This chapter reviews trends in foreign investment in Egypt and their development benefits using various national and international data sources. It looks at the performance of foreign investment relative to neighbouring and emerging economies as well as foreign investment distribution across economic activities and Egyptian governorates. The chapter also examines foreign investment development outcomes, including on productivity, labour market outcomes, export, and supply chain linkages with the local economy.

OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Egypt 2020

Chapter 1. Foreign investment trends and development benefits

Abstract

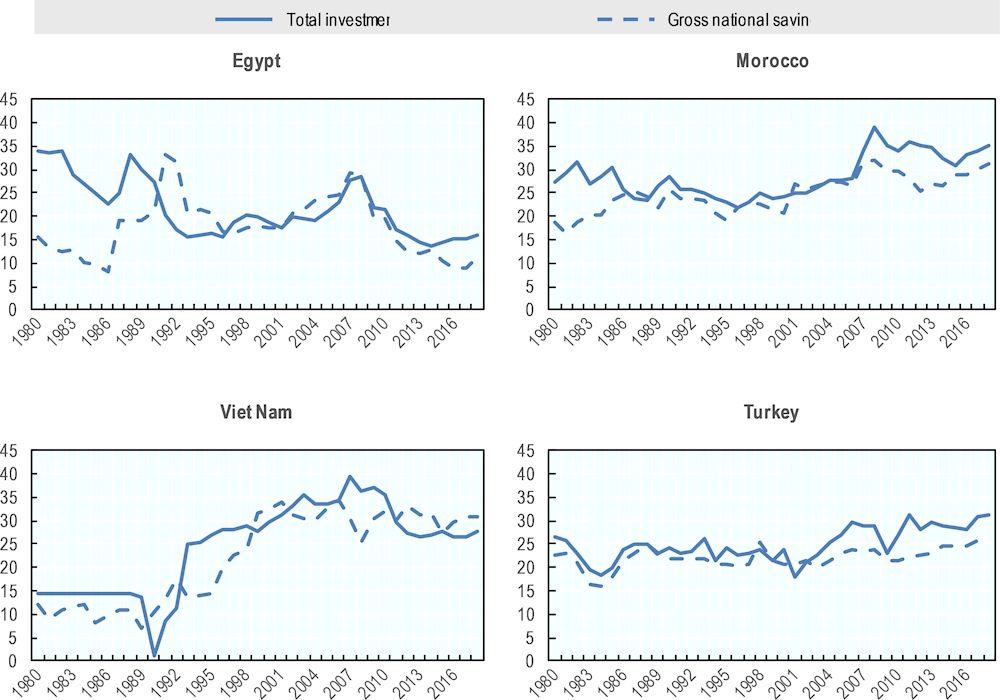

Egypt has a huge potential to leverage its strategic location, considerable market size and young workforce to attract untapped investment. Despite periods of increases over the last three decades, Egypt has not maintained stable investment and savings growth rates, both key engines of economic development. The contribution of investment to GDP has even declined since 1980 despite the progressive opening of the Egyptian economy to the private sector, initiated in the 1970s and referred to as infitah (open door policy). The investment-to-GDP ratio in 2017 was 15% in Egypt compared to 25-35% in Morocco, Turkey or Viet Nam.

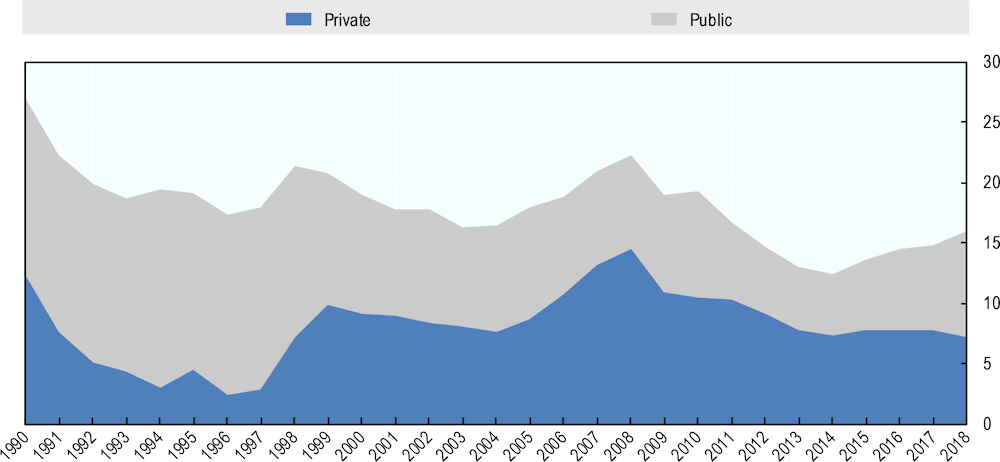

Regulatory and institutional constraints, among other barriers, were the main causes of the sluggish improvement. The Egyptian state's shrinking contribution to investment since the late 1980s was also one of the factors behind the plunge in aggregate investment, as this decline was not compensated by an equivalent increase in private investment in the 1990s. The share of public investment fluctuated between 40% and 45% of total investment. In contrast, in the OECD area, public investment represents 15% of total investment.

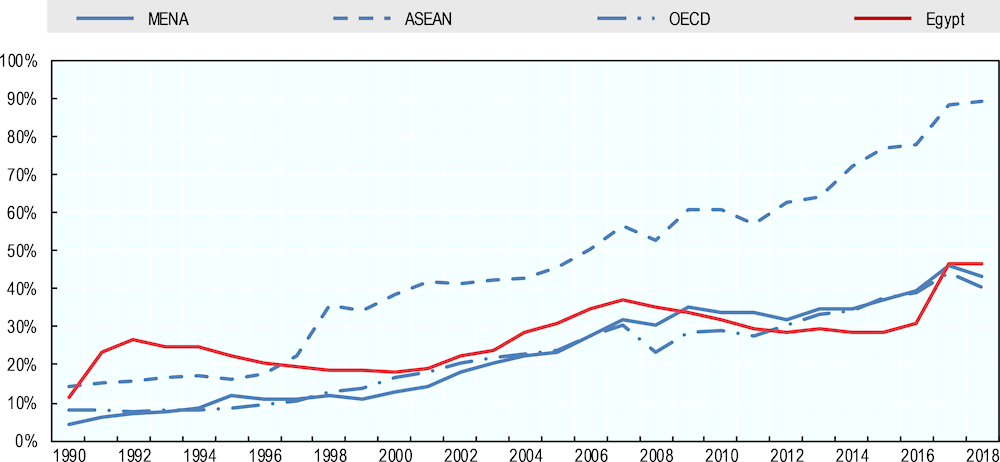

Attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) is central to the development strategy of Egypt, particularly in light of lacklustre domestic saving and investment performance. Inward FDI surged in several waves over the last three decades, pushed, inter alia, by economic reforms. Macroeconomic stabilisation, the country accession to the WTO in 1995 and further liberalisation of cross-border investment in the early 2000s paved the way for a sustained wave of FDI increase between 2000 and 2007, amplified by record rates in global growth. Despite these periods of increases, Egypt’s long-term FDI performance was nonetheless less impressive than of other emerging countries in Southeast Asia.

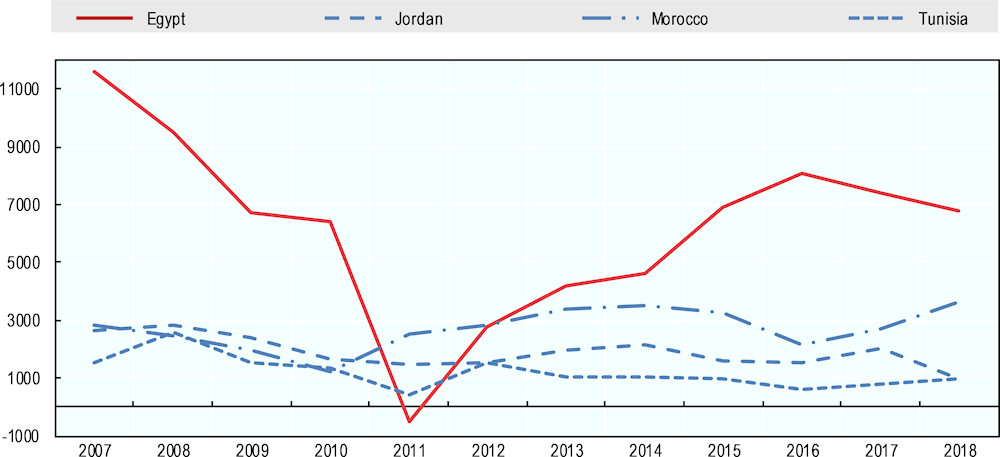

Encouraging prospects surround FDI performance in Egypt since 2012, despite the recent episodes of global and regional instability. The global financial crisis hit cross-border investment to Egypt harder and longer than to neighbouring countries. The external shock brought to light structural challenges in the economy impeding the deployment of foreign investment. These challenges included the overdependence on the public sector, limited product market competition and weak export diversification. The post-2011 instability in the region had a negative effect with some investors suspending their operations, downscaling their commitments or withdrawing their investments altogether. There is a surge in foreign investors’ interest in Egypt in the last years, driven by macroeconomic stabilisation and market reforms, although fiscal constraints hit domestic demand.

FDI is present in few economic activities and concentrated in specific geographical areas. Foreign investment goes into natural resources, real estate, construction, and light manufacturing. Most of these sectors have limited innovation-creating potential due to their relatively low complexity. Meanwhile, greenfield FDI is taking place in promising sectors such as in chemicals and in renewable energies. FDI is also highly concentrated. The top five governorates accounted for 90% of FDI, while the bottom 22 governorates share the remaining 10%. This unequal distribution of FDI within Egypt is also found in other emerging countries.

The impact of FDI on sustainable development in Egypt is broadly positive, but could be significantly improved, notably in areas related to labour productivity. Foreign MNEs in the country are found to outperform local firms with respect to innovation, gender equality and energy efficiency. In contrast, they are not more productive nor pay higher than their domestic peers, in contrast with what is observed in other emerging countries. There is also ample room for foreign investment to further support Egypt’s participation in higher value-added segments of global value chains (GVCs), notably by strengthening supply chain linkages through the importing of intermediate products.

Investment trends in Egypt since the post-infitah era

Despite remarkable periods of increases over the past three decades, Egypt has not maintained stable investment and savings growth rates, both key engines of economic development. The contribution of investment to GDP has gradually declined since 1980 despite the progressive openness of the Egyptian economy to the private sector, initiated in the 1970s and referred to as infitah (open-door policy) (Figure 1.1). The variations in investment trends have paralleled those in gross savings rate, except in the 1980s where their co-movement was disconnected. Investment and savings rates reached an all-time low of 13-15% of GDP in 2017, after a peak of roughly 30% in 1988 and 2008. Other countries with similar levels of per capita income registered stronger performance. In Morocco, Turkey or Viet Nam, investment and savings rates have fluctuated less than in Egypt over the last three decades, oscillating between 25% and 35% of GDP in 2017, depending on the country, which is twice as high as in Egypt.

Figure 1.1. Investment and savings trends in Egypt and other emerging economies

Source: OECD based on the IMF World Economic Outlook.

Multiple and evolving factors have been behind the decline in investment and savings rates in Egypt over the last three decades. Egypt’s poor macroeconomic environment in the 1980s, among other challenges the economy was facing, was not conducive to private sector development. The country signed in 1991 an IMF-led stabilisation programme to correct important macroeconomic imbalances, in the form of a large government budget deficit. The government’s stabilisation fiscal and monetary policy reforms successfully reduced budget deficits and increased credit available to the private sector, with little adverse consequences on output (Subramanian, 1997). The macroeconomic readjustments, coupled with other market-based reforms, helped contain the steep decline in investment and savings rates between 1988 and 1993 (Figure 1.1).

Regulatory and institutional constraints, among other barriers, were the main causes of the sluggish improvement in investment in the mid-1990s (Zaki, 2001). It is only in the late 1990s and mid-2000s that investment increased, a trend that was abruptly reversed by the 2007 global financial crisis. Investment and savings have witnessed a moderate improvement only since 2015, encouraged by a sequence of macroeconomic reforms and the decision to float the exchange rate in 2016. This decision contributed to the devaluation of the Egyptian pound, bringing the official rate closer to its black market counterpart, narrowing a gap that has deterred domestic and foreign investors in the past.

The Egyptian state's shrinking contribution to investment since the late 1980s was one of the factors behind the plunge in aggregate investment (Figure 1.2). This decline was not compensated by an equivalent increase in private investment in the 1990s. Despite their decline, public investments in non-infrastructure activities may have crowded out private investment in the country (Fawzy and El-Megharbel, 2004). The public sector continues to play a critical role in financing the Egyptian economy. Over the last ten years, the share of public investment fluctuated between 40% and 45% of total investment (i.e. public and private). In contrast, in the OECD area, public investment represents 15% of total investment and 3% of GDP.

Figure 1.2. Gross fixed capital formation: Public versus private investment

Source: OECD based on the World Bank Development Indicators.

Investment trends across economic sectors in Egypt indicate that private investors finance different types of activities compared to public actors (Figure 1.3). Private investment is predominant in manufacturing, real-estate projects, natural gas, communication, and tourism. In contrast, the public sector and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) invest typically in infrastructure and energy (i.e. electricity, transport and logistics, and water) as well as in health and education services. There are nonetheless activities in which both public and private actors invest. For instance, public investment in manufacturing represented 14% of total investment between 2011 and 2017. The distribution of investment between the public and private sector is altered by the fact that utilities sectors are totally or partly closed to private investors (see chapter 2). In OECD countries, education and transports receive most of public investments and more than half of it goes to regional and local areas.

Figure 1.3. Public and private investment by economic activities: Boom versus bust periods

Note: Public investment includes investment by the government sector, economic authorities and SOEs. Data for the fiscal year 2016/2017 is preliminary.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Central Bank of Egypt statistics.

Long-term trends in foreign investment in Egypt

Attracting foreign investment is central to the development strategy of Egypt, particularly in light of lacklustre domestic saving and investment performance. Inward foreign direct investment (FDI) surged in several waves over the last three decades, pushed, among other reasons, by ambitious economic reforms that are discussed in the next chapters. The first wave of inward FDI increase was between 1985 and 1990. Macroeconomic stabilisation, the country accession to the WTO in 1995 and further liberalisation of cross-border investment in the early 2000s paved the way for a second and more sustained wave of FDI between 2000 and 2007, amplified by record rates in global growth. Over that period, the FDI stock to GDP ratio registered an impressive surge of 10 percentage points.

Egypt’s long-term FDI performance has been remarkable in comparison with the wider MENA region but less with other emerging regions (Figure 1.4). Countries that underwent similar transformation of their economic systems, such as the economies in transition of Central and Eastern Europe or of Southeast Asia managed to cumulate higher FDI flows, relative to their respective economic size (UNCTAD, 2011). In the early 1990s FDI stock in Egypt represented around 25% of GDP, a ratio at that time higher than in the MENA and ASEAN regions as well as in the OECD area. Nonetheless, the growth of inward FDI into Egypt has not been sustained in a period when other developing countries, such as in the ASEAN group, attracted higher inflows. Overall FDI flows in Egypt witnessed strong periods of booms and busts.

Figure 1.4. FDI stock in Egypt compared to MENA and other economic groups

Note: MENA and ASEAN: Accumulation of BOP FDI flows were used when FDI stocks were not available for selected countries and/or historical years. Egypt: data for 1990-2003 correspond to accumulation of BOP FDI flows from 1977 onwards.

Source: OECD calculations based on the IMF Balance of Payments and International Investment position database, the IMF World Economic Outlook database and OECD Foreign Direct Investment statistics database.

The global financial crisis hit inward FDI to Egypt harder and longer than to other countries of the region (Figure 1.5). The external shock brought to light important structural challenges in the Egyptian economy impeding the deployment of foreign investment. These challenges, examined throughout this Review, included the overdependence on the public sector for economic activity, limited product market competition, inadequate infrastructure, and weak export diversification and structural transformation. FDI flows in Egypt recorded an all-time low in 2011 following the events witnessed by the region, including Egypt (Figure 1.5). These events have had negative spill-over effects on the attractiveness of the entire region with some investors suspending their operations, downscaling their commitments or withdrawing their investments altogether (OECD, 2014).

Figure 1.5. Inward FDI flows in Egypt in the aftermath of 2007 global financial crisis

Source: OECD based on the IMF Balance of Payments database.

Egypt’s FDI performance is improving

Between 2012 and 2016, FDI flows have been on an upward, albeit moderate, trend representing around 2% of GDP, still below the pre-2007 crisis levels of 8%. In 2016, Egypt was for the first time the largest recipient of FDI flows in the MENA region, ahead of Saudi Arabia, accounting for nearly 30% of total FDI flows received in the MENA region as a whole, compared to between 8% and 20% in 2005-14, excluding the negative FDI inflows recorded in 2011. Egypt also maintained in 2018 its position as the largest FDI recipient of foreign investment in Africa, although inflows decreased in comparison with 2016 and 2017 (UNCTAD, 2019 and Figure 1.5). End of 2018 the FDI stock in the country was equal to 47% of GDP, higher than in the MENA region (43%) and in the OECD (40%) and lower than in ASEAN (89%) (Figure 1.4).

Macroeconomic stabilisation and legislative reforms drove the important surge in foreign investors’ interest in Egypt, even if budgetary measures also hit domestic demand. The recent surge in FDI may also reflect a challenge for domestic firms to finance themselves on the domestic market. Most of the recent foreign investments have been mergers and acquisitions or petroleum sector investments rather than new greenfield FDI projects (CBE, 2018 and 2019).

Foreign investment trends in Egypt by economic activity

In Egypt, as in most of the MENA region, FDI is concentrated in natural resources, real estate, construction, and light manufacturing (e.g. textiles). Most of these sectors have limited job-creating potential due to their relatively low labour-intensity. Since 2010, instability in the region has further skewed the sectoral composition of FDI towards the natural resources sector, which has been more immune to political shocks (OECD, 2014). FDI inflows in non-oil manufacturing and services sectors have stagnated, while these sectors have a higher propensity to create jobs and promote transfers of technology and managerial knowledge, making it more challenging for Egypt to participate in global value chains.

FDI flow statistics published by the CBE indicate that the oil sector represented the bulk of FDI received by Egypt over the last few years, followed by real estate and construction, which covers the purchase of land and homes by non-residents (Table 1.1). Manufacturing represented less than 10% of total inflows. Besides the real estate sector, services FDI was driven by financial activities. In contrast, communication and IT represented less than 4% of total inflows.

Table 1.1. FDI flows in Egypt by economic activity, as a share of total inflows

|

2013/14 |

2014/15 |

2015/16 |

2016/17 |

2017/18 |

2018/19* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oil |

71.7 |

58.4 |

53.5 |

61.3 |

67.3 |

70.6 |

|

Manufacturing |

2.0 |

2.3 |

3.4 |

5.8 |

10 |

7.1 |

|

Agriculture |

0.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.6 |

|

Construction |

2.2 |

6.0 |

1.5 |

0.9 |

4.5 |

2.3 |

|

Services |

4 |

10.0 |

10.4 |

9.4 |

11.2 |

15.7 |

|

Real estate |

1.4 |

6.2 |

3.6 |

3.1 |

2.7 |

8.8 |

|

Finance |

1 |

2.0 |

3.8 |

1.6 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

|

Tourism |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

|

Communications |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

3.4 |

1.1 |

|

Other services |

1.5 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

4.0 |

2.9 |

3.4 |

|

Unallocated |

19.9 |

23.3 |

31.2 |

22.4 |

6.9 |

3.7 |

Note: *December-July 2018/19. ‘Inflows’ = increase in liabilities and differ from total net incurrence of liabilities published in Balance of Payments, which are defined as increases minus decreases in liabilities.

Source: Central Bank of Egypt, Annual reports of 2014/15; 2015/16; 2016/17; 2017/18 and Monthly Update of the External Position of the Egyptian Economy on July/December 2018/19.

FDI stock estimates by GAFI reveal a more diversified distribution across economic activities than with flows statistics of the last few years. Upstream oil and gas exploration and mining companies represented a quarter of the FDI stock in 2017. Foreign investment in this sector was nonetheless the lowest in terms of the number of FDI projects and of source countries.1 The other leading FDI activities were finance and manufacturing and further behind construction, communication and information technology, tourism and agriculture. These estimations were based on a compilation system, designed by GAFI, to align Egypt with the definition of the IMF Balance of Payment Manual Sixth Edition (BPM6). Annex A provides a detailed assessment and recommendations on compiling FDI statistics in Egypt.

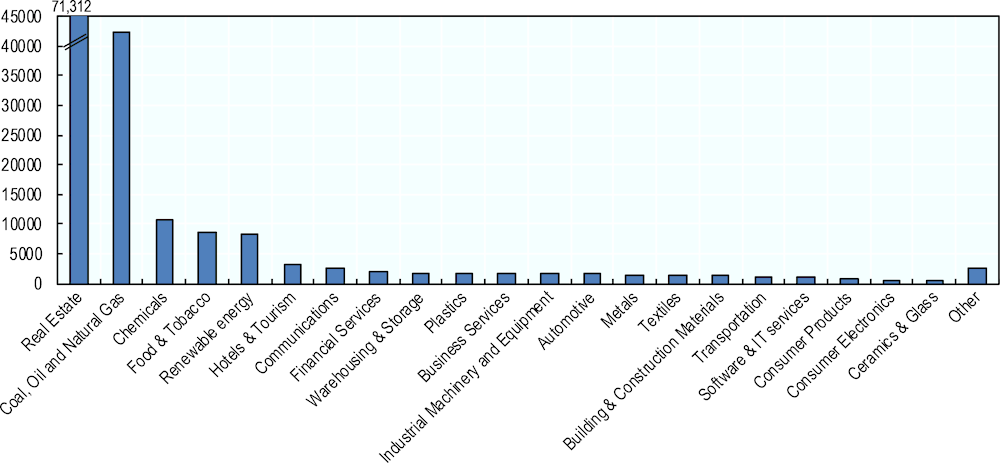

International data on announced greenfield FDI projects offer additional insights on cross-border investment by economic activity in Egypt. Real estate and natural resources alone represented 70% of greenfield FDI capital announced between 2006 and 2017 (Figure 1.6). The manufacture of chemicals and foodstuffs and renewable energy were the other most attractive sectors for FDI (16% of total greenfield FDI). Manufacturing activities such as automotive and textiles attracted much lower cross-border investment, even if FDI projects in textile were among the most numerous. This corroborates earlier evidence that foreign investment in textile and clothing was limited to the labour-intensive segments of the supply chain (Nugent and Abdel-Latif, 2010). Beyond real estate and tourism, services FDI was divided between financial and business services (largest in terms of project number), communication and logistics.

Figure 1.6. Greenfield FDI by economic activity, 2006-2017

Source: OECD based on fDi Markets Database.

Trends in foreign investment in Egypt from a home country perspective

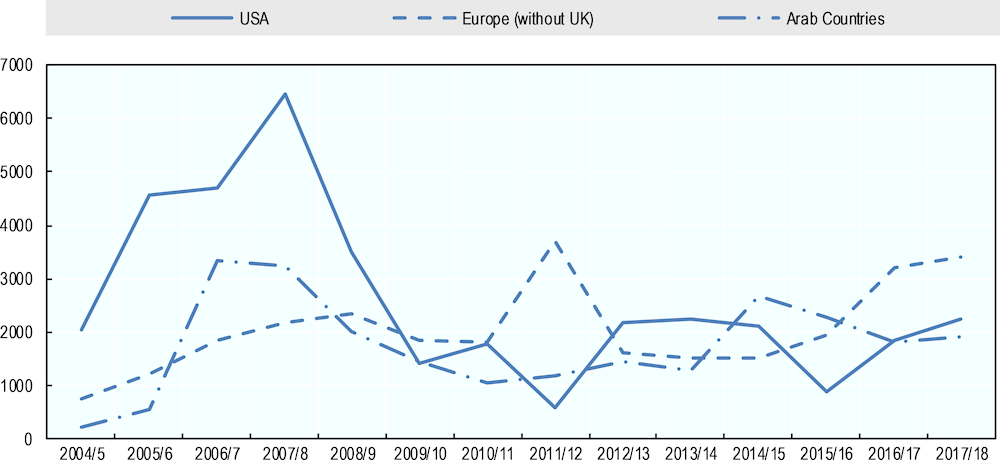

Another way of assessing FDI trends in Egypt is to examine which countries are the major investors in Egypt and what they report investing. Arab countries, EU member states, and the US are home to 90% of FDI flows in Egypt since 2004. Investors from these three regional blocks responded differently to a succession of global, regional, and domestic shocks that affected the Egyptian economy in the past decade. FDI from the countries of the European Union to Egypt proved resistant to the 2007 global financial crisis while investments from the US and, to a lower extent, Arab countries collapsed (Figure 1.7). End-2017 FDI flows from Arab States and the US to Egypt were still far below their pre-2007 crisis levels.

Figure 1.7. EU investment resisted more than other regions to global and domestic shocks

Note: Data for 2016/17 and 2017/18 is provisional.

Source: OECD based on Central Bank of Egypt statistics.

Estimates of bilateral FDI stocks, which were produced by GAFI from their developed compilation system, indicate that major investors in Egypt in 2017 were the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, the US, Italy, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Germany and Switzerland.2 From the perspective of FDI flows, British and Dutch investment witnessed an exponential surge, most of it establishing projects in the capital-intensive hydrocarbons sector. Recently, some investments by the UK were undertaken in the higher education sector while Dutch companies invested in renewable energies. French FDI has remained rather immune to the instability triggered by the 2011 events. France has 160 subsidiaries, mostly large firms listed in the CAC 40 in a variety of sectors (agro food, transport, manufacturing, etc.). Most of the French-owned firms produce for the domestic or regional African market. Some companies have invested in R&D in sectors such as automotive equipment. Recently French investors have started to consider Egypt as a location for efficiency-seeking investments in connection with regional and global value chains. Outside of the top investors, Egypt has attracted rapidly growing investment from China over the last decade.

FDI statistics reported by home countries provide further indications on FDI trends in Egypt. Understanding patterns of cross-border investment is becoming increasingly difficult owing to the rise of special purpose entities and pass-through investments in third countries for fiscal reasons or to benefit from the protection of an investment treaty. Statistics by the CBE indicate that OECD member countries represented 77% of cumulated FDI inflows between 2004 and 2017. Table 1.2 shows the stock of FDI from OECD countries based on home country reporting. Companies from OECD countries invested USD 65 billion as of end 2016, equivalent to 66% of the total FDI stock in Egypt. The US, the Netherlands, and the UK report the three highest FDI positions among OECD countries. In contrast, the CBE flows statistics indicate that the Netherland is, by far, not among the top three investors in Egypt. Possible sources of discrepancy between OECD and CBE statistics are differences in valuation methodologies (OECD, 2020).

Table 1.2. FDI position of OECD member countries in Egypt

(2016 or nearest year available; USD million)

|

OECD Total |

67507 |

|

United States |

22202 |

|

Netherlands |

20082 |

|

United Kingdom (2014) |

9794 |

|

Italy |

7445 |

|

Germany |

1844 |

|

France |

1655 |

|

Switzerland |

978 |

|

Belgium |

725 |

|

Spain |

718 |

|

Greece |

517 |

|

Other OECD |

1547 |

Source: OECD International Direct Investment Database.

Recent estimates by GAFI of inward FDI positions compare immediate and ultimate investing countries.3 Such evidence sheds further light on the top OECD investors in Egypt. The estimates suggest that the Netherlands, followed by Luxembourg and Belgium are, to varying degrees, pass-through countries for investments in Egypt. For instance, 80% of the investments immediately controlled by Dutch companies in Egypt have their ultimate controlling parents in Italy, the UK, the US, South Korea, and Mexico. According to GAFI, round tripping by Egyptian businesses, i.e. domestic firms that transit through a third country to invest in Egypt, is limited (0.13 USD billion).

Examining activities data of US MNEs affiliates in Egypt can yield further insights into the nature of their investment. By any measures, Egypt is one of the leading destination for US MNEs in the Middle East and Africa (Table 1.3). There is nonetheless space to attract additional US affiliates, which are significantly more active in other regional hubs such as South Africa and Turkey. Surprisingly, US MNEs in Morocco employ more people than in Egypt despite being less numerous, having lower sales, and providing lower compensation of employees. Statistics from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis indicate that the number of US affiliates in Egypt, their assets and their compensation of employees increased between 2009 and 2015. In contrast, US affiliates’ sales and number of employees declined over the same period. The latter dropped from 40 000 to 31 000 employees.

Table 1.3. Activities of US MNEs in Egypt and selected emerging countries

(2015; USD million except employment)

|

|

Affiliates # |

Assets |

Sales |

Compensation of employees |

Employment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Egypt |

81 |

28 074 |

12 519 |

717 |

31 000 |

|

Jordan |

11 |

1 691 |

1 047 |

85 |

2 500 |

|

Morocco |

35 |

3 598 |

2 721 |

410 |

33 600 |

|

South Africa |

267 |

56 248 |

46 904 |

4 641 |

169 500 |

|

Turkey |

174 |

30 966 |

33 572 |

2 505 |

67 700 |

|

Viet Nam |

67 |

15 308 |

7 882 |

696 |

71 300 |

Note: # only those affiliates with assets, sales or net income > USD 25 million.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce.

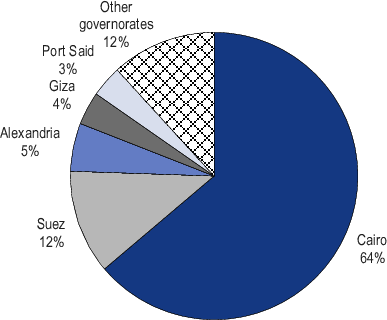

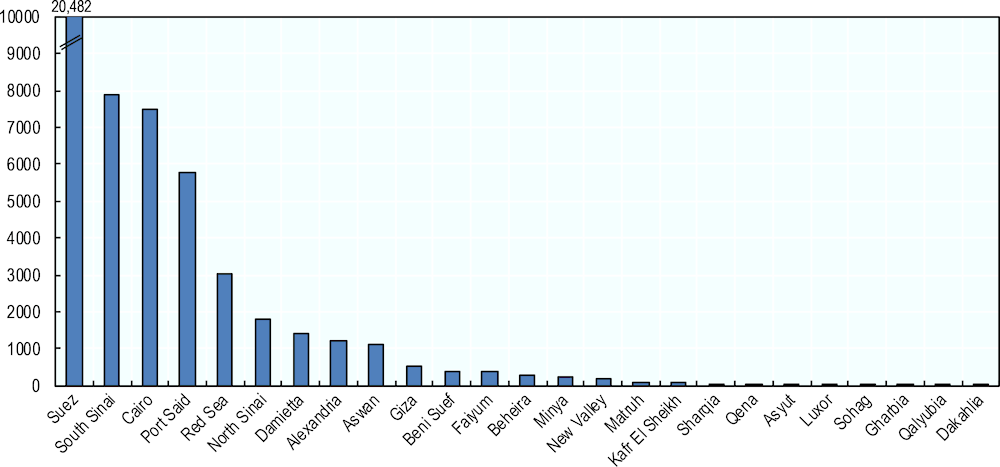

Foreign investment distribution across Egyptian governorates

The distribution of cross-border investment is unequal across the 27 Egyptian governorates. Between 1992 and 2008, the neighbouring governorates of Cairo and Giza concentrated 60% of greenfield FDI. More recent data on announced greenfield FDI projects between 2006 and 2017 confirm the unequal distribution of FDI within Egypt. The top five governorates account for 90% of greenfield FDI, while the bottom 22 governorates share the remaining 10%. The governorates with low shares of FDI are mostly landlocked areas, with the exception of the greater Cairo area. Greenfield FDI in services, particularly in ICT and finance, are more concentrated in a small number of governorates, while manufacturing FDI projects are relatively more geographically dispersed (Hanafi, 2014).

Figure 1.8. The distribution of announced greenfield FDI capital across the 27 governorates

Source: OECD based on fDi Markets Database.

FDI trends within Egypt change when taking into account the size of the governorate. Relative to population levels, greenfield FDI is the highest in the governorates bordering the Suez Canal and Cairo and lowest in the more remote, less developed, governorates (Figure 1.8, 1.9). Variations in greenfield FDI per capita across governorates are massive, including within the top ten governorates such as Suez (USD 20 000), Cairo (USD 7 500) and Alexandria (USD 1 225). At the bottom end, greenfield FDI per capita in the governorates of Asyut, Fayoum, Louxor, Qena and 10 others is lower than USD 500.

Figure 1.9. Greenfield FDI per capita, by governorate

Source: OECD based on fDi Markets Database and the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS).

The distribution of foreign multinationals is as unequal within Egypt as in other emerging countries. In Morocco, Tunisia, Turkey, or Indonesia the difference between the top and bottom regions, measured as the percentage of foreign-owned firms of total firms within the region, are higher than in Egypt. In Morocco, the four regions that contribute to 60% of the country’s GDP, out of 16 regions, concentrate also 80% of total FDI stock (Ettoumi et al., 2015). More than 30% of Tunisia’s FDI stock is concentrated in the capital and, overall, the coastal regions retain more than 80% of non-hydrocarbons FDI (OECD, 2017).

The unequal concentration of MNEs within Egypt, as for other countries, is largely the result of disparities in the level of economic activity across governorates. MNEs activity tends to be, to varying degrees, more concentrated spatially than domestic activity, in industrial or economic hubs, which may exacerbate within-country disparities. Recent evidence indicates that MNEs activity in Egypt is only slightly more concentrated than domestic economic activity, similar to other African countries, Chile or Mexico (Lejarraga and Ragoussis, 2019). Besides the level of economy activity, domestic private investment, well-functioning zones and labour abundance positively influence the distribution of FDI across Egypt’s governorates. Sub-national policies such as the existence of One-Stop Shop offices in some specific regions are found not to affect the FDI distribution in the country (Hanafy, 2014).

Evidence from Cairo city, which extends over the governorates of Cairo, Giza and Qualyubia, sheds some light on the relationship between MNEs presence and local economic activity. At all levels, FDI numbers for Cairo indicate that its attractiveness for foreign investors is undisputed. Cairo may have overshadowed other cities or regions’ ability to attract foreign investment, leading to population movements towards agglomeration centres. In response to this dilemma, and due to the growing congestion of Cairo city, Egypt has established industrial zones since the mid-seventies, which have increasingly attracted large, capital-intensive, FDI projects. The growing concentration of FDI in new industrial cities has been triggered by the availability of industrial land rather than attractiveness of these new locations (UN-Habitat and IHS-Erasmus University Rotterdam, 2018). This movement may nevertheless support a geographic dispersion of economic activities and improve the livelihood of the surrounding population.

The contribution of foreign investment to sustainable development in Egypt

FDI can benefit the host economy beyond its direct contribution to the capital stock. Under the right conditions, FDI in Egypt can raise productivity, boost exports and participation in global value chains (GVCs), and improve the standard of living of different segments of the population. It can contribute to job creation, human capital development, technological progress, knowledge diffusion, efficient reallocation of resources, and environmental greening. It can also serve as a conduit for domestic industries to access international markets and participate in global value chains. As such, FDI in Egypt can play an important role for progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Sustainable development benefits of FDI are not automatic. Different chapters of the Review examine how private sector reforms and selected policies in Egypt could enable FDI’s potential to advance sustainable development. The following sub-sections use novel indicators the OECD developed to describe how foreign investment relates to aspects of sustainable development in host economies, including in Egypt (Box 1.1). The indicators monitor FDI outcomes on productivity and innovation, inclusiveness (i.e. employment and job quality, skills, and gender), and supply chain linkages in GVCs.

Box 1.1. The OECD FDI Qualities Indicators

FDI Qualities Indicators describe how FDI relates to sustainable development in host countries. They are structured around economic, social and environmental sustainability. An assessment of all 17 SDGs, and their corresponding targets, was undertaken to identify the spectrum of FDI Qualities – that is, areas where FDI contributes to achieving the SDGs. This assessment considers the extent to which FDI potential for advancing the SDGs is reflected in the OECD Policy Framework of Investment including related guidelines such as the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises and the OECD Policy Guidance for Investment in Clean Energy Infrastructure.

The FDI Qualities Indicators focus on five clusters: productivity and innovation, employment and job quality, skills, gender equality, and carbon footprint. For each of the five clusters, a number of different outcomes are identified and used to produce indicators that relate them to FDI or activity of foreign multinationals, allowing for comparisons both within and across clusters so as to identify potential sustainability trade-offs.

Taking into account the country-specific context, policymakers can use FDI Qualities Indicators to assess how FDI supports national policy objectives, where challenges lie, and in what areas policy action is needed. Indicators also allow cross-country comparisons and benchmarking against regional peers or income groups, which, taking into account the country context, can help to identify good practices and make evidence-based policy decisions.

An important value added of the FDI Qualities Indicators is that they reveal cross-country differences in how FDI relates to sustainable development. Existing studies touch upon some of the outcomes covered in this report, but generally only examine one dimension of sustainability, offering only a partial view of FDI’s contribution to sustainable development, without revealing important cross-country and cross-cluster differences.

The impact of FDI on sustainable development can be direct and indirect, i.e. through spillover effects. Direct impacts relate to the activities of foreign multinationals and how they affect socio-economic and environmental outcomes. Indirect impacts refer to how foreign firms influence sustainable development through their interaction with domestic firms. FDI Qualities Indicators cannot fully disentangle both effects, but provide some direction as to what mechanisms are at play for a given sustainability outcome.

Source: OECD (2019a)

Foreign-owned firms outperform domestic ones in several development areas

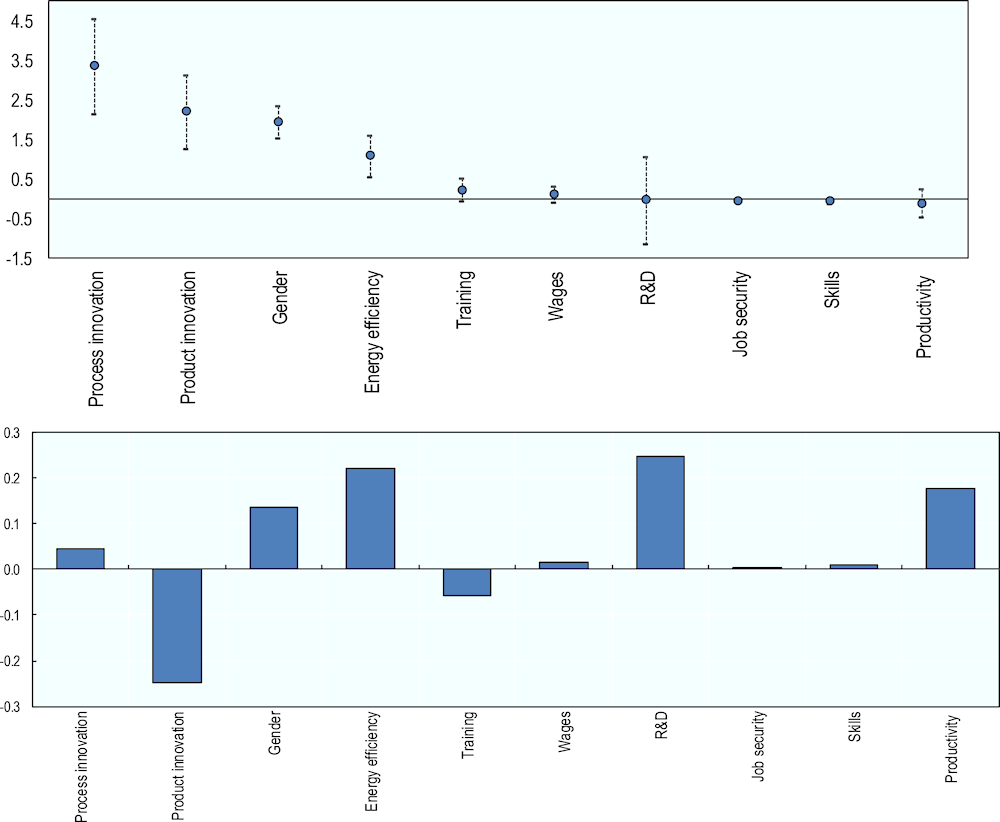

Foreign manufacturers in Egypt are found to outperform local firms across several development areas, but not all (Figure 1.10 – panel A). The indicators show a stronger performance of foreign-owned firms in terms of process and product innovation, gender equality and energy efficiency. In contrast, the indicators reveal that foreign companies in Egypt do not have higher labour productivity levels nor pay higher wages than their domestic peers, as it is often the case in other countries (OECD, 2019a).

Figure 1.10. FDI relationship to sustainable development outcomes in Egypt

Note: Panel A includes confidence intervals for each indicator. The intervals report the extent of firm heterogeneity, i.e. the extent to which the data at the firm level vary around the mean. They also indicate whether the difference of average outcomes of foreign and domestic firms is statistically significant at the 95% level. If the confidence interval crosses the zero line, the difference of average outcomes of foreign and domestic firms is not statistically significant. For further details, see OECD (2019a).

Source: OECD based on the OECD FDI Qualities Indicators.

Affiliates of foreign firms may be less productive than domestically-owned firms when significant advantages, market protection and rents are given to domestic firms, often state-owned firms (OECD, 2019a). As described in chapter 2 of the Review, foreign firms established in Egypt may find it difficult to access a market dominated by protected state-owned firms, or their access is constrained due to regulatory and non-regulatory restrictions. It is important to note that there is a productivity premium of foreign firms in industries of the Egyptian economy where distortions are less important.

FDI in Egypt tends be concentrated into industries with better sustainability outcomes. FDI can lead to changes in the sectoral composition of the economic activity and may influence development positively or negatively if foreign firms directly or indirectly affect sectoral development outcomes. Figure 1.10 (B) shows whether FDI is concentrated in sectors with relatively higher or lower development outcomes. The results indicate that if MNE affiliates in Egypt are slightly less productive than domestic firms, they tend to be concentrated in more productive industries of the economy. In contrast, foreign investment tends to focus on economic activities where there is little product and process innovation.

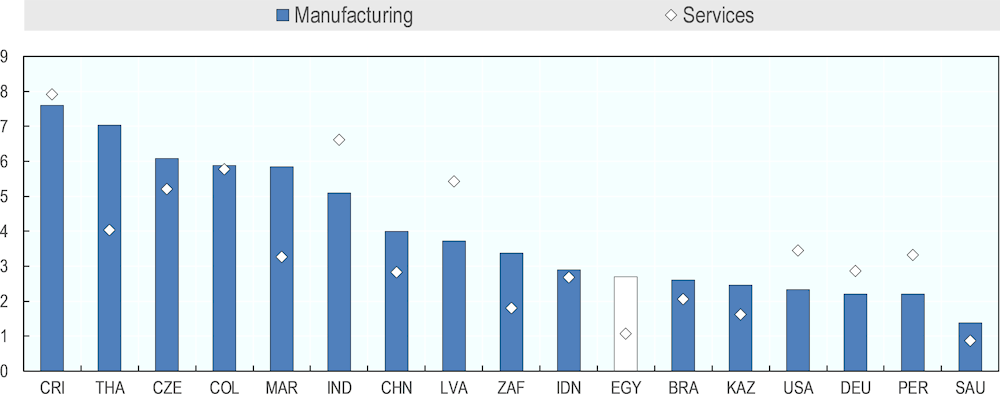

A closer look at FDI and job creation shows that job created per dollar invested remain low compared to other countries, particularly for services investors (Figure 1.11). The majority of jobs remain heavily skewed toward low-skill and labour intensive activities. However, industries that require more technical skills, such as chemicals and electronic components, are beginning to attract more FDI, and account for growing shares of job creation.

Figure 1.11. Greenfield FDI and job creation in Egypt and other selected countries

Source: OECD based on the OECD FDI Qualities Indicators and fDi Markets Database.

The role of foreign investment in boosting participation in global value chains

One objective of the Egypt 2030 vision is to maximise value added, increase local content in the manufacturing sector and decrease the trade deficit. Firms’ participation in global value chains (GVCs) has been promoted as a key way to achieve higher export diversification and more sustainable and inclusive development. Along with trade, the “GVC revolution” has been driven to a large extent by MNEs through investment. FDI is not only a channel for exchanging capital across countries, it is also an important channel for exchanging goods, services, and knowledge and serves to link and organise production across countries.

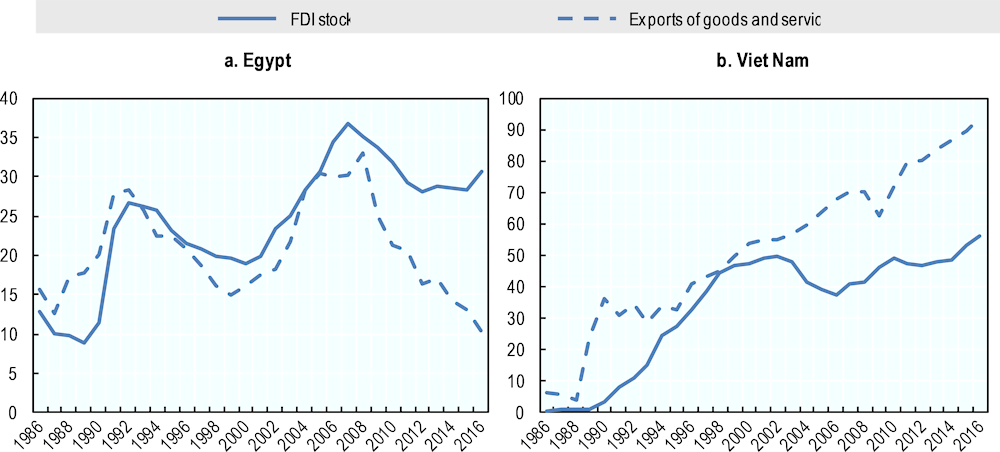

Export of goods and services in Egypt have followed the same trend as FDI stock in the last three decades: a quasi-stagnant trend coupled with several boom and bust episodes (Figure 1.12). The export-to-GDP ratio deteriorated sharply following the 2007 global crisis and has been on a declining trajectory, even following the shallow recovery in the FDI stock in 2015. The history of the co-movement of FDI and export trends in Egypt is radically different from the one for other emerging countries. In Viet Nam, which opened up to the global economy in the 1980s, MNE affiliates played a key role in transforming the country into an export platform (OECD, 2019b). In the early 1990s, both countries had comparable FDI stock and export-to-GDP ratios. By 2016, FDI stock and export-to-GDP ratios in Viet Nam were respectively three times and 10 times higher than in Egypt.

Beyond the magnitude of exports and imports, the nature of traded products also matters for the development of the Egyptian economy and its integration in the global economy. The export basket of Egypt is relatively diversified but remains concentrated in lower value-added products. Trade in services, which constitutes a quarter of global trade, has become an increasingly important factor of global production as most goods require services for their fabrication. In Egypt trade in services represented only around 9% of GDP in 2016, compared to 15% in MENA (27% in Jordan, 23% in Morocco, 14% in Tunisia). Restrictions in services trade are still high in Egypt (Karam and Zaki, 2015).

Figure 1.12. Co-movement of FDI stock and exports in Egypt and Viet Nam

Source: OECD based on World Integrated Trade Solutions Database (WITS) and UNCTAD statistics.

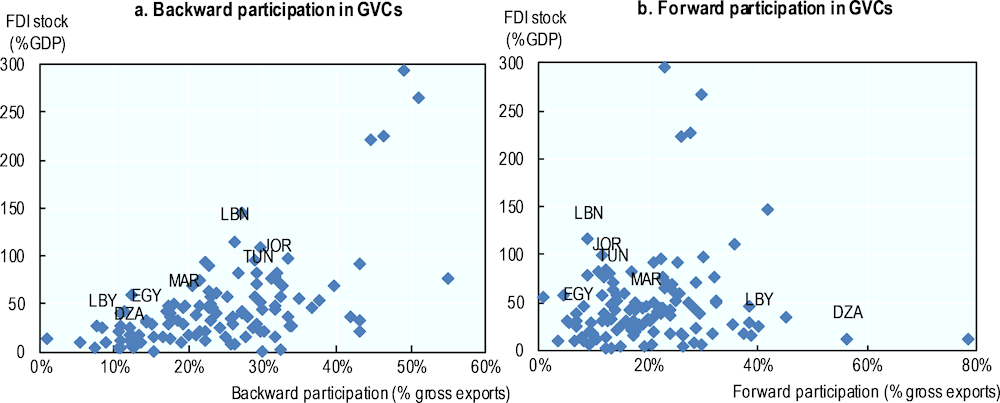

Egypt has lower shares of participation in GVCs than other MED economies.4 Larger countries such as Egypt may have lower backward participation, i.e. the value added used in a country’s own exports, because of their higher local capacity for producing specific inputs, mostly in manufactured, fuel, and food supply chains. Lower participation in backward GVCs may also be driven by high import costs or restrictions. In contrast with Morocco or Tunisia, Egypt has more diversified trade and investment partners, beyond Europe. These partners have invested, inter alia, in the country’s zones, on which the government relies to foster integration into GVCs and to promote local development.5 Zones in Egypt are expected to reduce the lengthy and costly import-export procedures, which represent an important barrier for participation in GVCs.

There is ample room for foreign investment to further support Egypt’s participation in GVCs. Egypt’s low FDI stock-to-GDP is associated with an equivalently low participation in GVCs (Figure 1.13). In comparison, countries with higher ratios, such as Jordan, Tunisia or Viet Nam, are also participating more in GVCs. High regulatory and non-regulatory barriers on foreign investment and trade may impede the establishment of MNEs and their participation in GVCs. As discussed in other chapters of the Review, Egypt has moderate levels of regulatory restrictions on FDI in the manufacturing sector. Barriers on FDI and trade in services are however more important. This may impede the deployment of foreign investment in services sectors such as ICT, logistics, or transport, which are crucial for enhancing participation in GVCs.

The development impact of participation in GVCs has been limited, as Egypt has succeeded only to some extent to upgrade its position in supply chains. MNE investment motives and type of activity shape to some extent the development outcomes associated with participation in GVCs. The sectors that received the bulk of FDI in Egypt, e.g. real estate and petroleum activities, are also those with the least segmented supply chains (i.e. few intermediate inputs are needed to produce the final good). As a result, the country remains specialised in low value-added manufacturing activities within these chains leading to little overall developments in terms of types of jobs and income levels.

Figure 1.13. FDI in Egypt is associated with low participation in GVCs, 2009-2012

Source: OECD based on UNCTAD EORA GVC database, IMF BoP, and UNCTAD.

Attracting FDI inflows can stimulate GVC participation by upgrading the country’s productive capabilities to manufacture products that are more complex. Recent evidence indicates that domestic firms more likely to supply foreign affiliates tend to introduce products that are more complex (Javorcik et al, 2018). In Egypt, additional FDI to the machinery and mechanical appliances, computers, chemicals industry and foodstuff industries would increase economic complexity (Box 1.2). As discussed in chapter 4, there is room for investment promotion activities, a relatively cost-effective activity, to be effective in channelling FDI to activities that would help Egypt move into sophisticated segments of the supply chain.

Box 1.2. Upgrading Egypt’s productive capabilities: Where should FDI go?

Countries with comparable export levels can have different levels of complexity in their respective productive capabilities. This is the case when comparing Egypt to Viet Nam. In Viet Nam, half of Vietnamese exports are composed of electronic products. Despite increases in GDP per capita and in exports, Egypt’s economic complexity index has been relatively stagnant since 1995. While Egypt has increased the diversity of its production, it has not moved into products that are more complex. It is still largely natural resource and agriculture based. Petroleum oils and gases account for over 30% of its net exports. When considering all natural resource-based or agricultural products, this share is above 50%.

Egypt’s product space reveals the country should develop the machinery and chemicals and allied industry, and foodstuff since they would increase the country’s product complexity index. It is well located in the product space and has, on average, shorter distances to more complex products. By moving into nearby, more complex, products using to a large extent productive knowledge that already exists within the country, Egypt can increase the complexity of its product space and improve its income level.

While products in the foodstuff and textile community are closer in distance in terms of productive knowledge and capabilities of the country, products in the machinery and chemicals and allied industry have a higher product complexity index. Therefore, developing them would have a larger impact on Egypt’s average complexity. To meet this specific goal and to enhance production in other sectors, Egypt should focus on attracting sustainable FDI to existing industries with the aim of improving their productivity and ability to jump to nearby opportunities.

Source: Bustos S. & Yildirim M.A. (2017), Egypt’s Manufacturing Sector: Seizing on an Advantageous Product Space Position, Policy Paper, May 2017, The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.

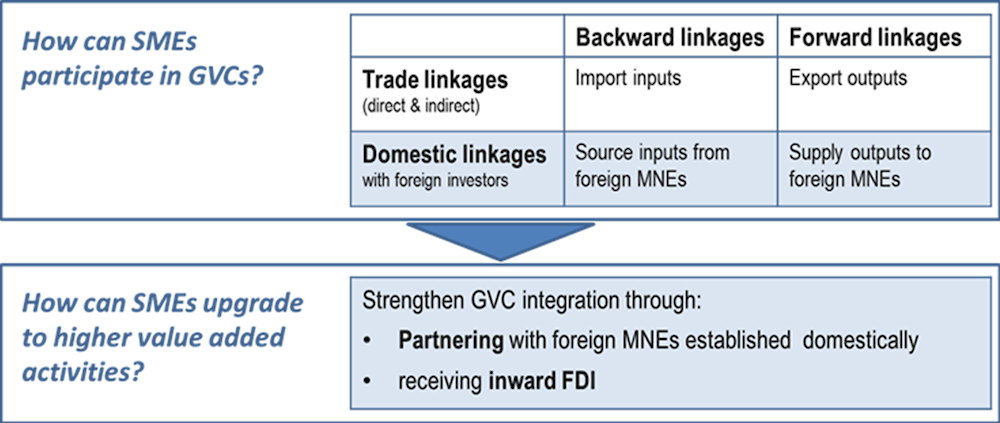

The extent of MNE-SME supply chain linkages in Egypt

Leveraging FDI in Egypt to enhance supply chain linkages with small and medium enterprises (SMEs) can be an important opportunity for a more inclusive development trajectory. MNE-SME supply chain linkages involve the purchase and supply of goods and services between foreign MNEs affiliates and domestic SMEs. Given the performance premium of foreign firms over domestic ones, MNE-SME supply chain linkages are expected to result in positive impact on SMEs, depending on the extent and intensity of linkages and the sector of activity. Linkages may enable SMEs to export, develop managerial skills, upgrade products or services to international standards, innovate, reduce costs, improve working conditions for employees, or lead to more sustainable production.6 Furthermore, the impact of linkages depends on the characteristics of SMEs themselves.

Manufacturing MNEs in Egypt source a large share of inputs locally

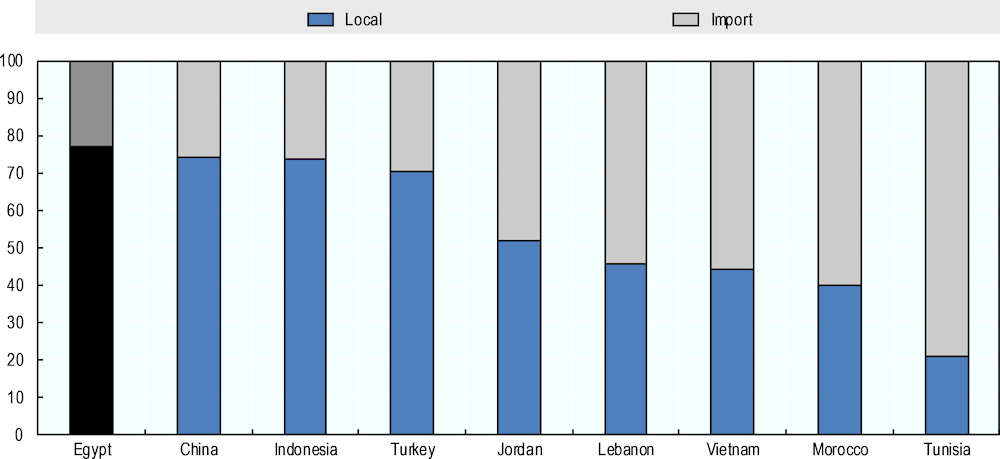

Foreign manufacturers established in Egypt source significantly more from local producers than from other countries in the MED region (Figure 1.14).7 As in Indonesia or Viet Nam, MNE affiliates in Egypt source more than half of intermediate inputs from firms (both domestic and foreign) that produce locally. In Morocco and Jordan, this share is around 40% and in Tunisia less than 30%. These results mirror to some extent Egypt’s low backward participation in GVC previously shown.

Variations between Egypt and other emerging countries may reflect differences in the sectoral structure of the economy, positioning within specific value chains and policy factors. For instance, significant local sourcing may be the result of a high local capacity for producing specific and competitive inputs. It may also indicate, however, higher trade barriers for imports of intermediate inputs. In the case of Egypt, the low sourcing of imported goods by foreign manufacturers may reflect local content requirements, as those in the Free Zones, or restrictions and lengthy procedures on imports. The differences in shares of local sourcing by foreign MNEs may thus not indicate better integration of the local firms in production networks of MNEs established in the MED region. Nevertheless, these shares do provide a reference point on whether some linkages exist in the first place.

In Egypt, as in the majority of MED economies, MNE affiliates in manufacturing are concentrated in the food and garment sectors. Accordingly, the shares presented in Figure 1.14 often represent an average of foreign firms’ local sourcing practices in these sectors. In Egypt, foreign investors in manufacturing appear to have a diversified portfolio, from low-value added industries, such as food processing, to machinery production, a sector in which foreign manufacturers purchases of locally produced intermediates are relatively high (OECD, 2018).

Figure 1.14. Foreign MNEs in Egypt source more from local intermediates than MNEs in other countries

Note: The indicators in this figure include averages for manufacturing as a whole. It does not include services. Source: OECD estimates based on OECD-UNIDO (2019) and World Bank Enterprise Surveys.

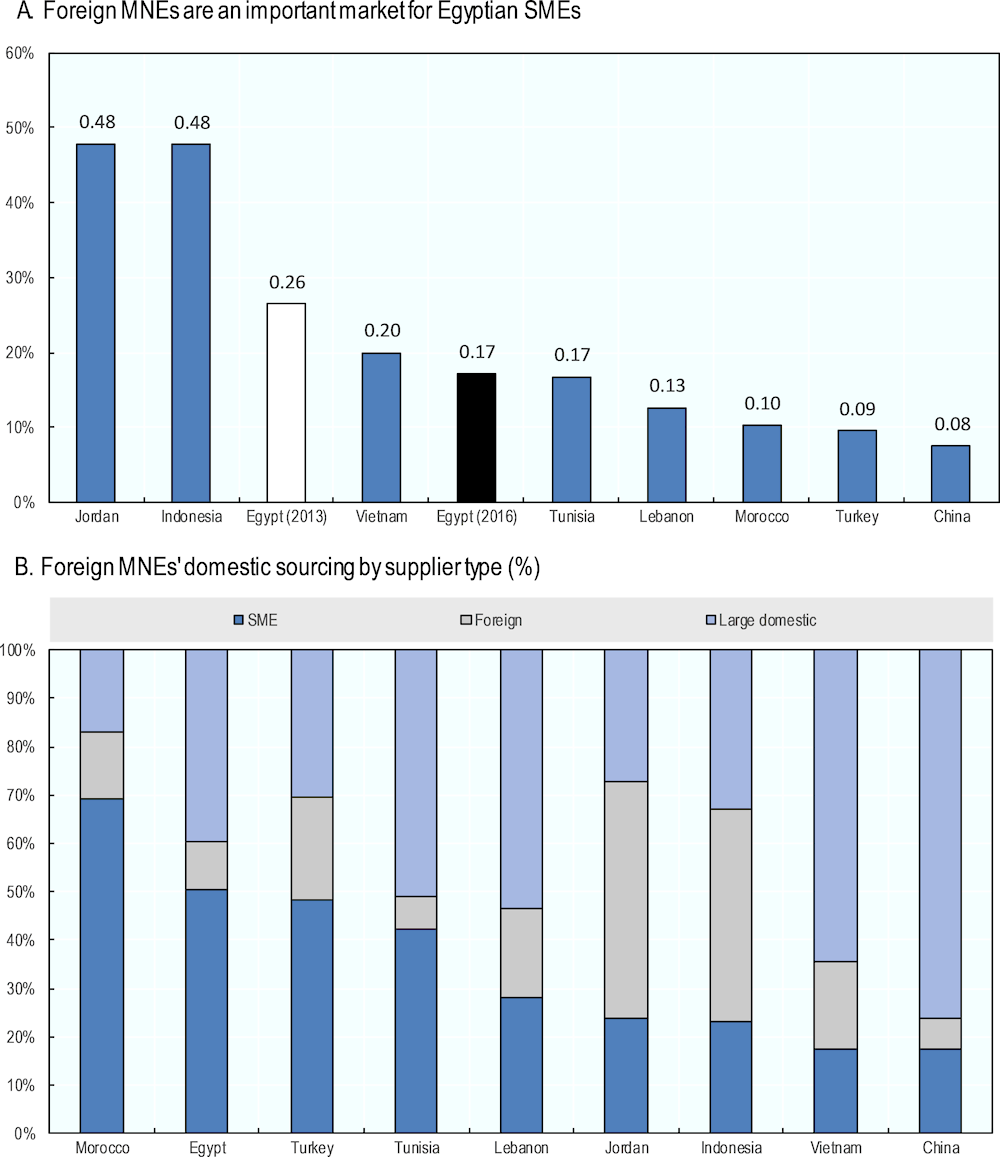

MNE affiliates are a significant source of revenue for domestic suppliers

In terms of market size, MNE affiliates in Egypt represent a significant source of revenue for local suppliers. Nearly 20% of locally produced intermediate products are purchased by foreign-owned manufacturers in Egypt, although this share has declined slightly from 26% in 2013 to 17% in 2016. While important, the market created by MNE affiliates in Egypt contrasts with their high reliance on local intermediates relative to importing. Comparison with other emerging countries indicates that there is room for MNE affiliates to represent a bigger market for Egyptian suppliers. Foreign MNEs in Egypt represent a larger market for local suppliers than in Morocco or Turkey but much less than in Indonesia or Jordan (Figure 1.15, Panel A). MNE affiliates in Viet Nam do not represent a larger market for local intermediates producers than MNE affiliates in Egypt, despite their more important contribution to national economic activity.

Local suppliers of MNEs can be domestic large firms, domestic SMEs, or other foreign-owned firms.8 SMEs in Egypt account for up to half of all inputs supplied to MNE affiliates, similar to Turkey and Tunisia. Large firms are also important suppliers. In Jordan and Indonesia, supplying relationships within foreign-owned firms are considerably higher than in Egypt (Figure 1.15, Panel B). Foreign MNEs often source from large first-tier international suppliers that are themselves MNEs for more capital-intensive and complex value chains/products (e.g. automotive) (OECD-UNIDO, 2019). From a policy perspective, different types of business linkages may have different effects on the local economy. For instance, investment that results in foreign-foreign linkages may be less effective in promoting greater inclusiveness than linkages between a foreign and a domestic firm.

Figure 1.15. Foreign MNEs are an important market for Egyptian SMEs

Note: The indicators in this figure include averages for manufacturing as a whole. It does not include services.

Source: OECD estimates based on OECD-UNIDO (2019) and on World Bank Enterprise Surveys.

References

AJG Simoes, CA Hidalgo (2011), The Economic Complexity Observatory: An Analytical Tool for Understanding the Dynamics of Economic Development, Workshops at the Twenty-Fifth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2011).

Bustos S. & Yildirim M.A. (2017), Egypt’s Manufacturing Sector: Seizing on an Advantageous Product Space Position, Policy Paper, May 2017, The Lebanese Centre for Policy Studies.

Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) (2019a), External Position of the Egyptian Economy

CBE (2019b), Annual Report 2017/2018

CBE (2018), Annual Report 2016/2017

CBE (2017), Annual Report 2015/2016

CBE (2016), Annual Report 2014/2015

Ettoumi Y, S.Toufik, S. Koubaa & IE. Hadad (2016), Regional attractiveness for Foreign Direct Investments in developing countries: empirical review, IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 2016;18 (10) :74-78.

Fawzy, Samiha & El-Megharbel, Nihal (2004), Public and Private Investment in Egypt: Crowding-Out or Crowding-In?, ECES Working Paper 96-A, the Egyptian Center for Economic Studies

Hanafy, S. (2014), Determinants of FDI location in Egypt: Empirical analysis using governorate panel data, No. 13-2015, Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics.

Javorcik, B. S., Lo Turco, A., & Maggioni, D. (2017), New and Improved: Does FDI Boost Production Complexity in Host Countries? The Economic Journal.

Karam, F., & Zaki, C. (2015), Trade volume and economic growth in the MENA region: Goods or services? Economic Modelling, 45, 22-37.

Lejárraga, Iza; Ragoussis, Alexandros. (2018), Beyond Capital: Monitoring Development Outcomes of Multinational Enterprises, Policy Research working paper; no. WPS 8686. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/342571545336579695/Beyond-Capital-Monitoring-Development-Outcomes-of-Multinational-Enterprises

Nugent, J. B., & Abdel-Latif, A. (2010), “A quiz on the net benefits of trade creation and trade diversion in the QIZs of Jordan and Egypt”, In Economic Research Forum Working Papers (Vol. 514).

OECD (2020), OECD Review of Foreign Direct Investment Statistics: Egypt. www.oecd.org/investment/OECD-Review-of-Foreign-Direct-Investment-Statistics-Egypt.pdf

OECD (2019a), FDI Qualities Indicators: Measuring the sustainable development impacts of investment, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/investment/fdi-qualities-indicators.htm.

OECD (2019b), OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Viet Nam 2018, OECD Investment Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264282957-en.

OECD (2018), Making global value chains more inclusive in the MED region: The role of MNE-SME linkages, Background note prepared for the workshop “Business linkages in the MED region: Policies and tools”, 17-18 April 2018, Beirut, Lebanon, http://www.oecd.org/mena/competitiveness/BN-Making-global-value-chains-more-inclusive-Beirut-042018.pdf.

OECD (2017), Making investment promotion work for sustainable development in the Southern Mediterranean: Focus on incentives and territorial development, Issues Note, October 2017, http://www.oecd.org/mena/competitiveness/REPORT-Regional-EU-OECD-IPA-Workshop-Paris-201710.pdf.

OECD (2014), “Protecting Investment in Arab Countries in Transition: Legal frameworks for investment in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia”, document prepared for the OECD Investment Committee, 4 November 2014, Paris, http://oecd.records.oecd.org/LES_RM/livelink.exe?func=ll&objId=7583945&objAction=properties&version=0&nexturl=http:%2F%2Foecd%2Erecords%2Eoecd%2Eorg%2FLES_RM%2Flivelink%2Eexe.

OECD-UNIDO (2019), Integrating Southeast Asian SMEs in Global Value Chains: Enabling Linkages with Foreign Investors, Paris, www.oecd.org/investment/Integrating-Southeast-Asian-SMEs-in-global-value-chains.pdf.

Subramanian, M. A. (1997), The Egyptian stabilization experience: An analytical retrospective, No. 97-105, International Monetary Fund.

UN-Habitat and IHS-Erasmus University Rotterdam (2018) “The State of African Cities 2018: The geography of African investment.” (Wall R.S., Maseland J., Rochell K. and Spaliviero M). United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat).

UNCTAD (2019), World Investment Report 2019, UNCTAD Publishing, Geneva.

UNCTAD (2011), Investment Policy Review Egypt, UNCTAD Publishing, Geneva.

Youssef, H., Alnashar, S. Bahaa Hamed; Erian, J., Elshawarby, A., Zaki, C. (2019), Egypt Economic Monitor : From Floating to Thriving – Taking Egypt's Exports to New Levels, Washington, D.C., World Bank Group.

Zaki, M. Y. (2001), IMF-supported stabilization programs and their critics: Evidence from the recent experience of Egypt, World development, 29(11), 1867-1883.

Annex 1.A. Measuring FDI and participation in GVCs

Compiling Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) statistics in Egypt

Internationally harmonised, timely, and reliable FDI statistics are essential for policymaking and to assess the trends and developments in FDI activity globally, regionally, and at the country level. FDI is one of the major types of investment included in the balance of payments (BOP) and international investment position (IIP) statistics. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), in its Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, 6th edition (BPM6), and the OECD, in its Benchmark Definition of FDI, 4th edition (BMD4), present recommendations for compiling FDI statistics. The recommendations of the two agencies are aligned, but the OECD offers supplemental series that are particularly useful in analysing globalisation. The recommended measures of FDI statistics in these guidelines produce meaningful FDI statistics that are part of the larger System of National Accounts and, so, ensure that FDI statistics are compatible with other important economic statistics. Following the recommendations in the international guidelines is critical to producing relevant and coherent FDI statistics. The OECD also hosts the Working Group on International Investment Statistics (WGIIS), which serves as a forum for FDI statisticians from both OECD member countries and non-member countries to share best practices. The WGIIS also conducts research to improve the measurement of FDI.

The OECD conducted a review of FDI statistics of Egypt as part of the OECD project for Enhancing the Investment Climate in Egypt, through Equal Access and Simplified Environment for Investment and Fostered Investment Policy, Legal and Institutional Framework. The OECD prepared an assessment report on the FDI statistics of Egypt being compiled by the General Authority for Investment and Free Zones (GAFI). The review assessed their compatibility with the international guidelines (BPM6 and BMD4), assessed the data sources and estimation methods used, and examined both the feasibility and the usefulness of compiling additional series, such as by country of ultimate investor. The report uses the framework developed by the OECD for assessing the quality of macroeconomic statistics, which focuses on seven dimensions of quality: relevance, accuracy, credibility, timeliness, accessibility, interpretability, and coherence. The review was based on GAFI’s replies to a questionnaire from the OECD on their compilation of FDI statistics, a presentation by three delegates from GAFI’s FDI Intelligence Unit (FDIU) at the October 2016 WGIIS meeting of their FDI compilation system before the WGIIS delegates, and subsequent discussions with them about their system. A capacity-building workshop was organized in April 2018 in Cairo to present the OECD assessment report.

This annex provides a brief summary of the OECD assessment report on FDI statistics in Egypt. It starts with a description of the current system of compilation of FDI statistics in Egypt that are disseminated by the Central Bank of Egypt and its shortcomings. It, then, describes the new compilation system developed by GAFI and the improvements it could bring to the statistics. The annex concludes with a summary of OECD recommendations for further enhancing the quality of these statistics.

Current system for compilation of FDI statistics in Egypt

FDI statistics in Egypt are in a period of transition: the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) and the Foreign Direct Investment Intelligence Unit (FDIU) of the GAFI signed a protocol that calls for cooperation in the compilation and dissemination of FDI statistics according to BPM6 and BMD4. While FDI statistics currently published by the CBE are based on BPM5, the new compilation system developed by the FDIU of GAFI is designed to produce FDI statistics in line with BMD4 and BPM6 standards.

Description

The CBE currently publishes FDI aggregate flows, positions and income as part of the BOP and IIP statistics in accordance with IMF BPM5 standards and following the IMF’s Special Data Dissemination Standards’ (SDDS) recommendations for timeliness. The BOP and IIP FDI statistics disseminated by the CBE use an International Transaction Reporting System (ITRS) as the primary data source for compiling FDI flows. The definition of FDI recommended in the international standards--non-residents’ share of 10 percent or more of the capital in Egyptian enterprises--is used and is based on information from the Capital Market Authorities; direct investment in the petroleum sector is derived from the Ministry of Petroleum. For Inward investment, the GAFI provides data to the CBE on reinvested earnings that are used for capital expansions but not on all reinvested earnings realised by direct investment enterprises during the reporting period. Aggregate FDI statistics are presented according to the asset/liability principle as recommended in the latest international standards. In terms of valuation methods, FDI positions currently published as part of the IIP correspond to the accumulation of FDI flows.

The accessibility of FDI aggregates published as part of BOP and IIP is well ensured on the CBE website except for FDI income aggregates and the breakdown of FDI aggregates by instrument (i.e., equity capital, reinvestment of earnings, and intercompany debt). FDI inflows by partner country are also easily accessible from the CBE website in the Monthly Statistical Bulletin and from the time series database. However, detailed statistics by industry are only accessible in PDF format in the annual report and are less timely. The CBE publishes methodological information related to the compilation of BOP statistics under BPM5 while methodological information could not be located for the IIP nor for the inward FDI flows by partner country and by industry that are published by the CBE.

Issues

There are some important issues with the FDI statistics currently being disseminated by the CBE. First, and foremost, they do not follow the latest international standards—BPM6 and BMD4. In terms of coverage, FDI is composed of different components (equity capital, reinvestment of earnings and intercompany debt), and these components are not currently published by the CBE, which makes it difficult to determine whether certain components are included or not in the statistics. In addition, valuing direct investment positions by accumulating flows is not a method recommended in the international standards because this method fails to account for factors that can have a significant impact on FDI positions, including cumulative reinvested earnings, depreciation of fixed assets, and holding gains and losses at the direct investment enterprise. However, it is often the only option available when an ITRS is the data source. ITRS also raises other potential issues. For example, it is likely that the debtor/creditor principle might not be fully applied in the FDI statistics by partner country that are currently disseminated by the CBE because an ITRS tends to produce data based on the transactor principle.9

Further with regards to the detailed statistics by country and industry published by the CBE, these statistics are limited to inward FDI flows and do not cover FDI positions. As a result, Egypt does not participate in the IMF’s Coordinated Direct Investment Survey (CDIS), which collects FDI position statistics by immediate partner country. Further, the asset/liability presentation is also used for inward FDI flows by partner country, which is not recommended. Rather, the directional presentation, which captures the direction and degree of influence of foreign investors, is recommended for the detailed statistics by partner country. Finally, detail by partner country are only available for the increases in liabilities, while decreases in liabilities are excluded. As regards inward FDI flows by industry that are currently disseminated by the CBE, they use an internal industry classification as opposed to the International Standard Industry Classification Rev 4 (ISIC4) recommended in BMD4.

Planned improvements with the new compilation system developed by GAFI

Description

GAFI developed a new compilation system for FDI position statistics based on financial statements of enterprises. GAFI had attempted in the past to collect information to compile inward FDI positions through an enterprise survey to support the Central Bank with the production of FDI positions as part of the IIP. However, the response rate was very low, and GAFI decided to abandon surveying enterprises and to look for an alternative. GAFI developed a compilation system based on financial statements that foreign-owned enterprises are required by Law to report to GAFI and other government authorities and where confidentiality of the information is also required by Law. GAFI's system is an ingenuous alternative to surveys, is very comprehensive, and should allow the compilation of inward FDI positions according to the latest international standards (BPM6 and BMD4). It will cover all the standard components (except for reinvestment of earnings from the petroleum sector). The new system will also improve various other aspects of coverage. For example, it uses the Framework for Direct Investment Relationships (FDIR) to identify all of the entities in a direct investment relationship, thus covering fellow enterprises.10 In addition, the system seems to ensure good coverage of the various types of debt instruments in the position statistics and will be able to exclude debt between financial intermediaries as recommended in the international guidelines.11 Finally, the system enables the maintenance of a complete and up-to-date register of information on Special Purpose Entities (SPEs), although information related to SPEs in Egypt is not yet separately available.12

With the signing of the protocol between the Ministry of Investment, CBE, and the Ministry of Petroleum in September 2016, the CBE will begin to disseminate the FDI position statistics compiled by the FDIU in Egypt's IIP once the transition to BPM6 has been completed. Under the protocol, the FDIU will be responsible for compiling and disseminating the detailed FDI position statistics by partner country and by industry. When the WGIIS Secretariat visited GAFI in April 2018, GAFI presented inward FDI positions by partner country and by industry for reference year-end 2016 and through June 30, 2017, indicating that the new system is able to produce timely estimates. Data and metadata information for inward FDI positions by partner country and by industry that GAFI will provide for the new system will be published when the first statistics from the new system are published.

In accordance with BMD4, the new system developed by GAFI for compiling inward FDI position statistics by partner country and by industry has been designed to compile the statistics on an extended directional basis as it includes entries for reverse investment transactions and transactions between fellow enterprises as well as information on the Ultimate Controlling Parent (UCP). The system also provides information for the part of Egypt’s outward FDI position appearing in the financial statements of the companies covered. However, the latter field is not completely populated yet because the information is not readily available in the company financial statements.

In addition, in the compilation system developed by GAFI, the partner country allocation is currently based on the citizenship rather than the residency of the direct investor as is recommended in the international standards. GAFI has enabled the implementation of the residency principle in the compilation system, but it has not been used yet as there is need to populate the information on the residency of the investors. The FDIU has begun this process for some of the well-known Egyptian shareholders who are residents in other economy.

As regards the compilation of FDI flows by industry, the International Standard industry Classification Rev 4 (ISIC4) has been integrated in the compilation system developed by GAFI to produce inward statistics by industry in line with international recommendations. At the start of 2017, GAFI began to help the CBE with the allocation of FDI to activities. Prior to this help, the unallocated share was about 38%, but this fell to only 7% in FY 2017/18 with the assistance from the FDIU and further to 3% in the first quarter of FY2018/19. This highlights the potential benefits from cooperation between the CBE and the FDIU in the compilation of FDI statistics and that these benefits are not limited to improved position statistics but could also improve FDI transaction statistics as well.

The system is supported by an internal business registration database where all direct investment enterprises are registered. In addition to the information sourced from the financial statements of direct investment enterprises, the system will also use financial information on all the current Production Sharing Agreements (PSAs) on upstream exploration companies provided by the Ministry of Petroleum and information on real estate transactions from the CBE’s ITRS. In addition, GAFI has completed a protocol with the Egyptian Financial Services Authority that will enable the coverage of the non-bank financial sector by providing information from their database of companies.

The response rate for the top 500 firms included in the sample is around 84% annually. In 2016, 2,529 companies'13 financial statements were included in the sample, representing 8% of the firms, but 80% of the total capital of the population and 90% of the direct investment position. The mandatory nature of the data collection method (in Egypt, companies are required by Law to report their financial statements to the GAFI and other government authorities) helps to ensure high response rates. In addition, GAFI contacts companies directly when information from their balance sheets is missing or incomplete, which should also improve the response rate.

In terms of valuation methods, the compilation system developed by GAFI uses company financial statements, which is in line with the international recommendations; it will account for the factors missed by the accumulation of flows and, so, will produce better measures of FDI positions. The new system also allows for the compilation of FDI positions according to market values for listed equity positions and according to own funds at book value for unlisted equity positions. Using book values is not recommended because the books can encompass many different valuation methods, especially as the foreign direct investors may be following a variety of accounting methods. While the methods described in BMD4 for estimating unlisted equity can be difficult to implement, there is one method that is accepted as a measure of market value and is widely used by countries--the Own Funds at Book Value (OFBV).

GAFI is further improving its compilation system for both FDI flows and positions. Investment Law No. 72 of 2017 was amended to require firms to submit their financial data on a regular basis. Hence, the FDIU designed annual and quarterly reporting forms to compile FDI statistics in accordance with the recommendations in BPM6 and BMD4. The quarterly form will capture FDI flows while the annual form will be dedicated to capturing FDI positions. An online interface is being developed through which companies will be able to complete and submit these forms. The new approach will enable the FDIU to capture transactions that are not currently captured in the ITRS system, such as some in-kind investments and the part of retained earnings that are not used for capital expansion. Furthermore, data will be collected based on the residency of the investor rather than their citizenship. The FDI flows will be broken down into three components—equity capital, reinvestment of earnings, and intercompany debt—and positions will be broken down between equity and debt. In addition, sectoral and geographical breakdowns will be available.

Recommendations for further improving FDI statistics in Egypt

Currently, Egypt is disseminating FDI statistics under BPM5, and disseminates those statistics in line with timeliness recommendations of the IMF starting 1st of October 2019. The use of the new system developed by GAFI in the compilation of FDI statistics as part of the IIP would increase the quality of the statistics by closing gaps and following the latest international standards with no loss of timeliness. It would also enable Egypt to participate in the IMF’s CDIS.. The use of the new system will also imply that significant efforts be dedicated to assist users understanding the possible significant revisions to the FDI series compared to what is currently published by the CBE. While the use of the new system developed by GAFI offers significant benefits in terms of higher quality FDI statistics, the need for cooperation between the different agencies, and particularly the FDIU and CBE, in compiling and disseminating FDI statistics poses threats to the quality of the statistics.

This leads to the first, overarching, recommendation: it is important that the agencies work together to ensure that the statistics compiled and disseminated by each agency are consistent with each other; this could mean, for example, producing a joint release and analysis of the FDI statistics. In addition, it is important that the statistics are perceived as objective by users.

The second key recommendation relates to improving alignment with the international standards. Items under this recommendation include: clarifying the treatment of SPEs within FDI statistics and exploring the feasibility of separately identifying FDI associated with SPEs in the statistics disseminated based on their identification within the source data; working to populate the information on residency so that the statistics can be compiled based on residency rather than citizenship; using the directional principle (or extended directional principle once information on the UCP is available) and the debtor/creditor principle for presenting the detailed statistics by immediate partner country and industry; and continuing to provide training in FDI concepts to staff as well as in related topics such as statistics, modelling, and the financial analysis of companies, to provide adequate IT resources, and to cooperate with the IMF's Middle East Technical Assistance Centre if possible.

The third recommendation is to improve the accessibility and usefulness of the FDI statistics to data users. Items under this recommendation include: providing more information on the overall response rate obtained from financial statements and on the comprehensiveness of the information collected to users so that they can evaluate the overall quality of the system; posting a methodology explaining the data sources, estimation methods, and any deviations from the international guidelines on the website; releasing an analysis with the release of the FDI statistics to help users better understand and interpret the statistics; ensure the accessibility of longer time series as well as detail by instruments for all series on the website; and consider creating a section on the website dedicated to the detailed annual FDI statistics by partner country and by industry.

The final recommendation is to explore further enhancements to the statistics. One of the most useful enhancements is the presentation of inward FDI position statistics by ultimate investing country, which should be feasible using the information from the new system, complemented by additional information for cases that may be more challenging than others. GAFI should also explore the possibility of publishing supplemental FDI series, such as on greenfield investment, as well as the possibility of publishing some economic variables, such as the turnover or capital expenditures, of FDI enterprises. However, Egypt should first focus on disseminating timely FDI positions and flows by immediate counterpart partner country that are in line with the international standards. Currently, only increases in liabilities are available by partner country while FDI positions are currently not disseminated by partner country.

Measuring participation in global value chains: Concepts and definitions

The flows of goods and services within global production chains are not always reflected in conventional measures of international trade. The international fragmentation of production has weakened the interpretability of trade data as intermediate goods and services cross borders several times on the way to their final destination. This is referred to as the double (or multiple) counting problem of international trade statistics.

Measuring Trade in Value-Added (TiVA) addresses this issue by considering the value added by each country in the production of goods and services that are consumed worldwide. This has led to the development of TiVA statistics providing new insights on GVCs, notably the OECD-WTO TiVA database.

For country coverage purpose, this chapter uses the UNCTAD EORA-GVCs database to measure Egypt and other MENA countries participation in GVCs. The database provides the following measures:

Foreign value added (FVA) indicates what part of a country’s gross exports consists of inputs that have been produced in other countries. It is the share of the country’s exports that is not adding to its GDP.

Domestic value added (DVA) is the part of exports created in-country, i.e. the part of exports that contributes to GDP. The sum of foreign and domestic value added equates to gross exports.

GVC participation indicates the portion of a country’s exports that is part of a multi-stage trade process, by adding to the foreign value added used in a country’s own exports, referred to as backward participation, and the value added supplied to other countries’ exports, referred to as forward participation. Forward participation captures the extent to which a given country’s exports are used by firms in partner countries as inputs into their own exports.

The UNCTAD EORA-GVCs database draws upon information from a variety of primary data sources, principally on national Input-Output Tables. To deal with missing data, interpolation and estimation techniques are used. The database should be therefore used with some caution when interpreting results for data-poor countries.

Mechanisms of SME participation in GVCs via investment

Indicators in chapter 1 measure the extent and the type of linkages between MNE affiliates and the local economy. The indicators focus exclusively on the manufacturing sector and quantify the extent to which an MNE affiliate in a country purchases locally-produced intermediate inputs and how much it generate a market for intermediate goods produced by local businesses.

A backward linkage exists when SMEs purchase goods or services from foreign MNEs established domestically. A forward linkage exists when SMEs supply goods or services to foreign MNEs established domestically. Thus, basic SME integration in GVCs from the lens of investment can be considered as a complementary concept to a broader framework, focusing on SME participation in GVCs via trade. This investment channel could become a trade channel if inputs sold to foreign MNEs established domestically and these MNEs further process these inputs and then export.

SMEs can upgrade in GVCs through specific partnerships with foreign MNEs. From the lens of investment linkages, SME upgrading in GVCs is expected when stronger relationships, beyond just arm's length trade, with foreign MNEs are established (Figure below, bottom box). On the one hand, this may involve specific contractual arrangements with MNEs, such as supply/manufacturing agreements, licencing, R&D agreements, technology transfers, skills development, and quality support. On the other hand, supply chain linkages may be upgraded when SMEs receive inward FDI (partial or full acquisitions from foreign MNEs). Upgrading may involve getting better at producing goods, moving to different tasks within the value chain, or changing the activity altogether. It may also involve the development of improved managerial skills, compliance with international standards, innovation and improved working conditions and more sustainable production.

Annex Figure 1.A.1. Mechanisms of SME participation in GVCs via investment