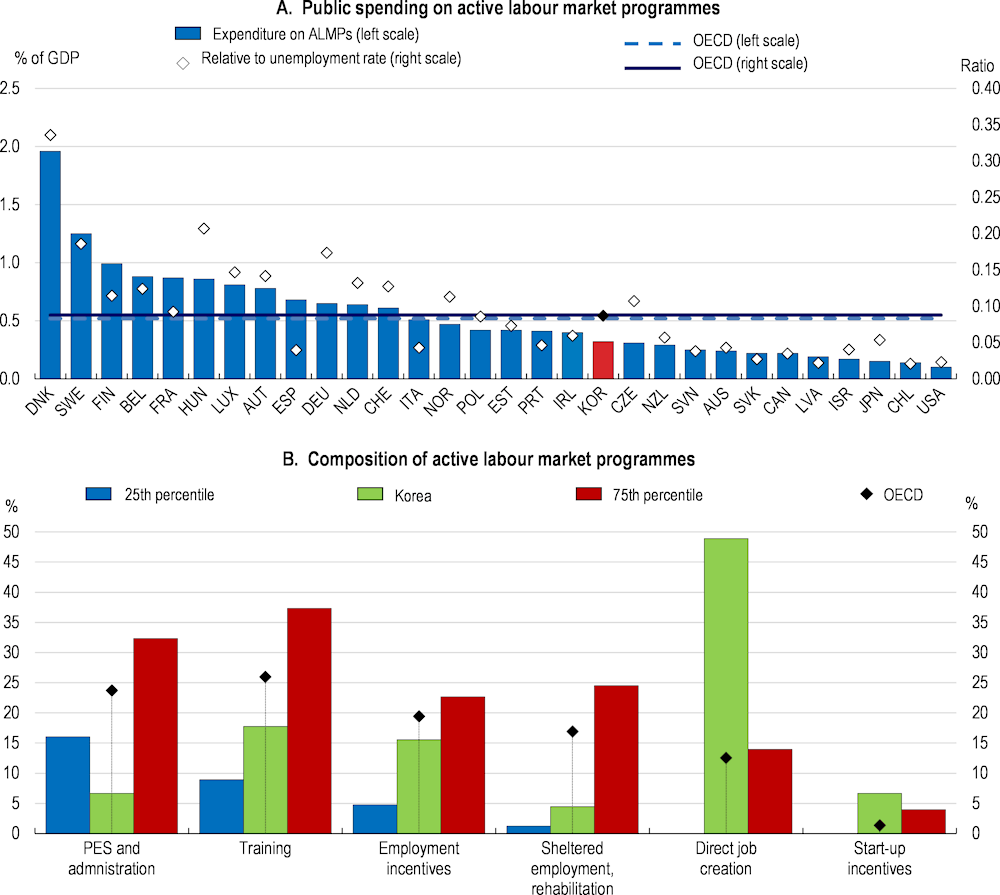

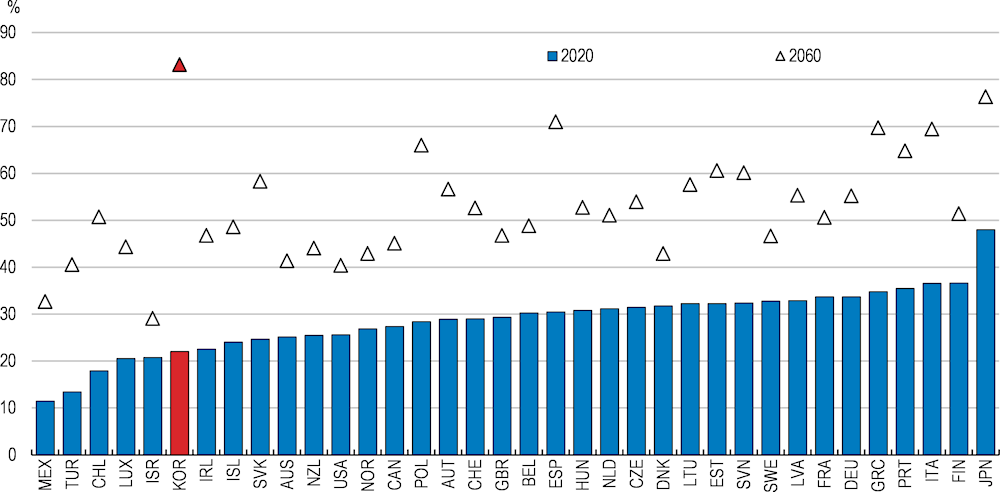

Korea has the fastest ageing population in the OECD, with the number of persons aged 65 or over projected to exceed 80% of the working-age population in 2060, the highest ratio in the OECD. In the absence of a strong policy response, this will lower economic growth, widen inequality and weaken well-being, and challenge public finance sustainability and welfare provision. The COVID-19 crisis will exacerbate these tensions, as it will persistently lower growth and employment and affect low-income workers most. Against this background, Korea needs to shelter its workforce from the crisis as much as possible, to prevent scarring and unemployment hysteresis, and better mobilise its labour resources once the recovery is underway. This chapter draws on the OECD’s new Jobs Strategy to suggest ways to raise employment and foster inclusive growth. Lifting the employment rate and quality of jobs of Korean women, who are on average highly skilled, should be a priority. Koreans effectively retire at an advanced age, but often end their working lives in poor-quality non-regular jobs, after being forced to retire from their career job in their fifties for various reasons. Maintaining high activity rates, while enhancing the quality of jobs for older workers will be crucial to sustain the economy’s growth potential and, along with welfare reforms, alleviate old-age poverty. To achieve these goals and to lift labour productivity, which remains low by OECD standards, Korea will need to reduce labour market duality and improve job matching. This requires a shift in policies. The COVID-19 crisis has triggered actions to protect the most vulnerable workers. The reinforcement of the social safety net could facilitate a more permanent shift from protecting jobs to protecting workers, which along with enhanced active labour market policies, would support employment and productivity growth.

OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2020

2. Raising employment and enhancing job quality in the face of rapid ageing

Abstract

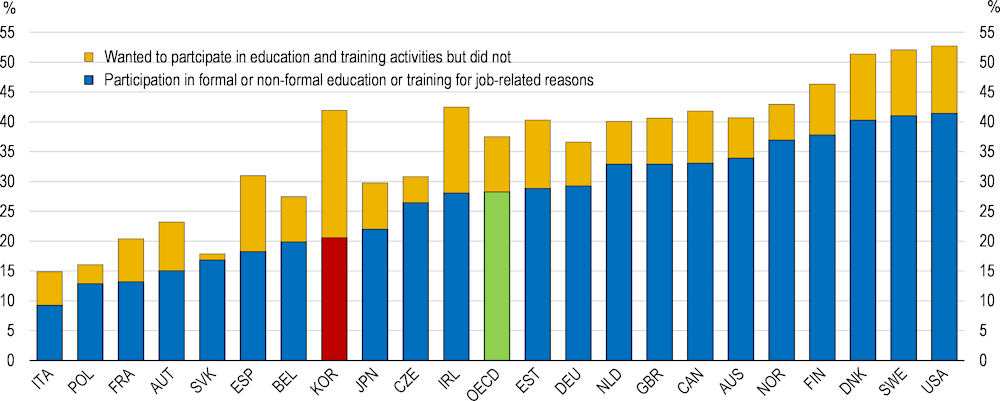

The COVID-19 crisis is lowering employment, especially for non-regular workers (Figure 2.1), and is set to have a lasting effect on the economy, as well as on public finances, despite ambitious government measures to support employment (Box 2.1). This will compound Korea’s ageing challenge, which is more acute than in any other OECD country, with the old age dependency ratio set to increase from about 20% currently to more than 80% in 2060 (Figure 2.2), clouding economic growth prospects and generating risks of widening inequality and weakening well-being, as well as challenges for public finances and the welfare system. Nevertheless, well-designed policies can address the ageing challenge and the “silver economy” also offers opportunities. No negative association between population ageing and GDP per capita growth appears across large samples of OECD and non-OECD countries, as ageing countries tend to adopt labour-saving technologies (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2017). Korea’s strength in technology and the innovation capability demonstrated during the COVID-19 crisis could help Korea face the demographic headwinds. At the microeconomic level, ageing provides opportunities for businesses producing goods and services demanded by older people. As ageing is a global phenomenon, building a comparative advantage in the silver economy could enhance export performance. Last but not least, higher and better employment for older workers would raise their purchasing power and allow them to consume more, generating a virtuous cycle.

Figure 2.1. Employment falls sharply in services and among non-regular workers

Year-on-year percentage change (unless otherwise specified), June 2020

* Percentage points.

Note: The self-employed are divided between employers and own-account workers.

Source: Statistics Korea.

Box 2.1. Main government measures to support employment and incomes during the COVID-19 crisis

Many measures implemented by the government to support the economy during the COVID-19 crisis (see Chapter 1) support employment, directly or indirectly. This box focusses on direct measures to preserve or create jobs and on income support.

Subsidy for introducing flexible work arrangements. From February 25, application procedures are temporarily simplified. SMEs who introduce commuting with time difference, work from home, remote work or selective work hours can receive up to KRW 5.2 million a year per employee.

Measures to support employment security (presented on 28 February 2020). Easing of eligibility conditions for the Employment retention subsidy and increase of its level from half to two thirds of the wage paid for large companies and from two thirds to three quarters for SMEs, for six months (February to July). On 25 March, the subsidy was increased further for three months (April to June), to up to 90% of the wage paid for SMEs in all industries. The estimated cost is KRW 0.8 trillion. Additional employment support is available for the regions and economic sectors (e.g. tourism and accommodation) most affected by the virus outbreak.

Support for job retention (presented on 22 April 2020). The government announced its Employment and Business Stability Measures to keep workers employed and to stabilise their livelihood. The government put together support measures totalling up to KRW 10.1 trillion, which can support 2.86 million persons. In addition, a KRW 40 trillion stabilisation fund for mainstay industries was unveiled, which provides funding to employers under the condition that they keep their employees.

Income support. From May 2020, relief checks of up to KRW 1 million (USD 820) are being sent to all households, for a total amount of KRW 14.3 trillion (about 0.7% of GDP). Cash payments are first directed to some 2.8 million households in the lowest income bracket (13% of the total) and others will receive coupons to spend within three months. The coupons will have to be spent by 31 August or will be considered a donation to the state. People can decide whether to apply for relief handouts for their own use it or to donate them to help the nation overcome the employment crisis caused by COVID-19. The relief handouts that the people voluntarily donate will be used to fund government projects that help maintain and create jobs for the vulnerable population. On 7 May, the government announced emergency unemployment support of a total of KRW 1.5 trillion for temporary workers, including platform and freelance workers. The first 2020 supplementary budget, passed on 17 March, included emergency support for distressed households. Some regional authorities have provided additional support (OECD, 2020a).

Public sector and subsidised job creation (presented on 22 April and 14 May 2020). 1.54 million public sector jobs will be created. Administrative procedures will be eased to speed up the creation of the 945 000 jobs already planned for 2020. Among them, more than 600 000 jobs will be positions for the elderly and the socially disadvantaged. More than 550 000 additional jobs for young adults and low-income earners will be created, including remote, tech and SME jobs, as well as 48 000 permanent jobs in the public sector. The programme will require KRW 3.6 trillion, which will mainly be financed through the third 2020 supplementary budget (35.1 trillion, 1.8% of GDP).

Source: Ministry of Economy and Finance, Ministry of Employment and Labour and OECD (2020b).

Figure 2.2. The old-age dependency ratio is set to be the highest in the OECD in 2060

Note: Ratio of population aged 65 and over to population aged 15-64. Projections are based on the medium fertility variant.

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019), World Population Prospects 2019.

Fostering solid inclusive growth in the face of the demographic headwinds calls for both better mobilising Korea’s high-quality labour resources and increasing labour productivity. Long-term scenarios suggest that this could boost average annual GDP per capita growth in 2020-60 by 1 to 2 percentage points. This chapter focusses on mobilising labour resources, drawing on the OECD’s new Jobs Strategy (Box 2.2). Productivity is addressed in Chapter 3.

Box 2.2. The OECD’s new Jobs Strategy

The digital revolution, globalisation and demographic change are transforming labour markets. These deep and rapid transformations raise new challenges for policy makers. The new OECD Jobs Strategy, endorsed by OECD Ministers at their annual meeting in May and launched in December 2018, provides a coherent framework of detailed recommendations in a wide range of policy areas to help countries address these challenges. The new Jobs Strategy goes beyond job quantity and considers job quality and inclusiveness as central policy priorities, while stressing the importance of resilience and adaptability for good economic and labour market performance in a changing world of work. The key message is that flexibility-enhancing policies in product and labour markets are necessary but not sufficient. Policies and institutions that protect workers, foster inclusiveness and allow workers and firms to make the most of ongoing changes are needed to promote good and sustainable outcomes. The OECD Jobs Strategy makes use of a data dashboard to assess the strengths and weaknesses of labour markets.

The OECD actively supports countries with the implementation of the OECD Jobs Strategy through the identification of country-specific policy priorities and recommendations. This is done through special chapters in the OECD Economic Surveys, as well as analytical background papers. The analysis in this chapter is supported by analytical background papers that focus on two key policy priorities for Korea, namely promoting labour market inclusiveness by providing better employment opportunities for disadvantaged groups (Fernandez et al., 2020), and promoting job quality by reducing the incidence of very long working hours (Hijzen and Thewissen, 2020). The process will be concluded with a synthesis report that will draw lessons from the country reviews and highlight good practices across the full range of policy tools identified by the OECD Jobs Strategy. More information on the implementation of the OECD Jobs Strategy can be found here: http://www.oecd.org/employment/jobs-strategy.

Source: OECD (2018a), Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy.

Korea’s employment rate is below the OECD average, largely due to low female employment. The gender employment gap for people aged 15-64 is nearly 18 percentage points, the fourth largest in the OECD, as relatively low wages and career prospects often discourage women from working. More than 40% of female wage earners are in non-regular employment, which prevents them from making the most of their generally high level of qualification. A number of policies can promote better employment and career progression opportunities for women, including enhancing childcare quality, supporting better work-life balance, facilitating return to work after career breaks, tackling discrimination and more generally promoting a culture of gender equality. These policies could also have a positive impact on the fertility rate, which has fallen to around one, the lowest level in the OECD. Traditional pro-natalist policies largely based on financial support for families in Korea and other East Asian countries have so far had limited impact, due to cultural obstacles, such as long working hours, family organisation and the role of mothers in children’s education (Jones, 2019). Hence, since 2018 the Korean government has prioritised quality of life, gender equality and work-life balance (OECD, 2019a).

Even though older Koreans have a relatively high employment rate, especially because of the absence or low level of pensions, they tend to hold poor-quality non-regular jobs, after being forced to retire from regular jobs in their fifties for various reasons, such as poor business performance and business suspension or closure (33%), health conditions (20%), family care (14%) and mandatory retirement (7%). This generates old-age poverty, lowers well-being and productivity, and encourages working long hours (Hijzen and Thewissen, 2020). Promoting more flexibility in wages and lifelong learning can boost the level and quality of employment of older workers.

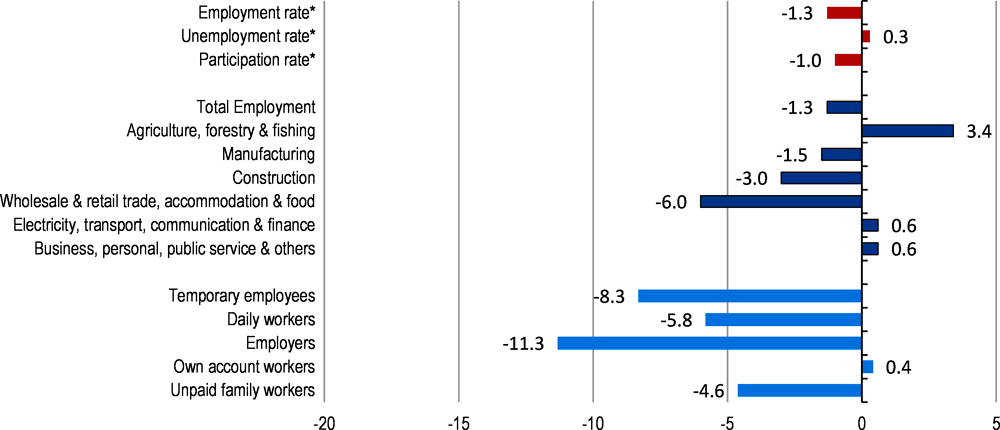

Reducing labour market rigidities and strengthening social protection is necessary to reduce labour market duality and improve job matching. A focus on protecting workers, through the expansion of the social safety net and active labour market policies, rather than protecting jobs, would contribute to raising well-being, employment and labour productivity, which is only about half of that in the top half of OECD countries. Greater use of foreign workers could alleviate labour shortages and related pressure to work long hours in small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

This chapter is structured as follows. The first part explores opportunities to raise employment, especially in groups where it remains relatively low, and outlines potential impacts on GDP growth and fiscal sustainability. The second part argues that greater labour market flexibility, combined with stronger social protection, would foster more inclusive growth.

Scarcer labour resources need to be better mobilised

Key challenges for the Korean labour market

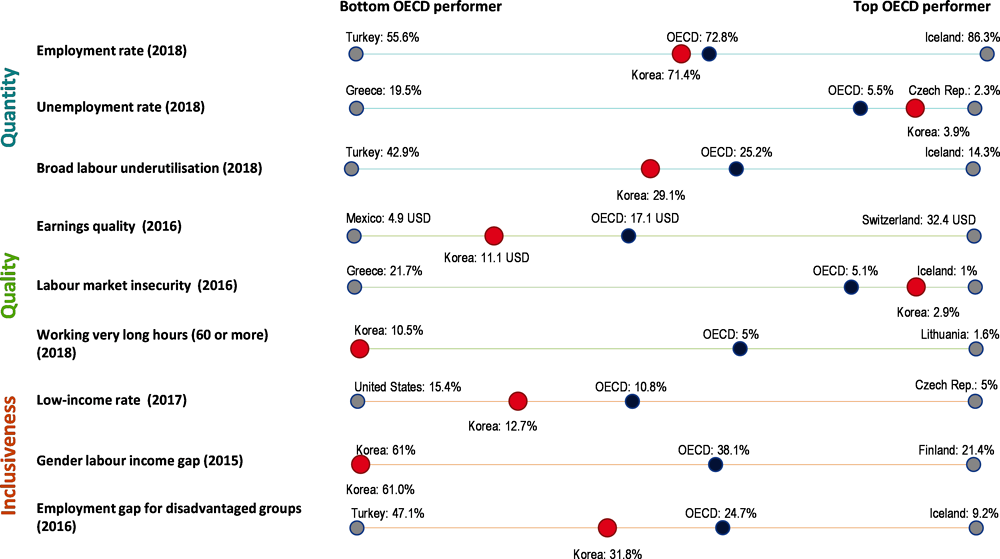

Korea faces important challenges regarding labour market inclusiveness and certain aspects of job quality, as can be seen from the OECD Jobs Strategy dashboard (Figure 2.3). The gender labour income gap is the highest in the OECD, while the incidence of low incomes among working-age persons and the employment gap among disadvantaged groups are well above the OECD average. Promoting employment among under-represented groups should be a key priority. Concerns about job quality mainly relate to a high incidence of low pay and very long working hours (60 hours or more per week). These concerns tend to be amplified by a strongly segmented labour market.

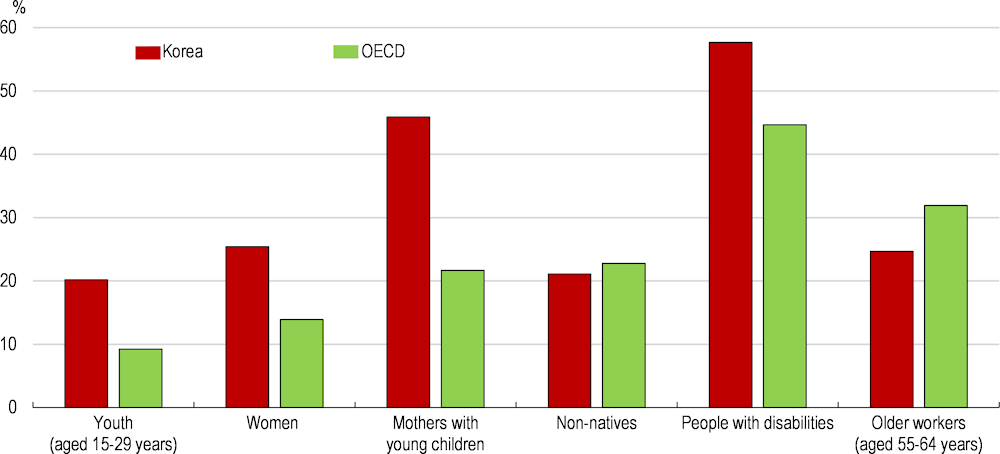

Significant employment disparities exist between socio-economic groups, underscoring the importance of tailored measures to improve outcomes. The employment gap with prime-age males for disadvantaged groups is 31.8% (Figure 2.3). Employment gaps are particularly large relative to the OECD average for youth, women with young children, as well as for people with disabilities (Figure 2.4). The COVID-19 crisis highlights the vulnerability of disadvantaged groups to economic shocks. For example, while total employment declined by 1.3% year-on-year in June 2020, the fall was 8.3% for temporary workers and 5.8% for daily workers.

Figure 2.3. Korea faces important challenges with inclusiveness and some aspects of job quality

Note: Employment rate: share of working age population (20-64) in employment (%). Broad labour underutilisation: share of inactive, unemployed or involuntary part-timers (15-64) in population (%), excluding youth (15-29) in education and not in employment. Earnings quality: gross hourly earnings in PPP-adjusted USD adjusted for inequality. Labour market insecurity: expected monetary loss associated with the risk of becoming unemployed as a share of previous earnings. Working very long hours: percentage of workers working 60 or more actual weekly hours. Low income rate: share of working-age persons living with less than 50% of median equivalised household disposable income. Gender labour income gap: difference between per capita annual earnings of men and women (% of per capita earnings of men). Employment gap for disadvantaged groups: average difference in the prime age men’s employment rate and the rates for five disadvantaged groups (mothers with children, youth who are not in full-time education or training, workers aged 55-64, non-natives, and persons with disabilities; % of the prime-age men’s rate).

Source: OECD calculations based on statistics for 2018 or the last available year and various sources; OECD (2018a), Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris.

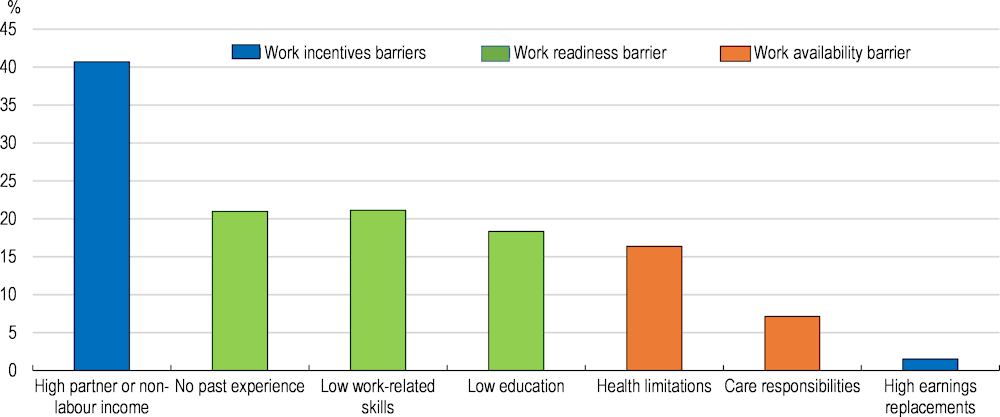

Low employment rates reflect worker-related barriers to employment. New OECD empirical evidence based on micro data for Korea identifies employment barriers faced by individuals experiencing major employment difficulties (Box 2.3). The most frequent employment disincentive is a high partner or non-labour income (Figure 2.5), which discourages employment, particularly among households’ second-earners (Fernandez et al., 2016). Furthermore, about 20-30% face work-readiness barriers related to low work-related skills, no past work experience or low education.

Figure 2.4. Disadvantaged groups face large employment gaps

Employment gap

Note: Average difference in the prime age men’s (25-54 years) employment rate and the rates for the five disadvantaged groups as a % of the prime-age men’s rate. Youth excludes those in full-time education or training. Mothers with young children concern working-age mothers with at least one child aged 0-14 years. Non-natives refers to all foreign-born people with no regards to nationality. Data refer to 2016.

Source: OECD (2018a), Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy.

Figure 2.5. There are multiple worker-related barriers to employment

Note: The population experiencing major employment difficulties is defined as those aged 18-64 that report to be long-term unemployed, inactive or to have a weak labour market attachment (an unstable job, restricted working hours or with near-zero earnings), excluding full-time students and those in compulsory military service. The figure indicates the proportion of this population that faces each identified employment barrier. The bars do not sum to 100 as individuals can face multiple employment barriers.

Source: Fernandez et al. (2020). Calculations based on KLIPS 2016.

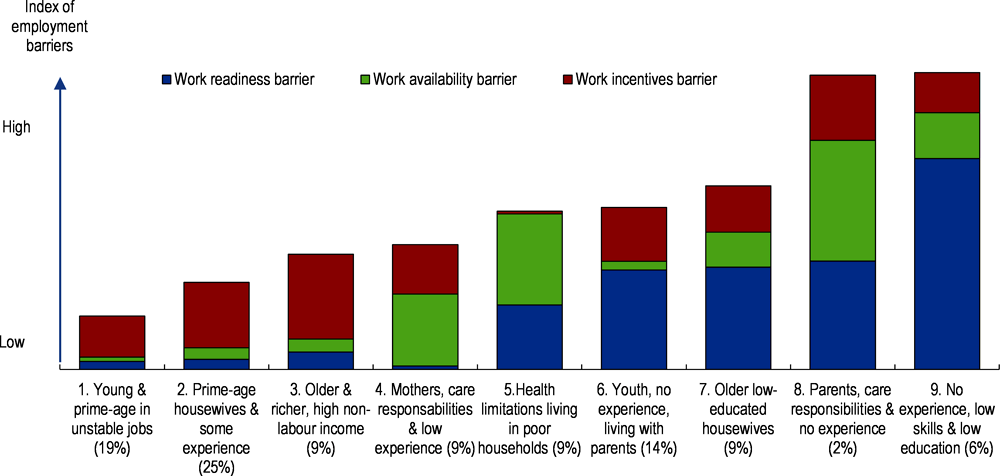

Box 2.3. Groups facing major employment barriers in Korea

This box uses the OECD’s Faces-of-Joblessness methodology to identify groups of individuals who experience major employment difficulties and face similar combinations of barriers (Fernandez et al., 2020). Major employment difficulties include long-term unemployment, inactivity or a weak labour market attachment (an unstable job, restricted working hours or near-zero earnings). Employment barriers may relate to either work readiness (low education, low work-related skills or no work experience), work availability (health limitations or care responsibilities) or work incentives (generous income-support benefits or a high partner or non-labour income). Statistical segmentation methods are used to identify groups of individuals who face a similar combination of employment barriers. The statistical portraits of the identified groups can then serve as a basis for people-centred policy interventions. In the case of Korea, a third of the working-age population experiences major employment difficulties, slightly above the OECD average of 30%. This group can be divided into nine sub-groups who face broadly similar employment barriers (Figure 2.6):

Groups primarily facing work incentives barriers. Three groups principally face work incentives barriers because of access to high partner or non-labour income sources independent of own work effort. One group is young or in prime-age, in an unstable job and generally living with their parents (Group 1). The second group consists of prime-age women performing domestic tasks (Group 2). The third group comprises older and richer individuals who have built up a long previous employment record (Group 3).

Figure 2.6. Groups facing different combinations of employment barriers

Share facing employment barriers related to work readiness, work availability and work incentives

Note: The bars refer to the extent the groups face a barrier related to work availability (health limitations and care responsibilities), work readiness (low education, low work-related skills and no past experience) and work incentives (high non-labour income and high earnings replacements), calculated as an average across individual barriers and expressed in relative terms (whether a group faces a barrier less or more compared to other groups). The number in brackets behind each group name indicates the group size as a percentage of the total population experiencing major employment difficulties.

Source: Fernandez et al. (2020). Calculations based on KLIPS 2016.

Groups primarily facing work availability barriers. Three groups predominantly face work availability barriers. For two groups, these barriers relate to care responsibilities, with one group consisting of mothers with low previous work experience (Group 4) and the other parents without past work experience (Group 8). Another group consists of individuals facing health limitations and living in poor households (Group 5).

Groups primarily facing work readiness barriers. Three groups primarily face work readiness problems. Two groups have never worked before, and consist of inactive youth (Group 6) and individuals with low skills and low education (Group 9). The third group comprises older low-educated women performing domestic tasks (Group 7).

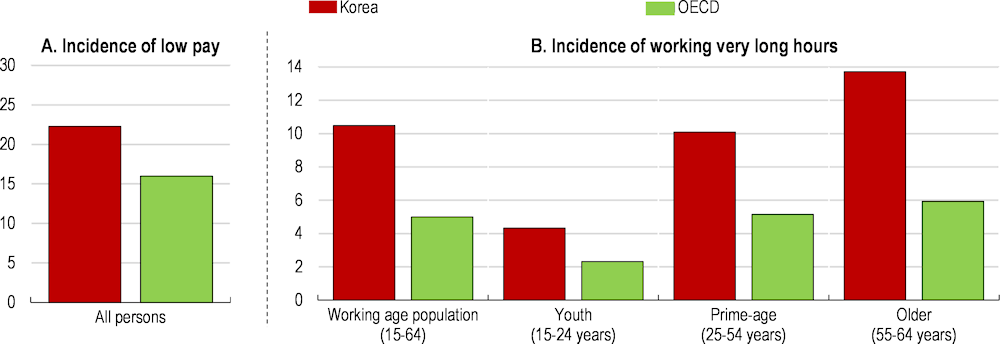

Job quality is a concern, in particular for older workers. Many workers earn low hourly wages and work very long hours. They are particularly vulnerable to economic shocks like the COVID-19 crisis. In addition to the impact from the economic slump, older workers are more vulnerable to the disease than younger people. Hence, the government has taken measures to create jobs for the elderly in outdoor or remote positions (Box 2.1). Even outside crisis times, low-pay incidence, defined as the share of full-time workers earning less than two-thirds of gross median earnings, is above the OECD average (Figure 2.7, Panel A). Working very long hours (60 or more per week) is more common in Korea than on average across the OECD for all age groups, and is particularly elevated for older workers (Panel B). This reflects both supply factors related to low wages and concerns about future pensions as well as demand factors related to skills shortages and a limited flexibility of employers to adjust employment and wages in line with business conditions and productivity. The current government is seeking to reduce the high incidence of very long working hours in an effort to improve job quality, health and productivity. Maximum total working hours have been reduced from 68 to 52 hours per week in firms with 300 or more employees as of July 2018 and in firms with 50 to 299 employees as of January 2020 and will be extended to firms with five to 49 employees in July 2021. To increase flexibility, a tripartite agreement was signed on a plan to extend the reference period over which normal working hours can be averaged from three to six months and a reform bill reflecting the agreement is currently pending at the National Assembly. The first phase of the reform targeted at firms with 300 or more employees has contributed to reducing the percentage of individuals working very long hours. Nevertheless, successfully changing Korea’s long working-hour culture requires additional efforts to improve the effectiveness of working time regulation and lower incentives to supply and demand long hours (see Key Policy Insights and Hijzen and Thewissen, 2020).

Figure 2.7. Many workers earn low wages and work very long hours

Note: Incidence of low pay: percentage of full-time workers earning less than two-thirds of gross median earnings of all full-time workers. Data refer to latest year available (2014-2018; 2017 for Korea). Average for 33 OECD countries (except NOR, SWE and TUR). Incidence of working very long hours: percentage of workers working 60 or more actual weekly hours. Data refer to 2018. Average for 31 OECD countries (excludes Chile, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand and Turkey). Data for USA refer to dependent employment.

Source: OECD Earnings Database, OECD Employment database and EU-LFS.

Promoting female employment is crucial

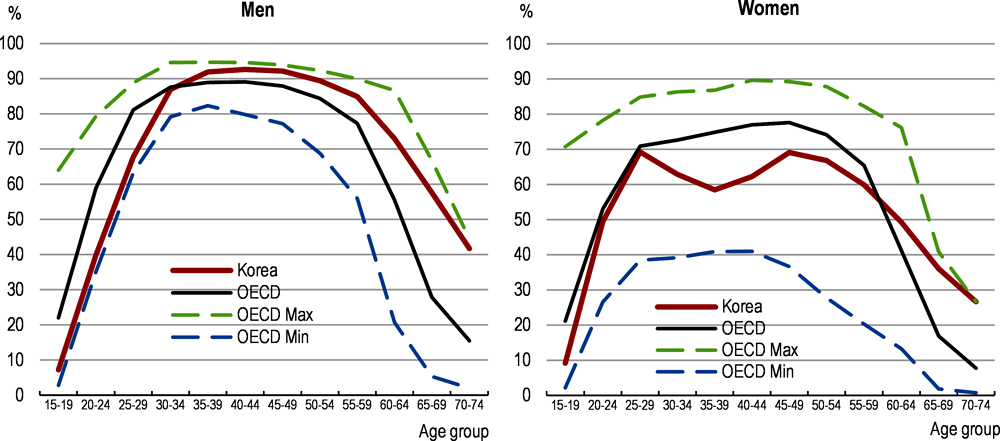

Women’s employment rate is relatively low past age 30 (Figure 2.8). The COVID-19 crisis may worsen this situation if it leads to a durable decline in job opportunities. Women are over-represented in activities like retail trade, accommodation and restaurants, which are the most affected by the crisis and are likely to recover only slowly. They are also more often than men in insecure jobs. However, there is ample scope to raise female employment, especially as women have increasingly high qualifications, with the highest 25-34 year-olds tertiary graduation rate in the OECD.

Figure 2.8. Women’s employment rate is relatively low between ages 30 and 60

Source: OECD (2019), Employment rate (indicator). doi: 10.1787/1de68a9b-en (Accessed on 11 December 2019).

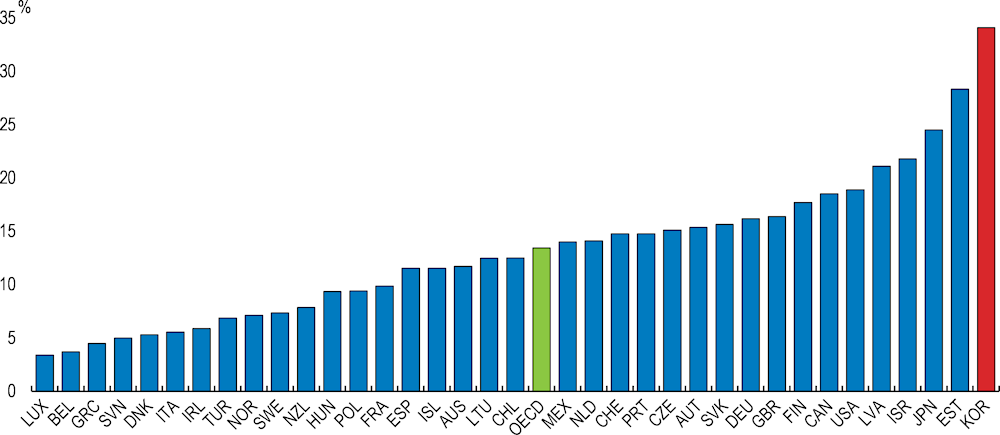

Many women exit the labour market when they have children. On average, women who did so after the birth of their first child stopped working for three years over the period 2006-15, down from almost six years over the period 1996-2005 (OECD, 2020c), partly reflecting the declining number of children per women. To facilitate mothers’ return to work, the government is providing vocational education and training for women who have taken career breaks through Job Centres for women. Nevertheless, in a system with responsibilities and pay disproportionately based on seniority, long career breaks hamper career prospects. Women returning from career breaks for childbirth or childcare often re-enter the labour market as non-regular workers with low-paying jobs, which is a key factor behind the gender wage gap, which is the largest in the OECD, at 34.1% in 2018, as against an OECD average of 13.4% (Figure 2.9). Many mothers with job qualifications are discouraged from returning to work after childbearing by unrewarding job opportunities. Indeed, Korea is one of the few OECD countries for which data are available where the difference in the employment rate between genders increases with the level of education (OECD, 2018b).

Figure 2.9. The gender wage gap is the widest in the OECD

Source: OECD (2019), Gender wage gap (indicator). doi: 10.1787/7cee77aa-en (Accessed on 11 December 2019).

Greater transparency about factors determining pay would help reduce gender pay gaps. Korea has an affirmative action programme, which was gradually expanded since its introduction in 2006, and seems to have helped narrowing gender wage gaps. In February 2020, the government launched a salary comparison website for workers in domestic firms, showing salary brackets of private sector employees according to six criteria -- firm size, type of business, occupation, job career, gender and academic background. It could build on these data to provide further analysis of wage differences. For example, the Swedish National Mediation Office issues an annual report analysing the sources of wage discrepancies, which allows separating differences related to age, education, occupation, sector of employment and hours worked from gender discrimination, thereby facilitating corrective action (Swedish National Mediation Office, 2019). Increasing support for potential female entrepreneurs to balance work and family life and obtain financing would help reduce the gender gap in entrepreneurship rates, which was the third highest in the OECD in 2017 at about 12.5 percentage points, compared to an OECD average of around seven (2018 OECD Economic Survey of Korea). Policies need to make it easier for mothers to combine careers and family life, in particular through promoting the use of paid parental leave by both parents, boosting the supply of high-quality childcare, improving work-life balance, facilitating mothers’ return to work and tackling gender discrimination.

Korean women are entitled to 90 days of paid maternity leave (of which the first 60 are mandatory under the Labour Standards Act and the remaining 30 are covered by the Employment Insurance). However, only 76.5% of female private-sector workers took maternity leave in 2018, notably because many firms are reluctant or unable to fill temporary vacancies. Many women tend to leave the labour market shortly before or after childbirth. Among the reasons cited for career interruptions, “pregnancy and childbirth” accounts for 22.6%. Beyond female labour market participation and career prospects, insufficient access to maternity leave may affect fertility, with a three percentage-point higher probability of having children for women benefitting from maternity leave (Kim, 2018a). The government has recently strengthened its supervision of businesses to ensure enforcement of maternity leave rights, using health and employment insurance data. In addition, many working mothers who are not covered by the Employment Insurance (EI) scheme are now entitled to a flat-rate maternity cash benefit of KRW 500 000 per month for three months. This covers the self-employed, freelancers, and many employees who are not covered by the EI scheme and/or do not meet the maternity benefit eligibility criteria.

Each parent is entitled to a year of paid parental leave, to be taken before the child turns eight, with a replacement rate of 80%, up to a ceiling of KRW 1.5 million (about 40% of average earnings) for the first three months, and 50% subsequently, up to a ceiling of KRW 1.2 million. The effective average replacement rate across the entire one-year leave for a worker on average earnings was 31% in 2019, which is relatively low, compared to Germany, Japan and Sweden, where the replacement rate is around 60% (OECD, 2019a). Parental leave is estimated to increase the probability of a woman’s continued participation in the labour market by four percentage points (Kim, 2018a). The second parent taking leave (usually the father) can benefit from three months leave at a payment rate of 100%, up to a ceiling of KRW 2.5 million (about 60% of average earnings). However, fathers whose spouses are unable to take parental leave do not benefit from the higher replacement rate. Amending this rule should be considered. In 2018, about 30 parents per 100 live births (of which 18% were fathers) claimed the parental leave benefit. This compares to more than 70% in Nordic countries and about 90% in Slovenia. A 2018 relaxation of eligibility criteria and the 2019 EI extension are likely to lead to an increase in take-up in the future (OECD, 2020c).

The proportion of fathers among parental leave-takers (regardless of duration) increased from 2.4% in 2011 to more than 21.2% in 2019. Nevertheless, negative perceptions in the workplace and income reduction remain strong obstacles to fathers taking parental leave, particularly in the private sector. Many firms are reluctant to allow parental leave, especially because of difficulties in hiring replacement workers and adapting their organisation. Firms are more willing to grant parental leaves in many other OECD countries. The Korean law provides for the right to maternity leave and the prohibition of discrimination, and the Korean government grants subsidies to firms offering parental leave and reduced working hours for parents, as well as additional subsidies for hiring replacement workers, but awareness remains insufficient.

As the maximum parental leave is fairly long and the effective replacement rate fairly low, allowing higher replacement rates for shorter leaves, as in Germany, may be a way to alleviate the income reduction problem (OECD, 2019a). Encouraging fathers to take parental leave leads to better sharing of household work, even beyond the leave period, supporting female employment. One recent estimate suggests that a 50% increase in her husband’s household work increases a woman’s probability to continue working by 3.5 percentage points (Kim, 2018a). Improving flexibility in workplace practices, in particular through expanding opportunities to work part-time with remuneration proportional to that of regular full-time workers and allowing greater working-time flexibility would also encourage female employment (OECD, 2019a). This could also help encourage births, as voluntary part-time is associated with a fertility rate that is two percentage points higher relative to full-time work (Kim, 2018a).

The availability of high-quality childcare is essential to support female employment and to limit career breaks. Government support for children aged 0-5 includes vouchers for children enrolled in childcare centres and a home childcare allowance for children not enrolled in the centres. The share of out-of-pocket payments for childcare is among the lowest in the OECD (OECD, 2020c). Participation is high, at over 50% for children aged below three and 93% for those between three and five in 2016, compared to OECD averages of 33% and 86% respectively (OECD, 2019a). The government aims to increase childcare capacity further to allow all children to receive basic childcare during the day and extended childcare at night from March 2020.

Enhancing childcare quality further is a priority. The Nuri curriculum was introduced in 2013 to raise childcare quality and average user satisfaction with childcare centres has increased from 3.7 to 4 on a scale of 5 from 2012 to 2018. Nevertheless, further improvement is needed to ensure high quality across all childcare centres. Hence, the government replaced accreditation upon application by mandatory assessment for all childcare centres in June 2019, increased the number of assistant teachers by about 15 000 in 2019 and is raising early childhood education and care teachers’ pay and strengthening their training. Reflecting many parents’ preference for public childcare, the government aims to lift its share to 40% by 2021, from around a quarter currently.

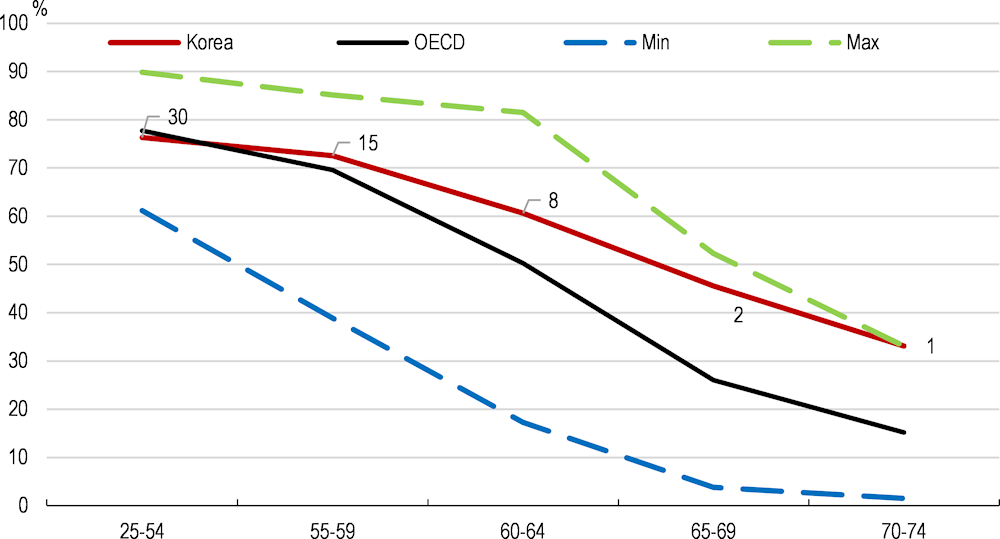

Older workers need better jobs

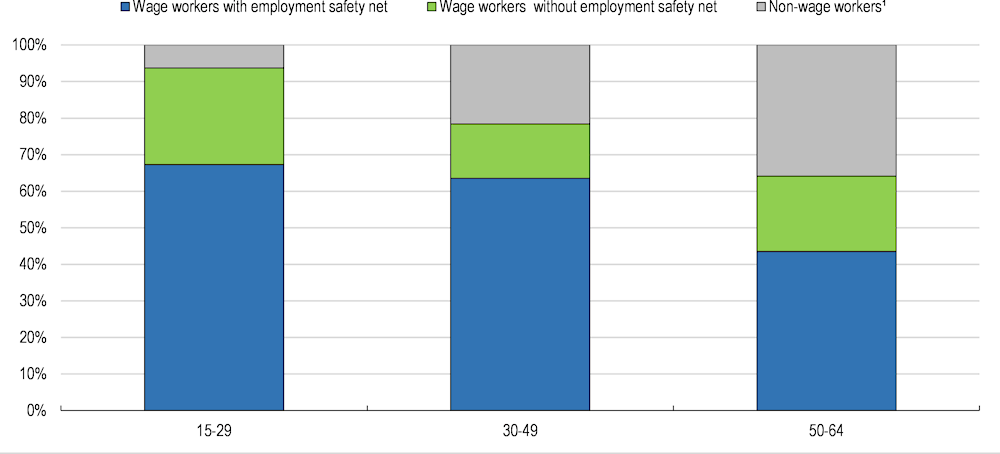

Because of low pension entitlements, partly reflecting the late introduction of the National Pension Scheme (NPS), which was set up in 1988 for companies with more than ten employees and gradually extended to become quasi-universal only in 1999, 58% of men and 35% of women aged 65 to 69 are still working and the average full retirement age is around 72. While Korea ranks 30th in the OECD on the employment rate for individuals aged 25-54, it climbs steadily in the ranking as age increases, reaching the top spot for the 70-74 year-olds (Figure 2.10). However, more than 40% of workers aged over 60 are in non-permanent jobs, compared to less than 20% in the overall working population (OECD, 2018c). A large proportion of older workers also lacks an employment safety net (Figure 2.11).

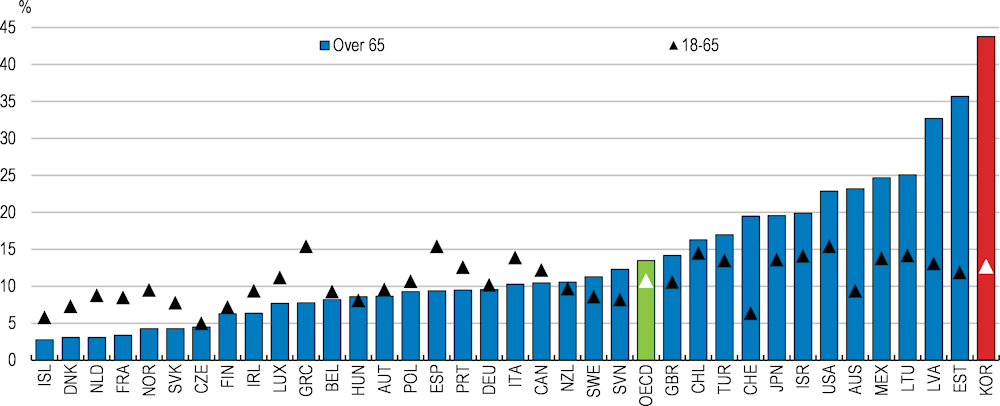

According to the 2017 Additional Economically Active Population Survey for Older Workers, 58% of workers aged 55-79 work primarily to earn or supplement their living costs. Korea has the highest share of people aged over 65 earning less than half the median household income of the total population. This contrasts with the relative poverty rate of the population aged 18-65, which is only slightly above the OECD average (Figure 2.12). A multidimensional elderly poverty index taking into account assets and housing (area per household member) suggests that old-age poverty may be overstated when only income is considered. According to this index, about a fifth of Korean seniors would suffer from deprivation (Yun and Ko, 2018). This is still a high proportion, asset holdings also mitigate income poverty in other OECD countries, and the area per household member may overestimate the benefits of housing assets for households living in large, but low quality dwellings, particularly in rural areas with limited service availability. Many public sector jobs for older workers are being created. In particular, the government will create 600 000 jobs for the elderly and the socially disadvantaged in outdoor or remote positions, to ensure safety from the COVID-19 virus, in 2020 (Box 2.1). While this alleviates old-age poverty and fills some needs for public service workers, more emphasis should be put on raising the quality of jobs, especially through reducing the weight of seniority in the wage system and reorienting active labour market policies (see below).

Figure 2.10. The employment rate falls more slowly with age than in other OECD countries

Note: Data labels indicate Korea's employment rate rank in the OECD.

Source: OECD (2018c), Working Better with Age: Korea, Ageing and Employment Policies.

Figure 2.11. Many older workers are excluded from the social safety net

1. Non-wage workers include employers, self-employed and unpaid family workers.

Source: OECD (2018c), Working Better with Age: Korea, Ageing and Employment Policies.

Figure 2.12. The share of the elderly in relative poverty is the highest in the OECD

Poverty rates

Note: Number of persons living with less than half of the median household income of the total population.

Source: OECD (2019), Poverty rate (indicator). doi: 10.1787/0fe1315d-en (Accessed on 11 December 2019).

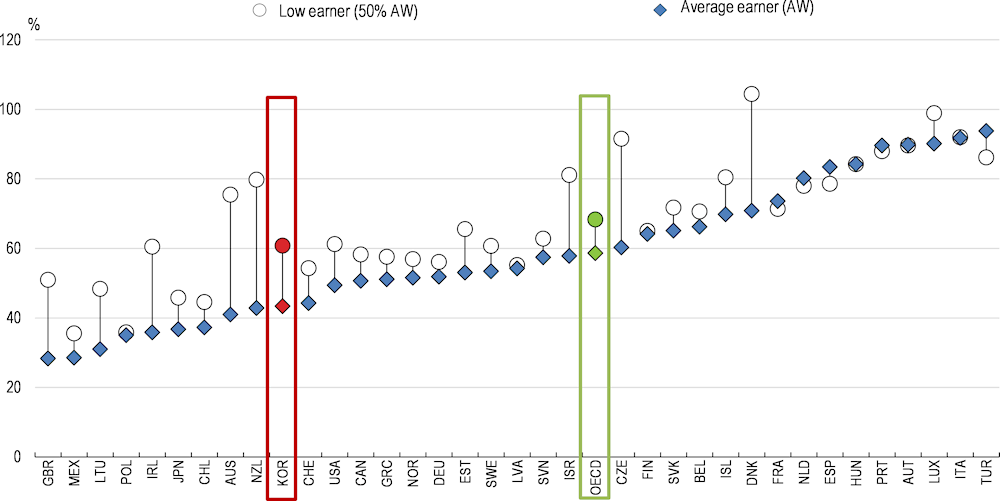

As the NPS matures, pension adequacy will improve. Even so, the net mandatory public and private replacement rate (taking personal income taxes and social security contributions paid by workers and pensioners into account) for an average income earner after 40 years of contribution is fairly low, at 43%, compared to an OECD average of 59%. Low-income earners (at 50% of average earnings) currently benefit from a net replacement rate of 61%, still lower than the OECD average of 68% (Figure 2.13). Furthermore, as a result of reforms to enhance the financial sustainability, the targeted gross replacement rate will decrease by 0.5 percentage point per year from 45% in 2018 to 40% in 2028 (OECD, 2019b).

Expanding the coverage of the NPS to non-regular workers is another challenge. Excluding those who are not considered workplace-based insured, such as short-time workers, who work less than 60 hours a month, and day workers who work less than eight days a month, coverage was only slightly above 36% for non-regular workers in 2016, compared with nearly 83% for regular workers. The Duru Nuri social insurance support programme, initiated in 2012, grants subsidies covering employer and employee NPS and EI premiums of low-income workers in companies with fewer than ten employees. The subsidy currently amounts to 40% of contributions for previously covered employees, and up to 90% for new subscribers. In order to reduce the deadweight costs, and increase the effect of social insurance, it is necessary to reduce the support for existing insured workers and operate the programme mainly for new subscribers. More efficient collection of social contributions, notably taking advantage of connecting various administrative records, would also help raise NPS coverage (Kim, 2016).

Figure 2.13. Net pension replacement rates are relatively low

Note: The net replacement rate is calculated assuming labour market entry at age 22 in 2018 and retirement after a full career. The net replacement rates shown are calculated for an individual with 100% and 50% of average worker earnings (AW).

Source: OECD pension models.

Given the short periods of contribution and the low replacement rates, many pensioners rely on the means-tested, tax-financed basic pension, to which 70% of the elderly are eligible. Despite recent increases to up to KRW 300 000 (about USD 260 or less than 8% of average earnings), the basic pension remains very low. It should be increased further and focussed on the elderly in absolute poverty. The Basic Livelihood Security Programme provides means-tested, non-contributory social assistance for people living below the poverty line. However, to turn it into a better instrument against old-age poverty, the family support obligation, which takes into account earnings and assets of a claimant’s children and parents to determine entitlements (irrespective of whether they actually provide support), should be phased out, as in other OECD countries which previously had similar rules, including Austria, Belgium and France (OECD, 2018b). Under the New Deal, the Korean government plans to phase out the family support obligation from the Basic Livelihood Security Programme by 2022 and to expand the level of coverage.

Employees with at least a year of service are entitled to a severance lump-sum payment corresponding to a month of wages for each year of service. Since 2005, the government has allowed the conversion of severance pay into a traditional employee retirement scheme, subject to employee consent (Kim, 2018b). However, employees generally prefer the severance lump-sum, which they can use, for example, to set up a business after mandatory retirement or to finance their children’s education. The lack of portability of benefits is a hindrance to conversion into traditional pensions and hampers labour mobility, two issues which have been addressed in the reform of the Austrian severance pay system (Box 2.4).

Box 2.4. Austria: from severance pay to individual savings accounts

Until 2003, Austria had a standard severance pay system under which employees became eligible to a cash payment from their employer in case of dismissal after three or more years of tenure. However, concerns were raised about its ability to provide effective income protection to all workers in the case of job loss, since workers with shorter tenures account for the bulk of dismissals but are not entitled to severance pay. Concerns were also raised about its ability to support robust productivity growth based on the reallocation of workers from less to more productive firms. In particular, the fact that voluntary moves would entail the loss of the severance pay entitlements was thought to discourage mobility towards better paying firms.

To address these concerns, Austria adopted a major reform in 2003, which involved replacing its existing system of severance pay by a system of individual savings accounts, funded through mandatory monthly contributions by employers, which could be used by workers to withdraw severance pay in the case of dismissal. Since contributions are not contingent on dismissal and the funds are linked to the worker rather than their job, the new system no longer reduces hiring and firing by firms or mobility between jobs. Upon retirement, employees can claim the remaining balance in their savings accounts as a one-off cash payment or have it converted into a pension. The latter aspect of the reform was meant to support the growth of the private pillar of the pension system and help prepare it for the challenges arising from population ageing.

A major benefit of the reform has been the increase in coverage by severance pay entitlements in the case of job loss, with all workers on a permanent contract now eligible. A lesson from the Austrian experience is that the implications of the new system for the pension system largely depend on the rules for making withdrawals (e.g. limits) and investing the savings held in the accounts (e.g. capital requirements) (Hofer et al., 2011). There is only limited evidence on the impact of the reform on hiring and firing or on the mobility of workers: while the effects have likely been positive, they do not appear to have been very large (Hofer et al., 2011; Kettemann et al., 2017).

Maintaining very high employment rates of older workers as the pension system matures, which is necessary to support growth and ensure fiscal sustainability, will require improving job quality. The spectacular progress in workforce skills will help, as workers with higher qualifications can better adapt to evolving labour market needs and tend to benefit from better working conditions. Korea has experienced the fastest increase in educational attainment in the OECD over the past decades, with a rise in the share of tertiary graduates from around 20% in the 55-64 age group to around 70% for the 25-34 year-olds. The OECD Survey of adult skills (PIAAC) also reveals much stronger skills in younger generations than in older ones (OECD, 2013a).

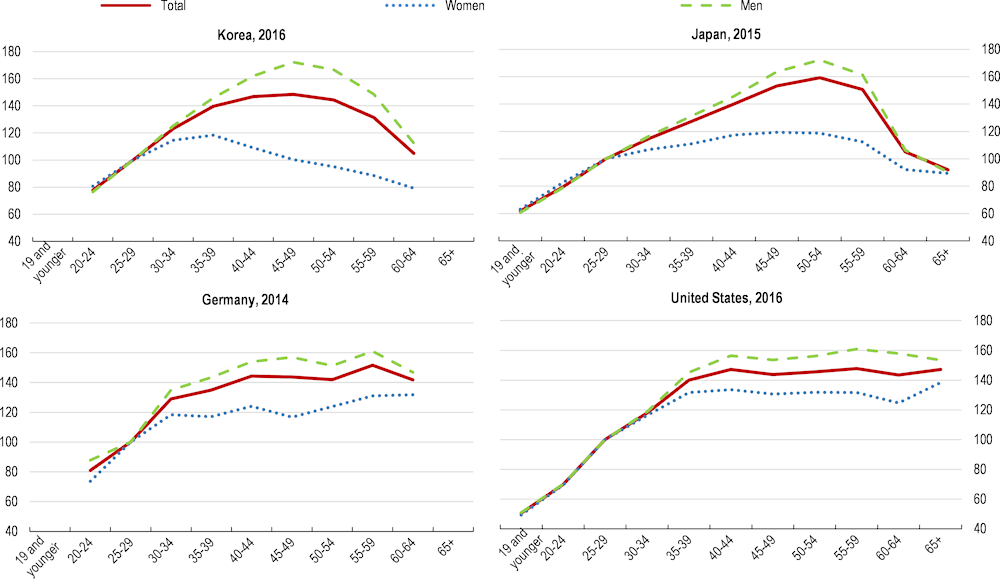

Nevertheless, policies will also need to support older workers’ employment. Even though pension adequacy will improve as the pension system matures, incentives to work until an advanced age will remain fairly strong (see below). Conversely, incentives for firms to retain older workers are still weak. Incentives for workers and employers to ensure that workers stay longer in their career jobs need to be strengthened. The minimum mandatory retirement age that firms can set was raised to 60 in 2016-17. It is necessary to analyse the employment effects of the 2016-17 extension of the minimum mandatory retirement age to 60 and find ways to encourage employers to retain workers in their main job longer. In the long term, the retirement age should be gradually pushed up further, to beyond 65 as in most OECD countries. Measures to prevent circumvention through “honorary retirement” may be necessary. An obstacle to retaining older workers is the seniority-based wage system, which opens a gap between wages and productivity at older ages. Korea, like Japan, has much steeper wage increases in relation to age beyond the mid-30s or early-40s than most other OECD, countries, for example Germany or the United States (Figure 2.14).

In recent years, over half of the companies with over 300 employees have adopted the wage peak system, which freezes or gradually reduces the wages of older workers, with partial compensation through government subsidies granted to the employee. However, the wage peak system has met opposition from some workers and trade unions, as the current wage structure provides relatively high earnings to workers at the time they have to pay for their children’s education, support their parents and make contributions for their retirement (OECD, 2018c).

Japan and Singapore have promoted employment of older workers through re-hiring policies. In Japan, employers with a mandatory retirement age below 65 were required to introduce one of the following measures from 2006: i) raise the mandatory retirement age to at least 65; ii) abolish mandatory retirement; or iii) retain or re-hire workers who wish to continue working until age 65. A large majority of companies of all sizes have chosen the third option. This policy has contributed to raise the employment rate of older workers, albeit at a cost in terms of job quality, work satisfaction and well-being. Workers reaching the mandatory retirement age are generally re-hired as non-regular workers and suffer large wage cuts, for many in the order of 40%. While wage cuts partly reflect changes in job responsibilities, many older workers find these wage cuts excessive. Moreover, systematic re-hiring of older workers in lower positions may be detrimental to productivity, as some may not be able to fully use their skills in their new job or become less motivated (OECD, 2018d, Jones and Seitani, 2019). In Singapore, since 2012 employers must offer medically fit employees with satisfactory performance reaching the retirement age (currently 62) re-employment up to the Re-employment Age (currently 67), though the job and salary may change. The re-employment system has allowed older workers’ employment to rise, while preserving firms’ competitiveness. It is complemented by policies to enhance the quality of employment for older workers, including financial incentives for employers to redesign jobs and adopt age-friendly workplace practices, government support for building capability in human resource management, and public education initiatives to raise the employability and productivity of older workers (WEF, 2017). In 2019, the Tripartite Workgroup on Older Workers formed by the government, employers and trade unions recommended to gradually raise the retirement age and the re-employment age to respectively 65 and 70 by 2030, as well as additional measures towards more inclusive workplaces, including structured career planning, transformational job redesign and better opportunities for part-time re-employment (Tripartite Workgroup on Older Workers, 2019).

The ultimate objective should be a flexible wage system based on performance and job content and skills requirements (2018 OECD Economic survey of Korea). The government has limited direct influence on wage-setting arrangements negotiated at the firm level, but can cooperate with the social partners to promote mutually beneficial deals and new qualification frameworks to align wages with job requirements and skills, possibly using transitory compensation to minimise the current cohort of workers’ potential loss of lifetime earnings (OECD, 2018c). The government should push ahead in this direction, through adjusting the institutional framework and providing market wage information.

Technological progress calls for re-skilling and up-skilling. The COVID-19 crisis will speed up the move towards digital technologies and labour reallocation across sectors, which intensifies the need to upgrade skills. Workers need to participate in lifelong learning to retain or enhance their employability. Participation of workers aged 55-64 in training is below the OECD average and the unmet training needs are the largest among the countries for which data are available. More than a fifth of workers aged 55-64 were willing to participate in training, but did not (Figure 2.15). Being too busy at work was cited as the main reason by almost 40% (OECD, 2018c).

Figure 2.14. Wages reflect seniority more than in most other OECD countries

Age-earnings profiles in Korea compared with selected OECD countries (latest available year), Index, 25-29 year-olds = 100

Source: OECD (2018b), Towards Better Social and Employment Security in Korea, Connecting People with Jobs.

The uptake of training needs to be increased, especially in SMEs, for example by providing, in conjunction with the Public Employment Service, programmes that would help firms find adequate replacement workers (OECD, 2020c). Developing further labour market-relevant training is essential. The government is providing tailored training programmes to help older workers adapt to new technologies and enhancing education programmes on core technologies and skills in Polytechnic Universities, as well as other universities and public institutions at the regional level. The National Learning Card introduced in January 2020 by integrating and reorganising previously separate unemployed and incumbent individual learning cards, reduces the blind spot in vocational training for older workers and other disadvantaged groups, and allows individuals to design their own learning plan on a long-term basis. It will be important, however, that adequate career guidance is provided to individuals so that they can take informed training decisions.

Figure 2.15. Many older Korean workers would like to get education and training

Population aged 55-64 participating in education and training or expressing an interest in training but not actually participating, 2012

Formal recognition and validation of competences acquired through different channels, including non-formal education and informal learning, is crucial, especially in a society with a strong focus on academic credentials (OECD, 2020d,e). The new National Competency Standards (NCS) is an important tool in that respect, and the government is already operationalising and promoting the effective use of the NCS and introducing monitoring instruments. The government has also institutionalised the participation of industry and workers in the process of developing and improving the NCS. However, the NCS has been underutilised in promotion and wages, and more efforts and time will be needed to ensure it takes root in workplaces. This will require continuous government monitoring and management.

Healthy ageing is essential to enhance the contribution of older workers to the economy and the well-being of the elderly. The health and long-term care system will need to adapt to the evolution of needs related to ageing. Korean health care has made spectacular advances over the past decades, as illustrated by its very effective response to the COVID-19 outbreak. It provides universal coverage and contributes to Koreans having one of the highest life expectancies in the world. Long-term care insurance was introduced in 2008. However, the current hospital-based system is not well equipped to deal with chronic diseases and multiple morbidities associated with ageing (OECD, 2013b). Korea has the second longest length of stay in hospital in the OECD behind Japan (OECD, 2019c). Strengthening primary care would limit avoidable hospital admissions, reduce the length of hospital stays and ensure better monitoring of chronic conditions. The use of electronic medical records, which the government has been promoting, can help in that respect (Kwon et al., 2015). Non-face-to-face medicine also offers opportunities for monitoring chronic conditions (Oliveira Hashiguchi, 2020). Reinforcing prevention, notably measures to discourage smoking and excessive alcohol consumption, would also favour healthy ageing (OECD, 2016).

Raising employment would counteract the projected fall in trend GDP

According to OECD long-term projections, Korea’s potential GDP per capita growth will fall from an average of nearly 3% between 2005 and 2020 to an average of 1.2% from 2020 to 2060 (Guillemette et al., 2017). About half of this fall is due to the decline in the share of the working-age population, with the remainder accounted for by slower increases in the employment rate, less capital deepening and weaker productivity, despite Korea’s expected convergence towards the best-performing OECD economies. These projections pre-date the COVID-19 crisis, which may affect Korea’s growth potential, although to an extent which is too early to assess. A protracted global crisis would lower productivity through lower capital intensity due to a lack of physical investment and through lower efficiency due to a lack of intangible investments and the reorganisation of global value chains. Prolonged unemployment may also affect the productive capacity of workers, and result in labour-market participation remaining depressed for a protracted period. While in the OECD long-term projections, Korea is expected to continue catching up with higher-productivity OECD members, the shrinking share of the working age population will have a stronger negative impact on Korea than on the average OECD country. To some extent, the slowdown in GDP per capita growth is inevitable, as population ages and the income gap with the top OECD countries shrinks, reducing opportunities for rapid catch-up. However, Korea can achieve higher growth than in the baseline scenario, by raising its employment rate and productivity.

This section explores various scenarios, using the OECD long-term model (Guillemette et al., 2017; Guillemette and Turner, 2018). The baseline incorporates a reduction of the gender employment gap from about 18 percentage points currently to 6 percentage points in 2060, based on education and societal trends. Assuming unchanged male participation, fully closing the gap would raise GDP per capita by 4.5% compared to the baseline in 2060 (Table 2.1). The youth employment rate is also relatively low. Lifting it to the OECD average would add more than 3% to GDP per capita by 2060. Even though, as noted above, the baseline scenario is more uncertain than ever, deviations from the baseline are likely to show little sensitivity to changes in the baseline.

The importance of employment rates in different population groups for the aggregate employment rate and GDP growth can also be illustrated by applying employment rates from other countries to the structure of the Korean population.

With the same employment rates in each age group as Japan, Korea’s employment and GDP per capita would be about 9% higher than the baseline in 2060, as female employment in most age groups and male youth employment would be higher.

Assuming that Korea moves to the highest employment rate in the OECD in each age group for both men and women raises GDP per capita by nearly 25% by 2060. This scenario provides an upper bound to the potential impact of increasing employment rates, insofar as it is unlikely that a country could have the highest employment rates in all age groups, not least because individuals entering the labour market earlier may also retire earlier.

A second set of simulations explores the impact of increases in productivity related to a reduction in economic duality. Raising SMEs’ average productivity from its current level of about a third of that of large firms to half, which corresponds to the OECD average, would lift GDP per capita by more than 40% in 2060, amounting to an increase in the 2020-60 annual growth rate of 0.9 percentage points. Raising services productivity from about 45% of that of industry to the OECD average of 85% by 2060, would increase GDP per capita by nearly 60% in 2060, or equivalently raise the 2020-60 annual growth rate by 1.2 percentage points.

Table 2.1. Long-term scenarios: GDP growth and employment

|

|

GDP per capita |

Potential employment |

Employment rate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Deviation from baseline in 2060 |

||||||

|

|

Per cent |

Percentage points |

||||

|

Alternative employment scenarios |

|

|

||||

|

Closing gender employment gap |

4.5 |

4.7 |

3.2 |

|||

|

Raising the youth employment rate to the OECD average |

3.3 |

3.4 |

2.3 |

|||

|

Employment rates as in Japan |

9.2 |

8.8 |

6.0 |

|||

|

Employment rates at OECD maximum |

24.6 |

23.6 |

16.1 |

|||

|

Alternative productivity scenarios |

||||||

|

SME's relative productivity raises to OECD average |

41.7 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||

|

Service sector's relative productivity raises to OECD average |

59.7 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||

|

Closing the gender wage and employment gaps |

17.8 |

4.7 |

3.2 |

|||

|

Closing half of the old age wage gap |

6.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Long-term model.

If women could get better access to more productive jobs (proxied by higher wages), aggregate productivity and hence GDP per capita would increase. Under the assumption that the gender employment gap fully closes, GDP per capita is nearly 18% above the baseline in 2060.

Another way to lift output would be to boost the productivity of older workers, through enhancing lifelong learning, while discouraging early retirement from career jobs, which pushes workers toward lower-productivity jobs. Closing half of the wage gap between older workers and those aged 45-49 by 2060, assuming a corresponding increase in productivity, would raise GDP per capita by about 6% in 2060.

The alternative scenarios for employment or productivity are largely overlapping, preventing their aggregation into a single result. As noted earlier, the scenario where employment rates reach the maximum OECD level in every age category is likely to be an upper bound for employment-related increases. Similarly, the increase in service sector productivity would require higher productivity of SMEs and of most categories of workers. It likely constitutes an upper bound for productivity-related increases in GDP per capita, at 1.2 percentage points.

Combining the most optimistic scenarios for employment and productivity raises 2020-60 average annual GDP per capita growth by 1.8 percentage points. A less optimistic scenario, which would combine the employment rates of Japan with a catch-up of SMEs to OECD average productivity levels, would raise annual 2020-60 average GDP per capita growth by 1.1 percentage points.

The rising old age dependency ratio will increasingly strain public finances

The OECD long-term baseline scenario has total primary (excluding interest) government expenditure rising by over 10 percentage points of GDP by 2060 (Table 2.2). Health and pension expenditure account for more than half of the increase. The rise in pension spending essentially stems from the growing number of retirees, but is also sensitive to the pension indexation assumption. The baseline scenario assumes that pension benefits in Korea and other non-EU countries grow at an equally weighted average of price and wage inflation. This may overstate the increase for Korea, as pension uprating is currently based on price inflation. Assuming that price indexation prevails until 2060, the increase in pension spending from 2020 to 2060 would be only 0.7 instead of 2.3 percentage points of GDP in the OECD long-term model.

Table 2.2. Long-term scenarios: Government expenditure and revenue

|

|

Public health expenditure |

Public pension expenditure |

Other primary expenditure |

Total primary expenditure |

Total primary revenue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Percentage points of GDP |

||||

|

Baseline |

|

||||

|

Change 2020-60 |

3.2 |

2.2 |

4.9 |

10.4 |

8.4 |

|

Deviations from baseline in 2060 |

Percentage points of GDP |

||||

|

Alternative employment scenarios |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Closing gender employment gap |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-1.3 |

-1.6 |

-1.5 |

|

Raising the youth employment rate to the OECD average |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

-0.9 |

-1.2 |

-1.1 |

|

Employment rates as in Japan |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

-2.3 |

-2.9 |

-3.0 |

|

Employment rates at OECD maximum |

-0.5 |

-1.1 |

-5.4 |

-6.9 |

-7.0 |

|

Alternative productivity scenarios |

|||||

|

SME's relative productivity raises to OECD average |

0.6 |

-0.9 |

0.0 |

-0.3 |

0.4 |

|

Service sector's relative productivity raises to OECD average |

0.8 |

-1.1 |

0.0 |

-0.4 |

0.6 |

|

Closing the gender wage and employment gaps |

0.1 |

-0.5 |

-1.3 |

-1.7 |

-1.4 |

|

Closing half of the old age wage gap |

0.1 |

-0.2 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Long-term model.

Pressure for higher increases may, however, build up over time as indexation to prices implies, all else equal, a continuous decline in the ratio of pension income to work income, which is already very low in Korea. Public health expenditure is projected to rise by more than three percentage points of GDP between 2020 and 2060. The increase in primary expenditure other than pensions and health reflects the higher share of output needed to maintain a constant level of public service per capita when the employment-to-population shrinks (Guillemette and Turner, 2017). The increase in total primary revenue is generated endogenously to stabilise gross government debt around 45% of GDP in the long run. The fiscal response to the COVID-19 crisis will increase government debt to an extent which will depend on the depth and length of the downturn (Chapter 1). This will require either allowing government debt to stabilise at a higher level, which would be possible without jeopardising sustainability since 45% of GDP is low by international standards, or raising taxes once the economy has recovered.

Improving job matching for youth and foreigners’ workforce contribution

Less than half of youth aged 15-29 were employed before the COVID-19 crisis, the fifth lowest share in the OECD. Youth employment has fallen rapidly since February 2020, particularly in the service sector, and is expected to contract further over the coming months. The generation currently entering the labour market is likely to suffer scarring effects. A year delay in job entry is estimated to lower the average wage over ten years by up to 8%. Lower initial wages due to unfavourable economic conditions also show strong persistence (Han, 2020a). The pre-crisis low youth employment rate reflects long studies, as more than two-thirds of youth obtain tertiary degrees, but also slow transition from education to employment. Labour market duality encourages young people to extend formal or informal education in the hope of joining large firms or the public sector, rather than SMEs, which often suffer from a shortage of skilled workers. The COVID-19 crisis is likely to exacerbate this phenomenon, as the number of jobs offered by large firms is likely to shrink, while preference for job security is likely to increase even further. Measures to further support youth employment in the wake of the crisis and limit scarring effects could include gathering evidence on the impact of the crisis by age group to inform decision making, anticipating the distributional effects of policy action across different age cohorts, updating policies in collaboration with youth stakeholders and providing targeted services for the most vulnerable youth populations (OECD, 2020f).

To address skills mismatches, the government has stepped up career counselling, developed apprenticeships and vocational education (notably Meister schools) and introduced incentives for tertiary education institutions to propose more market-relevant degrees. In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, additional funds will be allocated to job training programmes and the creation of jobs for young adults (Box 2.1). An ambitious plan to support youth employment was announced in March 2018, extending previous measures, but also representing a shift from indirect measures, such as job subsidies, to steps directly benefitting youth, like tax exemptions and in-work benefits (OECD, 2019d). Career guidance and counselling will need to be developed further, in particular through increased resources for the public employment service (see below) and stronger involvement of employers. Creating a one-stop-shop online portal for career guidance to replace the various websites currently available would also help (OECD, 2020e). Developing job opportunities would also improve young Koreans’ life satisfaction and possibly facilitate family formation and raise the fertility rate. Importantly, efforts to promote youth employment should complement, rather than substitute for policies to increase older workers’ employment, as OECD evidence shows that older workers do not crowd out youth (Box 2.5).

Foreign-born accounted for only about 3% of the Korean population in 2016 and for 3.7% of the economically active population. These shares are among the lowest in the OECD. Nevertheless, temporary foreign workers alleviate labour shortages in some sectors, notably manufacturing SMEs, where they make up 10% of total employment. Around 10% of companies with more than five employees recruit foreign workers (OECD, 2019e). The Employment Permit System (EPS) has been successful in providing low-skilled, fixed-term workers to Korean firms, while protecting local workers from competition and substitution effects. It has also allowed the permanent settlement of ethnic Korean Chinese, primarily employed in services and construction.

However, EPS workers are allocated to an employer and job mobility is allowed only in the event that a worker cannot continue to work at the workplace for any reason not attributable to himself (e.g. illegal employment practices, company closure) and sector mobility is impossible. This prevents EPS workers from getting better jobs and pay and reduces employers’ incentives to improve their working conditions. Maximum duration of stay has been extended from three to ten years in several steps, as employers were keen to retain experienced workers. Nevertheless, EPS workers are still generally not eligible for income support from the Basic Livelihood Security Programme (BLSP) and the earned income tax credit (EITC). Although a possibility for skilled EPS workers to get an indefinitely renewable visa was opened in 2011, very few can meet the requirements. The rapid rise in educational attainment implies that Korean low-skilled workers will become increasingly scarce. Even though automation may reduce demand for low-skilled workers, foreigners are likely to be needed to fill some positions. The job mobility system for foreign workers should be gradually adapted to enhance their contribution to the Korean economy, to enhance their contribution to the Korean economy, while continuing to shield local workers from undue competition. Foreigners with permanent residence should also be granted access to the BLSP and EITC.

Box 2.5. Do older workers crowd out youth?

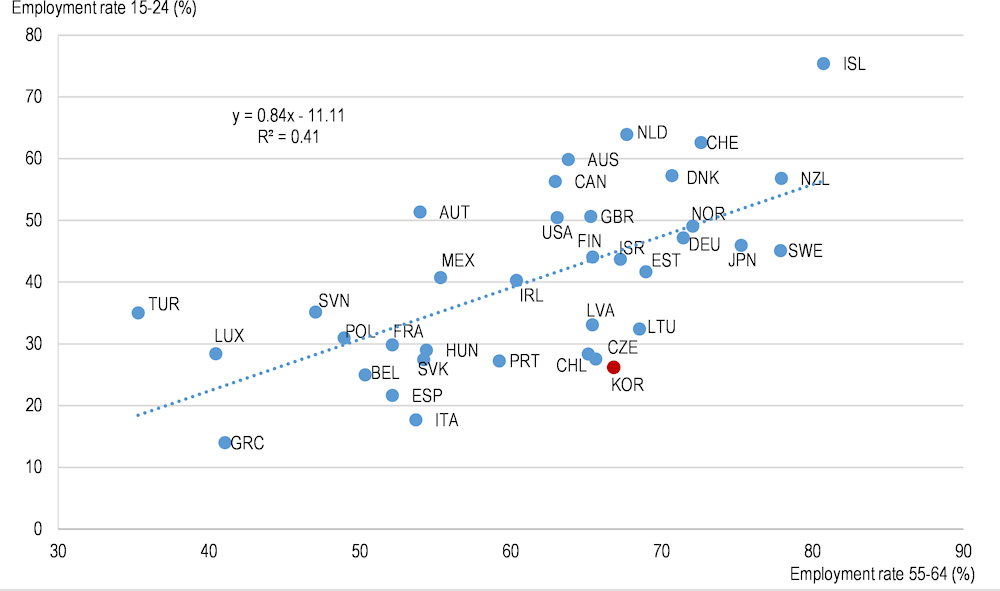

It is often believed that older workers’ early retirement creates employment opportunities for youth. But past policies to promote early retirement in the hope of lifting youth employment in OECD countries have proven ineffective. In fact, there is a positive relationship between the employment rates of old and youth across OECD countries (Figure 2.16). Underlying reasons are that demand for labour is not fixed (the so-called “lump of labour fallacy”) and that youth and older workers, having different skills and experience, tend to be complements rather than substitutes. Panel regressions across 25 OECD countries, including a range of controls for economic and labour market conditions, policies and institutions and differences in skills across generations, confirm that the relationship is not the result of exogenous factors affecting the employment rate of both groups. Moreover, the relation is not affected by the business cycle (OECD, 2013c).

However, concerns that delaying the mandatory retirement age may reduce youth employment persist in Korea, partly due to two Korean labour market specificities. The first is the cost of older workers in the seniority-based wage system, which may exceed their productivity, affecting companies’ competitiveness and therefore their ability to hire younger workers. The second is the competition between generations for high-quality jobs in the public sector and large firms, which are in limited supply (Hwang, 2013). The mandatory retirement age of 60 implemented in phases since 2016 is estimated to have increased employment for older workers (aged 55 to 60), but lowered the number of youth (aged 15 to 29) employed in private companies. At the company level, when one worker can benefit from the postponement of the retirement age, the number of older employees increases by 0.6, while the number of youth employed decreases by 0.2. The increase in elderly and decline in youth employment is particularly large in companies with over 100 employees and those with a low initial retirement age (Han, 2020b). To mitigate potential adverse side-effects on youth employment, extending working careers needs to be complemented by reforming the wage setting system and addressing labour market duality.

Figure 2.16. Youth and elderly employment rates are positively correlated

Source: OECD (2019), Employment rate by age group (indicator). doi: 10.1787/084f32c7-en (Accessed on 11 December 2019).

A more flexible labour market should be combined with stronger social protection

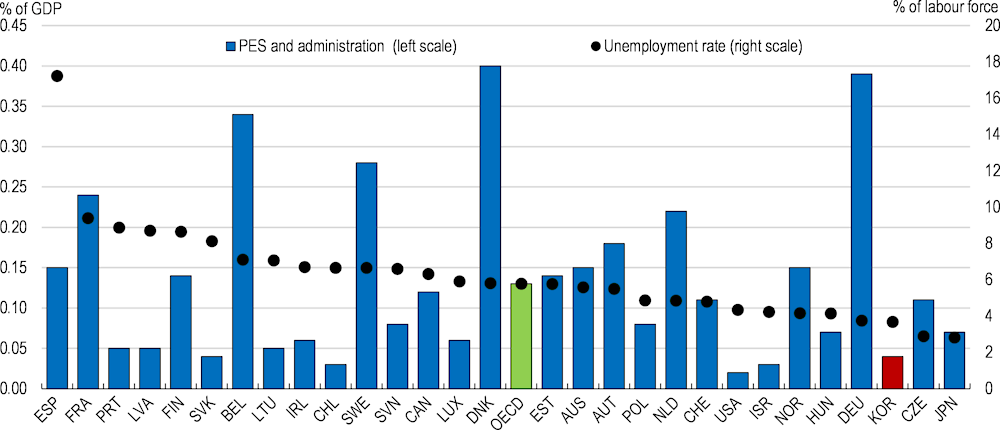

Beyond the measures aimed at raising employment in specific groups outlined above, a more flexible labour market would help reduce duality in the labour market and direct workers towards their most productive employment, which would alleviate shortages of skilled workers in SMEs. Easing employment protection for permanent workers, once the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis is well entrenched, would encourage firms to hire regular workers, as they would face lower costs in case of being subsequently forced to reduce staff. Reinforcing social protection, notably unemployment insurance, as well as active labour market policies, including job counselling, training and upskilling, would allow workers to smoothly transition from one job to another. In turn, more efficient reallocation of labour would raise productivity (see Chapter 3).

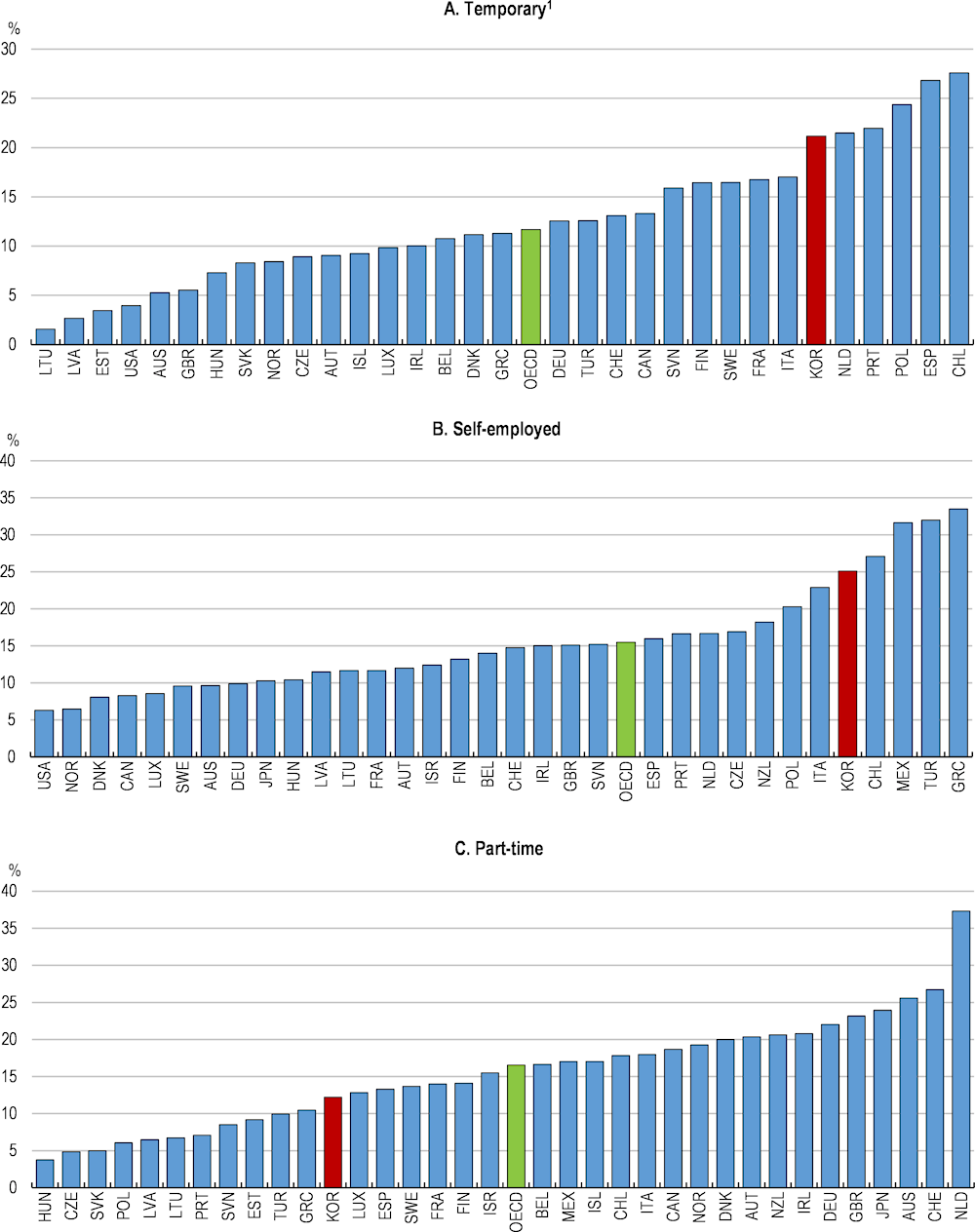

Reducing labour market duality is crucial to foster inclusive growth

The Korean labour market is characterised by strong duality, which affects older workers disproportionately (OECD, 2018c). Non-regular workers, which include temporary, part-time and atypical (e.g. daily workers, contractors, temporary agency) workers, account for about a third of salaried workers. For nearly half of them, being a non-regular worker is not their first choice (OECD, 2018b). Besides, non-salaried workers (self-employed and unpaid family workers) make up about a quarter of the employed population, well above the OECD average of about 15% (Figure 2.17). The COVID-19 outbreak highlights the vulnerability of non-regular workers. In the year to June 2020, while total employment declined by 1.3%, the employment of temporary employees and daily workers dropped by respectively 8.3% and 5.8%.

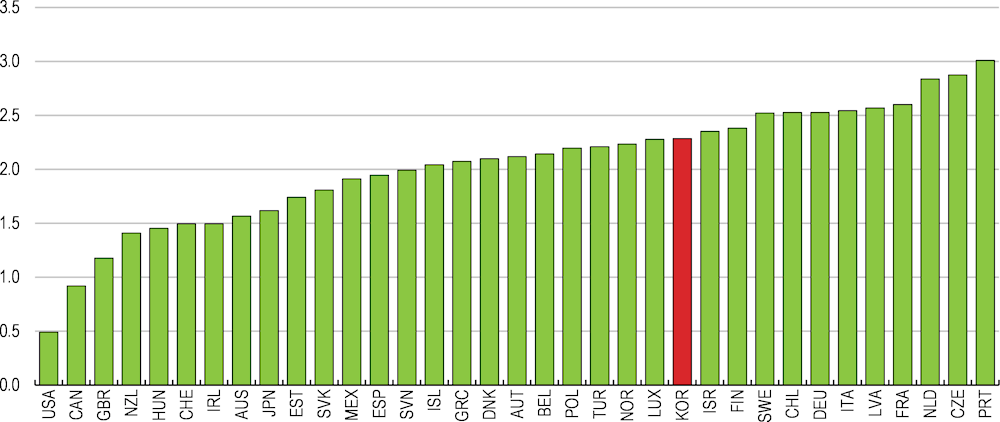

Reducing labour market duality requires reducing incentives for firms to employ non-regular workers, notably the need for flexibility and the lower labour costs (2018 OECD Economic Survey of Korea). Flexibility could be enhanced by lowering employment protection for permanent workers, which is relatively strong (Figure 2.18). An obstacle to reducing employment protection in Korea is the weak social safety net. To enhance labour flexibility and promote inclusive growth, policies will need to shift from protecting jobs to protecting workers (OECD, 2018a). Another important obstacle to labour mobility in Korea is the seniority-based wage structure, which will need to be gradually replaced by a more job and performance-based structure, as discussed above.

Figure 2.17. The share of non-regular employment is high

1. Per cent of dependent employment.

Source: OECD (2019), Temporary employment (indicator). doi: 10.1787/75589b8a-en; OECD (2019), Self-employment rate (indicator). doi: 10.1787/fb58715e-en; OECD (2019), Part-time employment rate (indicator). doi: 10.1787/f2ad596c-en (Accessed on 11 December 2019).

Figure 2.18. Permanent workers’ employment protection is relatively strong

Index of protection of permanent workers against individual dismissals, 2013

Note: The index ranges from 0 (no regulation) to 6 (detailed regulation).

Source: OECD (2018c), Working Better with Age: Korea, Ageing and Employment Policies.

Social protection remains weak despite recent reforms

Only about 43% of the unemployed receive benefits. Exceptional government emergency measures to support households during the COVID-19 crisis (Box 2.1) mitigate hardship. However, raising coverage on a more permanent basis would be desirable. While nearly 95% of regular workers were covered by employment insurance (EI) in 2018, coverage among non-regular workers, although on an upward trend, was only 71%, which is problematic given their vulnerability (2018 OECD Economic Survey of Korea). The low EI coverage of non-regular workers both entails a high risk of poverty and hampers the reallocation of workers towards more productive jobs, which is essential to sustain productivity growth (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2015). The legal coverage of EI has been gradually extended over the years, but compliance remains an issue for non-regular workers. The Duru Nuri social insurance support programme described above has increased coverage somewhat, but at a high deadweight cost. Since 1995, legislation enables undocumented workers to claim EI benefits to which they should have been eligible if contributions had been properly made and there were 22 000 claims in 2018.

Raising EI coverage further requires better legislation enforcement and premium collection. Employers that employ workers eligible for Employment Insurance, but fail to report their employees’ insured status are subject to a fine for negligence. In 2018, a fine for failure to report workers eligible for the insurance was imposed in about 85 000 cases. However, penalties for failing to register employees with EI are low, at KRW 30 000 per unregistered employee (about USD 25). A recent change in premium collection procedures is likely to facilitate EI enforcement. Since 2017, the Korea Workers’ Compensation and Welfare Service (KOMWEL), which already administered industrial accident compensation insurance, where the coverage of non-regular workers is above 90%, was tasked with the management of the EI insured. The KOMWEL calculates and imposes EI premiums, which are collected by the National Health Insurance Service, like all other social insurance premiums.