The Assessment and Recommendations present the main findings of the OECD Environmental Performance Review of the United Kingdom. They identify 26 recommendations to help the country make further progress towards its environmental objectives and international commitments. The OECD Working Party on Environmental Performance discussed and approved the Assessment and Recommendations at its meeting on 15 February 2022.

OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: United Kingdom 2022

Assessment and recommendations

Abstract

1. Towards green growth

Addressing environmental challenges at the time of EU exit and COVID-19

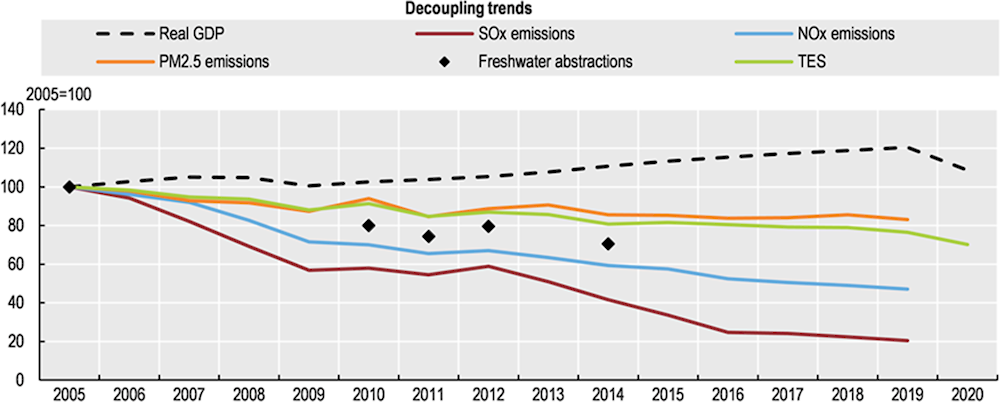

Over the past decade, progress has been made across the United Kingdom in decoupling several environmental pressures from economic growth. These pressures include greenhouse gases (GHGs) and air pollutant emissions; municipal waste generation; energy and material consumption; and water abstractions (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 5). At the same time, the United Kingdom has improved wastewater treatment and expanded the network of protected areas (Figure 3). However, air pollution remains a health concern (PHE, 2019). Agricultural management, climate change and infrastructure development continue to put pressure on the natural environment, causing habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation (Hayhow et al., 2019). Further efforts are needed to achieve net zero GHG emissions by 2050, address the growing risks of climate change, reverse the loss of biodiversity and ensure a more resource-efficient circular economy.

The UK government has devoted a great deal of time and effort to ensuring EU environmental law was adequately retained in the national legislation after exit from the European Union (EU exit) on 31 January 2020. The Environment Act 2021 lays out a domestic framework for environmental governance post-EU exit (most provisions apply to England only). It puts environmental principles1 into law; introduces legally binding long-term targets on air quality, water, biodiversity, resource efficiency and waste reduction; and establishes a new Office for Environmental Protection (OEP). The implementation of the Act, the setting of targets and operation of the OEP will tell whether the UK government's ambition is commensurate with the challenge of protecting and enhancing the environment for future generations.

Figure 1. The United Kingdom has made progress in decoupling several environmental pressures from economic growth

Note: GDP at 2015 prices. TES: Total energy supply.

Source: OECD (2021), Environment Statistics (database).

The United Kingdom has been hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, with the largest gross domestic product (GDP) contraction (-9.7%) in the G7 in 2020 (OECD, 2021a). A fast initial roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines has weakened the link between new COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations and deaths, allowing a broad reopening of the economy. Activity rebounded quickly driven by consumption growth, and GDP is expected to reach its pre-pandemic level at the beginning of 2022. It is estimated that the long-run GDP will be reduced by 4% by the EU exit and a further 2% by the pandemic (OBR, 2021).

The United Kingdom has ambitious climate targets and an economy-wide strategy, setting a path to net zero by 2050

The United Kingdom is at the forefront of global climate action. Ahead of its presidency of the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow, it has led the way by raising its national ambition. In 2019, it was the first G7 country to legislate for net zero GHG emissions by 20502 to deliver on the Paris Agreement, a step up from its previous 80% reduction target. In 2020, it submitted a new Nationally Determined Contribution committing to reduce GHG emissions3 by at least 68% by 2030 from 1990 levels. This is clear progress from the previous commitment of 57%4 and the highest reduction target set by a major economy (Cuming, 2021).

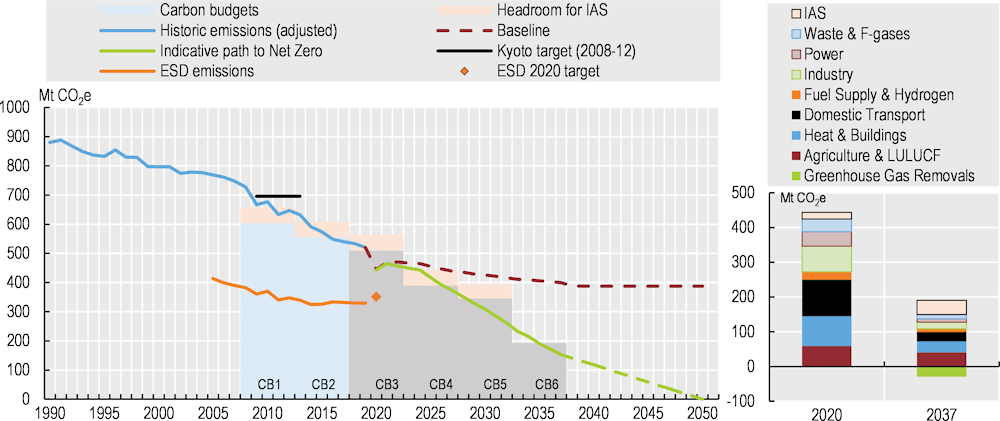

As provided by the 2008 Climate Change Act, the government adopted a Net Zero Strategy (NZS) in October 2021. It builds on the 2020 Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution and sectoral plans, including the 2020 Energy White Paper, the 2021 Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy, Transport Decarbonisation Plan and Hydrogen Strategy, as well as the Heat and Buildings Strategy. The NZS outlines indicative emission reductions by sector to meet the sixth carbon budget (2033-37) and ultimately net zero by 2050 (Figure 2). It calls for fully decarbonising electricity by 2035, subject to security of supply, and rapidly electrifying transport, heating and industry. These actions would be supplemented by low-carbon hydrogen, carbon capture and land-use change (CCC, 2021a). The vision is backed by key milestones sending strong signals to investors and consumers, including 40 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind capacity and 5 GW of hydrogen production capacity by 2030.

UK GHG emission intensities per capita and per GDP (excluding emissions from land use, land-use change and forestry) are low compared to other OECD countries. However, intensity per capita is above the OECD Europe average when emissions embedded in imported goods and services are included. The country has one of the strongest records of emissions reduction in the OECD over 1990‑2019 (44%) (OECD, 2021b). Energy industries have been the largest source of emission reductions, with the shift in electricity generation from coal to gas and, in the past decade, to renewable energy. Progress is slower in other sectors. With the COVID-19 crisis, GHG emissions are estimated to have decreased by 9% in 2020.

The United Kingdom met its first and second carbon budgets (2008-12 and 2013-17) and is on track to meet its third budget (2018-22) (Figure 2). Baseline projections show it would not have reached the fourth and fifth budgets (2023-27; 2028-32) set to achieve the 80% reduction target with policies in place until mid-2019. As of mid-2021, before the NZS was adopted, only 20% of emissions savings for the sixth budget, which sets the path to net zero, had policies “potentially on track” for full delivery (CCC, 2021b). The NZS put forward credible policy proposals to put the United Kingdom on track to net zero (CCC, 2021a). However, it is not yet clear how the NZS will deliver on this ambition. The impact of individual measures is not quantified and some, notably in the agriculture and building sectors, remain to be developed. The government will report on its progress annually. This will provide valuable input to the OECD International Programme for Action on Climate, in which the United Kingdom is actively involved.

Figure 2. Policies must be implemented quickly to put the United Kingdom on a net zero path

Note: The sixth carbon budget (CB6) includes international aviation and shipping emissions (IAS), but the previous ones do not. Historic emissions are adjusted for accounting changes, including wetlands brought in under the 2019 inventory and IAS emissions; and converting the projections into Global Warming Potential values with climate-carbon feedbacks of the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. The Kyoto target should be compared to lower emissions. Baseline: based on policies implemented, adopted or planned as of August 2019. ESD: GHG emissions in Effort Sharing Decision sectors (not covered by the Emissions Trading System). LULUCF: land use, land-use change and forestry.

Source: (BEIS, 2021), Net Zero Strategy-charts and tables; (Eurostat, 2021), Greenhouse gas emissions in ESD sectors.

The United Kingdom is experiencing widespread changes in the climate (CCC, 2021c). Average temperature is around 1.2°C warmer than the pre-industrial period. Meanwhile, UK sea levels have risen by 16 centimetres, and episodes of extreme heat, intense rainfall and associated flooding are becoming more frequent. Continuing sea level rise will increase the risks of flooding and affect coastal infrastructure. The United Kingdom is expected to experience warmer, wetter winters and hotter, drier summers, along with more frequent and intense extremes. Actions have been taken to tackle flooding and water scarcity, but overall progress in planning and delivering adaptation is not keeping up with increasing risk (CCC, 2021c).

Air pollution has been reduced but remains a health concern

Emissions of major air pollutants have declined significantly over recent decades with the shift from coal for domestic heating and power generation and stricter emissions standards and regulations. However, the rate of reduction has slowed down for some pollutants in recent years. In 2019, sulphur oxide (SOx), nitrogen oxides (NOx) and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) emission intensities per capita and per GDP were among the lowest in OECD countries. That same year, the United Kingdom had already met its 2020 reduction targets for SOx, NOx and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs). However, further efforts were needed to meet 2020 targets for reducing ammonia (from agriculture) and PM2.5, as well as to meet 2030 targets for all pollutants except NMVOCs.

Population exposure to PM2.5 has constantly decreased since 2005 but remained in 2019 above the new World Health Organization guideline value5 of 5 microgrammes per cubic metre (µ/m3) (OECD, 2021b). People in Scotland are least exposed to air pollution (6.7 µ/m3), while people in Greater London are exposed to levels twice as high. In 2020, concentrations of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) were lower due to less road traffic as a result of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions. Five zones (out of 43) exceeded the annual mean limit value for NO2, down from 33 in 2019. Urban background ozone pollution has an overall long‑term increasing trend. Air pollution, including from domestic heating and road traffic, continues to be the largest environmental risk to the public’s health. In the United Kingdom, between 28 000 and 36 000 deaths are attributable to human-made air pollution each year.

Natural assets are deteriorating and biodiversity targets have not been met

Most natural assets are deteriorating according to the Natural Capital Committee (NCC), an independent advisory committee that ran from 2012 to 2020 (Table 1.) In 2019, only 16% of surface waters in England met the “good ecological status” standard under the EU Water Framework Directive. However, a higher percentage met this standard in the devolved nations, especially in Scotland6 (Defra, 2021). The most common pressures impacting water bodies are physical modification, and diffuse pollution from agriculture, from wastewater, and from cities and transport. In 2016, the United Kingdom complied with the collection and secondary treatment targets (Articles 3 and 4) of the EU Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive. It was close to achieving the more stringent target (Article 5). However, pollution from sewer overflows is of particular concern (Environment Agency, 2021).

Table 1. Overall assessment of the state of England’s natural capital

|

Natural capital asset |

25 Year Environment Plan goal area |

RAG rating |

|---|---|---|

|

Atmosphere (abiotic) |

Clean air Mitigating and adapting to climate change |

A1 |

|

Freshwater (abiotic) |

Clean and plentiful water |

R |

|

Marine (abiotic) |

Mitigating and adapting to climate change |

R |

|

Soils (abiotic) |

Mitigating and adapting to climate change |

R2 |

|

Biota (biotic) |

Thriving plants and wildlife Enhancing biosecurity |

R3 |

|

Land (terrestrial, freshwater, and coastal margins habitats) (abiotic and biotic) |

Enhancing beauty, heritage and engagement with the natural environment Reducing the risks of harm from environmental hazards Mitigating and adapting to climate change Using resources from nature more sustainably and efficiently |

R |

|

Minerals and resources (abiotic) |

Using resources from nature more sustainably and efficiently Minimising waste |

A |

Note: The RAG rating is based on a trend assessment (historical) and the progress towards compliance with targets and/or other commitments. R (Red) indicates a decline/deterioration; A (Amber) indicates no change, or where the evidence is inconclusive; and G (Green) indicates an improvement.

1) Air pollution has been reduced but levels are still resulting in significant health impacts in some urban areas.

2) Based on limited data that show the condition and extent of soils have deteriorated.

3) Based on the example datasets assessed by the NCC, all show declines in abundance and/or distribution of terrestrial species.

Source: NCC (2020), Final Response to the 25 Year Environment Plan Progress Report.

In 2019, the United Kingdom reported it was on track to meet 5 of the 20 Aichi targets7 of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. These targets comprised mainstreaming, protected areas, implementation of the Nagoya Protocol and National Biodiversity Strategy, and mobilisation of information and research (JNCC, 2019). However, according to the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, most assessments point towards ongoing loss of UK biodiversity, or no recovery from depletion (HoCs, 2021a). Biodiversity indicators show progress in several assessed measures, including agri-environment schemes, reducing air and marine pollution, extending marine protected areas and improving knowledge, but many present mixed or negative trends (Defra, 2021). In particular, the abundance of UK priority species, and common farmland and woodland birds is in long-term decline while pressure from invasive species is increasing. Most UK habitats and species of European importance are in unfavourable condition. The United Kingdom is one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world according to the Natural History Museum (Davis, 2020).

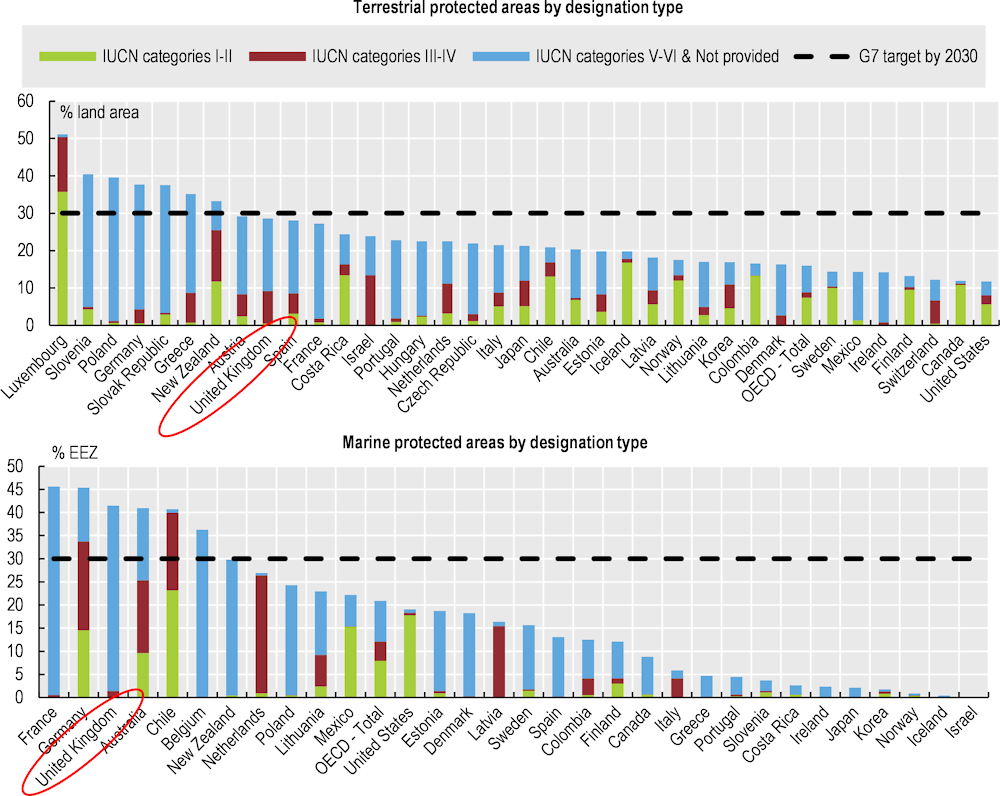

The extent of protected areas has increased significantly since 2015 to cover 29% of land area and 42% of the economic exclusive zone in 2020 (Figure 3). This is well above the Aichi 2020 targets of protecting at least 17% of land and 10% of marine and coastal areas and close to the G7 targets of protecting at least 30% of land and sea by 2030. However, only 0.5% of land area has strict management objectives (International Union for Conservation of Nature management categories8 I and II), compared to 7.4% on average in OECD countries. Only around 5% of UK land is both protected and managed effectively for nature (HoCs, 2021a).

Figure 3. Protected areas coverage is high but terrestrial areas are in unfavourable condition

Note: IUCN categories I-II: Strict Nature Reserves, Wilderness Areas and National Parks; III-IV: Natural Monuments and Habitat & Species Management Areas; V-VI & Not provided: Protected Landscapes and Seascapes, Protected areas with sustainable use of natural resources and areas with no management category provided. The IUCN protected area management categories, classify protected areas according to their management objectives but do not indicate whether protected areas are managed or enforced effectively. IUCN categories are not truly hierarchical; however, sites designated as the “stricter” categories (I-II in particular) are likely to be more restrictive in the sorts of permitted activities. Different approaches are likely explained by varying national priorities but also by factors such as local geography, ecology and pre-existing patterns of human settlement.

Source: OECD (2021), "Environment at a Glance: Biological resources and biodiversity", Environment at a Glance: Indicators.

Improving environmental governance and management

Diverging approaches across devolved jurisdictions require stronger co-ordination

The responsibility for environmental policy and regulation is devolved in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to the Scottish government, the Welsh government and the Northern Ireland Executive. There is no devolved government for England; the UK government makes decisions and proposes legislation that concerns England. Devolution results in tailored policy making and enables administrations to learn from each other’s policies and implementation practices. There is growing divergence between the environmental policy approaches of the four nations. This divergence requires stronger co‑ordination mechanisms between the UK government and devolved administrations (as is the case, for example, on biodiversity protection) to maintain a UK-wide level playing field in the absence of common EU law. A review of intergovernmental relations in 2021 has made changes to the structures and ways of working that will strengthen engagement across the four UK nations.

The institutional capacity of environmental authorities across the United Kingdom has suffered from more than a decade of budget cuts, diversion of resources to address EU exit-related needs and, in the case of Scotland, a major cyberattack in 2020. This has undermined the agencies’ ability to design and implement many cutting-edge policies and practices.

Regulatory and policy evaluation is strong, but environmental assessment could be improved for non-environmental legislation and policies

The United Kingdom continues to emphasise evidence-based policy making. Regulatory and policy evaluation, ex ante and ex post, plays an important role in environmental governance. Strategic environmental assessment is widely used in land-use planning and environment-related policies, less for non-environmental plans and programmes such as regional economic strategies. However, regulatory impact assessment focuses primarily on the regulatory burden on businesses and does not, unlike in several other OECD member countries, identify and address potential environmental impacts of draft regulations (Nesbit, 2019).

The OEP in England and Northern Ireland9 and Environmental Standards Scotland, both created in 2021, are independent bodies to ensure government accountability for implementing environmental policy and law. Wales has appointed an interim assessor to oversee the functioning of environmental law. The United Kingdom has long been a frontrunner in performance measurement, using indicators to gauge both policy implementation and corporate results of environmental authorities.

Good regulatory practices must be preserved

The country has long been a standard setter within the European Union and beyond with regard to good practices in setting, and ensuring compliance with, environmental requirements. These include diversification of permitting regimes based on the regulated activity’s level of environmental impact. General binding rules, registration and notification are used for lower-risk activities, reducing the administrative burden on regulators and regulated businesses.

UK environmental regulators increasingly rely on advice and guidance to promote compliance and green business practices. The promotional tools are tailored to specific activity sectors. Sectoral compliance assurance plans focus on practical ways of delivering environmental, social and economic outcomes. Green practice promotion tools also include incentives for adoption of environmental management systems and public recognition of environmental excellence.

The risk-based approach, together with the emphasis on compliance promotion, has helped UK environmental authorities to improve permit compliance levels over the years. Risk-based planning of environmental inspections in England and Scotland is based on sophisticated tools and protocols that consider, among other factors, the regulated sector, site location and the operator’s compliance record. There are also methodologies, such as England’s Compliance Classification Scheme, to assess and categorise offences to arrive at compliance ratings for individual operators. UK environmental regulators make compliance indicators a key part of their performance management.

Over the last decade, the United Kingdom has emphasised administrative response to non-compliance, as the number of criminal prosecutions has declined steadily. The decriminalisation of less severe violations has made enforcement more proportionate to non-compliance, more expedient and more efficient. Enforcement undertakings have been increasingly used. In these cases, the offender makes a voluntary offer, accepted by the regulator, to restore and remediate the local environment and prevent repeated non-compliance instead of paying a fine. However, the implementation of variable administrative monetary penalties has been slow.

Promoting investment and economic instruments for green growth

Green recovery effort has focused on sustainable transport

The UK’s priority on green recovery is reflected in the 2020 Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution, the 2021 plan to Build Back Better (Plan for Growth), NZS to Build Back Greener and the Fairer, Greener Scotland Programme for Government 2021-22. Since March 2020, the United Kingdom has introduced successive packages of support measures equivalent to 15% of 2020 GDP, one of the largest fiscal responses to the COVID-19 crisis globally (OBR, 2021). As part of this package, green measures are estimated at 1.2% of GDP (OECD, 2021c). Support for public transport services, cycling and walking is prominent. Of the 50 largest economies covered by the Global Recovery observatory, the United Kingdom invested the most on green transport (O’Callaghan and Murdock, 2021). This is a positive step to reverse declining use of public transport resulting from the pandemic while aligning the climate and well-being agendas through active travel promotion. Significant budgets were also announced to promote electric vehicles (EVs), renewables, woodland creation and peat restoration.

However, the early cancellation of the energy saving investment scheme (Green Homes Grant) resulted in few homes upgraded and limited impact on job creation (NAO, 2021a). In addition, some measures of the package ran counter to the climate objectives (e.g. facility loans to car manufacturers and airlines with no environmental conditions). Environment-related measures represent a small share of the COVID-19 response package due to the importance of rescue measures. The UK and Scottish governments aim to further mobilise green private investment and promote green finance through the new UK Infrastructure Bank and the Scottish National Investment Bank.

Environmental goals could be better embedded into public spending…

The United Kingdom has made progress in integrating environmental objectives into departmental plans. The 2021 Autumn Budget and Spending Review outlines the public spending contribution to Net Zero (GBP 26 billion) and other green objectives10 (GBP 4 billion) over 2021-25 (HM Treasury, 2021). However, progress is uneven across departments and the potential negative contribution of programmes is not published. Some countries, such as France, have assessed the environmental impact (positive and negative) of their stimulus packages in budget documents. The United Kingdom could follow the same approach to ensure that public spending is consistent with environmental objectives. The Environment Act exempts taxation, central spending and resource decisions from the application of environmental principles.11 This is intended to ensure the Treasury Minister’s ability to alter the UK’s fiscal position but goes against the recommendation of the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee (HoCs, 2021a).

The United Kingdom has a robust framework for monitoring and evaluating public spending programmes, including a Green Book to appraise the costs and benefits of policies, projects and programmes. The Green Book has been updated to include stronger guidance on establishing clear objectives on climate following an HM Treasury review (2020a); to account for the effects of climate change even where net zero is not the primary objective of a proposal; to embed a natural capital approach in appraisal, and to better value unmonetisable costs and benefits (HM Treasury, 2020a). Natural capital approaches have been adopted across infrastructure sectors and activities. However, challenges remain relating to planning policy and practice and to measurement and valuation of natural capital (NIC, 2021).

…and infrastructure planning

As part of the government objective to increase public investment from 1.9% of GDP to 2.7% by 2025/26, the 2020 National Infrastructure Strategy seeks to boost growth and productivity across the whole of the United Kingdom. To that end, it aims to level up and strengthen the Union, putting it on the path to net zero and supporting private investment (HM Treasury, 2020b). It provides for GBP 27 billion investment in economic infrastructure (transport, energy and digital communications) in 2021/22. Significant investment is planned in rail, including for construction of high speed rail. The 2021 Transport Decarbonisation Plan aims to shift travel from road to rail, public transport and active transport, among other priorities. However, the rail system suffers from poor passenger service performance; fragmentation and lack of accountability; concerns around increasing costs and financial sustainability (HoCs, 2021b). The 2021 Williams-Shapps Plan for Rail was designed to address these issues. There are questions about whether infrastructure programmes sufficiently consider regional disparities and environmental objectives. The Road Investment Strategy (GBP 24 billion investment over 2020-25) does not seem consistent with climate objectives (CCC, 2021b) (Transport for Quality of Life, 2020).

The NZS estimates that additional annual investment must grow to GBP 50-60 billion by 2030 (HM Government, 2021). With operational savings generated through reduced reliance on fossil fuels, the net cost of the net zero transition is estimated at 1-2% of GDP by 2050, depending on sources (CCC, 2020) (HM Government, 2021). The power and buildings sectors are expected to contribute most to investment costs due to the increase in electricity generation and high costs of decarbonising buildings, while vehicles are anticipated to dominate net operating savings. The GBP 26 billion public investment committed for net zero to 2025 appears generous in some areas (e.g. innovation, EV charging infrastructure) but low in others (e.g. heat pumps and heat networks). While contracts for differences are promoting investment in renewables effectively, there are concerns about insufficient funding to stimulate energy efficiency in the least efficient, owner-occupied homes (CCC, 2021a).

The United Kingdom announced new funds for biodiversity, but other financing sources need scaling up

UK public spending on biodiversity fell by more than a quarter over 2010-19. Post-EU exit, new sources of public financial support such as England’s Nature for Climate Fund (GBP 750 million to 2025) are aiming to reverse the trend. Under the 2020 Agricultural Act, environmental land management (ELM) schemes will gradually replace the payments inherited from the EU Common Agricultural Policy in England12. The goal is to shift from supporting income and market prices to paying farmers for the provision of public goods, a welcome step towards market orientation of agricultural production and protection of biodiversity. The United Kingdom has gained valuable experience in testing results-based payments to farmers: pilots have demonstrated better performance to improve biodiversity than current action-based agri-environment measures.

England is pursuing a proactive policy to increase forest cover by allocating 80% of the Nature for Climate Fund to the Trees Action Plan 2021-24. The devolved administrations have also published plans for woodland creation and peatland restoration. The removal of GHGs by forests will be required to achieve net zero. However, more should be done to mobilise private finance to foster woodland creation and their GHG removal, biodiversity and ecosystem services. Beyond measures since 2019 in England to develop a national forest carbon market, the United Kingdom could consider allowing forest carbon credits in compliance markets (UK Emissions Trading System [ETS]), as is done in New Zealand. The Environment Act calls on local authorities to develop local nature recovery strategies in their spatial planning; encourages landowners to sign up, on a voluntary basis, to long-term conservation covenants; and introduces Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) to property developers. These are all steps in the right direction. However, coherence must be sought between these new environmental policy instruments, and between them and public financial support for biodiversity such as the ELM schemes and the Nature Fund for Climate. The United Kingdom could consider taxing building permits in combination with the future land offset market (as part of the BNG policy) to ensure a floor price to the market.

Carbon prices send inconsistent signals across sectors and fuels

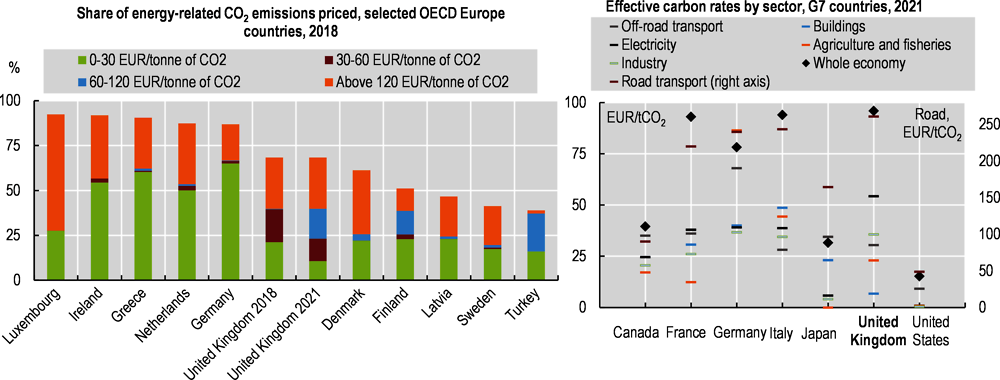

Carbon emissions are priced through the UK ETS, which replaced the EU ETS in 2021, fuel duties and a climate change levy (that is not based on fuels’ carbon content). In addition, since 2013, a carbon price floor taxes fossil fuels used in electricity generation via carbon price support (CPS) rates on top of the ETS allowances price. The increase in CPS rates has helped drastically reduce the share of coal in electricity generation. Compared with other OECD European countries, effective carbon rates13 are high in the road and electricity sectors but low in others, especially in the residential and commercial sector (Figure 4). In 2021, only 45% of carbon emissions from energy use were priced above EUR 60 per tonne of CO2, the midpoint benchmark for carbon costs in 2020.

Figure 4. Carbon prices vary by sector and fuel

Note: Includes emissions from the combustion of biomass. Left panel: Top 5 and bottom 5 OECD Europe countries. Price levels have increased in EU countries in 2021 due to the significant increase in EU ETS prices. This increase is not reflected in the left panel.

Source: OECD (2021), Carbon pricing in times of COVID-19: What has changed in G20 economies? OECD (2021), "Effective carbon rates", OECD Environment Statistics (database).

The complex system of explicit (ETS, CPS) and implicit (climate change levy, fuel duty and different tax treatments) carbon prices14 sends inconsistent signals across sectors and fuels. It does not reflect the environmental damages from energy use. For example, while electricity consumption is subject to a carbon price under the ETS and the CPS, gas consumption faces no or low carbon prices. In addition, the cost of support to renewables (such as the renewables obligation and contracts for difference) is passed through to consumers. This increases electricity bills and provides an incentive to use gas rather than electricity. The United Kingdom is one of the few OECD members to tax diesel and petrol at the same nominal rate. This is positive as diesel has higher carbon content than petrol, and diesel engines generally generate higher local air pollution cost. However, fuel duties have been frozen since 2011, reducing the incentive to shift to public and active transport and to EVs.

NZS commits to implement a net zero consistent trajectory for the annual ETS cap and to explore expanding the system to sectors that are not subject to an explicit carbon price, as planned by the European Union. It also pledges to rebalancing policy costs from electricity to gas bills to ensure that heat pumps are no more expensive to buy and run than gas boilers. However, the government has yet to clarify the role of taxes in achieving UK targets. The exchequer departments have limited understanding of their environmental impact (NAO, 2021b). Recent decisions on taxation (e.g. renewed freeze of fuel duty and vehicle excise duty for heavy goods vehicles (HGVs), suspension of the HGV road user levy, reduced rate for air passenger duty for domestic flights) run counter to climate objectives.

Road pricing will be needed to address transport externalities and loss of fuel tax revenue

Since the first year vehicle excise duty (VED) was based on CO2 emissions (2001), the number of diesel cars has almost tripled. The 2017 reform reversed this trend by introducing a criterion on NOx emissions in VED. However, average CO2 emissions per kilometre of new cars have risen over 2016-19, due to the rising share of larger vehicles. After a new car has spent a year on the road, VED is charged at a flat rate. This reduces the incentive to choose low-polluting second-hand vehicles, although EVs are exempt from VED. The government ran a Call for Evidence on increasing VED for more polluting vehicles and greening VED after first registration. Sales of ultra-low emission vehicles15 have recently increased but only accounted for 10% of new car registrations in 2020. As in other OECD countries, the United Kingdom encourages the use of passenger cars through favourable company car tax taxation, which is not justified on environmental or equity grounds. By contrast, the cycle to work scheme16 has successfully supported biking and could be further promoted for low income, self-employed workers and employees of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

As EVs develop, road pricing will be needed to address transport externalities and loss of fuel duty revenue. The London low emission and ultra-low emission zones and congestion charge have reduced congestion and air pollution effectively, although more needs to be done. Bath, Birmingham and Portsmouth have introduced Clean Air Zones that charge entry to the most polluting vehicles. However, private cars are not always charged. Since 2014, there has been a road user levy for heavy goods vehicles using UK roads. However, in practice, only non-UK hauliers pay the charge as UK hauliers receive an equivalent reduction in their VED (Butcher and Davies, 2020). The levy has been based on weight, number of axles and Euro emissions standards since 2019. It was suspended from August 2020 to help the haulage industry recover from the effects of COVID-19. There has been some discussion over the years about introducing a network-wide road pricing system, which would make differential charges based on time and distance travelled. However, it has never been implemented.

Support measures with potential environmentally harmful impact should be tracked

In 2020, the UK government announced an end to support for fossil fuel projects overseas. According to the official definition, the United Kingdom has no fossil fuel subsidies. However, the National Audit Office and OECD Inventory report large tax reliefs supporting fossil fuel consumption. These include reduced rate of value added tax (VAT) on supply of domestic fuel and power; VAT exemption of domestic passenger transport; fuel duty not charged on kerosene used as heating fuel; and reduced rate on diesel used in off-road vehicles (NAO, 2021b). Other measures encourage oil and gas investment in the United Kingdom. The “Ring-fence” corporate income tax enables a 100% first year allowances for capital expenditure by the oil and gas sector. In addition, operators can fully deduct decommissioning costs from their corporate profits in the year in which they are incurred. In November 2021, Wales joined the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance, which seeks an end to oil and gas production. The current agricultural policy mix supports farm holdings through decoupled payments and payments that promote environmentally friendly practices. At the same time, market measures and tax rebates on diesel incentivise output and may encourage environmentally harmful practices. Contrary to some other G7 countries, the United Kingdom is not tracking support measures with potential environmentally harmful impact.

Recommendations on green growth

Addressing environmental challenges

Use the legislation, including the Environment Act, to set ambitious quantitative interim and long‑term targets on air quality, biodiversity, water (including marine), waste reduction and resource efficiency and develop plans for achieving them to operationalise the goal of leaving the environment in a better state within a generation.

Swiftly implement the Net Zero and related sectoral strategies, and ensure that resources allocated are in line with the needs identified; detail the expected mitigation impact of measures adopted and planned.

Further mainstream biodiversity in land use: accelerate the transition from practice-based payments to farmers to results-based payments; strengthen market-based incentives for carbon sequestration as a means of leveraging private finance for forests and their biodiversity; combine public financial support and the land offset market to direct the net gain in biodiversity towards land with high biodiversity value; consider combining the taxation of building permits with the land offset market to ensure a floor price on the market.

Improving environmental governance and management

Strengthen co-ordination and peer learning between environmental authorities of the four UK nations in setting and implementing environmental policies and laws.

Secure human and financial resources necessary to maintain and further develop the good regulatory practices in permitting and compliance assurance.

Reinforce the environmental aspects of regulatory impact assessment; expand the application of strategic environmental assessment to non-environmental policies, plans and programmes.

Accelerate implementation of variable administrative monetary penalties; in determining such penalties, put more emphasis on recovering economic benefits of non-compliance.

Promoting investment and economic instruments for green growth

Systematically screen actual or proposed subsidies, including tax provisions to identify those that are not justified on economic, social and environmental grounds and, on the basis of this assessment, develop a plan to phase out fossil fuel and other environmentally harmful subsidies. Clarify the role of taxes in achieving environmental targets.

Pursue efforts to consider environmental impacts (including on the natural environment) in cost‑benefit analysis of public investment and ensure it is systematically considered in decision making. Foster the use of natural capital valuation tools.

Carry on with plans to set a net zero consistent trajectory for the annual cap of the UK ETS and to explore expanding the system to sectors not subject to explicit carbon prices, as part of a broader fiscal reform that addresses potential adverse impacts on households and competitiveness.

Consider how to gradually replace declining fuel duty revenues in the context of the transition to electric vehicles, including looking at policy options such as distance-based charges that may vary with vehicle emissions on national roads, and charge differentiation by place and time in the most congested urban areas. Consider increasing first licence vehicle excise duty for more polluting vehicles and green vehicle excise duty after first registration and abolishing the favourable tax treatment of company cars. Ensure the cycle to work scheme meets its objectives, with consideration of low income, self-employed workers and SME employees.

2. Promoting circular economy

The United Kingdom has decoupled domestic material consumption and municipal waste generation from economic growth

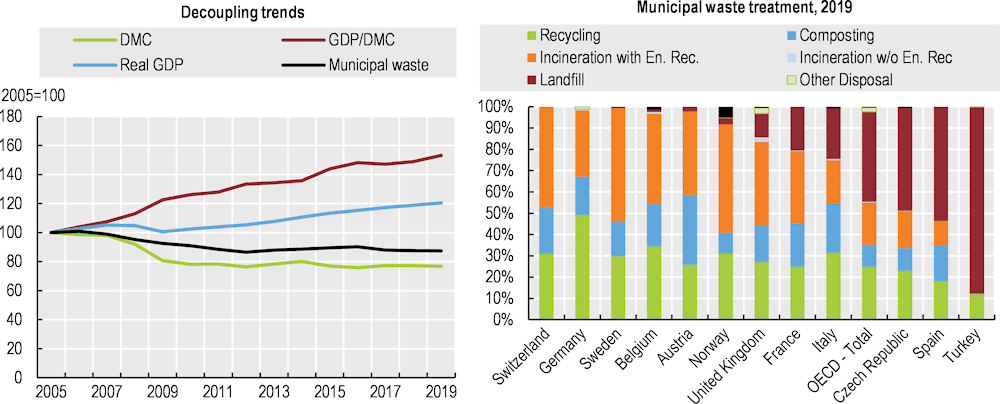

The United Kingdom has a highly service-oriented economy, and its domestic material productivity is the third highest among OECD countries. Domestic materials consumption (DMC), which remained flat from 2010 to 2019, exhibited absolute decoupling from GDP growth, resulting in improved material productivity (Figure 5). Consumption of fossil fuel carriers fell steadily with the shift from coal to renewables. However, there was increased consumption of non-metal minerals (used largely in construction) and of biomass. The UK’s material footprint, which includes materials processed abroad for products consumed domestically, increased over 2010-17.

Municipal waste generation fell between 2005 and 2019, although both GDP and population grew in this period (Figure 5). Municipal waste generation per capita is below both OECD and OECD Europe averages. Some of the decline in municipal waste generation (as well as the comparatively low level per capita) may be due to statistical factors. However, new policy measures and greater public awareness influenced the trend. By contrast, other waste streams grew, notably construction waste, which represented half of all primary waste in 2018. As a result, generation of primary waste increased by 13% from 2010 to 2018.

Figure 5. Material productivity and waste treatment have improved

Note: Real GDP at 2015 prices. DMC refers to the amount of materials directly used in the economy, or the apparent consumption of materials. DMC is computed as domestic extraction used minus exports plus imports. Material productivity designates the amount of GDP generated per unit of materials used (GDP/DMC).

Source: OECD (2021), Environment Statistics (database).

Landfilling of municipal waste fell while incineration increased – and recent policies set out further efforts to strengthen recycling and composting

From 2005 to 2019, the United Kingdom sent a steadily decreasing share of municipal solid waste to landfills, while the share of incineration grew from about 10% to 40% in 2019 (Figure 5). The shares of recycling and composting have grown. However, since 2010, their growth on a UK-wide basis has been slow.

A steadily rising landfill tax played a key role by establishing a strong incentive for these shifts: the current rate (GBP 96.70/tonne) is among the highest in the world. With this economic instrument and further measures to restrict landfilling, the United Kingdom has implemented the recommendations in OECD’s 2002 review to revise landfill-related measures and reduce landfilling. Unlike many other OECD Europe countries, however, the United Kingdom does not have incineration taxes.

In Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, waste plans and strategies early in the past decade called for greater recycling, which has increased steadily along with composting in these devolved nations. In Wales, 65% of household waste was recycled or composted in 2019, meeting the EU’s 2020 target (50%) that has been transposed into legislation for all parts of the United Kingdom. Northern Ireland also met this target, although Scotland did not. Nor did England, where recycling did not increase strongly. In England and Scotland, recycling rates vary greatly across local authorities. The 2020 target was not met for the United Kingdom as a whole.

Local authorities throughout the United Kingdom organise kerbside collection of recyclables and residual waste. About half of local authorities in England collect food waste separately, as do nearly all those in Northern Ireland, reaching almost all households, and all authorities in Wales. In Scotland, local authorities are required to collect food waste separately in urban areas, and some do in rural areas as well. Independent organisations – the Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) and Zero Waste Scotland (ZWS) – have supported waste goals by, among others, advising local authorities and co‑ordinating public awareness campaigns.

Several factors, however, have limited the effectiveness of separate collection. In England, about half of local authorities give households a single bin for all their dry recyclable waste. This must then be separated in sorting plants, which can lead to losses in recyclable material. The types of plastics and other waste that should be separated vary across local authorities (including across the boroughs in Greater London), creating confusion for some households. Moreover, many local authority budgets fell in the first half of the last decade, leading to cuts in their public awareness activities to support separate collection.

The United Kingdom has exported large volumes of refuse-derived fuel for incineration with energy recovery (principally to EU member states) and of waste for recycling. Large volumes of plastic scrap have been exported for recycling to the People’s Republic of China (until its ban on imports), to Southeast Asian countries and to Turkey. While trade can move waste to foreign markets for recycling, there have been cases of improper disposal. The United Kingdom has recently stepped up efforts to tackle illegal waste exports; moreover, the UK government has pledged to end exports of plastic scrap to non-OECD countries.

England’s 2018 Resources and Waste Strategy and its 2021 Waste Management Plan call for major reforms; the 2021 Environment Act establishes a common approach for collection of recyclables in household waste in England, food waste collection in all local authorities, and a UK-wide electronic waste tracking system to inform more targeted action on waste prevention and recycling and to help tackle waste crime, including illegal exports. These policy documents, together with ambitious policies already in place or planned by devolved governments, set the stage for higher levels of recycling and composting in England and across the United Kingdom.

These reforms will need to be designed and implemented carefully to ensure that local authorities receive adequate resources to strengthen waste management. At present, UK local authorities do not directly charge households for waste collection and treatment as council taxes lack a line item for waste management. The United Kingdom should consider promoting, where appropriate, pay-as-you-throw approaches that could link household costs to residual waste levels and thus encourage waste reduction and recycling. This would follow a recommendation in the 2002 OECD Review for waste charges to encourage minimisation of household waste.

Extended producer responsibility (EPR) has supported recycling, but EPR schemes need reform

The United Kingdom has EPR schemes for packaging waste, end-of-life vehicles, batteries and accumulators, and waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE). While most EPR targets have been met, the performance of the EPR schemes has been hindered by several shortcomings: the UK National Audit Office has raised concerns, for example, that packaging waste data are not accurate (the forthcoming electronic waste tracking system is expected to improve data accuracy). Moreover, in this EPR scheme, mechanisms create greater incentives for export of plastic scrap than domestic recycling. EPR schemes do not support local authorities in their collection of packaging recyclables from households.

The UK government and the devolved governments are preparing a series of reforms to strengthen EPR schemes, starting with packaging waste and to establish deposit-refund systems for beverage containers. Reforms for the WEEE scheme will go for consultation in 2022; a proposal for a new EPR scheme for textiles and reforms to the existing EPR scheme for batteries and accumulators are also in preparation. England’s 2018 Resources and Waste Strategy calls for new EPR schemes for bulky household waste such as furniture, certain construction waste streams, vehicle tyres and commercial fishing gear. The United Kingdom and the devolved governments will need to design these reforms carefully to ensure they reduce waste generation and increase waste recycling and reuse. For example, the United Kingdom could explore adapting the forthcoming deposit-refund schemes to promote beverage container reuse.

Despite progress, contaminated sites and illegal waste dumping need further attention

The United Kingdom, birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, has a high number of contaminated sites. However, there are no registers of potentially contaminated land and no common system of assessment. In 2005, it was estimated that 325 000 sites in England and Wales were affected to some degree by contamination. In 2008, 67 000 sites were estimated as contaminated in Scotland.

Local authorities have primary responsibility for identifying contaminated land sites and requiring clean-up if they find unacceptable risks to human health (England’s Environment Agency and its counterparts in the devolved governments take responsibility for special sites). From 2000 to 2013, local authorities inspected just under 39 000 sites in England, Scotland and Wales, about two-thirds of the sites where inspection was considered necessary. Over 2000-18, about 600 sites were determined to have contaminated land in England; of these, almost 500 were undergoing clean-up in 2018. England and the devolved administrations have followed the recommendation in the 2002 OECD Review to implement legislation for remediation of contaminated land. However, progress in the inspection of potentially contaminated sites and in clean-up actions has slowed since 2013. Renewed efforts are needed to increase the pace of site identification and clean-up.

Across the United Kingdom, illegal waste dumping has been an important concern. Just under 1 million incidents on public land were reported in the fiscal year that ended in April 2020. Illegal dumping reportedly increased in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. In England and Scotland, new measures tackle this issue, increasing fines and strengthening local authority powers. In 2020, environment agencies and police forces across the United Kingdom formed a unit for waste crime to address the problem of organised crime groups operating in the waste sector. The United Kingdom has implemented the 2002 OECD recommendation to strengthen measures against illegal disposal; however, further efforts are needed. England’s 2018 Resources and Waste Strategy sets out a range of measures, and the 2021 UK Environment Act strengthens powers against waste crime.

Current initiatives for the circular economy provide a basis for further actions across the United Kingdom

UK policies have set long-term ambitions to improve resource efficiency and move towards a circular economy: England’s 2018 Resources and Waste Strategy, for example, calls for doubling resource efficiency (measured in terms of GDP per DMC) by 2050; Scotland’s 2016 circular economy strategy, Making Things Last, supports zero waste objectives; the 2021 Welsh circular economy strategy, Beyond Recycling, includes zero waste and net zero carbon objectives for 2050.

In 2020, the United Kingdom and the devolved governments jointly published a Circular Economy Package that underlines the benefits of the transition to a circular economy. In 2022, the United Kingdom will introduce an innovative tax on plastic packaging containing less than 30% recycled content.

The UK government is integrating circular economy goals into industrial and economic policies. The NZS includes the transition to the circular economy, and the UK government is exploring opportunities to integrate circular economy into its industrial policy approach. The 2021 Energy-related products policy framework calls for products that can be more easily repaired, remanufactured and recycled, and the UK government is working on a broader products policy that will include circular economy goals. However, the UK’s 2021 Build Back Better Plan contains few references to circular economy goals. Until 2014, a National Industrial Symbiosis Programme sought to strengthen material flows among industrial enterprises, but little information is available on its results.

Local governments, including Glasgow and the Greater London Council, have launched circular economy initiatives, with further measures in preparation. Independent organisations such as the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, WRAP and ZWS have promoted circular economy initiatives in industry. WRAP has brought together industry stakeholders in voluntary agreements to tackle plastic waste, food waste and textiles waste. Signatories of the Sustainable Clothing Action Plan, for example, reduced waste throughout clothing lifecycles by 2.1% between 2012 and 2020.

Current government and private actions provide a strong basis for further work on circular economy and resource efficiency. However, further initiatives will be needed to achieve the UK’s ambitious long-term objectives. In the construction sector, for example, use of materials such as aggregates and other non-metal minerals and the generation of construction and demolition waste rose from 2010 to 2018, in parallel with the sector’s output. This increase occurred despite government policies and actions to increase the sector’s resource productivity.

Further co-ordination will be needed to ensure the effectiveness of waste and circular economy policies

Until EU exit, EU policy and legislation provided a common approach and a driver for waste and circular economy policies across the United Kingdom. Joint Ministerial Committees between the UK government and devolved administrations are used to share information and discuss common issues, and informal contacts among officials have been strong. A sectoral policy board and management group have brought together officials for joint planning on packaging waste reforms. In 2021, the United Kingdom and the devolved governments were preparing a Common Framework for Resources and Waste that should provide a context for formal co‑operation structures. Devolution has allowed the nations to undertake ambitious policy actions in areas where they have powers: one example is the high level of municipal waste recycling achieved in Wales and, in Scotland, the ban on landfilling biodegradable municipal waste from 2025.

Nonetheless, to achieve long-term waste management and circular economy goals and to maintain high policy ambitions, formal co‑operation mechanisms will need to be strengthened, both among the four nations and also among local authorities. In addition, regular reviews and independent evaluations are needed to strengthen policy implementation and development.

Recommendations on waste management and circular economy

Policy ambition, coherence and co-ordination

Continue and strengthen the integration of circular economy policies with industrial and carbon reduction policies.

Consider how promoting greater domestic recycling and reprocessing capacity and increasing industrial symbiosis can support circular economy goals while ensuring greater economic resilience. Strengthen policy goals and initiatives for the repair, reuse and remanufacturing of products while creating local jobs.

Continue development of a UK product design strategy that supports circular economy goals. This could draw on current work in the European Union and other OECD economies for product standards on durability, reuse, repair and recyclability, together with co-ordination with other advanced economies, including via OECD working parties.

Expand resource efficiency goals to incorporate the reduction of the UK's worldwide material footprint.

Strengthen formal and informal mechanisms for co-ordination, peer learning and policy development among environmental authorities of the four UK nations in setting, implementing and evaluating waste management and circular economy policies.

Provide additional funding to support local authorities, catalyse private sector action, and promote innovative waste and circular economy initiatives, including via independent organisations such as WRAP and Zero Waste Scotland.

Policy instruments

Ensure effective implementation of England’s waste management reforms, including the kerbside collection of household food waste and national guidance for separate collection of a core set of recyclable waste streams to reduce co-mingling.

Ensure that local authorities have adequate capacity and resources to put reforms in place and reach minimum recycling rates. Strengthen financing of waste management at local level where needed. Consider the use of pay-as-you-throw mechanisms that can provide incentives for waste reduction, as well as moving to full financing of waste collection and treatment costs via user fees, in line with the polluter pays principle.

Carry out public information campaigns to support successful implementation of the new requirements.

Develop mechanisms to increase resources and capacity for local authorities for the identification and clean-up of contaminated sites to accelerate progress.

Continue and strengthen actions to tackle illegal waste dumping and illegal waste exports, including the introduction of an electronic waste tracking system, and fulfil policy goals to end exports of plastic scrap to non-OECD countries.

Put in place planned reforms to extended producer responsibility schemes to improve the performance of existing systems, extend EPR to new waste streams, and establish co‑operation between EPR schemes and local authorities. Consider options to use the new deposit-refund schemes to promote beverage container reuse and consider opportunities for new deposit-return systems for waste streams with hazardous components such as portable batteries.

Consider further use of economic instruments to promote waste management and circular economy goals, in particular introduction of incineration taxes to provide further incentives for recycling and avoid a “lock-in” of incineration capacity, plus an increase in aggregates tax to encourage further resource efficiency and recycling in construction. After monitoring the results of the plastics tax, to be introduced in 2022, consider the feasibility of increasing the minimum recycled content and of introducing taxes to promote recycled content in other products.

Continue and enhance initiatives for private sector action on circular economy, including support for voluntary agreements, innovative research and co-operation with local authorities and civil society.

Use the UK’s innovative work on measures of the carbon footprint of waste streams and waste treatment to identify opportunities to further reduce the direct and indirect carbon emissions of each economic sector. Develop and implement methods to track the results of circular economy initiatives on domestic materials consumption, material footprint and carbon emissions, including in the construction sector.

References

Butcher, L. and N. Davies (2020), “Road pricing”, Briefing paper No. CBP 3732, House of Commons Library, London, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN03732/SN03732.pdf.

CCC (2021a), Independent Assessment: The UK’s Net Zero Strategy, Climate Change Committee, London, https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/independent-assessment-the-uks-net-zero-strategy/.

CCC (2021b), Progress in Reducing Emissions, 2021 Report to Parliament, Climate Change Committee, London, https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Progress-in-reducing-emissions-2021-Report-to-Parliament.pdf.

CCC (2021c), Progress in Adapting to Climate Change, 2021 Report to Parliament, Climate Change Committee, London, https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Progress-in-adapting-to-climate-change-2021-Report-to-Parliament.pdf.

CCC (2020), The Sixth Carbon Budget - The UK’s path to Net Zero, Climate Change Committee, London, https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/sixth-carbon-budget/.

Cuming, V. (2021), How COP26 Climate Pledges Compare in Run-up to Earth Day, BloombergNEF, London, https://assets.bbhub.io/professional/sites/24/BloombergNEF-NDC-comparison-note-2021.pdf.

Davis, J. (2020), “UK has ’led the world’ in destroying the natural environment”, 26 September, News, Natural History Museum, London, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2020/september/uk-has-led-the-world-in-destroying-the-natural-environment.html.

Defra (2021), UK Biodiversity Indicators 2021 Revised, Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, London, https://data.jncc.gov.uk/data/31925413-3fa4-4382-962f-6ac2c168d542/ukbi2021-summary-booklet.pdf.

Environment Agency (2021), Summary of the draft river basin management plans, Policy paper, Environment Agency, London, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/summary-of-the-draft-river-basin-management-plans/summary-of-the-draft-river-basin-management-plans.

Hayhow, D. et al. (2019), State of Nature Report 2019, State of Nature Partnership, Nottingham, https://nbn.org.uk/stateofnature2019/reports/.

HM Government (2021), Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener, HM Government, London, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/net-zero-strategy.

HM Treasury (2021), Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021: A Stronger Economy for the British People, HM Treasury, London, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/budget-2021-documents.

HM Treasury (2020a), Green Book Review 2020: Findings and Response, HM Treasury, London, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/937700/Green_Book_Review_final_report_241120v2.pdf.

HM Treasury (2020b), National Infrastructure Strategy: Fairer, Faster, Greener, HM Treasury, London, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/938539/NIS_Report_Web_Accessible.pdf.

HoCs (2021a), Biodiversity in the UK: Bloom or Bust?, House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/6498/documents/70656/default/.

HoCs (2021b), Overview of the English Rail System, House of Commons, Committee of Public Accounts, London, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/6565/documents/71150/default/.

JNCC (2019), Sixth National Report to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Overview of the UK Assessments of Progress for the Aichi Targets, Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough, https://data.jncc.gov.uk/data/527ff89f-5f6b-4e06-bde6-b823e0ddcb9a/UK-CBD-Overview-UKAssessmentsofProgress-AichiTargets-web.pdf.

NAO (2021a), Green Homes Grant Voucher Scheme, National Audit Office, London, https://www.nao.org.uk/report/green-homes-grant/.

NAO (2021b), Environmental Tax Measures, National Audit Office, London, https://www.nao.org.uk/report/environmental-tax-measures/.

Nesbit, M. (2019), Development of an assessment framework on environmental governance in the EU member states, Environmental Governance Assessment: United Kingdom, No 07.0203/2017/764990/SER/ENV.E.4, Institute for European Environmental Policy, Brussels, https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/cafdbfbb-a3b9-42d8-b3c9-05e8f2c6a6fe/library/628629da-1d90-4c7d-a40b-d4c27622eee3/details.

NIC (2021), Valuing Natural Capital in Infrastructure, National Infrastructure Commission, London, https://nic.org.uk/insights/valuing-natural-capital-in-infrastructure/.

O’Callaghan, B. and E. Murdock (2021), Are We Building Back Better: Evidence from 2020 and Pathways to Inclusive Green Recovery Spending, United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/35281/AWBBB.pdf.

OBR (2021), Economic and Fiscal Outlook, October, Office for Budget Responsibility, London, https://obr.uk/download/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-october-2021/.

OECD (2021a), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2021 Issue 2: Preliminary version, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/66c5ac2c-en.

OECD (2021b), Environment at a Glance Indicators, https://www.oecd.org/environment/environment-at-a-glance/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

OECD (2021c), OECD Green Recovery Database (database), https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/themes/green-recovery#Green-recovery-database (accessed on 15 December 2021).

PHE (2019), Review of Interventions to Improve Outdoor Air Quality and Public Health, Public Health England, London, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/938623/Review_of_interventions_to_improve_air_quality_March-2019-2018572.pdf.

Transport for Quality of Life (2020), Press release: Research suggests the Government’s biggest-ever road investment strategy (£27 billion over 5 years) breaches the UK’s commitments on climate change, http://www.transportforqualityoflife.com/u/files/200710_PRESS_RELEASE_FINAL_The_carbon_impact_of_the_national_roads_programme.pdf.

Annex 1. Actions taken to implement selected recommendations from the 2002 OECD environmental performance review of the United Kingdom

|

Recommendations |

Actions taken |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Chapter 1. Towards green growth |

||

|

Continue efforts to reduce NOx, particulate and NMVOC emissions, in light of persistent problems with high concentrations of NO2, PM10 and ozone in some areas. |

Emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx), non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOC) and particulate matter (PM) have declined over recent decades with the shift from coal to gas and renewable energy, and stricter emission standards and regulations. The 2017 UK Air Quality Plan for nitrogen dioxide (NO2) set out the government approach for reducing roadside NO2 concentrations and meeting the statutory limits. In 2020, 5 of 43 zones exceeded the annual mean limit value for NO2, down from 33 in 2019, due to reduced traffic flows associated with COVID‑19 restrictions. The 2019 Clean Air Strategy and National Air Pollution Control Programme (to be revised in 2022) detailed policies and measures to meet the 2020 and 2030 emission reduction targets. The 2021 Environment Act provides for two legally binding targets for PM2.5 to be set in 2022. |

|

|

Implement area-wide emission control more consistently, providing more precise guidance to local authorities and taking measures to reinforce their management capacity where necessary. |

As of mid-2021, about two-thirds of local authorities had one or more “Air Quality Management Area” (AQMAs) in areas exceeding objectives. Most AQMAs are in urban areas and have been established to address air pollution from traffic emissions of NO2, PM10 or both. Action plans set out the measures (such as congestion charging, traffic management, planning and financial incentives) the local authorities propose to meet the air quality objectives. The Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) advises local authorities on how to prepare their action plan through a dedicated website. |

|

|

Strengthen transport demand management measures, including through the use of local authorities’ new powers to set road use charges and workplace parking levies. |

London has introduced low emission and ultra-low emission zones and congestion charges that have reduced congestion and air pollution. Bath, Birmingham and Portsmouth have introduced Clean Air Zones, charging entry to the most polluting vehicles. However, private cars are not always charged. |

|

|

Improve integration of air management concerns into transport policies and plans, particularly at the local level through better land use planning. |

The 2021 Transport Decarbonisation Plan aims to deliver significant benefits from improved air quality; and to embed transport decarbonisation principles in spatial planning. Efforts are being made to align the climate and well-being agendas through street redesign and management. |

|

|

Continue to integrate local, regional and global atmospheric management concerns into energy policies. |

UK’s commitment to end coal use by 2024, EU air quality regulations and EU Emissions Trading System (replaced by the UK ETS in 2021), support to renewables and increased carbon price support rates have contributed to significant reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from electricity generation. The 2021 Net Zero Strategy calls for fully decarbonising electricity by 2035, subject to security of supply, and rapidly electrifying transport, heating and industry. These actions would be supplemented by low-carbon hydrogen, carbon capture and land-use change. |

|

|

Increase the number of designated sensitive areas and complete urban waste water treatment infrastructure, especially that needed to reduce pollutant discharges to coastal waters. |

In 2016, 398 sensitive areas and 233 catchments of sensitive areas covered 45% of the national territory. The United Kingdom complied with the collection and secondary treatment targets of the EU Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive, and was close to achieving the more stringent target. However, pollution from sewer overflows is of particular concern. |

|

|

Fully implement the biodiversity action plan through local action plans, and improve monitoring of the condition of individual species and habitats. |

The 2021 Environment Act calls on local authorities to develop local nature recovery strategies in their spatial planning, encourages landowners to sign up, on a voluntary basis, to long-term conservation covenants; and introduces Biodiversity Net Gain to property developers. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds improved species monitoring through its 2019 state of nature report. A UK Habitat Classification was released in 2018 to improve habitat monitoring. |

|

|

Continue to encourage the expansion of woodland and forest cover and to promote sustainable forestry in line with the UK forestry standard. |

The United Kingdom has allocated GBP 750 million to England’s Nature for Climate Fund to support the creation, restoration and management of woodland and peatland habitats from 2020 to 2025. The devolved administrations have also published plans for woodland creation and peatland restoration. |

|

|

Further promote agri-environmental programmes, as allowed for under the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Further extend the shift of CAP resources towards integrated rural development programmes, including through agri-environmental measures. |

The United Kingdom has devoted a large share (70%) of the CAP Rural Development Programme (RDP) 2014-20 to ecosystem protection, particularly England (81%). Scotland is spending 18% of its RDP on forest carbon sequestration (3% for Northern Ireland and Wales, 0% for England). Little is spent on practices meant to mitigate GHG and ammonia emissions. In 2020, UK agricultural support included GBP 2.7 billion in payments that may incentivise outputs and increase environmental pressure through on-farm investments and input use. This is four times the agricultural support for environmental protection under the RDP. Most of the payments inherited from the CAP will gradually be replaced by payments for public goods through environmental land management schemes. |

|

|

Develop and implement comprehensive legislative and institutional mechanisms for marine nature conservation, fully implementing the EU Habitats Directive in the 200-mile exclusive economic zone. |

The countries have jointly developed the UK Marine Strategy (between 2012 and 2015, updated in 2019 and 2021) to achieve good environmental status in their marine waters by 2020. The extent of marine protected areas has increased by 30 million hectares over 2010-20. |

|

|

Continue to promote measures to conserve wildlife species that are in decline, and regularly monitor their status as a basis for establishing related conservation measures. |

Priority species for conservation action have been identified for each UK country on the basis of their threatened status or population trends. Measures implemented to prevent species extinction and improve the conservation status of species in decline include protected areas, species reintroductions and reinforcement programmes, together with a suite of broader conservation measures intended to improve land management, promote habitat recovery or restoration, and reduce pollution through, for example, agri-environment schemes and legal protection. |

|

|

Strengthen inspection and enforcement and related monitoring efforts, as necessary to implement revised environmental regulations. |

The risk-based approach, together with the emphasis on compliance promotion, has helped UK environmental authorities to improve permit compliance levels over the years. Over the last decade, the United Kingdom has emphasised administrative response to non-compliance, as the number of criminal prosecutions has declined steadily. The decriminalisation of less severe violations has made enforcement more proportionate to non-compliance, more expedient and more efficient. Enforcement undertakings have been increasingly used. |

|

|

Continue to integrate environmental concerns into land use planning. |

Strategic environmental assessment is widely used, particularly in land-use planning. For example, it is integrated into the broader sustainability assessment, which is a legal prerequisite for the adoption of local spatial plans in England and Wales. |

|

|

Reflect sustainable development objectives more systematically in public service agreements and through integrated analysis (e.g. extended cost benefit analysis) of policy measures. |

The United Kingdom has made progress in integrating environmental objectives into departmental plans. The 2021 Autumn Budget and Spending Review outlines the public spending contribution to net zero and other green objectives. The Green Book provides guidance on how to appraise the costs and benefits of policies, projects and programmes. It has been updated to include stronger guidance on establishing clear objectives; to account for the effects of climate change even where net zero is not the primary objective of a proposal; to embed a natural capital approach in appraisal, and to better value unmonetisable costs and benefits. |

|

|

Amend the Building Act to address the operational energy efficiency of existing buildings, and launch a comprehensive policy, with clearly defined targets, to substantially upgrade energy efficiency in existing buildings. |

Building Regulations have been amended many times and are under review. Despite progress in improving energy efficiency of buildings in the past decade, the United Kingdom is not on track to meet targets set in the 2017 Clean Growth Strategy (prior to its net zero commitment). The 2021 Heat and Buildings Strategy provides for standards and regulations to improve buildings performance and phase out the installation of high-carbon fossil fuel boilers off the gas grid. It also provides public funding to support energy efficiency and low-carbon heat for social housing, those in fuel poverty, local authorities and public sector buildings, plus a small number of heat pumps and some heat networks. There are concerns about insufficient funding to backup the strategy and the lack of mechanisms to improve energy efficiency of owner-occupied homes. |

|

|

Strengthen the incentive role of economic instruments in inducing targeted modal shifts in transport, with appropriate phasing and consultation. |

Fuel duties have been frozen since 2011, reducing the incentive to shift to public and active transport. The cycle to work scheme has successfully supported biking. See above on low emission and Clean Air Zones. See below on other economic incentives. |

|

|

Work to increase public perception of fuel- and vehicle-related taxes as tools for achieving environmental goals, improving public transport and promoting low-emission vehicles and their refuelling infrastructure. |

Although the UK government has recognised taxes as an important instrument for environmental policy, the exchequer departments have limited understanding of their environmental impact. The government has yet to clarify the role of taxes in achieving UK climate targets. |

|

|

Review and adjust, if appropriate, economic incentives in the energy and transport sectors to facilitate full implementation of the climate change programme. |

Carbon emissions are priced through the UK ETS, fuel duties and a climate change levy (CCL). In addition, since 2013, a carbon price floor taxes fossil fuels used in electricity generation via carbon price support (CPS) rates on top of the ETS allowances price. The increase in CPS rates has helped drastically reduce the share of coal in electricity generation. The complex system of explicit and implicit carbon prices sends inconsistent signals across sectors and fuels. In the past decade, tighter emission performance standards and vehicle excise duty (VED) based on CO2 emissions have helped reduce average CO2 emissions per km of new vehicle sales. However, average emissions of new cars have risen over 2016-19, due to the rising share of larger vehicles. The 2017 VED reform reversed the upward trend in diesel car registrations by introducing a criterion on NOx emissions. However, it weakened the link between VED liabilities and CO2 emissions after a vehicle is first registered, reducing the incentive to choose low-polluting second-hand vehicles. The United Kingdom encourages the use of passenger cars through favourable company car tax taxation. |

|

|

Study and develop the extension of the climate change levy into a broader based tax on greenhouse gas emissions. |

The CCL applies to solid fossil fuels, liquefied petroleum gas, natural gas and electricity when supplied to business and public sector users. It is not based on fuels’ carbon content. Energy-intensive businesses with a climate change agreement with the Environmental Protection Agency are entitled to discount CCL rates. |

|

|

Increase official development assistance towards the Rio commitment of 0.7% of GNI and establish clear procedures for mainstreaming environmental objectives into projects. |

The United Kingdom allocated 0.7% of its gross national income (GNI) to official development assistance (ODA) over 2013-20. In 2019, it committed GBP 11.6 billion in dedicated climate finance over the 2021/22–2025/26 period equally split between mitigation and adaptation. This is double the level of support over the previous five-year period and is protected at this level against the announced temporary cuts in ODA from 0.7% to 0.5% of GNI. The funding is additional to the contribution to large multilateral development banks, some of which will be used to support climate-related projects. The United Kingdom has also committed to align the full extent of its ODA spending with the Paris Agreement. |

|

|

Chapter 2. Promoting a circular economy |

||

|

Establish a systematic data collection and information system concerning the generation, recovery and disposal of non-municipal waste. |