The Assessment and recommendations present the main findings of the OECD Environmental Performance Review of Latvia and identify 46 recommendations to help the country make further progress towards its environmental policy objectives and international commitments. The OECD Working Party on Environmental Performance reviewed and approved the Assessment and recommendations at its meeting on 24 April 2019.

OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Latvia 2019

Assessment and recommendations

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

1. Environmental performance: Trends and recent developments

Latvia’s small open economy has been continuously growing since 2010, after recovering from the global economic crisis. It has made progress on increasing per capita income and on other well-being indicators, although income levels are still well below those in many other OECD economies. Poverty and income inequality, regional disparities, and an ageing and declining population are holding back the process of catching up with more advanced economies.

The natural environment is a key economic asset, although Latvia has limited mineral and non-renewable resources. Agriculture, forestry and fishery account for a larger share of value added than in most other OECD Europe countries. Natural resource-intensive products (wood products and paper, agricultural and food products) account for 40% of merchandise exports. With more than half its territory covered in forests, Latvia is among the world’s leading exporters of wood pellets, and woody biomass is its major domestic energy source. Its forests, wetlands and seaside are deeply rooted in its cultural identity and attract growing number of tourists every year.

Latvia made some progress in decoupling economic growth and environmental pressures such as greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and most air pollutants. Implementing the European Union (EU) environmental acquis and EU-funded investment brought about improvement in environmental performance in areas such as residential energy efficiency, wastewater treatment and waste management. However, more needs to be done and there is a need to better align environmental and economic development objectives. Some environmental pressures are likely to persist with sustained economic growth and higher income levels. These include emissions of GHGs and air pollutants; material use and waste generation (Section 4); release of nutrients to the sea and pressures on habitats and species (Section 5).

The energy sector plays a key role in decarbonising Latvia’s economy

Renewables cover a large and growing share of Latvia’s energy needs

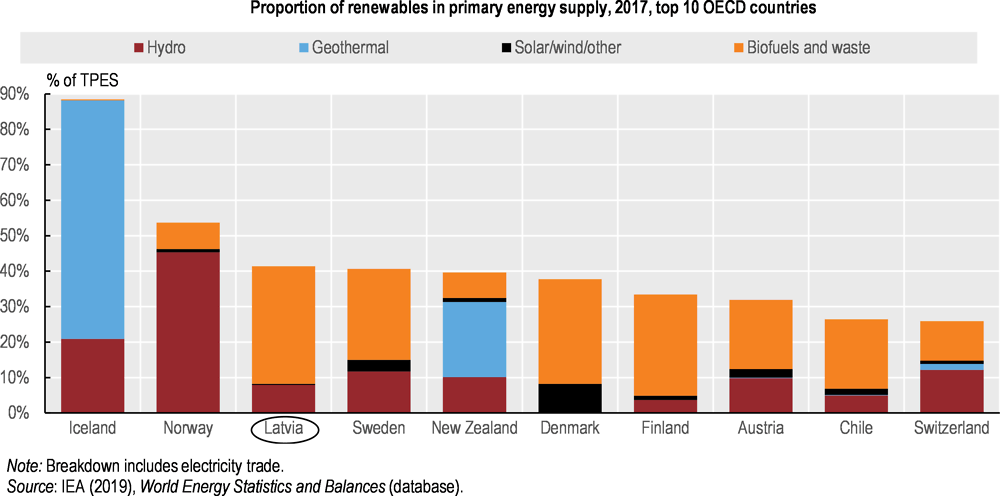

Renewable energy sources account for 40% of the country’s primary energy supply and more than half of electricity generation, on average – one of the highest shares in the OECD (Figure 1). Solid biofuels (wood pellets, wood chips, charcoal, wood waste and residue, and straw) are the main renewable source. They account for a third of the energy mix, the highest share in the EU. Hydropower is the other main renewable source and delivers most of the country’s electricity. Wind and solar power generation remains negligible despite good potential (Lindroos et al., 2018). Fossil fuels, mostly natural gas and oil, cover the remaining energy needs.

The share of renewables in the energy mix has grown in the last decade. A generous feed-in tariff system has fostered the use of solid biofuels in combined heat and power (CHP) plants (Section 3). This has brought Latvia on track to reach its overall 2020 EU renewable energy target, and to exceed the indicative target in the heating and cooling sector. However, additional power generation is needed to meet the indicative renewable electricity target. Renewables cover less than 3% of transport fuel consumption, far from the EU 2020 target of 10% (Section 3). Given the current and expected increasing role of solid and liquid biofuels, Latvia should identify and assess synergies and trade-offs between further developing biofuel production and use and policy objectives related to climate, air pollution, water, land use and biodiversity.

Figure 1. Latvia is among the OECD leaders in the use of renewable energy sources

Energy intensity has declined, but there is scope for large energy savings

Total final energy consumption decreased by 7% over 2005-16, despite sustained economic growth for most of the period. As a result, the final energy intensity of the economy declined, but remains above the OECD average. Latvia needs to tackle increasing energy consumption in agriculture, industry and transport, along with high energy use in buildings, to achieve the 2020 energy intensity and energy savings targets of the National Energy Efficiency Action Plan.

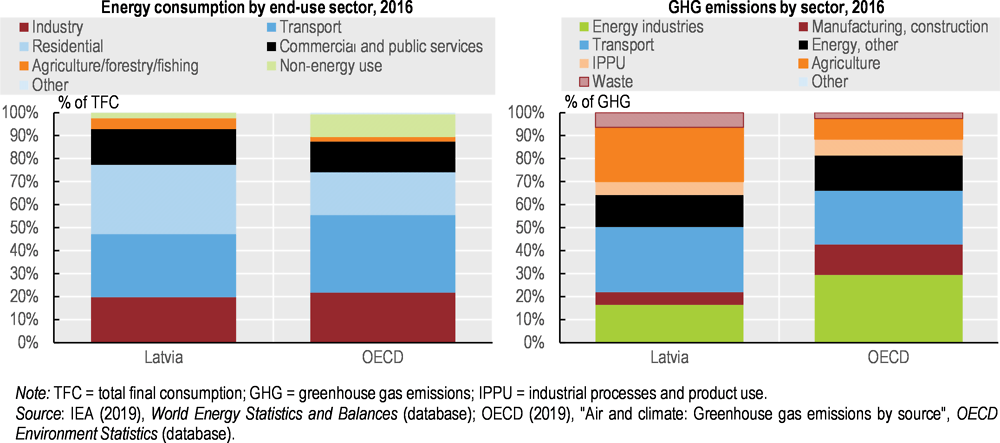

The residential sector is the main energy user, accounting for 30% of energy consumption, above the OECD average (Figure 2). Despite a decline in residential energy use, the building sector is still highly inefficient. Several barriers remain to investment in improving the energy performance of buildings; in addition, investment in improving industry energy efficiency is insufficient (Section 3).

Transport (road-based in particular) is the second largest energy user, the main source of GHG emissions and a major source of air pollutants (Figure 2). Latvia’s vehicle fleet is largely above ten years old and diesel-fuelled, and new cars are carbon-intensive. The fleet is growing even as the population declines. The trend is linked to rising income levels combined with suburbanisation and the low density of rural areas, which prevent the development of efficient public transport services (Section 3).

Latvia needs to maintain efforts to further curb GHG emissions

GHG emissions have been decoupled from economic growth

The GHG emission intensity of the Latvian economy has declined since 2010. It has remained well below the OECD average owing to a progressive switch from fossil fuels (mainly natural gas) to biomass for heat and power production, improved energy efficiency, small industrial base and still relatively low incomes. After having broadly followed the economic cycle in the 2000s, GHG emissions declined in the early 2010s and have stabilised since 2013, despite sustained economic growth. Overall, total GHG emissions have decreased moderately, by 1.3%, since 2005.

Figure 2. Latvia has distinct energy use and GHG emission profiles

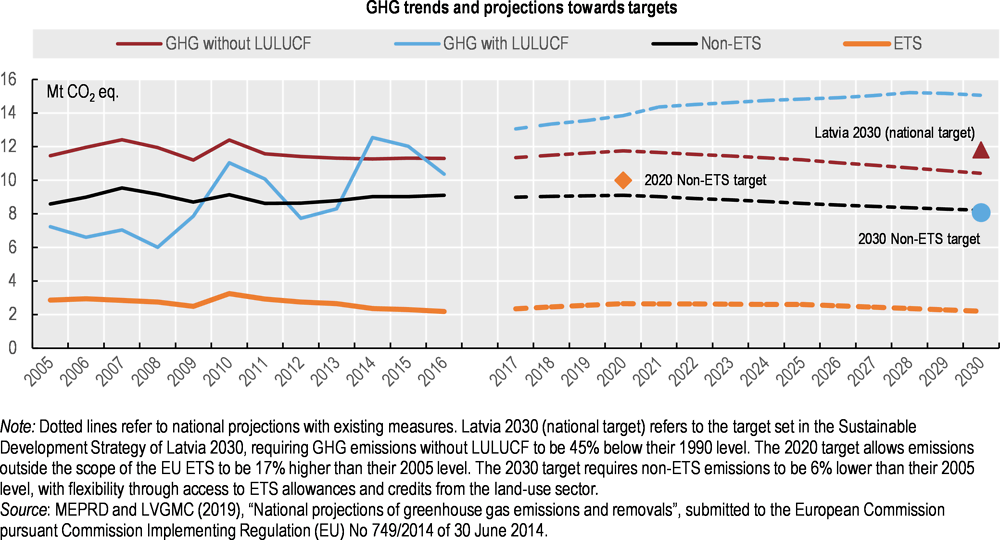

Therefore, Latvia is poised to meet its 2020 target under the EU Effort Sharing Decision of limiting the increase in GHG emissions to 17% of the 2005 level (Figure 3). The target covers emissions from sectors outside the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), mostly from transport, agriculture, buildings, small industrial facilities and waste. The EU‑wide cap-and-trade system covers only about a fifth of Latvia’s emissions, i.e. from large power plants, most energy-intensive industrial installations and aviation. The small size of this share reflects Latvia’s large share of emissions from transport (28%) and agriculture (24%), and lower-than-average shares of emissions from energy generation and industrial energy use (Figure 2). The result is that most of the country’s mitigation efforts have to rely on domestic policies in the agriculture, residential and transport sectors.

Latvia needs to follow through on planned measures to meet long-term climate goals

Projections show GHG emissions, excluding the land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector, declining to 9% below the 2005 level by 2030. Emissions from power and heat generation, transport, and the residential and commercial sectors are projected to decrease. To realise the projections, it is essential for Latvia to fully implement planned measures to promote switching to renewables and improve the energy efficiency in buildings and industry. The adoption of cleaner vehicle technology and alternative transport fuels is expected to mitigate GHG emissions associated with increasing freight and passenger traffic (LEGMC and MEPRD, 2019).

However, emissions from agriculture are expected to continue rising with expansion of agricultural land, cultivation of organic soils, growing amounts of production and livestock, and increased use of nitrogen fertilisers (LEGMC and MEPRD, 2019). Agriculture is projected to account for 30% of GHG emissions in 2030, with growth partially offsetting reductions in other non-EU ETS sectors. Overall, projections show non-EU ETS emissions decreasing by 4.4% by 2030 from 2005, and Latvia missing the 2030 target of a 6% cut in these emissions (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Latvia will likely meet its 2020 GHG mitigation target but not the 2030 target

With LULUCF, total GHG emissions are projected to more than double from the 2005 level by 2030 (Figure 3). The LULUCF sector’s carbon sequestration capacity has declined markedly since 2005. The sector became a net GHG emitter in 2014 for the first time. Increased logging, forest ageing and conversion of grasslands into croplands will continue to reduce GHG removal capacity.

Latvia is preparing its National Energy and Climate Change Plan 2021-30, in line with EU requirements, and its Low Carbon Development Strategy 2050, as required by the Paris Agreement. The draft of the strategy, which is expected to be approved by the end of 2019, envisages reducing GHG emissions by 80% by 2050 from the 1990 level. The strategy should be integrated in a development planning framework covering the same time horizon (Section 3). Given the key economic and environmental roles of agriculture and forestry in Latvia, any climate change mitigation plan or strategy should include analysis of options for mitigating GHG emissions from these sectors, taking into account economic, social and environmental considerations. Options would include aligning price signals by removing implicit support measures to agriculture and to biomass production and use (Section 3). The long-term climate mitigation strategy should be based on a quantitative assessment of the climate mitigation and environmental benefits and impacts of using domestically produced biofuels, compared with those for other energy sources.

Planning for adaptation to climate change is at an early stage

Latvia is experiencing the impact of climate change, with higher mean annual temperature and increases in intensity and frequency of rainfall. Long-lasting periods of intense rainfall resulted in severe flooding events, such as in August-October 2017. In 2018, the government developed a draft plan for climate change adaptation up to 2030. Once it is adopted, its implementation will need to be closely monitored to ensure that actions are under way and can be adjusted as new information becomes available. Sectors identified as particularly vulnerable to climate change are biodiversity and ecosystem services; forestry and agriculture; tourism and landscape planning; health and welfare; building and infrastructure planning; and civil protection and emergency planning. In 2018, Latvia amended its legislation on environmental impact assessment (EIA) to require evaluation of the impact of climate change on development projects.

Air pollution has declined but its health impact persists

There has been an absolute decoupling of emissions of the main air pollutants from GDP growth since 2005. The decline in air emissions was driven by lower use of fuelwood in individual heating installations and strengthened vehicle standards. Latvia met its 2010 targets under the EU National Emission Ceilings Directive for sulphur oxides (SOx), nitrogen oxides (NOx), ammonia and non-methane volatile organic compounds. However, additional efforts will be needed to meet the 2020 and 2030 targets for NOx and ammonia and the 2030 target for fine particulate matter (PM2.5). Ammonia emissions have been rising with fertiliser use (OECD, 2019a). Strict enforcement of emission standards, increased use of best available techniques and higher tax rates on air emissions can help in meeting air emission targets (Section 3).

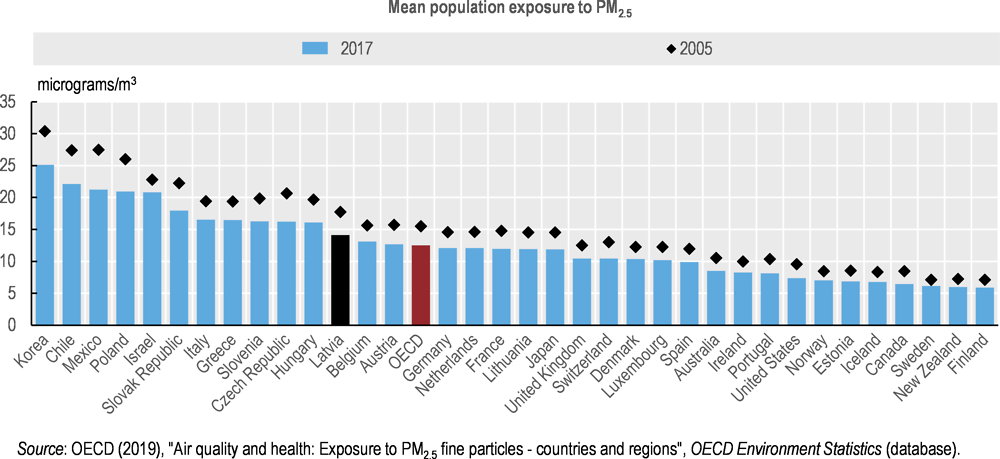

Air quality has improved over the past decade. Concentration levels of nitrogen dioxide and ozone are lower than in most other EU countries. Mean population exposure to PM2.5 has declined, but Latvia’s population is exposed to higher average concentrations of PM2.5 than in most other OECD countries (Figure 4). Close to 90% of the population is exposed to PM2.5 levels higher than the World Health Organization guideline value of 10 µg/m3. Exceedances of the PM10 and NOx limit values prompted the Riga municipality to implement several air quality action programmes, most recently for 2016-20, to address emissions from vehicle use and industrial activities. The air quality monitoring network needs to be extended and upgraded.

Latvia’s population is vulnerable to the health impact of air pollution due to the compound effect of its relatively poor health status, ageing, the persistence of risk factors (e.g. smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity) and uneven access to good quality health care (OECD, 2016a). This mix of factors explains Latvia’s high estimated mortality and welfare costs from exposure to outdoor PM2.5, with an estimate of over 600 premature deaths per million inhabitants, more than double the OECD average. The welfare cost of PM2.5 pollution has declined, but is still put at 6.9% of GDP, the second highest in the OECD (OECD, 2019b).

Figure 4. PM2.5 concentrations are high by international comparison

There is room to further improve material productivity and waste recovery

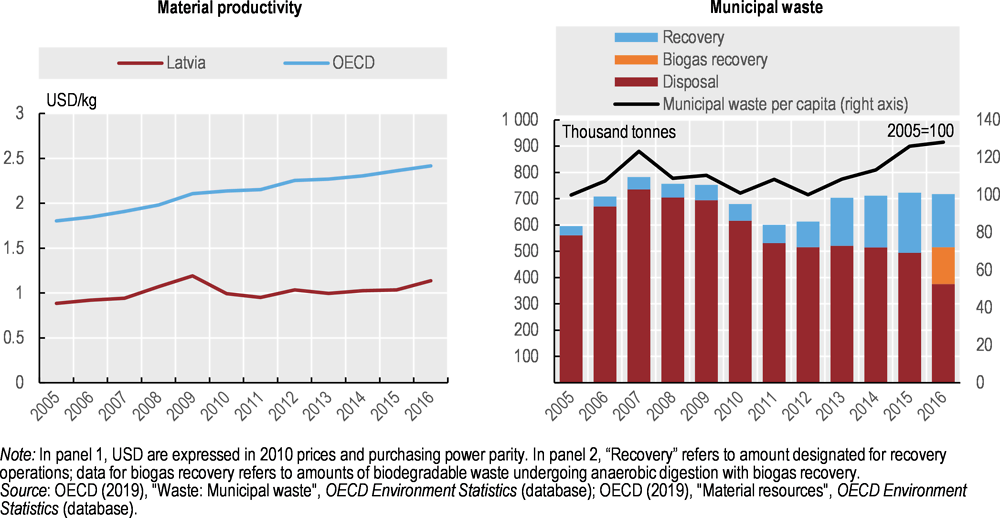

Domestic material productivity (GDP per unit of domestic material consumption) improved by 29% over 2005-16, albeit from a low level; it is still less than half the OECD average. Biomass dominates the materials mix, reflecting the country’s large wood processing sector and the use of biomass as an energy source.

Waste management is a challenge. The amount of waste generated more than doubled between 2004 and 2016, driven by economic development and insufficient incentive for prevention. Municipal waste generated per capita rose by 28%, though the recovery rate also grew, from 5% in 2005 to about 30% in 2016, or 45% if taking biodegradable waste recovery for biogas production into account. These developments benefitted from increased landfill charges, separate collection and extended producer responsibility programmes, and EU financial support. However, landfilling is still used more than in many other OECD countries (Section 4).

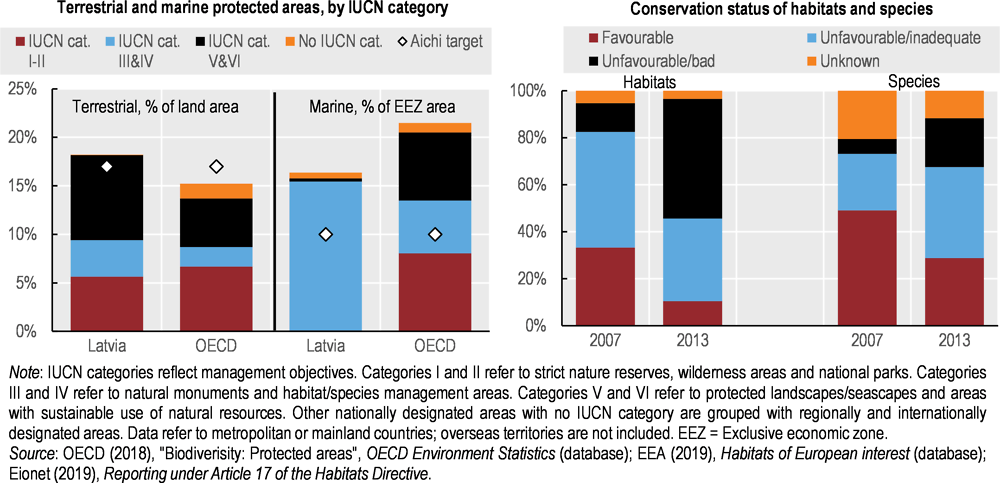

Stronger measures are needed within and outside protected areas

Forests, grasslands and wetlands, as well as agricultural land, are home to abundant biodiversity and ecosystems. To preserve its living standards, Latvia needs to significantly boost efforts to reduce pressures from intensive resource use, land-use change, fragmentation, pollution and agricultural expansion. Latvia surpasses the 2020 Aichi targets for terrestrial and marine protected areas, but the majority of habitats and species are in an unfavourable state. Developing and implementing additional management plans in protected areas, combined with adequate options to conserve biodiversity outside protected areas, could be an effective way to halt biodiversity loss (Section 5).

More efforts are urgently needed to achieve good environmental status under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive. Latvian marine waters are affected by nutrient pollution and eutrophication, discharges of hazardous substances, invasive species and marine litter (EC, 2017a; EC, 2019), which all put pressure on marine biodiversity. Some commercial fish stocks in the Baltic Sea have declined or are depleted (Section 5).

Water services have improved but pressures on water bodies are high

Although water resources are abundant, their quality is threatened

Latvia has considerable water resources and low and declining levels of water abstraction per capita. It has river basin management plans (RBMPs) for its four river basin districts (Daugava, Lielupe, Venta and Gauja). The second cycle RBMPs show the ecological status of water bodies to be below the EU average.1 Only about 20% of identified surface water bodies have high or good ecological status, and about 20% have poor or bad status. The chemical status of most surface water bodies is still unknown.

Diffuse pollution from agriculture, point-source pollution and morphological alterations are the main pressures on water bodies. The growing use of nitrogen fertilisers has resulted in an increased nitrogen surplus (although from relatively low levels), potentially affecting water and soil quality.

More people have access to good water services

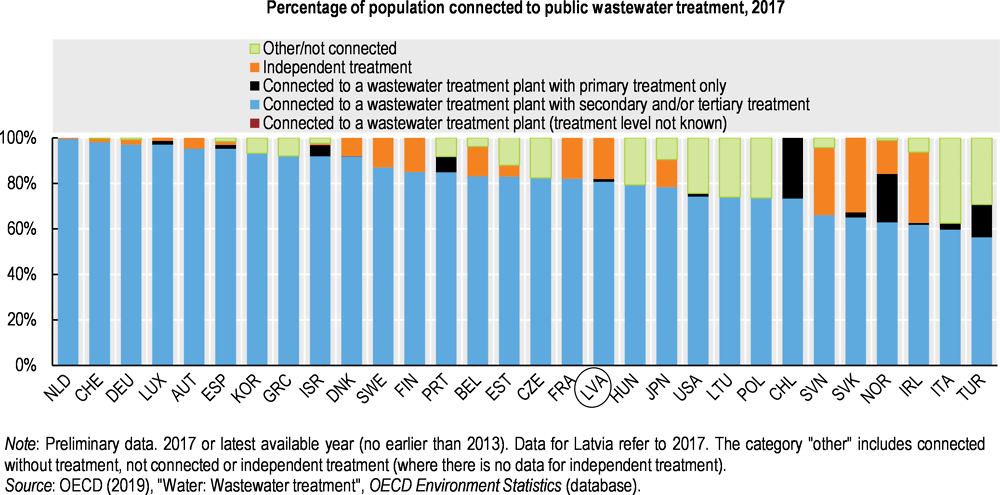

Public investment, largely EU-funded, has helped improve water infrastructure and widen access to water and wastewater management services. The share of population connected to a wastewater treatment plant reached nearly 82% in 2017, mostly with tertiary treatment. The connection rate is below many other OECD countries (Figure 5) due to the high cost of connecting sparsely populated areas to the network, reducing tariff affordability. Latvia has achieved good compliance under the EU Urban Waste Water Framework Directive, which helped improve bathing water quality: nearly all bathing waters are of excellent or good quality. However, part of wastewater in 14 agglomerations is treated through individual systems potentially inappropriate for environmental protection (EC, 2019). Large quantities of sludge are disposed of at temporary storage sites.

The quality of drinking water has generally improved over time, but varies depending on whether it is from large or small water supply zones. The 30 large water supply zones, covering about 60% of the population, reached a very high level of compliance with all parameters in the EU Drinking Water Directive. Small water supplies have lower rates of compliance with chemical parameters, due largely to natural high iron concentrations and the high investment cost for removing iron.

Figure 5. Most of the population has access to advanced wastewater treatment

Box 1. Recommendations on climate, air and water management

Mitigating climate change and adapting to its impact

Ensure that any new climate mitigation strategy is consistent with a cost-effective pathway towards being a net zero GHG emission country by 2050; guide this transition with a plan that identifies the expected contribution of each economic sector to domestic emission mitigation and lays out gradually stricter targets.

Improve the knowledge base on available mitigation options, especially in the agriculture and forestry sectors, along with their costs and trade-offs, building on sound socio-economic and environmental indicators; assess and quantify the climate mitigation and environmental benefits and impact of using domestically produced biofuels, comparing them with those of other energy sources.

Adopt the draft national plan for climate change adaptation to 2030 and monitor its implementation; ensure compliance with the legislative requirement of considering climate change impact and resilience in EIA procedures; assist municipalities in integrating climate change adaptation in their land-use and development plans.

Improving air quality

Improve and extend the air quality monitoring network; promote adoption of best available techniques in the household, transport, industry and energy sectors and thoroughly enforce compliance with emission standards; integrate air quality objectives and measures in climate, energy, transport, agriculture and tax policies and plans, with a view to reducing emissions from PM2.5, NOX and ammonia.

Strengthen implementation of the current air quality action programme in the Riga metropolitan area to reduce emissions from vehicles, industrial facilities and households; update the programme to introduce additional measures for the post-2020 period; consider establishing low-emission zones while ensuring adequate public transport services.

Ensuring good water quality and services

Improve monitoring and evaluation of the quality of water bodies; identify environmental pressures and possible risks.

Reduce diffuse water pollution from agriculture through a combination of measures: regulatory (e.g. technology, performance standards), economic (e.g. taxes on fertilisers and pesticides) and voluntary (e.g. awareness-raising initiatives, training).

Complement EU funds with national public and private investment to upgrade wastewater treatment and water supply infrastructure; ensure that independent wastewater treatment systems comply with environmental regulations; improve small-scale water supply systems (e.g. wells) to extend access to good quality drinking water.

Undertake a feasibility study to assess cost-effectiveness of alternative sludge reuse or disposal options and prepare to implement the best solution.

2. Environmental governance and management

Latvia has a centralised system of environmental governance, with stable institutions and a strong emphasis on public participation. The regulatory framework has been reinforced through alignment of the country’s environmental legislation with EU directives. However, the adoption of good practices for implementing environmental law has been uneven, with significant room for improvement in compliance assurance. Co‑ordination across the central government is insufficient for adequate integration of environmental considerations into sectoral policies or for implementation of cross-sectoral policies, such as those concerning transition to a circular economy.

Institutional stability is adequate but effective co-ordination lacking

The majority of environmental policy and regulatory powers is in the hands of the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development (MEPRD) and its subordinate institutions. Institutional stability since 2011 has contributed to the higher quality of human resources of environmental authorities. However, their financial resources and staff continue to be below the levels of 2007, before the recession and related budget cuts. The Ministry of Economy plays a key role in the energy sector, and the Ministry of Agriculture in forestry and fisheries.

Data are shared through multilateral or bilateral co-operation agreements between public authorities (EC, 2017a). The Cross-Sectoral Co‑ordination Centre under the Prime Minister’s Office oversees implementation of the sustainable development strategy and national development plan and promotes coherence among sectoral policies. It is largely advisory, however; its opinions may be discussed by the cabinet but are not binding. This is insufficient to ensure good inter-ministerial co‑ordination on environment-related policies.

Local governments are responsible for land-use planning and environmental services. Vertical coherence of local spatial and development planning with national and regional planning documents is required by law, but local implementation is often inconsistent with national policy objectives. Local plans follow regulatory environmental requirements but appear to be dominated by development priorities and are not directly affected by municipal sustainable development strategies.

Regulatory requirements have improved but need better impact assessment

Latvia has firm constitutional guarantees in the environmental domain. Strategic environmental assessment is conducted for all planning documents in relevant sectors. Yet assessment quality is uneven due to a shortage of competent experts. Regulatory impact assessment (RIA) is supposed to consider the environmental impact of draft laws and regulations, but does so only superficially and does not involve appropriate cost-benefit analysis. Latvia ranks last in the OECD on RIA quality (OECD, 2018a). Post‑implementation reviews are mandatory for plans and expected to be introduced for regulations once the relevant methodology is approved (OECD, 2018b).

Harmonisation with EU requirements on environment has substantially improved the regulatory framework, particularly in waste management and nature protection. The EIA process is well developed; EIA conclusions are considered in permit determination. Latvia follows good international practice in using general binding rules for several industrial sectors and cross-sectoral activities with low environmental impact.

Compliance monitoring, enforcement and damage remediation need to be strengthened

Latvia has been slow to adopt good international practices in compliance assurance. This is particularly true with regard to inspection planning, administrative enforcement and liability, where good international practices co-exist with historical approaches common in Eastern European countries. Further reforms in these areas are needed to achieve greater coherence and effectiveness of policy implementation.

The number of inspections for all categories of installations has been declining since 2009, primarily due to resource shortages. Despite the introduction of risk-based planning, a good international practice, detection of non-compliance did not improve. The State Environmental Service (SES), Latvia’s enforcement authority, has not published any criteria for determining a proportionate response to various types of non-compliance behaviour. There are no specific criteria for levels of administrative fines. The fines do not reflect the economic benefit the offender receives from non-compliance behaviour – a common shortcoming in most OECD countries. Average fines are low, and only 80% of fines imposed on enterprises are paid voluntarily or after a first warning – a rather low collection rate by international standards. Criminal enforcement focuses primarily on nature conservation offences. The SES does not collect data by which to evaluate enforcement tools’ effectiveness (EC, 2017a).

Latvia’s regime of liability for current damage to the environment incorporates remediation-focused provisions required by EU legislation, which include procedures for detection and remediation of environmental damage. When remediation is impossible, Latvia requires monetary compensation, calculated according to fixed rates per pollutant or damaged species. The revenue goes to the state budget but is usually not spent on restoring the environment. As the use of financial guarantees against environmental damage is voluntary and very limited, there is a significant burden on the state for environmental remediation in case the responsible party is insolvent. Cleanup of pre-1990 contaminated sites is also a challenge for the government: it is proceeding slowly and relies heavily on donor funding.

The country is making some progress in promoting voluntary compliance and green business practices. For example, the annual number of new certifications to the ISO 14001 environmental management system standard grew more than ninefold over 2007-17 despite a lack of government incentives. However, compliance promotion by Regional Environmental Boards, voluntary agreements with industry and recognition of environmental excellence remain sporadic. Latvia assigns priority to green public procurement but has relatively modest near-term targets for the share of green purchasing in total public procurement (Section 3).

There is a high degree of public openness but insufficient awareness raising

Latvia ranks second on the 70-country Environmental Democracy Index (WRI, 2019). It gives the public broad opportunities to take part at an early stage in most decisions affecting the environment. The MEPRD has established multiple consultative bodies to engage professional associations, non-government organisations, businesses and academia in various policy areas. However, the general public does not actively participate in local environment-related decisions. This is due in part to insufficient awareness raising beyond formal education curricula.

The public has practically unrestricted access to environmental information. There are information systems for environmental quality data, permits, land-use planning and biodiversity conservation, as well as a pollutant release and transfer register, all open to the public. However, user-friendliness of environmental information could be improved.

Rules for appealing environmental decisions are often more favourable to the public than general administrative appeal procedures (European e-Justice Portal, 2018). Judges receive environmental training. Administrative courts are extensively used to review EIA results and environmental permits. However, appeal procedures can be quite lengthy.

Box 2. Recommendations on environmental governance and management

Strengthening the institutional and regulatory framework

Reinforce the role of the Cross-Sectoral Co-ordination Centre in inter-ministerial collaboration to promote coherence of sectoral policies with the country’s sustainable development objectives; enhance the central government’s oversight of municipal land-use planning and environmental service delivery.

Strengthen environmental aspects of regulatory impact assessment; ensure that environmental and social costs of proposed laws and regulations are appropriately quantified; enhance the use of ex post regulatory and policy evaluation.

Improving enforcement and compliance

Expand the use of risk-based planning of environmental inspections to improve detection and deterrence of non-compliance.

Reform the system of enforcement sanctions by adopting sound methodology for determination of administrative fines, based on the gravity of the offence and economic benefit of non-compliance; develop an enforcement policy with clear guidance on proportionate use of administrative and criminal sanctions and evaluate their effectiveness.

Facilitate full implementation of environmental liability regulations to ensure remediation of damage to the environment at the expense of the responsible party; require financial guarantees for potential environmental damage from hazardous activities.

Accelerate the cleanup of old contaminated sites by securing adequate financial resources.

Enhance efforts to promote environmental compliance and green business practices by using information-based tools and regulatory incentives as well as by expanding green public procurement; support voluntary business initiatives.

Enhancing environmental democracy

Expand environmental awareness raising and adult education, and more actively engage the general public in local environmental decision making.

3. Towards green growth

Latvia is on a good pathway towards reaching many of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (OECD, 2019c). It has significant opportunities to accelerate the transition towards a low-carbon, greener and more inclusive economy, especially by investing in energy efficiency, renewables, sustainable forestry and sound waste and material management. To seize these opportunities, it should make better use of economic instruments, remove potentially perverse incentives and improve the quality of its environment-related infrastructure and services. At the same time, Latvia should tackle poverty and regional disparities, as well as invest in education, research and innovation. This will help the country further diversify its exports towards products and services with higher technological content and value added.

Latvia has a comprehensive framework for sustainable development

Latvia has legislation envisaging vertically and horizontally co‑ordinated development planning documents with a 2030 horizon. The Sustainable Development Strategy of Latvia 2030 (Latvia 2030) is the highest-level and longest-term development plan, and it is broadly consistent with the SDGs. The seven‑year national development plans (NDPs) include main policy objectives, outcome indicators and indicative financing for most sectors of the economy. Latvia is also working on a Low-Carbon Development Strategy 2050. However, it is not always clear how Latvia 2030 and the NDPs ensure coherence among policies. There is scope for further integrating environmental objectives in sectoral policies, and the post-2020 planning cycle provides an opportunity to do so. The law-enshrined 2030 horizon is too short to allow for the radical economic and societal changes implied by the Paris Agreement and the EU long-term climate ambition.

There is scope to further green the system of taxes, charges and subsidies

Environmentally related taxes generate high revenue but their effectiveness is limited

Latvia has long applied a wide range of environmentally related taxes and charges. Since 2015, the government has raised energy taxes and the natural resource tax, removed or reduced some tax exemptions and reformed vehicle taxation. These are all welcome steps. In 2016, revenue from environmentally related taxes accounted for 12.6% of total tax revenue and 3.8% of GDP. While well above the respective OECD averages, these shares are not an indicator of tax effectiveness. Overall, environmentally related taxes have delivered few tangible environmental outcomes (Jurušs and Brizga, 2017). Latvia needs to raise more revenue to finance its high spending needs (including for infrastructure investment, education and health), while at the same time further reducing the tax burden on low-income households (OECD, 2019d). Expanding the use of environmentally related taxes could help achieve both goals, in addition to their main objective of encouraging more efficient use of energy, materials and natural resources.

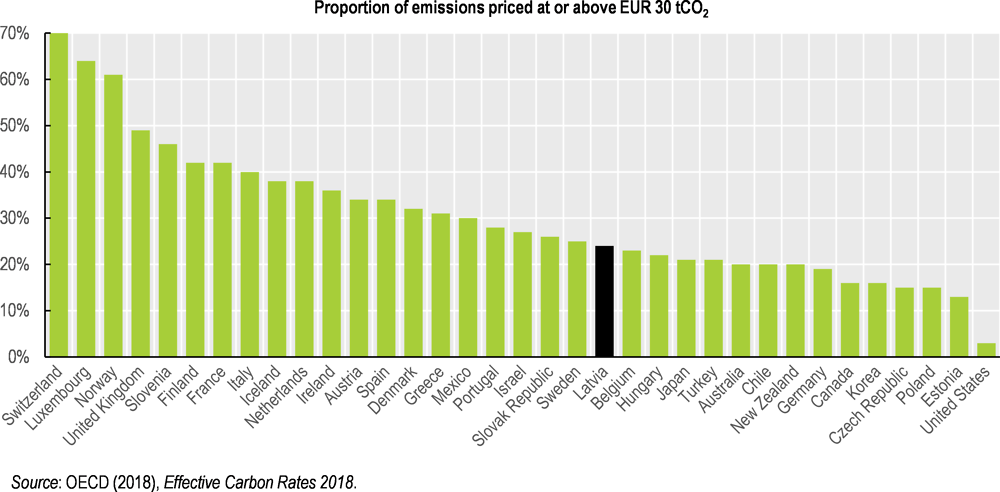

The carbon price signal is weak

Latvia puts a price on CO2 emissions via energy taxes, a carbon tax and participation in the EU ETS. The trading system covers only about 20% of Latvia’s emissions, due to the country’s economic structure and biomass-based energy mix (Section 1). It has had limited effect in promoting low-carbon investment, given the surplus of emission allowances, free allocations to the manufacturing sector (in accordance with EU regulations) and low carbon prices in the market. The carbon tax applies to CO2 emissions of stationary facilities outside the scope of the EU ETS (i.e. small heating, industrial and commercial facilities). In 2017, the government raised the carbon and energy tax rates as part of a broader tax reform. However, the rates do not fully reflect the estimated environmental cost of energy use and CO2 emissions. The carbon tax rate is EUR 4.5 per tonne of CO2 (t CO2), well below a conservative estimate of the social costs of CO2 emissions, EUR 30/t CO2 (OECD, 2018c). Emissions from biomass and peat combustion are exempt from the carbon tax, although peat is a non-renewable fuel with high carbon content and the lifecycle carbon neutrality of biomass is increasingly debated (OECD, 2018c). Tax rates on fuels are also low and many tax exemptions are in place. There is a wide tax gap between petrol and diesel, despite diesel’s higher carbon content and local air pollution cost.

Effective tax rates on CO2 emissions from energy use in road transport are the lowest in OECD Europe, and those on emissions from other energy uses are among the ten lowest in OECD Europe (OECD, 2018d). Accounting for energy and carbon taxes and the EU ETS allowance price, 55% of CO2 emissions from energy use face some kind of carbon price signal in Latvia, the fifth lowest share in the OECD. This reflects the high share (34%) of energy sourced from biofuels, which are mostly not taxed. Three-quarters of emissions, i.e. nearly all emissions from sectors other than road transport, are priced below the low-end benchmark value of EUR 30/t CO2 or are not priced at all (Figure 6).

High support to fossil fuel use runs counter to energy savings objectives

Despite progress in removing tax exemptions, fuel use in many sectors is still exempt or benefits from reduced rates. The fuels involved include biodiesel from rapeseed oil and some fuels used for heating and in agriculture, fishing, electricity generation and industry. This undermines the carbon price signal and the government’s efforts to improve energy efficiency and reduce CO2 emissions across the economy. A Ministry of Finance review of tax expenditure, conducted since 2011, shows that these exemptions weigh heavily on the government budget. Support for fossil fuel consumption is high. When measured as a share of energy tax revenue, Latvia’s level of fossil fuel consumption support is among the ten highest in the OECD. Fossil fuel consumption support hovered around 25% of energy tax revenue in 2006‑16. This included payments to CHP plants using natural gas.

Latvia should consider reducing tax exemptions and further raising the energy and carbon tax rates to reflect environmental and climate damage from energy use. Increasing transport fuel taxes could also help make the tax system more progressive (Flues and Thomas, 2015). However, energy affordability is still an issue in Latvia, as in other Central and Eastern European countries. Providing targeted social benefits that are not linked to energy consumption (e.g. income-tested support) can help address any adverse impact of higher taxes on low-income households and other vulnerable groups (Flues and van Dender, 2017).

Figure 6. Only a quarter of CO2 emissions face a sufficiently high carbon price

Taxation of other pollution and natural resource use is well developed

A broad-based tax on pollution and natural resource use, the so-called natural resource tax, has been in place since 1991. It applies to water and natural resource extraction, water and air pollution, CO2 emissions, waste disposal, packaging materials and environmentally harmful goods (such as oil, tyres and electric appliances). This tax accounts for about 3% of environment-related tax revenue. In 2014 and 2017 most tax rates increased by between 20% and 25%. However, rates are still relatively low and some have been stable for several years, including those on emissions of the air pollutants NOX and ammonia, for which Latvia is not on track to reach its 2020 and 2030 targets (Section 1).

Several tax exemptions have hindered the environmental effectiveness of the natural resource tax and reduced its revenue to about one-tenth of what it could be. An exemption applies to packaging materials and environmentally harmful goods for companies that join extended producer responsibility systems and meet the corresponding recycling and recovery targets. The tax rates double in case of non-compliance with the targets. This exemption has helped expand participation in extended producer responsibility programmes to over 90% of regulated companies and improve recycling and recovery (Section 4). However, it mainly acts as a fine; it does not stimulate companies to go beyond the set targets, nor does it sufficiently encourage waste prevention. An ongoing review of the natural resource tax legislation aims to link the exemptions to stricter performance requirements.

The CO2-based car tax is welcome, but perverse incentives to road transport remain

In 2017, Latvia restructured the annual tax on cars and linked it to CO2 emissions (for vehicles registered since 2009). The new system is a step forward, as it aims to encourage renewal of the car fleet with more fuel-efficient vehicles. The previous system had not been effective in this respect: the vehicle fleet is particularly old and energy intensive (Section 1). However, a vehicle tax based exclusively on CO2 emissions, without consideration of local air pollutants, can stimulate further dieselisation of the fleet, with adverse effects on urban air quality (EEA, 2018). Taxation of heavy goods vehicles does not consider environmental parameters. Road tolls for trucks are differentiated by test-cycle engine emission level, though the differentiation is not pronounced and the toll does not change with distance travelled. Nor do road tolls apply to passenger vehicles.

Latvia imposes a company car tax at company level, but is among the few EU countries not taxing employees for the benefits arising from their personal use of company cars (EC, 2017b). This tends to encourage private car use and long-distance commuting, potentially leading to higher GHG and local air pollutant emissions, noise and congestion. This adds to problems related to disorganised suburbanisation around Riga and difficult access to public transport in many peripheral areas (OECD, 2019d). The company car tax is based on engine capacity, so it does not provide an incentive to companies to choose less emitting vehicles for their car fleets.

Transition to green growth requires major investment

Public and private environment-related investment largely relies on EU funds

The public sector is the main driver of environment-related investment. Latvia has significantly benefited from EU funds to finance public investment. Over 2007-20, EU funds allocated to Latvia averaged between 2.5% and 3% of GDP a year. About a third of these funds targeted environment-related investment and helped in extending and upgrading infrastructure for transport, energy, water supply, wastewater treatment and waste disposal (Section 1; Section 4). Nevertheless, considerable investment is still needed to extend and upgrade ageing infrastructure at a time when local governments face pressing resource constraints, and EU funds will eventually diminish.

Business environmental expenditure has declined since the mid-2000s, especially in terms of investment. Over 2005-17, private investment amounted to only 11.5% of total environmental investment in the country. Price signals and financial incentives do not sufficiently encourage private investment. Businesses have an incentive to postpone investment and wait for public funding opportunities. Thus, there is a risk of EU and national funds being used for investment that would have been made anyway, rather than for financing additional, more productive growth-inducing investment. There is a need to reduce dependence on EU funds and streamline the multiple fragmented financial support mechanisms available to encourage environment-related investment.

Improving energy efficiency is a priority

Most of the building stock is over 25 years old and consists of multi-owner buildings with poor energy performance. Since 2007, Latvia has used EU and national funds effectively to upgrade district heating networks and improve buildings’ thermal efficiency. This has contributed to remarkable energy savings, above the EU average (Odyssee-Mure, 2018). However, investment is needed to expand and renovate district heating networks in some municipalities. Heat consumption per square metre is among the highest in Europe, well above that of most other northern European countries. Heat consumption in apartment buildings is generally metered at building level and allocated and charged to households based on apartment size, which provides no incentive for energy savings. The government estimates it would cost EUR 6 billion (more than 20% of GDP) to thermally renovate all apartment building stock.

Hence there is a need to accelerate investment in residential energy efficiency and differentiate the financing sources. Barriers to private investment include the large numbers of owners per building, the fact that many have low income and limited access to bank credit, the long payback and complexity of energy efficiency projects and a lack of energy efficiency specialists and energy service companies. Instruments such as subsidised loans, credit guarantees and energy performance contracts can help overcome some of these barriers.2

More work is also needed to improve energy efficiency in industry. The energy intensity of manufacturing industry is well above the EU average and has increased since the end of the recession. The 2016 Energy Efficiency Law introduced energy saving obligations and laid the groundwork for implementing industrial energy efficiency measures. Consistent price signals are needed, in addition to industrial energy audits, voluntary agreements and financial support.

Latvia needs to diversify its renewables mix

Latvia has made considerable progress in expanding the use of renewables, especially from biomass (fuelwood) in CHP plants (Section 1). However, it needs to expand the use of other renewables, especially solar and wind, to attain its 2020 indicative target of nearly 60% renewables in gross final electricity consumption3 and ensure more sustainable biomass production and use (Section 1; Section 5). The large wind potential has remained largely unexploited in comparison to other Baltic states.

A mix of feed-in tariffs and capacity payments helped increase installed capacity. However, the support system was poorly designed, overly generous and not transparent. It resulted in high costs and windfall profits in some cases (Dreblow et al., 2013; Rubins and Pilvere, 2017). In addition, energy-efficient natural gas CHP plants were eligible for support and attracted much of it. All this triggered changes in the calculation of the support amount, the introduction of a tax on subsidised companies’ profits and, finally, a moratorium until 2020 on the support system, which is being revised. Latvia needs to quickly restore investor confidence and consider more cost-effective and transparent measures to support renewables-based generation, such as competitive tenders and procurement auctions (OECD, 2019d).

Renewables play a negligible role in the transport sector (Section 1). Latvia exports most of its rapeseed-based biodiesel production. Domestic use is low, partly due to the low mandatory blending requirement (4.5% by volume), which covers petrol and diesel sales during the warmer months (mid-April to end-October). An in-depth assessment of the impact of biofuel production and use on net GHG emissions, biodiversity, water and soil is needed. No sustainability criteria are in place beyond those required by the EU. Latvia has not started to produce second-generation biofuels (e.g. from waste, residues).

Integrated transport services can improve environmental outcomes

Most transport-related investment has focused on the road network. While this is needed to improve the network’s low quality and safety (OECD, 2017), Latvia should ensure transport investment priorities are consistent with long-term climate and environmental objectives. Latvia has the longest railway network in the Baltic states. It is largely not electrified and most trains run on diesel. In 2018, the government launched a major railway electrification project to be completed by 2030. Rail is the main freight transport mode but has a marginal role in passenger transport.

Cars account for the vast majority of passenger travel in Latvia. Bus and rail services incur high costs serving sparsely populated areas. The public transport network is dense in the Riga city centre, but becomes thin towards the borders of the city (Yatskiv and Budilovich, 2017). There is no integrated public transport system linking Riga to its sprawling surroundings, and congestion and pollution around the city have increased. There is a need for co‑ordinated planning of transport infrastructure, public transport and urban development. Integrated route planning, pricing and ticketing across providers and municipalities would help increase public transport use. Latvia also needs to further extend the charging facility network for electric vehicles, with a view to expanding their use. The number of such vehicles has increased, but they are still just 0.1% of the fleet, compared with the EU-wide rate of 1.5%.

The environmental technology, goods and services sector shows signs of dynamism

Eco-innovation is promising despite generally low innovation capacity

Latvia’s innovation system and performance are generally modest (OECD, 2019d). The country has a low rate of both private and public research and development (R&D) investment; the state budget and EU funds are the main sources of R&D funding; and co‑operation between industry and public research is weak. The generally low innovation capacity of companies, the shortage of highly skilled workers and the small number and size of companies active in environmental technology hinder eco-innovation (EC, 2019).

Nonetheless, with increased public R&D funding, Latvia has developed a specialisation in environmental technology in recent years. It spends nearly 10% of the government R&D budget on environment- and energy-related research, putting it among the top ten OECD countries despite the context of an inadequate overall R&D budget. Patent applications for environment-related technology reached 13% of all patent applications in 2013-15, although the absolute number remains extremely modest.

Higher demand is needed to expand the markets for cleaner goods and services

The environmental goods and services sector had grown to nearly 3% of GDP by 2015. Renewables, energy efficiency in buildings, forest-based industry, eco-cosmetics and water management are the most dynamic sectors. Compared with the EU average, however, Latvia’s businesses have a lower propensity to produce greener products and invest in goods and services that would improve their environmental performance. Only 13 products produced in Latvia have been awarded the EU ecolabel. Low demand for cleaner products and services is the main barrier to developing these markets. Product price is the dominant driver of consumer choice (EC, 2017a). More efforts are needed to stimulate demand for greener products and services, e.g. through green public procurement, ecolabelling, market incentives, awareness raising and better enforcement (Section 2). Green public procurement accounted for 18% of total public procurement value in 2018, not far from the modest target of 20% by 2020.

Latvia is a good international player, but its development aid is low

Latvia has a strong tradition of international, regional and bilateral co‑operation in the environment field, especially to address regional issues related to the Baltic Sea. Since 2004, when it joined the EU, Latvia has substantially increased the volume of its official development assistance (ODA), mainly through to contributions to the EU budget and the European Development Fund. However, at 0.11% of gross national income (GNI), Latvia’s ODA/GNI is among the lowest in the OECD and falls below the target of 0.33% of GNI by 2030 for countries that have joined the EU since 2002. Bilateral ODA commitments for general environmental protection, renewables and water represent only 0.2% of ODA (sectoral allocable aid), the lowest share in the OECD. Latvia should consider increasing its aid programme, particularly bilateral and environment-related ODA activities, in line with the 2030 EU target and other international goals, and taking into account its areas of expertise. Joining the OECD Development Assistance Committee would help Latvia improve the effectiveness, visibility and coherence of its development assistance activities.

Box 3. Recommendations on green growth

Strengthening the strategic framework for sustainable development and green growth

Better align the post-2020 NDP, and sectoral policies at large, with environmental and green growth objectives; consider extending the 2030 horizon of development planning to 2050.

Greening the system of taxes, charges and subsidies

Implement a green tax reform to provide stronger incentives for sustainable resource use, increase overall tax revenue and reduce the tax burden on low-income households:

Continue to reduce tax exemptions and discounts (e.g. on rapeseed biodiesel, as well as on fuels used for agriculture, fishing, electricity, heating and industry production).

Further raise energy tax rates and close the petrol/diesel tax gap to adequately reflect environmental damage from energy use, while providing targeted support to vulnerable groups through social benefits not linked to energy consumption.

Consider raising the natural resource tax rates on air pollutants on the basis of a cost-effectiveness assessment.

Gradually raise the carbon tax rate; remove its exemption on emissions from peat combustion; consider extending the carbon tax to transport fuels and biomass.

Revise the vehicle tax to take into account air pollutants in addition to CO2; reform the tax treatment of personal use of company cars and link the company car tax to vehicle emission standards and fuel economy; link taxation of heavy goods vehicles to their environmental performance.

Link road tolls for commercial vehicles to distance travelled, in addition to vehicle emission standards; introduce similar road charges for passenger cars.

Build on the annual review of the tax exemptions’ fiscal impact to establish a systematic review process on environmentally harmful subsidies.

Investing in low-carbon infrastructure

Increase and enhance cost-effectiveness of public spending on environment-related infrastructure; streamline and better target financial support for business environmental investment.

Continue to improve residential energy efficiency by i) further scaling up public finance for energy efficiency renovation of buildings; ii) encouraging the use of energy performance contracts, subsidised loans and credit guarantees to foster private investment; iii) investing in training energy efficiency specialists; iv) assisting homeowner associations in the design and management of energy efficiency projects; v) accelerating retrofitting investment on the public building stock; vi) upgrading district heating networks; and vii) extending heat metering and charging heat based on actual use.

Review the design of the renewables support system at the earliest opportunity and consider introducing competitive tendering to improve cost-effectiveness.

Establish an integrated public transport system, with comprehensive route planning, pricing and ticketing, linking Riga to surrounding municipalities; promote transport-on-demand systems to provide public transport services in low populated rural areas; continue to extend the charging facility network for electric vehicles.

Promoting eco-innovation and green markets

Further increase public R&D funding for environment-related innovation and monitor the efficiency and effectiveness of its allocation; strengthen measures to stimulate demand for energy efficient and cleaner products, technologies and services, including green public procurement, eco-labelling, market incentives, awareness raising and better enforcement.

4. Waste management and circular economy

Latvia completely reconstructed its waste management systems in the 2000s. Today it has fairly complete policy and legal frameworks for waste management, supported by quantitative targets and economic instruments. As in other environmental policy areas, most developments are driven by EU requirements and supported by EU funding. The country has increased recovery and decreased landfilling. Progress has been made with separate collection and recovery of municipal waste, recycling capacity and the use of economic instruments to encourage recovery and divert waste from landfills.

However, waste is not yet managed cost-effectively, and related policy implementation is insufficiently co‑ordinated and monitored. The economic instruments used do not provide strong enough incentives for moving towards a circular economy; some targets will be difficult to meet. Waste reduction and prevention and the management of specific waste streams, such as construction and demolition waste, have received little attention.

To lay the groundwork for circular economy approaches, it is essential to improve waste management, including separate collection and sorting; strengthen the use of economic instruments; and improve the economic performance and transparency of extended producer responsibility systems. The potential for progress is good with encouraging recent developments. However, the country needs to plan for reducing its reliance on EU funding, better use synergies with eco-innovation and public procurement programmes, and increase co‑operation with neighbouring countries to strengthen recycling markets and efficiently use existing capacity in the region.

There is room for further improving waste management

Material productivity and recovery rates are growing, but remain low

The material productivity of the economy has improved (by 29% since 2005), but remains lower than in many other OECD and EU countries. Latvia generates less than half the economic value per tonne of materials used than the OECD average (Figure 7). The amount of waste recovered and associated recovery rates are rising, but landfilling, though decreasing, still represents more than 20% of all waste generated. Low-value recovery remains common for some waste streams (e.g. construction and demolition waste); recycled feedstocks (e.g. plastics) are often exported for reprocessing and generate little value domestically. Official data on recycling often refer to amounts being prepared for reuse, recycling or recovery; little is known about the types of products that arise from recycling. Many recoverable and recycled materials get lost for the economy.

The recovery rate of municipal waste grew significantly from a very low 5% in 2005 to about 30% in 2016 (Figure 7). Separate collection of municipal waste has been mandatory since 2015 for paper, glass, metal and plastic waste, and will become mandatory for biodegradable waste in 2021. However, collection performance and the quality of subsequent sorting need to be improved. Two systems for separate collection coexist, with insufficient co‑ordination and a risk of duplication: those of municipalities and those of extended producer responsibility organisations. Mixed municipal waste still contains many recoverable and biodegradable materials. The recovery target for municipal waste of 50% by 2020 may thus be difficult to reach (EC, 2019).

Figure 7. Progress on material productivity and waste recovery needs to be consolidated

Waste is increasingly diverted from landfills, but recycling markets remain weak

Latvia has invested in the development of its recycling infrastructure, and is well placed as regards recycling of paper, cardboard and polymers. In recent years, the focus has been on production of biogas and compost from waste, with a view to diverting waste from landfills and contributing to renewables targets. The establishment of domestic waste-to-energy capacity is also being considered as a way to achieve EU landfilling reduction targets. Given the significant investment involved in such infrastructure and the need to avoid a lock-in effect, it is important the long-term costs and benefits of alternative waste technology and infrastructure be carefully assessed, in line with the waste hierarchy. More attention needs to be given to markets for recycled products, which remain weak and suffer from mistrust of the quality of recycled goods (e.g. compost) and from insufficient investment in domestic high-value recycling. Greater use of synergies within the Baltic Sea region and other neighbouring countries will be instrumental.

Waste prevention in the business sector and measures further upstream the value chain are not well monitored

Little is known about specific waste prevention efforts in production processes and further upstream in the value chain (design phases), and about measures to minimise the environmental impact of waste and materials over their life cycle. Awareness among businesses about the benefits of waste prevention and a circular economy seems low, but promising developments are taking place in eco-innovation and technology development (e.g. competence centres, technology clusters under the Ministry of Economy) (EC, 2017a). Innovation policies and support measures to businesses should fully take into account the objectives of closing material loops, preventing waste generation and establishing circular business models. Doing so could drive growth in sectors that contribute to the transformation of the Latvian economy.

Institutional co‑operation could be strengthened

Encouraging life-cycle-based management and circular economy approaches will have to be on a par with effective alignment of measures and objectives across policies and ministries. At the national level, co‑operation between the MEPRD and other ministries works well for issues related to traditional waste management and development of bioenergy projects. But practical co‑operation on eco-innovation and new technology is not yet well established, and synergies between measures promoted by the MEPRD and the Ministry of Economy are not yet exploited. This hampers the implementation of waste prevention measures and the uptake of new technology and innovation in production processes. To steer the transition to a circular economy and guide related investment choices, Latvia needs to further broaden co‑operation across ministries and with stakeholders, and consider establishing a dedicated institutional platform.

At the local level, waste management regions and municipalities are given flexibility in managing waste, but this leads to implementation gaps and incomplete monitoring. Regional and local waste management plans are no longer mandatory. There is no mechanism for cascading national waste targets to the local level and for monitoring local performance in this respect. Many municipalities lack the capacity to implement new policies and targets. They need more support and harmonised guidance by the government to carry out their responsibilities.

Stronger incentives are needed to move towards a circular economy

Economic instruments are well established…

The use of economic instruments is well established, including a differentiated natural resource tax that applies to material extraction, landfilling, and products for which special end-of-life management objectives have been set; municipal waste fees; and extended producer responsibility systems. The natural resource tax and exemptions from it helped encourage businesses to join extended producer responsibility programmes, achieve several related EU targets and stimulate adoption of reusable packaging. These systems are complemented with a deposit-refund system for certain types of beverage packaging, with plans to make its use compulsory.

…but incentives to move towards a more circular economy remain insufficient

The instruments in place do not yet create sufficient incentives to comply with the waste hierarchy and move towards a more circular economy. Despite recent and planned increases, landfill tariffs will remain below the EU average until 2020 – too low to incentivise recycling and spur investment in alternative waste technology. Municipal waste fee levels are still too low to cover service provision costs and encourage households to reduce unsorted mixed waste. Little use is made of pay–as-you-throw (PAYT) systems for mixed household waste collection, though a pilot is being conducted in one city (Jūrmala). The application of PAYT systems in major cities should be encouraged; it could become an important tool for reducing waste going to final disposal, associated with well‑functioning separate collection of recyclables. More attention should be given to measures that influence consumer behaviour and product design. Most existing instruments target the extraction and post-consumption phases of the value chain.

Extended producer responsibility systems lack transparency and their economic performance is not well monitored

Several of Latvia’s extended producer responsibility systems lack transparency and their activities are not well co‑ordinated. Strengthened controls in 2017 revealed many deficiencies concerning their operation and compliance with recycling targets. Little is known about their financing, cost recovery and economic performance; the data reported annually by producer responsibility organisations are often incomplete and of insufficient quality. A clearinghouse mechanism would help establish a level playing field for all extended producer responsibility systems and make it easier to assess their economic performance. It would also help streamline and consolidate extended producer responsibility for products for which existing systems are scattered or not yet reaching the recycling targets (e.g. electrical and electronic equipment) (OECD, 2016b). Significant efficiency gains could be obtained by ensuring proper co‑ordination of service provision and cost sharing with municipalities, and by fully integrating the waste collection systems managed by extended producer responsibility companies and those set up by municipalities.

Better information on waste and materials is needed to support decision making

Latvia regularly produces statistics on waste generation and treatment, and macro-level material flow accounts. But reporting obligations do not cover all information needed for effective policy making, and data quality varies. Latvia should improve its information base by further harmonising and integrating data, ensuring better coverage of all management steps and treatment routes, and filling gaps as regards data on specific waste streams, recycling efforts in the business sector, extended producer responsibility systems’ performance, waste movements, and reuse and repair activities.

Box 4. Recommendations on waste management and circular economy

Improving the effectiveness and governance of waste management

Review the taxation of waste management in line with the waste hierarchy: Further increase the natural resource tax for landfilling beyond 2020; encourage municipalities to increase municipal waste fees to ensure full cost recovery of service provision; apply PAYT systems in major cities to provide greater incentives to households to participate in separate collection; implement measures to change consumer behaviour and product design.

Merge the separate collection programmes operated through extended producer responsibility systems and those operated by or for municipalities to improve the cost-effectiveness of these systems and the quality of the covered materials.

Specify the requirements for extended producer responsibility systems (calculation of fees, eco-design, recycling objectives, arrangements for service provision and cost-sharing with local authorities, reporting obligations, including on financial aspects) to improve their cost-effectiveness, transparency and co‑ordination; increase resources for compliance monitoring and quality assurance; consider establishing a clearinghouse mechanism to assist in these tasks.

Ensure that national waste policies and targets are cascaded at local level, including through systematic establishment of regional and local waste management plans and regular reporting on results, including on financial aspects.

Exploit synergies with neighbouring countries to efficiently use waste treatment capacities in line with the waste hierarchy and to ensure adequate co‑ordination of deposit-refund systems.

Promoting waste prevention and circular business models

Improve the material productivity and efficiency of the economy and encourage waste prevention in industry and upstream in the value chain (design phase); fully integrate the objectives of closing material loops and preventing waste generation into innovation policies; exploit synergies between measures on cleaner production, eco-innovation, waste prevention, bioenergy and smart specialisation by establishing effective mechanisms for co‑ordinating and monitoring the actions of all ministries involved.

Strengthen markets for secondary raw materials and recycled goods through public procurement and increased co‑operation with neighbouring countries; encourage investment in high-value domestic recycling.

Broaden institutional co‑operation to steer the transition to a circular economy and related investment choices, and deepen co‑operation between the MEPRD and the Ministry of Economy.

Improving the information basis on waste and materials

Improve and expand national waste management information and official statistics on waste and materials; create a consolidated, transparent and integrated system that covers all management steps and treatment routes, including transboundary movements, and that supports the development, implementation and monitoring of national policies, along with international reporting.

5. Biodiversity conservation and sustainable use

Biodiversity pressures are expected to increase with economic growth

Latvia’s forests, grasslands, and coastal and marine areas are home to species of international significance, such as lesser spotted eagle, black stork, lynx and wolf. The conservation status of habitats and species is mostly unfavorable and has been declining. Forest and grassland habitats have worse conservation status than other habitats. Only around 10% of habitats and one-third of species have favourable conservation status (EC, 2017a). Threatened species account for 2% of known species, with amphibians and reptiles being the most vulnerable.

Greater effort to improve biodiversity is urgently required, in light of rising pressures. Sustained economic growth and reliance on forestry, agriculture and fisheries are expected to increasingly affect biodiversity. Nutrient pollution in the Baltic Sea has serious consequences for marine habitats and species. Effectively managing protected areas and better mainstreaming biodiversity considerations in other sectoral policies are key to addressing the drivers of biodiversity loss.

The legal framework is in line with EU requirements but a biodiversity strategy is needed

Latvian biodiversity policy is mostly governed by EU legislation, particularly the Habitats and Birds Directives. The establishment of Natura 2000 raised the profile of biodiversity conservation, along with the special procedure for assessing the potential impact of projects in Natura 2000 sites. Implementing the EU acquis has brought Latvia closer to fulfilling its international commitments, such as those under the Convention on Biological Diversity and the SDGs. Latvia is an active international player and co-operates bilaterally with countries in the region on protected area management and awareness-raising initiatives.

Latvia is one of the few OECD countries lacking a national biodiversity strategy. It has strategies and plans that include biodiversity objectives, but they do not amount to a coherent framework. The 2014-20 Environmental Policy Strategy sets the main biodiversity goals, primarily aimed at fulfilling EU requirements. As the baseline of targets shows a modest starting point for biodiversity conservation activities, the established objectives can be considered relatively far reaching. A long-term vision for biodiversity would need to scale up targets, e.g. developing additional management plans for protected areas to meet the relevant national target.

The MEPRD is responsible for the design and implementation of biodiversity policy. The Nature Conservation Agency is responsible for protected area management, control of international trade in endangered species, and granting compensations. Forestry, fisheries and agriculture are within the purview of the Ministry of Agriculture. There are some co‑operation mechanisms between the two ministries, especially on fisheries, but overall co‑ordination could be strengthened. Human and financial resources represent an obstacle in advancing biodiversity goals.

Latvia needs a comprehensive national approach to biodiversity monitoring

Despite the lack of a comprehensive national approach to mapping and assessing ecosystems and their services, there are ad hoc projects that should help address data gaps and improve biodiversity knowledge.

Latvia has undertaken an assessment of its marine ecosystems and is mapping terrestrial ones. It implemented the EU Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services initiative for marine waters in 2016, under the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020. The assessment mapped areas of high ecological value, although more data is needed to complete the process (BISE, 2016). Latvia’s marine strategy lacks definitions of key biodiversity pressures (e.g. contaminants, marine litter) (Milieu, 2018).

The policy mix is biased towards regulatory instruments

Protected areas are the main measure

As in most OECD countries, protected areas are the main biodiversity conservation tool. Protected terrestrial areas called Specially Protected Nature Territories (SPNTs) represent 18.2% of total land, while protected marine and coastal areas represent 16.4%, surpassing the corresponding 2020 Aichi targets (Figure 8). Since EU accession in 2004, protected areas have increased and almost correspond to Natura 2000 sites. The latest EU assessments show insufficient designation of terrestrial Sites of Community Importance under the Habitats Directive (EC, 2019). With less than 40% of protected areas having a management plan in place, and most suffering from chronic lack of human and financial resources, stronger efforts are needed to improve the conservation status of terrestrial habitats and species (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Current protection efforts are not sufficient to reverse biodiversity loss

Other regulatory instruments used to conserve wild fauna and flora include exploitation bans on certain species, hunting and fishing restrictions, and measures to control artificial propagation of certain plants (Pierhuroviča and Grantiņš, 2017). There have been few green infrastructure initiatives and further efforts are needed to increase connectivity between habitats (EC, 2018).

EIA, strategic environmental assessment (SEA) and spatial planning are cross-sectoral tools used to prevent biodiversity loss. Natura 2000 sites have specific EIA requirements, and SEA is performed for all planning documents with expected significant impact. The Sustainable Development Strategy until 2030 states that the government should introduce a plan for the preservation and restoration of natural capital, which would also include spatial planning of nature preservation and restoration.

Economic instruments can be expanded

The main economic instrument for conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity is compensation to private owners for restriction of economic activities in SPNTs, a form of payment for ecosystem services. Compensation is co-financed by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development, which covers Natura 2000 payments for agricultural and forest land. In addition, there are payments for maintaining biodiversity on grasslands and preserving genetic resources of farm animals (MEPRD, 2014).

Other economic instruments are tax exemptions for private owners within certain areas of SPNTs, a tax on resource use for commercial activities, licence fees for fishing and hunting, non-compliance fees related to forestry use, fishing and hunting, and liability charges for damage to biodiversity.

Over 2008-18, public support was the main source of funding, which heavily relies on EU contributions. Project-based funding is provided by national funds, such as the Forestry Development Fund, the Latvian Environmental Protection Fund and the Fishery Fund; resources for the latter two have increased since 2008, despite some decrease during the economic crisis of 2008-09.

Mainstreaming biodiversity into economic sectors is an opportunity to balance trade-offs

Biodiversity and ecosystem services underpin key sectors outside the purview of the MEPRD, such as forestry, fisheries and agriculture. As in most OECD countries, there is a need to better mainstream biodiversity into national objectives of other economic sectors, especially in light of expected economic growth.

Forestry needs to better integrate biodiversity considerations

Around half of Latvia’s territory is covered by forests, mostly natural. The proportion of primary forests remained stable over the last decade and accounts for 0.5% of total forest area, more than in many other European countries. Forests are an important economic resource: exports of forestry-related products account for 6.5% of GDP, the highest share in the OECD.

All forest habitats of EU importance have bad conservation status. Protected forests represent 17.5% of total forests (MEPRD, 2014). Management consists of restrictions on economic activities in around 14% of forests (including outside protected areas), with around 3% of forests under strict protection. Outside protected areas, additional nature protection involves sustainable management certification, which covers about half of forests (Pierhuroviča and Grantiņš, 2017). To ensure sustainable forest management a policy vision to 2050 is needed, fully integrating biodiversity-related objectives and supported by sufficient resources.

Fisheries, agriculture and tourism exacerbate biodiversity pressures

Latvia has a strong fishery tradition, reflecting its geographical position. The main pressures on biodiversity are by-catch (fish unintentionally caught by commercial nets) and invasive alien species. Latvian fishing quotas have declined over the last decade and are used in full.

Agricultural land covers 31% of the territory. It consists of 65% arable land and 35% pastures and meadows, with a negligible share of grasslands, which are rich in biodiversity. Unlike in other European countries, the nitrogen surplus4 has increased since the early 2000s, and could grow further with the expected intensification of agricultural activity. Organic farming increased to 13.5% in 2017 from 6.8% in 2005; the share is among the highest in the EU. Latvia surpassed its national 2020 target and is on track to meet the 2030 target of 15%.

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) provides direct payments to farmers, who are supposed to respect certain environmental requirements. However, producers benefit from credit subsidies (OECD, 2019a) and relief on diesel fuel excise tax (Section 3). Support is also based on animal numbers and production volumes, thus negatively affecting the environment by favouring more intensive practices. Payments per hectare of grass rather than per animal could be a first step towards greening the sector. Credit subsidies could be used for investment in more sustainable and environment-friendly production methods.