Occupational licensing and non-competition agreements are two important types of labour market regulation in the United States, both covering around one fifth of all workers. While some regulation is needed to protect safety and ensure quality of services, it also creates entry barriers and reduces competition with important costs for job mobility, earnings and productivity growth. Employment opportunities for low-skilled workers and disadvantaged groups tend to be particularly affected by these barriers. The States are mainly responsible for labour market regulation and the variation across States is similar to the variation in the European Union. Harmonising requirements and scaling back occupational licensing as well as restricting the use of non-competition covenants could help to circumvent the secular decline in dynamism. However, attempts to reform often face stiff opposition from associations of professionals. The federal government has limited influence, but can in some cases help by shifting the burden from workers to meet regulatory requirements onto States and employers to show that high and differing regulatory standards are needed.

OECD Economic Surveys: United States 2020

3. Anti-competitive and regulatory barriers in the labour market

Abstract

Labour market fluidity has declined substantially since the late 1990s and coincides with a period of sluggish productivity growth as discussed in Chapter 2. State-level labour market regulation contributes to some of the concerning lack of dynamism, notably occupational licensing and non-competition agreements, which both cover around one fifth of American workers. Labour market regulation plays an important role in protecting workers and consumers and ensuring well-functioning markets. Too much regulation can however result in excessive entry barriers and reduced opportunities for jobs, mobility and entrepreneurship.

The coronavirus pandemic revealed the barriers occupational licensing can create are harmful requiring action to reduce their impact. Many of the health occupations in high demand are regulated in a way that limit the flow of skilled professionals across State borders. States responded to the crisis by waiving many licensing requirements, by allowing out-of-State licensed professionals to obtain temporary emergency licences to practice and by asking retired health workers or students close to graduation to practice on a temporary basis without a licence (NCSL, 2020; FSMB, 2020).

Occupational entry regulations are widespread in many OECD countries and recent evidence suggests detrimental effects for productivity growth (von Rueden et al., 2020). The reason is that entry barriers lower competition pressures to innovate and reduce reallocation of workers from low to high productive firms. Workers with an occupational licence tend to benefit from higher wages, which has some appeal given persistently weak wage growth. However, low-skilled workers, ethnic minorities and workers with weak labour market attachment are much less likely to hold a licensure and benefit from the higher earnings. The rising use of non-competition agreements (between an employer and an employee) likewise tend to deprive these groups the most by reducing their employment options and wages.

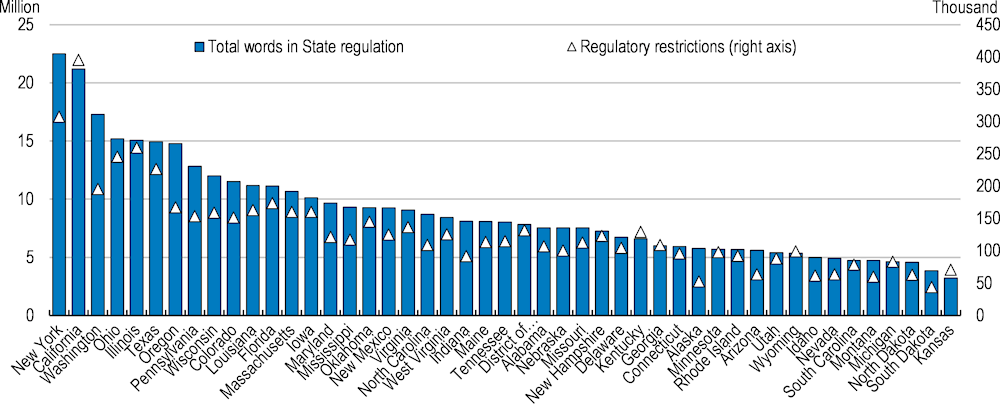

The amount and strictness of all types of regulation vary enormously across States judged by a simple word count of administrative codes (Figure 3.1). With almost 23 million words, New York has seven times the amount of regulation as Kansas. Focusing on restrictive words only, California has almost 400,000 regulatory restrictions, nine times the count for South Dakota. Nevertheless, more words of regulation is not necessarily associated with weaker mobility and poorer economic outcomes. Differences in regulation can potentially provide a spur to competition between States and allows for learning through experimentation. On the other hand, persistent differences may suggest that certain States are not adopting best practices.

Figure 3.1. The total amount of regulation varies substantially across States

Word counts from scan of State administrative codes, 2015-2019

Note: The number of regulatory restrictions is based on the count of the specific words (shall, must, may not, required, and prohibited). Data not available for Alabama, Hawaii, New Jersey and Vermont.

The extent to which State-level regulation can create barriers is constrained by federal law. In some areas, such as competition policy, the federal authorities have an important role. In addition, as previously regulated industries, such as telecommunications and transportation, were deregulated, restrictions were introduced on States’ ability to introduce new regulation. Where they were not, such as trucking, strong interest groups pushed for State level regulation to protect their markets. In other areas, federal government reach is more limited. For example, environmental regulation is an important area where State-level regulation largely determines costs to businesses and has contributed to large differences in stringency emerging across the country (Keller and Levinson, 2002). In other cases, professional groups have sought to use regulatory policy to erect barriers to entry (Teske and Provost, 2014). This is most apparent with the growth of occupational licensing.

This chapter zooms in on two important types of labour market regulation, occupational licensing and non-competition agreements, both mainly governed by States. It presents new empirical evidence on the links with job mobility and discusses how reforms can increase opportunities for workers and boost dynamism and productivity growth. No-poaching agreements (between two employers) has a similar effect on worker mobility as non-competes and are used in more than half of all major franchisors’ contracts, such as McDonald’s and Burger King (Krueger and Ashenfelter, 2018). The Chapter does not discuss these type of arrangements, among others because no-poaching agreements between independent firms are generally illegal.

Reforming occupational licensing to boost mobility and opportunities for all

Occupational licensing is a form of regulation by which the government establishes qualifications required to practice a profession, usually including specific education, exam and work experience criteria. Only licensed professionals are then legally permitted to carry out the activities reserved by the specific occupation and use the protected title. Typically, this aims at protecting safety and health of consumers and ensuring quality of services. Most countries regulate professions like doctors, dentists and lawyers, but also electricians, engineers and real estate agents are licensed in many countries.

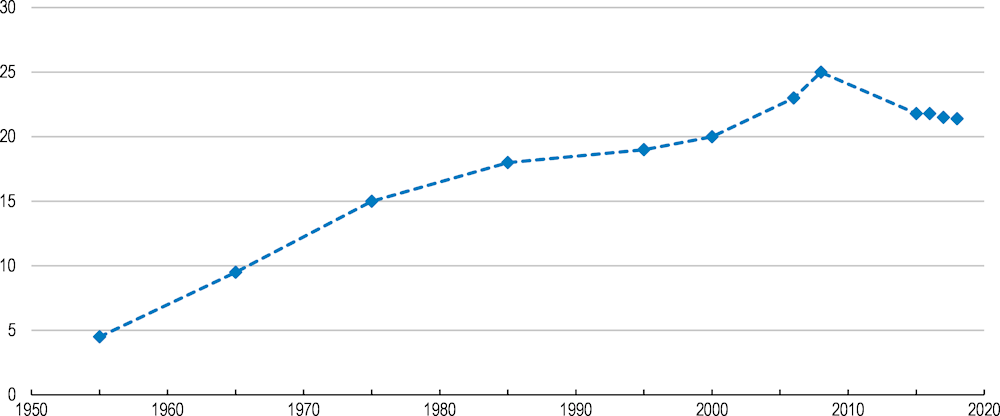

The prevalence of occupational licensing has grown markedly over time in many OECD countries. Today more than 20% of American workers are licensed, up from around 5% in the early 1950s (Figure 3.2). In part, this reflects the growing share of occupations that are typically licensed, including many services not least in healthcare. Calculations suggest that this compositional effect accounts for around one third of the increase from the 1960s to 2008 (White House, 2015). The spread of licensing to new occupations thus explains the majority of the expanding coverage of the workforce.

Figure 3.2. Occupational licensing now covers more than 20% of workers

Percentage of workers holding an occupational licence

Note: Based on various different sources and includes licences issued at all levels of government. The peak around 2008 may reflect methodological differences as well as cyclical factors (unlicensed workers laid off disproportionately during the recession).

Source: White House (2015); BLS.

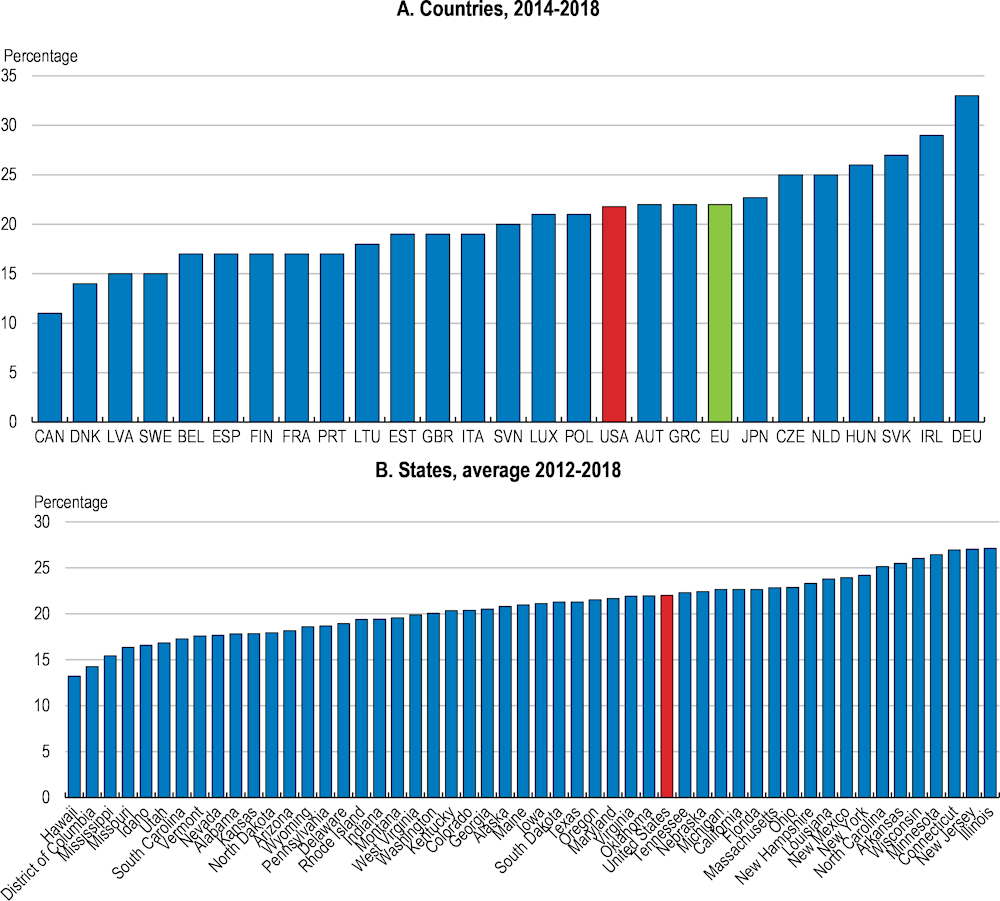

The coverage of occupational licensing in the United States is very similar to the European Union (EU) and Japan with close to 22% of workers licensed, but lower than in some countries, including Germany with the highest observed share (Figure 3.3, Panel A). Most of the licensing in the United States is imposed at the State or local government level. Unfortunately, the United States does not produce statistics of licensing coverage at the State level. Estimates prepared for this Survey suggest that the variation within the United States is almost as large as across the European Union (Figure 3.3, Panel B), ranging from 15% in some States (Hawaii and Mississippi) to almost 30% in others (Illinois and New Jersey).

Figure 3.3. The coverage of licensing and variation across States are similar to the EU

Note: Panel A shows the share of workers holding a licence as a percentage of total employment in the country, including licences issued across all levels of government. Data refer to 2014 for Canada; 2015 for EU countries; 2016 for Japan; and 2018 for the United States. Panel B shows an estimated share of workers holding a licence issued at the State level only and is based on a mapping of licences to occupational employment statistics, cf. Hermansen (2019).

Source: Current Population Survey, BLS; Koumenta and Pagliero (2017) based on the EU Survey of Regulated Occupations; Morikawa (2018); Zhang (2019); Hermansen (2019) based on careeronestop.org and Occupational Employment Statistics from BLS.

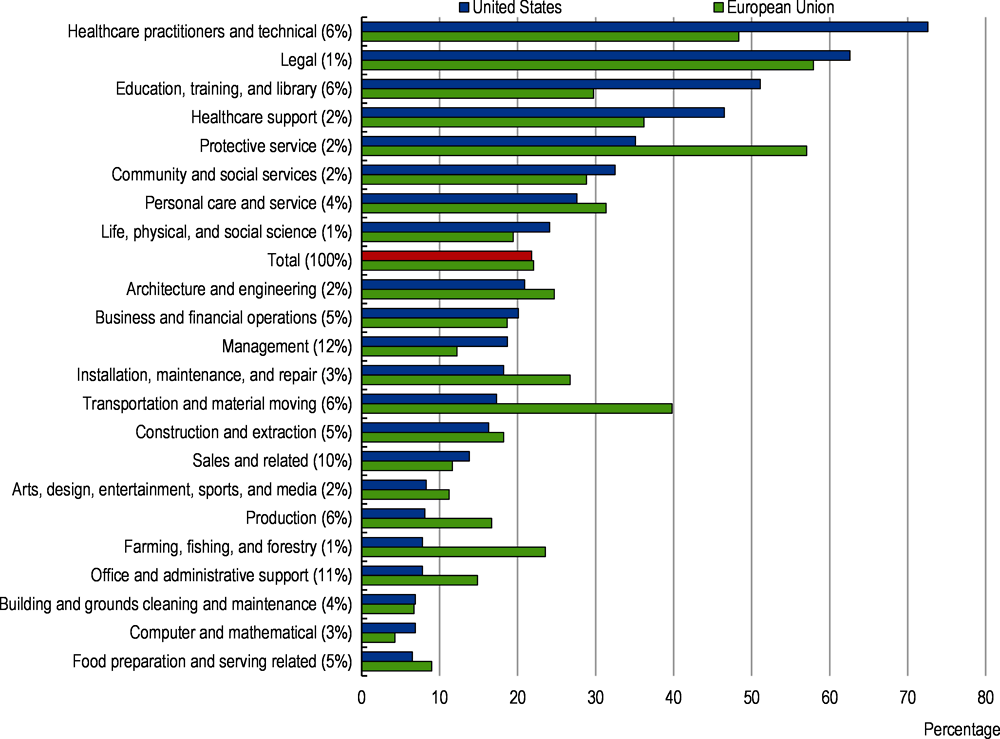

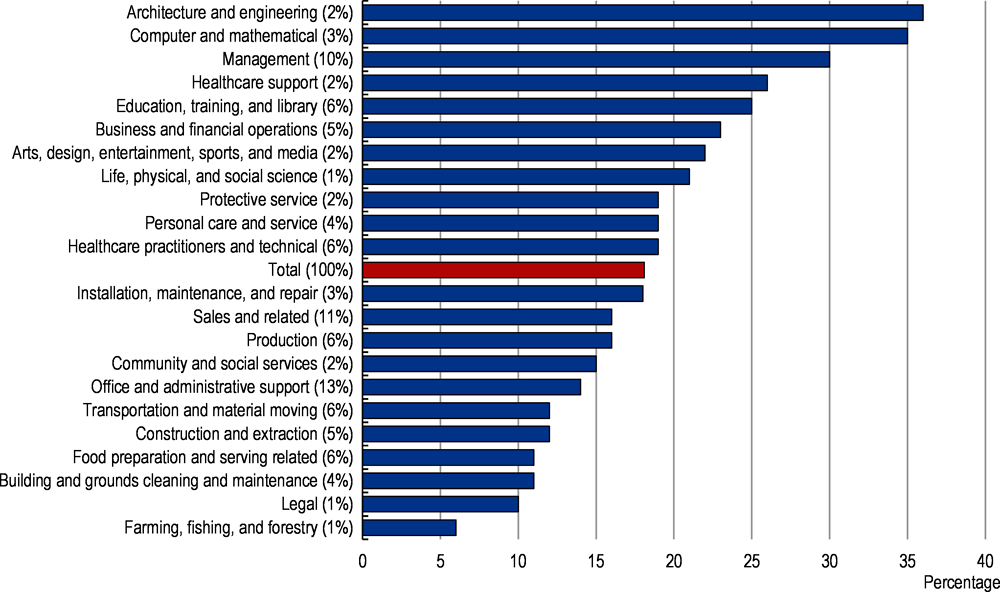

Regulating occupations plays a legitimate role in protecting consumers and as a way to ensure markets work effectively. This is particularly important in certain fields where consumers may not be able to observe the quality of the services even after receiving the service (a credence good; Dulleck and Kerchbamer, 2006). For example, in healthcare, patients may be unable to resolve whether an adverse medical outcome is the result of a challenging case, bad luck or poor medical practice; or the reverse in case of a good outcome. Such concerns are pronounced in high-stakes, one-off transactions and when practitioners can inflict serious harm on consumers. Healthcare and legal occupations are typical examples and are among the most licensed occupations in both the United States and the EU (Figure 3.4). However, licensing in healthcare, as well as in education, in the United States is substantially more widespread compared to the EU, whereas transportation and production occupations have a comparably lower share of licensed employment in the United States relative to the EU.

Figure 3.4. The United States licenses health and education occupations more than the EU

Percentage of workers with an occupational licence by occupation, 2015 (EU) and 2018 (USA)

Note: The proportion of total employment in each occupation is reported in parentheses for the United States. For comparison, occupational classification codes used in the EU (ISCO-08) have been converted to occupational codes used in the United States (SOC 2010). In cases when the ISCO-08 code links to more than one main SOC group, the group with the highest employment share is used.

Source: Current Population Survey, BLS; Calculations produced by Maria Koumenta (Queen Mary University of London) based on the EU Survey of Regulated Occupations.

Proponents of occupational licensing point to better quality of services from the professionalization, entry requirements and standards imposed by licensing an occupation. However, evidence of improved quality and higher consumer welfare is mixed. The few available studies of the initial adoption of licensing laws have found positive effects, for instance on maternal and infant mortality when midwives became licensed in the early 20th century (Anderson et al., 2016). Likewise, the quality of physicians improved as a result of licensing restrictions introduced in the late 19th century, according to another study (Law and Kim, 2005). By contrast, studies of more recent changes in licensing coverage and strictness have generally not been able to find significant effects of licensing on the quality of services (White House, 2015; Kleiner, 2017). Presumably, the most valuable licensing rules were implemented first, while the benefits of licensing additional professions today are likely to be much lower or even negative (Kleiner and Soltas, 2019). For some occupations, digitalisation may also be reducing the information advantage of having a government verified licence since consumers now increasingly rely on digital access to online reviews when making choices (Farronato et al., 2020).

The benefits of licensing for some consumers may come at costs to others who face higher prices, reduced employment opportunities and are disadvantaged by weaker aggregate productivity growth. By restricting entry to professions, occupational licensing policies can reduce competitive pressures, allowing incumbents to raise prices and wages. Entry barriers from licensing can be particularly large for foreign firms and foreign workers (e.g. from domestic training and local exam requirements) and thus effectively imposes a non-trade tariff barrier. Reduced job mobility – both within and between States – is not only a concern for productivity, but is also particularly important for groups with low labour market experience, such as young and low-skilled workers, to climb the job ladder (Haltiwanger et al., 2018).

Designing an effective regulatory system that strikes the right balance can present a challenge since efforts to promote quality and consumer welfare through overly stringent licensure requirements can produce unwarranted constraints on competition. Practices differ substantially across States, not only in which occupations are licensed (Figure 3.3, Panel B), but also in the requirements imposed to obtain and renew an occupational licence. A simple assessment of these requirements suggests that there are substantial differences across States in the strictness of occupational licensing regulation (Box 3.1). Regulatory differences can influence economic outcomes, such as employment flows discussed below.

Box 3.1. An indicator for strictness of occupational licensing regulation across States for certain low- and middle-income occupations

Requirements to obtain and renew an occupational licensure can be summarised with a composite indicator for each occupation, ranging from 0 (no licensing) to 6 (licensed with the strictest requirements observed across States). The National Council of State Legislatures (NCSL) collected detailed information on occupational licensing regulation for 31 occupations across all States in 2017, covering mostly low- and middle-income occupations such as cosmetologists, plumbers, nurses and real estate agents (NCSL, 2017). Using this information, Table 3.1 proposes a simple composite indicator with four sub-indicators for i) entry restrictions, ii) education and training requirements, iii) renewal requirements and iv) restrictions for ex-offenders. In the first step, all the listed variables are rescaled to the 0-6 interval, with 6 being the most restrictive requirement observed across States for each occupation and 0 being no regulation or a lower bound (e.g. 15 for minimum age). Second, the rescaled variables are aggregated using the weights reported in Table 3.1 for each occupation. To obtain an indicator for each State, a simple average is computed across the 31 available occupations (see Hermansen (2019) for an employment-weighted average).

Table 3.1. Structure of the composite indicator for strictness of occupational licensing regulation

Dimensions and weights applied to each occupation to compute an indicator for the strictness of regulation

|

Entry restrictions |

Education and training requirements |

Renewal requirements |

Restrictions for ex-offenders |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

25% |

25% |

25% |

25% |

||||

|

No recognition of out-of-State licensures |

25% |

Education level requirement |

25% |

Renewal years |

33% |

Blanket ban on licensure for some offenses |

25% |

|

Minimum age |

25% |

Number of exams |

25% |

Hours of continued education |

33% |

No limitations on the scope of inquiry on previous convictions |

25% |

|

“Good moral character” clause |

25% |

Training hours |

25% |

Renewal fee |

33% |

No requirements to only consider convictions related to the occupation |

25% |

|

Initial fee |

25% |

Experience hours |

25% |

|

|

Board not required to consider rehabilitation when issuing licence |

25% |

Note: The 15 variables applied are rescaled to the interval 0-6, with 0 being no licensing or no restrictions applied and 6 being the highest observed restriction across States (for each occupation). Missing values are replaced with the median across States (for a few occupations a limited number of variables was dropped due to missing information and weights adjusted accordingly).

Source: Occupational Licensing Database from the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Radiologic technologists in Virginia has the most stringent regulation among the observed occupations, scoring 5.1 by the indicator. Massage therapists in Maryland and veterinary technicians in Nevada are next with a 4.4 score. Among licensed occupations, HVAC (heating, ventilation and air conditioning) contractors in Tennessee and barbers in Maryland have the lowest score with 1.1.

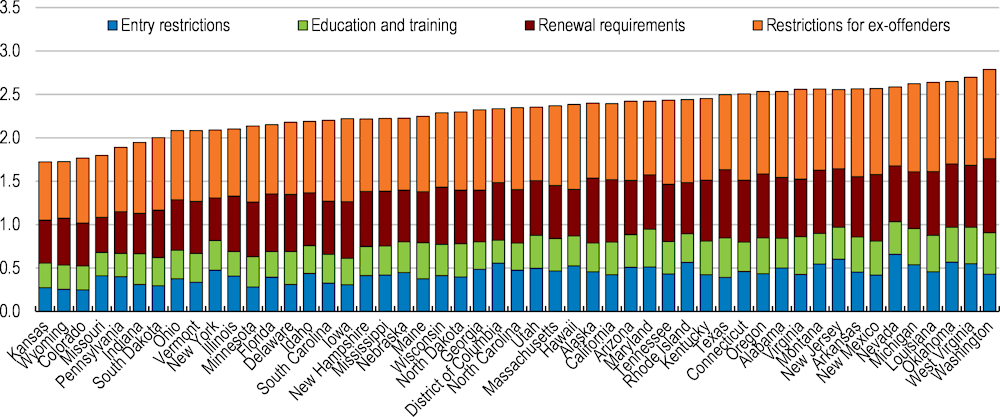

The State of Washington has the strictest regulation and Kansas the most lenient regulation according to the simple average across occupations (Figure 3.5). Restrictions for ex-offenders make the largest contribution to the indicator for most States, while entry restrictions and education and training requirements make the smallest contribution on average. The latter partly reflects the substantial variation in training and experience requirements, implying that one State with a very high requirement will put the bar for the most restrictive level (score 6) high. However, in terms of differences across States, entry restrictions display the largest variation, while restrictions for ex-offenders has the lowest variation.

Figure 3.5. Some States have more restrictive licensing regulation than others

Average occupational licensing strictness across 31 occupations (0-6 scale), 2017

Note: The 31 occupations are mostly low- and middle-income occupations licensed in at least 30 States. See Hermansen (2019) for details.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Occupational Licensing Database from the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Licensing requirements vary widely across States

A complete picture of occupational licensing requirements across States is only available for a subset of occupations. States define licensed occupations at their discretion and obey no occupational classification scheme, which complicates comparison. Tentative figures suggest that less than 50 occupations are licensed in all States and the District of Columbia (Kleiner and Xu, 2019), while more than 400 occupations are licensed in at least one State. In the absence of major differences in health, safety or quality of outcomes, it is hard to justify such regulatory differences and better data to document State differences could help to facilitate reform towards best practice.

A jobseeker assistance tool sponsored by the Department of Labor, CareerOneStop.org, contains more than 21,000 State licences. It spans from traditional doctor and lawyer licences to specialised titles such as art therapist, beekeeper, bingo operator, boxing timekeeper, concert promoter, fish packer, librarian, rental car agent, seaweed harvester, tv and radio dealer and wrestler. However, not all States provide complete and updated information to the database. The European Commission has similarly launched the Regulated Professions Database, providing information on 600 regulated professions across countries and with contact points to facilitate labour mobility. The federal government should support initiatives to systematically collect and analyse data on licensing regulation and labour market outcomes to help job seekers and inform policymakers on best practices.

A consortium of the National Council of State Legislatures (NCSL), the Council of State Governments and the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices is currently producing research and delivering technical assistance to States (NCSL, 2017; 2019a). The project was able to collect detailed information for 31 occupations, all licensed in at least 30 States, reviewed below. Still, a tremendous effort is required to document the full picture of occupational regulation across States and not least changes in regulation over time.

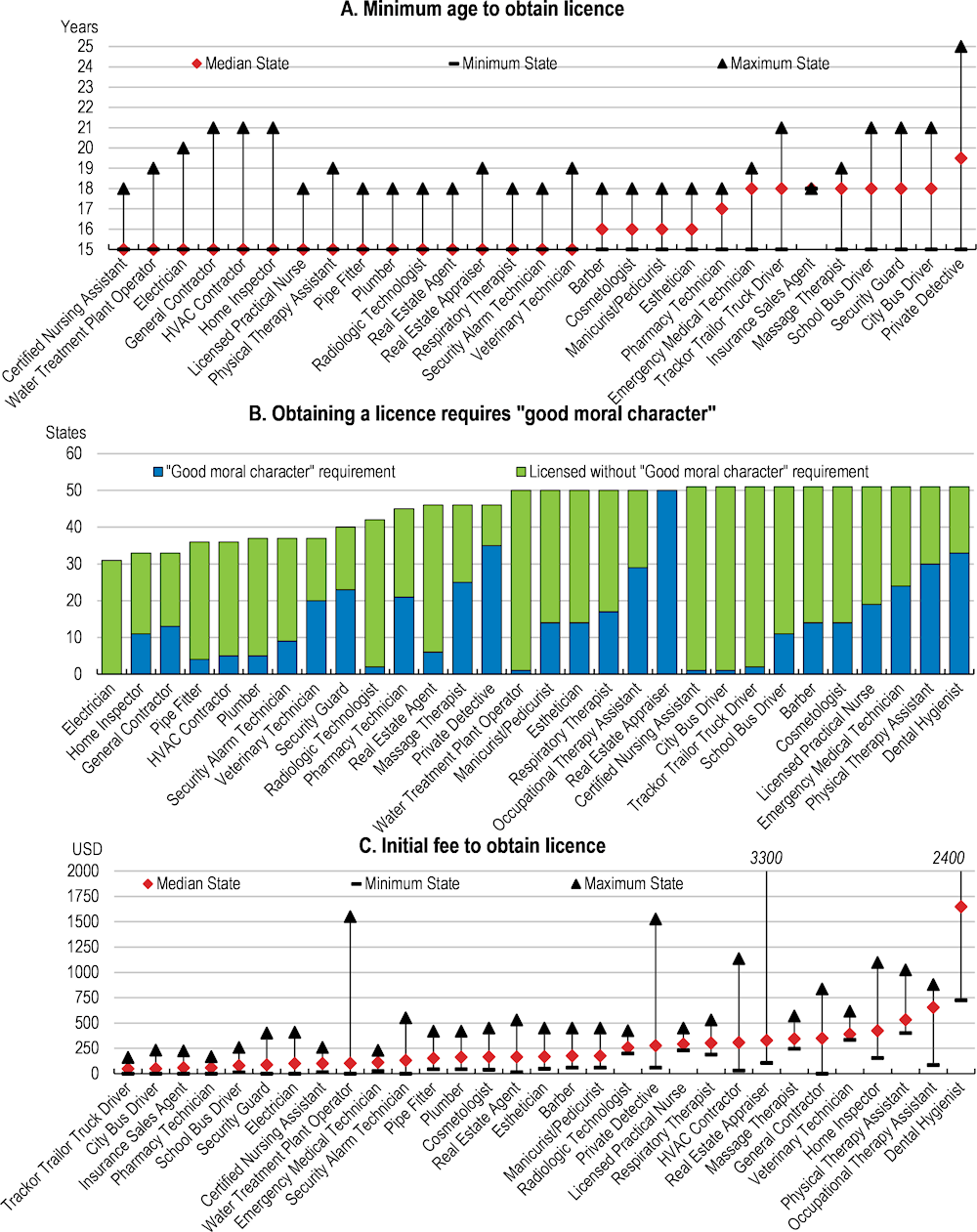

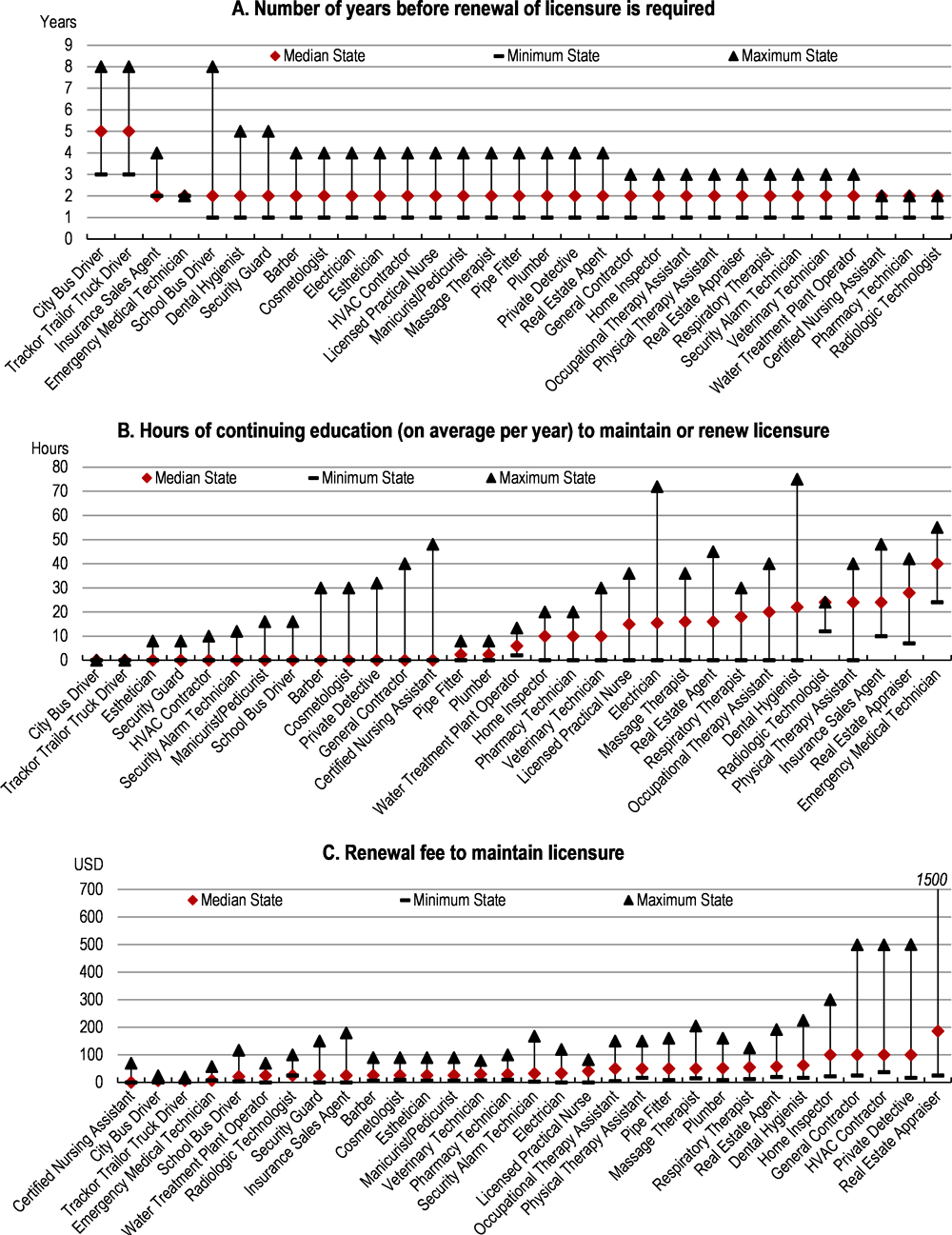

Entry restrictions to obtain an occupational licensure take many forms (Figure 3.6). Some States set a minimum age of 21 for certain occupations and even as high as 25 to become a private detective in Pennsylvania (Panel A). Often licensing regulation also requires the applicant to maintain a “good moral character” (Panel B), which has usually been interpreted as a ban on individuals with any criminal record (Craddock, 2008; Rhode, 2018). However, this clause provides licensing boards with substantial discretion to decide if the applicant is fit for a licensure. Several States, including Indiana and Kentucky, have recently passed legislation to disallow the use of vague terms like “good moral character”.

Sizeable fees to acquire a licence can also be an important entry barrier. Fees are often the main revenue source for licensing authorities to finance the administrative work, but some States also rely on fees to finance other activities (NCSL, 2019b). The median State charge around USD 250 for a licence across most of the occupations studied here (Panel C), but going as high as USD 3300 for a real estate appraiser licence in Texas or USD 2400 for a dental hygienist licence in Arizona. Other States apply much lower fees and Florida recently implemented a licensing fee waiver for low-income households and military families.

Figure 3.6. Barriers to enter occupations take many forms and vary across States

Note: The minimum age is set to 15 for States with no restriction. “Good moral character” means that the licensing authority determines the moral turpitude of the applicant, often with broad statutory discretion.

Source: Occupational Licensing Database from the National Conference of State Legislatures.

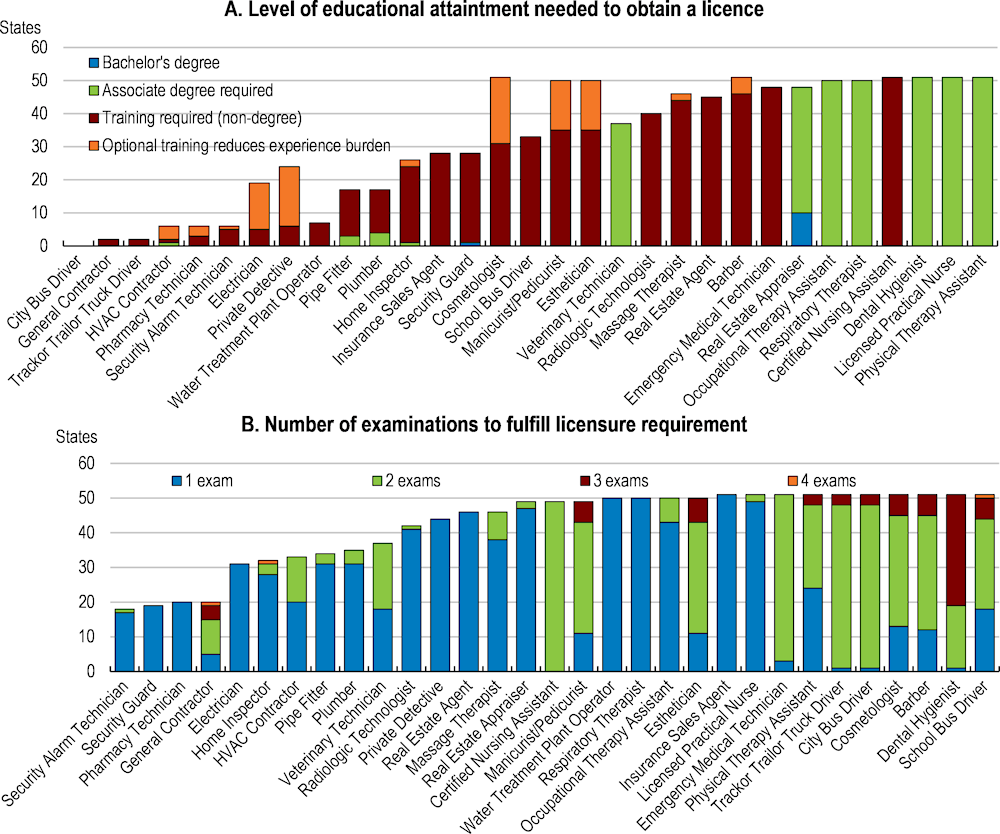

Qualifying for a licensure can require a certain level of educational attainment and passing a number of exams (Figure 3.7). Completing a number of training hours and documenting hours of experience are also required for many occupations (Figure 3.8). These requirements also vary substantially across States. For instance, a real estate appraiser licence requires a bachelor’s degree in 10 States, an associate degree in 38 States and no degree in three States. A home inspector licence requires passing four exams in Alaska, while only one exam is required in 28 States and 19 States do not license.

Figure 3.7. Educational requirements can be sizeable

Note: For some occupations, a few States with missing information are not recorded.

Source: Occupational Licensing Database from the National Conference of State Legislatures.

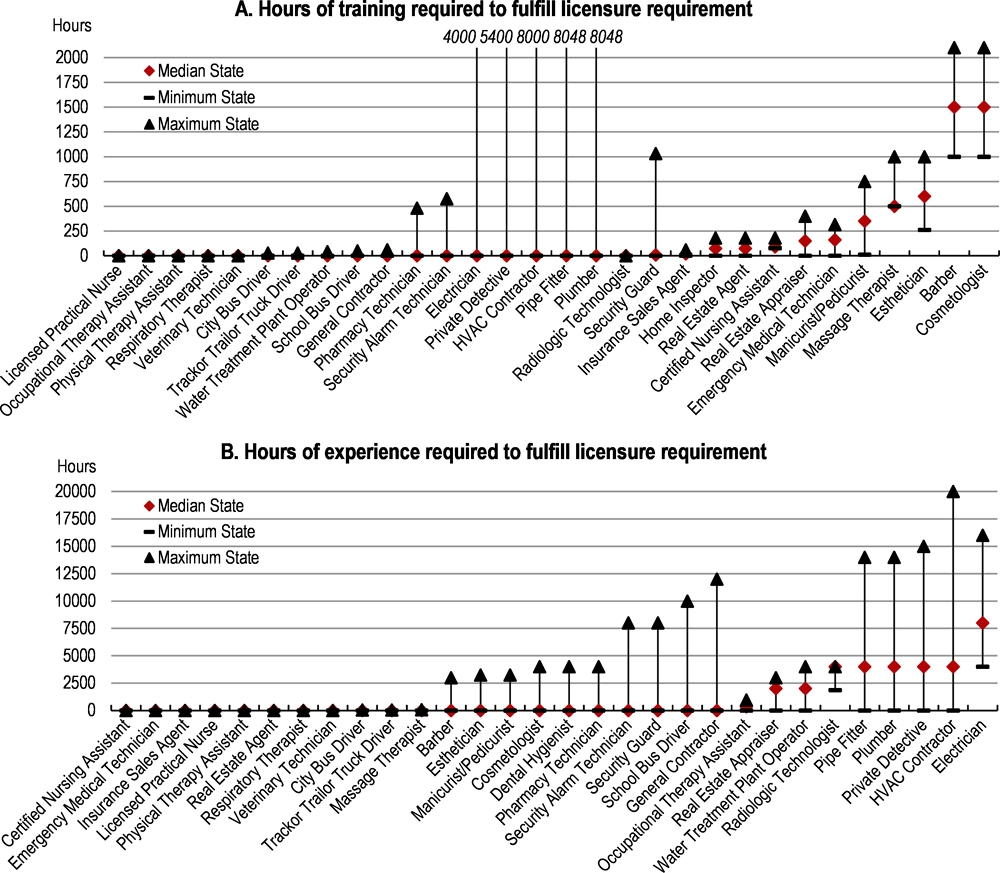

Cosmetologists and barbers have the longest training requirements across the reviewed occupations with a median of 1500 hours across States (Figure 3.8, Panel A). Yet, Massachusetts, New York and Vermont only require 1000 hours for cosmetologists, while 2100 hours is required in Iowa and 2000 hours in Idaho. The need for training is usually justified as a means to ensure public health, safety and quality. Nonetheless, training requirements are much lower for e.g. emergency medical technicians (median of 160 hours) directly tasked to save lives. Experience requirements and their variation across States can be even larger (Figure 3.8, Panel B). Electricians are only licensed in 31 States, but among those the median experience requirement is four years. Virginia requires ten years of experience to acquire an HVAC contractor licensure, while six States license without any training and experience requirements and 15 States do not license.

Figure 3.8. Training and experience requirements vary substantially across States

Note: All training and experience requirement are converted to hours (1 week = 40 hours, 1 month = 2000/12 hours; 1 year = 2000 hours). For some occupations, a few States with missing information are not recorded

Source: Occupational Licensing Database from the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Most States require renewal of the majority of occupational licences studied here every two years (Figure 3.9, Panel A). This usually involves continuing education of 10-30 hours on average per year and paying a renewal fee of USD 25-50. Again, some States only require renewal every four years and no ongoing training. For many occupations, upholding frequent renewal may not be necessary to ensure quality and could function as an effective entry barrier.

Figure 3.9. Renewal requirements to maintain a licensure can be substantial

Note: States with no renewal requirements are not included. Continuing education is converted to hours (1 week = 40 hours, 1 month = 2000/12 hours; 1 year = 2000 hours). For some occupations, a few States with missing information are not recorded.

Source: Occupational Licensing Database from the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Occupational licensing reduces job mobility

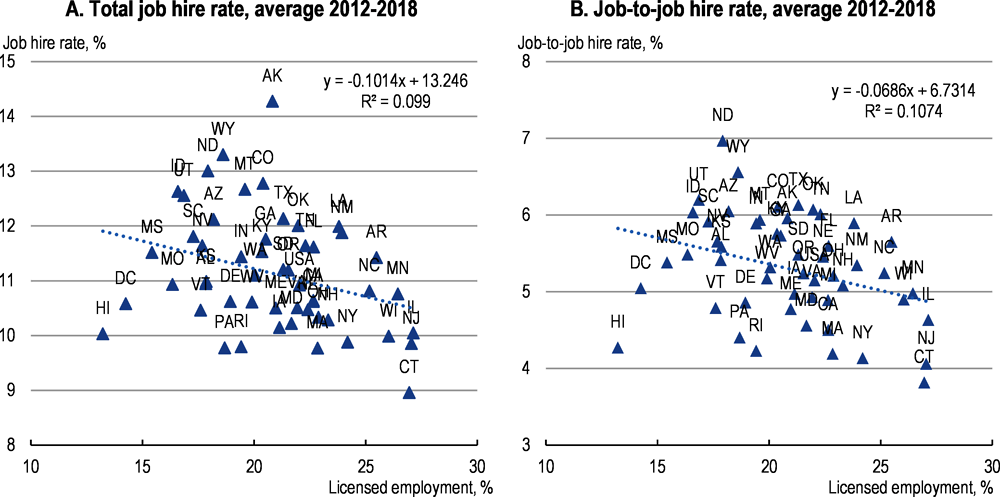

States with higher coverage of occupational licensing tend to have lower job mobility (Figure 3.10). A simple plot of the share of licensed employment against the total job hire rate, measured as the number of job hires in a quarter relative to employment, shows a negative, albeit weak association (Panel A). Job hires include both hires from non-employment and job-to-job hires (Panel B), which reflect job moves with no or only a short non-employment period. The entry barriers from occupational licensing are likely to affect both types of hiring. Lower hire from non-employment raises concern for reduced employment and labour market participation, while lower job-to-job hire is a key concern for labour reallocation and productivity growth.

Figure 3.10. Labour market fluidity tends to be lower in States with more licensed employment

Note: Licensed employment by State is computed by mapping information on licensing regulation to occupational employment statistics and aggregating across States, cf. Hermansen (2019).

Source: OECD calculations based on data from careeronestop.org and Occupational Employment Statistics, BLS; Job-to-Job Flows database, Census Bureau.

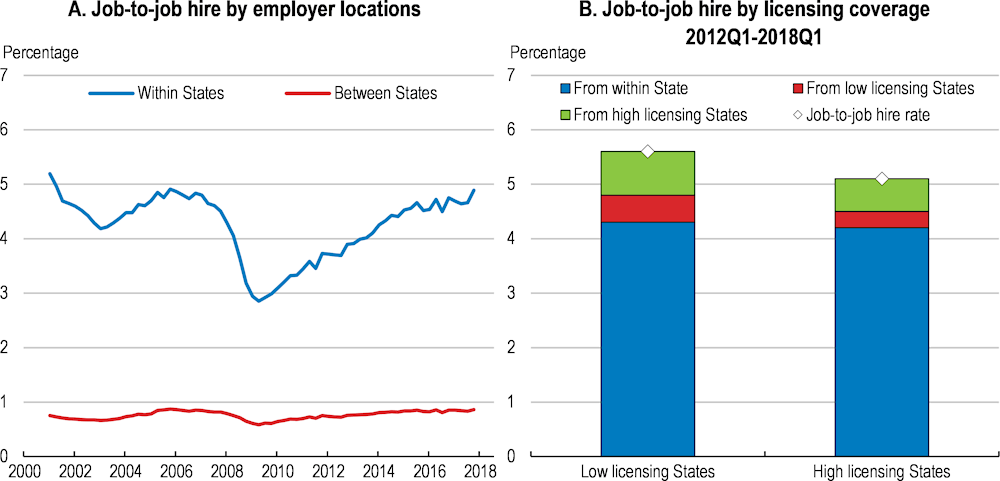

The patterns of job-to-job moves between States also appears to be linked with licensing coverage (Figure 3.11). The majority of job-to-job moves takes place between employers in the same State, whereas job-to-job moves across a State border amounts to around 1% of employment per quarter and has been fairly stable since the early-2000s (Panel A). However, a split of States in two groups with low and high licensing coverage indicates that high licensing States tend to attract considerably fewer job-to-job hires from other States compared to low licensing States (Panel B). Job-to-job mobility within high licensing States does not differ much from low licensing States, suggesting that reduced interstate mobility resulting from occupational licensing is the key driving factor.

Figure 3.11. High occupational licensing coverage depresses job-to-job hire between States

Note: Panel A is based on an unbalanced number of States over time; a balanced version using only 34 available States shows a qualitatively similar trend. Panel B shows simple averages across 25 low and high licensing States, classified according to the share of licensed employment in Figure 3.3. See Hermansen (2019) for an employment-weighted decomposition.

Source: OECD calculations based on Job-to-Job Flows database, Census Bureau; careeronestop.org and Occupational Employment Statistics, BLS.

New empirical analysis produced for this Survey has examined these correlations in detail using a novel and comprehensive Job-to-Job Flows database from the U.S. Census Bureau (Hermansen, 2019; Box 3.2). The results indeed suggest that occupational licensing reduces job mobility. This holds for hires from non-employment to employment and for job-to-job moves. Moreover, differences in occupational licensing regulation across States are found to be particularly detrimental for job-to-job hires that involves crossing a State border.

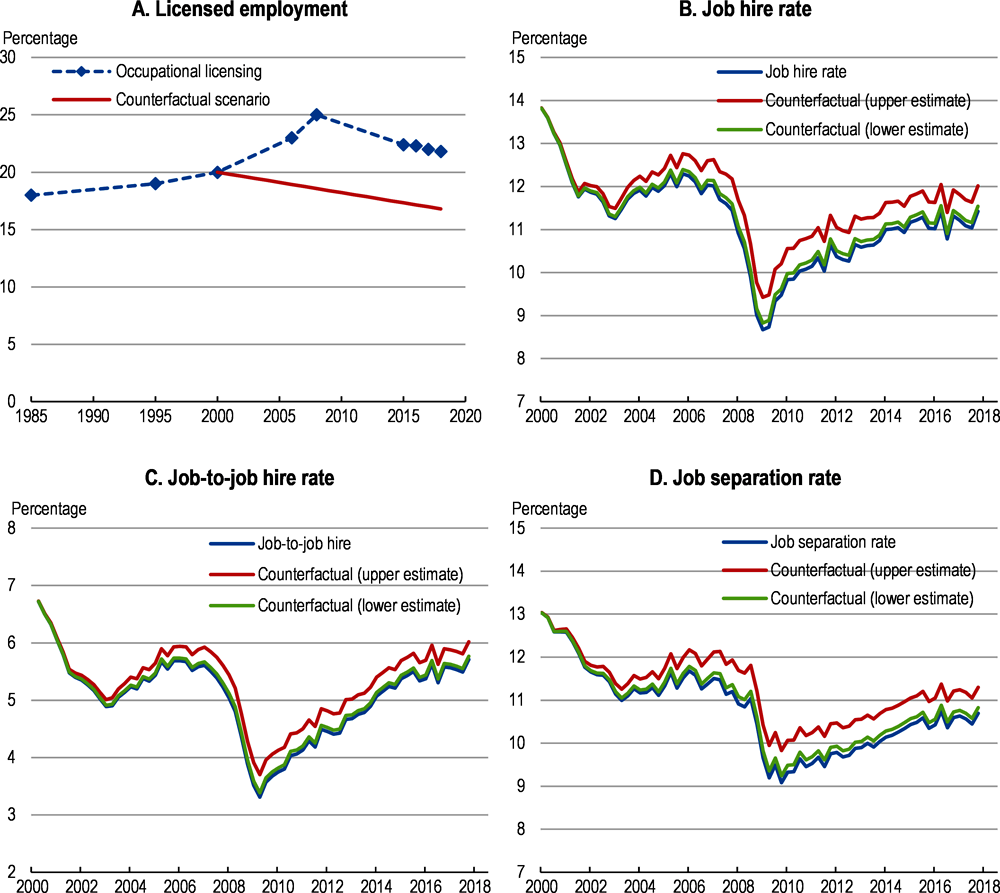

Using these results in a counterfactual reform simulation suggests that reducing the burden of licensing could boost labour market fluidity (Figure 3.12). The exercise asks what would have happened to the job hire and separation rates if overall licensing coverage had been 5 percentage points lower in 2018 compared to the observed level (21.8% of employment) with a gradual implementation during 2000-2018 (Panel A). This would be a sizeable reform, roughly corresponding to all States lowering licensing coverage to the levels in Idaho and Utah (Figure 3.3). The simulation finds that the 5 percentage points reduction in coverage could increase the job hire rate by 0.1-0.6 percentage point (1-5% increase) (Panel B); increase the job-to-job hire rate by 0.1-0.3 percentage point (1-6% increase) (Panel C); and increase the job separation rate by 0.1-0.6 percentage point (1-6% increase) (Panel D). These are all economically important effects. For instance, the counterfactual increase in the job hire rate corresponds to up to a quarter of the decline observed from 2000 to 2018 (Panel B).

Box 3.2. Empirical analysis of occupational licensing and job mobility in the United States

New empirical analysis of occupational licensing and job mobility has been prepared for this Survey (Hermansen, 2019). In contrast to the majority of existing studies, the analysis includes licensing coverage of almost all occupations and uses administrative data for the near universe of job transitions in the United States. The results are thus close to macro-level estimates of the implications of occupational licensing.

Both larger coverage and higher strictness (defined in Box 3.1) of occupational licensing are found to be associated with lower job mobility (Table 3.2, upper half). This holds for job-to-job hire and separations as well as for transitions in and out of non-employment. For job-to-job moves across States, but within the same industry, larger coverage and higher strictness compared to other States is found to reduce the inflow of job-to-job moves (see Hermansen (2019) for results and methodology).

The sub-indicators of strictness are also analysed in a joint regression to assess their relative importance for job mobility (Table 3.2, bottom half). Higher entry restrictions and renewal requirements are associated with lower job-to-job mobility, while longer education and training requirements is found to be positively associated with job-to-job mobility. This may reflect that such requirements can enhance skills, which can lead to better job opportunities. Lastly, higher licensing restrictions for ex-offenders is found to be associated with lower hiring from non-employment.

Table 3.2. Job mobility is estimated to be negatively associated with occupational licensing

Estimated association between occupational licensing indicators and job mobility measures

|

Job hire |

Job separation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Occupational licensing indicator |

Job hire rate |

Job-to-job hire rate |

Non-employment hire rate |

Job separation rate |

Job-to-job separation rate |

Non-employment separation rate |

|

Coverage of licensing regulation |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

Strictness of licensing regulation |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

Subcomponents of strictness |

||||||

|

Entry restrictions |

– |

– |

0 |

– |

– |

0 |

|

Education and training |

0 |

+ |

0 |

+ |

+ |

0 |

|

Renewal requirements |

– |

– |

0 |

– |

– |

0 |

|

Restrictions for ex-offenders |

– |

0 |

– |

– |

– |

0 |

Note: “–” refers to a negative association; “+” refers to a positive association; and “0” refers to no statistical significant association at the 5% level. The reported results are based on cross-sectional estimations across States and industries with sex/age or sex/education as controls.

Source: Hermansen (2019) based on Job-to-Job Flows data, Census Bureau; Occupational Licensing database, NCSL; careeronestop.org; Occupational Employment Statistics, BLS.

Figure 3.12. How would job mobility look like if licensing coverage had been reduced in the 2000s?

Note: Upper and lower bound estimates reflect the estimates from the cross-sectional estimation with control for sex/age or sex/education using the indicators based on the NCSL database and the careeronestop database, respectively (Hermansen, 2019).

Source: OECD calculations based on Job-to-Job Flow database from the Census Bureau.

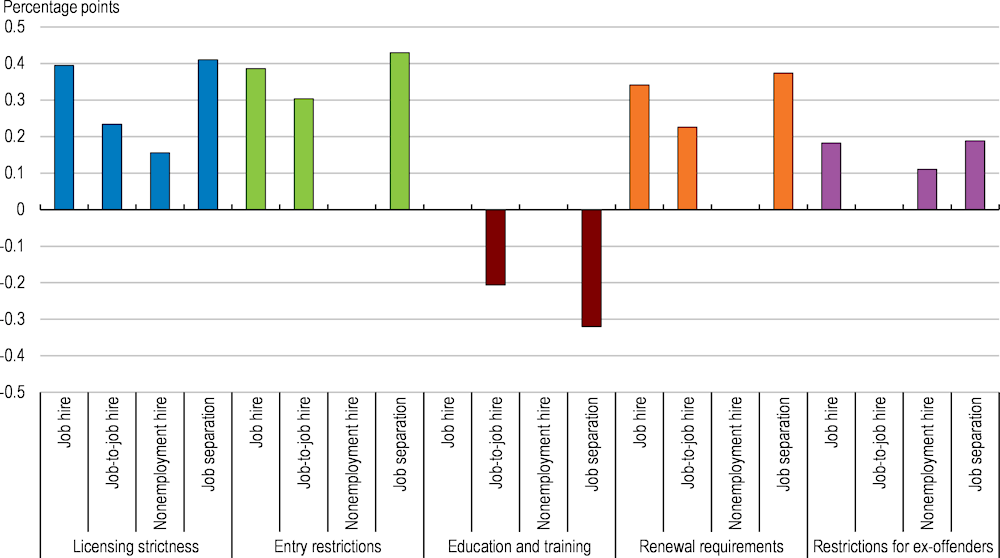

Making licensing regulation less strict among the analysed low- and middle-income occupations would also boost job mobility considerably according to the results (Figure 3.13). A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that if the State of Washington, which has the strictest regulation, deregulated to a median level as in District of Columbia, Georgia and North Dakota, the job hire rate could increase by 0.4 percentage point (3.6% increase) (blue bars). The next four blocks in the figure repeat the simulation for the sub-indicators of licensing strictness. If Nevada, the State with the highest entry restriction score, reduced its score to Virginia’s level, the job hire and job separation rates would increase by around 0.4 percentage point (around 4% increases) (green bars). Reducing education and training requirements from the highest level in Washington to Minnesota’s level, could have reverse effects and reduce the job-to-job hire rate by 0.2 percentage point and the separation rate by 0.3 percentage point (both more than 3% declines) (brown bars). Loosening renewal requirements in Washington to Utah’s level would also have an economically important impact on the job hire and job separation rates (orange bars). Lastly, easing restrictions for ex-offenders in Virginia to California’s level could have a minor, but still economically important effect of 0.1 percentage point on the non-employment hire rate (2.2% increase) (purple bars).

Figure 3.13. What could reduced strictness of occupational licensing do to job mobility?

Simulated effect of the most regulated State in each dimension moving to the median State regulation level

Note: The five policy experiments are based on the constructed strictness indicator (Box 3.1) and its subcomponents (Hermansen, 2019). Licensing strictness reflects Washington reducing the indicator from 2.8 to the median level of 2.3 in District of Columbia. Entry barriers reflects Nevada reducing the sub-indicator from 2.6 to the median level of 1.7 in Virginia. Education and training reflects Washington reducing the sub-indicator from 1.9 to the median level of 1.4 in Minnesota. Renewal requirements reflects Washington reducing the sub-indicator from 3.4 to the median level of 2.5 in Utah. Restrictions for ex-offenders reflects Virginia reducing the sub-indicator from 4.1 to the median level of 3.5 in California. The calculations apply estimates from the cross-sectional estimations with control for sex/age or sex/education. Insignificant estimates at the 5% level are set to zero. For simplicity, the share of licensed employment is set to the national level at 21.8% in all calculations.

Source: Hermansen (2019).

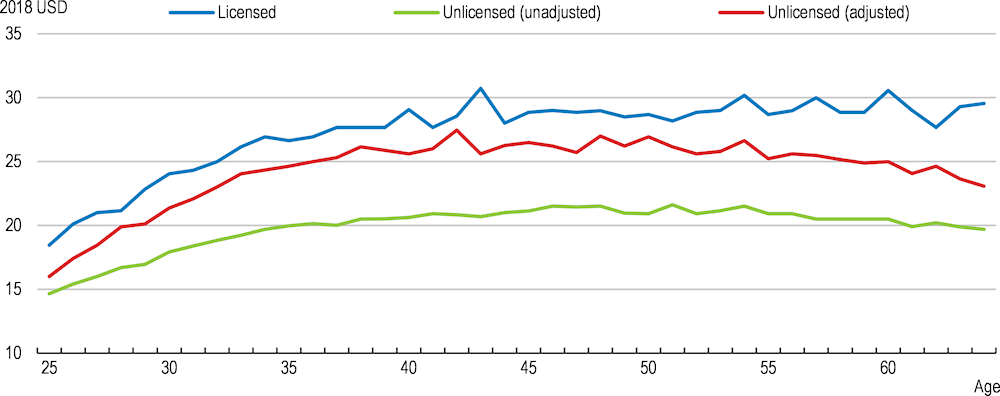

Not only does occupational licensing affect job flows but also earnings. In fact, most of the literature on occupational licensing have focused on wage effects, generally finding a premium of 5-10% (Kleiner and Krueger, 2013; Gittleman et al., 2018; Blair and Chung, 2018), with a notable exception by Redbird (2017). Calculations across workers of different ages suggest that this premium exist at all ages and tends to increase throughout workers’ careers (Figure 3.14). A licensing earnings premium is likely to arise from two effects. First, the entry barrier and requirements on job takers reduce employment in licensed occupations and hence competition, driving up prices of goods and services for consumers. Licensed employees benefit from this through higher earnings, unless the profit flows to e.g. licensing authorities through fees. Second, workers excluded from licensed occupations experience reduced earnings as they may be forced to work in less well-paid occupations or remain unemployed and since supply of workers in unlicensed occupations increases and drives down wages.

Figure 3.14. Licensing wage differences tend to increase throughout workers’ careers

Median wage for licensed and unlicensed workers by age, 2016-2018

Note: Estimates for the "unlicensed (adjusted)" series are derived from a DiNardo, Fortin, and Lemieux reweighting with controls consisting of gender, race, quadratic expressions of both age and years of education, union coverage, self-employment status, region, and public sector status. Sample weights are used throughout. The sample consists of 25-64 years old employed workers with wages between USD 5 and USD 100 per hour, excluding observations with Census-allocated wage and earnings. Earnings are deflated using the CPI-U-RS.

Source: Nunn (2018) based on the Current Population Survey.

A licensing earnings premium need not imply stronger earnings growth over time. In the short term when an occupation becomes licensed, earnings may rise fast as employees benefit from the new entry barrier that can drive up prices and wages. In the longer term, reduced competition and weaker labour mobility will tend to reduce productivity growth (von Rueden et al., 2020), reducing the scope for earnings growth relative to unlicensed occupations and States with more lenient regulation. The background work produced for this Survey also analysed earnings and found some evidence of reduced earnings gain from job-to-job moves towards States with larger coverage or higher strictness of licensing regulation in the same industry (Hermansen, 2019). This could reflect spatial differences in productivity growth because of licensing. Nevertheless, more comprehensive data of licensing and outcomes are needed to draw firmer conclusions on the link between occupational licensing and earnings growth.

Deregulating and harmonising requirements to improve mobility

Occupational licensing reform could boost job mobility and productivity growth by critically reviewing the numerous licences with less than universal coverage. If not all States license an occupation, a stronger empirical case and arguments beyond general concerns for public health and safety should justify licensing in the States that choose to do so. Delicensing or using alternative systems such as voluntary certification (Box 3.3) are then available to regulate in a more growth-friendly manner.

Evaluations of licensures should rely on careful and comprehensive cost-benefit analysis. Notably the degree to which particular licensure requirements are mitigating a quality information or health and safety problem in the marketplace and the degree to which licensure is reducing supply of qualified professionals. Only 12 States have legislation that requires cost-benefit analysis of new licensing proposals (“sunrise” review), while 28 States maintain some sort of “sunset” process to licensing laws in place for some time (Council of Licensure, Enforcement & Regulation). However, the administration of reviews and the dimensions included vary much across States. Colorado has established a unifying and nonpartisan Department of Regulatory Agencies (DORA) responsible for conducting reviews, which many observers view as a best practice approach (e.g. Kleiner, 2015). Moreover, specifying whose benefits and costs should be counted (standing) is a crucial step in licensing cost-benefit analysis. Not only should implications for competition, employment and productivity ideally be quantified, but a strictly State-level perspective may also leave out vital implications at the national level (Dobes, 2019). Using a standardised approach across States could help to address such concerns. In Australia, a Competition Principles Agreement between the federal government, states and territories essentially subjects all legislation to cost-benefit and necessity analyses, including occupational licensing.

Box 3.3. Alternative forms of occupational regulation

There are many approaches to regulate services and balance trade-offs between not restricting competition and ensuring quality and protection of consumer health and safety. Moreover, occupations that do not have their own discrete regulatory regime are not necessarily unregulated, as they can still be regulated by the general law.

Direct regulation of firms and licensed supervisors

For some occupations, monitoring and inspecting firms directly can be more effective and less burdensome to ensure safety and quality for consumers than licensing. Licensing boards assess entry requirements, but may not have the capacity to monitor and discipline licensed practitioners. A related approach is to only require licensing of a supervisor and allow employees without proven qualifications to perform duties, although this has the disadvantage of imposing a certain business structure. In some States, such as Arizona and Georgia, (journeyman) electricians do not need an occupational licence as long as they work for a licensed electrical contractor. In many European countries, licensing of “masters” only are common for plumbers, electricians and similar professions (von Rueden et al., 2020).

Certification

A certified profession is a restriction on the use of title. Anyone can perform the services of the profession, but only those who have been certified are allowed to use the title. This approach is thus less restrictive than licensing, but offers a means to inform consumers on quality of providers. Voluntary certification can be administered by a government agency or a professional association, managing minimum requirements and examinations. Typical examples are car mechanics and travel agents. In practice, certification also brings together active market participants and when widely adopted, the seal of approval can become a de facto entry barrier for meaningful market participation.

Registration

Maintaining registration for a profession simply implies keeping a list of practitioners. This allows consumers to access information on supply and easily reach providers in the event of a complaint. Registration can be combined with minimum standards, such as providing documentation for qualification. However, if quality is hard to observe, registration may not help consumers feel confident in acquiring certain services.

Licensing or not licensing is just one aspect of evaluations. Reviewing and harmonising the large variation in licensing requirements across States is an equally important area for reform, which could produce sizeable efficiency gains and ease job mobility across States. This is likely to require federal initiatives and support to overcome resistance and coordination challenges at the State level, which is discussed below. However, inconsistencies are also present within States. Occupations where quality is not difficult for consumers to observe are frequently more regulated than occupations where quality is hard to observe and where consumers face genuine risks to their welfare.

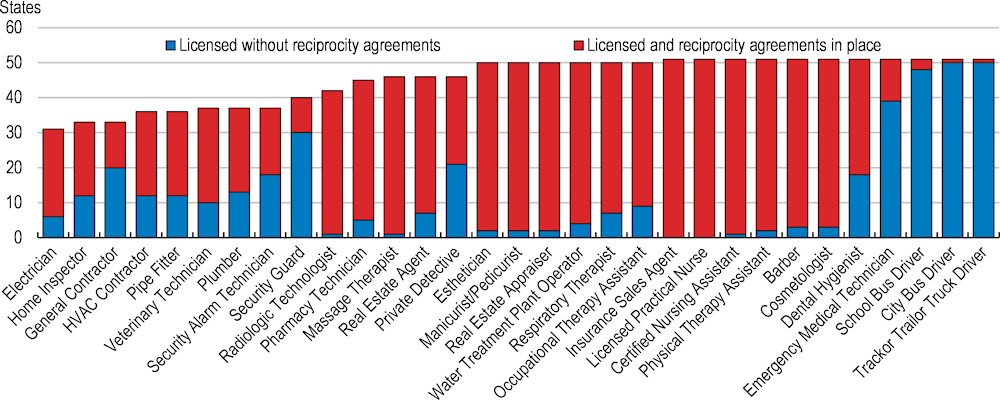

A licensure obtained in one State is not automatically recognised in other States, effectively imposing internal non-tariff trade barriers. This can be an important obstacle for mobility across States if workers have to repeat the process of applying for a licensure and redo education and training (Johnson and Kleiner, 2017). To facilitate portability of licensures, States have made reciprocity agreements, covering more than half of the State licensures studied here (Figure 3.15). Nonetheless, even among occupations licensed in all States, such as dental hygienists and bus drivers, reciprocity agreements are not in place in all States, suggesting still much scope for reform.

Figure 3.15. Occupations licensed in most States do not always have reciprocity agreements

Number of States with occupational licensing among 31 selected occupations, 2017

Note: States with reciprocity agreements have statutory language allowing reciprocity or endorsement agreements to recognise licenses or credentials obtained in other States.

Source: Occupational Licensing Database from the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Reciprocity can be made easier through interstate compacts, a formal binding contract between two or more States, or by the use of model laws and model rules to harmonise regulation and facilitate good practice across States (FTC, 2018; CSG, 2019). So far, mainly health professions have adopted interstate compacts (nurses, physicians, physical therapists, emergency medical technicians and psychologists). The Nurse Licensure Compact was the first (implemented in 1999, currently adopted by 34 States) and has been shown to increase job movements of nurses from one compact State to another (Abdul Ghani, 2018). It relies on a mutual recognition/multistate licence model, which allows nurses licensed by one compact State to practice in other member States without giving notice or obtaining another licence. By contrast, the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (adopted by 31 States) requires physicians to be licensed in each State of practice, but expedites licensure. Most of the other health profession compacts rely on a mutual recognition model similar to that of the Nurse Licensure Compact, but were activated in recent years and have been adopted by fewer States. While effective, interstate compacts are mainly relevant for large occupations licensed in almost all States since they require time and resources to form. States must adopt the proposed legislation and all compact States must agree to any modifications. Model laws are more flexible than compacts, and licence portability provisions in some model laws, such as the Uniform Accountancy Act, have been adopted by all U.S. jurisdictions. It relies on a mutual recognition model that allows accountants to practice across State borders without notice (FTC, 2018).

Conversely, nothing prevents a State from recognising licences obtained in other States, which corresponds to a unilateral removal of a trade barrier. Recently Arizona became the first State to automatically grant occupational licences to anyone who moves there with a licence from another State (House Bill 2596). This extends a widespread practice for military spouses that typically must move multiple times during their careers (NCSL, 2019b). The automatic recognition does not eliminate all reciprocity barriers though, since it only applies to residents and does not allow commuters to work with an out-of-State licence. Moreover, no other States have indicated they would follow the radical and welcoming move of Arizona, which leaves cumbersome State-by-State reciprocity agreements or nationwide initiatives based on model laws or instate compacts as the main tools to ease cross-border job mobility.

Other federal OECD countries have addressed the mobility challenge in different ways (Box 3.4). Canada has implemented an internal free trade agreement to facilitate recognition of licences across provinces, Australia attempted to form a national licensing system, but reversed to rely on mutual recognition agreements, while Germany has a mix of regulation at both the federal and Länder level.

Box 3.4. Regulation of occupations in other federal countries

Canada

In 2014, approximately 11% of Canadian workers could be identified as licensed (Zhang, 2019). Occupational regulation is highly decentralised, mainly at the provincial level. 106 occupations are licensed in at least one province, varying from 47 in Newfoundland and Labrador to 98 in Quebec. Although there is no specific centralised regulatory body, several occupations (e.g. aviation inspectors, pilots and immigration consultants) are regulated at the federal level.

An internal free trade agreement between the federal government and provinces and territories (signed in 1995 and updated in 2009) encourages labour mobility while respecting local governments’ right to regulate. Workers can generally move freely with their existing licence or certification without having to do significant additional training, work experience or examination. In a few cases of very different standards, exceptions are made, but requires a legitimate objective such as protecting public safety or the environment. Four provinces have gone further and established full mutual recognition of all regulated occupations (New West Partnership).

Australia

In 2011, around 18% of workers in Australia worked in an occupation subject to regulation (Productivity Commission, 2015). States and territories regulate occupations, covering as much as 180 occupations in total. In 2008, an attempt was made to establish a national occupational licensing system to allow licensed workers to work throughout Australia. However, in 2013, the majority of states and territories rejected the reform because of concerns with the proposed model and potential costs. Decentralised reforms to enhance flexibility and mobility of workers are being pursued based on a mutual recognition act from 1992. This was further extended to include both Australia and New Zealand through the Trans-Tasman Mutual Recognition Act from 1997. Mobility through mutual recognition allows workers to apply for a licence for the same occupation in a second state or territory, which will be granted if the authority assess the two to be equivalent. However, the approach has drawbacks since it requires each state and territory to put in place their own legislation to support mutual recognition (as for reciprocity agreements). Indeed a recent committee report to the Australian senate characterised the system as complex, duplicative and burdensome (Select Committee on Red Tape, 2018).

Germany

With 33% licensed workers, Germany has the highest licensing coverage across countries with available data (Figure 3.3). There are 150 regulated professions; some are regulated at the federal level (e.g. doctors, nurses and physiotherapists) and others at the Länder level (e.g. architects, engineers and teachers). Sector-specific business chambers in the professional services and crafts are largely self-regulating (OECD, 2016).

A federal reform in 2004 replaced occupational licensing requirements with a certification regime in 53 out of 94 crafts professions. This resulted in an increase in entrepreneurship, measured as higher entry into self-employment and mainly among untrained workers (Rostam-Afschar, 2014). Nevertheless, parts of the reform were recently reversed, relicensing 20 crafts from 2020.

Making substantial progress on mutual licensing recognition across States will likely require intervention by the federal government. States should retain the main responsibility of occupational licensing to ensure alignment with the broader set of State labour market policies. However, federal law could require States to recognise licences obtained in other States by default, allowing States to set stricter standards only if they can prove this is needed to protect public safety. This would allow States to maintain their current regulation standards, but shift the burden from workers to meet licensure standards onto States to justify higher requirements. Such legislation is justified by the apparent cross-border aspect of practising on the market and the growing evidence of licensing restraining competition, raising prices and not improving quality (Kleiner, 2017). Nevertheless, such a proposal would be drastic and require pre-empting State law, which usually requires a clear cross-border aspect to justify federal intervention. At least one attempt has been made along these lines (Scheffler, 2019). The 1993 Clinton health care plan included a provision stating: “No State may, through licensure or otherwise, restrict the practice of any class of health professionals beyond what is justified by the skills and training of such professionals” (Health Security Act, 1994). Alternatively, the federal government could act as a broker between States to reach broader reciprocity agreements for sectors or major occupations. Ultimately, this could lead to an internal free trade agreement covering all occupations as in Canada (Box 3.4).

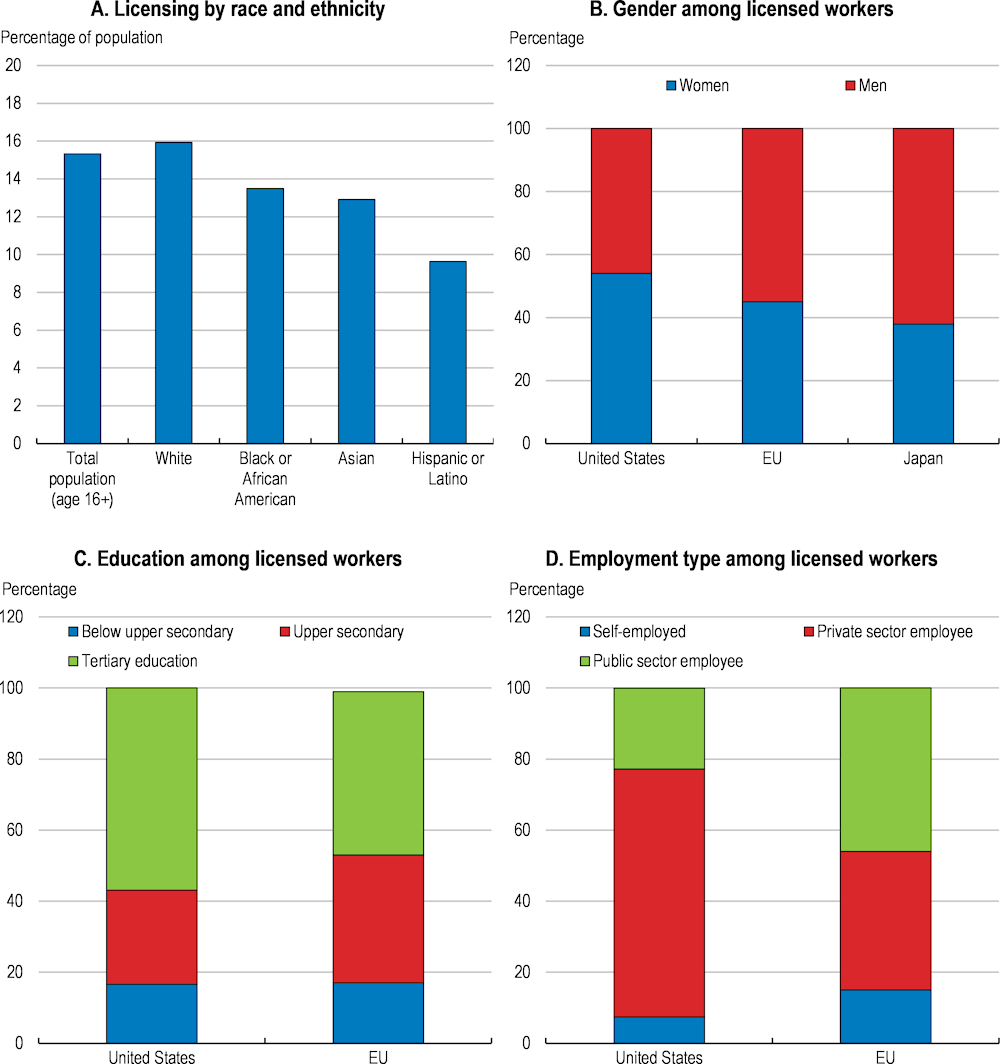

Addressing licensing restrictions affecting specific populations

Entry barriers from occupational licensing sometimes affect specific population groups, which can give rise to inequalities. Holding a licensure is more frequent among whites than other race and ethnic groups (Figure 3.16, Panel A). In contrast to the EU, licensed workers in the United States are dominated by women and higher educated (Panels B and C). This reflects the larger licensing coverage in female-dominated occupations such as health and education (Figure 3.4). The large majority of licensed workers are private sector employees, while licensed workers in the EU are much more likely to work in the public sector or to be self-employed (Panel D). By and large, this reflects structural differences in the size of the public sector and prevalence of self-employment. Nevertheless, the concentration of licensing among whites with higher education in the private sector may add to income inequality because of the earnings premium associated with licensing.

Figure 3.16. White, women, well-educated and wage workers are comparatively more licensed

Note: Hispanic or Latino ethnicity is also included in the categories by race.

Source: Current Population Survey, BLS; Koumenta and Pagliero (2017) based on the EU Survey of Regulated Occupations; Morikawa (2018).

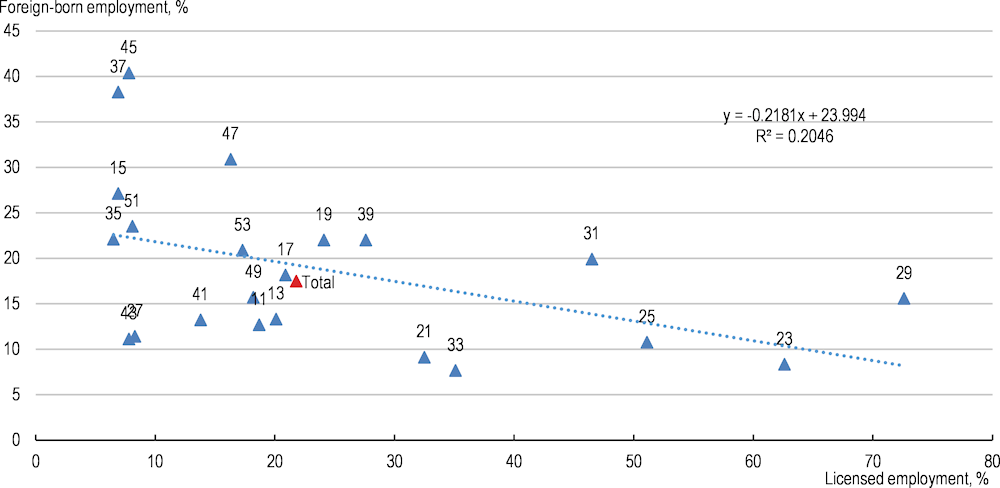

Improving access to licensed occupations for disadvantaged groups would not only increase their employment and income prospects; reducing protective measures would also strengthen competition from abroad. The share of foreign-born workers is lower in occupations with high licensing coverage (Figure 3.17), supporting the view that licensing work as a non-tariff trade barrier on service provision. States usually require domestic work experience and apply local exam and language requirements for obtaining a licensure. Evidence from the EU finds that the proportion of foreign-born workers is about one-third lower among licensed workers compared to unregulated workers after accounting for differences in worker characteristics (Koumenta and Pagliero, 2017). Noteworthy, this difference disappears for licensed occupations with automatic recognition of qualifications obtained abroad and for certified workers. This suggests that policies to reduce mobility costs in the European Union have been effective in promoting labour mobility (Box 3.5). Extending interstate compacts and reciprocity agreements in the United States to also include qualifications obtained abroad should be a next step for reform.

Figure 3.17. Occupations with higher licensing coverage tend to have fewer foreign-born workers

Foreign-born and licensed employment by occupation (age 16+), 2018

Note: Labels refer to occupational codes: 11 Management; 13 Business and financial operations; 15 Computer and mathematical; 17 Architecture and engineering; 19 Life, physical, and social science; 21 Community and social service; 23 Legal; 25 Education, training and library; 27 Arts, design, entertainment, sports, and media; 29 Healthcare practitioners and technical; 31 Healthcare support; 33 Protective service; 35 Food preparation and serving related; 37 Building and grounds cleaning and maintenance; 39 Personal care and service; 41 Sales and related; 43 Office and administrative support; 45 Farming, fishing, and forestry; 47 Construction and extraction; 49 Installation, maintenance, and repair; 51 Production; 53 Transportation and material moving

Source: Current Population Survey, BLS.

Box 3.5. Efforts to increase labour mobility for regulated professions in the European Union

As part of the effort to establish a single market for services, the European Commission issued the Professional Qualifications Directive in 2005 (amended in 2013). The Directive sets clearly defined principles and processes for professional qualification recognition across EU Member States with the aim to reduce mobility costs. To have a comprehensive overview the Regulated Professions Database was established, with information on the 600 regulated professions across countries and national contact points. EU countries were also invited to conduct a mutual evaluation of the respective barriers they have in place limiting access to certain professions.

In 2017, a Services Package was launched to further enhance mobility and help Member States to reform regulated professions. In order to introduce new regulations, countries are now mandated to pass a proportionality test to avoid excessive regulation. Moreover, analysis and country-specific reform recommendations were issued for seven groups of professions.

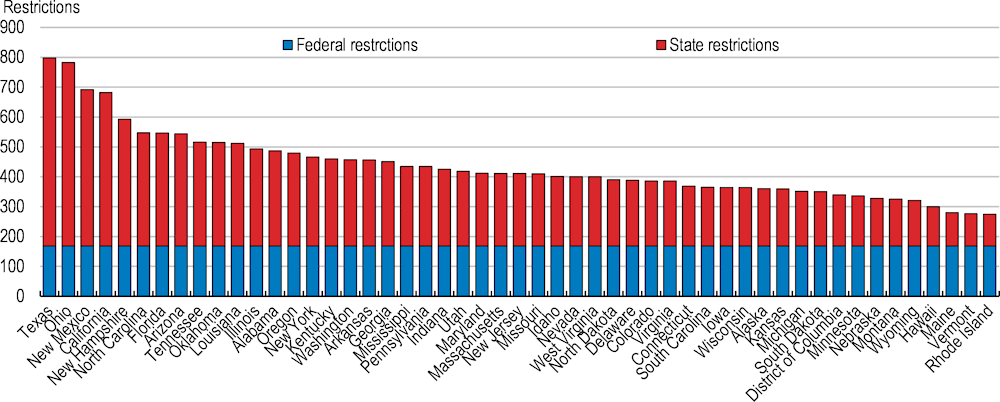

Americans with a criminal record are often the ones facing the hardest barriers from occupational licensing. Background checks can result in automatic disqualification if the applicant has committed serious crime (felony convictions). Yet, less serious offenses (misdemeanours) and arrests that did not lead to a conviction can also result in denial of a licensure (NCSL, 2019c). Some restrictions serve legitimate public safety functions, such as prohibiting people convicted of assaults or abuse from working with children or excluding people convicted of fraud from law and accounting occupations. The key objective is to make sure the conviction is relevant for the occupation sought, so as not to make re-entry more difficult than necessary. However, Texas and Ohio imposes more than 600 specific restrictions related to criminal convictions in the regulation of occupations, much higher than in Vermont and Rhode Island with just around 100 specific restrictions (Figure 3.18).

Figure 3.18. Some States impose many regulatory restrictions for individuals with criminal records

Number of legal restrictions that limit or prohibit people convicted of crimes from occupational licensure, 2019

Note: Restrictions refer to collateral consequences that are legal and regulatory restrictions that limit or prohibit people convicted of crimes from occupational and professional licensing and certification.

Source: National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction, Council of State Governments.

Such restrictions can exclude a large group of people from many jobs and generate mismatch problems. Estimates suggest that 3% of the adult population has ever been in prison and 8% has a felony conviction (Shannon et al., 2017). Among African-Americans, the corresponding numbers are as high as 15% and 33%. Background checks thus effectively constrain their employment opportunities substantially. This is emphasised by evidence showing that African-American men who do manage to get a licensure enjoy the largest positive wage benefits across race and gender groups, reflecting that a licence can work as a signal of no-criminal history (Blair and Chung, 2018).

States can set standards for licensing boards’ background checks as a way to reduce barriers for individuals with a criminal record. In many States, licensing boards are allowed to ask and consider arrests that never led to a conviction when making their decision. Licensing boards may also deny granting a licence, regardless of whether the conviction is relevant to the occupation sought or how recent it was. A reform in Indiana now requires licensing boards to explicitly list all disqualifying crimes and to exclude any arrest records not resulting in convictions from their consideration (House Bill 1245). Certificates of rehabilitation is another means to improve employment options for ex-offenders, but only used by few occupations and States (NCSL, 2019c).

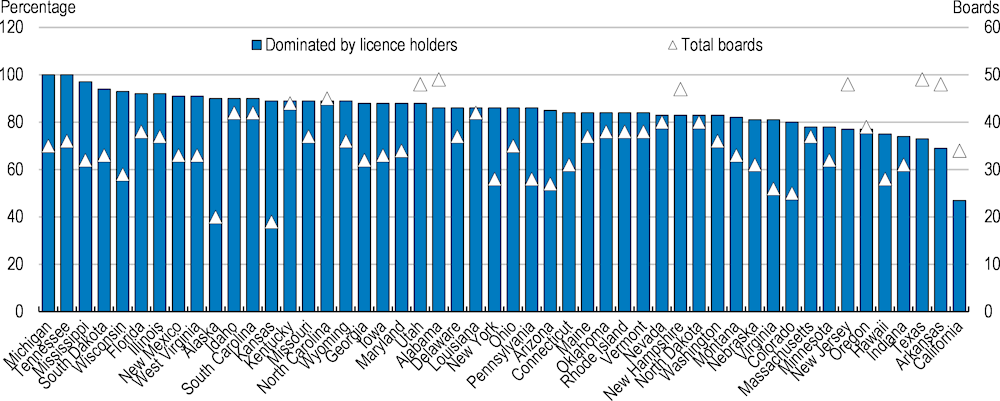

Ensuring the proper functioning of licensing boards

For most occupations, States have delegated the task to set and enforce licensing restrictions to an occupational licensing board. The vast majority of boards have direct rulemaking authority, while all boards typically serve as an influential advisory unit to other State regulators. This institutional framework can lead to conflicts of interest since 85% of the total 1790 boards in the United States are required by statute to have a majority of licensed professionals, active in the profession the board regulates (Allensworth, 2017). The average State has 36 boards and except for California, active licensure holders dominate more than 70% of boards in all States (Figure 3.19).

Figure 3.19. Licensing boards are strongly dominated by active licensure holders

Percentage of boards with a majority of active licensure holders as members, 2017

Note: Some boards issue more than on kind of licence, in which case the board is coded as dominated if all the various licensure holders forms a simple majority. Excluding these mixed dominated boards, reduces the national share of dominated boards to 69%.

Source: Allensworth (2017).

Professional board members have expertise in the training, practice and business of their fields and originally they almost exclusively populated the licensing boards. However, as market participants they are also more likely to implement burdensome entry requirements to protect themselves from competition. Evidence is scarce, but among lawyers, one study found that a larger number of persons attempting to acquire a licence was associated with more difficult exams, suggesting that boards respond to increased supply by raising entry barriers (Pagliero, 2013). Reviews have also found that public seats on boards do not always have full voting rights and are often left vacant for considerable time, both of which increase the control of professionals (Allensworth, 2017; McLaughlin et al., 2017). Moreover, it is common that statutes dedicate public seats to consumer members and reserve seats to represent the elderly, groups that are unlikely to possess sufficient expertise to voice competition concerns. Appointing members from State competition authorities, experts in economics or advocates of consumer rights would help to balance the interests of the public on licensing boards.

A 2015 Supreme Court case (Box 3.6) put the spotlight on potential anti-competitive behaviour of licensing boards and forced some States to take action. The ruling clarified that licensing boards are not automatically exempted from federal antitrust scrutiny, although it is still unclear how much the decision in practice will increase boards’ exposure to antitrust actions and constrain regulation. States have several options to comply with the ruling. In California, all non-health licensing boards have had a majority of public members for many years, albeit there is little empirical evidence on the effectiveness of this approach. Alabama, Delaware, Louisiana and Mississippi reacted to the Supreme Court case by establishing committees or commissions tasked with actively supervising the licensing boards controlled by active market participants. Other States assigned the task to existing State agencies such as the Department of Consumer Protection in Connecticut. A third alternative would be to remove specific regulation that violates competition policy and leave boards subject to antitrust scrutiny; a solution that would substantially limit the power of licensing boards to set entry restrictions (Pagliero, 2019).

Box 3.6. The North Carolina Board of Dental Examiners v. Federal Trade Commission case

The 2015 Supreme Court case was about immunity of occupational licensing boards from antitrust law. It originated from non-dentists offering tooth whitening services and sale of teeth whitening kits in North Carolina. The Board of Dentists claimed that the teeth whiteners were practicing dentistry without a licence and threatened them with criminal liability. Members of the Board had a clear interest in restraining competition since State legislation required six of the eight members of the Board to be licensed and practicing dentists. The Federal Trade Commission investigated the case and sued the Board for violating federal antitrust law. The Board claimed to be immune from antitrust laws as it was acting in accordance with State licensing regulations. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court ruled that State licensing boards that are controlled by market participants are not immune from federal antitrust scrutiny, unless they act in accordance with a clearly articulated State policy and are subject to active supervision in the State.

Reviewing licensing board regulation should also consider the organisation of boards and the tasks reserved for each occupation. Some States have almost 50 different boards regulating specific occupations with overlaps in services provisions, especially in healthcare, giving rise to conflicts over scope-of-practice restrictions. For instance, nurse practitioners and dental hygienists are often prevented from offering services that are fully within their competency or require supervision by a physician to do so (Adams and Markowitz, 2018; FTC, 2014; 2019). Such restrictions create barriers to productivity growth and should be balanced against the benefits of licensing health professions. The Ontario province in Canada implemented a radical reform of healthcare providers in 1991 to address problems of scope-of-practice and conflicts of interest (Safriet, 2002; Scheffler, 2019). A profession-specific licensing system controlled by members much like in the United States was transformed to one common regulatory regime for all health professions largely controlled by public appointees. In addition, an advisory council was charged with continually revisiting whether professions should be regulated or not and updating the regulatory framework.

The influence of professionals on licensing boards and on regulation, also through lobbying, may explain the modest reform action observed across States (Table 3.3). The push for licensing reforms has been strong for several years, not least from the federal level. Yet, cases of delicensing have been very rare and typically include licences with very limited use such as citrus fruit packers in Arizona and abstractors in Nebraska. A committee in Michigan reviewed 87 licensed occupations and recommended to delicense 20, but in the end only six occupations were delicensed. An earlier study identified only eight instances of delicensing in 40 years (Thornton and Timmons, 2015). Nevertheless, the limited action masks many failed attempts to reform (Kilmer, 2018; Rege et al., 2019). For instance, the House of Representatives in Florida passed a bill to delicense 24 occupations in 2011, but the Senate refused it as well as a number of subsequent bills. The resistance to delicensing emphasises the need for comprehensive sunrise reviews to avoid excessive licensing in the first place. Professionals tend to view licensing as the last step to raise the status of their profession, which can be a motivation to be licensed beyond the potential monetary benefits.

Table 3.3. Recent occupational licensing reforms at the State level

Selected reforms

|

State |

Year |

Reform |

|---|---|---|

|

29 States |

2015-19 |

Reduction of barriers to obtain a licensure for people with a criminal conviction. |

|

17 States |

2014-19 |

Exemption of natural hair braiders from a requirement to obtain a cosmetology, hairstyling or barber licensure. |

|

13 States |

2015-18 |

State agency established or assigned task to actively supervise licensing boards. |

|

13 States |

2015-18 |

Easing of licensing restrictions for military personnel and their families. |

|

7 States |

2014-18 |

Sunset review process implemented, typically with annual review of 20% of licensed occupations. |

|

Arizona |

2016 |

Delicensing of five occupations (assayers, citrus fruit packers, fruit and vegetable packers, driving instructors and yoga instructors). |

|

2017 |

Right to Earn a Living Act shifted the burden of proof to the government to justify that licensing is needed. |

|

|

2019 |

Automatic granting of occupational licensure to new residents with an out-of-State licensure. |

|

|

Arkansas |

2019 |

Broad licensing reform to reduce entry barriers and red tape (83 bills considered, 45 approved). |

|

Indiana |

2018 |

Local governments prohibited from imposing licensure requirements on State-licensed professions. |

|

Florida |

2017 |

Lower-income workers exempted from licensing fees. |

|

Michigan |

2013-14 |

Delicensing of six occupations (auctioneers, community planners, dieticians and nutritionists, immigration clerical assistants, ocularists and proprietary school solicitors), following a review of 87 occupations and recommendations to delicense 20 occupations. |

|

Nebraska |

2018 |

Delicencing of abstractors. |

|

New Mexico |

2018 |

Executive order requiring overhaul of all licences, including new reciprocity agreements and reduced fees. |

|

Ohio |

2019 |

All licensing boards set to expire every six years unless the legislature explicitly reauthorizes them. |

|

Tennessee |

2017 |

Delicensing of shampooing hair and licensure to massage animals made temporary. |

|

Utah |

2017 |

Licensure requirements reduced for electricians, plumbers and contractors. |

|

Wisconsin |

2017 |

Licensure requirements reduced for barbers, cosmetologists, aestheticians, electrologists and manicurists. |

Source: Kilmer (2018); Rege et al. (2019); Scheffler (2019); Institute for Justice; National Council of State Legislatures.

Successful reforms are often driven by the governor (Kilmer, 2018), as in the case of delicensing in Michigan and out-of-State licensure recognition in Arizona. Making licensing reform a legislative priority and appointing commissions to do the ground work can overcome resistance against reform. Arkansas achieved large-scale licensing reform during 2019 by appointing working groups involving many stakeholders and collecting good data to inform policymakers (Rege et al., 2019). Outside groups such as think tanks and consumer organisations have also helped to inform legislators and the public in some States, paving the way for reform. Some governors have used their power to act unilaterally through executive orders, for instance by mandating reviews of licensing requirements. However, a comprehensive order issued by the New Mexico governor in 2018 to bring regulation below the national average and increase reciprocity has so far had little effect. The federal government and State associations can support occupational licensing reform by sharing the successful experiences.

The federal government has several options to nurture occupational licensing reform, while largely preserving States’ control over the system. However, action at the federal level has been limited in recent years (Table 3.4) and more should be done to drive reform forward. As discussed above, federal intervention would be justified to remove barriers from lack of reciprocity across States. The European Union has achieved some success in this direction through a mixture of pre-emptory regulation, coordination of Member State efforts and judicial intervention (Box 3.5). In the context of competition policy, experience from the European Union also suggests that countries opted for a more independent and forceful regulator at the supranational level than any individual country ever did (Gutiérrez and Philippon, 2019). Correspondingly, the federal government may be less likely to be politically captured by licensure holders and lobbyists than State-level regulators. Under current legislation, the federal government has several available measures to promote licensing reform (Scheffler, 2019):

Reform licensing regulation within federal authority: The federal government has some limited authority over State licences for providers employed at federal agencies, such as military hospitals and the Department of Veterans Affairs. This power has been used to ease licensing restrictions to improve mobility and increase telehealth in recent years (FTC, 2017). While small in impact, it could set standards for States to adopt or pave the way for further federal regulation. Relatedly, States have taken significant action to reduce restrictions for people with a criminal record, which follows initiatives to reduce such restrictions from the federal administration.

Use fiscal support: Congress has provided targeted fiscal support to incentivise States to reform in specific areas. The Licensure Portability Grant Program supported the work on interstate compacts in healthcare, while licensing reciprocity for military spouses have been supported through the National Defense Authorization Act. In recent years, federal funding has been allocated directly to support broad occupational licensing reform in a number of States, although with limited amounts. Such fiscal incentives can help, but are unlikely to have a major impact without becoming costly and more or less prescriptive.

Step up antitrust enforcement: Intensifying the focus of the Federal Trade Commission and the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice on occupational licensing laws is a more promising avenue to remove barriers from licensing. As discussed above, the North Carolina Supreme Court case (Box 3.6) showed that States are not immune to antitrust scrutiny. Both agencies have advocated against excessive licensing regulation for a long time and recently stepped up efforts on scope of practice issues. This should be continued and if needed antitrust law should be clarified and strengthened to ensure unwarranted occupational licensing or unduly stringent licensing does not compromise competition, especially across State borders.

Use other federal programmes to generate additional pressure: The Affordable Healthcare Act increased the demand for healthcare providers and helped to push reforms to expand scope of practice for nurse practitioners. Reforming other federal programmes may similarly help to push States to take action.

Table 3.4. Recent occupational licensing reforms at the federal level

Selected reforms

|

Year |

Reform |

|---|---|

|

2011; 2016; 2018 |

Expansion of existing licensing reciprocity for military healthcare providers (federal employees), including through telehealth irrespective of location. |

|

2016 |

Reduction of federal licensing restrictions for people with criminal records (executive order). |

|

2016 |

USD 7.5M grant to fund research and technical assistance for improving geographic mobility of licensed workers (lead by NCSL). |

|

2018 |

USD 7M grant to support occupational licensing reform (allocated to 10 States and two associations of State governments). |

|

2018 |

States allowed to use federal education funds to review licences for unwarranted entry barriers. |

|

2019 |

USD 2.5M grant to ease licensing barriers for veterans and transitioning service members with military education and training. |

Source: Scheffler (2019); Institute for Justice; National Council of State Legislatures.

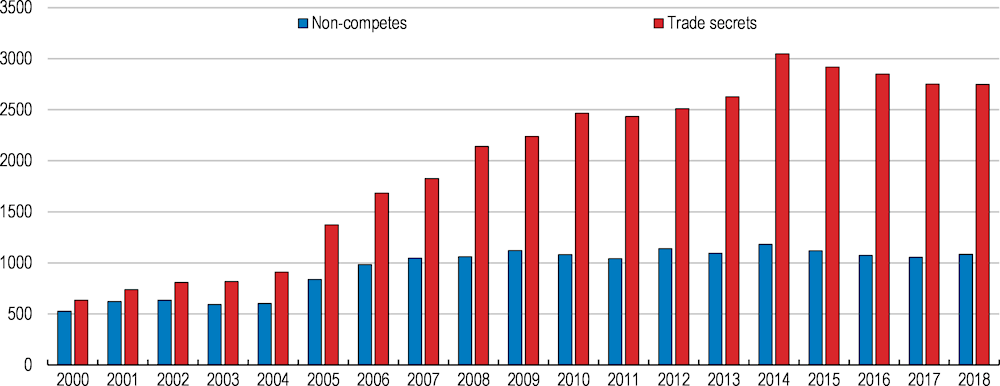

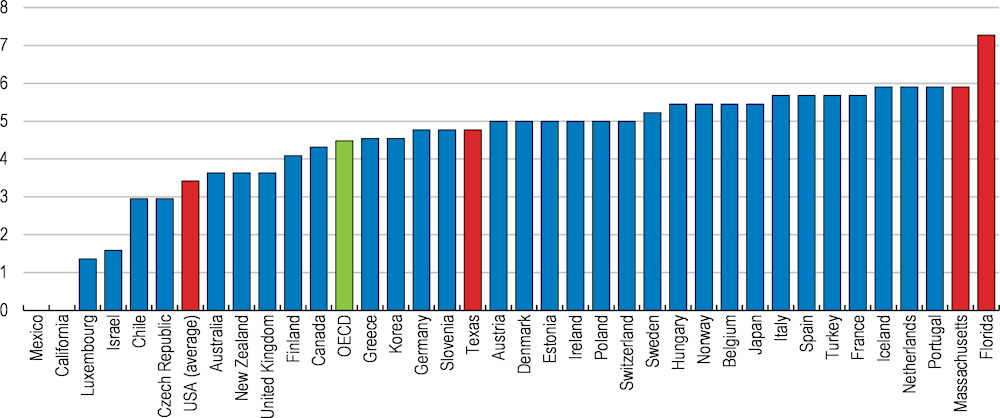

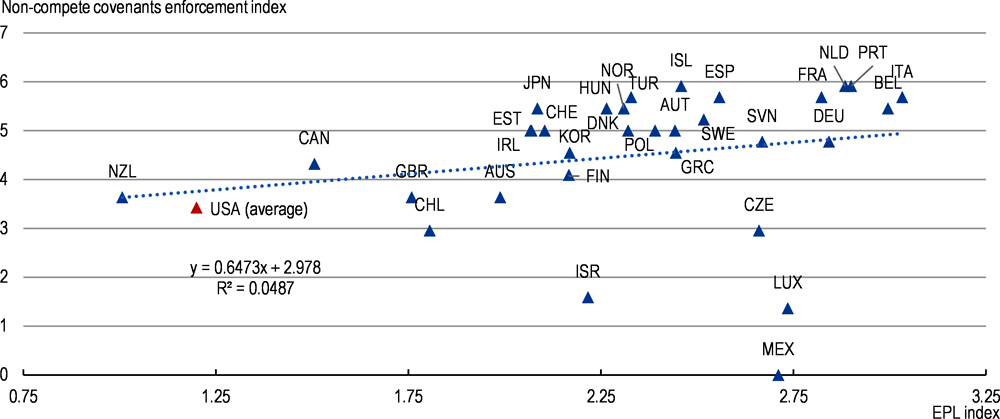

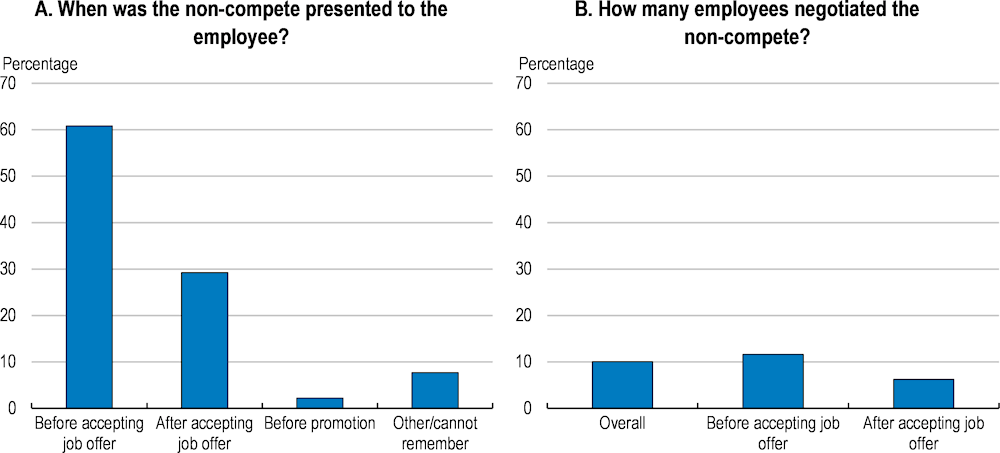

Non-competition agreements are often a bad deal for workers

Non-competition covenants (non-competes) in employment contracts is another restrictive measure that hinders labour mobility. By signing such a clause, employees are prohibited from moving to a competitor company or starting up a competing firm after they separate from the employer. The use of these types of clauses has been growing when measured by legal decisions (Figure 3.20). The number of cases has doubled since the early 2000s and the recourse to courts over trade secrets has jumped even further (trade secrets laws can also be used to restrict employee mobility, e.g. Contigiani et al., 2018). There are arguments for non-competes, particularly when on-the-job training is costly and building client relationships are important. In such circumstances, the employee should normally be compensated for agreeing to a non-compete. On the other hand, non-competes may hinder workers finding better quality jobs and deter entrepreneurship, with the risk that these contracts are used in an anticompetitive manner by some firms. Stringent use of restrictive clauses in employment contracts can thus depress both lifetime earnings and potentially productivity growth.

Figure 3.20. Court cases suggest a jump in the use of non-competition agreements

Estimates of federal and state court decisions on non-competes and trade secrets

Note: The latest years may be depressed by lags in reporting cases.

Source: www.faircompetitionlaw.com based on Westlaw database.