This chapter briefly describes the main demographic, macro-economic and environmental issues in Moldova of relevance to the transport sector. It presents an overview of the public transport system in the country as well as the level of greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution in its main urban centres. It also analyses the major health risks associated with the main air pollutants. This review forms part of the justification for the need for public support for investments in the transport sector.

Promoting Clean Urban Public Transportation and Green Investment in Moldova

6. Macro-economic and environmental overview

Abstract

6.1. Demographic and macro-economic situation

6.1.1. Geographic location and territorial division

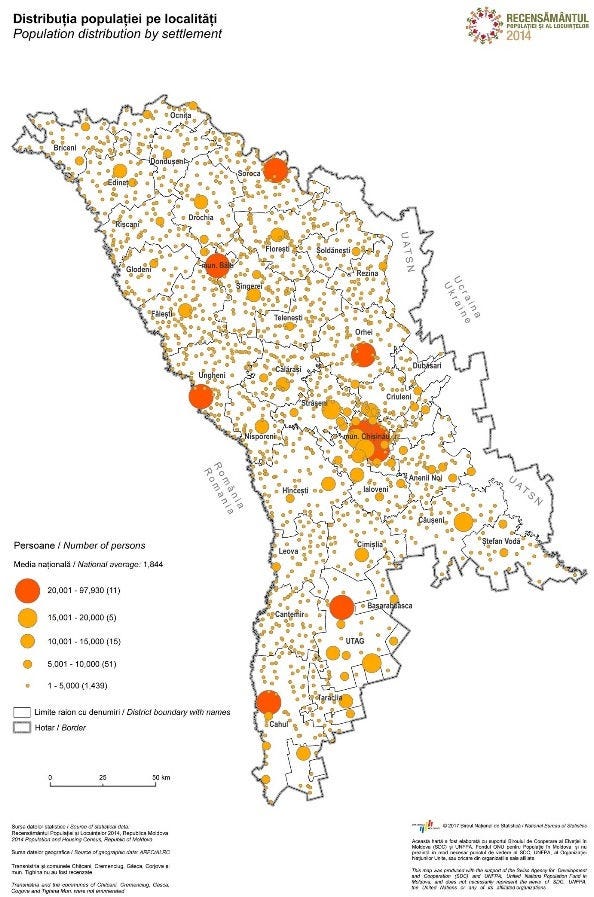

The Republic of Moldova is in south-east Europe, in the north-eastern Balkans, on a territory of 33 843 km2. To the west it shares a border with Romania, and to the north, east and south with Ukraine (Figure 6.1). The total length of the national boundaries is 1 389 km, including 939 km with Ukraine and 450 km with Romania.1 According to the data from National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the population of Moldova as of 1 January 2018 was 3.55 million.2

The Republic of Moldova’s administrative-territorial organisation involves two local government levels: 3 1) LPA 1 (local public administration): villages (communes) and towns/cities (municipalities); and 2) LPA 2: districts (rayons), and two second-tier municipalities (Chisinau and Balti). Currently, Moldova is divided into 32 districts, 13 municipalities and 2 regions with special status: 1) Autonomous Territorial Unit Gagauzia; and 2) administrative-territorial units on the left bank of the Dniester River. Six development regions have been established, aiming to attract funds and investments and to ensure sustainable development.4

Figure 6.1. Population distribution by settlement

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (www.statistica.md).

6.1.2. Demographic and socio-economic development

The process of urbanisation is happening very gradually, and has even been reversing since 1989, as census data show (Table 6.1).5 Urbanisation, especially in smaller cities and towns, slowed down in the 1990s, either as a result of poor competitiveness of the old-style industry under free-market conditions (combined with mismanagement during the transition process) or administrative changes (a significant number of large villages were assigned the status of urban settlement). Also population decline (contrary to 1950-1990 growth) and emigration after 1990 have posed challenges to urbanisation, leading to a decline in the supply of public services, especially in smaller cities and towns (GoM, 2016[1]).

As Table 6.1 shows, the level of urbanisation in 2014 resembled the level in 1970.

Table 6.1. Census results in Moldova, 1970-2014

|

Census |

Urban |

Rural |

Total |

Urban |

Rural |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

mln people |

percentage |

percentage |

|||

|

1970 |

1.13 |

2.44 |

3.57 |

31.7% |

68.3% |

|

1979 |

1.53 |

2.42 |

3.95 |

38.8% |

61.2% |

|

1989 |

2.02 |

2.32 |

4.34 |

46.6% |

53.4% |

|

2004 |

1.31 |

2.08 |

3.38 |

38.6% |

61.4% |

|

2014 |

0.95 |

1.85 |

2.81 |

33.9% |

66.1% |

Note: 2004 and 2014 information do not include data on districts on the left bank of the Dniester River or the Bender Municipality.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (www.statistica.md).

In 2018, out of the total population of 3.55 million people, 51.9% were women, whereas in urban areas the ratio was 53.2%.6 Of the total population, 83.1% of men are of working age (16-61 years), whereas the ratio for women is 59.0% (16-56 years). The ratio of retired people is very similar for urban and rural areas: 19.4% and 18.7%, respectively.7

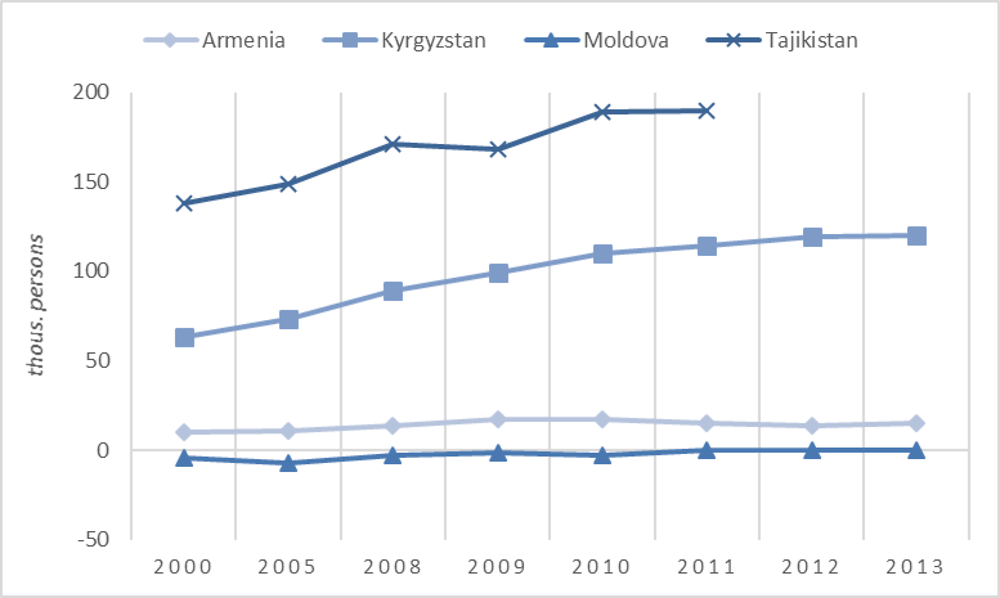

Moldova is one of the Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia (EECCA) countries whose population is declining (Figure 6.2). Compared with 1991 figures, in 2018 Moldova had 441 000 fewer females and 376 000 fewer males.8

Figure 6.2. Natural population increase in selected EECCA countries, 2000-13

Note: 2012 and 2013 data for Tajikistan not available.

Source: (CIS, 2014[2]), Commonwealth of Independent States in 2013 – Statistical Yearbook.

According to a 2013 household survey (based on a sample of 20 850 households), 12.4% of household members were abroad more than 12 months in previous year, 68.4% of whom came from rural areas (Nexus, 2013[3]). In total, 271 600 people were living abroad for a longer period (one year or more), whereas the foreign population living in Moldova reached only 21 700 people (at the end of 2014). In 2014, 26.4% of rural households and 20.6% urban households benefitted from remittances. In relative terms, rural households benefitted more from remittances as they accounted for 61.6% of their total disposable income, compared with 50.2% for urban households (IOM, 2017[4]).

Average disposable household income in 2017 stood at MDL 2 245 (USD 121) per capita per month. This figure is composed of MDL 2 671 (USD 144) per capita in urban areas and MDL 1 917 (USD 104) per capita in rural areas. In urban areas 55% of this income comes from employment, 22% from social payments, and 11% from remittances from abroad. In rural areas, employment accounted for just 30%, self-employment in agriculture 15%, social protection payments 25%, and remittances 22%. For the country as a whole, 43% comes from employment, 23% from social protection payments, and 16.5% from remittances.9

In 2016, employment was mainly in agriculture (33.7%); public administration, health care, education and social services (18.3%); trade (16.4%); and industry (12.1%). In urban areas, employment is chiefly in trade (26.8%); public administration, health care, education and social services (20.9%); and industry (17.3%). In rural areas on the other hand, employment in agriculture dominates (58.2%) followed by public administration, health care, education and social services (16.1%). In no other sector does employment in rural areas exceed 8%.10

In 2016, the annual unemployment rate was 4.2%. Men experienced a higher unemployment rate overall (5.5%), including an 8% rate in urban areas and 3.2% in rural areas. Women, in contrast, experienced unemployment rates of 2.9% overall, with 4% in urban areas and 1.9% in rural areas.11

6.1.3. GDP and energy intensity

Globally, the link between growing GDP and transport has been a major reason for increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions due to the greater movement of goods and people. The per capita emissions from transport correlate strongly with annual income (Sims and Schaeffer, 2014[5]).

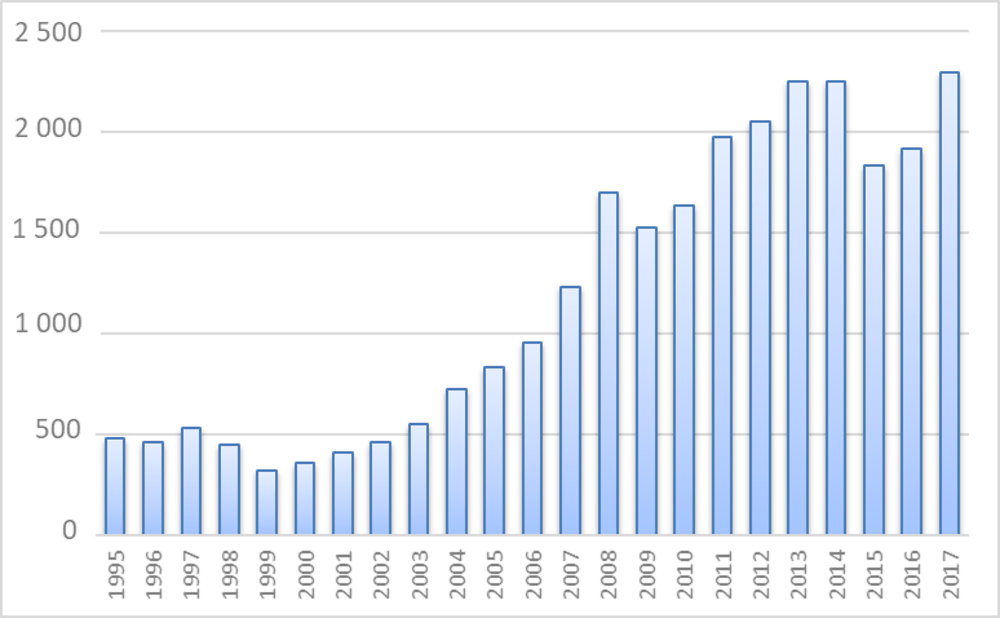

The country’s estimated GDP in 2016 was USD 18.9 billion, measured according to purchasing power parity, and has been growing at an average annual rate of 5.3% since 2002. As shown in Figure 6.3, Moldova’s GDP per capita has multiplied by more than four in the period 2003-13 (according to purchasing power parity, it had almost doubled from 2 393 to 4 700 in current international USD12).

Figure 6.3. Moldova’s GDP per capita, 1995-2017

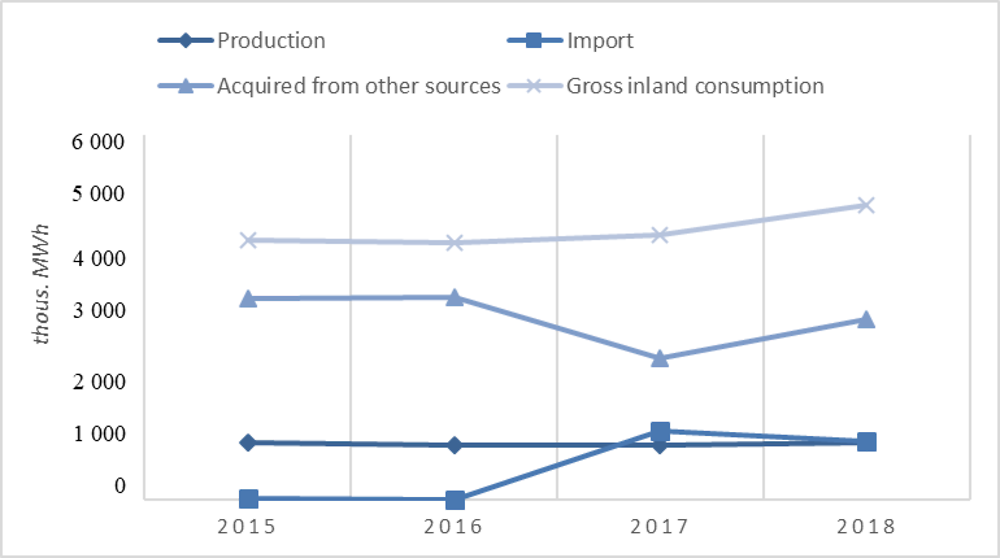

GDP is mostly generated by trade (15.2%), followed by mining and manufacturing (12.0%), agriculture (11.6%) and the public sector (11.6%) (NBS, 2018[6]). The country does not have any coal or natural gas production and is dependent on imports. Moldova produced 5 000 tonnes of petroleum products in 2017, which was sufficient to cover just 0.5% of its gross domestic consumption of these products (NBS, 2018[6]).

Despite the fact that Moldova contributes relatively little to climate change – while the country accounted for 0.05% of the world’s population in 2012, it was responsible for 0.02% of the global GHG emissions13 – its economy is both highly energy and carbon-intensive. Moldova’s energy use is much higher than the averages for the European Union (EU), OECD, and the world. In 2014, Moldova’s energy use stood at about 195 kilogramme of oil equivalent (koe) per 1 000 USD of purchasing power parity (PPP) GDP, using 2011 prices, compared with about 88 for the EU, 110 for the OECD countries and 126 for the world as a whole.14

While in absolute terms Moldova’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions have significantly declined over the years, the carbon intensity of the Moldovan economy (or “CO2 emissions per GDP”) is still very high (0.276 kg CO2 per PPP GDP 2014 USD) compared to the EU (0.17 kg) and OECD countries (0.239 kg).15

6.1.4. The financial sector

Moldova’s financial sector is dominated by banks. The banking sector comprises the National Bank of Moldova (Banca Naţională a Moldovei – BNM) and 11 commercial banks (BC Moldova Agroindbank S.A., BC Comertbank S.A., BC EuroCreditBank S.A., BC Energbank S.A., BC Eximbank S.A., FinComBank S.A., BC Mobiasbanca - Groupe Société Générale S.A., BC Moldindconbank S.A., BC ProCredit Bank S.A., BCR Chisinau S.A., BC Victoriabank S.A.).

The BNM licenses, supervises and regulates the activity of financial institutions operating in Moldova. The shareholders of Moldova’s banking sector are mostly from abroad, as foreign investors own 86.1% of the banks’ share capital.16 Four Moldovan banks have full foreign capital (i.e. they are branches of foreign banks or foreign financial groups).

Currently, banks in Moldova do not play a significant role in the country's economic development and business activity. Moldova’s high sovereign credit risk combined with high inflation rates (up until 2016) have led to high interest rates and limited availability of affordable and long-term bank loans. The lack of funds with longer tenors is a particularly persistent problem in the country’s banking system.

One of the factors contributing to this situation was the off-the-scale bank fraud unveiled in November 2014, when it came to light that more than USD 1 billion – equivalent to 15% of the country’ annual GDP or half of the reserves of the BNM – had disappeared from three of Moldova’s leading banks (Banca de Economii,17 Unibank and Banca Sociala).18 The resultant bailout of these (suddenly bankrupt) financial institutions cost national authorities almost half Moldova’s annual budget and prompted an overdue clean-up of the banking sector.

This led to a currency “collapse” (from a European perspective) and put the national economy into its third annual GDP decline within a period of only six years (after 2009 and 2012). However, this third “collapse” turned out to be not as steep as the first one.19 Between November 2014 and November 2015, the Moldovan currency lost about 18% of its value against the Euro,20 also due to a run on Moldovan leu caused by the “missing” billion. This resulted in a general rise in prices (e.g. household electricity, which increased by 30%21), whereas salaries and pensions remained frozen. The World Bank, the International Monetary Fund of the European Union suspended financial aid to the country.

Since then, trust in the country’s banking sector has, to a large extent, been restored, though corruption still remains an issue. In October 2016, the BNM took measures to increase ownership transparency: its newly established Shareholder Transparency Unit (STU) took supervisory action in line with the new Bank Recovery and Resolution Law (No. 232 of 3 October 2016) and blocked and finally cancelled 43% of shares at Moldova Agroindbank – the largest bank in Moldova, holding almost a third of all the country’s retail deposits, and one of its oldest banks22 – and almost 64% at Moldindconbank – the second largest bank.23

The major reason behind this move was the need to improve transparency in the banking sector, rather than to improve solvency. The Law on Financial Institutions (No. 550 of 21 July 1995) now requires that shares in the banks should not be purchased without prior written consent of the BNM (IMF, 2016[7]); (NBM, 2016[8]). In October 2018, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and two private equity firms bought a 41% stake (EUR 23 million) in Agroindbank (Foy, 2018[9]). Since April 2018, the BNM has been trying to sell the majority stake in Moldindconbank (Banila, 2019[10]).

In November 2016, Banca Transilvania S.A. (the second largest bank by total assets in Romania) together with the EBRD (a leading investor in Moldova and previously a major lender to the country’s banking system) announced its intention to acquire 39.2% of shares in Victoriabank (Moldova’s third largest lender). The deal was closed in January 2018 – with EBRD’s minority share of 27.5%. The two foreign banks now hold a controlling stake of 66.7% and have demonstrated that the fraud-hit banking sector in Moldova has stabilised (previous foreign bank acquisitions took place in 200724). Victoriabank’s shareholders also plan to diversify their financial products and to offer, among others, SMEs longer-term lending options.25 Banca Transilvania (in which EBRD also owns 8.6% of shares) sees opportunities in the country’s SME, micro and retail sectors and is expected to bring necessary experience gained on the Romanian lending market (Fitzgeorge-Parker, 2017[11]).

The concentration of the banking sector is quite high in Moldova – the five largest banks account for 79% of capital and 84% of all assets. However, this concentration is not a major obstacle. Besides the above-mentioned transparency issues, the total assets of the banking sector in Moldova make up less than 40% of the country’s GDP.26 Also gross domestic savings have been in negative figures since 2000, having an average annual value of -10.1% of GDP until 2016.27

The loan-to-deposit ratio has decreased from 80% (September 2015) to the current 58% (March 2019), showing that banks have become more prudent in their lending operations after the banking crisis, and are keeping a larger portion of deposits in reserve.28 These requirements constrain bank lending, and the role of the banking sector in Moldova as a contributor to the growth of the national economy remains limited. Because banks do not function properly as financial intermediaries, access to credit for SMEs and private entrepreneurs is complicated. Conversely, banks face challenges in diversifying their clients, as well as channelling their large deposit base into healthy credits (Wrobel, 2019[12]). These challenges are amplified, among others, by the lack of good bankable projects and other (structural) issues, such as loan recovery.

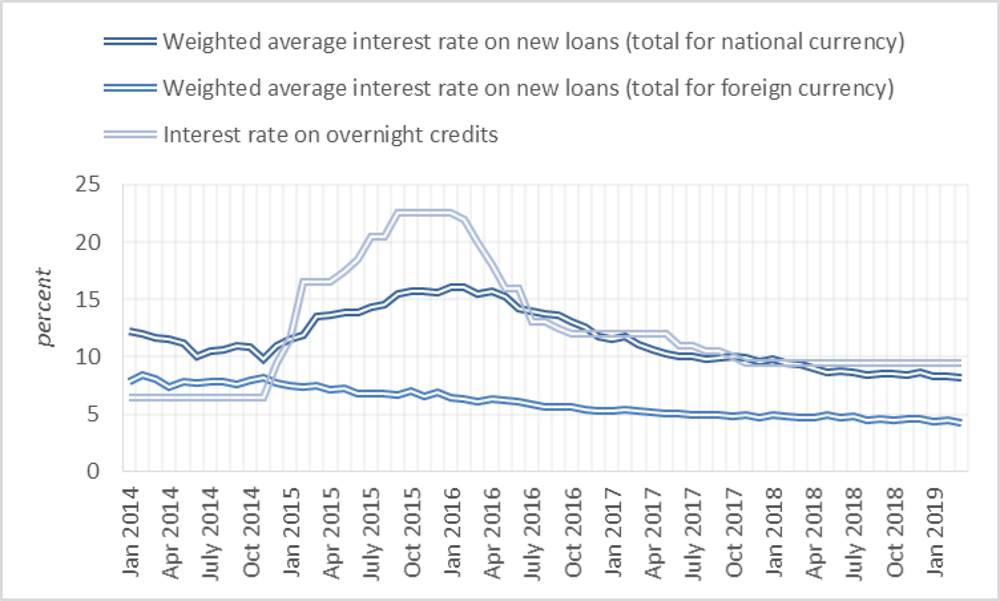

On a positive note, the share of non-performing loans in the total loan portfolio decreased from 18.4% to 12.5% between 2017 and 2018 (ends of year).29 The average inflation rate stabilised in 2016 at 6.5% (from 9.7% in 2015) and was as low as 3.1% in 2018.30 This fall in inflation allowed for the base interest rate set by the BNM to be lowered to 6.5% from the end of 2017 from 19.5% in September 2015.31 The current single-digit interest rates might contribute to higher lending and an overall lending recovery.

In 2018, the average interest rate on long-term (over five years) credit for businesses equalled 9.76% p.a. (in national currency) and 4.60% p.a. (in foreign currency; see Figure 6.4). In terms of credit volumes, long-term loans totalled MDL 598.13 million out of the total of MDL 10 763.4 million granted to businesses (in national currency) and MDL 1 293.82 million out of the total MDL 10 015.14 (in foreign currency). This higher demand by the business sector for long-term credit denominated in foreign currency is largely due to the fact that foreign currency loans come with longer maturities.

Figure 6.4. Interest rates on new loans and overnight credits, 2014-19*

Total loan volumes in 2018 were MDL 18 544.69 million (in national currency) and MDL 10 260.99 million (in foreign currency). Loans to businesses made up 58% of all loans in national currency and 98% of all loans in foreign currency. Thus, long-term loans in foreign currency can be considered more interesting for financing the CPT Programme.32 However, potential currency risk33 means that the government or a donor may want to set up a facility to hedge this risk for companies that choose to borrow in foreign currency. The required reserves ratio on liabilities in national currency was increased to 42.5% and the reserve ratio of the attracted funds in foreign currency was maintained at 14%.34

In November 2018, Moody’s investors service affirmed the Government of Moldova’s B3 rating (stable outlook) taking into consideration the country’s progress in financial stability on the one hand and persisting weaknesses and unpredictability of the domestic political environment (which also entail fiscal risks) on the other. However, Moldova's debt burden is relatively low (also due to small budget deficits35), with a government debt-to-GDP ratio of 31.5% at the end of 2017 (i.e. well below the B-rated median of 56% of GDP). Besides high debt affordability, the large share of foreign currency-denominated debt is currently balanced by the significantly appreciated Moldovan leu in 2017 on the back of stronger remittances and capital inflows.36

6.2. Road and transport infrastructure in Moldova

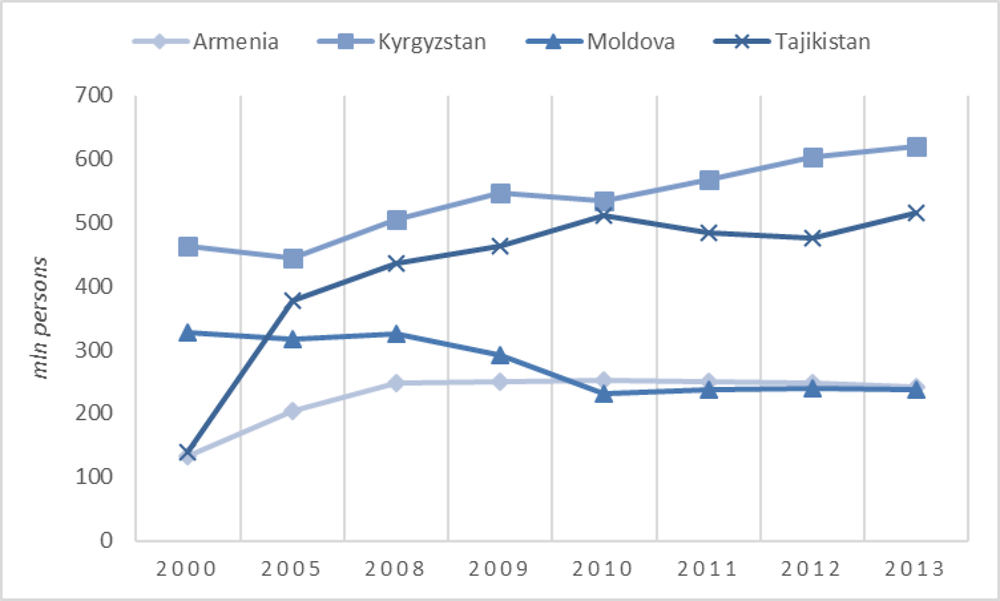

Moldova ranks low among the EECCA countries for the number of passengers using public transport (both in total volume as well as percentage share of population). Moldova ranked second after the Russian Federation for its decrease in numbers of passengers transported (27.5% and 56.3% respectively) over 2000-2013 period (CIS, 2014 [2]).37

Moldova was the only country of its peers to see levels of passenger transport decline (Figure 6.5), which fell to the same level as Armenia in 2013 (both countries are comparable in terms of population size). The latest development (2014-2016), however, shows an increasing trend (Table 6.11).

Figure 6.5. Passenger transportation by transport enterprises in selected EECCA countries, 2000-13

Source: CIS (2014) [2].

The amount of transported goods, on the other hand, rose in Moldova from 28.9 million tonnes in 2000 to 36.9 million tonnes in 2016.

In January 2017, the total length of public roads in the Republic of Moldova was 9 352 km,38 comprising 3 336 km of national roads and 6 016 km of local roads (Table 6.2). The resulting road density is high for a country of the size and population of Moldova. The State Road Administration – a state enterprise within the former Ministry of Transport and Roads Infrastructure (which is now part of the Ministry of Economy and Infrastructure)39 – manages the national roads, and controls much of the financing of local road maintenance.

Table 6.2. Length of public roads, 2010-16

(end of year, km)

|

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public roads - total |

9 344 |

9 352 |

9 352 |

9 352 |

9 360 |

9 373 |

9 386 |

|

of which, hard surface |

8 811 |

8 827 |

8 835 |

8 836 |

8 861 |

8 879 |

8 894 |

|

National roads - total |

3 336 |

3 336 |

3 336 |

3 336 |

3 339 |

3 339 |

3 346 |

|

of which, hard surface |

3 336 |

3 336 |

3 336 |

3 336 |

3 339 |

3 339 |

3 346 |

|

Local roads - total |

6 008 |

6 016 |

6 016 |

6 016 |

6 021 |

6 034 |

6 040 |

|

of which, hard surface |

5 475 |

5 491 |

5 499 |

5 500 |

5 522 |

5 539 |

5 547 |

Note: Data from July 2017.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (www.statistica.md).

Table 6.2 shows that the public road density over the reference period has not undergone any major change. The structure of the public road network as of 1 January 2017 is presented in Table 6.3.

Table 6.3. Structure of public road network

|

Surface |

Total public roads |

National |

Local |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total |

Including |

|||||

|

Highways |

Republican |

|||||

|

Total length, km |

9 386 |

3 346 |

820 |

2 526 |

6 040 |

|

|

of which: |

||||||

|

Upgraded surface (modernised surface) |

km |

5 476 |

2 983 |

799 |

2 184 |

2 493 |

|

% |

58.3 |

89.1 |

97.4 |

86.5 |

41.3 |

|

|

Light bituminous surface |

km |

459 |

117 |

18 |

99 |

342 |

|

% |

4.9 |

3.5 |

2.2 |

3.9 |

5.7 |

|

|

Cobbled roads |

km |

2 959 |

246 |

3 |

243 |

2 713 |

|

% |

31.5 |

7.4 |

0.4 |

9.6 |

44.9 |

|

|

Dirt roads |

km |

492 |

- |

- |

- |

492 |

|

% |

5.3 |

- |

- |

- |

8.1 |

|

Note: July 2017.

Source: State Road Administration (www.asd.md).

According to the Tourism Agency of Moldova, there are 20 tourist routes registered in the country. At present, agrotourism is developing, involving the organisation of festivals and fairs, as well as wine routes. The agency’s estimates show that over 25% of Moldovan residents travel around the country in their own cars. The liberalised visa regime with the EU and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) has also boosted foreign tourism.40

6.2.1. Moldova’s vehicle fleet

This analysis provides a brief review of the current situation of Moldova’s existing bus stock (in terms of ownership status, vehicle age, emission norms, fuel type, etc.).

According to the State Information Resource Centre, “Registru” (Întreprinderea de Stat Centrul Resurselor Informaționale de Stat „Registru” – ÎS CRIS „Registru”), on 1 July 2017, 924 122 means of transport were registered in the country, including 281 349 transport units in Chisinau and 43 739 transport units in Balti (Table 6.4).41

Table 6.4. Structure of vehicle fleet (by type of transport)

|

No. |

Type of transport unit |

No. of transport units |

Share of total, % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Cars |

573 265 |

62.00 |

|

2 |

Trucks |

179 554 |

19.42 |

|

3 |

Trailers |

51 681 |

5.60 |

|

4 |

Tractors |

40 638 |

4.40 |

|

5 |

Motorcycles |

38 623 |

4.20 |

|

6 |

Buses |

20 910 |

2.26 |

|

7 |

Semi-trailers |

16 493 |

1.80 |

|

8 |

Others |

2 958 |

0.32 |

|

Total |

924 122 |

100 |

|

Note: July 2017.

Source: State Information Resource Centre “Registru” (www.registru.md), now located under the Public Services Agency (www.asp.gov.md/en/date-statistice).

While other official statistics present slightly different data (Table 6.5), the overall figures for buses and minibuses correspond. These are the main means of transport of concern for the proposed CPT Programme. The number of cars increased by 169 000 from 2010 to 2017; the number of buses decreased by 485 and the number of trolleybuses increased by 71 over the same period.

Table 6.5. Motor vehicles registered in Moldova, 2010-17

(end of year, units)

|

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2017* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Freight transport vehicles |

131 243 |

141 696 |

151 830 |

154 163 |

160 199 |

164 533 |

179 554 |

|

Buses and minibuses |

21 395 |

21 349 |

21 433 |

21 344 |

21 359 |

21 134 |

20 910 |

|

Cars (including taxis) |

404 290 |

426 973 |

456 379 |

487 418 |

512 561 |

529 813 |

573 265 |

|

Trailers and semi-trailers |

54 127 |

56 482 |

58 827 |

60 797 |

63 076 |

64 953 |

68 174 |

|

Passenger trolleybuses |

343 |

443 |

357 |

380 |

396 |

391 |

414 |

|

Total |

611 398 |

646 943 |

688 826 |

724 102 |

757 591 |

780 824 |

842 317 |

Note: *July 2017.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (www.statistica.md) and State Information Resource Centre “Registru” (www.registru.md); now located under the Public Services Agency (www.asp.gov.md/en/date-statistice).

Table 6.6 categorises vehicles by type of diesel engine using the European emission norms (see Annex B to this report for information on Euro norms).

Table 6.6. Analysis of transport units registered in Moldova (by year of manufacture)

|

No. |

Type of transport unit |

Before 1992 (non-Euro) |

1993-1996 (Euro 1/I) |

1997-2000 (Euro 2/II) |

2001-2005 (Euro 3/III) |

2006-2009 (Euro 4/IV) |

2010-2014 (Euro 5/V) |

After 2014 (Euro 6/VI) |

TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Cars |

206 208 |

69 629 |

31 990 |

101 193 |

93 003 |

32 513 |

4 508 |

539 044 |

|

2 |

Trucks |

63 400 |

17 594 |

37 701 |

42 725 |

11 756 |

2 417 |

294 |

175 887 |

|

3 |

Tractors |

24 629 |

1 628 |

1 822 |

4 022 |

2 069 |

4 069 |

654 |

38 893 |

|

4 |

Motorcycles |

19 023 |

1 166 |

1 288 |

2 582 |

6 178 |

6 787 |

329 |

37 353 |

|

5 |

Buses |

11 790 |

2 438 |

2 649 |

2 511 |

1 167 |

418 |

21 |

20 994 |

|

6 |

Others |

1 717 |

257 |

284 |

327 |

270 |

255 |

38 |

3 148 |

|

Total |

326 767 |

92 712 |

75 734 |

153 360 |

114 443 |

46 459 |

5 844 |

815 319 |

|

|

% |

40.1 |

11.4 |

9.3 |

18.8 |

14.0 |

5.7 |

0.7 |

Note: July 2017.

Source: State Information Resource Centre “Registru” (www.registru.md), now located under the Public Services Agency (www.asp.gov.md/en/date-statistice).

The data presented in Table 6.6 can be summarised as follows:

11 790 buses (56% of the bus fleet) do not correspond to any Euro standard. According to Art. 153 par. (9) of the Road Transport Code, these units should be renewed or replaced by 2020.

In total, 326 767 vehicles do not meet any Euro norms (40.1% of the vehicle fleet).

321 806 vehicles comply with Euro 1/I to Euro 3/III (39.5% of the vehicle fleet).

114 443 vehicles comply with Euro 4/IV (14% of the vehicle fleet).

52 303 vehicles meet Euro 5/V and 6/VI (6.4% of the vehicle fleet).

As of May 2017, 840 companies involved in road freight transport were registered in Moldova, according to information provided by the National Agency of Road Transport (Agenția Națională Transport Auto – ANTA). Nearly three-quarters of the registered trucks are between 11 and 20 years old. In total, 2 638 units are up to 10 years old (45.7% of the fleet), while 1 237 units are over 16 years old (21.4% of the total fleet). Thus, much of the fleet will require replacement in the near future.

Table 6.7. Truck fleet (by age)

|

No. |

Age |

No. of units |

Share, % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Up to 1 year |

4 |

0.07 |

|

2 |

From 1 to 5 years |

275 |

4.8 |

|

3 |

From 6 to 10 years |

2 359 |

40.8 |

|

4 |

From 11 to 15 years |

1 902 |

32.9 |

|

5 |

From 16 to 20 years |

880 |

15.2 |

|

6 |

From 21 to 25 years |

210 |

3.6 |

|

7 |

From 26 to 30 years |

114 |

2.0 |

|

8 |

Over 31 years |

33 |

0.6 |

|

Total |

5 777 |

100 |

Note: May 2017

Source: National Agency of Road Transport (http://anta.gov.md).

On the other hand, nearly half of the trucks comply with Euro V norms, as this is required for international transport activity (Table 6.8). Just over 6% of the truck fleet (359 trucks) only comply with Euro 0 norms and these must be renewed or replaced by 2020, according to the provisions of Art. 153, par. (9) of the Road Transport Code.

Table 6.8. Compliance of Moldova’s truck fleet with Euro norms

|

No. |

Age |

No. of transport units |

Share, % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Euro 0 |

359 |

6.21 |

|

2 |

Euro I |

5 |

0.09 |

|

3 |

Euro II |

614 |

10.63 |

|

4 |

Euro III |

1 626 |

28.15 |

|

5 |

Euro IV |

271 |

4.69 |

|

6 |

Euro V |

2 809 |

48.62 |

|

7 |

Euro VI |

93 |

1.61 |

|

Total |

5 777 |

100 |

Note: May 2017

Source: National Agency of Road Transport (http://anta.gov.md).

The ANTA keeps track of the regular route network according to approved transport programmes. At present, the Moldovan route network includes 480 operators serving 11 130 regular routes, including 6 890 district (rayon) routes, 3 368 inter-district routes and 872 international routes. Regular routes are served through railway stations and bus stations.42 The State Enterprise “Railway and Bus Stations” – which operates under the Public Property Agency (PPA) of the Ministry of Economy and Infrastructure – provides bus services in Moldova and includes 28 branches and 9 private bus stations.43 According to the data submitted by ANTA, 540 transport operators are registered in the State Register of transport operators to provide services for road passenger transport through regular, special regular and occasional services, including 6 179 owned or leased buses.

The data in Table 6.9 show that 98.6% of the public transport vehicles on inter-city routes were manufactured in 2010 and before, including 50% with a high degree of wear (exceeding the average useful life of 7 years for minibuses, 12 years for buses and 15-20 years for trolleybuses, depending on mileage and service). The high wear rate of the bus fleet increases environmental pollution and maintenance costs and reduces road safety. The renewal of the bus vehicle fleet is a vital issue for Moldovan transport operators.

Table 6.9. Inter-city bus fleet (by year of manufacture)

|

No. |

Year of manufacture |

No. of transport units |

Share, % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Up to 1995 |

1 321 |

21.4 |

|

2 |

1996-2000 |

1 558 |

25.2 |

|

3 |

2001-2010 |

3 210 |

52 |

|

4 |

2011-2017 |

89 |

1.4 |

|

Total |

6 179 |

100 |

Note: July 2017.

Source: National Agency of Road Transport (http://anta.gov.md).

From Table 6.10, it can be seen that 38.5% of the inter-city bus fleet has a capacity of up to 20 seats, 48% has a capacity of 21 to 40 seats and only 13.5% has a capacity of 41 seats or more.

Table 6.10. Inter-city bus fleet (by transport capacity)

|

No. |

Number of seats |

No. of transport units |

Share, % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Up to 9 |

45 |

0.7 |

|

2 |

9-20 |

2 333 |

37.8 |

|

3 |

21-40 |

2 964 |

48 |

|

4 |

Over 40 |

837 |

13.5 |

|

Total |

6 179 |

100 |

Note: July 2017.

Source: National Agency of Road Transport (http://anta.gov.md).

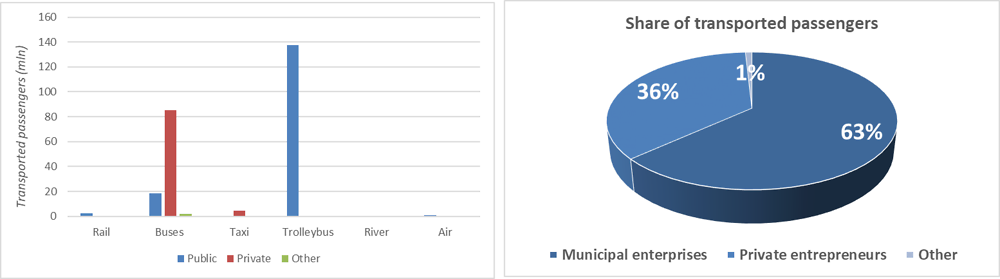

Table 6.11 shows that the number of passengers transported by public transport in Moldova increased by about 4% from 2014 to 2016. Buses and trolleybuses account for nearly 97% of public transport in 2016 (with 105 988 passengers travelling by bus and 137 708 by trolleybus). That said, the number of bus passengers decreased by 6%, whilst trolleybus passengers increased by 14% in the period 2014-2016. This is due to the modification of the public transport networks in Chisinau and Balti, where the number of bus routes has been reduced in favour of the trolleybus network.44

Table 6.11. Passenger transport (by means of transport and ownership form), 2014-16

|

|

Total |

Of which: |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public |

Private |

Other forms |

||||||||||

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|

|

Transported passengers (no.) |

241 485 |

249 540 |

251 970 |

145 692 |

160 482 |

159 447 |

92 345 |

86 624 |

90 342 |

3 448 |

2 434 |

2 182 |

|

Of which: |

||||||||||||

|

Rail |

3 838 |

3 268 |

2 258 |

3 838 |

3 268 |

2 258 |

- |

- |

- |

– |

– |

|

|

Buses |

112 608 |

103 454 |

105 988 |

19 885 |

19 367 |

18 389 |

89 276 |

81 654 |

85 417 |

3 448 |

2 434 |

2 182 |

|

Taxi |

3 048 |

4 951 |

4 749 |

- |

- |

- |

3 048 |

4 951 |

4 749 |

– |

– |

|

|

Trolleybus |

120 951 |

136 642 |

137 708 |

120 951 |

136 642 |

137 708 |

- |

- |

- |

– |

– |

|

|

River |

142 |

139 |

139 |

142 |

139 |

139 |

- |

- |

- |

– |

– |

|

|

Air |

898 |

1 085 |

1 129 |

877 |

1 066 |

953 |

21 |

19 |

176 |

– |

– |

|

|

Passenger journeys – million passenger-km |

4 785 |

5 160 |

5 397 |

2 003 |

2 285 |

2 106 |

2 675 |

2 802 |

3 219 |

107 |

73 |

72 |

|

Of which: |

||||||||||||

|

Rail |

257 |

181 |

122 |

257 |

181 |

122 |

- |

- |

- |

– |

– |

|

|

Buses |

2 874 |

2 922 |

3 106 |

195 |

184 |

177 |

2 573 |

2 665 |

2 858 |

107 |

73 |

72 |

|

Taxi |

63 |

101 |

102 |

- |

- |

- |

63 |

101 |

102 |

– |

– |

|

|

Trolleybus |

367 |

413 |

416 |

367 |

413 |

416 |

- |

- |

- |

– |

– |

|

|

River |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

– |

– |

|

|

Air |

1 225 |

1 543 |

1 651 |

1 185 |

1 506 |

1 392 |

40 |

36 |

259 |

– |

– |

|

Note: Data from July 2017.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (www.statistica.md).

In 2016, three municipal enterprises that operate in Moldova (two in Chisinau and one in Balti) accounted for 63% of transported passengers (Figure 6.6). In terms of passenger kilometres, the situation is the opposite – private transport operators provided 60% of total passenger journeys by length. This high share is influenced by the fact that trolleybus transport is solely publicly operated (both in Chisinau and Balti), whereas inter-city transport is provided only by private companies.

Figure 6.6. Public transport operators, passengers and journey share, 2016

Note: Data from July 2017.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (www.statistica.md).

6.2.2. City of Chisinau’s public transport fleet and network

Public transport fleet

At present, in Chisinau municipality, passenger transport services are provided by the municipal enterprises Chisinau Electric Transport Company (Regia Transport Electric Chișinău – RTEC) and Urban Bus Park (Parcul Urban de Autobuze – PUA),45 as well as by 15 private operators (administrators of light class buses, also known as minibuses). Taxi services are carried out through 35 economic agents which hold the licences. General information on the city’s urban transport set up is presented in Table 6.12.

Table 6.12. Overview of urban public transport fleet, Chisinau

|

Indicator |

Trolleybus |

Bus |

Light class bus |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Total network length, km |

534 |

875.7 |

1 808.1 |

|

2 |

Routes, no. |

23 |

24 |

55 |

|

3 |

Vehicle inventory, no. |

366 |

160 |

1 290 |

|

4 |

Daily entering into traffic, no. |

298 |

125 |

1 180 |

|

5 |

Average operating speed, km/h |

17.1 |

19.4 |

25.6 |

|

6 |

Average nominal transport capacity, passengers |

100 |

115 |

18 |

|

7 |

Trips per day (turns), no. |

2 380 |

750 |

8 800 |

|

8 |

Average trip per day, km |

58 422 |

28450 |

99 100 |

|

9 |

Route duration, hours |

17 |

16 |

18 |

Note: July 2017.

Source: Chisinau Municipality, Department of Public Transport.

As of July 2017, the RTEC owned and operated a total of 366 trolleybuses, including 88 units with a service life of up to 5 years, 124 units aged 5 to 10 years, 30 units with a service life of 11 to 15 years, 13 units with a service life of 16 to 20 years and 111 units with a service life of above 20 years. If we assume the operational lifespan of a trolleybus is 15 years (depending on the manufacturer), then 124 trolleybuses, or approximately 36% of the vehicle fleet, should be replaced as they have met or exceeded their operating terms. Every year RTEC organises the repair of 80 trolleybuses. The total of 366 trolleybuses includes 191 new AKSM-321 trolleybuses, accounting for around 52% of the trolleybus fleet, according to information provided by RTEC.

Also in July 2017, PUA had 136 buses, 60 of which had a service life of 10 to 15 years, 49 with a service life of 16-20 years and 7 with a service life of more than 20 years. The remaining 20 buses are reserve units either requiring capital repairs or scrapping. The normal lifespan of a bus is 12 years according to statements by PUA officials based on the recommendations of manufacturers. Thus, at least 56 vehicles (48%) in the running fleet and 76 vehicles (56%) of the total fleet should be replaced. Although the PUA mentions that it has not obtained sufficient funds from local public authorities, it has managed to keep its fleet in operation.

Another four bus routes are managed by private transport operators (No. 23, 10, 28 and 122). On these routes there are 42 bus stops with increased capacity, including route No. 23 (22 units), route No. 10 (2 units), route No. 28 (8 units) and route No. 122 (12 units).

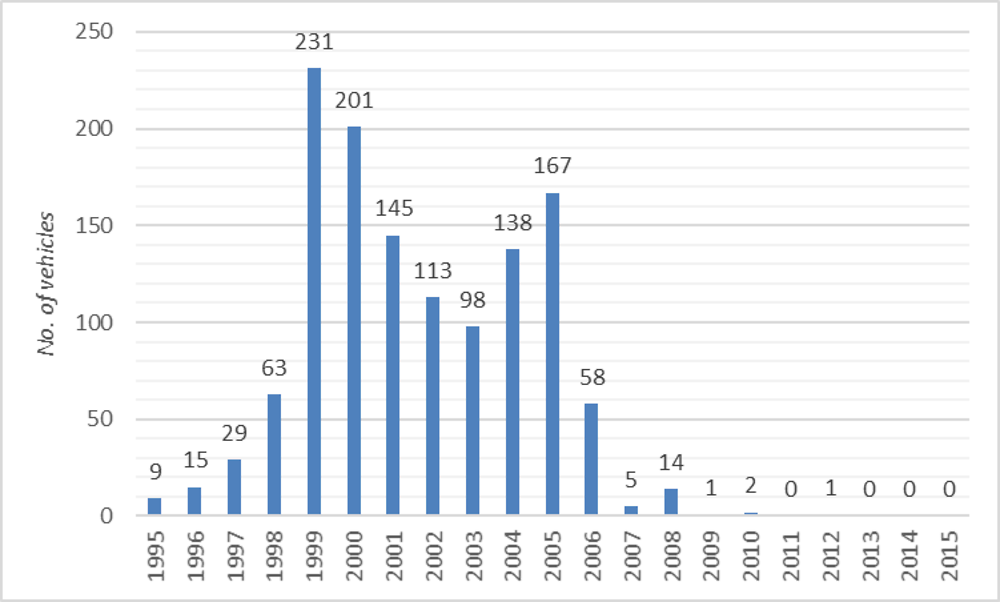

There are 15 private transport operators serving 55 suburban bus routes with a total fleet of 1 290 light class buses (minibuses). Although these have a nominal transport capacity ranging from 11 to 21 seats, it is well-known that this capacity is typically exceeded, in particular during peak hours. The most common light class buses are Mercedes-Benz Sprinters. The age structure of the light class fleet is shown in Figure 6.7. As mentioned above, the typical life of a minibus is around 7 years.

Between 2014 and 2017, the Public Transport and Communications Directorate optimised the public transport route network following the Chisinau Transport Strategy. This seeks to minimise the duplication of trolleybus and bus routes with secondary bus routes. Thus, 12 secondary bus routes have been cancelled, reducing the number of light class buses from 1 850 units in 2014 to 1 290 in 2017.

Figure 6.7. Age of minibus fleet (by year of manufacture)

Note: July 2017.

Source: Authors’ depiction based on information from minibus operators.

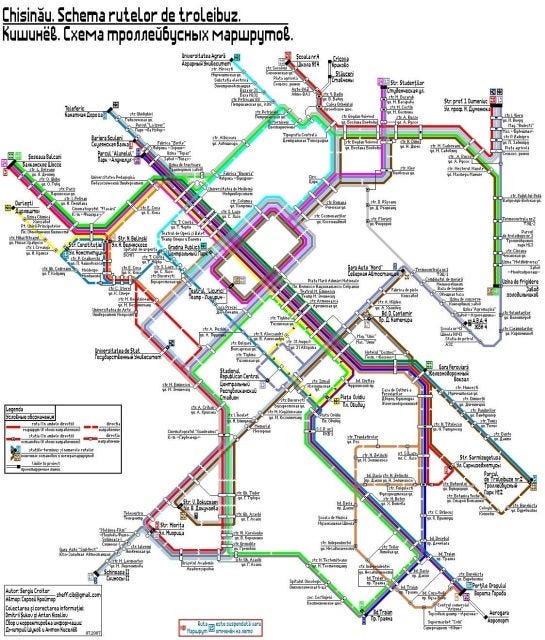

Street and transportation network

The Municipality of Chisinau owns and maintains 102.8 km of public roads.46 The public road transport network is a radial type, which provides relatively short direct links on the radial routes between the suburbs and the city centre. Links between peripheral districts involve tangential paths. Most routes are made to or through the city centre and radial routes are the most requested; thus, over 70 streets and boulevards in the city centre are overloaded. The trolleybus network also includes two ring routes. The scheme of the trolleybus network in Chisinau is shown in Figure 6.8.

Urban highway sections are characterised by high traffic density, involving 7 to 12 bus routes. Thus, about 50% of public transport vehicles cross the city centre, creating a number of traffic problems. Public transport vehicles are not separated from other traffic and there are no high-speed buses, although there are some low-floor buses in service. Low-floor buses not only speed up passenger embarkation and disembarkation, but they are also user-friendly for older people, people with disabilities and people with pushchairs.

The development of urban public transport in Chisinau has been influenced by the fact that the relatively small historical part of the city is quite distant from the four contemporary residential sectors (Botanica, Buiucani, Ciocana, and Riscani), which are connected with the city centre by a few magistral (arterial) roads. Interconnections across the sectors is underdeveloped. The situation is complicated by the fact that there are very few alternative routes to redirect traffic (lack of ring roads for transit, especially north-south), which causes 50% of the inter-urban transit to flow through central Chisinau. For these reasons, during peak hours all the bridges connecting the periphery with the centre are congested.

Figure 6.8. Chisinau trolleybus network

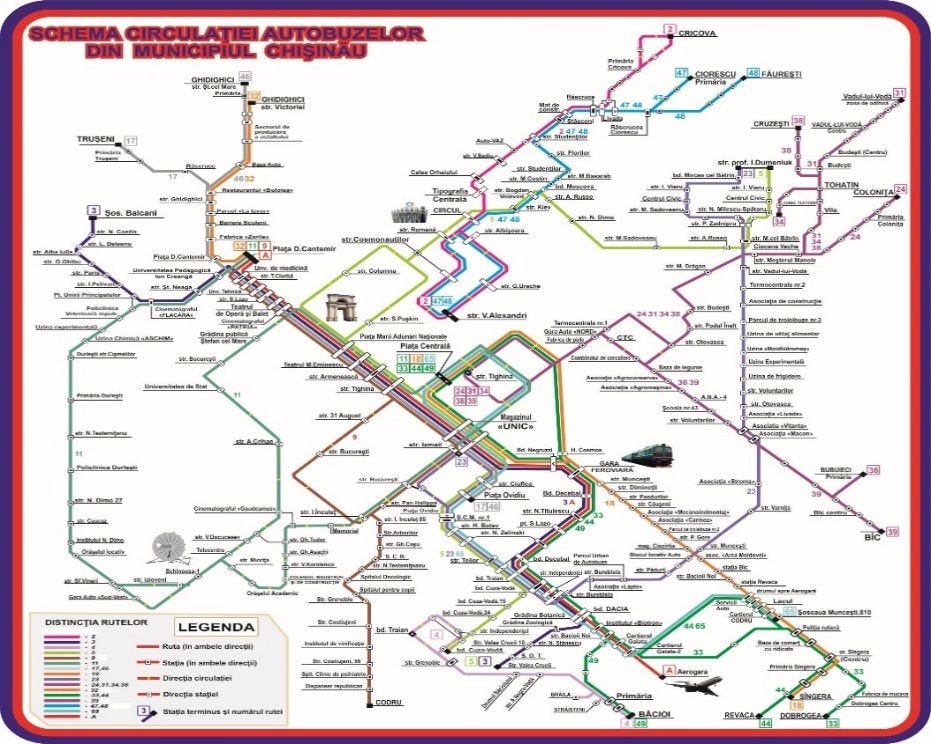

Of the 24 bus routes, only 7 are urban; the others serve the suburbs of Chisinau. The bus route scheme is shown in Figure 6.9.

Figure 6.9. Chisinau bus network

Light class buses serve 55 routes, representing 54% of the public transport network (in terms of the number of routes, not their total length), and predominantly serve streets and districts that are hard to reach by larger public transport vehicles. The characteristics of the public transport network in Chisinau are shown in Table 6.13.

Table 6.13. Summary of public transport routes in Chisinau

|

Indicator |

Total |

Trolleybus routes |

Bus routes |

Light class bus routes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No. and share of routes |

102 |

23 (22.5%) |

24 (23.5%) |

55 (54%) |

|

Type: - urban - suburban |

53 49 |

22 1 |

4 20 |

27 28 |

|

Route length, km |

2 873.8 |

534 |

810.9 |

1 528.9 |

|

Type: - urban - suburban |

1 396 1 477.8 |

514.1 19.9 |

128.6 682.3 |

753.3 775.6 |

Source: Consultant calculations based on Chisinau Electric Transport Company and Urban Bus Park.

There are 17 dispatchers in the regular public transport network: 4 on the bus routes and 13 on the trolleybus routes. There are 752 intermediate public stops along the routes, of which 520 are in urban areas and 232 in suburbs or along routes to them. In 330 public stations, bus shelters are installed, including 132 that are located in common with commercial units. It should be noted that 422 public stations are not equipped with a roof or pavilion. Some stations even lack name signs to indicate location, despite this being required under the Road Traffic Regulation, approved by the Government Decision No. 357 of 13 May 2009 (see Section 7.1.15).

6.2.3. City of Balti’s public transport fleet and network

The public transport network in Balti municipality comprises 4 trolleybus routes (Table 6.10), 11 main bus routes and 9 secondary bus routes (minibuses). The first trolleybus line in Balti was opened in 1972, with a length of 15 km. Twenty trolleybuses were run by the Trolleybus Directorate, which was reorganised in 1992 as a municipal enterprise called the Trolleybus Directorate of Balti. At the beginning of the 1990s, three routes covering 40 km were served by 90 trolleybuses.

Over time, however, insufficient funds led the trolleybus fleet in Balti to become outdated. Failure to replace vehicles meant that they fully exceeded their useful operating lives. Eleven trolleybuses were older than 10 years, while 24 had a working age of over 30 years. In order to renew the trolleybus stock, on 17 October 2012, Balti signed a EUR 3 million loan agreement with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) for the purchase of 23 new trolleybuses. At the same time, the EBRD provided a EUR 1.6 million grant to improve the infrastructure of the Trolleybus Directorate of Balti.

In 2013 and 2014 EBRD assisted in replacing 23 trolleybuses with new and used buses. By 2014 there were 35 trolleybuses, including 22 ZIU-9 trolleybuses, 3 AKSM-20101 trolleybuses from Belarus, 11 AKSM-30101 trolleybuses from Belarus, 1 Škoda 14Tr13/6M trolleybus from the Czech Republic and 7 VMZ-5298 trolleybuses from the Russian Federation. Today the age of the trolleybus fleet is as follows: 23 units are less than 5 years old and 11 are more than 10 years old. The others are not operational.

In July 2014, two new routes (No. 4 and 5) were opened. In 2015, the opening of route No. 6 to link the Dacia neighbourhood to the "Bessarabia - North" sausage plant was proposed, but the project was not implemented. Moreover, in January 2016, the trolleybus traffic was stopped on route No. 4 due to unprofitability.

Today the city of Balti has 48 trolleybuses. Thirty operate daily, while four are reserve buses. The remaining 14 buses are in various stages of disrepair and disuse. The trolleybus network is 47.8 km long and includes 66 stations.

Public transport is also provided by 48 regular buses and 116 minibuses. All are diesel-powered and the vast majority are 15 years or older.

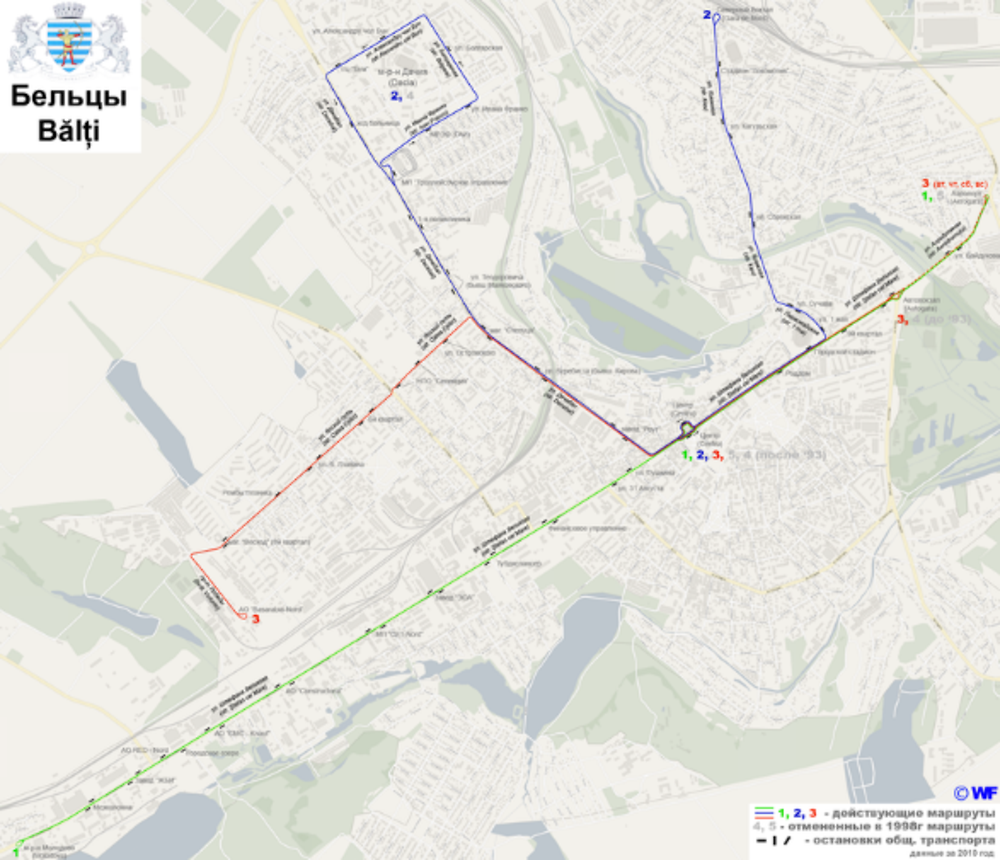

Figure 6.10. Balti trolleybus network

6.3. Greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution in Moldova

6.3.1. Greenhouse gas emissions and transport

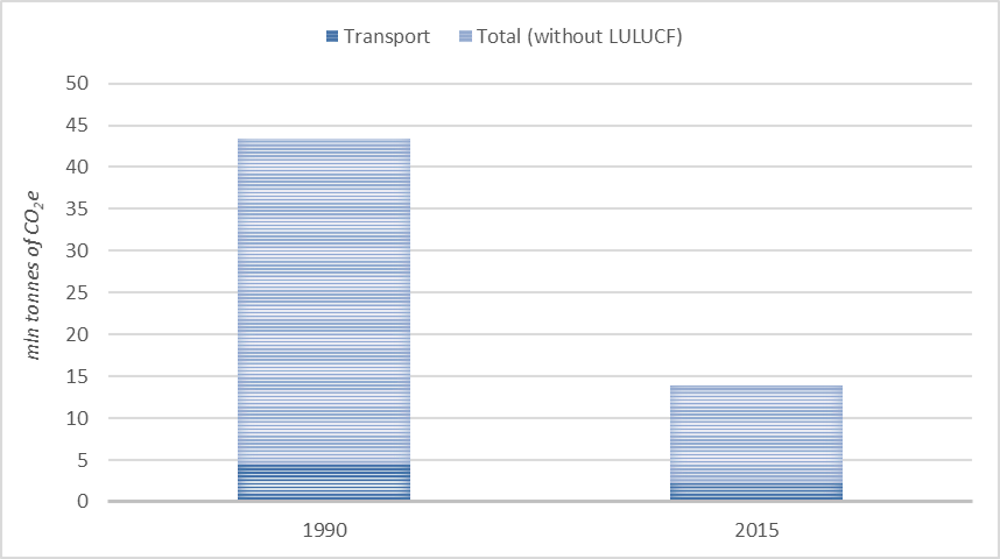

In 2015, overall GHG emissions in Moldova amounted to 13.95 million tCO2e, excluding land-use change and forestry (LULUCF), or 11.11 million tCO2e including the LULUCF sector (total net emissions are lower as Moldova’s LULUCF sector is a net carbon sink). GHG emissions from the transport sector accounted for 2.2 million tCO2e, (accounting for 23.2% of GHG emissions from the energy sector, which totalled 9.5 million tCO2e) (GoM, 2017[13]).

From these data it can be seen that the energy sector contributed the largest share of total emissions (68.1% without LULUCF in 2015). Emissions from the transport sector are included in the energy sector. The agriculture, waste management, and industrial production sectors account for the remainder of the emissions (15.2%, 11% and 5.7% in 2015, respectively).

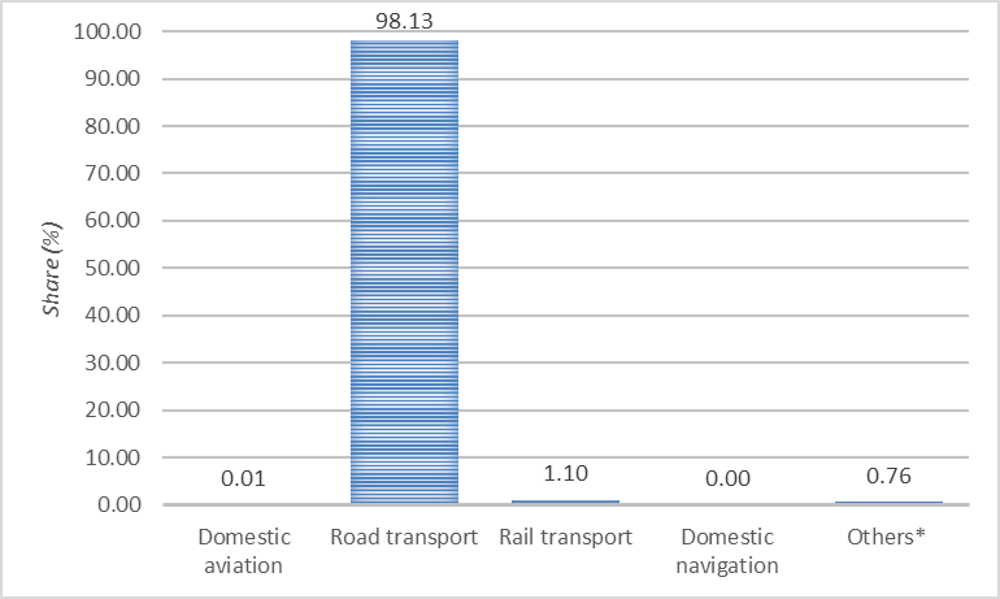

Figure 2.11 presents the transport sector’s contribution to overall GHG emissions in Moldova in 1990 and 2015. Although in absolute terms GHG emissions (both overall and those from transport) decreased over the period – mainly due to the fall in GDP and population decline – the transport sector’s share in total emissions increased from 10.3% in 1990 to 15.8% in 2015.

Figure 2.12 shows that emissions from road transport make up the bulk of GHG emissions from the transport sector. Whereas in 1990, road transport was responsible for 87.3% of transport emissions, by 2015 it had reached 98.1% (GoM, 2017[13]).

Figure 6.11. Share of transport sector in direct GHG emissions in Moldova, 2015

Note: *Including pipeline and off-road transportation

Source: (GoM, 2017[13]), National Inventory Report 1990-2015: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in the Republic of Moldova, p. 98, www.clima.md/download.php?file=cHVibGljL3B1YmxpY2F0aW9ucy80MjAwODJfZW5fbmlyNV9lbl8yOTEyMTcucGRm.

Figure 6.12. Transport’s contribution to direct GHG emissions in Moldova, 1990 and 2015

Note: LULUCF: land use, land-use change and forestry.

Source: (GoM, 2017[13]), National Inventory Report 1990-2015: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in the Republic of Moldova, pp. 57, 97. www.clima.md/download.php?file=cHVibGljL3B1YmxpY2F0aW9ucy80MjAwODJfZW5fbmlyNV9lbl8yOTEyMTcucGRm.

GHG emissions per capita decreased by 65.2% between 1990 and 2015 (i.e. from 9.95 tonnes of CO2e to 3.46 tonnes of CO2e). GHG intensity decreased in the same period by 54.5% (i.e. from 4.39 kg CO2e to 2.0 kg CO2e 2010 USD). However, these values are still among the highest of the transition economies (GoM, 2017[13]).

In Table 6.14, we see that CO2 and NOx emissions also decreased by half and SO2 emissions by more than 65% in the period 1990-2015.

Table 6.14. Trend in transport GHG emissions, 2010-15

(% change from 1990)

|

1990 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CO2 |

100 |

46.2 |

48.7 |

42.9 |

45.4 |

47.2 |

49.7 |

|

CH4 |

100 |

33.4 |

33.6 |

28.6 |

28.6 |

28.7 |

30.2 |

|

N2O |

100 |

34.3 |

35.5 |

32.4 |

32.2 |

30.4 |

34.0 |

|

NOx |

100 |

47.1 |

49.7 |

43.9 |

46.4 |

47.9 |

50.8 |

|

CO |

100 |

33.5 |

34.8 |

29.4 |

28.7 |

29.0 |

30.1 |

|

NMVOC |

100 |

33.6 |

35.11 |

29.6 |

29.0 |

29.3 |

30.3 |

|

SO2 |

100 |

57.8 |

61.4 |

55.1 |

59.4 |

62.2 |

65.8 |

Note: NMVOC: non-methane volatile organic compounds

Source: (GoM, 2017[13]), National Inventory Report 1990-2015: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in the Republic of Moldova, pp. 96-97, www.clima.md/download.php?file=cHVibGljL3B1YmxpY2F0aW9ucy80MjAwODJfZW5fbmlyNV9lbl8yOTEyMTcucGRm.

Between 2010 and 2015, direct GHG emissions from transport increased by 7%: from about 2.05 million tCO2e in 2010 to 2.2 million tCO2e in 2015 (Table 6.15).

Table 6.15. Volume of GHG emissions from transport, 2010-15

(kilotonnes of CO2e)

|

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CO2 |

2 007.4 |

2 116.7 |

1 862.9 |

1 862.9 |

2 049.6 |

2 158.1 |

|

CH4 |

10.9 |

11.0 |

9.3 |

9.3 |

9.4 |

9.9 |

|

N2O |

35.4 |

36.6 |

36.6 |

33.4 |

31.3 |

35.0 |

|

Total |

2 053.7 |

2 164.3 |

1 905.6 |

2 015.0 |

2 090.3 |

2 203.0 |

Source: (GoM, 2017[13]), National Inventory Report 1990-2015: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in the Republic of Moldova, p. 97, www.clima.md/download.php?file=cHVibGljL3B1YmxpY2F0aW9ucy80MjAwODJfZW5fbmlyNV9lbl8yOTEyMTcucGRm.

In the period 2010-2015 the road sub-sector experienced an 8% increase in total direct GHG emissions, while those from the railway sub-sector decreased by 58% (Table 6.16).

Table 6.16. Breakdown of GHG emissions from transport, 2010-15

(kilotonnes of CO2e)

|

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Domestic aviation |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.03 |

|

Road transport |

1 993.9 |

2 111.2 |

1 845.1 |

1 965.7 |

2 070.4 |

2 161.7 |

|

Rail transport |

57.3 |

52.7 |

56.6 |

36.2 |

3.0 |

24.2 |

|

Domestic navigation |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

|

Others* |

2.1 |

0.0 |

3.3 |

12.6 |

16.5 |

16.7 |

Note: *including pipeline and off-road transportation.

Source: (GoM, 2017[13]), National Inventory Report 1990-2015: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in the Republic of Moldova, p. 98, www.clima.md/download.php?file=cHVibGljL3B1YmxpY2F0aW9ucy80MjAwODJfZW5fbmlyNV9lbl8yOTEyMTcucGRm.

The emission factors outlined in Table 6.17 were used to estimate the GHG emissions from transport in Moldova presented in the tables and graphs above, which use data from the National Inventory Report 1990-2015 (GoM, 2017[13]). According to the revised 1996 and 2006 IPCC Guidelines (IPCC, 1996[14]) (IPCC, 2006[15]), the carbon intensity of natural gas and petroleum gas is lower than for diesel and petrol fuels, even if we consider the high global warming potential (GWP) coefficients for methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and most probably GHGs among the non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs).47 In terms of air pollution, natural gas provides the best (i.e. the lowest) combined value of CO and NOx emissions per energy used.

Table 6.17. Comparison of emissions from fuels used in the transport sector

(kilogramme per terajoule)

|

Fuel type |

CO2 |

CH4 |

N2O |

NOx |

CO |

NMVOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Petrol |

69 300 |

33 |

3.2 |

600 |

8 000 |

1 500 |

|

Diesel |

74 100 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

800 |

1 000 |

200 |

|

Natural gas |

56 100 |

92 |

3 |

600 |

400 |

5 |

|

Petroleum gas |

63 100 |

33 |

3.2 |

600 |

8 000 |

1 500 |

Source: (GoM, 2017[13]), National Inventory Report 1990-2015: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in the Republic of Moldova, p. 98, www.clima.md/download.php?file=cHVibGljL3B1YmxpY2F0aW9ucy80MjAwODJfZW5fbmlyNV9lbl8yOTEyMTcucGRm.

6.3.2. Nationally appropriate mitigation actions

Moldova has submitted to the UNFCCC Secretariat its intended nationally determined contribution – INDC (GoM, 2015[16]). The INDC sets out the expected environmental goals and actions after 2020. The main goals are as follows:

Unconditional goal: 64-67% reduction of GHG emissions by 31 December 2030 from the baseline year 1990.

Conditional goal – 78% reduction of GHG emissions by 31 December 2030 from the baseline year 1990. This goal is conditional on additional international investment, and access to the mechanism for the transfer of low-carbon technologies, green climate funds and the “flexibility” mechanism for countries in transition.

Nationally appropriate mitigation actions (NAMAs) refer to a set of policies and actions that countries undertake as part of their commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These aim for transformational change within a single sector or across two or more sectors of the economy. Developed countries can support the implementation of NAMAs in transition countries by financing technologies or capacity building activities.

The UNFCCC website provides a NAMA Register – a publicly accessible platform for uploading all countries’ NAMAs. This makes it possible to inform the public where financial or other support for the development or implementation of NAMAs is needed.

The UNFCCC Register contains three NAMA projects for Moldova:

1. “Use of energy willow for heat generation in the Republic of Moldova” in the section “NAMA Seeking Support for Implementation”. Implementing agency – Ministry of Agriculture, Regional Development and Environment.48 The total project cost is about USD 94 million, with expected international support of about 90%. The project has not yet received support.

2. “Afforestation of degraded land, riverside areas and protection belts in the Republic of Moldova”, in the section “NAMA Seeking Support for Implementation”. Implementing agency – Ministry of Agriculture, Regional Development and Environment.49 The total project cost is about USD 151 million, with expected international support of about 73%. The project has not yet received support.

3. “Implementation of soil conservation tillage system in the Republic of Moldova”, in the section “NAMA Seeking Support for Implementation”. Implementing agency – Ministry of Agriculture, Regional Development and Environment.50 The total project cost is about USD 258 million, with expected international support of about 70%. The project has not yet received support.

6.3.3. Air pollution

Law No. 1422 of 17 December 1997 on Atmospheric Air Protection, as amended, is the main legislation regulating atmospheric emissions. Art. 17 regulates emissions from transport. It states that maximum emissions standards must not be exceeded.

Article 56 of Law No. 1515 of 16 June 1993 on Environmental Protection, as amended, states that the management bodies in the energy, industry, agriculture sectors, as well as the local public administration authorities and the environmental and health authorities, are obliged, among others, to:

define and propose to the government for approval the annual limits of energy production and consumption, and the admissible annual limits of harmful emissions in the atmosphere from fixed and mobile sources, and to not allow the established limits and norms to be exceeded

create and ensure the functioning of an air quality surveillance system throughout the country, based on international standards.

The Environmental Audit Report on Air Quality in the Republic of Moldova (GoM, 2018[17]), as approved by Government Decision No. 65 of 30 November 2017, reviews the situation with regard to addressing air quality problems in the country. While the report notes that air pollution from vehicles has declined (8-10 times below the levels 30 years ago), it also cites transport as the main source of air pollution, in particular in urban areas. It also states that on the country level transport accounts for 86.2% of all harmful substances emitted into the air. This results from the increase in the number of vehicles, exacerbated by the fact that old used vehicles – those in operation for seven years or more – are being imported. The report states that between 2014 and 2016, the number of vehicles registered increased by 51 200 units.

However, total pollution from combustion engines decreased by 13 000 tonnes in 2016 from 2014 levels (from 179 000 to 166 000 tonnes), due to the increased in registered electric and natural gas-powered vehicles. But a significant proportion of registered vehicles still in circulation use diesel as fuel (35%), including those in urban public transport.

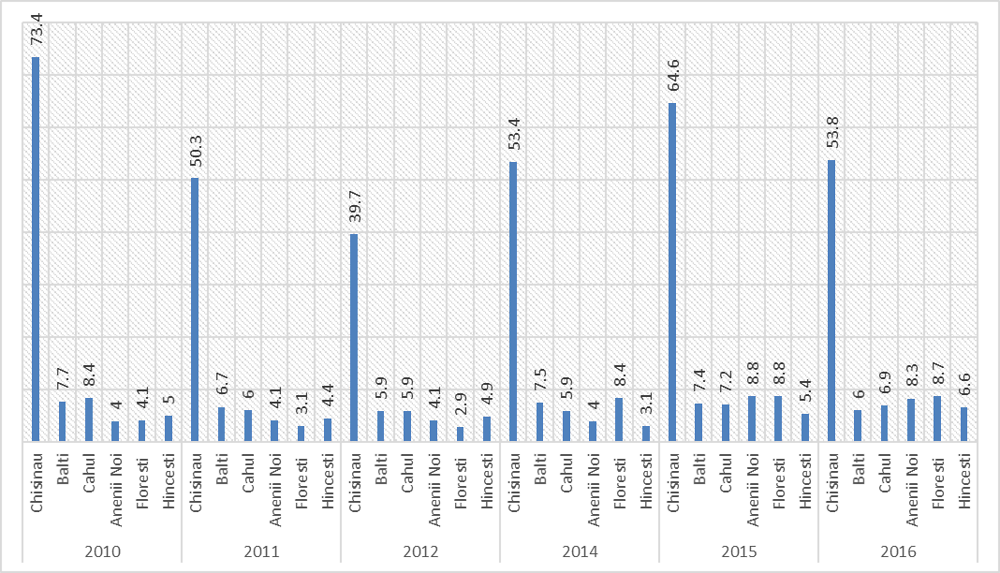

Figure 6.13 shows the emission trends of harmful substances from road transport in key cities in Moldova for 2010-2016.

Figure 6.13. Emissions of harmful substances from automobiles in major cities in Moldova, 2010-16

Source: (GoM, 2018[17]), Environmental Audit Report on Air Quality in the Republic of Moldova, p.12, http://lex.justice.md/UserFiles/File/2018/mo18-26md/raport_65.doc (based on data from 2016 IES Yearbook on Environmental Protection in the Republic of Moldova).

The audit report cited the lack of timely information on air quality as an important problem to be addressed. In 2015, the State Environmental Inspectorate submitted a proposal to the National Environmental Fund to finance the project "Strengthening the material and technical basis of ecological investigation centres (in Chisinau, Balti and Cahul)", valued at MDL 2 million (USD 108 000). The project objective was to modernise environmental monitoring equipment, including equipment capable of measuring emissions from road transport. The project was not funded.

The audit report points out that the existing institutional organisation is not integrated, is characterised by poor co-operation among public authorities and institutions responsible for air quality management, and does not ensure an organised or unified approach to problems related to air quality. Moreover, measures taken to prevent and mitigate air pollution are inefficient. In the past, the Ministry of Environment did not have a division responsible for air pollution. Following government reforms, however, the Ministry of Agriculture, Regional Development and Environment (MARDE) has established the Air and Climate Change Office.

The audit revealed weaknesses in vehicle testing, including the failure, or even absence, of particular meters and gas analysers. Automobiles “imported” from abroad, with foreign registration numbers, are often not tested for their technical condition, instead relying on technical inspection certificates from the country of origin. Moreover, information on vehicle testing is general and therefore it is difficult to assess the impact of vehicle traffic on air quality.

Moldova does not apply EU standards for vehicle emissions. These are still regulated according to regional, Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)-administered, formerly Soviet, GOST (Russian for “state”, “national”) standards, which require the removal of 50% of particulates from diesel engines (ГОСТ 17.2.2. 03-87 and ГОСТ-21393-75).51 According to experts cited in the audit report, emissions do not exceed current GOST standards, largely because they are equivalent only to Euro 0 or Euro 1/I standards.

The audit found no real environmental factors in the strategic documents in the transport sector, such as the National Transport Strategy 2008-2017 (GoM, 2008[18]) and the Transport and Logistics Strategy 2013-2022 (GoM, 2013[19]).

There are two main public entities in Moldova responsible for air monitoring:

1. The State Ecological Inspectorate (Inspectoratul Ecologic de Stat – IES52)

2. The State Hydrometeorological Service (Serviciul Hidrometeorologic de Stat – SHS53).

Both of these fall under the remit of the Ministry of Agriculture, Regional Development and Environment (MARDE). According to Government Decision No. 847 of 18 December 2009 on the Approval of Regulation on Organisation and Operation of the Ministry of Environment, as subdivisions of MARDE, the IES and SHS are responsible for air pollution monitoring and air protection.

The monitoring network comprises 17 stationary monitoring stations located in five industrial centres (Chisinau – 6 stations; Balti – 2; Bender – 4; Tiraspol – 3; and Ribnita – 2). These collect air samples for testing for 8-9 pollutants: particulates, sulphur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and four to five specific pollutants.54 The daily values as well as seasonal maps of atmospheric air pollution for these five cities (urban areas) are published on the SHS website.55

The audit report noted, however, that the results from the 17 stations do not sufficiently reflect the real air quality situation because they are collected only three times a day. Moreover, the results are not live, but processed and presented the following day (GoM, 2018[17]).

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Social Protection sets out the norms for the maximum allowed concentrations of pollutants in the atmosphere, while compliance with air quality standards is monitored by the Ministry’s National Agency for Public Health.

Road transport is the main source of air pollution in Moldova, in particular in urban areas. According to measurements carried out by the Municipal Centre of Preventive Medicine in eight points in Chisinau, and the data of the national meteorological service "Hydrometeo", the air in Chisinau is polluted with one or more types of toxic gas on 50% of the days of the year (BCI and TUM, 2006[20]).

Laboratory surveys of air samples carried out by the Municipal Centre for Preventive Medicine on the orders of Chisinau’s chapter of the non-government organisation (NGO) Ecological Movement of Moldova (Mișcarea Ecologistă din Moldova – MEM)56 showed that high levels of pollution are recorded near the main routes, such as in the area of Bănulescu-Bodoni Street, Vasile Alecsandri St. – Hancesti St., Iu. Gagarin Bd., Tighina St., Ismail St., Alba-Iulia Street; and transport node Ismail - Calea Basarabiei - Varniţa - Calea Moşilor. In these locations, the maximum concentrations of formaldehyde – CH2O (1.2–5.7 times the maximum allowable concentrations – MAC), particulates (1.2–3.6 times MAC), sulphur dioxide (1.2–7.0 times MAC), and ozone (1.1–3.6 times MAC) are exceeded substantially. Heavy concentrations of formaldehyde have been detected even in the air samples in the middle of Valea Morilor Park. Another acute environmental and health problem is the increased amount of dust in the atmosphere due to the poor state of roads (BCI and TUM, 2006[20]).

While air pollution data in other Moldovan cities are not readily available or reported,57 they too experience air pollution problems typical of cities in the eastern part of Europe. Of particular concern are levels of PM2.5 and PM10 from using wood and coal for home heating and from diesel fuels.

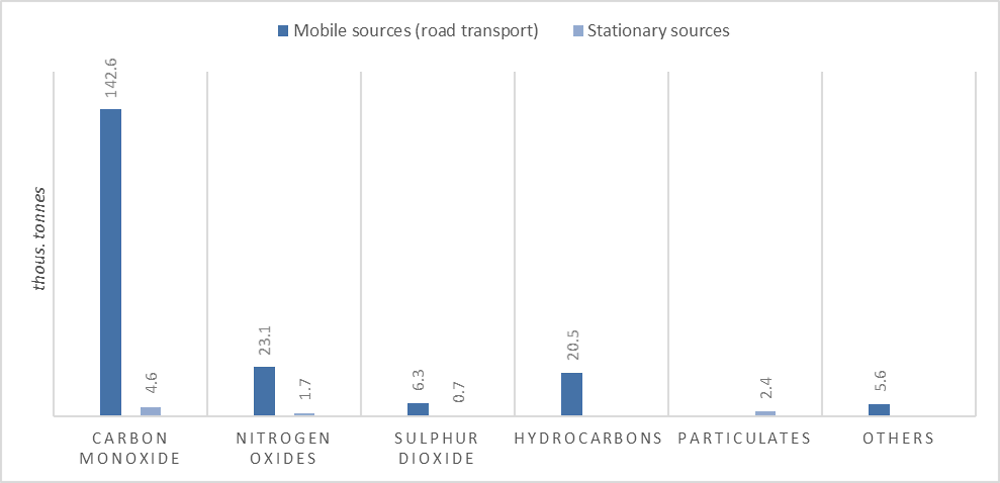

According to the WHO database (2018), every year ambient air pollution in Moldova causes about 3 500 deaths, most of which are due to ischaemic heart diseases.58 This is a significant increase on the figure stated in the 2009 WHO Moldova profile, which estimated that outdoor air pollution had caused 1 000 deaths a year since 2004 (WHO, 2009[21]). As can be seen in Table 6.5 above, in 2010-2017 the number of registered vehicles in Moldova increased by 37.8%. It is therefore not surprising that in 2018 road transport emitted 31 times more carbon monoxide (CO), 14 times more nitrogen oxides (NOx) and 9 times more sulphur dioxide (SO2) than stationary sources (Figure 6.14).

Figure 6.14. Air pollution from transport versus stationary sources in Moldova, 2018

Note: Values for the last three categories (hydrocarbons, particulates, others) were available only for one source group. Data on districts on the left bank of the Dniester River and the Bender Municipality not included.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (www.statistica.md).

6.3.4. Influence of air pollution from diesel engines on human health

Diesel engines emit carbon dioxide (CO2), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulphur dioxide (SO2) and particulate matter (PM). The air pollution from diesel engines, especially older ones, poses major environmental and health risks to the population (Box 6.1). Increased air pollutants carry a risk of mortality, in particular among people of over 65 (Pope et al., 1995[22]). Above all, diesel exhaust is a Group 1 carcinogen,59 causing lung cancer and being linked to bladder cancer.

Box 6.1. The impact of diesel exhaust emissions

Carbon dioxide (CO2): non-toxic, but as a greenhouse gas it causes climate change.

Carbon monoxide (CO): a temporary atmospheric pollutant in some urban areas, chiefly from the exhausts of internal combustion engines. Carbon monoxide is absorbed through breathing and enters the bloodstream through gas exchange in the lungs. It is toxic when encountered in concentrations above about 35 ppm.

Nitrogen oxides (NOx): NOx refer to a mixture of nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2). They are produced during combustion, especially at high temperatures. Due to reactions and photolysis by sunlight, they are the main source of tropospheric ozone. NOx may react with water to make nitric acid, which may end up in the soil where it makes nitrate, which is of use to growing plants. NOx in combination with other pollutants creates urban smog. High concentrations of nitrogen dioxide are harmful to humans because they cause inflammation of the airways.

Sulphur dioxide (SO2): SO2 pollution levels from diesel mainly depend on the quality of the fuel. If the fuel contains more sulphur, the diesel exhaust will contain more SO2. Sulphur dioxide emissions are a precursor to acid rain and atmospheric particulates. Inhaling sulphur dioxide is associated with increased respiratory symptoms and diseases, and difficulty in breathing.

Particulate matter (PM): the major pollutants with negative health effects are PM (2.5 and 10). The particles are so small they can penetrate into the deep regions of the lungs. It is estimated that approximately 3% of cardiopulmonary and 5% of lung cancer deaths are attributable to PM globally. Exposure to PM2.5 reduces life expectancy by about 8.6 months on average.

Since 2000, PM pollution has been estimated to cause 22 000 to 52 000 deaths every year in the United States. It also contributed to about 370 000 premature deaths in Europe in 2005, and 3.22 million deaths globally in 2010, according to a study of the global burden of disease (Lim et al., 2012[23]).

There is no evidence of a safe level of exposure to PM, or a threshold below which no adverse health effects occur. The World Health Organization Air Quality Guidelines values for PM in 2005 were as follows (WHO, 2013[24]):

for PM2.5: 10 micrograms per cubic metre (μg/m3) for the annual average and 25 μg/m3 for the 24-hour mean (not to be exceeded on more than 3 days/year)

for PM10: 20 μg/m3 for the annual average and 50 μg/m3 for the 24-hour mean.

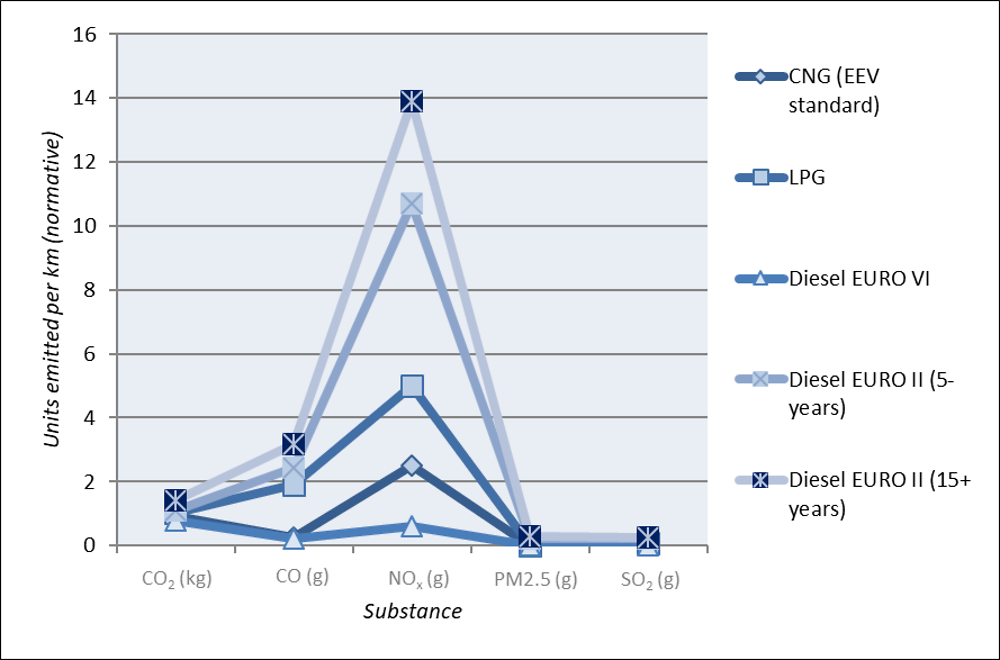

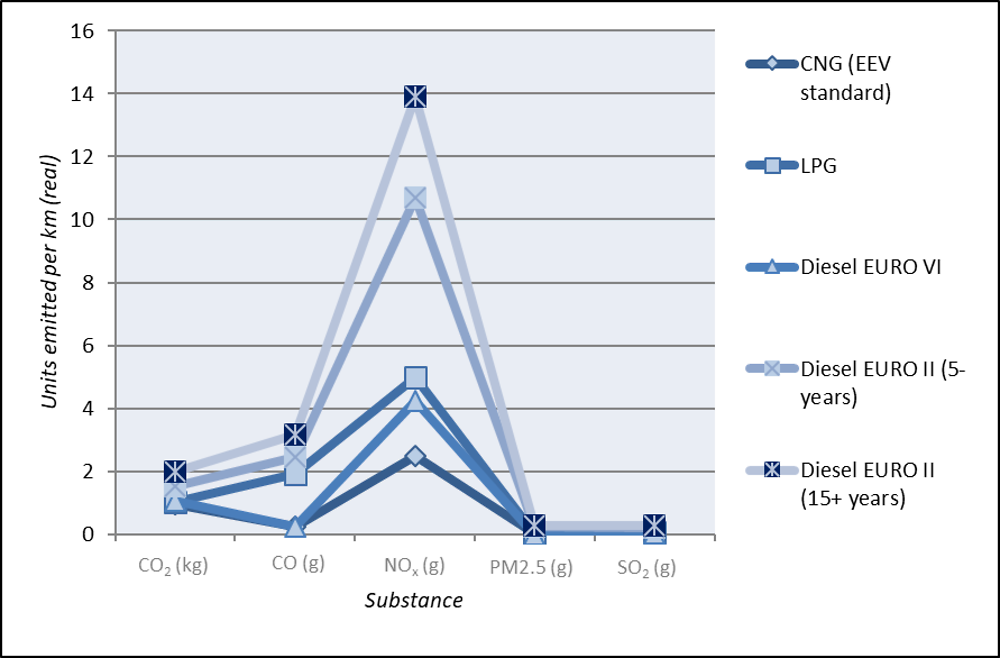

Figure 6.15 and Figure 6.16 compare the increased emissions of health-damaging substances by old diesel-powered engines (especially those aged at least 15 years) with modern diesel engines and alternative fuels, compressed natural gas (CNG) and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG).

Figure 6.15. Assumed amount of health-damaging substances emitted per distance travelled (normative*)

Note: *for a discussion of normative and real pollution factors, see Section 2.3.1.

Source: (DieselNet, 2016[25]), “EU: Heavy-Duty Truck and Bus Engines: Regulatory Framework and Emission Standards”, DieselNet website, www.dieselnet.com/standards/eu/hd.php (last accessed 30 March 2017).

Figure 6.16. Assumed amount of health-damaging substances emitted per distance travelled (real*)

Note: *for a discussion of normative and real pollution factors, see Section 2.3.1.

Source: (DieselNet, 2016[25]), “EU: Heavy-Duty Truck and Bus Engines: Regulatory Framework and Emission Standards”, DieselNet website, www.dieselnet.com/standards/eu/hd.php (last accessed 30 March 2017).

The replacement of outdated buses with modern diesel-powered or natural gas-powered buses – or the expansion of trolleybus networks in place of diesel-powered vehicles – would help significantly to reduce the amount of major air pollutants, such as particulates, NOx and SO2. A clean public transport programme is thus justified from a public health standpoint.

6.4. The energy sector

6.4.1. Energy efficiency and fuel standards

Law No. 461 of 30 July 2001 on the Petroleum Products Market provides for the formation of an organisational, legal and economic framework for ensuring the economic security of the country and regulating the import, transport and marketing of petroleum products on the domestic market as strategic products with a special regime of activity.

Law No. 142 of 2 July 2010 on Energy Efficiency regulates activities meant to reduce the energy intensity of the national economy and the negative impact of the energy sector on the environment. This law creates the necessary legal framework for the implementation of EU Directive 2006/32/EC on energy end-use efficiency and energy services (EU, 2006[26]). The Energy Efficiency Agency, subordinated to the central specialised body in the energy field (i.e. the Ministry of Economy and Infrastructure), has a separate legal entity status and a separate budget (Art. 8, par. (1) of the law).

The Energy Strategy of the Republic of Moldova until 2030 (GoM, 2013[27]), approved by Government Decision No. 102 of 5 February 2013, provides benchmarks for the development of the energy sector in Moldova in order to create the necessary basis for economic growth and social welfare. Through this document, the government presents its vision and identifies the country's strategic opportunities in the rapidly changing energy landscape of the geopolitical space that includes the Central, Eastern and Southern Europe region, Russian Federation and the Caucasus region.

The strategy highlights the country’s priority issues, which call for quick solutions and a reshaping of objectives to achieve an optimal balance between internal resources (both currently used and projected) and the country’s emergency needs, and the Energy Community (see the next section) and national targets, international obligations on treaties, agreements and programmes (including neighbourhood policy) of which the Republic of Moldova is a member. The strategy outlines the general strategic objectives and implementation measures for the period 2013-2030, as well as the specific strategic objectives for the 2013-2020 and 2021-2030 phases.

The National Energy Efficiency Programme 2011-2020 (GoM, 2011[28]), as approved by Government Decision No. 833 of 10 November 2011, sets long-term energy saving targets of up to 20% by 2020. It states that 10% of biofuels are to be produced from renewable sources by 2020, with intermediate targets (by 2015) of:

6% of ethanol and petrol blends in the volume of petrol sold

5% of biodiesel blend in the volume of gas oil sold.

According to the Road Transport Code, from 1 January 2020, only buses and coaches complying with at least Euro I norms (Art. 153 par. (9)) will be allowed for road transport.

6.4.2. Electricity network

Moldova’s energy security depends on Russian gas and electricity delivered from Transnistria.60 The limited options for diversifying energy routes and supplies make the country reliant on political stability in Romania and Ukraine. Moldova’s electricity sector is partially unbundled and privatised. Electricity generation is separated from the transmission and distribution system. The electricity distribution system is privatised, while generation and transmission are under state ownership.

A self-sufficient power sector is not an option for a country the size of Moldova. The country’s electricity network is connected to Ukraine only and the countries’ two systems operate in parallel. Both systems were originally designed as an integral part of the Soviet grid in its southern region.61 At the moment, Moldova serves only as an island mode for local supply.62 However, integrating with the regional power market is a policy priority for Moldova. In 2010, Moldova joined the Energy Community – an international organisation that aims to create a pan-European (EU and non-EU countries) energy market – and plans to fully synchronise its network with the European electricity market.63 As a first step, Moldova introduced market principles, especially for the management of its natural gas and electricity sectors, based on the adoption of core EU energy legislation which is part of its acquis communautaire (IRENA, 2019[29]).

Its planned integration into the EU system via Romania and Bulgaria64 will not only help to improve country’s efficiency in the electricity market, but will also secure a more diversified power supply and extend the country’s generation capacity. Connecting to the competitive Romanian market will also help to increase transparency in Moldova’s electricity procurement (currently based on bilateral contracts mainly through intermediaries). Conversely, while continued dependency on Ukraine (and Transnistria) will possibly secure lower electricity prices, this will be at the cost of market dysfunctionalities, vulnerability to supply disruptions and uncertainty for potential (European) investors.

In 1997, after implementing reforms in the energy sector, Moldenergo – a state monopoly for the production of heat and electricity – broke up into 16 new entities (i.e. eight electricity generation companies, three district heating companies and five electricity distribution companies). This power sector reform was largely prompted by supply shortages and service disruptions. In 2000, three of the five regional electricity distribution networks (REDs Chisinau, Centru and Sud) were sold in an open tender to the Spanish utility and investor company Union Fenosa International. In 2008, the three Moldovan distribution companies merged into RED Union Fenosa, which in 2010 became part of the international group Gas Union Fenosa (UNECE, 2009[30]).65 This company holds around 70% of market shares in Moldova (covering 19 regions, including the capital of Chisinau; (PRNewswire, 2019[31]), while the remaining 30% are held by the state-owned RED enterprises (RED Nord based in Balti and RED Nord-Vest based in Donduseni). The transmission network is operated by one state-owned company, Moldelectrica.66