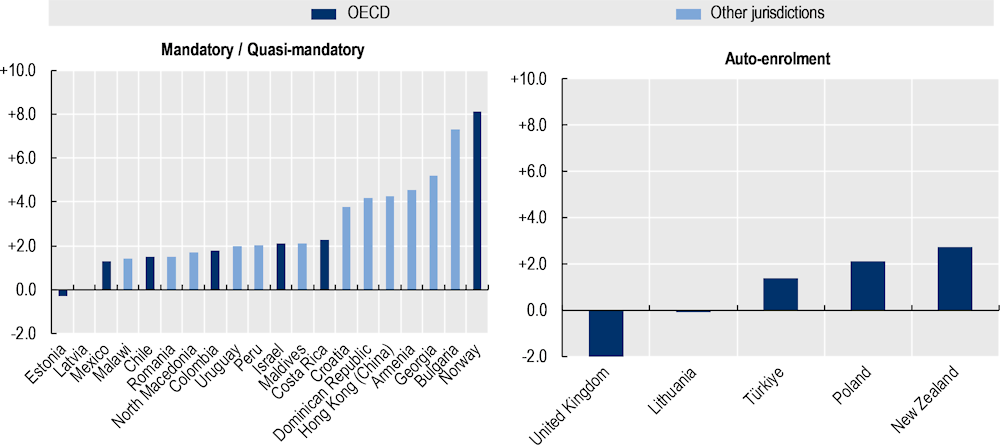

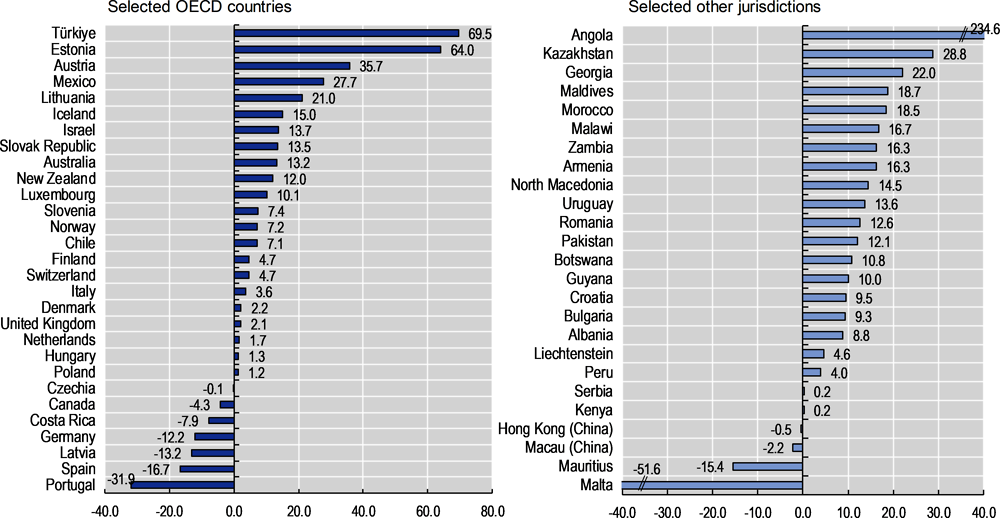

The increase in nominal wages 2022 is also behind the increase in contributions. As inflation was rising in 2021 and most of 2022, nominal wages also rose with a lag, automatically increasing the amount of contributions paid when contributions are defined as a percentage of earnings. This effect was particularly visible on contributions paid in Türkiye where inflation was at 64% at end-2022 and nominal wages increased the most over the period 2019-22 in the OECD area (OECD, 2023[9]).

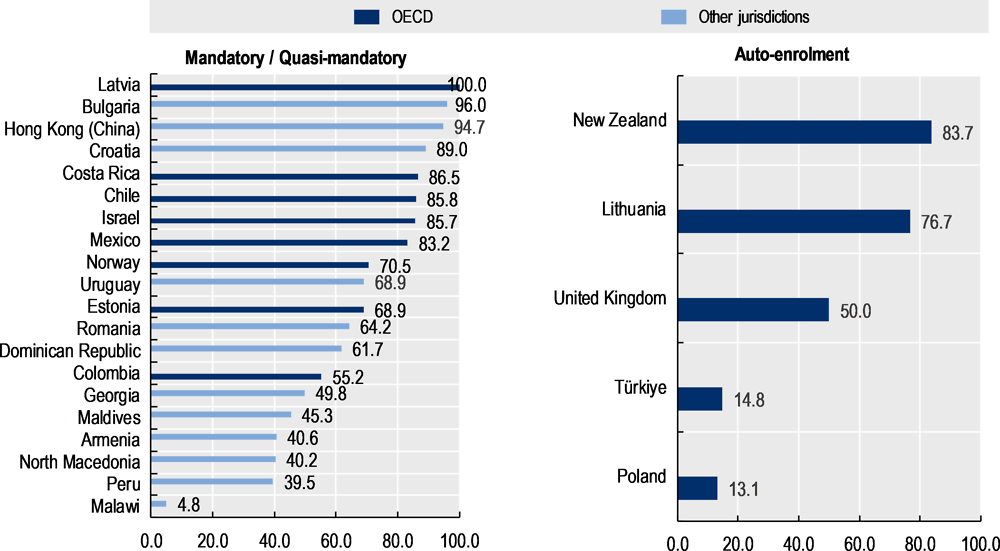

Some policy or supervisory measures may have reinforced the effect of wage growth on contribution levels in some countries. Some countries increased mandatory contributions rates (e.g. Australia from 10% to 10.5% in July 2022, the Slovak Republic from 5.25% to 5.5% in 2022), or simply returned to normal conditions after the suspension or reduction of mandatory contributions granted in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis (e.g. Estonia, Finland) (OECD, 2022[10]).5 Norway expanded the earning base used to calculate mandatory contributions in 2022, requiring all employers to contribute 2% of the salary of their employees from the first krone up to 12G since 1 January 2022,6 while there was often no contribution for salaries below 1G before.7 Some supervisory authorities, especially in Africa, endeavoured to boost compliance with existing mandatory contribution rates to increase contributions. For example, the supervisor in Ghana took legal action against employers who did not comply with the 5% mandatory contribution rate. In Malawi, a part of the 17% increase in contributions in 2022 comes from a reduction in contribution arrears, although there was reportedly still a large amount of outstanding contributions unremitted to pension funds.

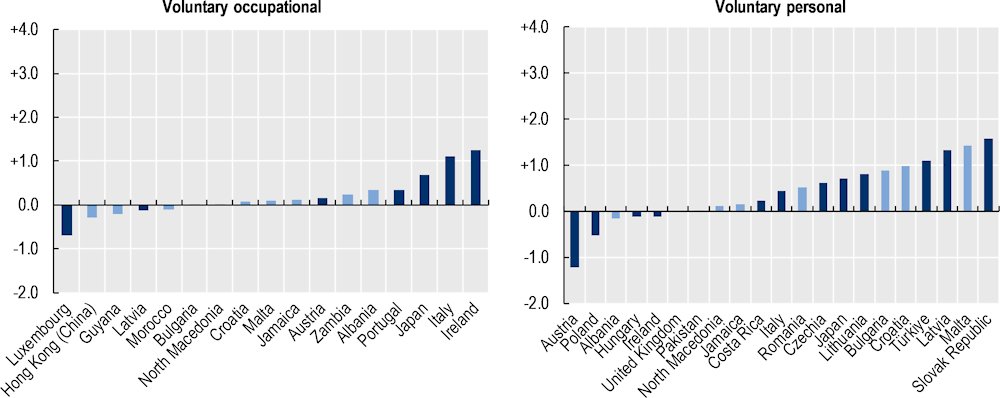

The rise in inflation and cost-of-living may have led some people to delay retirement, making them contribute for longer. According to different studies, the rise in cost of living led 41% of pre-retirees in the United Kingdom and 20% to 40% of older workers in the United States to delay retirement.8 At the same time, it may have also led some people to stop or reduce voluntary contributions, due to the potential lower capacity to save for retirement and the higher priority they gave to other needs. The rise in interest rates following central banks’ attempt to contain inflationary pressures may have also improved the financial position of defined benefit plans in some countries,9 reducing the need for employers to make additional contributions to guarantee the promise, such as in Portugal (-32%).

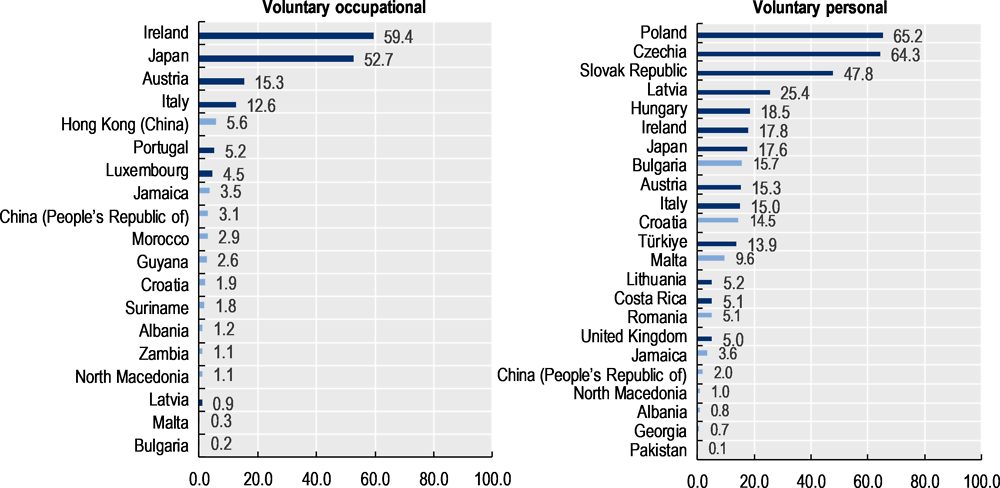

Voluntary contributions to pension plans may also be sensitive to financial incentives. Many countries have financial incentives to encourage saving for retirement. Reducing financial incentives may affect behaviour and reduce contribution levels, such as in Spain where lowering the tax deductibility limit for contributions to personal plans from EUR 2 000 to EUR 1 500 may have contributed to the 17% fall in contributions in 2022, despite the increase in the limit for contributions to occupational plans from EUR 8 000 to EUR 8 500.

The macro-economic developments in 2022, with higher employment rates and nominal wages, but also higher inflation, may have also affected the revenues to finance public reserves. Reserves of the public PAYG pension arrangements are not financed in the same way as pension plans because they do not serve a specific group of members from whom they would receive contributions and to whom they would pay benefits. Public reserves can have multiple sources of revenues. Revenues are the result of the excess of contributions over benefit payments from the public PAYG scheme they support in most cases (e.g. Canada, Finland, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States). The impact of macro-economic developments then depends on how the different factors played out on the PAYG contributions and benefit payments.10 Revenues can also come privatisation, earmarked contributions or tax, special or one-off contribution, and any other fiscal transfer (e.g. in Australia, Chile, France, Poland, New Zealand) (OECD, 2021[11]). In such cases, inflows depend on the willingness to build up reserves, which the economic situation may influence. For example, the contributions to the reserve fund were suspended in 2020 and 2021 in Chile during the pandemic but resumed in 2022 following the economic recovery.