The rapid internationalisation of the Polish economy has helped develop competitive export-led manufacturing and services sectors fostering robust growth and productivity performance. However, the benefits of this development have been unequal. Many small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), some regions and social groups have lagged behind. Poland’s integration into world trade has largely focussed on downstream activities of value chains and relatively labour-intensive products that incorporate little domestic value added. The coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis has put additional pressures on SMEs. A broad range of well-coordinated policies is required to boost SMEs’ internationalisation and their productivity, while easing labour reallocation during the ongoing recovery. Providing stronger support for training programmes in smaller firms and within small firms’ networks would help them upgrade the skills of their workforce, notably for their managers, and ease new technology adoption and internationalisation. Streamlining regulations on start-ups and limiting regulatory and tax barriers to firm expansion would raise firm entry and growth. Strengthening post-insolvency second chance policies for honest entrepreneurs would ease resource reallocation and the adaptation of SMEs to an uncertain and rapidly changing international environment. Improving transport and digital infrastructure would lower trade costs and raise productivity. Ensuring that innovation policies adapt to smaller firms would boost their innovativeness and ease their integration in national and international value chains.

OECD Economic Surveys: Poland 2020

2. Boosting SMEs’ internationalisation

Abstract

Poland’s internationalisation has been remarkable but unequal

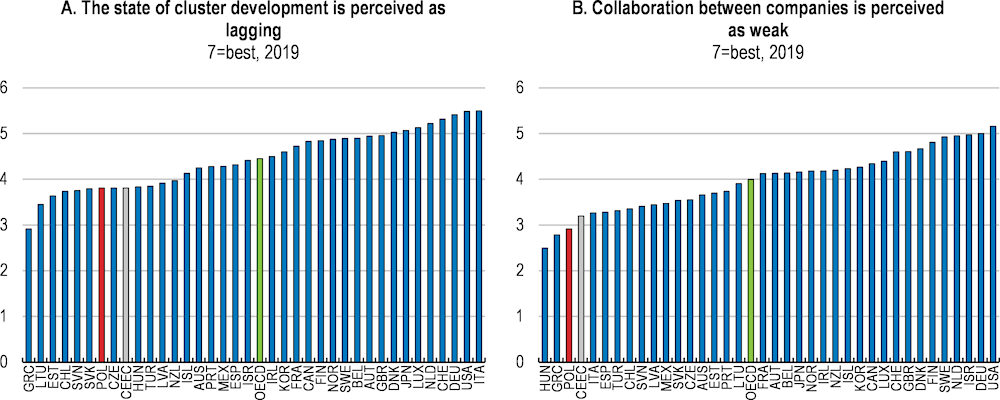

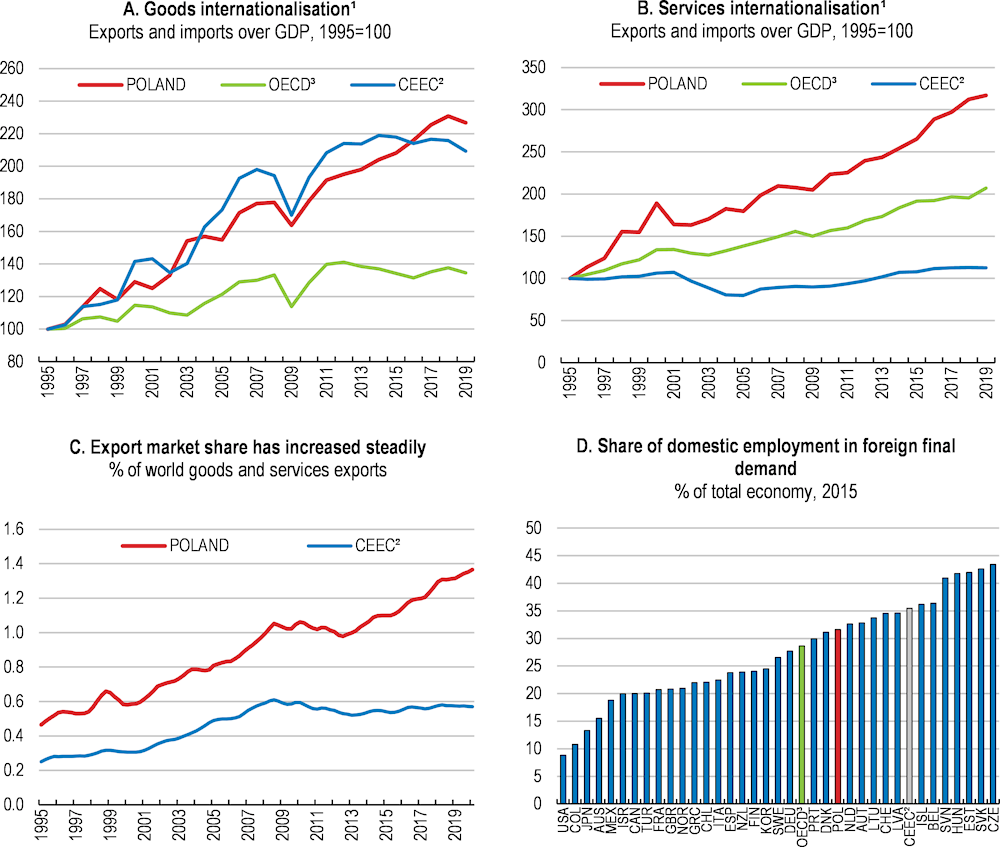

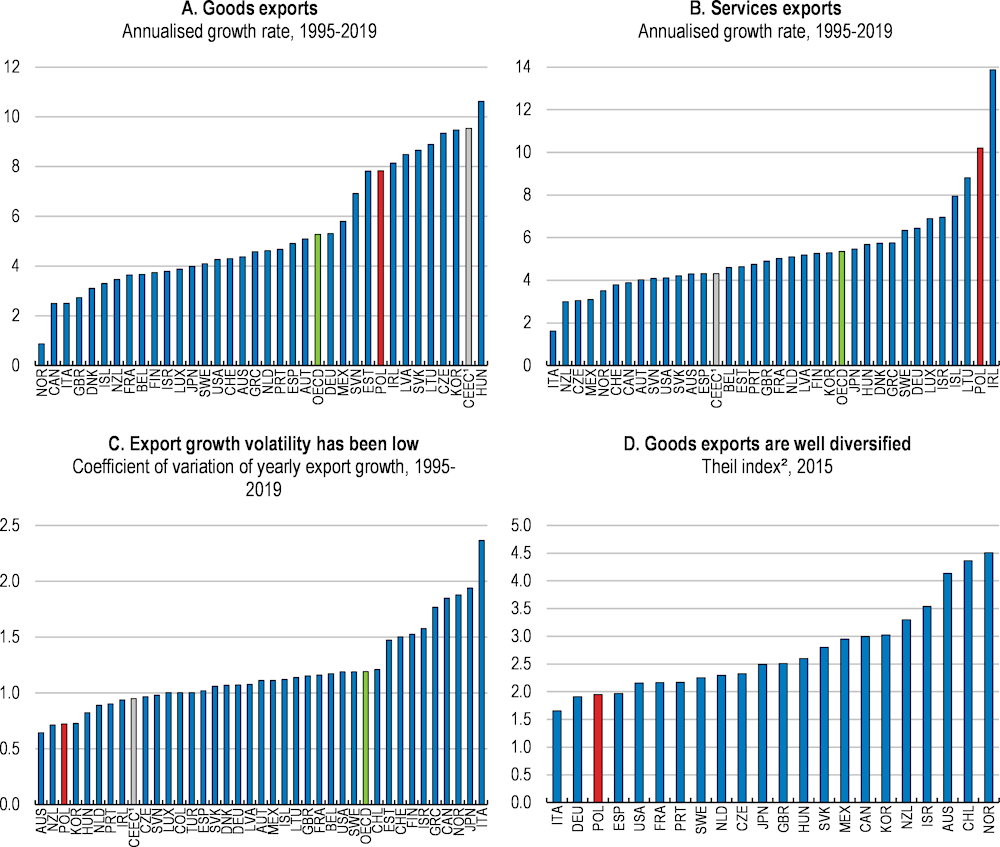

Poland’s internationalisation has been a key driver of growth and income convergence since the transition process. Exports and imports in goods have outpaced GDP growth, notably through large exports and imports of intermediate goods (Eurostat, 2019). Services trade growth was also very strong, unlike in other Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries (Figure 2.1, Panels A and B). Exports of goods and services nearly quadrupled over the last two decades, and, export market share rose twofold. Competitive labour costs, proximity to European markets and the integration to global value chains (GVCs), as well as strong productivity gains explain the major part of the internationalisation and export performance (OECD, 2018a). Even during the 2011-16 global trade slowdown and until the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis, Polish exports had continued to gather significant pace and raise their market share (Panel C). More than 40% of domestic employment nowadays depend on international markets (Panel D).

Figure 2.1. Poland’s internationalisation and export performance have been impressive

1. Internationalisation is proxied by the share of exports and imports divided by GDP.

2. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

3. The OECD average is the unweighted average of OECD countries.

Source: OECD (2020), National account database; OECD (2020) Trade in Employment database.

Poland’s increasing trade openness and integration in GVCs, eased technology transfers and supported employment and productivity gains. During 1995-2011, Poland rapidly integrated into global value chains and received significant inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the manufacturing sector. Foreign affiliates played a key role in this development process and recent OECD estimates suggest that they are still responsible for 40% of GDP (Cadestin et al., 2019). As a result, the South-West of Poland, notably through the automotive sector, saw a rapid rise in GDP and incomes (Box 2.2). Indeed, the domestic sourcing of intermediates by foreign affiliates largely benefitted domestic firms, of which the majority are small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Hagemejer and Kolasa, 2011).

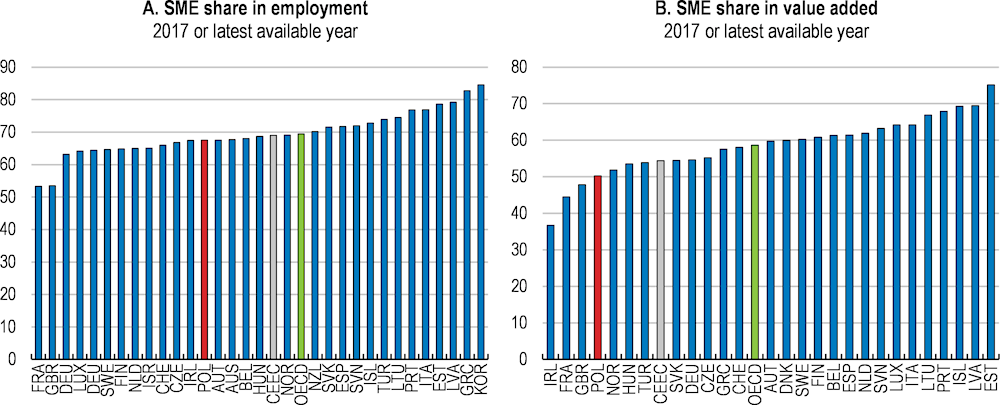

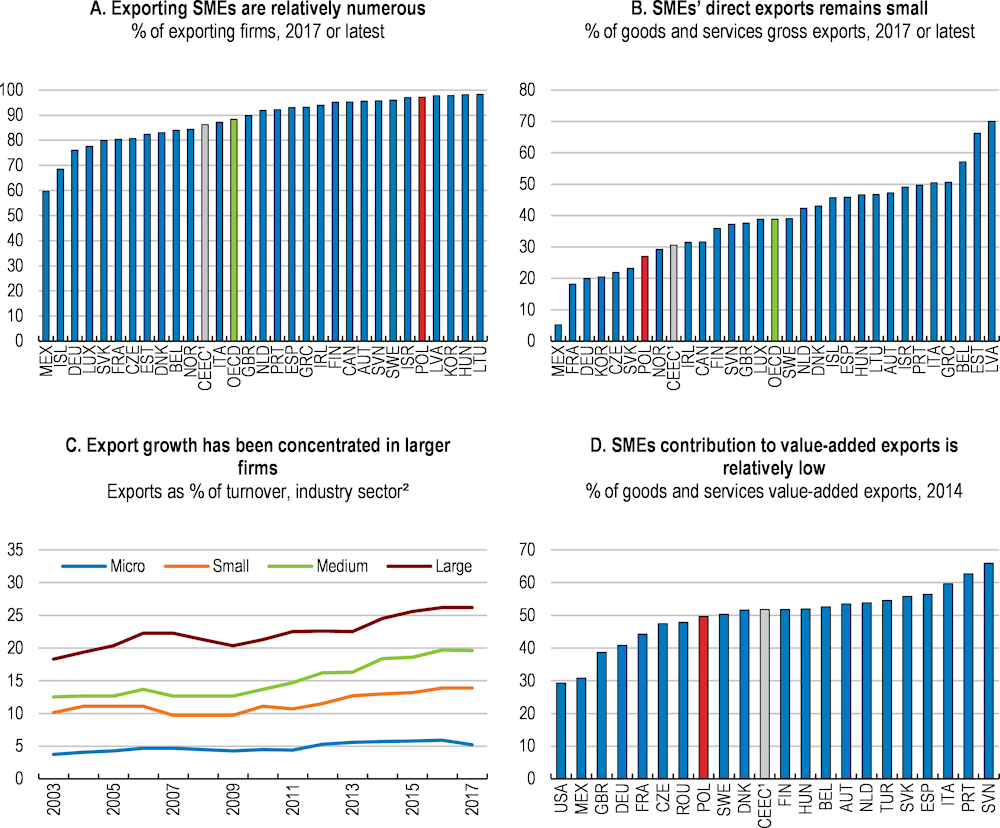

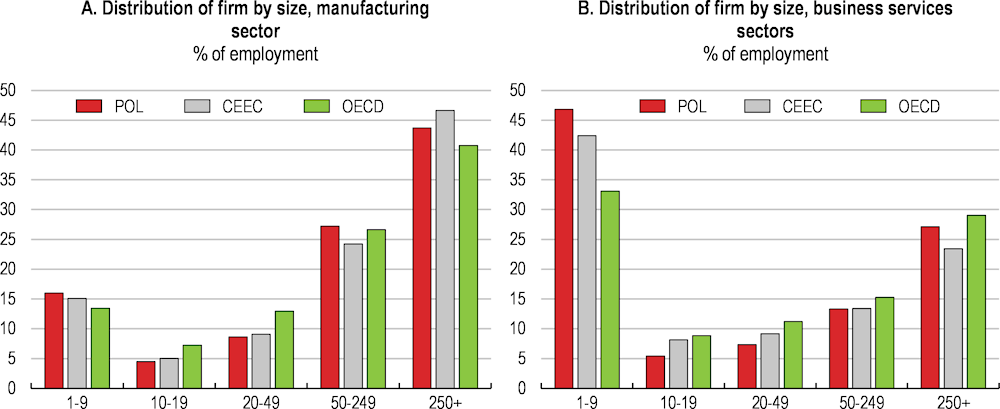

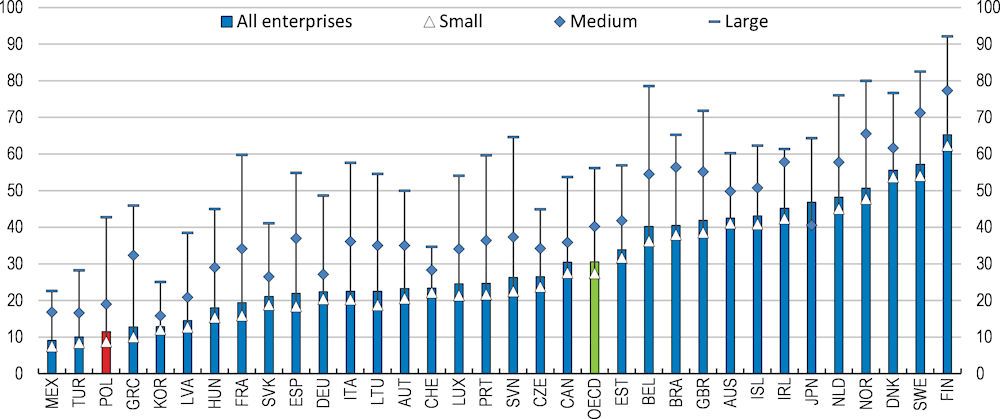

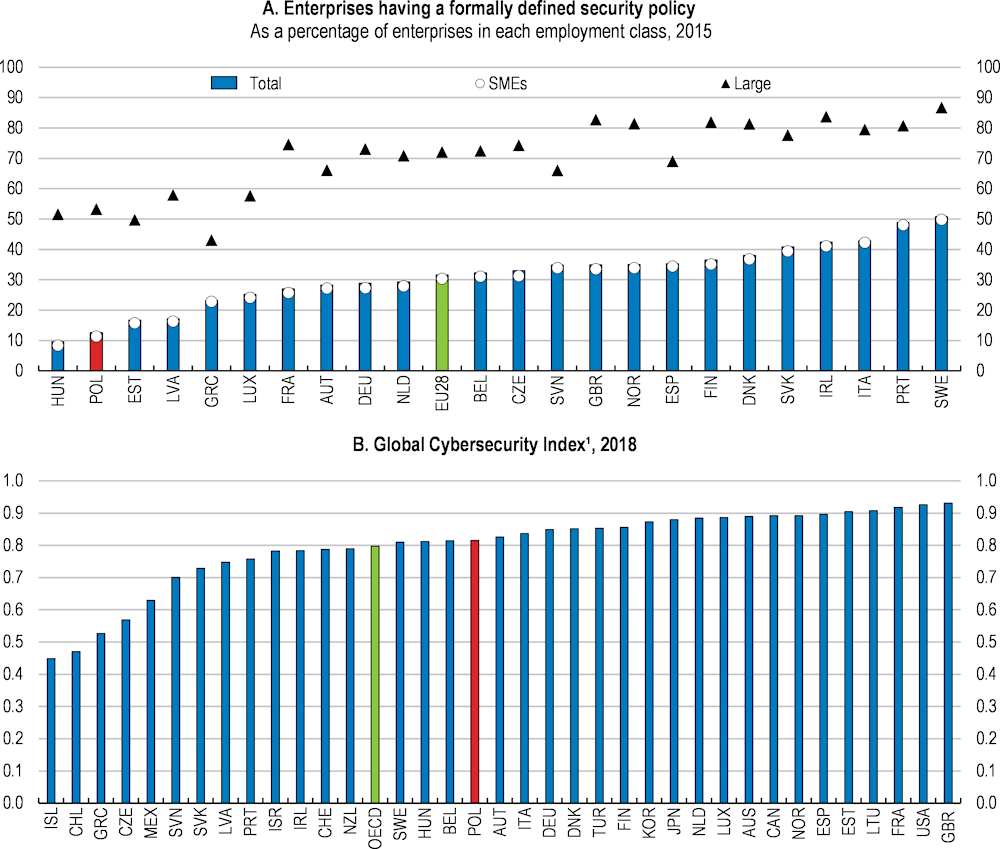

However, the development of SMEs’ linkages with local, national and international networks could be reinforced and support further productivity and well-being gains. Poland’s SMEs account for approximately 70% of persons employed in the business economy and around 51% of value added (Figure 2.2; OECD, 2019a). Yet, their internationalisation has been highly heterogeneous. Though a relatively large number of SMEs export directly (Figure 2.3, Panel A), SMEs still account for only a small share of direct exports (Panel B). They account for around 30% of direct exports, well below their share in employment or value-added. Moreover, most of these direct exports take place through medium-sized firms that, as large firms, saw a steep rise in their export intensity (Panel C).

Figure 2.2. SMEs play a key role in the Economy

Note: All sectors of the business economy are included, except financial and insurance activities. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Source: OECD (2019), Structural Business Statistics.

Poland’s SMEs appear lagging in a number of forms of internationalisation. The share of SMEs in value-added exports is higher as SMEs export indirectly through upstream linkages with larger exporters, but the importance of SMEs for value-added export remains below the average level of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics, or those of Italy, Portugal and Spain (Figure 2.3, Panel D). Indeed around 60% of SMEs’ indirect exports reach foreign markets via large enterprises, the remaining 40% via other SMEs (OECD, 2018b). When they export directly, SMEs are more often occasional than persistent exporters and they export to closer markets (EC, 2018a; 2018b). SMEs engage less in imports of goods and services or may seek foreign suppliers, which could help them gain access to more sophisticated and competitively priced intermediates to enable productivity gains and upscale or upgrade production (López González and Sorescu, 2019). SMEs are also less likely to be the recipients of foreign direct investment (inward FDI) or to invest abroad (outward FDI).

This unequal internationalisation left behind some places that have high proportions of vulnerable people and low levels of economic activity. As in other OECD countries, exporting and foreign capital have been associated with faster productivity growth at the sector level, and internationalised firms, both through exporting and foreign direct investment, have performed better than non-internationalised firms (Szpunar and Hagemejer, 2018). This compounded the problems of lagging firms and regions, as long-term unemployment, poverty, and poor health and low social mobility often go hand in hand (OECD, 2019b).

Figure 2.3. SMEs internationalisation has been heterogeneous

1. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

2. For micro firms, exports over turnover is backcasted based on small firms over 2003-2009.

Source: OECD (2019), Structural Business Statistics, Trade by Enterprises Characteristics and National account databases; OECD (2018), “Accounting for firm heterogeneity in global value chains: The role of Small and Medium sized Enterprises”, OECD Working Party on International Trade in Goods and Trade in Services Statistics, OECD publishing, Paris; OECD caclulations based on PARP (2019), Raport o stanie sektora małych i średnich przedsiębiorstw w Polsce, Polska Agencja Rozwoju Przedsiębiorczości, Warsaw and Ministry of Economic Development, Labour and Technology "Entrepreneurship in Poland" 2010 and 2011 reports.

The global coronavirus pandemic had a large initial impact on Polish trade and vulnerable groups and regions were disproportionally affected (Box 2.1). At the same time, some well-internationalised sectors such as the automotive and transport industry have been hard hit. Stalling global investment has seen demand for capital goods plunge, in particular for cars. As during other crises, the internationalisation of firms appears to have played a role in the propagation of economic shocks, but they also seem to have helped firms to recover faster (OECD, 2020gvc). Following the initial coronavirus shock, Poland’s trade bounced-back over the summer 2020. From 2019Q4 to 2020Q2, Poland’s exports and imports of goods and services appear to have been more resilient than in many other European countries. Yet, in 2020Q2, exports and imports remained well below their 2019Q4 levels.

In response to long-standing issues that have been stressed in the 2017 Strategy for Responsible Development, the authorities have undertaken reforms to ease administrative business and trade procedures and increase R&D and innovation activities, as well as to reach a more even territorial development (Box 2.2 and Box 2.3). The authorities have also put in place extensive support measures that helped to cushion the initial coronavirus shock (Box 2.1). Yet, further efforts to ease resource reallocation while maintaining viable firms will also be required to deal with renewed challenges.

This chapter analyses how Poland’s internationalisation and the digital transformation offer new opportunities for SMEs to integrate directly and indirectly into the global economy, raise their productivity and grow. It then looks at how policies can create the best policy environment to help SMEs – and the many people they employ – to take advantage of these opportunities.

Box 2.1. The global (COVID-19) pandemic and its effects on international trade and SMEs

SMEs have suffered heavily from the crisis

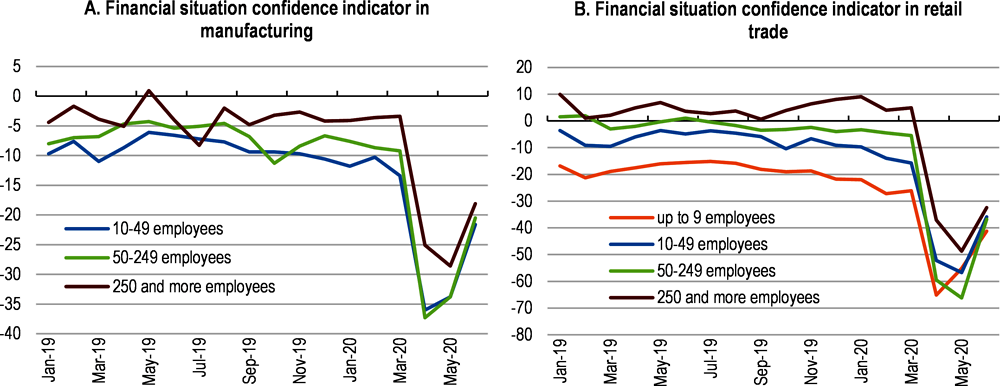

Government lockdowns and border closure have affected the supply of domestic and foreign goods and services, and trade plummeted between March and May 2020. Though Poland’s exports and trade have been relatively resilient (OECD, 2020), early business surveys and employment data point that Polish SMEs and regions that had the weakest business dynamics are among the most affected by the crisis (Figure 2.4 and 1.6).

Figure 2.4. SMEs have been hard hit by the coronavirus crisis

Source: Statistics Poland (2020), Business tendency in manufacturing, construction, trade and services, 2000-2020, June 2020 update.

The initial coronavirus shock also hit hard SMEs and regions that were well integrated in GVCs. Demand for cars has plunged over 2020 and is projected to recover only partially in 2021 (OECD, 2020d). Given the weight of the automotive industry in Polish exports, the crisis and the high uncertainty around future demand for cars, will put this industry and its suppliers under severe strain. The crisis, therefore, adds to the existing challenges facing the car manufacturing industry, such as changes in mobility patterns.

Policy responses

The Polish government took a series of early measures to limit the impact of the coronavirus crisis on SMEs. It increased their liquidity by announcing that micro enterprises (with less than 10 employees) experiencing a 50% drop in revenues would be exempted from social security contributions for three months, provided that their revenues in March would not exceed 300% of the average wage. Later, a 50% reduction was extended to small firms with less than 50 employees and revenues requirement dropped. It also eased their financing through an unprecedented loan scheme of PLN 100 billion launched in early April (Box 1.1) that was mainly targeted at SMEs, with ¾ of the funds dedicated to such firms and only ¼ available to large enterprises. Micro firms could receive up to PLN 324,000 and small and medium companies up to PLN 3.5 million each. The latest “anti-crisis package” established that micro loans of up to PLN 5,000, mostly concerning micro and small firms, would no longer need to be reimbursed as long as companies continued to operate for three months after the grant. It also suspended the statutory time limit to file for bankruptcy for firms affected by the coronavirus crisis and introduced new simplified restructuring procedures for all firms, which notably include a 4-month automatic stay on assets and out-of-court recovery proceedings, until 30 June 2021.

Source: OECD (2020), OECD Economic Outlook – June 2020, OECD publishing, Paris.

A bird’s eye view of Poland’s internationalisation and SMEs’ landscape

Polish exports concentrate on medium and low-tech goods

Polish exports are well diversified in terms of composition. The agricultural sector, auto parts industry, and aviation and shipbuilding sectors have well-developed exports (Figure 2.4). A wide range of other exporting industries includes cosmetics, furniture, machinery, minerals, plastics and textiles, as well as services (Figure 2.5). This diversified structure has helped to cushion disruptive shocks. Until the coronavirus crisis, sharp contractions in final demand, which happened due to the concentrated exposure to cyclical industries in Slovakia and Hungary in 2009, had not been observed in Poland that tend to exports more consumer goods that are less sensitive to the global economic cycle than other CEE countries. During the 2018-19 global slowdown, Polish exports had continued to grow strongly, supported by renewed FDI inflows.

Figure 2.5. Polish exports have been robust, and well diversified

1. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

2. Higher values of the index indicate higher concentration of export products. The Theil index is computed over export values in a 6-digit good classification (HS6 1992 classification) with 5,039 products per year.

Source: OECD (2020), National account database; OECD calculations based on CEPII (2019), BACI Database.

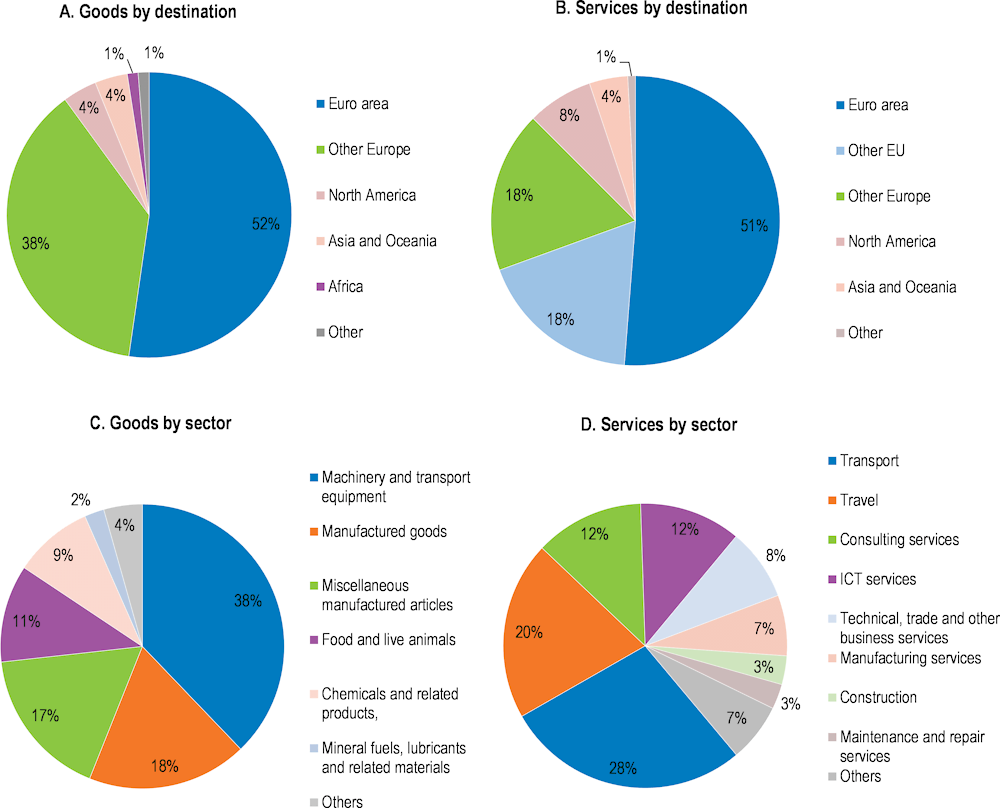

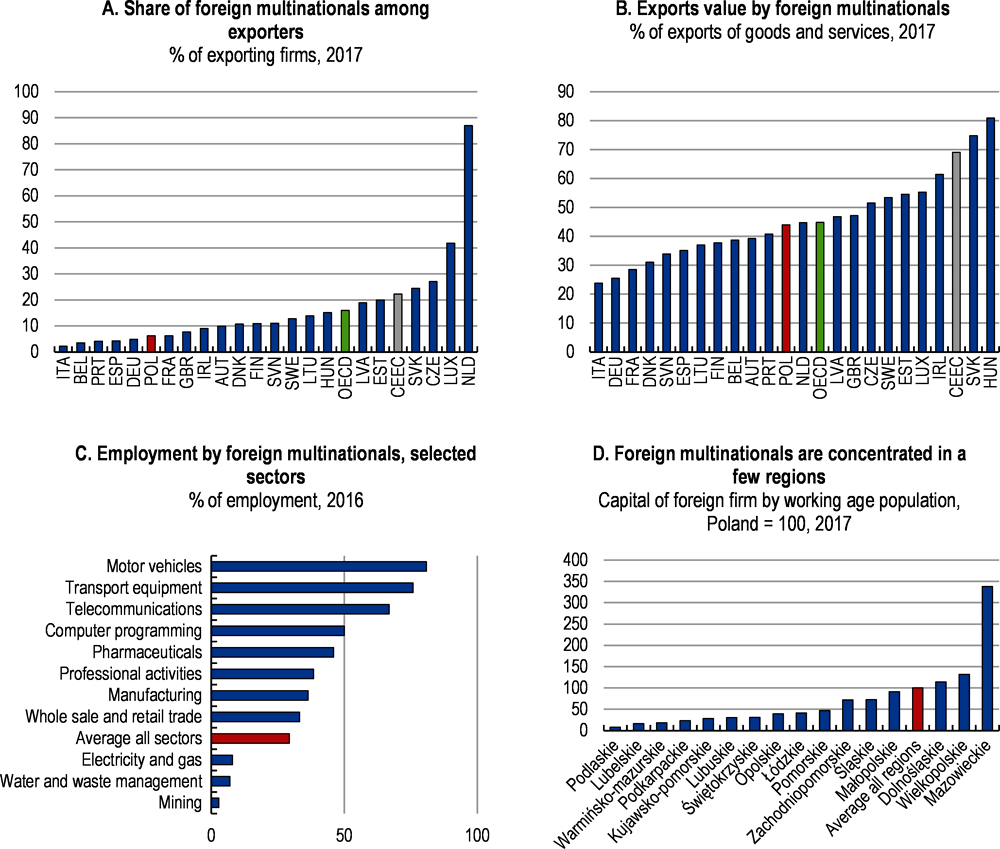

As in other OECD countries, foreign multinationals play a key role in internationalisation (Cadestin et al., 2018). Poland’s location next to Germany; the availability of a low-cost but skilled labour force; its European union membership since 2004; all combined with an historically cautious budgetary and financial policy, have preserved a stable economic and social environment and strong competitiveness. Inward FDI, as a share of GDP, have increased. Foreign investments have a well-diversified industry structure, though they are mostly concentrated in the capital region and the south-west of the country (Box 2.2). Thanks to these FDI inflows, mainly from the European Union (particularly from the Netherlands and Germany), Poland has become a significant exporter mainly through its integration into European GVC. For example, over 90% of automotive production in Poland is exported to Europe (mainly to Germany).

Multinationals supported the growth of services sectors. Jobs outsourced in business services (business processing, IT, and R&D) have nearly tripled over the past decade. Most of the growth has come from international companies’ service centres that tend to be subsidiaries of the foreign companies using them (Box 2.2; McKinsey, 2015). In recent years, Poland also strengthened its position as a regional centre of logistics services, notably through importing consumer goods, such as clothing, footwear or electronics, from third countries into the EU, repackaging them in Polish warehouses and further distributing them to other European Union countries (Mroczek, 2019). The share of services in exports has increased rapidly from 16% in 1990 to more than 21% in 2018, but it remained below the OECD average of 30% in 2018.

Figure 2.6. The structure of Polish exports

Share of exports by sector and destination, 2019 or latest year available

Note: Data on good exports refer to 2019, while data on services exports refer to 2018. In Panel C, Others include crude materials, beverages and tobacco, animal and vegetable oils, and commodities and transactions. In Panel D, Others include R&D services, financial services, insurance and pension, construction services, and cultural services.

Source: OECD (2020), International trade Statistics.

Box 2.2. The role of multinational enterprises in Polish exports and domestic value chains

Foreign firms play an important role in the Polish economy; they are responsible for around 30% of employment and around 44% of exports (Figure 2.7). The industries where foreign-owned firms produce more of the value added are often those that have a higher export orientation. On average, foreign-owned firms in Poland are twice as export intensive (share of exports in turnover) as domestically owned firms, and their export intensity is higher than the OECD median (OECD, 2017).The manufacturing sector highlights this point, with a high share of value added by foreign-owned firms and a high export orientation. In the manufacturing sector, foreign MNEs’ exports reach 65%. In particular, in motor vehicles, foreign-owned firms account for 80% of employment and 90% of exports in value-added terms.

Figure 2.7. Foreign multinationals and exports are tightly linked

Note: CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Source: OECD (2019), MNE database, Inward activity of multinationals and TEC database; Statistics Poland (2019), Entities with foreign capital participation.

Foreign owned capital is concentrated in large firms, with a higher import content of exports and simultaneously relatively large upstream consequences, notably on smaller firms that act as supplier and indirect exporters. In Poland as in other OECD countries, domestic SMEs are the most important domestic suppliers to foreign affiliates (Cadestin et al., 2019).

Source: Cadestin, C., et al. (2019), "Multinational enterprises in domestic value chains", OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 63, OECD Publishing, Paris; OECD (2017), “Trade and investment in Poland”, International trade, foreign direct investment and global value chains, OECD Publishing, Paris.

This increasing involvement in world trade has generated significant benefits. It has acted as a driving force for the economy, and this has been reflected in the strength of exports and the creation of value added from foreign demand since 1995. The sectors that are the most integrated into GVCs, and therefore the most export-focused, have developed comparative advantages, which have led to productivity gains that are stronger than in other sectors and other OECD countries (Miroudot and Cadestin, 2017; Berthou et al., 2015).

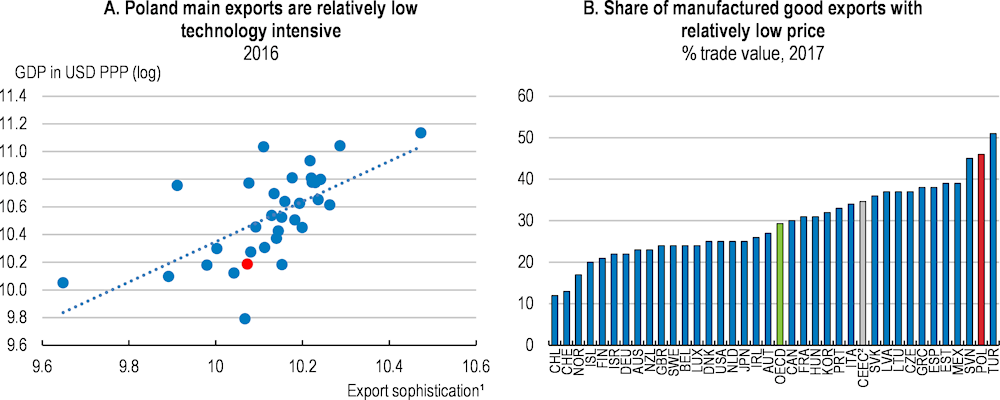

However, exports remained somehow specialised in relatively low-technology goods in 2017. The share of medium and high technology goods in Poland’s export basket has doubled since 1995 (PARP, 2019a), but goods exports remain relatively less sophisticated than those of other CEE countries. Compared to Poland’s level of development, its exports structure is tilted towards goods generally exported by lower-income countries (Figure 2.8, Panel A, Hausmann et al., 2007). Poland’s exports’ prices and quality, as proxied by trade unit values within narrowly defined type of goods, appears relatively low in the manufacturing sector (Panel B), which reflects a perceived specialisation in low-cost and low-quality goods (WEF, 2019). Original equipment manufacturers which operate globally still run largely labour-intensive and low value added production processes in Poland, and export few high-technology products. Poland’s manufacturing exports are in the mature phase of their life cycle compared to many other OECD countries (Araujo et al., 2018), increasing the importance of innovation to sustain the future export performance of the economy.

Figure 2.8. Poland is specialised in low- and medium-tech exports

1. Export sophistication is defined as an average over exported goods as in Hausmann et al., (2007). For each good, a proxy for its sophistication is the average GDP per capita (in 2015 in PPP terms) of its destination markets. Computations use 180 destination countries and 6-digit good classification (1992 - HS6 classification).

2. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Source: OECD (2019), National Accounts Database. OECD calculations based on CEPII (2017), BACI Database and World Bank (2017), World Development Indicators; Comtrade Database; CEPII (2019), The Trade Unit Value Database.

Small size and low productivity hinder SME internationalisation

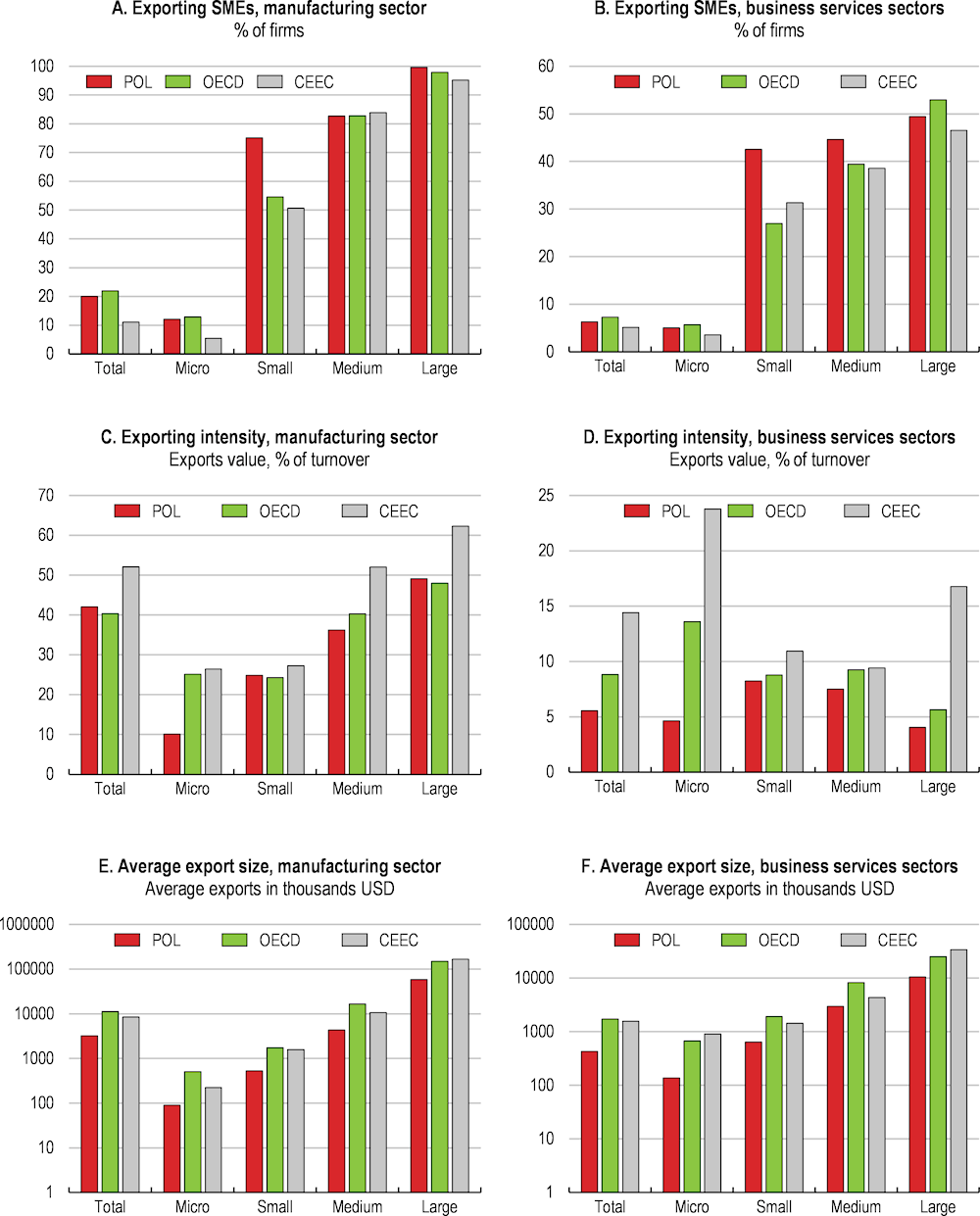

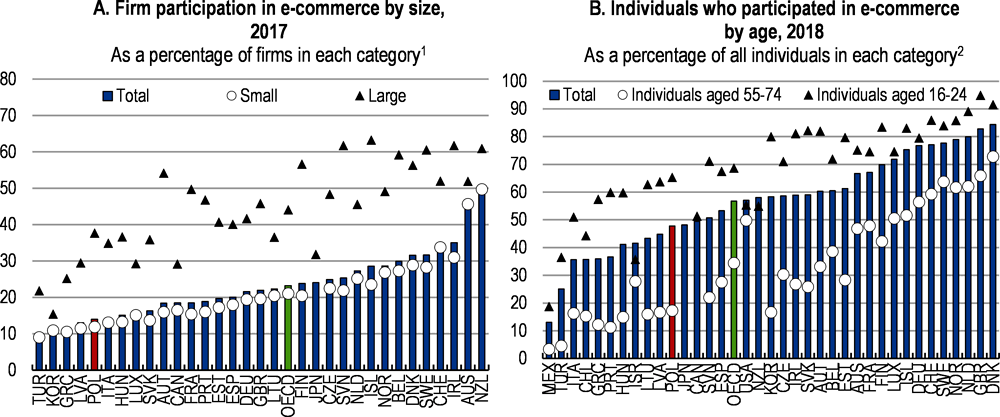

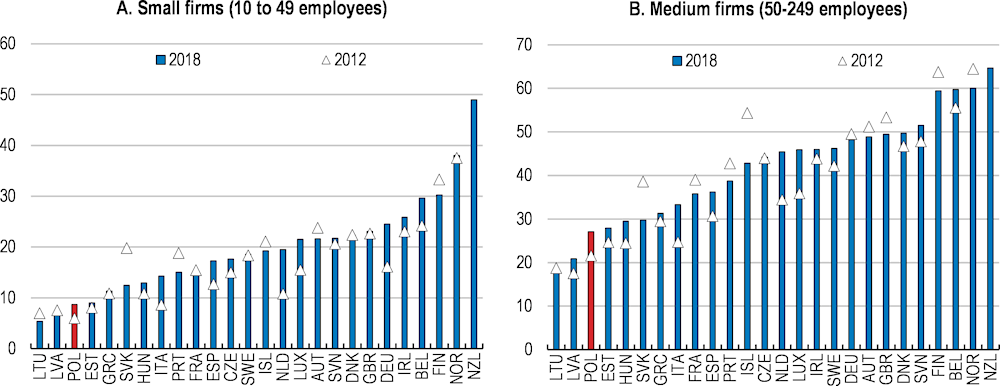

Internationalisation varies significantly by firm size and across sectors. The share of SMEs participating in direct exports is particularly low, notably for micro-firms. According to 2017 data, only about 12% of micro-firms participate in direct export activities in the manufacturing sector and less than 5% in key services sectors (Figure 2.9, Panels A and B). Moreover, their export intensity is relatively low and the average export value per exporting firm are smaller than in the average OECD country and other CEE countries (Panels C and F). The average exports of a Polish exporting firm are roughly 70% smaller in value terms than those of exporting firms in the average OECD country, though the gap varies from 80% for micro-firms to 60% for large firms. This suggests that beyond fixed costs and the participation in global trade, lower productivity and higher variable costs play a key role in explaining the export gap of Polish SMEs.

As in other OECD countries, only a few high-performing firms have become successful exporters. Exporters tend to be larger than non-exporting firms, more capital intensive and more productive (Albinowski et al., 2016; Szpunar and Hagemejer, 2018). The academic literature has traced this back to the existence of fixed costs of entering foreign markets, which only the most productive firms can recover once they become exporters (Melitz and Ottaviano, 2008). The geographical position of Poland is particularly favourable for potential exporters and firm internationalisation, as they benefit from rich neighbouring countries and enhanced access to markets through the European single market which reduces transaction costs. Yet, there remain barriers to cross-border activity hindering the European Single Market (Caldera Sánchez, 2018). And, as in other CEE countries, some fixed costs, such as the need to collect information about export markets, establishing commercial contacts, hiring multilingual staff or adapting products to be sold abroad, remain particularly binding for smaller firms (Morales et al., 2014).

Smaller firms face difficulties in becoming persistent exporters and scaling up their exports, which appears to be key drivers of productivity gains linked to internationalisation (Anderson and Löof, 2009). The costs of adjusting products and company procedures to differences in culture, laws and technology of foreign buyers are relatively higher. Moreover, uncertainty in export relationships is generally high, notably in services sectors, because of the difficulty to enforce contracts across borders and the information asymmetry and geographical distance between the exchange partners. The complexity of firm’s operations tend to increase with the number of product-destination couples exported (Guillou and Treibich, 2019). This also holds for exchange rate movements and their volatility that affect mostly smaller exporters in Poland (Albinowski et al., 2016).

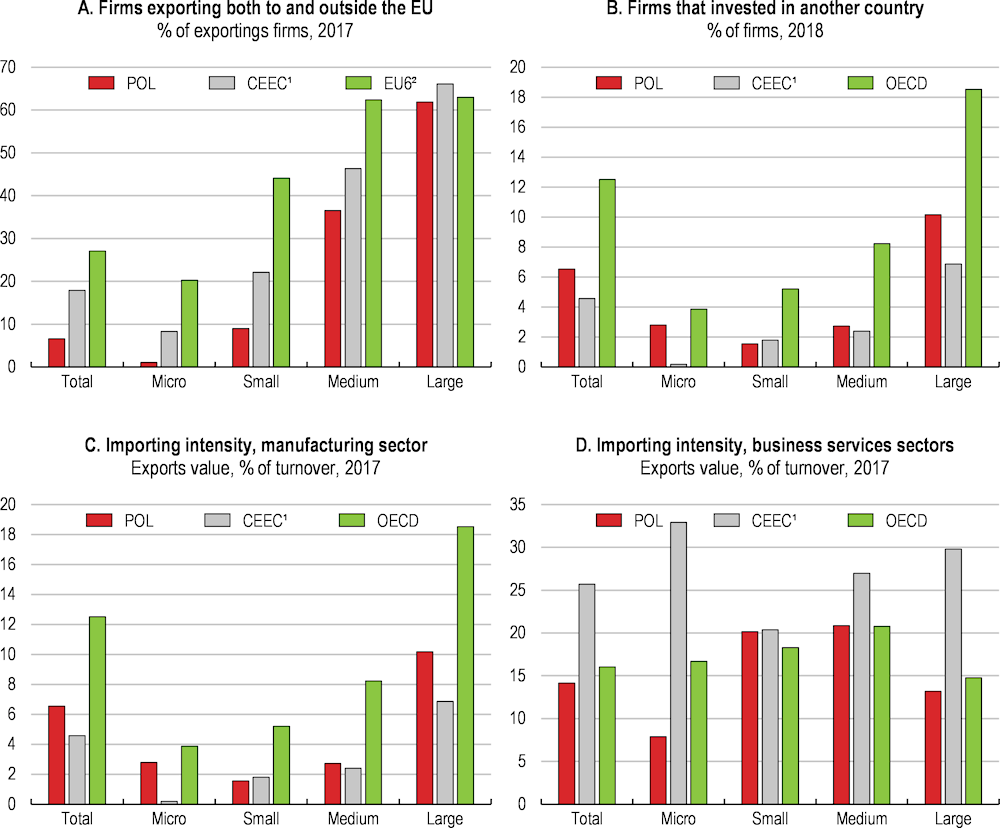

Poland’s SMEs are lagging other forms of internationalisation. When they engage in direct exports they tend to focus on the EU market or other trading partners, but rarely combine both export destinations contrary to larger firms and comparable firms in CEE countries (Figure 2.10). Selling goods and services through foreign affiliates is also less frequent in Poland. Moreover, Poland’s SMEs appear less engaged in imports than SMEs in other OECD Countries. Micro-firms have an importing intensity, as measured as the ratio of imports over turnover, twice below the OECD average, both in manufacturing and services sectors, and much smaller than that of larger firms. Poland’s SMEs, in addition to facing barriers to export, have difficulties in overcoming some of the costs associated with importing – and integrating in GVCs – such as finding reliable suppliers and ensuring that the imported products have the right specifications.

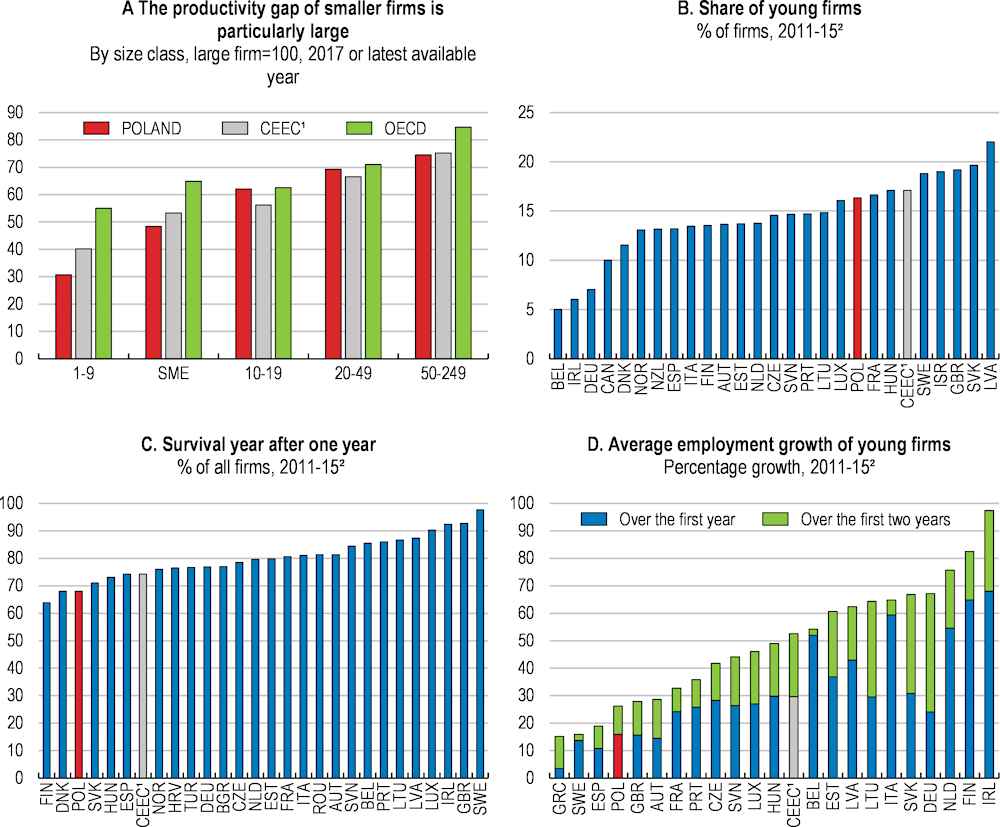

The lagging internationalisation of SMEs reflects their weak productivity and small size. Polish SMEs have relatively low productivity, notably the numerous micro-enterprises, according to 2017 data. Their relative productivity is among the lowest in the OECD (Figure 2.11). Indeed, micro-enterprises account for a high share of employment in Poland compared to the OECD average and other CEE countries, in the services and manufacturing sectors (Figure 2.12). Before the coronavirus crisis, a plethora of start-ups experienced significant difficulties to survive and grow, despite a dynamic economy and the crisis legacy will compound these difficulties. The firm size distribution implies that a large share of firms face relatively higher costs and challenges than larger exporters due to their lower human resources and capital. These firms are disproportionally affected by barriers such as tariffs, quotas and stringent rules of origin, as applied in the whole European Union, due to fixed compliance costs that do not vary with the amount traded and the inability of SMEs to spread these costs over large export values (Rouzet et al., 2017).

Figure 2.9. Smaller firms have low export intensity in manufacturing and services sectors

2017

Note: CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics. Business services sectors include wholesale and retail trade, transportation and storage, information and communication, professional, scientific and technical activities and administrative and support service activities.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2019), Structural Business Statistics, Trade by Enterprises Characteristics and National account databases.

Figure 2.10. Micro-firms lag multiple forms of internationalisation

1. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

2. EU6 is the average of Denmark, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal and Spain.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2019), Structural Business Statistics, Trade by Enterprises Characteristics and National account databases; EIB (2019), EIB Investment Survey.

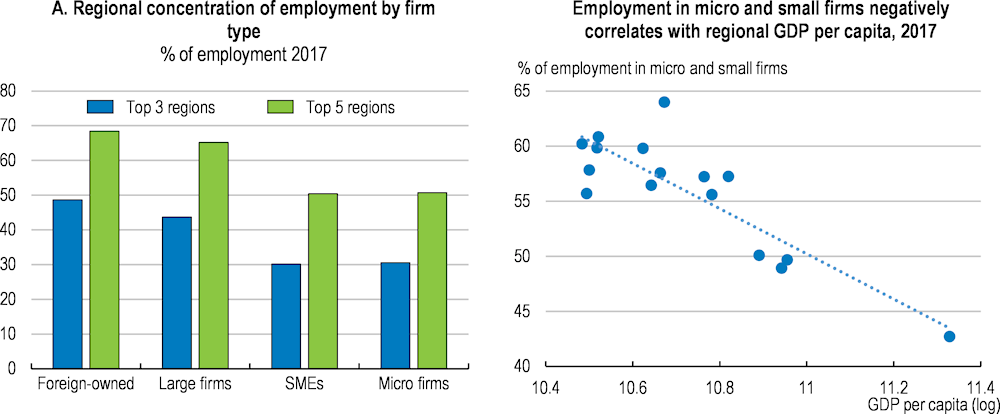

The internationalisation and productivity gaps of smaller firms have large social and territorial implications. For example, micro firms pay on average salary that are only 50% the one of large firms (Statistics Poland, 2019). SMEs’ employees have also lower employment opportunities, lower quality job and low training opportunities (see below). This also contributes to strong regional divides. Widely internationalised large and foreign-owned firms concentrate more than two thirds of their employment in 5 of the 16 Polish regions, while SMEs are more equally spread (Figure 2.13, Panel A). In particular, the share of micro and small firms in employment is strongly negatively associated with GDP per capita at the regional level (Panel B).

Figure 2.11. SMEs productivity is weak and young firms lack opportunities to grow

1. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

2. Average of available years. Young firms are those less than two years old.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2019), Structural Business Statistics, Trade by Enterprises Characteristics and National account databases; Eurostat (2019), “Structural Business Statistics”, Eurostat Database.

Figure 2.12. Micro-firms account for a high share of employment

By size class, 2017

Note: CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2019), Structural Business Statistics.

Figure 2.13. SMEs’ gaps have significant economic and social consequences

Note: Regions correspond to Poland’s 16 regions (voivodeships).

Source: OECD calculations based on Statistics Poland (2019), regional accounts and non-financial entities database.

Boosting SMEs’ internationalisation through a better business environment

Policies that promote activities in which firms and workers are particularly competitive and that foster business dynamism and ease linkages between large exporters and smaller firms would help reap additional gains from trade (OECD, 2017a). Lowering the administrative burden that weighs especially on smaller and younger firms would reduce entry and fixed costs of participating in global trade. A broader firm internationalisation would result in greater diffusion of knowledge, technology and know-how, with positive effects on employment and labour market inclusiveness (Gal and Theising, 2015; Causa et al. 2016).

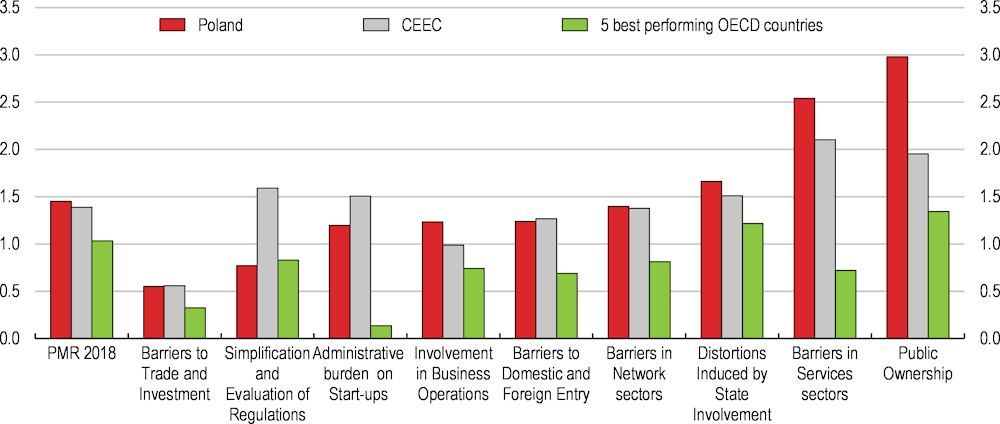

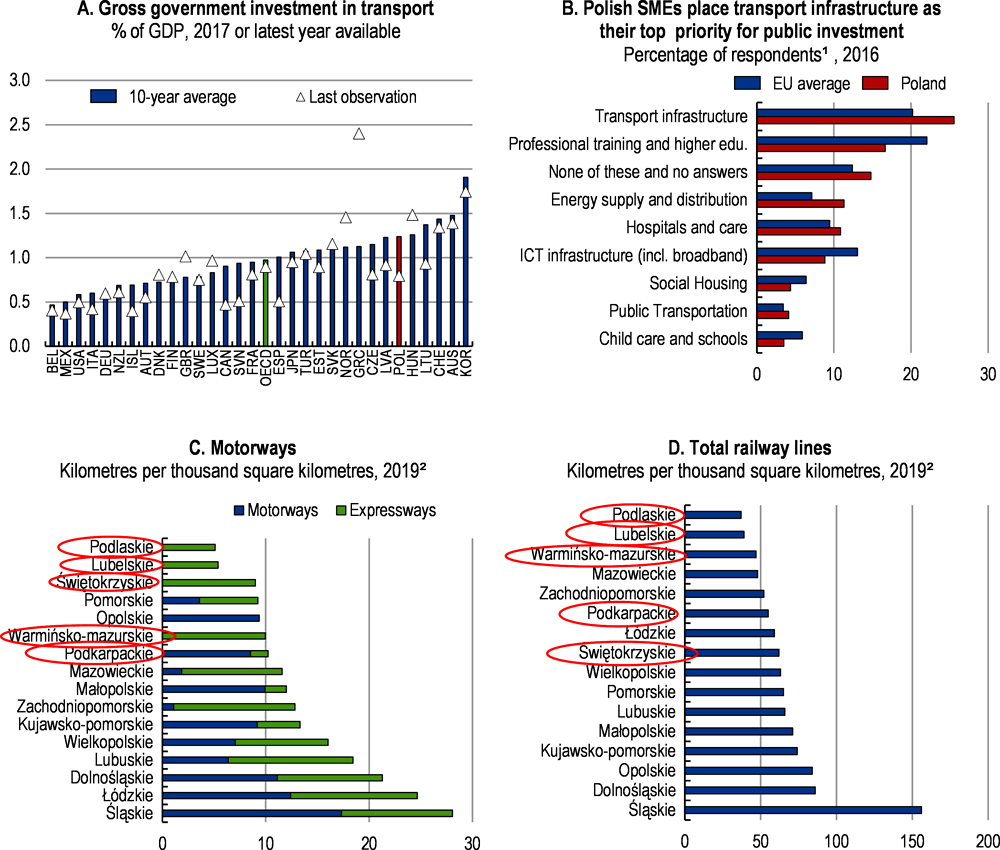

Easing further administrative costs for potential exporters

Improvement in product market regulation has been significant over the last decades, but several aspects of the business environment continue to harm SMEs performance, productivity and internationalisation (Figure 2.14). The authorities have recently implemented measures to ease business creation and growth, notably, lower administrative requirements for new and smaller firms and the possibility of a simplified joint stock company with low capital requirements to facilitate start-ups (Box 2.3 and Box 2.4). The measures also foresee more legal certainty for firms when it comes to paying taxes and audits, and a reduction of paperwork.

Despite these reforms, some administrative and regulatory procedures remain burdensome. In particular administrative requirements necessary to set up new firms, whether limited liability companies or personally owned enterprises, remained relatively burdensome in 2018-19. A large number of procedures have to be fulfilled (OECD, 2019c; World bank, 2019) and some related regulations could be streamlined. For example, in the Podkarpackie and Lubelskie regions (voivodeships), in 2017-18, more than five food inspection services had responsibilities to enforce food requirements, with little standardisation and coordination, which was significantly increasing compliance costs (Drozd et al., 2018).

Streamlining court proceedings could facilitate contract and payment enforcements, particularly important for SMEs and services, and raise productivity growth by shortening bankruptcy procedures. This would help to face the expected wave of insolvent firms when the government starts to withdraw if the recovery remains weak. Before the crisis, it took about three months more than the OECD average for a typical case, with substantial variations across cities leading to high uncertainty (World Bank, 2019). Courts and judges were often overburdened by small, non-litigious cases and the take-up of e-technologies had been low, despite high judicial spending and the 2015 reform easing ICT use for civil proceedings (CEPEJ, 2016; World Bank, 2013 and 2016). Moreover, bankruptcy procedures remained lengthy (OECD, 2018a).

Ensuring that sound firms are given a fair chance to survive the coronavirus crisis and that there is not a proliferation of ‘zombie’ firms and misallocation of resources is key to the recovery. This should be addressed in three phases (OECD, 2020a): i) preventing sound firms from entering insolvency proceedings, ii) ensuring insolvency regimes and other policies can deal with the wave of insolvencies, and iii) policies to address the debt overhang problem to enable a “fresh start” for individuals and firms. Poland took early action to avoid premature liquidations, create a breathing space for firms facing difficulties and ease procedures (Box 2.1). Yet, to prepare for the recovery, developing special insolvency procedures for SMEs, such as simplified or pre-packaged in-court proceedings or the possibility to have instalments in the payment of administrative expenses related to the insolvency proceedings, is also warranted, as SMEs are frequently unable to cover the costs of formal insolvency proceedings (Adalet McGowan et al., 2017). Moreover, limiting in the short and longer term, the burden of non-litigious cases on judges could free up some resources, as in commercial-court cases. Such measures would have positive side effects on payment delays, as frequent arrears are particularly harmful for SMEs and recent measures to limit their abuse rely on efficient court procedures (Lewiatan, 2019; MR, 2019a).

Figure 2.14. Selected features of the OECD product market regulation indicators

Index scale 0 to 6 from most to least competition-friendly regulation, 2018

Note: Information refers to laws and regulation in force on 1 January 2018. The USA and Estonia are not yet included in the PMR database.

Source: OECD (2019), OECD 2018 PMR database.

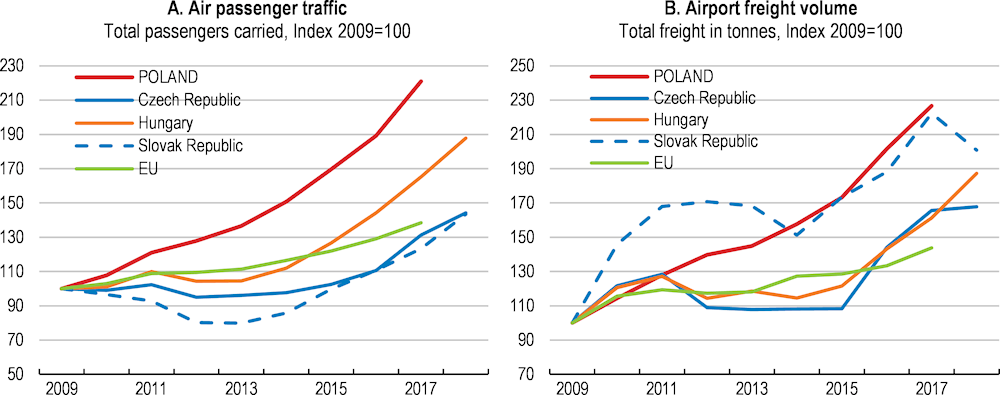

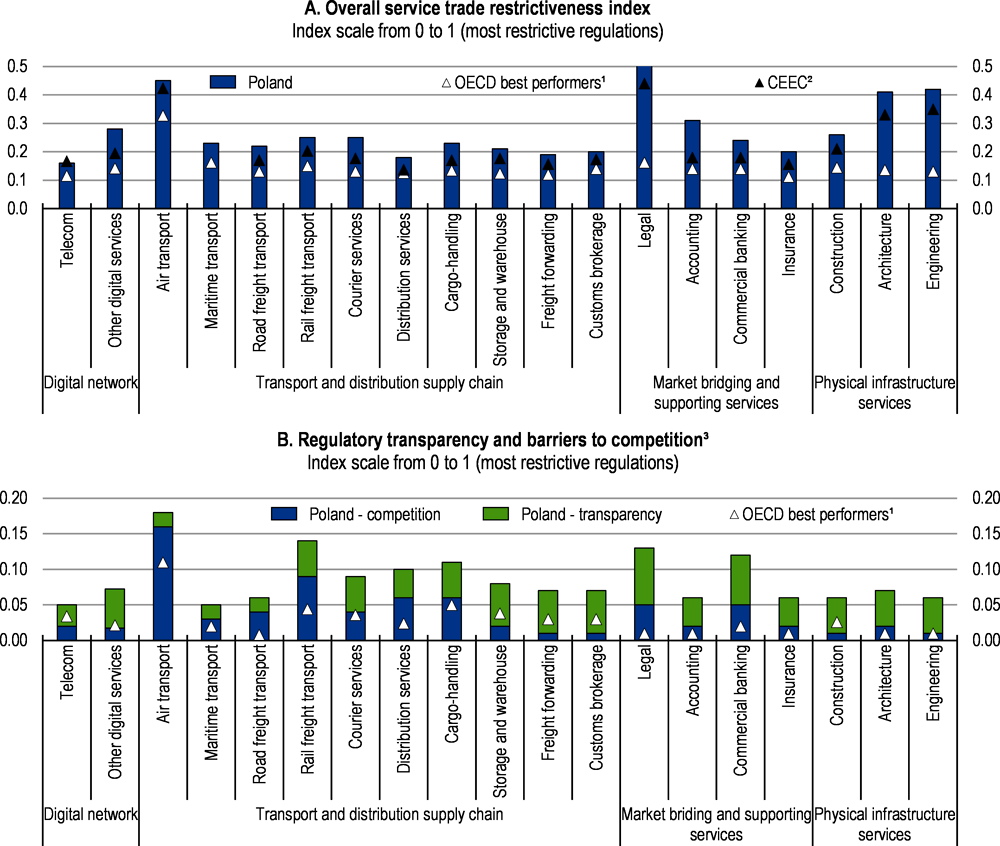

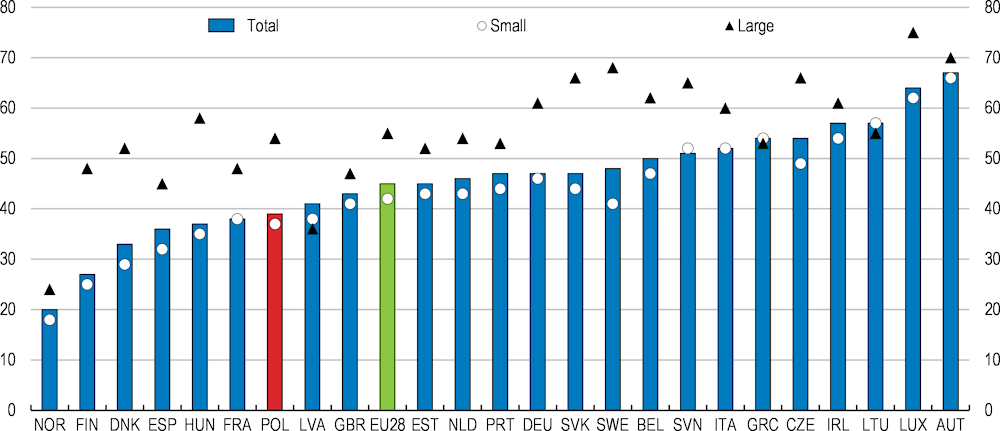

Services regulations have also significant room for improvement, since services inputs are often sourced domestically and key to access foreign markets. Services account for 35% of gross exports, but 55% of value-added exports, indicating that Poland’s exports of goods rely intensively on services inputs. However, some services professions still face relative high barriers to entry and, in the case of lawyers and notaries restrictions to their conducts (Figure 2.15 and Figure 2.16, Panel A). Occupational licensing and the lack of a temporary licensing system for foreign practitioners obstruct market entry and competition by professionals from outside the European Economic Area (OECD, 2019d).

The OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Indicator (STRI) also highlights horizontal barriers to international trade in services. Labour market tests and quotas for natural persons seeking to provide services in the country on a temporary basis as intra-corporate transferees, contractual services suppliers and independent services suppliers tend to lower international mobility. Procedures to obtain business visas and register a company are all significantly more numerous, costly or longer than best practice (OECD, 2019d). Relatively weak regulatory transparency and complex administrative procedures tend to add to firm operational expenses (Figure 2.16, Panel B). This setting weigh particularly on SMEs and potential exporters, as larger firms are better equipped to succeed in complex regulatory environments because of their broader resources, in-house legal expertise, existing networks of business partners, and the benefits of scale to absorb overhead costs (Rouzet et al., 2017).

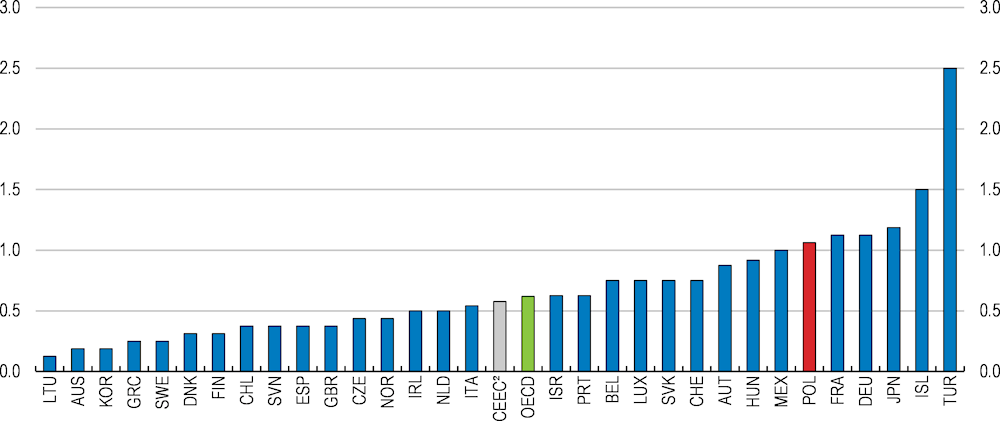

Figure 2.15. Some administrative procedures remain burdensome

Burden on new firms¹, scale 0-6 from least to most restrictive, 2018

1. Administrative requirements to set up limited liability companies and personally-owned enterprises.

2. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Source: OECD (2019), OECD 2018 PMR database.

Figure 2.16. Some services trade barriers remain important

Services Trade Restrictiveness Index by sector, 2019

1. The OECD best performers is the average of the five countries with regulations the most conducive to trade.

2. CEEC is the average of Hungary, Czech and Slovak Republics.

3. Most of the measures recorded as barriers to competition and issues related to regulatory transparency apply equally to domestic and foreign firms.

Source: OECD (2020), Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (database).

Strong regulatory governance is key to achieve further simplification. Poland has substantially improved its regulatory system (OECD, 2019c). Since 2015, public consultations are a general principle of the regulation making process, except for laws initiated by the Parliament. Existing consultations are often too quick or insufficiently taken into account (EC, 2019a; 2019b; and 2020). According to a recent exercise by the Supreme Audit Chamber, only a third of the impact assessments examined had been performed correctly (NIK, 2018a). Strengthening the role of consultations in the legislative process, allowing for sufficient time to gather relevant stakeholders’ views and building on some ministries’ best practices, would help lower the administrative burden resulting from frequent law changes (NIK, 2018a).

Easing tax compliance and ensuring sound public support for SMEs

Reducing further tax compliance costs for SMEs

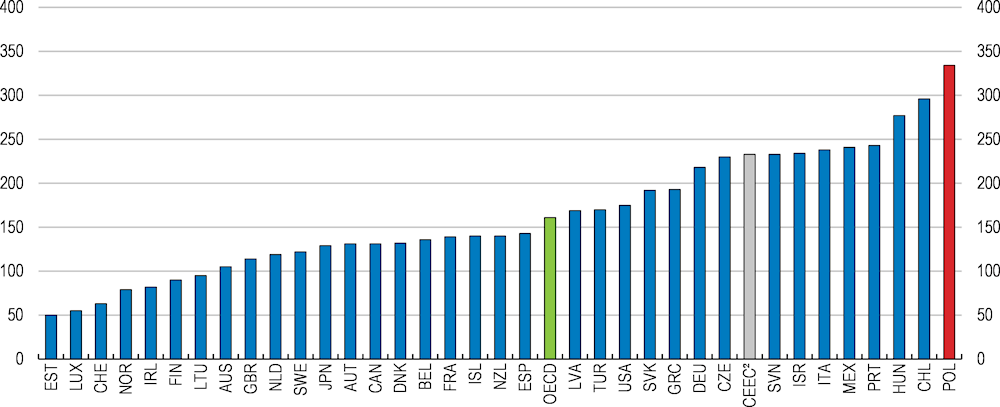

Tax administration remains particularly cumbersome for smaller firms and potential exporters. While there are various methods for measuring tax compliance costs (Box 2.3), the widely used World Bank Doing Business Indicators suggest that paying taxes takes many more hours in Poland than other OECD countries, despite the increased digitalisation of tax procedures and pre-filling of information on tax returns if available (Figure 2.17). In particular, the system of reduced VAT rates – despite its ongoing simplification – remains overarching (KPI). The payment of social security contributions also appears time consuming (World Bank, 2019).

The development of e-procedures could help to ease tax compliance. Although the process of reporting, paying and auditing taxes is now done electronically, time spent by a typical Polish company on meeting tax obligations has increased (EC, 2019a). Electronic Invoicing Systems could be streamlined to increase compliance and allow businesses to issue and receive invoices that are immediately available to the tax authorities. Such system could also provide, free of charge, a simplified and complete accounting framework to users. For example, in collaboration with software developers, Danish tax authorities embedded tax-related guidance and other functionalities in accounting software solutions targeted to small businesses.

Figure 2.17. Tax compliance costs remain elevated

Time needed to pay taxes¹, hours per year, 2019

1. The time to comply with tax laws measures the time taken to prepare, file and pay three major types of taxes and contributions: the corporate income tax, value added or sales tax and labour taxes, including payroll taxes and social contributions.

2. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Source: World Bank (2019), Doing Business 2020.

Ensuring appropriate fiscal support for smaller firms

Tax reliefs for smaller firms have been reformed recently. A reduced Corporate Income Tax rate and reformed Special Economic Zones aim to improve support for smaller firms both through a lower tax rate and through increase access for SMEs (Box 2.3). Special tax regimes for small and initially unprofitable firms, especially in a country with relatively high informality, can ease tax compliance and related fixed costs, particularly burdensome for SMEs (OECD, 2015). However, as shown by the experience of other OECD countries, reduced rates may also lead to misreporting of taxable income or size (Bergner et al., 2017), reducing incentives for dynamic firms to scale up and carry out exporting and innovative activities, like in France or Spain (Garicano et al., 2016; Almunia and Lopez-Rodriguez, 2013). The significant tax-rate gap of 10 percentage points between SMEs and larger firms in Poland could increase these risks. In addition, international evidence tends to show that small firms’ investment decisions are less sensitive to corporate taxes changes (OECD, 2010; OECD, 2015).

The costs and benefits of having such system should be reviewed – as planned - and, if needed, transitional measures should be introduced to smooth cliff edge effects when businesses transition from the preferential status. For example, employment-based or other thresholds could apply if reached for five consecutive years, as recently done in France. Yet, frequent tax and regulatory changes should be avoided as they induce significant adjustment costs for SMEs. Regional disparities create further difficulties, as the tax administration interpretations are only locally binding (OECD, 2018a).

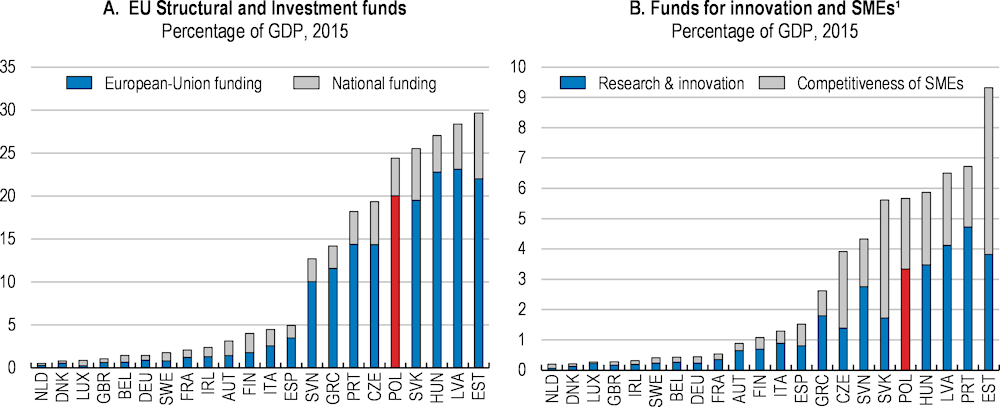

Ex post evaluation efforts of fiscal measures for SMEs should also be strengthened, notably to include the full economic impact and incorporate more systematically rigorous research designs. Ex post evaluations can be required at the request of the Council of Ministers or subsidiary bodies (OECD, 2018x). They are also mandatory in several instances, notably for the heavily relied on EU-funded programmes (Figure 2.18). Yet, such efforts have been partly lacking (OECD, 2016a). For example, the agency in charge of business innovation subsidies has no obligation to monitor their effectiveness, though it granted support worth 0.3% of GDP in 2015 (NIK, 2016). Moreover, evidence about the effectiveness of the 2017 R&D tax break is also lacking though its take-up has increased rapidly. Defining ex ante the timing of the evaluation would have allowed a more efficient adjustment of the scheme and avoided incentives for firms to delay investments. More generally, systematically evaluating business support schemes would help to ensure that they are constantly improved based on experience and that the most effective programmes are strengthened in the longer term.

Figure 2.18. Business and SMEs’ support are heavily reliant on EU funds

1. EU and domestic funding. The data refers to European Structural and Investment Funds with thematic objectives “Research &

Innovation” and “Competitiveness of SMEs”. For comparison across countries, the figure excludes some measures for technical

assistance that represent 3.4% of expenditures under the Smart Growth operational programme in Poland.

Source: European Commission (2016), ESIF Finance dataset.

Box 2.3. Recent policy initiatives and ongoing discussions to support SMEs

The 2018 Business constitution and “100 Changes for Enterprises”

The measures aims at reducing the administrative burden, as well as simplifying bureaucratic procedures, notably for small and medium-sized enterprises and foreign investors. Key changes include:

Simplified registration procedures and an exemption for the smallest businesses (whose turnover does not exceed half the minimum wage). The threshold for full accounting obligations was also lifted from EUR 1.2 million turnover annually to EUR 2 million. In addition, new firms benefit from a “right to error” for a one-year period.

Social security exemptions for the first six months of setting up a business. Entrepreneurs may benefit from reduced contributions, through the so-called "small ZUS" scheme over the next two years.

Measures aimed at improving the administrative trust for businesses. Notably: presumption good faith and creation of the Ombudsman for small and medium-sized enterprises; ministries are required to publish simple explanations of administrative rules and tax laws; companies need to keep financial statements only for five years now rather than indefinitely.

A new law also allows to prevent cessation of legal personality of an enterprise – notably family-owned and smaller firms – in the case of death of the entrepreneur, by setting rules for temporary management of business activity after death of an entrepreneur.

The 2018 reform of special economic zones (SEZ)

The previous network of special economic zones (used mainly by larger industrial companies) was transformed into a countrywide investment tax credit with the view of boosting SMEs’ take-up. The level of support depends notably on firm size, the local unemployment rate and other qualitative criteria, such as the assessed potential of sector, as well as the expected social and environmental effects. As a result, refundable tax credits for CIT and PIT (for non-legal entities) depend on the initial investment, the region and firm size. They amount to: i) 10% to 50% of the initial investment for large enterprises; ii) 20% to 60% for medium-sized enterprises, iii) 30% to 70% for micro and small enterprises.

The 2019 reduction in corporate income tax rate for SMEs

The authorities reduced the corporate income tax rate for SMEs to 9% (instead of 15% since 2016 and the standard rate of 19%). It applies to firms having annual turnover equal or less than EUR 1.2 million. In order to prevent tax optimisation, this reduced rate does not apply to taxpayers starting their activity, if their activity was created as result of transformation of one company into another company or of a company division.

The 2019 simplified joint stock company

The new simplified joint stock company (P.S.A.) will facilitate starting up a business in March 2021. It has low capital requirements, possibly only 1 PLN, simplified registration online within 24 hours and light procedures to dissolve the company.

The 2019 changes to the programme supporting investments of major importance over 2011-30

The reform aimed to ease access to SMEs by amending project requirements and introducing qualitative assessments. The minimum eligible costs and the job creation thresholds for R&D investments were lowered. Cash grant supplements can now be awarded in less developed regions and to cover training costs. In addition, the assessment of investment projects now includes qualitative objectives such as sustainable development, social responsibility and scientific development.

The 2020 regulation on late payments

The new regulation introduced legally binding deadlines for payments, which is set to help address arrears and support enterprises’ financial liquidity.

The “Estonian CIT”

The authorities are considering the introduction of a new voluntary Corporate Income Tax (CIT) scheme for SMEs. Under the new measure, SMEs with revenues below PLN 50 million (approximately EUR 11 million), whose passive revenues do not exceed those from operating activities and whose shareholders are individuals, would not pay income tax as long as revenues are reinvested. CIT collection would only occur when these SMEs pay out dividends to shareholders. The scheme is expected to reduce obstacles for SMEs development, boost investment and employment.

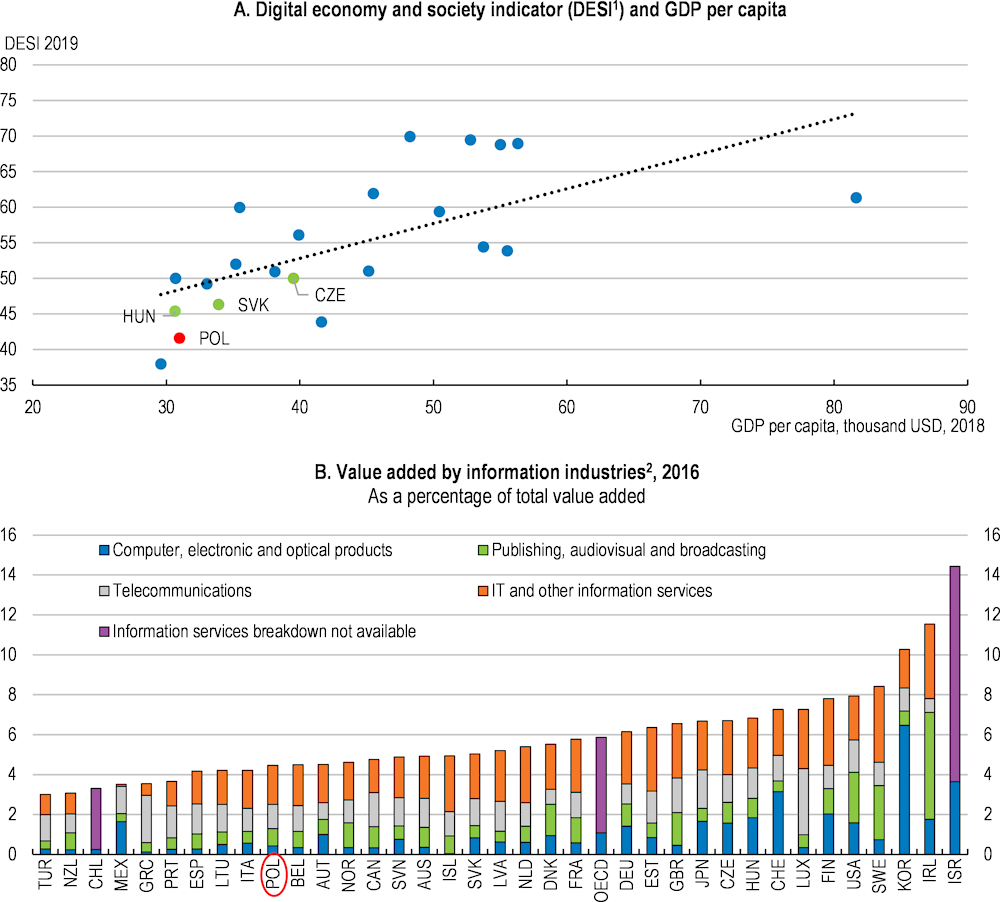

Increasing SMEs innovation, its diffusion and productivity

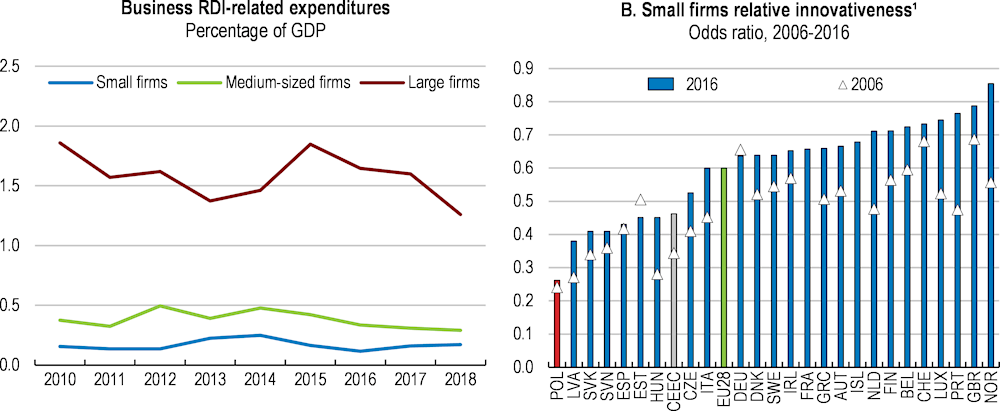

Poland’s business sector spends relatively little in the generation of knowledge-based capital. Both business research and development (as a percentage of GDP) and the number of patents (per capita) are in the OECD’s lowest quadrant (OECD, 2018a). This partly reflects the dominance of SMEs in the economy. While many SMEs may be unlikely to develop radical innovations, empirical evidence suggests that performing research activity is important for their ability to demystify new technologies being developed abroad and adapt them to suit their production processes (Griffith, Redding and Reenen, 2004).

Stimulating private-sector research and innovation, which has been stable as a share of GDP could help raise SMEs internationalisation (Figure 2.19). Indeed, the low level of business R&D spending largely reflects little investment by local firms, especially SMEs, hindering the diffusion of innovation and GVC integration, which requires state-of-the-art producing processes. More than 70% of SMEs reported not to have state-of-the art machinery and equipment in 2018 (EIB, 2019).

Figure 2.19. SMEs lag R&D investment and innovation

1. Share of innovative firms among 10-49 employee firms divided by the share of innovative firms among firms with over 250 employees.

Source: OECD calculations based on Statistics Poland (2017; 2019 and 2020), Expenditures on Innovation Activities, Statistics Poland, Warsaw and OECD (2020), National account database; Eurostat (2019), “Community Innovation Surveys (CIS) 2006-16”, Eurostat Database.

To stimulate research, development and innovation, public support for SMEs, start-ups and businesses has increased sharply. In particular, tax incentives have steadily increased through several reforms of the 2016 R&D tax allowance. For example, the tax-deductible proportion of R&D expenditure on labour increased from 30% to 100% over 2016-18. In 2017, the authorities also expanded the list of tax-deductible R&D spending, made the subsidy refundable for start-ups in the first year of business activity (two years for SMEs) and extended the credit carry-forward option from three to six years. As a result, the number of taxpayers using the relief increased significantly from 638 in 2016 to 1186 in 2017 (PIE, 2019).

However, the total amount spent in R&D support is still low, at 0.11% of GDP in 2017 (OECD, 2019e). Moreover, the average amount in claimed expenditures for tax credit remains high, suggesting small firms are taking less advantage. If take-up of the R&D tax relief by innovative SMEs remains low, making the tax credit refundable for SMEs operating more than two years and beyond the first year of a start-up could help boost SMEs’ R&D spending. Developing standardised definitions for R&D expenditures, compiling a common list of qualified costs and offering services to assist firms in tax-claiming procedures (e.g. online information and simplified claims forms) would also help (OECD, 2018a).

The authorities could also give greater priority to direct support schemes. Grants are easier to monitor than general tax deductions, which require more checks. A well-designed and targeted strategy, based on closer co-operation between public research entities and businesses, could also help strengthen the country’s research capacities. In fact, science-industry linkages remain generally weak (OECD, 2018a). Austria, for instance, is pursuing interesting initiatives thanks to the COMET (Competence Centres for Excellent Technology) programme and the Christian Doppler Laboratories (Comet, 2018; Cdg, 2018), which have been successful in promoting cooperation between companies and application-oriented research over the past two decades, especially in the automotive industry (Harms, 2018).

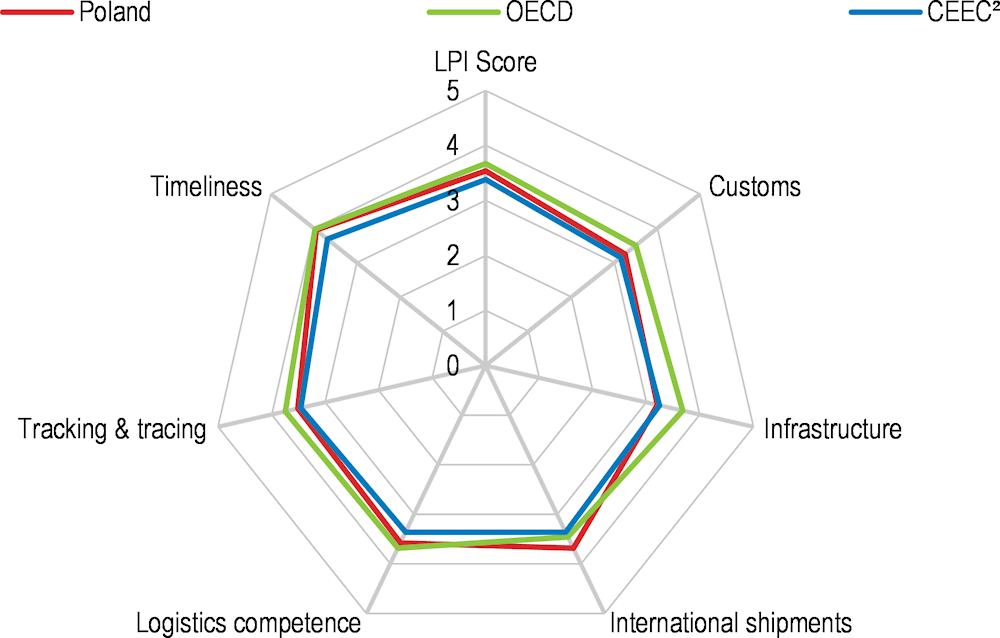

Trade facilitation has improved

Trade policies have successfully increased SMEs’ ability to handle fixed costs associated with exporting and importing. According to the OECD Trade Facilitation Indicator, Poland exceeds or is close to the best performers in all areas (OECD, 2019f). Poland’s performance has improved between 2015 and 2017 in terms of information availability and streamlining of procedures. Similarly, the cost of importing and exporting is low in international comparison (World Bank, 2019). Yet, the efficiency of custom clearance processes could still be improved (World Bank, 2017, OECD, 2019f). Expanding the use of pre-arrival processing and of Authorised Operators could help reduce variable costs, increase the value of imports and exports, as well as support timely delivery to consumers.

In a welcome move, the authorities recently reformed the exports promotion and investment framework to provide Polish companies with more help to expand into foreign market (Box 2.4). In 2017, the Polish Investment and Trade Agency (PAIH) replaced the Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency (PAIiIZ) as the main institution responsible for promotion and facilitation of foreign investment. The government has also extended the mandate of its investment promotion agency to export promotion and increased its resources significantly. Since 2017, Polish sectoral brands promotion programs have been launched in Asia, Africa and Latin America, helping particularly SMEs. To offer on-site direct assistance, PAIH also runs a network of Foreign Trade Offices that are notably focused on distant markets with rapid growth potential for Polish exporters and investors (Box 2.4). The Polish lnvestment and Trade Agency (PAIH) does not offer financial instruments (except Polish Tech Bridges), but help to get support for international expansion from other financial institutions belonging to the Polish Development Fund (PFR). Apart from the support from PAIH, the Ministry of Economic Development encourages SMEs’ internationalisation. For example, since 2016, Polish sectoral brands promotion programs (BPPs) have been carried out, to promote selected industries (based on their estimated export potential). SMEs may also obtain support to cover part of the costs related to participation in fairs, trainings and economic missions as well as other specific information and promotion undertakings. In addition, the Ministry plans to launch a new online portal to facilitate and promote SMEs’ exports. This strategy is welcome, as coherent export support services have been lacking so far, and evidence suggests that high-quality investment promotion services tend to translate into stronger FDI inflows (Harding and Javorcik, 2013) with potential benefits for innovation and productivity.

The regular organisation of business meetings and SME associations with Foreign Trade Offices of the Polish lnvestment and Trade Agency (PAIH) could be a useful mechanism for helping Polish SMEs to reduce search costs and overcome trust barriers, to adopt superior management practices, and to raise productivity. International evidence as shown that such business networks may have a causal impact on firm performance (Cai and Szeidl, 2018). The example of Germany’s structured network of public and private organisations could help to strengthen the Polish framework in this direction. The German Chambers of Commerce Abroad act as a link between the local and regional levels and the federal Germany Trade and Invest network in Embassies and consulates through the domestic regional Chambers of Industry and Commerce. The public-private cofinancing of the German Chambers of Commerce Abroad also helps to ensure the relevance of their actions (EESC, 2018). Austria’s internationalisation initiative “go-international”, also targets SMEs and builds on public-private financing to establish export relationships for the first time, or to open up new markets abroad. The initiative provides various support measures through a collaboration between the Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs and the Federal Economic Chamber.

Developing local clusters and SMEs’ consortia could boost internationalisation

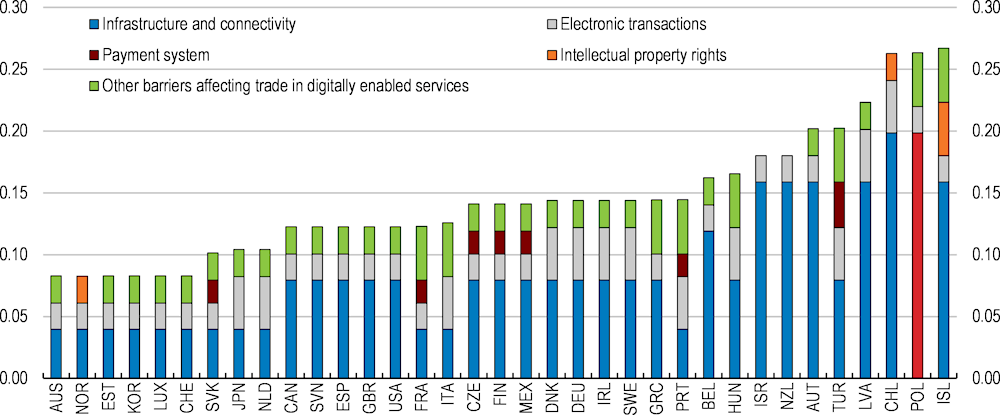

Export consortia appear to be rare (MR, 2019b) and collaboration between companies is perceived as weak (Figure 2.20). To promote knowledge exchange, notably of export markets, and agglomeration economies, Poland has tried to develop local clusters and sectoral consortia. For example, the Torun region provided seed funding to several companies to establish a cluster and compete as a unique group offering complete solutions to potential contractors in other countries (Filippaios, 2018). Scaling up such experience could create successful exporters and innovation hubs by promoting the cooperation of interconnected firms, suppliers and research institutions (Marchese et al., 2019), capitalising on the already strong spatial concentration of exporting and innovation activities in Poland (Albinowski et al., 2016).

SMEs could combine their human and financial resources by creating networks of small businesses or collaborating with larger firms for exporting activity or training (see below). Participating in an export consortium reduces the risks and costs involved in penetrating foreign markets for SMEs (Unido, 2005). This could be done by creating a new legal form to accommodate export consortia and incentivising the participation of small businesses with grants or tax benefits (OECD, 2017b). For example, the Italian Institute for Foreign Trade gives grants to export consortia to incentivise their development. In order to qualify, export consortia must comprise a minimum number of SMEs.

Figure 2.20. Strengthening firms’ cooperative linkages and clusters could support SMEs

Polish cluster initiatives are relatively recent, and few have proven effective so far. There are around 130 clusters in Poland (PARP, 2020). In particular, the 15 National Key Clusters (NKC) have to define a business strategy and provide business services for their members. Yet, in many cases, the clusters’ innovative activity and orientation towards foreign markets is low and their financial viability without subsidies is questionable (OECD, 2018a). Many lack a common business strategy for their members and make insufficient use of mentoring, coaching and business development services. The management of these structures often lack information about innovative activity and economic results of the participating firms, precluding effective evaluation (NBP, 2016; NIK, 2016). PARP currently provides information on clusters activities every second year, investigating and benchmarking the activities of National Key Clusters and a sample of other clusters. A prerequisite could be to develop, as planned, a database of potential suppliers for exporters and large MNEs. This would ease the integration of SMEs into domestic and global value chains, as done in Czech Republic through the “CzechInvest” project, which connects foreign investors with potential suppliers.

Going forward, the government is focusing its support on a small group of 15 National Key Clusters selected competitively as the most promising initiatives in terms of size, management quality, innovative activity and presence in foreign markets. Public support is meant to help them expand further abroad. Given that little is known about effective policies to support clusters, it seems sensible to concentrate on framework conditions, such as internationalisation, investment in infrastructure and training. This should include efforts to improve cluster management in line with the requirement to have an explicit strategy, as well as links to research institutions. Publicly supported clusters, technology parks and similar initiatives should be required to set up a plan on how to increase own earnings. Those failing to gradually reach viability should eventually lose their subsidies. Beyond benchmarking exercises and the regulator monitoring of clusters, a robust evaluation framework is needed to better understand what works. National and local initiatives should be regularly evaluated, as international evidence on spillovers and productivity effects of place-based incentives has been mixed so far (Slattery and Zidar, 2020), despite studies showing positive agglomeration effects on innovation (Carlino and Kerr, 2015).

There is still scope to improve technical assistance and mentoring to small businesses at the local level. SMEs are often located in lagging regions (Figure 2.13). Building on the existing local business centres and contact points for EU funds, at the municipal or regional level, local support institutions could be strengthened. Such practices have been experienced for the development of business services centres in some medium-sized cities (Radom, Tarnów, Elbląg and Chełm) to help promote their attractiveness (MR, 2019c). To avoid making such centres excessively dependent on local budgets, some national financing from an earmarked subsidy of the state budget could facilitate cooperation between firms and local institutions.

Box 2.4. Main institutions supporting SMEs and their internationalisation

The Polish Agency for Enterprise Development (PARP)

The Polish Agency for Enterprise Development (PARP) manages a wide range of instruments and programmes designed to support business development, innovation and SMEs:

During the 2014-20 financial perspective for European Funds, PARP has been providing financial instruments to help SMEs in the promotion of product brands, support SMEs’ internationalisation in Eastern Poland and promote the internationalisation of “National Key Clusters” (KKK). In 2020-22, new industry promotion programs have also been introduced.

In 2018, it launched the SMEs’ Development Centre. This web portal offer information and consulting services to SMEs.

In 2019, to help small and young companies in gathering capital for their development, PARP introduced a new development loan for micro and small companies. The loan can be used for purchase and delivery of new fixed assets, purchase of software, integration of purchased software with an existing machine park or IT system.

PARP also finances investment in management skills through a human resources programme co-funding training with firms, as well as the innovation manager academy, and a range of programme designed at boosting SME’s innovativeness (Box 2.5).

The Polish Investment and Trade Agency (PAIH)

The Polish Investment and Trade Agency (PAIH) supports both the foreign expansion of Polish business and the inflow of FDI into Poland. Actions targeted towards SMEs include:

A network of Foreign Trade Offices that are responsible for providing free-of-charge support for exporters and investors abroad.

The 2018 Tech Bridges project, funded by the European Regional Development Fund, which supports foreign expansion of start-ups and SMEs with high potential.

Networking events: in 2018, PAIH organised the first Support Forum for Polish Business Abroad - PAIH Expo - for SMEs which planned to or had already been pursuing foreign expansion. The event presented public services supporting participation in foreign markets.

The state-owned development bank (BGK)

The national promotional and development bank (BGK) promotes entrepreneurship and the development of micro companies and SMEs by offering guarantees, surety instruments, as well as loan and equity instruments:

To ease access to bank loans, BGK grants de minimis guarantees in cooperation with commercial banks. In co-operation with the EIB group, BGK supports SMEs by providing portfolio guarantees to commercial banks counter-guaranteed by the guarantee of the European Investment Fund.

BGK provides trade finance instruments and direct loans for larger transactions for SMEs and larger firms. The PAE programme launched in 2017 also offers guarantee against the risk of non-payment under letter of credits from commercial banks.

For the implementation of the 2014-20 European Structural Investment funds, BGK operates funds of funds for 15 regional and 2 national programmes. These programmes provide preferential loans, guarantees and equity instruments for SMEs through financial intermediaries to address investment and innovation needs and financing gaps, as well as the impact of the coronavirus crisis.

BGK is also in charge of the “Loan for technological innovations” for SMEs financed through European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). BGK provides non-repayable support for loans granted by commercial banks that may reach up to 70% of total eligible costs of investment.

The Export Credit Insurance Corporation (KUKE)

The company provides export credit insurance with State Treasury backing, notably for markets exposed to higher political risk. Its operations focus on insuring trade receivables arising from the sales of goods and services with deferred payment, as well as providing bonds.

Increasing skills to foster integration in global value chains

Raising skills through better life-long training

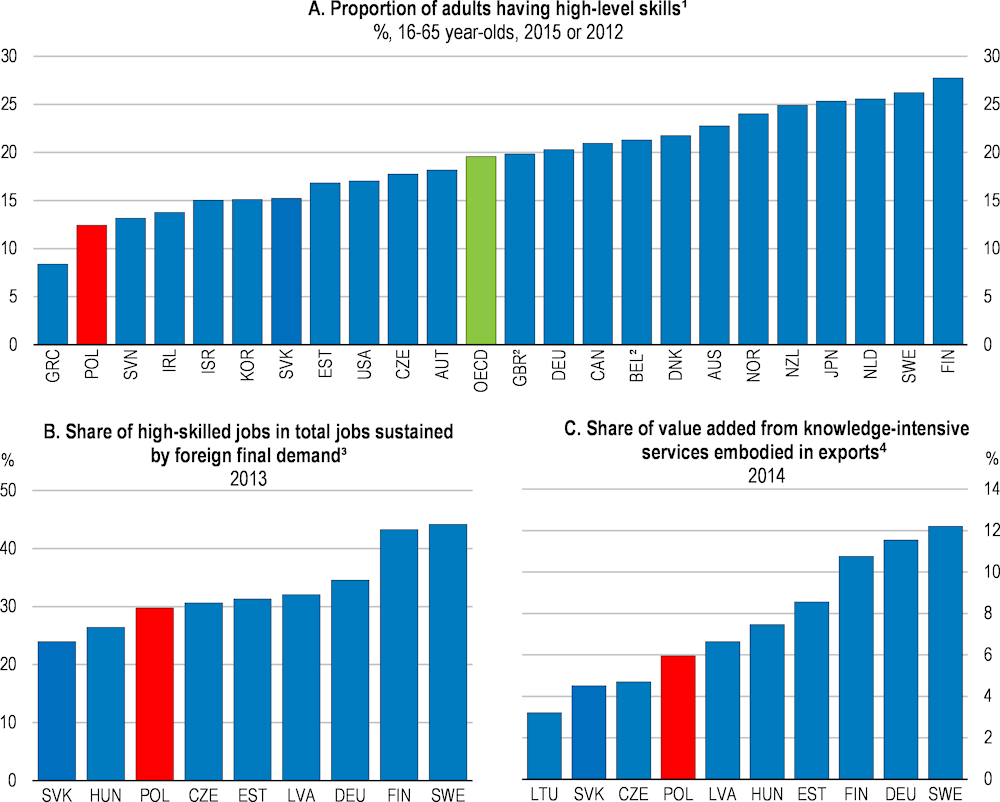

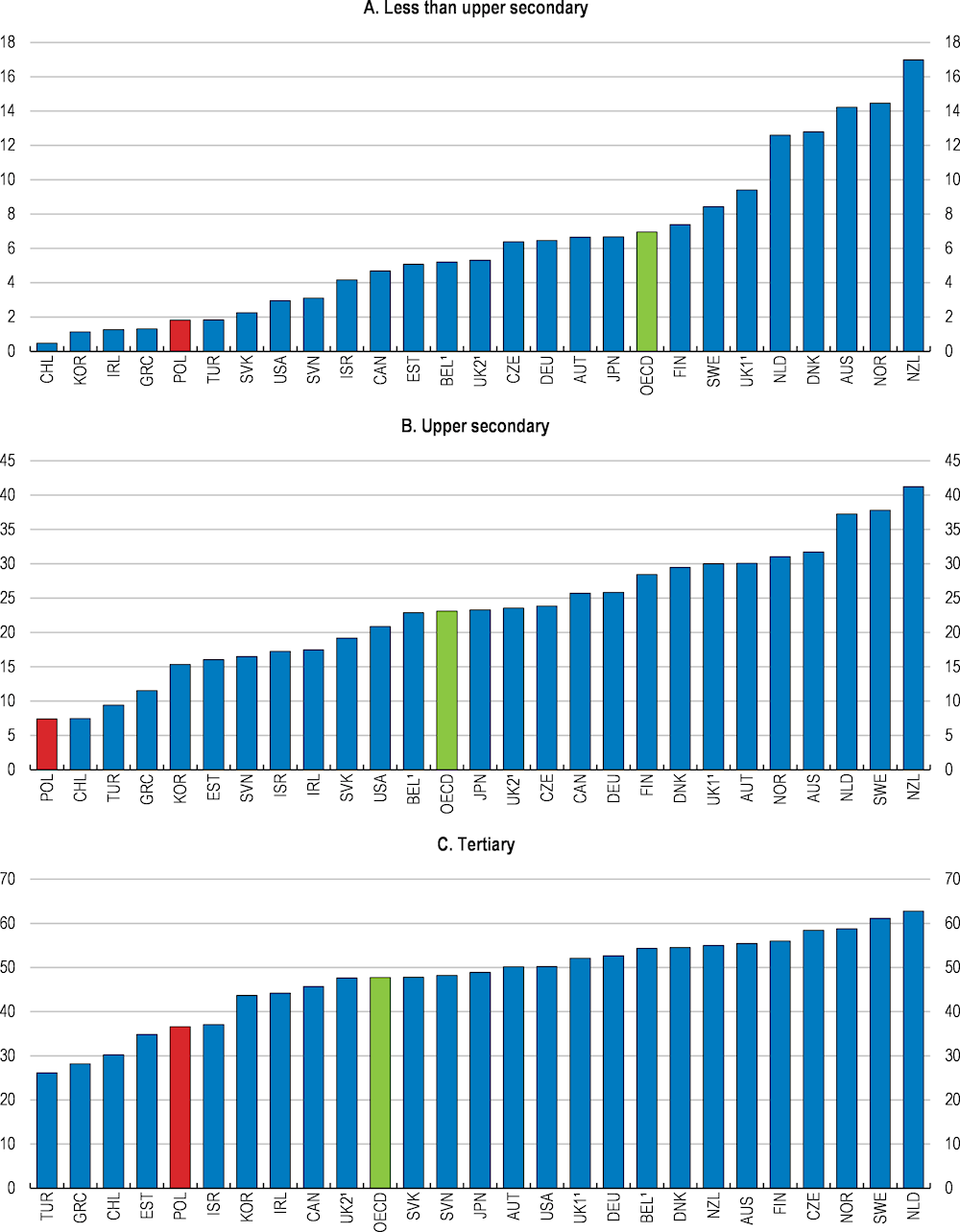

With its relatively low wage costs, Poland has increased its exports and turned itself into an attractive market for foreign investors. The workforce is increasingly educated, suggesting significant opportunities for further internationalisation. Poland foreign language skills, in particular English, are generally well ranked in international comparison and have increased rapidly (EF, 2019). Yet, the internationalisation of Polish firms tends to rely on relatively low skills and few knowledge-intensive services compared to other OECD countries. In addition, the share of adults having a high-skill level is lower than neighbouring countries and the OECD average (Figure 2.21).

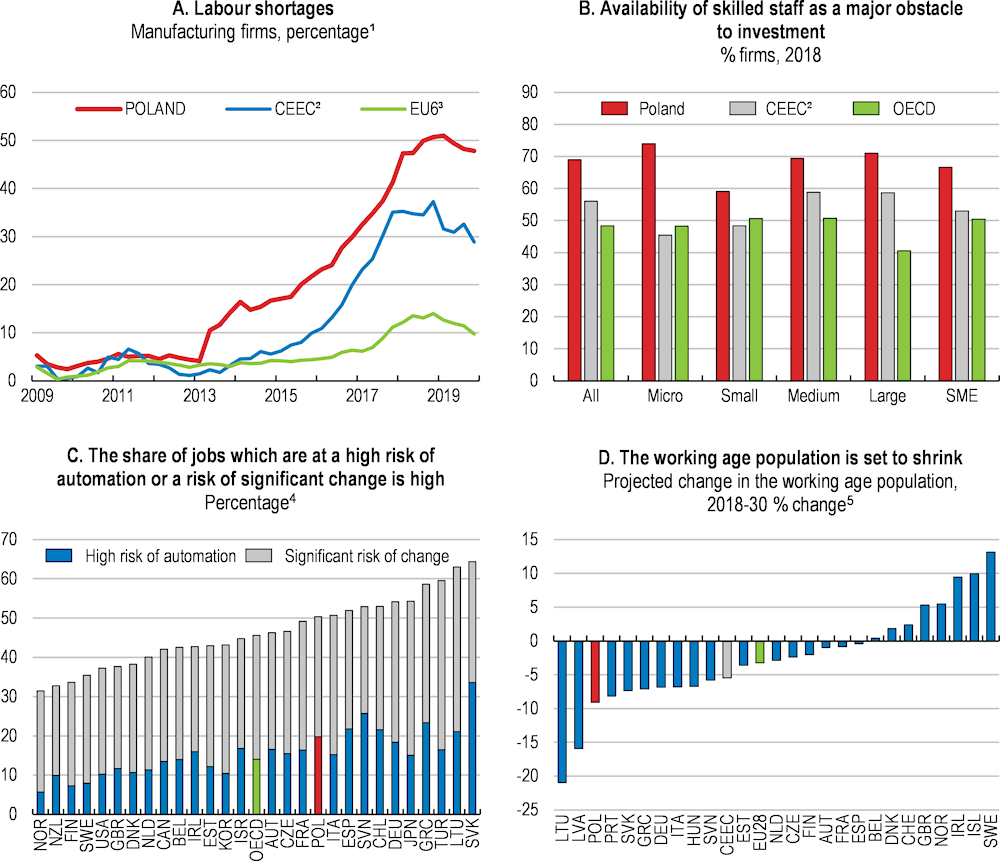

A vital condition for improving SMEs internationalisation is the existence of a sufficiently large pool of workers with a high level of education and skills. Before the coronavirus crisis, the unemployment rate was at a 20-year low and business surveys indicated labour shortages as a key factor limiting production, across firm size (Figure 2.22, Panels A and B). In the short term, the education and training system will face strong needs to facilitate the reallocation of displaced workers towards sectors and firms that have high potential. In the longer term, it will be important to strengthen the skills needed for the adoption of technological innovations (OECD, 2019g; Lang and Mendez Tavares, 2018). Indeed, automation is set to affect a significant share of jobs, while population ageing is set to lower labour supply (Panels C and D).

The high rate at which skills become obsolete makes it harder for seniors to find work, whereas demographic ageing requires better employability and working conditions of older workers. According to forecasts produced by the national statistics institute, if nothing changes, the active population growth rate will be only just over half that of the total population between 2017 and 2070. Seniors will therefore have to work until later in life, which means they need to fight against stereotypes and discriminations.

Digitalisation may accelerate skill depreciation for many workers, increasing inequality. Almost 50% of jobs in Poland could become redundant or risk changing substantially due to new technologies (Figure 2.22, Panel C). Automation and digitalisation are set to further reduce demand for manual and repetitive tasks, and increase demand for interpersonal and problem-solving skills to ensure machines’ and workers’ complementarity (OECD, 2018c).

Figure 2.21. The share of high-skilled adults and their contribution to GVCs is low

1. Average of percentage of adults scoring at PIAAC literacy or numeracy proficiency level 4 or 5, or scoring at problem solving in technology-rich environments level 2 or 3.

2. Data for Belgium refer only to Flanders, and data for the United Kingdom refer only to England.

3. OECD calculation of the decomposition of total employment sustained by exports into three groups of skills intensity defined according to major groups of the International Standard Classification of Occupations 2008: High-skilled occupations (ISCO-08 major Groups 1 to 3), medium-skilled (4 to 7) and low-skilled (8 and 9).

4. OECD estimates based on the OECD Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) table and the OECD Bilateral Trade Database by Industry and End-Use (BTDIxE).

Source: OECD (2017), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators ; OECD (2017), Skills Outlook 2017: Skills and Global Value Chains; OECD/WTO (2016), Statistics on Trade in Value Added (database).

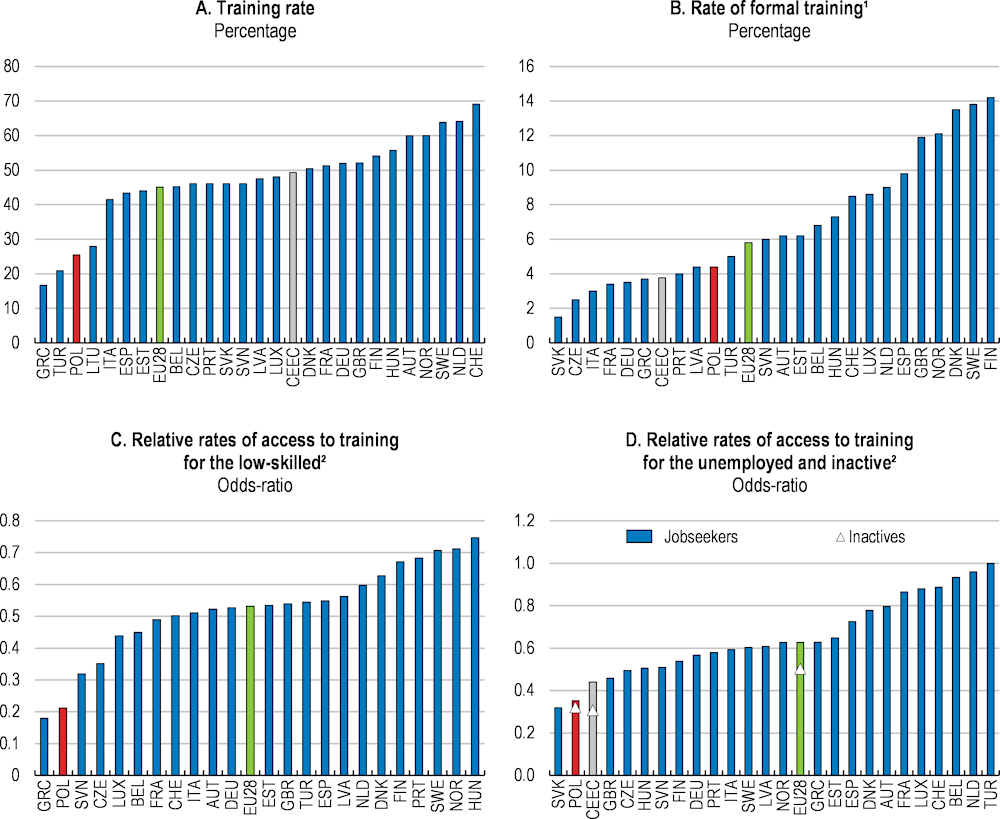

Enhanced lifelong learning will be essential. The percentage of adults with little education attainment has increased and participation in continuous training is relatively low, despite the estimated high returns to job related training (Fialho et al., 2019). As in many OECD countries, low-skilled, unemployed and inactive workers struggle to access training, notably formal training courses (OECD, 2017c). Despite recent improvements, namely through the European Social Fund operational programme “Knowledge Education Development”, which aims at promoting lifelong learning and is regularly assessed, there is still little evaluation of the quality and effectiveness of training programmes (OECD, 2019h).

Figure 2.22. Shortages of skilled staff, demographic ageing and automation remain major issues

1. Percentage of manufacturing firms pointing to labour shortages as a factor limiting production.

2. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics. Jobs are at high risk of automation if the likelihood of their job being automated is at least 70%.

3. EU6 is the average of France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Denmark, and the Netherlands.

4. Jobs at risk of significant change are those with the likelihood of their job being automated estimated at between 50 and 70%. Data for Belgium correspond to Flanders and data for the United Kingdom to England and Northern Ireland.

5. Eurostat baseline projections including migrations, the working-age population refer to those between 15 and 64 years old.

Source: European Commission (2019), Business and consumer survey database; EIB (2019); OECD calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012); and Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), "Automation, skills use and training", OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202, , https://doi.org/10.1787/2e2f4eea-en; Eurostat (2019), Population projections.

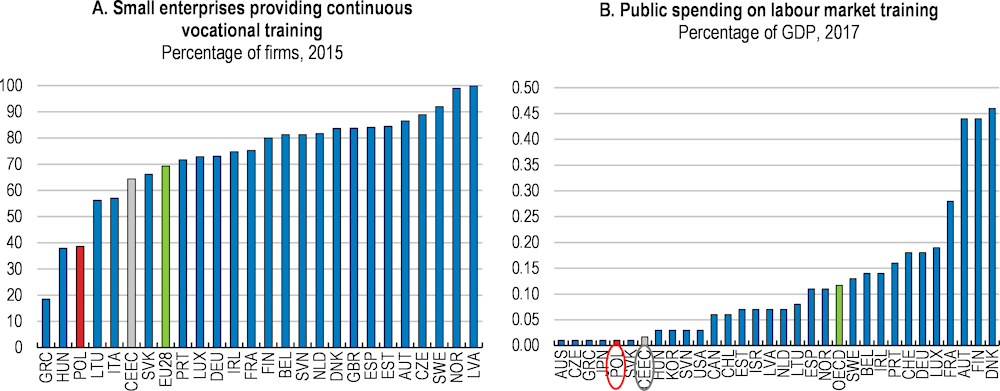

Workplace training for SMEs is particularly costly (Figure 2.24, Panel A). There is fewer staff and resources, the retention rates are low and the risk of poaching by other firms is high (OECD, 2019i). Providing additional financial support and technical assistance to SMEs would help to increase work-based learning opportunities. Financial support for the development of programmes and cost reimbursement have proved to be the most effective initiatives in improving SMEs work-based learning (Strzebońska, 2017).

Figure 2.23. Training is low and insufficiently targeted, 2016

1. Adults aged between 25 and 64 enrolled in education or training during the last twelve months.

2. Participation rate of adults with education up to the first cycle of secondary education (unemployed or inactive in Panel D) compared to the participation rate of all adults.

Source: Eurostat (2019), "Adult training: Participation rate in education and training", Eurostat database.

Public financing of training could offer more support for SMEs (Figure 2.24, Panel B). Co-financing of employees’ training is mainly provided through the National Training Fund (NTF) and European funds. Any enterprise can apply to the KFS for an 80% refund of training costs, while micro-sized enterprises can apply for 100%, up to a maximum of 300% of Poland’s average monthly salary per employee. In 2017, over 18 000 enterprises received KFS funds, half of which were micro-sized enterprises. However, uptake of the KFS has been limited and many applications are unsuccessful. In 2017, 32% of KFS applications were unsuccessful, because the funds were exhausted (OECD, 2019i).

Another important factor is the lack of awareness of current arrangements for work-based learning (OECD, 2019h). In addition, the available information often uses too technical and complicated language (Strzebońska, 2017). Workshops’ and focus groups’ participants confirmed that financial and informational barriers prevent SMEs from engaging in work-based learning. Poland could benefit from the experiences of other OECD countries in improving SMEs’ participation in work-based learning (Box 2.5). For example, the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development (PARP) should continue to improve the Database of Development Services (BUR), which is widely used by SMEs, to make the portal more user-friendly and comprehensive in terms of the programmes included, user satisfaction data, career and development counselling, recognition of prior learning and available public funding (OECD, 2019h and Box 2.6).

Conditions to access training should be adapted to support the unemployed and non-standard workers. Though Public employment services (PES) focus on supporting unemployed people in adapting their skills to new labour market needs, they have limited funding and staffing (OECD, 2018a). The rapid turnover of workers on temporary contracts does not incentivise training participation. Adopting individual training accounts, as in France, would make the training rights “portable” from one job or employment status to another, and potentially improve access to lifelong learning for low-skilled workers. Yet, this would also require improved access to effective information and guidance to be fully effective (OECD, 2019j).

Box 2.5. Boosting SMEs participation in adult learning, international examples

Training associations in Switzerland

In Switzerland, the government established vocational training associations (Lehrbetriebsverbünde) in 2004. These associations of two or more training firms share apprentices, whose training is organised across several firms on a rotating basis. The aim is to enable the engagement of firms that lack the capacity and resources to provide the full training of an apprentice, and to lower the financial and administrative burden on individual firms. The Confederation subsidises the associations with initial funding during the first three years for marketing, administrative and other costs necessary to set up the joint training programme. After this initial support, the training associations are supposed to be financially independent. An evaluation found that the majority of firms participating in training associations would not have engaged in training otherwise.

Support for SMEs’ training in Flanders (Belgium)

The SME Wallet (KMO-portefeuille) is targeted exclusively at SMEs and is designed to help them grow and become more competitive through training and advisory services. The SME Wallet covers 20-30% of training costs, depending on the size of the enterprise, with a maximum budget of EUR 7,500 per year. SMEs can apply for subsidies online to receive a direct transfer. Employers determine their own training needs and there is no targeting element (OECD, 2017[6]). A recent impact assessment determined that participating firms achieved higher growth than a control group.

Source: OECD (2019), OECD Skills Strategy Poland: Assessment and Recommendations, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b377fbcc-en; OECD (2019), OECD Skills Strategy Flanders: Assessment and Recommendations, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264309791-en. Kuczera M., V. Kis and G. Wurzburg (2009), OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training: A Learning for Jobs Review of Korea 2009, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264113879-en.

Figure 2.24. Public funding for training is low and small firms provide low access to training

Note: Continuing vocational training (CVT) are training measures or activities which have as their primary objectives the acquisition of new competences or the development and improvement of existing ones and which must be financed at least partly by the enterprises for their persons employed who either have a working contract or who benefit directly from their work for the enterprise such as unpaid family workers and casual workers.

Source: OECD (2019) Employment and Labour Market Statistics: Labour market programmes: expenditure and participants ; Eurostat (2019), Continuing vocational training in enterprises database.

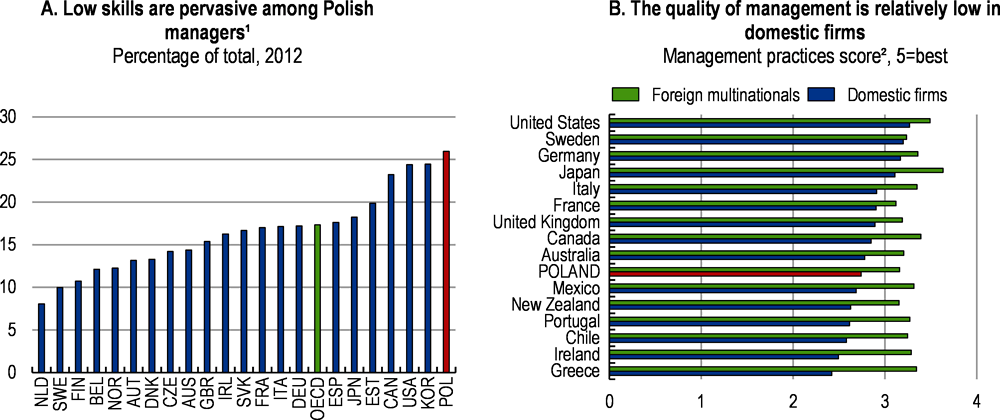

Supporting better management skills for SMEs

Many SMEs do not have strong human resource infrastructures to implement training policies and, more generally, internationalisation and growth strategies. A number of studies shows that management skills can be improved, with positive effects on internationalisation (Figure 2.25; Bloom et al., 2018). As in other CEE countries, SMEs with a structure that is favourable to innovation and its diffusion are underrepresented (Lorenz and Potter, 2019). The limited number of highly skilled managers is considered one of the main barriers to growth, and the lack of support from management is a barrier to innovation (Zadura-Lichota, 2015) including the adoption of digital tools (see below) or efficient energy management process (Chapter 1). For example, high-performance workplace practices are less frequent in medium than large companies (PARP, 2019b; OECD, 2017a).

New initiatives have contributed to develop managerial skills in SMEs at different stages of business expansion, notably to access foreign markets (Box 2.6). Yet, the government could play a stronger role in disseminating high-performing organisational and management practices. Another step would be to adopt such practices in public administrations and the numerous government-owned enterprises (Figure 2.14), with potential spillovers to the private sector (OECD, 2019i).

Several OECD countries, including Australia, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Sweden have implemented programmes to improve the managerial and organisational performance of firms. For example, the Finnish Workplace Development Programme (TYKE from 1996 to 2003, TYKES from 2004 to 2010, thereafter Liideri) aimed to disseminate new work and management practices, and to develop a “learning organisation” culture to counter sluggish productivity growth in many traditional industries. Networks played an increasing role and there was a strong emphasis on disseminating good practices and mutual learning. Qualitative evaluations suggest that the programmes did promote workplace innovation and productivity. Coaching, promoting best practices and disseminating these through the creation of networks of firms are also common features of other countries’ programmes (OECD, 2019j).

Building on these international practices and the assessment of its own initiatives, the Polish authorities could consider establishing a co-operation network to identify and disseminate best practices for stimulating a learning culture in the workplace. Employers, unions and sectoral training providers, with support from the government, could establish this network. The chambers of commerce and group-based interventions can be particularly important, especially SMEs, to share good management practices (Lacovone et al., 2019).

Figure 2.25. Management skills appear lagging, notably for domestic firms

1. Share of managers with at least upper secondary education scoring below level 2 in at least one of the PIAAC proficiency scales, i.e. literacy, numeracy and problem-solving in technology-rich environments.

2. Scores are a measure of management practices across 5 key areas of management: operations management, performance monitoring, target setting, leadership management and talent management. Scores are scaled from 1 (worst practice) to 5 (best practice), 2012-2015.

Source: OECD (2013), OECD Skills Outlook 2013 (database); N. Bloom, C. Genakos, R. Sadun and J. Van Reenen (2012), “Management practices across firms and countries”, NBER Working Paper, No. 17850.

Facilitating the immigration of skilled workers

Facilitating the immigration of skilled workers could play an important role in overcoming local skills shortages and improving SMEs’ internationalisation. Immigrants’ country and language knowledge may reduce uncertainty and improve the governance of foreign operations (Ottaviano et al., 2018). Over recent years, immigrants from Ukraine and other neighbouring countries have contributed to a surge in labour supply. They reached an estimated 5% of the Polish labour force in 2016, and their inflow helped cushion the decline in the working-age population that started in 2011.Immigration had an estimated contribution of about 11% of Poland’s economic growth over 2013-18 (Growiec et al., 2019). Yet, most Ukrainian migration is still short term and such strong migration inflows are unlikely to become permanent, leaving SMEs and other firms with potential large skill shortages in the medium term.