This chapter examines Malta’s existing legislative and institutional framework for public integrity of elected and appointed officials. In particular, this chapter identifies key areas to strengthen the Standards in Public Life Act to ensure coverage of at-risk elected and appointed positions, address incompatibilities, and create a common understanding of expected conduct and behavior. Additionally, this chapter provides recommendations to protect the independence and strengthen the functions of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life, as well as improve the functions of the Committee for Standards in Public Life.

Public Integrity in Malta

2. Strengthening the Standards in Public Life Act of Malta

Abstract

2.1. Introduction

Public integrity is an inherent value of democracy; it ensures the government responds to the interests of the people. Integrity is about everybody having a voice in the policy-making process and preventing undue influence of government policies. Political leaders – both elected and appointed – are essential to public integrity: by setting the “tone at the top”, they demonstrate to society that integrity is a governance issue the government takes seriously. Sustaining this commitment however requires that integrity expectations for political leaders are codified into the legislative and institutional frameworks, that political leaders adhere to the highest standards of conduct in their behaviour, and that they are held accountable when there are breaches.

Over the past several years, Malta has implemented a number of reforms to strengthen public integrity, particularly for elected and appointed officials. These reforms have included the 2017 Standards in Public Life Act1 (herein “Standards Act”) as well as the appointment of Malta’s first Commissioner for Standards in Public Life (herein “the Commissioner”) in 2018. The Standards Act – which applies to Members of Parliament, Ministers, Parliamentary Secretaries and persons of trust – empowers the Commissioner to support elected and appointed officials in carrying out their public duties in the public interest. In particular, the Standards Act enables the Commissioner to review the conduct of these officials in terms of their statutory and ethical duties as persons in public life. The Standards Act sets out codes of ethics for elected and appointed officials, and also establishes the Commissioner as the responsible entity for reviewing interest declarations submitted by MPs, ministers and parliamentary secretaries, which until 2018 were only scrutinised by the press. Moreover, the Standards Act grants the Commissioner power to introduce legislation on key integrity issues, including lobbying.

These reforms do not exist in a vacuum: the assassination of the investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia triggered an outcry about the state of the rule of law and media freedom in Malta, giving rise to a strong public demand for anticorruption and rule of law reforms, and a more active and organised civil society. The years following have found Malta confronted with an unprecedented wave of controversies concerning the integrity of senior government officials up to the highest level (GRECO, 2019[1]), leading to an overall high level of perception of corruption.

These reforms also respond to recommendations by the international community: for instance, in its Fifth Evaluation Report, the Council of Europe’s Group of States Against Corruption (GRECO) recommended to improve awareness raising actions amongst public officials, tighten compliance measures with the integrity standards in place, fill gaps in respect of certain groups of public officials who currently are not covered by any integrity standards, and supplement the integrity system for managing conflicts-of-interest with clear guidance (GRECO, 2019[1]).

In face of these challenges, both the Standards Act and the Commissioner have proven instrumental in advancing the implementation of an integrity framework for those in public life in Malta (European Commission, 2020[2]). Together, the legislative and institutional framework have put the issues of integrity, accountability and transparency at the forefront of the public debate. However, challenges remain in terms of raising ethical awareness amongst elected and appointed officials and in the wider society, and effectively enforcing integrity standards through consistent procedures for monitoring, investigating and sanctioning wrongdoing.

This chapter analyses the omissions, inconsistencies and overlaps in the Standards Act. It provides recommendations to the Government of Malta through the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life regarding potential amendments to the Standards in Public Life Act to address the existing challenges.

2.2. A clear and comprehensive legislative framework for public integrity

A key starting point in any integrity system is a legislative framework that provides clear and common definitions, sets high integrity standards for public officials, and clarifies the institutional responsibilities for developing, implementing, enforcing and monitoring the different elements of the system (OECD, 2017[3]). Setting high standards of conduct ensures clarity regarding acceptable behaviour and provides a common framework to ensure accountability (OECD, 2020[4]). Elected and appointed officials face specific challenges and clear ethical standards is critical for strengthening good governance, public integrity and the rule of law. For example, a member of parliament may find themselves in conflict amongst their different responsibilities: serving constituents, advancing legislation that benefits the wider population or responding to the priorities of the political. Having robust, clear and consistently enforced standards can help guide them navigate these challenges, while also preventing abuse of office and other forms of corruption. For others, like appointed officials, clear integrity standards are a guidepost in carrying out their public duties. Additionally, having clear ethical standards can be a unifying factor, allowing elected officials to overcome obvious political differences and build a sense of collegiality (OSCE, 2012[5]). Other high-risk positions, including elected officials at the local level, also benefit from clear standards because of their high proximity to citizens and firms, which creates more opportunities for corruption and misconduct (OECD, 2017[6]).

However, reaching consensus on integrity standards for elected and appointed officials as well as neutrally enforcing these standards can prove challenging, especially in environments of increasing partisanship and polarisation. Indeed, it is one thing to recognise a distinctive set of ethical principles for political office, yet another to achieve widespread consensus on exactly what those principles demand in any given situation (Committee on Standards in Public Life, 2014[7]). The competitive dimension of the political process also adds a layer of complexity: elected officials are accountable in terms of whether they have fulfilled the formal responsibilities of their office, and in terms of whether their constituents approve the policies they have enacted or supported. Political systems that blur the distinction between formal accountability (did they act ‘properly’?) and political accountability (do we approve what they did?) can “risk subordinating ethical considerations to expediency, or eliminating the distinct political dimensions of judgment” (Committee on Standards in Public Life, 2014[7]).

2.2.1. Closing the loopholes in the Standards in Public Life Act

With the aim of setting and safeguarding high standards of conduct for elected and appointed officials, the Standards Act is a critical tool for guiding behaviour. To provide a fit-for-purpose framework, the following recommendations identify key areas where the Standards Act could be strengthened.

The Ministry for Justice could widen the scope of the Standards Act to cover at-risk elected and appointed positions

Currently, the Standards Act’s scope covers Members of the House of Representatives, ministers, parliamentary secretaries and parliamentary assistants, and persons of trust defined by Article 2 of the Act. While this scope is broad, there are several key positions that remain outside the integrity framework, including elected and appointed officials at local level. Indeed, given that Malta is a small country where citizens know each other well, there is a higher need for clarity for public officials across all levels of government to guide behaviour. Moreover, the close interactions between the political and business communities emphasise the need for having clear standards of conduct in place to ensure that public decision making is not unduly influenced by the select few.

Article 3(2) of the Standards Act accommodates for enlarging the scope, noting that the Act shall also apply to any other person or category of persons as the Minister for Justice may prescribe by regulations supported by an affirmative resolution of the House of Representatives. To close existing gaps in coverage, the Ministry for Justice could consider widening the Standards Act scope. As a starting point, the scope could be expanded to include the following:

Local authorities (including mayors and local councillors) have direct, day-to-day interactions with citizens. Evidence has found that those at the local level can be prone to higher risks of corruption and misconduct because of their high proximity to public and users of government services. Indeed, sub-national governments are responsible for services in which there is a more frequent and direct interaction between government authorities and citizens and firms (e.g. education, health, waste management, granting licences and permits), creating more opportunities to test public officials’ integrity (OECD, 2017[6]). Additionally, a significant share of public funds is spent on subnational levels –in 2017, government investment at subnational local level represented 29% of total government investment in OECD countries–, which means that ensuring integrity and anti-corruption at subnational levels is critical to achieve the best use of public funds (OECD, 2021[8]).

Members of government boards including the boards of Directors of public organisations and companies. Members of these boards are covered under the Public Administration Act’s Code of Ethics, but there is currently no entity responsible for ensuring their adherence to upholding the provisions under the Code. The integrity framework for elected and appointed officials in France serves as a good practice, considering the broad range of coverage (see Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. A broad range of integrity coverage over elected and appointed officials in France

Since 1988, members of the French government, French MEPs, elected officials (including presidents of regional or departmental councils), and the heads of local government have been required to declare their assets before entering their position. In 2013, two laws on transparency of public life (Laws No. 2013-906 and No. 2013- 907) widened this obligation. These laws expanded the obligation of disclosing their assets and interests within two months of taking office to 15 000 public officials including close advisers to the president, ministers and leaders of the two Legislative Assemblies, high-ranking civil servants, members of independent administrative authorities and military officials. Additionally, the 2013 laws provided for the publication of the interest declarations by members of government, parliamentarians, MEPs, local elected officials, and of the asset declarations by members of government.

The 2013 law also established the High Authority for the Transparency of Public Life, an independent administrative authority responsible for collecting and verifying the interests and assets declarations made by those covered by the 2013 laws on transparency of public life.

The Ministry for Justice could consider, as part of a bill to amend the Standards Act, a provision to amend the Constitution so as to prohibit elected officials from holding secondary positions in all public functions

The Standards Act – and associated Codes of Ethics in Schedules I and II – is currently silent regarding the issue of incompatibilities of secondary employment for elected officials. This is particularly problematic, given the practice in Malta to appoint backbencher MPs to positions in government departments, boards and commissions. Elected officials – whether within a parliamentary or presidential system – play a critical accountability role over the actions of the executive. It is their duty to hold the executive accountable for how public monies are spent and public policies determined. The practice of placing elected officials in the executive therefore fundamentally undermines the accountability role of parliament. Indeed, as noted in a report by the Inter-parliamentary Union, “it follows that the purpose of most incompatibilities is to prevent parliament from being composed of persons who are subject to government control because of their professional connections or economic dependence.”

The Ministry for Justice could therefore consider amendments to the Constitution so as to prohibit elected officials from obtaining secondary employment in all public functions. Such an amendment could be included as part of a bill intended primarily to amend the Standards Act, since the constitutional amendment would reinforce the amendments that are being proposed to strengthen the Act itself.

The Ministry for Justice could consider clarifying the definition of ‘persons of trust’ in the Standards Act to ensure that all those who presently act as a person of trust are covered under the Commissioner’s remit

The appointment of persons of trust responds to the idea that ministers need to have staff in their secretariats in whom they can repose their full personal confidence and who can assist them by giving political advice and support that would be inappropriate for the civil service to provide (Institute for Government, 2021[11]). Indeed, there is a legitimate need for ministers, who have a political mandate, to benefit from the assistance of persons of trust who assist them in implementing their political programme. However, serious integrity risks arise when the number of such persons of trust is excessive and when this procedure is widely used to substitute appointments on merits, thereby threatening the quality of the civil service (Venice Commission, 2018[12]).

In Malta, Article 110 of the Constitution sets out the general principle that employees in public administration should be recruited based on merit. However, as an exception to this article, the government can appoint political appointees on the basis of trust (“persons of trust”). This process bypasses the Public Service Commission and merit-based appointments. In recent years, appointments on trust have led to controversy for its extensive use across government, reaching 700 persons of trust in 2018 (Venice Commission, 2018[12]). These appointments extend beyond the traditional usage of political appointees, and include appointments that make part of the permanent machinery of the public administration (e.g. security guards, gardeners, drivers and maintenance officers). As a result, there have been attempts to narrow the use of this type of appointments, but these efforts have led to more loopholes and problems. For instance, by Act XVI of 2021 the definition of “person of trust” included in Article 2 of the Standards Act was substituted with the purpose of establishing a legal basis for the appointment of persons of trust.2 Although the new definition is somewhat clearer than the previous one, new issues arise.

First, the new definition does not cover persons who were already serving public employees when they were engaged as secretariat staff on the basis of trust, as the new definition only considers as a person of trust those consultants and other staff who have been engaged directly from outside the public service and the public sector. As such, these persons are no longer subject to investigation by the Commissioner. The 2022 Manual on Resourcing Policies and Procedures makes a distinction between persons of trust and people occupying a position of trust, in other words, public officers/employees engaged on a trust basis. Despite this differentiation, people occupying a position of trust are also central in the public decision‑making process and should fall under the remit of the Commissioner.

Second, the new definition does not specify whether the Standards Act covers persons of trust appointed in other designated offices and in the Strategic and Priorities Unit in each ministry. According to the 2022 Manual on Resourcing Policies and Procedures, ministries may engage persons of trust to serve in the private secretariat of ministries, parliamentary secretaries and other designated offices or to form part of the Strategic and Priorities Unit within the respective ministry (Government of Malta, 2022[13]). However, the new definition of persons of trust only mentions those serving in private secretariats of a minister or parliamentary secretary, leaving outside the Standards Act’s remit persons of trust appointed in other areas of a ministry. This is relevant considering that although in Malta the majority of persons of trust hold positions in the private secretariats of ministers and parliamentary secretaries, ministers also make appointments on trust to units that are closely associated with their secretariats but have separate complement limits (Office of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life, 2021[14]).

Considering these remaining challenges, the Ministry for Justice could consider clarifying the definition of ‘persons of trust’ in the Standards Act to ensure that all those who presently act as a person of trust are covered under the Commissioner’s remit. For instance, a new definition of the term “person of trust” could include any person performing duties in a ministry, government departments or agency by virtue of an appointment that has not been made in terms of Article 110 of the Constitution of Malta. If needed, the definition could exclude specific categories of people who should not fall under the Standards Act, but by default, it would cover all persons appointed in a ministry, government departments or agency on the basis of trust. This aims to avoid loopholes by guaranteeing all persons of trust are covered by the Standards Act –unless explicitly mentioned– and facilitate the submission of complaints by simplifying the definition of persons of trust.

While clarifying the definition to ensure all who currently or in the future act as a person of trust will enable the Commissioner to assume an accountability role over these positions, the government should more broadly consider limiting the use of such appointments. This recommendation has been supported at the international level, including most recently in the compliance report by the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO). Indeed, despite recognising efforts by the Maltese government to solve the legal situation of persons of trust, GRECO considers that the recent amendments to the Standards Act and the Public Administration Act – made by Act XVI of 2021 – do not appear to fully address the recommendation to limit its number to an absolute minimum (GRECO, 2022[15]).

There are a number of reasons for limiting the use of appointments based on trust, including that merit-based systems create an esprit de corps that rewards hard work and skills, while appointment-based systems can increase risks of patronage and nepotism. When people are appointed for non-merit based reasons, they may see their position as an opportunity for self-enrichment. Moreover, non-merit based appointments are often short term, which can increase “short-term opportunism”, with individuals using their position to maximise personal gain during the short time they have. Finally, separating the careers between bureaucrats and politicians has also shown to provide incentives for each group to monitor the other and expose each other’s conflicts-of-interest and corruption risks. Conversely, when the bureaucracy is mostly made up of political appointments, loyalty to the ruling party may provide disincentives for the bureaucracy to blow the whistle on political corruption (and elected officials may also be more willing to engage in corrupt acts within the bureaucracy) (OECD, 2020[4]). To that end, the Office of the Prime Minister could revisit the policy on engaging persons of trust to restrict usage beyond appointing political advisors for Ministers and close loopholes that enable exploitation. Moreover, to encourage transparency, the Office of the Prime Minister could annually publish and submit a report to the House of Representatives setting out the numbers, names and pay bands of current persons of trust. These recommendations are aligned with good practices from other jurisdictions (Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. Managing political appointees in the United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, special advisers are political appointees hired to support ministers on political matters. Ministers personally select special advisers for the appointment, but the Prime Minister approves all appointments.

There is no statutory limit on the number of special advisers. However, successive editions of the Ministerial Code have restricted the number of special advisers that most ministers can appoint. The most recent version of the Ministerial Code states: “with the exception of the Prime Minister, Cabinet Ministers may each appoint up to two special advisers. The Prime Minister may also authorise the appointment of special advisers for Ministers who regularly attend Cabinet” (UK Cabinet Office, 2019[16]). Additionally, the 2019 Ministerial Code indicates “all special advisers will be appointed under terms and conditions set out in the Model Contract for Special Advisers and the Code of Conduct for special Advisers” (UK Cabinet Office, 2019[16]).

For the sake of transparency, the Government annually publishes a statement to Parliament setting out the numbers, names and pay bands of special advisers, the appointing Minister and the overall playbill.

Note: The 2021 Annual Report on Special Advisers can be found here: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/ file/1002880/Annual_Report_on_Special_ Advisers_2021_-_Online_Publication.pdf.

Source: (UK Cabinet Office, 2019[16]).

The Ministry for Justice could consider including a clear definition of ‘misconduct’ in the Standards Act and ensure former Members of Parliament can be investigated and sanctioned for misconduct during their term in office

As noted above, an effective integrity system requires clear and common definitions that inform all actors which circumstances can result in breaches of their expected behaviour and conduct (OECD, 2020[4]). Indeed, effectively implementing integrity standards requires public officials who know when and how to identify potential or real circumstances that could lead to misconduct or corrupt behaviour.

Article 13(b) of the Standards Act empowers the Commissioner to investigate any matter alleged to be in breach of any statutory or any ethical duty of any person to whom the Act applies. However, what constitutes ‘misconduct’ differs per category, leading to a lack of clarity for those concerned. For example, in the case of persons of trust, misconduct is defined by Article 3(1) (b) to mean breaches of the provisions of the Code of Ethics included in the First Schedule to the Public Administration Act. In the case of Members of the House of Representatives (including ministers, parliamentary secretaries and parliamentary assistants), there is no clear and unique definition of misconduct, rather definitions referring to various types of misconduct are scattered throughout the Act:

Article 13(b) empowers the Commissioner to investigate allegations regarding the “breach of any statutory or any ethical duty” of any person to whom the Standards Act applies.

Article 18(4) states that the Commissioner should refer the matter to the appropriate authority during or after an investigation if there is substantial evidence of any significant “breach of duty or misconduct on the part of any person to whom the Act applies”.

Article 28 empowers the Committee for Standards in Public Life to decide on the sanctions to be applied when there has been a “breach of the Code of Ethics or of any statutory or ethical duty”.

An additional confusion arises from Article 22 on the procedures after investigation, which makes a distinction between particular types of misconduct. Article 22(1) refers in general to breaches of “any statutory or any ethical duty as provided under this or any other law” whereas Article 22(2) specifically refers to abuses of discretionary powers in a manner that constitutes abuse of power. This distinction means that if the Commissioner finds a MP guilty of having abused his/her discretionary powers under Article 22(2), the Committee would face limitations with regards to the sanctions it can impose under Article 28, as only Article 22 makes a distinction of this particular type of misconduct. In the same way, if after an investigation the Commissioner is of the opinion that a MP is guilty of having abused his/her discretionary powers under Article 22(2), the Commissioner would face difficulties in determining whether to refer the matter to another appropriate authority.

Given the complications arising from the various definitions and the lack of clarity that ensues, the Ministry of Justice could consider amending the Standards Act to include a single definition of misconduct of Members of the House of Representatives (including ministers, parliamentary secretaries and parliamentary assistants) to which Articles 13, 18, 22 and 28 would then refer. The definition should not include an exhaustive list of expected conducts and behaviours, but could be broad and further developed in the corresponding codes of ethics of those covered by the Standards Act. For instance, misconduct could be defined as “breaches of any statutory or any ethical duty including the provisions of the corresponding Code of Ethics to which Members of the House of Representatives, Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries by virtue of the Standards Act are subject”.

Moreover, the definition of misconduct could be expanded to enable the Commissioner to investigate cases of misconduct by former MPs in the course of their official functions and the Committee for Standards to impose corresponding sanctions, when such conduct involved, for example, a breach of public trust or the misuse of information or public resources. Being able to investigate and sanction former MPs for misconduct during their time in office could strengthen public trust in the Maltese parliamentary system as well as discourage public officials from misbehaving, as leaving office will not protect public officials from being investigated and sanctioned. The Independent Commission against Corruption Act 1988 from New South Wales, Australia, could be used as an example to draw up the definition of misconduct in Malta covering former MPs (see Box 2.3). However, considering that for legal certainty purposes, these violations require a statute of limitations, the Ministry of Justice could consider revising the timeframes for submitting complaints (see also Section 2.4.1).

Box 2.3. Definition of corrupt conduct in the Independent Commission Against Corruption Act of New South Wales, Australia

The Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1988 promotes integrity and accountability of public administration in New South Wales, Australia. In particular, Article 8 of the Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1988 defines “corrupt conduct” as:

(a) any conduct of any person (whether or not a public official) that adversely affects, or that could adversely affect, either directly or indirectly, the honest or impartial exercise of official functions by any public official, any group or body of public officials or any public authority, or

(b) any conduct of a public official that constitutes or involves the dishonest or partial exercise of any of his or her official functions, or

(c) any conduct of a public official or former public official that constitutes or involves a breach of public trust, or

(d) any conduct of a public official or former public official that involves the misuse of information or material that he or she has acquired in the course of his or her official functions, whether or not for his or her benefit or for the benefit of any other person.

In this sense, by Articles 8(c) and 8(d) the Independent Commission Against Corruption is entitled to investigate the conduct of former public officials, including former New South Wales Members of Parliament and local government authorities, when it involves a breach of public trust or the misuse of information.

The Ministry of Justice could include definitions on ‘abuse of power and privileges’, ‘conflict-of-interest’, and ‘gifts’ to create a common understanding of expected conduct and behaviour.

As previously mentioned, clear and common definitions that inform actors what behaviour and conduct is expected from them are critical for ensuring an effective integrity system. Currently, the Standards Act includes a limited list of definitions consisting of the terms “Commissioner”, “Committee”, “corrupt practice”, “Minister”, “person of trust” and “statutory body”. Additionally, neither the Code of Ethics of Members of the House of Representatives nor the Code of Ethics for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries include relevant definitions of expected integrity conduct nor behaviour, leaving the door open to interpretation that could affect both the implementation and enforcement of integrity standards. Although the revised versions of the Codes of Ethics proposed by the Commissioner provide more details on the expected conduct and behaviour of MPs, Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries, key definitions are still missing.

To that end, the Ministry of Justice could consider including additional key definitions in the Standards Act, with the purpose of creating a common understanding of expected behaviours and an enabling framework to strengthen integrity in Malta. Such definitions should include key concepts and be aligned with the revised Code of Ethics for MPs and the revised Code of Ethics for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries. Key concepts could include:

abuse of power and privileges: Article 22(2) of the Standards Act states that if the Commissioner is of the opinion that in the conduct subject-matter of the allegation, “a discretionary power has been exercised in a manner that constitutes abuse of power”, he should send a report to the Committee for Standards and follow the procedure after investigation. Additionally, the revised Codes of Ethics for MPs and for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries include as an expected behaviour of MPs and Ministers not to abuse the powers and privileges enjoyed by them. However, there is no further guidance on what is understood as abuse of power and privileges.

conflict-of-interest: This is one of the key risk areas of the current integrity framework. Although the Codes of Ethics for MPs and for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries include obligations regarding avoiding entering into a conflict-of-interest, there is no further guidance on what constitutes a conflict-of-interest. This is particularly important in a context such as Malta –a small country where citizens know each other well– and where the line between the public and private interest may be more difficult to draw.

gifts: the Codes of Ethics for MPs and for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries include as an expected behaviour of MPs and Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries not to accept any gift, benefit or service that may reasonably create an impression that they are compromising their judgement or place them under an inappropriate obligation. This obligation leaves room for interpretation, as proven by previous cases investigated by the Commissioner.

Being the first Act to provide an integrity framework in Malta, the Standards for Public Life Act may be used to support the creation of a shared understanding of expected behaviours from MPs and persons of trust, and to communicate values and standards that politicians should observe while carrying out their daily duties. This is the case of other countries where key definitions are included in the corresponding integrity frameworks (see Box 2.4).

Box 2.4. Key definitions developed in countries’ integrity frameworks

In Canada, the Conflict of Interest Act S.C. 2006, enacted by section 2 of chapter 9 of the Statutes of Canada, establishes clear conflict-of-interest and post-employment rules for public office holders. Article 2 of the Conflict of Interest Act includes a series of definitions that apply in the Act, providing a common understanding of key concepts such as “gift or other advantage”, “private interest”, “reporting public office holder” and “spouse”, and a shared framework for the implementation and monitoring of ethical and conduct standards in Canada.

In Ireland, the Ethics in Public Office Act 1995 established obligations on the disclosure of interests of holders of certain public offices –including MPs, and created the Public Office Commission –which was later replaced by the Standards in Public Office Commission. Article 2 of the Ethics in Public Office Act includes a series of definitions that apply in the Act, providing a common understanding of key concepts such as “benefit”, “gift”, “office holder”, “registration date” and “spouse”, and creating a shared framework for the implementation and enforcing of integrity standards in Ireland.

2.3. A clear and comprehensive institutional framework for public integrity

A critical component to oversight for elected and appointed officials are effective institutional arrangements that can provide the appropriate scrutiny, while also respecting separation of powers between the executive, judiciary and legislative branches. Clarifying the institutional arrangements requires answering a critical question: should parliaments be trusted to regulate themselves or should regulation be entrusted to an external body (OSCE, 2012[5])? Although self-regulation traditionally was preferred, mainly because of the need to protect the legislative’s oversight role of the executive branch, cases of wronging led to a loss of confidence in parliaments’ ability to regulate themselves. Recent years have seen a shift towards having establishing parliamentary oversight bodies that are independent of the executive and play a critical accountability role (OSCE, 2012[5]).

Indeed, the independence of parliamentary oversight bodies is critical for an effective standards regulation. The regulation of integrity standards is often a contentious matter that requires fair and impartial investigations. In this sense, those responsible for investigating misconduct must be free from institutional and political pressure to produce outcomes favourable to those they scrutinise and from any personal interest in a particular outcome (Committee on Standards in Public Life, 2021[20]). Otherwise, public trust in parliament could be compromised.

Several core elements can ensure the independence of parliamentary oversight bodies. These elements include having a statutory basis for the oversight body that prevents it from being easily removed by those it aims to regulate. Although the abolition of an ethics body would be a controversial decision for any administration, the very possibility of this happening may prevent it from fulfilling its role and speaking out. Additionally, considering that integrity systems are not entirely rules-based but also rely on values and standards, oversight bodies with a firmer basis in statute will be more empowered to speak out against the undermining of norms and conventions that break the spirit of the system, and not only the formal rules (Committee on Standards in Public Life, 2021[20]). Other core elements include ensuring that the head of the office is appointed following an independent process, establishing a clear term in office with limited opportunities for renewal, and having sufficient resources that allow the body to effectively fulfil their responsibilities (Committee on Standards in Public Life, 2021[20]).

2.3.1. Protecting the independence of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life

Although the current legal set-up of the Commissioner fits well within these features, some weaknesses remain concerning the independence of the Commissioner and necessary breadth to carry out his functions. The following recommendations identify key areas where the Standards Act could be strengthened to address these challenges.

The Ministry for Justice could propose legislation to include the role and functions of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life in the Constitution of Malta

In 2017, the House of Representatives unanimously approved the Standards Act, establishing for the first time an institution empowered to oversee the ethical conduct of MPs, Ministers and persons of trust. However, the current set-up does not effectively guarantee the independence of the Commissioner, considering that the House of Representatives could repeal or amend the Standards Act by simple majority at any time, including abolishing the Commissioner by a simple vote.

Therefore the process of appointment, role and functions of the Commissioner could be included in the Constitution of Malta. This is already the case of the other parliamentary oversight bodies established in Malta, specifically the National Audit Office and the Office of the Ombudsmen. For example, the Office of the Ombudsmen was entrenched in the Constitution of Malta by Act No. XIV of 2007, which amended the Constitution (Article 64A) in order to include information on the Ombudsman and the Office, and Act No. XLII of 2020, which complemented Article 64A with additional information on the process of appointing, removal and suspension of the Ombudsman.

The Ministry for Justice could amend the Standards Act to assign legal personality to the office of the Commissioner to avoid conflict with Article 110(1) of the Constitution of Malta

A fundamental element for independence is granting the oversight body the ability to hire the necessary staff independently from the executive. The Standards Act –by Article 11– fulfils this requirement in part by empowering the Commissioner to appoint staff (officers and employees) to his office as may be necessary for carrying out his functions, powers and duties. However, the Standards Act omits assigning legal personality to the office of the Commissioner, threatening the office’s independence by creating potential conflicts with Article 110(1) of the Constitution, which sets the conditions for the appointment, removal and disciplinary control over public officers.

Without its own legal personality, the office of the Commissioner is technically part of government and, arguably, subject to Article 110(1) of the Constitution of Malta. This means that without its own legal personality, the Commissioner’s staff would be appointed by the Prime Minister on the recommendation of the Public Service Commission, like most government employees, as established in Article 110(1) of the Constitution. However, the aim of Article 11 of the Standards Act is clearly to separate the office of the Commissioner from the government and protect it from any political interference to guarantee its independence and objectivity.

In this sense, the Ministry for Justice could consider amending the Standards Act in order to assign legal personality to the office of the Commissioner, rectifying its full autonomy and independence from the Executive, with accountability only to the House of Representatives of Malta. This would bolster the powers of the Commissioner to appoint his own staff and would prevent any potential conflicts with Article 110(1) of the Constitution to arise.

The Ministry for Justice could align the conditions of appointment and reappointment of the Commissioner with those of the Auditor General and the Ombudsman of Malta

The Standards Act establishes a procedure for the appointment and reappointment of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life with significant elements to protect his independence. Article 4 of the Standards Act states that the Commissioner is appointed by the President of Malta supported by the votes of not less than two-thirds of the House of Representatives, and Article 6(1) states that the Commissioner is appointed for a five-year term and is not eligible for reappointment. Additionally, the Commissioner does not report to the Executive or through a minister, but directly to the House of Representatives, which grants him full autonomy and independence with accountability only to Parliament.

However, the term length, combined with the impossibility of renewal, inhibits any sitting Commissioner from fully realising the functions assigned by the Standards Act during their mandate. Moreover, current practice in Malta for replacing heads of parliamentary oversight bodies raise additional concerns. While the two-thirds majority requirement in parliament ensures cross-party support for the heads of independent offices, the deeply polarised nature of politics in Malta has historically led to delays when it comes to identifying replacements for independent offices. For example, in early 2021, the incumbent Ombudsman finished his 5-year term. To date, the incumbent remains in office because the Government and the Opposition cannot agree on a replacement. Given the sensitive political mandate of the Commissioner, it is expected that identifying a replacement in a timely manner could prove difficult.

Other jurisdictions show different practices regarding the duration and the possibility of renewal of the appointment of the responsible for leading the institution in charge of standards in public life, which depend on their particular needs and contexts. For instance, the Canadian Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner is appointed for seven years and is eligible for reappointment for one or more terms of up to seven years each. Likewise, the members of the Dutch Integrity Investigation Board are appointed for a period of up to six years and are eligible for reappointment for two terms of up six years each.

Additionally, it is worth looking at other parliamentary oversight bodies established in Malta – the National Audit Office and the Office of Ombudsmen. Article 108 of the Constitution of Malta and Article 5 of the Ombudsman Act of the Constitution of Malta establish, respectively, that the Auditor General and the Ombudsmen shall hold office for a term of five years, and shall be eligible for reappointment for one consecutive term of five years.

Considering the particularities of the Maltese context, the Ministry for Justice could consider amending the Standards Act to allow for a five-year term with the possibility of reappointment for one consecutive term of five years, supported by the votes of not less than two-thirds of the House of Representatives. This would bring the terms of appointment and reappointment in line with the Ombudsman and the National Auditor.

The Ministry for Justice could amend the Standards Act to include a deadlock breaking mechanism in the process for nominating and appointing the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life

As previously mentioned, the Standards Act establishes a procedure for the appointment of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life. Indeed, Article 4 of the Standards Act states that the Commissioner is appointed by the President of Malta supported by the votes of not less than two-thirds of the House of Representatives, which is the same procedure followed to appoint both the National Auditor and the Ombudsman.

Despite ensuring the independence of the appointment, the current practice for selecting heads of oversight bodies raises concerns related to potential deadlock. For example, despite having finished his 5-year term in early 2021, the incumbent Ombudsman remains in office because the Government and the Opposition cannot agree on a replacement.

To prevent a long-term vacancy, the Ministry for Justice could consider including a deadlock breaking mechanism in the Standards Act. The deadlock breaking mechanism should in particular indicate a time period in which the House of Representatives must complete the selection process (such as within two months of the vacancy of the position). Moreover, the mechanism could specify that in the event that the House of Representatives does not vote on or successfully choose a Commissioner, the Judicial Appointments Committee established by Article 96(a) of the Constitution, could make a binding recommendation to the President of Malta for the appointment of a Commissioner. The Judicial Appointments Committee’s recommendation could be either on a temporary or permanent basis.

The Ministry for Justice could amend the Standards Act to include clearer parameters on the Commissioner’s background and integrity responsibilities.

As mentioned above, the Standards Act establishes several core elements to ensure the independence of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life. However, unlike similar models in other jurisdictions, the Standards Act includes limited specifications regarding the preferred qualifications and background of the Commissioner. Article 5(1) of the Standards Act specifies that the Commissioner cannot be an active political, public official or person of trust, and Article 5(2) prohibits the Commissioner from holding an active role in the private sector (e.g. professional, banking, commercial or trade union activity). However, measures further detailing the expected qualifications or background of the Commissioner are not included.

The current incumbent, a well-respected lawyer with decades of public service to Malta, has retained the respect of both political parties thanks to the performance above expectations of his office and for being considered one of the functioning institutions of the integrity system in the country. However, he has been subject to criticism for his own political past, with some calling his judgements into question and suggesting some of his decisions were politically motivated. With no parameters concerning the qualifications or background of the incumbent, there are limited safeguards in place to ensure that his predecessors will have the level of experience, expertise and/or strength needed to maintain the independence and high quality of the office of the Commissioner.

In light of these challenges, the Ministry for Justice could consider amending the Standards Act to include clearer parameters on qualifications and background to guide the appointment of future Commissioners to ensure independence. Such parameters would make it difficult for future governments to appoint a weak Commissioner, and they would also protect incumbent Commissioners from attacks based on their own past. Setting out clear parameters is a good practice adopted in similar models in other jurisdictions (see Box 2.5).

Box 2.5. Clear parameters for the appointment of the heads of oversight bodies

Canada

The Parliament of Canada Act stipulates that the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner must be:

a former judge of a superior court in Canada or of a provincial court;

a former member of a federal or provincial board, commission or tribunal who has demonstrated expertise in at least one of the following areas: conflict-of-interest, financial arrangements, professional regulation and discipline or ethics; or

a former Senate Ethics Officer or former Ethics Commissioner.

Ireland

The Standards in Public Office Act stipulates that the Standards in Public Office Commission must consist of six members, including a chairperson who must be:

a judge of the Supreme Court or the High Court; or

a former judge of the Supreme Court or the High Court.

Another key element to protect the integrity of decision making and safeguard the independence of the office of the Commissioner includes establishing mechanisms for detecting and managing conflicts-of-interest. Conflicts of interest can be understood as “a conflict between the public duty and private interests of a public official, which arises from the public official’s private-capacity interests, where those interests have the potential to improperly influence the performance of official duties and responsibilities” (OECD, 2004[23]). This is particularly important when considering the Commissioner’s investigatory role where it is essential to guarantee the impartial and disinterested management of the complaints process.

Currently, there is not a formal requirement included in the Standards Act for the Commissioner to identify and disclose potential or actual conflicts-of-interests. However, in line with good practice, the current incumbent conducted self-due diligence before accepting the appointment with the intention to avoid any possibility of a potential conflict-of-interest. Going forward, this good practice should be formalised in the Standards Act to protect the independence of the Commissioner and his office.

To that end, the Ministry for Justice could consider amending the Standards Act to formalise the requirement for the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life to identify and disclose conflict-of-interests upon selection. In practice, this means that the Commissioner would be required to submit a conflict-of-interest declaration to the Speaker of the House of Representatives before taking up his/her duties. Moreover, as detailed in Chapter 1, the Commissioner could consider developing additional guidelines on how to identify, manage and prevent conflicts-of-interest by the Commissioner and his staff to ensure the coherence and relevance of standards across the office.3

The Ministry for Justice could include the appointment of a temporary Commissioner for Standards in Public Life in the list of exceptions of Article 85 of the Constitution of Malta to guarantee their independence.

While the Standards Act grants the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life autonomy and independence to comply with his responsibilities, the available provisions for the temporary appointment of a Commissioner for Standards in Public Life raise two concerns: (i) circumstances under which a temporary Commissioner can be appointed; and (ii) concerns about independence.

According to Article 9(1) of the Standards Act, the President of Malta may temporarily appoint a Commissioner in two cases: a) during the illness or absence of the Commissioner, or b) where the Commissioner considers it necessary not to conduct an investigation himself because of any potential conflict-of-interests. The Standards Act does not envision a temporary appointment should the incumbent resign or pass away. To that end, Article 9(1) could be updated to include these two scenarios, thereby triggering the process to appoint a temporary Commissioner until the permanent replacement can be confirmed.

The second challenge concerning Article 9 pertains to a lack of safeguards to ensure the independence of the appointment process for the temporary Commissioner. These procedures raise concern when read together with Article 85 of the Constitution of Malta, which states that in the exercise of his functions, the President of Malta should act in accordance with the advice of the Cabinet or a Minister acting under the general authority of the Cabinet. Although Article 85 lists a number of exceptions for such general rule, it does not include the appointment of a temporary Commissioner for Standards in Public Life. As such, under Article 85 of the Constitution, the appointment of a temporary Commissioner should be made in accordance with the advice of the government.

To close this loophole, the Ministry for Justice could consider including the appointment of a temporary Commissioner for Standards in Public Life in the list of exceptions of Article 85 of the Constitution, to guarantee the independence of any temporary Commissioner and shield the office of the Commissioner from any political influence.

The Ministry for Justice could amend the Standards Act to clarify the procedure for enacting further regulations.

Two articles of the Standards Act provide information on the enactment of additional regulation for the guidance of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life under the Act. First, Article 15 of the Standards Act empowers the House of Representatives to make general rules for the guidance of the Commissioner. More precisely, Article 15(1) states that such rules must be made by resolution, while Article 15(2) establishes that “all rules made under this article shall be made by, and published as, subsidiary legislation made under this Act”. Second, Article 29 empowers the Minister for Justice and Governance to make regulations to implement and to give better effect to the provisions of the Standards Act. Such Article provides for the enactment of subsidiary legislation as it refers to legislation to further develop the provisions of the Standards Act without amending it.

Considering this, it is not clear whether the House of Representatives should frame its rules for the Commissioner’s guidance by resolution (Article 15(1)) as a request to the Minister for Justice and Governance to enact its proposal through regulations under Article 29, or whether Article 15(2) empowers the House to issue subsidiary legislation in its own right. In this sense, the Ministry for Justice could consider aligning the conditions for enacting rules for guidance with those established on Article 15 of the Ombudsman Act, while also clarifying that the procedure to enact further regulations under the Standards Act should not prejudice the independence of the Commissioner for Standards.

2.4. Strengthening the functions of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life

In addition to having independence from any political or institutional interference, parliamentary oversight bodies also need clear roles and responsibilities assigned to them. Article 13 of the Standards Act assigns the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life the following functions:

To examine the declarations relating to income, assets, other interest and/or benefits filed by persons who are subject to the Act;

To investigate the conduct of persons subject to the Act, on the Commissioner’s initiative or based on a written complain;

To give recommendations to persons seeking advice on whether an action or conduct intended by them falls to be prohibited by the applicable Code of Ethics or by any other particular statutory or ethical duty;

To monitor parliamentary absenteeism and to ensure that MPs pay the administrative penalties to which they become liable if they have been absent throughout the whole session without permission of absence;

To identify lobbying activities and to issue guidelines accordingly;

To make recommendations concerning the improvement of any Code of Ethics applicable to persons who are subject to the Act, on the acceptance of gifts, the misuse of public resources, the misuse of confidential information, and on post-public employment.

This section reviews and analyses the Commissioner’s functions as established in the Standards Act, and proposes recommendations to amend the Standards Act in order to address its main weaknesses and loopholes in terms of setting clear roles and responsibilities to the Commissioner.

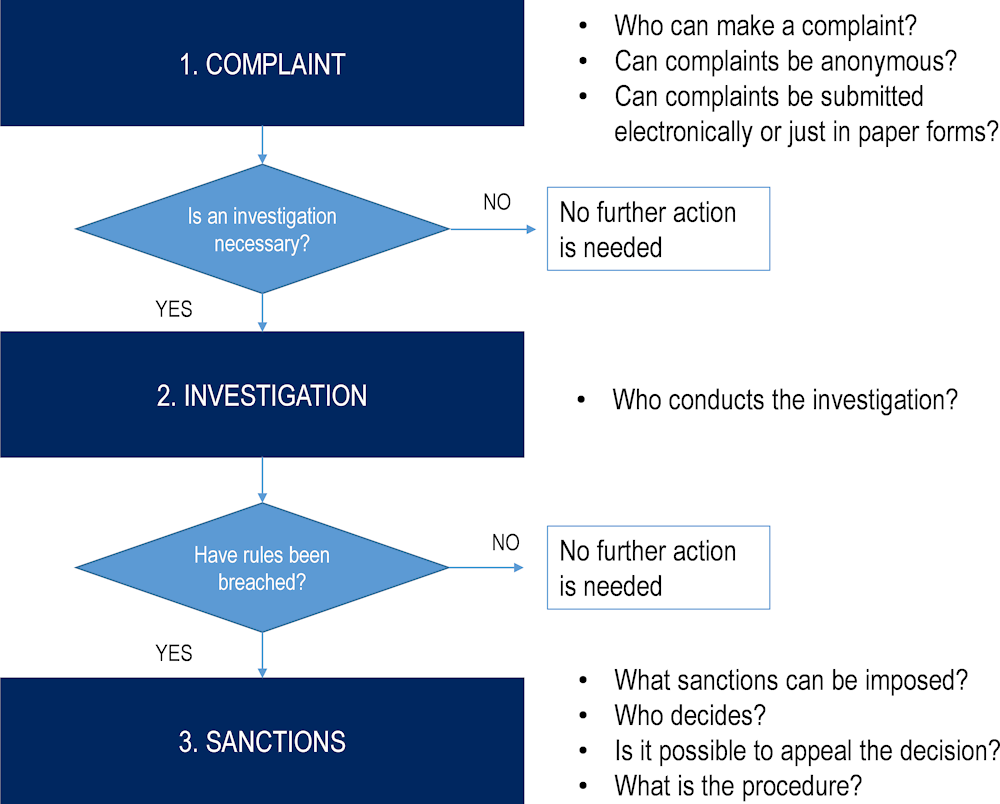

2.4.1. The Ministry for Justice could amend the Standards Act to strengthen the complaints management process

A core function of parliamentary oversight bodies is to receive and investigate complaints concerning potential breaches of conduct. Three essential procedural elements make up this process: first, the receipt of a formal complaint regarding the conduct of a person covered by the ethics rules, and determination of whether the complaint meets the minimum standards to start an investigation. In this first element, some oversight bodies also have the ability to investigate potential breaches of their own initiative. Second, the investigation to establish the facts and determine whether ethical rules or norms were breached, and third, determining the appropriate and proportionate sanctions to apply to address the breaches (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. General procedure to monitor and enforce ethical standards

In the case of Malta, the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life is responsible for investigating any matter alleged to be in breach of any statutory or any ethical duty of any person to whom the Standards Act applies (Article 13 of the Standards Act). Such investigations can be launched on the Commissioner’s own initiative or on a written complaint made by any person to his office. If a complaint is found eligible, the Commissioner opens an investigation and carries out the collection, recording and analysis of evidence that allows him to decide whether statutory or ethical duties were breached or not. Where misconduct is found to have occurred and depending on the severity of the breach, the Commissioner may decide to grant the person investigated a time limit within which to remedy such breach, or may refer the case to the Committee for Standards in Public Life, which decides on the appropriate sanction to be imposed.

The Ministry for Justice could consider revisiting the timeframes for submitting complaints included in Article 14 of the Standards Act

Regarding the first element to monitor and enforce ethical standards (1. Complaint), the main challenge consists in designing a system that promotes accessibility of potential complainants to the complaints system. This entails having clear procedures for submitting complaints and ensuring that complainants do not face significant obstacles when trying to submit their complaints.4

In the case of Malta, there are clear procedures for submitting complaints, both in the Standards Act and further developed by the Commissioner, as well as elements to facilitate complainants access to the system. For instance, the Standards Act allows complainants to make their complaints both in writing and orally (although the latter procedure has not been used yet), and when done in writing, they can be sent by post, email and through the Commissioner’s website. Additionally, the Commissioner’s website has a section about “complaints” with further details on how to make a complaint and other relevant information about this process aiming at further guiding complainants.

However, other provisions of the Standards Act create barriers for complainants and impede the Commissioner from undertaking investigations. The first barrier relates to the limited timeframes for submitting complaints, where Article 14 of the Standards Act states that the Commissioner cannot investigate complaints that have any of the following characteristics:

1. If the fact giving rise to the complaint occurred prior to the date in which the Standards Act came into force, this is, 30 October 2018;

2. If the complaint is made after thirty working days from the day on which the complainant had knowledge of the fact giving rise to the complaint;

3. If the complaint is made after one year from when the fact giving rise to the complaint happened.

Regarding the first case, it is worth considering that the Standards Act is the first legal base of a comprehensive integrity framework for elected and appointed public officials in Malta. This means that prior to 30 October 2018, Malta did not have a clear and formal framework for guiding the conduct, investigating potential offenses and sanctioning breaches of ethical and integrity standards by elected and appointed officials (i.e. MPs, ministers, parliamentary secretaries, parliamentary assistants and persons of trust). In this sense, in the absence of a formal framework, the Commissioner should not be able to investigate violations that took place before the entry into force of the Standards Act. However, the Commissioner has established that in the case of on-going actions, the relevant date for the purposes of determining whether or not the actions are time-barred is the date when the actions cease (see report on case K/002). This is in line with Maltese criminal law. In keeping with this, also considering the particularities of Malta and with the aim of further building trust in the integrity framework for elected and appointed officials, the Ministry of Justice could clarify in the Standards Act that the Commissioner can investigate on-going actions (under the Standards Act and/or any statutory or any ethical duty), even if the actions started before 30 October 2018. In this way, the Act would clarify that the Commissioner could investigate actions that started before the 30 October 2018 but were still ongoing as of that date. This would align with Article 13 (1 a and b), which allows the Commissioner to investigate breaches of other laws on public integrity standards that were enforceable prior to the Standards Act enactment.

Additionally, the remaining timeframes considerably limit the submission of complaints and generate mistrust in the current complaints system. Previous complainants noted that they could not submit serious complaints of public officials’ misconduct because of the current limitations of the complaints system. Thus, despite the existence of conclusive evidence, severe cases of misconduct were going unpunished just because the fact giving rise to the complaint had taken place more than a year from the date the compliant was made or because the complaint was made after thirty working days from the day on which the complainant had knowledge of the situation.

Like any jurisdiction, Malta faces integrity challenges that are unique to its context. To enable the Commissioner adequate time to review a breach of statutory or ethical duties that may have occurred during an elected or appointed officials’ term in office, without unduly restricting the process, the Ministry of Justice could lengthen the period of time within which a person can submit a complaint. In this sense, the Ministry for Justice could consider revisiting the “thirty working days” and the “one year” timeframes to submit and investigate a complaint, in order to encourage more complainants to come forward and strengthen citizen’s trust in the integrity system. Other jurisdictions have set longer periods of time to enforce their integrity standards, including the Massachusetts Ethics Commission in the United States, which has five years from the date the Commission learned of the alleged violation, but not more than six years from the date of the last conduct relating to the alleged violation, to start public proceedings against an individual (State Ethics Commission, n.d.[24]).

The Ministry for Justice could amend the Standards Act to enable anonymous complaints and empower the Commissioner to grant whistle-blowers status

In addition to restrictive timeframes, the second barrier to accessibility includes the inability for complaints to be submitted anonymously (as laid out in Article 16 of the Standards Act). To date, the Commissioner has received five anonymous complaints, which he has been unable to review given the restrictions set out in the Standards Act. Anonymous complaints are not allowed because (i) it makes it difficult for follow-up; and (ii) anonymity can been seen to increase the risk of superfluous or slanderous complaints. However, encryption technology5 can be used to address both of these concerns: first, by enabling the Commissioner to follow up with complainants who prefer to remain anonymous; and second, by discouraging those who wish to abuse the system by making it clear that they will still be contacted and asked to provide additional information or substantiate their claims further. The benefits of allowing anonymous complaints outweigh the risks, by improving the accessibility of the system.

Given the sensitivity of the information held, and the often high-profile individuals concerned, there is a risk that the person who submitted the complaint could face retaliation. If this person is a private citizen, they have no recourse to protection in the face of potential threats. While the Commissioner does apply measures to ensure confidentiality, including in the Standards Act a guarantee of anonymity could help those private citizens with genuine concerns regarding potential ethical misconduct by persons covered under the Act to come forward. To that end, the Ministry for Justice could consider amending the Standards Act to enable anonymous complaints.

Finally, the third barrier to accessibility rests in the Commissioner’s inability to grant whistle-blower status to public employees who disclose misconduct observed in their workplace. Similar to the rational for allowing anonymous complaints, public employees who witness misconduct by their political superiors or other appointed officials covered under the Standards Act may be hesitant to submit a complaint due to a genuine fear of retaliation. Currently Malta has a whistle-blower protection system in place, laid out in the Protection of the Whistle-blower Act 2013 (see Box 2.6). However, under the current system, complaints made to the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life do not fall under the Protection of the Whistle-blower Act, meaning the Commissioner is not empowered to grant the complainant any whistle-blower status or protection.

To address the weakness in the current system, the Ministry for Justice could consider amending the Standards Act to enable the Commissioner to grant whistle-blower status to public employees who disclose misconduct in good faith and on reasonable grounds in the context of their workplace. Doing so would further enhance accessibility to the complaints system by addressing potential concerns related to fear of reprisals. It is worth noting that in addition to amending the Standards Act, the government would also need to amend the Protection of the Whistle-blower Act 2013 (Chapter 527 of the laws of Malta), to include the Commissioner within the landscape of institutional actors for applying whistle-blower status.

Box 2.6. Malta’s Whistle-blower Protection Framework

In Malta, the whistle-blower protection framework is established in law through the Protection of the Whistle-blower Act 2013. This Act establishes a system of internal and external reporting channels to be used by persons disclosing in good faith corrupt practices and other suspicious behaviour, and allows various forms of protection for the whistle-blower). As part of the measures implemented, the Act requires all ministries to appoint a whistleblowing reporting officer responsible for receiving reports from informers, establishes an external whistle-blowing disclosure unit –the Cabinet Office– to handle external disclosures by public sector employees, and presents a number of authorities to receive external disclosures by the private sector, including the Office of the Ombudsman.

The Ministry for Justice could amend the Standards Act to enable the Commissioner to request additional information to determine whether an individual or the alleged breach falls under the Standards Act and an investigation is warranted

To ensure independence of parliamentary oversight bodies, it is also necessary to guarantee that the head of the office is empowered to initiate investigations, including launching investigations on their own initiative, and that they have access to all the necessary evidence to determine whether a breach existed or not (Committee on Standards in Public Life, 2021[20]). In Malta, the Standards Act empowers the Commissioner to investigate the conduct of persons subject to the Act – on his initiative or based on written allegations- as well as to gather the evidence needed in the course of an investigation. However, in certain situations, the Commissioner faces limitations to initiate an investigation, which can impede his ability to hold accountable those individuals that fall under the Standards Act.

First, the Commissioner can encounter limitations when seeking to determine whether an allegation can be investigated or not, in particular when trying to determine whether the alleged breach falls outside the timeframes stipulated in the Act. Second, with regards to persons of trust, the current definition included in Act XVI of 2021 creates difficulties for the Commissioner to establish whether he is entitled to carry out an investigation or not in all possible scenarios. For instance, under the current system, if the Commissioner receives a complaint against a person working in a government department, additional information is required to first determine whether the person falls under the Commissioner’s remit or not. However, given current limitations in the Standards Act, it is not clear whether the Commissioner can request additional information (such as an employee’s contract of employment) to determine whether that person is a permanent public employee (and hence not subject to the Standards Act) or a person recruited on trust serving in the private secretariat of a minister or parliamentary secretary (and hence subject to the Standards Act).

The Ministry for Justice could therefore consider amending the Standards Act to explicitly grant the Commissioner the ability to request the necessary documentation to determine whether an individual or the alleged breach falls under the Standards Act and is subject to investigation. With particular reference to persons of trust, this power should also be granted to the Commissioner even if the definition of “persons of trust” is modified as recommended in the first section of this chapter, unless no exceptions to the term “persons of trust” are included in such definition.

The Ministry for Justice could amend the Standards Act to further detail the proceedings after investigation, including on publishing case reports

Regarding the process for investigations, two key elements are critical: defining who carries out the investigation and setting a clear, transparent and fair procedure to do so. In Malta, the Standards Act empowers the Commissioner to conduct the investigations of potential breaches of ethics and establishes a procedure for this, which includes several elements to guarantee its transparency and fairness. However, challenges remain in terms of ensuring that cases are handled in a timely manner, the procedure is clear and consistent, and that reports are published appropriately. This chapter focuses on the challenges associated with the timely publication of reports, while the Chapter 1 provides recommendations to ensure that cases are handled in a timely manner following a clear procedure.

The investigation process according to the Standards Act is as follows: upon receipt of a complaint, the Commissioner conducts a preliminary review to determine whether it is eligible for investigation in terms of the Standards Act. If a complaint is found eligible, the Commissioner opens an investigation, which is conducted following the proceedings established under the Standards Act (Articles 18 to 21). The Commissioner is expected to conclude his investigation within six months of having received the complaint. However, if this is not the case, the Commissioner should inform the Speaker of the House about the reason for the delay; this should be done every six months until the closure of the investigation.

Although the Standards Act establishes some general guidelines during and after an investigation, the Commissioner considered it necessary to set out more detailed internal procedures to be followed after having considered complaints pursuant to the Standards Act, including on the publication of case reports. To that end, the Committee for Standards and the Commissioner agreed on a series of procedures, and laid them down in a memorandum and letter. The internal procedures specify the following:

If after an investigation the Commissioner does not find evidence of misconduct, he issues a report which is published on his website (except for exceptional circumstances) and submitted to the person investigated, the complainant and the Committee for Standards, purely for information purposes.

If after an investigation the Commissioner finds that a prima facie breach of ethics or of a statutory duty has occurred, he must elaborate a report and follow one of the subsequent procedures:

If the breach was not of a serious nature and the person investigated agrees with the outcome of the investigation, the Commissioner may grant the person a time limit within which to remedy the breach by application of Article 22(5) of the Standards Act. If the remedy is carried out to the Commissioner’s satisfaction, he publishes the report on his website and closes the case.

If the breach was of a serious nature, the Commissioner must submit the report to the Committee for Standards in Public Life, who then decides whether to adopt the conclusions and any recommendations contained in the report, and takes an action by applying Articles 27 and 28 of the Standards Act. Additionally, the Commissioner informs the individual investigated and the complainant that the report has been concluded and has been submitted to the Committee. In these cases, the Committee for Standards is responsible for deciding when to authorise the publication of the reports on the Commissioner’s website (Commissioner for Standards in Public Life, 2021[26]; Commissioner for Standards in Public Life, 2019[27])

The procedure regarding publication of reports on cases of a serious nature has given rise to several challenges for the Commissioner, his office and the Committee for Standards. In particular, reports are often leaked to the media once the Commissioner has submitted his findings to the Committee for Standards, and political considerations, rather than those concerning accountability and transparency, drive decisions to publish the reports. To address these issues, two considerations are key: strengthening transparency and accountability while respecting the principles of fair process, and addressing political polarisation. The first can be dealt with regarding the process of investigations, whereas the second can be dealt with by reforming the structure of the Committee (as discussed below).

Regarding accountability and transparency, it is necessary to find the right balance between these principles and the principle of fair process and confidentiality. On the one hand, it is necessary to ensure transparency concerning the status of case reports so that the public can hold the Commissioner and the Committee for Standards accountable for processing the complaints. On the other hand, it is paramount that fair process be respected to uphold the integrity of the investigation.

As such, to improve transparency and accountability, the Ministry for Justice could consider including an obligation to the Commissioner in the Standards Act to provide further details on the procedures during and after investigation. To start, the Standards Act could clarify that the Commissioner will publish the status of all cases received on his website (for example, accepted/rejected, under review, submitted to the Committee, concluded). Codifying transparency in this regard will reduce the need for speculation about the status of a case, and will enable the public to hold the various actors responsible for processing the case.

With regards to the publication of case reports, the Standards Act could also be further clarified. First, it could specify that in cases where there is no evidence of misconduct or where the breach was not of a serious nature, the Commissioner’s reports will be published on the website upon conclusion of the investigation. Second, in cases concerning breaches of a serious nature, the Standards Act could clarify that upon conclusion of the investigation, the Commissioner will submit the findings report to the Chairperson of the Committee for Standards. Following this, the Chairperson will share the findings report with the Committee for Standards and approve the Commissioner’s publication of the report on the Commissioner’s website.

To facilitate transparency during the Standards Committees proceedings, the Standards Act could further clarify that the Committee for Standards will keep an up-to-date list on its website of cases currently considered by the Committee, including when the case reports were received and when the Committee will consider the Commissioner’s findings and issue their conclusions. Additionally, the Standards Act could clarify that the Committee for Standards will issue a report concerning the reasons for adopting or not the conclusions and recommendations contained in the findings report by the Commissioner – including, when appropriate, the reasons for conducting additional investigations. Such report could be published in the Committee’s website and be linked to the corresponding findings report by the Commissioner.

Clearly establishing the procedure for publication in the Standards Act will close existing loopholes and address ongoing public confusion about expectations. Established rules will also place obligations on the Commissioner, his office and the Standards Committee to which they will be accountable. In clarifying these rules, it is essential that the principles of fair process and impartiality remain at the forefront, to avoid further enflaming a naturally tense process.

2.4.2. The Ministry for Justice could amend the Standards Act to include a comprehensive and proportionate system of sanctions