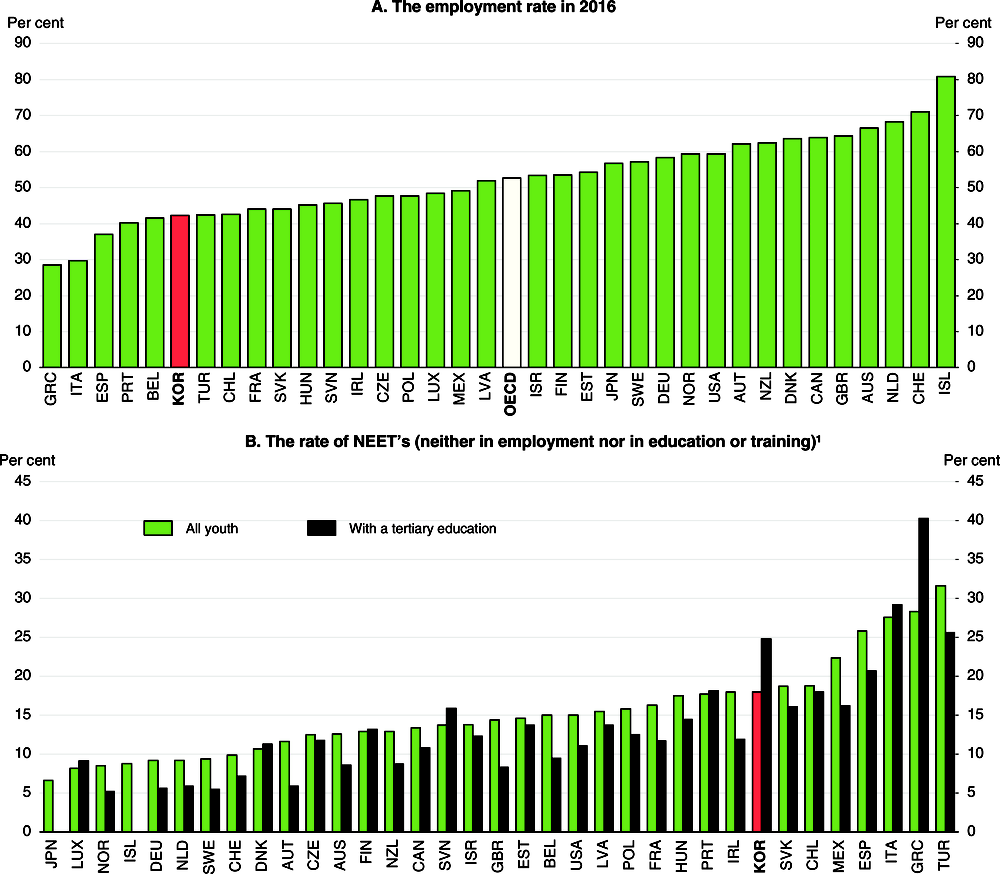

However, the labour shortage at SMEs is not due to a lack of available workers. The youth employment rate fell from 45% in 2005 to 42% in 2016, well below the OECD average of 53% (Figure 2.14). In addition, the share of youth who were neither in employment nor in education or training (NEET) was high (Panel B), although the statistics do not capture the share of youth in Korea and other countries engaged in unofficial education. Low youth employment reflects the mismatch between the skills acquired in school and those demanded by firms due to an over-emphasis on higher education and a decline in the share of students choosing vocational high schools (Kim, 2015). Indeed, the share of high schools students enrolled in vocational high schools fell from 28% in 2006 to 19% in 2015, well below the 47% OECD average. Since the 2008 global crisis, students seem to focus more on employability, reducing the share of high school graduates advancing to higher education from 83.8% in 2008 to 69.8% in 2016, but it remains high.

Figure 2.14. Korea’s youth employment rate is below the OECD average and the number of NEETs is high

1. In 2013 for the 15-29 age group. It should be noted that data on programmes that straddle the boundary between upper secondary and post-secondary education [ISCED 4] are not available in Korea and 11 other OECD countries, leading to an overestimation of the number of youth classified as NEETs.

Source: OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database); OECD (2015a), Education at a Glance 2015.

Korea is one of the few countries in which the rate of NEETs for tertiary graduates (24.8%) is higher than for the overall 15-29 age group (18.0%) (Figure 2.14, Panel B). For many university graduates, waiting for an attractive job opportunity is better than being trapped in SMEs, where job security and wages are low. Periods of inactivity have a negative long-term effect on the employment and wage prospects of youth. The mismatch problem is high as well among youth who find jobs. For workers in the 15-29 age group, 37% were in jobs that did not match their field of study and literacy skills (OECD, 2014).

Reducing labour shortages in SMEs by addressing the mismatch in the labour market

The low productivity and wage levels in SMEs discourage young people from accepting jobs at smaller companies, thus perpetuating low productivity. Breaking this vicious circle requires helping young people enter the labour market earlier through strengthened hands-on vocational education that begins at the secondary level. The government is changing the vocational education system at both the secondary and tertiary levels from a “theory-based” approach to “practice-based”. It draws on 897 National Competency Standards developed by public and private experts that set out the knowledge, skills and attitudes that are required to perform a particular occupation. The government introduced Meister schools in 2008 to improve the negative social perception of vocational education. The Meister schools, which now total 46, allow students to pursue studies and internships simultaneously. In 2015, the government created work-study dual programmes at the secondary level. Finally, the government recently introduced “blind recruitment” in all 332 public institutions to ensure that people are hired based on their skills rather than other factors, such as academic achievements, family background and personal characteristics. The government is now encouraging private firms to follow suit.

A number of policies are needed to raise youth employment. First, breaking down labour market dualism would reduce the number of educated youth who prefer waiting for an attractive job opportunity to the stigma of non-regular employment, which is most prevalent in SMEs. Second, further enhancing the link between firms and all types of education is essential to address mismatch. Students in Meister schools and work-study dual programmes account for only 9% of vocational high school students. Third, the capacity of vocational high schools is too low to meet demand. The government should expand capacity to reach its target of raising the share of high school students enrolled in vocational schools to 29% by 2022. In addition, the introduction of blind recruitment may reduce discrimination. However, it may also discourage students from studying hard to qualify for admission to high level educational institutions.

Ensuring adequate skills in the workforce of SMEs

In addition to reducing the shortage of workers, it is necessary to ensure that education and training provide workers with enough skills, including digital skills, to achieving the government’s goal of making SMEs drivers of innovation and digitalisation. SMEs are limited by a lack of skilled manpower and their capacity to train their workers is low compared to large firms (OECD, 2013a). In particular, promoting lifelong learning will be essential in this regard given the large gap in computer skills between generations. Indeed, the ability of youth (16-24) to solve problems using computers is one of the highest in the OECD, while that of older workers (55-64) is among the lowest (OECD, 2013b). However, the share of older workers receiving vocational education and training in Korea is low. In addition, Korea should expand the number of visas for employment at SMEs to allow high-skilled foreign workers, in addition to those with low skills, to fill shortages in SMEs. Finally, the tax code supports experts who directly engage in research activities at SME research institutes. They are allowed to deduct up to KRW 200 000 (USD 185 000) per month for research expenses (Noh, 2017).

Enhancing SME productivity by strengthening linkages with global markets

The share of SMEs in Korea’s total exports dropped from 21% in 2009 to 18% in 2015. SMEs have not benefited fully from the rapid growth of emerging economies and the proliferation of FTAs, nor have they become major players in global value chains (GVCs) in Asia. The share of small firms that participate in global value chains is the lowest in the OECD. Instead, SMEs are primarily focused on domestic demand: exports accounted for only 8.7% of sales of manufactured products by SMEs in 2015 (Table 2.4). In addition, the proportion of retail sales has declined, while sales to other SMEs and to large firms have risen, reflecting the growing importance of subcontracting. In addition, SMEs’ indirect contribution to exports appears limited: value added from domestic services, where SMEs account for 90% of employment, accounted for only 26.0% of gross exports over 2010-14, well below the 40% OECD average (Figure 2.15). Moreover, Korea is one of the few countries to record a significant decline since the late 1990s.

Table 2.4. SMEs are focused primarily on domestic markets

Percentage of sales of manufactured products by customer

|

Exports |

Domestic sales |

Total |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sales to large firms |

Sales to other SMEs |

Sales to public institutions |

Retail sales |

Sub-total |

|||

|

2004 |

8.4 |

29.8 |

46.1 |

3.6 |

12.1 |

91.6 |

100.0 |

|

2015 |

8.7 |

29.9 |

47.6 |

4.9 |

8.9 |

91.3 |

100.0 |

|

Difference |

0.3 |

0.1 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

-3.2 |

-0.3 |

0.0 |

Source: Statistics Korea, KOSIS database.

Exports provide an opportunity for expansion and job creation (Moon, 2017). According to a government survey of more than 2 700 SMEs, those that are export-oriented (defined as a firm in which direct exports account for at least 29.8% of their total sales) are more focused on R&D, which accounted for 10.7% of their sales, compared to less than 3% for all SMEs. Exports by SMEs could be increased by: i) better utilising digital platforms to enhance linkages with the global market; ii) making greater use of ICT convergence technology, as noted above; iii) increasing participation in high value-added GVCs, in part by eliminating trade and investment barriers; and iv) developing trade in services.

Figure 2.15. The contribution of services to exports is relatively low in Korea

Domestic services value added as a share of gross exports, average over 2010-14

Digital platforms provide new opportunities for small enterprises to tap into foreign markets (OECD, 2016a). However, only 12.4% of exporting SMEs in Korea used e-commerce, according to a government survey (Chang and Lee, 2017), as firms rely more on face-to-face contact. In companies with more than 31 years of export experience, the rate of e‐commerce utilisation is only 4%. SME exporters give a number of reasons for not using e‐commerce: i) they are not interested in it (27%); ii) they lack the professional manpower to use it (26%); iii) they are not familiar with it (25%); and iv) the cost of constructing such systems is too high (15%). Moreover, among those using e-commerce, the major platform used is the homepage of the exporting company (49%), with smaller roles for globally popular platforms (29%) and the export target country’s major platform (14%). Policies to educate SMEs about the possibilities of using e-commerce to export, help them train the necessary manpower and reduce the cost of implementing such systems would help increase SME exports (OECD, 2017e and 2017g) and promote “global start-ups” (Box 2.3). The government’s SME Export Support Centre should develop an on-line platform to facilitate contacts between SMEs and overseas buyers. However, success in exporting ultimately depends on overcoming the problems that hamper productivity in Korean SMEs that are discussed in this chapter.

Korea is active in “Factory Asia”, as the import content of its exports was 38% in 2014, compared to the OECD average of 30%. A quarter of export-oriented SMEs have overseas production bases, of which three-quarters are participating in GVCs. Firms that participate in GVCs are more productive than non-participating firms. However, the productivity gap is much bigger among large firms than among small firms, as more than half of Korea’s SME exporters are concentrated in low value-added work such as finished goods assembly (32.6%) and parts production (20.2%) (Kim et al., 2016).

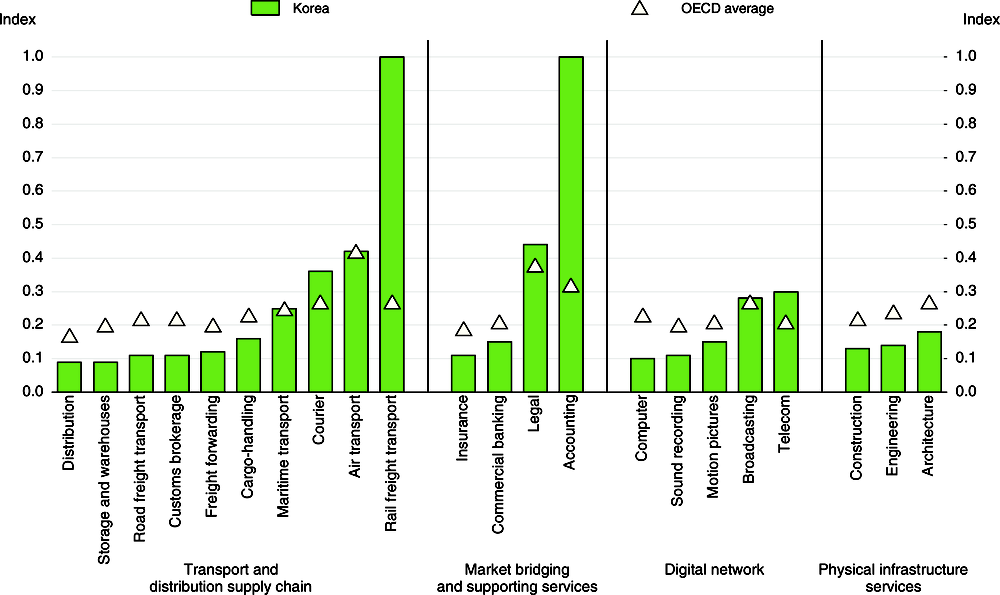

Lowering Korea’s barriers to trade and investment, which were the second highest in the OECD in 2013, would promote the participation of SMEs in high value-added GVCs. Given the concentration of SMEs in services, increasing trade in services would help boost their productivity. Many of the key trade barriers affect services. Korea’s service trade restrictiveness index is below the OECD average in 14 out of 22 sectors but still above it in some sectors that play key roles in GVCs, such as telecom, legal and accounting services and rail freight transport (Figure 2.16). In addition, enhancing institutional transparency and regulatory reform (see below) and harmonising standards and technical regulations would reduce regulatory costs.

Figure 2.16. Korea should reduce barriers to trade in key services

In 2017 or latest year1

1. The STRI indices take values between zero and one, one being the most restrictive. The STRI database records measures taken on a “Most Favoured Nation” basis while excluding preferential trade agreements.

Source: OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (database).

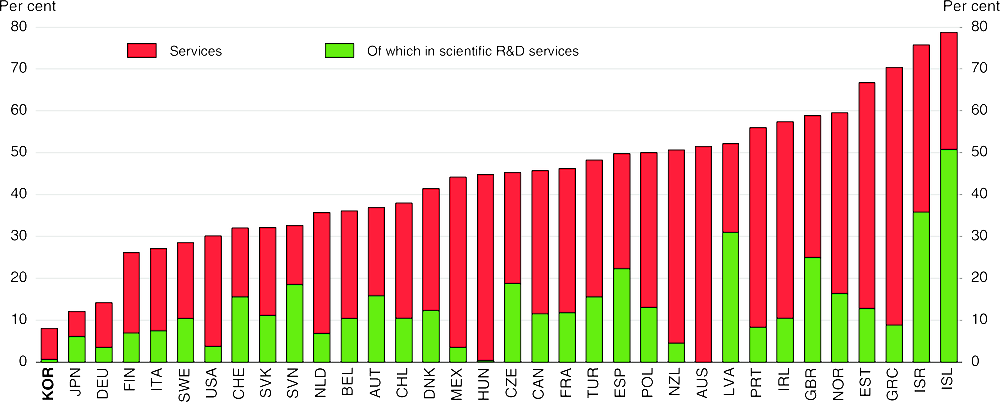

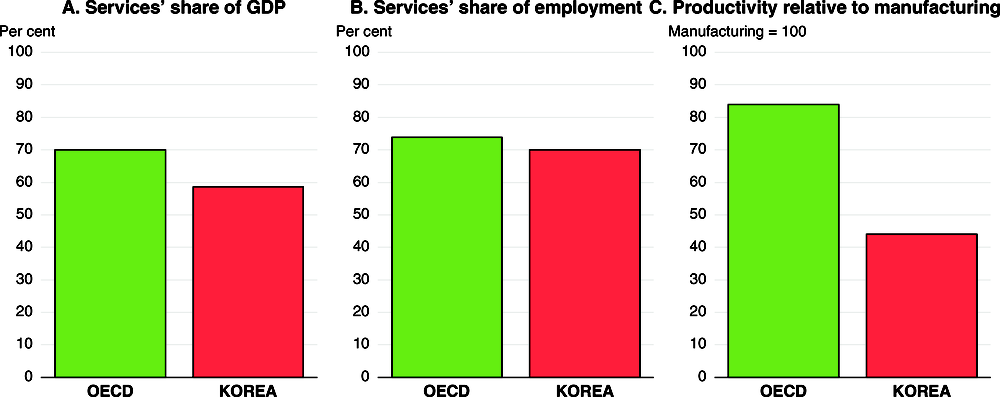

Increasing SMEs’ direct exports of services would also be beneficial, although it would be a challenge given that Korea’s service sector is relatively undeveloped. Export-led development has siphoned capital, talent and other resources away from services and toward manufacturing. Services accounted for 58.6% of Korean GDP in 2017, well below the OECD average, and accounted for 70.1% of employment (Figure 2.17). The share of the service sector in employment has been on an upward trend, while its share of output has been stagnant. The 46% gap in the level of economy-wide labour productivity between Korea and the top half of OECD countries is largely explained by low productivity in services, which was 44% of that in manufacturing in 2017, compared to an average of 84% in the OECD (Panel C). Services also play a relatively small role in international trade. While Korea was the world’s eighth-largest exporter of goods in 2016, it ranked 17th in service exports.

Figure 2.17. Service sector productivity is low in Korea

In 20171

1. Based on 2010 prices for value added.

Source: OECD National Accounts Statistics (database); OECD Structural Analysis Statistics (database).

The first priority to increase SME participation in global trade would be to raise the share of domestic services value added in gross exports from its current low level (Figure 2.15). However, this requires addressing the factors that keep its productivity low (Jones, 2009). One reason is that services account for only 8% of Korea’s business expenditure on R&D, the lowest in the OECD (Figure 2.18). Moreover, services accounted for only 3.4% of public R&D spending in 2017. The government aims to raise the share to 6% during the next five years. In addition, the measures discussed above to make the R&D tax credit more effective for SMEs would be beneficial.

Figure 2.18. Korea R&D in services is the lowest in the OECD

As a percentage of business enterprise R&D in 2015

Box 2.3. Global start-ups

“Global start-ups”, a term applied to young firms heavily involved in international trade, have made large contributions to innovation and employment, two top priorities of the government. In 2016, 490 “innovative start-ups" that were less than seven years old were surveyed (Lee et al., 2017). Of them, 124 are classified as global start-ups based on three criteria: i) they entered overseas markets within three years after their establishment; ii) they are active in at least two foreign countries through, for example, joint ventures or strategic alliances; and iii) their exports account for more than 25% of total sales. On average, they exported some 50% more than other innovative start-ups.

Global start-ups achieve more employment growth, raising the number of employees by seven over 2009-15, a larger increase than in enterprises that attract venture capital investment (but may not qualify as global start-ups). Meanwhile, non-global start-ups increased employment by five persons. The ability of global start-ups to produce internationally-competitive products from the outset suggests relatively strong innovation capabilities. The share of their products using breakthrough technology not seen before in Korea or the world was 28.5% compared to 19.0% for non-global start-ups.

Only 38% of the global start-ups participated in government programmes providing assistance. Instead, they relied primarily on private-sector networks, such as their personal contacts and domestic trading companies, which are able to provide objective evaluation and sufficient support. This suggests that private-sector experts with a proven track record are better able to provide the necessary assistance to start-ups. Moreover, the complexity of joining government programmes, which tend to require a record of success, discourages the participation of start-ups. Improving the programmes would allow them to complement the private-sector networks of the start-ups and increase the number of innovative start-ups that turn into global start-ups.

An ecosystem to promote dynamic SMEs

Regulatory reform to reduce the burden on SMEs and create new opportunities

In 2013, it was estimated that 8 291 regulations – 59% of the total number – applied to SMEs (Table 2.5), reflecting their prevalence in services. Economic regulations covering entry, price, trading and quality, which can distort the functioning of markets, accounted for about one-third of the regulations. Another third were social regulations on environment, industrial accidents, consumer safety and social discrimination. In addition more than 1 800 SME regulations applied to the creation of enterprises (Panel B). In sum, the creation of SMEs and their business activities are subject to a large number of regulations. As in other countries, regulation is a key obstacle to the emergence of dynamic SMEs (OECD, 2016b). In line with its goal of making SMEs the driver of the fourth industrial revolution, the government plans to lower the cost of starting firms and reduce the regulatory burden on existing firms. Potential entrepreneurs in Korea face high start-up costs at 14.6% of per capita gross national income, four times higher than the 3.1% OECD average (World Bank Group, 2017). It is also far above other Asian economies such as China (0.6%) and Chinese Taipei (2.0%).

Table 2.5. There are a large number of economic regulations on SMEs1

|

A. By type of regulation (in 2013) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Type of regulation |

Number of regulations |

Per cent of total |

|

|

Economic regulations |

Entry |

154 |

1.9 |

|

Price |

1 012 |

12.2 |

|

|

Trading |

1 092 |

13.2 |

|

|

Quality |

606 |

7.3 |

|

|

Sub-total |

2 864 |

34.5 |

|

|

Social regulations |

Environment |

806 |

9.7 |

|

Industrial accidents |

423 |

5.1 |

|

|

Consumer safety |

1 440 |

17.4 |

|

|

Social discrimination |

279 |

3.4 |

|

|

Sub-total |

2 948 |

35.6 |

|

|

Administration regulations |

2 479 |

29.9 |

|

|

Total |

8 291 |

100.0 |

|

|

B. Economic regulations on SMEs by type of activity (in 2013) |

|||

|

Type of regulation |

Number of regulations |

Per cent of total |

|

|

Creating an enterprise |

Founding |

1 247 |

15.0 |

|

Building |

310 |

3.7 |

|

|

Location |

264 |

3.2 |

|

|

Sub-total |

1 821 |

22.0 |

|

|

Business activities |

Administration |

2 143 |

25.8 |

|

Production |

1 075 |

13.0 |

|

|

Sales |

912 |

11.0 |

|

|

Personnel |

635 |

7.7 |

|

|

Finance |

442 |

5.3 |

|

|

Safety |

407 |

4.9 |

|

|

Environment |

343 |

4.1 |

|

|

International trade |

208 |

2.5 |

|

|

Technology |

62 |

0.7 |

|

|

Sub-total |

6 227 |

75.1 |

|

|

M&As and business transition |

Merger |

84 |

1.0 |

|

Sale of assets |

4 |

0.0 |

|

|

Sector switching |

1 |

0.0 |

|

|

Sub-total |

89 |

1.1 |

|

|

Family business succession |

65 |

0.8 |

|

|

Closure & company clean-up |

89 |

1.1 |

|

|

Total |

8 291 |

100.0 |

|

1. Regulations either legally limited to SMEs, pertaining to sectors where practically all firms are SMEs or cited by SME associations as important to their member firms.

Source: Cho and Kim (2013).

One major obstacle to firm creation is Korea’s positive-type regulatory system, which prohibits everything except what is specifically allowed. One step towards a negative-type regulatory system (which allows everything except what is specifically prohibited) is the government’s plan to liberalise regulations in specific geographic areas and industries, notably ICT (Office for Government Policy Coordination Prime Minister’s Secretariat, 2017). This is to be accompanied by “regulatory sandboxes”, which allows the temporary provision of licenses in sectors using new technology (World Bank Group, 2017). This approach is being used in a number of countries, including Japan, which will soon apply it to automated driving and long-range drones (Nikkei Asian Review, 2017). An initial step in this regard in Korea was a 2015 law that created a type of regulatory sandbox to promote the ICT sector. However, by mid-2017, only three cases had been dealt with and it took an average of 133 days to receive temporary permission (Choi et al., 2017). Using regulatory sandboxes effectively would help Korea shift to a comprehensive negative-list regulatory system.

A second obstacle is that the regulatory burden tends to be relatively greater on SMEs than on large enterprises (OECD, 2017h). Indeed, the uncertainty, complexity and inconsistency of regulation are sometimes greater problems for SMEs, which have fewer resources than large firms, than the regulation itself. Of the 8 291 regulations applied to SMEs in 2013, only 1.7% allowed differential treatment for SMEs. A number of countries are taking steps to ease regulatory burdens on SMEs. For example, the United States introduced the “Regulatory Flexibility Act” in 1980 to allow differences in regulations applied to SMEs and large firms. Korea should make efforts to reduce the burden of regulatory compliance, focusing on SMEs, while ensuring that key economic and social objectives, such as those related to the environment, safety and labour rights, are met.

Protecting SMEs by strengthening the stringency of regulation on large enterprises should be avoided as the overall economic effect would be negative. General equilibrium models suggest that the positive effect of regulatory reform is greatest when it applies to both large enterprises and SMEs (Jung, 2016). Moreover, the positive impact of regulatory reform that is applied only to large firms is greater than that applied only to SMEs. Similarly, the negative effect of regulation imposed only on large firms is more negative than regulation imposed only on SMEs. In short, using regulations to improve the position of SMEs relative to large enterprises is counter-productive, while trying to eliminate unfair business practices. In general, the objective should be to remove regulations that inhibit competition by large firms and SMEs, while achieving social objectives.

Using public procurement to assist SMEs

SMEs are supported through a broad range of programmes in Korea to boost their share of public procurement of goods and services. Indeed, the law sets a target of 50% for SMEs’ share of total public procurement, which accounts for a 21.7% of government spending. SMEs captured 54% of contracts awarded through competition in 2014, up from 30% in 2009. An OECD study concluded that public procurement in Korea is “overly focused on SMEs, to the exclusion of large suppliers” (OECD, 2016f).

Public procurement policies to benefit SMEs have the unintended side effect of increasing dependency on public support and slowing productivity gains. SMEs chosen for public procurement in 2009 had significantly lower productivity in 2011 and a greater chance of survival than other firms (W. Chang, 2017). Public procurement policies thus result in a moral hazard by encouraging SMEs to depend on the procurement market for survival without improving their productivity to the level demanded by the market. The government should reduce this distortion by tightening the screening process for SMEs involved in public procurement and monitoring their performance. In order to promote innovation by SMEs, government procurement programmes for SMEs and start-ups are focusing more on technologically-advanced products.

Addressing other obstacles to the development of SMEs

Making SMEs a driver of innovation to achieve the fourth industrial revolution requires shifting from a “fast-follower” approach that has driven Korea’s catch-up to a “first-mover” strategy. Under the fast-follower model, the government has supported winners who were able to compete in international markets. The government’s science, technology, industrial and education policies have focused on repeating past successes, while failing to create an innovative ecosystem (Lee and Choi, 2017). Bureaucratic decisions to select and support national champions have interfered with technological decisions and stifle innovation. The costs associated with administrative burdens and red tape are relatively higher for SMEs than for large enterprises, thus hamstringing innovation in SMEs. Shifting to a fast‐follower strategy requires a fundamental shift in government strategy, as well as in the education system and corporate practices. In sum, direct interference by the government should be reduced.

The criteria to receive special treatment as an SME, which were based on the number of regular workers, sales, capital and total assets until 2015 (Box 2.2), created disincentives for SMEs to grow and lose their preferential treatment. This led to a “bunching effect” as firms stopped expanding once they reached the various thresholds in order to remain eligible for government support (the “Peter Pan syndrome”). This led to a new definition of SMEs in 2015 that is based on total assets and sales. However, there is still bunching as SMEs limit assets and sales to stay below the threshold. One strategy of enterprises that want to maintain SME status is to split the firm in two (Kim, 2017). The disincentive to growth also applies to mid-size firms, which must keep their total assets below KRW 10 trillion to continue receiving special benefits.

Special tax treatment for SMEs is one of the major incentives that discourages firms from growing and graduating from SME status, which has a negative effect on a country’s growth (OECD, 2015c). Moreover, it also gives incentives to artificially split up into different businesses to continue benefitting from the preferential tax treatment. Tax support for SMEs in Korea is high and its coverage is broad compared to other OECD countries, and continues to favour manufacturing. In most OECD countries, preferential tax treatment applies only to firms with less than 50 employees, while in Korea all SMEs, which account for 99.8% of companies, and mid-size companies, are eligible. A range of tax credits are offered to firms that, for example, make investments that create jobs, increase their employment of regular workers and convert non-regular workers to regular status. Reducing the range of SMEs receiving preferential tax benefits would weaken the Peter Pan syndrome. The negative effect on company growth from government subsidies to specific firm classes should be reduced by scaling back their generosity and phasing out benefits gradually for firms that graduate from SME or mid-size firm status.

Subcontracting relationships (Chapter 1) have a big impact on SME performance, given that they account for a large share of SME sales (Table 2.4). The sales and total assets of SMEs that subcontract with large and mid-size enterprises are larger than for SMEs that do not subcontract. Indeed, the sales and assets of the large companies are correlated with those of the subcontracting SMEs. However, the increase in SMEs’ sales and assets is not accompanied by a rise in their operating profit ratio (Chang and Woo, 2015). This reflects their generally weak bargaining power relative to large firms. Even among mid-size firms, 23% reported that they had been asked to reduce their delivery prices by 3% to 5% in 2015 (Association of High Potential Enterprises of Korea, 2017). This has negative implications for productivity as subcontracting SMEs and mid-sized firms have little incentive to become more efficient. The virtuous circle of reinvesting profits to become more productive is broken. This also has implications for government support for SMEs, which may be passed on to the large firms (W. Chang, 2018). This so-called “straw effect” is statistically significant in the ICT sector, where the government is increasing SME support to promote the fourth industrial revolution.

Promoting entrepreneurship to increase the number of start-ups

Increasing enterprise creation boosts “labour productivity growth, with evidence pointing to a correlation between start-up and churn rates, and productivity growth, although, the impact on recorded labour productivity growth may not be immediate” (OECD, 2016b). Korea was ranked 21st in the OECD according to the 2018 Global Entrepreneurship Index (Figure 2.19). In the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor international survey, Korea ranked 37th among the 60 countries surveyed. Moreover, only 34% of the Korean population has a favourable perception of start-ups, far below the OECD average of 49% (OECD, 2014). These indicators suggest weaknesses in entrepreneurship that should be addressed to promote inclusive growth (Park, 2017). In November 2017, the government launched a “Plan to Create an Ecosystem to Nurture Innovative Start-ups” (Box 2.4), which is similar to the 2013 “Measures to Improve the Venture Start-up Ecosystem” (2014 OECD Economic Survey of Korea). Both include tax incentives for business angels, public-private venture capital funds, measures to promote M&As and strengthening KOSDAQ.

Figure 2.19. Korea is ranked 21st in the 2018 Global Entrepreneurship Index

Source: Global Entrepreneurship Development Institute (2018), Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018.

Box 2.4. A government plan to create an ecosystem to nurture innovative start-ups

The plan announced by the government in November 2017 set three goals and policies to achieve them.

1. Creating a start-up-friendly environment to foster entrepreneurship

Support talented individuals launching diverse start-ups: i) encourage spin-offs from existing firms by introducing a “start-up leave” system, which allows entrepreneurs to return to employment in case of failure; and ii) allow professors in universities to have more flexible employment arrangements to encourage start-ups.

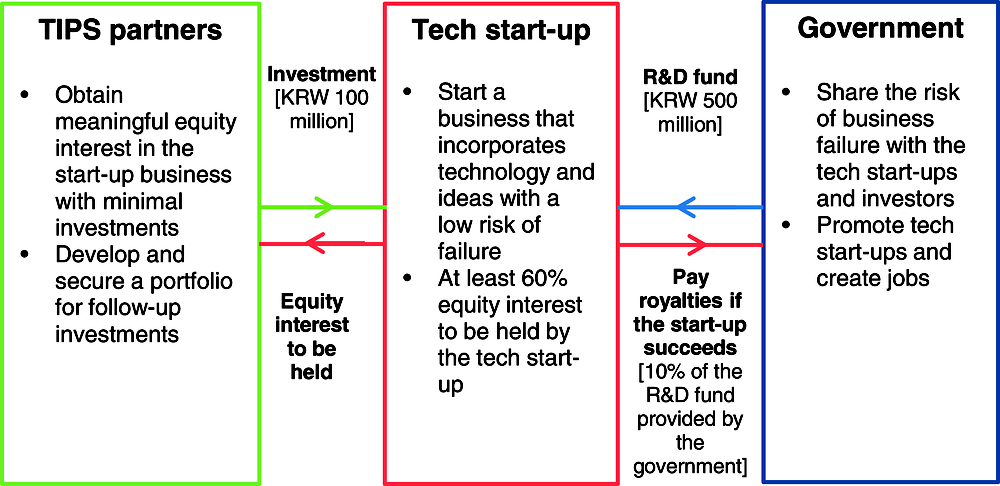

Transform the venture start-up support system into a private sector-driven system. Utilise the Tech Incubator Programme for Start-ups (TIPS) as part of the government’s overall policy on start-ups.

Provide support during the seed stage of start-ups, such as office space and online and offline networking opportunities. Utilise the Pangyo Techno Valley, government properties and public institutions as “makerspaces” to facilitate the exchange of ideas and commercialisation of innovative ideas.

Assist start-ups during their developmental stages, including financing, participation in public procurement, securing markets, including overseas, thereby helping them survive the so-called “Valley of Death” and grow into strong mid-size enterprises.

2. Expanding financing opportunities and tax incentives

Set up an “innovation adventure fund” worth KRW 10 trillion (USD 9.3 billion): i) the public sector will contribute KRW 3 trillion through fiscal expenditure and policy-based loans and the private sector will provide KRW 7 trillion; and ii) provide a comprehensive funding package for venture business throughout different stages, from commercialisation of ideas to market launch, and from M&A to business reorganisation.

Promote technology financing based on the firm’s profitability and the future value of the technology. Provide more educational programmes on technology financing, for example at the Korea Banking Institute.

Diversify tax incentives for start-up investment to attract investment by a broader group of investors: i) double the amount of the angel investment tax exemption that is 100% deductible from the current level of KRW 15 million (USD 13 893); ii) reintroduce the tax exemption for gains from stock options, iii) increase the tax exemption for employee stock ownership from KRW 4 million to KRW 15 million; and iv) introduce tax incentives for investment in start-up investment associations to encourage investment in small amounts.

3. Establishing a virtuous cycle between start-ups and investment

Gradually phase out joint surety (guarantees), which pose a heavy burden on entrepreneurs’ family and friends in the case of bankruptcy, making it difficult to re-start the company. Policy-based financing institutions will abolish it within the first half of 2018 and private institutions will phase it out gradually.

Facilitate Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) and M&As: i) strengthen the independence of the KOSDAQ Market Committee to boost the KOSDAQ and KONEX markets; ii) encourage investment from pension funds, iii) boost incentives for large enterprises to take part in M&As; and iv) attract foreign venture capital investment in domestic M&As.

Prepare measures to prevent technology theft: launch a task force at the Korea Fair Trade Commission this year and expand its investigative mandate over technology theft.

Source: Ministry of Strategy and Finance (2017), Press Release (2 November).

Promoting opportunities for female entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurial opportunities in Korea for women are relatively limited compared to men. The share of female entrepreneurs (defined as self-employed persons with employees and own account workers) was 14% in 2016, compared to the 10% OECD average. However, it was well below the 26% rate for Korean men, leading to the third-largest gender gap in entrepreneurship in the OECD (Figure 2.20).

Figure 2.20. The gender gap in the entrepreneurship rate in Korea is high

The share of male entrepreneurs minus the share of female entrepreneurs

1. Defined as self-employed with employees and self-account workers as a share of total employed.

Source: OECD (2017c), OECD Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2017.

Female entrepreneurs cited six key disadvantages in a 2015 survey: i) balancing work and family responsibilities (80%, i.e. only 20% did not feel any difficulty); ii) adapting to male-centred business practices (76%); iii) obtaining financing (70%); iv) loss of business opportunities due to their perceived passive management (69%); v) discrimination against women in business (69%); and vi) operating in male-oriented networks that limit participation by women (Korea Women’s Entrepreneurship Association, 2015). Regarding financing, the initial capital of female entrepreneurs in 2015 was only 62% of that of men, which is close to the gender wage gap. Difficulties in financing have reduced opportunities for female entrepreneurs to enter high value-added industries, as discussed above.

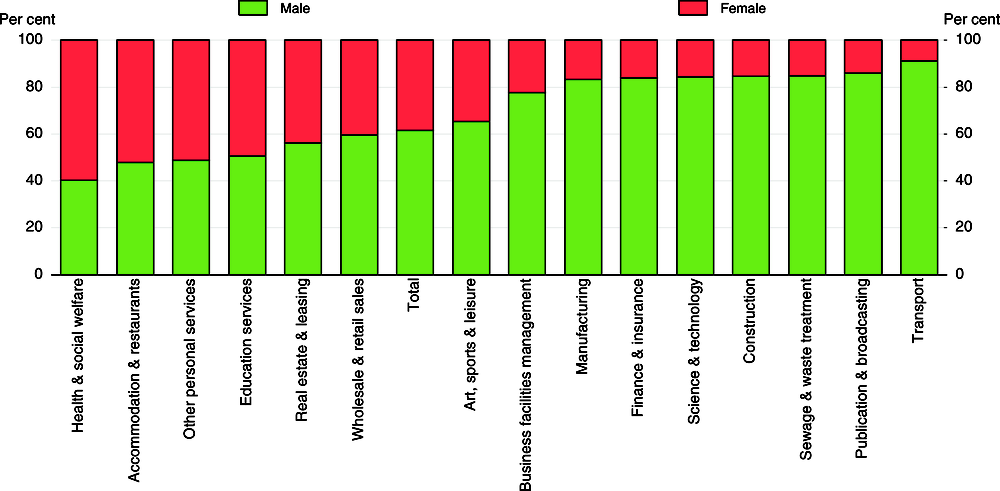

Developing entrepreneurship opportunities for women is a priority to achieve inclusive growth. Entrepreneurship enables women to avoid the dualistic labour market, which leads to the largest gender wage gap in the OECD (37%), reflecting the fact that 41% of female employees are non-regular workers. The attractiveness of starting one’s own business has increased during the past few years of relatively slow growth and slack labour market conditions. Although start-ups by women in Korea rate highly in terms of job creation and business stability (Korea Women’s Entrepreneurship Association, 2015), female entrepreneurs are concentrated in basic livelihood sectors, such as health and social welfare, accommodations and restaurants, other personal services and educational services (Figure 2.21), reflecting in part their more limited access to financing and their educational background. Such sectors are characterised by fierce competition and relatively high failure rates. Relatively few female entrepreneurs create firms in manufacturing or high value-added sectors such as finance and insurance and science and technology. In addition, nine out of ten firms started by female entrepreneurs have less than ten employees.

Figure 2.21. Female entrepreneurs are concentrated in certain industries

Within seven years after creation of the firm

The government is investing in female entrepreneurs, using a fund aimed at women. The fund, which totalled KRW 54 billion (USD 50 million) over 2014-17 is to be increased to KRW 90 billion over 2018-22. One of the criteria for firms to qualify for support from the fund for female entrepreneurs is to have women account for 35% of their employees, even if the entrepreneur is male. However, only 114 of the 712 persons receiving support from the Start-up Academy Programme in 2016 were women (Table 2.6). Female start-up’s share of support for exports, funding and R&D was even smaller, though increases were planned for 2017. At a minimum, support for female start-ups should match that for male start-ups and the number of women receiving such support should be increased. Government support should be combined with greater market-based financing (see below). Experience shows that to increase the number of start-ups by women, it is not enough to simply encourage more women to start companies. A key is to have more women join venture capital firms (Raina, 2016).

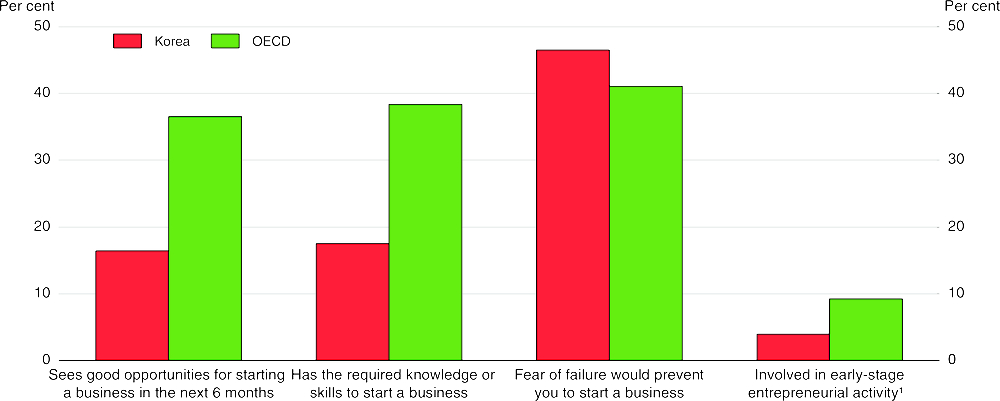

Strengthening the entrepreneurial spirit of youth

The entrepreneurial spirit of Korean youth has dimmed following the venture capital boom of the late 1990s. In the early 2000s, 32% of the chief executive officers of Korean venture companies were in the 20 to 30 age group, but this share fell to 10% in 2010. Korea had the second-lowest percentage of young people age 18 to 34 involved in early-stage entrepreneurship in the OECD in 2012 (Figure 2.22). Youth were held back by a seeming absence of opportunities, the lack of the necessary knowledge and skills to start a firm and a fear of failure. This weakening of youth’s entrepreneurial spirit will frustrate Korea’s objective of achieving growth led by SMEs and start-ups. Measures to improve attitudes toward entrepreneurship are thus a priority (Kim, 2014).

Table 2.6. Government support for female entrepreneurs is low

|

R&D support (billion won) |

Funding support (billion won) |

Export support (number of firms) |

Support from the Start-up Academy Programme (number of persons) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Government support for female entrepreneurs in 2016 |

61.3 |

482.6 |

1559 |

114 |

|

Share of total support |

6.5 |

10.7 |

15.0 |

16.0 |

|

Government support for female entrepreneurs in 2017 |

75.8 |

430.2 |

2083 |

266 |

|

Share of total support |

8.0 |

12.0 |

18.0 |

28.0 |

Source: Ministry of SMEs and Start-ups (2017c), Promotion Plan for Female’s Business Activities.

Figure 2.22. Korea’s entrepreneurship rate for youth is far below the OECD average

Percentage of population between the ages of 18 and 34 in 2012

1. Defined as the share involved in a nascent or new business.

Source: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2013).

First, it is essential to improve the image of entrepreneurship and the capacity of youth to become entrepreneurs through education beginning in primary school. Korea has been running the “Bizcool” programme in primary and lower secondary schools since 2002, but it covered only 15 primary and ten middle schools in 2013. Entrepreneurship education is being introduced as a regular course in all primary and secondary schools in 2018, including after-school “start-up classrooms”. The programme should draw on the OECD’s Entrepreneurship 360 project. The Start-up Leading University (SLU) programme, which has a significant impact, is currently run by three separate ministries. Management should be combined in one ministry. In addition, leaves for students creating a start-up should be extended and more academic credit should be given for those engaged in entrepreneurial activities.

Second, the infrastructure for start-ups needs to be improved outside of the Seoul capital region. Surveys indicate that 77% of university students outside the capital region are very interested in starting a business, compared to only 25% of those inside the capital region (Lee et al., 2012). However, the entrepreneurial infrastructure as well as the human resources and education systems to mentor young entrepreneurs are concentrated in the capital region. In November 2017, the government announced that it would redesign the 19 Centres for Creative Economy and Innovation that have been established throughout the country as regional innovation hubs (Ministry of SMEs and Start-ups, 2017b), which should help reduce the infrastructure gap.

Third, it is important to reduce the risk of failure to encourage greater entrepreneurship, in part by facilitating second chances for entrepreneurs who have experienced failure. The average debt, including tax delinquency, borne by the head of a bankrupt firm in 2017 was KRW 356 million (USD 330 000). Helping failed entrepreneurs cope with the high debt is essential to ensuring second chances. In 2017, the government took some measures to reduce their debt burden (MOSF, 2017):

Companies receiving loans have co-guarantors, who are responsible for the debt if the borrowers are unable to pay. The impact on the co-guarantors is one of the factors that make entrepreneurs avoid bankruptcy at all costs. The government has decided to abolish the requirement for co-guarantees on loans by four public institutions in 2018.

Failed entrepreneurs who re-start their company or accept employment will be forgiven tax arrears of less than KRW 30 million (USD 27 785).

The monthly restriction on their spending is planned to be raised from KRW 1.5 million to KRW 1.8 million (USD 1 667).

Measures to promote senior entrepreneurship

As noted above, the early departure of employees from firms – before age 50 on average – prompts a large number to create small firms using their retirement allowance. Many of these “necessity-driven” start-ups have little capital and technology. The policies to encourage entrepreneurship by women and youth through education, training support and providing infrastructure should also be extended to older persons to help them succeed as entrepreneurs. Creating positive awareness of entrepreneurship as a late-career option could help remove negative bias against older persons, which acts as a potential barrier to senior entrepreneurship. It is also important to ensure that start-up financing schemes do not discriminate against older entrepreneurs (OECD and EU Commission, 2012).

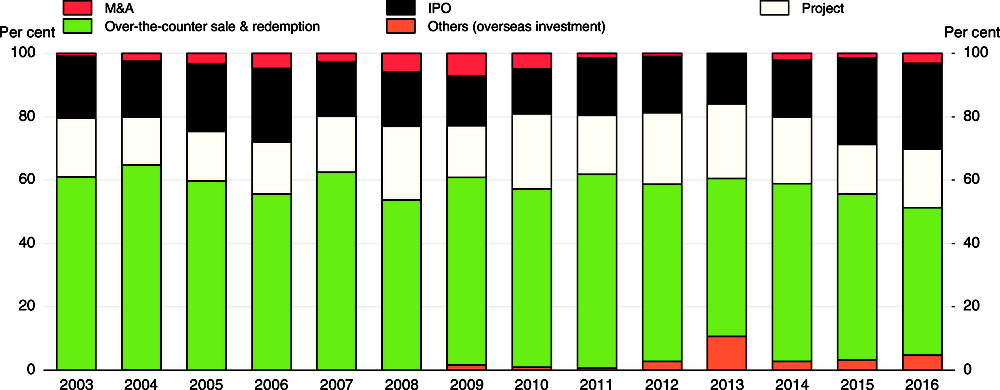

Policies to improve financing of SMEs and start-ups

Small firms’ access to credit is limited by their absence of collateral, short credit history and lack of expertise needed to produce financial statements. From the supply side, the small scale of lending involved may not compensate the cost of screening and monitoring, resulting in an information asymmetry. As a result, financial institutions attribute a high risk of default to borrowers, providing some justification for government intervention to overcome this market failure (Jones and Kim, 2014). Korea has responded with large-scale support for SMEs. First, public credit guarantees for SME lending amounted to 3.8% of GDP in 2016, down from 4.1% in 2014, but still the second highest in the OECD after Japan (Figure 2.4). Second, the government provides direct lending, amounting to KRW 4.5 trillion (0.3% of GDP in 2016). In 2016, 68% of loans requested by SMEs were authorised. Third, the government provides a range of subsidy programmes as discussed above. The size and number of public SME financing programmes is high by international standards (Koo et al., 2015).

With such government support, the financing situation for SMEs appears relatively strong. SMEs accounted for 79% of total business loans in 2016, a high share by international standards (OECD, 2018). The gap between the average interest rate on loans to SMEs and large firms fell from 79 basis points in 2008 to 23 in 2016 (Figure 2.23). The financing gap – the shortage in funding to SMEs due to market failure – was estimated at KRW 28 trillion for firms less than ten years old in 2015 (Lee et al., 2015). This amounts to 5% of total lending to SMEs. Another study that examined credit rationing in the SME loan market concluded that the probability of rationing was more than 80% in only 0.4% of firms over 2013-14 (Lee and Lim, 2017). These studies cast doubt on the need for extensive public financing of SMEs.

Figure 2.23. The interest rate spread between large firms and SMEs has fallen

A study of 23 OECD and EU countries found that very few have undertaken rigorous studies of the economic costs and benefits of public support for SMEs through credit guarantees (OECD, 2017d). However, in Korea, current public programmes to support SME financing actually lowered the productivity of recipient firms and increased the survival probability of incompetent ones, according to recent evaluations by public think tanks (Chang et al., 2014; Cho et al., 2016; Chang, 2016a; Chang, 2016b). As a result, they have had a negative impact on the national economy. Once loans are given to a firm, credit guarantee providers and financial institutions share a common interest in its survival, as a default would result in losses for both of them. To delay or prevent such a loss, they may continue to support the firm, a phenomenon referred to as “evergreening”, which facilitates the survival of non-viable firms. In 2016, 17% of SMEs said that they had not covered interest costs for more than six months during the preceding three years. However, many SMEs are not audited and do not have reliable financial information.

Public support through direct credit and guarantees to SMEs has other adverse effects:

It crowds out private funding and hinders the development of the market by reducing financial institutions’ incentives to develop their credit evaluation and risk management skills for SME lending (Sohn and Kim, 2013).