Between 2011-16, the four counties of Småland-Blekinge (Blekinge, Jönköping, Kalmar and Kronoberg) experienced an unprecedented population increase, recording among the highest net migration rates per capita in Sweden. This chapter examines the processes of recent migrant settlement and integration in Småland-Blekinge, and offers a number of recommendations on how they could be strengthened. The chapter briefly outlines trends in migration in the four counties of Småland-Blekinge and explores a territorial approach to migrant integration around four key themes: i) multi-level governance; ii) community integration policies; iii) capacity for policy formulation and implementation; and, finally, iv) sectoral policies, with a focus on labour market integration.

OECD Territorial Reviews: Småland-Blekinge 2019

Chapter 3. Special focus on migrant integration

Abstract

Introduction

As noted in Chapter 1, between 2011-16, the four counties of Småland‑Blekinge (Blekinge, Jönköping, Kalmar and Kronoberg) experienced an unprecedented population increase (4.3%) which was fuelled by a rise in migration, mostly from asylum seekers and refugees. The four counties recorded among the highest net migration rates per capita in Sweden during this time.1 As counties experiencing labour market shortages in some occupations, migrants have the potential to make an important contribution to employment and, with a younger age profile than the native population, they help to balance the counties’ demographic structure which is ageing. Yet, the participation of migrants in the labour market is low and thus represents a challenge for the region. The employment rate of those who are foreign-born is 65.5% versus 80.5% for those born in Sweden for those aged 15-74; meanwhile, the unemployment rate is 15.8% for foreign-born versus 4.8% for those born in Sweden (Statistics Sweden, 2016[1]). Those who arrive do not always have the language skills, education or training required for them to successfully integrate. The pace at which newcomers have arrived in Småland‑Blekinge has challenged the counties to provide suitable housing and to reorient services and develop new ones to meet the needs of this group of diverse individuals. There successful integration and retention in the region will be critical for its future development.

This chapter examines the processes of recent migrant settlement and integration in Småland‑Blekinge and offers a number of recommendations. Inclusion and equal access to opportunities is a major aim of the migrant integration in Sweden and achieving these goals requires that different levels of government work together – local, regional and national. This chapter draws on a range of data sources including: a questionnaire that was distributed to the counties in order to gather information on migration trends and policies; interviews with key stakeholders on migration in all four countries; statistical analysis (data from Migration Agency and Statistics Sweden) and; a literature review. This chapter is framed within a territorial approach to migrant integration and draws on the OECD’s recently developed Checklist for Public Action for Migrant Integration at the Local Level developed in the forthcoming report A Territorial Approach to Migrant Integration: The Role of Local Authorities (OECD, 2018[2]). A territorial approach to migrant integration emphasises that the cities and communities where migrants arrive have different characteristics that influence their capacity to welcome new groups. Conversely, newcomers are more or less concentrated in different places and they cluster according to different factors (i.e. presence of communities from the same country of origin, motivations for moving, job and education opportunities, etc.). Consequently, the ways that local authorities and their partners at different levels of government – state or non-state actors – address migrant integration challenges has an impact on their outcomes. The characteristics of the place, of the host community and of those arriving and how local authorities and other stakeholders can ensure the sustainable integration of migrants determines outcomes – both now and in the longer term.

This chapter explores these dynamics in two parts. First, it briefly outlines trends in migration in the four counties of Småland‑Blekinge. Following this, four themes linked to a territorial approach to migrant integration are discussed: i) multi-level governance; ii) community integration policies; iii) capacity for policy formulation and implementation; and, finally, iv) sectoral policies, with a focus on labour market integration.

Migration trends

While a large share of migrants to Sweden in the early 1980s were Nordic work migrants, those arriving since then are increasingly doing so for humanitarian reasons or for the purposes of family reunification (see Box 3.1 on terminology). The profile of migrants has thus changed, and rates of migration have grown sharply in intervening decades. The share of foreign-born in Sweden has more than doubled since 1980 – increasing from 7.5% in 1980 to 16% in 2015 (OECD, 2017[3]). Estimates suggest that about half of the current foreign-born population originally came to Sweden as refugees or as family members of refugees (OECD, 2017[3]). This changing profile of migrants in terms of language, education and skills training has required new services and models of integration in order to help newcomers find jobs and become autonomous. Service providers have been challenged to quickly build capacity and to adapt strategies and policies to the needs of a growing public that changed its characteristics over the years.

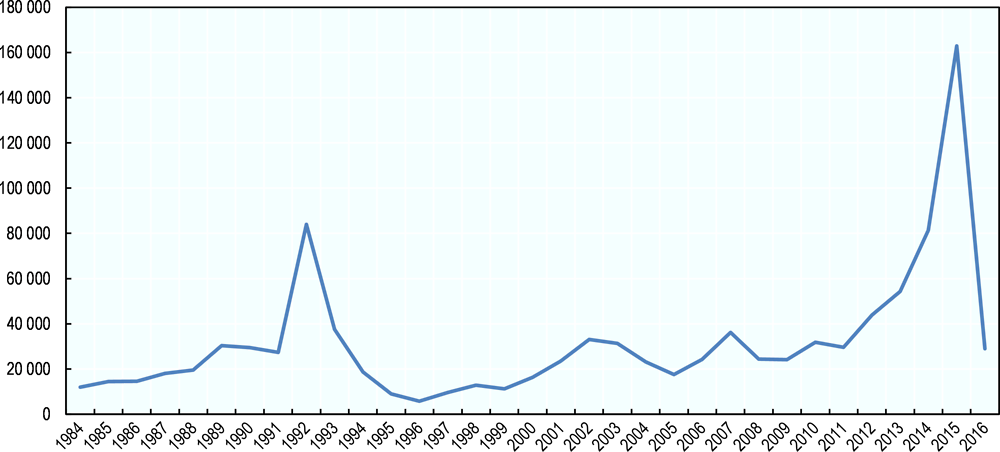

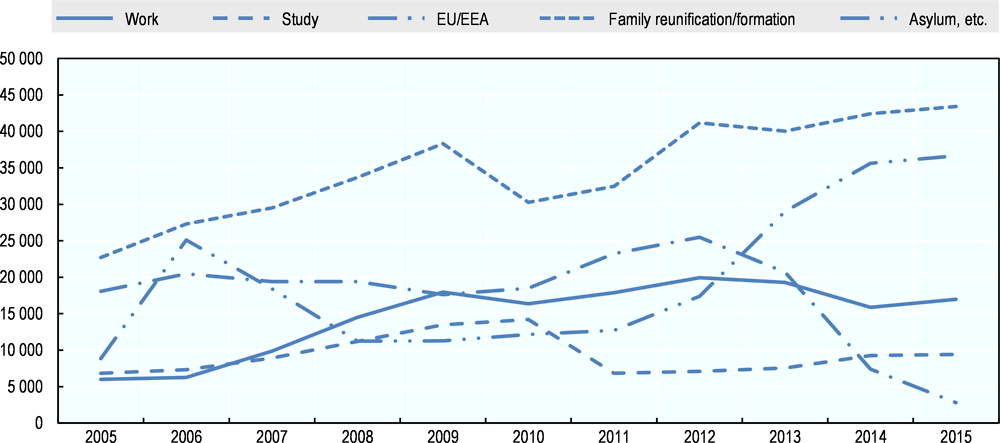

The most recent wave of asylum seekers is larger than in past decades and between 2012‑16, the top three countries of origin were Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria (OECD, 2017[4]).2 In 2015, the number of asylum seekers to Sweden reached an all-time high, at 162 877 (Figure 3.1). This was the highest per capita inflow of asylum seekers ever to be registered in an OECD country. In 2015, the most common reason for migration or asylum based on first permits was for the purposes of family reunification or formation followed by asylum (Figure 1.32). This inflow has since fallen to 28 939 in 2016 as a result of external factors as well as a tightening of immigration policy. In 2016, Sweden adopted a temporary act restricting the possibility of being granted a residence permit and the right to family reunification, with the immediate effect of reducing asylum-related immigration. Similar reforms were adopted in other OECD countries.3

Figure 3.1. Asylum seekers to Sweden, 1984-2016

Source: Migrationsverket (2018[5]), Översikter och Statistik från Tidigare år [Statistical Review and Archives], https://www.migrationsverket.se/Om-Migrationsverket/Statistik/Oversikter-och-statistik-fran-tidigare-ar.html (accessed on 31 January 2018).

Figure 3.2. Migration and asylum, first permits, 2005-15

Source: Swedish Migration Agency (2018[6]), Overview and Time Series, https://www.migrationsverket.se/English/About-the-Migration-Agency/Facts-and-statistics-/Statistics/Overview-and-time-series.html (accessed on 31 January 2018).

Box 3.1. A note on terminology

The general term “migrant” describes people that move to another country with the intention of staying for a significant period of time. While asylum seekers and refugees are often counted as a subset of migrants and included in official estimates of migrant stocks and flows, the UN’s definition of “migrant” does not include refugees, displaced, or others forced or compelled to leave their homes; it is reserved for those who are free to migrate. It can, for example, include EU citizens who are moving to work, study or live in Sweden or those who are moving to Sweden for purposes of family reunification (joining a family member who is a Swedish citizen or who has a permanent residence permit).

In Sweden, the term “newly arrived” (“nyanländ” in Swedish) has come to serve as a common term for all migrants who have arrived in the last few years whether they flee war, natural disasters or extreme poverty or whether they have refugee status or not. Individuals are termed “newly arrived” in Swedish society when they have been legally accepted and settled (prior to this they would be referred to as having the status of asylum seekers). An individual can, therefore, have been an asylum seeker for a period of time before a decision is made. He/she then becomes newly arrived. It can take some time to receive a residence permit and settle in – e.g. finding employment and housing. This process of becoming established can take considerable time, up to several years.

Those who have submitted a claim for international protection but are awaiting the final decision are referred to as “asylum seekers”. There are generally two reasons for granting asylum seekers residence permits in Sweden:

1. An individual qualifies for refugee status. In accordance with the UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, Swedish legislation and EU regulations, a person is considered a refugee when they have well-founded reasons to fear persecution due to race, nationality, religious or political beliefs, gender, sexual orientation, or affiliation to a particular social group. A person who is assessed as a refugee will be granted a refugee status declaration (an internationally recognised status) and will normally be given a residence permit for three years in Sweden. Refugees claiming asylum who are under 18 years old and come to Sweden without any parents or relatives are termed “unaccompanied children” (ensamkommande). They are received under a detailed policy and require protection due to their underage status.

2. A person is deemed in need of subsidiary protection. A person deemed in need of subsidiary protection is one who: is at risk of being sentenced to death; is at risk of being subjected to corporal punishment, torture or other inhumane or degrading treatment or punishment; or as a civilian, is at serious risk of injury due to armed conflict. Subsidiary protection status is founded on EU regulations and individuals are generally granted a residence permit for 13 months in Sweden

There are some extraordinary circumstances whereby asylum seekers may be granted a residence permit even if they do not need protection from persecution (e.g. serious health issues). Those who are denied protection status and decide not to appeal the decision or do not apply for another form of legal permission to stay become “undocumented migrants”.

Among the four counties in Småland‑Blekinge, Kalmar had the largest share of asylum seekers in 2016 while Jönköping had the largest number of unaccompanied minors (Table 3.1). Of all those registered with the Migration Agency in 2016, almost 15% were unaccompanied children requiring special protection and support.

Table 3.1. Persons in the Migration Agency’s reception system, by county, 2016

|

|

Residential residents |

Own housing |

Other accommodation |

Total |

Of which, unaccompanied children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Blekinge |

2 032 |

385 |

450 |

2 867 |

416 |

|

Jönköping |

2 921 |

979 |

959 |

4 859 |

939 |

|

Kalmar |

4 942 |

771 |

714 |

6 427 |

710 |

|

Kronoberg |

2 317 |

759 |

554 |

3 630 |

550 |

|

Total |

12 212 |

2 894 |

2 677 |

17 783 |

2 615 |

Note: Residential residents (ABO) are persons living in accommodation offered by the Migration Agency (Migrationsverket), usually an apartment in a rented house. Own housing (EBO) refers to accommodation where the person arranges their own housing. The category “other accommodation” consists mainly of single-parent children in municipal housing/family homes/pre-arranged children (children living with, for example, relative).

Source: Migrationsverket (2018[5]), Översikter och Statistik från Tidigare år [Statistical Review and Archives], https://www.migrationsverket.se/Om-Migrationsverket/Statistik/Oversikter-och-statistik-fran-tidigare-ar.html (accessed on 31 January 2018).

Migration as an opportunity to rebalance demography in the region

Migration has the potential to help the regions in Småland‑Blekinge have a more balanced demographic profile. For example, in Blekinge County, where the refugee reception per capita has been among the largest in the country, the number of individuals of working age has been bolstered through migration. In many of the county’s municipalities, immigration has helped prevent population decline while increasing the working‑age population. While Blekinge County has shown a positive population trend over the last 4 years, at the same time, the trend of population ageing continues and those aged 65 and older constitute 23% of the population (2016). The elderly dependency ratio (aged 65 and older) remains high at 84% in 2016 (10% higher than in 2000).

The participation of migrants in the labour market is lower than native-born but there are encouraging results for newcomers after the introduction programme

Population growth is hence of great importance to Småland‑Blekinge in several ways, not least for the region’s future supply of skills. As such, employment is a core aspect of the integration process. It is not only vital for economic integration but also has implications for broader social integration, such as finding adequate housing, learning the host-country language and interacting with the native-born population. Over the last decade and a half, progress has been made in terms of the employment rate of the foreign-born versus native-born population; however, at the same time, the unemployment rates of foreign-born persons has increased and there remains a large discrepancy in overall labour market outcomes between the foreign-born and native-born population (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2. Labour market outcomes, Sweden, 2000 and 2016

|

2000 |

2016 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Foreign-born |

Native-born |

Foreign-born |

Native-born |

||

|

Employment rate (%) |

Men |

51.6 |

75.8 |

68.7 |

79.8 |

|

Women |

48 |

73.2 |

61.3 |

78.8 |

|

|

Total (men and women) |

49.8 |

74.6 |

64.9 |

79.3 |

|

|

Unemployment rate (%) |

Men |

13.5 |

5.1 |

16.6 |

5.3 |

|

Women |

11.2 |

4.3 |

15.1 |

4.5 |

|

|

Total (men and women) |

12.4 |

4.7 |

15.9 |

4.9 |

|

Source: OECD (2017[8]), International Migration Database, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00342-en.

Sweden’s Employment Service (Arbetsförmedlingen) reports recent progress in the share of newly arrived immigrants in each county who, 90 days after leaving the agency’s introduction/establishment programme, are either working or in some form of education or training. Between March 2016 and February 2017, Blekinge had shown the highest rate of employment, education or training 90 days post establishment programme among all Swedish counties at 44% (both men and women).4 In Kalmar, this figure stood at 35%; in Jönköping, 34% and in Kronoberg, 26%.5 In all counties, the rate of female employment or educational attachment post-establishment programme is lower, but Blekinge is also notable for having the smallest gender gap in this indicator.

While the region of Småland‑Blekinge is experiencing labour market demand in some occupations which migrants can help to fill, there is often a skills mismatch between newcomers and the types of jobs available in the region. The two trends of high humanitarian and family reunion migration, and declining school results increase the supply of low-skilled and low-qualified labour, while demand is tilted towards high skills and qualifications un Sweden (OECD, 2017[3]). Low-skilled jobs account for only about 5% of total employment in Sweden (OECD, 2017[9]).6 Even in industries where low‑skilled jobs may exist, there may be a skills mismatch. For example, in Småland-Blekinge, it has been reported that there are unfilled jobs in the forestry and dairy industries but that many migrants do not have the skills or background to work in these areas, having largely migrated from cities. Large technology industries also experience recruiting challenges in Blekinge County.

A territorial approach to migrant integration

Migrant reception and integration: Multi-level governance dynamics

Sweden has long been at the forefront of migrant integration policies and the country receives a high ranking from the Multidimensional Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX).7 It was one of the first countries to recognise the importance of such policies and it has provided state-funded language courses to migrants since the 1960s. Migrant integration policies were solidified in law in 1996 through “the recognition of equal rights, obligations and opportunities for all, regardless of ethnic or cultural background” (Wiesbrock, 2011[10]).8 The process of migrant settlement and integration involves a wide array of institutions – from national, county and local governments to private and not-for-profit organisations and civic groups. The effective co‑ordination of these actors thus represents an important multi-level governance challenge – one that extends across several policy areas, including health, skills, education, housing and transportation.

Enhance the effectiveness of migrant settlement and integration policy through improved vertical co-ordination and implementation at the relevant scale

The large numbers of arrivals in recent years have put a lot of stress on Sweden’s migrant reception and integration systems at all levels of government. In the regions, frontline organisations (e.g. non-governmental organisations (NGOs), state agencies, municipalities that directly deliver services) had to quickly build capacity and increase staffing and a number of co‑ordination challenges arose. Given this, in the past year, there have been efforts to take stock and improve the process in order to make the system more efficient work better vertically and horizontally across levels of government in order to better meet the often-complex needs of newcomers in a timely manner.

At the national level, the Ministry of Justice is responsible for migration policies; the Swedish Migration Agency and the Swedish Police Authority both report to the Ministry of Justice on these matters. The Swedish Migration Agency is a key institution and is responsible for residence permits, work permits, visas, the reception of asylum seekers, voluntary return, acquisition of citizenship and repatriation (Migrationsverket, 2016[11]). The Swedish Migration Board is the first state authority in which a refugee comes into contact and there is a certain process that every single asylum seeker has to go through. The agency has the main responsibility for the reception of asylum seekers, from the date on which an application for asylum has been submitted until the person has been received by a municipality after being granted a residence permit or has left the country (in the case of a rejected application). The Migration Agency should “motivate” persons to return to their home countries if their application for asylum is declined. However, they are not responsible for the repatriation, the police are. Meanwhile, integration policies are largely the responsibility of the Ministry of Employment. Once an individual has been granted a residence permit, the National Employment Service (Arbetsförmedlingen) offers support for those who seek employment or require training. Its operational activities are divided into three regions across Sweden (northern, middle and southern regions). There are currently 280 employment offices across the country which provide an important source of knowledge on the local labour market and training issues, and as part of the national agency, can help to synthesise and inform the national government about how policies are working on the ground.

The role of county administrative boards in migrant reception and integration policies has recently changed in an effort to improve vertical co‑ordination. County administrative boards are representatives of the state in the counties and serve as a link between the population, the municipalities, governmental authorities and the Swedish Parliament. Following from the spring amending the budget for 2016, from 2017, county administrative boards will be tasked with co‑ordinating and organising early measures for asylum seekers and others. In light of this, the Swedish Migration Agency will no longer be responsible for organised activities for asylum seekers that aim to strengthen their knowledge of the Swedish language and other measures to promote integration. By shifting the responsibilities to the county administrative boards, the government hopes that multi-level governance co‑ordination will be improved (something that is part of the County Administrative Board’s (CAB) existing structures) and that asylum seekers and others will have better access to regional and locally adapted early measures.

At the regional level, county councils primarily have responsibility for healthcare and transportation, and municipalities are responsible for various aspects of migrant integration, notably language training, adult education, social assistance and compulsory school (K-12 education) and the reception of unaccompanied minors. The approach to and quality of these municipal services can vary considerably across the country (OECD, 2016[12]). Interviewees in Småland‑Blekinge have noted that much is being done but not enough is co‑ordinated between all of the organisations and agencies working on these issues. The Labour Agency and the County Administrative Board is co‑ordinating to some extent, as is Region Blekinge; meanwhile, municipalities and other organisations that provide services to migrants tend to work in an operative manner.

Like many OECD countries, Sweden experienced a decentralisation of migrant integration policies in the 1980s, but there has since been a recentralisation of some elements due in part to concerns that labour market integration programmes were not strong enough or consistently addressed across municipalities (see Box 3.2 for elaboration). Interviewees in Småland‑Blekinge have noted the drive towards centralisation on the national level and have expressed that they feel there needs to be more autonomy at the regional and local levels, backed by financial resources which are invested based on local needs. While the national administrations and agencies as well municipalities (also county councils) responsible for various aspects of migration and integration have received additional resources, there are limited resources to connect these bodies with the organisations responsible for regional growth/development. Stronger connections between the two would strengthen migrant labour market integration and economic development.

Box 3.2. From localisation to centralisation: Newcomer integration policies in Sweden

In the mid-1980s – alongside a shift in multiculturalism policy – responsibility for migrant integration was transferred from state ministries in Sweden to the Employment Services and municipalities. This decentralisation accompanied a change in the profile of many newcomers from labour migrants to those arriving on humanitarian and protection grounds. The rationale for this localisation of integration policies was so that municipalities could design programmes that were suited to local conditions and needs with municipalities offering state-funded language and labour market training and civic orientation to newcomers. These services tended to focus on social care over labour market integration and as such, state policy was shifted to encourage a stronger emphasis on the former starting in 1991.

At this time, a new refugee reimbursement policy was established whereby municipalities were compensated on a per person basis for two years as opposed to reimbursement for the costs associated with social assistance. This reorientation thus created an incentive to help newcomers be self-sufficient as quickly as possible. Accompanying this change, a new state agency – the Swedish Integration Board – was established in order to help municipalities successfully implement integration strategies, learn from best practices, and co‑ordinate between the national, regional and local levels. This approach produced successful regional and local agreements but concerns at the national level over differing local capacities and standards for integration remained. The Swedish Integration Board was subsequently dissolved in 2007.

In 2010, the state took over responsibility for Introduction Programmes from municipalities (Etableringsuppdraget). Furthermore, the Employment Services were given overall responsibility for labour market integration and an individual state allowance was adopted. Emilsson (2015[13]) describes these changes as increasing state involvement in three ways: i) the responsibility and administration for the introduction programmes moved from the municipalities to the state; ii) state funding for integration programmes increased; and iii) the content of the programme became regulated by law. Other state centralisation efforts affecting the local level include a new law that forces municipalities to accept the settlement of unaccompanied minors, increases rights for undocumented migrants and provides state funding for local anti-discrimination measures.

Source: Emilsson, H. (2015[13]), “A national turn of local integration policy: Multi-level governance dynamics in Denmark and Sweden”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40878-015-0008-5.

The recent wave of migrants to Sweden has raised numerous multi-level governance challenges – many of which are profiled further in this chapter. For example, the waiting period to have asylum cases heard and to receive a residency permit has impacted the sequence and timing of when individuals can access services related to integration which are delivered at the local level. Further, there have been numerous challenges related to housing wherein individuals have sought out their own housing in order to gain access to some services; but which has in some instances led to overcrowding and substandard housing conditions. These issues have been identified early on and the different levels of government and social actors are working on joint solutions. There has also been some reallocation of responsibilities among service organisations in order to address these issues. For a thorough description of the division of competencies related to migrant integration across the level of governments in Sweden please see “Integration of Migrants in Cities: A Case Study on the City of Gothenburg” (Piccinni and Lindlom, forthcoming[14]). The following section profiles existing initiatives where progress is being made and additional mechanisms that can be used to improve multi-level governance in Småland‑Blekinge.

Efforts to conduct institutional mapping are underway. Identifying the type of relations across levels (co-operation, subordination and representation) helps to clarify roles and responsibilities and establish spaces for co‑ordinated actions. It provides a useful starting point in multi-level dialogue and can be used to identify redundancies, gaps, costs and supports for reception and integration activities. In Småland‑Blekinge, it was noted that there are many different groups at the local level that have some programmes or services to offer to migrants – e.g. associations, community groups and so on. While the main governmental actors know one another and are increasingly working together, this broader community could be better linked up and institutional mapping could help to achieve this. There are some positive actions on this front. CABs have recently been given the assignment to map the civil society’s efforts for asylum seekers. As a new function, CABs should share expertise on best practices on how to develop and share this information in an accessible and easily updated format and use it for policy purposes.

There is increasing use of multi-level and multi-stakeholder dialogues. Multi-level and multi-stakeholder dialogues increase mutual knowledge of integration practices and objectives across levels to improve system design (see Box 3.3 for examples). Already in Småland‑Blekinge, there are successful examples of this approach. For example, Blekinge and Kalmar Counties have regional councils for integration which act as a platform to discuss key issues for those who work closely with newcomers. The council consists of all municipalities, the county council, the region, the employment agency, Migrationsverket and Försäkringskassan and is led by the CAB. This has been a task of the County Administrative Board since 2010 and a regional strategy was adopted in 2013. With the CAB now having responsibility for collaboration at a regional level for activities for asylum seekers (as of January 2017), there is a dialogue with the migration authority to mobilise local actors. The CAB is working to improve its ability to serve asylum seekers and to support integration effort (prior to this, asylum seekers were formally the migration authority’s responsibility). It remains important to note that there are several policy domains where the CAB does not have formal responsibility, such as healthcare, and collaboration with the healthcare sector needs to be improved. This, there is a broader application for the multi-level and multi-stakeholder dialogue approach.

Further efforts are needed to establish inter-municipal partnerships and strengthening urban-rural linkages. Municipalities can, for example, set up joint service provision and financial agreements across neighbour municipalities for migrant integration programmes and services. This strategy is used for example by the Association of the Region of Gothenburg (involving 13 municipalities). Together with four other sub-regional associations and the region, they have set up an organisation called Validation West (Validering Väst) which works with various stakeholders (including the employment agency) in order to help individuals receive documented proof of their skills (e.g. as an electrician or a builder) so that they can work in specific vocations that require a license or formal education. One of their goals for 2017 is to create conditions for newcomers to Sweden to have their practical skills “made visible” and documented (OECD, 2018[2]). Some municipalities across Småland‑Blekinge are adopting a partnership approach, for example, Ronneby Municipality has a Blekinge integration and education centre which operates all societal orientation for immigrants in Blekinge. As another example, in Kronoberg County there is an ongoing project, “Establishment Co‑operation Kronoberg”, that aims to enhance regional and local co‑ordination between state and municipal resources in order to help individuals will succeed with their establishment (Svenska ESF-rådet, 2018[15]). Lessons from how these have been structured and what they have achieved should be more widely shared in order to expand such initiatives and to gauge in which policy areas they most make sense.

Box 3.3. Multi-level and multi-stakeholder dialogue mechanisms – Examples from practice

Multi-level and multi-stakeholder dialogue provides upfront interaction between state and non-state actors who play a significant role in integration issues (i.e. NGOs, the private sector, migrant and refugee organisations, unions, faith-based organisations, etc.). The OECD has identified four models that are commonly used to achieve this:

1. Sharing information: To allow the central and local levels to mutually learn about policy directions and place-based needs. Such exchanges should inform the local and national levels of policymaking.

Austria: The Expert Council for Integration is composed of relevant ministries, all provinces/Länder, and five of the most relevant NGOs. It meets twice a year to share information around the implementation of the national plan for integration.

Germany: The Permanent Conference of Ministers and Senators for the Interior of the federal Länder (IMK) – subnational governments – which takes place twice a year, is an important venue in co-ordinating policymaking between Länder and the federal level.

2. Design and implementation of integration policies: From conception to action for integration policies, these dialogues take the form of peer negotiation in which each party has its share of sovereignty and the result is that a policy is agreed upon at both the local and national level. A multi-level council with programmatic responsibilities for EU and national funding relevant for migration can serve such a purpose; a multi-level working group to define criteria for asylum seekers’ and refugees’ geographical distribution as well.

3. Clarifying roles and responsibilities to implement specific policies contributing to integration objectives. The multi-level task force on youth employment with a focus on migrant youth among other groups is an example of such an approach.

The Netherlands: National-local consultation mechanisms are topic-specific; they involve relevant national ministries, the local level (often through the G4 composed by the city of Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam and Utrecht) and social partners (trade unions and employers associations). For instance, the Ministry of Labour set up a roundtable to fight discrimination in the labour market and a national measure was developed to impose anonymous job applications.

4. Evaluation shared mechanisms: To assess the results of integration policies, including in terms of the respective contribution of levels of government, and possibly use them to revise the next policy cycle.

Germany: The institutionalised dialogue conference of ministers for the integration of the Länder (Integrationsministerministerkonferenz, IntMK) is an interface for the federal level and develops indicators that are compared across Länder.

Source: OECD (2018[2]), A Territorial Approach to Migrant Integration: The Role of Local Authorities, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Seek policy coherence in addressing the multi-dimensional needs of and opportunities for migrants at the local level

Different policy sectors (housing, education, jobs, health, etc.) and related integration-relevant initiatives are often designed in silos. This can lead to a number of negative outcomes, such as loopholes for migrants in their access to services because of administrative delays, or changes in regulatory frameworks that suspend service provision; uncoordinated services that do not connect users’ information and multiply administrative obstacles (OECD, 2018[2]). These gaps often result from difficulties or in mainstreaming an integration approach across policy sectors and/or a lack of information-sharing across public agencies. Policy silos can also occur where the same group is targeted (migrants, newcomers, etc.) resulting in fragmentation of objectives, measures and actors. Local policymakers are often best placed to ensure that local strategies (i.e. economic development, social inclusion, spatial planning, youth employment, elders’ inclusions, cultural activities, etc.) take into account the presence of migrants in their community, not only to ensure equal treatment but also to make sure their contribution to local development is valued.

The overall goal of more coherent local policies is to ensure that integration is facilitated simultaneously through different aspects of migrants’ lives: labour integration, social, language, social assistance etc., driving them to self-reliance and empowering them as active members of their new societies. Some additional strategies that can help Småland-Blekinge to deliver on these objectives are noted below.

Integration service hubs/one-stop shops could help individuals to better navigate the services available to them. Regrouping relevant information in one place renders the integration process more transparent and helps to direct newly-arrived migrants to the services they need. Recent feedback from migrants in Kalmar collected by the employment offices reinforces this point. In service assessments, refugees have indicated that it is very hard for them to know who provides what services. These types of issues are well recognised and, in an effort to better integrate services and information across sectors, Sweden launched the platform “Setel.in”, which brings existing applications and websites relevant to new arrivals together in one place. Another example from Sweden of such services is Integrationscenter Karlskrona and the Facebook-based information-sharing initiative Meeting-place Olofström (Mötesplats Olofström). Similar initiatives have recently been developed in Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom and several other OECD countries (OECD, 2017, p. 78[4]). However, given the recent assessments by refugees of Kalmar County’s employment office, more efforts need to be made on the ground to help individuals navigate the host of services available to them.

Creating municipal or regional departments or co-ordination bodies would help to mainstream integration policy across municipal departments. Such permanent or ad hoc bodies can be used to raise awareness and build capacity in other departments and to develop “migration-sensitive” policies in their respective sectors of competency (OECD, 2018[2]). In the case of county councils, such bodies could have specific tasks, for instance, monitoring the health status of migrants, etc. Such bodies can also take on an operational mandate, by assessing migrant integration policies, programmes and services. For example, in Tampere, Finland, the Head Co-ordinator of Immigrant Affairs is responsible for co‑ordinating services in all the policy sectors of the municipality. At present in Småland‑Blekinge, there is usually one integration co‑ordinator per municipality; however, the person is typically focused on services to refugees as opposed to co‑ordinating broader organisational responses. In Småland‑Blekinge, county administrative boards work with municipalities on the integration process. In interviews it was noted that different authorities have struggled to manage their administrations and that there is variability across municipalities in terms of how well they have been able to manage – a point that has been made in larger studies of the overall Swedish migration system more generally as well (OECD, 2016[12]). The creation of an integration team which could help connect the key departments together with those working in the health system was mentioned as one possible solution to this issue which should be explored.

Consultative mechanisms with migrant communities could be more developed. Some municipalities across the OECD have developed mechanisms to include migrant communities in the formulation, implementation and evaluation of the policies that concern them. For example, in Berlin, Germany, the State Advisory Board on Migration and Integration includes representatives of seven migrant organisations (elected) and makes recommendations and approves the appointment of the Integration Commissioner of the City of Berlin (OECD, 2018[2]). Municipalities in Småland‑Blekinge do not have strong consultative or engagement practise with migrant communities as yet. As communities become more strongly established in the region, this function will continue to grow in importance.

Some municipalities in Småland-Blekinge have adopted local integration strategies – but these need to be better resourced in order to be effective. Integration strategies can serve as political programmes or communication tools, while others may include an action plan and/or define concrete actions, indicators and responsibilities (OECD, 2018[2]). Some municipalities such as Ronneby in Blekinge County have adopted an integration strategy. In order to be operational, such action-oriented strategies require a budget and dedicated personnel. It is important to involve different services (schools, employment agencies, health units, police, etc.) and non-state actors in the formulation of the integration policy, such as migrant associations, civil society organisations and business. If informed by local economic needs and data on the characteristics of migrant population settled in the city or community, such strategies can identify which enabling factors (i.e. education opportunities aligned with the local labour market, etc.) could allow migrants to fully contribute to the drivers of local development. A strategy adopted by some OECD municipalities is to establish thematic strategies rather than integration ones (see Box 3.4 for examples) (OECD, 2018[2]). For counties and municipalities in Småland-Blekinge, this approach might develop priority areas of action.

Service providers would benefit from enhanced capacity to share information among them. In Småland-Blekinge, one of the barriers to improve policy co‑ordination is the confidentiality requirements between the various service providers. At present, there is a siloed system wherein, for example, employment services and municipalities cannot speak to one another about their cases. Consequently, at the operational level, it can take a long time to know how to better co‑ordinate services, which in turn impacts how migrants access health, work or studies. Confidentiality requirements are of course in place for a very good reason in order to protect individuals; but at the same time, better solutions are needed to help individuals navigate the system and to improve how services interact with one another. One option which could help in this regard is to assign a caseworker to an individual who would help them navigate services which are delivered across multiple organisations and facilitate information sharing. One of the projects which have helped to improve the capacity to share information among service providers in Småland-Blekinge is the Meeting Venues Project which began with Vaxjo Municipality participating along with four others in 2015 (Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting, 2018[16]). The project entailed collaboration among a number of public authorities (e.g. the Employment Service, the Insurance Agency, the Migration Board, the Pension Agency, the Tax Agency), in order to simplify and improve the interaction of newcomers’ first contact with public authorities. Through this project, it has been found that a process which usually takes between 3-4 weeks for an individual can be reduced to a few hours in Project Meetings – leading to estimated savings of SEK 27 000 (Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting, 2018[16]). Given the success of this approach, there are efforts to employ this type of partnership in more municipalities in the future.

Box 3.4. Adopting a local integration strategy: Examples from Berlin, Vienna and Gothenburg

Some municipalities in the OECD have adopted local integration strategies in order to address problems that affect migrant and host communities through cross-sectoral measures, for instance: protecting diversity and security; raising awareness about human rights; anti-discrimination; anti-radicalisation; inclusion and emancipation.

Berlin has developed and readjusted its integration concept several times since 2005. In 2010 the most recent Participation and Integration Act was established. It is grounded in law and has to be considered as an obligation to follow in all legislative and administrative actions taken by all of the city departments, agencies and other subordinated bodies across sectors. Its main aim is to ensure that all people, regardless of their origin, have the same access to all services of the city.

The City of Vienna has established its own guidelines for integration and diversity politics. Defining its integration policy as a set of measures that equalise access to services across departments for the whole population. Following this principle, the city’s integration department (MA17) conducts reports that measure the integration of its migrant population in comparison to its native-born population. Further, the city evaluates its own institutional departments and services regarding diversity management. Part of this evaluation is measurements against benchmarks for the inclusion of diversity into the department’s own strategy and field of action.

Gothenburg: An example of programming across public sectors at the municipal level is the programme called ‘‘Safe in Gothenburg’’. Launched in 2016, it aims to combat crime and increase citizens’ trust in particular neighbours facing segregation challenges. The municipality and the local police co-ordinate efforts regarding security issues and violence prevention. The programme follows a community-based approach: it builds first on inquiries from inhabitants and, second, on inputs from the police such as indicators on high crime rates in certain areas, as well as third, on inputs from social services of the municipality, like low educational attainment or unemployment rates in different neighbourhoods. Based on a collection of such information, common problems were predefined and addressed in a joint action plan. What does it take to implement such a project? Facilitation with different groups at the community level, human resources dedicated to the project (municipal personnel, social workers and police officers) and specific funding to implement the measures identified.

Source: OECD (2018[2]), A Territorial Approach to Migrant Integration: The Role of Local Authorities, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Ensure access to and the effective use of financial resources that are adapted to local responsibilities for migrant integration

The large numbers of newcomers to Småland-Blekinge in the past few years has imposed financial costs for the counties and municipalities related to the delivery of integration programmes and services. In recognition of these types of challenges, Sweden has bolstered its funding to address the refugee situation, spending close to 1% of its GDP in 2016 (OECD, 2017, p. 86[4]). This includes SEK 534 million (EUR 57.8 million) for integration measures, such as new language initiatives and reforms of the “Swedish for Immigrants” scheme, skills assessments and validation for asylum seekers. Moreover, the compensation paid to municipalities per new arrival has been raised, with an estimated additional budget cost of SEK 1.1 billion in 2016 (EUR 119 million) and SEK 2.6 billion in 2017 (EUR 272 million) (OECD, 2017, p. 86[4]).

Sweden’s 2016 national budget announced a number of funding priories to support migrant reception and integration efforts including: increased access to mental healthcare for traumatised asylum seekers; more funding for early skills assessment for asylum seekers (for the Swedish Public Employment Service); increased funds for refugee guides to carry out early measures for asylum seekers; special measures in liberal adult education for folk schools; increased funds for county administrative boards’ work on the reception of unaccompanied minors and newly arrived immigrants; and increased funds for compensation to municipalities for special costs for the reception of newly arrived immigrants.9 Further, Sweden’s Spring Fiscal Policy Bill (2017) shifted some funding allocations to a reallocation of responsibilities. Funding will be shifted from the Swedish Migration Agency to county administrative boards to fund their expanding role. In the past year, funds to the Swedish Migration Agency were increased to enhance integration measures (e.g. language initiatives, skills assessments and validation for asylum seekers, reforms to the Swedish for Immigrants syllabus and organisation, and a new fast track for newly-arrived entrepreneurs) (OECD, 2017, p. 234[4]). It bears noting that regional and local actors may also have access to several EU funding streams – such as the AMIF, the European Social Fund (ESF) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) either directly target migration emergencies, or indirectly support integration through social inclusion, education, labour-market-related investments and other infrastructure investments.

Sweden’s subnational governments have relatively low tax autonomy and rely in large measure on transfers from the national government. OECD research has found that multi-year and flexible local funds for integration purposes can increase co-ordination across levels (i.e. regional, national supranational) with the ultimate goal of aligning integration objectives. More autonomy in financing integration at the local level requires that local integration objectives are in line with national strategies alongside mechanisms for assessing the performance and impact (OECD, 2018[2]). In terms of economic resources for migrant integration activities, it was noted that a large share of the resources from the Swedish central government is invested at the local level (with limited local autonomy) and that the wide variety of organisations and institutions involved can create confusion regarding roles and responsibilities and lead to a duplication of efforts. Therefore, while there are many benefits to Sweden’s fiscal framework and funding from the central government has been increased to respond to growing need, there are also some rigidities embedded within the system.

The following activities can help to ensure access to and the effective use of financial resources that are adapted to local responsibilities for migrant integration:

Sound assessments of the costs of services and integration-related activities are needed. Improved data on the presence and characteristics of migrant populations will help the service providers in Småland-Blekinge have a clear dashboard of the areas of spending and estimate future needs.

Co-funding mechanisms can be used in order to incentivise municipal co‑ordination. Bundled un-earmarked multi-year funding for municipalities can help to incentivise co‑ordination for multiple social purposes, including for migration-related programmes. For example, in west Sweden, the EU funded Structural Fund Partnership (SFP) decides on funding and co-ordinates calls for proposals based on specific regional needs or intentions. The SFP is composed of members from Västra Götaland Region as well as neighbouring Halland Region, the county government, the municipalities, labour market stakeholders, universities, the employment agency and civil society actors (OECD, 2018[2]). This may be a structure of interest to Småland-Blekinge to employ.

Funding from the non-state sector should be drawn on more strategically at the local level, exchanging information on needs and proposing innovative solutions. Municipalities are best-placed to create partnerships with different local donors (i.e. private sector, foundations, etc.). For example, in Amsterdam, such strategies were used to hold a convention with 40 big private companies to support refugee access to the labour market (OECD, 2018[2]). In Småland-Blekinge, there are examples of private sector initiatives, such as industry-SFI at several firms, OBOS/Smålandsvillan works actively with integration. However, it was noted that private sector actors could be much more involved in migrant integration in Småland-Blekinge. Such engagement could be strengthened.

Community integration

The importance of early integration is well recognised in the literature (OECD, 2006[17]). Recent research shows that the first 2 to 3 years from arrival have a disproportionally positive impact on the probability of finding a job; this drops by 23% after this time (Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner, 2016[18]). As such, there are high costs to delayed action. Sweden’s record level of asylum seekers in 2015 created a backlog of pending asylum and family reunification cases and placed pressure on various municipal services (social services, schools, etc.) due to growing demand and impacted the length of time that asylum seekers wait for their claims to be heard affects their subsequent economic integration.10 Individuals were delayed in accessing important integration services such as language training and employment support. It is only once a residency permit has been issued that the responsibility for integration is transferred from the Swedish Migration Agency to the Public Employment Service and that individuals can start the two-year Introduction Programme (Etableringsuppdraget) with language classes, upskilling and labour market activities and access to an “introduction” benefit, housing benefit or supplementary benefit (for those with children living at home). Furthermore, individuals cannot start the Introduction Programme until they have obtained a social security number issued by the Tax Agency and the timeframe to obtain this can be lengthy (OECD, 2017[9]).

This issue has largely been resolved by Sweden’s 2016 temporary act restricting the possibility of being granted a residence permit and the right to family reunification; with a reduced number of applicants, files were able to be more quickly processed. At the same time, some efforts have been made to grant asylum seekers access to some integration services (e.g. language training) in advance of obtaining a residence permit as well. Additionally, efforts have been made to better co‑ordinate actions across the key actors involved in migrant settlement. For example, the pilot project Meeting Points and Information, involving among others the Migration Board, Tax Authority, Public Employment Service, Social Insurance Agency, Pension Agency and the Association of Local Authorities and Regions, gathered the most important actors in the settlement process in municipal Service Centres at the same time, with a checklist of processes to be completed (OECD, 2017[19]). The project reduced the process from about four weeks to four hours, improved co‑operation between different institutions and their understanding of the settlement process and increased migrants’ confidence and sense of control of their situation. Public savings due to efficiency gains were found to be substantial. This way of working is to be gradually rolled out nationwide (Social Insurance Agency, 2016[20]). The large gains from reducing the settlement time by only four weeks illustrate the potential to be reaped from streamlining and removing bottlenecks in the asylum, settlement and integration processes (OECD, 2017[19]). Faster settlement means speedier integration and employment, better lives and longer working careers for migrants.

In the longer term, the bottlenecks related to obtaining a residence permit and a social security number and finding housing remain to be addressed. Sweden should work to continue to simplify the procedures to help migrants get residence and work permits and should build on successful experiences at the local level to enhance the efficiency of integration (OECD, 2017[19]). Sweden’s 2016 budget announced that an inquiry is underway in government offices to simplify and streamline the introduction system through reduced administration and increased flexibility (Government Offices of Sweden, 2016[21]). Therefore, progress on addressing this issue would appear to be underway.

Design integration policies that take into account migrants’ lifetimes and status evolution

While the above-mentioned efforts to streamline the processing time are welcome, local authorities still face the decision of whether or not to include asylum seekers among the beneficiaries of local integration measures. Delaying such measures can be a setback to long-term integration, but on the other hand, rejected asylum seekers will have to return to their countries of origin and the host community will not benefit from the potential of these newcomers (OECD, 2017[3]).

Early integration models are being experimented with in municipalities across the OECD, including in Småland-Blekinge, in order to avoid the sequential approach to migrant reception and integration which first builds language, then professional skills, and then start labour market integration – an approach that combines the three stages through on‑the-job language training and part-time courses (OECD, 2017[3]). Several such strategies are noted below, as well as areas for improvement.

There has been improvement in adopting an integrated approach from “Day One” – but stronger use could be made of local networks to assist newcomers. This strategy introduces integration mechanisms that encompass all aspects of a newcomer’s life beyond job integration at the very beginning of migrant arrival, whatever migrant status. For example, In Altena, Germany, all persons with a foreign background who arrive in the city are accompanied in every step from arrival, status recognition and administrative procedures, accommodation to education and integration in the local society by Kümmerer (members of civil society and dedicated municipal counselling services and offers) (OECD, 2018[2]). Municipalities in Småland-Blekinge could make a stronger use of these types of local networks to assist newcomers. One promising initiative is the Swedish from Day One scheme which provides funds to study associations and folk high schools in order to organise language and civic integration training for asylum seekers and refugees living in reception centres. Another best practice to highlight is in the Kalmar region, which on behalf of all the municipalities in the county, run classes in “social orientation” for refugees in 21 languages. It is a 72-hour programme where participants get to know the Swedish societal mechanisms in order to improve their understanding and strengthen their feeling of inclusiveness in their new country and give them better tools for entering the job market (Regionförbundet i Kalmar län, 2018[22]).

There remains a need to multiply the entry points for migrants to access services over time. Migrant-oriented “one-stop shops” can be used to connect beneficiaries to the relevant administrative services or to gain access to in-house services. Some localities within the OECD have delivered this approach through municipal departments (i.e. hiring social workers to counsel migrants, adapting the language capacity of public services, etc.) while others have outsourced this function to the third sector (NGOs, migrant associations) or private companies. For example, Glasgow has a Govanhill Service Hub – a partnership between the local housing association and Glasgow City Council – which offers a range of public and voluntary services to support migrant integration and social cohesion (OECD, 2018[2]). The hub hosts regular meetings between the community and service providers. Public services (such as schools, kindergartens, hospitals, etc.) also provide opportunities to reach out to migrants at different stages of their lives. For instance, municipalities can involve migrants’ parents by organising extracurricular activities at schools (i.e. “parent cafés”, informal learning components for parents with children at school, etc.). Gothenburg has adopted an informal approach. They have a ‘‘refugee-guide and language friend’’ programme where citizens volunteer to offer guidance for newcomers in the city. The programme established a virtual platform and also provides meeting spaces to facilitate the organisation of mentoring programmes or buddy systems by civil society organisations and NGOs (OECD, 2018[2]). In Kronoberg County, the CAB has set up a website in order to help migrants navigate among and explore different activities/programmes to facilitate the integration process (Kronoberg Tillsammans, 2018[23]). Interviewees in Småland-Blekinge noted that many migrants who successfully integrate often do so thanks to the role of volunteer contacts who help them to navigate services. Blekinge CAB has initiated discussions regarding who is best placed to take on this role. The CAB’s view is that responsibility for such assistance is best placed with the authorities who have clear assignments on asylum seeker reception as opposed to the civil sector. It is their opinion that it is the authorities’ responsibility to develop methods to help the newly arrived to navigate services.

There remains room to strengthen the involvement of migrants, research institutions and local organisations who have longstanding experience in receiving newcomers. Småland-Blekinge – like other regions in Sweden – quickly had to build capacity in the most recent wave of migration. It is important to build on existing networks involving research institutes and local organisations in efforts to support newcomers. Local organisations are involved in Småland-Blekinge in receiving newcomers; however, their activities and funding are often limited to such areas as Swedish courses for newcomers. The scope of their roles and regular mechanisms for co‑ordination could be expanded. Efforts in Kronoberg may serve as an example – there, local organisations provide a range of activities with the aim to facilitate the integration process e.g. swimming and biking courses, mentorship programmes, special groups for girls and boys to focus on their specific needs in the process, homework assistance.

One of the potential risks identified by some organisations in Småland-Blekinge that work with migrants is the how the 2016 legislative change which has led to asylum seekers receiving 13-month temporary permits will impact the integration process. This could lead to a level of insecurity that makes it more difficult for people to settle down and focus on integration measures and also places limitations on family reunification. Uncertainty about staying in a country and long asylum processes can increase the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder that complicates a rapid establishment. Furthermore, those with expertise and experience may be less likely to validate their knowledge or initiate additional studies if the process takes longer than the residence permit allows (Cheung, Maria; Hellström, 2017[24]). This is an issue that should be monitored.

Create spaces where the interaction between migrant and native-born communities are physically and socially closer

Municipalities in Småland-Blekinge have a great asset in the sense that they are smaller places with strong community and social connections; however, this could translate also into being less open to others and to diversity. Several municipalities have identified that there is some risk that newcomers are isolated within their own migrant communities, particularly where migrant housing is concentrated in particular neighbourhoods. Ensuring that there are spaces of interaction between migrant and native-born communities is, therefore, an important role for localities, as is accessibility and mobility (e.g. access to reliable transportation). The CAB presently have no tools to prevent or decrease segregation. The national government should provide municipalities with the policy tools and incentives to address physical segregation.

Spaces of interaction exist to a certain degree within public institutions such as schools, but it is important to provide broader opportunities for engagement as well. While funding for civil society organisations through the CAB has helped to promote such efforts – civic events are also important in this regard. Further, the profile of many of Småland-Blekinge’s newest residents is quite young. It is important to improve conditions in communities for young people in terms of amenities and quality of life – efforts which will help with migrant retention and integration in the longer term. One area where the region is seeing some success in this regard is with sports. For example, a number of sports clubs in Småland participate in a project led by Smålands Idrottsförbund, a regional branch of the Swedish Sports Confederation, called “ethnic diversity in sports” (Etnisk mångfald inom idrotten) (Smålandsidrotten, 2018[25]). In Älmhult, the municipality runs a project which provides opportunities for young migrants (aged 13-19) to try different sports for free. These types of “soft project” are important for social cohesion and youth engagement.

Policy formulation and implementation

The region of Småland-Blekinge has had to adapt very quickly to the most recent wave of migration. While lessons from previous waves of migration were certainly helpful in structuring a response, capacity in many cases needed to be built up from scratch, particularly in terms of the services provided by front-line organisations in such areas as health, housing, education and skills. Sweden has adopted a mainstreaming approach to the provision of services to migrants for the most part. This means that the manner in which services are accessed and structured are often the same as that for the population as a whole (with some exceptions). However, the provision of services and front-line interactions to newcomers will often demand a specific sensitivity and cultural awareness. Already to date, over the past few years, there are examples of good practices, capacity building, support to staff and the development of more integrated systems whereby those working with newcomers receive targeted training, help to monitor change and inform policymakers of how things are working on the ground.

A great deal has been achieved in a short amount of time and this should be applauded. However, challenges with policy formulation and implementation remain and moreover, integration can be a very long process, particularly for individuals who have arrived with less transferable or very low skills or who suffer from health issues, including mental health ones. Therefore, while the 2016 reforms have lessened the number of asylum seekers to the region, the demand remains for settlement and integration services and there is a need to cater services to those who may face the greatest obstacles to integration. In particular, there is a need to address the needs of unaccompanied minors who require special support.

Ensure timely data to help anticipate and respond to migration

One of the issues repeatedly raised in Småland-Blekinge is the lack of adequate and timely data on reasons for migrating, education or professional profiles well as future projections (even in the short and medium terms). A lack of timely data was particularly challenging for local authorities at the height of the refugee situation. These issues have since been addressed for the most part. For example, it was reported in Jönköping that data on migration provided by the Migration Office is presently adequate, however, projections for the future are lacking. Such forecasting can be very difficult to achieve, but even a range of scenarios could help local officials better plan for the future and anticipate change. In 2015, at the height of the refugee situation, the data from the national Migration Office was published every day in order to follow developments, but even so, it was difficult to keep the numbers up to date in the database.

Build capacity and diversity in civil service

A large number of new arrivals and asylum seekers in recent years has propelled the need for skills development in a number of areas and for better co‑operation between service delivery organisations. The region’s counties and municipalities initially struggled under this pressure but have since adapted and there are many positive examples of capacity building activities. For example, the labour market units in four of the five municipalities in Blekinge are co‑operating in an ERDF-project called “Personal Inclusion Competence” in order to increase their skills in addressing how immigrants can better be included in the local community and how staff working directly with integration can work more resource- and time-efficiently through increased knowledge, improved structures and better co‑ordination.11

It is noted that workplaces often struggle to provide adequate staff training or to provide an inclusion perspective in their work (Personal InkluderingsKompetens, 2018[26]). Further, staff working new arrivals/asylum seekers can need a wide range of skills which tend to be provided through conferences which are expensive and hence, limit the number of participants that can attend (Personal InkluderingsKompetens, 2018[26]). The Personal Inclusion Competencies (PIK) project seeks to help to overcome these challenges by providing flexible and personalised training through lectures, workshops and supervision to all occupational categories in the workplace and is based on the idea that the work on inclusion should be ongoing and able to develop according to needs. Its efforts are mainly targeted at municipal employees who come into contact with new arrivals and also involves other participants from the private sector and civil society. Competency development is focused in three areas: i) administrative and legal aspects; ii) gender mainstreaming, accessibility and equal treatment; iii) individual-specific dilemma (e.g. helping individuals with posttraumatic stress). The project is presently financed to run for two years (ending 2018).12 The CAB has together with the municipalities and the PIK-project implemented a large number of competency-increasing efforts aimed at this sector in the last couple of years. The challenge now is to put that knowledge into practice and find new, effective ways of working.

Capacity building should not only target public servants engaged in frontline services for migrants, but also all services receiving newcomers: teachers, social workers, police and services in charge of connecting them with the job market (OECD, 2018[2]). It should be clear what obstacles migrants, service providers and employers face and what needs to be adapted. Some practices from across the OECD to highlight include Berlin where a compulsory and basic curriculum guiding schools on how to integrate newcomers was established (OECD, 2018[2]). The framework covers general education from Grade 1 to 10. The new curriculum was adopted in 2017/18 and aims to support schools in managing an increasing number of students with diverse religious, cultural, educational, linguistic and other backgrounds. The framework includes, for instance, specific language promotion in all subjects and intercultural education is included as a compulsory component for general education. As another example, the Education Department of the City of Rome has promoted programmes for pre‑school teachers and day-care staff to improve their intercultural skills. The department also funds the projects Progetto Aquilone (Project Kite) and Accogliere per Integrare (Welcoming for Integrating project) through which cultural mediation is provided by schools (2011/12 school year) (OECD, 2018[2]).

As a final note, it is also important that diversity is built into the public service. Doing so can help to make direct contact with migrants easier, to boost the integration image and expectations from migrants, and to change mentalities among public servants themselves as well as the local society (OECD, 2018[2]). There are different approaches to how this can be achieved. As one example, the City of Berlin has made a diverse public administration the second principle of its integration strategy, called Intercultural Opening (Interkulturelle Öffnung) (Berlin.de, 2017[27]). The strategy is binding in regional law, participation and integration law, and its implementation is monitored based on a set of indicators which are reported to the city’s parliament.

Strengthen co-operation with non-state stakeholders, including through transparent and effective contracts

Outsourcing to NGOs and private partners is widely used to deliver local public services in general and services for migrant integration in particular. Doing so can help access experienced actors for specific integration-related services and can help to diversify service provision. However, there are some risks associated with this approach and there is a need to ensure that co‑operation with non-state actors takes place through effective and transparent contracts that can monitor and assess outcomes and practices. This is of growing importance since interviewees in Småland-Blekinge have noted a trend towards having state-run organisations where the resources are invested in smaller private enterprises (e.g. decentralised services). Cautions regarding how non-state actors are used in integration services are well-heeded in Småland-Blekinge due to recent experiences with a recent countrywide programme that paid individuals to assist newcomers with various aspects of integration.13 The outcomes of this programme were found to be very inconsistent and it was subsequently ended (there is no replacement programme that adopts a similar approach). In Kalmar County, it was noted that, in terms of assessing civil society organisation that works with migrants, there are follow-ups every third month, but that there is no a clear assessment (the process is focused on reporting and a dialogue).

These types of issues are quite commonly faced. One strategy to improve processes and manage risks involving third-party providers is to set service standards within contracts in order to achieve more consistent outcomes. For example, The COMPASS contract, initiated by the Home Office on behalf of the UK national government, was designed to offer accommodation, transport and basic sustenance to asylum seekers through private service providers (United Kingdom Parliament, 2017[28]). The first contract generation created problems, as users, NGOs, municipalities and the Scottish Government in the United Kingdom realised that the quality of services provided by the contracted service providers under COMPASS was poor. In order to address the problems and increase the standard of the service while still serving a high service demand, a changed contract was set up. In the new contract voluntary and private sector landlords provide services during the claim process. However, communication and co‑ordination mechanisms between accommodation operators and local social services require improvement (OECD, 2018[2]).

Sectoral policies

Migrant integration involves a number of sectoral policies that may be regulated, funded, designed, implemented and evaluated at different levels of government. As such, how the various actors in the system work together across these levels, and with external actors, is critical. A feature of the Swedish system of migrant integration is that there are a wide range of actors involved in delivering various programmes and services. This large institutional patchwork is a strength, but it can also be very difficult to understand comprehensively where initiatives are being targeted and where they are making the most impact and to co‑ordinate between levels. Furthermore, the resources and services offered by the multiple actors involved can be challenging for migrants to navigate. Sectoral co‑ordination is also important. For instance, newcomers’ housing placements impact upon their subsequent chances for labour market attachment. In Småland-Blekinge, it has often been the case that those municipalities with the most housing on offer also have the weakest labour markets. This section profiles two sectoral policies that are of chief importance to migrant integration in Småland-Blekinge: i) labour market policies and training and skills assessment; and ii) the provision of adequate housing.

Match migrant skills with education, training and job opportunities

The successful labour market integration of migrants has been one of the most important issues for Småland-Blekinge. The primary agency which addresses this is the Employment Office, which assigns a caseworker for each individual (this person may change depending on the services being accessed) and develops a plan for each new arrival based on their needs. Over the course of 24 months, the Employment Office co‑ordinates access to education and training as needed and assists individuals in having their educational qualifications recognised and their competencies certified. Access to the employment programme commences once individuals have received a residency permit and have housing in the municipality.14 There is very high uptake by newcomers of the services offered by the Employment Agency. It is important to acknowledge that the integration of very low-educated humanitarian migrants requires long-term training and support (OECD, 2016[29]).

Assessments of the Employment Services have found that intensified search and match assistance, job coaching, work experience and subsidised work for migrants are some actions which have led to the most positive labour market outcomes (Cheung et al., 2017[30]). However, robust evaluations of which approaches are working the best are needed. Further, there is a need to improve communications around some existing programmes and how they work. For example, Sweden has an incentive programme to hire migrants wherein the Employment Service will pay 80% of an individual’s salary for a period of time. The uptake of this programme by businesses in Småland-Blekinge has been relatively low. This initiative could be bolstered by improving the communications of this programme and its benefits to employers and profiling some successful examples where it has been implemented.

Both at the national, regional and local levels, a great deal of progress has been made in adapting systems to better support the most recent wave of migrants. However, there remain several areas for which labour market integration policies and services should be strengthened.

Sweden has made efforts to adopt flexible educational pathways. Many of the newly arrived in Sweden may have partial credentials or incomplete and interrupted educational and training. Flexible pathways to education and training help individuals to meet programme requirements in a timely manner and, depending on how this is structured, make it easier for individuals to work while doing so. In recognition of this, Sweden has opened its trainee jobs and vocational introduction jobs scheme to recently-arrived refugees, to allow those with incomplete education to earn a vocational certificate while working part time. This is a very positive development and could be expanded to other educational areas as well.