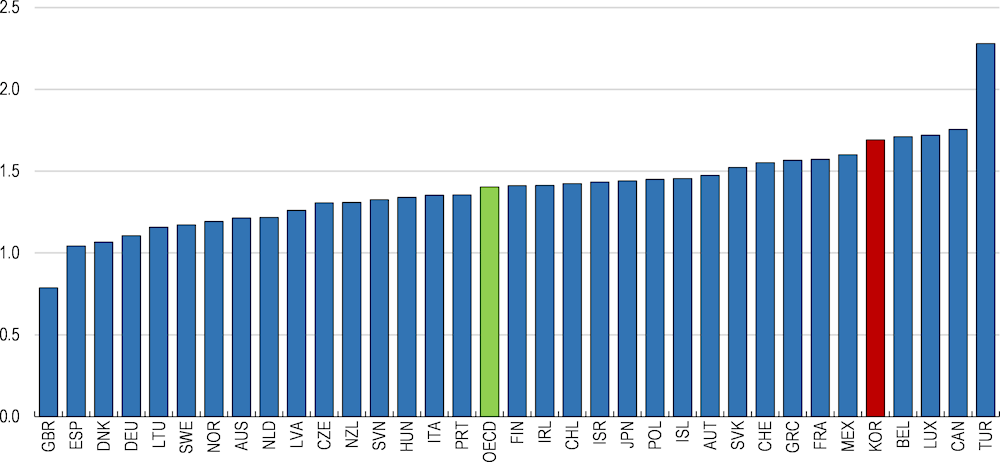

Korea was among the first countries hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, but a swift and effective policy response allowed to contain the spread of the virus (Box 1.1). Korea was able to avoid the extensive lockdowns of many other countries (Figure 1.1). Along with a range of government measures to protect households and businesses, this limited the damage to the domestic economy and output is shrinking less than in any other OECD country.

OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2020

1. Key policy insights

The economy will recover gradually from the COVID-19 crisis

Figure 1.1. Mobility for retail and recreation has remained relatively high

Note: Mobility trends for places like restaurants, cafes, shopping centres, theme parks, museums, libraries, and movie theatres.

Source: Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Report (27 July 2020).

Box 1.1. COVID-19 Korea’s strategy to contain the spread of the virus1

Korea was one of the first countries hit by COVID-19, with its first case confirmed on 20 January. Infections surged in the Daegu region in mid-February. However, a prompt reaction and an effective containment strategy allowed to limit the spread of the disease, with the number of new cases declining sharply from early March and the number of daily deaths falling since 24 March to around zero by late April. As of 3 August, 14 389 cases had been confirmed, and 301 deaths. Even though numbers are difficult to compare across countries due to differences in data collection and the varying timing of the epidemic, and notwithstanding the resurgence of some local clusters in recent weeks, Korea has been among the most successful countries in the world in limiting the spread of the disease and the number of deaths. Moreover, this was achieved without locking down any city or region, which minimised the economic impact of the outbreak.

The containment strategy has been based on foreign entry controls, testing, tracing and treating:

Entry ban and quarantine: ban on the entry of travellers coming from the Hubei province in China from early February 2020. As from 1 April, all persons arriving in Korea are subject to a 14-day self-quarantine and, as from 11 May, all persons arriving in Korea, regardless of nationality, undergo a mandatory COVID-19 test.

Testing: innovative methods, such as drive-through and walk-through testing facilities, along with the rapid development of tests, allowed extensive testing. As of 3 August, close to 1.6 million persons had been tested, among which 0.9% proved positive.

Tracing: rigorous epidemiological investigations are conducted, using credit card transactions, CCTV recordings and GPS data on mobile phones when necessary. Anonymised information on contacts is disclosed to the public and close contacts of positive cases are put under self-quarantine, with their health condition monitored remotely.

Treatment: patients are classified according to severity and directed towards appropriate treatment paths at hospitals for severe cases and residential treatment centres for milder cases. Health care resources and organisation were adjusted in response to the pandemic.

Digital tools, notably mobile apps, artificial intelligence and devices allowing remote work and service provision (including telemedicine) have played a key role in the strategy to contain the spread of COVID-19 (Chapter 3).

1. For further details, see Annex 1.B.

Source: Ministry of Health and Welfare, Government of the Republic of Korea (2020).

The government has taken appropriate and prompt measures to support the economy and alleviate hardship (Table 1.1). In the first phase of the recovery, temporary support for households and businesses will need to be adjusted gradually according to the pace of the recovery, taking into account the relatively low level and incomplete coverage of unemployment insurance, as well as sectoral specificities. If the crisis lingers, some temporary tax and social security deferrals and reductions will need to be prolonged and additional support for SMEs and firm restructuring may be necessary. Further investment in training and upskilling, along with increased support for the transition towards renewable energy and clean technologies would strengthen the second phase of the recovery, in which fiscal multipliers will be higher. Against this background, the main messages of this Survey are:

Government support should be provided to households and businesses until the economy is recovering. Low government debt allows for public growth-enhancing investments to spur the recovery and raise productivity. Monetary policy should remain accommodative, and if necessary, unconventional monetary policy measures should be considered to expand the degree of monetary accommodation.

The government should continue supporting workers after the crisis, especially with help to reskill, so as to facilitate the reallocation across sectors. Lifting labour participation and improving job quality for women and older workers will also remain crucial to mitigate the impact of ageing on labour inputs, and to reduce gender inequality and old age poverty.

Regulatory reforms to enhance competition and encourage innovation, especially by young firms, and further investments in training and upskilling, notably in digital fields, would facilitate the diffusion of technology and lift productivity.

Table 1.1. Policies to support the Korean economy

|

Date |

Measure |

Amount |

Main items |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Total support of more than KRW 277 trillion (14.4 % of GDP) |

Three supplementary budgets: KRW 59.2 trillion (3.1% of GDP) Financing support (loans and guarantees): over KRW 200 trillion (10.6% of GDP) Other: tax reduction, deferral of social security contributions |

||

|

5-20 February |

Support for the quarantine system, affected families and businesses |

KRW 4.3 trillion (Budget KRW 0.3 trillion, financing KRW 4.0 trillion) |

KRW 0.1 trillion for preemptive quarantine (budget) KRW 2.0 trillion for SMEs (loans and guarantees) KRW 0.3 trillion for low cost carriers (fee reduction) Policy preparation for worse-hit sectors, such as automobile, aviation, shipping, tourism and export industries |

|

28 February |

Support for households and reinforcing the financial sector |

KRW 16 trillion (Budget KRW 2.8 trillion, financing KRW 11.7 trillion, tax benefit KRW 1.7 trillion) |

KRW 2.8 trillion for consumption coupons and support for family care leave KRW 2.5 trillion for low interest rates loans and guarantees to SMEs. KRW 0.5 trillion for support to local credit guarantee funds (guarantees) KRW 8.2 trillion for liquidity support to the financial sector (liquidity) KRW 1.7 trillion for tax credit for reduction of rents and cut in individual consumption tax on cars (tax benefits) |

|

16 March |

Bank of Korea policy rate cut |

50 basis point policy rate cut to 0.75% Interest rate cut on the Bank Intermediated Lending Support Facility to 0.25% |

|

|

Passed 17 March |

First supplementary budget |

KRW 11.7 trillion (0.6% of GDP) -Expansion expenditure of KRW 10.9 trillion -Revenue adjustment of KRW 0.8 trillion |

KRW 2.1 trillion for virus prevention, diagnosis and treatment KRW 4.1 trillion for loans to SMEs and small merchants KRW 3.5 trillion for emergency livelihood support including gift vouchers and deduction in national health insurance KRW 1.2 trillion for aid to employees and severely affected provinces, including expanded employment retention subsidy and financial support Support of epidemic prevention and treatment for designated coronavirus disaster areas |

|

19 March 24 March |

Plan to provide financing to companies and stabilise financial markets (bonds and securities) |

Initially KRW 50 trillion Raised to KRW 100 trillion (5.1% of GDP)1 |

KRW 22.5 trillion for lending to SMEs, small merchants and self-employed (loans and guarantees) KRW 29.1 trillion to support large and mid-sized companies (loans and guarantees) KRW 17.8 trillion to avoid a credit crunch (loans and guarantees) KRW 20.0 trillion: Bond Market Stabilisation Fund to perform financial functions (liquidity provision funded by financial institutions) KRW 10.7 trillion: Securities Market Stabilisation Fund (liquidity provision funded by financial institutions) Expansion of foreign currency liquidity by raising ceilings on the foreign-exchange derivatives positions of banks and easing foreign-exchange market stability rules (26 and 28 March) |

|

19 March |

Currency swap agreement with the US |

USD 60 billion |

Bilateral currency swap agreement between the Bank of Korea and the US Federal reserve for 6 months (dollar liquidity) |

|

20 March, 10 April, 2 July |

Purchase of treasury bonds by the Bank of Korea |

KRW 4.5 trillion |

KRW 4.5 trillion (KRW 1.5 trillion on 20 March, 10 April and 2 July, respectively) purchases of treasury bonds for market stabilisation. |

|

8 April |

Support for exports and start-ups |

KRW 10.4 trillion |

KRW 10.4 trillion for financial support to export companies and start-ups and ventures (loans and guarantees) |

|

16 April |

Support for non-bank financial institutions |

KRW 10 trillion |

KRW 10 trillion: loans to bank and non-bank financial institutions such as securities and insurance companies for 3 months |

|

22 April |

Plan to support key industries and additional financing to SMEs and households |

KRW 85.1 trillion |

KRW 40 trillion: Key Industry Relief Fund guaranteed by government to purchase corporate debt and equity KRW 35 trillion for additional financing to SMEs (loans and guarantees) KRW 10.1 trillion for special employment security measures |

|

Passed 30 April |

Second supplementary budget |

KRW 12.2 trillion (0.6% of GDP) * KRW 3.4 trillion financed by debt issuance (the remaining by spending cuts) |

Emergency relief grants of up to KRW 1 million (USD 814) to all 21 million households - 2.7 million lower income households can receive grants in cash - The remaining 19 million households receive grants in voucher or credit card points for incentive to consumption A total of KRW 14.3 trillion, including a KRW 2.1 trillion of local government funds, is allocated for the relief programme |

|

28 May |

Bank of Korea policy rate cut |

25 basis point policy rate cut to 0.50% |

|

|

3 July |

Third supplementary budget |

KRW 35.1 trillion |

- Creation of about 550 000 jobs in publicly-initiated programmes and strengthening social safety nets (KRW 10.0 trillion) - Emergency loans to struggling small merchants, SMEs and large businesses (KRW 5 trillion) - New Deal projects investments (KRW 4.8 trillion) |

1. More detailed information can be found in Annex 1.B.

The recovery will probably be slow and uncertainty is exceptionally high

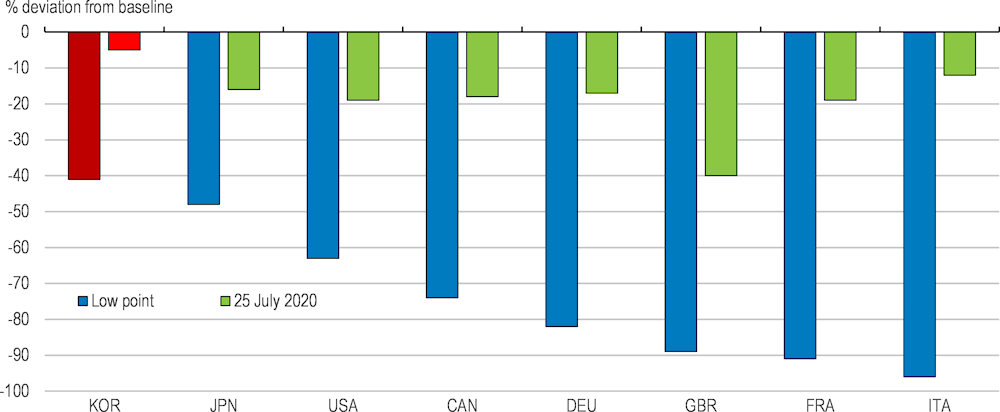

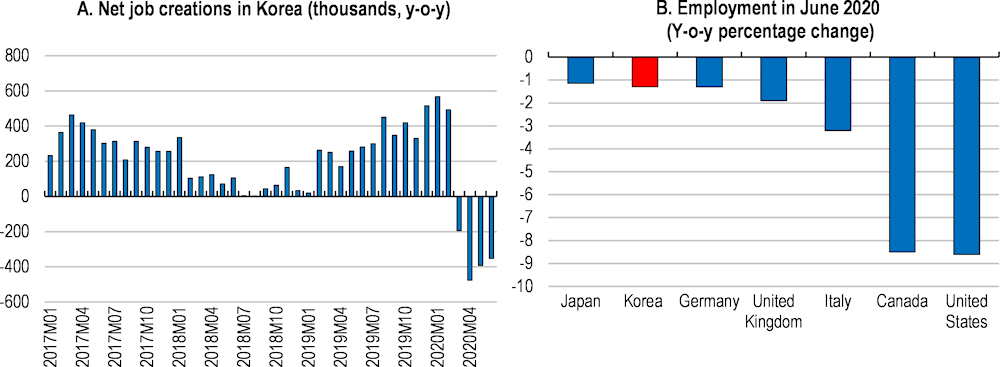

The COVID-19 crisis has led to falls in GDP of respectively 1.3% and 3.3% in the first and second quarters of 2020 (quarter on quarter, seasonally adjusted). The upswing in employment was abruptly interrupted in March (Figure 1.2, Panel A). The contraction is much smaller than in Canada and the United States, and comparable to the decline in Japan – in Europe, short-time work schemes damped the impact of lockdowns on employment (Panel B). The fall in employment in Korea affects most economic sectors, but is particularly severe in wholesale and retail trade, accommodation and food. Employment falls most among temporary and daily workers, as well as small business owners (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.2. The COVID-19 crisis has hit employment hard, albeit less than in most other countries

Note: For the United Kingdom, Office for National Statistics experimental monthly estimates of paid employees; For the United States, nonfarm employment.

Source: National statistical offices.

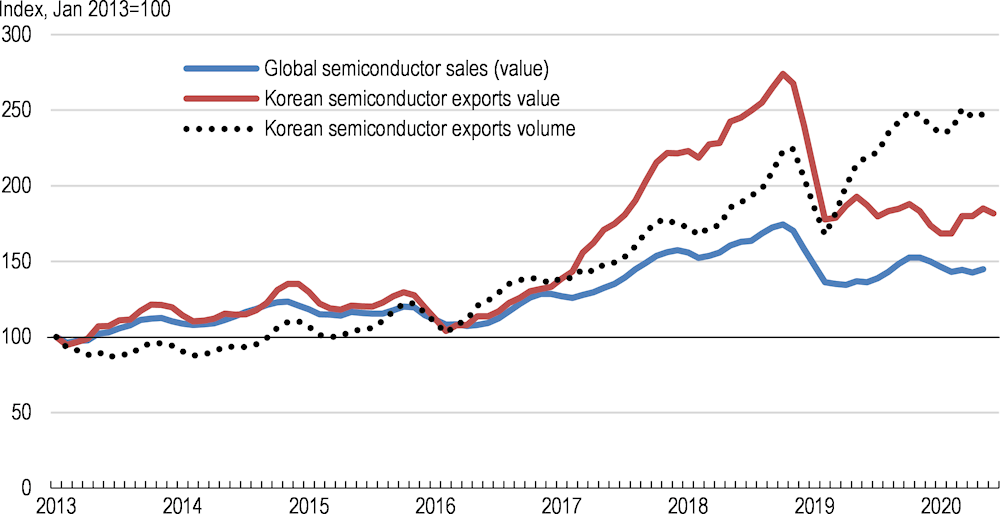

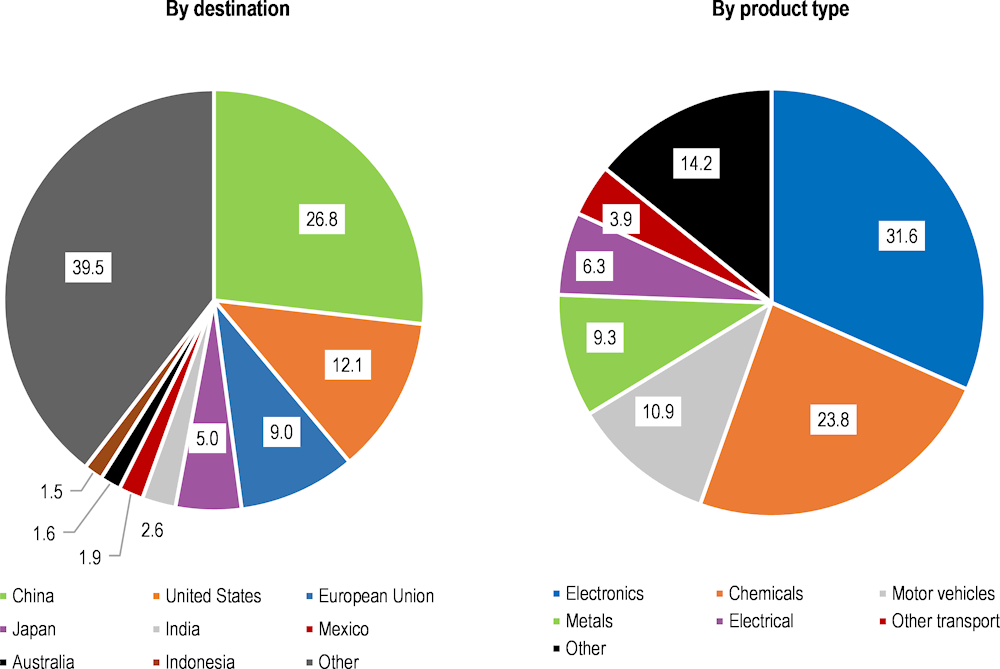

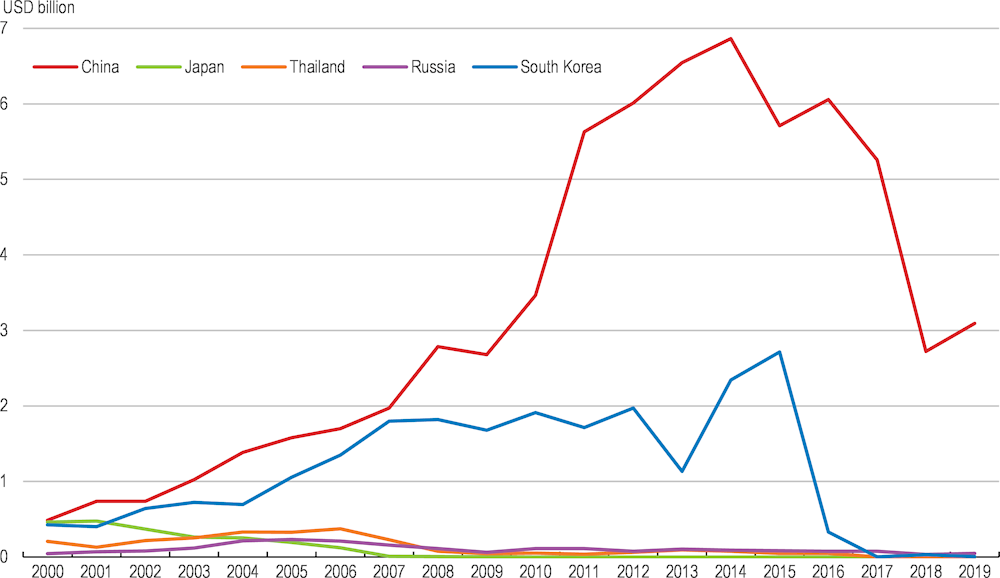

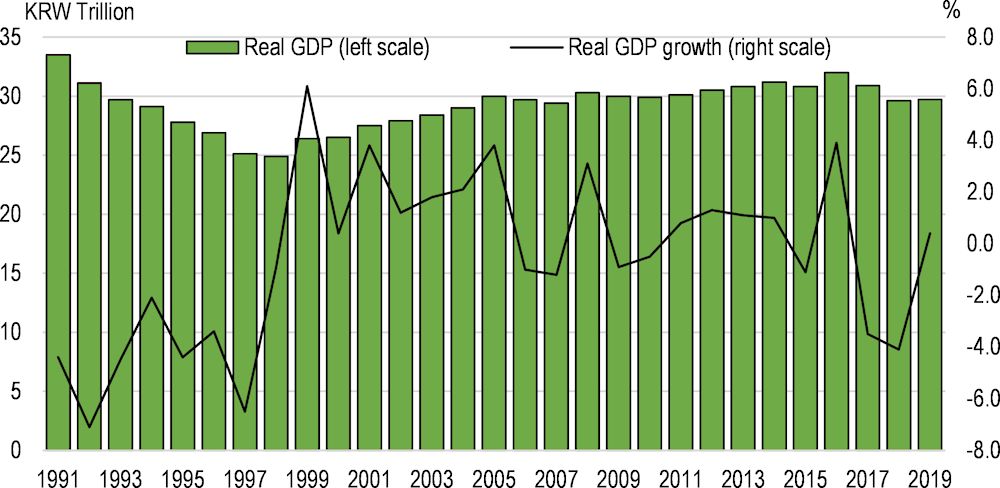

For an export-dependent economy like Korea, further disruptions in world trade and global value chains would be particularly harmful (Table 1.3). Exports are fairly concentrated both geographically and in terms of products (Figure 1.4). China and the United States combined account for nearly 40% of exports and Korea is deeply integrated in global value chains (GVCs), particularly for electronic goods. The outlook for semiconductor exports remains uncertain despite encouraging developments before the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis (Figure 1.5). The increasing diversification of Korea’s trade relations will increase its resilience over time. Several bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) have been signed, most recently with Indonesia, Israel and the United Kingdom (to preserve bilateral trade relations after Brexit). Korea aims at pursuing FTAs with more partners and is also part of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) under negotiation with the ten ASEAN countries, China, Japan, Australia and New Zealand.

Figure 1.3. Employment drops in services and among non-regular workers

Year-on-year percentage change (unless otherwise specified), June 2020

* Percentage points.

Note: The self-employed are divided between employers and own-account workers.

Source: Statistics Korea.

The projected contraction in GDP in 2020 is considerably milder than in other OECD countries, both in the single-hit scenario, which assumes no resurgence of the pandemic and in the double-hit scenario, which posits a global second wave of infections (OECD, 2019a). Private consumption will pick up as distancing recommendations are eased, albeit at a moderate pace as households exercise caution and suffer from income losses and relatively high unemployment. Industrial production will also normalise, but global supply chains will continue to experience disruptions for some time. The global recession is bound to have a durable impact on Korean exports and investment, especially in the double-hit scenario (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2. Macroeconomic indicators and projections under two epidemiological scenarios

|

Single-hit scenario |

Double-hit scenario |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

|

Percentage changes, volume |

||||

|

GDP at market prices |

2.0 |

-0.8 |

3.1 |

-2.0 |

1.4 |

|

Private consumption |

1.7 |

-3.6 |

3.7 |

-5.0 |

1.7 |

|

Government consumption |

6.6 |

7.1 |

5.9 |

7.3 |

6.0 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

-2.8 |

2.9 |

1.4 |

2.3 |

1.0 |

|

Final domestic demand |

1.1 |

0.4 |

3.4 |

-0.5 |

2.3 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

|

Total domestic demand |

1.1 |

0.3 |

3.4 |

-0.5 |

2.4 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

1.7 |

-5.7 |

4.4 |

-7.6 |

0.7 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

-0.6 |

-3.3 |

5.0 |

-4.3 |

2.9 |

|

Net exports1 |

1.0 |

-1.1 |

-0.1 |

-1.5 |

-0.8 |

|

Consumer price index |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

3.8 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

|

General government financial balance (% of GDP) 2 |

0.9 |

-2.8 |

-2.8 |

-3.1 |

-3.6 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

3.6 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

1.9 |

1.1 |

1. Contributions to changes in real GDP.

2. The structural general government financial balance has not been estimated in OECD Economic Outlook 107.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 107 projections updated to take into account incoming data through 23 July 2020.

Figure 1.4. Exports are fairly concentrated in terms of countries and product types (%), 2018

Source: OECD Quarterly International Trade Statistics; OECD Bilateral Trade in Goods by Industry and End-use (BTDIxE).

Figure 1.5. The outlook for global semi-conductors remains uncertain

Even though the economic downturn is milder than in other OECD countries and the government has taken extensive measures to support households and businesses (Table 1.1), the COVID-19 crisis creates new vulnerabilities. Household debt is relatively high and losses in income and rising unemployment will make reimbursement more difficult, although low interest rates help and further forbearance and debt deferral measures can be introduced if needed. Some households, notably self-employed, as well as some heavily indebted SMEs, already faced higher risks than ordinary homebuyers before the crisis (Bank of Korea, 2019a). The persistent concentration of economic power in the large business groups – the chaebols – may reduce the ability of the economy to adapt to an increasingly volatile global environment (2018 OECD Economic Survey of Korea).

Table 1.3. Events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Vulnerability |

Possible outcomes |

|---|---|

|

A more protracted global depression than expected. |

A very sluggish recovery from the COVID-19 crisis in trading partners would drag exports and investment down, with a major impact on Korean GDP growth. |

|

The COVID-19 crisis could trigger further disruptions in global value chains and an intensification of global trade tensions. Korea is deeply integrated in global value chains. |

Disruptions and related uncertainty in global value chains would affect both exports and investment. They could trigger a fall in the value of the won and capital outflows. |

|

The deterioration in economic conditions associated with the COVID-19 crisis weakens the ability to repay of some heavily indebted households, notably self-employed and SMEs, despite broad-based government support. |

The financial system is resilient, but some institutions may be vulnerable to large shocks, which could lead to credit contraction during the recession. Household distress would amplify the downturn, notably through a further reduction in consumption and employment. |

|

Geo-political tension in the Korean peninsula intensifies further. |

Although financial markets and capital flows have not been affected by the recent incidents, further escalation of tensions could create financial turbulence and weigh on economic growth and stability. |

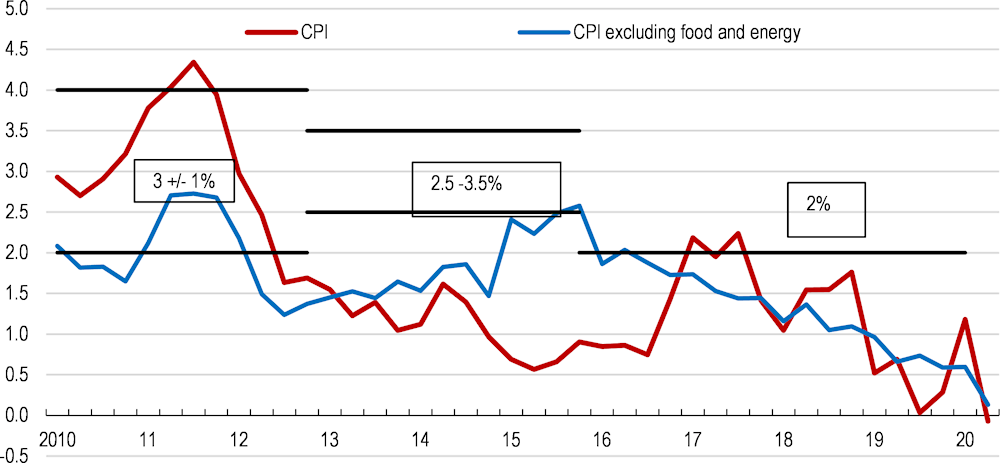

Monetary policy is accommodative but inflation remains below the 2% target

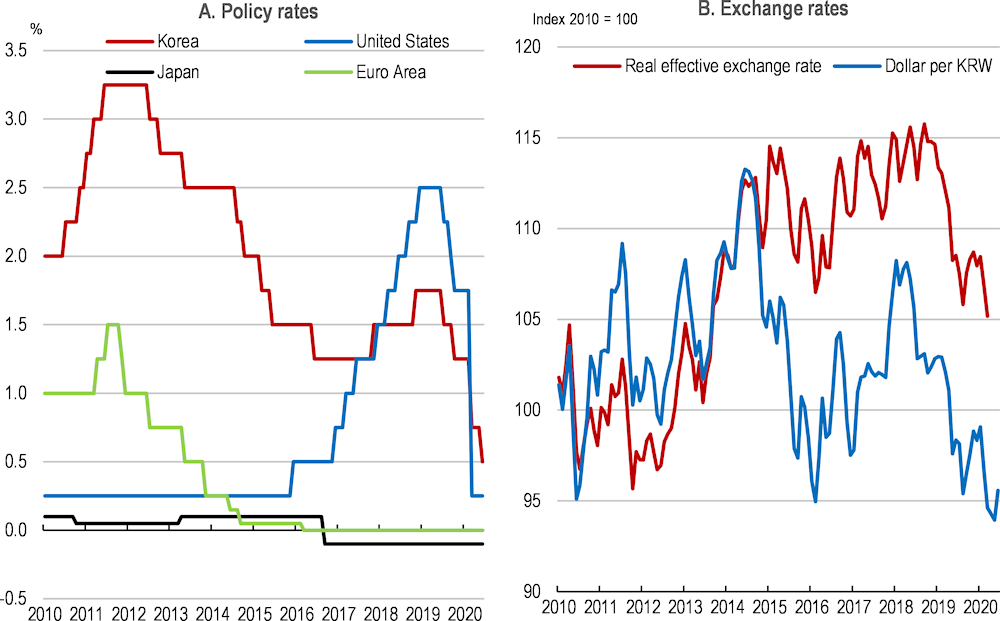

Inflation is undershooting its medium-term target (Figure 1.6), which prompted the Bank of Korea to cut its policy rate by 25 basis points already twice in 2019, in July and October to 1.25% (Figure 1.7, Panel A). The COVID-19 crisis brings further disinflationary pressures, to which the Bank of Korea responded swiftly by cutting its policy rate by 50 basis points and introducing a range of measures to provide liquidity and support financial markets in March 2020. The policy rate was cut further by 25 basis points to 0.5% in May 2020 (Table 1.1). The Won depreciated somewhat (Figure 1.7, Panel B). If low inflation and sluggish activity persist longer than expected, further monetary policy accommodation needs to be considered. Because little space is left for further policy rate cuts, the Bank of Korea should stand ready to adopt unconventional monetary policy measures going beyond liquidity support, like the purchase of government bonds to lower long-term interest rates.

Figure 1.6. Inflation is well below the 2% target

Note: In boxes, the medium-term consumer price inflation target.

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook Database.

The Bank of Korea Act stipulates that “the Bank shall contribute to the sound development of the national economy through ensuring price stability, while giving due consideration to financial stability in carrying out its monetary policy” (Bank of Korea, 2019b). The inclusion of financial stability considerations in the central bank’s mandate has merits, since monetary and macro-prudential policies can be complementary (Bruno et al., 2017). At the current juncture, economic growth is expected to be sluggish and inflationary pressures on the demand-side are forecast to remain weak due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the Bank of Korea should maintain its accommodative monetary policy stance. Meanwhile, concerns about financial imbalance risks are intensifying as housing prices have been rising in an increasing number of areas, and lending to households has accelerated again recently under the accommodative financial conditions. The Bank of Korea should continue to pay close attention to changes in macroeconomic conditions and developments of the COVID-19 pandemic and financial stability risks, such as an over-concentration of capital in the real-estate market, while maintaining its accommodative policy stance to support the economy.

Figure 1.7. Monetary policy has been eased and the won has depreciated somewhat

Strong public finances allow stimulating the economy

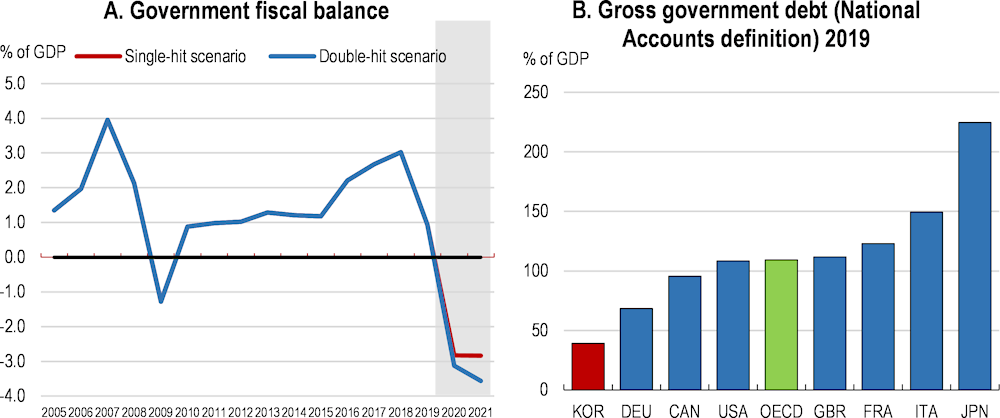

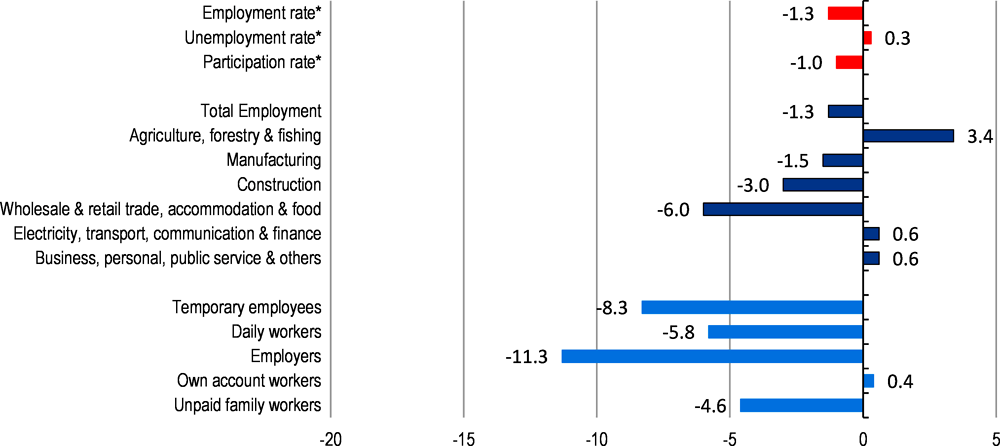

The government has appropriately responded to the COVID-19 crisis by providing additional fiscal support to the economy. The budget balance will move from a surplus of 0.9% of GDP in 2019 to a deficit of around 3% of GDP in 2020 (Figure 1.8, Panel A), reflecting in particular a fiscal stimulus of 3.1% of GDP. Government debt was less than 40% in 2019, lower than in all G7 countries and far below the OECD average of over 100% (Panel B). Sound public finances provide room to increase spending in the current downturn, even though the medium-term implications should be monitored carefully, especially when permanent spending measures are implemented. Temporary fiscal support should remain in place in the first phase of the recovery, before shifting towards more investment spending in the second phase. In the longer run, public spending is set to increase due to population ageing, which will require government revenue increases to ensure fiscal sustainability. Total tax revenue amounted to 28.4% of GDP in 2018, compared to an OECD average of 34.3% (OECD, 2019b), despite defence spending of over 2% of GDP, a share only surpassed in the OECD by Israel and the United States.

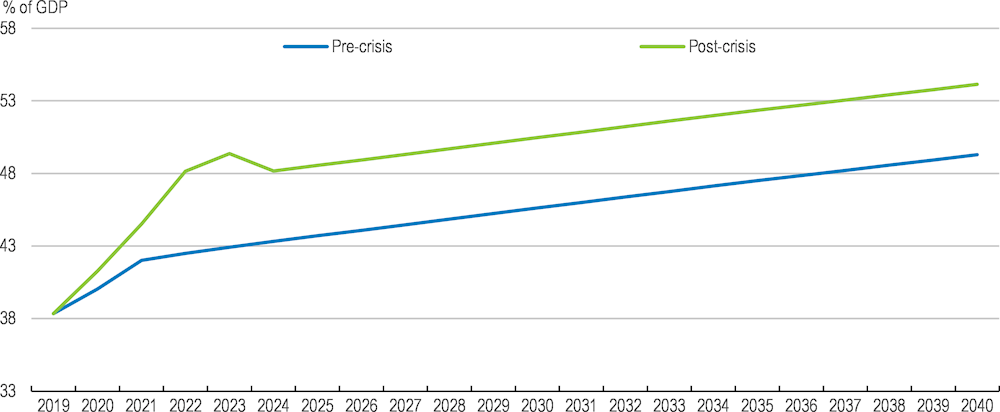

Figure 1.8. Sound public finances leave room for fiscal stimulus

The decline in government revenue and massive fiscal support to the economy will push up government debt. At the current juncture, uncertainty is extremely high and any longer-term extrapolation is purely illustrative. Here, gross government debt is posited to increase through 2021 in line with the budget deficit, as projected in the event of a double-COVID-19 hit, with the deficit then assumed to be reduced gradually and to revert to its pre-crisis path by 2025. In that case, debt jumps to more than 48% of GDP in 2023 (Figure 1.9). Thereafter debt grows in parallel to its pre-crisis path, where the increase in spending due to ageing and increased demand for public services is derived from the OECD long-term model estimates (Guillemette et al., 2017).

Figure 1.9. Potential impact of the COVID-19 crisis on gross government debt

Note: This figure is based on the Economic Outlook 107 double-hit scenario updated to take into account incoming data through 23 July 2020. The increase in debt after 2021 in the pre-crisis scenario is driven by rising spending due to ageing and rising demand for public services, as derived from the OECD long-term model estimates (Guillemette et al., 2017).

Source: OECD calculations.

Table 1.4. Past recommendations on fiscal policy

|

Main recent OECD recommendations |

Action taken since the 2018 Survey or planned |

|---|---|

|

Control spending in line with the Fiscal Management Plan to help ensure a sustainable fiscal balance in the long run. |

The government set fiscal balance and government debt targets, and makes sure that total expenditure lies close to the target set out in the five-year National Fiscal Management Plan. |

|

Allow public spending as a share of GDP to increase in the face of population ageing in the long run. |

Government spending has been increasing much faster than nominal GDP since 2018. |

|

Use taxes that are relatively less harmful to economic growth, notably the VAT, to finance rising social spending. |

VAT is applied on cloud services provided by multinational companies in Korea since December 2018. |

|

Reallocate public spending to social welfare as planned. |

Public spending for health, welfare, and employment sector increased significantly (+11.3% in the 2019 budget). |

The financial system remains solid, but the COVID-19 crisis raises vulnerability

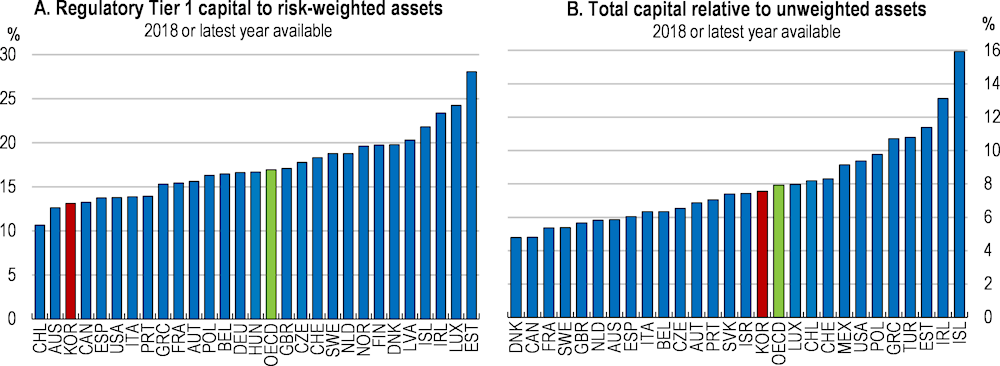

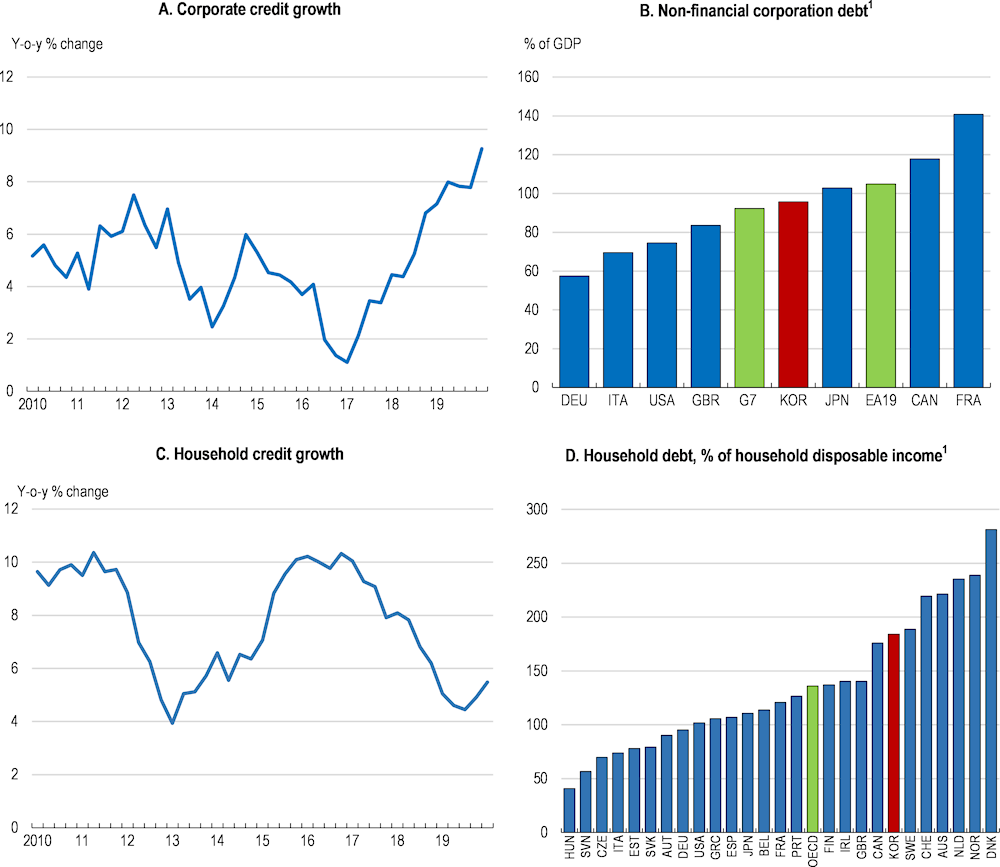

The COVID-19 crisis generates liquidity risks, which are mitigated by the measures taken by the government and the Bank of Korea (Table 1.1). Some businesses in the sectors most affected by the pandemic are likely to suffer persistently low activity, which increases solvency risks, all the more as the crisis lingers. Regulatory Tier 1 capital is well above mandatory requirements albeit in the lower part of the OECD distribution (Figure 1.10, Panel A). Delinquency rates are low, even though they edged up for some regional banks already in the pre-crisis period for the self-employed, as business conditions deteriorated. The overall leverage ratio is close to the OECD average (Panel B). Corporate credit growth has been relatively strong (Figure 1.11, Panel A) and corporate debt relative to GDP is slightly higher than the G7 average, although somewhat lower than in Japan and the European Union (Panel B). Household credit growth slowed following the introduction of a debt service ratio limit in 2018 and a tightening of regulations for non-bank financial institutions since 2017, but remains higher than household income growth (Panel C). The ratio of household debt to disposable income is above the OECD average, but below levels reached in Northern Europe (Panel D).

Figure 1.10. The unweighted leverage ratio is close to the OECD average

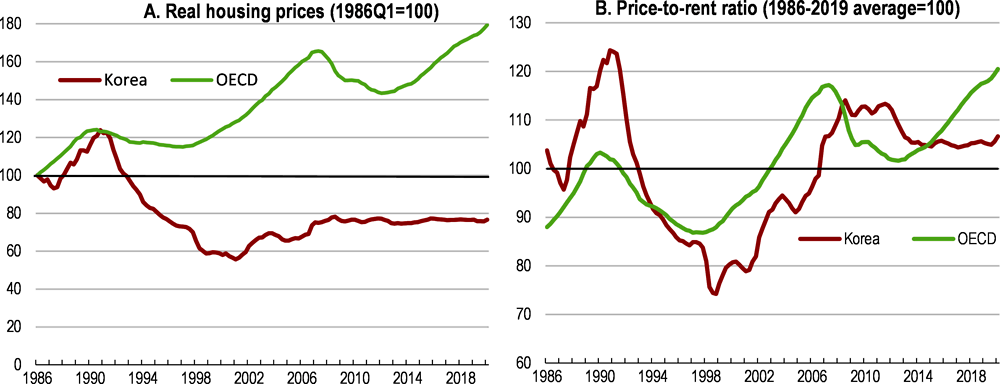

Real housing prices have been stable at the national level over the past decade (Figure 1.12, Panel A), thanks to more responsive supply than in most OECD countries and prudent financial policy. The price-to-rent ratio is also close to its historical average (Panel B). Self-employed borrowers, however, are facing higher risks, notably in wholesale and retail trade, and in accommodation and restaurants, where the COVID-19 crisis has curtailed activity (Bank of Korea, 2019a). Moreover, housing prices in some parts of the Seoul metropolitan area and the provinces have increased. The government has recently announced additional measures to curb housing price increases, including tighter mortgage lending rules, higher capital gains tax rates, property tax increases for homeowners holding several dwellings, and regulatory revision to boost housing supply.

Korean finance has made efforts to become greener, for example through the issuance of green bonds and the commitment of several Korean companies to follow the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations. However, disclosure remains limited in Korea despite requirements from the 2012 Greenhouse Gas and Energy Target Management Scheme and the 2014 National Pension Act (Cambridge Centre for Sustainable Finance, 2018).

Figure 1.11. Aggregate corporate debt is moderate but rising and household debt is high

1. 2018 or latest year available.

Source: Bank of Korea, Bank for International Settlements and OECD, Economic Outlook Database.

Figure 1.12. At the national level, housing prices have been stable

Note: In Panel A, real housing prices are deflated using the private consumption deflator.

Source: OECD, House Price database.

Financial authorities need to consider taking into account climate-related risks in financial markets, as done for instance by the Bank of England (Carney, 2015). Climate events, such as droughts, generate aggregate supply shocks and depreciate assets. Decarbonisation has impacts on the asset prices of long-lived energy-related infrastructure. Because of market imperfections, financial markets will not on their own respond adequately to these risks (Krogstrup and Oman, 2019).

Table 1.5. Past recommendations on financial policy

|

Main recent OECD recommendations |

Action taken since the 2018 Survey or planned |

|---|---|

|

Consider further tightening loan-to-value (LTV) and debt-to-income (DTI) regulations on mortgage lending depending on the impact of the recent changes. |

The cap on LTV was tightened to 0-40% for homebuyers to buy a house in “overheated” or “bubble-prone” areas, depending on the housing price. The cap was also tightened to 30-50% in the adjustment-targeted areas. Further regulations are imposed on a homeowner holding multiple houses in the regulated areas. The DSR (debt service ratio) regulation in the “overheated” or “bubble-prone” areas was tightened as well. |

The Bank of Korea joined the Network for Greening the Financial System, a voluntary network of central banks promoting sustainable growth and joint management of climate change-related financial risks, in November 2019. The Network’s recommendations are non-binding, but will help incorporate climate-related risks into financial stability monitoring and supervision (NGFS, 2019). Korea could consider following the United Kingdom, where the financial supervisor requires financial intermediaries to report their climate-related exposures since April 2019, or France, where the Law for the Energy Transition and Green Growth requires listed companies to disclose financial risks and institutional investors to report how investment policies align with the national energy and ecological transition.

The fruits of Korea’s past economic performance have not been equally distributed

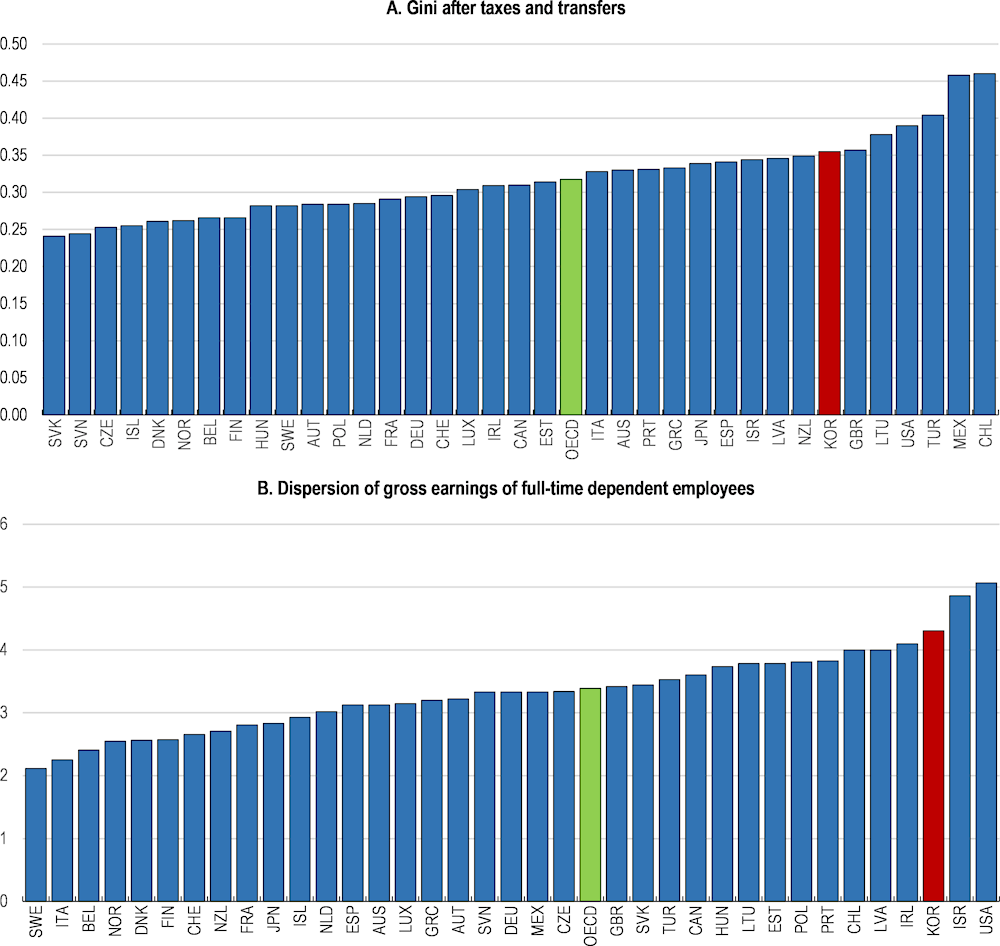

The COVID-19 crisis increases inequality, despite income support, job retention measures and the creation of public jobs for the elderly and other low-income groups. The duality of the Korean labour market – the large gap in wages, working conditions and social coverage between regular and non-regular workers – implies that non-regular workers, with insecure jobs and in many cases insufficient social insurance, are most vulnerable to shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic. Many older workers work in small businesses in the service sector particularly affected by the virus outbreak. In addition, physical distancing measures have tended to isolate them from work and social activities. Korea’s relative poverty rate is the third highest OECD-wide, driven by the worst old-age relative poverty rate in the OECD, even though the country achieved one of the world’s most impressive economic performances over the past half century, sometimes referred to as the “Miracle on the Han River” (Koen, 2019). While early phases of industrialisation generated strong income growth for most of the population, growth has become less inclusive since the 1997 financial crisis (Kim, 2011). Income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient after taxes and transfers, is the seventh highest in the OECD (Figure 1.13, Panel A), reflecting wide wage dispersion (Panel B) and limited redistribution, compared with most other OECD countries. Population ageing and skill-biased technological change threaten to increase inequality further unless labour market duality is reduced, skills are upgraded, older workers get access to better jobs, pension adequacy improves and the social safety net is strengthened.

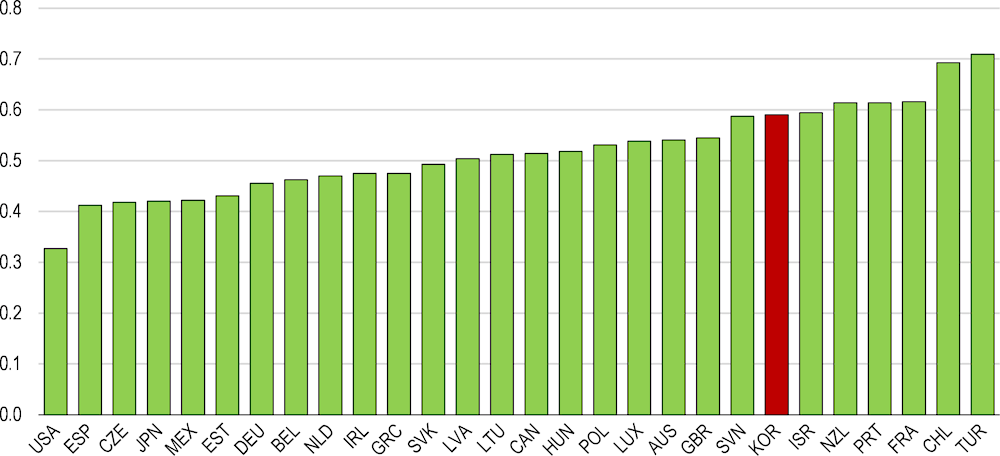

The government has taken several measures in recent years to tackle income inequality. The minimum wage was raised by 16.4% in 2018, bringing it to a relatively high level in relation to the median wage (Figure 1.14). In 2019, the minimum wage was raised by 10.9%, the third highest increase in the OECD, behind Lithuania (38.8%) and Spain (22.3%). While the rapid increase contributed to reducing wage inequality, it may have affected the employment of low-skilled workers, as suggested by weakness in employment developments in labour-intensive sectors, even before the COVID-19 crisis, although weak demand has also contributed. SMEs are affected by higher labour costs, despite subsidies to help them adjust (Choi, 2018). Accordingly, the minimum wage was raised by 2.9% for 2020 and, in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, by 1.5% for 2021. The government has more than tripled the amount spent on the earned income tax credit (EITC) in 2019 and doubled the number of recipients, through lower qualification requirements and higher asset and income ceilings, allowing nearly one household in five to receive an EITC, with a total cost of around 0.2% of GDP. The EITC is an efficient tool to increase low-paid workers’ income, especially in countries with high wage disparities (OECD, 2018a; Immervoll et al., 2007).

As shown above, non-regular workers have suffered much larger job losses than regular employees since the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis, highlighting the need to strengthen the social safety net, both in crisis time, as is being done during the COVID-19 crisis (Table 1.1), and on a more permanent basis. Social protection remains weaker than in most other OECD countries, despite the gradual extension of Employment Insurance to most workers, as compliance remains insufficient, notably for non-regular and small company workers. Their rights should be better enforced. Employers that employ workers eligible for Employment Insurance, but fail to report their employees’ insured status are subject to a fine for negligence. In 2018, a fine for failure to report workers eligible for the insurance was imposed in about 85 000 cases. Introducing a degree of statutory employer liability for all workers and a cash sickness benefit should also be considered, building on the crisis measures taken in the context of COVID-19. Employees who are (self-) quarantined or hospitalised due to COVID-19 are entitled to paid leave from the employer or living allowance from the government (Chapter 2). The New Deal includes a sickness benefit implementation study in 2021 and a pilot project for households, including low-income families, in 2022. Strong focus should be on rehabilitation and return to work, including clear protocols defining the rights and duties of workers, employers, doctors and insurance authorities, and regular work capacity assessments (OECD, 2018b).

Figure 1.13. Income inequality is relatively high

2017 or latest

Note: Whole population. The Gini coefficient ranges from 0 (no inequality) to 1 (maximum inequality). The dispersion of gross earnings refers to the ratio of the top to the bottom decile of the wage distribution.

Source: OECD, Income Distribution Database and Decile ratios of gross earnings dataset.

Figure 1.14. The minimum wage is high relative to the median wage, 2018

Note: Refers to gross wages.

Source: OECD, Minimum relative to average wages of full-time workers dataset.

Several other measures are being implemented to reduce inequalities, including extensions of social and health insurance coverage, the creation of public sector jobs, in particular for older workers, investments in vocational education, and increases in basic pensions. The pension system has yet to mature and means-tested support is low. The Basic Pension should be raised further and more focussed on the elderly in absolute poverty, access to the Basic Livelihood Security Programme should be facilitated and National Pension Scheme contributions and future replacement rates should be raised (Chapter 2). Late retirement is not preventing old-age poverty, as older workers tend to be employed in low-paid and insecure jobs (see below).

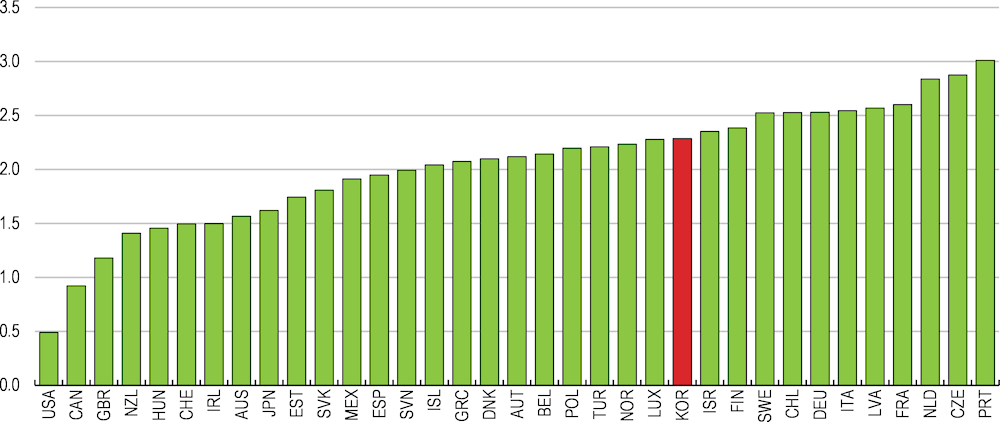

Lowering wage inequality will also require enhancing competition in product markets, as concentration and economic rents generally widen earning gaps between firms (Furman and Orszag, 2018). Employees in big business groups (chaebols) benefit from much higher wages and social protection than in SMEs (2018 OECD Economic Survey of Korea). Hence, reinforcing social protection should go hand in hand with loosening barriers to competition in product markets and labour mobility. Employment protection legislation is flexible regarding collective dismissals, but is relatively strict compared to other OECD countries regarding individual dismissals of regular workers (Figure 1.15). This contributes to labour market duality and hampers labour reallocation towards the most productive uses.

Table 1.6. Past recommendations on the labour market and inclusiveness

|

Main recent OECD recommendations |

Action taken since the 2018 Survey or planned |

|---|---|

|

Break down dualism by relaxing employment protection for regular workers and making it more transparent, while expanding social insurance coverage and training for non-regular workers. |

The coverage of industrial accident compensation insurance is extended to apprentices from universities from September 2018, construction equipment operators (about 110 000 persons) from January 2019 and to visiting service workers and cargo truck drivers (about 199 000 persons) from July 2020. The government plans to expand the coverage of employment insurance to dependent self-employed and freelance artists. In 2020, the government will introduce the National Learning Card to integrate learning account systems for the unemployed and the employed. |

|

Assess the impact of the 16.4% hike in the minimum wage in 2018 before raising it further. |

Some studies show that raising the minimum wage has reduced wage inequality. Further studies on the impact on the employment are needed. The Minimum Wage Commission is studying ways to improve analyses and research on the effects of the minimum wage. The minimum wage increase was set to 2.9% in 2020 and 1.5% in 2021, taking into account prevailing economic conditions. |

|

Increase the quality and availability of vocational education to reduce labour market mismatch and labour shortages in SMEs. |

The number of specialised high schools participating in industry-academia apprenticeship partnerships has increased markedly and the government plans to develop training in Fourth Industrial Revolution sectors. Since 2014, 15 369 businesses and 91 195 workers have participated in the “(work-study) dual system”. |

|

Further increase the Basic Pension and focus it on the elderly in absolute poverty. |

The government increased the Basic Pension for all beneficiaries (around 5 million) to up to KRW 250 thousand per month from KRW 200 thousand in September 2018. From April 2019, low-income elderlies (bottom 20%) receive an increased monthly basic pension of up to KRW 300 thousand. |

Figure 1.15. Permanent workers’ employment protection is relatively strong

Index of protection of permanent workers against individual dismissals, 2013

Note: The index ranges from 0 (no regulation) to 6 (detailed regulation).

Source: OECD, Employment Protection Database.

Korea’s economic achievements have not fully translated into well-being

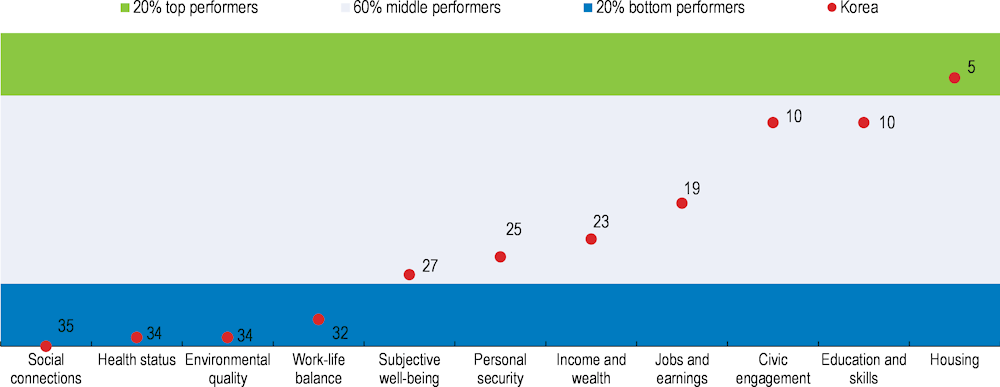

Korea’s income per capita has risen spectacularly over the past decades and is now close to the European Union average. However, looking at the well-being dimensions monitored by the OECD, Korea is among the top 20% OECD performers only on housing, although scores on education and skills, and civic engagement, are also fairly high (Figure 1.16). Korea ranks particularly low on social connections, perceived health status, environmental quality and work-life balance, highlighting the need to foster a more inclusive society. Meanwhile, the government submitted again the revision package of labour-related laws based on the recommendations of public interest members of the Economic, Social and Labour Council, together with the ratification proposal of the three International Labour Organization fundamental Conventions No. 87 on freedom of association, No. 98 on the right to organise and collective bargaining, and No. 29 on the prohibition of forced labour to the National Assembly. The approval by the National Assembly of the revision package and the ratification proposal would significantly improve Korea’s worker fundamental rights.

Figure 1.16. Well-being scores remain relatively low in many dimensions

Better Life Index, country rankings from 1 (best) to 35 (worst), 2017

Note: Each well-being dimension is measured by one to four indicators from the OECD Better Life Index set. Normalised indicators are averaged with equal weights.

Source: OECD Better Life Index, www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org.

Better use of labour resources and innovation can support growth

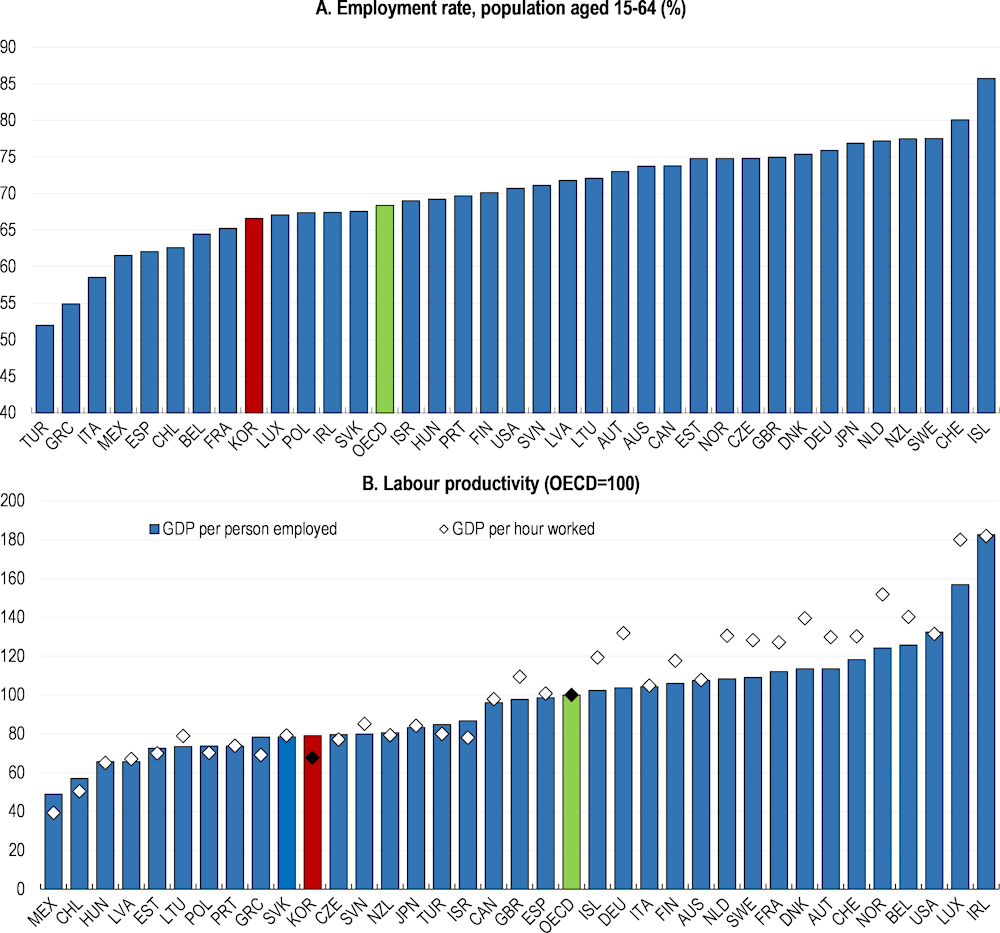

Korea’s employment rate is relatively low, even before the COVID-19 crisis (Figure 1.17, Panel A), largely reflecting low female employment, although delayed labour market entry of youth also contributes. Employment of older workers is high, but often concentrated in low-paid, low productivity jobs. Working time is among the highest in the OECD, but labour productivity is low (Panel B), whether measured per employee or per hour worked, mostly reflecting weak performance in SMEs and services. Hence, policies should aim at raising employment and productivity, while promoting better work-life balance (Fernandez et al., 2020).

Figure 1.17. Korea has scope to raise both employment and productivity

2018 or latest

Source: OECD (2019c), OECD Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b2774f97-en.

Boosting female and youth employment, prolonging careers and enhancing adult skills is essential

The gender employment gap for people aged 15-64 is nearly 18 percentage points, the fourth largest in the OECD. Relatively low wages and weak career prospects discourage many women from working. Even when working, many women are in non-regular employment, which prevents them from making the most of their generally high level of qualification. This may contribute to the gender wage gap, which is the widest in the OECD, at about 34% in 2018, as against an OECD average of about 13%. A number of recent measures, in particular to enhance childcare quality, improve work-life balance and facilitate return to work after career breaks could help reduce the gender gap. More broadly, a culture of gender equality needs to be promoted in the workplace and at home. The take-up of parental leave is still low, especially for fathers (OECD, 2019d). Recent measures to extend paid maternity leave to groups of workers not previously covered (self-employed and atypical workers) are welcome, but Korea should consider applying similar extensions to its paternity and parental leave entitlements. Introducing options to take parental leave for shorter periods at higher payment rates, as in Germany, could also help encourage take-up, especially by fathers. The gender wage gap should be addressed, for instance, by regularly publishing a national-level analysis of wage difference determinants to promote fairer wages. Gender-friendly policies could also have a positive impact on the fertility rate, which has fallen to around one, the lowest level in the OECD (Chapter 2).

Table 1.7. Past recommendations on promoting female employment

|

Main recent OECD recommendations |

Action taken since the 2018 Survey or planned |

|---|---|

|

Upgrade accreditation standards in early childhood education and care and make them mandatory. |

From June 2019, the Assessment and Accreditation system is mandatory and applied to all day-care centres. To achieve a 40% share of public childcare by 2021, the government is expanding the number of public day care centres (574 in 2018 and 654 in 2019). From September 2019, residential compounds with 500 or more households are required to establish a public day care centre. |

|

Raise qualification standards for teachers. |

From March 2020, teachers at day-care centres with a long-term employment gap (two years or more) are required to receive preliminary job training. The government plans to introduce a system to enhance teachers’ expertise. |

|

Relax fee ceilings on private childcare institutions and entry barriers. |

The government pays for the tuition for all children including in private childcare centres. A price ceiling applies for certain expenses such as field trips. The accreditation of public day-care centres, highly preferred by parents, is not restricted. The government implements policies to turn private daycare centres into public centres by signing lease agreements. |

The elderly in Korea tend to work longer than in most other OECD countries for several reasons, including a still immature National Pension Scheme. After being forced to leave their career job at a relatively early age for various reasons, including poor business performance, business suspension and family care, Koreans tend to move to jobs with lower pay. This generates old-age poverty, lowers well-being and productivity, and encourages working long hours (Hijzen and Thewissen, 2020). Expanding incentives for workers and employers to ensure that workers stay longer in their career jobs, promoting more flexibility in wages, better work-life balance and lifelong learning could boost the level and quality of employment of older workers. The mandatory retirement age was raised to 60 in 2016-17 and should be reviewed to increase it further over time, as companies move away from the seniority-based wage system. This needs to be complemented by further investments in adult education and enhancing its governance, notably through better coordination between ministries and with regional authorities and other stakeholders (OECD, 2020a, b). More broadly, a gradual rebalancing of active labour market policy from direct job creation, which currently accounts for about half of spending, to training and job counselling will be necessary to enhance job quality and employability. Public employment service resources need to be increased, along with second-career guidance for mid-career and older workers. The contributions of youth and immigrants to the Korean economy could also be enhanced by speeding labour market entry through further developing vocational training and career guidance, and gradually adapting the job mobility system for foreign workers, while continuing to shield local workers from undue competition (Chapter 2).

Less than half of youth aged 15-29 were employed before the COVID-19 crisis, the fifth lowest share in the OECD, reflecting long studies, as more than two-thirds of youth obtain tertiary degrees, but also slow transition from education to employment. The crisis is exacerbating this problem, with youth employment having declined rapidly since February 2020, particularly in the service sector, and further contraction expected over the coming months (Han, 2020). Labour market duality encourages young people to extend formal or informal education in the hope of joining large firms or the public sector, rather than SMEs, which often suffer from a shortage of skilled workers. To address skills mismatches, the government has stepped up career counselling, developed apprenticeships and vocational education (notably Meister schools) and introduced incentives for tertiary education institutions to propose more market-relevant degrees. Nevertheless, career guidance and counselling will need to be developed further, in particular through increased resources for the public employment service and stronger involvement of employers (Chapter 2).

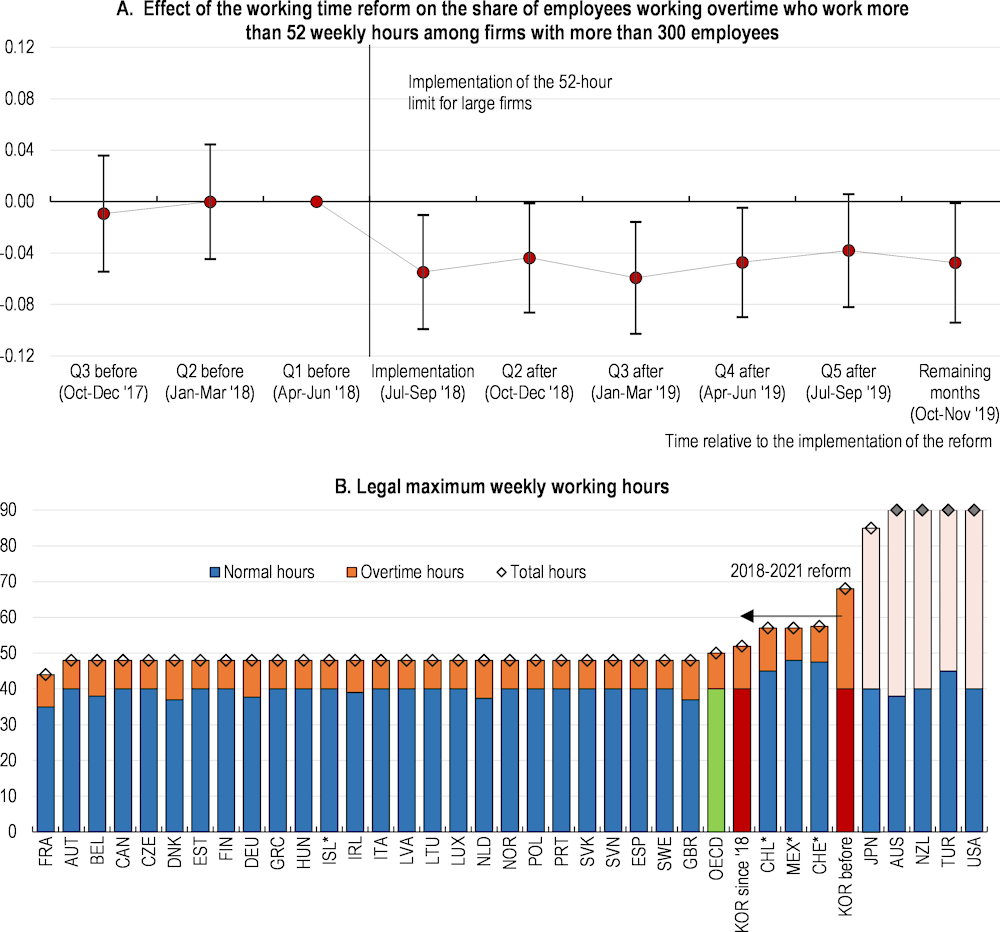

Changing Korea’s long working-hour culture requires more than lower legal working time limits

The current government is seeking to reduce the high incidence of very long working hours in an effort to improve job quality, health and productivity. Korean workers work a total of 1 967 hours per year, the third highest in the OECD and 300 hours longer than the OECD average (as of 2018). About 12% of workers work longer than 52 hours per week. Working very long hours increases the risk of burnout and work accidents, a major concern in Korea, promotes unhealthy lifestyles and undermines labour productivity (Saint-Martin et al., 2018).

A preliminary assessment of the ongoing working time reform to decrease the limit from 68 to 52 weekly working hours shows that this reduced the incidence of working more than 52 weekly hours by five percentage points or about a fifth of its pre-reform level among employees working overtime in large firms (Figure 1.18 Panel A). With the reform, Korea’s statutory working time limits have become in line with dominant OECD practice (Figure 1.18 Panel B, Box 1.2). The current reform builds on a previous reform implemented between 2004 and 2011 that reduced the regular working week from 44 to 40 hours. While it is too early to tell whether the ongoing reform will improve labour market outcomes beyond actual hours worked, worker health, productivity and wellbeing, several evaluations credit the previous reform with positive outcomes like fewer work accidents, healthier lifestyles and enhanced labour productivity (Lee and Lee, 2016; Ahn, 2016; Park and Park, 2019). Strikingly, labour productivity not only increased in hourly terms but also on a per person basis, meaning that hourly productivity improved sufficiently to offset the decrease in the number of working hours.

Box 1.2. Working-time reforms in Korea

The current government is gradually implementing a working time reform with the following elements:

The maximum number of total weekly working hours has been reduced from 68 to 52 by lowering the cap on overtime from 28 to 12. The new maximum applies to firms with 300 or more employees as of July 2018 and to firms with 50 or more employees as of January 2020 and will be extended to firms with five or more employees in July 2021, to give smaller firms more time to adjust. Firms with 5 to 29 employees are temporarily allowed an additional eight hours of overtime until December 2022, provided there is a written agreement with an employee representative.

The number of sectors exempt from total hours limits has been reduced from 26 to 5 as of July 2018. Sectors such as consumer goods sales, hotels and restaurants and finance now have to abide by the maximum limit. Exemptions still apply to certain types of transportation services and healthcare.

Firms will be obliged to offer the 15 public holidays as paid days off, or offer an alternative day off in agreement with an employee representative. Previously, firms were not obliged to provide (paid) leave on public holidays, although most larger firms did. This reform is also being implemented in a staggered fashion by firm size between 2020 and 2022.

A tripartite agreement was signed on a plan to extend the reference period of the flexible working hours system from three to six months, and a reform bill reflecting the agreement is currently pending at the National Assembly.

Source: Hijzen and Thewissen (2020).

Figure 1.18. Fewer individuals work very long hours as time limits were tightened towards OECD norms

Note: Panel A illustrates the effect of the reform, by showing the difference in the difference in the incidence of working more than 52 hours between large firms affected by the reform (with 300 or more employees) and slightly smaller firms not yet affected (with 100-299 employees), relative to the quarter before the reform (April-June 2018). Vertical bands indicate the 95% confidence intervals of each point estimate. It shows that the probability to work more than 52 hours decreased by about five percentage points in affected firms since the implementation relative to the quarter before the implementation, compared to the change in probability over the same period in slightly smaller firms. The sample consists of employees aged 18 and older working overtime in a non-exempt private sector and non-exempt occupation on a permanent contract.

Panel B: Normal working hours are those not subject to overtime regulation. Overtime working hours are those where overtime regulation applies. Total working hours are the sum of normal and overtime working hours. Data refer to 2018 (2019 for Japan) or 2011-12 for the countries with an asterisk (2010 for Israel). Dashed bars and grey diamonds indicate that no legislative maximum exists. Korea before 2018 refers to the situation just before the reform, while after refers to the situation in 2021 when the reform will be fully implemented. In European countries with only maximum total (and not normal) working hours, common collectively agreed maxima are used for maximum normal working hours (Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, United Kingdom).

Source: Hijzen and Thewissen (2020), using Economically Active Population Survey micro data, Eurofound (2019), ILO Working Conditions Laws Database (2013) and the OECD Working Time Questionnaire (2010).

While having more stringent working time limits is an important step in the right direction, more is needed to effectively change Korea’s long working-hour culture. A first concern is that small firms with fewer than five employees as well as firms in some sectors (e.g. transportation and storage, health care) remain exempt from working time regulations. Second, incentives to supply and demand long working hours should be mitigated. Important supply factors include low skills, low wages and concerns about future pensions, and demand factors relate to limited flexibility for employers to adjust employment according to business conditions and productivity (Hijzen and Thewissen, 2020).

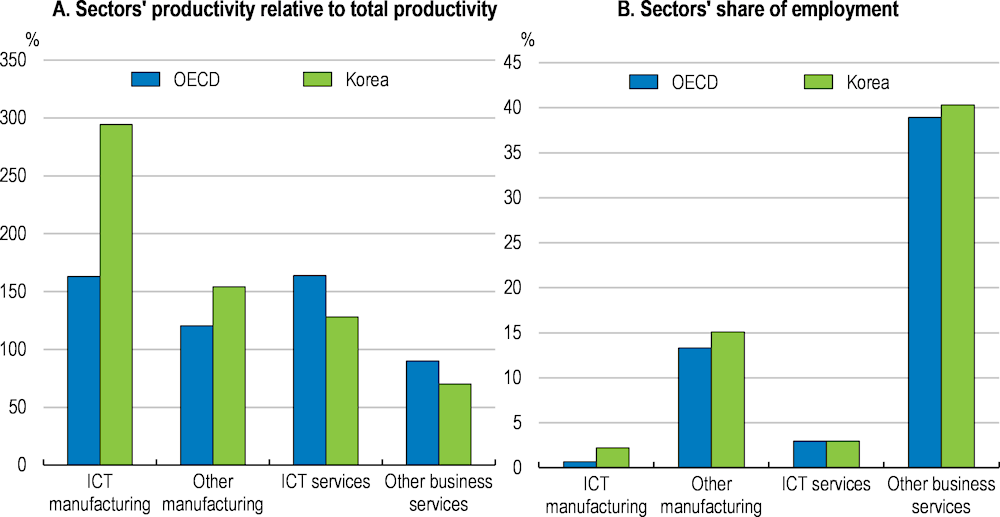

The diffusion of technology can boost productivity and well-being

Technology and digital tools offer vast opportunities to boost productivity (Chapter 3). The temporary lifting of the ban on telemedicine services during the COVID-19 crisis, which allowed patients to consult their doctors without risking mutual exposure to the virus, illustrates the benefits services based on new technologies can bring to the population (Box 1.3). Korea is one of the top players in emerging digital technologies (OECD, 2019e), with a large and growing ICT sector, outstanding digital infrastructure, almost generalised access to high-speed internet and the first nationwide introduction of 5G worldwide (OECD, 2017a; OECD, 2019f). However, while productivity is outstanding in ICT manufacturing and relatively high in other manufacturing, it is much weaker in services, including ICT services, which account for a large share of employment (Figure 1.19).

Box 1.3. Telemedicine: friend or foe?

Telemedicine is increasingly used across OECD countries, delivering health care in a wide range of specialties like neurology and psychiatry, using diverse techniques from remote monitoring to real-time video-consultations. Amid the COVID-19 outbreak, Korea has temporarily lifted its ban on telemedicine, allowing doctors to treat patients with mild symptoms on the phone. Between 24 February and 26 July, about 566 000 telemedicine bills were issued by 6 830 hospitals. While telemedicine helps limiting risks of infection between patients and doctors, it also meets high resistance among doctors who question the reliability of the diagnoses and data security.

Amid the COVID-19 outbreak, telemedicine services were made available in 23 other OECD countries. In Norway, the share of digital consultations in primary health care increased from 5% before the outbreak to 60% by March 2020. In the United States, teleconsultations increased from 6% to 50-70% of total consultations by March 2020 for some providers. In France, they increased from around 40 000 to almost 500 000 in March 2020. Evidence in other OECD countries (Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the Nordics) shows that health care can be tele-delivered in a safe and effective way, and can even lead to better outcomes than conventional face-to-face care, for instance for patients with diabetes or chronic heart conditions. It can also improve quality, timeliness, coordination and continuity of care, as well as knowledge sharing and reduced use of costly hospital care. Patients also tend to report high satisfaction and a sense of reassurance. Policymakers can encourage good practices of telemedicine through clear regulation and guidance, sustained financing and payment, and sound governance, in addition to appropriate training of both patients and health care professionals. They should also ensure telemedicine services are compatible with preserving patient safety and quality of care.

Source: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service; OECD (2020c); Oliveira Hashiguchi (2020).

Figure 1.19. Low-productivity sectors account for a high share of total employment

Note: Data refer to 2015. ‘ICT manufacturing’ includes manufacture of computer, electronic and optical products. ‘ICT services’ include publishing, telecommunication and IT services. ‘Other business services’ excludes the housing sector.

Source: OECD STAN Database.

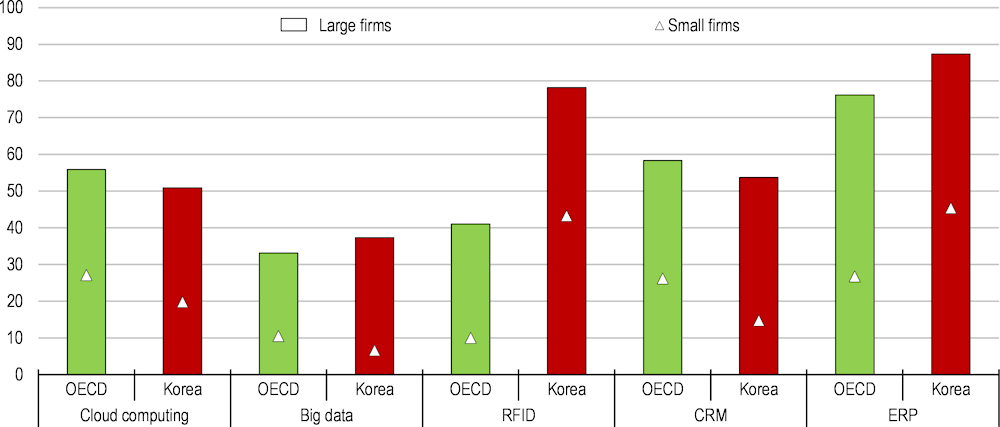

The diffusion of advanced digital technology is uneven (Figure 1.20). Korean firms have margins for improvement in the adoption of sophisticated digital technologies (Chapter 3). The lack of adequate skills and knowledge is the main barrier to the diffusion of digital technologies, especially in SMEs and among older workers. People lacking adequate digital skills are particularly disadvantaged as the COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged the “untact”, or contactless, economy, with remote work and many services provided via on-line platforms to limit physical contact. SME employees have limited access to training (OECD, 2020c). The digital skills gap between generations is the highest among OECD countries and exacerbates social inequality. Teachers are key to ensure students develop digital skills, but most teachers feel they are not sufficiently prepared for the use of ICT for teaching. Improving access to and quality of training for SME employees, older workers and teachers is necessary to allow them to adapt to more digitalised production systems and raise managers’ awareness of the potential of digital technologies. Promoting further collaboration between innovative companies, especially between SMEs and large enterprises, would facilitate the diffusion of digital technology, for instance through an open collaborative network to design new products and services, and exchange data (Fourth Industrial Revolution Committee, 2019). Amid the COVID-19 outbreak, Korea contained the spread of the virus, using advanced digital tools based on artificial intelligence and mobile apps, as well as remote access to daily life services (e.g. telework, online classes, e-commerce and telemedicine). The Korean authorities recently announced a Korean New deal to revive the economy, by facilitating the convergence of new and old industries through enhanced use of digitalisation. The New deal focusses on projects exploiting synergies between the government and the business sector, including strengthening data infrastructures, expanding data collection and usage, establishing 5G network infrastructure early and developing artificial intelligence. The New Deal also includes measures aimed at greening the economy and reinforcing the social safety net (Table 1.8). Building on the success of Korea’s COVID-19 containment strategy, a “K-quarantine model” will be systemised and exported.

Table 1.8. Overview of the Korean New Deal projects

|

Type |

Field |

Project |

Target |

Budget (2020-25, KRW trillion) |

Job creation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Digital New Deal |

Data, Network, AI (D.N.A) ecosystem |

1. Open data systems related to people’s lives 2. Diffusion of 5G and AI to all industries 3. Smart government based on 5G and AI 4. Korean-style cyber-security system |

Create data markets worth KRW 43 trillion in 2025 Increase the number of AI enterprises to 150 in 2025 from 56 in 2020 |

6.4 14.8 9.7 1.0 |

295 000 172 000 91 000 9 000 |

|

Digitalisation of education infrastructure |

5. Extend digital education infrastructure to all schools 6. Strengthen online education for universities and vocational training institutions |

Increase Wifi coverage to all schools by 2022 Build a digital education platform using big data |

0.3 0.5 |

4 000 5 000 |

|

|

“Untact” (non-face-to-face) industries |

7. Smart medical and care infrastructure 8. Diffusion of remote work culture in SMEs 9. Support online business of SMEs |

Build 18 smart hospitals equipped with 5G and IoT Increase the share of remote work to up to 40% |

0.4 0.7 1.0 |

5 000 9 000 120 000 |

|

|

Digitalisation of social overhead capital |

10. Establish a digital management system for core social overhead capital (e.g. transport and water networks) 11. Digital transformation of urban and industrial complex spaces 12. Establish smart logistics systems |

Install intelligent transport systems for major expressways and railroads Install disaster warning systems in risk areas |

8.5 1.2 0.3 |

124 000 14 000 55 000 |

|

|

Green New Deal |

Green transformation of city, space and living infrastructure |

13. Build zero-energy public facilities 14. Restore land, ocean and urban ecosystems 15. Establish a clean and safe water management system |

Eco-friendly remodelling of 225 000 public rental units Create 723 hectares of urban forests to reduce fine dust levels |

6.2 2.5 3.4 |

243 000 105 000 39 000 |

|

Diffusion of low carbon and renewable energy |

16. Build an energy-efficient intelligent smart grid 17. Lay the foundations to support the transition towards renewable energy 18. Expand green mobility such as electric vehicles and hydrogen fuel cell cars |

Extend the use of smart grids to cover 5 million households Raise the number of electric and hydrogen cars to 1 130 000 and 200 000, respectively |

2.0 9.2 13.1 |

20 000 38 000 151 000 |

|

|

Innovative ecosystem of green industries |

19. Foster leading green companies and create low-carbon and green industrial complexes 20. Create green innovation infrastructure such as R&D and finance |

Transform 1 750 factories into clean factories Construct 10 smart energy platforms |

3.6 2.7 |

47 000 16 000 |

|

|

Social safety net reinforcement |

Employment and social safety net |

21. Extend the employment safety net to most employees (e.g. employment insurance, industrial accident compensation insurance) 22. Reinforce the social safety net (Basic Livelihood Security Programme, sickness benefit) 23. Strengthen assistance for the unemployed (e.g. Job search allowance, vocational training) 24. Strengthen assistance to enter the job market 25. Strengthen industrial and work environment safety |

Increase the number of beneficiaries of Employment Insurance to up to 21 million Extend Basic Livelihood Security Programme benefits to an additional 1.13 million households |

3.2 10.4 7.2 1.2 0.6 |

- - 39 000 118 000 2 000 |

|

Human resources |

26. Foster digital and green talents 27. Reorganise the vocational training system 28. Strengthen digital access in rural areas and for vulnerable groups |

Internet access in all rural areas 70% of the elderly aged 70 and over will enjoy mobile internet |

1.1 2.3 0.6 |

25 000 126 000 29 000 |

|

|

Total |

114.1 |

1 901 000 |

The government supports R&D through the Korea Small Business Innovation Research (KOSBIR) programme and R&D grants to SMEs, which have contributed to lift corporate R&D investment, registration of intellectual property rights and investment in tangible and human capital. Nevertheless, results in terms of creation of value added and commercialisation have been disappointing (Lee and Jo, 2018; Yang, 2018). Support programmes should be reviewed and innovation vouchers should be introduced to better direct R&D subsidies towards innovative SMEs, in manufacturing and in services, and boost their productivity. Providing SMEs with innovation vouchers would encourage them to engage in innovative projects, for instance by purchasing studies from universities and research institutions assessing the potential for new technology introduction to raise their productivity (Kim et al., 2018).

Rapid technological development entails challenges like cyber-security, which is crucial to ensure trust in economic transactions and well-being. Korea has the second highest share of internet users experiencing privacy violations in the OECD, after Chile (OECD, 2019e) and youth aged 10-29 are at much higher risk of internet or smartphone addiction than other age categories. This calls for reinforcing ICT education at schools and in firms to raise awareness of digital dangers, such as cyberbullying, privacy violation and addiction to ICT technologies.

Figure 1.20. Digital gaps between large and small firms remain high

Percentage of enterprises with ten or more employees using selected digital tools, 2018 or latest year

Note: RFID stands for Radio frequency identification; CRM for Customer relationship management; ERP for Enterprise resource planning.

Source: OECD (2019f); OECD ICT Access and Usage by Businesses Database.

Product market regulations are among the most stringent in the OECD (Figure 1.21). Reducing these regulatory barriers to competition and reallocation, as well as providing easier financing for young innovative firms, can boost the diffusion of digital tools like cloud computing and artificial intelligence and maximise their impact on productivity (Sorbe et al., 2019). A programme to shift the burden of proof from the regulated to the regulator established in 2019 has led to the overhaul of around two thousand regulations. In 2020, the scope of the programme is being expanded, with priority given to areas related to the response to the COVID-19 and other crises. The administration is to be more proactive in reviewing regulations to solve the regulatory difficulties faced by the private sector, conflict resolution is to be improved and the programme is to be expanded to local government and public institutions. Further participation of stakeholders in the programme is to be facilitated. The government has also introduced regulatory sandboxes to allow firms in new technologies and new industries to test their products and business models without being subject to all existing legal requirements. Follow up on this strategy should allow identifying regulation breaches and reviewing regulations, notably in the case of telemedicine.

Figure 1.21. Product market regulations are stringent

Table 1.9. Past recommendations on regulation and support for SMEs and innovation

|

Main recent OECD recommendations |

Action taken since the 2018 Survey or planned |

|---|---|

|

Strengthen product market competition by relaxing barriers to imports and inward foreign direct investment and liberalising product market regulation. |

The government seeks to incentivise foreign investment by revising the Foreign Investment Promotion Act to expand cash grants for high-tech and product investment. |

|

Introduce a comprehensive negative-list regulatory system and allow firms in new technologies and new industries to test their products and business models without being subject to all existing legal requirements (i.e. a regulatory sandbox). |

The government has launched regulatory sandboxes in ICT convergence, industrial convergence, financial innovation and regional innovation since January 2019. In 2019, 195 projects were approved by the regulatory sandbox system. |

|

Increase lending based on firms’ technology by expanding public institutions that provide technological analysis to private lending institutions. |

Lending based on firms’ technology amounted to KRW 205 trillion in 2019, up from KRW 163 trillion for 2018 and from KRW 128 trillion in 2017. The banks plan to improve their capacity to lend based on firms’ technology by securing experts, developing assessment models and enhancing credit rating systems. |

|

Ensure that support provided to SMEs improves their productivity by carefully monitoring their performance and introducing a graduation system. |

The government is monitoring SME support policies and analysing their results to improve their effectiveness and financial efficiency. |

The fight against corruption has been stepped up but challenges remain

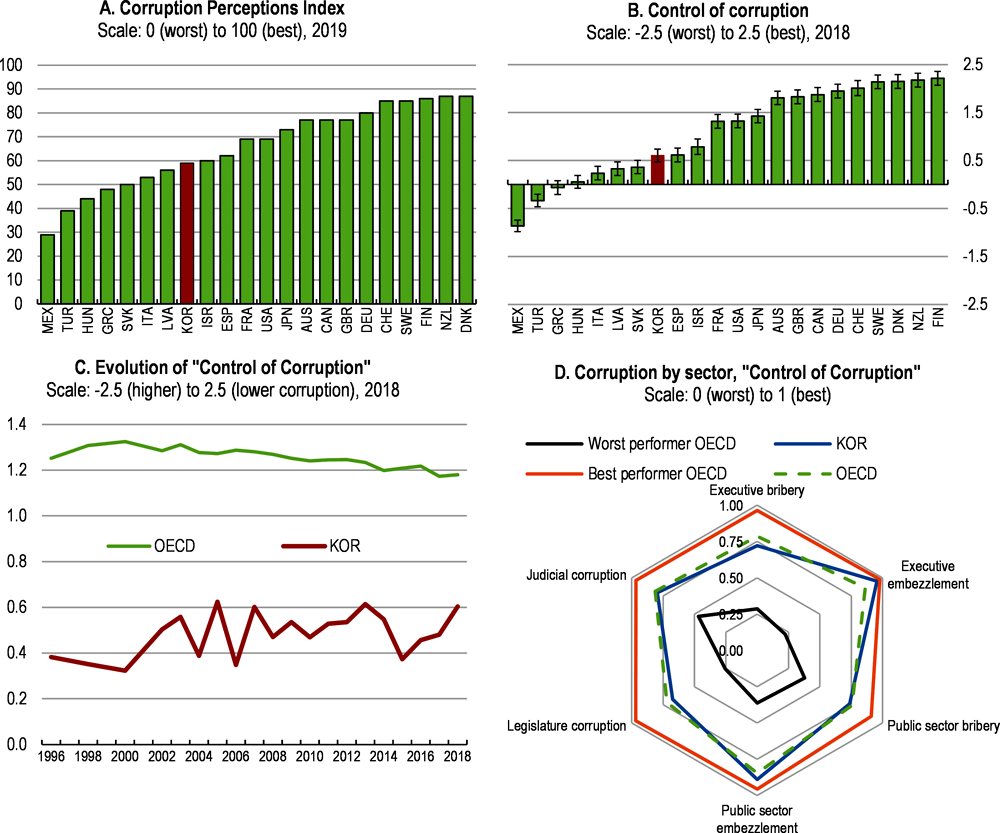

The Korean government has taken significant steps to fight corruption recently. However, corruption still remains in Korean society, with relatively low scores both on the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index and the World Bank Control of corruption indicator, even though both have improved over the past three years (Figure 1.22). Korea’s rankings on the Index of Public Integrity, developed by the European Research Centre for Anti-Corruption and State-Building with support of the European Union, and the TRACE Bribery Risk Matrix, developed by TRACE International in collaboration with the RAND Corporation, have also improved. Corruption of low-level public officials has been almost eradicated, in particular thanks to the establishment of the Korean Independent Commission Against Corruption (KICAC) in 2002, which was integrated in a broader agency, the Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission (ACRC) in 2008.

Figure 1.22. Corruption is perceived as relatively high

Note: Panel B shows the point estimate and the margin of error. Panel D shows sector-based subcomponents of the “Control of Corruption” indicator by the Varieties of Democracy Project.

Source: World Bank; Transparency International; Varieties of Democracy Institute; University of Gothenburg, and University of Notre Dame.

High-level corruption involving politicians and top private company executives remains problematic, as illustrated by a number of high-profile cases in recent years. Also here, significant progress has been made on some issues. An amendment to the Prevention of Corruption and the Establishment and Management of the ACRC, which came into force in October 2019, reinforces the protection of whistleblowers, by severely punishing retaliatory measures (e.g. dismissal). The Public Finance Recovery Act, which came into force on 1st January 2020 aims at recovering illegitimate profits derived from abusive claims for public funds (subsidies, compensation and contributions), which amount to an estimated KRW 214 trillion (about $ 180 billion or 11% of annual GDP). New provisions were added to the Code of Conduct of Public Officials to prevent conflicts of interest. Recently, a number presidential pardons were denied to politicians, business executives or public officials involved in corruption. In late December 2019, the National Assembly passed a bill to set up a special anti-corruption investigation unit tasked with looking into wrongdoing by high-ranking government officials, which includes senior prosecutors, judges and police officers.

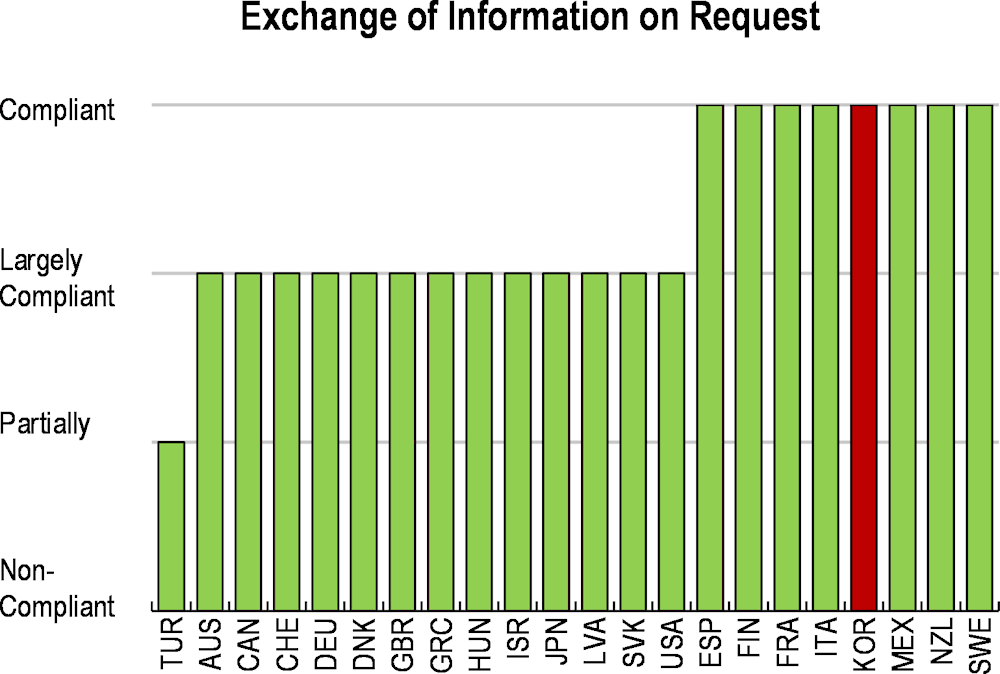

Korea’s OECD Anti-Bribery Convention enforcement record has declined between the 2011 and 2018 assessments. Coordination mechanisms between Korea’s police and prosecutors’ offices and reporting requirements of suspected bribery to relevant law enforcement agencies need to be clarified. Nevertheless, high tax transparency helps fight corruption (Figure 1.23).

Figure 1.23. Korea is compliant on tax transparency

Note: The graph summarises the overall assessment on the exchange of information in practice from peer reviews by the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes. Peer reviews assess member jurisdictions' ability to ensure the transparency of their legal entities and arrangements and to co-operate with other tax administrations in accordance with the internationally agreed standard. The figure shows first-round results; a second round is ongoing.

Source: OECD Secretariat’s own calculation based on the materials from the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes, OECD, and Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

Table 1.10. Past recommendations on corruption

|

Main recent OECD recommendations |

Action taken since the 2018 Survey or planned |

|---|---|

|

Follow through on the government’s pledge to not grant presidential pardons to business executives convicted of corruption. |

Under the Moon Administration, group presidential pardons were granted only twice, and did not concern politicians, business executives or public officials involved in corruption. |

Environmental quality remains low by OECD standards

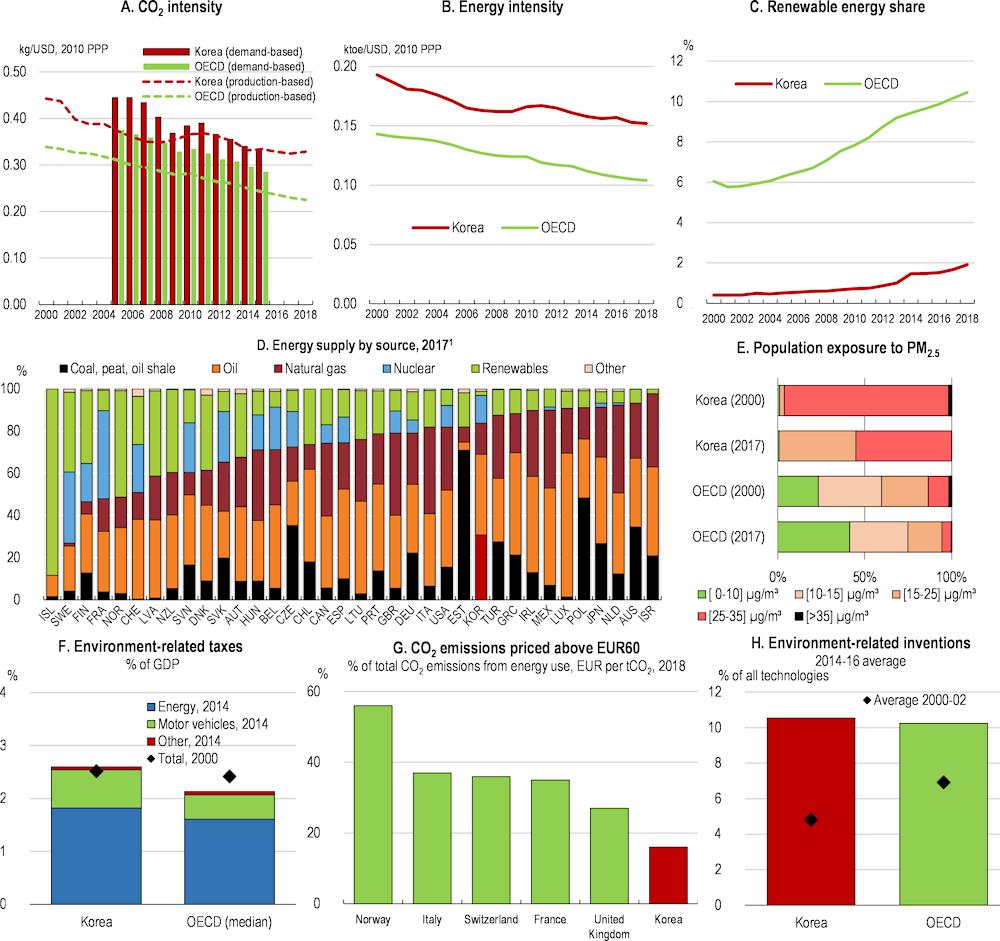

Rapid industrial growth over decades has taken its toll on the environment and a shift towards greener growth is essential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) and improve the population’s living environment, not least air quality (OECD, 2017b). In recent years, CO2 and energy intensity have fallen only slightly, and low oil prices in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis may generate further headwinds to the energy transition. The share of renewables in primary energy supply remains modest (Figure 1.24, Panels A-C). Renewables contribute 8.3% to the country’s electricity generation, one of the lowest shares OECD-wide. Fossil fuels account for 80% of primary energy supply, of which coal represents 31%, more than in most other OECD countries (Panel D). Nuclear accounts for 10.5% of primary energy supply and 23.4% of electricity generation, but is to be phased out by 2083.

Notwithstanding a temporary improvement during the first half of 2020, with the positive effects of the seasonal fine dust control system, favourable weather conditions, and the COVID-19 crisis that depressed activity, most of the population is exposed to small particle air pollution well above the critical threshold of the World Health Organisation (10 µg/m³; Panel E). Small particle concentration in Seoul is about twice the WHO ceiling (Trnka, 2020), raising premature mortality substantially (Roy and Braathen, 2017) and affecting children’s health most (World Health Organization, 2018). Education outcomes for young children attending schools exposed to higher air pollution are substantially and lastingly lower (Heissel et al., 2019). Moreover, air pollution likely worsens the impact of the pandemic (UBC, 2020). About half of the total level of fine particles stem from domestic sources, notably industry, power plants and diesel vehicles. The remainder comes from neighbouring countries. Korea has signed a number of bilateral agreements to address the fine dust issue with China since 1993, which have led in particular to cooperation on demonstration projects, research and information sharing (Jung, 2019; OECD, 2019g). One of the main tasks of Korea’s National Council on Climate and Air Quality (NCCA), an independent body launched in April 2019, is to reinforce cooperation with neighbouring countries to tackle air pollution and climate change. In 2019, air pollution was declared a “social disaster”, which allows the release of emergency funds, and KRW 1.3 trillion (about 0.1% of GDP) extra funding was allocated to anti-pollution measures, in addition to the KRW 2.0 trillion (about 0.1% of GDP) main budget dedicated to anti-pollution measures. Measures include subsidies for replacing old diesel cars and buying air purifiers, as well as support for renewables. Public transport is being developed further, notably in the capital area. The government is implementing additional measures, including shutting down coal power plants, with the aim of reducing locally-generated small particle air pollution (PM2.5) by 35% by 2024 relative to 2016, but sustained efforts will be required to reduce exposure to below the WHO limit.

The government has committed to reducing GHG emissions by 37% relative to business-as-usual by 2030 – equivalent to about 20% relative to the 2010 level. Worldwide, containing global warming will require moving to net zero GHG emissions in the long run (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018). An increasing number of high-income countries, have announced net zero GHG production-based emission targets for 2050 or earlier, including Belgium, Denmark, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Research suggests that reaching net zero emissions, while requiring broad and deep economic transformations, may have modest overall social costs (1-2% of GDP), which would at least in part be offset by well-being gains, in particular from lasting reductions in air pollution (UK Committee on Climate Change, 2019; OECD, 2019h).

Reaching Korea’s emission targets will require substantial policy measures (OECD, 2017b). The strategy will need to tackle a broad range of sectors, including electricity generation, buildings, transport, industry and agriculture. Investment in energy efficiency is also essential to keep costs low (IEA, 2018). Decarbonisation of electricity is key, as switching to electricity in energy end-use is a major way to lower emissions. The government’s pledge not to build new coal power plants is welcome. Four ageing coal power plants were closed recently and six will be closed soon, and others converted to cleaner resources. Phasing out coal altogether by 2030 would be in line with the commitments of countries in the Powering Past Coal Alliance (2017), which argues that ending unabated coal use by 2030 would be a cost-effective way to align policies with the Paris Agreement. The government’s goal is raising the share of renewables in electricity generation from about 8.3% in 2018 to 20% by 2030 and 30-35% by 2040. Part of the fiscal stimulus in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis ought to be oriented towards speeding up the energy transition. This is all the more important insofar as digitalisation may increase electricity consumption.

Figure 1.24. Environmental performance remains weak

1. Data may include provisional figures and estimates.

Source: OECD Green Growth Indicators database, IEA (2018), World energy balances, IEA World Energy Statistics and Balances database.