Srdan Tatomir

OECD

OECD Economic Surveys: Poland 2023

2. Digitalising the Polish Economy

Abstract

Increasing digitalisation can further boost Poland’s productivity but successful digitalisation requires governments to take a comprehensive policy approach. Adoption of digital technologies is relatively low among firms, particularly SMEs. Expanded consultancy and technical support would help, as would accelerating the deployment of 5G networks. Although ICT innovation has been growing, it is relatively low and should be supported further. Skills are essential to ensuring an inclusive digital transition. Digital skills are particularly low among older adults. There are shortages of ICT specialists. Managerial skills, key to implementing digitalisation in firms, could also be higher. Skills gaps should be addressed by encouraging more students, especially women, to study ICT. Schools need to be better equipped with technology and links between education institutions and industry should be stronger. Effective implementation of the new migration programmes could raise the supply of ICT specialists. Moreover, there is a need to expand training and to make further education more practical and flexible to encourage lifelong learning. The government has been rapidly digitalising, which can facilitate the digital transition in the wider economy. It should continue to do so, and to enhance cybersecurity.

Introduction

Digital technologies have the potential to improve productivity, leading to higher wages and living standards, better public services, and greater well-being (OECD, 2019d; Gal et al., 2019). Successful digitalisation requires a comprehensive approach across a range of structural policy areas because many factors are complementary to each other. A widespread and fast communications infrastructure underpins digitalisation, while advanced managerial and worker skills are essential to the successful adoption of digital technology. A supportive regulatory environment can incentivise digitalisation by increasing returns to investment in technologies and skills. Innovation and e-government can further support and facilitate this process.

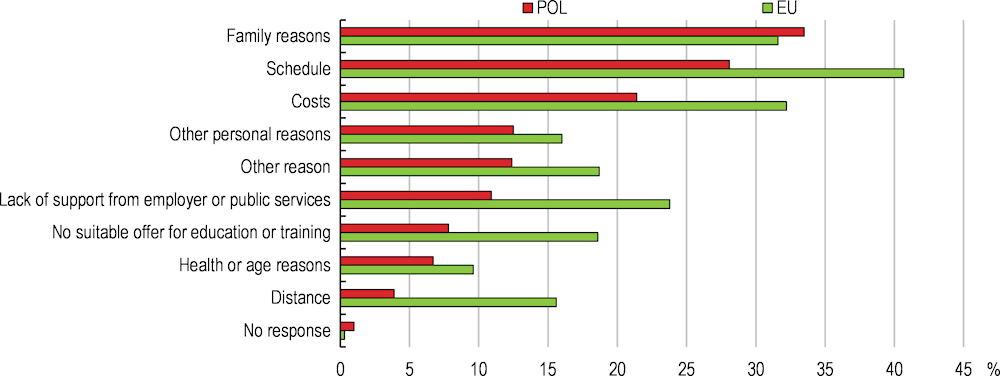

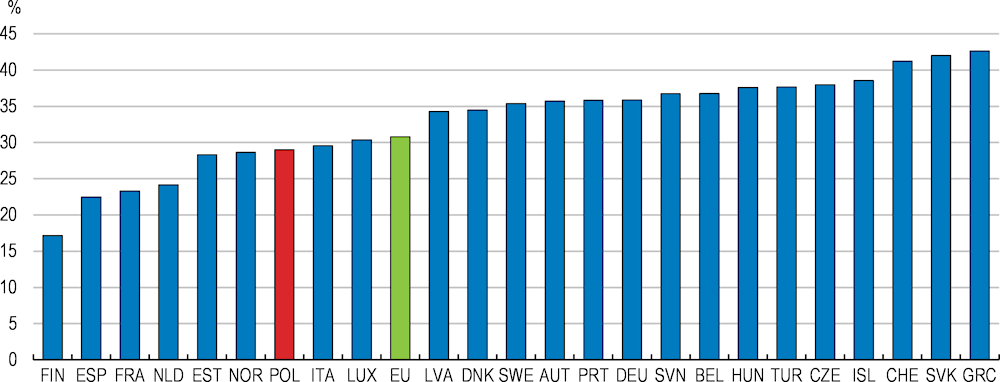

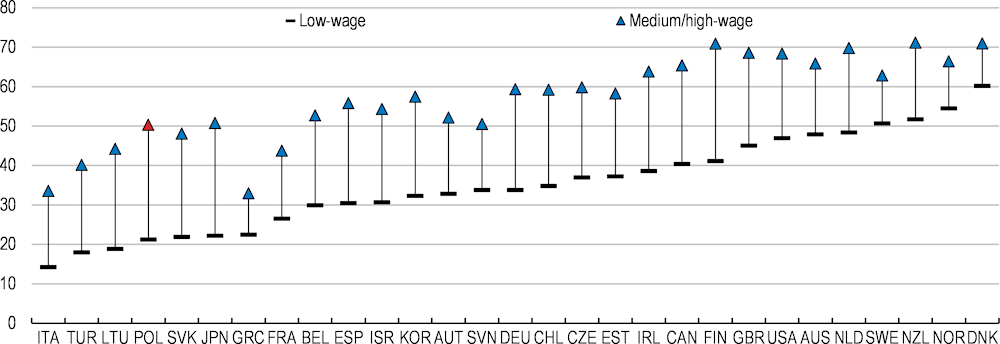

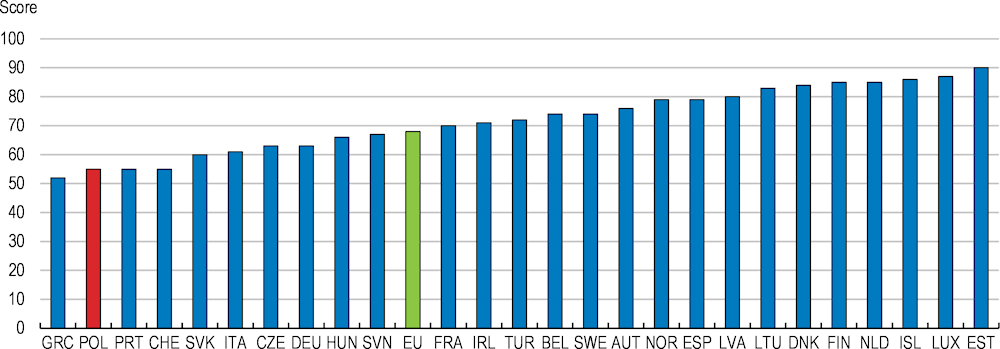

Despite significant progress in recent years, Poland is less digitalised than other peer countries. Based on a composite measure of digital skills, digital technology adoption, communication networks, and digital government, Poland ranked 24th out of 27 EU countries in 2022, although it has been catching up over the past five years (Figure 2.1). Digital skills are below average and the level of firms’ integration of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) is behind most advanced economies. Overall, digital innovation is low, but the number of new firms has been growing and finance for digital investment has steadily become more available. Digitalisation within government has improved, but has not yet caught up with OECD best performers and remains below average. Thus, there is substantial scope to further digitalise the economy and increase productivity.

Figure 2.1. Poland is less digitalised than the EU average

Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI), 2022

Note: the DESI is an equally weighted index of four dimensions: human capital (internet user skills and advanced digital skills and development), connectivity (fixed broadband take-up and coverage, mobile broadband, and broadband prices), integration of digital technology (ICT adoption among firms and e-Commerce) and digital public services (development of e-Government services).

Source: European Commission DESI 2022.

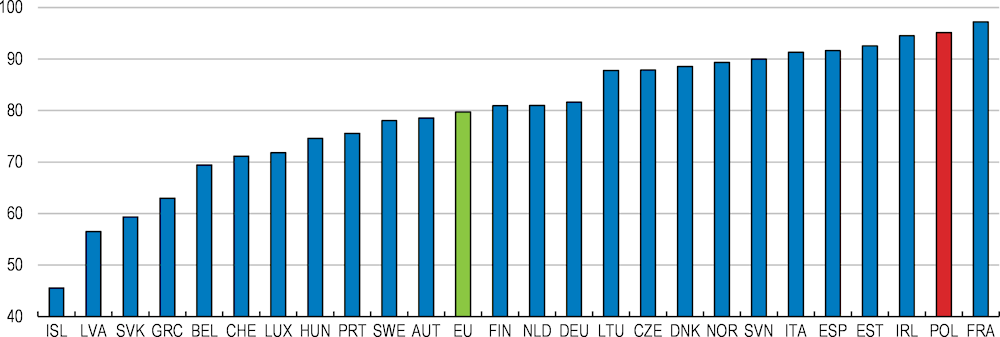

A range of policies can boost digitalisation and increase productivity. For Poland, upgrading managerial and technical (digital) skills could provide a significant boost to productivity. Investing in ICT adoption in firms, notably through higher use of high-speed broadband, would also help. Other factors could further contribute, such as lowering regulatory barriers and increasing competition and providing easier access to finance. Higher use of digital government services is likely to facilitate digitalisation. Estimates based on Sorbe et al. (2019) suggest that closing a quarter of the gap with the best performing countries in these policy areas could increase Poland’s productivity levels by up to 9% after three years (Figure 2.2). Policies specifically boosting digitalisation could raise the long-run level of GDP by around 6%. Complementarities between different factors could increase productivity further.

The digitalisation of the Polish economy should be driven by the private sector, but public policies can support and facilitate the digital transformation. The positive returns to digital investment should provide strong market incentives to firms and workers to digitalise, but it is not always easy in practice for firms to reap the benefits. The government can support this process by providing a regulatory framework that enables investment in communications infrastructure and digital technologies. It can facilitate ICT adoption by boosting the development of general digital and management skills. It can provide basic research and development as well as finance to support innovation. Finally, digitalisation in the private sector can be facilitated by digitalising the public sector.

Figure 2.2. A range of policies can boost digitalisation and increase productivity

Effect of improving digital adoption on firm productivity by closing a quarter of the gap with best performing countries

Notes: Estimated effect on multi-factor productivity (MFP) of the average firm from closing one-fourth of the gap to best-performing countries across a range of policy and structural factors (see Box 1 in Sorbe et al., 2019). “Reducing regulatory barriers to competition and reallocation” includes lowering administrative barriers to start-ups, relaxing labour protection on regular contracts and enhancing insolvency regimes. “Easier financing for young innovative firms” covers the development of venture capital markets and the generosity of R&D tax subsidies. “Upgrading skills” covers participation in training, quality of management schools and adoption of High Performance Work Practices. The effect of “Higher use of high-speed broadband” on productivity combines the direct and indirect effects presented in Figure 6 in Sorbe et al. (2019). High-speed broadband refers to broadband connections with least 30 Mbit/sec data transfer speed. “Reducing barriers to digital trade” includes lowering barriers to cross-border data flows and online sales and enhancing regulatory regimes for data privacy and security.

Source: Sorbe et al. (2019), "Digital dividend: policies to harness the productivity potential of digital technologies", OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 26.

Notwithstanding the substantial benefits it can bring, digitalisation can entail significant disruptions and costs. Technical changes within firms are likely to favour highly skilled workers whose skills can be complementary in implementing and working with digital technologies (OECD, 2019d). Less skilled workers, particularly those who do routine manual tasks that can easily be automated, are likely to be negatively affected by new technologies such as automation. This can lead to lower wages for less skilled workers and fewer jobs. Consequently, in the absence of policy intervention, income inequality and unemployment could rise, at least in the short term (OECD, 2019d). Regional inequalities could increase as digital activities may concentrate in some regions, although digital technologies can also help people work remotely. The digitalisation of firms and markets can increase competition within countries and between countries for firms and workers. However, the best firms are likely to thrive, while less competitive firms might lag far behind, and competition issues can arise in winner-takes-all markets (OECD, 2019d). To address the impact on workers, flexible learning systems are needed that upgrade and develop digital skills in order to minimise the effects on employment and wages. To ensure vibrant markets, this involves supporting innovation within new and existing firms to boost competitiveness, while ensuring enough flexibility for an efficient allocation of capital and labour resources.

This chapter looks at key digitalisation challenges and associated policies in Poland. It develops policy recommendations to leverage the productive potential of digital technologies and promote a sustainable and inclusive digital society. First, it discusses ICT adoption in firms, innovation and finance while also emphasising the role of infrastructure and the regulatory framework. Second, it covers digital skills and the role of education, both formal and adult learning, in the digital transition. Finally, it describes the importance of digital government in facilitating digitalisation. The chapter draws on the OECD’s Going Digital Policy framework (OECD, 2019d) and previous OECD work on productivity (Gal et al., 2019; Sorbe et al., 2019; Andrews et al., 2018), the OECD Skills Outlook (OECD, 2019c; 2021d) and the OECD Skills Strategy for Poland (OECD, 2019a).

Supporting the adoption of digital technologies in firms

Firms increasingly need to adopt new digital technologies

Aggregate GDP growth in the past was mostly driven by capital accumulation but the capital-driven growth model may be reaching its limits (World Bank, 2021). Given diminishing returns to capital and a decreasing labour force due to an ageing population, productivity growth will be increasingly important in driving long-term growth.

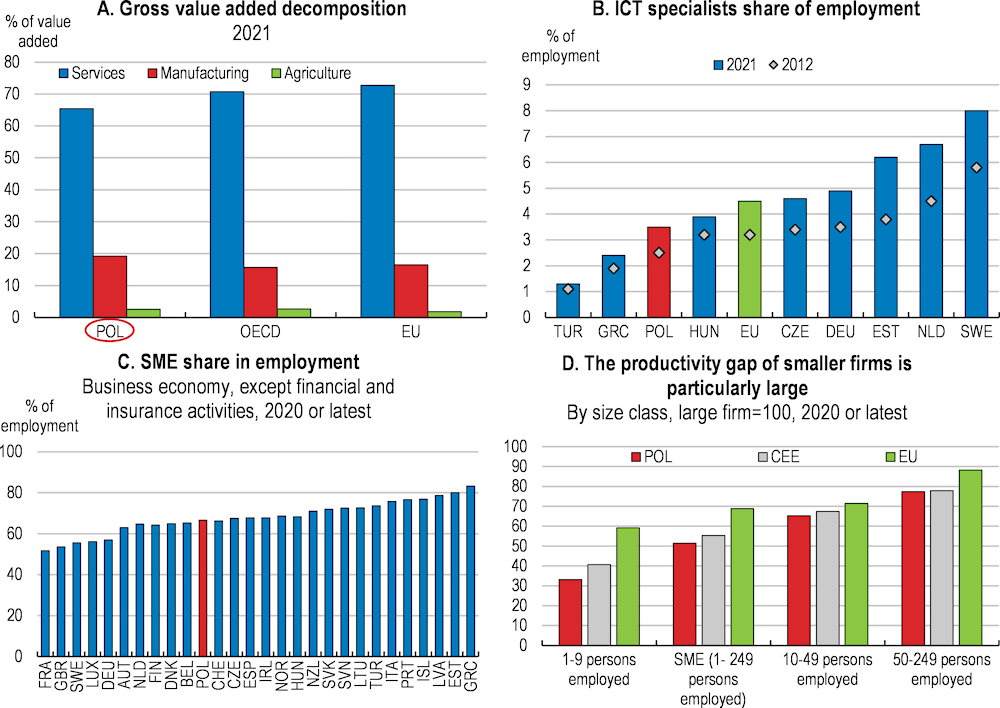

Around two thirds of the Polish economy is based on services while manufacturing accounts for almost a fifth of economic activity (Figure 2.3, Panel A). Most of the manufacturing total factor productivity (TFP) growth in 2009-19 was due to productivity improvements within firms. In services, TFP growth was due to a combination of individual firms becoming more productive, more productive firms entering the market and less productive firms exiting and, to a lesser extent, more productive firms gaining market share (World Bank, 2022). This suggests that policies that boost productivity within firms are the most relevant but ensuring good conditions for new firms and competitive markets is important as well.

Digitalisation has become increasingly important in the economy and for Polish firms. The ICT industry accounts for 3.5% of total employment, below the EU average, but this has been growing (Panel B). Digitally intensive sectors of the economy accounted for half of all jobs and 60% of GDP growth in 2018 (OECD, 2023). Trade has boosted technological adoption. Foreign-owned firms, important drivers of Polish exports in industries such as automotive, transport equipment but also computer programming services and pharmaceuticals, tend to be large and more technologically advanced (World Bank, 2022; OECD, 2020b). Domestic small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) act as suppliers to foreign affiliates and, as a result, they tend to be more digitally developed (Cadestin et al., 2019). Polish SMEs could benefit from more digitalisation. They account for two thirds of all employment (Panel C) and half of all output. However, they are less productive than in neighbouring European countries and than the OECD average. This is mostly because Poland has a higher share of micro firms, those that hire 9 employees or less (OECD, 2020b).

Figure 2.3. Digitalisation could boost productivity especially in SMEs

Note: CEE is the average of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovak Republic.

Source: OECD National Accounts at a Glance; Eurostat (isoc_sks_itspt); and OECD SDBS Structural Business Statistics.

The diffusion of new technologies depends on both firms’ capabilities and incentives. Organisational capital such as management skills is key to recognising the benefit of new technologies and implementing them in firms. Management quality in Poland is average and it is lower in domestic firms than in foreign-owned firms (see Section Supporting the adoption of digital technologies in firms). Available and effectively employed digitally skilled workers are necessary to operate new technologies successfully (Andrews et al., 2018). Digital skills among older adults still lag well behind other countries and could improve (see Section Supporting the adoption of digital technologies in firms). But dynamic labour and product markets also matter. Greater competition incentivises firms to invest more, subject to good communications infrastructure and freely available capital to finance new ICT investment. Poland could further liberalise some professions (see Section Regulatory barriers to competition can be lowered further). Its communications infrastructure is well developed although it could upgrade to 5G to prepare for the adoption of the latest digital technologies. Direct participation in international trade or integration in global supply chains can lead to higher digital technology adoption.

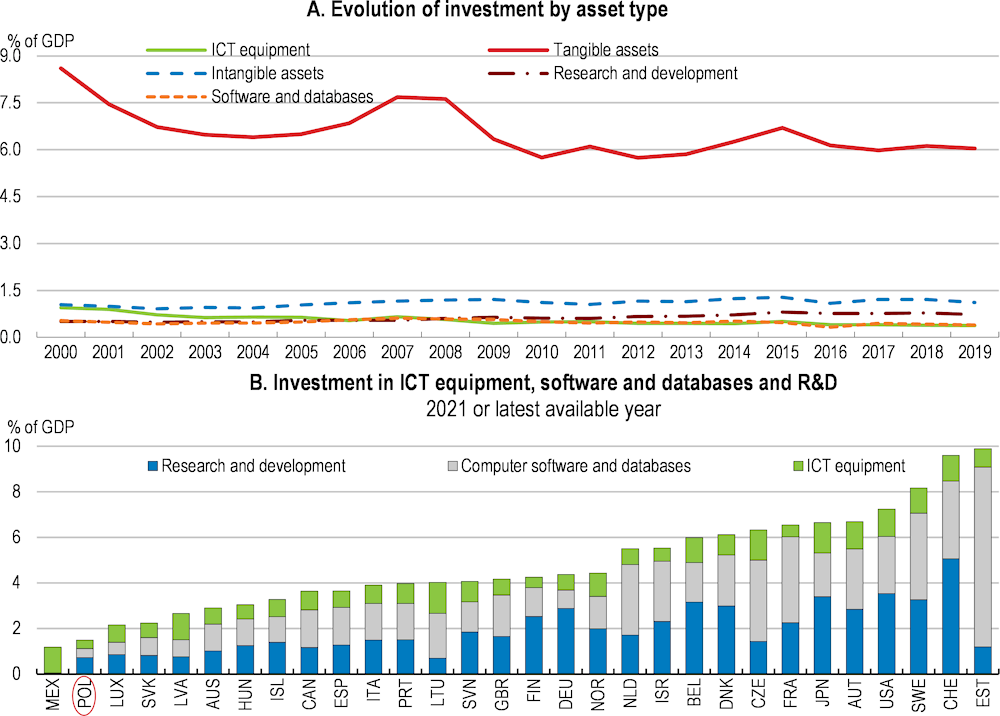

Figure 2.4. Intangible investment and ICT investment are relatively low

Note: Investment is based on gross fixed capital formation.

Source OECD National Accounts Statistics.

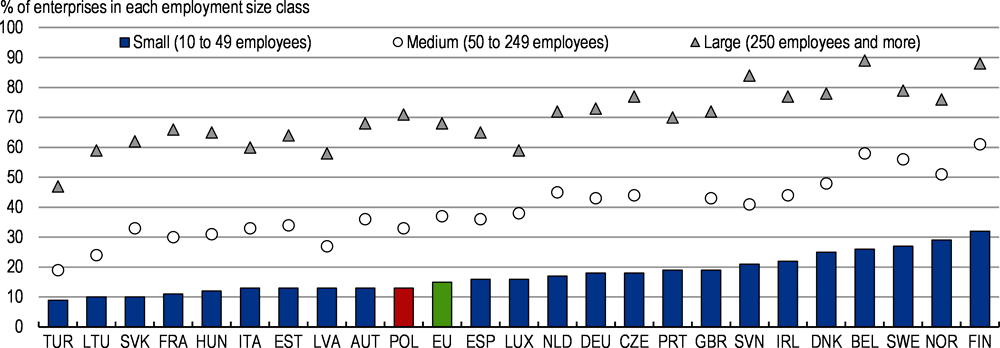

ICT intensity and adoption is relatively low in Poland, although it is increasing. Total investment in ICT is well below the OECD average (Figure 2.4). Almost all Polish businesses have a broadband connection and the speeds of those connections have improved over time. Around 70% of those businesses have a website and half of their employees have used a computer with internet access. However, only a minority of firms buy and sell online and work with e-invoices. Digital adoption for Polish SMEs appears to be lower than the EU average. Micro enterprises tend to be the least digitally advanced as their skills largely depend on the digital skills of the owner (Lewiatan, 2016). Many smaller Polish firms are online, use computers and operate websites, but they are much less likely to employ advanced technologies or hire dedicated ICT staff than larger firms. Online platforms can help firms find customers in a variety of sectors such as personal transport, accommodation, food services, retail trade, finance, entertainment, and personal services. They can help SMEs export by reducing the sizable entry costs of exporting related to finding foreign buyers and establishing distribution channels (Melitz, 2003). OECD evidence suggests that a strong platform presence can boost productivity, especially in service sectors and for small and medium enterprises (Pisu and von Rüden, 2021; Bailin Rivares et al., 2019).

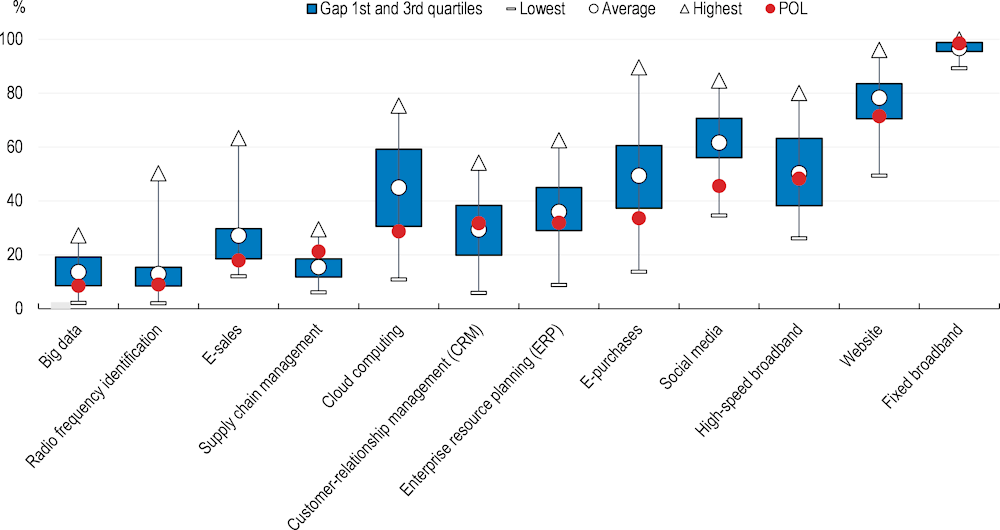

Adoption of more advanced digital technologies is slightly below the OECD average. Around 30% of firms use Enterprise Resource Planning software, Customer Relations Planning software and cloud computing. The use of big data and artificial intelligence is also somewhat below most other OECD countries (Figure 2.5). Most of the variation in technology adoption occurs within rather than between firms. Most firms tend to use a combination of technologies for different business functions but to varying degrees of intensity (World Bank, 2022). This suggests that digital technology gaps are specific to each firm rather than common within sectors or across the economy.

The level of digitalisation varies by sector. Retail trade, media and professional and business services are some of the most digitally advanced sectors while transportation exhibits lower levels of ICT adoption (CASE, 2020). Even within sectors there can be significant variation. For example, within manufacturing more advanced sub-sectors have digitalised to levels similar to Western European countries while manufacturers of basic goods are much less digitalised and instead prefer to rely on lower cost labour. The appropriate digital technology might also vary by sector. E-commerce may be relevant for firms selling directly to many consumers. For some manufacturing companies, focusing on a small set of customers and selling larger volumes, robotisation and specialised production technology might be more appropriate (CASE, 2020).

Figure 2.5. Digital technology adoption is relatively low in Poland

Diffusion of selected ICT tools and activities in enterprises, 2021 or latest

Note: ERP systems are software-based tools that can integrate the management of internal and external information flows, from material and human resources to finance, accounting, and customer relations. Here, only sharing of information within the firm is considered. Cloud computing refers to ICT services used over the Internet as a set of computing resources to access software, computing power, storage capacity and so on. Supply chain management refers to the use of automated data exchange applications. Big data analysis refers to the use of techniques, technologies, and software tools for analysing big data. This, in turn, relates to the huge amount of data generated from activities that are carried out electronically and from machine-to-machine communications. Social media refer to applications based on Internet technology or communication platforms for connecting, creating, and exchanging content online with customers, suppliers, or partners, or within the enterprise. Radio frequency identification (RFID) is a technology that enables contactless transmission of information via radio waves.

Source: OECD ICT Access and Usage by Businesses Database, http://oe.cd/bus.

The level of robotisation tends to be relatively low. Within the European Union, Poland had 42 robots per 10,000 industry workers, lower than the level of around 130 robots in Czech Republic and Slovakia and below the best performers such as Sweden with 262 robots per 10,000 industry workers (Leśniewicz and Święcicki, 2021). While industrial composition and lower relative wages can partly explain the lower density of robotisation, there is scope for a higher adoption of industrial robots in production.

The use of teleworking has accelerated with the pandemic. This can partly boost productivity as it allows for more efficient and intensive work, although teleworking can have drawbacks as well (Criscuolo et al., 2021). In 2019, around 4.6% of employed people aged 15-64 in Poland reported usually working from home, but this rose to around 8.9% in 2020 (Eurostat, 2022a). Teleworking increased strongly in ICT and knowledge-intensive sectors, but the overall rise was smaller than in most European countries as these sectors account for a comparatively smaller share of total employment (Milasi, Gonzalez-Vazquez and Fernandez-Macias, 2021). Teleworking is likely to persist as the share of advertised vacancies including teleworking has remained higher even as pandemic restrictions have eased (Adrjan et al., 2021). Three quarters of workers who had worked remotely would like to combine remote work with office work (Radziukiewicz, 2021). Teleworking should be encouraged where feasible as it can catalyse digitalisation within firms, particularly SMEs, and it can also widen the pool of workers available to firms, potentially easing local skill shortages.

There are multiple drivers of comparatively lower ICT adoption in Poland. One of the key reasons is firms overestimating their own technological sophistication. According to the Technology Adoption Survey, most Polish firms think they are more advanced than their competitors and the difference between perceptions and actual levels of technological adoption is most pronounced for the least technologically advanced firms (World Bank, 2022). Polish firms tend to overestimate the costs of new technologies and to undervalue the benefits. This is consistent with other studies which suggest that many firms perceive no need for ICT investment. When they do invest in ICT, the main obstacles include insufficient funds and a lack of time (Orłowska and Żołądkiewicz, 2018; Lewandowski and Tomczak, 2017). A study focused on the manufacturing sector suggests insufficient capital expenditure, weak administrative capacity and a lack of skills as driving lower adoption of more advanced technologies. For some firms a perceived lack of government support is also an obstacle (Jankowska et al., 2022).

The government has mostly focused on demand-side policies and introduced various programmes to support digitalisation. In 2019, the “Future Industry Platform” foundation was set up by the Ministry of Economic Development and Technology (MRiT). It is run with the goal of accelerating the digital transformation of industry through promotion of and technical support for new technology adoption. Five digital innovation hubs have been set up to support firms under a pilot programme in 2019-21 in Gdańsk, Kraków, Poznań, Warsaw and Wrocław and some will continue as European digital innovation hubs in 2023. In 2022, the authorities introduced tax relief allowing firms to additionally deduct up to 50% of their robotisation costs. Currently, the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development (PARP) is running several pilot programmes to support digitalisation. One of them offers grants up to EUR 180,000 to help SMEs in the furniture industry to invest in robots. PARP also runs programmes such as “Vouchers for digitalisation”, covering 700 firms, and “Digital Manager”, covering around 850 firms, that provide financial support, training and advisory support to companies investing in digital technology.

To facilitate digital investment in firms further, the authorities should consider expanding targeted technical and advisory support. While many ICT investments can be profitable, SMEs often lack the knowledge and skills to choose the appropriate ICT tools, which results in low demand for ICT investment (World Bank, 2022). There is a need for proactive consultancy and advisory services to stimulate demand. Unfortunately, only a few consultancies focus on smaller firms and, to the extent these exist, SMEs might be financially unable to finance such services. In the manufacturing sector, the Future Industry Platform programme tries to raise awareness by promoting Industry 4.0 technologies, while also offering advisory and technical support for implementing new technology. PARP is another agency that offers advice and support to both new and existing firms, and its programmes often support product or process innovation. One option would be for agencies such as PARP, to expand and broaden stand-alone consulting services to advise SMEs on how to digitalise and provide financial and technical support to those firms that invest in ICT. Another complementary option could be for the Future Industry Platform to widen its reach across sectors and promoted technologies. Given the heterogeneity across and within sectors, such support should be tailored and customised to firms’ specific circumstances. In this respect, widespread use of assessments that determine firms’ ICT needs would be useful. Box 2.1 sets outs different approaches OECD countries have taken to help SMEs digitalise.

Box 2.1. OECD countries use a wide range of policies to help SMEs digitalise

OECD countries offer a wide range of policies to help SMEs digitalise, ranging from grants that subsidise investments in digital technologies to training to help firms implement investments at their own cost.

Australia’s Small Business Digital Champions project supports 100 small businesses. The project has a total budget of AUD 8.9 million and provides up to AUD 18 500 in assistance, with additional support from partner firms. Of these small businesses, 15 were chosen as Digital Champions and received mentoring from high-profile business people to guide them through the digital transformation. This process is then documented and showcased online. The programme is complemented by the “Digital Solutions” programme of the Small Business Advisory Service. SMEs pay a (subsidised) fee for advice on implementing digital technologies, such as websites, e-commerce, social media, and small business software. The programme also offers advice on online security and data privacy.

In Denmark, the Danish Business Authority distributes grants (valued at approximately EUR 1300) to 2000 SMEs under the SMV:Digital programme. The grants are used for private consultancy to help the SMEs identify digital opportunities with a special focus on e-commerce, prepare business cases for digital transformation and implement digital solutions.

Portugal also has a grant scheme to assist SMEs with the use of digital technologies in fields such as e-commerce, online marketing, website development and big data. The grant covers 75% of eligible expenses up to EUR 7 500 for projects that take up to one year to implement.

Austria helps SMEs digitalise through the KMU Digital programme. The programme includes: 1) an online tool to allow firms to assess their level of digital maturity; 2) an individual consultation to examine what can be improved and how; 3) a consultation focused on the specific needs of the firm (in areas such as e-commerce, IT security, data protection and digitalisation of internal processes); and 4) digital skills training courses for entrepreneurs and employees.

Chile’s innovation agency recently launched the Digitalise Your SME (“Digitaliza tu Pyme”) programme to provide e-commerce courses (78 hours of classroom experience), in which small business owners can learn about digital marketing, the use of social networks and electronic commerce. By the end of the programme, participants should understand processes associated with e-commerce such as the use of online platforms.

Source: OECD, Digital Economy Policy Platform (DEPP), edition 12/12/2021, https://depp.oecd.org/

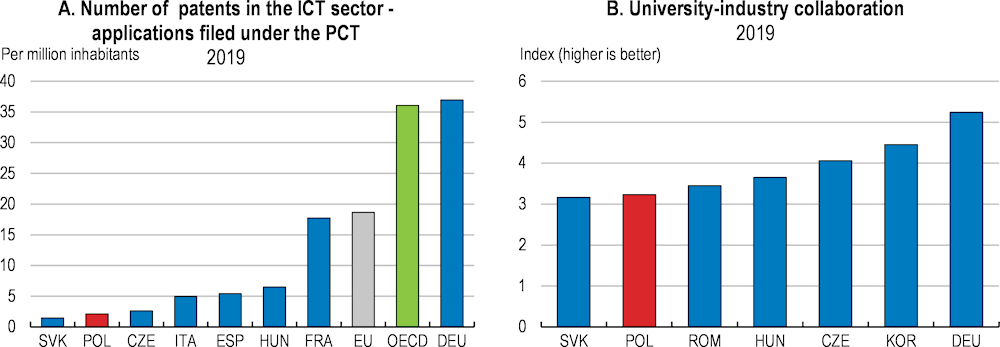

Innovation is essential for a digitalised economy

Poland should boost its ICT innovation capabilities. Although R&D investment has increased steadily since 2015 and has been catching up to neighbouring European countries, it was around 1.4% of GDP in 2020, which remains lower than in the Czech Republic and well below the OECD average (OECD, 2022d). R&D by ICT firms is also relatively low. Poland’s innovation system’s performance is the fourth lowest in the EU, similar to Slovakia’s performance but below the Czech Republic and Estonia (EC, 2022d). While computer science research is relatively prominent, it is less successful in terms of practical innovation. The rate of high-tech patents is similar to other Central and Eastern European countries, but significantly below the EU average (Figure 2.6 – Panel A). ICT patents make up around 10% of overall patents, far below the EU and OECD averages. Collaboration between universities and industry is on par with other countries in the region although a little below the Czech Republic and significantly below top performing countries like South Korea and Germany (Figure 2.6 – Panel B).

Figure 2.6. ICT innovation is low and could be better linked to industry

Note: Panel A - PCT is the Patent Cooperation Treaty. It refers to so-called priority dates, corresponding to first filling worldwide.

Source: OECD MSTI database; World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Index.

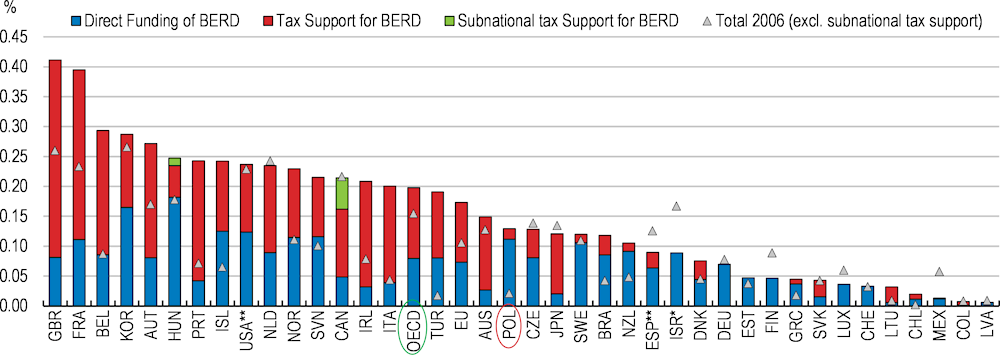

Successive reforms by the authorities have removed barriers and markedly increased incentives for R&D investment since 2016 when an enhanced, volume-based R&D tax allowance was introduced (OECD, 2021d). In 2022, a tax package called “Polish Deal”, including a broad range of tax incentives to boost innovation and attract foreign investment, came into effect. More specifically, there are incentives for organisations conducting R&D that lower the cost of collaboration between firms and research institutions, incentives for investing in automation and robotisation, enhancing/developing new products and patents, and expanding businesses. For example, the new law entitles firms to deduct 200% of employees’ costs in R&D from their tax base, up from 100% (EY, 2021). This should boost innovation, but the impact will need to be evaluated over time. The EU Smart Growth programme has helped fund innovation in Poland but the government could also consider boosting direct funding for R&D, focusing the additional funds specifically on ICT (Figure 2.7). In addition, Poland’s “State purchasing policy 2022-25” aims to allocate 20% to innovative solutions (EC, 2022a).

Improving national research capacity and strengthening links between research and the private sector will help drive innovation including in ICT. Poland used to account for only 0.4% of global research and 64% of active researchers have only published with a domestic affiliation (Kamalski and Plume, 2013). In 2022, 10 Polish universities ranked in the Shanghai Top 500, up from two in 2016. However, Poland should continue to improve its academic research output through internationalisation because this tends to be positively correlated with higher scientific quality. It is important to enhance the internationalisation of existing staff further, continue to expand faculty and student exchanges, and bring top foreign academics and researchers to Poland to pursue cross-border collaborative research (EC, 2017). Furthermore, Poland should incentivise universities and research institutes to pursue more collaboration with industry when undertaking R&D and strengthen the role of technology transfer and commercialisation efforts (EC, 2017). Tax relief for cooperation between entrepreneurs and research institutions has been introduced and this should help.

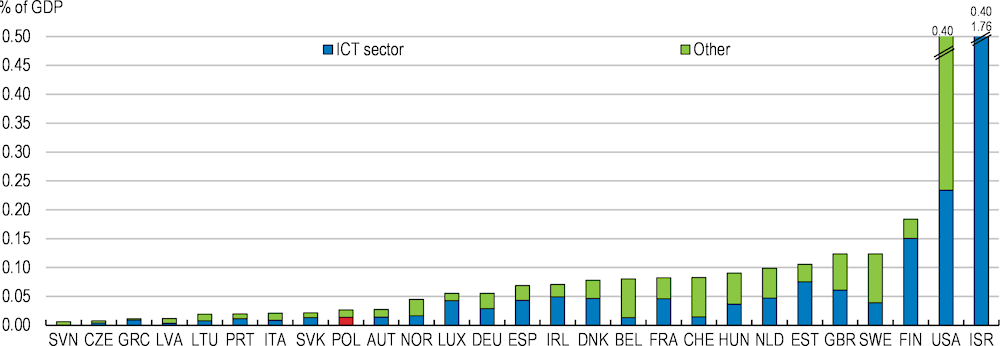

Figure 2.7. Government support for R&D has been below the OECD average

Direct government funding and government tax support for business R&D, 2019

* Data on tax support not available, ** Data on subnational tax support not available.

Source: OECD R&D Tax Incentives Database, http://oe.cd/rdtax, April 2022.

Financing digital investment

Expanding access to finance for new and innovative firms is important for digital innovation, both in the digital sectors and more widely. The system supporting start-ups has been rapidly developing recently. Poland has a higher share of ICT start-ups than the OECD average. Venture capital (VC) funding was relatively low in 2020 (Figure 2.8). However, it has been growing fast and expanded from PLN 2.2bn in 2020 to PLN 3.7bn in 2021, partly supported by the EU-funded “Start in Poland” programme. In 2021, there were 113 active VC funds and a third of the transactions by value came from public-private funds, focusing mostly on smaller transactions (PFR, 2021). Within the Polish Development Fund (PFR), PFR Ventures helps support start-ups through investment across a range of venture capital and private equity funds. Earlier stages of start-up development have been supported by a government agency, PARP, through incubation and accelerator programmes across the country. However, as the system has been maturing it will be important to make finance available for new companies at later stages. In this respect, PFR Ventures should continue its financial support of the Polish start-ups and expand into later stage financing up until the new firms’ initial public offerings.

Figure 2.8. Venture capital in the ICT sector could be boosted further

Venture capital investment breakdown, 2021 or latest available

One constraint facing small and young digital firms is access to bank funding. Intangible assets, such as intellectual property (IP) and software are not easily used as a collateral to access debt finance because they often do not have a market value, are not easily separable from the firm and often cannot be transferred without a loss. In order to support the digital take-up and ease credit for SMEs, several OECD countries have established new programmes to support IP-backed loan and IP valuations (Box 2.2). The government could consider creating a collateral registry to improve SME access to loans (OECD, 2021g). Estimating the creditworthiness of small firms is particularly difficult and costly, and the related uncertainty drives up interest rates and tightens lending conditions.

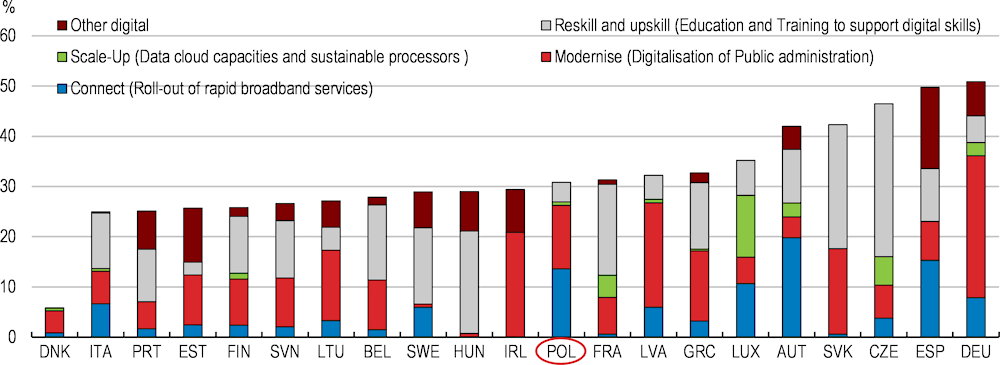

To complement private sector finance, Poland is also using public funds. In particular, it plans to rely on substantial financial support from EU funds to finance digitalisation. At least a third of its national Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), EUR 11.1bn or 1.9% of 2021 GDP, will go to digital projects (Figure 2.9). The funds will be allocated across a range of projects that aim to improve digital administration and e-services, encompassing infrastructure, public sector worker skills, administrative process efficiency and analytical capacity for decision-making. However, the plan focuses mostly on digital connectivity and the public sector and not enough on supporting digitalisation in the private sector. In addition, RRP funds have been delayed and there is significant uncertainty around their disbursement.

Figure 2.9. Around a third of national Recovery and Resilience Plan spending is for digital projects

Overall resource allocation in national recovery and resilience plans, % of total RRF grants and loans

Box 2.2. Intellectual property (IP)-backed loans and IP valuation schemes for SMEs across the OECD

Several OECD countries have implemented programmes supporting intangible-intensive SMEs to get access to bank loans. Selected examples include:

The French public investment bank Bpifrance provides uncollateralised loans and bank loan guarantees to SMEs to support their digitalisation. Support is available for investment in intangibles, including intellectual property and software.

The Bavaria Digital (Germany) initiative provides digital SMEs with loans on favourable terms for a total amount of up to EUR 1 million. In order to reach more SMEs, the application process was streamlined to reduce the administrative burden and part of the application cost is covered by a grant from the State of Bavaria.

The Japan Patent Office and the country’s Financial Service Agency assess the value of intellectual property of SMEs. They finance and conduct IP evaluation reports of SMEs, which inform the lending decisions of banks.

The Korean Development Bank’s Techno Banking initiative provides loans to SMEs for purchasing, commercialising, and collateralising intellectual property. The Bank also established a collection fund for distressed intellectual property for the disposal of intangible assets. In addition, the public Korea Credit Guarantee Fund provides credit guarantee schemes, some of them supporting intangibles as collateral. As in Japan, the Korean Intellectual Property Office estimates the value of SMEs’ IP to facilitate loans by the Korea Development Bank and the Korea Credit Guarantee Fund.

Source: OECD (2019), Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2019: An OECD Scoreboard.

Speeding up and upgrading the communications infrastructure

Reliable connectivity is essential for the digital transformation. The COVID-19 pandemic fueled demand for broadband communication services. Some operators have experienced as much as a 60% Internet traffic growth compared to before the crisis. Gigabit networks and 5G are likely to become the underlying connectivity behind the Internet of Things and artificial intelligence and for connected devices in critical contexts, including in health, energy or in transport sectors (OECD, 2020a). This underscores the need for ultra-reliable, low-latency networks (OECD, 2018). In the future, communication networks will also need to become more flexible and, in this sense, 5G may allow the same network to cater to objects with diverse quality features (OECD, 2019f).

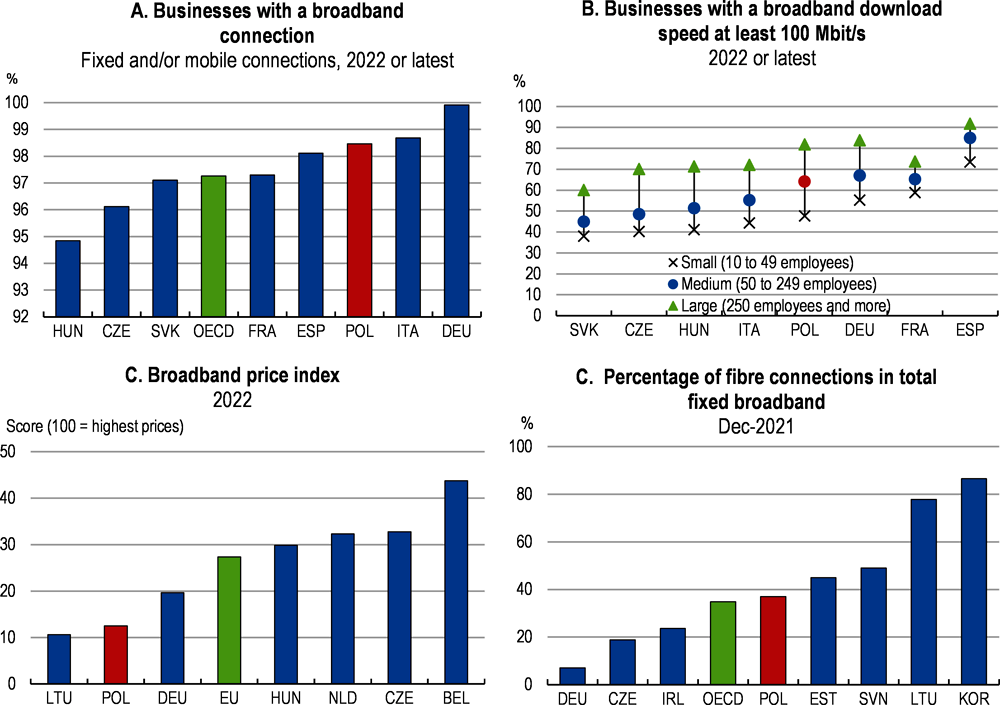

Overall, the communications infrastructure in Poland is relatively good. The share of households and businesses with access to the internet has increased in 2021 and the rural-urban divide is small. Access to higher internet speeds has risen, but could improve further. Fixed broadband speeds and latencies are higher than the OECD average while mobile broadband speeds are below average. Prices for fixed and mobile broadband are among the lowest in the EU. However, internet usage is not as intense as in other countries. Broadband penetration as measured in terms of subscriptions is below the OECD average and the share of firms with fast broadband could be higher (Figure 2.10).

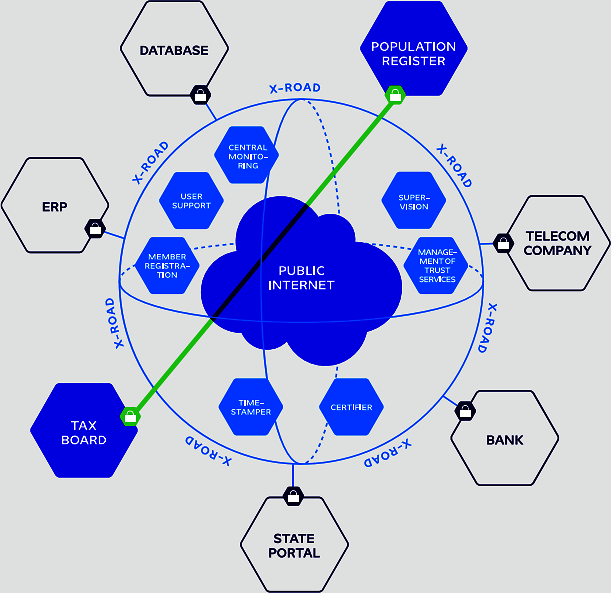

Work is ongoing to improve the infrastructure further. The authorities plan to draw on the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) to finance their future connectivity ambitions. The government estimates that both the RRF and the 2021-2027 ERDF will contribute around EUR 2 billion to the broadband inclusion of at least 1.5 million households in areas with no internet infrastructure, increasing the share of households with access to the internet to over 80% and boosting participation in the digital economy. The main goal of the Polish Digital Transformation Strategy for 2025 outlined in the National Broadband plan is to ensure universal internet access with downstream connection speed of at least 100 Mbps with the option to upgrade to gigabit speeds, providing at least 1Gbps for educational establishments, transport hubs and data-intensive companies, and 5G connectivity on all major communication routes and in major urban centres (EC, 2022b).

Deployment of 5G is planned for 2023. Some operators have rolled out 5G using existing infrastructure and without a dedicated 5G spectrum. This has resulted in some of the lowest 5G speeds in Central and Eastern Europe. In May 2020, the Polish government cancelled the auction of the 3.6 GHz band due to security concerns about adequate cybersecurity levels for the new network. The authorities decided to revise the legislation on the national cybersecurity system to address emerging new threats, including those coming from Poland’s eastern borders, and make its networks safer and more robust to cyber risk. The technical preparations for 5G auctions in 700MHz and 3.6GHz have been completed and the auctions can proceed once amendments to cybersecurity laws have been finalised. The government should accelerate the legislative process and conduct the 5G auctions in order to speed up the development of a dedicated 5G network.

Figure 2.10. Network connections are widespread but firms could take advantage of higher speeds

Note: (Panel A) % of enterprises with 10+ employees. (Panel C) The broadband price index measures the prices of representative baskets of fixed, mobile and converged broadband offers. The index is normalised to the range 0 to 100, with 100 being the worst score referring to the highest prices.

Source: OECD ICT database on business usage; and OECD, Broadband Portal, http://www.oecd.org/digital/broadband/broadband-statistics/; and European Commission, DESI 2022.

Ensuring a good regulatory framework

A favourable business environment provides the foundations for digital diffusion and productivity growth (Sorbe et al., 2019; OECD, 2018). In general, Poland has a good business environment with business-friendly regulations and low barriers to trade. However, despite significant reforms over the past two decades, some of its administrative, tax and legal procedures can still present barriers as they take longer than in other OECD countries (OECD, 2022f).

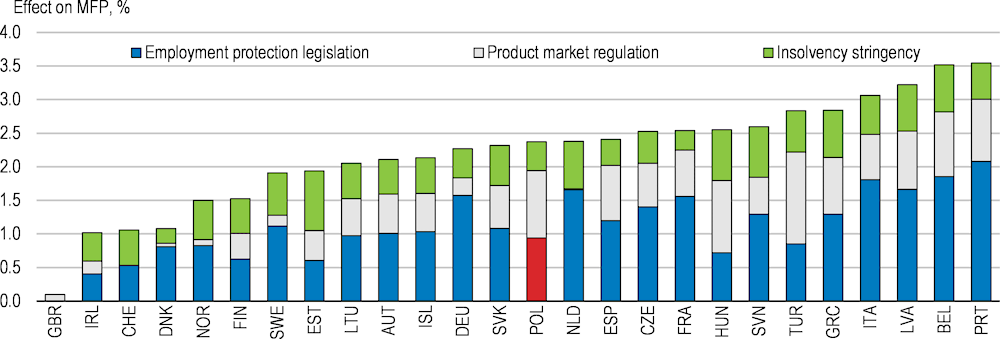

Poland should continue to streamline market regulations to support the digital transition and boost productivity (Figure 2.11). Overall, regulatory barriers to competition are slightly above the OECD average. Government ownership is still relatively high and government involvement is above average. The administrative burden on start-ups is higher than in many OECD countries, making it more difficult to start digital businesses. However, the government has recently been easing the burden through reforms, such as simplifying reporting and tax obligations for smaller businesses.

Figure 2.11. More favourable product and labour regulations could boost productivity

Effect on productivity after three years (through digital adoption) of reducing regulatory barriers to reallocation

Note: Estimated effect on multi-factor productivity (MFP) of the average firm from closing one-fourth of the gap to countries with least stringent labour protection on regular contracts, administrative barriers to start-ups and insolvency regimes.

Source: Sorbe et al. (2019), “Digital Dividend: Policies to harness the potential of digital technologies”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 26.

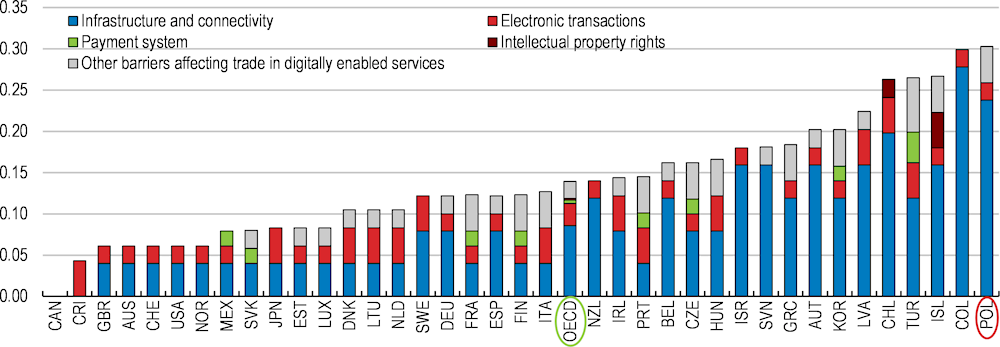

In terms of restrictions on trade in services, Poland is slightly more restrictive than the OECD average and could benefit from more open markets in trade for services. For example, it could relax labour market tests and quotas that apply to natural persons seeking to provide services in the country on a temporary basis as intra-corporate transferees, contractual services suppliers, and independent services suppliers. These may be particularly important for attracting workers and know-how in the digital sector. Digital services barriers are also higher than the OECD average (Figure 2.12). Regulation that limits access to high quality communication services and measures that hinder the seamless transfer of data across borders should also be reviewed.

Figure 2.12. Digital services trade restrictiveness is high and could be lowered

2022

Note: STRI indices take the value from 0 to 1. Complete openness to trade and investment gives a score of zero, while being completely closed to foreign services providers yields a score of one.

Source: OECD Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index database.

Online markets are becoming increasingly important in Poland. The use of online shopping is comparable to the OECD average and has grown strongly during the pandemic. There is a large domestic e-commerce platform, Allegro, competing with global e-commerce platforms such as Amazon. Trust in online payments is high and above the OECD average (OECD, 2022a).

Effective and independent regulation of digital markets is important to support their development. A salient feature of online markets are network effects, which imply that new users will be drawn to platforms that are already large thus leading to further increases in their size. This can be beneficial as it can increase efficiency of market matching and boost growth. But it can also be detrimental to markets as winner-take-all dynamics emerge and lead to a dominance of a few firms, weakening competition and resulting in rent extraction (OECD, 2019d). Competition authorities need to guard against such dynamics while, at the same time, supporting their development by ensuring fair and strong competition.

The Office of Competition and Consumer Protection (UOKiK) has actively pursued consumer infringement cases in online markets. It has also organised educational campaigns for schools such as ‘Konsument.edu.pl’ about safe online shopping behaviour. Such campaigns should be extended to a wider audience. Furthermore, UOKiK has developed recommendations around correcting tagging in influencer marketing. Effective monitoring of online markets requires understanding of new technologies such as algorithms and to this end ensuring sufficient qualified staff will be key. For example, in Japan, the Act on Improving Transparency and Fairness of Digital Platforms promotes transparency to ensure fair online participation in e-commerce (OECD, 2022e). In the field of digital financial services, the Polish Financial Supervision Authority (UKNF) offers regulatory and virtual sandboxes aimed at supporting new financial technology firms. These initiatives can be valuable and should be continued.

Active and timely anti-competition policy is key to ensuring well-functioning online markets. UOKiK works with the European Union to inform its approach and develop its capabilities. It has implemented the ECN+ Directive that will strengthen UOKiK’s independence and grant it more powers. The EU Digital Services Act, entering into force in 2024, will better regulate online platforms and digital services in the Single Market. While the authorities have been active in implementing evidence-based anti-trust regulations, it will be particularly important to guard against ‘killer’ acquisitions, in which larger companies acquire smaller ones for the purpose of reducing competition. For example, German regulatory authorities may require every company in an industry to notify an acquisition (OECD, 2022e). To help develop expertise in digital markets, the authorities could consider establishing a digital markets unit as has been done in the United Kingdom (OECD, 2022e).

Upgrading skills for a digital transition

Digital skills are key for a successful transition

Digital skills encompass a range of abilities to use digital devices, applications, and networks to access and manage information as well as to create new services. Basic digital skills allow for simple access and use of digital devices and online applications for personal and work purposes. They are viewed as a critical component of a new set of literacy skills along with traditional literacy abilities. Advanced digital skills enable the use of complex technologies such as artificial intelligence, machine learning and big data analytics to complement work and develop new applications. Effective digital skills are underpinned by strong literacy and numeracy skills, critical and innovative thinking, complex problem solving, collaborative and socio-emotional skills (OECD, 2016d).

Poland has made great progress in increasing formal educational attainment over time. The share of 25-64 year olds with tertiary education has risen to around 30% in 2021, having been 9% in 2000 and one of the lowest in the EU. During the same period the share of adults with education below upper secondary levels has halved to 13% (Eurostat, 2022b). This has been driven by strong growth in educational attainment among young adults. Since 2000, the share of adults aged 30-34 with tertiary education has more than tripled to around 45% and Poland now has some of the lowest shares of low-educated young adults in the EU (Eurostat, 2022b). Over the past two decades, PISA scores have increased significantly and Poland ranked among the top 10 countries in 2018 (OECD, 2019g).

Yet, a number of adults, particularly among older people, still have low general skills that are likely to limit their ability to learn new digital skills. This can be explained by education and age. Similar to other OECD countries, educational attainment seems to have the largest effect on literacy skills. In Poland, adults with a tertiary education have literacy proficiency scores about 55 points higher than those who have not attained an upper secondary qualification, after adjusting for other differences such as age and parents’ educational attainment (OECD, 2019a). Older adults are more likely to be less skilled than younger adults. For example, the share of adults aged 25-34 with tertiary education was 41% in 2021, near the EU average, but this was around 17% for adults aged 55-64.

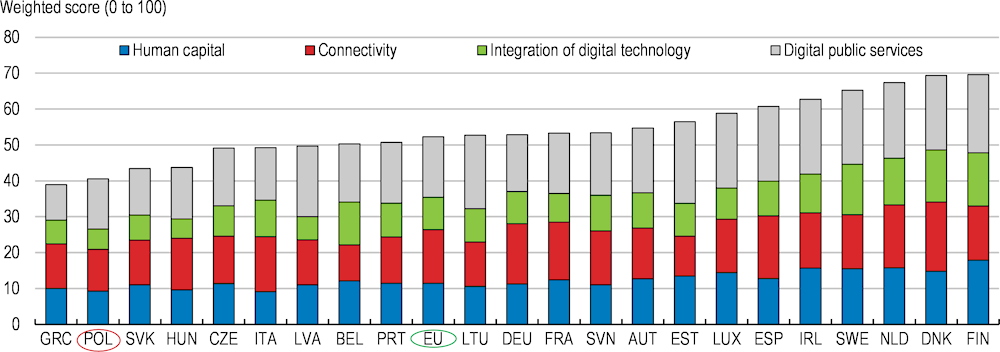

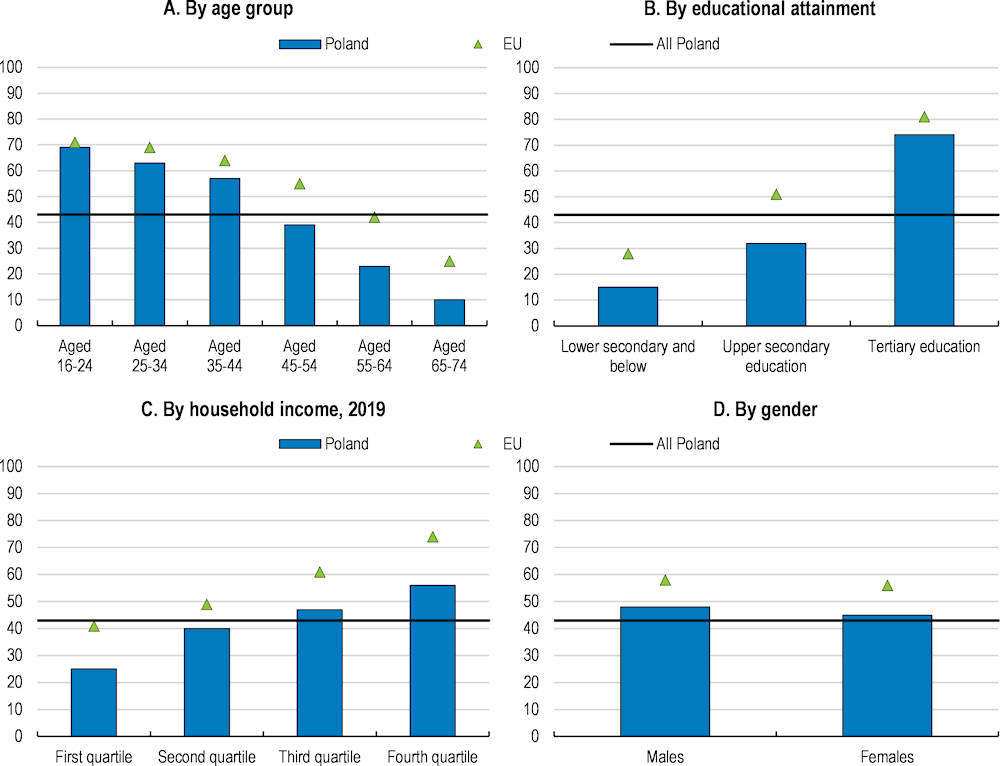

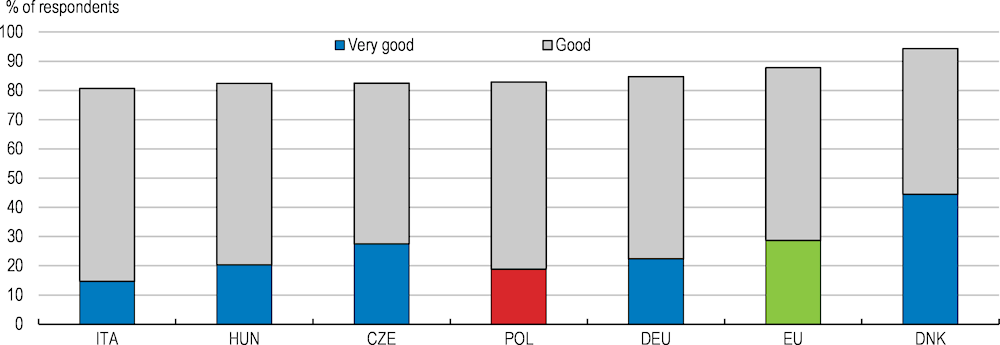

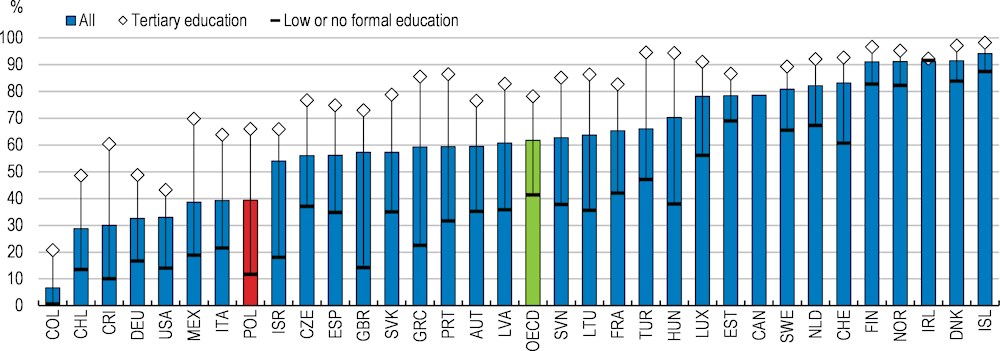

Competency in digital skills reflects the general skills composition of the adult population. Basic digital skills among Poland’s adult population are below the EU average and decline with age. The share of young adults with basic or above basic overall digital skills was between 60-70% in 2021 but this declines to 40% for those aged 45-54 and falls further to 10% for 65-74 year-olds. Digital skills tend to increase with educational attainment. Differences by gender are relatively small in aggregate (Figure 2.13).

Figure 2.13. Digital skills are low among older adults

Share of individuals who have basic or above basic overall digital skills, 2021

Note: Data by educational attainment and by gender refer to individuals aged 25-64.

Source: Eurostat.

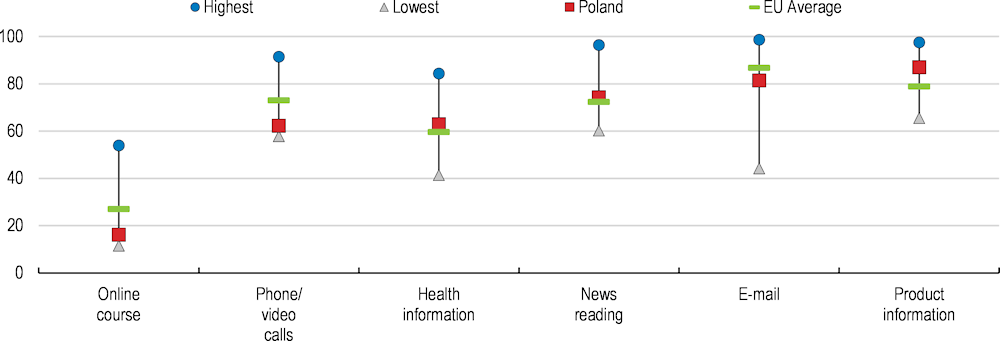

The use of digital skills in Poland tends towards basic and less intensive applications. Around three-quarters of adults use a computer over the year, similar to the EU average. But the proportion of those using the internet on a daily basis is around 60%, some 10 percentage points below the EU average (Eurostat, 2021a). Furthermore, the use of ICT is skewed towards more basic applications (Figure 2.14). For personal purposes, the most common uses are looking for information and using social media. At the same time, the use of some more complex services, such as online public services or e-banking, is much lower. For work purposes, the use of ICT is even lower. Around 40% use word processing software, 27% use software for creating presentations, while 13% use more advanced spreadsheet functions, all lower than the EU average. OIder and less educated adults are less likely to use advanced and intense ICT applications. However, data from the PIAAC survey suggests that problem-solving abilities in technology rich environments have been relatively low and below the OECD average for all age groups (Figure 2.15).

Figure 2.14. The use of digital skills is relatively limited and basic

Share of 25-64 years-olds who used the internet in the last three months, 2022

Figure 2.15. Problem-solving in technology-rich environments has been low in Poland

Problem solving in technology-rich environments by age, individuals in employment

Note: Problem solving in technology-rich environments refers to Level 2 or Level 3 of PIAAC proficiency and measures adults’ abilities to solve the types of problems they commonly face as ICT users in modern societies: co-ordinated use of several different applications, evaluating the results of web searches, and responding to occasional unexpected outcomes. For most countries, data refer to 2012; for Chile, Greece, Israel, Lithuania, New Zealand, Slovenia and Turkey, data refer to 2015. Population weighted average used for the OECD aggregate.

Source: OECD Survey of Adult skills (2012 and 2015).

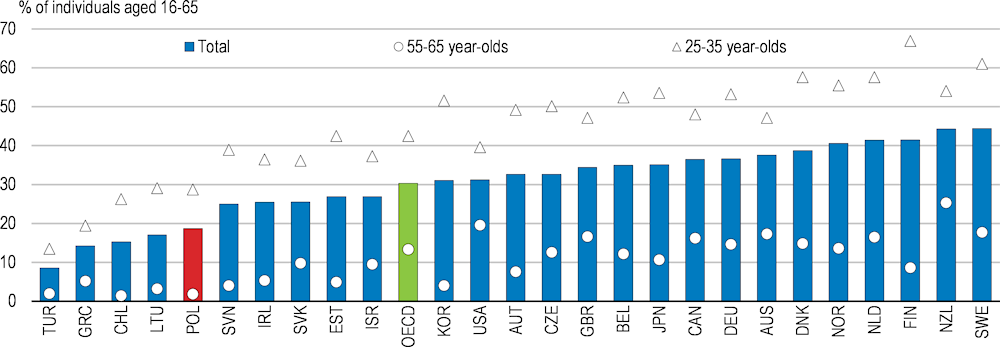

In order to use and benefit from new digital tools, people need to learn new skills. Around half of existing jobs are at risk of automation (Figure 2.16). Adults will need to upgrade their skills to adapt and benefit from evolving needs in the labour market, while some will need to re-skill. Without the requisite skills, digitalisation can reduce wages for some or lead to higher unemployment, potentially excluding and harming parts of society and exacerbating existing inequalities. The Integrated Skills Strategy 2030, adopted in 2019 and partly based on the OECD Skills Strategy for Poland (2019a), provides a national framework that guides skills development. The upcoming “Digital Competence Development Programme until 2030” will aim to increase the level of digital skills for work and personal applications.

Figure 2.16. Many Polish workers are exposed to digitalisation

Share of jobs that are at a high risk of automation or at risk of significant change (%)

Note: Jobs are at high risk of automation if the likelihood of their job being automated is at least 70%. Jobs at risk of significant change are those with the likelihood of their job being automated estimated at between 50 and 70%. Data for Belgium correspond to Flanders and data for the United Kingdom to England and Northern Ireland.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012); and Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), "Automation, skills use and training", OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202, https://doi.org/10.1787/2e2f4eea-en.

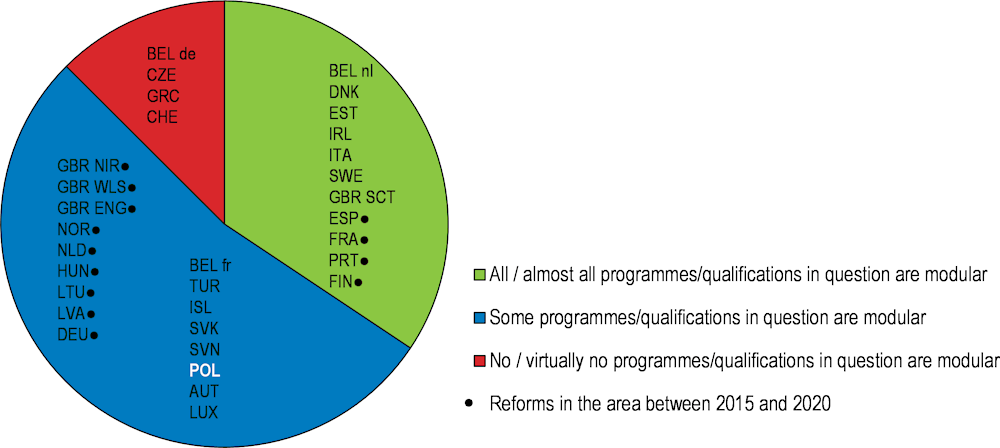

Expanding digital skills in vocational education and training

Nearly half of young Poles possess vocational and education training (VET) qualifications, higher than the EU average with almost a half studying towards engineering, manufacturing, and construction qualifications. The level of digital skills among the young (16-24 years old) with upper secondary education is lower than in the best performing European countries such as Greece and Slovakia (Figure 2.17). To boost the level of digital skills among VET graduates, policies should focus on ICT teaching capacity and equipment. Teachers’ digital competencies are instrumental for their students’ capacity to make the most out of new technologies. There is a significant positive relationship between teachers’ problem-solving skills in technology-rich environments and students’ performance in computer problem solving and computer mathematics (OECD, 2019a). The pandemic has also highlighted the need for adequate ICT equipment in schools in order to teach digital skills and teach in a digital environment.

Figure 2.17. Young workers with VET qualifications have weaker digital problem-solving skills

% 16-24 year olds with upper secondary education who have basic overall digital skills*, 2021

Note: *All five component indicators are at basic or above basic level, without being all above basic.

Source: Eurostat (isoc_sk_dskl_i21).

The role of local employers in the development of digital education could be further strengthened. Poland established sectoral skills councils that bring together educational sector representatives, employers, and other social partners. Their aim is to monitor, identify and define skills required in different sectors in order to help shape formal education curricula and market development services. This should make it easier for firms to hire skilled workers. For example, core curricula for ICT VET were developed in close cooperation with the ICT sector. Since 2019 a new qualification, “technical programmer”, is offered and schools teaching this programme receive additional funding. Overall, almost 20% of students (134,000) in technical upper secondary schools are studying towards ICT-specific qualifications. In addition, the skills councils advise authorities on skill gaps in the private sector, which then informs the design of training and advisory services programmes operated by PARP. The number of sectoral councils is to expand from 17 to 27 and they are financed by EU funds until 2027. Given their importance, funding should be ensured on a continuous basis. In addition, given they are relatively new, they should be evaluated with experiences and the different councils should share experience and best practices.

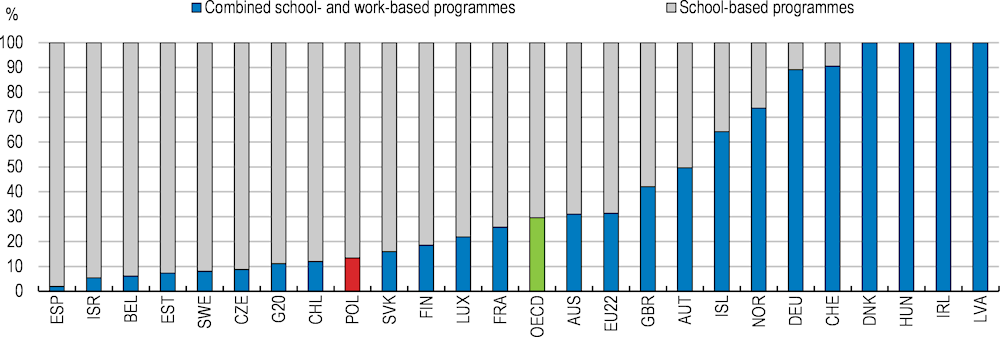

To boost digital skills the role of work-based learning in VET programmes could be expanded. Polish schools are legally obliged to cooperate with employers including on work-based learning. In principle, VET students training in the industry should have access to the latest technologies, which could help them develop more advanced and applied digital skills, complementing what they have learned in school. In Poland, most of the VET programmes are school-based although the latest statistics underestimate the importance of work-based learning, due to methodological issues (Figure 2.18). In countries with strong apprenticeship systems, such as Germany and Switzerland, around 90% of programmes combine school and work. Polish VET students that attend a mixed programme spend nearly half their time in industry. VET programmes could include more work placements in digitally advanced firms and the legal requirements for schools to cooperate with employers should encourage more work-based learnings. Monitored use of such work placements could boost students’ digital skills.

Figure 2.18. Work-based VET learning could be more prominent

Distribution of upper secondary VET students by type of vocational programme, %, 2020

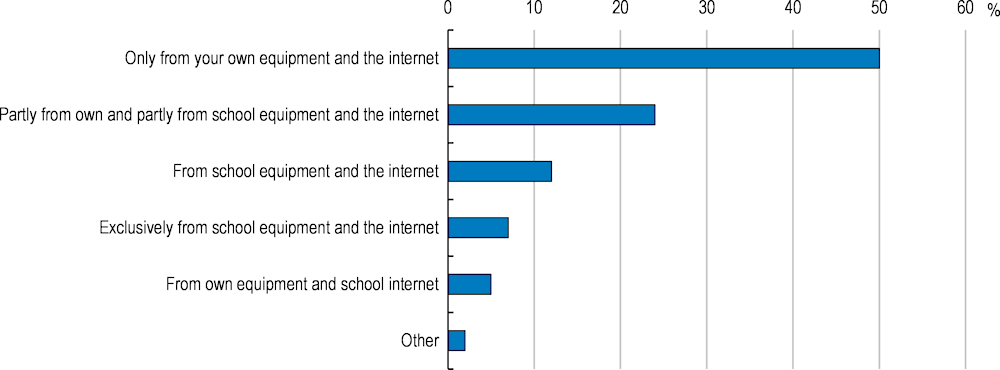

Poland has made progress in providing ICT education in VET and the wider school system. ICT equipment, online educational resources and teachers’ digital skills have been improved through the Active blackboard (“Aktywna tablica”) and Laboratories of the Future (“Laboratoria przyszłości”) projects, the Integrated Education Platform, and the Nationwide Education Network. This has been funded by EU and national budgets. The share of teachers taking digital education training doubled between March and September 2020, reaching 81% (NIK, 2021). However, some schools were still inadequately equipped. The Supreme Audit Office (NIK) found that in 2020/21, 25% of schools had average or poor ICT equipment. Half of teachers indicated that they used private equipment and internet access to teach remotely (Figure 2.19). When asked about improving digital education, two-thirds of teachers suggested that having a laptop with an internet connection would be useful. They also reported that better quality (31%) and greater availability (25%) of training on digital education and its integration in initial teacher education would help (EC, 2021b). Currently, two large projects, covering 105,000 teachers, are supporting the development of teachers’ digital skills and training in providing distance education. Poland should continue to increase its technical and teaching educational capacity in schools for ICT. VET teachers could also be given specific support to teach practical ICT skills. A good example is Denmark, where dedicated support centres have been established for VET teachers (see Box 2.3).

Skilled teachers are crucial for delivering high-quality education in this context. Poland has experienced teacher shortages while the appeal of the teaching profession remains low. In 2020/21, 46% of surveyed schools had problems with recruiting qualified teachers, mostly for physics, mathematics, chemistry, English and computer science. While vacancies accounted for 1% of all teaching jobs, the staffing needs were greater in larger cities. Shortages were addressed mostly through overtime work, employing retired teachers and people without the necessary qualifications (EC, 2021b). Polish teachers’ enthusiasm in teaching is among the lowest in the European Union (OECD, 2019a). The range of teachers’ salaries, adjusted for purchasing power, is similar in Hungary and Czech Republic but is below most EU countries (Eurydice, 2022). However, the authorities provide incentive payments and allowances for performance and starting salaries were increased by around 25% in 2022. To ensure high quality teaching capacity, the authorities should continue to ensure the attractiveness of the teaching profession.

Box 2.3. Specialised centres to promote technology use in VET in Denmark

The “Knowledge Centre for IT in Teaching” promotes the use of digital technologies in VET by supporting teachers in the use of IT across all subjects. The Danish government created two Knowledge Centres for Automation and Robot Technology, promoting innovation in education and industry and helping VET schools make use of advanced technologies. Each centre works with over a dozen nearby VET schools. They provide teachers with educational material, such as teaching tutorials or short courses in Industry 4.0 and robots. Specialised facilities are used to demonstrate the use of robots to teachers and students. The centres lend digital machinery to VET teachers, provide them with training materials and technical support, with the objective of enabling teachers to set up and operate these technologies and incorporate them into their teaching practice. The centres also provide technological resources for VET programmes in the areas of industrial automation, mechanics, electronics, welding, data and communication, and education. The centre also has a network of pedagogical staff and a network of school leaders to facilitate the exchange of ideas, practical and technical knowledge, and help identify solutions to common challenges.

Source: (OECD, 2021d).

Figure 2.19. Schools need to be better equipped with ICT

Use of ICT equipment in teaching during 2020

Universities could provide more ICT specialists

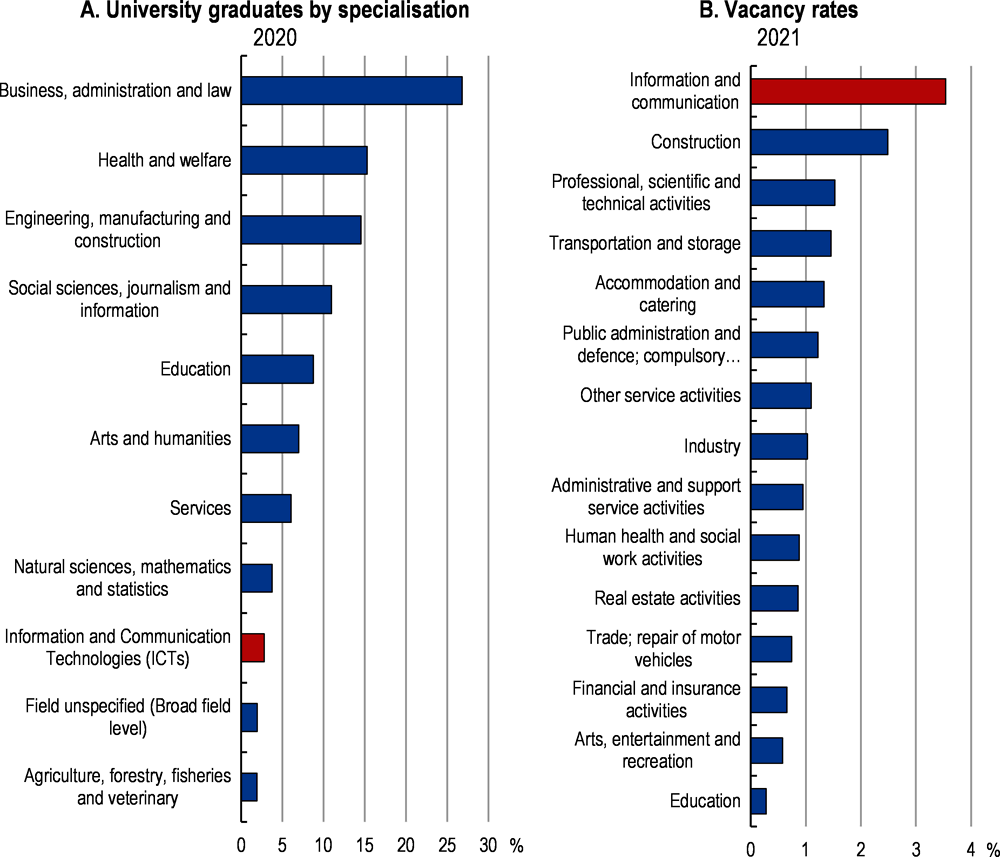

The main constraint for the Polish economy appears to be the inadequate supply of ICT graduates. In 2019, only 3% of Polish university graduates (around 4,500) specialised in ICT. But the demand for jobs in the ICT sector was much stronger. In 2019, there were 7,500 ICT vacancies, accounting for around 2.2% of all employment in the ICT sector. By 2021, the number of vacancies had risen to 12,000 or 3.5% of all ICT jobs. This was the highest vacancy rate across all sectors (Figure 2.20). Demand for ICT specialists has risen due to a rapidly growing ICT sector, in which employment rose by 60% between 2012 and 2021. Salaries for ICT workers are 60-70% higher than the national average salary (Statistics Poland, 2021). The shortages will partly be addressed by new VET ICT programmes but universities could also raise the number of ICT graduates.

Figure 2.20. There are many vacancies in ICT and not as many ICT graduates

Universities can also boost digital skills through more flexible programmes. Dual degrees that combine ICT with other disciplines might increase the number of graduates with relevant ICT qualifications. Students in science, engineering and mathematics are well placed to also learn ICT skills. The Higher Education and Science Act allows higher education institutions to cooperate with professional industry bodies and employers in the development of new qualifications. This gives universities flexibility to adjust degrees in other areas such as business, which could offer ICT specialisations or recognised certificates. In general, universities could offer more certified programmes in ICT, which could be integrated into official programmes or offered as micro-credentials to adults who have already graduated (OECD, 2021a).

To increase the number of ICT graduates and to increase gender equality, Poland should encourage more women to study ICT. Within the EU, ICT employment remains dominated by men. The share of female ICT specialists in Poland is around 15%, similar to the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary. However, it is below the EU average of 19% and almost twice as low as in Romania and Bulgaria (Figure 2.21). The Perspektywy Education Foundation has organised a national campaign called “Girls and Engineers!” and “Girls go Science” in cooperation with the Conference of Rectors of Polish Technical Universities. The campaigns involved 150,000 girls and promoted technical and engineering studies among high school girls. This boosted the share of women in STEM programmes from 29% to 37% (EIGE, 2022a). The Foundation also runs activities such as “Lean in STEM”, “Girls Go Start-Up! Academy”, “Girls to Learn!”, “IT for She”, and a scholarship programme for IT students, “New Technologies for Girls” (EIGE, 2022b). Poland has a number of active NGOs and professional organisations supporting women in ICT. To further boost the number of female ICT specialists similar targeted campaigns should be continued and expanded but aimed specifically at ICT. Even though university attendance is free, the government or businesses could offer additional scholarships to female ICT students.

Figure 2.21. There are relatively few women in ICT in Poland

Women ICT specialists share, 2021

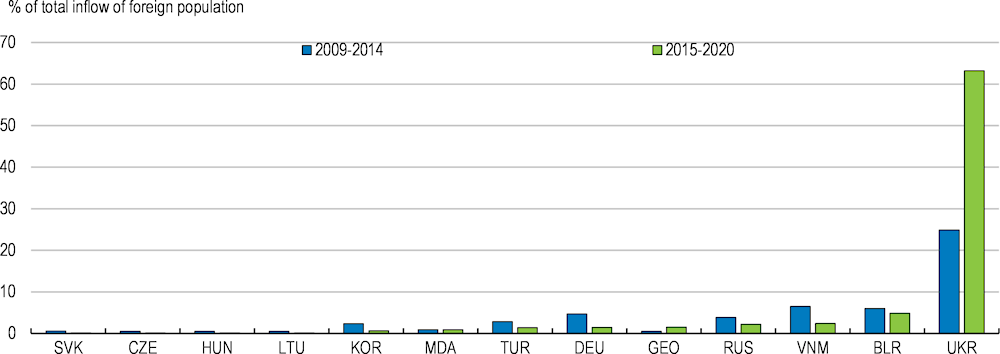

Migration could help to increase the supply of ICT specialists relatively quickly. Polish ICT graduates have strong incentives to emigrate to other EU countries. Despite the ICT sector paying the highest salaries, Polish ICT salaries are below the EU average and considerably lower than in neighbouring Germany. However, Poland has become an attractive country to work in, which is illustrated by an increase in immigration since 2014 (Figure 2.22). This was mostly driven by Ukraine but also by immigration from Belarus, Moldova, and Georgia. To attract ICT professionals, the government launched a new programme “Poland. Business Harbour” to draw in ICT entrepreneurs and specialists from Belarus and later expanding to Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, Russia and Ukraine. The programme has now been extended globally. Polish companies must be approved before they can sponsor ICT workers and currently 200 firms can do so. The challenge for the government is to increase the number of firms that can hire migrant ICT specialists and ensure there is sufficient technical capacity to process higher numbers of migrant worker visas. In this regard, the government could focus its resources on key countries, such as India.

Figure 2.22. Immigration has increased over the past decade

Note: Includes permanent and "fixed-time" residence permits.

Source: OECD Migration database.

Lifelong and life-wide learning can address digital skill gaps among adults

Targeted and relevant adult learning can address many of the digital skill gaps in Poland associated mainly with older adults. This learning should be lifelong, accessible to everyone at any age, and life-wide, encompassing learning outside of formal education systems, which is the main mode of learning for adults aged over 25. Adult lifelong and life-wide learning can take different forms and occur in various environments. Effective adult learning systems are crucial for developing and updating skills in response to digitalisation (OECD, 2019a).

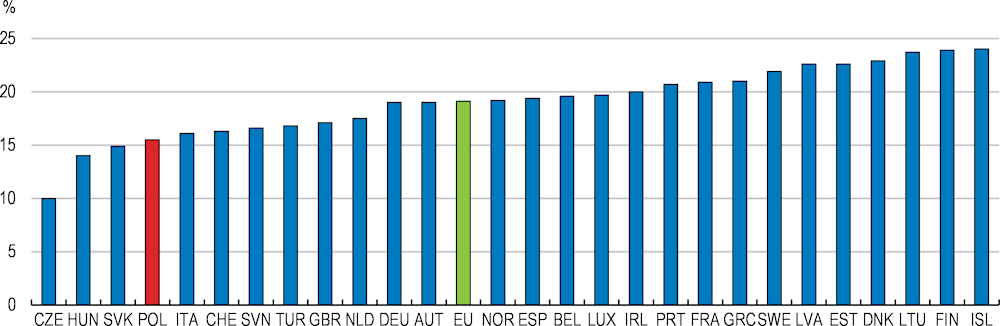

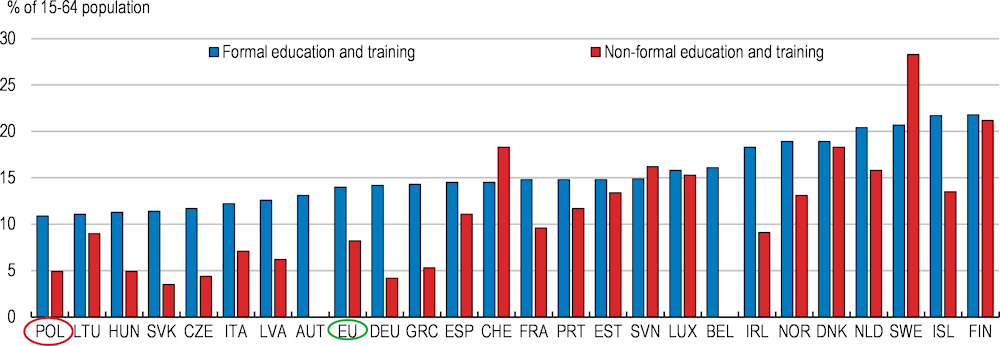

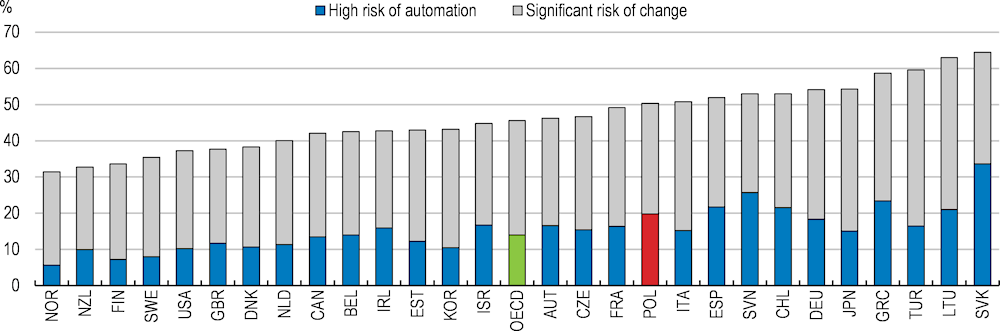

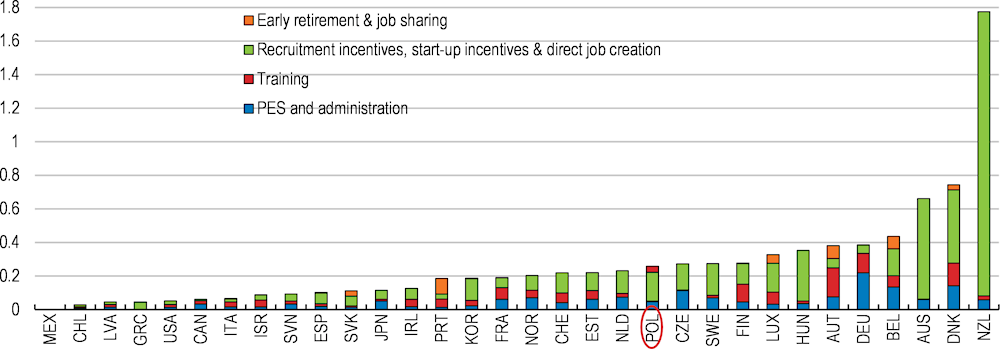

Participation in adult learning is relatively low. In Poland, most learning during the course of adults’ lives is non-formal. According to the latest Adult Education Survey (AES), only 4.4% of adults participated in formal training in 2016, which is learning that leads to a qualification, broadly in line with the EU average. More adults learned non-formally and 23% learned through on-the-job training, other forms of work-based learning, workshops, seminars and organised distance learning as well as through social involvement. Around 30% of Polish adults learned informally from colleagues, family or by themselves. More recent Labour Force Survey data show that adult participation in formal learning has remained low in 2022, relative to other EU countries (Figure 2.23). National BKL survey data, based on broader definitions of adult learning, points to higher rates of participation as most adults aged 25-64 develop their skills through non-formal and informal learning.

Low demand, rather than limited supply, is holding back adult participation in organised training. In Poland, as in other OECD countries, low levels of motivation to learn lead to low demand for training. According to the AES, around 60% of adults reported that they did not participate, and do not want to participate, in formal and/or non-formal education. A further 15% reported they did participate but did not want to participate more. Overall, the share of adults uninterested in formal and/or non-formal education is around the EU average. But few adults report that there is a lack of suitable learning opportunities or that distance was an obstacle to training (OECD, 2019a). According to the BKL, less than 10% of adults indicated that relevant organised training was not available close to them, and a few per cent said that the existing training offers were not useful to them (BKL, 2020).

Figure 2.23. Adult participation in formal learning is low in Poland

Adult participation in learning in the last 4 weeks, as % of the population aged 15-64, 2021

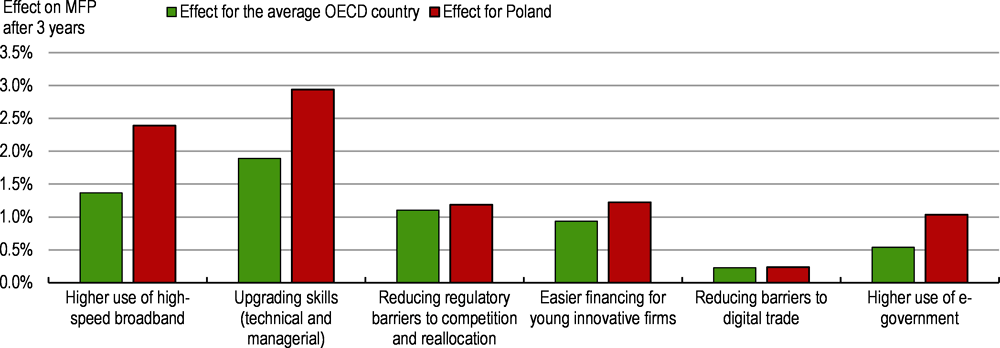

The main reason holding back demand for participation in organised adult learning is an absence of a perceived need for further training (BKL, 2022a). For those working adults who wanted to participate but did not, the most commonly cited obstacles were family responsibilities and scheduling issues (Figure 2.24). The cost of education was also frequently cited as an obstacle. The interest in developing professional competence declines with skill levels. For example, 70-80% of those in managerial and professional occupations show interest in training. In contrast, only 40% of service and sales workers reported any interest in further education and this fell to 26% among unskilled workers. Older adults with low levels of education see little incentives to continue learning (BKL, 2022a).

Policy needs to reduce informational frictions that lead to perceptions of low returns to learning, improve matching the supply of adult education and training to demand, and effectively support the development of general digital skills, especially among those less skilled. Many Polish workers and firms perceive that the return to investing in digital skills is lower than the cost of the investment, despite high returns in terms of wages and employment. Various policies such as awareness campaigns, engagement with social partners to promote learning and targeted guidance, can be effective in motivating adults to participate in education and training (EC, 2015). These take different forms across OECD countries (OECD, 2019a). In-depth case studies suggest that raising awareness of the benefits of adult learning can increase participation and boost workers’ earnings (EC, 2015).

Figure 2.24. Family and scheduling reasons are obstacles to adult participation in training

Obstacles to adult participation in formal and non-formal education and training, 2016

To reduce informational frictions, OECD countries have used awareness campaigns (Table 2.1). Poland carried out a comprehensive nationwide campaign called Edurośli in 2019. This involved around 300 events spanning from conferences, seminars, workshops, open days, and meetings to shows, competitions and webinars and covered a range of topics. The campaign brought together different stakeholders such as government ministries, NGOs, schools, sports clubs, museums, libraries, community centres and local activists (MoES, 2019). The goal of the campaign was to emphasise the importance of continuous education and foster positive attitudes about lifelong learning as well as to increase participation in adult education. However, a lack of formal evaluation makes it unclear to what extent this was achieved. It also appears that such campaigns are organised ad hoc. To raise the level of digital skills, smaller, sustained and targeted campaigns that include social partners might be more effective in reaching those adults who stand to benefit and whose jobs could be at risk due to digitalisation (OECD, 2019a).

Table 2.1. Public awareness campaigns and their focus in selected OECD countries

|

Focus |

Name |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

General Adult Learning |

Specific Programmes |

Specific Target Groups |

Basic Skills |

High-demand Skills |

Firms |

||

|

Estonia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Jälle Kooli (Back to school again) |

||

|

Germany |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Zukunftsstarter (Future starter) Nur Mut (Courage) |

||

|

Hungary |

X |

Hivatások éjszakája (Night of Vocations) |

|||||

|

Ireland |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Take the first step |

||

|

Korea |

X |

X |

X |

Vocational skill month |

|||

|

Portugal |

X |

X |

X |

Qualifica |

|||

|

Slovenia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Lifelong learning week |

||

|

Switzerland |

X |

X |

X |

Simplement mieux (Simply better) |

|||

Source: OECD (2019), Getting Skills Right: Future-Ready Adult Learning Systems https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264311756-en.

To improve matching of the supply of and demand for adult education, better coordination is needed. The responsibility for supplying adult education and training is spread across several institutions and should be coordinated. At the national level, the ministries responsible are the Ministry of Education and Science (MEiN), the Ministry of Family and Social Policy (MRiPS), the Ministry of Economic Development and Technology (MRiT), and Digital Affairs at the Chancellery of the Prime Minister. At the sub-national level, regions (voivodeships), and counties (powiat) have responsibility for formal educational facilities (OECD, 2019a). To maximise the impact of education policy, there should be effective coordination and information sharing. Social partners are also important for that process. Chambers of commerce and trade unions disseminate information, organise and support adult education and training for their members. Social partners participate in discussions and co-ordination of adult learning sectoral skills council and the Program Council on Competences (OECD, 2019a).

Regular and thorough evaluation of learning should be standard across all modes and providers. Formal and non-formal education is delivered by a diverse range of formal public education and training institutions and thousands of private providers of adult education and training. Informal learning is less structured and often self-taught. Learning methods also vary widely from teaching in classrooms to online learning and practical learning in the workplace from colleagues, family, and friends. More thorough and rigorous evaluation of education and training provision might identify effective ways of upskilling and re-skilling. Poland has already set up a graduate tracking portal (ELA) that provides additional information on the labour market outcomes of graduates from different disciplines in formal education. A similar tracking portal was developed in 2021 for Vocational Education and Training (VET) graduates. PARP regularly monitors and evaluates the Database of Development Services (BUR) that offers training to firms. However, there appears to be little rigorous analysis of the impact of adult training on labour market outcomes. Such analysis would help adults better choose their training and would better inform public funding and support for adult training programmes.

Digital skills may also provide a pathway to better employment for disengaged adults. However, they may be unable or unwilling to use public employment support services, or they can be overwhelmed by the range of training on offer. Guidance and counselling can be helpful (OECD, 2021f). Public employment services at the county (powiat) level are major providers of guidance services for the unemployed. Centres for information and career planning in regional (voivodeship) labour offices provide services to all adults. Employment agencies (Agencje zatrudenienia) provide jobseekers and employees with employment support and counselling while voluntary labour corps (Ochotnicze Hufce Pracy) make provisions for (disadvantaged) young people. Adults can receive guidance from education institutions directly as well as from non-governmental or private organisations (OECD, 2019a).

Counselling and guidance in Poland could be more extensive, detailed and proactive. The number of career advisers available to adults is low (OECD, 2019a). In 2017, there were 2,144 career advisers in the public employment service which equated to one adviser for 505 unemployed people. This declined in 2021 to fewer than 1700 advisers, increasing the number of jobless per adviser to 536 on average. In the past, career advisers did not fully assess and identify adult learning needs (Euroguidance, 2018). Such guidance should also be proactive and reach out to adults whose skills are most at risk of becoming obsolete. Some programmes do, however, reach out to adults to motivate them to learn (Box 2.4). While such projects are welcome, it is important that they are thoroughly evaluated.

Box 2.4. Reaching and training adults from disadvantaged backgrounds in Poland

The ‘Lokalne Ośrodki Wiedzy i Edukacji’ or LOWE (Centres of knowledge and education) is a project that aims to reach parents and other adults in local communities in disadvantaged areas with difficult access to education in order to help them develop basic skills and other key competences to boost their prospects in the labour market, in the community and in their families. Equally important to encourage various institutions and organisations to increase adult training partly by developing methods and tools used by educators to work with adults. It is a collaboration between schools and local communities designed to offer non-formal education to adults in a variety of ways teaching many different competences, including digital skills.

LOWE supports adult education through finance and operational support. Five experienced organisations and institutions from Białystok, Bydgoszcz, Lublin, Krakow and Poznań were selected through a competition as organizers of 15-20 LOWE. The selected local educational organisations manage schools and support them with financial grants including substantive support such as a diagnosis of skills needs that forms the basis for educational offers. The programme conducts an assessment of the social environment, skills gaps and educational capabilities in each local area and provides organisational support to each LOWE centre through helping with management, training staff, communication, and promotional activities. Each selected organisation can receive a grant up to PLN 250,000 or around EUR 52,000 (LOWE, 2022).

LOWE has expanded over time. In 2016-18, a pilot programme of 50 centres across 13 regions managed to successfully get 3700 adults to attend organised training, who previously did not participate or did so infrequently. The programme was then repeated in 2019-22 with 100 centres spread across all regions. It was financed jointly by Polish schools and the EU social funds.

Firms need to develop workers’ digital skills

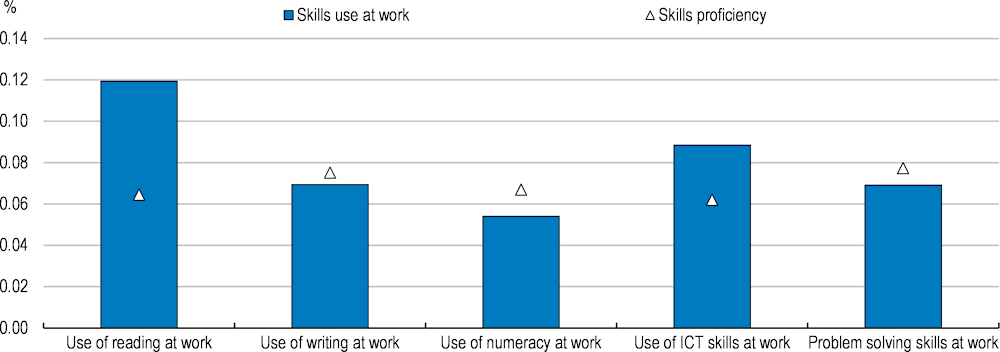

The returns to increasing skills can considerably boost wages and productivity. A higher level of skills and a more intensive use of skills within firms is associated with higher wages. Firms can play a key role in developing and using these skills. The highest increase in wages is associated with more use of reading skills at work. More intense use of ICT is complementary to basic skills and boosts wages the more it is used at work (Figure 2.25). This could be particularly beneficial for older workers and less educated workers.

Figure 2.25. Wage returns to skills use and skills proficiency in Poland

Percentage change in wages associated with a standard deviation increase in skills proficiency and skills use

Notes: A) One standard deviation corresponds to the following: 2.9 years of education; 47 points on the literacy scale; 53 points on the numeracy scale; 44 points on the problem solving in technology-rich environments scale; 1 for reading use at work; 1.2 for writing and numeracy use at work; 1.1 for ICT use at work; and 1.3 for problem solving at work.

B) Estimates from OLS regressions with log wages as the dependent variable. Wages were converted into USD PPPs using 2012 USD PPPs for private consumption. The wage distribution was trimmed to eliminate the 1st and 99th percentiles. All values are statistically significant. The regression sample includes only employees. Other controls included in the regressions are: age, age squared, gender and whether a respondent was foreign-born or not. Skills proficiency controls are the following: literacy for reading and writing at work, numeracy for numeracy at work and problem solving in technology-rich environments for ICT and problem solving.