This chapter examines the broad range of EU environmental regulations and directives affecting the farming sector, as well as all the CAP instruments falling in the agri-environmental domain. The assessment of the main EU legislation and policy implemented until 2022 highlights the presence of a gap between the ambition of policy objectives and the results of their implementation. The new CAP 2023-27 embodies changes that address some of the shortcomings observed in past cycles. Similarly, important pieces of legislation that have been recently proposed have a stronger focus on objectives and reporting results and could be an opportunity to improve the effectiveness of policies and to simplify administrative requirements around programme delivery.

Policies for the Future of Farming and Food in the European Union

4. Environmental sustainability

Abstract

Key messages

The European Union (EU) has applied a broad set of regulations and incentives to improve the environmental sustainability of agriculture in the European Union, with different ambitions and mixed results.

The Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) governs non-CO2 emissions linked to agricultural activities. Agriculture is the third-largest source of emissions in ESR sectors but contributed only 1% of the emissions reduction effort; EU Member States are not projecting significant emissions reductions in the agricultural sector by 2030.

The 2000 Water Framework Directive has not achieved its original objective of restoring all surface and water bodies to good status by 2015; doing so by 2027 remains challenging.

The Nitrate Directive has been in place for over 30 years, but nitrogen surpluses from agriculture are still a problem affecting surface and groundwater quality.

The 2009 Sustainable Use of Pesticides Directive (SUD) provides Member States with many tools for reducing the risks of pesticide use. However, imprecise targets and poor monitoring have made it difficult to assess its benefits. The new proposed Sustainable Use of Plant Protection Products Regulation addresses some of the shortcomings of the SUD and provides a stronger connection to the European Green Deal’s (EGD) targets on pesticide use.

The Birds and Habitats Directives have played a major role in nature and biodiversity protection in the European Union, but the targets are not strongly enforced. The proposed Nature Restoration Law brings the objectives of these directives into the modern era, with more quantified targets, stronger obligations on Member States, and a more integrated connection with EU environmental policy and the EGD.

Environmental objectives have been progressively included in the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) since the 1992 MacSharry Reform, including both voluntary and compulsory environmental compliance for farmers.

Cross-compliance can potentially have a positive impact on the environment by encouraging the development of more sustainable agricultural practices, but evaluation of the measure is incomplete and the inspection rate and penalties are low.

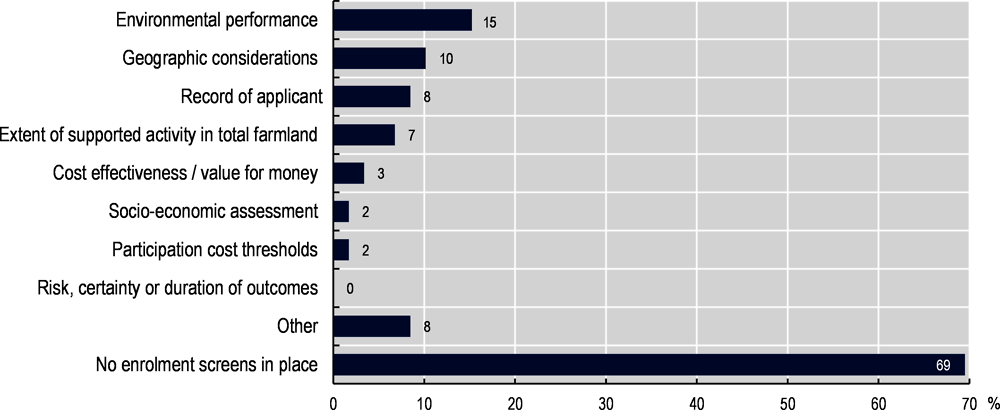

Agri-environmental schemes (AES) are targeted measures to encourage environmental practices that provide significant beneficial outcomes, but their effectiveness depends on voluntary participation, suitable monitoring and sufficient funding. Result-based and collective AES hold promise but are not yet widely diffused.

The new CAP 2023-27 embodies many changes that address the shortcomings observed in past CAP cycles. A stronger focus on objectives and reporting results can be an opportunity to simplify administrative requirements around programme delivery.

This chapter looks at EU policy that has been in place to date with respect to the sustainability of production, conservation of resources and production of ecosystem services. The major arms of EU policy in this agri-environmental domain are the many directives aimed at or strongly affecting the sector, cross-compliance, the greening elements of Pillar 1 of the CAP and AES in Pillar 2. Section 4.1 provides a short overview of the recent development of EU regulations and policies. Section 4.2 deals with environmental regulations and directives, beginning with climate change policies and covering the Water Framework Directive, Nitrates Directive, Sustainable use of Pesticides Directive, and Birds and Habitats Directives. Section 4.3 covers those CAP measures having to do with environmental sustainability, in particular cross-compliance, green direct payments, AES and eco‑schemes.

4.1. The EU legislative and policy landscape is evolving

Recognising persistent environmental and climate challenges at European and global scales, European environmental and climate policy making is increasingly driven by long-term sustainability goals (EEA, 2019[1]). While progress has been made in many respects, much remains to be done to achieve the European Union’s long-term vision to 2050 of living well, within planetary boundaries.

Farmers have a vital role in preserving, managing and enhancing biodiversity in the 39% of the EU area in agricultural land use. At the same time, certain agricultural practices are a key driver of biodiversity decline. Nature regulates the climate, and nature-based solutions, such as protecting and restoring wetlands, peatlands, and coastal ecosystems or sustainably managing forests, grasslands and soils, will be essential for reducing emissions and adapting to climate change.

Agricultural activities are important factors in achieving policy objectives across a range of areas. These include the objectives of the EU nature legislation and the EU and global Biodiversity Strategies for 2030. The United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP15), on 19 December 2022, ended with the agreement called “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (CBD, 2022[2]).1 Additional environmental objectives relevant for agricultural activities are related to air pollution (National Emission Ceilings Directive), greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Effort Sharing Regulation and the LULUCF Regulation on Land Use, Land-use Change and Forestry) and water quality (Water Framework Directive and Nitrates Directive). Agriculture also has a key role to play in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 2 – Zero Hunger, and for Europe, SDG 12 – Responsible Production and Consumption (EEA, 2019[1]). The Farm to Fork (F2F) Strategy, part of the EGD, has sustainable production and consumption of food as part of its six targets. See Chapter 2 (Section 2.3.6) for a discussion of the main food system initiatives where legislation is foreseen.

Over the last two decades, EU agriculture continued its evolution towards fewer and larger, more intensive production units (Chapter 2) and achieving environmental targets has been a challenge, particularly concerning improving biodiversity on agricultural land (Chapter 1). Early gains in water, soil and air emissions have been followed by relatively slow progress, which has pushed the attainment of objectives, such as expressed in the main EU environmental regulations. A substantial body of existing legislation governs how the agricultural sector interacts with its environment. Progress under the objectives set by each has been mixed, with substantial progress in some areas but generally less than the initial targets. Biodiversity, in particular, has been challenging, while objectives for water quality improvements are also taking longer than expected. In response, a number of new initiatives have been put in place.

The “implementation gap” between ambition and action is one reason progress has been slow. Flexibility mechanisms designed to help bring about agreement in the sometimes-challenging negotiations process and to reflect the different situations in Member States have weakened efforts as farmers and Member States choose approaches that are less costly and easier to implement but offer limited improvements to sustainability. Better reporting on progress has become an effective tool to balance flexibility with achieving ambitious targets, as it provides an incentive to take meaningful action. This is expected to take on a more important role as objectives are made more specific so that progress can be better evaluated.

This implementation gap has many causes, and systematically assessing and addressing these can improve the effectiveness of EU policy. Action is being taken on a number of fronts to improve the design and application of programmes, use objectives and targets to drive progress, and make better use of data and analysis to increase transparency and refine policy design. Many of these actions are described in this chapter.

The European Union has recently established its 8th Environmental Action Programme (EAP), which reiterates the long-term vision to 2050 of living well within planetary boundaries. It sets priority objectives for 2030 and the conditions needed to achieve these. Building on the EGD, the action programme aims to speed up the transition to a climate-neutral, resource-efficient economy, recognising that human well-being and prosperity depend on healthy ecosystems. The EAP identifies the enabling conditions needed to achieve the priority objectives. Among these is the need for full implementation of existing legislation.

In July 2021, the European Union adopted a Climate Law that increases the ambition for GHG emissions reductions in 2030 from 40% to net 55% compared to 1990 levels. Legislative proposals for a revised Effort Sharing Directive and a revised LULUCF Directive are under negotiation.

As highlighted in Chapter 1, the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 is also part of the EGD. It aims to put Europe’s biodiversity on the path to recovery by 2030 by addressing the main drivers of biodiversity loss, putting in place an enhanced governance framework, and filling any policy gaps while at the same time consolidating existing efforts and ensuring the full implementation of existing EU legislation. It proposes setting legally binding EU restoration targets and restoring significant areas of degraded and carbon-rich ecosystems by 2030 (Box 4.1).

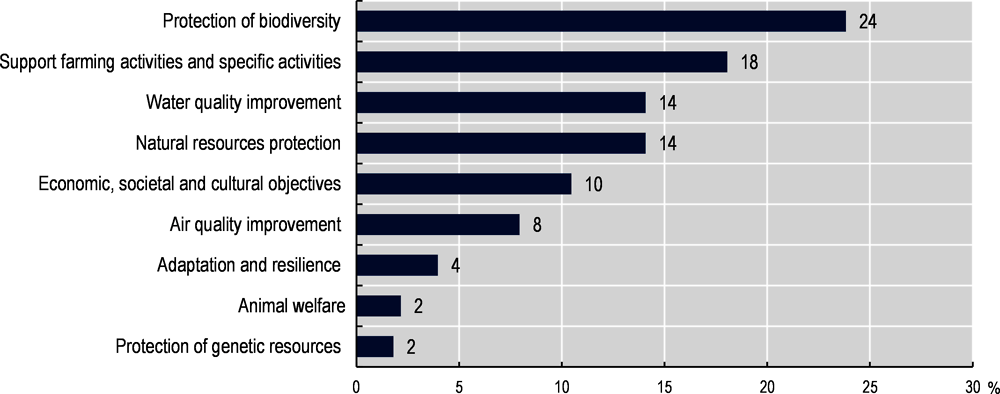

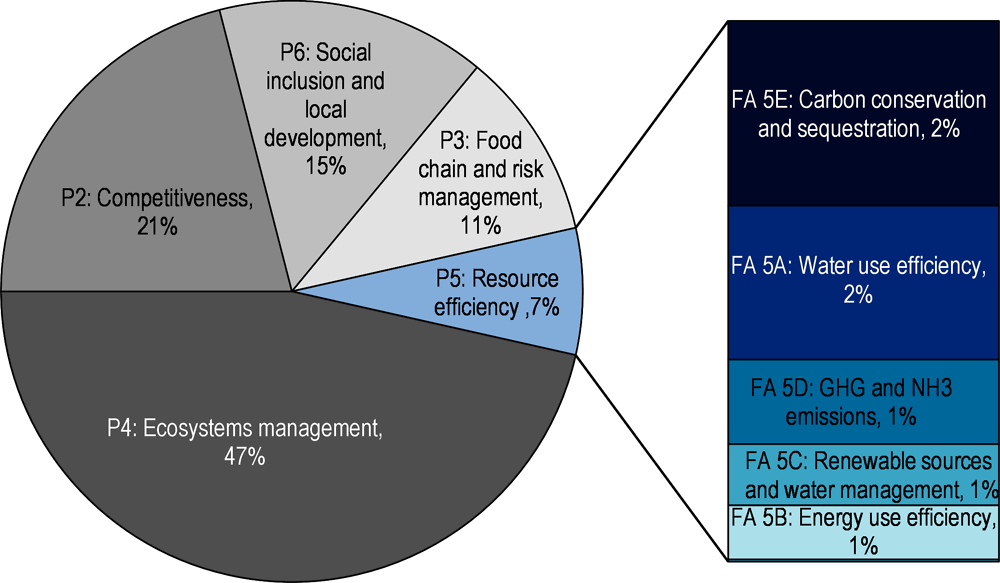

To support the long-term sustainability of both nature and farming and to operationalise the objectives of the F2F and Biodiversity Strategies, the CAP 2023-27 includes a new “green architecture” with higher environmental requirements in cross-compliance (“enhanced conditionality”) and the introduction of eco-schemes in the first pillar. Eco-schemes aimed at climate, environment and animal welfare reward farmers who manage land in a nature- and climate-friendly way. The CAP Regulation requires each eco-scheme to cover at least two areas of action for the climate (mitigation and adaptation), the environment (protection or improvement of water quality, reduction of pressures on water resources, prevention of soil degradation, soil restoration, improvement of soil fertility and nutrition management, protection of biodiversity, conservation, restoration of habitats or species, reduced or sustainable use of pesticides), animal welfare and anti-microbial resistance. As discussed in Chapter 3, the new CAP also includes a new delivery model, granting more flexibility to Member States, requiring them to develop CAP strategic plans (CSPs) and delineating how they will set and implement targets.

For the new funding period, ring-fencing rules on spending have also been introduced: 40% of the CAP budget should be climate-relevant, with at least 25% of the budget in the Pillar 1 allocated to eco-schemes and at least 35% of funds in the Pillar 2 allocated to measures supporting climate, biodiversity, environment and animal welfare.

Sections 4.2 and 4.3, together with the assessment of the main EU legislation and policy implemented until 2022, also provide an overview of the most important pieces of legislation that have been proposed recently (e.g. the proposal for a revision of the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Directive, the proposal for EU Nature Restoration Law), as well as an overview of the new policy measures introduced with the new “green architecture” of the CAP 2023-27.

Box 4.1. The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030: Bringing nature back into our lives

The Biodiversity Strategy lays out targets and plans for Member States’ protected areas under the Nature Directives. These include:

legally protect at least 30% of the European Union’s land area, of this, at least a third is strictly protected, and effectively manage all protected areas

create a coherent ecological network between protected sites to prevent genetic isolation, allow for species migration and climate adaptation, and maintain and enhance healthy ecosystems

ensure that there is no further deterioration in conservation trends and status of all EU protected habitats and species by 2030 and that at least 30% of species and habitats not currently in a favourable status reach that category or show a strong positive trend by 2030

increase the number of forests and improve their health and resilience

create a new European biodiversity governance framework

unlock at least EUR 20 billion a year for nature.

Source: EC (2020[3]).

4.2. Environmental regulations and directives

EU policy with respect to agriculture and environment comprises a package including directives that set rules, practices and objectives influencing the way agriculture production is carried out, combined with the budgetary support and additional regulatory requirements contained in the CAP regulation. The elements of this package must be taken together to understand the full picture of agri‑environmental policy in the EU context. As shown below, many of these elements have synergies or interact with each other. For example, some part of CAP spending is used to help farmers comply with the requirements of certain directives. Cross-compliance, in particular, where statutory management requirements (SMR) are connected with the specific requirements of certain directives, is an example of how the different elements of the whole policy package can reinforce each other. This section covers those EU Directives that are most relevant to agriculture operations.

4.2.1. Effort Sharing Regulation (2018/842) and LULUCF Regulation (2018/841)

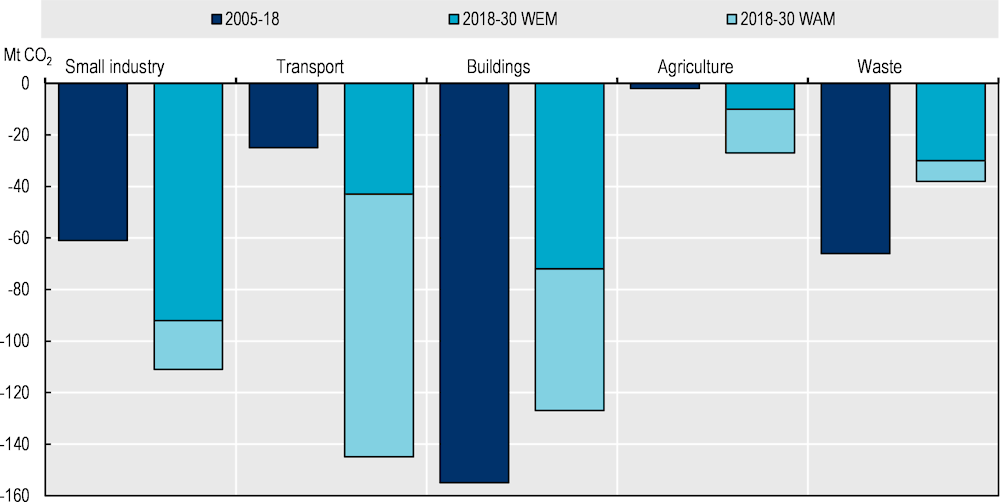

Formerly the Effort Sharing Decision, the Effort Sharing Regulation 2018/842 sets legally binding GHG emissions targets for 2030 for emissions from sectors not included in the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), including transport, buildings, small industry outside the ETS, waste and agriculture sectors. The combined emissions of these sectors represent 57% of the European Union’s total emissions (EEA, 2021[4]). For the agricultural sector, the ESR governs non-CO2 emissions linked to agricultural activities (methane and nitrous oxide), which account for ~98% of the sector’s emissions. Under the Fit for 55 proposal, the overall ESR reduction target for 2030 was increased from 29% to 40% compared to 2005.

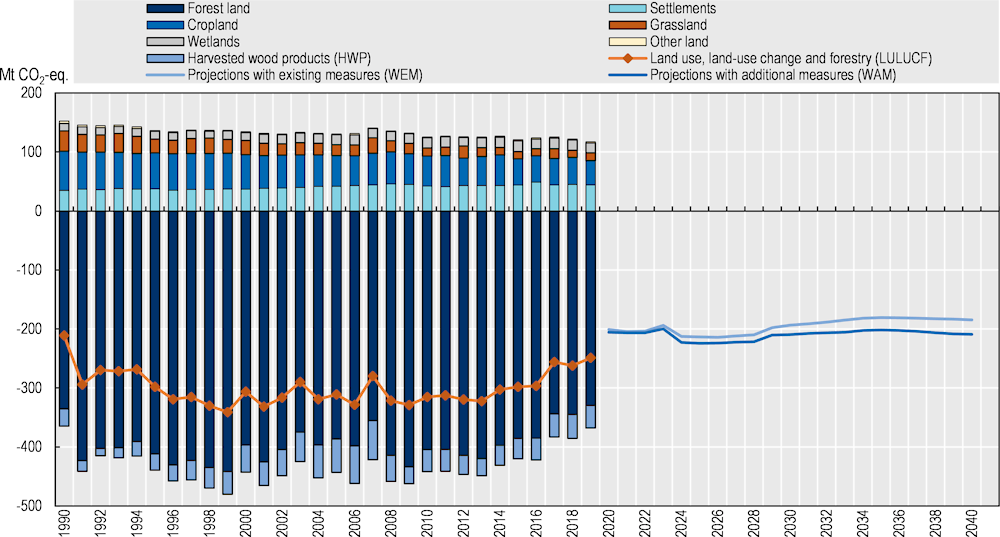

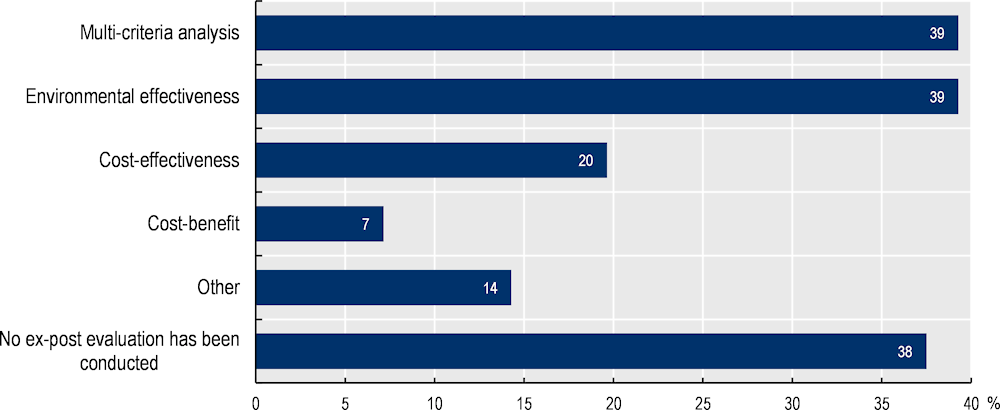

Member States choose where and how to achieve their ESR reductions and may focus on specific sectors. This results in differences between the sectors covered under the ESR. Emissions governed under the ESR declined by ~11% between 2005 and 2018 (EEA, 2021[4]). However, agriculture (the third largest source of emissions in ESR sectors) contributed only 1% of the emissions reduction effort, despite contributing more than 17% of ESR sectors’ GHG emissions. Furthermore, EU Member State governments are not projecting significant emissions reductions in the agricultural sector by 2030, choosing instead to focus on other ESR sectors (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Past and projected Effort Sharing Regulation sectors’ greenhouse gas emissions reductions, 2005-18 and 2018-30

Notes: MT CO2: million tonnes carbon dioxide. EU28. The bars represent changes in emissions between 2005 and 2018 and 2018 and 2030 based on inventories, approximated estimates for 2018 (proxy) and projections “with existing measures” (WEM) and “with additional measures” (WAM).

Source: EEA (2021[4]).

Under the ESR, Member States report on their annual emissions, projected progress towards meeting their emission limits, and information on planned additional national policies and measures to meet commitments. Member States not meeting their annual targets (after flexibilities are included) face an automatic penalty and must submit a corrective action plan. Flexibilities allowed under the ESR were designed to allow targets to be more cost-effective and include banking, borrowing and transferring emissions allocations and the use of ETS allowances and LULUCF credits to cover ESR obligations (under certain conditions).

The European Union’s LULUCF Regulation (2018/841) establishes a legislative framework for accounting emissions and removals from the land-use sectors between 2021 and 2030. Under the current framework, Member States must ensure that accounted CO2-eq emissions from the LULUCF sector are entirely compensated by an equivalent removal of CO2-eq from the atmosphere through action in the LULUCF sector. This is calculated as the sum of total emissions and total removals in all of the land accounting categories defined in the LULUCF Regulation. This is referred to as the “no-debit” rule”. The regulation includes six categories of land in its accounting: 1) afforested land; 2) deforested land; 3) managed cropland; 4) managed grassland; 5) managed forest land; and 6) managed wetland. However, it does not include non-CO2 emissions from the agricultural sector in its accounting as they are covered in the ESR.

The main source of GHG emissions in the LULUCF sector is cropland, of which approximately 50% are caused by organic soils, which is 1.2% of the total cropland area (Böttcher and Hennenberg, 2021[5]) (Figure 4.2). Emissions from organic soils come from the drainage of peatlands for agricultural or forestry use. Approximately 35 million hectares of EU27+UK peatland area is drained (Joosten, Tanneberger and Moen, 2017[6]), at least 6 million hectares of which is agricultural land under grassland or cropland (Schils et al., 2008[7]). Besides emissions from drained organic soils, there are also significant emissions from the loss of soil organic carbon in mineral soils.

Figure 4.2. LULUCF sector emissions and removals in the European Union, and predicted net sink level, 1990-2040

There is potential for the agricultural sector to play an important role in meeting the 2030 sink target. While increasing carbon stocks in forests provide the largest absolute potential for strengthening the European Union’s carbon sink, there are promising options in agroforestry, restoring wetlands and the conservation of organic soils, as well as for maintaining and enhancing carbon in mineral soils.

Carbon sinks in the LULUCF sector will play an important role in meeting climate neutrality objectives. The current LULUCF Regulation includes flexibilities to help Member States account for uncertainties, natural disturbances and reduce the risk of non-compliance. This includes the ability to exchange units between Member States and for individual Member States to exchange remaining units of LULUCF credits to the ESR. The flexibility is capped at 280 Mt CO2-eq for all Member States and national maximum amounts.

The European Commission has proposed revisions to the LULUCF Regulation that establish a net carbon sink target for the LULUCF sector of 310 Mt CO2-eq by 2030.2 Other proposed changes to the LULUCF Regulation would merge the LULUCF sector with non-CO2 emissions from agriculture within the regulation’s accounting system by 2031, which will become the agriculture, forestry and other land-use (AFOLU) sector. This parallels the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report on Climate Change and Land, which merges agriculture, forestry and other land use together. Further, the European Commission proposes a GHG neutrality target for the combined AFOLU sector by 2035.3 While the EU-level target of climate neutrality for the land sector by 2035 is non‑binding, derived Member State targets will be binding and enforceable. From 2036 onwards, the combined sector will need to generate further carbon removals to balance remaining emissions in other sectors based on a robust carbon removal certification system. While the proposed updates have yet to be adopted, trilogues for the LULUCF Regulation have been completed and the Council and Parliament confirmed the overall EU-level net sink target for 2030. Under the provisional agreement, the current “no-debit” rule will continue to apply until 2025. The agreement maintains flexibilities for Member States encountering difficulties in achieving their targets caused by natural disturbances up to a fixed limit.

LULUCF sector GHG emissions total 136 Mt CO2-eq and removals were -410 Mt CO2-eq. Agricultural GHG emissions total 435 Mt CO2-eq. If the LULUCF sink is still at the proposed 2030 target of -310 Mt CO2-eq in 2035, agricultural non-CO2 emissions would need to be mitigated by nearly 20% (Böttcher and Hennenberg, 2021[5]). However, according to data submitted by Member States to the European Environment Agency, the combined emissions from cropland and wetlands are only expected to decrease from 77 Mt CO2-eq in 2020 to 65 Mt CO2-eq in 2040, with existing measures. Emissions from grasslands are predicted to increase from 11.9 Mt CO2-eq in 2020 to 15.2 Mt CO2-eq in 2040.

4.2.2. Water Framework Directive (2000/60)

The Water Framework Directive (WFD) is at the centre of EU water policy.4 It updates and brings together past directives related to water and provides a legislative framework for a consolidated approach to water policy. The WFD aims to:

prevent further deterioration of, protect and enhance the status5 of water resources

promote sustainable water use based on the long-term protection of water resources

enhance the protection of and improve the aquatic environment by reducing the presence of priority substances

ensure the progressive reduction of pollution of groundwater and prevent its further pollution

contribute to mitigating the effects of floods and droughts.

The WFD improves upon past legislation in many ways, but two major innovations over past approaches are worth highlighting. The first is to align water governance with the physical dimensions of water basins by establishing river basin management districts (Article 3). Each district produces a river basin management plan (RBMP), covering a period of six years. The second innovation was taking a Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response approach that emphasised identifying anthropogenic pressures on water systems and asking river basin management districts to produce a programme of measures (PoM) to address these directly. This approach brings together consideration of sources of pollution or abstraction of hydro-morphological pressures and the resulting quality of the aquatic environment, which had previously been treated as separate domains. The WFD’s governance mechanism is designed to enable Member States to bring together all the relevant actors to set up management plans based on river basins and to collaborate across borders.

The objectives of the WFD are ambitious and outcome-oriented, calling for a return to good status for all surface and groundwater bodies by 2015 (Article 4). Good status follows a strict “one out, all out” definition that requires all indicators of status to be good for the overall status of the water body to be considered good. This includes good status for water quality and quantity considering both surface and groundwater. Less than half of water bodies achieved good status by 2015, but provisions allow for two further planning cycles (2015-21 and 2021-27) that extend the deadline to 2027 under certain conditions.

Monitoring and reporting under the WFD have significantly increased knowledge of the European Union’s aquatic ecosystems, with beneficial spillovers in other policy domains. Monitoring trends of certain pollutants has, for the first time, provided Member States with the necessary information to manage the presence in the water environment of pollutants which are not or no longer authorised, e.g. from illegal use or run-off (EC, 2019[9]).

The WFD has a broad focus on the ecosystem and chemical status of surface water and the quantitative and chemical status of groundwater. While it lists a set of priority substances requiring special attention, it is up to river basin management districts to identify and address all anthropogenic pressures affecting the status of water bodies.6 The WFD also requires Member States to establish a register of areas that require special protection under other legislation, such as Natura 2000 sites (Article 6).

The WFD provides for three separate but related activities: 1) a framework for planning and governance (Article 5); 2) a system for monitoring and reporting of water quality (Article 8); and 3) a PoM based on an analysis of pressures on the water body to achieve the good status objective (Article 11). In addition, Article 9 requires the use of cost-based pricing for the delivery of water services.

The PoM consists of a common set of basic measures, along with additional supplementary measures if needed to achieve the objectives of Article 4. Basic measures encompass controls of water abstraction or potential pollution sources that may be detrimental to the status of a water body and mainly reflect the source control requirements of prior water legislation (such as the Nitrates Directive, covered below). The supplementary measures reflect the outcome-based objectives of the WFD. If the analysis shows that the basic measures are insufficient to achieve good status for a water body, supplementary measures are designed to bridge the gap. This combined approach of basic and supplementary measures brings together traditional source controls with outcome-based management.

The WFD was a larger institutional challenge than expected

The WFD was a breakthrough in water policy in Europe and resulted in improvements in many areas (Gruère, Ashley and Cadilhon, 2018[10]). In particular, ecological assessment, monitoring and reporting on water quality have been greatly improved (Carvalho et al., 2019[11]; EEA, 2018[12]). The river basin-based governance structure and integrated approach to addressing pressures were initially very challenging for the existing water management system to adapt to, but great progress was made after an initial slow start and the value of this structure is becoming clear (Voulvoulis, Arpon and Giakoumis, 2017[13]; Jacobsen, Anker and Baaner, 2017[14]; EC, 2019[9]).

WFD implementation is complex due to the need for measures that reflect the specific circumstances of each water body. This complicates the transparency and accountability of Member States and may have allowed lowered ambitions in their water policy. The extensive requirements for the river basin management plans and public consultation are designed to counteract this policy discretion via public transparency about water policy and actions (EC, 2019[9]).

The WFD has not achieved its original objective of restoring all surface and water bodies to good status by 2015 and doing so by 2027 remains challenging in many cases. Problems with implementation are a significant factor. The challenge in the first WFD cycle was to adapt existing governance structures to the new spatial scale of the river basin district and establish PoMs (Borowski et al., 2008[15]). The second cycle of the WFD improved the quality of monitoring and established a systematic approach to identifying all relevant pressures and designing and implementing appropriate measures as a main challenge (EC, 2015[16]; EC, 2019[17]).7 In the latest cycle, sector co-ordination and aligning sector policies with WFD objectives – “mainstreaming” water policy – and the appropriate level of financing for measures are the main gaps (EC, 2021[18]).

Agriculture is a major pressure on water quality

Agricultural activity is a major driver of pressure on water quality and quantity and a factor behind many water bodies’ failure to achieve good status (EC, 2015[16]). In general, RBMPs do not show determined action to address agriculture pressures nor satisfactory association of farmers to the WFD process, and WFD PoMs rarely intervene directly in the emission of nutrients or pesticides (EC, 2012[19]; Wiering, Boezeman and Crabbé, 2020[20]). Additionally, EU funds have been underused in funding supplementary measures under RBMPs (EC, 2015[16]).

PoMs rarely include agriculture directly, nor does the CAP fully integrate the European Union’s water policy objectives. Better integration of water objectives in agriculture policy is needed, but it has not yet happened at the scale necessary (EC, 2019[9]; Zingraff-Hamed et al., 2020[21]). Past delays in establishing RBMPs and PoMs are likely affecting the pace of integration of the WFD and the CAP. The European Commission anticipated that the basic measures in RBMPs would be part of cross compliance once these are fully implemented in all Member States and the obligations directly applicable to farmers identified (ECA, 2014[22]), but it took until the CAP 2023 27 to achieve this. The new CAP requires Member States’ CSPs to contribute to and be consistent with legislative acts concerning the climate and environment. It also provides for payments for area-specific disadvantages arising from farmers’ obligations under RBMPs (Article 72).

Financing availability, efficiency and effectiveness are limiting factors

Financing constraints are a major limitation in achieving WFD goals, while potentially related CAP expenditures on the environment are often inefficient and deliver limited results (ECA, 2017[23]). Both of these challenges can be addressed via closer integration of WFD objectives and agricultural policy (including the Nitrates Directive) (Ribaudo and Shortle, 2019[24]; EC, 2019[9]). Most Member States recognise the contribution of the Nitrates Directive implementation but only in qualitative terms, not assessing how much it will close the gap to good status or how much additional effort is needed (EC, 2015[16]).

Voluntary approaches such as agri-environmental and climate measures may not reach the polluters affecting a water body, and subsidy-based programmes can have a limited impact due to public budget constraints and a lack of environmental regulations on diffuse pollution (OECD, 2017[25]). At the same time, direct measures in nutrient action plans (NAPs) as part of the Nitrates Directive have not been sufficient to address nutrient pollution that prevents water bodies from reaching good status (Wiering, Boezeman and Crabbé, 2020[20]). The third WFD implementation report on the first cycle of RBMPs called for a better balance between voluntary actions and mandatory measures in agriculture to provide a solid baseline for rural development programmes and cross-compliance water-related requirements (EC, 2012[19]).

The principle in the WFD of using supplementary measures when basic measures are insufficient to reach the objectives of the WFD is highly relevant for agricultural policies related to water pollution by nutrients. While some Member States have quantitatively assessed the pollution loads from agriculture, few have estimated the reduction needed to achieve good status according to the WFD (EC, 2015[16]). NAPs under the Nitrates Directive specify actions and restrictions that farmers must follow that are considered appropriate practices, and greening and agri-environmental and climate measures as part of the CAP are designed around beneficial actions that farmers can take for a number of environmental issues, but there is no adjustment mechanism in place if results fall short of targets beyond the multiannual planning cycle.

Monitoring and reporting are important drivers of progress

The regular reporting requirements of directives are a strength. The WFD has stimulated an enormous portfolio of new ecological assessment methods, which have greatly improved the monitoring and assessment of the ecological status of water bodies. These assessment and monitoring methods have also greatly improved the knowledge of the status of European waters (Giakoumis and Voulvoulis, 2018[26]; EC, 2019[9]).

However, the reporting time frames do not always allow for the most up-to-date information to be used in the policy development cycle.8 For example, the sixth implementation report of the WFD was released at the end of 2021, near the end of the second (2015-21) cycle of the WFD, but uses data from the 2018 mid-term evaluation (EC, 2021[18]). At the same time, by the end of 2021, the RBMPs for the third cycle (2021-27) were largely complete and likely did not benefit from the sixth implementation report. More frequent stocktaking of progress could help ensure that any needed adjustments can be made in a timely manner to ensure a successful outcome. At this stage, a three-year reporting lag represents more than half the remaining period up to 2027.

Economic measures are under used

Article 9 of the WFD requires Member States to take account of the principle of cost recovery for water services, including environmental and resource costs, in accordance with the polluter-pays principle. This article emphasises not only sharing costs between water users, but also using water pricing to ensure that the right incentives for water use and conservation are in place. Member States may decide to not apply cost recovery or water pricing but must ensure that this does not compromise the objectives of the WFD. The decision must be explained in the RBMP.

Relatively less progress has been made in implementing the cost recovery and pricing requirements of the WFD. In some Member States, in some sectors, such as agriculture or households, metering of water consumption is not fully implemented. Cost recovery is implemented, to a greater or lesser extent, in households and industry. Cost recovery is not sufficiently applied to water users in agriculture; in many areas, water is charged only to a limited extent (EC, 2012[19]) This situation has not progressed much in recent years in some Member States (as is the case for some non-EU OECD countries) (Gruère, Shigemitsu and Crawford, 2020[27]).

Early in the WFD process, the European Commission had started infringement procedures against some Member States for a narrow interpretation of the cost recovery provisions of Article 9 (EC, 2012[19]). Since then, a few Member States have upgraded their water pricing policies, but significant gaps remain in translating these into concrete measures and achieving more harmonised approaches to estimating and integrating environmental and resource costs (EC, 2019[17]). In the case of agriculture, there is generally a low level of cost recovery of irrigation water pricing. The price paid by irrigators is generally lower than the price required to achieve cost recovery (EEA, 2013[28]).

4.2.3. Nitrates Directive (91/676)

The Nitrates Directive (ND) is the main tool for protecting water threatened by nitrate contamination from agricultural activity.9 Article 1 aims to reduce and prevent water pollution caused or induced by nitrates from agricultural sources.10 The directive refers to both ground and surface waters (including coastal and transitional waters). While many nature-related directives concern agriculture, the ND primarily concerns agriculture emissions.

Member States designate nitrate vulnerable zones pursuant to Article 3, which include areas in which groundwater contains or could contain more than 50 mg/L nitrate without measures or where surface water is eutrophic or could become eutrophic without measures or drains into vulnerable zones.11 For these vulnerable zones, Member States draw up nitrate action programmes containing measures to achieve the objectives set out in Article 1. These action programmes concern good agricultural practice and other specific measures as set out in the annexes of the ND. These action programmes are assessed every four years based on monitoring of ground and surface water quality.

The Nitrates Directive contributes to achieving WFD targets by reducing nutrient loads on ground and surface water by agriculture. The ND uses the Emission Limit Values approach, restricting pollutant loads discharged into the aquatic environment via management controls. However, this approach lacks an equivalent of the WFD’s supplementary measures to ensure results are achieved, and so it is less effective in achieving its aims (Giakoumis and Voulvoulis, 2018[26]).

The directive’s objective is to “reduce pollution”, but there are no exact thresholds to be achieved for surface water resources and no specific target dates. The ND establishes planning and measurement processes in Member States and requires them to identify a set of practices to reduce the amount of nitrogen entering the environment, especially in nitrate-vulnerable zones. While the ND identifies a set of good agricultural practices (Annex II) and a list of measures for Member States to implement (Annex III), these annexes identify subject areas only, leaving the specific parameters to Member States.12 One of the few specific requirements is the limit of 170 kg N/ha from manure (though derogations are possible).

Despite the ND having been in place for over 30 years and many Member States now implementing their seventh nitrate action programmes, N surpluses from agriculture are still a problem affecting surface and groundwater quality, with negative effects on Member States’ ability to achieve WFD objectives of good chemical and ecological status of water bodies and increasing problems in drinking water production. Between 2012-15 and 2016-19, the total area of nitrate-vulnerable zones increased by 14.4% and eutrophication remains a problem for inland, transitional, coastal and marine waters. Many Member States still have a large share of eutrophic waters (EC, 2021[29]).13

A lack of binding targets slows progress

The ND is an older directive and lacks the clear timelines and objectives of newer legislation. That said, when put in place, it was a significant advancement in co-ordinated environmental policy at the EU level (Gruère, Ashley and Cadilhon, 2018[10]). It has established a reporting framework that has increased the amount of information available on the status and effects of nitrogen on ground and surface water. Moreover, new projects like NAPINFO bring this information together from all Member States in a coherent way. This, combined with WFD reporting, has provided a much clearer picture of nutrient pollution and water quality than would otherwise have been possible.

The situation has improved since the directive was adopted, but improvement has been slow since 2012. The low-hanging fruit have been collected and now more challenging measures are needed (EC, 2021[29]). Continual problems with water pollution from agriculture point to the inadequacy of current efforts as part of the nitrate action programmes to address sources of nutrients. In many cases, eutrophication and phosphate pollution are not sufficiently taken into account when identifying and designating polluted areas. While the ND requires that Member States take action when water quality does not improve, not all apply additional measures with sufficient ambition. Between 2016 and 2019, the European Commission opened ten infringement cases against Member States with respect to the designation of NVAs, their action plans or derogations. Most of these have been resolved (EC, 2021[29]).

There also appears to be an implementation gap where farmers are not correctly and completely implementing requirements. Ten per cent of observed infringements of CAP cross compliance requirements have to do with the statutory management requirements stemming from the ND, the third most common infringement overall and the most frequent among those cross compliance requirements related to the environment (ECA, 2016[30]).

The Biodiversity and F2F Strategies set a common objective of reducing nutrient losses in the environment by at least 50% by 2030, while preserving soil fertility. The ND is considered a key piece of legislation to achieve this target and other objectives of the EGD. To reinforce implementation and enforcement to match the objectives of the ND, an Integrated Nutrient Management Action Plan is planned to help co-ordinate efforts and identify the nutrient load reductions needed to achieve the EGD targets on nutrients (EC, 2021[29]).

Water quality results should provide feedback to nitrate action programmes

The ND has become a basic measure under the WFD. Member States may elect to implement their nitrate action programmes in an integrated framework that jointly implements the ND and the WFD. In this case, the additional measures provided for in the WFD contribute to achieving the ND’s objectives (Gault et al., 2015[31]).

River basin management plans and PoMs are designed to achieve WFD objectives, and nitrate action programmes may be included in this process, but this is not always the case. There is no automatic process to adapt NAP measures in response to observed outcomes, only a requirement for Member States to amend actions when they are insufficient. This process is generally not integrated with the WFD and RBMPs. Aligning the nitrate action programmes and RBMPs is challenging – they operate at different spatial scales and on different time frames (NAPs are renewed every four years; RBMPs every six) and are developed by different administrative bodies. Moreover, neither nitrate action programmes nor RBMPs align with the CAP planning cycle.

There are many ways to adjust nitrate action programmes when objectives are not being met. The European Commission may request changes via consultation with Member States or through infringement procedures, domestic courts may rule current approaches insufficient to meet legal obligations, or the responsible administration may institute changes based on observed lack of progress. The European Commission can request additional measures as part of a derogation agreement, such as the cap at 2002 levels on total N and P in the Netherlands (Gault et al., 2015[31]). For most Member States, NAPs have been strengthened over time and the area designated as vulnerable has increased. However, this process has not resulted in a sufficient reduction of water pollution from agricultural sources.

4.2.4. Sustainable Use of Pesticides Directive (2009/128/EC)

The authorisation and marketing of pesticides have been regulated at the EU level since 1991. In 2009, the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Directive (SUD) replaced the EU Thematic Strategy on the sustainable use of pesticides, which started in 2006. The directive’s aim is to achieve a sustainable use of pesticides by reducing the risks and impacts of pesticide use on human health and the environment and promoting the use of integrated pest management (IPM) and alternative approaches or techniques, such as non-chemical alternatives to pesticides.

In principle, the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Directive provides Member States with many tools to reduce the risks of pesticide use

The SUD asks all professional users of pesticides to implement IPM, including the use of non‑chemical alternatives, and to use practices and products with the lowest risk to human health and the environment. It defines IPM and the general principles it should include. The SUD requires Member States to identify trends in the use of certain active substances; identify priorities, such as active substances, crops, regions or practices that require particular attention, or good practices; communicate the results of these evaluations to the Commission and other Member States; and make this information available to the public (Article 15).

Member States are required to produce national action plans setting out how they will achieve the sustainable use of pesticides (NAPs), including quantitative objectives, targets, measures and timetables to reduce the risks and impacts of pesticide use on the environment. This should include indicators to monitor the use of pesticides containing active ingredients of particular concern. The NAP should reflect objectives, targets and measures set in other environmental planning tools, such as RBMPs, national biodiversity strategies or plans, or pollinator strategies. The first NAPs were published between 2012 and 2014, and the second between 2017 and 2021.

The SUD gives authorities the power to minimise or prohibit pesticide use in public spaces, Natura 2000 sites and water protection sites; to minimise or eliminate risks to the health of vulnerable groups; or to reduce pressures on biodiversity in protected areas (Article 12). There is a general ban on aerial spraying of pesticides (including from drones), with a procedure for Member States to grant derogations (Article 9). Article 10 requires specific measures to protect the aquatic environment and drinking water, including a preference for pesticides that do not damage the aquatic environment, buffer zones and safeguard zones, and measures to mitigate drift and flow, such as mandatory use of certain equipment. Member States should reduce the risk to water by decreasing or eliminating applications on or along roads, railway lines, very permeable surfaces, etc.

The SUD requires a system of regular checks of pesticide use equipment and regular training and certification of professional users and pesticide distributors and salespersons. It sets rules for handling, packaging, storing and disposing of pesticides. It requires a system of surveillance of pesticide poisonings of humans and wildlife. Member States shall inform and raise the awareness of the general public with accurate and balanced information relating to pesticides about the risks and the potential acute and chronic effects for human health, biodiversity and the environment arising from their use, and the use of non-chemical alternatives.

But imprecise targets and poor monitoring reduce effectiveness

According to two Commission assessments, there is a lack of precise and measurable targets in the NAPs, along with a lack of ambition and a need to upgrade NAPs regarding biodiversity biodiversity objectives (EC, 2017[32]). These assessments were informed by a series of fact-finding missions, followed by audits to check compliance in 2018 and 2019. Only four NAPs set an overall quantified pesticide risk reduction target,14 and only Denmark and Germany link this to a measure of environmental risk. Despite these measurement problems, some evidence suggests that the SUD has failed to reduce pesticide use and risk and has not led to a common approach in NAPs to systematically treat problems, propose measures, or define timetables for implementation and indicators (Helepciuc and Todor, 2021[33]).

Limited monitoring of the impact of pesticides on the environment and human health makes it difficult to assess the impact of NAPs (Remáč et al., 2018[34]). Member States are required to ensure that professional users keep records of their pesticide use, but there is no legal requirement for the government to collect these records from users. A parliamentary resolution in February 2019 noted that very little progress had been made in promoting and incentivising the innovation, development and uptake of low-risk and non-chemical alternatives to conventional pesticides. Moreover, approximately 80% of Member States’ NAPs do not contain any specific information on how to quantify the achievement of many of the objectives and targets, particularly as regards targets for IPM and aquatic protection measures.15

The European Commission responded to the observed weaknesses in the SUD implementation with a combined evaluation roadmap and inception impact assessment of the SUD. The evaluation that followed included a support study submitted in October 2021 (Ramboll and Arcadia International, 2021[35]), stakeholder consultations during 2020 and 2021, and a public consultation between January and April 2021. In May 2020, the F2F Strategy established an EU-wide objective to reduce the use and risk of pesticides by 50% by 2030. The target was accepted by the European Parliament and Council. In June 2022, the Commission published its proposal for a new Sustainable Use of Pesticides Regulation to replace the SUD.

Measuring and reporting on reductions in the risk and use of pesticides is set to improve

The first EU-wide Harmonised Risk Indicators were published in May 2019, setting a baseline of pesticide use in the period 2011-13, and trends from 2011 to 2019 based on sales data. Member States also produce Harmonised Risk Indicators at the national level. The indicators put greater weight on the use of pesticides that are candidates for substitution and the use of unauthorised pesticides and less weight on the use of low-risk and biopesticides. The risk indicators show a decreasing trend since 2011, but the volume of pesticides used in the European Union is not decreasing (Eurostat, 2022[36]). This reduction in risks has come mainly from banning or withdrawing active substances at the EU level that are then replaced with other pesticides with a lower risk weighting (Chapter 1).

Eurostat publishes annual pesticide sales figures for the major groups, categories of products and chemical classes. The significant differences in the range of products reported by different countries limit comparability and data on individual active substances are unavailable.16 Member States are not required to report these data to Eurostat, and currently, only 16 do. The revised Statistics on Agricultural Input and Output (SAIO) Regulation 2022/2379 places stronger reporting requirements on Member States starting in 2025. It implements farm-based collection of pesticide use statistics across the European Union and requires Member States to collect annual data on pesticide use from 2026 and publish annual reports from 2028 based on “a common list of representative crops” to be determined over a transition period from 2025. It will result in a register held by competent national authorities on the use of plant protection products in agriculture and ensure the availability in electronic format of the records to be kept by professional users of plant protection products. An implementing regulation is being developed that proposes that professional users of pesticides transmit their records in electronic format to competent national authorities.

Harmonised risk values focus on the most dangerous pesticides; large agricultural countries are the biggest users

The indicators are designed to reflect reductions in the use of candidates for substitution (CfS), pesticides whose use is considered most problematic because of their health or environmental hazards. The number of CfS in the EU market has decreased slowly in the six years since the system was introduced (Robin and Marchand, 2021[37]). CfS currently in use in the European Union must periodically have their approval renewed. Twenty-one of the 56 approved CfS were due to have their approval reviewed in 2022 and an additional 15 in 2023.17 If all these active substances were removed from the market, this would have a very noticeable effect on the indicator HR1.

Member States can improve their indicators by decreasing or eliminating the use of pesticides classified as CfS, with herbicides and fungicides having more impact due to their higher weight per application. For example, in France, CfS made up 22% of the weight of sales in 2018 (BASIC, 2021[38]). Governments may ban or severely restrict the use of CfS, make them more expensive than alternatives through differential taxation, or promote alternative methods.

Pesticide use is dominated by the largest agricultural producers: France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Spain, which account for half of the pesticide sales by weight in the European Union. Reductions in pesticide use in these countries would have a large effect overall, while changes in smaller users would be less likely to be reflected in overall values.

Proposed new Regulation on Sustainable Use of Plant Protection Products

The European Commission published a proposal for a Sustainable Use of Plant Protection Products Regulation in June 2022. The proposal was designed to address four problems: 1) alignment with pesticide-related targets in the F2F Strategy; 2) strengthening current SUD provisions; 3) improving data availability and monitoring; and 4) addressing new technologies. The regulation contains many of the provisions of the directive but also sets legally binding reduction targets for Member States, tightens the provision for pesticide-free areas, and more clearly defines what an IPM is and how it can be assessed.

Since the proposal was drafted in 2022, some have called for additional impact assessments of the Sustainable Use of Plant Protection Products Regulation. In December 2022, the European Council requested an additional analysis under Article 241 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.18 The Commission must deliver the requested assessment by June 2023.

Production costs per unit may increase subsequent to the Sustainable Use of Plant Protection Products Regulation due to:

stricter and more detailed reporting requirements

the expected reduction of yields due to lower pesticide use

the inclusion of an additional cost layer for those professional users not currently using advisers.

The Sustainable Use of Plant Protection Products Regulation evaluation support study (Ramboll and Arcadia International, 2021[35]) found a large uncertainty in the predicted economic impacts of the reduction targets. Estimates of yield loss from 2030 pesticide reduction targets range from 7% to 30% for permanent crops to 0-15% in annual field crops, based on expert opinions (Bremmer et al., 2021[39]). The impacts of the pesticide target on crop production depend on the alternatives that will be available to farmers in the future. The potential for innovation in this respect is hard to estimate but could be substantial, as shown by the reductions achieved by leading farms in France while maintaining overall profitability (Lechenet et al., 2017[40]). Member States may provide support under the CAP to cover the costs to farmers of complying with all the legal requirements imposed by the regulation for a period of five years (EC, 2022[41]).

The CAP’s role in achieving Sustainable Use of Pesticides objectives

The 2009 SUD foresaw the possibility of the IPM becoming part of the conditionality rules of the CAP. However, the CAP legislation for the 2014-22 period did not include the SUD in the statutory management requirements for farmers. The European Commission’s report of October 2017 concluded that Member States had not developed clear criteria to assess the implementation of IPM principles in controls at the farm level and have not taken appropriate measures to deal with non-compliance in this regard. The second report reached the same conclusion. The European Court of Auditors (ECA, 2020[42]) concluded that Member States undertake only very limited control of farmers to verify that IPM principles are implemented, and as that IPM implementation is not a condition for receiving CAP payments, there is little development of non-chemical alternatives and little incentive for farmers to take them up. Several Member States request that farmers fill out a form with information on how they have applied for IPM. However, the forms are currently not checked by inspectors to determine compliance with the principles of IPM.

The CAP 2023-27 requires compliance with the SUD as part of conditionality; however, it does not reference the SUD Article 14 requiring farmers to apply IPM.19 There is, therefore, no mandatory requirement in the CAP that specifies that farmers have to make plans to reduce pesticide use and prove that they are applying IPM in order to receive direct payments. If the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Regulation is adopted, this will replace the directive in the CAP regulation.

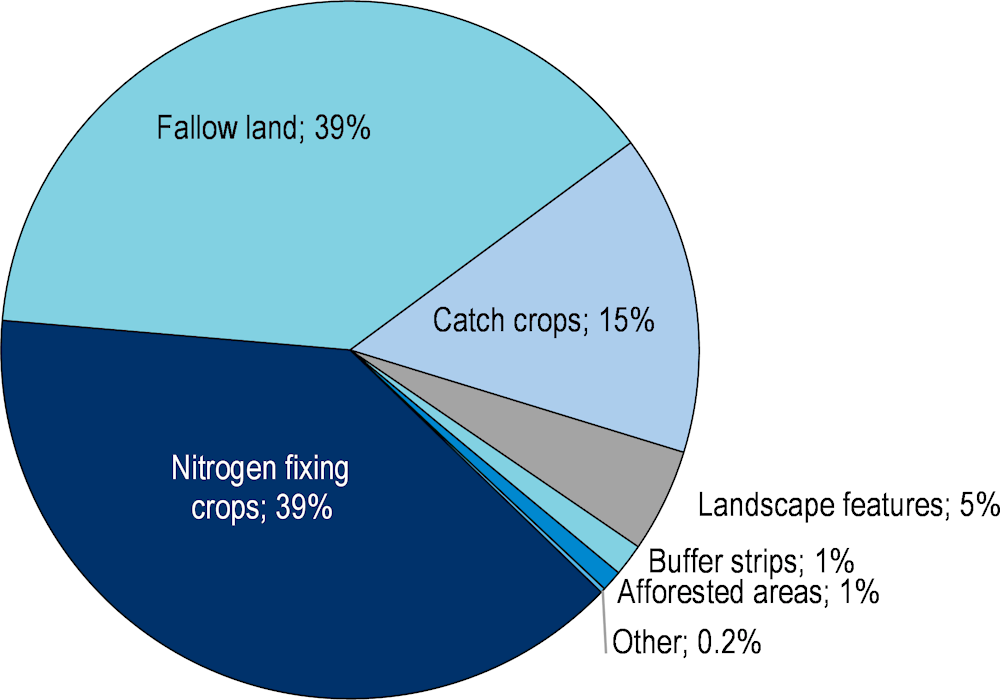

The CAP framework includes the scope for Member States to set a strong mandatory baseline of requirements that make up the basis for IPM in the Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions (GAEC) for crop rotation, buffer strips along water courses, cover crops, and at least 4% of area under landscape features and fallow or nitrogen-fixing crops in which pesticides are not used. Eco-schemes, agri-environmental schemes and investments can then be used to provide incentives for farmers to apply IPM or to carry out practices that support IPM. However, the ambition of the new CSPs appears to be low – target values for the results indicator on the share of utilised agricultural area under-supported specific commitments which lead to sustainable use of pesticides are below 10% in an assessment of nine plans (EEB and Birdlife, 2022[43]).

The CAP is an important source of funding for innovation and learning, which are crucial components of the transition to less use of chemical pesticides, and in particular the European Innovation Partnership for Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability (EIP-AGRI) approach has a good potential to tackle practical problems through a co-creation process involving farmers (Chapter 5, Section 5.6). Almost 450 of the 2 500 EIP-AGRI Operational Groups focus on topics related to the sustainable use of pesticides (EC, 2022[44]). The new CAP plans have considerable scope to support the transition and innovation and increase farmers’ capacities and knowledge to manage crops with lower pesticide use.

4.2.5. The Habitats Directive and the Birds Directive (2009/147/EC)

Known collectively as the Nature Directives, the Birds and Habitats Directives are the two main pieces of EU nature legislation which, for more than 30 years, have helped conserve natural habitats and wild fauna and flora in the European Union. Adopted unanimously by the Council in 1979, the Birds Directive aims to protect all wild bird species and their habitats across the European Union. The Habitats Directive, adopted unanimously by the Council 13 years later (1992), introduces very similar measures but extends protection to more than 1 200 other rare, threatened or endemic species of wild animals and plants, collectively referred to as species of Community interest and, for the first time, protects 231 habitat types in their own right. Both directives are similarly designed and structured, requiring the conservation of species and their habitats through a combination of protection measures, monitoring and research.

The Nature Directives require Member States to establish, protect and manage the Natura 2000 network, protect landscape features of importance for the coherence of the Natura 2000 network, protect species, and carry out supporting measures (e.g. funding, research and public awareness-raising). These actions form a coherent framework that can address the many problems facing habitats and species. The Natura 2000 network of areas of high nature value across the European Union is the most visible element of this framework, but the effect of the directives goes beyond the sites that make up Natura 2000 (Milieu, IEEP and ICF, 2016[45]).

Annex I of the Habitats Directive lists the natural habitat types of Community interest whose conservation requires the designation of special areas of conservation (Natura 2000 sites). There are 63 habitat types whose conservation depends on appropriate agricultural management (Halada et al., 2011[46]). These can occur in three broad types of agricultural land, which differ in the degree to which they support habitats and the species of community interest (EC, 2014[47]).

Semi-natural agricultural habitats (177 442 km2). Habitats Directive Annex I and similar habitats of high nature value are dominated by native species, dependent on extensive agricultural management of the vegetation and associated native species that have not been planted.20 These habitats are the result of centuries of human activities. They include permanent grassland and shrubland pastures that depend on livestock grazing, meadows dependent on mowing or grazing, and some long-established agroforestry habitats. Some areas of extensively managed cropland and fallow (pseudo-steppes) are also important habitats for species of European conservation concern.

Agriculturally improved grasslands and croplands (1.9 million km2). These include grasslands that are managed to increase their productivity through ploughing and reseeding with productive strains of agricultural grasses and the use of drainage and mineral fertilisers. Cultivated improved croplands are also included; these are arable or permanent crops intensively managed with the use of fertilisers, herbicides, pesticides and, in some cases, irrigation. Such intensively used farming landscapes do not host habitats of high nature value or sensitive species but do contain many widespread but declining farmland bird species, small mammals, etc., and may contain remnants of Annex I habitat types in small, fragmented patches.

Agroforestry, which integrates trees or shrubs with crops or livestock, is estimated to cover at least 106 000 km², representing about 6.5% of the utilised agricultural area in Europe (den Herder et al., 2016[48]). The proportion of utilised agricultural land involving agroforestry is reported as varying from about 50% in Greece and Portugal to low values in central and northern Europe. High-value agroforestry includes orchards of full-sized fruit or nut trees and grazed or mown (Annex I) agroforestry is less intensively or traditionally managed and “new” agroforestry establishes trees or shrubs in existing arable fields and has less significance as a habitat for species of European conservation concern.

The implementation of EU Nature Directives is improving; closer integration with the CAP could accelerate progress

Implementing the Nature Directives habitats and species protection “on the ground” is largely the responsibility of Member States. LIFE is the only dedicated EU fund for implementing the Nature Directives, and provides project funding but not long-term support; however, national funds can be combined with other EU funds (Chapter 5). For example, protected agricultural and forest habitats and wild birds and protected species associated with agricultural land can benefit from CAP funding (largely from the EAFRD) for nature conservation management payments for land managers. Member States report to the European Union every six years on progress. These contribute to the State of Nature reports published by the European Environment Agency, which provide the most up-to-date picture of the detailed performance of the Nature Directive.

The general objectives of the Nature Directives to conserve or restore habitats and species are translated into specific and operational objectives that lead to actions to identify and protect special protection areas and areas of conservation. The Natura 2000 network is made up of such areas. Financial, human and institutional resources are dedicated to support protection activities and achieve operational objectives. This includes site and species management, enforcement, research, information sharing, and education (Milieu, IEEP and ICF, 2016[45]).

Member States’ compliance with the Nature Directives is enforced through the Court of Justice of the European Union. There are currently 77 active cases, involving 24 of the EU27 Member States, some dating back to 2014. The number of breaches of the directives reported to the European Commission has decreased over time, indicating that the implementation of the directives has evolved and improved substantially. This improvement comes from a combination of guidance and lessons learnt from experience, enforcement actions and interpretation of the legislation by the Court of Justice of the European Union (Milieu, IEEP and ICF, 2016[45]). Better coherence with other EU policies can help increase effectiveness. Integration with the CAP is of particular interest since agriculture and forestry exert the most influence on terrestrial biodiversity in the European Union.

The outcomes of the Nature Directives are underappreciated, leading to underinvestment and inattention

A comprehensive policy evaluation or “fitness check” in 2016 concluded that the Nature Directives are fit-for-purpose but achieving their objectives and realising their full potential will depend upon substantial improvements in their implementation. Key shortcomings in implementation include limited resources, weak enforcement, poor integration of nature objectives into other policy areas, insufficient knowledge and access to data, as well as poor communication and stakeholder involvement.

The Commission concluded from the fitness check that there has been important progress, such as establishing the terrestrial Natura 2000 network, but not all the necessary conservation measures have been put in place. The efficiency analysis shows a very low cost-to-benefit ratio, which means that investing in Natura 2000 makes good economic sense, but the biodiversity and ecosystem services within and outside the Natura 2000 network are undervalued (EC, 2016[49]).

The proposal for an EU Nature Restoration Law

The proposed Nature Restoration Regulation 2022 (also referred to as the Nature Restoration Law [NRL]) is an ambitious legal instrument to address the deficiencies in the implementation of the Nature Directives and achieve the ambition of the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 to reverse the decline of biodiversity in the European Union and build synergies between climate action and nature restoration. It is the most significant piece of EU biodiversity legislation proposed in the last 20 years and, if fully implemented, could be a substantial step forward in nature protection and a significant factor in meeting the ambitions of the Convention on Biological Diversity as expressed in the recent COP15 agreement.

Unlike the Nature Directives, it is an EU Regulation with quantified targets, indicators and milestones that the 27 Member States will be required to meet. The NRL will require:

Ambitious targets which strengthen and go beyond existing EU legislation – the proposal sets an overarching, legally binding objective for ecosystem restoration as well as ecosystem‑specific targets which strengthen and go beyond current EU nature restoration legislation. These targets are set for 2050, with binding milestones by 2030 and 2040.

Strong communication and understanding of the huge environmental, societal and economic benefits which these restoration targets will deliver, highlighting the many benefits of nature restoration, is key to ensuring the restoration targets are supported and embraced by all stakeholders and society at large. Through its co-benefits, the NRL will help Member States meet other existing and upcoming targets and obligations under the EGD and international commitments.

A strong implementation framework through carefully designed national restoration plans. Member States are expected to submit a first draft of their national restoration plans within two years of the entry into force of the regulation and the plans will run until 2050. A key element of the plans will be to outline the financing needs for implementing the plan and to strengthen links and synergies with other EU environmental objectives, notably climate change action, and their corresponding planning tools. The European Commission will assess these plans to ensure they adequately meet the requirements of the law.

Effective monitoring and reporting. Progress will be monitored and reported by Member States and EU-wide reports will be prepared based on this. The regulation will be reviewed in 2035 to determine whether the law is achieving its objectives.

The CAP’s role in achieving the Nature Restoration Law’s objectives

All farming and forestry systems in the European Union can potentially contribute to the proposed NRL targets, but the potential contribution, benefits and costs to the business differ between farming systems. The main benefits for farmers are resilience to the effects of climate change through improved soil functionality; crop pollination services; reduced impacts of floods, droughts and fire; and improved resistance of crops to pests and diseases.

There are costs to landowners and land managers in helping to achieve the NRL targets; many see this as “pay now, most of the benefits will come later”. Nevertheless, certain measures, such as improvement in soil fertility, can show benefits already after a short period of time. Costs and benefits will vary between farms depending on:

the agricultural intensity of the current management system

the opportunity cost of meeting NRL targets with respect to other land uses (or, in the case of Annex I habitat and high nature value (HNV) farming systems, the cost of avoiding abandonment or intensification)

the current (baseline) state of the habitats, species and agri-ecosystem indicators and, hence, the capital and ongoing maintenance costs of the NRL

the transaction costs of making these changes and securing funding.

Capacity building is also required to give farmers and foresters the confidence, skills and knowledge to respond positively to new environmental challenges. Farm advisors and the agricultural education system also need upskilling to accompany farmers with the support they need. There is also a need for more long-term contractual arrangements and governance to ensure the maintenance of restored areas that need to go beyond the six-year EU Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) funding cycle.

In principle, the flexibilities in the new CAP 2023-27 allow Member States to direct funds to support actions by farmers that aid NRL targets. In addition to the CAP, other sources of EU funding can deliver for agro-ecosystems and forests, including the other EU Regional Development and Cohesion Funds, and financing from supply chain and private funders. Earmarking spending for biodiversity across different EU funds in future MFF cycles could ensure the necessary stability for achieving the long-term investments needed.

4.3. CAP measures to promote environmental sustainability

This section looks at the environmental elements of the CAP, providing an overview of the current situation (as of 2022) and the evolution of policies to this point, together with an overview of the main changes of the new “green architecture” of the CAP 2023-27. It assesses the design and delivery of environmental elements with respect to their outcomes. As described in earlier chapters, the CAP is composed of two pillars. Pillar 1 has traditionally concerned itself with the common market organisation and direct payments to producers. Pillar 2 concerns rural development policy, including ensuring sustainable management of natural resources and climate action. This latter objective is mainly addressed through Agri-Environmental Schemes (AES), although not limited to such schemes. The CAP 2014-22 maintained the existence of two pillars but took a more integrated approach to agri-environmental policy support via the introduction of the green direct payments scheme in Pillar 1 (Greening). The CAP 2023-27 deepens this approach by providing increased funding flexibility between the two pillars, strengthening the cross‑compliance and allocating 25% of the budget for direct payments to eco-schemes.

4.3.1. Cross-compliance

As discussed in Chapter 3, mandatory environmental cross-compliance was first introduced in 2000. It became a requirement in Pillar 1 as part of the Fischler 2003 CAP Reform and from 2005, all farmers receiving direct payments have been subject to compulsory cross‑compliance provisions.21 Cross-compliance aims to ensure that beneficiaries of the CAP implement mandatory basic standards and requirements and it is also designed to raise awareness on the part of beneficiaries regarding their obligations under statutory management requirements (SMRs). Since 2007, cross‑compliance has also applied to area related EAFRD payments, and since 2008 to certain wine payments.

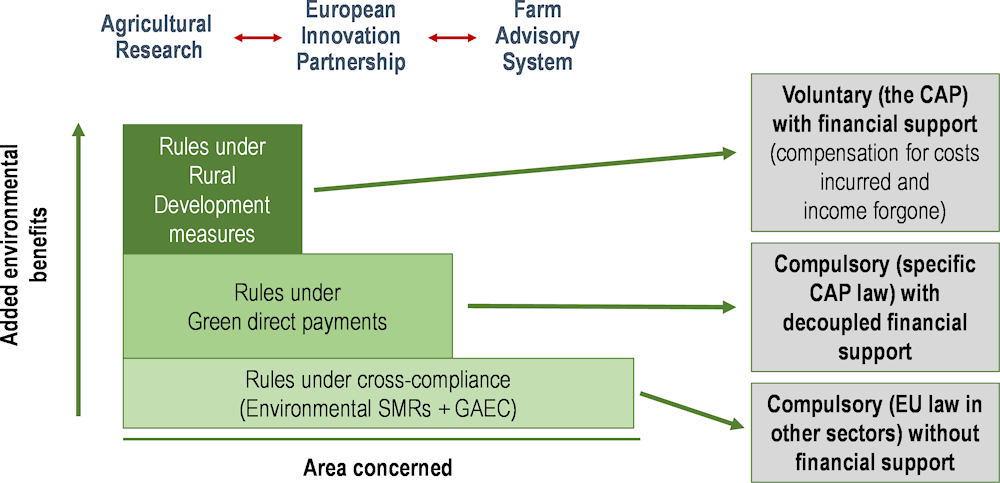

The intervention logic of the CAP with respect to the environment is based on a hierarchy of action and compensation based on distinguishing between minimum obligations and extra effort. Cross‑compliance22 is at the base of this hierarchy, tying direct payments to farmers to compliance with a series of rules relating to the environment, food safety, animal and plant health, and animal welfare and to maintaining agricultural land in GAEC (Figure 4.3).23 These rules are set out (for the CAP 2014‑22) in 13 SMRs and 7 GAEC standards. Non‑compliance with these standards and requirements can lead to a reduction in CAP payments to the farmer.

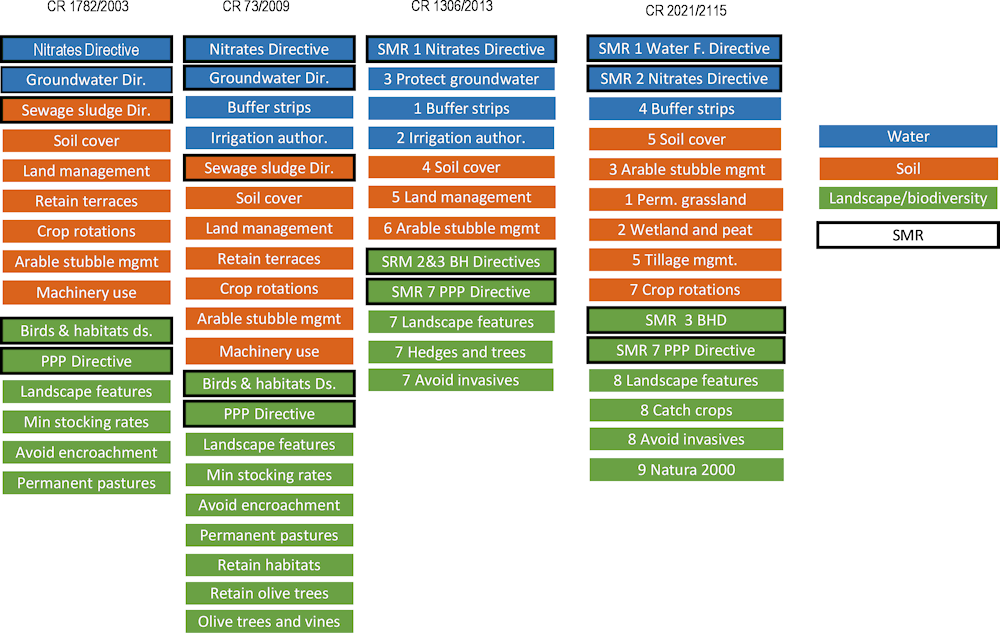

SMRs are defined in the respective EU legislation on the environment, climate change, public, animal and plant health, and animal welfare and are obligatory on farmers regardless of whether they participate in the CAP. In 2019, 151 million hectares (84%) of all EU agricultural land were supported under the direct payment scheme and, therefore, subject to the cross-compliance requirements. Cross‑compliance requirements have undergone revisions in each CAP cycle since their introduction, though these revisions are typically evolutionary in nature (Figure 4.4). SMRs consistently cover water quality, biodiversity and pesticide use. Initial GAEC requirements targeted soil quality and preservation of farmland area. After 2009, they were expanded to include additional conditions related to water and biodiversity, and after 2013 conditions preserving soil carbon stocks were added.

Member States have flexibility in the design of both SMRs and GAECs, so cross-compliance requirements do not result in the same requirements in all countries. For example, for the retention of landscape features (GAEC 7) in the CAP 2014-22, Member States selected mainly from the nine landscape features suggested in the legislation (hedges, ponds, ditches, trees in line, group of trees, isolated trees, field margins, terraces and traditional stonewalls), but could also choose elements that are not on the suggested list, such as protected trees and natural monuments (Table 4.1). Protection is most commonly applied to groups of trees, hedges and isolated trees, trees in a line, and terraces.

Figure 4.3. Environmental instruments of the CAP 2014-22

Note: SMR: statutory management requirements; GAEC: Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions; CAP: Common Agricultural Policy.

Source: EC (2016[50]).

Figure 4.4. Evolution of cross-compliance requirements, 2003 to present

Notes: GAEC: Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions; PPP: plant production products; SMR: statutory management requirements. All Water Framework Directive minimum obligations in terms of measures for agriculture are not covered by SMR 1 under Regulation 2021/2005. It includes Articles 11 (3)(e) and (h) to cover diffuse pollution of phosphates. Certain GAECs, such as buffer strips, are interpreted and implemented differently by Member States. Natura 2000 refers to environmentally sensitive permanent grassland in Natura 2000 areas. Landscape features in CR 2021/2115 include non-productive areas as well as hedges and trees.

Source: Compilation from CAP regulations as noted in the figure.

Table 4.1. Landscape feature types addressed by Member States in GAEC 7 (CAP 2014-22)

|

Hedges |

Isolated trees |

Trees in line |

Trees in group |

Field margins |

Ditches |

Ponds |

Stone walls |

Terraces |

Other1 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Austria |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||

|

Belgium |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||

|

Bulgaria |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

Croatia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||

|

Cyprus |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||

|

Czech Republic |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Denmark |

X |

|||||||||

|

Estonia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

|

Finland |

||||||||||

|

France |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||

|

Germany |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Greece |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

|

Hungary |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||

|

Ireland |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||

|

Italy |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||

|

Latvia2 |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||

|

Lithuania |

X |

|||||||||

|

Luxembourg |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Malta |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||

|

Netherlands |

X |

|||||||||

|

Poland |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||

|

Portugal |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

|

Romania |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||

|

Slovak Republic |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Slovenia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||

|

Spain |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Sweden |

X |

X |

X |

X |

1. In addition to the types predefined in the CAP legislation, it is also possible for the MS to nominate “other” landscape features

for inclusion into GAEC 7.

2. Latvia nominates other landscape features in GAEC 7 including natural monuments such as protected trees and rock outcrops and requires removal of invasive species of the genus Latana on agricultural land. As for hedges some restrictions are applied on dates during which hedges may be cut or trimmed.

Source: Joint Research Centre GAEC database as reported in Czúcz et al. (2022[51]).

Inspection rates and penalties are less than optimal