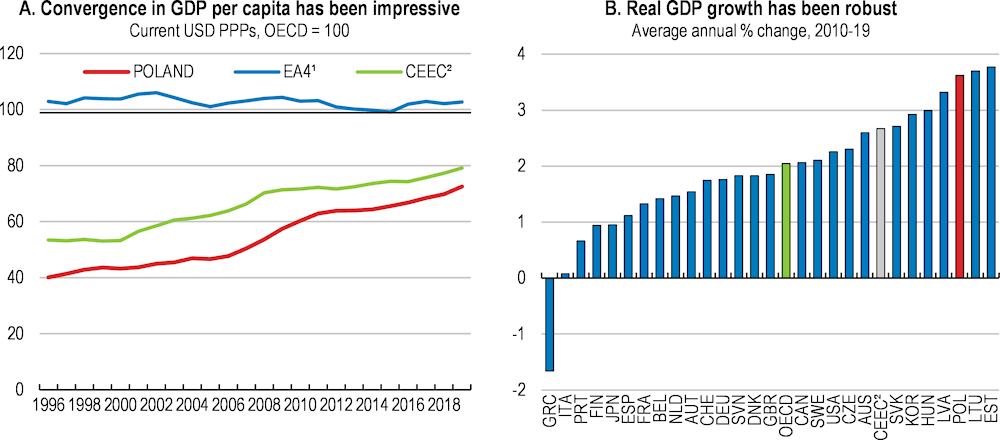

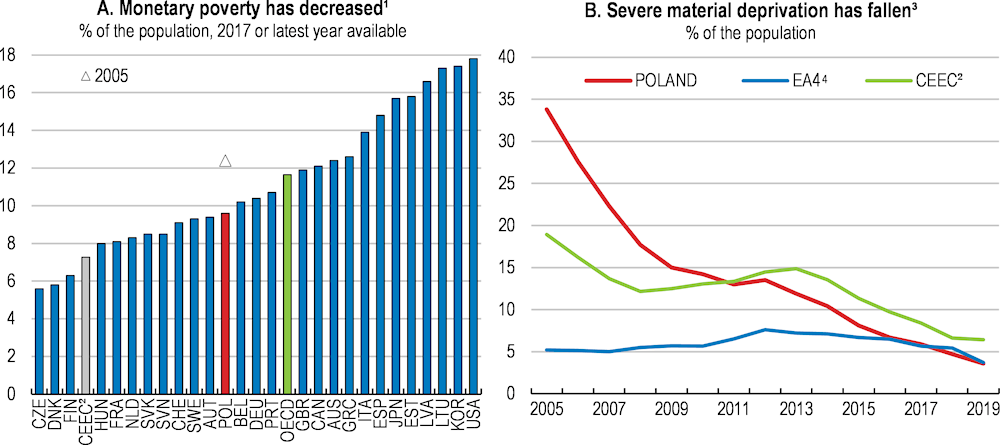

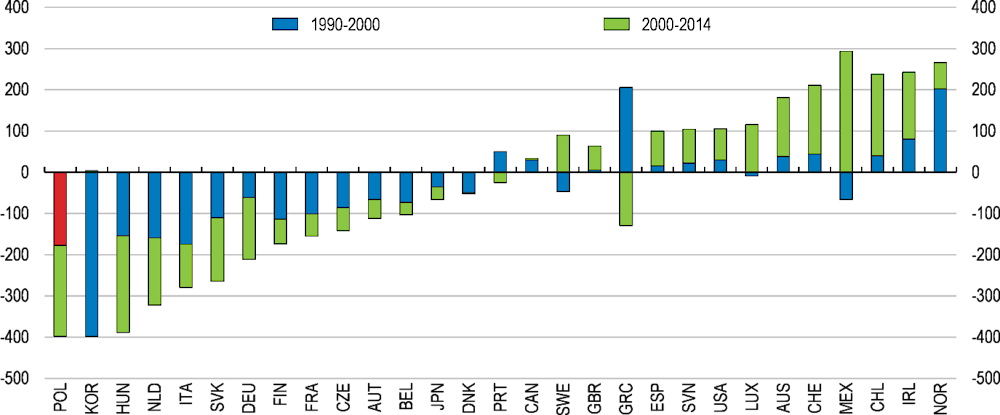

Poland has experienced strong economic growth over the past two decades. It has been very successful in integrating into global trade, not least thanks to its increasing role as an outsourcing destination for business services. The catch-up with average living standards in other OECD countries and regional peers has continued (Figure 1.1). Until the outbreak of the coronavirus, rising household incomes had contributed to more inclusive economic development, while poverty rates, inequality and the unemployment rate had declined (Figure 1.2).

OECD Economic Surveys: Poland 2020

1. Key Policy Insights

Ensuring continued convergence with higher living standards

Figure 1.1. The catch-up with living standards in other OECD countries has continued

1. EA4 is the average of Germany, France, Italy and Spain.

2. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Source: OECD (2019), OECD National Accounts and OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (databases).

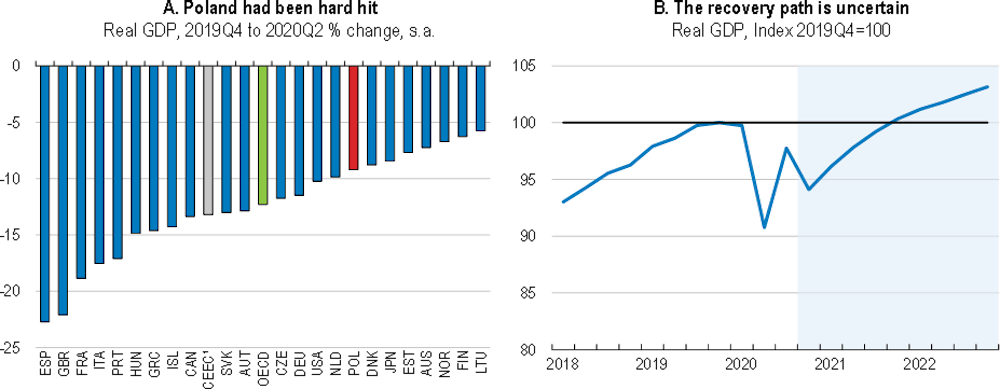

The coronavirus pandemic threatens these achievements made over the past decades. Though the initial shock has been lower than in many OECD countries, the economy is projected to see a marked contraction in economic activity in 2020 before partially recovering in 2021 (Figure 1.3). As confinement measures were lifted in May 2020, many businesses reopened and most workers returned to work, and consumption and production are rebounding from their low confinement levels. Yet, the pace of the recovery remains very uncertain: unemployment has risen slightly, renewed sanitary restrictions have been imposed in the autumn, uncertainty is high and global demand is still depressed.

Figure 1.2. Poverty had fallen until the onset of the crisis

1. Poverty rate after taxes and transfers, Poverty line 50% of median equivalised disposable income.

2. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

3. Severe material deprivation rate is defined as the enforced inability to pay for at least four items that are considered by most people to be desirable or even necessary to lead an adequate life.

4. EA4 is the average of Germany, France, Italy and Spain.

Source: OECD (2019), OECD Income Distribution Statistics (database); Eurostat (2019), "Severe material deprivation rate by age and sex", Eurostat Database.

Figure 1.3. The COVID-19 crisis has dented economic prospects

1. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Source: OECD (2019), OECD National Accounts and OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (databases).

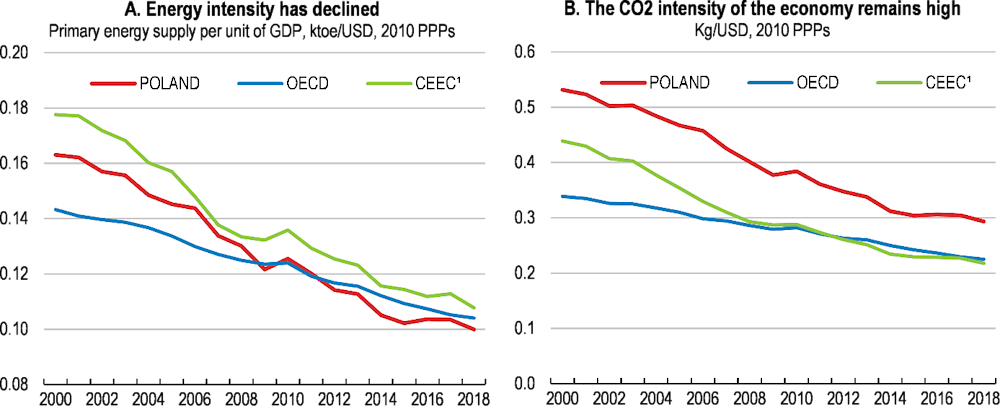

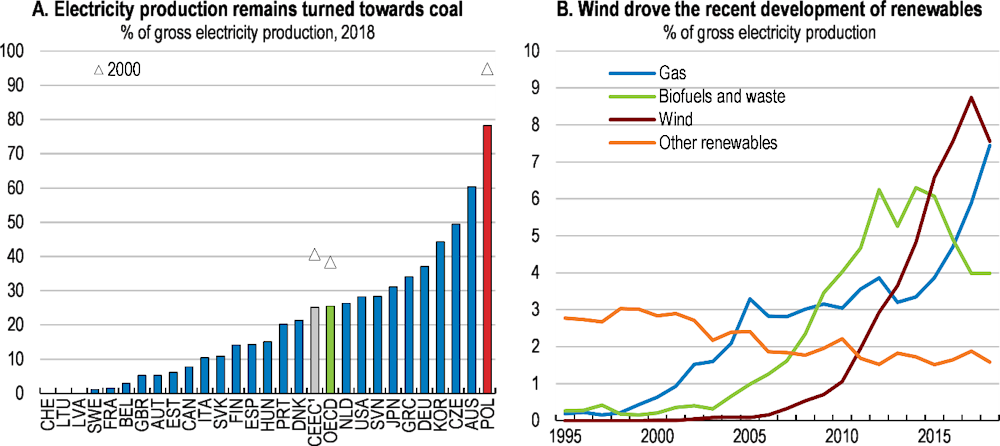

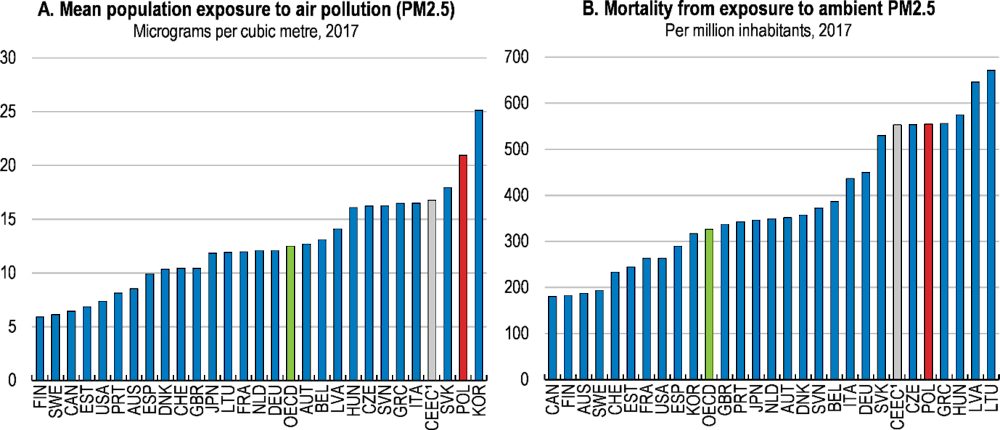

Policy support should remain available while the economy is still operating well below capacity. The shock will dent prospects for some industries, and many workers risk losing attachment to employers and facing difficulties in finding new jobs. The measures announced by the government and at the European Union level (Box 1.1) should also be used as an opportunity to ensure more sustainable and inclusive growth in the longer term. Poland faces pressing environmental issues, with high greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and air pollution. Persistent air pollution hurts people’s health, including by making individuals more vulnerable to acute respiratory illnesses like the coronavirus. More generally, Poland scores below the OECD average in terms of health status, housing adequacy, and labour productivity per employee, the latter being 23% below the OECD average in 2018, despite its fast growth. The country also faces significant demographic pressures owing to low fertility and past negative net migration rates, as well as a still significant gender participation and employment gaps, which will weigh on GDP growth and challenges the current labour-intensive growth model. This, together with the legacy of the coronavirus pandemic, will reduce Poland’s ability to finance pension and health-related spending in the longer term (Figure 1.4).

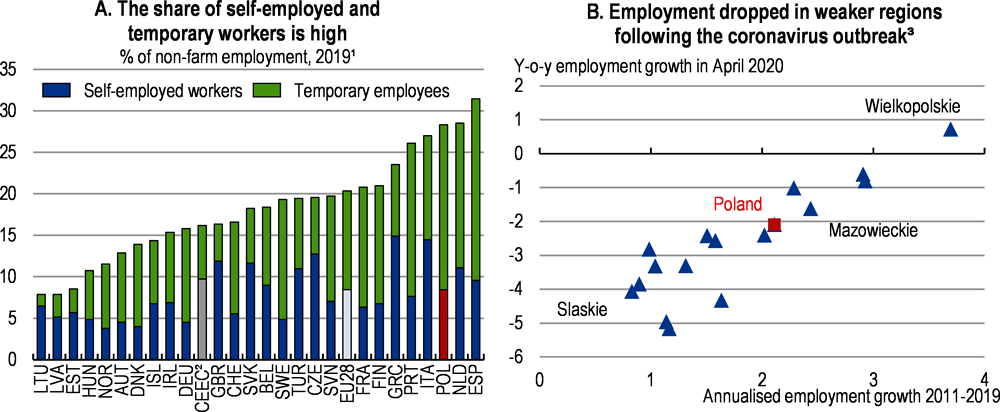

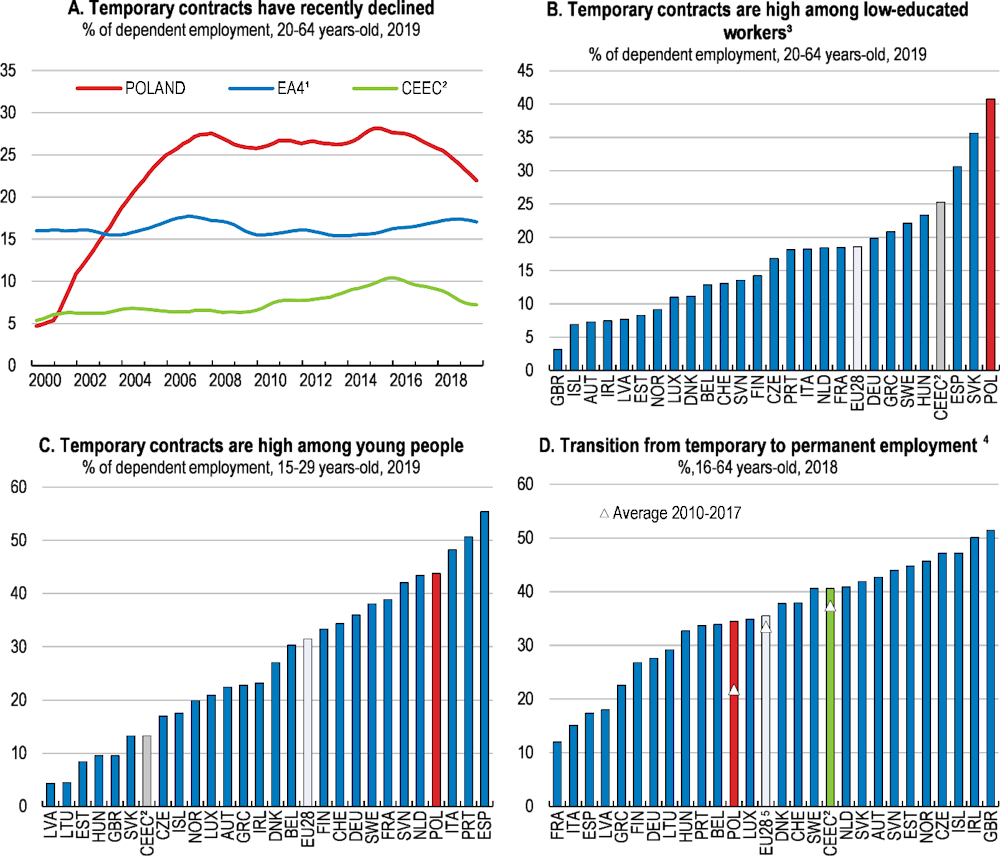

While government interventions have shielded most families from the brunt of the shock (Box 1.2, OECD, 2020a), the pandemic could raise inequalities. In particular, the high share of temporary and self-employed workers could suffer from the ongoing labour-market adjustments (Figure 1.6, Panel A). About 14% of temporary workers work on freelancing type of contracts and are not fully covered by workers’ rights and some contracts may not be covered by social security benefits. At the same time, many micro- and smaller firms have weak productivity and connections to local, national and international markets, which translates in low wages and job quality (Chapter 2). These firms may have less resilience and flexibility in dealing with the costs of the pandemic and changes in work processes, such as suppliers and export markets shocks, as well as the shift to teleworking and prevention measures due to the pandemic (OECD, 2020b).

Figure 1.4. The impact of population ageing is already visible

1. Eurostat baseline projections including migrations.

2. EA4 is the average of Germany, France, Italy and Spain.

3. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Source: Eurostat (2019), "Demography and Population Projections", Eurostat Database.

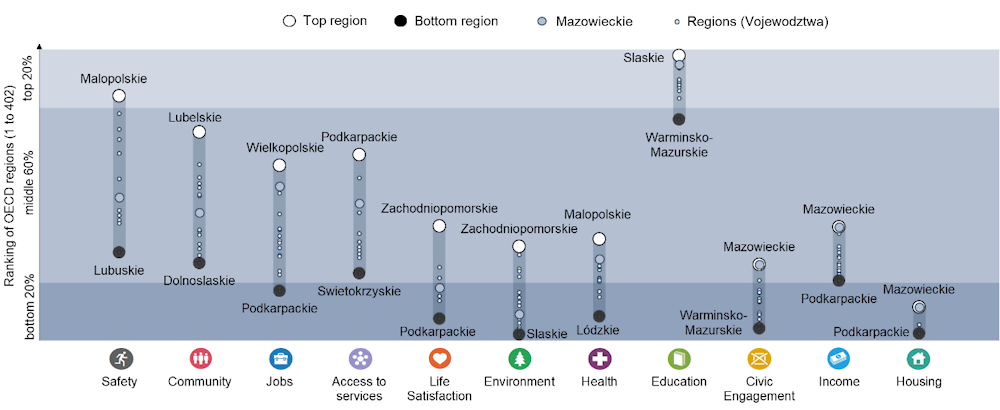

Disparities between regions could grow further. Disparities had already widened over 2011-16 (OECD, 2018a). Disposable income per household is 20% below the national average in some regions and 20% above in the capital (Statistics Poland, 2019a), and regional well-being indicators show significant gaps, despite some recent progress (Figure 1.5). Many small cities and rural areas still struggle with the outmigration of young people, and access to high quality public services such as healthcare, education or public transport (EC, 2019a). Following the coronavirus outbreak, in April 2020, the change in average paid employment ranged from -5.2% to +0.7% year on year (Statistics Poland, 2020), the most recent declines being much more pronounced in weaker regions (Figure 1.6, Panel B).

In this context, the key messages of this Economic Survey are:

There is high uncertainty about economic growth. Macroeconomic policies need to support the recovery and should be ready to act in case of further waves of contagion or unexpected downturn.

To sustain the recovery and more inclusive growth, policies should help job prospects of disadvantaged groups, and improve the links between SMEs and national and international markets.

More sustainable growth should be supported by policies focusing on innovation, the greening of infrastructure and increasing employment opportunities for women and older workers.

Figure 1.5. Regional disparities are high

Regional well-being, regional ranking, 20171

1. Relative ranking of the regions (refers to Poland’s 17 voivodeships – NUTS2-) with the best and worst outcomes in the 11 well-being dimensions, with respect to all 395 OECD regions. The eleven dimensions are ranked according to the size of regional disparities in the country.

Source: OECD (2019), OECD Regional Well-Being Database.

Figure 1.6. The crisis could widen inequalities

1. 2019 or average of the four latest available countries. Share of self-employment and temporary contracts among 15-64 employed workers, excluding agriculture, forestry and fishing.

2. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

3. Regions refers to Poland’s 17 voivodeships (NUTS 2).

Source: Eurostat (2019), "Employment, Labour Force Statistics series", Eurostat Database; OECD calculations based on Statistics Poland (2020), Average paid employment in enterprise sector (short-term data).

Box 1.1. Measures adopted to contain the coronavirus outbreak and support the economy

Confinement measures

Following the first coronavirus cases in early March, the government took rapid action to ban mass events, close schools and universities and move to online education, promote remote working, and progressively close large public venues. International air and rail passenger traffic was suspended and borders reinstated. On March 24, a strict lockdown was implemented. Leaving home was only allowed unless necessary to buy food and medicine, to consult a doctor or to go to work. In October, the authorities have applied renewed restrictions to curb the rebound of infections. The wearing of face masks in public places has been made mandatory, most schools have moved to distance learning, gyms and eat-in restaurants have closed again, while public gatherings, the number of customers in retail shops and cultural events have been limited.

Health care measures

As the March lockdown was progressively eased, the government made the wearing of masks mandatory in public spaces, unless a minimum two meters distance could be respected. The authorities unlocked more than EUR 23 million (PLN 98 million) for hospitals at a very early stage of the epidemic and an additional EUR 2.3 billion (PLN 10.1 billion) package for the healthcare sector was announced later on. Pharmacists were allowed to issue prescriptions directly and extra funds were made available for personal protection equipment to rescue and fire services, the police and the railway sector.

Fiscal measures

The government implemented a fiscal package as early as March 19. The package was revised three times since, with additional measures to support the economy. The new crisis fund in the State development Bank (BGK) is set to finance fiscal measures of around EUR 22.7 billion (PLN 100 billion) in 2020. In addition, EUR 2.8 billion (PLN 12.2 billion) have been earmarked to support local-government investment.

Income support for individuals

Parents whose children were affected by the closures of schools and early childcare facilities could apply for a care allowance. Firms could apply for a wage subsidy if experiencing difficulties, conditional on not dismissing workers for the duration of the benefit. Self-employed and workers on freelancing civil-law contracts could also apply for a subsidy up to 80% of the statutory minimum wage, exempted of social security contributions and taxes. The government also introduced a solidarity benefit of PLN 1400 per month, for up to three months, for workers who lost their job after March 15 and increased the monthly minimum unemployment benefits by 36% to EUR 272 (PLN 1,200) from September 2020.

Public subsidies, loans, loan guarantees and capital injections to businesses

The government announced the Financial Shield, an unprecedented loan and subsidies scheme worth EUR 22.7 million (PLN 100 billion) for firms to maintain liquidity and protect jobs. The programme managed by the Polish Development Fund (PFR) is dedicated to small, medium and large firms. The loans were awarded for three years, with zero interests, and repayments will only start in the second year. If firms keep their employees for the entire loan duration, up to 60% of the value of the support may be disbursed as a grant instead.

The State Development Bank (BGK) also increased its loan guarantees de minimis programme for firms by EUR 4.5 billion (PLN 20 billion) initially, and an additional EUR 91 million (PLN 400 million) in EU funds was redirected for further loan guarantees at the end of April. For small firms, the guarantee coverage was extended from 60 to 80% of the loans and a new liquidity guarantee fund in BGK was created for loans taken by medium and large enterprises.

The Polish Development Fund (PFR) increased its investments and financing operations on preferential conditions. The government also announced that further capital injections would be financed by drawing on available EU regional funds.

Taxes and social security contributions deferrals

Self-employed and micro-firms experiencing an important drop in revenues could apply for the deferral of taxes and the temporary cancellation of the payment of social security contributions. The measure was later extended to firms with between 10 and 49 employees.

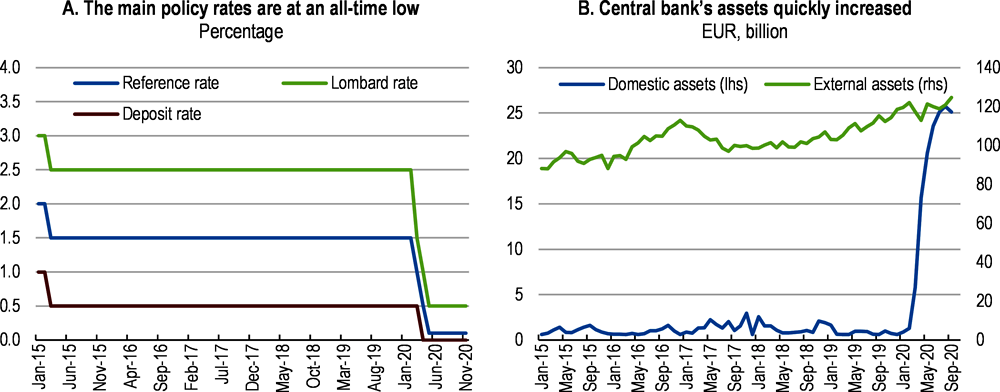

Monetary policy and prudential regulation

Monetary policy has been exceptionally accommodative. The National Bank of Poland (NBP) reduced its policy interest rate three times, from 1.5% in early March to 0.1% at the end of May. In addition, the central bank introduced repo operations to provide liquidity to the banking sector and announced it would purchase Polish Treasury securities and government guaranteed debt securities in the secondary market. The NBP introduced a programme to provide funding for bank lending to non-financial private enterprises similar to the ECB’s TLTRO.

Macro prudential regulation was eased. Reserve requirements were lowered from 3.5% to 0.5%, while the interest on mandatory reserves was set at the level of the policy rate (currently 0.1%). Following recommendations from the Financial Stability Committee, banks were released from the obligation to maintain the systemic risk buffer, and allowed to reduce the risk weight from 100% to 50% for some secured exposures on commercial real estate, which considerably increased their available capital. The Polish Financial Supervision Authority (KNF) introduced some flexibility in the classification of exposures and allowed banks to operate below the combined buffer requirement and the Loan-to-Capital ratio.

The “Next Generation EU” plan

The “Next Generation EU” recovery plan agreed among EU leaders in July 2020 reaches EUR 750 billion. After approval by the European Parliament and the Council of the legislative proposals that will create the financial instruments necessary to make “Next Generation EU” operational, the plan is expected to start being implemented from 1 January 2021. It will be financed through borrowing by the Commission on financial markets and repayments will take place over 2028-58. This plan is completed by the 2021-27 EU budget – which would itself reach EUR 1,074.3 billion – to a total of EUR 1,824.3 billion over 2021-27.

The “Next Generation EU” plan creates new financial instruments and is frontloaded over the coming years. The new Recovery and Resilience Facility concentrates most funds (EUR 672.5 billion, of which 312.5 in the form of grants and 360 in the form of loans) to help finance investment and reforms over 2021-23. In particular, grants of the Recovery and Resilience Facility are set to reach around EUR 23.1 billion for Poland (around 4.4% of 2019 GDP over six years). According to the foreseen allocation, the EUR-30-billion “Just Transition Fund” to support the transition towards a climate neutral economy could increase this amount to a total of around EUR 29.1 billion for Poland (5.5% of 2019 GDP) (EC, 2020).

Source: OECD (2020), COVID-19 Tracker; OECD (2020), Economic Outlook, June 2020 – World Economy on a Tightrope from Collapse to Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris; EC (2020), The Pillars of the Next Generation EU, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/3pillars_factsheet_0.pdf

The economy requires continued policy support

The economy weakened substantially

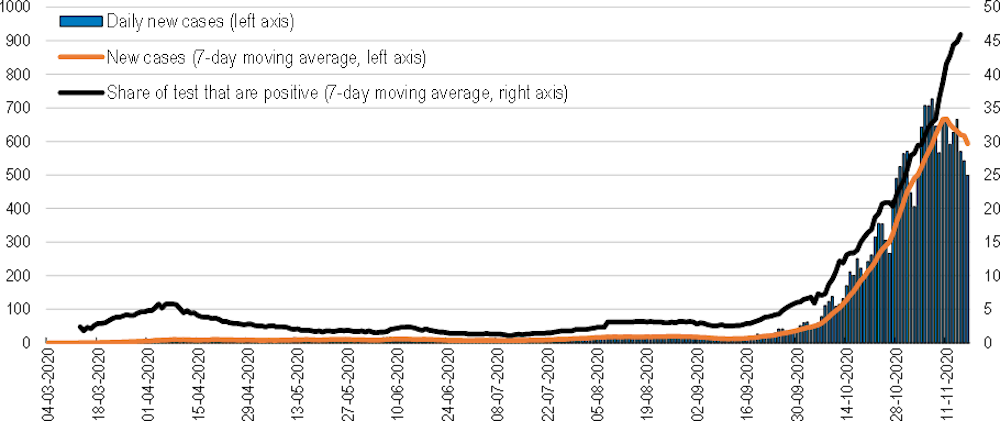

Following the first positive cases in early March, Poland’s daily new COVID-19 infections surged until the beginning of April (Figure 1.7). On 8 March, in the wake of the first confirmed cases, the authorities took rapid action to promote remote working, banned mass events, suspended schools and universities and progressively closed all cultural, accommodation, food and entertainment venues, together with shopping centres (Box 1.1). In mid-March, international air and rail passenger traffic came to a halt and border controls were reinstated. A few days later, the government declared a state of epidemic emergency and implemented tighter confinement measures. The swift introduction of these measures helped limit the extent of the contagion. However, new cases have again increased rapidly in the autumn and the authorities imposed renewed sanitary restrictions.

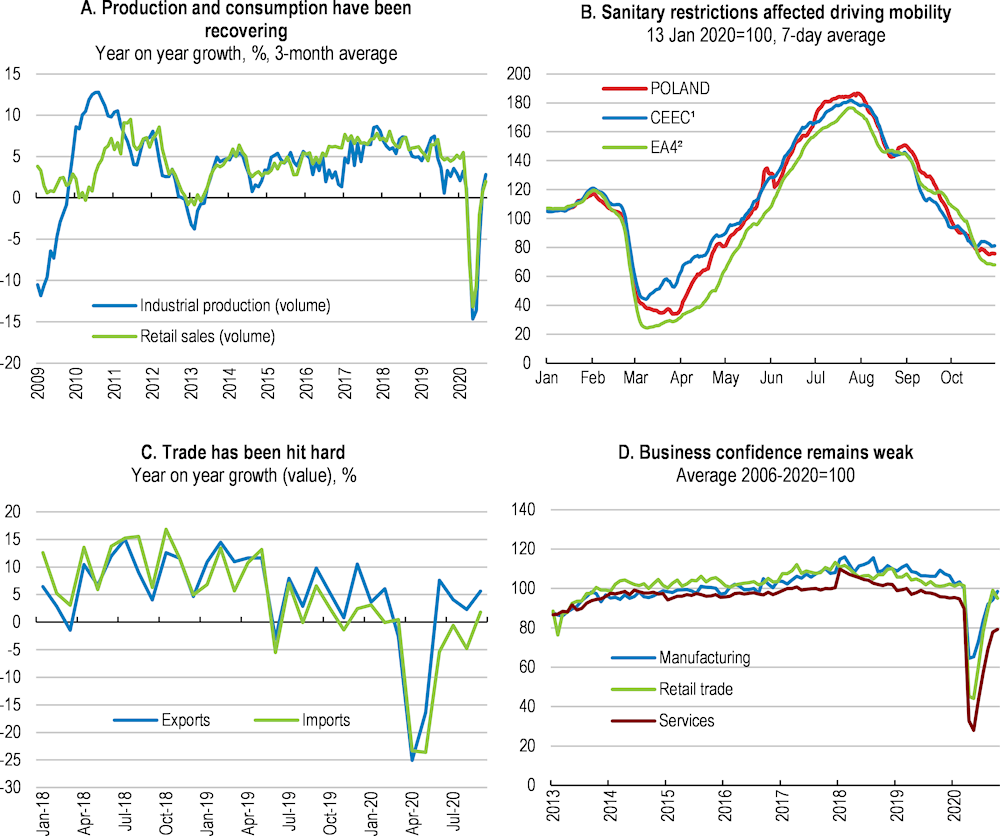

Industrial production and retail sales dropped sharply in April to below levels observed during the global financial crisis (Figure 1.8). The end of the two months lockdown in May allows activity to resume. Industrial production and retail sales have improved markedly. Accommodation, food services and the transportation sectors have been hit particularly hard. Mobility to retail shops and restaurants decreased by 28% compared to a normal period and retail sales in enterprises employing up to 9 persons dropped by 23% year-on-year in April. Exports and imports, that had been resilient during the first quarter, have also dropped sharply and bounced back thereafter. Business confidence remains relatively low in most sectors, notably services, and the recent resurgence of the pandemic has hurt confidence: domestic demand and mobility indicators started falling again with the renewed restrictions.

Figure 1.7. New COVID-19 cases have increased rapidly over the autumn

Daily new cases, per million of population

Source: Our World in Data, ourworldindata.org; OECD calculations based on John Hopkins University Centre for Systems Science and Engineering (JHU CCSE) database, and Statistics Poland (2020), Population Statistics.

Figure 1.8. Activity had bounced back after the initial Covid-19 sudden stop

1. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

2. EA4 is the average of Germany, France, Italy and Spain.

Source: Statistics Poland (2020), Short-term monthly indicators and Business confidence indicators; Apple (2020), Mobility trends reports.

A comprehensive fiscal package has cushioned the initial crisis impact

Fiscal policy reacted forcefully to the coronavirus crisis. The authorities have announced an anti-crisis package that foresees discretionary measures worth about 5.2% of GDP in 2020 (PLN 112.2 billion) in addition to the action of automatic stabilisers and the Financial Shield (Box 1.1). In a welcome move, this package aimed at preserving jobs by sustaining business liquidity, boosting healthcare spending and encouraging infrastructure investment during the recovery. The measures extended income support to numerous self-employed and temporary workers. To avoid widening inequalities due to the pandemic, the government enhanced transfers to local authorities and postponed loan repayments, for up to three months, for individuals having lost their job or main source of income. It also introduced a 3-month solidarity allowance payable to the most disadvantaged jobseekers and raised permanently unemployment benefits. A subsidised micro-loan facility supports the cash-flows of the smallest firms, while a loan guarantee scheme cover loans up to PLN 100 billion (4.4% of GDP) for all firms with no tax arrears, in proportion to their size.

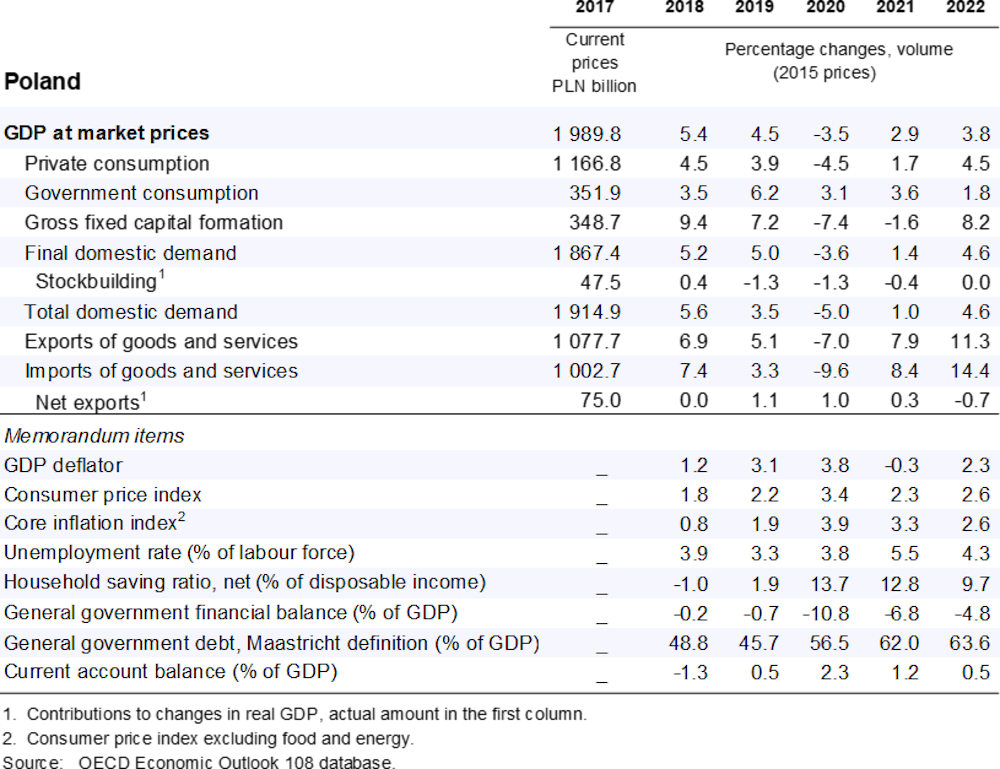

Postponed consumption and delayed investment decisions supported the initial recovery, but another outbreak and the associated sanitary restrictions, the expected rise in unemployment and uncertainties around the extent of global value chain destructions are denting household and business confidence. GDP growth will be limited to 2.9% in 2021, after a deep recession in 2020. In case of further epidemic outbreaks, associated with renewed containment measures, the recovery would further weaken. In addition, the slower euro area recovery, as well as a more pronounced deterioration of the outlook for the global automotive industry and business services, will reduce export prospects.

Table 1.1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

1. Contributions to changes in real GDP, actual amount in the first column.

2. Consumer price index excluding food and energy.

Source: OECD (2020), OECD Economic Outlook 108: Statistics and Projections (database).

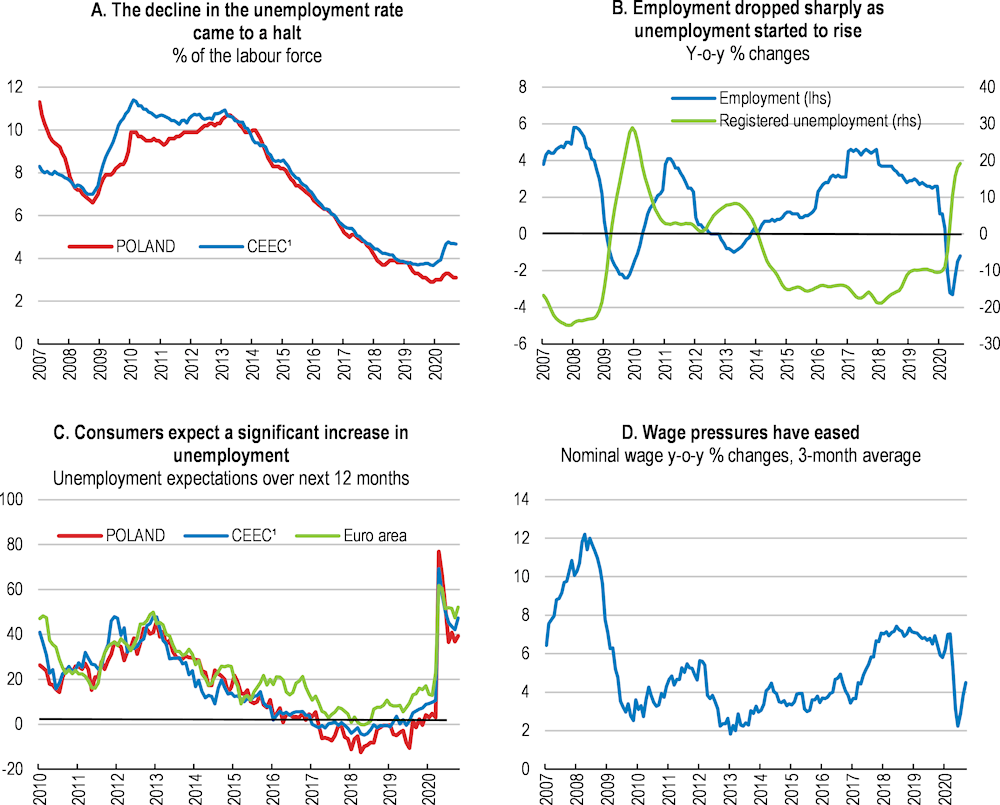

Ongoing labour market adjustments will have long-lasting consequences for households and firms (Figure 1.9). The initial shock has been smoothed by government measures, the lowering of working hours and the take-up of unpaid leaves (Statistics Poland, 2020). The number of employees and hours worked have slowly decreased in part due to the effect of the short-time work scheme. The rebound in employment after the initial lockdown has only been partial, and many workers will not be able to retain attachments to employers. These adjustments are set to intensify with the expected weak recovery, the associated likely dismissals and bankruptcies, as well as the significant reallocation and reskilling needs. The unusually large share of workers on temporary contracts or self-employment could bear the main costs. Small and micro enterprises, with little financial reserves, are also particularly at risk. Following the initial outbreak, many of them decreased wages to reduce short-term losses and maintain liquidity without having to resort to redundancies and the renewed autumn’s restrictions are set to weigh further on their financial situations.

Figure 1.9. Labour market adjustments are significant

1. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

2. Employment is the number of full-time equivalent jobs.

Source: Eurostat (2020), "Unemployment Statistics" (database); European Commission (2020), Business and Consumer Surveys (database); Statistics Poland (2020), Short-term monthly indicators.

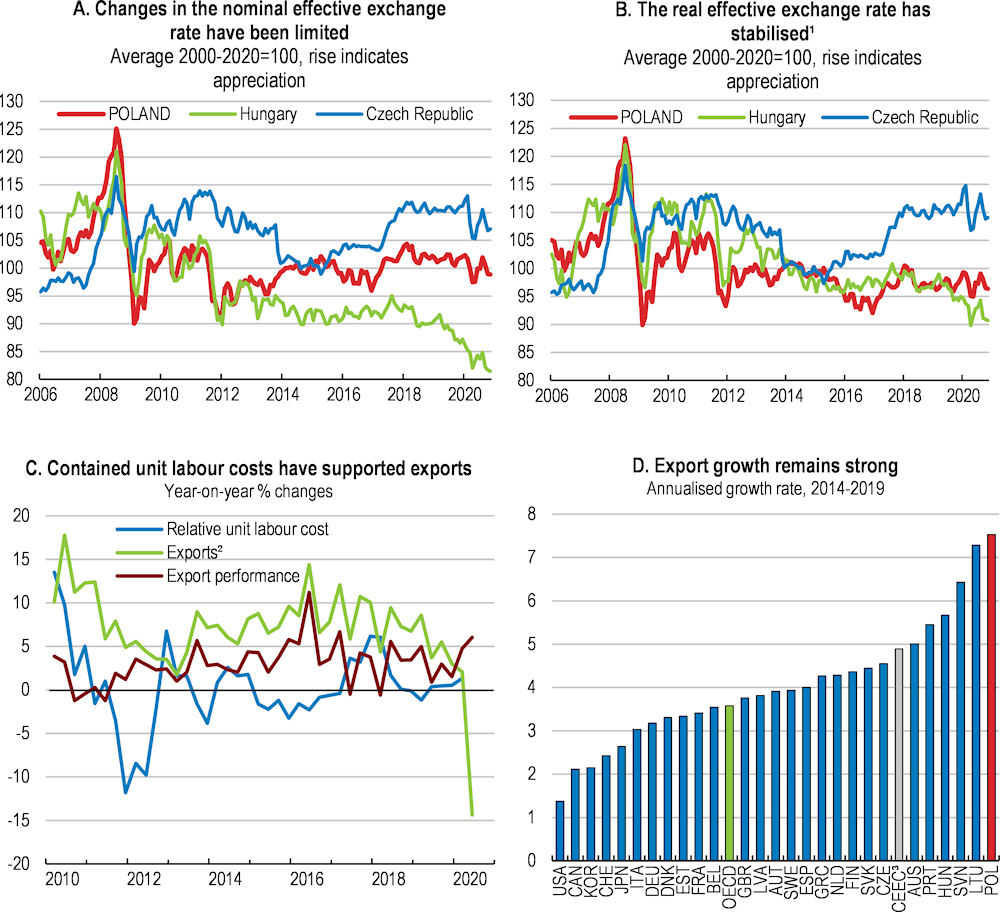

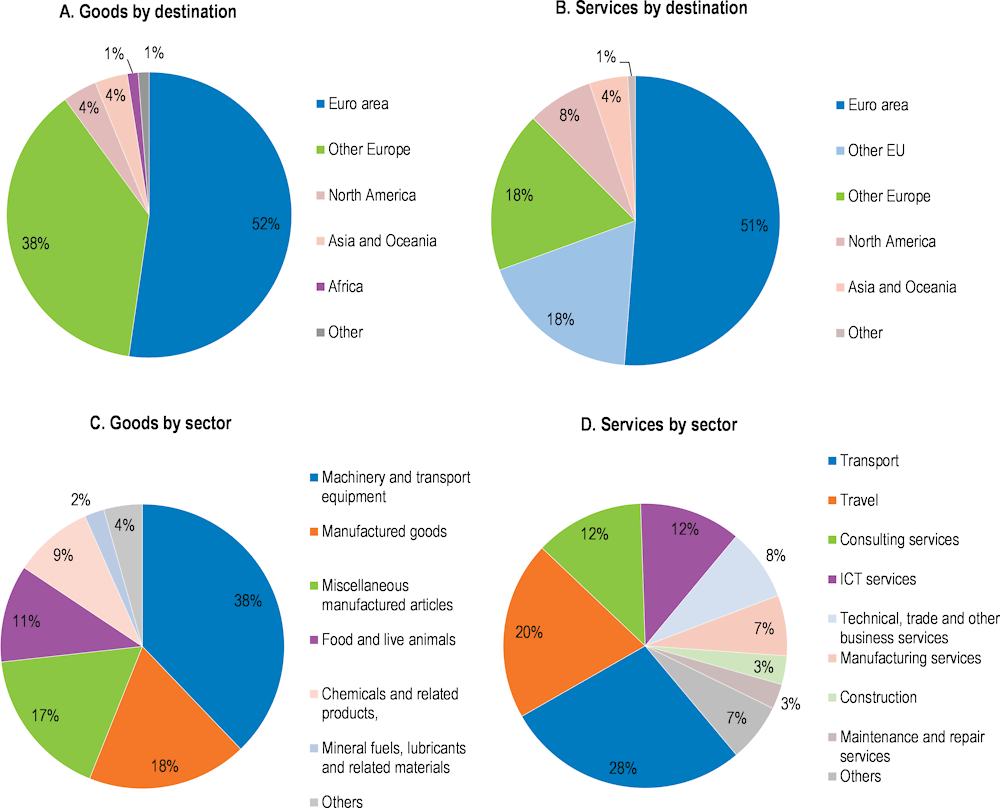

Exports are set to be relatively resilient to the depressed global economic conditions (Figure 1.10). Over recent years, Polish exporters resorted to diversification of trade ties to make up for the shrinking demand from the European Union or negative demand shocks from Russia and Ukraine. Poland’s exports of goods are well diversified in terms of composition, although goods exports remain mostly specialised in low- and medium-tech products and directed towards other European countries (Figure 1.11 and Chapter 2). Yet, unlike the sharp currency depreciation experienced during the global financial crisis, the global pandemic shock and the recent monetary policy easing (see below) have not changed much exchange rate levels so far.

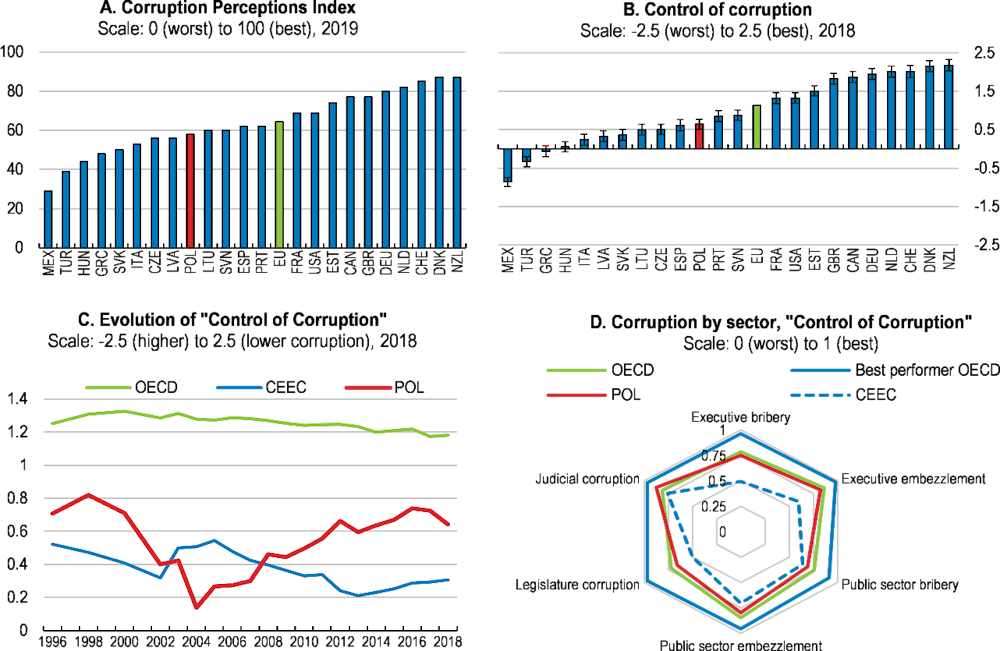

The short-term outlook is subject to particularly high uncertainty. New, longer and wider coronavirus outbreaks could hurt local and global economic conditions and be a drag on growth. Escalations of trade tensions risk further lowering the growth of exports and private investment. A further slowdown in the German car industry would also hurt exports and notably the automotive industry. Worsening perceptions about the evolution of judicial independence and the rule of law could also weaken business investment. On the upside, the large-scale roll-out of an effective vaccine commercialised already in 2021 could accelerate the pace of recovery by boosting external demand and investors’ confidence. A faster-than-expected recovery of household confidence could boost private consumption. A number of large possible shocks could also alter the economic outlook significantly (Table 1.3).

Figure 1.10. Exchange rate variations have been limited and export performance has so far been robust

1. Based on relative consumer prices.

2. Goods and services, volume.

3. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Source: OECD (2019), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

Table 1.2. Low-probability events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Shock |

Possible impact |

|---|---|

|

Long and globalised outbreaks of coronavirus |

New, longer lasting and more intensive outbreaks could spread much more widely than assumed. This would hurt global growth prospects and demand in key export markets. This could also constrain Poland’s productive capacity by reducing its labour supply and supply chains. |

|

A rapid increase in the global risk premium |

This would lead to higher domestic rates, and the zloty could depreciate, driving up interest payments and risks of fiscal policy slippages. |

|

Rise of protectionism and tensions in international trade |

Poland would be severely affected by a slowdown of its European partners in case of prolonged and heighted trade tensions. This would have adverse effects on exports and firm entry and undermine investors’ confidence, harming productivity and potential growth. |

Box 1.2. Key ongoing policies and reforms

Increasing social transfers: the July 2019 extension of the "500+" benefit granted an unconditional monthly benefit of PLN 500 (EUR 117) to every child aged 0-18. The “pension plus” scheme is a yearly one-off lump-sum pension payment amounting to PLN 1,100 gross in 2019 (EUR 249)and PLN 1,200 (EUR 281) in 2020.

Pension reforms: the Open Pension Funds (OFE) are set to be dismantled, and the funds transferred to private individual retirement accounts (IKE), or to the personal accounts at the Social Insurance Institution (ZUS). The authorities also set up voluntary Employee Capital Plans (PPK) in 2019. They aim at increasing long-term private savings and, in particular, may improve future pension adequacy.

Increasing tax expenditures for low-wage earners and younger workers: Since 2018, the tax-free income for PIT has increased, and the first tax rate has been reduced in October 2019 (from 18 to 17 percent). Young income taxpayers (up to PLN 85,528) have been exempted from the personal income tax in since August 2019 and tax deductible costs have more than doubled in October 2019.

Improving VAT compliance: Poland created a centralised data warehouse, merged tax administration, customs and fiscal control operations. It also improved modelling tools to better detect irregularities and facilitated information exchange with banks when suspicion of fraud.

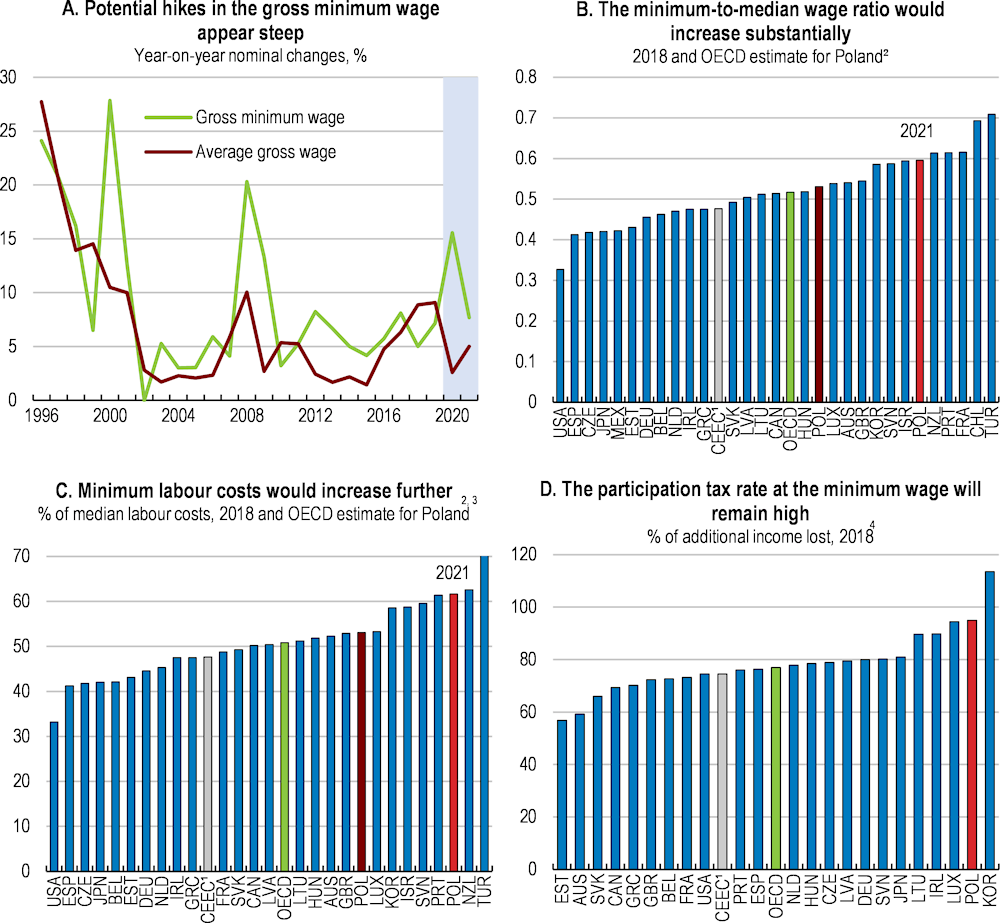

The government has increased the minimum wage. An increase of 15.6% took place in January 2020 and another increase of 7.7% will take place in January 2021 (to PLN 2,800).

The 2018 “Clean Air” and the 2020 “My energy” programmes aim at reducing air pollution from residential heating, improving the energy performance of buildings and increasing the use of small-scale renewable installations. Grants and loans are available for investments such as stove, window and door replacements, property insulation, and installation of renewable energy systems. The 2020 “My energy” programme will co-finance up to 50% of individual photovoltaic installations.

Increasing public health expenditures: Before the COVID-19 outbreak, the government had plans to increase public health-care spending to 6.0% of GDP in 2024 from 4.5% in 2015. Additional spending already occurred in 2020 as a response to the ongoing crisis.

Increasing some specific taxes: a new levy on soft drinks and some alcoholic beverages, the so-called “sugar tax”, and a tax on retail sales’ turnover are to be introduced in 2021.

Initiatives supporting SMEs (Chapter 2): The 2018 Business constitution and “100 Changes for Enterprises” aim at reducing the administrative burden, notably for SMEs and foreign investors. In addition, in 2019 the authorities lowered the reduced corporate income tax rate for SMEs to 9%.

Integrated Skills Strategy: The general part of the Integrated Skills Strategy (ZSU) has been adopted in January 2019. The detailed part is being developed with the support from the OECD.

Judicial reforms: In the context of the general pension reform, the authorities lowered the retirement age of judges and allowed the Ministry of Justice to retain selected judges, among other measures. The European Court of Justice ruled the proposed reform to be unlawful (EC, 2019) and the government has subsequently amended the retirement age of judges. Another reform, potentially allowing to dismiss judges for their court rulings, has been criticised by the Polish Supreme Court (2020) and the Council of Europe (2020).

Source: EC (2019), European Commission statement on the judgment of the European Court of Justice on Poland's Ordinary Courts law, European Commission; Council of Europe (2020), Poland- Urgent Joint Opinion on the amendments to the Law on organisation on the Common Courts, the Law on the Supreme Court and other Laws, Opinion No. 977 / 2019, CDL-PI(2020)002-e; Polish Supreme Court (2020), 24 January 2020.

Figure 1.11. Poland’s export structure is well diversified

Share of exports by sector and destination, 2019 or latest year available

Note: Data on good exports refer to 2019, while data on services exports refer to 2018. In Panel C, Others include crude materials, beverages and tobacco, animal and vegetable oils, and commodities and transactions. In Panel D, Others include R&D services, financial services, insurance and pension, construction services, and cultural services.

Source: OECD International Trade Statistics.

Monetary policy has been appropriately accommodative

Monetary policy has reacted forcefully and quickly to the emerging coronavirus crisis. The central bank cut its policy rate from 1.5% in early March to 0.1% at the end of May coupled with a narrowing of the interest rate corridor (Figure 1.12), strengthened banks’ liquidity through reduced reserve requirements, started an asset purchase programme – including state-guaranteed debt securities – and introduced TLTRO-type refinancing. These measures eased monetary conditions and smoothed the financing of the fiscal anti-crisis measures, as the yields of government bonds have declined markedly (NBP, 2020a). Statements also made clear that the central bank will continue to purchase government securities and government-guaranteed debt securities in the secondary market and will offer bill discount credit aimed at refinancing loans granted to enterprises.

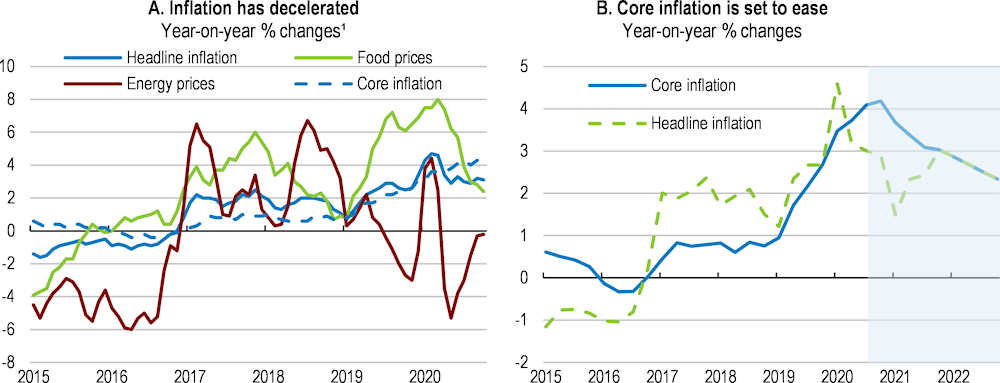

Headline inflation has sharply decelerated, driven by the reversal of earlier energy and food price hikes (Figure 1.13, Panel A). In October, headline inflation (as defined Statistics Poland) stood at 3.1% year on year, down by 1.6 percentage points since its February high. Decreasing oil prices and slowing food price growth have more than compensated increasing wholesale electricity prices, due to recurrent weaknesses in supply (OECD, 2016), and the end of the 2019-electricity price freeze for households in January 2020 (ERO, 2020). Yet, core inflation remains relatively high. This reflects lagged effects from administered price hikes, the mild zloty depreciation and the pass-through of the costs of new health-and-safety type procedures, as wage growth has sharply decelerated and unemployment has started to rise. OECD inflation and Central Bank’s projections for inflation are set to remain within the Central Bank’s tolerance band in 2021-21 (Figure 1.13, Panel B, NBP, 2020a and c). Wage growth is projected to ease further and the economy to recover slowly and at a very uncertain pace, as there are ongoing headwinds to activity from weak global growth, risks of more severe and longer-lasting coronavirus outbreaks and rising trade tensions.

Figure 1.12. Monetary policy has reacted forcefully to the crisis

Source: NBP (2020), Balance sheet of the National Bank of Poland – Assets - stocks in PLN million; Central bank interest rates; OECD (2020), Monthly Monetary and Financial Statistics (MEI) dataset.

Figure 1.13. Inflationary pressures have decreased

1. Harmonised indices.

Source: Eurostat (2019), "Harmonised index of consumer prices", Eurostat Database; OECD (2019), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

Under these circumstances, the current monetary stance appears appropriate. In responding to the coronavirus shock, monetary policymakers have enhanced and expanded their tools. Local currency bond yields fell significantly following the programme announcements, with little effect on exchange rates. The authorities have signalled that they are ready to keep interest rate at their historically low level for an extended period, and that they will continue to purchase government and government-guaranteed debt securities in the secondary market to strengthen the monetary policy transmission mechanism. Yet, monetary policy decisions should remain data-contingent and forward-looking, responding rapidly should economic conditions deteriorate (or improve) faster than expected. Given potentially limited room for manoeuvre, in case of an even more severe downturn, the authorities may consider adjusting large-scale asset purchases, including through the possibilities for expanding the range of eligible assets, and using of negative interest rates.

Risks to financial stability have increased and require close monitoring

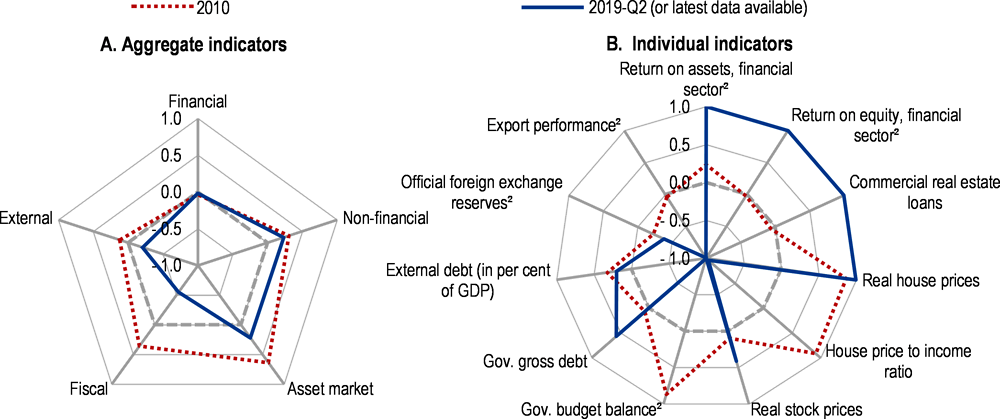

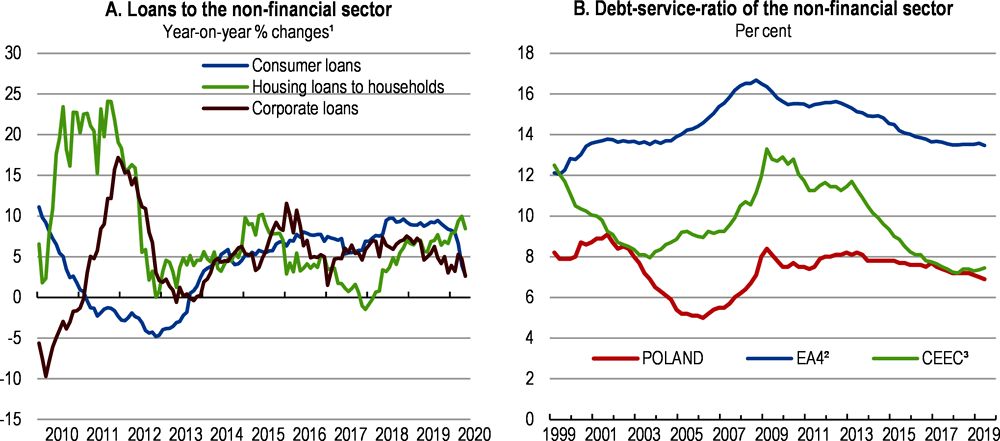

The coronavirus crisis raised several financial risks. Before the crisis, the financial system stood in relatively good condition, despite the increase of some vulnerabilities (Figure 1.14). Yet, a long-lasting decrease of employment and fall in corporate revenues would lower households and firms’ capacity to repay outstanding debts and translate into increased credit risk costs for banks (OECD, 2020a and 2020c). This risk is, however, reduced by massive fiscal support and monetary actions (Box 1.1). At the same time, high uncertainty and increasing risk aversion are having a negative impact on banks’ propensity to grant new loans, which could further exacerbate the liquidity position of businesses and their solvency (Figure 1.15, Panel A; NBP, 2020b). Yet, according to banks’ surveys, the decreased pace of new lending over 2020 has been caused rather by subdued demand than tightened credit standards.

Figure 1.14. Evolution of macro-financial vulnerabilities

Index scale of -1 to 1 from lowest to greatest potential vulnerability¹

1. For each aggregate macro-financial dimension, displayed in Panel A, the vulnerability index is based on a simple average of all indicators from the OECD Resilience Database that are grouped under that dimension’s heading. Indicator values are normalised to take values between – 1 and 1. They are positive when the last observation of the underlying time series is above its long-term average, indicating more vulnerability, and negative when the last observation is below its long-term average, indicating less vulnerability. Long-term averages are full-sample estimates calculated since 2000.

2. Inverted scales, higher values indicate higher potential vulnerabilities.

Source: Calculations based on OECD (2019), OECD Resilience Database, December.

The healthy position of the banking sector before the crisis and regulatory measures averted problems with banks’ liquidity and capital position so far. Despite historically low interest rates, macro-financial vulnerabilities had receded since 2010. The debt-service ratio of the non-financial corporate sector was low in international comparison (Figure 1.15, Panel B). Loan losses, the share of loans in arrears and impaired loans were decreasing (NBP, 2019). The banking system was also well capitalised and liquid (KNF, 2019; EBA, 2018). These accumulated buffers, as well as the release of the systemic risk buffer recommended by the Financial Stability Committee and the measures taken by the central bank to provide liquidity to the banking sector, such as lower reserve requirements, the introduction of repo transactions and structural market operations, have contained liquidity risk and the need to increase banks’ capital.

Notwithstanding the good aggregate indicators, caution is warranted. Bank share prices have declined, impeding their ability to raise funds from external sources if needed. There is heterogeneity across banks, with some smaller institutions that are more sensitive to shocks having suffered losses that significantly reduce their available capital (NBP, 2020b). Though non-performing loans have remained broadly stable until September 2020, the coronavirus crisis has increased the risks of non-performing loans and banks should use their profits to increase their capital buffers, for example by not distributing dividends, as recommended by the regulator.

Figure 1.15. The risk of a credit crunch has increased

1. Growth rate on the total number of loans.

2. EA4 is the average of Germany, France, Italy and Spain.

3. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech Republic.

Source: NBP (2020), Monetary and financial statistics (database); BIS (2019), Debt Service Ratios for the Private Non-financial Sector (database), Bank for International Settlements, Basel.

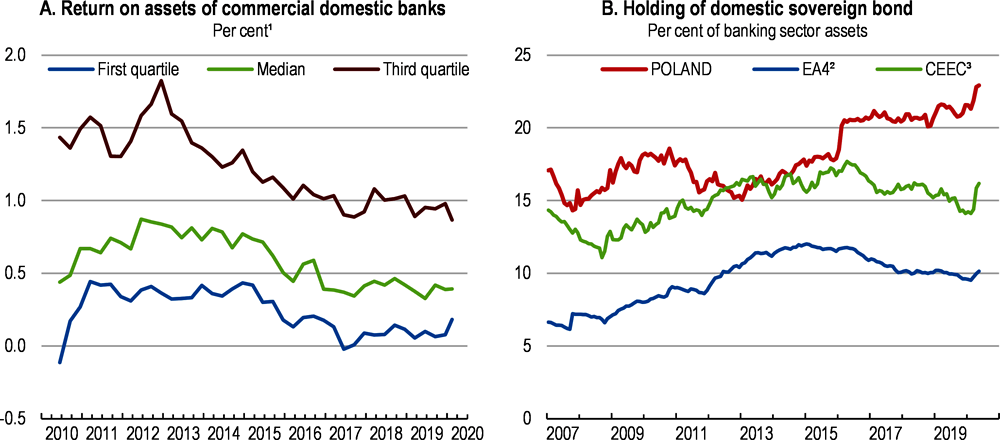

The crisis has worsened financial institutions’ profitability. Polish banks were already affected by global downside pressures on profitability (EBA, 2019), as well as domestic factors related to the asset tax introduced in 2016 and increased contributions to the bank-guarantee fund (Figure 1.16, Panel A; NBP, 2019). As demand for banking services and investment products fell during the lockdown, non-interest margins dropped, while lower interest rates reduced banks’ interest margin income. At the same time, higher provisions for credit risk lower banks’ profitability further. Further medium-term risks stem from the declining stock of foreign-currency denominated mortgages, as the ongoing rise of customer challenges and court disputes could negatively affect banks’ profitability if the conditions of particular foreign-currency denominated mortgages are deemed abusive (ECJ, 2019).

Sovereign-financial institution linkages have increased, exposing banks to potential negative feedback effects between the financial situation of the State and the banking sector. Before the pandemic, the state control of the financial system had already increased to around 40% of the sector’ assets, following the purchases of stakes by the authorities in two large banks in 2017 and a 2019 reform strengthening state involvement in nominations to the Polish Financial Supervision Authority (KNF). Banks have also significantly increased their holdings of sovereign bonds (Figure 1.16, Panel B). The 2016 bank asset tax incentivises higher holdings of government securities as such assets are currently exempted. Replacing the current bank asset tax with a tax on profits and remuneration would be less distortive (IMF, 2019).

Strengthening the regulatory framework would support financial stability. The Polish Financial Supervision Authority (KNF) is in charge of the banking sector supervision and its resources have increased in 2019. Yet, its independence remains potentially constrained. The governing members of the KNF should be selected solely based on their expertise and experience. The KNF should also have responsibility for the oversight of its human resources’ management, as well as for evaluating the supervisory effectiveness. In order to improve the effectiveness of early intervention in the case of troubled banks, the KNF should be able to execute bank insolvency assessments, without having to require an external third-party opinion (IMF, 2019).

Figure 1.16. Banking sector's profitability and holding of sovereign bonds

1. Annualised data.

2. EA4 is the average of Germany, France, Italy and Spain.

3. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech Republic.

Source: NBP (2020), Financial Stability Report - June, National Bank of Poland, Warsaw; ECB (2019), Statistical Data Warehouse (database), European Central Bank, Frankfurt.

Boosting the recovery while containing medium-term spending pressures

The crisis legacy will compound long-term challenges

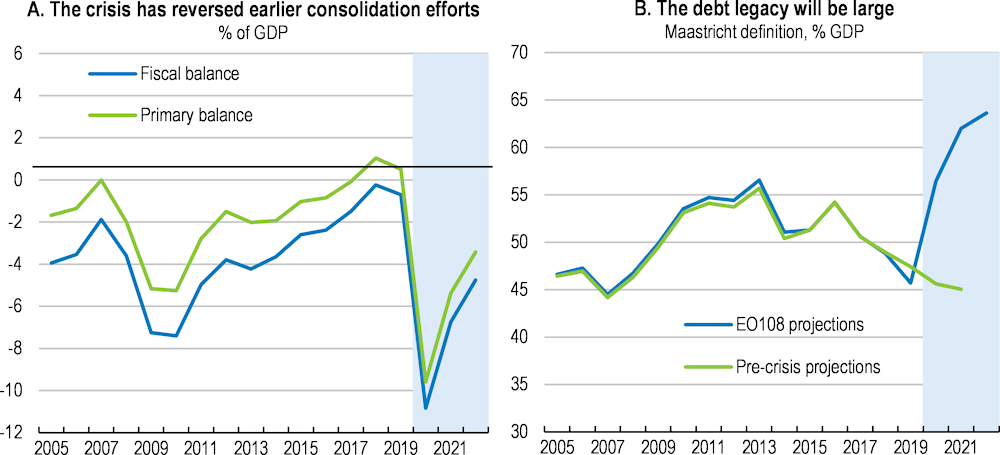

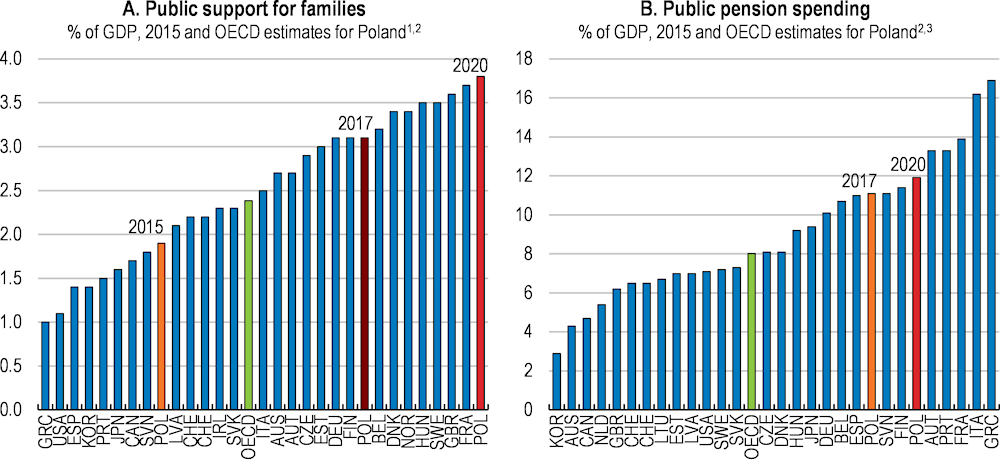

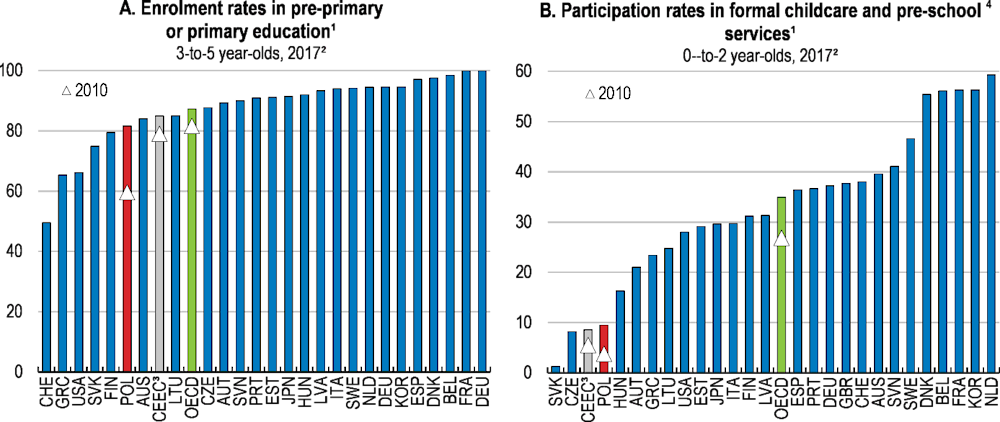

Before the crisis, the fiscal position was strong in the short term (Figure 1.17). The fiscal deficit had been reduced significantly since 2010 and the public debt-to-GDP ratio was set to decline further from its 2016 peak, bringing it well below the European Union average in 2021. This achievement owed to strong growth, better tax collection (notably through the successful elimination of tax loopholes) and low spending growth till recently. Yet, even before the crisis, the authorities had been raising social expenditures (Figure 1.18 and Box 1.2). In particular, the 500+ child benefit programme introduced in April 2016 (and its later expansion) and the reversal of the minimum retirement age reform (to the levels of 2012) implemented in October 2017 increased medium-term financing needs. Both measures are expected to cost more than 2% of GDP annually. The new child benefits has doubled public support for families to about 3.8% of GDP, well above most other OECD countries (Figure 1.18, Panel A). The additional payment for pension and the reversal of the retirement age reform are set to push public pension spending to close to 12.0% of GDP in 2020 (Panel B).

In the current environment of very low interest rates, which could be long lasting, high public borrowing levels might be sustainable if they finance growth-enhancing investments. Yet, the sharp temporary increase in the deficit in the response to the coronavirus crisis will increase the need for controlling medium-term spending pressures (Figure 1.17). Compared to the OECD November 2019 projections, the crisis will push 2021 Maastricht debt up by 17 percentage points of GDP to 62% of GDP. Long-term sustainability challenges are also significant. There are a number of reasons to expect further pressure on the fiscal balance in the longer run. Firstly, health and long-term care costs are set to rise by around 1.4% of GDP by 2050 (EC, 2018a). Secondly, infrastructure needs will remain strong to allow a transition towards a greener and more efficient economy, as bottlenecks remain in energy and transport infrastructure.

Figure 1.17. The fiscal response to the crisis has been substantial

Source: OECD (2019 and 2020), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

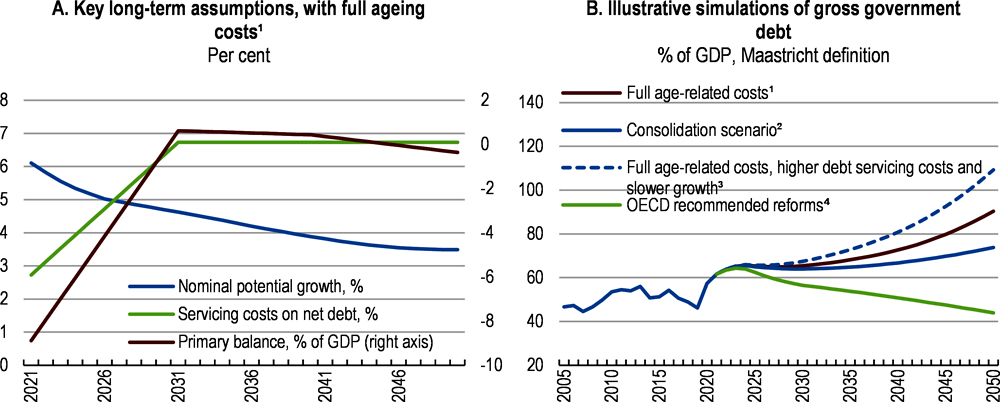

According to illustrative OECD simulations that are surrounded by particularly high uncertainty, Poland’s public debt – Maastricht definition – could increase to around 90% of GDP by 2050 if ageing costs and the legacy of a single coronavirus outbreak were not offset (Figure 1.19). Even taking into account Poland’s spending rule, which imposes to remain close to Poland’s Medium Term Objective of a structural balance of -1% of GDP, the offsetting consolidation efforts would not put public debt on a firmly declining path since ageing will progressively reduce the growth potential. In this scenario, due to the sharp increase in debt stock over 2020-21, the public debt would continue to increase to a level close to 74% of GDP in 2050.

Further strengthening the fiscal framework would help to ensure sustainability over the longer term. The current system requires public debt to be kept below 60% of GDP (national definition) according to the Constitution. In normal circumstances, the application of the 2013 spending rule should lead to a reduction of the deficit if one of the following three instances occur: the preventive net public debt-to-GDP thresholds – 43% and 48% – are crossed; the general government deficit exceeds 3% of GDP; or there are significant deviations from the medium-term budgetary objective. Since 2019, the budget process should also incorporate a medium-term (three years) perspective and provide guideline for future spending ceilings, which is welcome. The National Bank of Poland and the European Commission (through the Convergence Programme) issue opinions about the draft budget and the Supreme Audit Office (NIK) ensure ex-post control. Yet, Poland remains the only EU Member State without a fiscal council (EC, 2019a) and it would be helpful to have an independent institution make ex-ante assessment of the government’s fiscal plans and conduct long-term fiscal sustainability analyses (OECD, 2016).

Figure 1.18. Spending commitments on some social programmes are rapidly increasing

1. Poland’s public spending on family benefits of 2015, augmented with the costs of the family 500+ child benefits introduced in 2016 with mean testing and its full-year extension in 2020. The full-year costs associated with the 2018 Good Start programme and the 2019 Mother 4 plus scheme are also taken into account in the 2020 estimate. Other changes are not taken into account.

2. The 2020 GDP figures are based on the OECD pre-crisis projections (November 2019 Economic Outlook).

3. The 2020 estimate takes into account the pension plus scheme and the 2019 hike in minimum pension and indexation. The 2016 reversal of the retirement age increase is expected to cost 0.1% of GDP in 2020. Other changes are not taken into account.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2020), OECD Family Statistics and OECD National account (databases); OECD (2019), Pension at a Glance, OECD Publishing, Paris; and Republic of Poland (2019), Convergence Programme – 2019 Update, Warsaw.

Figure 1.19. Ageing will put further pressure on public debt

1. The key long-term assumptions build on Table 1.1 for 2019-21. They assume a long-term potential growth declining from 3.0% in 2021 to 1% in 2050 in line with OECD (2018). The GDP deflator and the debt servicing costs are set at 2.5% after 2026, and 6.7% of net debt after 2031. The primary balance converges from -0.3% of GDP in 2021 to +1.0% in 2031, consistently with Poland’s Medium Term Objective and fiscal rules. Yet, total ageing-related public expenditures (pensions, long-term care, health and education) are not compensated. These add 1.4 percentage points of GDP to annual government spending in 2050 (EC, 2018) and the primary balance is negative at -0.4% of GDP in 2050. Government gross financial assets are kept constant as a share of GDP.

2. The consolidation scenario assumes that the primary balance remains constant at +1.0% of GDP after 2031.

3. The net debt servicing costs increases to 7.7% in 2031 and remains stable thereafter. Compared to the key assumptions, potential growth declines faster and by an additional 0.25 percentage points in 2050.

4. The “OECD-recommended reforms” scenario adds the estimated effects of the reforms recommended in this Survey (Box 1.3) and the expected effects of some of the key recommendations as described in Table 1.6. The primary balance improves faster to 1.25% of GDP in 2026. Potential GDP improves by 5.6% after 10 years compared to the baseline scenario.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2019), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), November; OECD (2018), Long-term baseline projections; and EC (2018), "The 2018 Ageing Report - Economic and budgetary projections for the 28 EU Member States (2016-2070)", European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs.

Additional risks could weigh on the debt burden. General government contingent liabilities are substantial. They reached nearly 43% of GDP in 2018 (MF, 2019) and they have increased with the coronavirus crisis. Poland’s government guarantees and liabilities related to Public Private Partnerships are low in international comparison (Eurostat, 2020a). Yet, the liabilities of the numerous state-owned enterprises in the financial and non-financial sectors are large. Monitoring of state-owned enterprises and strengthening their governance should be aligned with OECD best practices (EC, 2019a; OECD, 2020d).

Ageing will put significant pressures on the quality of pension, health and long-term care

Before the coronavirus crisis, the financial sustainability of the pension system appeared assured, based on long-term projections. Yet, it would be at the expense of a gradual decline in the level of pension compared to working wages over the longer term. This poses a risk of old-age poverty and many Poles are for this reason concerned by financial security in old age. They also feel that they do not have access to good quality long-term care and healthcare (OECD, 2019a). Reforms need to be implemented that go beyond the sole financial sustainability concerns to ensure efficient and adequate expenditures in the pension, health and long-term care sectors.

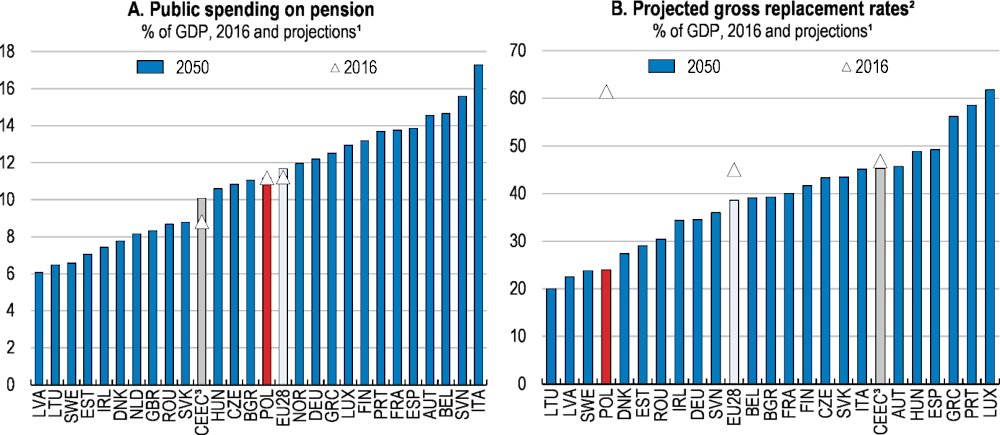

Reforms are needed to reduce risks of old-age poverty and boost employment

Public expenditures on pensions appear broadly under control over the longer term. Despite one-off increases in 2019-20, public pension spending is set to remain close to the European Union average at about 11% of GDP (Figure 1.20, Panel A). Public expenditures on pensions would remain broadly stable until 2050 according to European Commission’s projections (EC, 2018a). The financial sustainability of the pension system has been ensured by high standard contribution rates and a steep decrease in replacement rates (Panel B) driven by the transition to pensions based on lifetime contributions and the indexation of future pension mostly on prices (rather than the wage bill). This would offset the rapid population ageing. Yet, in the absence of further improvements in labour market outcomes and longer contributory periods, replacement rates are expected to become among the lowest in the OECD.

The recent introduction of an auto-enrolment private occupational savings scheme (PPK) could somehow improve this bleak prospect. The net household saving rate has declined over the long term to around -1.0% of disposable income in 2018. PPKs could increase future pension prospects by adding another component to the pension system if they succeeds to rebuild confidence in private pensions, which was undermined by the reversals of the mandatory funded scheme (OFE) (OECD, 2019b). From July 2019, large companies must enrol their employees into PPK with a standard contribution of 3½ percent of their gross wage financed through employer (2 percent) and employee (1.5 percent) contributions. The State also finances top-ups. Smaller companies followed from 2020 and public entities and the smallest firms are set to be covered in 2021. The participation of employees in large companies was 40%. The authorities expect to cover 75% of employees and inject into capital markets about 0.7% of GDP annually (EC, 2019a). Moreover, in 2019, the authorities increased the minimum pension (after a first hike in 2017), pension indexation and the coverage of women with more than four children through unconditional cash transfers (RSU). One-off benefit for all pensioners in 2019 and 2020 at the level of 0.5% of GDP annually, the so-called pension plus scheme (Box 1.2), are also boosting retirees’ incomes.

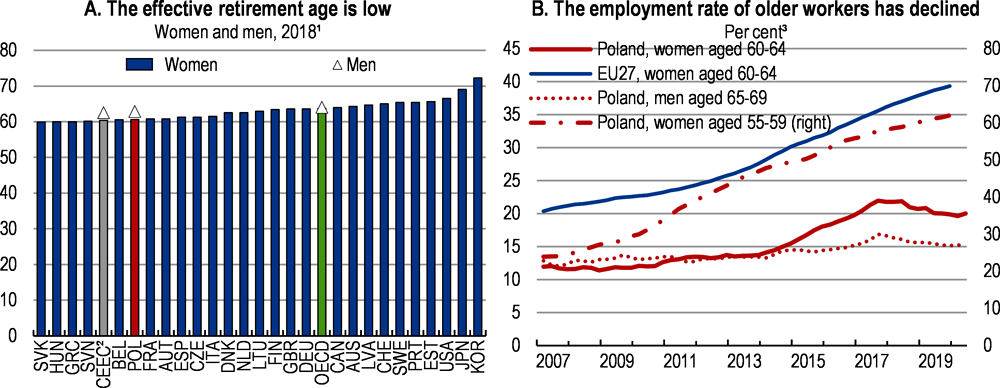

Employment rates for workers close to retirement (54-64) and the combination of work and pension have made rapid progress, but old-age poverty risks are still set to increase over the longer term, notably for women. While the average effective retirement ages both for men and for women has increased until 2018, they remain relatively low and the employment rates of 60-64 women and 65-69 men have decreased since 2018 (Figure 1.21). This is likely the consequence of reversing the 2013 retirement age reform to 60 for women and 65 for men in late 2017, as life expectancy at 50 years old has increased by 20 months over 2010-18 (Eurostat, 2020b). Indeed, in many studies, the statutory pension age is a powerful focal point that tends to have a strong effect on retirement decisions beyond any financial incentive effects (Cribb et al., 2016). Combined with the high share of temporary contracts and self-employed with low contributions and associated pensions (OECD, 2019b and below), these risk raising old age poverty and the share of pensioners who have no more than a minimum pension. Women, whose pension eligibility depends on a particularly low statutory retirement age, tend to benefit from lower replacement rates and are the most at risk (Bledowski et al., 2017; Tyrowicz and Brandt, 2017): their average age at labour market exit today is among the lowest in the OECD.

Figure 1.20. A steep decline in replacement rates is set to contain pension expenditures

1. European Commission projections (2018).

2. Gross replacement rates are measured as the very first pension benefit relative to the last wage before retirement.

3. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Source: European Commission (2018), "The 2018 Ageing Report - Economic and budgetary projections for the 28 EU Member States (2016-2070)", Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs.

A continued increase in the effective retirement age, in line with progress with life expectancy in good health, and improved working opportunities for women and older workers are crucial for labour market participation and the level of pensions. The pension system provides increased benefits for those postponing retirement beyond the statutory retirement age. Moreover, yearly letters and counsellors in regional offices inform and advise workers about their pension situation and the potential benefits of delaying their retirement. Yet, harmonising employment protection for all age groups to avoid disincentives to hiring older workers, who are currently better protected, could raise their employment prospects (OECD, 2015). Raising and equalising the statutory retirement ages for men and women and linking it to healthy life expectancy, as in many other OECD countries, such as Denmark or Portugal, would also help to take into account improvements of health conditions of older workers and accelerate the increase in effective retirement age. Efforts to strengthen job-search assistance and training programmes, and to reduce discrimination for older workers will also be needed.

Existing preferential pension schemes imply fiscal costs and reduce the mobility of workers between sectors. Special pension expenditures affect more than 22% of current pensioners and amount to 2.6% of GDP (EC, 2018a). In particular, the special social insurance system for farmers (KRUS) based on flat contributions and subsidised at a cost of around 0.8% of GDP, is hampering labour mobility and contributing to hidden unemployment in agriculture, though the share of those working in agriculture has decreased. Although they may be partly justified by hazardous working conditions, the special pension rules of for miners appear substantially more generous than the general rules. Similarly, survivor pension schemes could be reviewed to increase incentives to work at older age and reduce their costs. Indeed, the ratio of the deceased partner’s pension awarded to the survivor, at 85%, is among the highest in the OECD, and greater than the estimated ratio needed to sustain the surviving spouse’s living standards (OECD, 2018d). Progressively scaling back these programmes would allow to boost employment and inclusiveness.

Figure 1.21. Old-age work is low and declining

1. The average effective age of retirement is calculated as a weighted average of (net) withdrawals from the labour market at different ages over a 5-year period for workers initially aged 40 and over. In order to abstract from compositional effects in the age structure of the population, labour force withdrawals are estimated based on changes in labour force participation rates rather than labour force levels. These changes are calculated for each (synthetic) cohort divided into 5-year age groups.

2. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

3. 4-quarter moving averages.

Source: OECD (2019), Pensions at a Glance 2019: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris; Eurostat (2020), "Labour Force Survey Statistics", Eurostat Database.

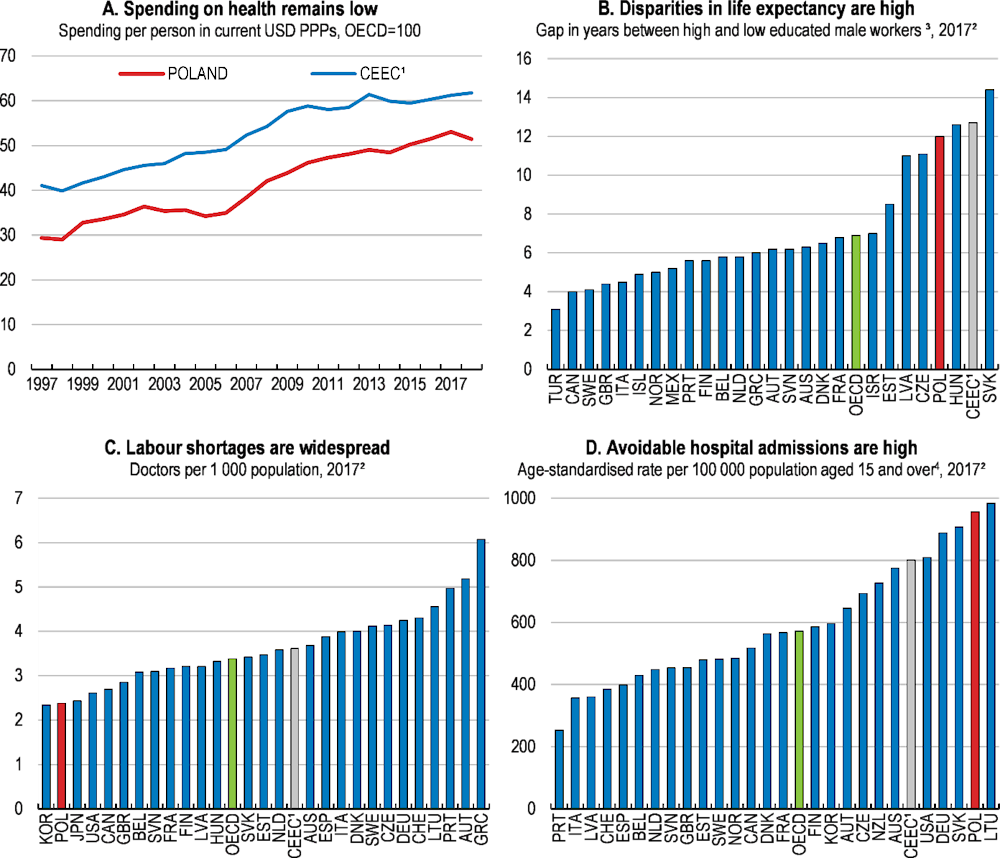

Containing the necessary increase in health and long-term care spending

Though early containment measures curbed the contagion of the pandemic, the healthcare system suffers from several weaknesses. Spending on healthcare is relatively low. At 6.3% of GDP in 2018 (among which 71.8% financed through mandatory public schemes, i.e. 4.5% of GDP being publicly funded), it is only around 50% of the OECD average in per capita terms (Figure 1.22, Panel A). This leads to relatively poor health outcomes: amenable mortality, i.e. mortality that could have been avoided through appropriate health care interventions, is above the EU average (OECD/EOHS, 2019). As such, the planned increase in public health financing to a minimum of 6% of GDP by 2024 is welcome. To prepare for a potential second coronavirus outbreak, the priority should be to ensure sufficient resources to boost intensive care capacity and allow for successful mass testing and isolation. Ageing will also add pressure to the health care system in the longer term, as its efficiency is suffering in particular from a high dependency on hospital care. Its coordination could be improved through a more efficient referral system and shorter waiting lists.

Strengthening primary care would avoid an excessive reliance on costly hospitalisations. The number of physicists is low, notably for generalists and avoidable hospital admissions are high (Figure 1.22, Panels C and D). The lack of general practitioners and nurses also effectively limit access to healthcare, notably for poor people living in rural areas. It is partly caused by inadequate remuneration. The general practitioner annual salary in 2016 was by far the lowest among OECD countries with available data. The same problem applies to nurses, whose salaries are second lowest only to Hungarian nurses. To deal with this problem, the authorities have introduced a national long-term policy on nursing and midwifery in 2019, thereby significantly increasing the number of schools for nurses, and raising the wages of nurses and midwives. Yet, developing, as planned, an integrated healthcare strategy to allocate the forthcoming increase in public spending could go a long way to address these issues, if it gives more prominence to primary care, prevention and e-health services.

Figure 1.22. The health sector suffers from numerous weaknesses

1. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics, except in Panel D where Hungary is missing.

2. Or latest available year.

3. Gap in life expectancy at age 30 between highest and lowest educational level, by sex.

4. Sum of avoidable admissions for asthma, COPD, congestive heart failure and diabetes.

Source: OECD (2020), OECD Health Statistics (database).

Equity is also a pressing concern. Differences in life expectancy by educational attainment are high (Figure 1.22, Panel B). Behavioural risk factors, including dietary risks, tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption and low physical activity, account for almost half of all deaths in Poland (OECD/EOHS, 2019), and the costs of air pollution are substantial (see below). Most of these risk factors are more common among people with lower education or income (Wojtyniak and Goryński, 2018). Preventive care accounts for only 2.3% of total spending, and could do much to close these gaps. Further attention needs to be paid to policy tools such as food and health standards, marketing bans or fiscal instruments such as taxes or subsidies. The 2017 creation of a national centre to promote healthy nutrition and physical activity in the population and the 2020 tax hikes on tobacco and alcohol use, as well as additional charge for sugar-sweetened beverages, are welcome moves. There is also a need for further information campaigns to promote good diet practices and strengthen vaccination rates, notably for people over aged 65.

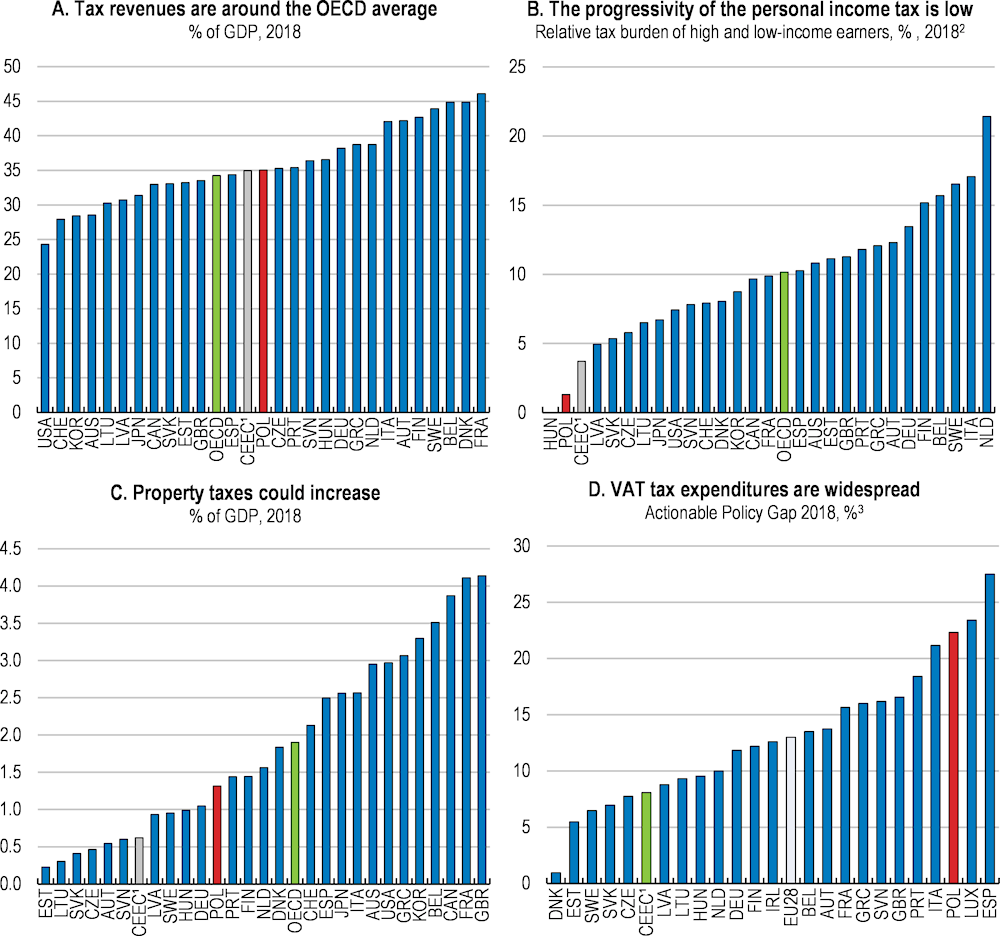

Improving the tax system

Tax reform should support the recovery and inclusiveness and, once the economy is back to a firmly growing path, help to finance increasing spending needs and improve environmental outcomes. In the short term, lower tax rates on labour, notably for low- and middle-income households, would help to strengthen the employment recovery and social cohesion. Over the longer term and insofar as it is necessary, raising additional revenues should be done in the most inclusive and the least growth distortionary manner possible. A streamlining of the large tax expenditures would help in this regard. Indeed, the tax-to-GDP ratio is already in line with the OECD average (Figure 1.23, Panel A) and the tax wedge is relatively high, suggesting that efficiency gains and careful implementation are crucial to limit the necessary raise in some spending items. The government plans to continue to finance higher spending mainly by reducing tax fraud and boosting tax compliance, together with an increase in consumption taxes (Table 1.4). Indeed, efforts to improve VAT compliance have been very successful so far, as the losses due to tax evasion may have been reduced by about 25% in 2017. Yet, this was also partly linked to the favourable economic cycle (EC, 2019a).

Improving the redistribution of the tax system

There is room to make personal income tax fairer and decrease the tax wedge for low-income workers to boost inclusiveness and employment (Figure 1.23, Panel B). The contribution of the progressive personal income tax to overall revenues is low in international comparison (OECD, 2018c). The 2017 introduction of a degressive non-refundable tax credit helped to raise the system’s overall progressivity (EC, 2018e). The government also lowered the first tax rate and exempted some young workers (those aged under 26 and with gross labour income below PLN 85 528 annually, around EUR 19 992) from the personal income tax in August 2019, and increased tax deductible costs for employees in October 2019 (Box 1.2). The 2017 personal income tax credit and the lowering of the bottom tax rate are welcome. Yet, the targeting of the youth created substantial age-based threshold, which could lead to higher employee screening and lower tax compliance.

Several measures could raise the progressivity of income and property taxes without endangering growth prospects. Firstly, there is room to strengthen the personal income tax credit. The full amount is available only to very low-income families (in 2019 the threshold was 13% of the average gross wage). Thus, it mostly affects single part-time workers and low-income families subject to joint taxation (Browne et al., 2019). Secondly, there are four regimes for paying taxes and social-security contributions for self-employed workers. The main one is based on shares of the (projected) average wage, notably for health and unemployment insurance contributions. Some of them pay social contributions based only on the minimum wage and a flat-rate personal income tax. These low costs compared to workers on permanent contracts runs risks for job quality of low-skilled workers (see below). Thirdly, once the economy is on a firm growth path, higher property taxes, which contribute relatively little to overall revenues, would be a complement to such reforms (Figure 1.23, Panel C). This could be done by establishing market-value-based property taxes (rather than based on area), by taxing capital gains on investment properties and by increasing taxes on vacant land and properties in urban areas. Such measures would improve inclusiveness, as housing tax revenue fell relatively evenly over the income distribution (Boone et al., 2019), and make the tax system more neutral vis-à-vis other types of investment and thus improve resource allocation (OECD, 2018f).

Once the recovery is firmly underway, the high number of reduced VAT rates and exemptions will require careful examination (Figure 1.23, Panel D). Poland applies reduced VAT rates to a number of goods and services, such as food, confectioned food and hygiene products, newspapers and books, restaurant and hotel services, water supply, housing repairs and some transport services (CASE/IAS, 2019; OECD, 2018vat). In a welcome step, the authorities are simplifying the system of reduced rates to limit uncertainty about their application. Yet, limiting the reliance on reduced rates could allow for lowering the relatively high statutory rate of 23%, while still increasing tax revenues. These would also allow for a more inclusive structure of taxation. Indeed, reduced rates often benefit higher-income households or firm owners, sometimes disproportionately, for example in the case of the reduced VAT rate on hotels and restaurants, as shown by VAT tax cuts on restaurants in France (Benzarti and Carloni, 2019). Lower-income households could be more efficiently reached through the personal income tax system or targeted social transfers, which have increased but remain low in Poland.

Figure 1.23. Tax revenues are around the OECD average, but could be more redistributive

1. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republic.

2. Difference between the average income tax rate between a single persons at 67% and 167% of average wage.

3. % of theoretical VAT liabilities. The actionable VAT gap takes into account reduced rates and exemptions, but exclude exemptions on services that cannot be taxed in principle, such as imputed rents or the provision of public goods by the government (CASE/IAS, 2019).

Source: OECD (2020), OECD Tax Statistics and OECD Taxing Wages (databases); CASE/IAS (2019), Study and Reports on the VAT Gap in the EU-28 Member States: 2019 Final Report, Report TAXUD/2015/CC/131 for the Directorate General Taxation and Customs Union, Center for Social and Economic Research and Institute for Advanced Studies.

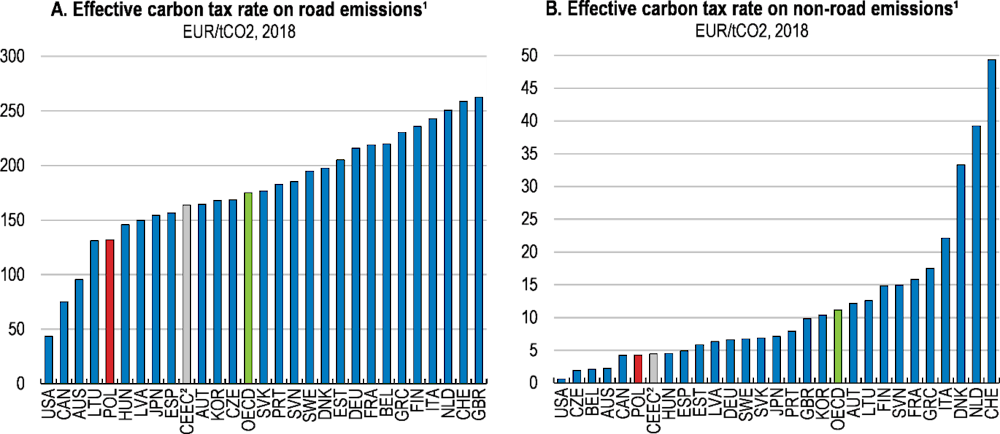

Strengthening environmental taxation

During the recovery, it is essential for stimulus measures and new investment to be aligned with ambitions on climate change, biodiversity and wider environmental protection (see below). Over the longer term, the phasing out of fossil fuel subsidies is a crucial step towards improving environmental and health outcomes. In 2015 only 15% of CO2 emissions from energy use were priced above 30 EUR/tonne, which is the low-end estimate of carbon cost today (OECD, 2018b) and effective taxes on energy use are also low (OECD, 2019c). As in other OECD countries, tax rates on energy use are relatively higher in the road sector, but they are low or absent in the residential sector and the electricity excise tax rate is low. Major exemptions from energy taxes are in place, such as exemptions from tax on coal in the agriculture sector and for households’ consumption or exemptions from coal and gas excise duty offered to some energy intensive industries (OECD, 2019c). The government should develop a strategy to phasing them out, while ensuring that any impact on energy poverty is alleviated.

Once the recovery is firmly underway, more effective carbon pricing would ease the energy transition (Figure 1.24). Around 48% of Poland’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions were covered by EU-wide emissions trading system (ETS) with a price of allowances around 25 EUR/tCO2 in 2019. Yet, effective carbon taxes – i.e. the sum of explicit carbon taxes and fuel excise taxes, net of applicable exemptions, rate reductions and refunds – that complement the ETS system currently fail to provide broad-based carbon price signals (OECD, 2019c). Broadening the tax base would contribute to mitigation of GHGs emissions and air pollution, while raising revenues in the short-term that could be used to finance environmental projects. Though CO2 emissions from road transport remain relatively low, transport emissions per inhabitant have more than doubled over 1997-2017. Poland is one of very few OECD countries without a specific CO2-related vehicle tax. Moreover, diesel is taxed at a lower rate than petrol. Such taxes would need to be accompanied with transitory social measures to improve their acceptability. For the same reason, part of their proceeds could be used to subsidise low-income households when they purchase less polluting cars or heating systems, for example, as was done recently for electric car purchases.

Electricity retail prices should be allowed to increase. In 2019, Poland capped retail electricity prices through a cut in the tax rate on electricity and a decrease in transition fees and electricity tariffs. This cap applied to all electricity consumers in 2019H1 and was later restricted to households, SMEs, local authorities and hospitals. The authorities also compensated electricity trading companies for the difference with market values. This slowed down the transition to greener alternatives for households that were supported through additional programmes (Box 1.2). In a welcome move, the cap on electricity prices was removed in 2020, but the regulator refused high price hike for households in 2020 that could compensate for the increasing production costs and wholesale electricity prices. Before the crisis, plans were to combine the electricity price hike for households with mean-tested transfers towards poorer households in 2021. If well-designed, this could help achieve the environmental goals while avoiding to put an excessive burden on energy affordability for lower-income households (Flues and van Dender, 2017).

Figure 1.24. Tax-based carbon price signals are weak

1. 2018 tax rates as applicable on 1 July 2018. CO2 emissions are calculated based on energy use data for 2016 from IEA (2018), World Energy Statistics and Balances. Emissions from the combustion of biofuels are included. Effective carbon taxes are not the only price-based climate policy instrument. The European Union’s ETS, for instance, covers most emissions from electricity generation and in industry; allowance were traded at approximately EUR 25 in 2019. Carbon price signals are thus somewhat more widespread than the Figure suggests. The scale of the horizontal axis differs between Panel A and Panel B. In Chile, the average effective carbon tax on non-road emissions is due to the Green Tax.

2. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Source: OECD (2019), Taxing Energy Use 2019: Using Taxes For Climate Action, OECD publishing, Paris.

Illustrating the fiscal effects of government’s and OECD-recommended reforms

The proposed tax and spending reforms give the government a choice of options to improve the structure of public spending and revenues in the medium run. These options would also make room to boost growth-enhancing investment, for example, public expenditures on R&D. This is quantified in an illustrative manner in Table 1.4.

Table 1.3. Government structural fiscal plans from 2018 to 2025 and OECD’s recommendations

Estimated effects on the 2025 fiscal deficit (% of 2025 GDP)1

|

Panel A. Key government spending plans until 2025 |

% of GDP |

|---|---|

|

The 2019-20 extension of the child benefits programme (500+), independently of households’ income level. |

0.8 |

|

The 2018-19 strengthening of other childcare programmes (the 2018 Good Start programme and the 2019 Mother 4 plus). |

0.1 |

|

Additional health-care spending: 1.3% of GDP. |

1.3 |

|

Additional pension spending due to the reversing of the 2013 retirement-age increases. |

0.5 |

|

Increase in R&D spending not financed by EU funds. |

0.3 |

|

Panel B. Key government revenue plans until 2025 |

|

|

Further improvement in tax compliance. |

-1.5 |

|

The implementation of a tax on digital firms and the retail tax. |

-0.1 |

|

New tax expenditures in personal income tax (new threshold, increased tax-free allowance, exemption for young taxpayers) introduced in 2020. |

0.4 |

|

The 2020 increase of alcohol and tobacco taxes and the new sugar tax. |

-0.15 |

|

The reform of the second pillar (OFEs) will bring higher social security contributions. |

-0.1 |

|

Panel C. Total effect of government plans on the fiscal deficit |

1.55 |

|

Panel D. OECD-recommended reforms |

|

|

Rebalancing long-term and childcare spending towards long-term care, the development of childcare facilities and lower-income families: 0% of GDP. An increase of spending on childcare and long-term care services of 1.4% of GDP could be financed by eliminating child tax credits and family benefits that existed before the introduction of the 500+ benefit programme, together worth 0.6% of GDP, and scaling back and reforming the 500+ extension, worth 0.8% of GDP. In net terms this would leave the level of spending unchanged by 2025. |

0 |

|

Increasing training for the low-skilled and unemployed workers by 0.1% of GDP. |

0.1 |

|

Increase in public spending on higher education and research: a 0.5% of GDP increase in public funding for universities would bring Poland’s spending on tertiary education roughly into line with the United Kingdom and the Netherlands2. |

0.5 |

|

A reduction of the tax wedge for low-skilled workers equivalent to 0.4% of GDP. |

0.4 |

|

Strengthening the progressivity of the personal income tax by increasing revenues by 0.6% of GDP (16% of the gap with the OECD average) and using these revenues to reduce general social security contributions for low-wage workers. |

0 |

|

Reducing VAT revenue shortfalls due to reduced rates and exemptions: 0.8% of GDP2. |

-0.8 |

|

Increasing environmental and property taxes. |

-0.85 |

|

Aligning the special pension regime for farmers and the specific rules applied to miners with the general regime. Gradually increase in the statutory retirement age to 67 for women and men phased in over 2020 to 2040. |

-0.9 |

|

Panel E: Total effect of OECD proposals on the fiscal deficit |

-1.55 |

|

Panel F. Total effect of government plans and OECD proposals on the fiscal deficit (=Panel C+Panel E) |

0 |

1. Excluding temporary support measures in response to the coronavirus crisis. Positive numbers indicate a deterioration of the fiscal balance. Numbers may not add to totals because of rounding. Measures enacted before 2018 and that do not have a staggered impact on the deficit are not taken into account.

2. These recommendations are taken from the 2018 Survey.

Source: OECD calculations based on Republic of Poland (2019), Convergence Programme – 2019 Update, Warsaw and OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Poland 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Table 1.4. Past OECD recommendations on fiscal policy and pensions

|

Main recent OECD recommendations |

Actions taken since the 2018 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Evaluate the effects of the pension reform, and make corrections such as aligning male and female retirement ages and indexing them to healthy life expectancy. Inform the public about the impact of working longer on pension income. |

Yearly letters are sent to inform about future pensions and a network of local counsellors has been developed. Social campaigns and online pension calculators have been developed. The Council of Ministers adopted an official evaluation of the 2016 reform. |

|

Strengthen environmentally related taxes, limit the use of reduced VAT rates and exemptions, and make the personal income tax (PIT) more progressive, e.g. by introducing a lower initial and more intermediate tax brackets and ending the preferential tax treatment of the self-employed. |

Since 2018, the tax-free income for PIT has increased. The first tax rate was lowered in October 2018 and young workers (aged under 26 and with labour income below PLN 85,528) are exempted from the personal income tax since August 2019. Tax deductible costs for employees were increased in October 2019. |

|

Redesign and increase the least distortive taxes, by establishing market-value-based property taxes and by taxing capital gains on investment properties. |

No action taken. |

Improving productivity, employment and well-being

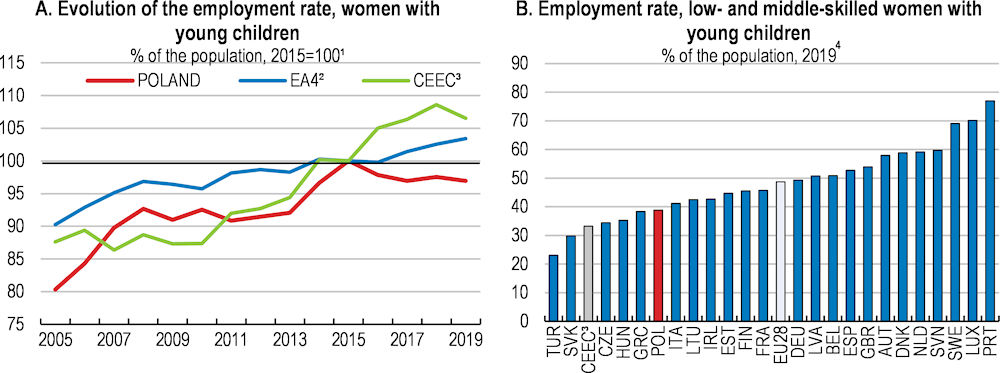

To support the recovery and return to a sustainable growth path, Poland needs to boost innovation and productivity gains, notably in smaller firms. Progress towards more resilient and inclusive growth is held back by low skills, pervasive labour market inefficiencies, and difficulties of small and young dynamic firms to grow (Chapter 2). According to illustrative OECD simulations, structural reforms could increase GDP by 5.6% after 10 years (Box 1.3). The largest gains would come from reforming pension arrangements, developing childcare facilities and increasing the employability of low-skilled workers, through a reduction of their tax wedge and strengthened activation measures.

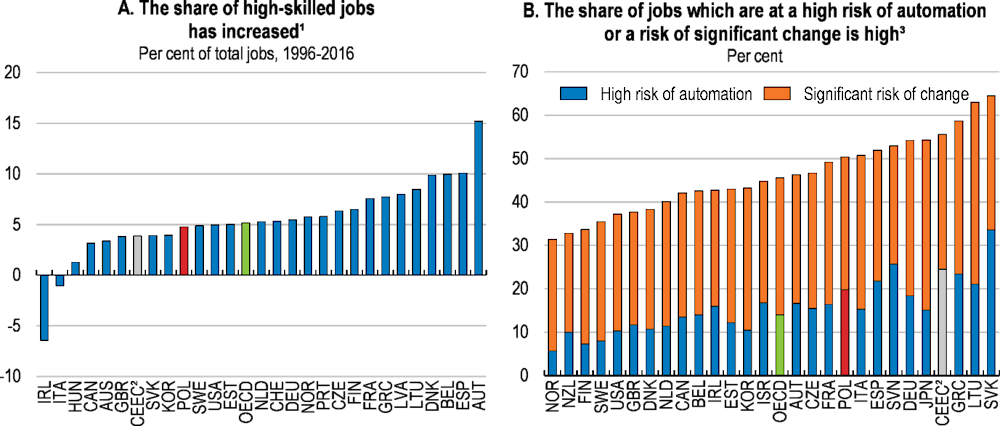

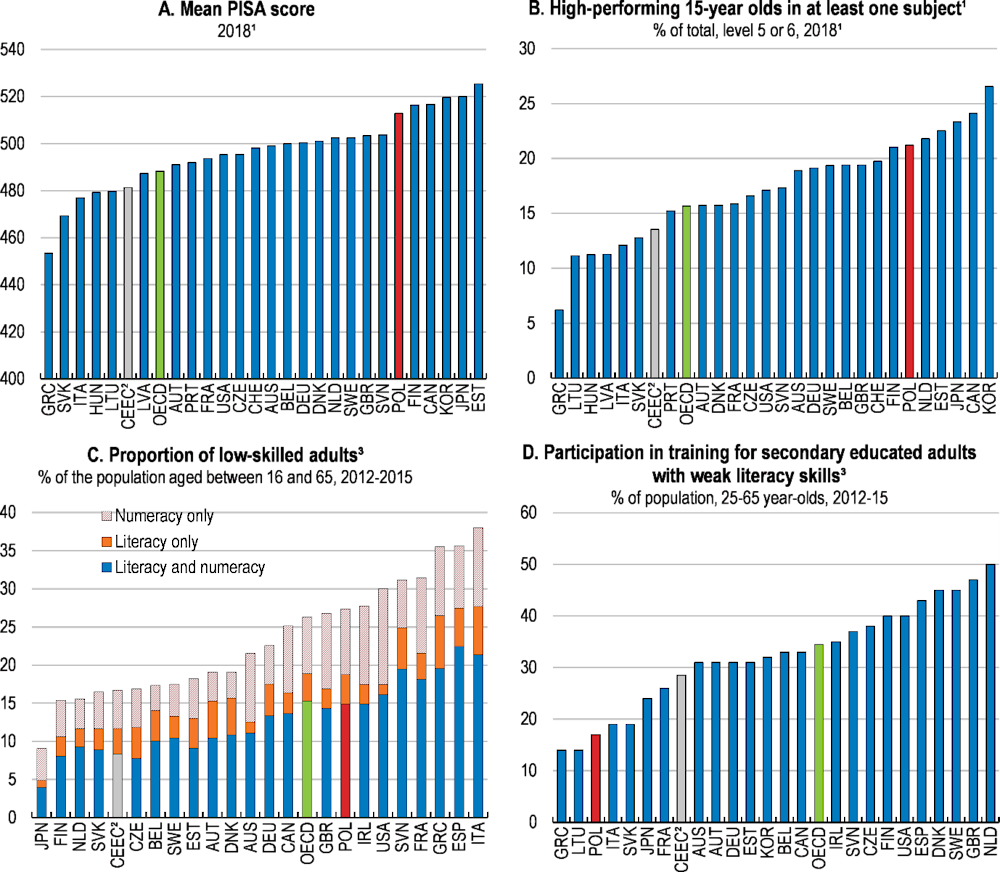

The Polish economy is shifting towards higher-skilled employment. Since transitioning from central planning, the service sector has expanded and manufacturing has become tightly integrated into global value chains, changing more and more the skill set that is needed in the labour market. The changing structure of the economy, as well as the increase in computerisation and automation, led to higher productivity. However, at the same time, the changing job profiles means that non-cognitive routine jobs are progressively disappearing. Employment is shifting from low- and medium-skilled jobs towards high-skilled jobs (Figure 1.25, Panel A). The growing demand for skilled workers is projected to continue (Cedefop, 2018) and providing workers with the right skills to adapt to a changing environment will sustain productivity growth (Panel B). Preparing the labour market for technological change is high on the political agenda and the government is preparing its skill strategy with the support of the OECD (2019d).

Enhancing labour market inclusiveness

Strengthening skills and their efficient use

Enhanced education and training will be essential to support the recovery and return to previous growth levels. Up-skilling and re-skilling will be crucial as the economic activity resumes. The number of jobseekers is expected to be higher than before and there may be permanent shifts in the demand for labour across sectors (OECD, 2020a). Training would help to swiftly reallocate displaced workers. Lifting up the skills of workers would also enable local firms to benefit from knowledge diffusion and technological adaptation to move production towards higher-value activities (OECD, 2017). In particular, the wider use of learning models at work could have a sizable effect on Poland’s GDP (Box 1.3).

Figure 1.25. Upskilling and automation are challenging issues

1. High-skill occupations are managers, professionals and technicians (ISCO88 codes: 1, 2 and 3). Middle skill occupations are clerks, machine operatives and crafts (codes: 4, 7 and 8). Low-skill occupations are sales and service occupations and elementary occupations (codes: 5 and 9). The time period covered is 2006-16, except for: Korea (2006 14); Australia (2006-15); Greece, Portugal and Latvia (2007-16); Italy (2007-15), Switzerland (2008-15); Canada, Ireland, and Luxembourg (2006-15).

2. CEEC is the average of Hungary and the Czech and Slovak Republics in Panel A, and of the Czech and Slovak Republics in Panel B.