This chapter analyses the investment promotion and facilitation policies in place in Egypt, examines the institutional framework for investment promotion and facilitation, with a particular focus on the role and activities of GAFI, highlights key reforms and measures implemented by the government to attract foreign investment and improve the business environment and also identifies remaining challenges and proposes recommendations to address them.

OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Egypt 2020

Chapter 4. Investment promotion and facilitation

Abstract

Summary and policy recommendations

Investment promotion and facilitation policies can support a country’s competitiveness of by branding it as a profitable investment destination, attracting quality investors and making it easy for businesses to establish or expand their operations. These measures can not only support the creation of an attractive economy but also help ensure that foreign investments generate positive spill-overs through the development of poorer areas, linkages with domestic companies and skills transfer. It is important that these efforts complement – and do not replace – measures to ensure a sound investment policy framework.

In Egypt, the new Investment Law from 2017 demonstrates the high priority that the government places on promoting and facilitating private investment. The law’s most notable features are the creation of Investors Services Centres supporting the establishment of new businesses and the implementation of an investment incentives’ regime aiming at promoting local development in poorer regions of the country. Investment promotion instruments have also been put in place, such as the Investment Map – an innovative and interactive software to present investment opportunities by sectors and locations.

The General Authority for Investment and Free Zones (GAFI) is a large investment promotion agency (IPA) in charge of investment policy, promotion and facilitation. It was under the authority of the Ministry of Investment and International Co-operation (MIIC) until December 2019, when it was brought under the authority of the Prime Minister. GAFI’s investment facilitation and policymaking mandates are well-developed but could have a tendency to overshadow its investment attraction efforts. The country looks to promote increased levels of foreign direct investment (FDI) but lacks a clear, nationwide and well-articulated strategy to do so. In the business community, GAFI has the reputation for being a responsive and problem-solving organisation, but co-ordination among key public agencies and ministries can be improved.

Policy recommendations

Prepare a high-level investment policy statement to present the investment landscape in Egypt and its vision for FDI, highlight key government orientations and business climate reforms, and showcase the country’s commitment to private investment;

Supplement it with a well-articulated investment promotion strategy providing targets, tools and indicators to guide GAFI’s investment promotion and facilitation activities and ensure that FDI attraction is well-aligned with national development objectives;

Building on these strategic efforts, improve institutional co-ordination mechanisms on investment promotion and facilitation and clarify the roles and responsibilities of relevant ministries and implementing agencies;

Consider strengthening the separation between GAFI’s policymaking responsibilities and its promotion and facilitation tasks or dividing the agency into two distinct entities– one in charge of negotiating treaties, regulating investment and reviewing applications, and the other responsible for investment promotion and facilitation.

Build on the notable efforts to brand the country and guide potential investors to existing opportunities through the Investment Map to gradually conduct systematic investor outreach and targeting activities to attract quality investments that can support sustainable and inclusive development.

Continue and strengthen the monitoring and evaluation of the functioning and the performance of the Investors Services Centres to ensure, on the one hand, that investors are satisfied and, on the other, that the centres provide value for money;

Pursue efforts to systematically revise existing administrative procedures and requirements to start and operate a business with a view to eliminating those which are deemed redundant or unnecessary; and

Building on the recently established monthly public-private sector meetings at the MIIC, establish a whole-of-government public-private dialogue platform to instigate an environment of trust between the government and the business community. Use it systematically to consult with the private sector, to seek business representatives’ views on the main challenges to address, and to discuss government priorities and reforms.

The institutional framework for investment promotion and facilitation in Egypt

A network of public agencies with GAFI as the main national IPA

Recognising the importance of private investment for economic and social development, most countries in the world have established IPAs dedicated to promoting and facilitating investment, often with a particular emphasis on attracting multinational enterprises (MNEs) and capturing the benefits of FDI.

In the vast majority of countries, IPAs are major players in the implementation of four core functions:

image building consists of fostering the positive image of the host country and branding it as a profitable investment destination;

investment generation deals with direct marketing techniques targeting specific sectors, markets, projects, activities and investors, in line with national priorities;

investment facilitation, retention and aftercare is about providing support to investors to facilitate their establishment phase as well as retaining existing ones and encouraging reinvestments by responding to their needs and challenges; and

policy advocacy includes identifying bottlenecks in the investment climate and providing recommendations to government in order to address them.

While the first two functions relate to investment promotion (i.e. marketing a country or a region as an investment destination and attracting new investors), the latter two deal with investment facilitation (i.e. making it easy for investors to establish, operate and expand their existing investments) (Novik and de Crombrugghe, 2018). Investment promotion is meant to attract potential investors that have not yet selected an investment destination, whereas facilitation starts at the pre-establishment phase, when an investor shows interest in a location. As such, and as will be explained below, investment promotion and attraction is primarily the business of IPAs while facilitation is not limited to IPAs and involves a whole-of-government approach.

Large differences exist among IPAs in terms of institutional settings, governance policy, strategic priorities, and investment promotion tools and activities. The way governments around the world organise their institutional framework for investment promotion and facilitation responds to their policy objectives and the priority they give to investment. These choices can greatly influence their success in attracting investment in the most efficient and effective manner.

The investment promotion landscape in Egypt is dominated by GAFI, which is the leading public agency in charge of investment promotion, facilitation and regulation. GAFI is a large organisation with numerous mandates that go beyond the scope of investment promotion and facilitation. It is the operational arm of the government and its main action is based on five major pillars:

1. Attraction, reinvestment and expansion of foreign investment;

2. Stimulation of domestic investment;

3. Development of investment services;

4. Management of free zones and development of investment zones to accelerate the expansion of competitive strategic clusters; and

5. Institutional support to entrepreneurship development and stimulation of innovation development.

Although GAFI is the main national IPA in Egypt (see section below for a more detailed analysis), other parts of the government are, in one way or another, involved in investment promotion and facilitation activities. The Ministry of Trade and Industry – particularly the Industrial Development Authority (IDA), one of its main executive arms – is active in promoting FDI in Egypt’s industrial sectors, notably through the development of industrial zones (see Chapter 5 on zone-based policies). With the authority over industrial land – and access to land being a major recognised investment climate challenge – the IDA has a key role to play in the country’s investment attraction strategy.

As GAFI is responsible for free zones, investment zones and technology zones, a relatively artificial division of labour has been established between the two ministries to oversee the development of zones and the promotion and facilitation of investment into these zones. Some promotional activities are duplicated, which is not efficient in terms of government resources nor beneficial in providing a clear message to investors. GAFI and IDA are seeking to co-ordinate on investment projects, especially those inside industrial zones, but these two agencies would have an interest in co-operating more closely in order to rationalise resources and to conduct a more efficient investment promotion strategy. In this regard, GAFI’s recent affiliation to the Egyptian Council of Ministers (Prime Minister Decree 38/2020) is expected to enhance effective co-operation with all the government bodies involved in investment promotion and facilitation.

The General Authority for the Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCZA) is another important actor involved in investment promotion and facilitation in a strategic location of the country. The SCZA has the mandate to manage and promote the SCZone, through state-of-the-art facilities and services as well as a variety of financial and non-financial incentives for investors willing to set up in the SCZone. It has executive powers of regulation and approval – including the full authority to oversee all areas of operation, staffing, budget and funding, partnerships with developers and business facilitation services. Relevant ministries are also part of the SCZA’s board.

GAFI’s organisational characteristics

In the context of the EU-OECD Programme on Promoting Investment in the Mediterranean, Egypt recently participated in a survey of IPAs conducted by the OECD (Box 4.1). The results serve as the basis of some of the comparative analysis conducted in this chapter, which benchmarks GAFI against its regional peers and against agencies from other regions.

Box 4.1. The OECD-IDB survey of investment promotion agencies

The OECD and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) have partnered to design a comprehensive survey of IPAs. The questionnaire provides detailed data that reflect the multiple recent policy developments as well as rich and comparable information on the work of national agencies in different countries.

In 2017-2018, the survey was shared with IPA representatives from 32 OECD and 19 Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) countries. In 2018, 10 national agencies from the Mediterranean (MED) region participated in the same survey, which was displayed in the form of an online questionnaire and divided into nine parts:

Basic profile;

Budget; Personnel;

Offices (home and abroad);

Activities;

Prioritisation;

Monitoring and evaluation;

Institutional interactions; and

IPA perceptions on FDI.

The results of the survey are gathered and presented in comprehensive IPA mapping reports, which provide a full and comparative picture of IPAs in selected regions. The reports are benchmarking agencies against each other as well as the average IPA in a region against other regions.

Objectives and mandates

IPAs can be either fully dedicated to investment promotion and facilitation – and exclusively focus on the four core functions mentioned above – or be part of a broader agency that includes additional mandates, such as the promotion of exports, innovation, regional development, outward investment and domestic investment, among others. In practice, most IPAs around the world have multiple mandates and conduct activities that go beyond inward foreign investment promotion. In OECD economies, the most frequent combination of mandates in IPAs are with export promotion (56% of agencies) and with innovation promotion (same percentage) (OECD, 2018a).

GAFI reported in its responses to the IPA survey to have 9 official mandates (out of 18 possible mandates):

1. Inward foreign investment promotion;

2. Outward investment promotion;

3. Domestic investment promotion;

4. Operation of one-stop shop;

5. Screening and prior approval of investment projects with foreign participation or investor registration;

6. Negotiation of international trade, investment and other agreements;

7. Management of special free zones and investment zones;

8. Granting fiscal incentives; and

9. Granting non-financial incentives.

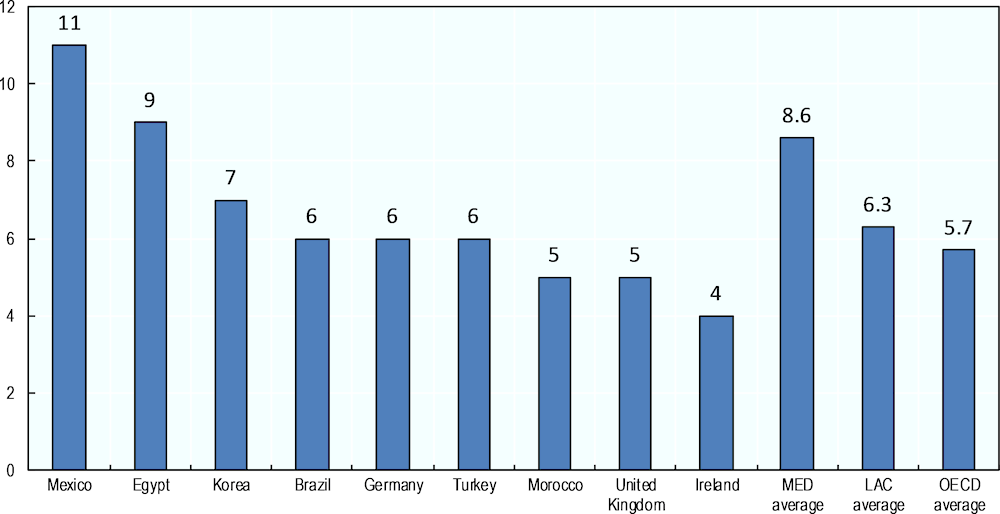

Although large differences exist across agencies, including within the same regions, IPAs in OECD countries as well as in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) have generally fewer mandates, with an average of 5.7 and 6.3 different mandates respectively under the agency’s responsibility (Figure 4.1). GAFI’s total number of mandates is nonetheless overall in line with the average for the Mediterranean (MED) region of 8.6 mandates.

Figure 4.1. Number of mandates of GAFI and selected other national IPAs

Source: Based on OECD (2018a), OECD (2019) and Volpe Martincus and Sztajerowska (2019).

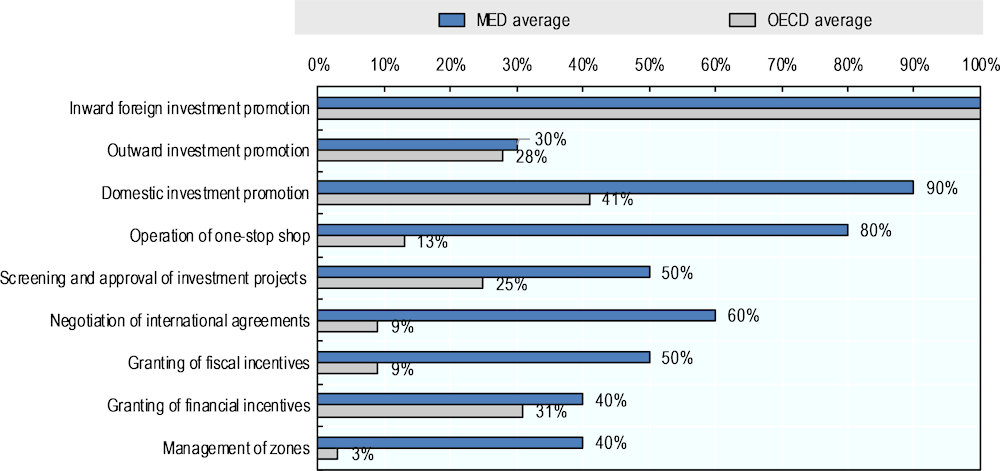

GAFI’s number of mandates reflects its wide scope of responsibilities and activities, which are strongly articulated around investment, both domestic and foreign, as no other policy area (such as export promotion, which is often combined with investment promotion) is included in GAFI’s official mandates. This reflects the importance of investment in Egypt’s overall development policy and demonstrates a coherent approach to making investment work for growth and prosperity – notably by including foreign investment promotion, domestic investment promotion and the operation of a one-stop shop under the same umbrella. While this is often the case in MED agencies, it is less frequent across IPAs in OECD countries (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2. GAFI’s mandates and their frequency across MED and OECD agencies

Source: Based on OECD (2018a) and OECD (2019).

It is not a common practice in IPAs to combine regulation and promotion of investment under the same roof, however, and there might be a risk of mixing the two. Some studies show that those IPAs focusing exclusively on investment promotion achieve significantly higher results in attracting investors than those which carry out both regulatory/administrative and promotional activities (World Bank, 2011). The reason behind this finding is that attracting FDI and ensuring that investors comply with legal requirements are two different functions with different objectives and that require different skillsets. Investors contacted by the IPA may wonder whether it is intended to solve their problems or to create new ones. The IPA is often expected to represent private investors’ interests within government and it will be less credible to do so and to influence policymaking if it is the same agency that regulates them.

A long-term alternative would be to divide GAFI into two separate entities – one in charge of negotiating treaties, regulating investment and reviewing applications, and the other responsible for investment promotion and facilitation. If this option is considered, the policy part of GAFI would operate as a ministry and its promotion part could increasingly take more autonomy from it. The fact that GAFI has now been moved under the prime minister’s responsibility is an opportunity to make this distinction clearer and operational. In most countries, especially in the OECD area, the ministry in charge of investment is responsible for policymaking and, if appropriate, other regulatory aspects such as reviewing investment proposals and monitoring companies’ projects. Meanwhile, the IPA is more autonomous from the ministry, sometimes with private sector participation, seeking to find a balance between following the government’s strategic orientations and representing the views of investors. This consideration directly relates to GAFI’s legal status and governance policy, examined below.

Governance policy

The governance of an IPA relates to the way it is supervised, guided, controlled and managed. IPAs’ governance policies are often dictated by their institutional contexts and broader political choices. It affects their legal status, reporting lines and managerial structure, including the role of their board in case they have one.

IPAs can usually be created as: i) part of a ministry; ii) an autonomous public agency; iii) a joint public-private body; or iv) a fully privately-owned organisation. GAFI belongs to the second category, as it is an autonomous public agency (reporting to the MIIC until the end of 2019 and now to the prime minister). Autonomous public agencies are the most common forms of IPA legal status according to the IPA surveys conducted by the OECD. All IPAs in the MED region and 60% of those in the OECD are autonomous public agencies (OECD, 2018a and 2019). Across OECD agencies, the second most frequent legal status – just below a third – are governmental IPAs (part of a ministry) and the remaining 9% are private or semi-private.

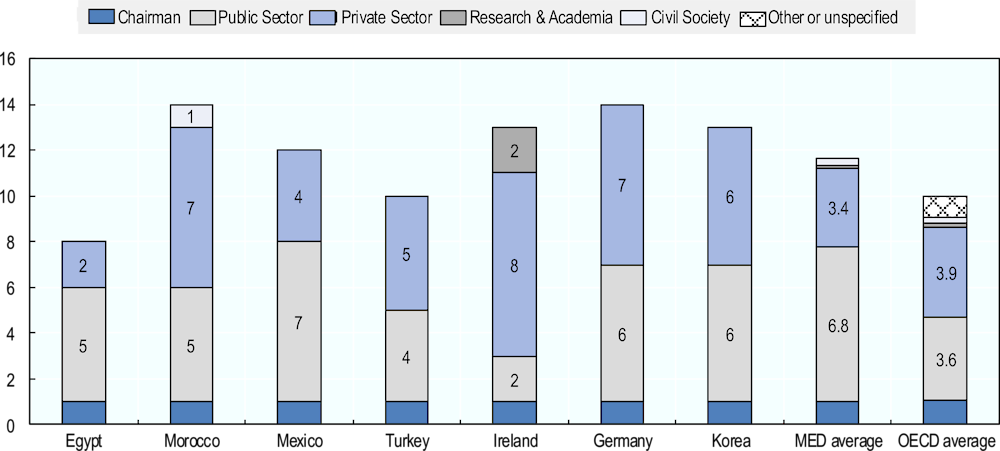

A key component of an IPA’s governance policy is the existence and role of a board. When a board exists, it is meant to supervise or advise the work of the agency, or both, with an independent perspective. Boards vary greatly from one IPA to another; they can be of advisory nature or with a high degree of decision-making power. GAFI’s board has changed quite frequently over the past years and has often been limited to a few members. In 2017, the board was reformed in line with the provisions of the Investment Law and has since then been composed of eight members, six of which are from the public sector (including two from GAFI’s senior management), and two from the private sector.

Having private sector representatives on the board is a positive initiative, as it ensures that the views and interests of businesses are taken on board in GAFI’s broad strategic directions. But it should not be taken for granted that the perspective of the private sector is fully or necessarily represented in all of GAFI’s decisions, as it is difficult for a few individuals to represent the views of all companies, given their diversity in terms of economic sector, size, geographic location and specific contexts and challenges. As a matter of comparison, in OECD IPAs, boards are often larger (around ten people on average) and members include just below 40% of private sector representatives on average – the remaining being representatives of the public sector, research and academia, civil society or other areas. In MED agencies, public sector members tend to dominate but the private sector is often well represented – proportionally more than in Egypt (Figure 4.3). Other stakeholders, including from civil society or academia, could also be represented in GAFI’s board – as in the case of some OECD and MED agencies – to help better address their concerns in the agency’s activities. More importantly, having private sector representatives in the board should not substitute for wide and systematic private sector consultation platforms and mechanisms (see section 3 below on facilitating investments and reinvestments).

Similarly, in most other IPAs – both in MED and OECD countries – public sector members of the board come from other ministries and government agencies, not only to provide complementary skillsets to the strategic decision-making but also to allow for smoother inter-institutional co-ordination. GAFI could consider expanding its board to integrate new members from other ministries and agencies, which would help better align and co-ordinate its activities with other parts of government.

Figure 4.3. Board members in GAFI and selected other IPAs

Source: Based on OECD (2018a) and OECD (2019).

Promoting and attracting investment: strategy and tools

To attract FDI in support of national economic objectives, a government first needs to design a clear and well-defined strategy to provide an overall direction, with specific targets and means to achieve the set targets. Depending on the government’s objectives, three different types of investment strategies exist:

1) National policy statements on investment, which present and describe the investment landscape and the government’s strategic orientations;

2) Investment promotion strategies that define the government’s main targets, tools and performance indicators to attract inward foreign investment; and

3) Comprehensive investment strategies that outline in an action plan the government’s objectives and reform plans to foster investment and the roles and responsibilities of all relevant government bodies.

Annex 1.A provides a comparative overview of these different strategies, which could help the government of Egypt in its future investment strategy making. It is recommended that the authorities prepare both an overarching policy statement on investment, to give broad orientations to its institutions and a clear vision to the international business community, and a more-focused investment promotion strategy to guide GAFI in its activities and ensure they are well-aligned with national development objectives.

Preparing a high-level investment policy statement

Governments often prepare an investment policy statement prior to the design of – or in parallel to – a more detailed and specific investment promotion strategy. As explained in Annex 1.A, investment policy statements are meant to present the institutional and regulatory landscape for investment in the country as well as the government’s strategic orientations and measures to foster investment. Investment policy statements aim to demonstrate a political commitment in favour of private investment. They are relatively short and meant to be widely disseminated, including among the international business community.

Box 4.2. Ireland’s 2014 FDI Policy Statement

The Policy Statement on Foreign Direct Investment in Ireland was published by the Irish Department of Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation in July 2014 under the authority of the former Minister. It was released halfway through the government’s term (2011-16).

Its purpose is to take stock of the foreign investment policy implemented during the past three years (and sometimes beyond) and to highlight recent achievements and ongoing reforms. It also presents the government’s strategic vision for 2014-20 by identifying areas for improvement, but without providing a detailed set of measures to be adopted. To justify these strategic choices, the statement brings to the fore some empirical research work on the impact of investment policies on the economy. An overview of this strategic vision is given through the minister’s foreword, which indicates that this policy was designed through a whole-of-government approach to create quality jobs and improve the quality of life of the Irish.

The Policy Statement includes an introduction that describes global investment trends, Ireland’s performance in attracting FDI and its contribution to the national economy. The overarching objectives of this FDI strategy are also presented and include the necessity to create employment and enhance national productivity. The strategy aims to contribute to the development of key industrial sectors through the creation of ecosystems and to enable access to global value chains for Irish-owned enterprises. Amongst its objectives, three strategic elements are identified in the strategy:

1. identifying promising sectors based on the Irish industry’s strengths;

2. identifying strategic FDI source markets; and

3. facilitating different modes of investment, including greenfield investments, mergers and acquisitions and partnerships with research institutions.

The document identifies strategic policy enablers to reach these objectives: fostering Ireland’s key differentiators (human resources, R&D and urban planning); developing sectoral ecosystems; preserving a competitive tax system and maintaining business cost levels; developing infrastructure; and guaranteeing the access to real-estate. For all dimensions, a stocktaking of reforms is made. Actions to be implemented are also identified for each area, although they remain rather general, as they do not provide precise details on the way these actions should be put into effect.

Finally, the Policy Statement briefly presents IDA Ireland, the Irish IPA. It describes its mandate and those from related national agencies such as Enterprise Ireland and the Science Foundation Ireland and recommends the development of a new strategy in line with this FDI Policy Statement.

The example of Ireland is particularly enlightening, as the complementarity and usefulness of both its Policy Statement on Foreign Direct Investment and its investment promotion strategy (Winning: Foreign Direct Investment 2015-2019) are very clear. Ireland’s policy statement takes stock of past reforms, paves the way for future actions and reflects the government’s willingness to put FDI at the heart of economic development (Box 4.2). It also recommends the development of a new investment promotion strategy, which was subsequently designed and is more operational and specific, as it lays down the country’s investment opportunities and targets as well as its value proposition – from both a national and sub-national perspective.

The Egyptian authorities should consider preparing and disseminating a national policy statement on investment, as this is the most overarching option and would allow the government to translate its vision into investment objectives and priorities while providing overall guidance to implementing institutions. In line with MIIC’s report on “Investing in Development for the SDGs” (2018a), the national policy statement would be an opportunity to demonstrate the government’s commitment to foster investment but also to showcase the economy’s openness to FDI, as reiterated in the new investment law. Recent and upcoming reforms should also feature in the document, which would provide a positive signal to potential and existing investors and help raise Egypt’s profile among the international business community.

Disseminating the national policy statement would also provide overarching guidance for the authorities to prepare more detailed roadmaps and strategic documents, including GAFI’s investment promotion strategy, but also in-depth sectoral strategies and a national investment reform action plan that involves all parts of government.

…together with a well-articulated investment promotion strategy

An investment promotion strategy is a more focused and operational policy tool, usually designed by or for the national IPA. It should focus on inward foreign investment and define the major objectives, tools and activities to attract investment, including specific targets and performance indicators to evaluate success, priority sectors and countries for FDI attraction, and the role and responsibilities of the IPA and other agencies to support these objectives or targets.

Investment promotion strategies are prepared to ensure that promotion efforts are well-targeted and contribute to the government’s broader national development objectives. They revolve around the question of what to promote (i.e. sectors, countries, projects, investors) and how to implement this promotion in practice. They should rely on a solid evaluation of the economy’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT), as there is a risk associated with focusing on specific sectors or picking winners if these decisions are made based on political agendas rather than on carefully crafted economic rationales.

Virtually all IPAs target some investments over others in performing their functions, even without a clear investment promotion strategy in place. According to the OECD survey of IPAs in the MED region, GAFI seems to have well-focused investment promotion activities, as the agency selects sectors, countries, projects and investors in its FDI attraction efforts. Across IPAs in the OECD, only 41% combine these four layers of priorities (OECD, 2018a). Across MED agencies, the majority prioritise countries (90%), sectors (90%) and projects (70%), but Egypt is the only one to also prioritise investors (OECD, 2019).

Prioritising sectors, countries, projects and investors should be conducted according to a set of well-defined criteria in line with national development objectives. The way Egypt selects its criteria for prioritising investment projects, for example, reflects its desire to maximise the potential impact of FDI on society, including with criteria such as the impact of investment projects on jobs, wages, exports, innovation and regional development (Table 4.1). GAFI is interestingly one of the few agencies not to consider the size of investment when prioritising investment projects.

Table 4.1. Criteria used for prioritisation of investment projects by GAFI and selected other IPAs

|

Egypt |

Morocco |

Turkey |

Mexico |

Poland |

UK |

Ireland |

Korea |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Priority Sector |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Priority Country of Origin |

√ |

√ |

||||||

|

Mode of Entry |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|||||

|

Size of Investment |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

|

Investment Horizon / Duration |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|||

|

Type of Investor |

√ |

√ |

||||||

|

Size of the Company |

√ |

√ |

||||||

|

Nationality of Investor |

√ |

√ |

||||||

|

Company’s Engagement in FDI |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|||

|

Impact on Job Creation |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Impact on Wages |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|||||

|

Impact on Exports |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

|

Impact on Innovation |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

|

Impact on Regional Development |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

|

Impact on Tax Revenue |

||||||||

|

Impact on Country’s Image |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|||||

|

Impact on Local Firms’ Capacities |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|||

|

Impact on Competition |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|||||

|

Sustainability |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

Source: Based on OECD (2018a and 2019).

Priority sectors for economic development are presented in Egypt 2030, but a more specific list of priority sectors and industries for investment – notably FDI – has not been clearly identified. GAFI and the IDA (under the Ministry of Industry and Trade) have each established their own lists of sectors, which seem to be based on a politically negotiated split. GAFI identified labour-intensive, export-oriented, and research and development (R&D)-oriented sectors for FDI promotion, which could potentially include any sector. The Investment Law targets the following industries: renewable energy; tourism; automotive; wood, packaging and chemicals; pharmaceuticals; food and agricultural products. Key industrial sectors identified by IDA include chemicals, engineering, textiles/ready-made garments, food, and building materials – which are not so different from those identified by the Investment Law.

According to GAFI’s senior management, an investment promotion strategy is in place but not publicly available or shared internally with other ministries or public agencies. The strategy is said to be based on Egypt 2030 and aimed at guiding GAFI’s overall activities, but it does not include detailed investment promotion targets and indicators. It is important that the investment promotion strategy and its main features are developed in co-ordination with other key ministries as investment priorities need to be aligned with other major policy strategies – including trade, innovation, industry and skills. Additionally, making GAFI’s investment promotion strategy publicly available would not only support inter-governmental co-ordination, but would also help raise Egypt’s positive image within the international business community and inform it about priority sectors and investment opportunities.

The investment promotion strategy should also be very clear and specific about the targets as well as the tools and performance indicators to reach the set targets. It should provide clear indications on how to implement it, i.e. how the staff should be organised internally, what are the main activities it should focus on, what are the key performance indicators to measure outputs and outcomes, and the collaboration mechanisms in place to work with other relevant public agencies and stakeholders (e.g. the private sector).

Implementing investment promotion tools and activities

GAFI is organised by geographic locations and specific investment promotion activities are conducted accordingly by the agency’s different teams. Proactive investor targeting and lead generation activities remain relatively limited, as GAFI is focusing on branding the country as an attractive investment destination, providing information to interested investors, helping them establish (i.e. see below the Investors Services Centres) and supporting those that encounter problems. The agency also recently established a unit dedicated to domestic investment promotion.

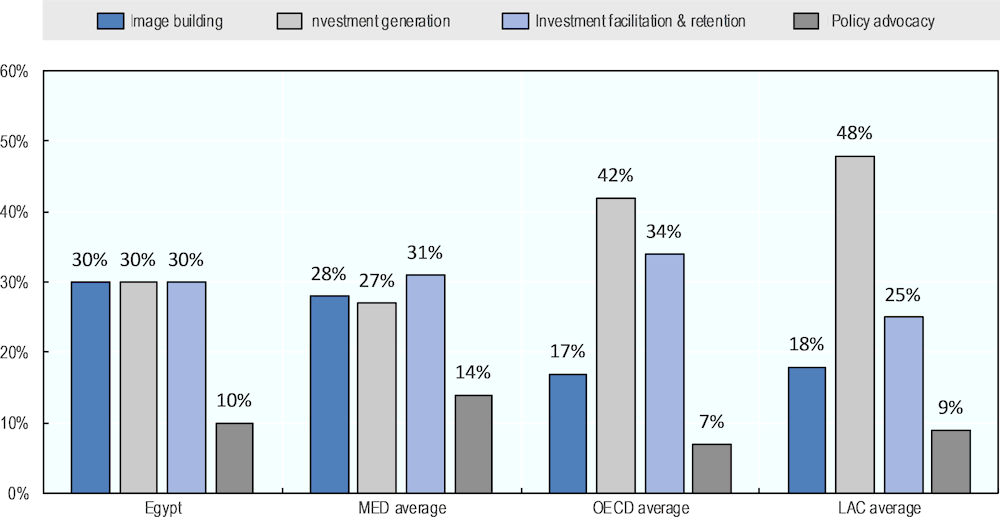

The 2017 Investment Law provides little information on the four IPA core functions described above, particularly those relating to investment promotion and attraction. According to the OECD survey of IPAs, GAFI allocates its employees equally to image building, investment generation and investment facilitation and retention activities (30% of staff each). Figure 4.4 shows that this estimated share for image building, similarly to the MED average (28%), remains much higher than in the OECD and LAC regions (17% and 18% on average respectively).

Figure 4.4. Estimated use of staff across the four investment promotion functions in GAFI and in the average IPAs of selected regions

Source: Based on OECD (2018a), OECD (2019) and Volpe Martincus and Sztajerowska (2019).

Conversely, the estimated percentage of staff dedicated to investment generation is slightly higher than the MED average (27%), but significantly lower than the average for OECD and LAC countries (42% and 48% respectively). This reflects the fact that agencies from more advanced countries usually use fewer resources to work on branding or improving their country’s image and dedicate most of their promotion efforts to more focused FDI attraction and generation activities. The investment facilitation and retention function is more homogeneous across regions. Its relatively high estimated share in Egypt reflects the importance of the Investors Services Centres in GAFI. Policy advocacy is another function that is relatively similar across Egypt and the three regions.

One of GAFI’s new investment promotion flagship instruments is the Investment Map, launched in February 2018. This tool presents, on an interactive map of Egypt, different investment opportunities by sectors and geographic locations, including those in all the different zones, and provides information on existing utilities, the distance to ports and airports, and other logistical information (Box 4.3). It is a horizontal tool by nature and serves the purpose of different functions, notably image building, investment generation and investment facilitation. The Investment Map also reflects improved co-ordination efforts by the government, as investment opportunities from all sectors and in all types of zones are centralised in this tool. Having a single entry point for investors makes it both more efficient for the Egyptian authorities and more helpful for investors to make fully informed investment decisions.

The Investment Map can thus prove a very useful tool for prospective investors. It testifies to how to best use knowledge sharing and information dissemination as catalysts for investment. Focusing investment promotion efforts on specific, ready-made projects is common in other countries and regions, and can constitute a good selling point for some specific investors, but targeting should not be limited to this practice, as most businesses appreciate flexibility as to where and how their investments will be channelled.

Box 4.3. Egypt’s Investment Map

To overcome potential information gaps on investment opportunities in Egypt, the MIIC introduced an Investment Map that provides a comprehensive view of the many investment opportunities across the country. In order to encourage new projects and business opportunities, the map allows any potential investor to search and discover opportunities by geographical location and economic sector as well as all major national projects including the mega projects. The map also outlines all the different zones and incentives, including industrial, investment, technology and free zones, in addition to development projects categorised by the relevant development partners. The map provides investors with case studies and information about other investors operating within the market.

The first phase of the investment map was finalised in 2017, including the design, structure and data collection for the map. The final format of the map provides the user with a 360-degree image of all investment opportunities. Upon choosing and selecting a potential opportunity, a short description of the project is provided, in addition to the main information and statistics about the governorates in which it is situated (such as land area, employment rate, etc.). The map also indicates the main utilities surrounding the projects, such as airports, ports, hospitals, universities, technical centres, governmental services and touristic locations. The map specifies the type of contract for the project (rent, holding, usufruct, etc.) and the relevant governmental entity to contact.

The second phase of the map is completed. It included the design and implementation of a management system that ensures the sustainability of the portal. The system provides access to governorates and relevant authorities to collaborate in order to update the data and provide additional investment opportunities.

Source: MIIC (2019).

Additionally, albeit very innovative and informative, the Investment Map remains a simple information portal. Egypt should complement these efforts with more direct marketing techniques to identify and approach potential investors that can support national economic priorities, as laid out in the national investment strategy (see above). Investment generation requires thorough sector-specific knowledge and a good understanding of MNEs’ internationalisation strategies (OECD, 2011). The Egyptian commercial services, which are located in key overseas markets, support the country’s investment generation activities. They are very active in attracting specific investors, including in all types of zones. Given that these services are also mandated to work on trade facilitation, they report to both the Ministry of Trade and Industry and the local ambassador. They have a working relationship with GAFI but no reporting line.

To enhance investor targeting efforts, GAFI’s senior management would also be well advised to consider restructuring its staff according to economic sectors rather than geographic locations, as is the case in most IPAs based in OECD countries. GAFI’s staff members have to be able to grasp companies’ investment location decision processes and identify their requirements long before their investment decision is taken, to effectively respond to their needs and enquiries during their investigation phase and influence their decision making. Strong sector knowledge is a key success factor in such activities.

From a broader investment promotion perspective, the plethora of zones in Egypt play a crucial role in the country’s investment promotion strategy. Many other countries across the world opt for zone-based policies to attract investors, create jobs and increase export earnings. Common features of zones include a geographically defined area and streamlined procedures – such as for customs, special regulations, tax holidays – which are often governed by a single administrative authority. In Egypt, free zones, investment zones and technology zones are under the responsibility of GAFI while industrial zones are under the authority of the Ministry of Industry and Trade. SEZs report directly to the office of the prime minister. Chapter 5 examines in detail the specificities, roles and performance of Egyptian zones.

Finally, the investment incentive scheme constitutes one of Egypt’s major investment promotion tools. The 2017 Investment Law introduced a new incentives’ classification with two categories, A and B, based on three criteria:

1. The geographical location (Suez Canal special economic zone, Golden Triangle special economic zone and other, less developed, regions as determined by a Ministerial Cabinet’s decision)

2. The type of investment (labour-intensive; small and medium-sized enterprises; or export-oriented) and

3. The sector (renewable energy; tourism; automotive; wood, packaging and chemicals; pharmaceuticals; food and agricultural products).

Investments complying with criteria 1 fall under category A (50% discount of the investment costs for a maximum of seven years) and those with criteria 2 and 3 under category B (30% discount of the investment costs for the same amount of time). A detailed analysis of Egypt’s investment incentives scheme can be found in Chapter 6 on Tax Incentives for Investment.

Investment facilitation services and activities

Investment facilitation starts when an investor shows interest in a location. It includes the way enquiries are handled by the relevant authorities, notably the IPA, and measures to reduce potential obstacles faced by investors once they have decided to invest. But investment facilitation does not stop there: encouraging the expansion of existing investors and helping them overcome the challenges they face in operating their business is at least as important as facilitating new investments. Aftercare measures can be influential in companies’ decisions to stay in the country and reinvest, and policy advocacy is a powerful instrument to bolster reforms and enhance the business environment by leveraging the private sector’s feedback.

Starting a business: the Investors Services Centres

One of Egypt’s flagship investment climate reforms is the establishment of the Investors Services Centres (ISC), as promulgated by the 2017 Investment Law. The ISCs were set up to grant the approvals, certifications and licences that are necessary for establishing and operating a company. They are typical examples of what are commonly known as one-stop shops, which consist in placing officials from different government agencies and ministries under the same roof to centralise administrative procedures and requirements for incoming investors. One-stop shops have been established in various parts of the world, often under the IPA and are frequently geared towards foreign businesses.

ISCs in Egypt include full start-to-end services to investors, including services related to establishing companies and their branches, approving the minutes of their boards of directors and their general assemblies, issuing approvals and permits and allocating the necessary real estate for the establishment of projects (MIIC, 2018b). As of September 2019, 10 ISCs had been established and were operating in the country, and ISCs are expected to be established in all 27 governorates. Depending on their level of development and geographic location, each ISC has a different number of external agencies and ministries represented. In Alexandria, for example, 28 other ministries and public agencies were represented in their ISC as of mid-2018. Several ISCs have now reached 66 entities according to government sources. ISCs are also increasingly integrating digital tools for business registration, such as the electronic signature service that enables reducing the time needed for certain procedures. The law also gives the possibility to create private accreditation offices, licenced and registered by GAFI, that deliver all permits. As such, the government seeks to engage the private sector in the licensing process and to expand the possible channels for business registration.

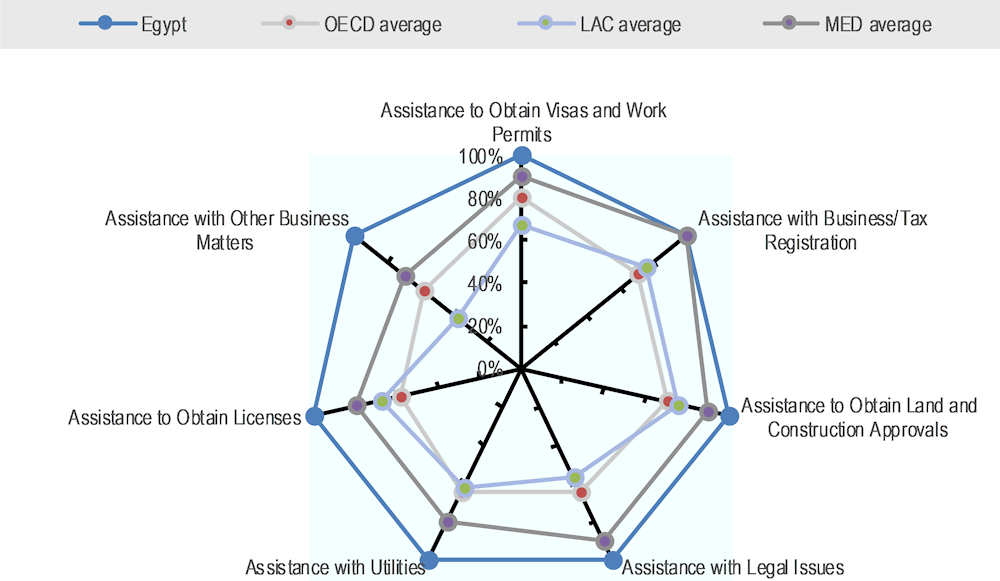

Integrating fully-fledged ISCs under its responsibility makes GAFI a “facilitation-oriented” IPA, offering a wide range of government services to incoming investors. As such, the wide scope of its administrative support services makes GAFI very competitive vis-à-vis other IPAs in the MED region – and even more so vis-à-vis those from OECD and LAC regions (Figure 4.5). The same services that are offered by GAFI are only available in 86% of MED agencies, 67% of OECD agencies and 63% of LAC agencies on average.

Figure 4.5. IPA services aiming to assist investors with administrative procedures in Egypt and in selected regions

Source: Based on OECD (2018a), OECD (2019) and Volpe Martincus and Sztajerowska (2019).

The pros and cons of one-stop shops have been widely debated in the literature and amongst investment promotion and facilitation practitioners. On the one hand, they can significantly reduce transaction costs for businesses if they are fully-functional but, on the other hand, they can become “one-more stop” if officials from external ministries do not have sufficient decision power and full approval authority. They can also prove costly for governments, as they force ministries to duplicate or multiply the number of officials to allow a presence in both their own administration and in the existing one-stop shop offices.

The Egyptian ISCs follow a number of good international practices. Firstly, unlike in some other countries, they are not mandatory entry points for investors, as businesses can opt for alternative routes to open a business if they so wish, which is an incentive for ISCs to remain efficient. It is the quality of its services that should determine the decision of investors to interact with ISCs or to seek for alternative options. Secondly, ISCs are equipped with a Customer Relationship Management system, which includes key performance indicators for monitoring performance. Customers are also invited to fill in satisfaction surveys and forms. Thirdly, the costs of the ISCs seem to be efficiently and equitably shared between GAFI and external ministries, since, according to the authorities, the basic salaries are paid by the relevant ministries while GAFI covers these extra costs thanks to the revenues made out of lending land in the free zones.

ISCs have been generally welcomed by the international business community established in Egypt but more time is needed to evaluate their long-term influence on the business environment. One of the main points is to ensure the licensing decisions can be taken within the ISCs, particularly when a case is not fully straightforward and the approval process is more complex. The decision power of representatives sitting in the ISCs is the key question as it means bearing the responsibility. It is also important that the decisions to grant or refuse a business licence are transparent and made publicly available, with a right of appeal for those investors who have seen their licence rejected.

Starting and running a business: wider measures

The government’s efforts to improve the business environment, especially to facilitate business creation, have allowed the country improve its ranking in the World Bank’s overall Ease of Doing Business. Egypt ranked 114 out of 190 in 2020, improving by six notches from 2019 and by 14 notches since 2018. Similarly, the country improved significantly its ranking in the ‘Starting a Business’ sub-category, from 109 in 2019 to 90 in 2020, which could be largely attributed to the operationalisation of the ISCs. Egypt is gradually reaching the level of some of its peers, especially to start a business, but further efforts are still needed (Table 4.2).

Table 4.2. Doing Business’ score in Egypt and selected other countries, 2018-2020

|

Egypt |

Morocco |

Tunisia |

Jordan |

Turkey |

Mexico |

Indonesia |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ease of doing business (overall) |

2018 |

55.8 |

69.2 |

65.3 |

59.9 |

70.9 |

72.5 |

66.9 |

|

2019 |

58.5 |

71.7 |

67.2 |

61.3 |

75.3 |

72.3 |

68.2 |

|

|

2020 |

60.1 |

73.4 |

68.7 |

69.0 |

76.8 |

72.4 |

69.6 |

|

|

Starting a business |

2018 |

80.7 |

92.5 |

81.6 |

84.4 |

81.9 |

85.8 |

76.1 |

|

2019 |

83.8 |

93.0 |

88.5 |

84.4 |

88.2 |

85.9 |

79.4 |

|

|

2020 |

87.8 |

93.0 |

94.6 |

84.5 |

88.8 |

86.1 |

81.2 |

Note: An economy’s ease of doing business score is reflected on a scale from 0 to 100, where 0 represents the lowest and 100 represents the best performance

Source: World Bank.

While the establishment of the ISCs under GAFI is a valuable initiative to support new investment, it should not substitute for continuous regulatory reform to quicken and simplify the process of starting a new business. Cutting unnecessary procedures and requirements should remain a top priority of the authorities to provide a healthy business environment to both incoming and already-established investors. Private sector representatives also report that administrative procedures and requirements tend to be burdensome at different stages of their business operations, not only at establishment, and that fulfilling these requirements is a major impediment to their expansion and, at times, an incentive to divest. In this light, the Egyptian government recognises the constant need to improve the business environment so that the private sector can effectively contribute to growth and development. The establishment of ISCs are a good step forward, which were followed by a number of procedural improvements in administrative streamlining and business facilitation. The government should ensure that the focus given to ISCs is not overshadowing other necessary efforts to strengthen the capacities of officials dealing with businesses (including in remote governorates), to enhance the transparency in administrative decision-making.

The authorities should continue their efforts to systematically map all required licences, approvals and procedures to do business in Egypt and identify those that should be streamlined. This would help make ICSs even more efficient and useful for investors. International good practices show that countries that have successfully enhanced their business environment have driven reform from the highest-level of government with strong political support; have involved all relevant stakeholders, both public and private, from the beginning of the process; and have established a dedicated taskforce to suggest and monitor reforms.

Post-establishment: consulting and assisting the private sector

The key role of a high-level public-private dialogue

In their continuous efforts to provide a friendlier investment climate, governments should maintain regular dialogue with the private sector in order to involve them in policy design and to collect feedback on recurrent issues affecting their operations.

The private sector is often consulted on an ad hoc basis in Egypt, notably through the Egypt business association, when new laws and regulations are in preparation. This was the case during the preparation of the 2017 Investment Law, where businesses had the opportunity to comment on early drafts. For a long time, however there has not been a strategic or systemic approach to consult the private sector on investment climate challenges or to collect their views on necessary reforms and priority government actions. In 2019, the MIIC and GAFI established monthly meetings with investors attended in person by the minister. Requests or complaints had to be sent in advance and the authorities addressed them in the meetings. Although this initiative reflects the willingness of the authorities to take investors’ concerns seriously and address them, it is too recent to evaluate its impact or effectiveness.

Taking advantage of the new institutional framework for investment, the authorities would be well advised to build on this initiative to reinforce public-private dialogue mechanisms. Meetings should be well-prepared, well-structured and focused on specific topics to make them relevant and constructive. It is also important to invite systematically representatives of relevant ministries and agencies, as investment climate challenges can rarely be solved within a single agency. Such whole-of-government mechanisms have proven extremely useful in other countries to facilitate a constructive and mutually beneficial dialogue. The example of the Vietnam Business Forum demonstrates that holding these public-private dialogue platforms both on a regular basis and with high-level government representation are key ingredients for their success and efficiency (Box 4.4).

Box 4.4. The Viet Nam Business Forum

The Vietnam Business Forum (VBF) was established in 1997 with the support of the World Bank as a not-for-profit, non-political channel for nurturing public-private dialogue to develop a favourable business environment that attracts domestic and foreign private sector investment and stimulates sustainable economic development in Viet Nam. This is done primarily through high profile bi-annual Forums between the business community and Vietnamese leadership and through specialised Working Groups cutting across sectors (agribusiness, automotive, banking, capital market, customs, education & training, governance & integrity, infrastructure, investment & trade, mining, and tourism).

Key VBF objectives include working with the government to create pathways to long-term and sustainable business performance as well as to promote the interests of national and international business community in Viet Nam and enhance investment and trade in local and overseas markets. The VBF works to provide research, legal analysis, identification of problems and practical solutions.

In early 2012, the co-ordination function of the Forum’s secretariat was transferred from the World Bank Group to a Consortium of international and local business associations and chambers of commerce to allow the private sector to play a bigger role in the Forum’s sustainable development. The bi-annual Forums are co-chaired by Viet Nam’s Minister of Planning and Investment, the World Bank’s Viet Nam Country Director, IFC’s Regional Manager for Viet Nam and Co-chairmen of the Consortium. The Consortium is led by five Consortium Members and supported by 11 Associate Members which are foreign and local business associations and chambers of commerce in Vietnam.

Public-private dialogue reached a new level beginning in 2014 when former Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung started participating personally in the bi-annual Forums. The prime minister’s participation since then has been very well received by the private sector, as it sent a strong signal of the government’s commitment to a constructive partnership with the business community. Since then, the private sector reports that it fully recognises the VBF as a useful mechanism to interact with the government and suggest reforms that can provide concrete results towards delivering a better business environment.

Source: Vietnam Business Forum (vbf.org.vn) and OECD (2018b).

Aftercare: promoting investment retention and expansions

Beyond a formal public-private dialogue platform, countries are putting in place other measures to consult investors, retain them and encourage their expansion. GAFI is usually recognised by businesses as a trusted government interlocutor, which shows responsiveness and effectiveness when concerns are reported by investors. Proactive aftercare has often been a secondary task of GAFI but recent measures show encouraging signs of systematic post-establishment consultation. For example, GAFI has established a mechanism through the ICSs allowing its staff to follow-up with investors after their establishment. Another way to collect investors’ feedback is through surveys. A first survey of companies established in Egypt was conducted over 2018-19, with the results used for internal discussions and policymaking. A second survey started during the second half of 2019. Surveys are very good tools to identify strengths and weaknesses in the business climate, but it is important that the sample be representative of all companies regardless of their size, nationality or sector of activity. Many IPAs in different regions of the world also conduct surveys of foreign investors (see below). These are often considered as an efficient tool for IPAs to gather a comprehensive and systematic understanding of investors’ concerns and thus to better tailor their recommendations to policymakers accordingly. The authorities could consider using these surveys to prepare synthesis reports that summarise the findings and are made publicly available.

Aftercare activities have a potentially high impact on retaining investors by keeping them satisfied and encouraging them to expand their activities or reinvest in new ones. It is often also less costly from an IPA perspective than other functions. Aftercare can encourage new investors through word of mouth endorsements by satisfied investors already on the ground. Most well-developed IPAs devote a substantial amount of time to working with their existing company portfolio to try to identify potentially new business opportunities for them to consider.

In this light, targeted aftercare activities by GAFI – but also by the SCEZ in the case of investments in the Suez Canal economic zone – should focus on those investors that have the greatest propensity to expand their activities and on those with the highest developmental impact, not only in terms of job creation but also linkages with the local economy (see below the role of aftercare on promoting business linkages). As a matter of consistency and to develop sector-specific knowledge, GAFI should focus its proactive aftercare activities on companies that operate in the same industries and sectors as those chosen for investment attraction and generation.

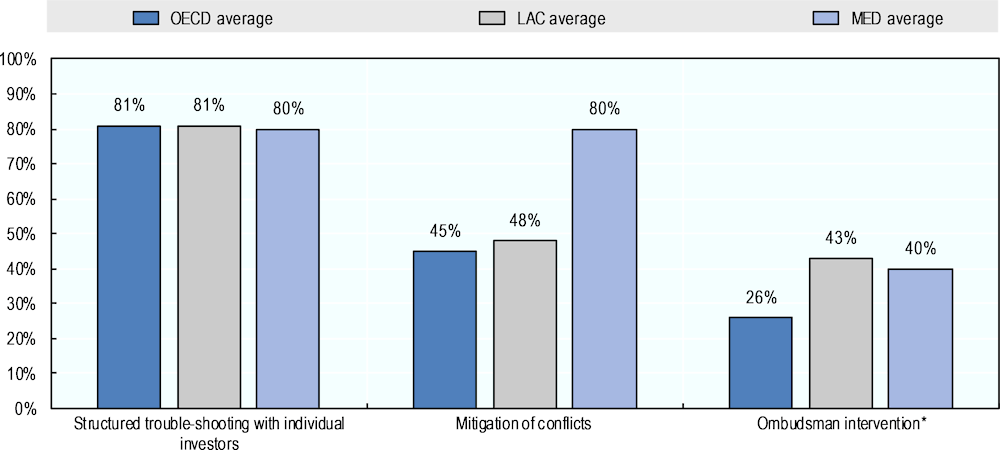

Through aftercare, IPAs can also play an important role in preventing potential disputes involving investors, notably through structured trouble-shooting with individual investors, mitigation of conflicts and ombudsman intervention. Structured trouble-shooting with individual investors is the most frequently available service in all three regions covered by the survey of IPAs, with at least 80% of IPAs in OECD, MED and LAC countries providing this service (Figure 4.6).

Figure 4.6. IPAs’ aftercare services related to dispute prevention in selected regions

Note: (*) Activities marked with an asterisk are not conducted by GAFI, while the others are.

Source: Author based on OECD (2018a), OECD (2019) and Volpe Martincus and Sztajerowska (2019).

Conversely, ombudsman interventions are the least frequently available activity of the three across IPAs and is not performed by GAFI either. An investment ombudsman can provide a useful avenue for preventing potential disputes. Korea was a forerunner in setting up a foreign investment ombudsman in its IPA in 1999. Its role is to solve complaints reported by foreign investors both by sending relevant experts to business sites and by taking pre-emptive measures to prevent future grievances by encouraging systemic improvements and legal amendments (see below the role of policy advocacy). Drawing on the Korean model, several countries have successfully integrated an investment ombudsman in their IPA, including Brazil, the Czech Republic and Turkey.

GAFI is not the only actor involved in aftercare in Egypt. For example, the Administrative Control Authority (ACA), an independent body under the responsibility of the President, is in charge of fighting corruption within government and monitoring the efficiency of the state. It has a specific investment support centre, established in 2015, to help create a sound investment climate in Egypt. The centre functions as a grievance mechanism where individual companies can file a complaint when they face specific problems. ACA reported receiving 280 complaints the first year, 161 the following year and 39 the one after. ACA has sometimes helped solve investors’ complaints by addressing recommendations to line ministries, including sometimes involving the amendment of laws or regulations. ACA has offices in GAFI and in the three main industrial zones.

Through their aftercare activities, GAFI, SCEZ and ACA may also consider working with existing investors to promote responsible business conduct and encourage them to more systematically comply with laws, such as those on the respect for human rights, environmental protection, labour relations and financial accountability, as well as to embrace responsible and sustainable practices in their business operations (see Chapter 7 on Promoting and Enabling Responsible Business Conduct).

Aftercare as a channel for business linkage promotion

MNEs do not necessarily engage in linkages with domestic suppliers automatically – even when local firms are competitive enough and technology-ready. Many MNEs are bound by international contracting arrangements that tie them to international suppliers, offsetting the effectiveness of public policies to promote linkages. In some other cases, MNEs rely on their usual overseas business partners for convenience or because of lack of information, and do not make the effort to look for local firms that can act as suppliers. In this case, the government can bridge information gaps with targeted measures to facilitate exchange of information. By interacting with MNEs on a daily basis, IPAs are often well placed to do so, especially through their aftercare activities.

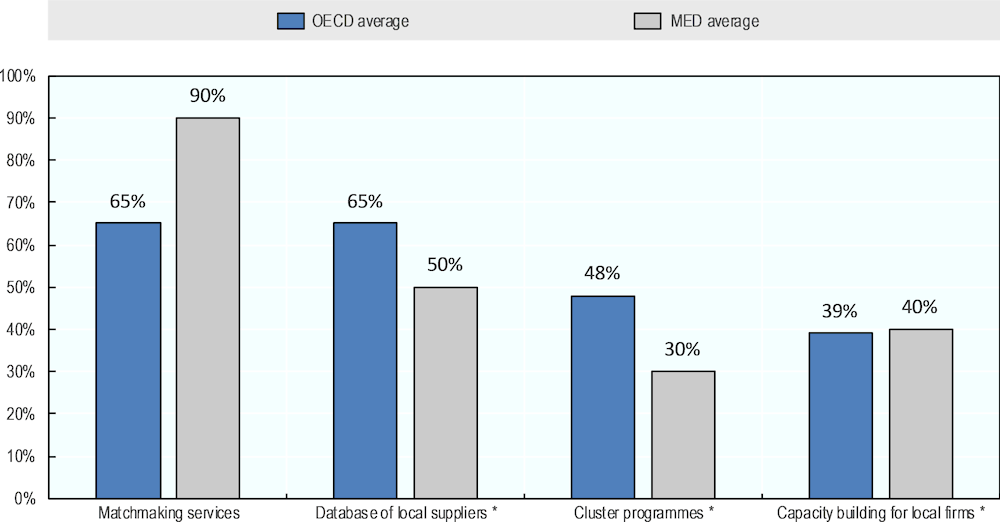

As such, many IPAs around the world, including GAFI, are involved in linkages programmes, most often through matchmaking services between foreign and domestic firms (Figure 4.7). GAFI, like many other IPAs, could also consider compiling a database of domestic firms and make it available to MNEs that are looking for suppliers in Egypt. This would help MNEs by reducing their transaction costs while providing opportunities for local businesses. These databases are often industry-specific and sometimes focus on priority sectors for FDI attraction. Some IPAs, often those that also integrate the mandate to promote domestic investment, have more sophisticated business support programmes (e.g. cluster programmes and capacity building) that can help domestic firms become suppliers of foreign affiliates.

Evidence shows also that long-lasting foreign investors, by knowing the local context better, are more inclined to use domestic suppliers instead of sourcing internationally (Farole and Winkler, 2014). Aftercare can thus support the double purpose of better anchoring foreign investors in the local economy and enhancing their positive spill-overs.

Figure 4.7. IPA linkage and business support programmes in OECD and MED regions

Note: (*) Activities marked with an asterisk are not conducted by GAFI.

Source: Author based on OECD (2018a) and OECD (2019).

Policy advocacy: responding to investors’ needs by influencing policymaking

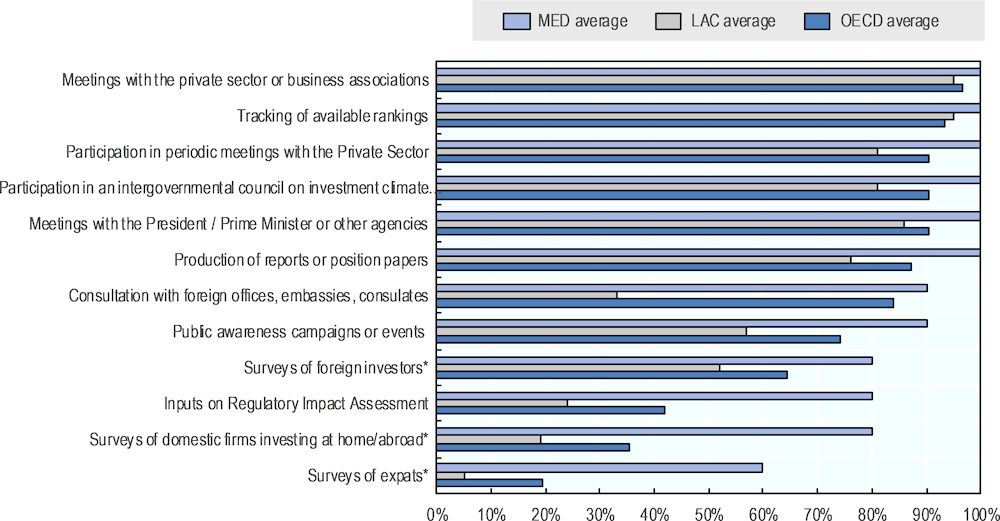

Identifying recurrent problems faced by investors through public-private dialogue and aftercare also effectively contributes to the IPA’s policy advocacy role. As a policymaking and regulatory department – previously under the responsibility of the MIIC – GAFI is naturally involved in policy advocacy. It is contributing to the national investment policy agenda and is thus directly influencing changes in regulations, laws, government policies and their administration. The majority of IPAs in the world are involved in policy advocacy, especially through activities that involve meetings with the private sector and with government officials as well as by tracking international rankings and preparing recommendations for policymakers (Figure 8).

A more autonomous IPA is often better placed to find a balanced approach between the government’s public policy objectives and the private sector’s corporate interests. The question is to what extent it uses the private sector’s feedback to feed into its policymaking and advocacy function. It often depends on the efficiency of public-private dialogue and on the quality of aftercare measures, as described above.

Figure 4.8. Frequency of IPA policy advocacy activities in selected regions

Note: (*) Activities marked with an asterisk are not conducted by GAFI, while all the others are.

Source: Author based on OECD (2018a), OECD (2019) and Volpe Martincus and Sztajerowska (2019).

References

Farole, T. and D. Winkler (2014), Making Foreign Direct Investment Work for Sub-Saharan Africa: Local Spillovers and Competitiveness in Global Value Chains, World Bank, Washington.

IDA Ireland (2014), Winning: Foreign Direct Investment 2015-2019, Dublin.

MIIC (2018a), Investing in Development for the SDGs, Cairo.

MIIC (2018b), Annual Report 2017: Investing in Development, Cairo.

Novik A. and A. de Crombrugghe (2018), Towards an International Framework for Investment Facilitation, OECD Investment Insights, April 2018, https://www.oecd.org/investment/ Towards-an-international-framework-for-investment-facilitation.pdf.

OECD (2019), Mapping of Investment Promotion Agencies in Mediterranean countries, https://www.oecd.org/investment/Mapping-of-Investment-Promotion-Agencies-MED.pdf

OECD (2018a), Mapping of Investment Promotion Agencies in OECD countries, http://www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/mapping-of-investment-promotion-agencies-in-OECD-countries.pdf

OECD (2018b), OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Viet Nam 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264282957-en.

OECD (2015), Policy Framework for Investment, 2015 Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264208667-en

OECD (2011), Attractiveness for Innovation: Location Factors for International Investment, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264104815-en

Volpe Martincus, C. and Sztajerowska, M. (2019), How to Resolve the Investment Promotion Puzzle – A Mapping of Investment Promotion Agencies in Latin America and the Caribbean and OECD Countries, IDB, Washington DC.

World Bank (2011), Investment Regulation and Promotion: Can They Coexist in One Body?, Washington.

Annex 4.A. Options to consider when designing or revising Egypt’s national investment strategy

An investment strategy, whatever form it takes, consists of a document prepared by the government and highlighting its main orientations in terms of how to use investment to foster economic growth and sustainable development. Preparing a national investment strategy is commonly an inclusive, multi-ministerial process, as the multiple policy objectives pursued by governments all call for a whole-of-government perspective so as to increase policy coherence.

Some strategies are high-level documents with broad orientations and showcasing the country’s political will to increase investment, while others are much more detailed and ambitious government action plans setting concrete targets and indicators. Some strategies focus exclusively on FDI while others address foreign and domestic investment equally. Most strategies also address private investment while some include elements on public investment. Some countries also choose not to prepare an overarching investment strategy, but focus instead on sectoral strategies or on investment promotion strategies.

Different types of strategies can be considered by Egypt, depending on the government’s objectives, on the target audience and timeframe, and on whether the document includes how the strategy will be implemented. Three main types of national strategies have been used by other countries to guide their governments in promoting investment in a structured, methodical and well-planned manner (Table 4.A.1). They could all three apply in the case of Egypt and guide its investment strategy making. These three options are:

1. A national policy statement on investment, which presents and describes the investment landscape and the government’s strategic orientations, including its overarching economic goals, regulatory framework for investment, priority sectors and the country’s key local value propositions.

2. An investment promotion strategy that defines the government’s main objectives, tools and performance indicators to attract inward foreign investment. It defines priority sectors and markets for FDI attraction and describes the role and responsibilities of local institutions to support these objectives/targets.

3. A comprehensive investment strategy that outlines the government’s main objectives and orientations to foster investment and what needs to be done to achieve these goals. It focuses on priority investment policies, measures and reforms as well as on the planned institutional and administrative improvements.

Annex Table 4.A.1. Typology of investment strategies

|

Strategy |

Type of document |

Objectives |

Recipients |

Specific features |

Common features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NATIONAL POLICY STATEMENT ON INVESTMENT |

Political and succinct, promotional statement |

Presenting the government’s strategic vision on the role and impact of investment in the economy Demonstrating the government’s commitment to foster and attract investment Showcasing investment policy objectives: past, current and future reforms |

International community, economic partners International investors National institutions, citizens, businesses and civil society |

Presenting the government’s economic vision and broader investment objectives Presenting recent achievements and showcasing upcoming ones Presenting the investment regulatory framework and responsible institutions; Presenting investment promotion and facilitation objectives and services |

Presenting national development objectives Presenting main economic sectors Presenting key FDI trends Presenting investment policy principles and values Presenting investment policy and promotion objectives Presenting measures to achieve objectives Presenting the country’s local value propositions Presenting the target sectors, markets and related activities Presenting performance in international rankings Introducing with a foreword by a senior official (e.g. Minister) |

|

INVESTMENT PROMOTION STRATEGY |

Technical and operational action plan |

Defining the IPA’s the territorial marketing strategy, including: targets, tools, timeframes and performance indicators to attract inward investment Defining the role of the IPA and other institutions involved in FDI promotion |

Investment promotion practitioners (IPA’s staff) Policymakers (competent ministries) Other implementing agencies |

Identifying targets for FDI attraction (sectors, markets, etc.) Defining marketing and targeting tools Defining measures to simplify investors’ establishment and expansion Establishing timeframes for activities Establishing monitoring mechanisms and performance indicators |

|

|

COMPREHENSIVE NATIONAL INVESTMENT STRATEGY |

Technical, comprehensive and descriptive roadmap |

Defining the government’s vision to foster investment in the country and translating it into an action plan Defining how investment can support economic growth and sustainable development Defining what should be the related reforms and concrete measures Defining the role of national investment-related institutions |

Policymakers (competent ministries) IPA and other implementing agencies |

Defining the country’s objectives and orientations on investment Defining measures to ease the entry, establishment and operation of investors Presenting a detailed action plan, including on investment policy reforms Assigning implementation responsibilities Establishing timeframes for activities Establishing monitoring mechanisms and performance indicators |